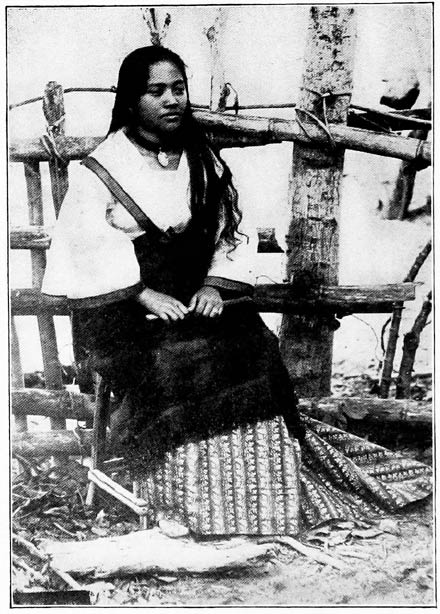

Marie Sampalit and her fiancee, Rolando Dimiguez, were

walking arm-in-arm along the sandy beach of Manila bay, just opposite

old Fort Malate, talking of their wedding day which had been postponed

because of the Filipino insurrection which was in progress.

The tide was out. A long waved line of sea-shells and drift-wood

marked the place to which it had risen the last time before it began to

recede. They were unconsciously following this line of ocean debris.

Occasionally Marie would stop to pick up a spotted shell which was more

pretty than the rest. Finally, when they had gotten as far north as the

semi-circular drive-way which extends around the southern and eastern

sides of the walled-city, or Old Manila, as it is called, and had begun

to veer toward it, Marie looked back and repeated a beautiful memory

gem taught to her by a good friar [12]when she was a pupil in one of

the parochial schools of Manila:

“E’en as the rise of the tide is told,

By drift-wood on the beach,

So can our pen mark on the page

How high our thoughts can reach.”

They turned directly east until they reached the low

stone-wall that prevents Manila bay from overflowing the city during

the periods of high tides. Dimiguez helped Marie to step upon it; then

they strolled eastward past the large stake which marked the place

where the Spaniards had shot Dr. Jose Rizal, the brainiest patriot ever

produced by the Malay race.

When they came to the spot, Marie stopped and told Dimiguez how she

had watched the shooting when it took place, and how bravely Rizal had

met his fate.

“If it hadn’t been for this outrage committed by the

Spaniards,” remarked Dimiguez, “this insurrection would not

have lasted these two years, and we would have been married before now;

but our people are determined [13]to seek revenge for his

death.”

Then they started on, changed their course to the northward, entered

the walled-city by the south gate, walked past the old Spanish arsenal,

and then passed out of the walled-city by the north gate. Here they

crossed the Pasig river on the old “Bridge of Spain” (the

large stone bridge near the mouth of the river, built over 300 years

ago) and entered the Escolta, the main business street of Manila. After

making their way slowly up the Escolta they meandered along San Miguel

street until they finally turned and walked a short distance down a

side street to a typical native shack, built of bamboo and thatched

with Nipa palms, happily tucked away beneath the overhanging limbs of a

large mango tree in a spacious yard,—the home of the

Sampalits.

Here Marie had been born just seventeen years before; in fact the

next day, April 7, would be her seventeenth birthday. When she was

born, her father instituted one of the accustomed Filipino dances which

last [14]from three to five days and nights, and at its

conclusion she had been christened “Maria,” subsequently

changed by force of habit to “Marie.”

Late that evening, while they were seated side-by-side on a bamboo

bench beside of her home, tapping the toes of their wooden-soled

slippers on the hard ground, and indulging in a wandering lovers’

conversation, Marie said to him (calling him affectionately by his

first name), “Rolando, when did you first decide to postpone our

wedding day?”

“Well, I’ll tell you how it was,” answered he,

meditatingly. “The thought of serving my country had been

lingering on my mind all last summer—in fact, ever since the

insurrection first broke out in the spring of 1896. You know I intended

coming down to see you last Christmas, but I couldn’t get away.

That night I walked the floor all night in our home at Malolos,

debating in my mind whether we had better get married in March, as we

had planned, or if it would not [15]be wiser and more manly for me

to go to war, take chances on getting back alive and postpone our

wedding day until after the war is over. Toward morning, I decided that

it was my duty to become a soldier; so I called my father and mother,

got an early breakfast, bade them goodby and started for Malabon, which

was Aguinaldo’s headquarters, and enlisted. He was glad to see

me. You know, he and I attended school together for one year at

Hongkong. Well, Aguinaldo at once commissioned me a spy and assigned me

to very important duty.”

“My God!” interrupted Marie, “you are not on that

duty now, are you, Rolando?”

