The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Western World, by W.H.G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Western World

Picturesque Sketches of Nature and Natural History in North

and South America

Author: W.H.G. Kingston

Illustrator: D. Yan, W.H. Freeman, Etherington and Others.

Release Date: February 28, 2008 [EBook #24715]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WESTERN WORLD ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

W.H.G. Kingston

"The Western World"

Preface.

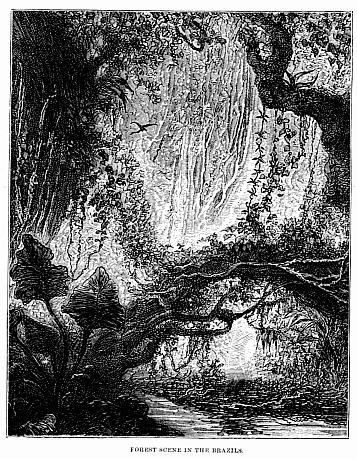

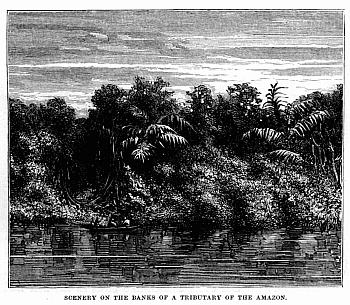

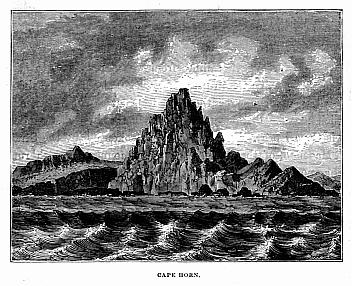

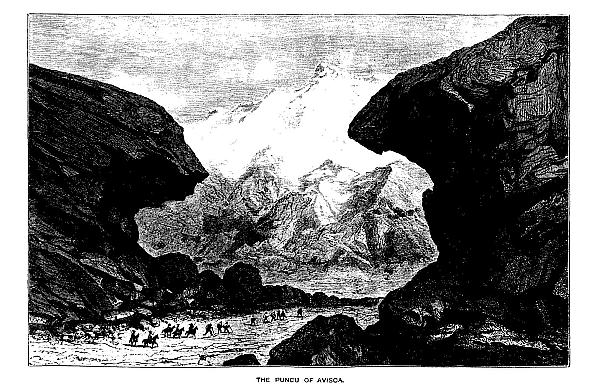

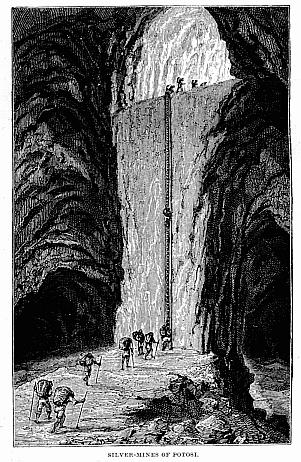

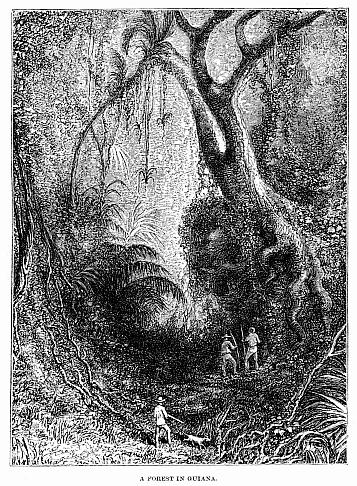

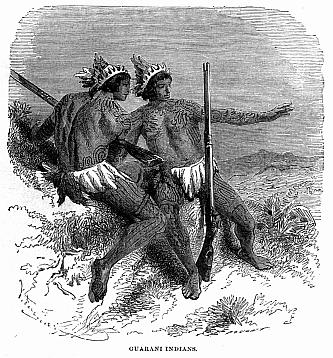

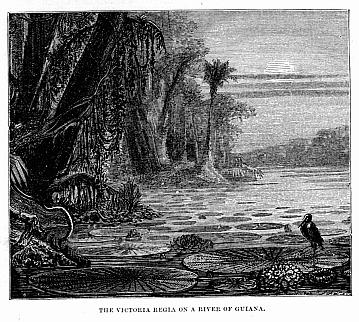

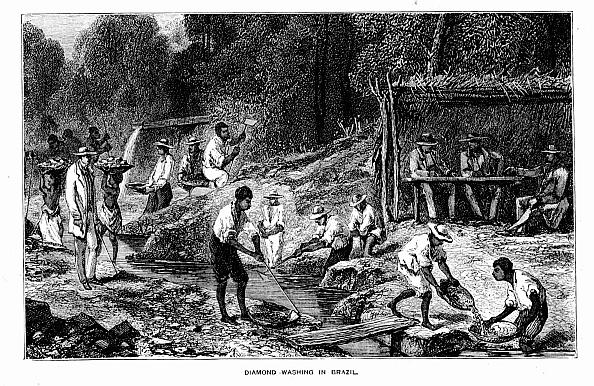

In the following pages I have endeavoured to give, in a series of picturesque sketches, a general view of the natural history as well as of the physical appearance of North and South America.

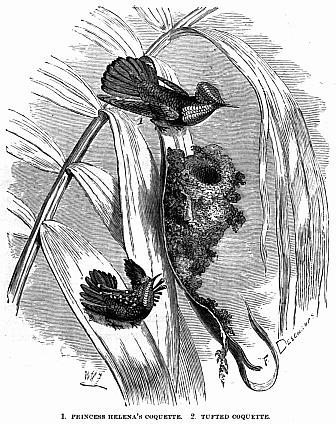

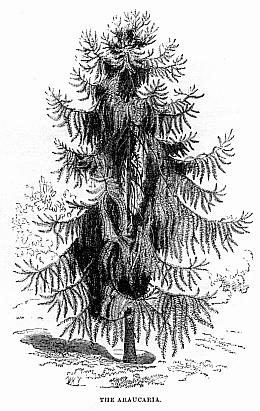

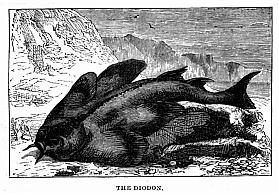

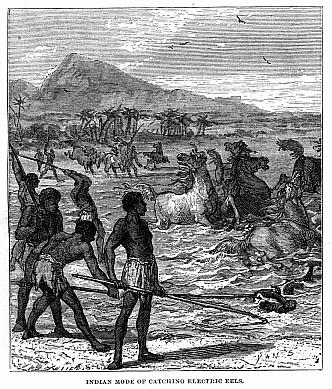

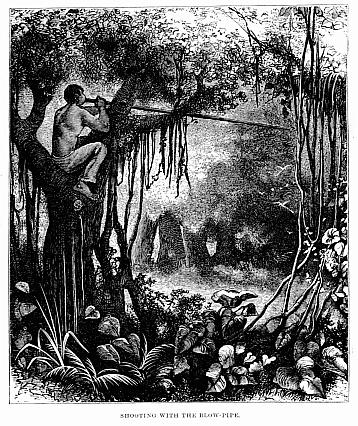

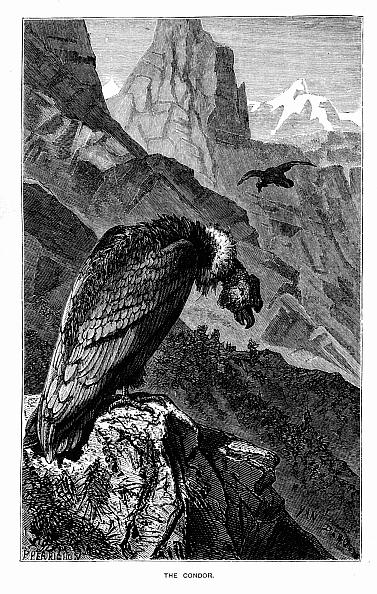

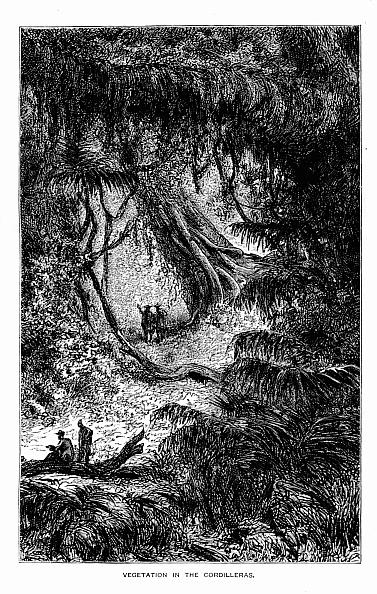

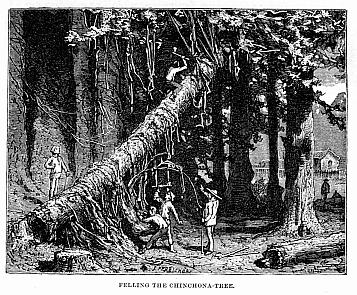

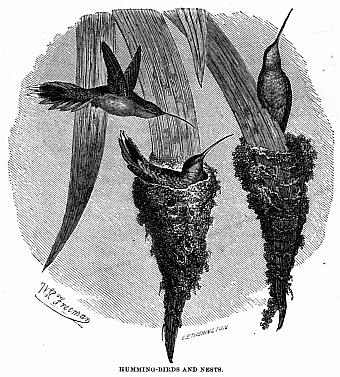

I have first described the features of the country; then its vegetation; and next the wild men and the brute creatures which inhabit it. However, I have not been bound by any strict rule in that respect, as my object has been to produce a work calculated to interest the family circle rather than one of scientific pretensions. I have endeavoured to impart, in an attractive manner, information about its physical geography, mineral riches, vegetable productions, and the appearance and customs of the human beings inhabiting it. But the chief portion of the work is devoted to accounts of the brute creation, from the huge stag and buffalo to the minute humming-bird and persevering termites,—introduced not in a formal way, but as they appear to the naturalist-explorer, to the traveller in search of adventures, or to the sportsman; with descriptions of their mode of life, and of how they are found, hunted, or trapped. I have described in the same way some of the most remarkable trees and plants; and from the accounts I have given I trust that a knowledge may be obtained of the way they are cultivated, and how their produce is prepared and employed. Thus I hope that, with the aid of the numerous illustrations in the work, a correct idea will be gained of the wilder and more romantic portions of the great Western World.

William H.G. Kingston.

Part 1—Chapter I.

North America.

Introductory.—Physical Features of North America.

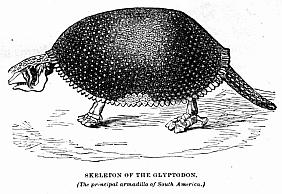

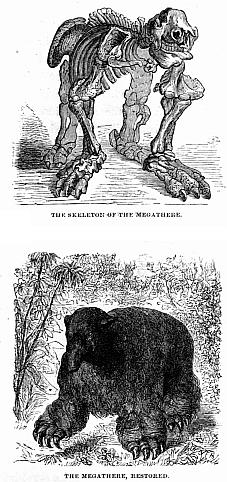

The continent of America, if the stony records of the Past are read aright, claims to be the oldest instead of the newest portion of the globe. (According to some geologists, Labrador was the first part of our globe’s surface to become dry land.) Bowing to this opinion of geologists till they see cause to express a different one, we will, in consequence, commence our survey of the world and its inhabitants with the Western Hemisphere. From the multitude of objects which crowd upon us, we can examine only a few of the most interesting minutely; at others we can merely give a cursory glance; while many we must pass by altogether,—our object being to obtain a general and retainable knowledge of the physical features of the Earth, the vegetation which clothes its surface, the races of men who inhabit it, and the tribes of the brute creation found in its forests and waters, on its plains and mountains.

As we go along, we will stop now and then to pick up scraps of information about its geology, and the architectural antiquities found on it; as the first will assist in giving us an insight into the former conditions of extinct animals, and the latter may teach us something of the past history of the human tribes now wandering as savages in regions once inhabited by civilised men.

Still, the study of Natural History and the geographical range of animals is the primary object we have in view.

Though the best-known portions of the Polar Regions are more nearly connected with North America than with Europe or Asia, we propose to leave them to be fully described in another work. It is impossible, in the present volume, to embrace more than the continental parts of the Western World.

Looking down on the continent of North America, which we will first visit, we observe its triangular shape: the apex, the southern end of Mexico; the base, the Arctic shore; the sides, especially the eastern, deeply indented, first by Hudson Bay, which pierces through more than a third of the continent, then by the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, and further south by Chesapeake Bay and the Bay of Fundy. On the western coast, the Gulf of California runs 800 miles up its side, with the Rio Colorado falling into it; and further north are the Straits of Juan da Fuca, between Vancouver’s Island and the mainland, north of which are numerous archipelagoes and inlets extending round the great peninsula of Yukon to Kotzebue Sound.

Parallel with either coast we shall see two great mountain-systems—that called the Appalachian, including the chain of the Alleghanies, on the east, and the famed Rocky Mountains on the west—running from north to south through the continent.

We shall easily recollect the great water-system of North America if we consider it to be represented by an irregular cross, of which the Mississippi with its affluents forms the stem; Lake Superior and the River Saint Lawrence, including the intermediate lakes, the eastern arm; the Lake of the Woods and its neighbours, Lake Winnipeg and the Saskatchewan, the western arm; and the northern lakes of Athabasca, the Great Slave Lake, and the Mackenzie River, the upper part of the cross. If we observe also a wide level region which runs north and south between the Arctic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, bounded on either side by the two lofty mountain ranges already mentioned, we shall have a tolerably correct notion of the chief physical features of the North American continent.

