Project Gutenberg's Two Gallant Sons of Devon, by Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Two Gallant Sons of Devon

A Tale of the Days of Queen Bess

Author: Harry Collingwood

Illustrator: Edward S. Hodgson

Release Date: February 10, 2008 [EBook #24565]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TWO GALLANT SONS OF DEVON ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"Two Gallant Sons of Devon"

Chapter One.

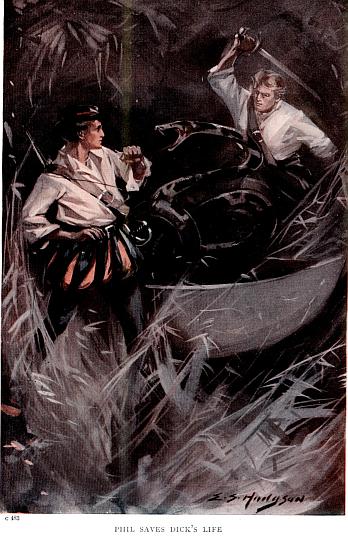

How Phil Stukely and Dick Chichester narrowly escaped drowning.

It was a little after seven o’clock on June 19 in the year of Our Lord 1577, and business was practically over for the day. The taverns and alehouses were, of course, still open, and would so remain for three or four hours to come, for the evening was then, as it is now, their most busy time; but nearly all the shops in Fore Street of the good town of Devonport were closed, one of the few exceptions being that of Master John Summers, “Apothecary, and Dealer in all sorts of Herbs and Simples”, as was announced by the sign which swung over the still open door of the little, low-browed establishment.

The shop was empty of customers for the moment, its only occupants being two persons, both of whom were employees of Master John Summers. One—the tall, thin, dark, dreamy-eyed individual behind the counter who was with much deliberation and care completing the preparation of a prescription—was Philip Stukely, the apothecary’s only assistant; while the other was one Colin Dunster, a pallid, raw-boned youth whose business it was to distribute the medicines to his master’s customers. He was slouching now, outside the counter, beside a basket three-parts full of bottles, each neatly enwrapped in white paper and inscribed with the name and address of the customer to whom it was to be delivered in due course. Apparently the package then in course of preparation would complete the tale of those to be delivered that night; for as Stukely tied the string and wrote the address in a clear, clerkly hand, the lad Dunster straightened himself up and laid a hand upon the basket, as though suddenly impatient to be gone.

At this moment another youth, with blue-grey eyes, curly, flaxen hair, tall, broad-chested, and with the limbs of a young Hercules, burst into the shop, taking at a stride the two steps which led down into it from the street, as he exclaimed:

“Heyday, Master Phil, how is this? Hast not yet finished compounding thy potions? My day’s work ended an hour and more ago; and the evening is a perfect one for a sail upon the Sound.”

“Ay, so ’tis, I’ll warrant,” answered Stukely, as he deposited the package in the basket. “There, Colin, lad,” he continued, “that is the last for to-night; and—listen, sirrah! See that thou mix not the parcels, as thou didst but a week agone, lest thou bring sundry of her most glorious Majesty’s lieges to an untimely end! There”—as the boy seized the basket and hurried out of the shop—“that completes my day’s work. Now I have but to put up the shutters and lock the door; and then, have with thee whither thou wilt. Help me with the shutters, Dick, there’s a good lad, so shall I be ready the sooner.”

Five minutes sufficed the two to put up the shutters, and for Stukely to wash his hands, discard his apron, change his coat, and lock up the shop; then the two somewhat oddly contrasted friends wended their way quickly down the narrow street on their way to the waterside.

As they go, let us take the opportunity to become better acquainted with them both, for, although they knew it not, they were taking their first steps on the road to many a strange and wild adventure, whither we who also love adventure propose to accompany them.

Philip Stukely, the elder of the two, aged twenty-three and a half years, tall, spare, sallow of complexion, with long, straight, black hair, and dark eyes—the precise colour of which no man precisely knew, for it seemed to change with his varying moods—was, as we have seen, by some strange freak of fortune, an apothecary’s assistant. But merely to say that he was an apothecary’s assistant very inadequately describes the man; for, in addition to that, he was both a poet and a painter in thought and feeling, if not in actual fact. He was also a voracious reader of everything that treated of adventure, from the story of the Flood, and Jonah’s memorable voyage, to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and everything else of a like character that he could lay hands upon. Altogether, he was a very strange fellow, who evidently thought deeply, and originally, and held many very remarkable opinions upon certain subjects.

