[Contents]

Chapter I.

In Old Manila.

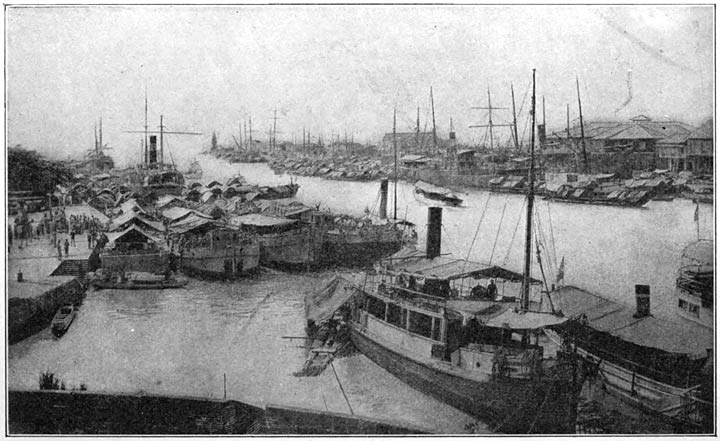

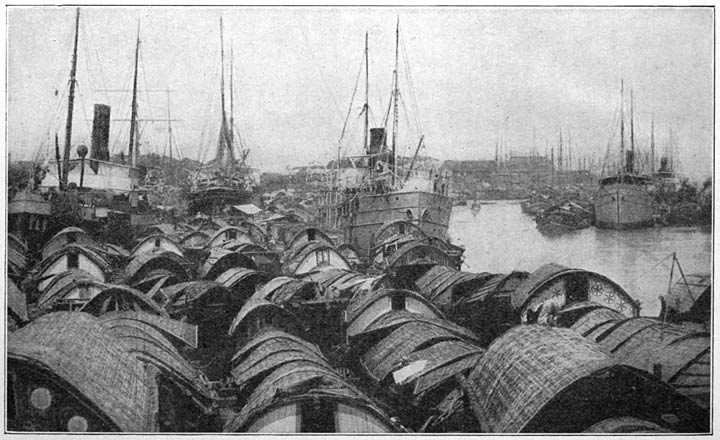

As the big white transport comes to anchor three miles out in the green waters of Manila Bay, a fleet of launches races out

to meet the messenger from the Far West. The customs officers in their blue uniforms, the medical inspectors, and the visitors

in white duck suits and panama hats, taking their ease upon the launches without the slightest sign of curiosity, give one

his first impressions of the Oriental life—the white man’s easy-going life in the Far East. But the ideas of the newcomer

are to undergo a change after his first few days on shore, when he takes up the grind, and realizes that his face is getting

pasty—that the cool veranda and the drive on the Luneta do not constitute the entire program, even in Manila.

Unwieldy lighters and strange-looking cascos now surround the transport, and the new arrival sees the Filipino for the first time. Under [10]the woven helmet of the nearest casco squats a shriveled woman, one of the witches from Macbeth, stirring a blackened pot of rice. A gamecock struggles at his

tether in the stern, while the deck amidships swarms with wiry brown men, with bristling pompadours and feet like rubber,

with wide-spreading toes. With unintelligible cries they crowd the gunwale, spurning the iron hull of the transport with long

billhooks, as the heavy swell sucks out the water, leaving the streaming sluices and the great red hull exposed, and threatening

at the inrush of the sea to bump the casco soundly against the solid iron plates of the larger ship. A most disreputable-looking crew it is, the ragged trousers rolled

up to the knee, the network shirts, or cotton blouses full of holes drawn down outside. Highly excitable, and yet good-natured

as they work, they take possession and disgorge the ship, while Chinamen descend the hatchways after dirty clothes.

Off in the hazy distance lies Cavite, or “the port,” with its white mist of war ships lying at anchor where the stout Dutch

galleons rode, in 1647, to attack the Spanish caravels, retiring only [11]after the Dutch admiral fell wounded mortally; where later, in the nineteenth century, the Spanish fleet put out to meet the

white armada, the grim battleships of Admiral Dewey’s line. Where now the lazy sailing vessels and the blackened tramps are

anchored, lay, in 1593, the hostile Chinese junks, with the barbaric eye daubed on the bows, the gunwales bristling with iron

cannon that had scorned the typhoons of the China Sea and gathered in Manila Bay.

This bay has been the scene of history-making since the sixteenth century. Soon after the flotilla of Legaspi landed the first

Spanish settlers on the crescent beach around Manila Bay, the little garrison was put to test by the invasion of the Chinese

pirate, Li Ma Hong. The memory of that brave defense in which the Spaniards routed the Mongolian invader, even the disaster

of that first of May can never drown. In 1582 the little fleet put out against the Japanese corsair, Taifusa, and returned

victorious. In 1610 the fleet of the Dutch pirates was destroyed off Mariveles. Those were stirring days when, but a few years

later, the armada of Don Juan de [12]Silva left Manila Bay again to test the mettle of the Dutch. Another naval encounter with the Dutch resulted in a victory

for Spanish arms in 1620 in San Bernardino Straits. And off Corregidor, whose blue peak marks the entrance to Manila Bay,

the Dutchmen were again defeated by the galleons of Don Geronimo de Silva. Now, near the Cavite shore, is seen the twisted

wreck of one of the ill-fated men of war that went down under the intolerable fire from Dewey’s broad-sides. And in 1899 the

Spanish transports left Manila Bay forever under the command of Don Diego de los Rios, with the remnant of the Spanish troops

aboard.

The city of Manila lies in a broad crescent, with its white walls and the domes of churches glowing in the sun. On landing

at the Anda monument, you find the gray walls and the moss-grown battlements of the old garrison—a winding driveway leading

across the swampy moat and disappearing through the mediæval city gate. This portion of Manila, laid out in the sixteenth

century by De Legaspi, occupies the territory on the south side of the Pasig River at the mouth. [13]The frowning walls of the Cuartel de Santiago loom above the bustling river opposite the customs-house.

Here, where the young American army officers look out expectantly for the arrival of the transport that is to bring them their

promotions, or to take them home, Geronimo de Silva was confined for not pursuing the Dutch vessels after the sea fight off

Corregidor. The crumbling walls still whisper of intrigue and secrecy. The fort was built in 1587, and became the base of

operations, not only against the pirate fleets of the Chinese, the Moros, and the Dutch, but also in the riots of the Chinese

and the Japanese that broke out frequently in the old days. At one time twenty thousand Chinamen were beaten back by an alliance

of the Spaniards, Japanese, and natives. On this historic ground the treaty was made in 1570 between the Spaniards and the

rajas of Manila, Soliman and Lacandola. The walls survived the fire of 1603. The earthquake causing the evacuation of Manila

could not shake them. Another prisoner of state, Corcuera, who had fought the Moros in the Jolo Archipelago, was [14]locked up in the Cuartel de Santiago at the instance of his Machiavellian successor. In 1642 the fort was strengthened by additional artillery because of an expected

visit from the Dutch. Today a soldier in a khaki uniform mounts guard at the street entrance. The courtyard is adorned by

pyramids of cannon-balls and tidy rows of bonga-trees. The soldiers’ quarters line the avenue on either side, and bugle-calls resound where formerly was heard the call of

the night watchman.

A number of elaborate but narrow passages—dim, gloomy archways, where the chain and windlass stand dust-covered from disuse—connect

the walled town with the extra-muros sections. The Puerto del Parian, on the Ermita side, is one of the most imposing of these gates. Near the botanical gardens on the boulevard, at the small

booth where Juliana sells cigars and bottled soda, following the turnpike over the moat, you come to the Parian gate, crowned

by the Spanish arms, in crumbling bas-relief. Beyond the drawbridge—lowered never to be raised again—where rumbling pony-carts

crowd the pedestrians to the wall, the passage opens into gloomy dungeons, with [15]barred windows looking out upon the stagnant waters of the moat. With an involuntary shudder, you pass on. A native policeman,

in an opera-bouffe uniform, stands at the further end in order to dispatch the vehicles that can not pass each other in the

narrow gate. Windowless, yellow walls, upon the corners of the streets, make reckless driving very dangerous, and collisions

frequently occur. A vacant sentry-box stands just within the city walls, and, turning here into the long street, you immediately

find yourself in an old Spanish town.

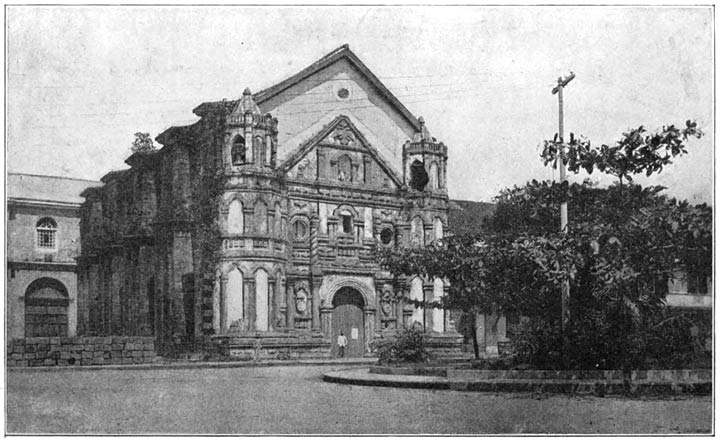

Here the grand churches and the public buildings are located; the cathedral, after the Romano-Byzantine style of architecture;

the Palacio, built after Spanish notions of magnificence, around a courtyard shaded by rare trees; and many other edifices, used for

official and ecclesiastic purposes. The streets are paved with cobblestone and laid out regularly in squares, in accordance

with the plan of De Legaspi, so that one side or the other will be always in the shade. Beautiful plazas, with their palms

and statues, frequently relieve the glare of the white walls. The sidewalks [16]are narrow, and are sheltered by projecting balconies.