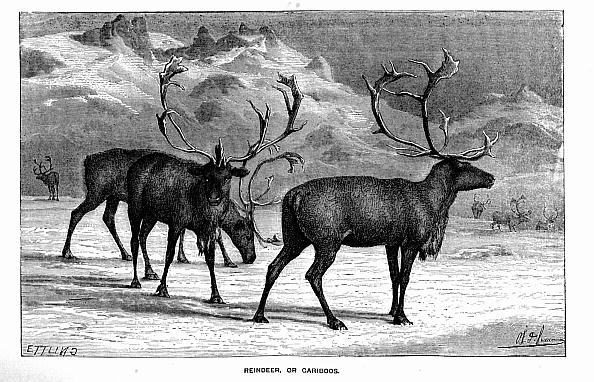

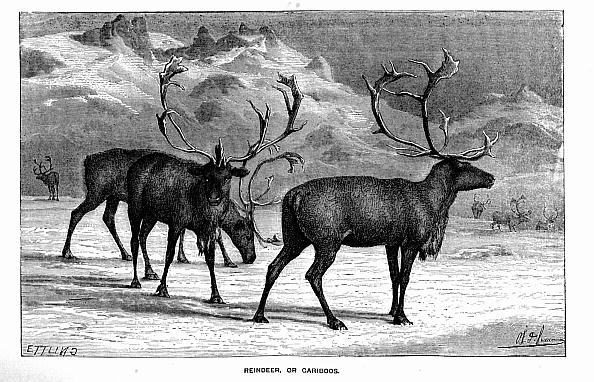

Arriving at the northern end, we shall find it reaching some four degrees north of the Polar Circle, though some of its headlands extend stilt further into the icy sea. Beyond it stretches away to an unknown distance towards the Pole a dense archipelago of large islands, the narrow channels between them bridged over in winter by massive sheets of ice, affording an easy passage to the reindeer, musk-oxen, and other animals which migrate southward during the colder portion of the Arctic winter.

Northern Region.

With that end of America will ever be associated the names of Sir John Franklin and his gallant companions, who perished in their search of the North-west Passage; as well as those of other more fortunate successors, especially of Captains McClure and Collinson of the British navy, to the first of whom is due the honour of leading an expedition from west to east along that icy shore; while Captain Collinson took his ship, the Enterprise, up to Cambridge Bay, Victoria Land, further east than any ship had before reached from the west—namely, 105 degrees west—and succeeded in extricating her from amid the ice and bringing her home in safety. Captain McClure, not so fortunate in one respect, was compelled to leave his ship frozen up. The two expeditions, while proving the existence of a channel, at the same time showed its uselessness as a means of passing from the Atlantic to the Pacific, as, except in most extraordinary seasons, it remains blocked up all the year by ice.

The northern end of the American continent is a region of mountains, lakes, and rivers. Several expeditions have been undertaken through it,—the first to ascertain the coast-line, by Mackenzie, Franklin, Richardson, Back, and others, and latterly by Dr Rae; and also by Sir John Richardson, who left the comforts of England to convey assistance to his long-missing former companions, though unhappily without avail. These journeys, through vast barren districts, among rugged hills, marshes, lakes, and rivers, in the severest of climates, exhibit in the explorers an amount of courage, endurance, and perseverance never surpassed. In the course of the rivers occur many dangerous falls, rapids, and cataracts, amid rocks and huge boulders, between which the voyagers’ frail barks make their way, running a fearful risk every instant of being dashed to pieces. Not a tree rears its head in the wild and savage landscape, the vegetation consisting chiefly of lichens and mosses. Among the former the tripe de roche is the most capable of supporting life. Here winter reigns with stern rigour for ten months in the year; and even in summer biting blasts, hail-storms, and rain frequently occur. Yet in this inhospitable region numerous herds of reindeer, musk-oxen, and other mammalia find subsistence during the brief summer, as do partridge and numerous birds of various species.

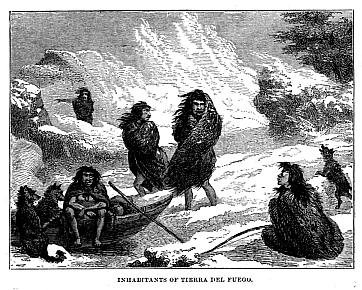

Here the Esquimaux lives in his skin-tent during the warmer months, and in his snow-hut in winter, existing on the seals which he catches with his harpoon, the whales occasionally cast on shore, and the bears, deer, and smaller animals he entraps.

The numerous rivers flowing from the mountain-ridges mostly make their way northward. The Mackenzie, the largest and most western, rising in the Great Slave and Great Bear Lakes, falls, after a course of many hundred miles, into the Polar Sea. The Coppermine River, rising in Point Lake, makes its course in the same direction; while eastward, the great Fish or Back River, flowing from the same lake as the first mentioned stream, reaches the ocean many hundred miles away from it, at the lower extremity of Bathurst Islet. It runs rapidly in a tortuous course of 530 geographical miles through an iron-ribbed country, without a single tree on the whole line of its banks, expanding here and there into five large lakes, and broken by thirty-three falls, cascades, and rapids ere it reaches the Polar Sea. Not far from its mouth rises the barren rocky height of Cape Beaufort.

It was down this stream that Captain Back, the Arctic explorer, made his way, but was compelled to return on account of the inclemency of the weather and the difficulty of finding fuel; the only vegetation which he could discover being fern and moss, which was so wet that it would not burn, while he was almost without fire, or any means of obtaining warmth, his men sinking knee-deep as they proceeded on shore in the soft slush and snow, which benumbed their limbs and dispirited them in the extreme. Through this country the unhappy remnant of the Franklin expedition, many years later, perished in their attempt to reach the Hudson Bay Company’s territory. Here, in winter, the thermometer sinks 70 degrees below zero. Even within his hut, when he had succeeded in lighting a fire, Back could not get it higher than 12 degrees below zero. Ink and paint froze. The sextant cases, and boxes of seasoned wood—principally fir—all split; the skin of the hands became dried, cracked, and opened into unsightly and smarting gashes; and on one occasion, after washing his hands and face within three feet of the fire, his hair was actually clotted with ice before he had time to dry it. The hunters described the sensation of handling their guns as similar to that of touching red-hot iron; and so excessive was the pain, that they were obliged to wrap thongs of leather round the triggers to prevent their fingers coming in contact with the steel. Numbers of the Indian inhabitants of the country perish from cold and hunger every year—indeed, it seems wonderful that human beings should attempt to live in such a country; yet much further north, the hardy Esquimaux, subsisting on whale’s blubber and seal’s flesh, contrives to support life in tolerable comfort.

To the south of the Arctic Circle stunted fir-trees begin to appear, and at length grow so thickly, that it is with difficulty a passage can be made amid them. Frequently the explorer has to clamber over fallen trees, through rivulets, bogs, and swamps, till often the difficulties in the way appear insurmountable to all but the boldest and the most persevering.

Mountains.

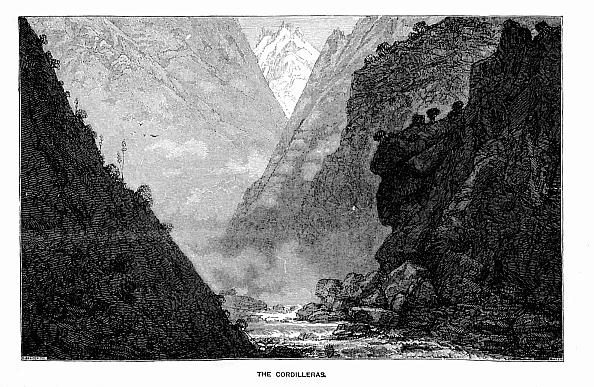

On the western side of the continent rises gradually from the Polar regions the mighty chain which runs throughout its whole length—a distance of altogether 10,000 miles. The northern portion, known as the Rocky Mountains, runs for 3000 miles, in two parallel chains, to the plains of Mexico, flanked by two other parallel ranges on the west,—the most northern of which are the Sea Alps of the north-west coast, and on the southern, the mountains of California. At the north-western end of the Sea Alps rises the lofty mountain of Mount Elias, 17,000 feet in height—the highest mountain in North America—not far from Behring Bay; while another range, the Chippewayan, stretches eastward, culminating in Mount Brown, 10,000 feet in height, and gradually diminishing, till it sinks into insignificance towards the Arctic Circle. Point Barrow is the most northern point of America on the western side. It consists of a long narrow spit, composed of gravel and loose sand, which the pressure of the ice has forced up into numerous masses, having the appearance of rocks. From this point eastward to the mouth of the Mackenzie River the coast declines a little south of east. The various mountain ranges existing on the eastern side of the continent, including the chain of the Alleghanies, form what is called the Appalachian system. It consists of numerous parallel chains, some of which form detached ridges, the whole running from the north-east to the south-west, and it extends about 1200 miles in length—from Maine to Alabama. Besides the Alleghany Mountains in the western part of Virginia and the central parts of Pennsylvania, it embraces the Catskill Mountains in the State of New York, the Green Mountains in the State of Vermont, the highlands eastward of the Hudson River, and the White Mountains in New Hampshire. Mount Washington, which rises to an elevation of 6634 feet out of the last-named range, is the highest peak, of the whole system. To the north of the Saint Lawrence the lofty range of the Wotchish Mountains extends towards the coast of Labrador; while the whole region west and north of that river and the great Canadian lakes is of considerable length, the best-known range being that which contains the Lacloche Mountains, which appear to the north of Lake Huron, and extend towards the Ottawa River. These two great ranges of mountains divide the North American continent into three portions.

Great Rivers.

The rivers which rise on the eastern side of the Appalachian range run into the Atlantic; those which rise west of the Rocky Mountains empty themselves into the Pacific; while the mighty streams which flow between the two, pass through the great basin of the Mississippi, and swell the waters of that mother of rivers. The great valley of the Mississippi, indeed, drains a surface greater than that of any other river on the globe, with the exception perhaps of the Amazon. The Missouri, even before it reaches it, runs a course of 1300 miles, while the Mississippi itself, before its confluence with the Missouri, has already passed over a distance of 1200 miles; thence to its mouth its course is upwards of 1200 miles more. The Arkansas, which flows into it, is 2000 miles long, and the Red River of the south 1500 miles in length; while the Ohio, to its junction with the Mississippi, is nearly 1000 miles long.

North America may be said to contain four great valleys—that of the Mississippi, running north and south; that of the Saint Lawrence, from the south-west to the north-east; that of the Saskatchewan, extending from the Rocky Mountains below Mount Brown to Lake Superior; that of the Mackenzie, from the Great Slave Lake to the Arctic Ocean. Although a large portion of the eastern side of the continent is densely-wooded, there are towards the west, extending from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean, vast plains. In the south they are treeless and barren in the extreme; while advancing northward they are covered with rich grasses, which afford support to vast herds of buffaloes, as well as deer and other animals.

Lakes.

The most remarkable feature in North America is its lake system—the largest and most important in the world. In the north-west, at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, are the Great Bear and Great Slave Lakes, which discharge their waters through the Mackenzie River into the Arctic Ocean. Next we have the Athabasca, Wollaston, and Deer Lakes. In the very centre of the continent are the two important lakes of Winnipeg and Winnipegoos,—the former 240 miles in length by 55 in width, and the latter about half the size. The large river of the Saskatchewan flows into Lake Winnipeg, and with it will, ere long, form an important means of communication between the different parts of that vast district lately opened up for colonisation. At its southern end the Red River of the north flows into it, on the banks of which a British settlement has long been established. Several streams, however, make their way into Hudson Bay. Between it and Lake Superior is an elevated ridge of about 1500 feet in height; the streams on the west falling into Lake Winnipeg, while those which flow towards the east reach Lake Superior.

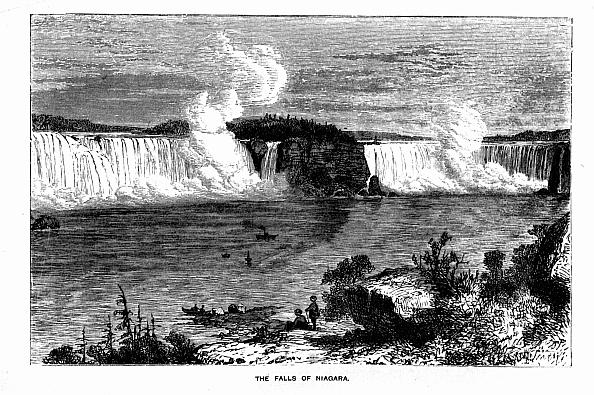

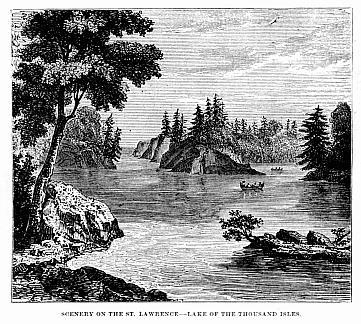

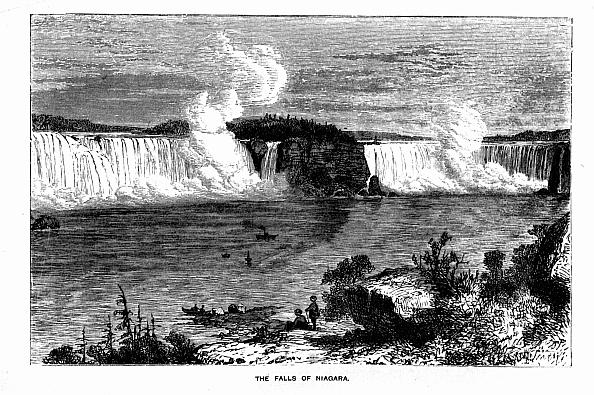

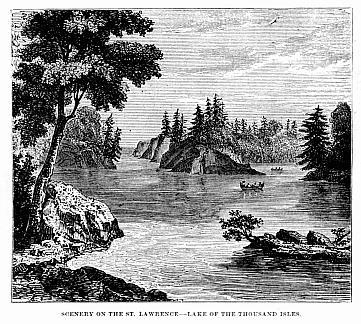

We now come to the site of the five largest fresh-water lakes in the world. Lake Superior extends, from west to east, 335 miles, with an extreme breadth of 175. Its waters flow through the Saint Mary’s River by a rapid descent into Lake Huron, which is 240 miles long. This lake is divided by the Manitoulin islands into two portions, and is connected with Lake Michigan by a narrow channel without rapids, so that the two lakes together may be considered to form one sheet of water. On its southern extremity the waters of Lake Huron flow through another narrow channel, which expands during part of its course into Lake Saint Clair; and they then enter Lake Erie, which has a length of 265 miles, and a breadth of 80 miles. It is of much less depth than the other lakes, and its surface is therefore easily broken up into dangerous billows by strong winds. Passing onward towards the north-east, the current enters the Niagara River, about half-way down which it leaps along a rocky ledge of 100 feet in height, to a lower level, forming the celebrated Falls of Niagara, and then passes on in a rapid course into Lake Ontario. The fall between the two lakes is 333 feet. Lake Ontario is 180 miles long and 65 miles wide. Out of its north-eastern end falls the broad stream which here generally takes the name of the Saint Lawrence, and which proceeds onward, now widening into lake-like expanses full of islands, now compressed into a narrow channel, in a north-easterly direction. The true Saint Lawrence may indeed be considered as traversing the whole system of the great lakes of

