This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Last Woman

Author: Ross Beeckman

Release Date: March 24, 2008 [eBook #24910]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LAST WOMAN***

by

ROSS BEECKMAN

AUTHOR OF

"Princess Zara"

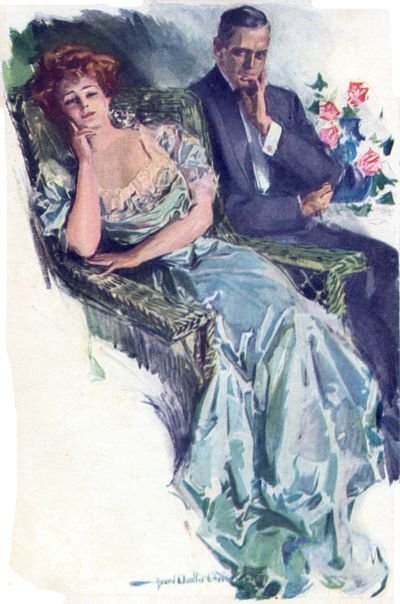

FRONTISPIECE BY

HOWARD CHANDLER CHRISTY

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1909—by

W. J. WATT & COMPANY

Published August

THE THEME

If I could have my dearest wish fulfilled,

And take my choice of all earth's treasures, too,

And ask of Heaven whatsoe'er I willed—

I'd ask for you.

There is more joy to my true, loving heart,

In everything you think, or say, or do,

Than all the joys of Heaven could e'er impart,

Because—it's YOU.

THE PRICE

ONE WOMAN WHO DARED

A STRANGE BETROTHAL

THE BOX AT THE OPERA

BEATRICE BRUNSWICK'S PLOT

A REMARKABLE MEETING

THE BITTERNESS OF JEALOUSY

BETWEEN DARKNESS AND DAYLIGHT

PATRICIA'S COWBOY LOVER

MONDAY, THE THIRTEENTH

MORTON'S ULTIMATUM

THE QUARREL

SALLY'S GARDNER'S PLAN

PATRICIA'S WILD RIDE

ALMOST A TRAGEDY

THE AUTOMOBILE WRECK

CROSS PURPOSES AT CEDARCREST

MYSTERIES BORN IN THE NIGHT

RODERICK DUNCAN SEES LIGHT

THE LAST WOMAN

THE REASON WHY

THE MYSTERY

BOOKS ON NATURE STUDY BY CHARLES G. D. ROBERTS

FAMOUS COPYRIGHT BOOKS

THE PRICE

The old man, grim of visage, hard of feature and keen of eye, was seated at one side of the table that occupied the middle of the floor in his private office. He held the tips of his fingers together, and leaned back in his chair, with an unlighted cigar gripped firmly in his jaws. He seemed perturbed and troubled, if one could get behind that stoical mask which a life in Wall street inevitably produces; but anyone who knew the man and was aware of the great wealth he possessed would never have supposed that any perturbation on the part of Stephen Langdon could arise from financial difficulties. And could his most severe critics have looked in upon the scene, and have seen it as it existed at that moment, they would unhesitatingly have said that the source of his discomfiture, if discomfiture there were, was the queenly young woman who stood at the opposite side of the table, facing him.

She was Patricia Langdon, sometimes, though rarely, addressed as Pat by her father; but he alone dared make use of the cognomen, since she invariably frowned upon such familiarities, even from him.

In private, among the women with whom she associated, she was frequently referred to as Juno; and when she was discussed by the gossips at the clubs, as she frequently was (for there are no greater nests of gossip in the world than the men's clubs of New York City), she was always Juno. There was a double and subtle purpose in both cases; one felt it rather a dangerous proceeding to speak criticizingly of Patricia Langdon, lest somehow what was said should get to her ears. She was one who knew how to retaliate, and to do so quickly. She was like a man in that she feared nothing, and hesitated at nothing, so long as she knew it to be right. A precedent had no force with her; if she desired to act, and there was no precedent for what she wished to do, she established one.

All her life, Patricia had been her father's chum; ever since she could remember, they had talked together of stocks and bonds, and puts and calls, and opening and closing quotations, and she knew every slang word that is uttered in "the street," that is used on the floor of the stock-exchange, or that appears in the financial columns of the newspapers.

And these two, father and daughter, were as much alike in outward bearing, in demeanor and in appearance, in gesture and in motion, as a man and a woman can be when the man is approaching seventy and the woman is only just past twenty.

These two had been discussing an unprecedented circumstance. The daughter was plainly annoyed, as her glowing cheeks and flashing eyes evidenced. The man, if one could have read his innermost soul, was afraid; for he knew his daughter as no other person did, and he feared that he had gone, or was about to go, a step too far with her.

The room was the typical private office of a present-day financial king, who is banker as well as broker, and who speaks of millions, by fifties and hundreds, as a farmer talks of potatoes by the bushel. It was a large, square room, solidly but not luxuriantly furnished. The oblong table at which Stephen Langdon was seated, and upon which his daughter lightly rested the tips of the fingers of one hand, was one around which directors of various great corporations gathered, almost daily, to be told by "old Steve" what to do. Over in a far corner was a roll-top desk with a swivel chair, at which Langdon usually seated himself when he was attending to his correspondence, or looking over private papers; beside it was a huge safe, and beyond that another, smaller one. Then, there were several easy chairs upholstered in leather, a couch and two other desks. There were three doors: one of these communicated with the main office of Stephen Langdon & Company, Bankers and Brokers; another was a private entrance from the street that ran along the side of the building, which Langdon owned; the third communicated with a smaller room, really the sanctum sanctorum of Stephen Langdon, into which it was his habit to take any person with whom he wished to have an absolutely confidential chat.

This room was supposed never to be entered save by himself and those whom he took with him—and by the cleaners who once a week attended to it. These three doors were now closed.

"Old Steve" moved nervously in his chair, shifted his feet uneasily, and rolled the unlighted cigar from one corner of his mouth to the other, biting savagely upon it as he did so.

"Well, Pat," he said, with as much impatience as he ever showed, "have you nothing to say?"

"There seems to be nothing for me to say, dad," replied his daughter, and the intonation of her voice was different from the one she was accustomed to use in addressing her father, whom she adored. He attributed it, doubtless, to his abbreviation of her name, for he smiled grimly.

"Haven't you heard what I said?" he demanded.

"Certainly."

"Well, then, you know the situation, don't you?"

"I am not quite sure as to that," she replied, meditatively. "You have been somewhat ambiguous, and certainly quite enigmatical in your statement. Am I to gather from what you have told me that you are really facing failure?"

"God knows I have made it plain enough," was the quick response and Langdon pushed his chair away from the table, stretched his legs out straight in front of him, and thrust his hands deep into his trousers-pockets.

"I had not supposed it possible for you to face failure," said Patricia, with her eyes fixed upon her father's mask-like face; "but if it is so, won't you tell me more about it?"

"It all came about through those infernal bonds that I have just described to you. The men who were to go into the deal with me withdrew at the last moment; I have already explained that fully to you, and now, this Saturday afternoon, I find myself in a position such as I have never faced before—where there are demands upon me which I cannot meet; and those demands, Patricia, must be met, somehow, at ten o'clock on Monday morning, or Stephen Langdon must go to the wall."

"It amazes me," she said, speaking more to herself than to him; and she tapped lightly with her gloved fingers upon the table before her. "It amazes me more than I can say. I thought myself closely familiar with all the ins and outs of your business, dad, and I find now that I knew nothing about it at all."

"You have never known very much about it," he replied, with a half-laugh, but with a kindly smile, which changed his iron face wondrously, and which was reflected by a softened expression in his daughter's eyes.

"Is there no one to come to your aid?" she asked him.

"No, Patricia, there is no one to whom I could apply without betraying my condition and situation, and that would be fatal. Such a course would be equivalent to going broke; for when once a man loses his credit, even for an instant, in Wall Street, it is lost forever, never to be regained. People will tell you that there are exceptions to this, but I have been fifty years among the bulls and bears, and wolves, too, and I know better. When a man who occupies the position that I have held, and hold now, goes to the wall, it is the end."