The heavily-barred windows, ponderous doors, and quaint signboards give the streets an old-world aspect, while Calle Real is spanned by an arched gallery, like the Venetian Bridge of Sighs. Tailor-shops, laundries, restaurants, and barber-shops,

where swinging punkas waft the odor of bay rum through open doors, suggest a scene from some forgotten story-book or the stage-setting

for an Elizabethan play. In the commercial streets the absence of show-windows will be noticed. Bookstores display their wares

on stands outside, while of the contents of the other shops, one can obtain no adequate idea until he enters through the open

doors. The interesting signboards, whether they can be interpreted or not, tend to excite the curiosity. “Los Dos Hermanos” (The Two Brothers) is a tailor-shop, a Sastreria; and the shoestore a Zapateria. The family grocery-store, El Globo, is advertised by a huge globe, battered from long years of service; and La Lira, or the music-store, may be known by the sign of the gold lyre.

[17]

These streets have been the scene of many a drama in the past. Earthquakes in 1645, in 1863, and 1880, caused great loss of

life and property. The plague broke out in 1628, when Spaniards, Filipinos, and Chinese were swept off indiscriminately. Later,

epidemics of smallpox and cholera have made a prison and a pesthouse of Manila. Only in 1902 the city suffered from a run

of cholera, and the Americans, in spite of all precautions, could not stop the spread of the disease. The streets were flushed

at night; districts of native houses were put to the torch, and the detention-camp was full of suffering humanity. The natives,

in their ignorance, went through the streets in long processions, carrying the images of saints, chanting, and burning candles,

and at night would throw the bodies of the dead into the river or the canal. The ships lay wearily at quarantine out in the

bay, and the chorus of bells striking the hour at night was heard over the quiet waters. Officers patrolled the streets, inspected

drains and cesspools where the filth of ages had collected, giving the forgotten corners of Manila such a cleaning as they

never had received before.

[18]

But there were days of triumph and rejoicing—days such as had come to Greece and Rome; days when the level of life was raised

to heights of inspiration. Not only have the streets re-echoed to the martial music of the victorious Americans when Governor

Taft or the vice-governor were welcomed, but the town had rung with shouts of triumph when provincial troops had come back

from the conquest of barbarians, or when the fleets returned from victories over the Dutch and English and the Moro pirates

of the southern archipelago. And the streets reverberated to the sound of drum and trumpet when, in 1662, the special companies

of guards were organized to put down the rebellion of the Chinese in the suburbs. But in 1762 the town capitulated to the

English, and the occupation by Americans more than a century later, was a repetition of the scenes enacted then.

Because of the volcanic condition of the island, the houses can not be built more than two stories high. The ground floor

is of stone, and contains, besides the storehouse or a suite of living rooms, [19]the stables, arranged around a tiled courtyard, where the carriages are washed. A broad stairway conducts to the main corridor

above. The floor, of polished hardwood, is uncarpeted and scrupulously clean. Each morning the muchachos (house-boys) mop the floor with kerosene, skating around the room on rags tied to their feet, or pushing a piece of burlap

on all fours across the floor. The walls are frescoed pink and blue; the ceiling is often of painted canvas. The windows,

fitted with translucent shell in tiny squares, slide back and forth, so that the balcony can be thrown open to the light.

Double walls, making an alcove on one side, keep out the heat of the ascending or descending sun. The balcony at evening is

a favorite resort, and visitors are entertained in open air. In the interior arrangement of the houses, little originality

is shown, the Spaniards having insisted upon merely formal principles of art. The stiff arrangement of the chairs, facing

each other in precise rows, as if a conclave were about to be held, does not invite conviviality. There are few pictures on

the walls,—a faded [20]chromo, possibly, in a gilt frame, representing some old-fashioned prospect of Madrid, or the tinted portrait of the royal

family.

The Spanish residents and the mestizos entertain with great politeness and formality. Five o’clock is the fashionable hour for visiting, as earlier in the afternoon

the family is liable to be in négligée. The Spanish women, in loose, morning gowns, or blouses, and in flapping slippers, present a rather slovenly appearance during

morning hours; also the children, in their “union” suits, split tip the back, impress the stranger as untidy. During the noon

siesta everybody goes to sleep, to come to life late in the afternoon. At eight o’clock the chandelier is lighted and the evening

meal is served. This is a very formal dinner, consisting of innumerable courses of the same thing cooked in different styles.

A glass of tinto wine, a glass of water, and a toothpick whittled by the loving hands of the muchacho, finishes the meal. The kitchen is located in the rear, and generally overlooks the court, and near by are the bathroom and

the laundry.

In the walled city small hotels are numerous, [21]their entryways well banked with potted palms. The usual stone courtyard, damp with water, is surrounded by the pony-stalls,

where dirty stable-boys go through their work mechanically, smoking cigarettes. The dining-room and office occupy most of

the second floor. This is the library, reception-room, and ladies’ parlor, all in one; the guest-rooms open into this apartment.

These are very small, containing a big Spanish tester-bed, with a cane bottom, and the other necessary furniture. The sliding

windows open out into the street or the attractive courtyard, and the room reminds you somewhat of an opera-box. My own room

looked out at the hospital of San José, where a big clock, rather weatherbeaten, tolled the hours.

Manila to-day, however, is a contradiction. Striking anachronisms occur from the confusion of Malayan, Asiatic, European,

and American traditions. Heavy escort-wagons, drawn by towering army mules, crowd to the wall the fragile quilez and the carromata( two-wheeled gigs), with their tough native ponies. Tall East Indians, in their red turbans; Armenian merchants, soldiers

in khaki uniforms, and Chinese coolies [22]bending under heavy loads, jostle each other under the projecting balconies, while Filipinos shuffle peacefully along the

curb.

The new American saloons look rather out of place in such a curious environment, and telegraph wires concentrated at the city

wall seem even more incongruous.

[23]

[Contents]

Chapter II.

All About the Town.

The wide streets radiating from the Bridge of Spain are lined with lemonade stands, where the cube of ice is sheltered from

the sun by striped awnings. Leaving the walled town on the river side—the gate has been destroyed by earthquakes—you can take

the ferry over to the Tondo side. The ferryboat is a round-bottomed, wobbly sampan, with a tiny cabin in the stern. You crouch

down, waiting for the boat to roll completely over, which at first it seems inclined to do, or try to plan some method of

escape in case the pilot gets in front of one of the swift-moving tugs. You have good reason to congratulate yourself on being

landed at a stone-quay in a tangle of small launches, ferryboats, and cascoes. The Tondo Canal may be crossed on a covered barge, poled by an ancient boatman, who collects the fares—a copper cent of

Borneo, Straits Settlements, or [24]Hong Kong coinage—much in the same way as the pilot of the Styx collects the obolus.

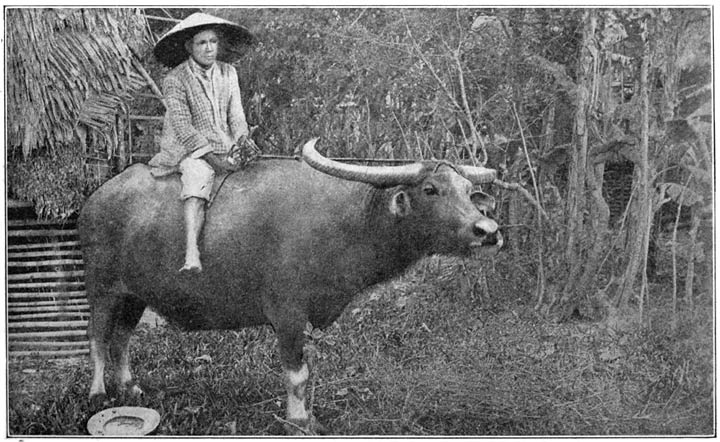

Under the long porch of the customs-house, a dummy engine noisily plies up and down among the long-horned carabaos and piles

of merchandise. Types of all nations are encountered here. The immigration office swarms with Chinamen herded together, rounded

up by some contractor. Every Chinaman must have his photograph, his number, and description in the immigration officer’s possession.

Indian merchants, agents of the German, Spanish, and English business firms are looking after new invoices. A party of American

tourists, just arrived from China, are awaiting the inspection of their baggage.

The Bridge of Spain, that famous artery of commerce, over which a stream of carabao-carts, crowded tram-cars, pleasure vehicles,

and army wagons flows continuously, spans the Pasig River at the head of the Escolta in Binondo. Here the bazaars and European

business houses are located, while the avenues that branch off lead to other populous and swarming districts. La Extrameña, a grocery and wine-store; La Estrella del Norte—[25]“The North Star”—diamond and jewelry-store; the Sombreria, hatstore, advertised by a huge wooden hat hung out above the street; and a tobacco booth, are situated on the corners where

the bridge and the Escolta meet. The Metropolitan policeman—one of the tall Americanos uniformed in khaki riding-breeches and stiff leggings—who, in former days, controlled the traffic of the street, is now supplanted

by a Filipino comic-opera policeman. Very few of the old “Mets” are left. It was a body of picked men, the finest soldiers

in the volunteer troops, and the most efficient police force in the world. This officer on the Escolta used to be a genius

in his line. When balky Filipino ponies blocked the traffic in the crowded thoroughfare, it was this officer that straightened

out the tangle. If the tram-car happened to run off the track, it was the “Met” who showed the driver how to put it on again.