This it was that made his friendship for and deep attachment to Dick Chichester, and Chichester’s equally deep attachment to him, so strange a thing; for the two had not a trait in common. To begin with, Chichester was much younger than Stukely, being just turned seventeen years of age, although this difference in age was much less apparent than usual, for while Stukely, in his more buoyant and expansive moments, seemed considerably younger than his years, Chichester might easily have been, and indeed often was, mistaken for a young man of twenty-one or twenty-two. While Stukely was spare of frame and sallow of complexion, Chichester possessed the frame, stature, and colouring of a young Viking, being already within a quarter of an inch of six feet two inches in height, although he had by no means done growing, broad in proportion, with eyes of steel blue, and a shock of curly hair which his friends would in these latter days have called auburn, while his enemies—if he had possessed any—would have tersely described it as “carrots”. In temperament, too, Chichester was the very antithesis of Stukely, for he was absolutely unimaginative and matter-of-fact. Perhaps his occupation may have had something to do with this; for he was apprenticed to a shipwright, and delighted in his work. He was also an orphan; his nearest relative being his uncle Michael Chichester, a merchant of Plymouth, who had adopted him upon the death of his parents, and with whom he now lived.

Not much was said as the strangely assorted pair strode along side by side on their way to the water, for both of them loved boats, and sailing, and all that pertained to the sea life, and both were equally eager to get afloat as quickly as possible, so as not to waste unnecessarily a moment of that glorious evening. At last, however, as Dick turned unexpectedly into a narrow side alley, Stukely pulled up short with:

“Hillo, Master Dick! whither away, my lad? This is not the way to the spot where our boat is moored.”

“No,” answered Dick, “it is not, I know. But we are not going to take our own boat to-night, Phil; we are going to take Gramfer Heard’s lugger. Gramfer is to Tavistock to-night; and he told me this morning that I might use the lugger whenever I pleased, if he did not want her himself. We’ll have something like a sail to-night, Phil, for there is enough wind blowing to just suit the lugger, while it and the sea would be rather too much for our own boat.”

So saying, Chichester led the way down the alley, and halted at a door in the wall, nearly at its farthest extremity. Then, drawing a key from his pocket, he unlocked the door, flung it open, and Stukely found himself looking in upon Gramfer Heard’s shipyard, the scene of Dick Chichester’s daily labours. He gazed, for a few seconds, with appreciative eyes at the forms of three goodly hulls in varying stages of progress, inhaled with keen enjoyment the mingled odours of pine chips and Stockholm tar, and then hurried after Dick, who was already busily engaged in unmooring a small skiff, in which to pull off to a handsome five-ton lugger-rigged boat that lay lightly straining at her moorings in the tideway.

A few minutes later they were aboard the lugger, busily engaged in loosing and setting the sails; and presently they were under way, having slipped their moorings and transferred them to the skiff, which they left behind to serve as a buoy to guide them to the moorings upon their return. The lugger was a beautiful boat, according to the idea of beauty that then prevailed, having been constructed by Mr George Heard—familiarly known as Gramfer Heard—shipbuilder of Devonport, and Dick Chichester’s master, as a kind of yacht, for his own especial use and enjoyment. She was a very roomy boat, being entirely open from stem to stern, and was conveniently rigged with two masts, the main and mizzen, upon which were set two standing lugs and a jib, the mizzen sheet being hauled out to the end of a bumpkin; consequently when once her sails were set she could easily be handled by one man.