During this statement, she had walked to one of the windows and stood silently looking out, for she wished to ask a question which her own intuition had already answered. She knew what the answer would be, but she did not quite know what form it would take. She felt that sort of misgiving which belongs only to women, and she feared that there was something beyond and behind, and perhaps beneath, all this present circumstance, which was being kept from her. For Patricia Langdon did know of one man who would go to her father's assistance, and she could not understand why he had not already applied to that person.

Presently, she returned to the table.

"Patricia," said her father, with some impatience, "I wish to the Lord you'd sit down. You make me nervous keeping on your feet all the while, and with those big eyes of yours fixed on your old dad's face as if they had discovered something new and strange in the lines of it."

She paid no heed to this remark—one would have supposed she did not hear it; but she asked:

"Will you tell me why you sent for me? and why you wished to consult with me?"

Again, the cigar was whipped sharply to the opposite corner of the old banker's mouth; and he replied quickly, almost savagely:

"Because I have thought of a way by which you can help me out."

His daughter caught her breath; it was a little gasp, barely audible; but she uttered only one word in reply. It was:

"How?"

For an instant, the banker hesitated at this abrupt question; then, with a suggestion of doggedness in his manner, he thrust forward his aggressive chin and shut his teeth so tightly together that the cigar, bitten squarely off, dropped unheeded upon the rug where he stood. By way of reply, he spoke a man's name.

"Roderick Duncan," he said, sharply.

Patricia did not seem to heed the strangeness of her father's reply, nor did she alter the expression of her eyes or features. She seemed to have anticipated what he would say. After a moment, she remarked quietly:

"I should think it very likely that Roderick would assist you in your extremity. I see no reason why he should not do so. His father was your partner in business. Indeed, I should regard it as his duty to come to your aid, in an extremity like this. But why, if I may venture to ask, was it necessary to consult me in regard to any application you might make to him?"

The old man did not reply; he remained silent, and continued doggedly to stare at his daughter. Presently, she asked him: "Have you already made such a request of Mr. Duncan?"

A smile took the place of the old man's frown; his face softened.

"No; that is to say, not exactly so," he replied.

"You have, perhaps, suggested the idea to him?"

Old Steve shrugged his shoulders, and dropped back into the chair, kicking away the half of the cigar in front of him as he did so.

"Yes," he said, "I have suggested the idea to him, and he met the suggestion more than half way, too. The reply he made to me is what brings your name into the question. If it were not for the fact that I know you to be fond of him, and that you are already half-promised—"

"Is that why you have sent for me?" She interrupted him with quiet dignity, although the expression of her eyes was suddenly stormy.

"Yes; it is."

"Would you please be more explicit? I am afraid that I do not clearly understand."

"Well, Pat, to put it in plain words, Roderick's answer implied that he would be only too delighted to advance the sum I require—twenty-million dollars—to his prospective father-in-law!"

Patricia stiffened where she stood. Her eyes fairly blazed with the sparks of anger they emitted. The hand that rested upon the table was clenched tightly, until the glove upon it burst. Otherwise, she showed no emotion.

"So, that is it," she said, presently. "Roderick Duncan has made a bid for me in the open market, has he? I am to be the collateral for a loan which you are to secure from him. Is that the idea? He has made use of your financial predicament to hasten matters with me. I understand—now!"

"Humph! Roderick would be very much astonished if he heard your description of the situation. He thought, and I thought, also—"

"But that is what it amounts to, isn't it?"

"Why, no, child; no, that is not what it amounts to, at all. You ought to know that. Roderick has loved you ever since you were boy and girl together, and you were always fond of him. His father and I both believed that some day you would marry. I know that Duncan has asked you time and time again, and I know, too, that you have never refused him. You have just put him off, again and again, that is all. You have played fast and loose with him until he is—"

"Wait, dad. There is one thing that you never knew; or, if you did know it once, you have forgotten what little you knew about it then. I refer to a woman's heart. You ignored that part of me when you made your bargain. You forgot my pride, too. It is quite true that I have been fond of Roderick Duncan, all my life. It is equally true that he has asked me to be his wife, and that I have seriously considered his proposals. It is even true that I have thought of myself as his wife, that I have tried to believe that I loved him. All that is true, quite true—too true, indeed. But now—How dared you two discuss me, in the manner you have?" She blazed forth at her father suddenly, forgetting her studied calm. "Oh, I read you correctly when I first entered this room. I could see, even then, that some plot was afoot. But I never guessed—good heaven! who could have guessed?—that it was anything like this. Do you realize what you have done? Your words, thus far, have only implied it, but I know! Shall I tell you?"

"My dear—!"

"You have found yourself in this financial muddle—if, indeed, it is true that you are in one—and—"

"It is quite true."

"So much the worse for making me the victim of it. You have applied to Roderick Duncan for some of his millions; and you two, together, have discovered in the incident a means of coercing me. Oh, it is plain enough. You are a poor dissembler in a matter of this kind, however excellent you may be in others. I see it all, now, as clearly as if you had expressed it in words. You have asked Roderick, by intimation, if not in actual words, to go to your assistance to the amount of so many millions; and he, the man who professes to love me, whom I have thought I loved—he has, as bluntly, replied—oh, it is too terrible to contemplate!—he has told you that if I will hasten my decision, if I will give my consent at once to the wedding he proposes, he will supply the cash you need. You offer your daughter, as security for the loan; he accepts the collateral! That is the exact situation, isn't it?"

"I suppose it is about that, although you put it rather brutally," he replied.

"Brutally!" she laughed. "Why, dad, is not that the way to put it? Horses and cattle are bought and sold at auction, knocked down to the highest bidder, or purchased at a private sale. The stocks and bonds and securities in which you deal are handled in precisely the same way. And now, when you are in an extremity, when your back is to the wall, a man whom I had always supposed to be at least a gentleman calmly makes a bid for your daughter, and you, my father, are willing to sell! Is not brutality the fitting word for you both? It seems so to me."

"Look here, Pat—"

"Stop, father; let me finish."

The old man shrugged his shoulders, and the daughter continued:

"It is a habit with people to say, 'If I were in your place I should' do so-and-so. I tell you, had I been in your place when such a suggestion as that one was made I should have struck the man in the face; but you see in me a value which I did not know I possessed. My father, who has been my chum since I was a child, is willing to dispose of his daughter for dollars and cents. And a man whom I have infinitely respected, calmly offers to make the purchase." Patricia clenched her hands and glared stormily at her father. Then, when he made no reply, she turned and walked to the window, staring out of it for a moment, while the old man remained silently in his chair, knowing that it were better for him not to speak, until the first violence of the storm had passed. He knew this daughter of his, or thought he did; but he was presently to discover that he was less wise than he had supposed. After a little, she returned and stood beside him, leaning against the table with her hands behind her, clenching it; but her words came calmly enough, when she spoke.

The old man raised his eyes to hers, as she approached him, and his own widened with amazement when he studied his daughter's face with that quick and penetrating glance which could read so unerringly the operators of Wall street. He could not comprehend precisely what it was that he saw in Patricia's face at this moment—only, he realized it to be the expression of some kind of settled purpose. He had never seen her thus before. Her strangely beautiful eyes had never blazed into his in just this way. He had seen her tempers and had contended against them, more or less, since she was left to his sole care, at her birth; but this attitude assumed now was new to him. Stephen Langdon knew, by his knowledge of himself, that Patricia was like him; but here was something new, strange, almost unreal. He wondered at it, shrank from it, not knowing what it was. Settled purpose was all that he was enabled to recognize. But what sort of settled purpose? What was it that his daughter had decided upon?

He was not long in doubt. Her words were sufficiently direct, if the hidden purpose behind their outward meaning was not.