North America, and thus being little less than a thousand miles in direct length; indeed, including its windings, it is fully two thousand miles long. To the north-west of it exist countless numbers of small lakes united by a network of streams; while numerous large rivers, such as the Ottawa, the Saint Maurice, and the Saguenay, flow into it, and assist to swell its current. There are numerous other small lakes to the west of the Rocky Mountains, a large number of which exist in the Province of British Columbia, and are more or less connected with the Fraser and Columbia Rivers. Further to the south are other lakes, many of them of volcanic origin, some intensely salt, others formed of hot mud. Among these is the Great Salt Lake, in the State of Utah. To the south of the Saint Lawrence also is Lake Champlain, 105 miles long, though extremely narrow,—being only 10 miles in its widest part, narrowing in some places to half a mile. Near it is the beautiful Lake Saint George, with several other small lakes; and lastly, in Florida, there is a chain of small lakes, terminating in Lake Okechodee—a circular sheet of water about thirty miles in diameter.

North America, and thus being little less than a thousand miles in direct length; indeed, including its windings, it is fully two thousand miles long. To the north-west of it exist countless numbers of small lakes united by a network of streams; while numerous large rivers, such as the Ottawa, the Saint Maurice, and the Saguenay, flow into it, and assist to swell its current. There are numerous other small lakes to the west of the Rocky Mountains, a large number of which exist in the Province of British Columbia, and are more or less connected with the Fraser and Columbia Rivers. Further to the south are other lakes, many of them of volcanic origin, some intensely salt, others formed of hot mud. Among these is the Great Salt Lake, in the State of Utah. To the south of the Saint Lawrence also is Lake Champlain, 105 miles long, though extremely narrow,—being only 10 miles in its widest part, narrowing in some places to half a mile. Near it is the beautiful Lake Saint George, with several other small lakes; and lastly, in Florida, there is a chain of small lakes, terminating in Lake Okechodee—a circular sheet of water about thirty miles in diameter.

We must now proceed more particularly to examine the regions of which we have obtained the preceding cursory view, but, before we do so, we must glance at their human inhabitants.

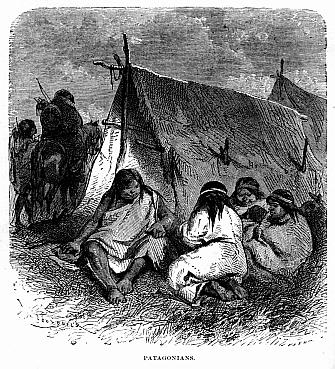

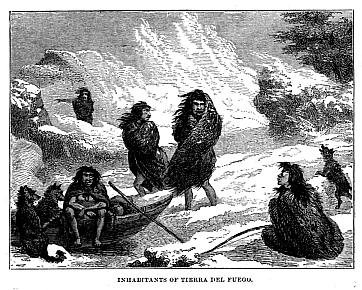

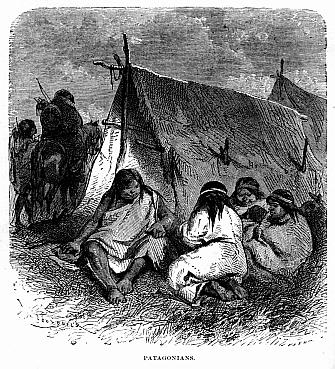

Aboriginal Inhabitants—The Red Men of the Wilds.

While the white men from Europe occupy the whole eastern coast, pressing rapidly and steadily westward, the Redskin aborigines maintain a precarious existence throughout the centre of the continent, from north to south, and are still found here and there on the western shores. On the northern ice-bound coast, the skin-clothed Esquimaux wander in small bands from Behring Strait to Baffin Bay, but never venture far inland, being kept in check by their hereditary enemies, the Athabascas, the most northern of the red-skinned nations. The Esquimaux, inhabiting the Arctic regions, may more properly be described in the volume devoted to that part of the globe.

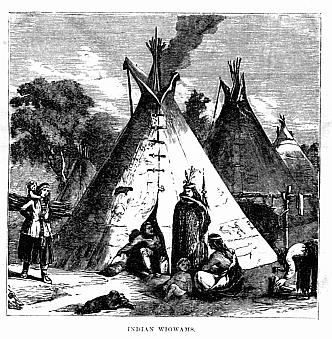

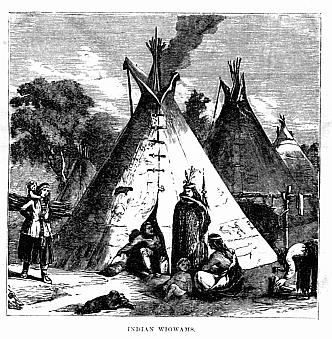

Indian Wigwams.

Here and there, in openings in the primeval forest, either natural or artificial, on the banks of streams and lakes, several small conical structures may be seen, composed of long stakes, stuck in the ground in circular form, and fastened at the top.  The walls consist of large sheets of birch-bark, layer above layer, fastened to the stakes. On the lee-side is left a small opening for ingress and egress, which can be closed by a sheet of bark, or the skin of a wild animal. At the apex, also, an aperture is allowed to remain for the escape of the smoke from the fire which burns within. Lines are secured to the stakes within, on which various articles are suspended; while round the interior mats or skins are spread to serve as couches, the centre being left free for the fire. In front, forked stakes support horizontal poles, on which fish or skins are hung to dry; and against others, sheets of bark are placed on the weather-side, forming lean-tos, shelters to larger fires, used for more extensive culinary operations than can be carried on within the hut. On the shores are seen drawn up beautifully-formed canoes of birch-bark of various sizes—some sufficient to carry eight or ten men; and others, in which only one or two people can sit.

The walls consist of large sheets of birch-bark, layer above layer, fastened to the stakes. On the lee-side is left a small opening for ingress and egress, which can be closed by a sheet of bark, or the skin of a wild animal. At the apex, also, an aperture is allowed to remain for the escape of the smoke from the fire which burns within. Lines are secured to the stakes within, on which various articles are suspended; while round the interior mats or skins are spread to serve as couches, the centre being left free for the fire. In front, forked stakes support horizontal poles, on which fish or skins are hung to dry; and against others, sheets of bark are placed on the weather-side, forming lean-tos, shelters to larger fires, used for more extensive culinary operations than can be carried on within the hut. On the shores are seen drawn up beautifully-formed canoes of birch-bark of various sizes—some sufficient to carry eight or ten men; and others, in which only one or two people can sit.

Appearance of the Indians.

Amid the huts may be seen human figures with dull copper or reddish-brown complexions, clothed in rudely-tanned skins of a yellowish or white hue, and ornamented with the teeth of animals and coloured grasses, or worsted and beads. Their figures are tall and slight. They have black, piercing eyes, slightly inclining downwards towards the nose, which is broad and large. They have thick, coarse lips, high and prominent cheek-bones, with somewhat narrow foreheads, and coarse, dark, glossy hair, without an approach to a curl; their heads sometimes adorned with feathered caps or other ornaments. Often their faces are besmeared with various coloured pigments in stripes or patches—one colour on one side of the face, the other being of a different hue. Their lower extremities are covered with leggings of leather, ornamented with fringes, and their feet clothed in mocassins of the same material as their leggings. The men stalk carelessly about, or repair their canoes or fishing gear and arms; while the women sit, crouching down to the ground, bending over their caldrons, shelling Indian-corn, or engaged in some other domestic occupation; and the children, innocent of clothing, tumble about on the ground. In travelling, the Indian mother carries her child on her back. It is strapped to a board; and when a halting-place is reached, the cradle and the  child are hung upon a tree, or on a pole inside the wigwam. Those who have communication with the whites may be seen clothed in blanket garments, which the men wear in the shape of coats; while the women swathe their bodies in a whole blanket, which covers them from their shoulders to their feet.

child are hung upon a tree, or on a pole inside the wigwam. Those who have communication with the whites may be seen clothed in blanket garments, which the men wear in the shape of coats; while the women swathe their bodies in a whole blanket, which covers them from their shoulders to their feet.

Though the men assume a grave and dignified air when a stranger approaches, they often indulge in practical jokes and laughter among themselves; and in seasons of prosperity, appear good-humoured and merry. The women, however, are doomed to lives of unremitting toil, from the time they become wives. They are compelled to carry the burdens, and to cultivate the ground, when any ground is cultivated, for the production of potatoes, maize, and tobacco. The men condescend merely to manufacture their arms and canoes, and to hunt; or they engage in what they consider the noblest of employments, waging war on their neighbours. The women, indeed, are often compelled to paddle the canoes, sometimes to go fishing, and to carry the portable property from place to place, or an overload of game when captured.

Intelligent as the Indian appears, it is evident that he has cultivated his perceptive powers to the neglect of his spiritual and moral qualities. His senses are remarkably acute. His memory is good; and when aroused, his imagination is vivid, though wild in the extreme. He is warmly attached to hereditary customs and manners. Naturally indolent and slothful, he detests labour, and looks upon it as a disgrace, though he will go through great fatigue when hunting or engaged in warfare.

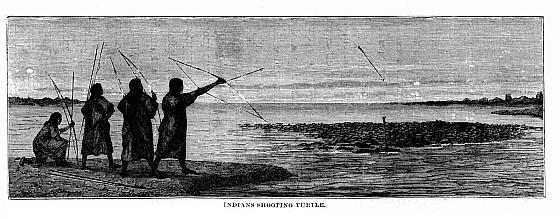

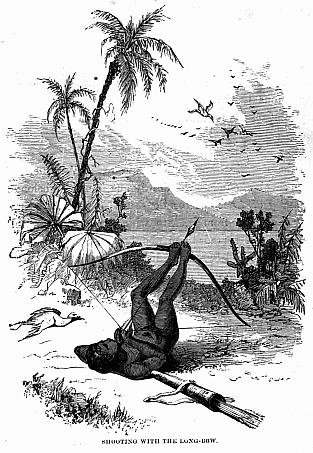

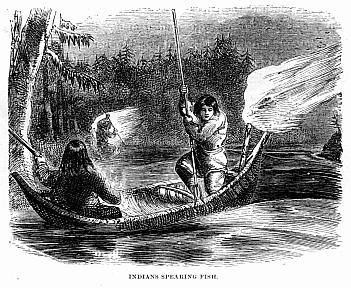

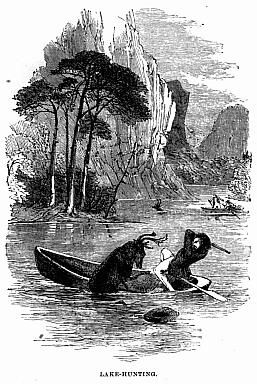

Wood Indians.

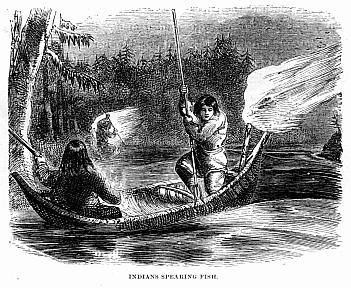

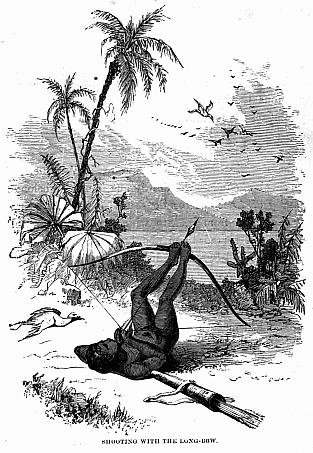

The northern tribes are known as Wood Indians, in contradistinction to the inhabitants of the open country, the Prairie Indians, who differ greatly from the former in their habits and customs. All the tribes of the Athabascas, as well as those to the south of them, known as the Algonquins, are Wood Indians. They are nearly always engaged in hunting the wild animals of the region they inhabit, for the sake of their furs, which they dispose of to the agents of the Hudson Bay Company and other traders, in exchange for blankets,  firearms, hatchets, and numerous other articles, as well as too often for the pernicious fire-water, to obtain even small quantities of which they will frequently dispose of the skins which it has cost them many weeks to obtain with much hardship and danger. These Wood Indians are peaceably-disposed, and can always escape the attacks of their enemies of the prairies by retreating among their forest or lake fastnesses. They obtain their game by various devices, sometimes using traps of ingenious construction, or shooting the creatures with bows and arrows, and of later years with firearms. They spear the fish which abound in their waters, or catch them with scoop and other nets. Although their ordinary wigwams are of the shape already described, some are considerably larger, somewhat of a bee-hive form, covered thickly with birch-bark, and have a raised daïs in the interior capable of holding a considerable number of people. The best-known of these Forest Indians are the Chippeways, who range from the banks of Lake Huron almost to the Rocky Mountains, throughout the British territory.

firearms, hatchets, and numerous other articles, as well as too often for the pernicious fire-water, to obtain even small quantities of which they will frequently dispose of the skins which it has cost them many weeks to obtain with much hardship and danger. These Wood Indians are peaceably-disposed, and can always escape the attacks of their enemies of the prairies by retreating among their forest or lake fastnesses. They obtain their game by various devices, sometimes using traps of ingenious construction, or shooting the creatures with bows and arrows, and of later years with firearms. They spear the fish which abound in their waters, or catch them with scoop and other nets. Although their ordinary wigwams are of the shape already described, some are considerably larger, somewhat of a bee-hive form, covered thickly with birch-bark, and have a raised daïs in the interior capable of holding a considerable number of people. The best-known of these Forest Indians are the Chippeways, who range from the banks of Lake Huron almost to the Rocky Mountains, throughout the British territory.