The river above the bridge is lined with latticed balconies; but from the veranda of the Paris Restaurant, when that establishment

was in its glory, one could sit for hours and watch the bustling river life below. The thatched tops of the [26]huddled cascos formed a compact roof that extended half across the stream. Upon these nondescript craft hundreds of Filipinos dwelt, doing

their washing and their cooking on the decks. The scanty clothes are hanging out to dry on lines, while naked brats are splashing

in the dirty water, clinging to the tightened hawser.

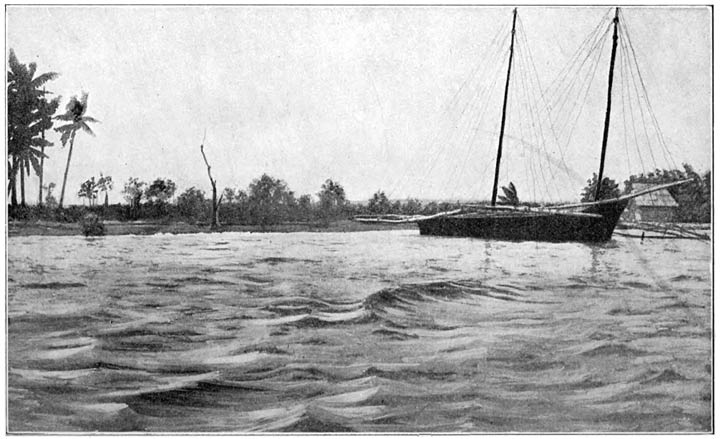

Launches go scudding under the low bridge, rending the air with vicious toots. Unwieldly cascos are poled down the river, laden heavily with cocoanuts and hemp. Small floating islands whirl along in the swift current,

and are carried out to sea. At the Muelle del Rey—the “King’s Dock”—lie the inter-island steamers, and the gangs of laborers are busy loading and unloading them. Carabao drays

are hauling fragrant cargoes of tobacco and Manila hemp, while over the gangplank runs a chain of men, gutting the warehouse

of its merchandise. The captain of the Romulus stands on the bridge, daintily smoking a cigarette, and supervising the disposal of the demijohns of tinto wine. The derrick keeps up an incessant racket as the hold is gradually filled. Although the Romulus is advertised to sail to-day at noon, she is [27]as liable to sail at ten o’clock, or possibly to-morrow afternoon; and although bound for Iloilo or Cebu, you can not be at

all sure what her destination really is. She may return after a month from a long rambling cruise among the southern isles.

The Spanish mariners, in rakish Tam o’Shanter caps, lounge at the entrance to the warehouse, or the office of the Compania Maritima, dreamily smoking cigarettes, sometimes imperiously ordering the laborers to “sigue, hombre!” (get along!) a warning that the Filipino has grown too familiar with to heed.

Armenian and Indian bazaars, where ivory and the rich fabrics of the Orient are sold; cafés and drugstores, harness-shops,

tobacco-shops, and drygoods-stores, emporiums of every kind,—are found on the Escolta, where the prices would astonish any

one not yet accustomed to the manners of the Far East. During the morning hours the quilez and the carromata rattle along the bumpy cobblestones, the native driver, or cochero, in a white shirt, smoking a cigarette, and resting his bare feet upon the dashboard. Behind the curtain of a passing quilez you can catch a glimpse of [28]brown eyes, raven hair, and olive-tinted cheeks, displayed with all the coquetry of a Manila belle. A Filipino family in a

rickety cart, tilted at an impossible angle, are drawn by a moth-eaten pony, mostly bones. Public conveyances—if these are

not indeed a myth—are most exasperating. You can never find one when you want it, even at the “Public Carriage Station.” If

by chance you come across one in the street, the driver will ignore your signal and drive on. Evidently he selects this walk

in life merely to discharge the obligations of his conscience, for he never seems to want a passenger, nor will he take one

till he finds his vehicle possessed by strategy. The gamins of the corner offer eagerly to find a carromata for you, but they frequently forget the object of their mission in their search. Sometimes, when you have ceased to think

about a carromata, one of these small ragamuffins will pursue you, with a sheepish-looking coachman and disreputable vehicle in tow. Then twenty

boys crowd round and claim rewards for having found a rig for you; as they all look alike, you toss a ten-cent piece among

the crowd and let them fight it out among themselves.

[29]

The driver will begin by making some objection. He will ask to be discharged at noon, or he will make you promise not to turn

him over to another Americano. When the preliminary arrangements are completed, lighting his cigarette, he cramps himself up in the box, and, maintaining

a continual clucking, larrups his skinny pony as the crazy gig goes rocking down the street. The driver never seems to know

the town; even the post-office and the Bridge of Spain are terra incognita to him. And so you guide him, saying “silla,” left, or “mano,” right, “direcho,” straight ahead, and “’spera,” stop. You must be careful when you stop, however, as while you are busy with your purchases, your man is liable to run

away. While, as a general rule, he shakes his head at the repeated inquires of “ocupato?” (taken?) even though the carriage may not be engaged, if some one more unscrupulous or desperate should step in, you would

find yourself without a rig. And the result would be the same if dinner-time came round, and he had not had “sow sow.” Even the fact that he had not collected any fare would not deter him from his resolution.

[30]

Is it any wonder, then, that, after all these difficulties, no complaint is made against the rickety, slat-seated carts, with

wheels that seem to bar the entrance of the passenger; against the sorry-looking quilez,—that attenuated two-wheeled ’bus, where the four passengers must sit with interwoven legs, getting the more implicated as

the cart goes bounding on? No; the Americans are glad enough to ride in almost any kind of vehicle. But you must be good-natured,

even though the cab is tilted at an angle of some thirty-odd degrees, and even though, in getting out, which is accomplished

from the quilez in the rear, you lift the tiny pony off his feet. It is enough to take the breath away to ride in one of these conveyances

through the congested portions of Manila. Not only does the turning to the left seem strange, but taking the sharp corners—an

accomplishment for which the two-wheeled gig is well adapted—frequently comes near precipitating a collision; and, in order

to avoid this, the driver pulls the pony to his haunches. When the coast is clear, you will go rattling merrily away, the

quilez door, unfastened, swinging back [31]and forth abandonedly, regardless of appearances. It is impossible to satisfy the driver on discharging him, unless by paying

him three times the fee. The stranger in Manila, counting out the unfamiliar media pesos and pesetas, never knows when he has paid enough. Whether to pay his fifteen cents, American or Mexican, for the first hour, and ten

cents, or centavos, for the hour succeeding, and how many media pesetas make a quarter of a dollar in our currency,—these are the questions that annoy and puzzle the newcomer, till he learns to

disregard expense, and order his livery from the hotels or private stables.

At noon the corrugated iron blinds of the shops are pulled down; all the carriages have disappeared; the only sign of life

in the Escolta is the comical little tram-car, loaded down with little brown men dressed in white, the driver tooting a toy

horn, and all the passengers dismounting to assist the car uphill.

The banking center of Manila, built around a dusty plaza in the Tondo district, and consisting of low buildings occupied by

offices of shipping and commercial companies, suggests a scene from [32]“The Merchant of Venice” or “Othello.” English firms—such as Warner, Barnes & Co.; Smith, Bell & Co.; the Hong Kong-Shanghai

Banking Corporation, where the silver pesos jingle as the deft clerks stack them up or handle them with their small spades—are situated hereabouts.

Near by, and on an emerald plaza, stand the buildings of the Insular Tobacco Company and of the Oriente Hotel. These buildings

are the finest modern structures in Manila. Carriages are waiting in the street in front of the hotel, and at the entrance

may be seen a group of army officers in khaki uniform, in white and gold, or—very much more modern—olive drab. The dining-room

is entered through the rustling bead-work curtain. Here the Chinese waiters, in long gowns glide noiselessly around.

But the Rosario, where opium-saturated Chinamen sit tailor-fashion at the entrance to their little stalls—where narrow galleries

and alleys swarm with Chinese life—is one of the most interesting and complex: of all Manila’s thoroughfares. On one side

of the street the drygoods-shops are shaded from the sun by curtains in broad stripes [33]of blue and white. The dreamy merchant sits barelegged on the doorsill, and is not to be disturbed by the mere entrance of

a purchaser. The opposite side is lined with Chino hardware stores, and in each one of them the stock is just the same. These shops supply the stock of merchandise to the provincial

agents; for an intricate feudal system is maintained among the Chinese of the archipelago. The rich Manila merchants who have

seen their fellow-countrymen safe through from China, and have furnished goods on credit, reap the profits like so many Oriental

Shylocks.