"Father," she said, with distinct calmness, "I will use a phrase that is familiar to you. It seems to fit the occasion. You may tell Roderick Duncan that you will deliver the goods! Tell him to have the twenty millions ready for you to deposit in your bank at ten o'clock Monday morning, and that you will be ready with the collateral he demands."

"But, Patricia, my daughter, you take an unjust view of—"

"Stop, father! He must be told still more: he must be told that the collateral, having certain rights and values of its own, will insist upon a few stated conditions; and when the bargain is concluded, at ten o'clock Monday morning, Mr. Duncan must first have accepted those conditions."

She walked around to the other side of the table again and faced her father across it; then she added, slowly and coolly:

"There must be a legal form of document drawn, in this transaction, and it must be signed, sealed and delivered exactly as would be done if the collateral offered, and the thing ultimately to be sold in this instance, were the stocks and bonds in which you usually deal. He must agree, in this document, that on the wedding day the woman he buys must receive an additional sum in her own name, of ten million dollars. One as rich as he is known to be will not object to a pittance like that. You can make your own arrangements with him concerning the loan of the twenty millions to you, the interest it draws, and when the sum will be due; but the consideration paid for me, to me, must be absolute, and in cash, before the marriage-ceremony."

She turned quickly and strode to the end of the room. There, she threw open that door which has been described as communicating with the inner sanctum of the banker, and standing at the threshold, she said, in the cold, even tone in which she had pronounced the ultimatum to her father:

"I have surmised that you are in this room, Roderick Duncan. If I am correct, you may come out, now, and conclude the terms of your purchase. Do not speak to me here, and now. It would not be wise to do so. You have heard, doubtless, all that has been said in this room."

She turned again, and before Stephen Langdon could intervene, had passed him, going into the main office of the suite, and thence to the street.

Outside the Langdon building was a waiting automobile which had taken Patricia to the office of her father for that interview, the purport of which she had not then even vaguely guessed. Under the steering-wheel of the waiting car was seated a young man, smoothed-faced, keen of eye, strong-limbed, and muscular in every motion that he made. A pair of expressive hazel eyes that seemed to take in everything at a glance, looked out from his handsome, clean-cut face, the attractiveness of which was augmented rather than marred by the strong, almost square chin, and the firm but perfectly formed lips, just thin enough to show determination of character, yet sufficiently mobile to suggest that the man himself, though young in years, had met with wide experiences. His personality was that of a man prepared to face any emergency or danger that might arise, and to meet it with a smile of entire self-confidence in his ability to overcome it. The rear seats of the waiting car were occupied by two young ladies, friends of Patricia; and the three were laughing and talking together when Stephen Langdon's daughter approached them. She did not wait to be assisted, but sprang lightly into the seat beside the young man who has just been described; and she said rather shortly, for she was still angry:

"Please, take me home, now, Mr. Morton."

He turned to face her, meeting her stormy eyes laughingly; and exclaimed:

"Gee! Miss Langdon, you sure do look as if you'd been having a run-in with the governor. I'd hate mightily to meet up with you, if I were alone and unprotected, and you were as plumb sore at me, as you are now at somebody you have just left inside that building. I sure would. Yes, indeed!"

He chuckled audibly as the car started forward toward Broadway. For a time, he gave his entire attention to the management of the car, purposely ignoring the young woman who was seated beside him, for notwithstanding the fact that he had chaffed her about the anger in her eyes, he was fully aware that she had met with an unpleasant experience of some sort, while he and the others were waiting outside the building.

The hiatus offered sufficient time for Miss Langdon entirely to recover her equanimity, and when at last Richard Morton's glance again sought her, he met the same cold, calm, unflinching gaze from her beautiful eyes that he had discovered there less than two weeks before, and, since, had never been able to forget for a single moment.

"Miss Langdon," he said, with his characteristic smile, "if you had been raised out west, in the country where I come from, you sure would have been bad medicine for anybody who tried your temper a little bit too far."

"What do you mean by that?" she asked him, quickly, but without offense. She was smiling now, and Morton's colloquialisms always interested her.

"Well, I mean a lot—and then some. If you'd been raised with a gun on your hip, and had been born a man instead of a woman, I reckon you'd have been an unsafe proposition to r'il. You certainly did look mad when you came out of that office-building; and the only regret I feel about it, is that I didn't stand within comfortable easy reach of the gazabo that made you feel like that. One of us would—have gone out through the window."

"It was my father," she said, simply, but smilingly.

"Oh! was it? Well, even so, I'm afraid I wouldn't be much of a respecter of persons, if you happened to be on the other side of the scales. I reckon your dad wouldn't look bigger than any other man. Have you forgotten what I said to you the second time I ever saw you?"

"No," she replied, gently, "I haven't forgotten it, and I never will forget it; but I must remind you of your promise to me, at that same meeting."

"Won't you call it off for just five minutes, Miss Langdon?" he asked in a low tone which had begun to vibrate with emotion. "Just call it off for one minute, if you won't let it go for five. It sure is hard to sit here, alongside of you, and not only to keep my hands and eyes away from you, but to keep my tongue cinched with a diamond hitch. I suppose I am hasty, and a mighty sight too previous for your customs here in the East, but I can't see why you won't take up with a chap like me; and, besides—"

"Mr. Morton!" She turned to him unsmilingly, her eyes cold and serious, and she spoke in a tone so low that even the sound of it could not extend to the young ladies who occupied the rear seats in the tonneau. "It is my duty to tell you that I have just become a willing party—a willing party, please understand—to a business transaction, by the terms of which I am now the affianced wife of—" Patricia paused abruptly. Morton, still guiding the machine delicately in and out through the traffic of the street, turned a shade paler under his sun-burned skin, and Patricia could see that his hand gripped almost fiercely upon the steering-wheel. She realized that he had understood the important part of what she had said, and she did not complete the unfinished sentence. There was a considerable silence before either of them spoke again, and then Morton asked calmly, but in a voice that was so changed as to be scarcely recognizable:

"Of whom, Patricia?" He made use of her given name unconsciously, and if she noticed the slip, she did not heed it.

"I need not mention the gentleman's name," she told him. "It is unnecessary."

"What do you mean by referring to it as a business transaction?" he demanded, turning his face toward hers for an instant, and showing an angry glitter in his eyes. "If it is something that was forced upon you—"

"I meant—it doesn't matter what I meant, Mr. Morton."

For just one instant, he flashed his eyes upon her again, and she saw the lines of determination harden upon his face.

"It sounded mighty strange to me," he said, quietly, but with studied persistence. "I don't mind confessing that I can't quite savvy its meaning. I didn't know that 'business transaction,' was a stock expression here, in the East, in connection with an engagement party. But I suppose I'm plumb ignorant. I feel so, anyhow."

"You have forgotten one thing, Mr. Morton; you have forgotten that I used the words, 'a willing party.'" She spoke calmly, half-smiling; but he was still insistent.

"Did you mean by their use that I am to understand that the circumstance meets with your entire approval?" he asked, slowly and with distinctness. A heavy frown was gathering on his brows.

"Yes; quite so."

"Do you love the man who is the other party to the—er—business transaction?" This time, he turned his head and looked squarely at her, gazed with his serious hazel eyes, deep into her darker ones—gazed searchingly and longingly.

"You have no right to ask me such a question as that," she told him.

"I beg your pardon, Miss Langdon." He turned his eyes to the front again; "but I think I have a distinct right to do so, and I don't believe it is your privilege to deny it. I have loved you from the first moment I saw you. Please, don't interrupt me now, for I must say the few words I have in mind. I'll not look at you. The others won't hear me. By reason of my great love for you, even though there is no response in your heart for me, I certainly have the right to ask that question; and, also, I believe I have the right to demand an answer. If you love that other man, and if you will tell me that you do, I shall have nothing more to say; but if you do not love him, you shall not be his wife so long as I have my two hands and can remember how to hold a gun." It sounded theatrical, but he did not mean it so; and a "gun" and its use, was the strongest form of expression he could think of, at that moment. It had formed the court of last resort throughout his youth in the great West, and just now he felt that the expression fitted the present case admirably. What reply Patricia might have made to this characteristic statement by the young Montana ranchman will never be known, for at that instant they were interrupted by the other passengers of the car, who sought to draw Patricia into conversation with them.