The Prairie Indians.

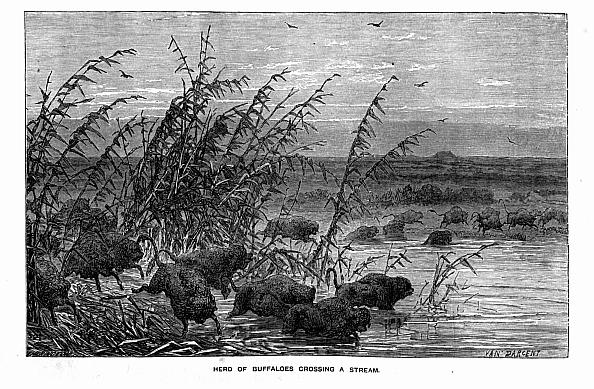

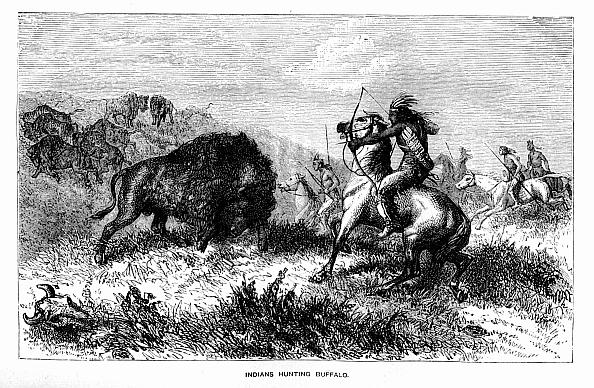

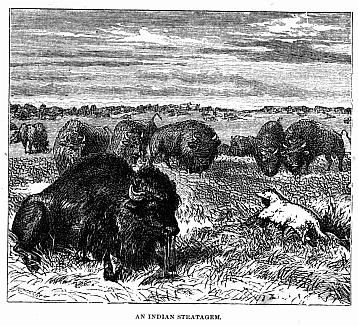

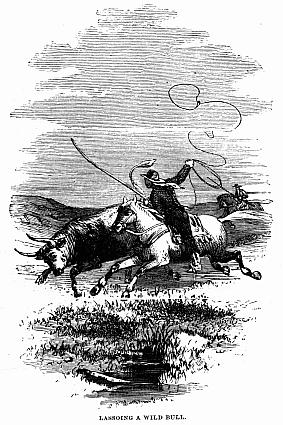

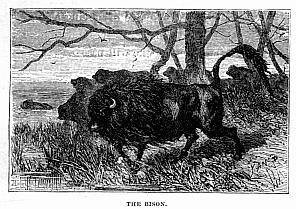

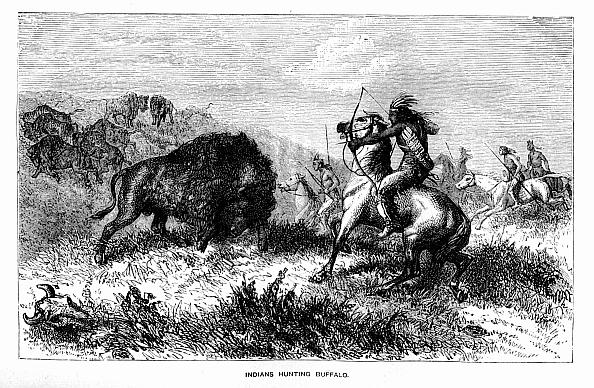

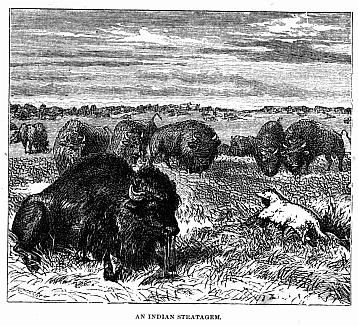

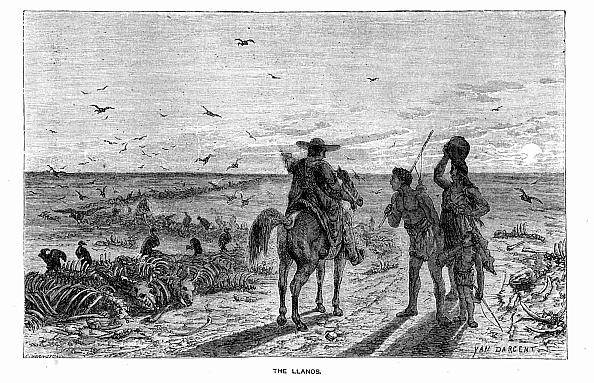

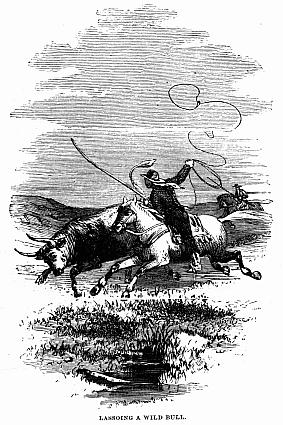

To the south of the tribes already mentioned, are the large family of the Dakotahs, who number among them the Sioux, Assiniboines, and Blackfeet, and are the hereditary enemies of the Chippeways, especially of their nearer neighbours, the Crees and Ojibbeways. These Dakotahs occupy the open prairie country to the south of the Saskatchewan, and are the most northern of the Prairie Indians. In summer, they wear little or no clothing; and possessing numerous horses, hunt the buffaloes, or rather bisons, on horseback, armed with spears and bows and arrows. They are fiercer and more warlike than their northern neighbours, and have long set the whites at defiance. The buffalo supplies them with their chief support. The flesh of the animal dried in the sun, or pounded with its fat into pemmican, is their chief article of food; while its skin serves as a covering for their tents, a couch at night, or for clothing by day, and is manufactured into bags for carrying their provisions, and numerous other articles. Physically, they are superior to the Wood Indians. They are both hunters and warriors; and though they may occasionally exchange the buffalo robes—as the skins are called—for firearms; they seldom employ themselves as trappers, or attend to the cultivation of the ground.

The greater number of the tribes further to the south possess horses, and hunt the buffalo and deer. Some are even more savage than the Dakotahs, while others, again, have made slight progress towards civilisation, and live in settled villages, while they rudely cultivate the ground, and possess herds of cattle.

Although the Indian languages differ greatly from each other, a great similarity in grammatical structure and form has been found to exist among them, denoting a common, though remote origin. They differ, however, so greatly from any known language of the Old World, as to afford conclusive proof that their ancestors must have left its shores at an early period of the world’s history.

The governments also differed. In some tribes it approached an absolute monarchy, the will of the sachem or chief being the supreme law; while in others it was almost entirely republican, the chief being elected for his personal qualities, though frequently the leadership was preserved in the female line of particular families.

When describing the customs of the Indians, we are compelled often to speak of the past, as the tribes, from being pressed together by the advancement of civilisation, have become amalgamated, and many of their customs have passed away. Most of the nations were divided into three or more clans or tribes, each distinguished by the name of an animal. Thus the Huron Indians were divided into three tribes—those of the Bear, the Wolf, and the Turtle. The Chippeways, especially, were divided into a considerable number of tribes.

Religious Belief.

Though their language differs so greatly, as do many of their customs, their religious notions exhibit great uniformity throughout the whole country. They all possess a belief, though it is vague and indistinct, in the existence of a Supreme, All-Powerful Being, and in the immortality of the soul, which, they suppose, restored to its body, will enjoy the future on those happy hunting-grounds which form the red man’s heaven. They also worship numerous inferior deities or evil spirits, whom they endeavour to propitiate, under the supposition that unless they do so they may work them evil rather than good. They suppose that there is one god of the sun, moon, and stars; that the ocean is ruled by another god, and that storms are produced by the power of various malign beings; yet that all are inferior to the Supreme Ruler of the universe. We can trace in some of the tribes customs and notions which have been derived from those of far-distant nations. Thus, the tribes of Louisiana kept a sacred fire constantly burning in their temples: the Natches, as did the Mexicans, worshipped the sun, from whom their chiefs pretended to be descended. By some tribes human sacrifices were offered up,—a custom which was practised by the Pawnees and Indians of the Missouri even to a late period. Several of the tribes buried their dead beneath their houses; and it was an universal custom among all to inter them in a sitting posture, clothed in their best garments, while their weapons and household utensils, with a supply of food, were placed in their graves, to be used when they might be restored to life. Several of their traditions evidently refer to events recorded in Scripture history. The Algonquin tribes still preserve one pointing to the upheaval of the earth from the waters, and of a subsequent inundation. The Iroquois have a tradition of a general deluge; while another tribe believe not only that a deluge took place, but that there was an age of fire which destroyed all things, with the exception of a man and woman, who were preserved in a cavern. Many similar traditions exist; while it is probable that those mentioned refer to the destruction of the Cities of the Plain by fire which came down from heaven, and to the confusion of tongues which fell upon the descendants of Noah in the plain of Shinar.

American Antiquities.

We are apt to suppose that the wild inhabitants of the New World have ever existed in the same savage state as that in which they are found. Vast numbers, however, of remains, and buildings of great antiquity, have of late years been discovered, showing that at one time either their ancestors, or other tribes who have passed away, had made great progress in civilisation. As the white man has advanced westward, and dug deep into the soil, whilst forming railway cuttings, digging wells, and other works, numerous interesting remains have been discovered—a large number of fortified camps of vast extent, and even the foundations of cities, with their streets and squares, have been brought to light. Idols, pitchers of clay, ornaments of copper, circular medals, arrowheads, and even mirrors of isinglass, in great numbers, have been found throughout the country. Some of the articles of pottery are skilfully wrought, and polished, glazed, and burned; inferior in no respects to those of Egypt and Babylon.

In Tennessee, an earthen pitcher, holding a gallon, was discovered on a rock twenty feet below the surface. It was surmounted by the figure of a female head covered with a conical cap. The features greatly resembled those of Asiatics, and the ears, extending as low as the chin, were of great size. Near the Cumberland River an idol formed of clay was found about four feet below the surface of the earth. It is of curious construction, consisting of three hollow heads joined together at the back by an inverted bell-shaped hollow stem. This specimen also has strongly-marked Asiatic features; the red and yellow colour with which it is ornamented still retaining great brilliancy. Another idol, formed of clay and gypsum, was discovered near Nashville. It represented a human being without arms. The hair was plaited, and there was a band round the head with a flattened lump or cake upon the summit. Numerous medals, also, have been dug up, representing the sun, with its rays of light, together with utensils and ornaments of copper, sometimes plated with silver; and a solid silver cup, with its surface smooth and regular, and its interior finely gilt.

But besides these, and very many similar articles, throughout the whole country, and especially towards the west, immense numbers of fortresses of great size have been discovered, with walls of earth, some of them ten feet in height, and thirty in breadth. There is a vast fortress in Ohio, near the town of Newark. It is situated on an extensive plain, at the junction of two branches of the Muskingum. At the western extremity of the work stood a circular fort, containing twenty-two acres, on one side of which was an elevation thirty feet high, partly of earth and partly of stone. The circular fort was connected by walls of earth with an octagonal fort containing forty acres, the walls of which were ten feet high. At this end were eight openings or gateways about fifteen feet in width, each protected by a mound of earth on the inside. From thence four parallel walls of earth proceeded to the basin of the harbour, others extending several miles into the country, and others on the east joined to a square fort containing twenty acres, not four miles distant. From this latter fort parallel walls extended to the harbour, and others to another circular fort one mile and a half distant, containing twenty-six acres, and surrounded by an embankment from twenty-five to thirty feet high. Further north and east the elevated ground was protected by intrenchments. Traces of other walls have been found, apparently connecting these works with those thirty miles distant. When we come to reflect that there were many hundreds of similar forts, some of which were of equal size, and others even of still greater magnitude, we cannot help believing that an enormous population, considerably advanced in the arts of civilisation, must at one time have existed in the country, over which for ages past the untutored savage has roamed in almost a state of nature. And now these wild tribes are rapidly disappearing before the advancement of a still greater multitude, and a far more perfect civilisation. Whether these ancient races were the ancestors of the present Indians or not, it is difficult to determine, as are the causes of their disappearance. It is possible that, retreating southward, they established the empires of Mexico and Peru, or, overcome by more savage tribes, were ultimately exterminated.

Part 1—Chapter II.

North America considered as divided into Four Zones, with the various Objects of Interest found in each.

The North American continent may be divided into four zones or parallel regions, which, from the difference in temperature which exists between them, present a great variety both in their fauna and flora.

The First Zone.

Commencing on the east, where the Greenland Sea washes the coast of Labrador, and Hudson Strait leads to the intricate channels communicating with the Arctic Ocean, we have on the first-named coast a low and level region, which rises inland to a considerable elevation, and then once more sinks on the shores of Hudson Bay. West of that bay there is a wide extent of low country, intermixed with numerous lakes and marshes; and then along the Arctic shore is a wild, barren, treeless district, rising at length into the mountainous region of the Arctic highlands. Amid them numerous rapid streams find their way into the Arctic Ocean. Again they sink into the basin of the Mackenzie River, which separates the in from the northern end of the Rocky Mountains. Hence westward to the Pacific is a broad highland region, rising into the lofty range of the Sea Alps.