Dimiguez arose. “Marie,” said he firmly, “I must

be off.”

“But won’t you tell me where you are going and what task

lies before you?” pleaded Marie, as she threw both arms about his

neck and began to sob, “I’ll never tell a living soul, so

help me God, but I must know!”

“A spy never tells his plans to anyone, Marie,” said

Dimiguez slowly. “He takes [16]his orders from his chief, plays

his part; and if he gets caught, he refuses to speak and dies without a

murmur, like a man. Good night, Marie, I must be off; duty lies before

me.”

Marie cried herself to sleep.

The next morning she started down town, as usual, for the market

place, with her bamboo basket filled with bananas, sitting on her head,

and a cigarette in her mouth. She had only gone a block when she met a

neighbor girl, one of her chums of equal years to her own, who was a

chamber-maid in the German consul’s home on San Miguel

Street.

Her friend looked excited. “Have you heard the awful news,

Marie?” said she.

“No!” exclaimed Marie, “What is it?”

“Why, Dimiguez was caught last night by Spanish guards inside

the yard of the governor-general’s summer palace up on the

Malacanan, just as he was slipping out of the palace itself. How he got

in there, nobody knows.” [17]

Marie dropped her basket. “Heavens!” gasped she,

“Did he do anything wrong?”

“They found in his pocket diagrams of the interior of the

palace, showing the entries to it, the room where the governor-general

sleeps, and many other things; also your picture. See here! the morning

paper gives a full account of it.”

Marie glanced at the head lines and then started on a vigorous run

for the building in which the Spanish military court was sitting.

Rushing in, past an armed guard, she began to plead for her

lover’s life. But he had already been tried, convicted and

sentenced to death by strangulation in the old chute at Cavite.

Dimiguez never moved a muscle when he saw Marie. Armed guards forced

her abruptly out of the building and ordered her to leave.

Inside of two hours, on the same day, April 7, the anniversary of

Marie’s birth, he was taken to the little town of Cavite, seven

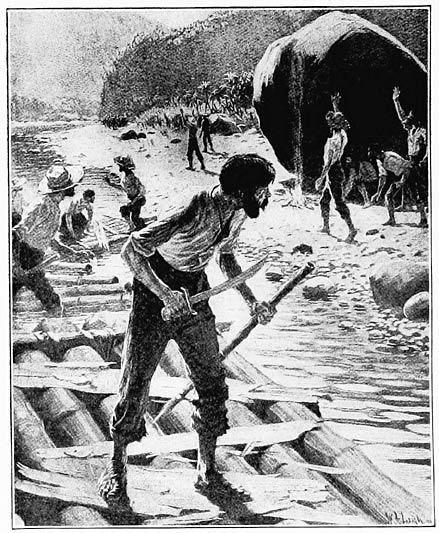

miles southwest of Manila, and was there placed in the lower end of a

long chute built [18]out into Manila Bay. This chute was just wide

enough for a man to enter. Its sides, top and bottom were all built of

heavy planks. The side planks lacked a few inches of connecting with

the top, although of course the side posts ran clear up and the top was

firmly bolted to them. The entrance to it was well elevated near the

docks. The lower end protruded into the bay, so that it was visible

about eighteen inches above the water during the period of low tide,

and submerged several feet during high tide.

Tides come in slowly at Cavite, each succeeding wave rising but a

trifle higher than the others, until the usual height is reached. Thus,

a prisoner placed in this chute, forced to the lower end and then

fastened securely during low tide, can look out over the side planks at

the hideous spectators, watch the tide as it begins to rise and see

slow death approaching. It was in this chute that Marie’s lover

met his death.

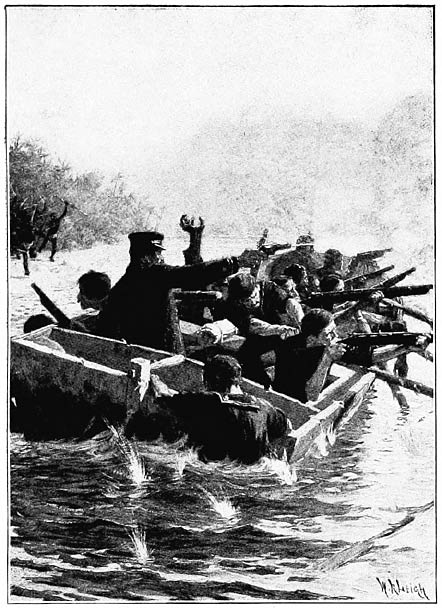

Marie saw the launch that carried him away as it left Manila. She

rushed down [19]to the Pasig river, loosened her little boat from

the tree to which it was tied, jumped in, seized the oars and started

in pursuit. The launch on which he was being carried had for its power

a gasoline engine, and, of course, it soon left her far behind. When

she first started, the swells caused by the launch rocked her little

canoe quite roughly and impeded her progress. As she approached the

mouth of the river, passed the monument of Magellan and came between

the walled-city on the southern bank and the docks on the northern

bank, a crowd of excited natives thronged the shore, and many of them

recognized her. She heard some one cry out, “Vive Marie!”