She accepted the interruption gratefully as well as gracefully; it offered an easy escape from a trying situation, and it was not until the car was drawn up in front of the door of her own home and she was about to leave it that she spoke again with Morton, save in a general way. Now, he leaned quickly nearer to her and said, in a tone so low that the others could not hear:

"I shall call upon you to-morrow evening—Sunday—if I may." Then he laughed and, with narrowed eyelids, added: "I'll come to the house whether I may or not. But you will receive me, won't you? Say that you will!" And Patricia nodded brightly, in reply, as she crossed the pavement toward the front steps of her father's princely mansion. At the door, she paused and looked after the car as it rolled up the avenue; and, with a half-smile of troubled perplexity, she murmured:

"I wish, now, that I had not given my word to that 'business transaction.' Richard Morton might have offered a better solution of my problem. Only, it would have been unfair—and cruel; and I have never been either the one, or the other; never, yet!" Then, she passed into the house.

Downtown in the private office of Stephen Langdon, Roderick Duncan stepped from the inner sanctum into the presence of the banker just as the latter started to his feet after the sudden and unexpected departure of his daughter. For an interval, the young man and the old faced each other in silence, the latter with a cynical and satirical smile on his strong face, the former with an unmistakable frown of anger.

"You're a darned old fool, Langdon!" Duncan exclaimed hotly, after that pause; and he clenched his hands until his knuckles turned white under the strain, half-raising the right one, until it seemed as if he intended to strike a blow with it. But Patricia's father gave no heed to the gesture. Instead, he dropped back upon his chair, and laughed aloud, ere he replied:

"I suspect, my boy, that there is a pair of us."

ONE WOMAN WHO DARED

These two men, the banker who had weathered so many financial storms of "the street" and had inevitably issued from the wreckage unscathed and buoyant, and the young multi-millionaire who faced him with uplifted hand even after the former returned to his chair, were exact opposites in everything save wealth alone. Roderick Duncan, son and heir of Stephen Langdon's former partner, was the possessor, by inheritance, of one of those colossal fortunes which are expressed in so many figures that the average man ceases to contemplate their meaning. Nevertheless, Duncan had kept himself clean and straight. In person, he was tall, handsome, distinguished in appearance, and genuinely a fine specimen of young American manhood. The older man regarded him with undoubted approval, and affection, too, while Duncan lowered the partly uplifted arm, and permitted the anger to die out of his face slowly. But there remained a decidedly troubled expression in his gray eyes, and there were two straight lines between his brows—lines of anxiety which would not disappear, wholly. He was plainly perplexed and, also, as plainly frightened by the almost tragic climax that had just occurred.

The elder man, whose face was always a mask save when he was alone with his daughter, or with this young man who now stood before him, had been at first angered by the words and conduct of Patricia. But the exclamation uttered by the young Crœsus impressed him ludicrously, notwithstanding the financial straits he was supposed to be in, and he grinned broadly into the anxious face that glowered upon him. Langdon's heart was not at stake; he had no woman's love to lose, or even to risk losing; and so far as the financial character of his troubles was concerned, he knew that Roderick Duncan would provide the millions he needed, in any case. That fact was not dependant upon any whim of Patricia's. Langdon could afford to laugh, believing that the rupture in the relations of these young people would be healed quickly. The old man did desire that the two should marry; he wished it more than anything else, save possibly the winning of his "street" contests.

It was the younger man who broke the silence. He did it first by striking a match on the sole of his shoe and lighting a cigar; then by crossing to one of the chairs at the oblong table, into which he literally threw himself; and as he did this, he exclaimed, with an expression of petulance that might have belonged to a boy better than to a man:

"Well, you've made a mess of it, haven't you? You have got us both into a very devil of a fix. I ought to have shot you, or myself, before I consented to such a fool plan as that one was. Oh, yes; we're in a fix all right!"

"How so?" asked the old man, rising and selecting a chair at the opposite side of the table, and calmly lighting a fresh cigar, while he swung one leg across the corner of the solid piece of furniture.

"Patricia won't stand for that little scheme of yours, not for a minute; and you know it, Uncle Steve." This was an affectionate term of familiarity which Duncan sometimes used in addressing Patricia's father. "I was afraid of it when you proposed it, but I allowed myself, like an idiot, to be influenced by you. I tell you, Langdon, she won't stand for it; not for a minute. I have made her angry, many times before now, but I have never known her to be quite so contemptuously angered."

"No," said Langdon, and he chuckled audibly. "I agree with you. I think my little girl is going to make it hot for you before we are through with this deal. In fact, I shouldn't wonder if she made it warm for both of us. She is like her old dad about one thing—she won't be driven."

The younger man said something under his breath which, because it was not audible to his companion, need not be repeated here; but it was probably not an expression that he would have used in polite society. He drummed on the table with his fingertips, and smoked savagely.

"You're mighty cheerful about it, aren't you?" he demanded, with sarcastic emphasis. "What I want to know is, how are we going to fix it up?"

"Fix what up?"

"Why, this business about collateral, and all that rot, with Patricia. How are we going to square ourselves? That's what I'd like to know! Maybe you can see a way out of it, but I'm darned if I can."

The banker took the cigar from his mouth, flicked the ashes into the cuspidor, removed his leg from the table, and replied calmly, with a half-smile:

"It looks to me as if it were all fixed up, now. Patricia has agreed to marry you all right; she told me in plain English that I could deliver the goods. You heard her, didn't you? As far as I can see, she has only raised the ante just a little—a small matter of ten millions, which you won't mind at all. What's the matter with you, anyhow? You get what you wanted—Patricia's consent to an early marriage." The old man grinned maddeningly at his companion.

"Confound you!" shouted Duncan, starting to his feet, and he smashed one hand down upon the top of the table, in the intensity of the resentment he felt at this remark.

"Do you suppose—damn you!—that I want her like that? Can't you see how the whole thing outraged her? She hates me now, with every fibre of her being. She hates me, and you, too, for this day's work!"

Langdon shrugged his shoulders.

"You want her, don't you?" he asked, placidly, as if he were inquiring about a quotation on 'change.

"Of course, I want her. God only knows how greatly I want her."

"Well, you get her, don't you, by this transaction? She'll keep the terms of the agreement. She's enough like me for that. She said I could deliver the goods. She meant it, too. You get her, don't you?"

"Yes—but how?" was the sulky reply. "How do I get her? What will she do to me, after I do get her? Tell me that, confound you!"

The old man chuckled again. "I am not a mind-reader," he said.

"What will she do to me, Uncle Steve? What did she threaten? What am I to expect from her, now?"

"Oh, I don't know. I confess that I don't. Sometimes, Patricia is a little too much for the old man, Roderick," he added, wistfully. Then, with another change of manner, he exclaimed: "But you get her! And I get the twenty-millions credit. What more can either of us ask? Eh?"

"The twenty millions have nothing to do with it, and you know it. They never did have anything to do with it, and you know that, also. It was only your cursed suggestion, that we should make her promise to marry me the condition of keeping you from failure. You know as well as I do that there is nothing belonging to me which you cannot have at any time, for the asking; and that you do not stand, and have not stood, in any more danger of failure than I do."

"I would have failed if I had not known where to get the credit for the twenty millions," the banker remarked, quietly.

"Yes; but—confound it—you did know. You only had to ask me. But instead of doing it in a straight, business-like way, you set that horrible fly to buzzing in my ears, that we could make use of the circumstance to compel Patricia to an immediate consent. And I, like a fool, listened to you. Patricia never meant not to marry me; but now—!"