The Second Zone.

The Fertile Belt of Rupert’s Land.

The next Zone we will consider as commencing at the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Westward extends an elevated region, rising in many places to a considerable height, and forming the water-shed of the rivers which flow on the south side into the Saint Lawrence, and on the north into Hudson Bay. Proceeding up the Saint Lawrence, we arrive at a great lake district, which embraces Lakes Ontario, Erie, Huron, Michigan, and Superior, to the extreme west. On the north-western shores of that lake we find an elevated district with several small lakes and streams flowing through valleys. This is the water-shed also of two systems. The streams to the east, flowing into Lake Superior, ultimately enter the Saint Lawrence; while those to the west make their way into Lake Winnipeg, the waters of which, after flowing through a variety of channels, fall into Hudson Bay. To the west of this water-shed range the first lake we meet with is known as the Lac des Milles Lacs. Two rivers flow from it, expanding here and there into small lakes, till another expanse of water is reached called Rainy Lake. This in the same way communicates by two streams with the still larger Lake of the Woods, the whole region on both sides being thickly wooded. From the Lake of the Woods flows the broad and rapid Winnipeg River, which finally falls into Lake Winnipeg. This large and long lake is connected with several others of smaller size,—Lake Winnipegoos and Manitoba Lake to the west of it. Into the southern end of Lake Winnipeg flows the Red River, which rises far-away in the south in the United States, taking an almost direct northerly course. Towards the north, about twenty miles from the lake, is situated the well-known Selkirk settlement. To the west of the Red River commences a broad belt of prairie land which extends here and there, rising into wooded heights and swelling hills, with several large rivers flowing through it, to the very base of the Rocky Mountains. As we advance westward we find it extending considerably to the north, where the large and wide river Saskatchewan, rising in the Rocky Mountains, flows eastward into Lake Winnipeg. Along the southern border of this region the Assiniboine River, also of considerable size, flows into the Red River at Fort Garry, in the Selkirk settlement. The prairie country indeed extends further than the Red River, up to the Lake of the Woods. The name of the Fertile Belt has been properly given to it. Commencing at the Lake of the Woods, it stretches westward for 800 miles, and averages from 80 to upwards of 100 miles in width. The area of this extraordinary belt of rich soil and pasturage is about 40,000,000 of acres. Including the adjacent fertile districts, the area may be estimated at not less than 80,000 square miles, or considerably more fertile land than the whole of Canada is supposed to contain. It rises gradually towards the west, so that the traveller is surprised to find how speedily he has gained the passes which lead him over the Rocky Mountains into the territory of British Columbia on their western side—often indeed before he has realised the fact that he has crossed the boundary-line. The Fertile Belt is considerably more to the south than the British Islands, though, as the western hemisphere is subject to greater alternations of heat and cold than the eastern, there is a vast difference in temperature between the summer and winter. While in winter the whole region is covered thickly with snow, in summer the heat is so great that Indian-corn and other cereals, as well as all fruits, ripen with great rapidity. The whole of this fertile region, which now forms part of the Canadian Dominion, is about to be opened to colonisation; and through it will be carried the great high road which will connect the British provinces on the Pacific with those of the Atlantic.

Animal Life on the Fertile Belt.

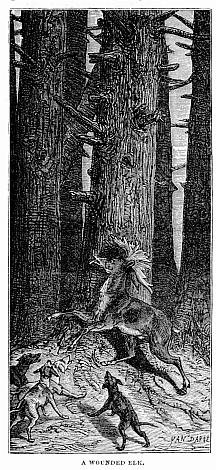

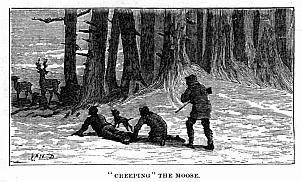

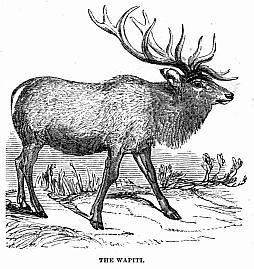

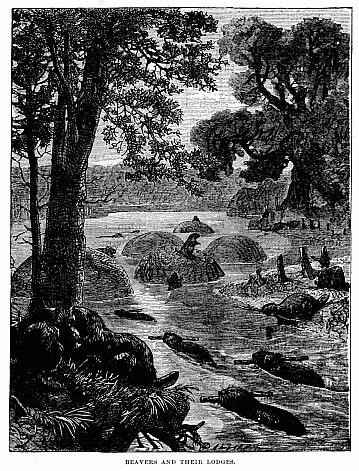

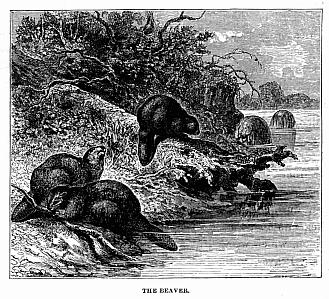

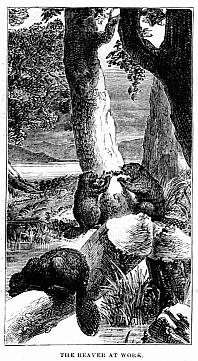

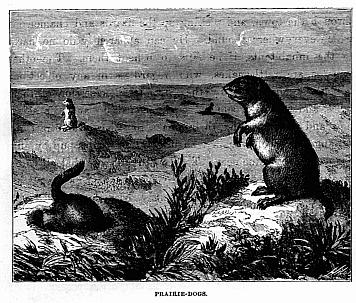

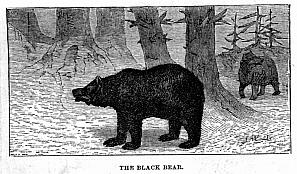

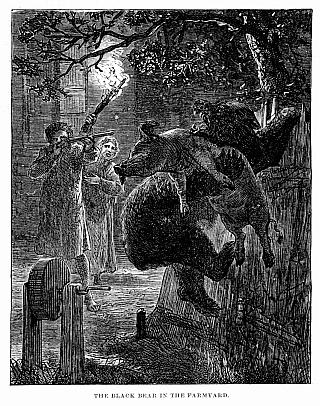

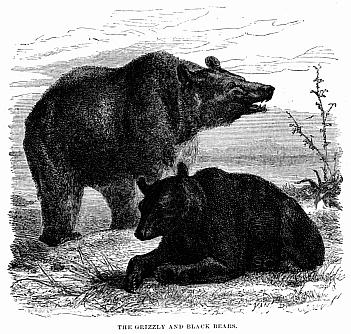

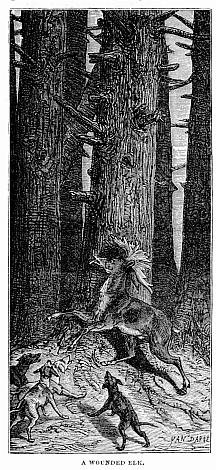

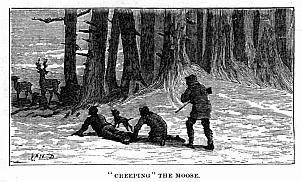

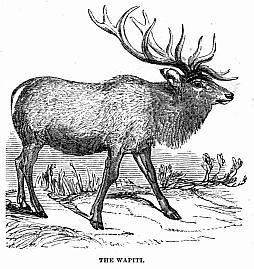

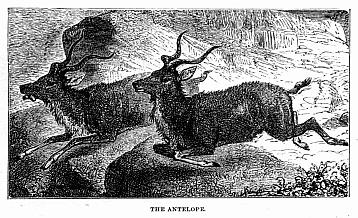

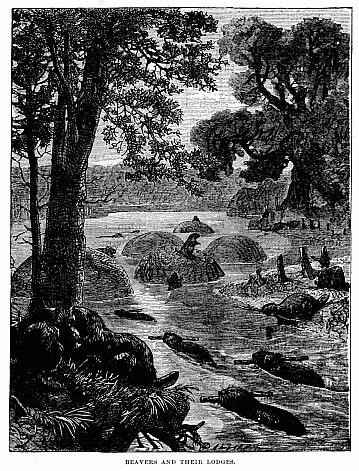

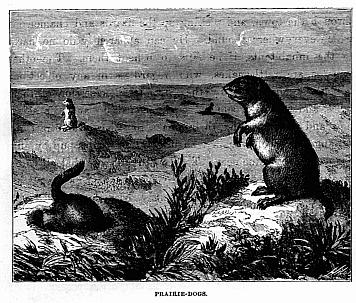

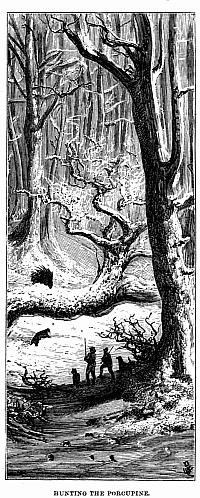

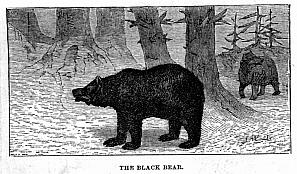

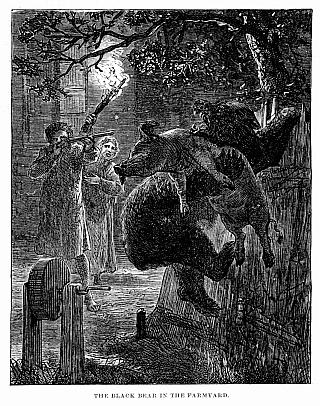

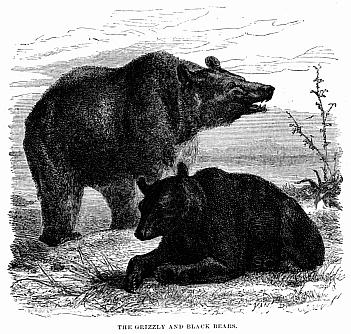

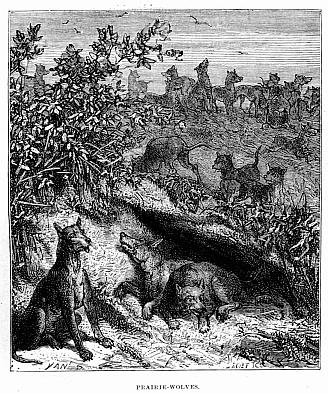

Throughout this fine region range large herds of buffalo,—not extending their migrations, however, beyond its northern boundary. Here, too, are found two kind of small deer—the wapiti, and the prong-horned antelope. Hares—called rabbits, however—exist in great numbers. Porcupines are frequently found. The black bear occasionally comes out of the neighbouring forests, while a great variety of birds frequent the lakes and streams, whose waters also swarm with numerous fish. The white fish found in the lakes are much esteemed, and weigh from two or three to seven pounds. There are fine pike also. Sturgeon are caught in Lake Winnipeg and the Lower Saskatchewan of the weight of 160 pounds. Trout grow to a great size, and there are gold-eyes, suckers, and cat-fish. Unattractive as are the names of the two last, the fish themselves are excellent. Among the birds, Professor Hind mentions prairie-hens, plovers, various ducks, loons, and other aquatic birds, besides the partridge, quail, whip-poor-will, hairy woodpecker, Canadian jay, blue jay, Indian hen, and woodcock. In the mountain region are bighorns and mountain goats; the grizzly bear often descends from his rugged heights into the plains, and affords sport to the daring hunter. The musk-rat and beaver inhabit the borders of the lakes. The cariboo and moose frequent the Fertile Belt, though the musk-ox confines himself to the more northern regions. Wolves have been almost exterminated in the neighbourhood of the Red River settlement. The half-breeds and Indians possess peculiarly hardy and sagacious horses, which are trained for hunting the buffalo. Their dogs are large and powerful, and four of them will draw a sleigh with one man over the snow at the rate of six miles an hour. Herds of cattle, as well as horses and hogs, are left out during the whole winter, it being necessary only—should a thaw come on, succeeded by a frost—to supply them with food; otherwise, unable to break through the coating of ice thus formed, they are liable to starve.

The farmers of the Red River settlement grow wheat, barley, oats, flax, hemp, hops, turnips, and even tobacco, though Indian-corn grows best, and can always be relied on. Wheat, however, is the staple crop of Red River. It is a splendid country for sheep pasturage, and did easier means of transporting the wool exist, or could it be made into cloth or blankets in the settlement, no doubt great attention would be given to the rearing of sheep.

The Third Zone—The Dismal Swamp in the United States.

Returning again to the east coast, about the latitude of Chesapeake Bay and Cape Hatteras, we find a low level region known as the Atlantic plain, running parallel to the coast, on which the long-leaved or peach-pines flourish. This region is generally called the Pine Barrens. Wild vines encircle the trees, and among them are seen the white berries of the mistletoe. In winter these Pine Barrens retain much of their verdure, and constitute one of the marked features of the country. Amid them are numerous swamps or morasses. One of great size, extending to not less than forty miles from north to south, and twenty-five in its greatest width, is called the Great Dismal Swamp.