At four o’clock the shopping begins again in the Escolta. Apparently the whole town has turned out for a ride. Since the Americans

have come, odd sights have been seen in Manila,—cavalry horses harnessed to pony vehicles, phaetons drawn by Filipino ponies,

and victorias, intended for a pair of native horses, hastily converted into surreys. Not only do the Spanish women come out

in their black mantillas, but the Filipino belles and the mestiza, girls, in their stiff dresses of josé and piña cloth. A carriage-load of painted cheeks and burnished pompadours of Japanese [34]frail sisterhood drives by upon its way to the Luneta. Army officers in white dress uniform, the wives and daughters of the

officers, bareheaded and in dainty gowns, stop off at Clark’s for lemonade, ice-cream, and candy. Soldiers and sailors strolling

along the street, or driving rickety native carts, enjoy themselves after the manner of their kind. A brace of well-kept ponies,

tugging like game fish, trot briskly away with jingling harness, with the coachman and the footman dressed in white, a foreign

consul lounging in the cushions of the neat victoria. A private carruaje, drawn by a sleek pony, hastens along, the tiny footman clinging on for dear life to the extension seat behind.

After the whirl on the Luneta, where the military band plays as the oddly-assorted carriages go circling round like fixtures

on a steam carousal, the pleasure-seekers leave the driveway on the sea deserted; soldiers and citizens vacate the green benches,

and adjourn for dinner. The Spanish life is best seen at the Metropole, where señors, señoritas, and señoras, exquisitely gowned, sip cognac and coffee at the little tables, carrying on [35]an animated conversation, with expressive flashes of bright eyes or gestures with elaborately-jeweled hands.

Below, in the Luzon café, the Rizal orchestra is playing the impassioned Spanish waltzes, “Sobre las Olas,” “La Paloma,” to the click of billiard balls and the guffaws of soldiers. When the evening program ends with “Dixie,” every soldier in a khaki uniform—bronzed, grizzled fellows, many of them back from some campaign out in the provinces—will

rise immediately to his feet, respectfully remove his hat, and as the music that reminds him of the home-land swells and gathers

volume, fill the corridors with cheer upon cheer as the lights are put out; then the sleeping coachman rouses himself, and

starts the reluctant pony on the journey home.

[36]

[Contents]

Chapter III.

The White Man’s Life.

It happened that my first home in Manila was a temporary one, shared with a hundred others, at the nipa barracks at the Exposition grounds. Who of all those that were similarly situated will forget the long row of mimosa-trees

that made a leafy archway over the cool street; or the fruit merchants squatting beside the bunches of bananas and the tiny

oranges spread out upon the ground? There was the pink pavilion where that enterprising Chinaman, Ah Gong, conducted his indifferent

restaurant. After these many days I can still hear the clatter of the plates, the jingle of the knives and forks, placed on

the tables by the Chinese waiters. There was the crowd on the veranda waiting for the second table, opening their correspondence

as they waited. And what an indescribable sensation was imparted on receiving the first letter in a foreign land!

The long, cool barrack-rooms were swept by [37]the fresh breezes. Here, in the bungalow, the army cots had been arranged in rows and covered by mosquito-bars suspended from

the wires stretched overhead. When tucked inside of the mosquito-bar, one felt as though he were a part of a menagerie. “Muchacho” was the first new word you learned. It was advisable to call for a muchacho often, even though you did not need his services, in order to exploit your own experience and your superiority. And here

you were first cheated by the wily Chinese peddlers—although you had cut them down to half their price—when they unrolled

their packs of crêpe pajamas, net-work underwear, and other merchandise.

And all one Sunday afternoon you listened to a lecture from the President of the Manila Board of Health, who told of the diseases

that the flesh was heir to in the Philippines, and cheerfully assured you that within a month or two your weight would be

reduced to the extent of twenty-five or fifty pounds. And after dinner—where you learned that chiquos though they looked a good deal like potatoes, were a kind of fruit—while you were strolling down the avenue beyond the markethouse,

[38]you got a ducking from a sudden shower that ceased quite as unceremoniously as it had begun. There was excitement in the bungalow

that night because of its invasion by a hostile monkey. An impromptu vigilance committee finally succeeded in ejecting the

unwelcome visitor, persuading him of the superior advantages of “Barracks B.”

Together with a few dissenters, I moved out next morning, finding better quarters in the first floor of a Spanish house in

Magallanes. We made the best of an old ruin opposite, which we considered picturesque, and which was occupied by Filipino

squatters, who conducted a hand laundry there. Our first muchacho, Valentine, surprised us by existing on the ten-cent dinners of the Chinese chophouse on the corner. But he assured us that

it was a good place; that the greasy Chinaman, who fried the sausages and boiled the rice back in the tiny den, was a great

favorite. At our own restaurant, two Negro women made the best corn-fritters we had ever tasted; a green parrot and a monkey

squawked and chattered on the balustrade; a Filipino boy played marches on a cracked piano-forte.

[39]

And so we lived behind the heavily-barred windows, watching the shifting throng—the staggering coolies, girls with trays of

oranges upon their heads, and men in curiously fashioned hats—driving around the city in the afternoon (for Valentine was

at his best in getting carromatas under false pretenses) till the little family broke up. The first to go returned after a day or two, almost in tears with

the alarming information that the mayor of the town that he had been assigned to was a naked savage; that what he supposed

was pepper on the fried eggs he had had for breakfast, had turned out to be black ants—and wouldn’t we please pay his carromata fare, because he was completely out of funds?

The carabao carts gradually removed our baggage. Valentine was faithful to the last. Most of us met each other later, and

exchanged notes. One had escaped the target practice of ladrones; one had been lost among the mountains of Benguet; another

had been carried to Manila on a coasting steamer, reaching the Civil hospital in time to fight against the fevers that had

wasted him; and poor Fitz died of cholera in one of the most lonely villages among the Negros hills.

[40]

“Won’t those infernal bells stop ringing for a while and let a fellow go to sleep?” said Howard as he got out of bed. “Look

at those creatures, will you?” pointing to the fat mosquitoes at the top of the mosquito-bar. “The vampires! How do you suppose

they got in, anyway?”

“It beats me,” said the Duke. “It isn’t the mosquitoes or the bells: that ball of fire that’s shining through the window makes

a perfect oven of the room.”

The merciless sun had risen over the low roofs of the walled city, and the heat was radiating from the white walls and the

scorching streets. The Duke was sitting on the edge of the low army cot in his pajamas and his bedroom slippers, smoking a

native cigarette.

“It must be about ten o’clock,” said Howard. “I wonder if the Chinaman left any breakfast for us.”

“Probably. A couple of cold fried eggs, or a clammy dish of oatmeal and condensed milk. Shall we get up and go somewhere?”

“I can’t find any clothes,” said Howard; “this place is turning into a regular chaos, anyway.” [41]It was indeed a chaos,—lines of clothes where the mosquitoes swarmed, papers and books scattered about the floor, pajamas,

duck suits, towels on every chair, and muddy white shoes strewn around. “Doesn’t the muchacho ever clean things up?”

“That’s nothing,” said the Duke; “wait till the Chinaman runs off with all your washing. I can lend you a white suit; and,

say,—tell the muchacho to come in and blanco a few shoes.”

As there are no apartment-houses in Manila, the young clerk on small salary will usually live in a furnished room in the walled

city. For the first few months it is a rather dreary life. The cool veranda and the steamer chair, after the day’s work, is

a luxury denied the young Americans within the city walls. The list of amusements that Manila offers is an unattractive one.

There is a baseball game between two companies of soldiers, or between the Government employees representing different departments.

There is the cock-fight out at Santa Ana, Sunday mornings and fiesta days; but this is mostly patronized by [42]natives, and is not especially agreeable to Americans. The Country club—reached after a long drive out Malate way, past the

Malate fort that bears the marks of Dewey’s shells, past the old church once occupied by soldiers, through the rice-pads where

the American troops first met the Insurrecto firing line—is little more than a mere gambling-house. It is now visited by those

whose former resorts in the walled city have been broken up by the constabulary.

The races of the Santa Mesa Jockey dub are held on Sunday afternoons. It is a rather dusty drive out to the track. A number

of noisy “road-houses” along the way, where drinking is going on; the Paco cemetery, where the bleached bones have been piled

around the cross,—these are the sole diversions that the road affords. The races are interesting only in the opportunity they

offer to observe the native types. Here you will find the Filipino dandy in his polished boots, his low-crowned derby hat,

and baggy trousers. He makes the boast that he has not walked fifty meters on Manila’s streets in the past year. This dainty

little fellow always travels in a carriage. [43]He flicks the ashes off his cigarette with his long finger-nail as he stands by while the gay-colored jockeys are being weighed

in. Up in the grandstand, in a private box, a party of mestiza girls, elaborately gowned, are sipping lemonade, or eating sherbet and vanilla cakes, while one of the jockeys leans admiringly

upon the rail. The silver pesos stacked up on the table in the center of the box are given to a man in waiting to be wagered on the various events. The finishes

are seldom very close, the Filipino ponies scampering around the turf like rats. A native band, however, adds to the excitement

which the clamor at the booking office and the animated chatter of dueñas, caballeros, jockeys, and señoritas in the galleries intensifies.