He strode across the floor, then back again to his chair and flung himself into it. The old man watched him warily, keen-eyed, observant, and with a certain expression of fondness that no one but his daughter and this young man had ever compelled from him. But, presently, he emitted another chuckling laugh; and said:

"That was a sharp stroke of hers to have the ten millions paid over to her. It was worthy of her old dad; eh? She is a bright one, all right. She's a chip off the old block, my boy. I couldn't have done it better, myself."

"Damn you!" Duncan exclaimed, and he sprang to his feet, grasped his hat, and rushed from the office to the street with much more apparent excitement than Patricia herself had shown. He had the feeling that he had allowed himself to be tricked into the commission of an unmanly act, and he was thoroughly ashamed of it.

Stephen Langdon, left alone, chuckled again, although his face quickly fell into that reposeful, mask-like expression which was habitual to it—an expression not to be changed by the loss or gain of millions. He remained for a time quietly in the chair he had been occupying, but soon he rose and crossed to his desk, throwing back the top of it. He pulled a bundle of papers from one of the pigeonholes and calmly examined certain portions of them. He glanced over three letters left there by his stenographer for him to sign and post. These he signed, and after enclosing them in their respective envelopes, dropped them lightly into a side-pocket of his coat. Then, he pulled toward him the bracket that held the telephone, and placed the receiver against his ear. Having presently secured the desired number, he said:

"I wish to speak with Mr. Melvin, personally."

"Mr. Melvin is not in his office at the present moment," came the reply over the telephone. "Who is it, please?"

"This is Stephen Langdon, and I wanted to speak—"

He was interrupted by the person at the other end of the wire, who uttered an exclamation of surprise, followed by these words:

"Why, Mr. Langdon, Mr. Melvin has gone to your house to see you, as we supposed. A telephone call came from your residence, and he departed at once, saying that he would not return to the office to-day."

"The devil he did!" exclaimed the banker, as he hung up the receiver. Then, he leaned back in his chair and smoked hard for a moment, with the nearest approach to a frown that had appeared on his face during all that exciting afternoon; and he did another thing unusual with him: he spoke aloud his thoughts, with no one but himself for listener.

"I'll be blowed if I thought Patricia would go as far as that!" was what he said. "If she hasn't sent for Malcolm Melvin to draw those papers she hinted at, I'm a Dutchman! By Jove, I begin to think that Duncan was right after all, and that he is up against it in this little play we have had this afternoon. But I hadn't an idea that my girl would go quite so far. H'm! It looks as if it is up to me to spoil her interview with Melvin, if I can get there in time."

Five minutes later, he left the banking-house, paused at a letter-box long enough to drop in the correspondence he had signed, and then went swiftly onward to the subway, by which he was conveyed rapidly to the vicinity of his home. Somewhat later, when he entered the sumptuously appointed library, he discovered precisely what he had expected to find: his lawyer, Malcolm Melvin, and his daughter Patricia were facing each other across the table, the former having before him several sheets of paper, which were already covered with the penciled notes and memoranda he had evidently been engaged in making.

Langdon stopped in the middle of the floor and looked at them. For the first time since the beginning of the interview with his daughter at the office, he realized that she had been in deadly earnest at its close. He understood, suddenly, how deeply her pride had been wounded, and he knew that she was enough like himself to resent it with all the power she could command.

"Since when, Melvin, have you ceased to be my attorney!" he inquired sharply, determined to put an end to the scene, at once.

The elderly lawyer and the young woman had raised their heads from earnest conversation when Stephen Langdon entered the room. The lawyer, with a startled, although amused, expression on his professional face; the daughter with a cold smile and an almost imperceptible nod of her shapely, Junoesque head. But her black eyes snapped with something very nearly approaching defiance, and she replied, before Melvin could do so:

"Do not misunderstand the situation, please," she said, quickly. And her father noticed with deep misgiving that she omitted the customary term of endearment between them. "Mr. Melvin is here at my request, and because he is your attorney. I have been instructing him how to draw the papers that are to accompany the collateral offered for your loan, and the bonus that goes with it; and just how those papers are to be used, in accordance with the discussion between you and me, at the bank, this afternoon. I told you, then, to inform Mr. Duncan that you would meet his requirements. Later, when I realized that he had overheard us—"

"What's the matter with you, Pat?" demanded the father, interrupting her with a touch of anger. "Have you lost your head, entirely?"

"No," she replied, with utter calmness; "I have only lost my Dad. I went down to his office this afternoon to see him, and I left him there. Just now, I have been instructing Mr. Melvin concerning the particulars of the agreement I want drawn and signed in the transaction that is to take place between you and Roderick Duncan, in which I am, personally, so deeply concerned, in which I am to figure as the collateral security."

The old man stared at his daughter, with an expression that had made many a Wall-street financier turn pale with apprehension. It was a grim visage that she saw then—hard and set, stern and unrelenting, and many a strong man had surrendered to Stephen Langdon, frightened by the aspect of it. Not so this daughter of his. She met his gaze unflinchingly and calmly, without a change in her outward demeanor. After a moment, Langdon turned with a shrug toward the lawyer.

"Melvin," he said, "how many years have you been my attorney?"

"Fourteen, I think, Mr. Langdon," was the smiling reply. One would have thought that the man of law found something highly amusing in this incident.

"About that—yes. Well, do you see that door?" He half-turned and indicated the entrance he had just used. "Melvin, I want you to pick up those papers and tell John, outside, to give you your hat; then I want you to get out of here as quick as God'll let you. If you don't, our relations are severed from this moment. And if you complete the draft of those papers, without my permission, or submit them to any person whatever, without my having seen them first, I will have another attorney to replace you, Monday morning. Go right along now. You needn't answer me. If you don't want my business, all you've got to do is to say so. If you do want it, you'll come mighty near doing what I have told you to do, just now."

The lawyer, quietly, but with dignity, rose from his chair, folded the papers, placed them in an inner pocket of his coat, bowed to Patricia and then to her father, and without a word passed from the room, closing the door quietly behind him; but before he quite accomplished this last act, the clear even tones of the girl called after him:

"I am sure, Mr. Melvin, that we had quite concluded our conference. I will ask you please to draw those papers as I have directed. You may submit copies to Mr. Langdon at the time you bring the originals to me."

He did not answer, for there was no occasion to do so, and a second later Stephen Langdon and his daughter were alone together for the second time that afternoon.

"Now, Patricia," he said, turning toward her, with his feet wide apart and his hands thrust deep into his trousers-pockets, "what in blazes is this all about?"

His daughter replied coldly and precisely:

"I have merely been dictating to your lawyer the substance of the conditions I wish to have embodied in the papers that are to complete the transaction we have discussed at your office. I selected Mr. Melvin because I knew him to be in your confidence, and I surmised that you would prefer that the condition of affairs under which you are now struggling, which forces you to borrow twenty-million dollars, should not be made known to an outsider."

"Well, I'll tell you that I won't hear of it! It's got to stop right now. I won't have those papers drawn at all. I won't have it. The whole thing is preposterous, and you seem to be determined to make a fool of yourself. I won't have it!"

"But you must have it," she said, quietly.

"Must have it? Patricia, there isn't a man in the city of New York who dares to say that to me."

"Possibly not, sir; but there is a woman in New York who dares to say it to you, and who does say it, here and now. That woman is, unfortunately, your daughter."

"Patricia! Are you crazy?"

"No; but I am more hurt and angry, more outraged and incensed, than I believed it possible ever to be. I shall insist upon the drawing of those papers, and the fulfillment of the stipulations I have directed. If you are determined that Mr. Melvin shall not finish what he has begun for me, I shall select another lawyer, and shall have the papers drawn just the same."

"But, my child, it is all foolishness. The papers are not necessary. Roderick will supply what cash I need without anything of that sort, and you know it!"

"Am I to understand, sir, that you have lied to me?"