The soil, black as in a peat-bog, is covered with all kinds of aquatic trees and shrubs; yet, strange to say, instead of being lower than the level of the surrounding country, it is in the centre higher than towards its margin; indeed, from three sides of the swamp the waters actually flow into different rivers at a considerable rate. Probably the centre of the morass is not less than twelve feet above the flat country around it. Here and there some ridges of dry land appear, like low islands, above the general surface. On the west, however, the ground is higher, and streams flow into the swamp, but they are free from sediment, and consequently bring down no liquid mire to add to its substance. The soil is formed completely of vegetable matter, without any admixture of earthy particles. In many even of the softest parts juniper-trees stand firmly fixed by their long tap roots, affording a dark shade, beneath which numerous ferns, reeds, and shrubs, together with a thick carpet of mosses, flourish, protected from the rays of the sun. Here and there also large cedars and other deciduous trees have grown up. The black soil formed beneath, increased by the rotting vegetation, is quite unlike the peat of Europe, as the plants become so decayed as to leave no traces of organisation. Frequently the trees are overthrown, and numbers are found lying beneath the surface of the soil, where, covered with water, they never decompose. So completely preserved are they, that they are frequently sawn up into planks. In one part of the Dismal Swamp there is a lake seven miles in length, and more than five wide, with a forest growing on its banks. The water is transparent, though tinged with a pale brown colour, and contains numerous fish. The region is inhabited by a number of bears, who climb the trees in search of acorns and gumberries, breaking off the boughs of the oaks in order to obtain the acorns; these bears also kill hogs, and even cows. Occasionally a solitary wolf is seen prowling over the morass, and wild cats also clamber amid its woods. Even in summer, the air, instead of being hot and pestiferous, is especially cool, the evaporation continually going on in the wet spongy soil generating an atmosphere resembling that of a region considerably elevated above the level of the ocean. Canals have been cut through this swamp. They are shaded by tall trees, their branches almost joining across, and throwing a dark shade on the water, which itself looks almost black, and adds to the gloom of the region. Emerging from one of these avenues into the bright sunlit lake, the aspect of the scenery is like that of some beautiful fairyland.

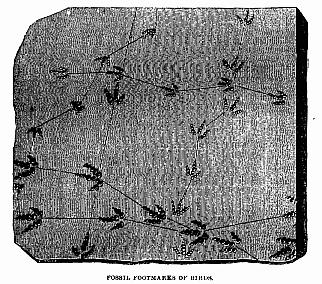

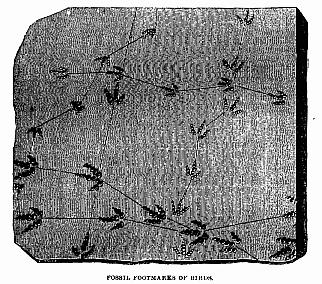

Fossil Footmarks of Birds.

A considerable way to the north of this region, on the banks of the Connecticut River, are beds of red sandstone, on the different layers of which are found the footmarks of long extinct birds. The beds in some parts are twenty-five feet in thickness, composed of layer upon layer; and on each of these layers, when horizontally split, are found imprinted these remarkable footmarks. This result could only have been produced by the subsidence of the ground, fresh depositions of sand having taken place on the layers, on which the birds walked after the subsidence. They must have been of various sizes,—some no larger than a small sand-piper, while others, judging from their footprints, which measure no less  than nineteen inches, must have been twice the size of the modern African ostrich. The distances between the smaller measure only about three inches, but in the base of the largest, called the Ornithichnites Gigas, they are from four to six feet apart. In some places where the birds have congregated together none of the steps can be distinctly traced, but at a short distance from this area the tracks become more and more distinct. Upwards of two thousand such footprints have been observed, made probably by nearly thirty distinct species of birds, all indented on the upper surface of the strata, and only exhibiting casts in relief on the under side of the beds which rested on such indented surfaces. In other places the marks of rain and hail which fell countless ages ago are clearly visible. Sir Charles Lyell perceived similar footprints in the red mud in the Bay of Fundy, which had just been formed by sandpipers; and on examining an inferior layer of mud, formed several tides before, and covered up by fresh sand, he discovered casts of impressions similar to those made on the last-formed layer of mud. Near the footsteps he observed the mark of a single toe, occurring occasionally, and quite isolated from the rest. It was suggested to him that these marks were formed by waders, which, as they fly near the ground, often let one leg hang down, so that the longest toe touches the surface of the mud occasionally, leaving a single mark of this kind. He brought away some slabs of the recently formed mud, in order that naturalists who were sceptical as to the real origin of the ancient fossil ornithichnites might compare the fossil products lately formed with those referable to the feathered bipeds which preceded the era of the ichthyosaurus and iguanodon.

than nineteen inches, must have been twice the size of the modern African ostrich. The distances between the smaller measure only about three inches, but in the base of the largest, called the Ornithichnites Gigas, they are from four to six feet apart. In some places where the birds have congregated together none of the steps can be distinctly traced, but at a short distance from this area the tracks become more and more distinct. Upwards of two thousand such footprints have been observed, made probably by nearly thirty distinct species of birds, all indented on the upper surface of the strata, and only exhibiting casts in relief on the under side of the beds which rested on such indented surfaces. In other places the marks of rain and hail which fell countless ages ago are clearly visible. Sir Charles Lyell perceived similar footprints in the red mud in the Bay of Fundy, which had just been formed by sandpipers; and on examining an inferior layer of mud, formed several tides before, and covered up by fresh sand, he discovered casts of impressions similar to those made on the last-formed layer of mud. Near the footsteps he observed the mark of a single toe, occurring occasionally, and quite isolated from the rest. It was suggested to him that these marks were formed by waders, which, as they fly near the ground, often let one leg hang down, so that the longest toe touches the surface of the mud occasionally, leaving a single mark of this kind. He brought away some slabs of the recently formed mud, in order that naturalists who were sceptical as to the real origin of the ancient fossil ornithichnites might compare the fossil products lately formed with those referable to the feathered bipeds which preceded the era of the ichthyosaurus and iguanodon.

The Big-Bone Lick.

We will now cross the Alleghanies westward, where we shall find a thickly-wooded country. As we proceed onwards, entering Kentucky, we reach a spot of great geological interest, called the Big-bone Lick.

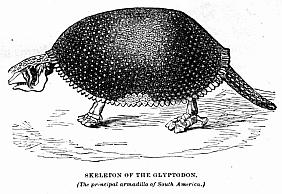

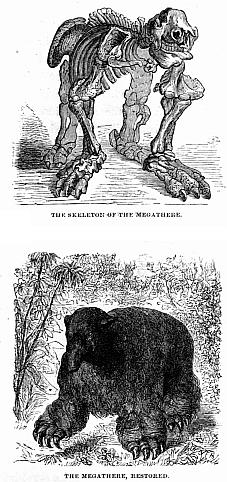

These licks exist in various parts of the country. They are marshy swamps in which saline springs break out, and are frequented by buffalo, deer, and other wild animals, for the sake of the salt with which in the summer they are incrusted, and which in winter is dissolved in the mud. Wild beasts, as well as cattle, greedily devour this incrustation, and will burrow into the clay impregnated with salt in order to lick the mud. In the Big-Bone Lick of Kentucky the bones of a vast number of mastodons and other extinct quadrupeds have been dug up.

This celebrated bog is situated in a nearly level plain, bounded by gentle slopes, which lead up to wide-extended table-lands. In the spots where the salt springs rise, the bog is so soft that a man may force a pile into it many yards perpendicularly. Some of these quaking bogs are even now more than fifteen acres in extent, but were formerly much larger, before the surrounding forest was partially cleared away. Even at the present day cows, horses, and other quadrupeds are occasionally lost here, as they venture on to the treacherous ground. It may be easily understood, therefore, how the vast mastodons, elephants, and other huge animals lost their lives. In their eagerness to drink the saline waters, or lick the salt, those in front, hurrying forward, would have been pressed upon by those behind, and thus, before they were aware of their danger, sank helplessly into the quagmire. It is supposed that the bones of not less than one hundred mastodons and twenty elephants have been dug up out of the bog, besides which the bones of a stag, extinct horse, megalonyx, and bison, have been obtained. Undoubtedly, therefore, this plain has remained unchanged in all its principal features since the period when these vast extinct quadrupeds inhabited the banks of the Ohio and its tributaries. Here and there the Big-bone Lick is covered with mud, washed over it by some unusual rising of the Ohio River, which is known to swell sixty feet above its summer level.

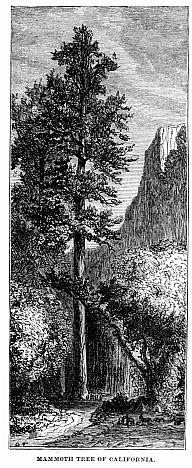

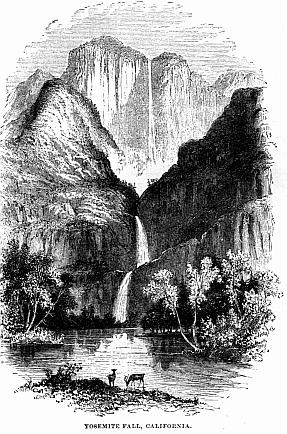

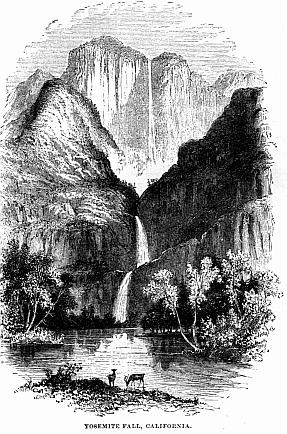

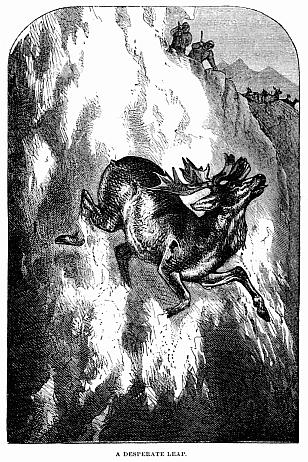

Passing on through wide-spreading prairies, we cross the mighty stream of the Mississippi to a slightly elevated district of broad savannahs, till we reach a treeless region bordering the very foot of the Rocky Mountains. Through this region numerous rivers pass on their way to the Mississippi. Leaving at length the great western plain, we begin to mount the slopes of the Rocky Mountains, when we may gaze upwards at the lofty snow-covered peaks above our heads. Hence, crossing the mighty range in spite of grizzly bears and wilder Indians, we descend towards the bank of the Rio Colorado, which falls into the Gulf of California, and thence over a mountainous region, some of whose heights, as Mount Dana, reach an elevation of 13,000 feet, and Mount Whitney, 15,000 feet.

The Fourth Zone.

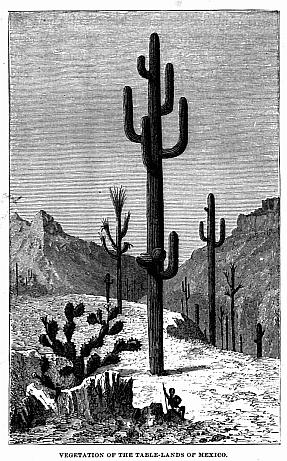

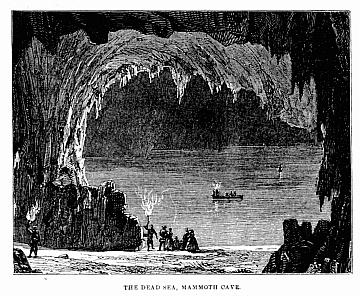

The southernmost of the four zones begins on the coast of Florida, passes for hundreds of miles over a low or gently sloping country toward the great western plains which border the Rocky Mountains into Texas; its southern boundary being the Gulf of Mexico. Through this region flow numerous rivers, the queen of which is the Mississippi. The western portion is often wild and barren in the extreme, inhabited only by bands of wild and savage Indians. The Rocky Mountains being passed, there is a lofty table-land, and then rise the Sierras de los Nimbres and Madre; beyond which, bordering the Gulf of California, is the wild, grandly picturesque province of Sonora, with its gigantic trees and stalactite caves.

Part 1—Chapter III.

The Prairies, Plains of the West, and Passes of the Rocky Mountains.

To obtain, however, a still more correct notion of the appearance of the continent, we must take another glance over it. We shall discover, to the north, and throughout the eastern portion where civilised man has not been at work dealing away the trees, a densely-wooded region. Proceeding westward, as the valley of the Mississippi is approached the underwood disappears, and oak openings predominate. These Oak Openings, as they are called, are groves of oak and other forest-trees which are not connected, but are scattered over the surface at a considerable distance from one another, without any low shrub or underbrush between them.

The Prairies.

Thus, gradually, we are entering the prairie country, which extends as far west as the Grand Coteau of the Missouri. This prairie region is covered with a rich growth of grass; the soil is extremely fertile, and capable of producing a variety of cereals. Over the greater portion of the prairie country, indeed, forests of aspens would grow, did not annual fires in most parts arrest their progress. Here and there numbers have sprung up. The true prairie region in the United States extends over the eastern part of Ohio, Indiana, the southern portion of Michigan, the southern part of Wisconsin, nearly the whole of the states of Illinois and Iowa, and the northern portion of Missouri, gradually passing—in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska—into that arid and desert region known as The Plains, which lie at the base of the Rocky Mountains.