Stukely, who was the master spirit, took the tiller, quite as a matter of course, while Dick was perfectly content to tend the jib and main sheets; and away they went down the Hamoaze, with the water buzzing and foaming from the boat’s lee bow and swirling giddily in her wake as she sped swiftly along under the impulse of a fresh westerly breeze, the full strength of which was however not yet felt, the lugger being under the lee of Mount Edgecumbe, beautiful then as it is to-day. But the prospect which delighted the eyes of the two friends—or of Stukely rather, for Dick Chichester somehow seemed almost entirely to lack the keen sense of beauty with which his friend was so bountifully endowed—was very different from that which greets the eye of the beholder to-day. Devonport and Stonehouse were mere villages; Mount Wise was farm land; where the citadel now stands was a trumpery fort which a modern gunboat would utterly destroy in half an hour; Drake’s island was fortified, it is true, but with a battery even more insignificant than the citadel fort; while the Hoe showed a bare half-dozen buildings, chief of which was the inn, afterwards re-named the Pelican Inn, in honour of Drake’s ship, famous as the spot behind which, eleven years later, Drake and Hawkins played their never-to-be-forgotten game of bowls.

As the boat slid out from under the lee of Drake’s island, however, and headed straight for the Eddystone, she gradually began to feel the full strength of the breeze, and her two occupants settled themselves down to enjoy thoroughly a good long evening’s sail, perhaps to be extended into the small hours of the next morning, if the conditions continued favourable. For there was nothing that these two more thoroughly enjoyed than a good tussle, in a well-found boat, against a strong breeze and a heavy sea; and they were like enough to have both to-night, so soon as they cleared the Sound and reached open water. In fact, although probably neither of them had thus far suspected it, both were strongly imbued with the spirit of born adventurers.

An hour’s sailing sufficed to carry them to seaward of Penlee Point, when they found that there was just wind and sea enough to make for perfect enjoyment, therefore instead of contenting themselves with a mere sail round the Eddystone and back they determined to make a night of it; and the sheets were accordingly hauled aft for a long stretch to windward, close-hauled, towards the chops of the Channel.

Away sped the boat to the southward and westward, careening gunwale-to, and sending the spray flying in such drenching showers over the weather bow, that presently the water rose above the bottom boards and splashed like a miniature sea in the lee bilge, compelling Dick to abandon the mainsheet to Stukely while he took a bucket and proceeded to bale. But the wind showed a disposition to freshen, careening the boat so steeply that, despite Stukely’s utmost care, the water began to slop in over the lee gunwale, as well as over the bows; and at length they decided to take a reef in the mainsail, for Dick had no fancy for spending the rest of the cruise in an ineffectual endeavour to free the boat of water that came in faster than he could throw it out. This was done, and the boat resumed her headlong rush to the southward, until by the time that the sun sank, red and angry, beneath the western wave, the land lay a mere film of grey along the northern board.

Then occurred a thing common enough in the tropics but much less usual in our more temperate climate; the wind suddenly dropped to a stark calm, and then, a few minutes later, came away in a terrific squall from about north-north-east.

So violent was the outfly that there was but one thing to do, namely, to keep the boat away dead before it; and away went the lugger, still heading to the southward and westward, but with the wind now dead aft instead of over the starboard bow. But they had scarcely been scudding five minutes when there occurred a sudden rending crack of timber, and the mainmast, weakened by an unsuspected flaw in the heart of it, snapped, about midway between the heel of it and the sheave, and went over the bows, broaching-to the lugger with the drag of the mainsail in the water, and nearly filling her as she came slowly round head to wind.

The friends were now in a situation of imminent peril, the squall raised a very awkward choppy sea with almost magical rapidity, and, more than half-full of water as the boat now was, she was liable to be swamped out of hand by some unlucky sea pouring in over her bows; the occupants, therefore, set to work with a will to bale her out, Stukely taking the bucket from Dick and handing him the baler instead. But it was both back-breaking and heartbreaking work; for, rendered heavy and sluggish by the large quantity of water in her, the boat frequently failed to rise to the lift of the seas, several of which poured in over her bows from time to time, filling her faster than she could be freed by the joint efforts of her crew; so that at length the unwelcome conviction forced itself upon the two friends that, unless something quite unforeseen happened, the boat must inevitably founder under them.

This conviction caused the toiling pair to cease from their labours for a moment and glance about them anxiously, in the hope that the twilight might reveal to them some craft to which they might signal for assistance. To their great relief, they perceived that there was indeed such a craft within a short two miles to the eastward of them; moreover she was outward-bound, and was heading in such a direction that she would probably pass within half a mile of the waterlogged lugger.