Langdon dropped upon a chair, breathing an oath which his daughter did not hear, and she continued, without awaiting a reply from him:

"You have taught me, since I was a child, that in a business transaction in the Street, where there is no time for the drawing of papers, a man must live up to his word, absolutely. I took you seriously in what occurred at your office this afternoon. I surmised, when we were near the end of our interview,—nay, I assumed it—that Roderick Duncan was inside the inner office. My surmise proved to be true, and now I have only this to say: We shall carry out the transaction precisely as it was stipulated between us, and according to the papers I have dictated to Mr. Melvin, or I shall go to another lawyer and have those same papers drawn and offered to you and to Mr. Duncan, for your signatures. He overheard our conversation, and thus became a party to it. I was forced into the situation without my consent, and I shall now insist upon a certain recognition of my rights in the matter. If you choose to deny me those rights, the fact will not deter me from proceeding in my own way—a way which Mr. Melvin, your attorney, thoroughly understands. I have explained it fully to him."

The old man leaned back in his chair, glaring at his daughter, and yet in that burning gaze of his there was undoubted admiration. He liked her pluck, and deep down in his heart he gloried in her ability to maintain the position she had assumed, where she literally held him helpless. For it would never do that she should be permitted to go to another lawyer; such a proceeding would betray to other parties the financial embarrassment into which he had been drawn. The news would get out. There would be a whisper here, a murmur there, and before noon on Monday, all New York would know it. His daughter understood her momentary power over him, and she was determined to make the most of it.

Patricia returned her father's gaze for a moment, then turned negligently away and moved toward the door.

"Wait," he called to her.

"Well?" She stopped, and half-turned.

"Don't you know, girl, that the whole business was tomfoolery?"

"No; and I would not believe you, or Mr. Duncan—now."

"Wait just a minute longer, Patricia; let me explain this thing to you, fully. Let me make you understand just how it came about," her father exclaimed. "It was all a mistake, you know, and I must confess that the mistake was mostly mine. Of course, Roderick was ready to let me have the twenty millions, or fifty if I had asked for them. There was never any doubt about that, and could have been none. He has the money, and there never has been a time, since he inherited it, when I could not use it as if it were my own. You knew that. I have never hesitated to go to him, either. That is why I went to him to-day. Before I had an opportunity to explain the purpose of my call, he asked about you, and the question suggested to my mind the idea of utilizing the desperate situation I was in to hasten your marriage to him. You know how I have looked forward to that. I have known, or at least I have supposed I knew, for years, that you thought more of him than of anyone else. You are twenty years old now; it is high time that you were married, and it would break my old heart to see you take up with any of those society-beaux who hover around you at every function where you appear. On the other hand, I shall be very glad when you are Roderick Duncan's wife. He is the son of the best friend I ever had, the only man I ever trusted. And he is every bit as good a man as his father was. He is square and on the level. He has wealth, and he doesn't go bumming around town, giving champagne parties, and monkey dinners. He knows how to be a good fellow without making a fool of himself, and that is more than you can say of most young men who have money to burn. You have grown up together, and why in the world you have kept putting him off is more than I can guess. Besides all that, he is easily worth a hundred millions. But this has nothing to do with the present question. I want you to have him, and I want him to have you; and if he didn't have a dollar in the world, I should feel just the same about it. All that happened to-day was at my instigation; not at his. And now, daughter, you must find it in your heart to forgive him—and me."

She listened to him to the end, quietly and outwardly unmoved. When he concluded, she replied in the same even tone she had used ever since her father entered the library:

"I don't know, and I don't care to know, any of the particulars regarding how the arrangement came about between you and Mr. Duncan. What I do know is this: the arrangement was made between you, and was agreed upon between you. I was called in, to be consulted, at your private office, with the third interested party concealed like a spy in an inner room. I agreed to the transaction as I understood it. I will carry it out as I agreed to do, while at your office, and in no other way. If Roderick Duncan wishes to make me his wife, he must do it according to the stipulations I have dictated to Mr. Melvin, this afternoon, or he can never do it at all. That, sir, is all I have to say."

She turned and went from the room, closing the door behind her as softly as the lawyer had done.

The old man slipped down more deeply into his chair, covered his eyes with one hand, and murmured, audibly:

"I have had to live almost seventy years to find out that, after all, I am nothing but an old fool."

A STRANGE BETROTHAL

When dinner was served at seven that Saturday evening, the banker and his daughter faced each other in silence across the table. There was no wife and mother in this money-king's family, for she had passed out of life when Patricia came into the world. This, perhaps, may account for the close intimacy that had always existed in the relations of father and daughter, between whom there had never been any break or shadow, until this particular Saturday afternoon.

"Old Steve," iron-faced, heavy jawed, and steady of eye, wore his Wall-street mask at this particular dinner; and he wore it as grimly as ever he did when encountering a financial storm or a threatened panic. He felt that he had more to conceal, just now, than any financial problem could ever compel him to face. He was no longer "dad." Patricia had practically omitted the use of even the less endearing term of father; but whether intentionally or not, even the shrewd old banker could not determine. For years, he had forgotten that he had a heart, save when he and his daughter were alone together. The money whirlpool of the financial section of the city had made him colder of aspect, harder in nature, and less considerate of the feelings of others. It had never even remotely occurred to him that there could be any rupture between himself and Patricia, or that a yawning gulf, like this one was, could separate them.

But now there was one, and he recognized its breadth and its depth. He knew that he could not cross it to her, and that it would never be bridged, save by Patricia herself. He had offended her beyond forgiveness, almost. He had not entirely realized that Patricia's nature and characteristics were so like his own, save only where they were feminine instead of masculine, that she would now adopt the course he would have pursued under circumstances which might, by a stretch of the imagination, be called parallel.

Patricia's face was almost as mask-like as her father's, save that her great, dark eyes were stormy in their depths, and would have suggested to one who had sailed the Southern seas the brooding and far away approach of a monsoon. Her olive-tinted skin had in it a suggestion of pallor; but only a suggestion. When she spoke at all it was to John, the butler who served them; and then it was always in her accustomed low, evenly modulated tone. Not perceptibly different to the butler were her tone and manner, and yet even the servant, wise in his generation, sensed the unsettled condition of things, and moved about like a phantom; perhaps also he was a trifle more assiduous than usual in his efforts at perfect service.

Patricia ate sparingly, but bravely. There was nothing of the shrinking or pouting, or even of the petulant, in her character. Her father ate nothing at all. He dawdled with his soup, turned his fish over and sent it away, and sniffed contemptuously at everything else that was placed before him. He made his dinner of coffee and cognac, and seemed to be greatly interested while he burned the latter over three dominoes of sugar.

When the moment came to leave the table, there had been no word exchanged between them; but then, with an effort, the banker assumed his brightest and most kindly tone; and he asked, cheerily:

"Well, what have you on for to-night, my dear?"

"Nothing at all," she replied, indifferently, as if the question held no interest for her—as, indeed, it did not, for the moment; but she followed him from the dining-room into the library, as was their usual custom whenever they had dined alone. Now, as they entered it, the banker, with an assumption of high spirits he did not feel, remarked:

"If you don't object to a Saturday-night opera, Garden is singing 'Salome' at the Manhattan to-night, and I should like to hear it. Will you go, with your old dad?"

"No, thank you," she replied, indifferently. "I shall remain at home."

She was standing at the table, turning the leaves of a magazine, and her father glanced keenly at her across the intervening space, while he lighted a cigar. Then, with a shrug of his shoulders, and a sigh which could not have been seen or heard, and which only he himself knew to have existed, he crossed the floor. As he was passing from the room, he said, as indifferently as she had spoken:

"Then, I suppose, I will have to take it in, alone."

"You might ask Roderick to go with you," she threw at him, as he passed into the hallway; but Langdon pretended not to hear, for he called back at her:

"I'll get Beatrice, I think, and ask her to play daughter for me; eh?"

Patricia made no comment upon this suggestion; but having awaited, where she was, the sound of the closing outer door, she slowly crossed the room.