With might and main she strove forward.

The launch made its seven-mile run to Cavite; the victim was placed

in the chute; the tide had risen to the danger line; her lover, with

his head thrown back, had just begun to gurgle the salt water, when

Marie, in frantic agony, almost exhausted, rowed around the lower end

of the chute and came [20]near enough to the dying hero to be

recognized by him. Straining ever muscle to keep his head above the

water a second longer, he cried out in chocking tones that were

interrupted by the merciless sea which was rapidly filling his mouth,

“Goodby, Marie, God bless you. Avenge my death!”

Hush! At this moment another tidal wave engulfed the apex of the

chute. Not a sound could be heard save the slight flapping of the waves

against the pier, and the dismal chant of three priests, who stood on

the shore near by, and who had not been permitted to attend the young

spy before his death. Marie trembled; she dropped the oars; her eyes

fell; for a moment it seemed that her young heart stood still: then her

face flushed; the tears stopped flowing; anguish gave vent to

determined revenge; pent-up sorrows yielded to out-spoken threats; and

in tones sufficiently audible to be heard ashore, she cried,

“I’ll do it.”

The Spaniard knows no pity. If Marie were to have stepped ashore

immediately [21]after her lover’s strangulation, she might

have come to grief. It is strange that she escaped punishment for

having followed. She, therefore, rowed directly east and landed on the

beach of the bay, about four miles south of Manila, just west of the

little city of Paranaque.

From sheer exhaustion, she needed food; therefore, she walked

northward along the shore until she found a Mango tree heavily laden

with fruit. After eating a few luscious mangoes, she crept into a clump

of bamboo and had a good cry: tears so ease a woman’s soul.

From her position on the beach she could readily see the Spaniards

as they took her dead lover from the chute when the tide had lowered

toward evening. She saw them even strike his corpse, and she bit her

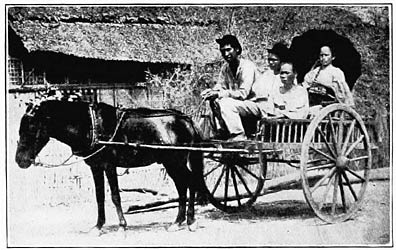

finger nails as she watched them place him in a rough wooden box and

haul him up through the streets of the village on an old two-wheeled

cart drawn by a caribou.

With the approach of sunset, things [22]grew strangely quiet. The

spring zephyr that had blown modestly during the day died away. There

was no longer even a dimple in the blue surface of Manila Bay. Not a

leaf was astir. It seemed to Marie that the only sound she could hear

was the the throbbing of her own heart. To her the whole world seemed

like an open sepulcher. Looking down she discovered that she was

unconsciously sitting on a flowery terrace and that all about her was

life. She pulled one of those exquisite white flowers with wide pink

veins, peculiar alone to the Philippines, and pressed it to her

lips.

The sun was just setting beyond Corregidor. The island’s long

shadows seemed to extend completely across the bay to her feet. As the

solar fires burned themselves out, the orange tint which they left

behind against the reddened sky reminded Marie of the night before,

when she and her lover had strolled along the shore of the bay about

three miles farther north; and as the sun slowly nodded its evening

farewell and buried [23]its face in the pillow of night, she

remembered how he, on the previous night, had called to her attention

the lingering glow of its fading beams. Before her lay the Spanish

fleet, it, too, casting shadows that first grew longer and longer and

then dimmer and dimmer until they in turn had died away in the spectral

phenomenon of night.

Marie’s thoughts turned toward home. What about her mother?

She walked back to her little boat, pushed it out into the bay, and,

stepping into it, sat down, took hold of the oars and started northward

near the beach. Just opposite Fort Malate, she swung westward, and,

passing outside of the break-water a mile from shore, she entered the

Pasig river and hurried homeward. When she arrived, about nine

o’clock, she found her mother on the verge of prostration; for

that very day, strange to say, Marie’s father, who was a colonel

in the Filipino infantry, had been killed at San Francisco del Monte,

six miles north-east of Manila, in a battle with Spanish troops.

[24]

“Don’t cry, mother,” expostulated Marie,

“from now on I intend to kill every foe of ours in these

islands!” [25]