"HAVE OUR SHEEP ALWAYS BEEN DIPPED?"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Story of Wool, by Sara Ware Bassett This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Story of Wool Author: Sara Ware Bassett Illustrator: Elizabeth Otis Release Date: March 17, 2008 [EBook #24858] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF WOOL *** Produced by La Monte H.P. Yarroll and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

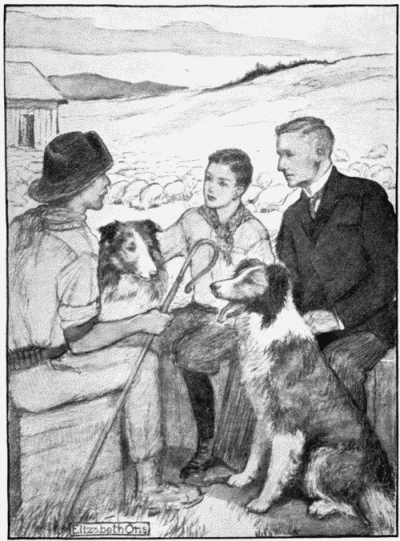

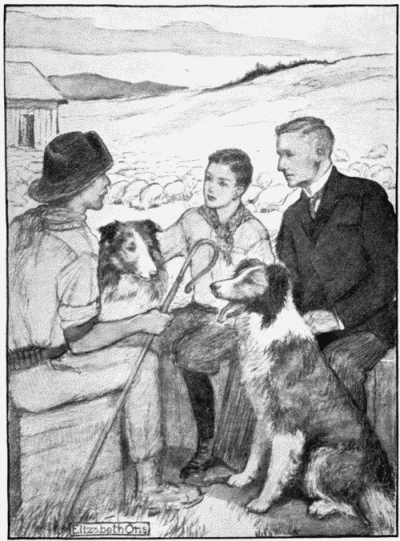

"HAVE OUR SHEEP ALWAYS BEEN DIPPED?"

BY

SARA WARE BASSETT

Author of "The Story of Lumber" and "The Story of Leather"

ILLUSTRATED BY

ELIZABETH OTIS

THE PENN PUBLISHING COMPANY PHILADELPHIA

COPYRIGHT

1913 BY

THE PENN

PUBLISHING

COMPANY

To

MY FATHER

It gives me pleasure to acknowledge the courtesy and coöperation of the United States Department of Agriculture.

S. W. B.

Donald Clark glanced up from his Latin grammar and watched his father as

he tore open the envelope of a telegram and ran his eye over its

contents. Evidently the message was puzzling. Again Mr. Clark read it.

Donald wondered what it could be. All the afternoon the yellow envelope

had been on the table, and more than once his mind had wandered from the

lessons he was preparing to speculate on the possible tidings wrapped [10]

up in that sealed packet. Not that a telegram was an unheard-of event in

the family. No, his father received many; most of them, however, went to

the Boston office, and the boy could not imagine what this one was doing

at their Cambridge home.

Donald Clark glanced up from his Latin grammar and watched his father as

he tore open the envelope of a telegram and ran his eye over its

contents. Evidently the message was puzzling. Again Mr. Clark read it.

Donald wondered what it could be. All the afternoon the yellow envelope

had been on the table, and more than once his mind had wandered from the

lessons he was preparing to speculate on the possible tidings wrapped [10]

up in that sealed packet. Not that a telegram was an unheard-of event in

the family. No, his father received many; most of them, however, went to

the Boston office, and the boy could not imagine what this one was doing

at their Cambridge home.

The moment his father entered the house Donald handed him the envelope and Mr. Clark quickly stripped it open; yet even though it now lay spread out before him the mystery it contained appeared to be unsolved. It was seldom that Donald asked questions, nevertheless he found himself wondering and wondering what it was that had brought that odd little wrinkle into his father's forehead. Donald understood that wrinkle; he had seen it many times and knew it never came unless some question arose to which it was difficult to frame an answer. As his father and he had lived alone together ever since he could remember they had grown to know each other very well, and had become the best of friends. It therefore followed that when one worried, both worried.

As the boy looked on, his father glanced up [11] suddenly and caught sight of the anxiety mirrored in his face. The man smiled kindly.

"I can find no answer to this riddle, Don," he said. "Listen! Perhaps you can help me. A few days ago I received word from Crescent Ranch that Johnson, our manager, had been thrown from his horse while out on the range and so badly hurt that he will never again be able to continue his work with us. They have taken him to the hospital at Glen City. The letter came from Tom Thornton, the head herder at the ranch. Thornton assured me that everything was going well, and that there was not the slightest need for me to come to Idaho."

Donald listened.

"Well, to-day I received this telegram. It is neither from Johnson nor Thornton. It reads:

"'You would do well to visit Crescent Ranch,' and it is signed—'Sandy McCulloch.'"

"Who is Sandy McCulloch?" asked Donald.

"That's the puzzle! I do not know. I never heard of any such person in my life—not that I remember. Evidently, though, he knows enough [12] about me to know that I own that sheep ranch, and to think that I ought to go out there and see it. I do not understand it at all. What do you make of it, son?"

Donald thought carefully.

"Do you suppose anything is wrong on the ranch?"

"No, indeed! Thornton wrote particularly that everything was all right. He was Johnson's assistant, and he ought to know. Besides, he has been with us a long time, and is thoroughly familiar with every part of the work."

"Maybe it's a joke," ventured Donald.

"It would be a stupid sort of joke to get me from Boston to Idaho on a wild-goose chase. No, there is no joke about this," went on Mr. Clark, rising and pacing the floor. "Sandy McCulloch is real, and he has some real reason for wanting me to go to Crescent Ranch. I think I shall take his advice and go."

Donald was astounded. His father never left home.

"And the office?" [13]

"Uncle Harold will have to do double duty while I am gone."

"And—and—I?" inquired the boy hesitatingly.

Idaho seemed very far away—quite at the other end of the world.

"You? Oh, you'll have to go along too! I shall need you."

Donald drew a long breath.

"Let me see," continued his father, "this is the end of March, isn't it? Your spring term is about over. I happen to know you are well up in your work, for I met Mr. Hurlbert, the high school principal, only yesterday. I am sure that if you fall behind by going on this trip you will study all the harder to make up the work when you get back, won't you?"

"Yes, sir!" was the emphatic promise.

"You see I've no idea how long I shall be detained out West, therefore I have no mind to leave you here. You might be ill. Besides, I should miss you, Don."

"I'd much rather go with you, father."

A quick light of pleasure flashed in the father's eyes. [14]

"Then that's settled," he exclaimed decisively. "Now I'll tell you what I mean to do. I am not going to wire Crescent Ranch that we are coming. Instead we will drop down and surprise them. It won't take long to see how things are running, and even if it proves that everything is all right I shall not begrudge the trip, for I have felt for some time that I ought to go. Clark & Sons have owned that ranch for thirty years, and yet I have never been near it. It certainly is time I went."

"How did it happen you never did go, father?"

"Well, during your grandfather's life an old Scotchman managed the ranch and attended to shipping the wool. As we had nothing to do but to sell it, we did not bother much about the place, for we had perfect confidence in Old Angus, the manager. After your grandfather died, Uncle Harold and I had all we could do to attend to the business here. It grew so rapidly that it was about as much as two young fellows like ourselves could handle. We always meant to go out—one [15] of us—but we never did. Then our faithful Scotchman died. We felt lost, I can tell you! He had had all the management of Crescent for twenty years and was one of the finest men in the world. He might have lived until now, perhaps, had he not been caught on the range in a blizzard while struggling to get a flock of sheep out of the storm and thereby lost his life."

Mr. Clark paused a moment.

"After him came Johnson. He has done his work well, so far as we know; but now he is out of the running too and we shall have to get some one else."

"Whom are you going to get?"

"I haven't the most remote idea. You see, Don, I know next to nothing about managing a ranch. I stay here in Boston and simply sell wool. This end of the business I know thoroughly, but the other end is Greek to me."

Donald laughed. He was just beginning Greek.

"I am glad you don't know about a ranch, father," he exclaimed.

"Why?" [16]

"Oh, because you seem to know almost everything else, and it is fun to find something you don't know."

There was admiration in the boy's words.