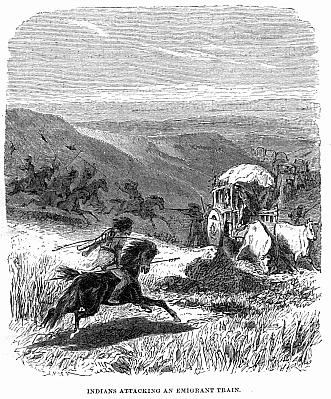

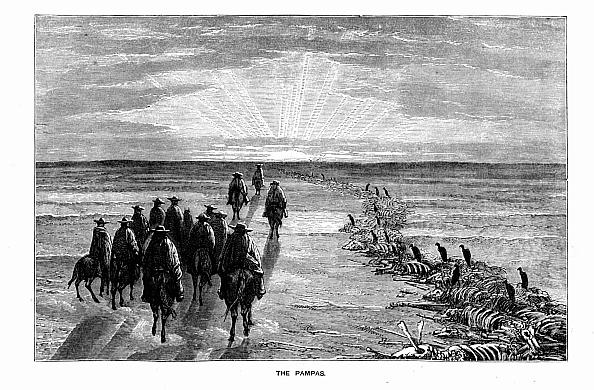

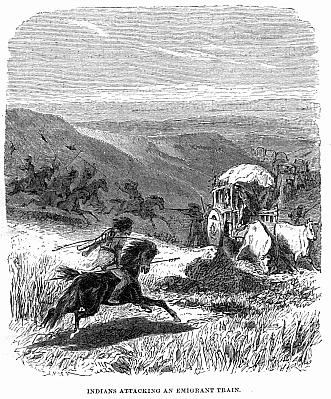

The Grand Coteau de Missouri forms a natural boundary to these arid plains. This vast table-land rises to the height of from 400 to 800 feet above the Missouri. Vegetation is very scanty; the Indian turnip, however, is common, as is also a species of cactus. No tree or shrub is seen; and only in the bottoms or in marshes is a rank herbage found. Across these desert regions the trails of the emigrant bands passing to the Far West have often been marked: first, in the east, by furniture and goods abandoned; further west, by the waggons and carts of the ill-starred travellers; then by the bones of oxen and horses bleaching on the plain; and, finally, by the graves, and sometimes the unburied bodies, of the emigrants themselves, the survivors having been compelled to push onwards with the remnant of their cattle to a more fertile region, where provender and water could be procured to restore their well-nigh exhausted strength. Oftentimes they have been attacked by bands of mounted Indians, whose war-whoop has startled them from their slumbers at night; and they have been compelled to fight their way onwards, day after day assailed by their savage and persevering foes.

Civilised man is, however, triumphant at last, and the steam-engine, on its iron path, now traverses that wild region from east to west at rapid speed; and the red men, who  claim to be lords of the soil, have been driven back into the more remote wilderness, or compelled to succumb to the superior power of the invader, in many instances being utterly exterminated. Still, north and south of that iron line the country resembles a desert; and the wild Indian roams as of yore, like the Arab of the East—his hand against every man, and every man’s hand against him.

claim to be lords of the soil, have been driven back into the more remote wilderness, or compelled to succumb to the superior power of the invader, in many instances being utterly exterminated. Still, north and south of that iron line the country resembles a desert; and the wild Indian roams as of yore, like the Arab of the East—his hand against every man, and every man’s hand against him.

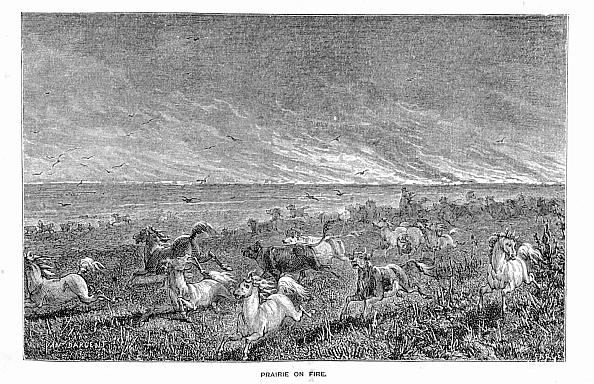

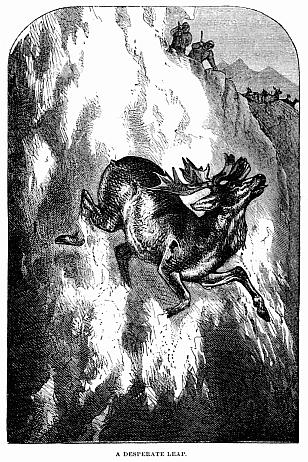

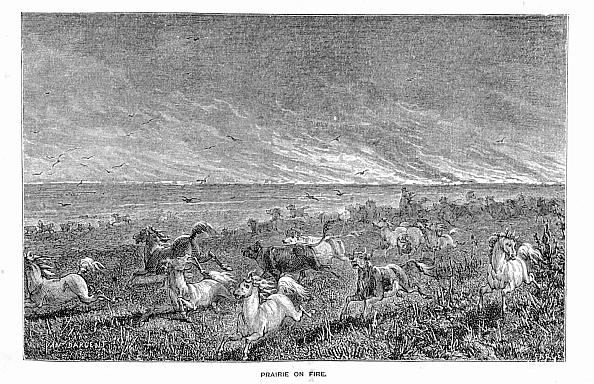

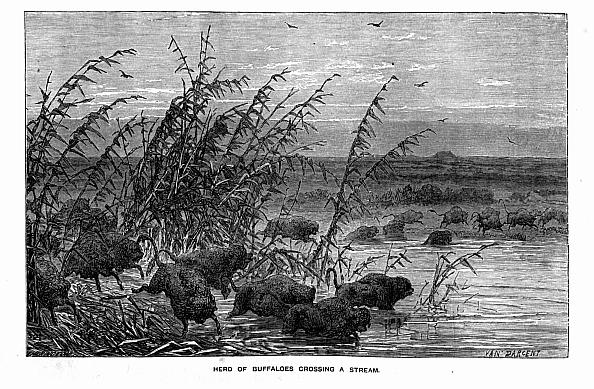

Among the dangers to which the traveller across the prairie is exposed, the most fearful is that of fire. The sky is bright overhead; the tall grass, which has already assumed a yellow tinge from the heat of summer, waves round him, affording abundant pasture to his steed. Suddenly his guides rise in their stirrups and look anxiously towards the horizon. He sees, perhaps, a white column of smoke rising in the clear air. It is so far-off that it seems it can but little concern them. The guides, however, think differently, and after a moment’s consultation point eagerly in the direction of some broad river, whose waters flow towards the Mississippi. “Onward! onward!” is the cry. They put spurs to their horses’ flanks, and gallop for their lives. Every instant the column of smoke increases in width, till it extends directly across the horizon. It grows denser and denser. Now above the tall grass flashes of bright light can be seen. The traveller almost fancies he can hear the crackling of the flames as they seize all combustible substances in their course. Now they surround a grove of aspens, and the fierce fire blazes up more brightly than ever towards the sky, over which hangs a dark canopy of smoke. Suddenly a distant tramp of feet is heard. The very ground trembles. A dark mass approaches—a phalanx of horns and streaming manes. It is a herd of buffaloes, turned by the fire purposely ignited by the Indians. The guides urge the travellers to increase their speed; for if overtaken by the maddened animals, they will be struck down and trampled to death. Happily they escape the surging herd which comes sweeping onward—thousands of dark forms pressed together, utterly regardless of the human beings who have so narrowly escaped them. The travellers gallop on till their eyes are gladdened by the  sight of the flowing waters of a river. They rush down the bank. Perchance the stream is too rapid or too deep to be forded. At the water’s edge they at length dismount, when the Indians, drawing forth flint and steel, set fire to the grass on the bank. The smoke well-nigh stifles them, but the flames pass on, clearing an open space; and now, crouching down to the water’s edge, they see the fearful conflagration rapidly approaching. The fire they have created meets the flames which have been raging far and wide across the region. And now the wind carries the smoke in dense masses over their heads; but their lives are saved—and at length they may venture to ride along the banks, over the still smouldering embers, till a ford is reached, and they may cross the river to where the grass still flourishes in rich luxuriance.

sight of the flowing waters of a river. They rush down the bank. Perchance the stream is too rapid or too deep to be forded. At the water’s edge they at length dismount, when the Indians, drawing forth flint and steel, set fire to the grass on the bank. The smoke well-nigh stifles them, but the flames pass on, clearing an open space; and now, crouching down to the water’s edge, they see the fearful conflagration rapidly approaching. The fire they have created meets the flames which have been raging far and wide across the region. And now the wind carries the smoke in dense masses over their heads; but their lives are saved—and at length they may venture to ride along the banks, over the still smouldering embers, till a ford is reached, and they may cross the river to where the grass still flourishes in rich luxuriance.

While, on one side of the stream, charred trees are seen rising out of the blackened ground, on the other all is green and smiling. These fearful prairie fires, by which thousands of acres of grass and numberless forests have been destroyed, are almost always caused by the thoughtless Indians, either for the sake of turning the herds of buffaloes towards the direction they desire them to take, or else for signals made as a sign to distant allies. Sometimes travellers have carelessly left a camp-fire still burning, when the wind has carried the blazing embers to some portion of the surrounding dry herbage, and a fearful conflagration has been the result.

Mr Paul Kane, the Canadian artist and traveller, mentions one which he witnessed from Fort Edmonton. The wind was blowing a perfect hurricane when the conflagration was seen sweeping over the prairie, across which they had passed but a few hours before. The night was intensely dark, adding effect to the brilliancy of the flames, and making the scene look truly terrific. So fiercely did the flames rage, that at one time it was feared the fire would cross the river to the side on which the fort is situated, in which case it and all within must have been destroyed. The inmates also had had many apprehensions for the safety of one of their party, from whom, with his Indians, Mr Kane had parted some time before, and who had not yet arrived. For three days they were uncertain of his fate, when at length their anxiety was relieved by his appearance. He had noticed the fire at a long distance, and had immediately started for the nearest bend in the river. This, by great exertion, he had reached in time to escape the flames, and had succeeded in crossing.

The Barren Plains in the Far West.

On the prairies of the east the eye ranges over a wide expanse of waving grass, everywhere like the sea. As, crossing the plains, we proceed west towards the vast range of the Rocky Mountains, the country gives evidence of the violent and irregular disturbances to which it has been subjected. Wild rocky ridges crop out from the sterile plains of sand; and for hundreds of miles around the country is desert, dry, and barren. Even the vegetation, such as it is, is of the same unattractive character. The ground here and there is covered with patches of the grey gramma grass, growing in little cork-screw curls; and there is a small furzy plant, the under sides of the leaves of which are covered with a white down, while occasionally small orange-coloured flowers are seen struggling into existence.

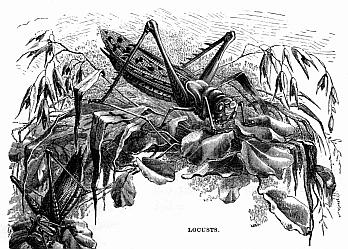

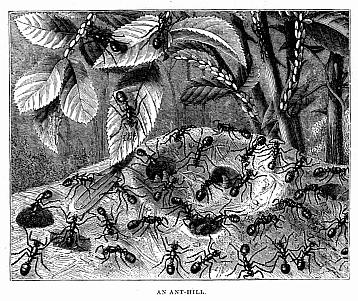

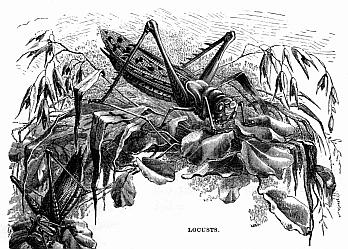

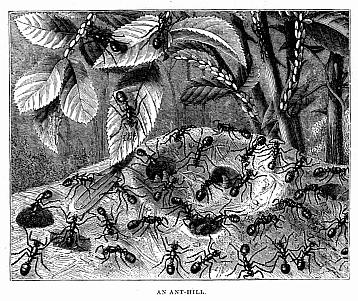

There are insects, however. Ants swarm in all directions, building cones a foot in height. Grasshoppers in myriads, with red wings and legs, fly through the air—the only bright objects in the landscape. Sometimes the reddish-brown cricket is seen. Even the Platte River, which flows through this region, partakes of its nature. It seems to consist of a saturated solution of sand: when a handful is taken up, a grey mud of silex remains in the palm. Dry as this gramma grass appears, it possesses nutritive qualities, as the animals which feed on it abundantly prove.

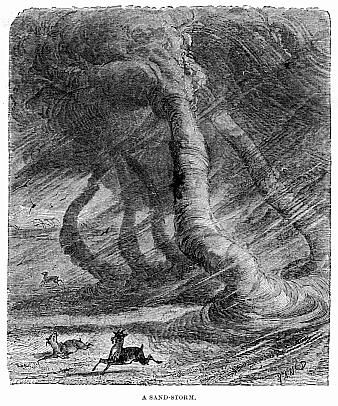

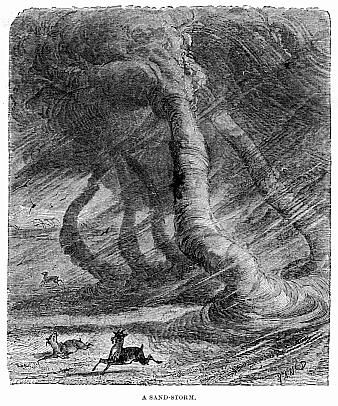

Storms break over these plains with tremendous fury: the thunder roars, the lightning which flashes from the clouds illumines earth and sky with a brightness surpassing the cloudless noon. Then again utter darkness covers the earth, when suddenly a column of light appears, like the trunk of some tall pine, as the electric fluid passes from the upper to the lower regions of the world. The next instant its blazing summit breaks into splinters on every side. Occasionally fearful hail-storms sweep over the plains; and at other times the air from the south comes heated, as from a furnace, drying up all moisture from the skin, and parching the traveller’s tongue with thirst.

Here and there are scattered pools of water containing large quantities of salts, soda, and potash, from drinking which numbers of cattle perish. The track of emigrants is strewn for many miles with bleaching heads, whole skeletons, and putrefying carcasses;—the result of the malady thus produced, in addition to heat and overdriving. Even the traveller suffers greatly, feeling as if he had swallowed a quantity of raw soda.

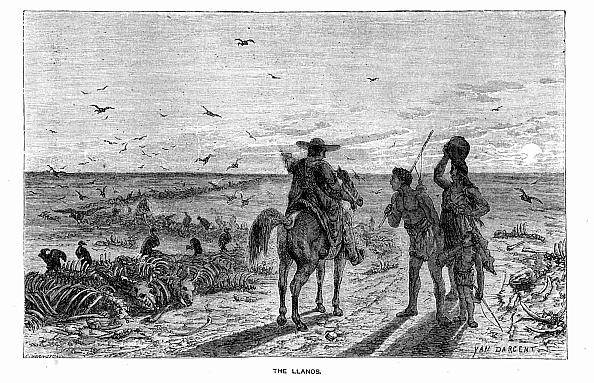

Yet often in this generally desert region, where the rivers wind their way through the plain, or wide pools of pure water mirror the blue sky, scenes of great beauty are presented. Nothing can surpass the rosy hues which tinge the heavens at sunrise. Here game of all sorts is found. The lakes swarm with mallards, ducks, and a variety of teal. Herds of antelopes cross the plain in all directions, and vast herds of buffalo darken the horizon as they sweep by in their migrations.