Manila, the City of churches, celebrates its Sabbath in its own peculiar way. The Protestant churches suffer in comparison

with the grand church of San Sebastian—set up from the iron plates made in Belgium—and the churches of the various religious

orders. Magnificence and show appeal most strongly to the Filipino. He is taught to look down on the Protestant religion as

[44]plebeian; the priests regard the Protestant with condescending superciliousness. Until the transportation facilities can be

extended there will be no general coming together of Americans even on Sunday morning, as the colony from the United States

is scattered far and wide throughout the city.

As his salary increases, the young Government employee looks around for better quarters. These he secures by organizing a

small club and renting the upper floor of one of the large Spanish houses. As the young men in Manila are especially congenial,

there is little difficulty in conducting such an enterprise. The members of a lodging club thus formed will generally reserve

a table for their use at one of the adjacent boarding-houses or hotels.

The fashionable world—the heads of departments, general army officers, and wealthy merchants—occupy grand residences in Ermita

or in San Miguel. These houses, set back in extensive gardens, are approached by driveways banked luxuriously with palms.

A massive iron fence, mounted on stone posts, gives to the residence a [45]certain tone of dignity as well as a suggestion of exclusiveness. Those situated in Calle Real (Ermita) have verandas, balconies, and summer-houses looking out upon the sea.

The prosperous bachelor has his stable, stable-boys, and Chinese cook. At eight o’clock A. M. the China ponies will be harnessed

ready to drive him to the office, and at four o’clock the carriage calls for him to take him home. Most of the Americans thus

situated seldom leave their homes. There is, of course, the Army and Navy club in the walled city, and the University club

in Ermita; but aside from an occasional visit to these organizations, he is satisfied with a short turn on the Luneta and

the privacy of his own house.

The afternoon teas at the University club, where you can see the sunset lighting up Corregidor and glorifying the white battleships,

the monthly entertainments at the Oriente, and the governor’s reception, are the social features of Manila life. The ladies

do considerable entertaining, wearing themselves out in the performance of their social duties. As a relaxation, an informal

picnic party will sometimes charter a [46]small launch, and spend the day along the picturesque banks of the Pasig. The customs of Manila make an obligation of a frequent

visit to the Civil hospital, if it so happen that a friend is sick there. It is a long ride along Calle Iris, with its rows of bamboo-trees, past the merry-go-round, Bilibid prison, and the railway station; but the patients at the

hospital appreciate these visits quite sufficiently to compensate for any inconveniences that may have been caused.

During the holiday season, certain attractions are offered at the theaters. While these are mostly given by cheap vaudeville

companies that have drifted over from Australia or the China coast, when any deserving entertainment is announced the “upper

ten” turn out en masse. During the memorable engagement of the Twenty-fourth Infantry minstrels, the boxes at the Zorilla theater were filled by

all the pride and beauty of Manila. Captains and lieutenants from Fort Santiago and Camp Wallace, naval officers from the

Cavite colony, matrons and maidens from the civil and the military “sets,” made a vivacious audience, while the Filipinos

packed in the surrounding [47]galleries, applauded with enthusiasm as the cake-walk and the Negro melody were introduced into the Orient.

Where money circulates so freely and is spent so recklessly as in Manila, where the “East of Suez” moral standard is established,

the young fellows who have come out to the Far East, inspired by Kipling’s poems and the spirit of the Orient, are tempted

constantly to live beyond their means. It is a country “where there ain’t no Ten Commandments, and a man can raise a thirst.”

Then the Sampoluc and Quiapo districts, where the carriage-lamps are weaving back and forth among pavilions softly lighted,

where the tinkle of the samosen is heard, and where O Taki San, immodest but bewitching, stands behind the beadwork curtain, her kimono parted at the knee,—this

is the world of the Far East, the cup of Circe.

There was the pathetic case of the young man who “went to pieces” in Manila recently. He was a Harvard athlete, but was physically

unsound. As a result of an unfortunate blow received upon the head a short time after his arrival in Manila, he became despondent

and morose. After undue [48]excitement he would fall into a dreamy trance. At such times he would fancy that his mother had died, and he would be convulsed

with sorrow, breaking unexpectedly into a rousing college song. He meditated suicide, and was prevented several times from

taking his own life. On coming to Manila from the provinces, he stoutly refused to be sent home, but lived at his friends’

expense, trying to borrow money from everybody that he met. Other young fellows overwhelmed by debts have tried to break loose

from the Islands, but have been brought back from Japanese ports to be placed in Bilibid. That is the saddest life of all—in

Bilibid. Many a convict in that prison, far away, has been a gentleman, and there are mothers in America who wonder why their

boys do not come home.

Somebody once said that Manila life was a perpetual farewell. The days of the arrival and departure of the transports are

the days that vary the monotony. As the procession of big mail-wagons rumbles down the Escolta to the post-office, as the

letters from America are opened, as the last month’s newspapers and magazines [49]appear in the shop-windows, comes a moment of regret and lonesomeness. But as the transport, with its tawny load of soldiers

and of joyful officers, pulls out, the dweller in Manila, long ago resigned to fate, takes up the grind again.

Sometimes, on Sunday morning, he will take the customs-house launch out to one of the Manila-Hong Kong boats, to see a friend

off for the homeland and “God’s country.” Leaning over the taffrail, while the crowd below is celebrating the departure by

the opening of bottles, he will fancy that he, too, is going—till the warning whistle sounds, and it is time to go ashore.

The best view of Manila, it is said, is that obtained from the stern deck of an outgoing steamer, as the red lighthouse and

the pier fade gradually away. But even after he has reached the “white man’s country” some time he may “hear the East a-calling,”

and come back again.

[50]

[Contents]

Chapter IV.

Around the Provinces.

A half century before the founding of Manila, Magellan had set up the cross upon a small hill on the site of Butuan, on the

north coast of Mindanao, celebrating the first mass in the new land, and taking possession of the island in the name of Spain. Three centuries have

passed since then, and there are still tribes on that island who have never yielded to the influence of Christianity nor recognized

the authority of Spain or the United States. Magellan’s flotilla sailing north touched at Cebu, where the explorers made a

treaty with King Hamabar. The king invited them to attend a banquet, where, on seeing that his visitors were off their guard,

he slew a number of them mercilessly, while the rest escaped. On the same spot three hundred and fifty-odd years later, three

American schoolteachers were as treacherously slain by the descendants of this Malay king.

[51]

Not till the expedition of Legaspi and the Augustine monks visited the shores of the Visayan islands were the natives subjugated, and the finding of the Santo Niño (Holy Child) brought this about. Since then the monks and friars, playing on the superstition of the islanders, have managed

to control them and to mold them to their purposes. In 1568 a permanent establishment was made at Cebu by the bestowal of

munitions, troops, and arms, brought by the galleons of Don Juan de Salcedo. The conquest of the northern provinces began

soon after the flotilla of Legaspi came to anchor in Manila Bay.

The idea that Manila or the island of Luzon comprises most of our possessions in the East is one that I have found quite prevalent

throughout America. The broken blue line of the coast of Luzon reaches away in a dim contour to the northward for two hundred

miles, until the chain of the Zambales Mountains breaks into the flying, wave-lashed islands standing out against the trackless

sea. Southern Luzon, the country of Batangas, and the Camarines, extends a hundred miles south of Manila Bay.

[52]

In the far north are the rich provinces of Cagayan, Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur, Abra, Benguet, and Nueva Viscaya. The land

at the sea level produces hemp, tobacco, rice, and cocoanuts; the heavily-timbered mountain slopes contain rich woods, cedar,

mahogany, molave, ebony, and ipil. A wonderful river rushes through the mountain cañons, and the famous valley of the Cagayan

is formed—the garden of Eden of the Philippines. The peaks of the Zambales are so high that frost will sometimes gather at

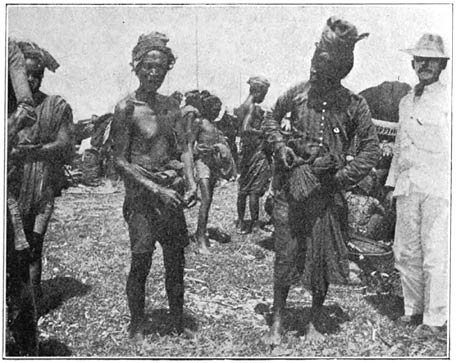

the tops, while in the upper forests even the flora of the temperate zone is reproduced. Negritos, the primeval savages, run

wild in the great wilderness, while cannibals, head-hunters, and other barbaric peoples live but a short distance from the

shore.

The islands to the south of Luzon reach in a long chain toward Borneo, a distance of six hundred miles. During a journey to

the southern islands a continuous procession of majestic mountains moves by like a panorama—first the misty peaks of the Mindoro

coast; and then the wooded group of islands in the Romblon Archipelago, that [53]rises abruptly out of the blue sea. Hundreds of smaller islands, like bouquets, dot the waters off Panay, while the bare ridges

of Cebu of the Plutonic peaks of Negros loom up far beyond. Passing the triple range of Mindanao, the scattered islands of

the Jolo Archipelago, the Tapul and the Tawi-Tawi groups mark the extreme southern limits of the Philippines.