His father shook his head and there was a shadow of sadness in his smile as he replied:

"I know very little, Donald boy. The older I grow the less I know, too. You will feel that way when you are my age. Now here is a chance for us to learn something together. Let's go to Idaho and find out all we can about sheep-raising."

Within the next few days the plans for the journey were completed.

As one article after another was purchased and packed the trip unfolded into a most alluring pilgrimage. They must take their riding togs, for Uncle Harold reminded them that they would probably be in the saddle much of the time; their camping kit must go also; above all they must carry good revolvers and rifles. Donald's heart beat high. He and his father had always ridden a great deal together; it was their favorite sport. [17] Now they were to have whole days of it. And added to this pleasure was the crowning glory of both a rifle and a revolver!

All this fairy-land of the future had come about through Sandy McCulloch!

Who was this wonderful Sandy? And why had he telegraphed?

Sandy McCulloch! The very name breathed a charm. Donald repeated it to himself constantly. He dreamed dreams and wove adventures about this mysterious Scotchman. He knew he should like Sandy. Who could help it? His name was enough.

In the meantime the days of preparation flew by. Donald's spring examinations were passed with honors—a fact which his father declared proved that he had taken his work in earnest and that he deserved an outing. Mr. Clark laughingly ventured the hope that he should be able to leave his business affairs in equally good condition.

"You have set quite a pace for me, Don! I am not sure whether I can take honors at the office or not. I have done the best I could, however, [18] to put things into Uncle Harold's hands so to cause him as little trouble as possible."

Donald tried not to become impatient while these arrangements were being made.

At last dawned that clear April morning when the East was left behind and the journey to the West—that unknown land—was begun. Donald had never been West. The vastness of the country, the newness of the scenery surprised and delighted him. Geography had never seemed so real before. No longer were the various states pink, green, or purple splotches on the map; they were real living places with people, sunshine, and fresh air.

"I had no idea America was so big!" he gasped to his father.

"It's the finest country in the world, Don! Be proud and thankful that you are an American. No other land does so much for her people. Be humble, too. Never let a chance go by to do your part in helping the country that does so much for you."

They were standing in the glassed-in rear of the [19] train, and as Mr. Clark spoke he pointed to vast tracts of forest land that sped past them.

"I am afraid I can't do anything for a great country like this, father," said Donald, a little quiver in his voice.

"There is one thing we can all do—that is be good citizens. Every law we have was made for the good of our people. In so far as you keep these laws you will be aiding in building up a more perfect America. Bear your share in that work—do not be a hindrance, Don."

"I'll try, father," was the boy's grave reply.

To help in the progress of such a land as this! More than once Donald thought of his father's words as the train threaded its way along the banks of mighty rivers, rolled through great woodlands, or skirted cities which throbbed with the life of mighty industries.

And all this vast-reaching land was his country—his!

On every hand there were wonders!

As the express thundered along he poured out question after question. [20]

Why did people go way to Idaho to raise sheep? Why didn't his father raise his sheep in the East? Certainly there was room enough, plenty of room, that was much nearer than Idaho. How did sheep get into the mountains of Idaho anyway?

Mr. Clark ducked his head under the torrent of queries.

"You will drown me with questions!" he exclaimed laughing. "Well, I shall do my best to answer you. New Mexico was the first sheep center in our country. Herds were originally brought from Spain, and these flocks worked their way up from Mexico through New Mexico and California; here the hills supplied the coolness necessary to animals with such thick coats, and furnished them at the same time with plentiful grass for food. During the day the herds grazed, and at night they were driven into corrals of cedar built by the shepherds. These sheep were mostly Merinos, a variety raised in Spain. Afterward, in 1853, a man named William W. Hollister brought three hundred ewes across our continent [21] to the West. Think what a journey it must have been!"

"Wasn't the railroad built?"

"No. Neither were there any bridges. There were rivers to swim and mountains to climb; furthermore there was many a search for water-holes, because Mr. Hollister was not well enough acquainted with the country to know where to find water for himself and the herd."

"I should not think a sheep would have lived through such a journey!" cried Donald.

"Many of them did, however," answered his father, "and that is how our western sheep-raising industry began. Now it is one of the great occupations of our land, and soon you and I are to know more about it."

"And about Sandy McCulloch, too, I hope," put in the boy.

"I hope so; only remember—not a word of that telegram to any one at the ranch. We shall get into Glen City this noon if our train is on time and we must trust to luck in getting to Crescent Ranch. It is fifteen miles [22] from the station, up in the foot-hills of the Rockies."

"The—the—you don't mean the Rocky Mountains!" gasped Donald, his eyes very wide open.

"Certainly. Have you forgotten your geography?"

"Of course I know that a spur of the Rocky Mountains does run diagonally across Idaho; but somehow I never thought of really being in the Rocky Mountains!"

Mr. Clark enjoyed the outburst.

"To be where there are bears and bob-cats and——"

"Maybe, after all, you would rather have stayed at home and finished out your school year."

"I rather guess not!" was the lad's emphatic reply.

So impatient was he to see the marvels of this magic land that the last few hours of the journey seemed unending.

But they did end.

Toward noon the heavy train pulled into Glen City and they bundled out on to the platform. [23] They were the only passengers, but there was a great deal of freight—boxes, barrels, and cases of provisions. As they stood hesitating as to what they had better do a tall, bony young fellow approached the station agent and called with a decided suggestion of the Highlander in his accent:

"I dinna see those kegs of lime for Crescent Ranch, Mitchell."

"They're here. You will find them at the end of the platform. Come, and I'll help you pile them on your wagon."

Mr. Clark turned to the Scotchman.

"Are you going to Crescent Ranch?"

"Aye, I be, sir."

"Can you take my son and me along?"

The Scotchman studied him carefully.

"Have you business at the ranch?" he asked, looking keenly into the eyes of the speaker.

Mr. Clark met his gaze good-naturedly.

"We might possibly have," he answered. "At any rate we want to go up there. My name is Clark and I come from Boston." [24]

"Clark, did you say, sir?"

"Yes."

The stolid stare of the Scotchman did not waver.

"Mayhap you're the owner, sir."

"Yes, I am."

A gleam of something very like satisfaction passed over the tanned features of the young man. Then his face settled back into its wonted calmness.

"It's welcome you are, sir," he said heartily. "I dinna think there'll be trouble about taking you and your son to Crescent."

He wheeled and led the way to a wagon, where he piled up some sacks of grain for his guests to sit upon. Then he lifted in their luggage and the freight for which he had come, and gathered the lines over the backs of his horses.

As the wagon toiled up the long, low hills Mr. Clark began asking questions about the ranch—he asked many questions concerning the country and the flocks. To all of these he received terse answers.

Presently the Scotchman turned. [25]

"It's little you be knowin' of sheepin', sir."

The remark was made with so much simplicity that it could not have been mistaken for rudeness.

"Very little."

"Keep it to yourself, man," was the laconic advice the Highlander tossed over his shoulder as he transferred his attention to his horses.

Mr. Clark bit his lip to hide a smile.

"What is your name, my lad?" he asked suddenly.

"Sandy McCulloch, sir," was the quiet answer.

Donald waited, listening eagerly to every turn of the conversation that followed, but to his astonishment neither his father nor Sandy McCulloch spoke one word regarding the mysterious telegram.

It was nightfall when the wagon that had brought them turned into a muddy drive and stopped before a bare looking house situated in a meadow, and surrounded by a number of vast barns and sheep-pens. Out of this house came a broad-shouldered, bronzed man who stood on the steps, waiting their approach. He wore trousers [26] of sheepskin, a soiled flannel shirt, and round his neck—knotted in the back—was a red handkerchief. Donald noticed that into his belt of Mexican leather was tucked a revolver. He stared at the strangers inquiringly.

Mr. Clark jumped out as soon as the wagon stopped, and extended his hand.

"I do not know your name," he said pleasantly, "but mine is Clark. My son Donald and I have come from Boston to see the ranch."

The man sprang forward.

"I'm Tom Thornton, sir. What a pleasure to have a visit from you! Such an unexpected visit, too."

He slapped Mr. Clark heartily on the shoulder and took Donald's hand in a tight grip.

But though he talked loudly, and laughed a great deal while carrying in their luggage, for some reason Donald felt certain that really Tom Thornton was not glad to see them at all.