The drop-light at her favorite chair was adjusted, and she began the reading of a new book which someone had placed on the table beside it. She read on and on, apparently with interest, but really without knowing at all what she did read, until more than an hour had passed; and then a card was brought to her.

She glanced at it, although she believed she knew perfectly well what name it bore, before she did so. Her lips tightened for an instant, and she frowned ever so little. But she said to the footman:

"You may bring Mr. Duncan here, James."

Patricia did not rise from her chair when her caller entered the library. Duncan moved toward her eagerly, but meeting her eyes, which she raised quite calmly to his as he crossed the floor, he paused, and remained at about midway of the distance.

"Good evening, Patricia," he said. "I'm awfully glad to have found you at home. I was afraid you might go out before I could get here."

"I expected you," she told him, without returning his salute. "I have been expecting you for an hour. In fact, I have been waiting for you."

"That is very pleasant news, indeed, Patricia." Duncan was startled by it, however. He had not expected it, and he did not quite like the tone in which Patricia uttered it.

"I am glad you take it so," she returned. "It was not pleasant for me to wait for you, and it is not distinctly agreeable to me to receive you. But I believed that you would think it necessary to call, in order to make some effort at explaining the occurrences of this afternoon. Let me tell you, before you begin, that there exists no necessity for any sort of explanation. My father has fulfilled that duty quite fully, and I listened to him, throughout. He has exonerated you—"

Duncan took a hasty step toward her, but stopped again, even more abruptly than before, repelled by the cold barrier that the expression of her dark eyes built up between them. Whatever it was that he had in mind to say remained unspoken. He turned away and sought a chair opposite her, ten feet away, utterly repelled, for although these two had grown to manhood and womanhood together, she had always had the power to lift a sudden barrier between them. Though he believed he knew every mood and characteristic of this proud young woman, just now, for the first time within his recollection, there was a strangeness about her that he could not fathom. Long habit had made him almost as much at home in this house, as in his own. He had been, ever since he could remember, considered and treated like a member of the family. And so, now, before seating himself, he sought to put himself more at ease by indulging in a liberty which had always been accorded to him. He selected a cigar from Stephen Langdon's box, and lighted it. Then, remembering that conditions were changed, he threw it down with an angry gesture, upon a receptacle for ashes that was on the table. Patricia watched all these proceedings, unmoved.

"Patsy!" he exclaimed, abruptly, making use of an expression of their childhood; and he would have continued with rapid speech, had she not made a quick gesture of aversion that interrupted him. Then, she said, quietly:

"I would prefer, if you don't mind, that you should henceforth use my full name in addressing me."

"Patricia, you have just told me that your father has exonerated me; and if that is so, why do you receive me in just this manner? I need exoneration, all right; and I deserve it, too, for honestly, dear, I never thought of offending you. I thought, until the last moment, that you would take it all as a huge joke. It never occurred to me that you would be so deeply wounded. I should never have agreed to the crazy compact that your father and I made together, if I had realized the seriousness of it."

"No," she replied, quietly. "You should not have agreed to it. It was the mistake of your life, and, perhaps, of mine."

"You know how I love you, dear," he began, half-starting from his chair. But the expression of her eyes, without the slightest motion otherwise, made him pause again, without completing what he had started to say.

"It is best that we should be quite frank with each other," she said, calmly. "That is why I waited so patiently for you, to-night. Please do not interrupt me; let me say what I have in mind to say to you."

"I would like it much better if you would hit me over the head with one of those bronze ornaments, as you would have done ten or twelve years ago; or if you would fly into one of your tempers just as you used to do, Patricia. I would like anything better than this cold calmness. It makes me shudder; it freezes me; it fills me with apprehension. I love you so, dear! and I have loved you all my life. You know it; I don't need to tell you! And if I have made a mistake, surely you can find it in your heart to forgive, because of my great love? No, I will not stop," he ejaculated, when she made a gesture of impatience. "I will finish what I have to say, even braving your anger to do so. I would like to make you angry just now, Patricia. I would delight to see you in one of those tantrums of fury that you used to have when you and I were children together. Do you remember that I bear a scar now, inflicted by a tennis-racket in your hand, when you were ten years old? I think more of that scar than of any other possession I have, for even you cannot take it away from me. I love you with all the manhood there is in me, and I can't remember a time when I did not; and I have thought that I knew, all these years, that you loved me; I believe it now, even though the scorn in your eyes denies it. You may have convinced yourself that you do not, but you are working from a wrong hypothesis. I know why you have put me off, time and again, when I have besought you to name our wedding-day. It has been because you were not quite ready. Isn't that true, dear? You have not denied me because you did not love me; you have put me off only because you were not ready to become a wife. But you have loved me; I am sure of that. You have never said that you would not be my wife; and in fact you have often shown me that some day you would be; you have only declined to say when. I have come to you to-night, Patricia, to tell you that I will wait, on and on, counting only your own pleasure in the matter, until you are willing to appoint the time, if only you will say that you forgive me for the apparently despicable part I have played in the tragedy of this afternoon."

"That is a very pretty speech you have just made. It sounds well, and is quite characteristic," she replied to him, calmly. "I shall be as frank with you in my reply."

"Well?" he said, and waited. Her tone and manner startled him. There was a suggestion of finality in her attitude that was alarming. She continued, speaking almost gently:

"I have believed in your love for me, as sincerely as I have believed in my father's love for me; and I think now that you were more to me than I realized. But, Roderick, have you ever watched a woodman in the forest chopping down a tree? And have you ever seen that tree fall, when its natural prop was stolen away by the sharp edge of the axe? It may have taken that tree a hundred, or a thousand years to grow; but when it crashes down, it is gone forever. A little, puny man has gone into the forest with an axe upon his shoulder, and has ruthlessly attacked one of God's greatest creations, a gorgeously abundant tree. He had no thought of what he was doing, of what he was destroying. His only thought was of a purpose he had in view; and it was somehow necessary to destroy that tree in order to accomplish the purpose. The thing that nature created, which had required years to bring to perfection; the thing that God made beautiful was, in a few minutes, shorn of its splendor by this little, ruthless creature, who went into the forest with the axe on his shoulder. That is what you have done to whatever love I may have felt for you, Roderick Duncan. It lies prostrate now, and it has borne down with it, all the lesser verdure, all the little trees and bushes and vines that grew about it, and has left only a bare spot—and the wounded stump. You were the woodman with the axe."

"My God, Patricia!" he cried out, appalled by the agony of his loss. He understood, suddenly, that this proud young woman would have forgiven downright disloyalty more readily than such hurt to her pride.

She continued as if he had not spoken:

"My father informed me, this afternoon, as you are aware, of certain financial straits in which he has suddenly become involved. I know enough about the methods and habits of 'the street,' to realize how impossible it was for him to betray his condition to certain forces and powers that are exerted there, lest, despite what he could do, he should lose the great influence he now has over all the immense wealth of this country. While he was telling me about his condition, I naturally thought of you; and I wondered why he had not gone to you instantly; or, if you knew of the circumstance, I wondered the more, why you had not as instantly gone to him, and offered the assistance he needed. Then, little by little by little, the plot which you two had concocted together, was unveiled to me."

"But, Patricia, dear, won't you—?"

"Let me finish, please. I have not quite done so, as yet."

"Well, dear?"

"I have agreed to the terms that were adjusted between you and my father, respecting the loan of a certain sum of money by you to him. Of course, you may repudiate those terms if you please, and it is a matter of indifference to me whether you do so, or not. You may loan the money to my father without accepting me as the collateral for it; that also is a matter of indifference to me. But I wish to tell you, and I wish you thoroughly to understand, that, unless you carry out the terms of this compact precisely as it was agreed upon between you and my father, with the added stipulations which I have requested Mr. Melvin to draw for me, I will never under any circumstances be your wife, or receive you again. That, I think, concludes this interview. I shall be ready Monday morning, at ten o'clock, to fulfill my part of the agreement. You and Stephen Langdon may do as you please. And now, please, bid me good-night—I prefer to be alone."