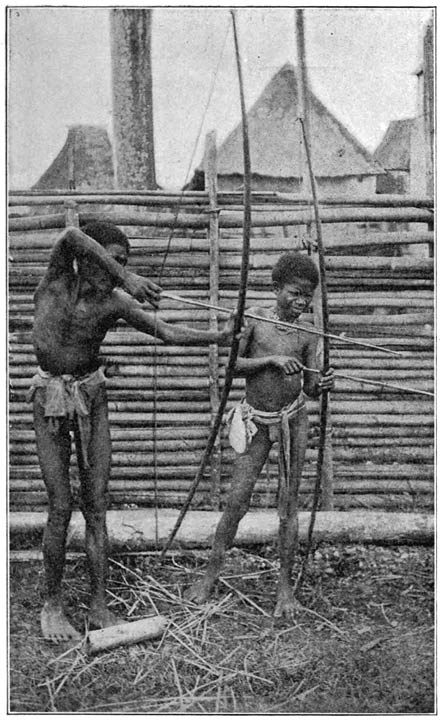

In nearly all these islands the interior is taken up by various tribes of savages, sixty or seventy different tribes in all,

speaking as many different dialects. There are the Igorrotes of the north, who make it their religion, when the fire-tree

blooms, to go out on a still hunt after human heads. When one of their tribe dies, the number of fingers that he holds up

as he breathes his last expresses the number of heads which his survivors must secure. An Igorrote suitor, too, must pay the

price, if he would have his bride, in human heads. The head of his best friend or of his deadliest enemy is equally acceptable;

and if his own pate fall in the attempt, he would not be alone among those who have “lost their heads” because of a fair woman.

[54]

Although the island of Luzon was settled later than the southern islands, civilization has been more widely disseminated in

the north. A railway line connects Manila with Dagupan and the other cities of the distant provinces. Aparri, on the Rio Grande,

near its mouth, is the commercial port of Cagayan. The country around is rich in live stock, and is partly under cultivation.

During the rainy season, however, the pontoon bridges over the Rio Grande are swept away; the roads become impassable. The

raging torrent of the river threatens the inland navigation, while the monsoons on the China Sea make transportation very

difficult.

The provinces of North and South Ilocos bristle with dense forests, where not only savages, but deer, wild hogs, and jungle-fowl

abound, and where the white man’s foot has never been. The natives bring the forest products, pitch, rattan, and the wild

honey, to the coast towns, where they can exchange their goods for rice. While in the mountainous regions of the northern

part, barbarians too timid to approach the coast are found, most of the pagan natives are of a mixed [55]type. The primitive Negritos, living in these parts, as those also living on the island of Negros and in Mindanao, are of

unknown origin—unless they are allied with similar types of pigmies, such as the Sakais of the Malay Peninsula, or the Mincopies

of the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean. Some anthropologists would even associate them with the black dwarfs in the interior

of Africa. These savages live a nomadic life, and seldom come down near the villages. But the mixed tribes, the Negrito-Malay,

or the Malay-Japanese, are bolder and more enterprising. The presence of the Japanese and Chinese pirates in this country

in the early days has been the cause of many of the eccentric types whose origin, entirely independent from the origin of

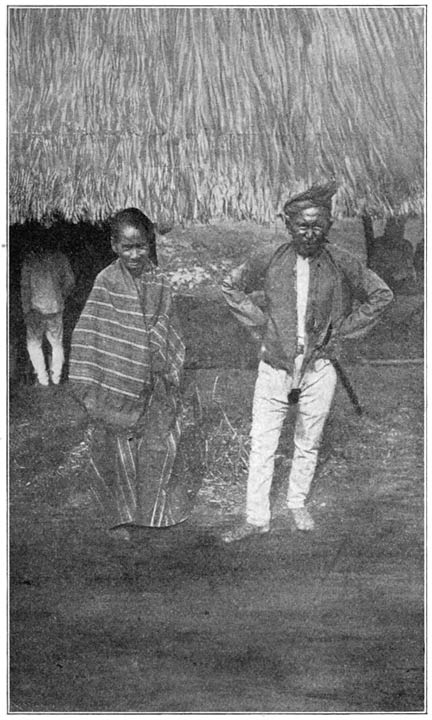

the Negritos, was Malayan. Here the Ilocanes, or the natives of the better class, the Christians of these provinces, although

of Malay origin, belong to a more cultured class of Malay ancestry. They are amenable to Christian influences, and their manners

are agreeable and pleasing. They cultivate abundant quantities of sugar, cotton, indigo, rice, and tobacco, and the women

weave the famous Ilocano [56]blankets that are sold at such a premium in Manila. Vigan, the capital of South Ilocos, has the finest public buildings and

the best-kept streets of any of the provincial cities.

Another tribe of people, the Zambales, are to be found toward the center of Luzon. Few Igorrotes, Ilocanes, and Negritos live

in the province of Zambales or Pangasinan. Pampanga Province also has its own tribe and a different dialect. Tagalog is spoken

around Manila, in Laguna Province, in Batangas, and the Camarines; Visayan is the language of the southern islands.

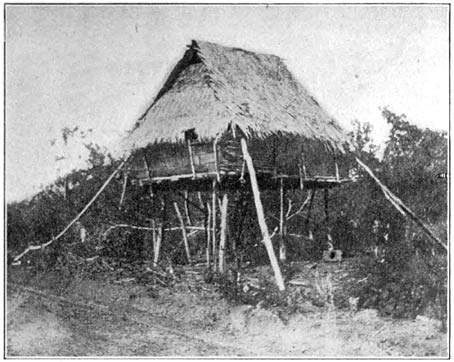

A monotonous sameness is the characteristic of most of the small Filipino towns. In seeing one you have seen all; you wonder

what good can come out of such a Nazareth, and there are very few of the provincial capitals, indeed, that merit a description.

Rambling official buildings, made of white concrete and roofed with nipa or with corrugated iron; a ragged plaza, with the church and convent, and the long streets lined with native houses; pigs

with heads like coal-scuttles; chickens and yellow dogs and naked brats, scabby and peanut-shaped,—such [57]are the first and last impressions of the Filipino town.

We reached Cebu during the rainy season, and it was a little city of muddy streets and tiled roofs. As the transport came

to anchor in the harbor, Filipino boys came out in long canoes, and dived for pennies till the last you saw of them was the

white soles of their bare feet. And in another boat two little girls were dancing, while the boys went through the manual

of arms. A number of tramp steamers, barkentines, and the big Hong Kong boat were lying in the harbor, while the coasting

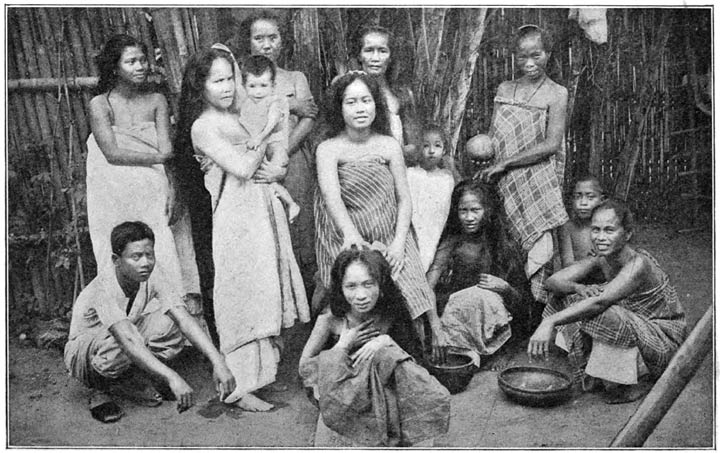

steamers of the Chinese merchants and the smaller hemp-boats lined the docks. As this was our first port in the Visayan group, the difference between the natives here and those of the Far North was very noticeable. There, the volcanic, wiry

Tagalog, or the athletic Igorrote savage; here, the easy-going, happy Visayan, carabao-like in his movements, with a large head, enormous mouth and feet.

Along the water front a line of low white buildings ran,—the wholesale houses of the English, Chinese, Spanish, and American

commercial firms. [58]The street was full of carabao carts, yoked to their uncomfortable cattle. Agents and merchants, dressed in white, were hurrying

to and fro with manifests. Around the corner was a long street blocked with merchandise, and shaded with the awnings of the

Chinese stores. There was a little barber-shop in a kiosko, where an idle native, crossing his legs and tilting back his chair, abandoned himself to the spirit of a big guitar. The

avenue that branched off here would be thronged with shoppers during the busy hours. Here were the retail stores of every

description—“The Nineteenth-century Bazaar,” the stock of which was every bit as modern as its name—clothing-stores, tailor-shops,

restaurants, jewelry-stores, and curio bazaars.

Numerous plazas were surrounded by old Spanish buildings and hotels. The public gardens—if the acre of dried palms and withered

grass may so be called—were situated near the water front, and had a band stand for the use of the musicians on fiesta days. The racetrack was adjacent to the gardens, and the public buildings faced these reservations. The magnificent old [59]churches, with their picturesque bell towers; the white convent walls, with niches for the statuettes of saints; the colleges

and convents,—give to the provincial capital an air of dignity.

The boarding-house, kept by a crusty but good-hearted Englishman, stood opposite the row of porches roofed with heavy tiles,

that made Calle Colon a colonnade. Across the street was a window in the wall, where the brown-eyed Lucretia used to sell ginger-ale and sarsaparilla

to the soldiers. With her waving pompadour, her olive cheeks, and sultry eyes, Lucretia was the belle of all the town. There

wasn’t a soldier in the whole command who wouldn’t have laid down his life for her. And in this land where nothing seemed

to be worth while, Lucretia, with her pretty manners and her gentle ways, had a good influence upon the tawny musketeers who

dropped in to play a game of dominos or drink a glass of soda with her; and she treated all of them alike.