The next morning both Donald and his father were astir early.

The next morning both Donald and his father were astir early.

There was nothing to keep them within the great chilly house, and everything to lure them into the sunshine. The sky was without a cloud, and into its blueness stretched distant ranges of hazy mountains at whose feet nestled lower hills covered with faint green. Near at hand patches of meadow were toned to grayish white by grazing bands of sheep. On the still air came the flat, metallic note of herd-bells, and the bleating of numberless unseen flocks within the pens and barns. [28]

What a novel scene it was!

The newcomers found their way to a sheltered corner where they could look out before them into the vastness.

It was all so strange, so interesting!

Somewhere in the ravine below they could catch the rushing music of a stream which wove itself in and out a maze of rolling hills and was lost at last in the shadows of the green valleys.

As they stood silent and drank in the beauty about them, an angry voice broke the stillness.

It came from the interior of the barn near which they were standing.

"I tell you what, Tom Thornton, I'm with Sandy McCulloch. The sheep always were washed after shearing in Old Angus's day, and in Johnson's as well. That is how Crescent Ranch came to have the good name it now holds. There were no scabby sheep here to infect the rest of the herd."

"What's that to you, Jack Owen? You are here to mind the boss, ain't you? What's the use of our working like beavers for ten days to dip the [29] flock if we don't have to? Dipping is a dirty, tiresome job. You are not in for making work for yourself, are you?"

"The flocks will be ruined!"

"What do you care—they are not your sheep."

"Well, I have been on this ranch a long time, Thornton, and I can't help caring what becomes of 'em. I take the same pride in the place Sandy does. We have won a reputation here for doing things the way they ought to be done—for minding the laws—for having clean, healthy stock. Sandy says he shall dip his herd, anyway."

"Bother Sandy! He's talked to you men until he's got you all upset. You would have been with me if he had kept his mouth shut. But no matter what he says I am running this ranch at present. I mean to run it in the future, too. If you're wise you will do as I tell you."

"Mr. Clark may have something to say about the dipping."

"Don't you fret," sneered Thornton. "I sounded him last night. He's a tenderfoot. I don't believe he knows a thing about sheeping." [30]

Mr. Clark drew Donald into the sun-flooded field before he spoke.

Then, after a thoughtful silence he turned:

"Well, Don?"

"I wouldn't have that Thornton here another day, father!" broke out the boy hotly.

"Slowly, son, slowly! We must be sure about Thornton before we condemn him. He has been ten years on the ranch; more than that, we are without a manager, and we have none in view. Remember 'he stumbles who runs fast.' Take time, Don, take time."

Donald flushed.

"I know it is the best way, but I was so angry to hear him talking that way about you."

"Loyalty is a fine trait, Don." Mr. Clark laid his hand affectionately on his son's shoulder. "I like to see you loyal. But in this matter we must move slowly."

"What about this dipping, father? What is it?"

"Something about washing the sheep. I do not clearly understand it myself." [31]

"Shall you have it done?"

"What do you say?"

"Of course I do not know anything about it," Donald replied modestly, "but somehow I feel as if Sandy and the men are right."

"I think so too."

"Couldn't I ask Sandy what it is, father?"

"I am thinking of asking him myself, Don, if I get a good chance."

The chance came unexpectedly, for at that very moment Sandy McCulloch came out of one of the sheep-pens and crossed the walk to the central barn.

"What are you up to to-day, Sandy?" called Mr. Clark.

"I am going to dip my flock, sir, down in the south meadow."

"I am glad of that, for it will give us a chance to see it done," observed Mr. Clark. Then lowering his voice he asked: "Why do you dip the sheep, Sandy?"

"Are you asking because you want to know?" inquired Sandy with the directness which characterized everything he said. [32]

"Yes, Both Donald and I wish to learn."

"Well, sir, it is this way. After the shearing is over and the fleece removed, the coat of the sheep is light and therefore easily dried. We then take the flocks and run them through a bath of lime and sulphur. Some shepherds prefer a coal-tar dip. Whatever the dip is made of, the purpose is the same. It is to kill the parasites on the sheep and cure any diseases of the eyes. If sheep are not dipped they get the 'scab.' Some bit of a creature gets under their skin and burrows until it makes the sheep sick. Often, too, the wool will peel off in great patches. One sheep will take it from another, until by and by the whole herd is infected."

Mr. Clark nodded.

"I never mean to let a sickly sheep go on the range," continued Sandy. "I try to flax round and find out what is the matter with him so I can cure him. We don't want our herd spoiling the feeding grounds and the water-holes and giving their diseases to all the flocks that graze after them. If we are let graze on the range the least we can do [33] is to be decent about it—that's the way I look at it."

"Have our sheep always been dipped?"

"Aye, sir, that they have—dipped every spring after shearing; then we clipped their feet before they started for the range. Sheep, you know, walk on two toes, and if their feet are not trimmed they get sore from traveling so much. I suppose nature intended sheep to climb over the rocks and wear their hoofs down that way. They have a queer foot. Did you know that there is a little oily gland between the toes to make the hoof moist, and keep it from cracking?"

"No, I guess neither Donald nor I knew that, did we, Donald? Now about this dipping—do you thoroughly understand how it is done, Sandy?"

"I do that, sir."

Donald wondered why his father was so thoughtful.

"How long have you been at Crescent Ranch, Sandy?" asked Mr. Clark at last.

"Ever since I was a lad of fifteen, sir."

"That must be about ten years!" [34]

"Fourteen."

A new thought came to Mr. Clark.

"Why, then you must have known Old Angus," he exclaimed.

"I did, sir."

"He was a fine old man, they tell me."

"He was."

"I never saw him—I wish I had. It was a great loss to the ranch and to all of us when he went."

"It was indeed."

"You must remember him well, Sandy."

Throwing back his head with a gesture of pride, Sandy confronted Mr. Clark.

"I do, sir," he replied simply. "He was my father."

Mr. Clark and Donald stared.

"Why didn't you tell me that in the first place?" cried Donald's father, stepping forward eagerly and seizing the hand of the young ranchman.

"I thought mayhap you knew it. If not—why prate about it? It's on my own feet I must stand and not on my father's. If I am of any use you [35] will find it out fast enough, father or no father; if I'm not 'twere best you found that out as well."

"Independent as your forebears, Sandy!" laughed Mr. Clark.

"I be a McCulloch, sir!" was all Sandy said.

It was a great surprise to Tom Thornton when Mr. Clark informed him that

he wanted the men to start in dipping the sheep as soon as they could

get ready.

It was a great surprise to Tom Thornton when Mr. Clark informed him that

he wanted the men to start in dipping the sheep as soon as they could

get ready.

"I suppose, Thornton, you have everything in readiness for the work," continued the owner casually.

Thornton did not hesitate.

"Yes, indeed, sir. We can start right in to-day if you wish. It is for you to say. But really, Mr. Clark, the flock hardly needs it. Our sheep are in prime condition." [37]

"That's all the more reason for keeping them so, Thornton," was the smiling reply.

"Of course that is true, sir. Very well. We will go ahead. I think I shall have time to give the orders, although I have got to be in Glen City about ten days shipping the clip."

"What?"

"Shipping the wool, sir."

"Oh, yes."

"I can start the work before I go."

"I don't think you need bother, Thornton," remarked Mr. Clark slowly. "You go on down to Glen City and finish up your business there."

"But somebody must see to the dipping if you really want it done."

"I'll attend to it."

"You!"

"Why not?"

"Why—why—nothing, sir. I beg your pardon. Only I thought you might be too tired after your trip."

"Oh, no. I am not tired at all." [38]

Thornton eyed him.

Even Donald was astonished.

Mr. Clark did not seem to be at all disturbed by the embarrassing stillness, but went on shaving down a stick he was whittling.

"I do not mean to manage the dipping myself," he explained at last. "I shall let Sandy McCulloch take charge of it."

"Sandy McCulloch! Why, sir, that boy could never do it in the world! He is a good lad—well enough in his way—but not very smart. Not at all like his father."

"Well, if he has no ability I shall soon find it out. I mean to try him, anyway."

"Oh, you can try him if you like, but I know the fellow better than you do. You are foolish to turn any big work over to him. He can't handle it."

"I intend to give him the chance."

Thornton's annoyance began to get beyond his control.