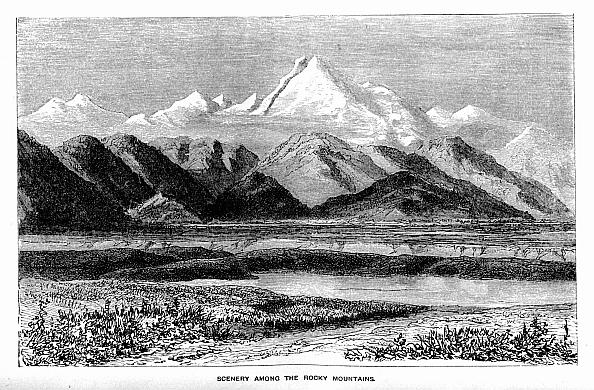

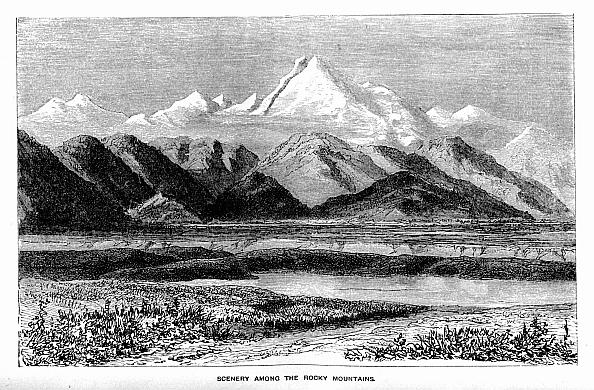

The Rocky Mountains.

At length a blue range, which might be taken for a rising vapour, appears in the western horizon. It is the first sight the traveller obtains of the long-looked-for Rocky Mountains; yet he has many a weary league to pass before he is among them, and dangers not a few before he can descend their western slopes. At length he finds himself amid masses of dark brown rocks, not a patch of green appearing; mountain heights rising westward, one beyond the other; and far-away, where he might suppose the plains were again to be found, still there rises before him a region of everlasting snow. For many days he may go on, now climbing, now descending, now flanking piles of rocks, and yet not till fully six days are passed is he able to say that he has crossed that mountain range. Indeed, the term “range” scarcely describes the system of the Rocky Mountains. It is, in fact, a chain, composed of numerous links, with vast plains rising amid them.

Parks.

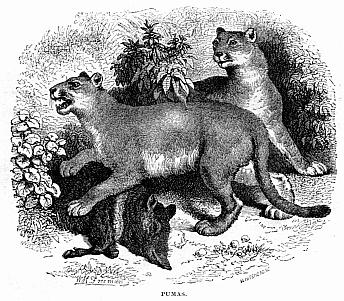

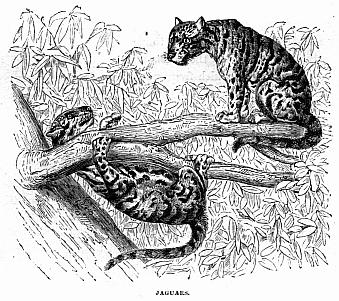

These ranges in several places thin out, as it were, leaving a large tract of level country completely embosomed in snowy ridges in the very heart of the system. These plains are known as “parks.” They are found throughout the range. Several of them are of vast extent,—the four principal ones forming the series called, in their order,  “North,” “Middle,” “South,” and “Saint Louis” Parks. Portions of them, thoroughly irrigated, remain beautifully green throughout the year, and herbage over the whole region is abundant. Sheltered from the blasts to which the lower plains are exposed, these parks enjoy an equable climate; and old hunters, who have camped in them for many seasons, describe life there as an earthly paradise. They abound in animals of all sorts. Elk, deer, and antelope feed on their rich grasses. Hither also the puma follows its prey, and there are several other creatures of the feline tribe. Bears, wolves, and foxes likewise range across them. In some of them herds of buffalo pass their lives; for, unlike their brethren of the plain, they are not migratory. It is doubtful whether or not they are of the same species, but they are said to be larger and fiercer.

“North,” “Middle,” “South,” and “Saint Louis” Parks. Portions of them, thoroughly irrigated, remain beautifully green throughout the year, and herbage over the whole region is abundant. Sheltered from the blasts to which the lower plains are exposed, these parks enjoy an equable climate; and old hunters, who have camped in them for many seasons, describe life there as an earthly paradise. They abound in animals of all sorts. Elk, deer, and antelope feed on their rich grasses. Hither also the puma follows its prey, and there are several other creatures of the feline tribe. Bears, wolves, and foxes likewise range across them. In some of them herds of buffalo pass their lives; for, unlike their brethren of the plain, they are not migratory. It is doubtful whether or not they are of the same species, but they are said to be larger and fiercer.

The appropriate designation of the Rocky Mountain-system is that of a chain. On crossing one of its basins or plateaux, the traveller finds himself within a link such as has just been described. A break in one of these links is called a “pass,” or “canon.” As he passes through this break he enters another link, belonging to another parallel either of a higher or lower series. In some of the minor plateaux between the snowy ridges no vegetation appears. Granite and sandstone rocks outcrop even in the general sandy level, rising bare and perpendicularly from 50 to 300 feet; as a late traveller describes it, “looking like a mere clean skeleton of the world.” Nothing is visible but pure rock on every side. Vast stones lie heaped up into pyramids, as if they had been rent from the sky. Cubical masses, each covering an acre of surface, and reaching to a perpendicular height of thirty or forty feet, suggest the buttresses of some gigantic palace, whose superstructure has crumbled away with the race of its Titanic builders. It is these regions especially which have given the mighty range the appropriate name of the Rocky Mountains.

The Sage Cock.

In some spots, the limitless wastes are covered by a scrubby plant known as mountain sage. It rises from a tough gnarled root in a number of spiral shoots, which finally form a single trunk, varying in circumference from six inches to two feet. The leaves are grey, with a strong offensive smell resembling true sage. In other places there appear mixed with it the equally scrubby but somewhat greener grease-wood—the two resinous shrubs affording the only fuel on which the emigrant can rely while following the Rocky Mountain trail.

These sage regions are the habitation of a magnificent bird—the Sage Cock. He may well be called the King of the grouse tribe. When stalking erect through the sage, he looks as large as a good-sized wild turkey—his average length being, indeed, about thirty-two inches, and that of the hen two feet. They differ somewhat, according to the season of the year. The prevailing colour is that of a yellowish-brown or warm grey, mottled with darker brown, shading from cinnamon to jet-black. The dark spots are laid on in a longitudinal series of crescents. The under parts are a light grey, sometimes almost pure white, barred with streaks of brown, or pied with black patches. In the elegance of his figure and fineness of his outlines he vies with the golden pheasant. His tail differs from that of the grouse family in general by coming to a point instead of opening like a fan. On each side of his neck he has a bare orange-coloured spot, and near it a downy epaulet. His call is a rapid “Cut, cut, cut!” followed by a hollow blowing sound. He has the partridge’s habit of drumming with his wings, while the hen-bird knows the trick of misleading the enemy from her young brood. He seldom rises from the ground, his occasional flights being low, short, and laboured. He runs with great speed, and in his favourite habitat dodges and skulks with rapidity, favoured by the resemblance of his colour to the natural tints of the scrub. Though sometimes called the Cock of the Plains, he never descends into the plains, being always found on the higher mountain regions.

When the snow begins to melt, the sage hen builds in the bush a nest of sticks and reeds artistically matted together, and lays from a dozen to twenty eggs, rather larger than those of the domestic fowl, of a tawny colour, irregularly marked with chocolate blotches on the larger end. When a brood is strong enough to travel, the parents lead their young into general society. They are excessively tame, or bold. Often they may be seen strutting between the gnarled trunk and ashen masses of foliage peculiar to the sage scrub, and paying no more attention to the traveller than would a barnyard drove of turkeys; the cocks now and then stopping to play the dandy before their more Quakerly little hens, inflating the little yellow pouches of skin on either side of their necks, till they globe out like the pouches of a pigeon.

Winter Scene among the Rocky Mountains.

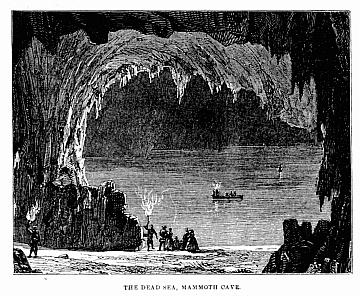

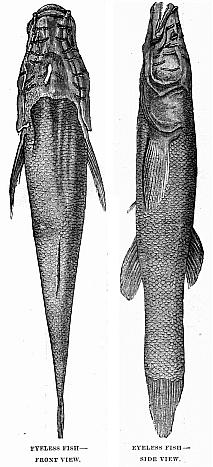

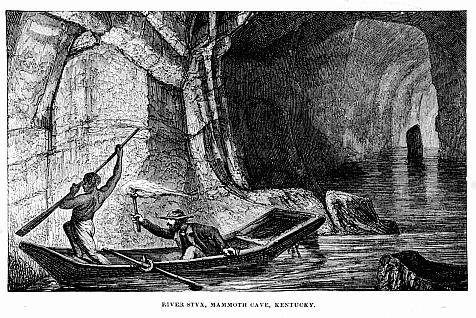

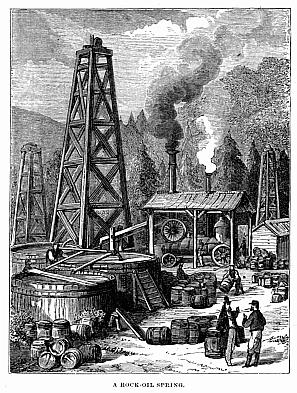

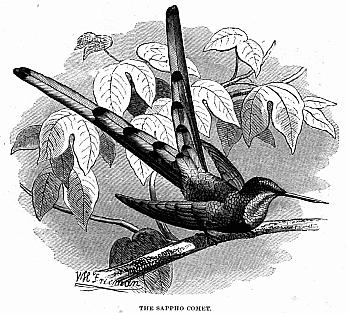

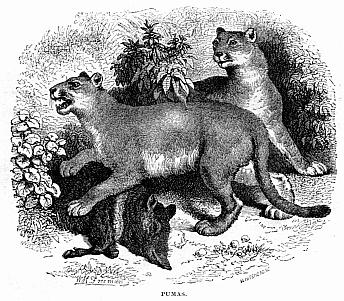

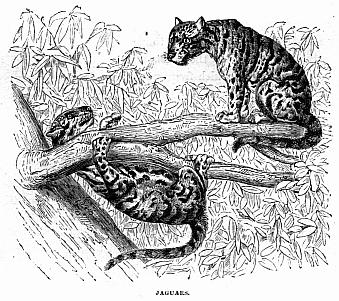

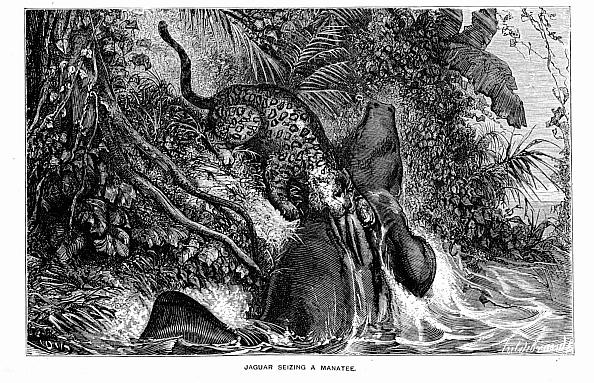

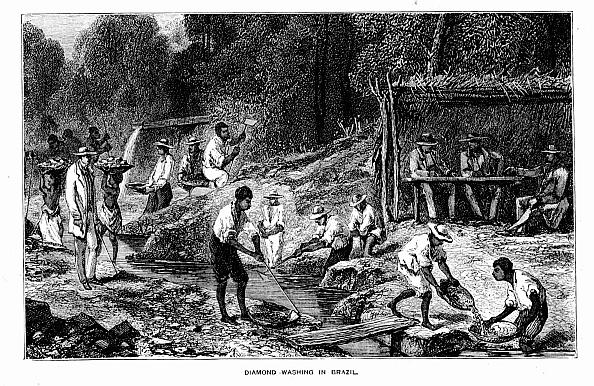

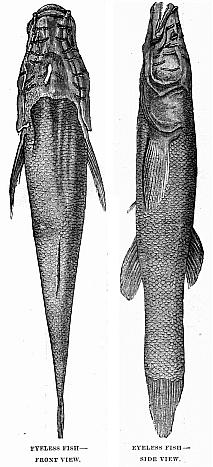

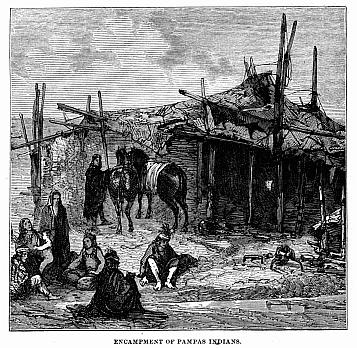

Descending the precipitous slopes of the Rocky Mountains on the west, we enter on a vast plain no less than 2000 miles in length, though comparatively narrow—the great basin of California and Oregon. Its greatest width, from the Sierra Nevada to the Rocky Mountains, is nearly 600 miles, but is generally much less. The largest lake found on it is 4200 feet above the level of the sea, and is connected with the Salt Lake of Utah. The mean elevation of the plain is about 6000 feet above the sea. A mountain-chain runs across it, and through it flows the large Colorado River, amidst gorges of the most picturesque magnificence.