A monkey chattered on the balcony, sliding up and down the bamboo-pole, or reaching for pieces of bananas which the boarders

passed him from the dinner-table. “Have you chowed yet?” asked [60]a grating voice, which, on a negative reply, ordered a place to be made ready for me at the table. Barefooted muchachos placed the thumb-marked dishes on the dirty table-cloth. I might add that a napkin had been spread to cover the spot where

the tomato catsup had been spilled, and that the chicken-soup, in which a slice of bread was soaked, slopped over the untidy

thumb that carried it. But I omitted this course, as the red ants floating on the surface of the broth rendered the dish a

questionable delicacy. The boarders had adjourned to the parlor, and were busy reading “Diamond Dick,” “Nick Carter,” and

the other five and ten cent favorites. A heavy rain had set in, as I drew my chair up to the light and tried to lose myself

in the adventures of the boy detective.

But the mosquitoes of Cebu! The rainy season had produced them by the wholesale, and full-blooded ones at that. These were

the strange bed-fellows that made misery that night, as they discovered openings in the mosquito-bar that, I believe, they

actually made themselves! The parlor (where the bed was situated) was a very interesting [61]room. There was a rickety walnut cabinet containing an assortment of cobwebby Venus’s fingers, which remind you of the mantel

that you fit over the gas jet; seashells that had been washed up, appropriately branded “Souvenir of Cebu;” tortoise-shell

curios from Nagasaki, and an album of pictures from Japan. The floor was polished every morning by the house-boys, and the

furniture arranged in the most formal manner, vis-á-vis.

The señorita Rosario, the sister-in-law of the proprietor, came in to entertain me presently, dressed in a bodice of blue piña, with the wide sleeves newly starched and ironed, and with her hair unbound. She sat down opposite me in a rocking-chair,

shook off her slippers on the floor, and curling her toes around the rung, rocked violently back and forth. She punctuated

her remarks by frequent clucks, which, I suppose, were meant to be coquettish. Her music-teacher was expected presently; so

while I wrote a letter on her escritorio, the señorita smoked a cigarette upon the balcony. The maestro came at last; a little, pock-marked fellow, dapper, and neatly [62]dressed, his fingers stained with nicotine from cigarettes. Together they took places at the small piano, and I could see

by their exchange of glances that the music-lesson was an incidental feature of the game. They sang together from a Spanish

opera the song of Pepin, the great braggadocio, of whom ’t is said, when he goes walking in the streets, “the girls assemble

just to see him pass.”

“Cuando me lanzo a calle

Con el futsaque y el cla,

Todas las niñas se asoman

Solo por ver me pasar:

Unas a otras se dicen

Que chico mas resa lao!

De la sal que va tirando

Voy a coher un punao.”

When the music-teacher had departed, the señorita leaned out of the balcony, watching the crowd of beggars in the street below. Of all the beggars of the Orient, those of

Cebu are the most clinging and persistent and repulsive. Covered with filthy rags and scabs, with emaciated bodies and pinched

faces, they are allowed to come into the city every week and beg for alms. Their whining, “Da mi dinero, señor, mucho pobre me” [63](“Give me some money, sir, for I am very poor”), sounds like a last wail from the lower world.

It was at Iloilo that we took a local excursion steamer across to the pueblo of Salai, in Negros. It was a holiday excursion, and the boat was packed with natives out for fun. There was a peddler with

a stock of lemon soda-water, sarsaparilla, sticks of boiled rice, cakes, and cigarettes. A game of monte was immediately started on the deck, the Filipinos squatting anxiously around the dealer, wagering their suca ducos (pennies) or their silver pieces on the turn of certain cards. It was a perfectly good-natured game, rendered absurd by the

concentric circles of bare feet surrounding it. There seemed to be a personality about those feet; there were the sleek extremities

of some more prosperous councilman or insurrecto general; there were the horny feet of the old women, slim and bony, or a pair of great toes quizzically turned in; and there

were flat feet, speckled, brown, or yellow, like a starfish cast up on the sand. They seemed to watch the game with interest,

and to note every move the dealer made, smiling or frowning as they won or lost. There [64]was a tramway at Salay, drawn by a bull, and driven by a fellow whose chief object seemed to be to linger with the señorita at the terminus. The town was hotter than the desert of Sahara, and as sandy; there was little prospect o£ relief save in

the distant mountains rising to the clouds in the blue distance.

Returning to our caravansary at Iloilo, we discovered that our beds had been assigned to others; there was nothing left to

do but take possession of the first unoccupied beds that we saw. One of our party evidently got into the “Spaniard’s” bed,

the customary resting-place of the proprietor, for presently we were awakened by the anxious cries of the muchachos, “Señor, señor, el Español viene!” (Sir, the Spaniard comes!) But he was not to be put out by any Spaniard, and expressed his sentiments by rolling over and

emitting a loud snore. The Spaniard, easily excited, on his entrance flew into an awful rage, while the usurper calmly snored,

and the muchachos peeked in through the door at peril of their lives.

Nothing especially of interest is to be found at Iloilo,—only a long avenue containing Spanish, [65]native, and Chinese stores; a tiny plaza, where the city band played and the people promenaded hand in hand; a harbor flecked with white, triangular sails of native

velas; and the river, where the coasting boats and tugs are lying at the docks. Neat cattle take the place of carabaos here to

a great extent. There is the usual stone fort that seems to belong to some scene of a comic opera. America was represented

here by a Young Men’s Christian Association, a clubhouse, and a presidente. The troops then stationed in the town added a certain tone of liveliness.

It was a week of carol-singing in the streets, of comedies performed by strolling bands of children, masses, and concerts

in the plaza. On Christmas afternoon we went out to the track to see the bicycle races, which at that time were a fad among the Filipinos.

The little band played in the grand-stand, and the people cheered the racers as they came laboriously around the turn. The

meet was engineered by some American, but, from a standpoint of close finishes, left much to be desired. The market-place

on Christmas eve was lighted by a thousand lanterns, and the little people [66]wandered among the booths, smoking their cigarettes and eating peanuts. Until early morning the incessant shuffling in the

streets kept up, for every one had gone to midnight mass. Throughout the town the strumming of guitars, the voices of children,

and the blare of the brass band was heard, and the next morning Jack-pudding danced on the corner to the infinite amusement

of the crowd. As for our own celebration, that was held in the back room of a local restaurant, the Christmas dinner consisting

of canned turkey and canned cranberry-sauce, canned vegetables, and ice-cream made of condensed milk.

[67]

[Contents]

Chapter V.

On Summer Seas.

The foolish little steamer Romulus never exactly knew when she was going, whither away, or where. The cargo being under hatches, all regardless of the advertised

time of departure, whether the passengers were notified or not, she would stand clumsily down stream and out to sea. The captain,

looking like a pirate in his Tam o’Shanter cap, or the pink little mate with the suggestion of a mustache on his upper lip,

if they had been informed about sailing hour, were never willing to divulge the secret. If you tried to argue the matter with

them or impress them with a sense of their responsibility; if you attempted to explain the obvious advantages of starting

within, say, twenty-four hours of the stated time, they would turn wearily away, irreprehensible, with a protesting gesture.

Not even excepting the Inland Sea, that dreamy waterway among the grottoes, pines, and [68]torii of picturesque Japan, there is no sea so beautiful as that around the Southern Philippines. The stately mountains, that go

sweeping by in changing shades of green or blue, appeal directly to the imagination. Unpopulated islands—islands of which

some curious myths are told of wild white races far in the interior; of spirits haunting mountain-side and vale; volcanoes,

in a lowering cloud of sulphurous smoke; narrows, and wave-lashed promontories, where the ships can not cross in the night;

great mounds of foliage that tower in silence hardly a stone’s throw from the ship, like some wild feature of a dream,—such

are the characteristics of the archipelago.

The grandeur of the scenery, the tempered winds, the sense of being alone in an untraveled wilderness, made up in part for

the discomforts of the Romulus. The tropical sunsets, staining the sky until the whole west was a riot of color, fiery red and gold; the false dawn, and

the sunrise breaking the ramparts of dissolving cloud; the moonlight on the waters, where the weird beams make a shimmering

path that leads away across the planet waste to terra incognita, or to [69]some dank sea-cave where the sirens sing,—this is a day and a night upon the summer seas.

At night, as the black prow goes pushing through the phosphorescent waters, porpoises of solid silver, puffing desperately,

tumble about the bows, or dive down underneath the rushing hull. The surging waves are billows of white fire. In the electric

moonlight the blue mountains, more mysterious than ever, stand out in bold relief. What restless tribes of savages are wandering

now through the trackless forests, sleeping in lofty trees, or in some scanty shelter amid the tangled underbrush! The light

that flickers in the distant gorge, perchance illumines some religious orgy—some impassioned dance of primitive and pagan

men. What spirits are abroad to-night, invoked at savage altars by the incantations of the savage priests—spirits of trees

and rivers emanating from the hidden shrines of an almighty one! Or it may be that the light comes from an isolated leper

settlement, where the unhappy mortals spend in loneliness their dreary lives.