"Very well. It is not my business," he snapped as he left the room. [39]

The instant he was gone Donald, who could not keep silent another moment, cried:

"Oh, father! I am so glad you are going to let Sandy manage the dipping!"

"It is an experiment, Don. Sandy is young and he may make a mess of things—not because he does not mean well, but because he lacks experience. He has been here a long time, to be sure, but he never has taken any care beyond watching his own flocks."

"I do not think he will fail. The men will all help him. They like him."

"I can see that."

"And I like him too, father."

"So do I, son. I am trusting him with this work not only because I like him but because I feel sure that the son of such a father cannot go far astray. It was a great surprise to me when I found Sandy was the son of Old Angus. You see we all thought so much of the old Scotchman that he was Old Angus to everybody. I had almost forgotten he had another name. I don't think I ever heard any one call him Angus McCulloch in [40] my life. And yet I remember the name now, for I can recall seeing it written out on checks and letters."

"It is a fine name," Donald declared.

"Sandy comes of good stock. I want to help him all I can. If he has the right stuff in him perhaps we can give him a lift. I wish we might, for I feel we owe his father more than we ever can repay."

It was great news to Sandy when he learned that not only was he to dip his own flock, but that into his hands was to be put the dipping of the entire herd.

"I'm no so sure I can manage it, Mr. Clark," he said modestly, lapsing, as he often did, into his broad Scotch. "I'll do the best I can though, sir."

"I am sure you will."

And Sandy did do his best!

The hot dip, with the proper proportions of lime and sulphur, was prepared, and Sandy tested its temperature by seeing if he could bear his hand in it. Then the long cement troughs were filled. These troughs were just wide enough so the sheep [41] were not able to turn. Groups of sheep that had been driven from the larger enclosures to the small pens near the dipping troughs were then hurried, one by one, to the men standing at the head of the troughs; it was the duty of these men to push each sheep in turn down the smooth metal incline into the dip. The sheep slipped in easily. As they swam along through the steaming bath other men were posted midway and when a sheep passed they thrust the head twice under water with their crooks so that the eyes and heads—as well as the bodies—might be cleansed. At the far end of the troughs still other herders helped the bedraggled creatures out onto a draining platform where they dripped for a time and were afterward driven back into their pens.

"I shouldn't think the sheep would ever dry!" Donald remarked to Sandy as they watched the process.

"Oh, they do; only it takes a couple of days—and sometimes more before their wool is thoroughly dry," answered the Scotchman.

Donald looked on, fascinated. [42]

The work proceeded without a hitch.

The sheep were fed into the troughs, hurried on and away, only to give place to others. Whenever the dip cooled a fresh, hot supply was added. Within an hour Donald counted a hundred sheep swim their way through the one trough near which he chanced to be standing.

Sandy McCulloch was everywhere at once—now here, now there, giving orders. Gladly the herders obeyed him. They all liked Sandy, not only for his own sake but for the sake of Old Angus, his father, under whom most of them had worked in years past.

"Sandy's a fine lad!" Donald heard one of the herders say.

"There's not a better on Crescent Ranch!" was the prompt reply from a grizzled old Mexican who was ducking the heads of the herd that sped past him.

"He wouldn't make a bad boss of the ranch," murmured another in an undertone.

Sandy did not hear them. He was too intent on his work. He went about it simply, yet with [44] his whole soul. Day after day his cheery voice could be heard:

"Your dip is cooling, Bernardo! Warm it up a bit. Dinna you know you'll have your labor for your pains unless the stuff is hot as the sheep can bear it? Hurry your flock ahead there, José. Think you we want to be dipping sheep the rest of the season? If those ewes have drained off enough let the dogs drive them back to the pens. They'll rub their sides up against the boards and cleanse the pen as well as themselves. Now bring out the new herd that came last week from Kansas City. You'll find them in pens seventeen and eighteen. We kept them by themselves so they would scatter no disease through the flock. After they are dipped they can be put with the others."

The men took all he said good-naturedly. Sandy used no unnecessary words, but what he did say was crisp and to the point, and the herders liked it. They liked, too, to watch his face when his lips parted and his glistening white teeth gleamed between them. Sandy had a very [45] contagious smile. He worked tirelessly, and ever as he moved about among the sheep two great Scotch collies tagged at his heels. Busy as he was he often bent down to pat one of the shaggy heads, and was rewarded by having the beautiful dogs thrust their long noses into his hand or rub up against his knees. It was amusing to Donald to watch these dogs dash after the sheep and drive them into the pens. Sometimes they leaped on the backs of the herd and ran the entire length of the line until they reached the ones at the front. They then proceeded to bite the necks of these leaders until they turned them in the desired direction. This done, the collies would run back and by nipping the heels of the sheep at the rear they would compel them to follow where they wished to have them go.

Donald had never seen anything like it.

During the time that the dipping process continued he did not lack for entertainment, you may be sure.

"You'll soon have nothing more to do, Sandy," the boy said one night when he and the Scotchman [46] were sitting in the twilight on the steps of the big barn.

"How's that, laddie?"

"Why, the dipping will be over to-morrow, won't it?"

"Yes; but that is only the beginning of trouble. We shall then put the herd out in the wet grass a while and soften their hoofs so they can be trimmed before the flocks start for the range. Then the bells must be put on, and the bands of sheep made up for the herders."

"What do you mean by making up the herd?"

"I'll try to tell you. Sheep, you must know, are the queerest creatures under the blue of heaven. It ain't in the power of man to understand them. Some minutes they are doing as you'd likely think they would; the next thing you know they are all stampeding off by themselves, and try as you will you cannot stop 'em. They dinna seem sometimes to have a bit of brains."

Donald laughed.

"Aye! You may well laugh, sitting here, but [47] it's no so funny when they go chasing after the leaders and jumping over the face of some cliff. Think of seeing a hundred of 'em piled up dead at your feet!"

"Did such a thing as that really ever happen, Sandy?" questioned Donald incredulously.

"It did so. Didn't bears get after a flock on one of the ranges and didn't the whole lot of scared creatures start running? If they had but waited either the dogs or the herders might have driven off the bears. But no! Nothing would do but they must run—and run they did. One after another they leaped over the edge of the rimrock until most of the flock was destroyed. Folks named the place 'Pile-Up Chasm.' It was a sorry loss to the owner."

"But I don't see why——"

"No, nor anybody else," interrupted Sandy. "That's the sort of thing they do. When they are frightened they never make a sound—they just run. If nobody heads them off they are like to run to their death; and when anybody does head them off it must be done carefully or the [48] front ones will wheel about and pile up on all those coming toward them. Lots of sheep are killed in this way. They trample each other to death. Why, once a man down in Glen City was driving a big flock along when around a turn in the road came a motor-truck. The sheep got scared and the front ones whisked straight about. That started others. Soon there was a grand mix-up—sheep all panic-stricken and tramping over each other. The owner lost half his herd. Now you see why we have to have leaders."

"Leaders?"

"Yes. That is one part of making up the herds. We must put some sheep that are wiser than the rest in every flock that they may lead the stupid ones. I dinna ken where they'd be if we didn't. We take as leaders sheep that are 'flock-wise'—by that I mean old ewes or wethers that have long been in the herds and know the ways. Sometimes, also, we put in a goat or two, for a goat has the wit to find water and food for himself. Not so the sheep! Never a bit! You have to lead sheep clean up to grass and to water [49] as well. They can never find anything for themselves."

"Do they know anything at all, Sandy?" queried Donald, laughing.

"They do so. In some ways they are canny enough. They will scent a storm, and when one is coming never a peg will they stir to graze. They give a queer cry, too, when they find water—a cry to tell the others in the flock; and if the water is brackish or tainted they make a different sound as if to warn the herd. Sheep are very fussy about what they drink. It's a strange lot they are, sure enough!"

"I shouldn't think they would know enough to follow their leaders even if they had any," remarked Donald.

"Well, you see there is a sort of instinct born in 'em to tag after each other. Besides, they learn to follow by playing games. Yes, indeed," protested Sandy, as Donald seemed to doubt his words, "sheep are very fond of games. There are a number of different ones that they play. The one they seem to like best is 'Follow the Leader.' [50] I don't know as you ever played it, but when I was a lad I did."