Duncan started from his chair and took two steps toward her, where he paused. His face was pale, but his finely chiseled features were set in firm lines; and his tall, athletic figure, was drawn to its full height, as he replied, with slow emphasis:

"In that case, Patricia, we shall carry out the compact as agreed upon, and I shall conform to whatever stipulations you have made," he said. "Good-night."

He turned and went swiftly from the room. He seized his coat and hat before James, the footman, could assist him, and he went out at the front door, with more bitterness and more anger in his soul than he remembered ever to have felt before against any man or woman. But just now the bitterness and the anger were directed chiefly against himself.

For a moment, he stood on the bottom step at the entrance to the mansion, undecided as to which way he should go or what he should do. Then, he turned about and again rang the bell at Stephen Langdon's door; and the instant it was opened, he brushed savagely past the astonished James, and made his way to the library, unannounced. He pushed the door ajar noiselessly, without intending to do so, and halted on the threshold, amazed by what he saw there. He had not meant to intrude in that silent fashion upon the privacy and grief of the woman he loved, and as soon as he could master his emotions, he stepped quickly backward into the hall, re-closing the door as softly as he had opened it. Patricia had given way at last. She had thrown herself upon the couch, and with her face buried among the pillows, she was sobbing as if her heart would break. His first impulse, when he discovered her so, was to rush to her side, to take her in his arms, and to tell her over and over again of his love. But he knew instinctively that Patricia would bitterly resent such an effort on his part, that he would again offend her sense of pride if she should know that he had found her in tears.

Outside the door, when he had closed it, he hesitated for a time; finally he wrote rapidly on the back of one of his cards, as follows:

"There will be little time on Monday morning to inspect the papers you mentioned. I shall be glad if you will direct Mr. Melvin to submit them to me at my rooms, between five and six o'clock to-morrow afternoon.

R. D."

He gave this written message to James, instructing him not to deliver it until Miss Langdon summoned him to her, or she should leave the library. Then, he asked the footman:

"Do you happen to know where Mr. Langdon has gone, to-night, James?"

"To the opera, sir," replied the footman.

"Alone?"

"Quite so, sir, I believe."

Duncan walked the distance, which was considerable, from the Langdon mansion to the Opera House, where he went directly to Stephen Langdon's box, believing that he would find the banker to be it's solitary occupant, and there were reasons why he greatly desired a private conference with Patricia's father. He entered the box without announcement and came to a sudden pause when he discovered that the banker was not alone. Beside him, with her white arm resting upon the rail at the front of the box, was seated a young woman whom Duncan knew well; and she happened to be the one person in New York who came nearest to being on terms of intimacy with Patricia. For Miss Langdon was one who had never permitted herself to be intimate with anybody. Others might be intimate with her, as Beatrice Brunswick had been, but that close and personal relation which so often exists between two young women, and which is so beautiful in its character, was something Patricia Langdon had never permitted herself to know. She was not even aware that this was so. The condition arose from no lack of sympathy for others, and from no want of affection for her friends; it was a characteristic reserve of manner and method, inherited from her father, which had been cultivated by and through her association with him, all her life long.

While Roderick Duncan halted for an instant, to consider whether, or not, he should proceed with his original design, and while he still stood there, holding the curtains apart and appearing much as if he were a stealthy observer of the scene before him, the young woman turned her head and discovered him. She smiled brightly and uttered an exclamation of pleasure as she started to her feet and approached him with out-stretched hand. One could have seen that the pleasure she manifested, was very real. It was at once evident that she liked Duncan.

"How good of you to come, and how fortunate!" she said, when he took her hand and raised it to his lips, just as the banker turned about in his chair, and with a grim smile also made Duncan welcome.

"Hello," he said. "Glad you came! I have been wondering all the evening where you were. Had an idea you would show up somewhere. Sit down and keep still until this act is finished, for I don't want to lose it. After that, we'll chat a little. There are things I wish to discuss with you, Roderick."

Roderick Duncan was in a mood that was strange to him. It affected him to recklessness, though he could not have told why it was so, or in what form of recklessness he might indulge. The discovery he had made when he returned to the library and found Patricia in tears, was still having its effects upon him, for he did not understand the cause for those tears. He knew only that he had made her cry, that her abandonment of grief was due to his acts, and her father's. By a strange paradox, he pitied himself as deeply as he did the woman he loved. He felt that he had been forced into a second false position by so readily accepting the terms Patricia had insisted upon for their betrothal. She had told him plainly that if she ever became his wife at all, the fact could be accomplished only in the manner she dictated; that if he repudiated it, he would not even be received at her home. Impulsively, he had accepted her dictum, and now, at the end of his long and solitary walk to the opera-house, he realized that the change from frying-pan to fire was a simile true as to his present condition. Practically, the end so long sought had been attained. In effect, he and Patricia were betrothed—but such a betrothal! For the moment, he regretted his ready acquiescence to Patricia's terms. He believed that it would be better to lose her entirely than to take her under such conditions.

The meeting with Beatrice Brunswick and her sincere welcome warmed him, and he found a ready sympathy in her eyes and manner for his condition of mind. He wanted company and he wanted sympathy; chiefly, he had wished to discuss the present situation of affairs with old Steve; but now, since his arrival at the box, he decided that it would be a splendid opportunity to talk the matter over with Beatrice Brunswick. She had always shown him great consideration. He had regarded her as Patricia's dearest friend, and had ultimately placed her in that relationship to himself, for she was one of those rare young women whom men class as "good fellows." And Beatrice was as good as she was beautiful. Her merry laugh and quick wit always acted upon Duncan like a tonic. Just now, he was especially glad to find her there, and he showed it.

Beatrice Brunswick was unmistakably red-headed. Referring to her hair in cold-blooded terms, no other hue could have described it. It was like that old-fashioned kind of red copper, after it has been hammered into sheets, in the manner in which it was treated before less arduous methods were invented. It was remarkable hair, too—there was such a wealth of it! It had always impressed Duncan with the idea that each individual hair was in business for itself, refusing utterly to stay where it was put. A young woman's crowning glory, always, this happened to be particularly true in the case of Miss Brunswick, for, although her features and her figure and her graceful motions left nothing to be desired, it was her wonderful hair, emphasized by the saucy poise of her head, that became her crowning glory, indeed. Duncan took a seat near to her, so that she was between him and the banker; and presently Beatrice inclined her head toward him, and whispered:

"What's the matter, Roderick? You look like a banquet of the Skull and Bones, which my brother described to me once, when he was at Yale."

"I'll tell you about it later," was the response; and Duncan shut his jaws, and bent his attention grimly upon the stage.

"Why not now?" She asked.

"There isn't time; and besides—"

"Have you been quarreling with our Juno? Have you two been scrapping?" She whispered, smiling bewitchingly, and bending still nearer to him. Miss Brunswick was sometimes given to the milder uses of slang.

Duncan nodded, without replying in words. He kept his eyes directly toward the stage. But Miss Brunswick was insistent.

"Is Patricia on her high horse to-night?" she asked, with a light laugh.

Duncan replied to her with another nod, and a wry smile.

"She wants to look out about that high horse of hers, Roderick, or sometime it will hit the top rail and give her a fall that she won't get over for a while. What our beautiful Juno needs most is what I used to get oftenest when I was about three years old. Perhaps you can guess what it was; if you can't, I won't tell you."

"I expect you were a regular little devil then, weren't you?" he asked, endeavoring to assume a cheerfulness he was far from experiencing at that moment.

"I expect I was; and the strange part of it is that there are lots and lots of people who insist that I have never got over it. But I can read you like a book. You and Mr. Langdon and Patricia have been having no end of a row. He might just as well have told me that much when he came after me and insisted that I should accompany him to the opera to-night. He said that Patricia wouldn't, and he wanted me to take her place. I wish you would tell me all about it." Then, with a slight toss of her head, Beatrice added: "I suppose Patricia has refused you again?"

"No. She has accepted me, this time," was the blunt reply.