On the first trip of the Romulus I was assigned to a small, mildewed, stuffy cabin, where [70]the unsubstantial, watery roaches played at hide-and-seek around the wash-stand and the floor. It was a splendid night to

sleep on deck; and so, protected from the stiff breeze by the flapping canvas, on an army cot which the muchacho had stretched out, I went to sleep, my thoughts instinctively running into verse:

“The wind was just as steady, and the vessel tumbled more,

But the waves were not as boist’rous as they were the day before.”

It was the rhythm of the sea, the good ship rising on the waves, the cats’-paws flying into gusts of spray before the driving

wind.

I was awakened at four bells by the disturbance of the sailors swabbing down the deck—an exhibition performance, as the general

condition of the ship led me to think. Breakfast was served down in the forward cabin, where, with deep-sea appetites, we

eagerly attacked a tiny cup of chocolate, very sweet and thick, a glass of coffee thinned with condensed milk, crackers, and

ladyfingers. That was all. Some of our fellow-passengers had been there early, as the dirty table-cloth [71]and dishes testified. A Filipino woman at the further end was engaged in dressing a baby, while the provincial treasurer,

in his pink pajamas, tried to shave before the dingy looking-glass. An Indian merchant, a Visayan belle with dirty finger-nails and ankles, and a Filipino justice of the peace still occupied the table. Reaching a vacant

place over the piles of rolled-up sleeping mats and camphorwood boxes—the inevitable baggage of the Filipino—I swept off the

crumbs upon the floor, and, after much persuasion, finally secured a glass of lukewarm coffee and some broken cakes. The heavy-eyed

muchacho, who, with such reluctance waited on the table, had the grimiest feet that I had ever seen.

A second meal was served at ten o’clock, for which the tables were spread on deck. The plates were stacked up like Chinese

pagodas, and counting them, you could determine accurately the number of courses on the bill of fare. There were about a dozen

courses of fresh meat and chicken—or the same thing cooked in different styles. Garlic and peppers were used liberally in

the cooking. Heaps of boiled rice, olives, and [72]sausage that defied the teeth, wrapped up in tinfoil, “took the taste out of your mouth.” Bananas, mangoes, cheese, and guava-jelly

constituted the dessert. After the last plate had been removed, the grizzled captain at the head of the table lighted a coarse

cigarette, which, in accordance with the Spanish custom, he then passed to the mate, so that the mate could light his cigarette.

This is a more polite way than to make an offer of a match. Coffee and cognac was brought on after a considerable interval.

Although this process was repeated course for course at eight o’clock, during the interim you found it was best to bribe the

steward and eat an extra meal of crackers.

Our next voyage in the Romulus was unpropitious from the start. We were detained five days in quarantine in Manila Bay. There was no breeze, and the hot

sun beat down upon the boat all day. To add to our discomforts, there was nothing much to eat. The stock of lady-fingers soon

became exhausted, and the stock of crackers, too, showed signs of running out. As an experiment I ordered eggs for breakfast

once—but only once. The cook had evidently tried [73]to serve them in disguise, believing that a large amount of cold grease would in some way modify their taste. He did not seem

to have the least respect for old age. It was the time of cholera; the boat might have become a pesthouse any moment. But

the steward assured us that the drinking water had been neither boiled nor filtered. There was no ice, and no more bottled

soda, the remaining bottles being spoken for by the ship’s officers. At the breakfast-table two calves and a pig, that had

been taken on for fresh meat, insisted upon eating from the plates. The sleepy-eyed muchacho was by this time grimier than ever. Even the passengers did not have any opportunity to take a bath. One glance at the ship’s

bathtub was sufficient.

It was a happy moment when we finally set out for the long rambling voyage to the southern isles. The captain went barefooted

as he paced the bridge. A stop at one place in the Camarines gave us a chance to go ashore and buy some bread and canned fruit

from the military commissary. How the captain and the mate scowled as we supplemented our elaborate meals with these purchases!

[74]One of the passengers, a miner, finally exasperated at the cabin-boy, made an attack upon the luckless fellow, when the steward,

who had been wanting an excuse to exploit his authority, came up the hatchway bristling. In his Spanish jargon he explained

that he considered it as his prerogative to punish and abuse the luckless boy, which he did very capably at times; that he

would tolerate no interference from the passengers. But the big miner only looked him over like a cock-of-the-walk regarding

a game bantam. Being a Californian, the miner told the steward in English (which that officer unfortunately did not understand)

that if the service did not presently improve, the steward and cabin-boy together would go overboard.

Stopping at Dumaguete, Oriental Negros, where we landed several teachers, with their trunks and furniture, upon the hot sands,

most of us went ashore in surf-boats, paddled by the kind of men that figure prominently in the school geographies. It was

a chapter from “Swiss Family Robinson,”—the white surf lashing the long yellow beach; the rakish palm-trees bristling in [75]the wind; a Stygian volcano rising above a slope of tropic foliage; the natives gathering around, all open-mouthed with curiosity.

At Camaguin, where the boat stopped at the sultry little city of Mambajo, an accident befell our miner. When we found him,

he was sleeping peacefully under a nipa shade, guarded by a municipal policeman, with the ring of Filipinos clustering around. He had been drinking native “bino” (wine), and it had been too much even for him, a discharged soldier and a Californian.

It was almost a pleasant change, the transfer to the tiny launch Victoria, that smelled of engine oil and Filipinos, and was commanded by my old friend Dumalagon. The Victoria at that time had a most unpleasant habit of lying to all night, and sailing with the early dawn. When I had found an area

of deck unoccupied by feet or Filipino babies, Chinamen or ants, I spread an army blanket out and went to sleep in spite of

the incessant drizzle which the rotten canopy seemed not to interrupt. I was awakened in the small hours by the rattle of

the winch. These little boats make more ado in getting under way than any ocean [76]steamer I have ever known. Becoming conscious of a cloud of opium-smoke escaping from the cockpit, which was occupied by several

Chinamen, I shifted to windward, stepping over the sprawling forms of sleepers till I found another place, the only objection

to which was the proximity of numerous brown feet and the hot engine-room. The squalling of an infant ushered in the rosy-fingered

dawn.

Most of the transportation of the southern islands is accomplished by such boats as the Victoria. I can remember well the nights spent on the launch Da-ling-ding, an impossible, absurd craft, that rolled from side to side in the most gentle sea. She would start out courageously to cross

the bay along the strip of Moro coast in Northern Mindanao; but the throbbing of her engines growing weaker and weaker, she

would presently turn back faint-hearted, unable to make headway, at the mercy of a sudden storm, and with the possibility

of being swept up on a hostile shore among bloodthirsty and unreasonable Moros. Another time, and we were caught in a typhoon

off the north coast. We thought, of course, [77]our little ship was stanch, until we asked the captain his opinion. “If the engines hold out,” he replied, “we may come through

all right. The engineer says that the old machine will probably blow up now any time, and that the Filipinos have quit working

and begun their prayers.” Generally a Filipino is the first to give up in a crisis; but I have seen some that managed their

canoes in a rough sea with as much skill and coolness as an expert yachtsman could have shown. I have to thank Madroño for

the way in which he handled the small boat that put out in a sea like glass and ran into a squall fifteen miles out. All through

the morning we had poled along over the crust of coral bottom, where, in the transparent water, indigo fishes swam, where

purple starfish sprawled among the coral—coral of many colors and in many forms. But as the wind came up and lashed the choppy

sea to whitecaps, as the huge waves swept along and seemed about to knock the little banca “off her feet,” Madroño, standing on the bamboo outrigger—a framework lashed together with the native cane, the breaking

of which would have immediately upset the boat—kept her bow [78]pointed for the shore, although a counter storm threatened to blow us out to the deep sea.

So, after knocking around in bancas, picnicking with natives on the chicken-bone and boiled rice; after a wild cruise in the Thomas, where the captain and the crew, as drunk as lords, let the old rotten vessel drift, while threatening with a gun the man

that dared to meddle with the steering gear; after a dreary six months in a provincial town,—it seemed like coming into a

new world to step aboard the clean white transport, with electric-lights and an upholstered smoking-room.

A tourist party, mostly army officers, their wives and daughters, “doing” the archipelago, made up the passenger list of the

transport. The officers, now they had settled satisfactorily the question of superiority and “rank,” made an agreeable company.

There was the Miss Bo Peep, in pink and white, who wore a dozen different military pins, and would not look at any one unless

he happened to be “in the service.” Like many of the army girls, she had no use for the civilians or volunteers. Her mamma

told with [79]pride how, at their last “at home,” nobody under the rank of a major had been present. One of the young lieutenants down at

Zamboanga, when he found she had not worn his pin, “retired to cry.” But then, of course, Bo Peep was not responsible for

young lieutenants’ hearts. If he had been a captain—well, that is another thing. There was the English sugar-planter from

the Tawi-Tawi group, who never lost sight of the ranking officer, who dressed in flannels, changed his clothes three times

a day, and who expressed his only ideas to me by virtue of a confidential wink.

For three whole days we were a part of the fresh winds, the tossing waves, the moon and stars. And as the ship plowed through

the sea at night, the phosphorescent surge retreated like a line of silver fire.

[80]

[Contents]

Chapter VI.

Among the Pagan Tribes.

With Padre Cipriano I had started out on horseback from the little trading station on Davao Bay. We were to strike along the

east coast, in the territory of the fierce Mandayas, and to penetrate some distance into the interior in order to convert