"Of course I have played it. We used to do it at recess."

"Well, the sheep like it as well as you, and it is a lucky thing, for it teaches them one of the very things we want them to learn. They will often start out, one old sheep at the head, and all the others will fall into line and do just what that sheep at the front does. So they learn the trick of keeping their eyes on a few that are wiser than they, and doing what the knowing ones do. They seem to have no minds of their own—they just trail after their leaders. If we can get leaders that are able to see what we want done it is a great help."

"I should think so!"

"When we have selected our leaders we then scatter markers through each band of sheep."

"And what are markers, Sandy?"

"For a marker you must take a black-faced sheep—or, mayhap, one with a crumpled horn; he must have something queer about him so you [51] will know him right off when he is mixed in with the flock. We put these markers at the beginning of every hundred sheep. It makes it easier to keep track of the herd."

"I'm sorry to be so stupid, Sandy," Donald said, "but I don't think I just understand about the markers."

"We have two thousand sheep in a band," explained the herder kindly. "Now if one of our markers is missing we reckon that a hundred sheep are gone. No one sheep ever strays off by himself, you may be sure of that. When sheep stray they stray in bunches. If a marker wanders off you can safely figure that a lot of those around him have gone too. Roughly speaking we call it a hundred."

"But when you have such big bands of sheep and they are moving about I should not think the markers would be in the same place twice," persisted Donald, determined to fathom this puzzling problem.

"You dinna ken sheep, laddie! They are as jealous to keep their rightful place in the flock as [52] school children are to get the first place in the line. They will fight and fight if another takes the position that belongs to them. It is a silly idea, but an aid to the herders."

"And so the leaders and these markers really help the shepherds to manage the flock?"

"Aye. But you're leaving out the shepherd's best helper."

Sandy's face suddenly softened into tenderness.

"His best helper?" repeated Donald.

"Aye, laddie! His dogs!"

Bending down the Scotchman thrust his hand into the ruff of shaggy hair about the neck of one of the collies beside him. There was a low growl from the other dog, who rose and rested his pointed nose on Sandy's knee.

The man laughed.

"Robin," he said, addressing the collie before him, "must you always take it amiss if I have a word for Prince Charlie? You're no gentleman! Down, both of you!"

The collies crouched at his feet.

"I never can speak to one without speaking to [53] the other," he went on. "They are jealous as magpies."

"They are the finest dogs I ever saw, Sandy."

"I pride myself there are not many like them," agreed the herder. "I raised them from puppies and trained them myself. Now Colin, who also goes with me when I go to the hills, is a good dog, but he is not my own. He belongs to the ranch. So do Victor and Hector. You never feel the same toward them as you do with those you have brought up yourself. Robin and Prince Charlie are not to be matched in the county. But to see them at their best you must see 'em on the range."

"I wish I could!"

"So it's to the range you'd be going, is it? Well, well—belike when the herds are made up and we set out your father will let you go up into the hills a piece with me."

"Oh, Sandy," cried the boy, "would you take me? Do you suppose father would let me go?"

"'Twill do no harm to ask him. I must wait, though, until I see the other herders off, and [54] until Thornton is back from Glen City. The flocks must have a few days' rest after the dipping. Poor things! It is a sorry time they have being dipped in that hot bath just after they have lost their thick, warm coats; it makes them more chilly than ever. Then, too, they sometimes get small cuts while they are being sheared and the lime and sulphur makes the bruises smart. I am always sorry for the beasties. Yet after all I comfort myself with thinking that it is better they should be wretched for a little while than to be sick for a long while. It is like sitting in a dark room when you have the measles—you do not like it but you know you will be worse off if you don't do it."

Sandy laughed and so did Donald.

"Then it will be several days before you start for the range, Sandy."

"Yes. I must wait for Thornton. I can't leave your father here alone. He might want me."

"You have been a great help to my father, Sandy."

"It's little enough I've done. I would do a [55] good sight more if the need came. A McCulloch would do anything in his power for Crescent Ranch or its owners."

"I believe you, Sandy."

"You do well to believe me, lad, for I speak the living truth!"

During the next few days preparations for the range went steadily

forward.

During the next few days preparations for the range went steadily

forward.

Most of the herders had been so long at Crescent Ranch that they knew exactly what to do. It was an ancient story to men who had worked under Old Angus and Johnson.

To Donald, however, everything was new. From morning to night he trotted after Sandy until one day the young Scotchman remarked with a mischievous smile:

"You put me verra much in mind of one of my collies—I declare if you don't!" [57]

The boy chuckled.

"It is all so different from anything I ever saw before, Sandy. I am finding out so many things! Why, until yesterday I thought sheep were just sheep—all of them the same kind. Father mentioned Merinos, and I supposed they were all Merinos."

"Well! Well! And so you have found out that they are not all the same kind? How many kinds have you learned about, pray?"

Donald took Sandy's banter in good part.

"You needn't laugh, Sandy," he said. "Lots and lots of our sheep are Merinos, aren't they?"

"Aye, laddie. Merinos are a good sheep for wool-growing. They are no so bonny—having a wrinkled skin and wool on their faces; they are small, too. But their coat is fine and long, and they are kindly. The American Merinos are the best range sheep we have, because they are so hardy and stay together so well. Some sheep scatter. It seems to be in their blood to wander about. Of course you can't take sheep like that on the range. They would be all over the state." [58]

"I should think it would be a great bother to cut the wool from a Merino when he is so wrinkly," suggested Donald thoughtfully.

"You show your wit—it is a bother. It takes much longer to clip them than it does a smooth-skinned sheep. Besides, their fleece is heavy, for it contains a great deal of oil—or as we call it, yolk. But have done with Merinos. What others did you learn about?"

"One of the herders told me about the Delaine Merinos and showed me the long parallel fibers in their wool; he also pointed out a French Merino, or—or—a——"

"Rambouillet!" laughed Sandy. "I was waiting to hear you twist your tongue around that word. It took me full a week to learn to say it, and even now I never say it in a hurry. We have many a French Merino here; they belong, though, to quite a different family from the other Merinos. You will find them a much larger sheep, and their wool coarse fibered. They are great eaters, these French Merinos."

"Like me!" cried Donald. [59]

"Verra like you!" agreed Sandy. "But it is no so easy filling them up. Why, they will eat a whole hillside in no time. They can beat you, too, on staying out in all sorts of weather. Here in Idaho we generally have fairly mild winters, so our sheep can be out all the year round. We have a few shacks down in the valley where we can shelter them if we have cold rains during the season. They feed down there along the river, eating sage-brush and dried hay from fall until spring. It is often scant picking, but if it is too scant we give them grain, alfalfa hay, or sometimes pumpkins."

"Why, I never dreamed they stayed out all winter!" ejaculated Donald, opening his eyes.

"In a state where it is as mild as this one they can. Then in the spring when the shearing, dipping, and all is done, we start for the range. We never go, though, until the sun has baked the grass a while, for if the herd crops too early the sheep pull at the new shoots that are just taking hold in the soil and up they come—roots and all. Then in future you will have no grass—just bare ground. Very early grass is bad for sheep, too." [60]

"What do people do where there are no ranges, Sandy?"

"Their sheep are kept in great fenced-in pastures and fed from troughs or feeding racks. They have alfalfa hay, turnips, rape, kale, corn, pumpkins and grain. The range sheep are the hardiest, though. Sheep were made to climb and scramble over rocky places, and they are stronger and healthier for doing it."

"I'd rather be a range sheep!" declared Donald.

"And I!" agreed Sandy promptly. "But you're no through telling me about the sorts of sheep you learned about. Didn't anybody tell you about the Cotswolds?"

Donald shook his head.

"Oh, that's a sad pity. They are such big, grand fellows with their white faces and white legs. And dinna forget the Lincolns. You will have no trouble in knowing a Lincoln. They are the heaviest sheep we have, and their wool is long. A Lincoln is handsome as a painting; in fact I'd far rather have one than some of the paintings [61] I've seen. You want to get sight of one when its fleece is full! We have a scattering, too, of Leicesters and Dorset Horns, but the Dorsets are such fighters that I dinna care much for them. They will even attack the dogs."

"I never heard of sheep doing that!"

"Now and again they will, but not often."

Sandy paused and began to whistle softly to himself.

"Are—are those all the kinds of sheep, Sandy?" ventured Donald at last, after he had waited for some time and there seemed to be no prospect of Sandy coming to the end of his tune.

"All! Hear the lad! All! Indeed and that's not all! There are Cheviots from the English and Scotch hill country. You've had a cheviot suit, mayhap. Yes? Well, that's where you got it. Then there is the Tunis and the Persian. California, Nevada, and Texas raise Persians. They are a fat-tailed sheep. We never went in for them here. In England you will find a host of other sorts of sheep that are raised on the English Downs; most of them are short-haired and are [62] raised not so much for their wool as for their mutton. There are Southdowns, Hampshire Downs, Sussex, Oxfords, Shropshire Downs, and the Dorset Horns. We always like some Shropshires in our herd."

"Oh, Sandy," groaned Donald with a wry smile, "I never, never can remember all these kinds."

"Dinna shed tears about it, laddie. The wool will keep growing on their backs just the same. But it's likely that you'll never again be thinking that a sheep is just a sheep!"

"Indeed I shan't!"

"As for myself," went on Sandy, "I like all kinds; I like the smell of them, and being with them on the range. You'll like the range, too, if your father lets you go. You'll like the big sky, the crisp air, and the peace of it."

"I hope he will let me go."

"Dinna fear! We will ask him to-night or to-morrow. Thornton will be back to-morrow. Then we'll be getting ready the wagons and our own kit."

"What wagons?"

"Did you no see the canvas-topped wagons in [63] the barn? Verra like gipsy wagons they are. We call them prairie schooners because they are the sort of wagon the first settlers crossed the country in. Ships of the Desert they were indeed! In the West we use them even now. When we go to the range three of these wagons go along part way and carry the food, establishing what we call central camps. From these camps provisions are brought to us."

"Don't you come down for your food!" exclaimed Donald, aghast.

"Nay, nay! Never a bit! When we are off, we're off! We never turn back until fall. Our food is sent to us on the range three times a week. A camp-tender comes on horseback bringing supplies on a packhorse or on a little Mexican burro. If we are not too far up in the hills this tender fetches the food all the way; if we are, he leaves it in some spot agreed upon and we go down and get it, leaving the flocks in care of the dogs. The schooners stay near enough to the home ranch so they can go back and forth now and then and get restocked. We ourselves take a few pots and pans [64] to the range—just enough so we can cook our meals. It is like camping out anywhere else."

"I love camping!" cut in Donald.

"Then you'll like the range for certain."

"I know I shall. I hope I can go. What a lot I am learning, Sandy! Pretty soon I shall know more about sheep-raising than father does!"

"Dinna fret yourself about your father," was Sandy's dry retort. "He needs no pity. He can take care of himself."

Tom Thornton, however, did not seem to agree with Sandy's estimate of his employer. The moment he was back from Glen City he sought out Mr. Clark who, with Donald, was sitting before the fire in the barren living-room.

"The clip is off for the East at last, Mr. Clark," he said. "It is likely you will be following it soon yourself now that you have cast your eye over the ranch and found it running all right. Have you come to any decision as to who you'll appoint as manager?"

Thornton glanced keenly at the ranch owner as he put his question. [65]

"I do not think I shall appoint any manager at present, Thornton," replied Mr. Clark slowly. "I am in no haste to return East. Donald and I are enjoying our holiday here tremendously and for a while, at least, I think I shall stay and manage Crescent Ranch myself."

Thornton drew a quick breath.

It was evident that he was amazed and none too well pleased.

"It is hard work, sir—especially when you are not used to it."

"I am accustomed to hard work."

"The men will take advantage of you, sir—if I may be so bold as to say so. They know you were not brought up to sheeping. They will impose on you and shirk their duties."

"I am not afraid, Thornton," was the calm reply. "I have had a chance to test what they would do when they were dipping the sheep. It was as thorough a piece of work as one would wish to see done, and went smoothly as a sled in iced ruts. I never saw better team-work. Sandy directed things most ably." [66]

"Sandy does well enough at times," was Thornton's grudging answer, "but you are depending on him too much. You may regret it later."

"I doubt it."

Thornton turned.

"Wait and see," was his curt reply.

After he had gone out Donald rose and came to his father's side.

"Thornton doesn't like Sandy, father."

"I am afraid he doesn't, Don."

"Why?"

"Think of a reason."

"Because Sandy is the son of Old Angus—is it that?"

"Possibly," responded Mr. Clark, "and yet I think it is not wholly that."

"Because Sandy is so good?"

"Perhaps."

"Because we both like Sandy so much?" persisted the boy.

"I shouldn't wonder."

"Well, I don't see how any one could help liking Sandy! He is the best man on the place. [67] He knows so much, and is so full of fun, father! And he is so kind to his dogs and to the sheep! Why, I believe he loves every sheep on Crescent Ranch."

"I am sure of it."

There was a silence.

"Father," burst out Donald when he could bear the silence no longer, "I believe Thornton wants you to appoint him manager of our ranch."

Mr. Clark's face lighted with pleasure.

"I am glad to hear you call it our ranch, Don," he said. "I want you to grow up and go to college and afterward I wish you to choose some useful work in the world. Whatever honorable thing you elect to do I shall gladly help you to carry out. But if it happened—not that I should ever urge it—but if it happened that by and by you wanted to take part of the care of this ranch on your shoulders it would make me very glad."

"I am sure I should like to," cried Donald impulsively.

"No, no," his father responded, shaking his [68] head. "Do not give your word so thoughtlessly. It is a serious matter to choose what you will do in life. You must take a long time to think about it—years, perhaps. You are only fourteen. There will be many an idea popping in and out of your head between now and the time you are twenty. Just stow the thought away; take it out sometimes, turn it over, and put it back again."

"I will, father."

"And now, just for a moment, let us suppose you really are twenty and are helping me with the ranch. The first thing we should be doing now would be trying to make up our minds about this new manager."

"Yes, I suppose we should."

"What should you say about that?"

"I wouldn't appoint Thornton, father!"

His father smiled at the instant decision.

"You must not be so positive in condemning Thornton, Don. We must be careful that we are right before we turn him down. To have the care of Crescent Ranch is a responsible position. We want a faithful man—somebody we can trust when [69] we are in the East; somebody who will run the ranch exactly as if we were here."

"Thornton wouldn't!"

"That is what I am trying to find out," Mr. Clark said.

"Have you anybody in mind, father—anybody beside Thornton?"

Mr. Clark fingered his watch-chain.

"I am watching my men, Don. It is the little things a man does rather than the big things that tell others what he is. Remember that. Watch the little things."

"I didn't know you were watching anybody at all," avowed Donald. "You did not seem to be doing much but wander round and have a good time."

"I am glad of that," answered his father.

Donald had now been long enough at the ranch so that he had discovered a

number of ways in which he could be of use. Most of his efforts, to be

sure, were confined to aiding Sandy; but as Sandy had almost more work

than he could do he greatly appreciated the boy's help. Donald carried

meal to the feeding-troughs, fed the dogs, ran errands, and carried

messages from one pasture to another. He was not a little proud when one

day Sandy bestowed on him the title of first assistant. To think of

being the assistant of Sandy McCulloch! Donald's heart bounded! Of

course he got tired. [71] The days were long and the work was real. It was,

however, good wholesome work in the open air—work that made his muscles

ache at first and then grow steadily stronger.

Donald had now been long enough at the ranch so that he had discovered a

number of ways in which he could be of use. Most of his efforts, to be

sure, were confined to aiding Sandy; but as Sandy had almost more work

than he could do he greatly appreciated the boy's help. Donald carried

meal to the feeding-troughs, fed the dogs, ran errands, and carried

messages from one pasture to another. He was not a little proud when one

day Sandy bestowed on him the title of first assistant. To think of

being the assistant of Sandy McCulloch! Donald's heart bounded! Of

course he got tired. [71] The days were long and the work was real. It was,

however, good wholesome work in the open air—work that made his muscles

ache at first and then grow steadily stronger.

One evening after he had put in an unusually active day and was sitting in the lamplight with his father Sandy came to the door of the room and asked:

"Might I come in and speak to you and Donald, Mr. Clark?"

Mr. Clark laid down his book. He always enjoyed a talk with Sandy.

"Certainly," he answered. "Come up by the fire, Sandy. The chilly evenings still hang on, don't they?"

"They do so. I'm thinking, Mr. Clark, that now Thornton is back again it is time I started for the range. Some of the herders have gone already, as you know; the rest will be off to-morrow. I ought to be getting under way soon if I want to land my flock in high, cool pasturage before the heat comes."

"Very true, Sandy. I have kept you behind because your aid in starting off the wagons and the [72] other herders was invaluable. But, as you say, there is no need to detain you longer. How soon could you get away?"

"I could start to-morrow if I had my permit."

"How is that?"

"As you remember, sir, we must have permits to graze on the range. You have paid enough money to the government to realize that."

"Yes, indeed. And I never grudge the money, either."

"What are permits, Sandy?" put in Donald eagerly.

"Well, laddie, long ago people who raised horses and sheep wandered over all the mountainsides with their herds, and fed them wherever grass was plenty. It was free land. Anybody could graze there. It was a fine thing for a man with thousands of sheep not to have to pay a cent for their food, wasn't it?"

"Of course."

"You would have thought there would have been enough for everybody to feed their stock peaceably, wouldn't you?" [73]

"Yes, indeed!"

"Well now, it didn't work out so at all. The sheepmen and the cattlemen came to actual war. The cattlemen declared that their herds would not graze where the sheep had been because of some queer odor the sheep left behind them; they argued, moreover, that sheep gnawed the grass off so close to the roots that they destroyed the crop and left barren land. The sheepmen, on the other hand, complained because the cattle—loving to stand in the water—waded into the water-holes and spoiled them. Each faction tried to crowd the other off the range. Dreadful things happened. Vaqueros, or cowboys, would dash on horseback right into the midst of a flock and scatter the sheep in every direction. Often many of the sheep fled into the hills and their owners never could find them again. Or sometimes the cowboys would drive the sheep ahead of them over high precipices. Cattlemen, being on horseback, had a great scorn for sheep-herders, who were obliged to trail their flocks on foot. The feud between the two varieties of stock-raisers became worse and worse." [74]

Donald listened breathlessly.

"More men took up stock-raising as time went on, and in consequence more herds were turned onto the range. Soon the results began to show. The young trees of the forest lands were trampled down, or nibbled and destroyed; water-holes, which the settlers had used as their water supply, began to be polluted; homesteaders, who had built houses and settled in the sheep-raising districts, were driven off the range and had no place where they could be sure of feeding their flocks. The worst evil, though, was that one band of sheep after another would feed in the same spot. The first flock would nip off the top of the grass; the next flock had to eat it closer in order to get food enough; and when the last flocks came they burrowed into the earth with their sharp noses and dug the grass up by the roots. Whole stretches of land that had once been green and beautiful were left bare so that nothing would grow on them for years and years. Cattle do not eat the turf so close as that, and I do not wonder that the vaqueros complained, do you?" [75]

"I should think they would have!" agreed Donald heartily.

"Then, too, the sheep have small, sharp hoofs, you know; these hoofs cut through the soil so that if many sheep travel over a place they grind the earth to powder. Well, that is just what happened. The sheep left the hillsides nothing but patches of brown dust. Things went on from bad to worse until our government stepped in."

Donald kept his eyes intently on Sandy's face.

"What could our government do?" he asked earnestly.

"Well, it could do a good many things, and it did. First, it took about 160,000,000 acres of land as National Forests. It was no longer free pasture. It belonged to the United States."

"I should think the herders would have been pretty cross about that!"

"They were. You can see just how they felt. They made their living by raising stock, and to be deprived of pasturage angered them. At first the government intended to stop all herds from feeding in these National Reserves. They thought [76] it was time to protect the forests that we might not have floods, landslides, and forest fires. They called it conserving the forests. Afterward, though, they considered that the western people made their living by raising cattle and sheep, and they worked out a plan whereby every owner who wanted to graze on the range should pay a certain sum to the United States Government for a permit, and should be allotted a particular pasture for his herd. The only restriction was that if an owner was granted a permit he must promise to obey the rules of the range. It was a wise and just arrangement. Only a certain number of sheep are now allowed to graze on a given area; there is therefore plenty of grass and no need for the flocks to eat the herbage down close and destroy it. The money for the permits, in the meantime, goes to the government, and enriches the United States treasury. Much of this money is spent in paying men to work on the range and better the conditions there, so really it comes back to the people who pay it."

"I understand," Donald replied quickly, when Sandy paused for breath. "It is very interesting [77] isn't it, father? But I do not see how they can prevent herders who have no permits from grazing on the range."

"They ought not to have to prevent them!" answered Sandy, hotly. "The herders ought to be decent enough to obey the law. If you are granted a favor you ought to be a gentleman in accepting it. Now I'm born of generations of shepherds—poor country folk they were, too; but my people ever had a sense of honor—they were gentlemen."

Sandy drew himself up and threw back his head as he spoke the words.

"I cannot imagine a McCulloch being anything but a gentleman, Sandy," said Mr. Clark, who had been listening carefully to Sandy's story of the range.

Sandy was pleased.

"It's many would not think so, Mr. Clark," he replied, as he stretched out his rough, brown hands.

"One can tell nothing from hands," laughed Mr. Clark. "The heart is the thing that tells the tale. A clean, honest heart makes a gentleman, and no one is a gentleman without it." [78]

"But you are not telling me how they kept the herders without permits off the range," put in Donald mischievously.

"I almost forgot. The question always ruffles me. You did a bad thing to stir me up about it. I'll tell you. The United States had to put soldiers on the range—think of it—soldiers to protect the government from its own people! And when the government was working to help those very people, too. They called these soldiers rangers. It was their duty to patrol the dividing line of the National Reserves. Every herder who passed in must show his permit and let the ranger see that he had with him no more sheep than he ought to have. That was fair, wasn't it?"

"Perfectly!" nodded Donald.

"Alack! It is a sad thing that there are people in the world who do not love their country well enough to obey her laws. If they are too stupid to see the laws are for their good why can't they trust the government? Here the government was going to give the herders better pastures and keep their flocks from being molested in them. [79] Wouldn't you think a man with a grain of sense would see the wisdom of the plan!" Sandy's temper began to rise once more. "But no! The herders just felt the rangers who had been stationed to carry out the laws were enemies who had taken away their freedom. So when the rangers did not see them they tried every way to steal into the reserves without permits. Two men would start with their flocks; one would take the attention of the ranger by showing his permit and while the ranger was busy with him the other man would slide into the reserve far down the line where he was not noticed."

"What a mean trick!" cried Donald. "And what if the ranger happened to see him?"

"Oh, he would gallop after him and ride into his flock, scattering it every which way as he tried to drive the sheep out of the reserve. Often the herder would lose hundreds of them."

"Served him right!"

"That's what I think, too," grinned Sandy. "The like are not all dead yet either—worse luck! And this brings me back to the matter of my [80] permit, Mr. Clark. We are two permits short, sir. The new herds that came from Kansas City are not counted into our old rating. Did you think of that? Having more sheep this year we must pay in more money. You didn't happen to remember, did you, to get permits for those extra flocks?"

"No, Sandy, I didn't; but of course Thornton has attended to it. See, here he comes. We will ask him. Thornton," he called, as the big fellow passed the door, "what are we going to do about permits for the new herds? They are not included in the tax we now pay."

"Don't you worry about more permits, Mr. Clark. I can save you a penny on that," declared Thornton with a knowing wink. "You pay the government enough as it is. Leave it to me, sir. I'll see that the herds get into the range all right, and that it costs you no more. When Sandy goes in he can talk with the ranger. All the rangers know him and they never will suspect him. In the meantime Owen can take the Kansas City herd and slip in further down the line. There is no [81] danger of our being caught. Many a herder has done it and had no trouble."

"There will be no sliding sheep into the reserves without permits while I own Crescent Ranch, Thornton," said Mr. Clark sternly. "We will pay what we owe the government or we will keep fewer sheep."

"I was only trying to save you money, sir," Thornton hastened to explain.

"You took a very poor method to do it," was Mr. Clark's cold reply. "The money part of wool-growing is not your care. You are here to raise sheep in conformity to the laws of your country."

"A mighty poor set of laws they are," grumbled Thornton sullenly.

"You may not like them, but they are for your good nevertheless, and since you are an American it is up to you to obey them. I keep no man in my employ who is not—before everything else—a good citizen."

Thornton flushed, but made no reply.

Then darting an angry glance at Sandy from beneath his shaggy brows, he left the room.

After Donald went to bed that night Mr. Clark and Sandy had a long talk

and the next morning when Donald came to breakfast the first question

his father asked was:

After Donald went to bed that night Mr. Clark and Sandy had a long talk

and the next morning when Donald came to breakfast the first question

his father asked was:

"How would you like to start for the range with Sandy, son, when the permits come?"

"Oh, father! Will you really let me? I have wanted so much to go! I am a good walker, you know, and I am used to camping. Besides, I should like to be with Sandy," he added shyly.

"I am convinced that you could be with no better young fellow in the world, Don, than to be with [83] Sandy McCulloch," replied Mr. Clark warmly. "Yes, I am going to let you go. I want you to help Sandy, however, all that you can. You must not be an idler and make extra trouble. You must take hold and do part of the work if you go. Do not think," he added kindly, "that I consider you a lazy lad, for you are far from it. You have been a great help on the ranch since you came. I have not been ignorant of many thoughtful things that you have been doing to help. I simply wish to remind you that on the range Sandy will have all he can do. In the midst of your pleasure do not forget your obligation to be useful. If you keep your eyes open you will see things that you can do, just as you have seen them here. You will have a thoroughly good time on the range, and I am glad to have you go. A little later I may want you to come back to the ranch to help me. You will be willing to do that, won't you?"

"Of course, father, I'll come whenever you send for me!" was the instant response. "But what are you going to do while I am gone? Can't you come too?" [84]

"I'm afraid not. I do not see how I can leave things here just now. Provisions must be portioned out and sent to the central camps. Then there are many repairs to be made and I must attend to those. I wish, also, to look over the books while I am here. You see I have plenty to do. When I get my work done I may ride up into the hills and join you and Sandy."

"I wish you would," answered Donald. Then he added thoughtfully: "Father, if I stayed and helped you, could you get away any sooner?"

The older man smiled at the boy.

"That is generous of you, Donald boy. I appreciate it. No, I do not see how you could help me by remaining. You go with Sandy and when I need you I will send for you. In the meantime Thornton and I will get on very well here."

"Thornton! Isn't he going to the range with one of the new herds?"

"Not at present. There is a great deal of work to be done here. I prefer to keep him to help me."

"I wish you would have somebody else to help you and let Thornton take the herd, father." [85]

"I think he is better here."

"Very well. You know best," declared Donald. "Shall you really feel all right if I go with Sandy?"

"Yes, indeed. I want you to learn every phase of ranch life that you can. Then if anything ever decided you to take up wool-growing as a business you would come to it with a knowledge I never had. It would be far more interesting on that account. If, on the other hand, you decided on some other work in life you at least would have learned something of one of the great industries of our country and would be a broader-minded citizen in consequence."

"I am sure I should, father. Why, ever since I have seen how big America is I am lots prouder that I am an American."

His father smiled at his enthusiasm, then added gently:

"Yes, but size is not everything. It is what a country is doing, or trying to do, to better the conditions of her people that makes her truly great. You know some of the things that are done [86] to make life happy, healthful, and comfortable for those who live in our cities. Now go out on the range. Look about you. See all that thoughtful, far-seeing men are doing to protect our forests, hillsides, streams; see how our government is entering into the life of those who live not in cities but on farms and ranches. You will find our country is doing much on the range beside merely issuing permits for us to graze there."

"What sort of things?"

"Sandy knows; he'll show you. In spite of the fact that he was born a Scotchman he is as good an American as I know. He appreciates the benefits of this wonderful land enough to desire to be a helpful, law-abiding citizen. He does not accept all the advantages America offers without giving something in return, you see."

"Sandy is too proud to take everything for nothing, father."

"He is also too honest, son. Now go and get your camping traps together. I expect by afternoon to have a telegram that will answer in place of permits until they can be mailed to us. As [87] soon as they come you and Sandy can start off; and in case they do not come to-day I can send them after you by a mounted messenger. So I think you'd better set out anyway. Wear your tramping shoes and carry your sleeping-bag. You better ask Sandy if there is anything else he wants you to take."

Donald needed no second bidding.

He was in the highest of spirits.

An hour later and he had said good-bye to his father and Thornton, and was on his way to the range with Sandy McCulloch. At their backs a band of about two thousand sheep ambled along, the four dogs, Robin, Prince Charlie, Colin, and Hector, dashing in and out among them to keep the stragglers well in the path.

The trail Sandy was following led across the open fields and ascending gradually, made for the chain of low hills faintly outlined in the far-away blue haze. Beyond these hills loomed more distant mountains, their tops capped with snow. These mountains, Sandy told Donald, were the foot-hills of the Rockies. [88]

It was quite evident that Sandy was now in his element. He swung along with slow but steady gait, carrying his pack easily and swinging his staff. His eye was alert for every movement of the flock. Now he would turn and draw some straying creature into place by putting his crook around one of its back legs. Sometimes he would motion the dogs to drive the herd along faster.

To an eastern-bred lad who had lived all his life in a city the scene was wonderfully novel. The great blue stretch of sky seemed endless. How still the country was! Had it not been for the muffled tramp of hoofs, the low bleating of the herd, the flat-toned note of the sheep-bells, there would not have been a sound. The quiet of the day cast its spell everywhere. Sandy, who was usually chary enough of his words, preserved even a stricter silence. Although his lips were parted with a contented smile, only once did he venture to break the quiet and that was when he softly hummed a bar or two of "There Were Hundred Pipers"—a favorite song of his. [89]

At last Donald, who was bubbling over with questions, could bear it no longer.

"Are you always so quiet, Sandy, when you go to the range?" he asked.

The Scotchman roused himself.

"Why, laddie, I was almost forgetting you were here! Aye, being with a flock is a quiet life. You have nobody to talk to on the range—nobody except the dogs; so you fall into the way of thinking a heap and saying but little. I like it. Some herders, though, find it a hard sort of existence. Many a man has sat alone day after day on the range, watching the sheep work their way in and out of the flock until in his sleep he could picture that sea of gray and white moving, moving, moving! It was always before him, sleeping or waking. It is a bad thing for a shepherd to get into that state of mind. We call it getting locoed."

"What does that mean?"

"You must know that on the hills grows a weed called loco-weed. Sometimes the sheep find and eat it, and it makes them dull and stupid—you know how you feel when you take gas to have [90] your teeth pulled. Yes? Well, it's like that. We never let the herd get it if we can help it, and if they do we drive them away from it. They will go right back again, too, and eat more if you do not watch them. That's what loco-weed is."

"And the shepherds?"

"When a man gets dull and stupid by being alone so much, and sees sheep all the time—even when his eyes are shut—the best thing he can do is to leave the range. Some folks can stand being alone, others can't. Why, I have known of herders being alone until they actually wouldn't talk—they couldn't. They didn't want to speak or be spoken to and were ready to shoot any one who came upon them on the range and disturbed them. Once I knew of a herder leaving a ranch because the boss said good-morning to him. He complained that things were getting too sociable."

"I should think the herders would like to see people when they are alone so much."

"Aye. Wouldn't you! But no. In Wyoming there is a law that no herder shall be sent out alone to tend flocks; men must go in pairs. More than [91] that they must have little traveling libraries of a few books. The reason for that is to prevent them from sitting with their eyes fixed vacantly on the moving sheep all the time. It is a good law. Some time, likely, they will have it in all the states."

"I mean to tell father about it. We could do that at our ranch easily," said Donald. "Do you get lonely on the range, Sandy?"

"Nay, nay, laddie. It is many a year that I have been alone on the hills. I love it. There is always plenty to do. Sometimes I play tunes on my harmonica. Again I'll spend weeks carving flowers and figures on a staff. Then I have my dogs, and they are rare company. I sleep a good part of the day, you know, and watch the flock at night."

"But I should think you would sleep at night."

"I couldn't do that."

"Why not?"

"Because there is more danger to the sheep at night. It is then that the wild creatures steal down and attack the herds." [92]

"Wild creatures?"

"Bears, bob-cats, cougars, and coyotes."

"On the range!" cried Donald.