“Thanks be!” devoutly exclaimed Stukely, as his eyes fell upon her. “If we can but attract her attention before the boat founders, we shall escape, after all. Go on with your baling, Dick, while I wave my coat. The thing to do is to catch the eye of somebody aboard that ship and make it understood that we are in distress; then, since we can both swim, it will not greatly matter if the lugger should go down before yonder ship reaches us.”

Dick obediently did as he was told, while Stukely, whipping off his coat, sprang upon the mast thwart and, with his left arm flung round the splintered stump to steady himself, proceeded to wave his coat energetically. Luckily for the pair in distress, they were to the westward of the approaching ship, with the evening sky, in which still lingered a pale primrose glow, behind them, and against this background their figures and that of the boat stood out black as silhouettes cut in ebony. It is possible that, even with this advantage, they might have escaped notice, had not Phil thought of waving his coat; but the figure of him standing there, apparently upon nothing—for it was only now and then that a small portion of the hull became visible—waving frantically something big enough to show up strongly, soon attracted attention on board the approaching ship, and Stukely had scarcely been ten minutes engaged on his waving operations when he had the gratification of seeing a flag float out over the rail and go soaring up to the main truck, while the stranger’s helm was slightly shifted and she swerved perceptibly toward them.

“Glory be! they have seen us, and are bearing away for us, so it matters little now whether the lugger sinks or swims,” exclaimed Stukely, as he sprang off the thwart and resumed his task of baling with renewed zest. “Nevertheless,” he continued, “it will be well to keep her afloat as long as we may, since she affords a bigger mark to steer for than would the heads of us two afloat upon the darkling water.”

The stranger—a tall and stately ship of some two hundred and forty tons measurement—was now close aboard of the dismasted lugger; and well was it for the occupants of the latter that such was the case; for as the ship cleverly rounded-to, with her topsails lowered, alongside and to windward of the boat, so near was the latter to foundering that the bow wave of the rescuing craft completed the disaster by surging in over the gunwale in sufficient volume to fill her; and down she went, at the precise moment when some half a dozen ropes, hurled by the sailors above, came whirling down about the shoulders of Dick and Stukely.

“Haul away!” shouted the two, with one accord, each grasping the rope’s end that came first to hand as they felt the lugger sinking and themselves going down with her; and the next moment they were dragged, dripping wet, up the lee side of the ship and in over her high bulwarks.

“Better late than never; iss, fegs!” exclaimed a stout, burly man of middle height, clad in a crimson doublet of slashed silk, and trunk hose, with a crimson velvet cap, in front of which was stuck a feather of the same hue, secured by a gold brooch, set jauntily upon his head. “But by my faith, my masters, we were only just in time. Mr Bascomb, put up your helm, and hoist away your topsails again. And now, gentles both, who be ye; and how came ye to be in so awkward a scrape as that from which we have just rescued ye?”

This was evidently the captain of the ship; so Stukely, taking the lead as usual, explained in a few brief words the particulars of their mishap, thanked the unknown for his kindness in taking the trouble to pick them up, and concluded by expressing the hope that the individual to whom he was speaking would have the great goodness to stand inshore and land them on the nearest point that he could conveniently fetch.

The captain—for such he proved to be, introducing himself as John Marshall, captain of the good ship Adventure of Topsham, westward bound to the Indies in quest of Spanish booty—shook his head good-naturedly but firmly.

“Nay, friend, that I cannot and will not do, for here have we spent the whole of last night and to-day working down channel as far as this, and now that we have at last caught a fair slant of wind I will make the most thereof, not risking the loss of it to land any man, yea, even though he were my own brother! The utmost that I can promise is, that if we should fall in with a coaster, or other ship, bound up-channel, or should sight a fishing boat, I will delay my voyage just long enough to put ye on board, but not a minute longer. And if so be we do not encounter another craft, you will e’en both have to join us, for we have here no room for idlers. And now, hie you both away into the cabin, and take off your wet clothes; Mr Bascomb, the master, will furnish you with dry clothing from the slop chest—though I misdoubt me,” he continued, running his eye dubiously over Chichester’s stalwart frame, “whether he will find any ample enough to clothe your friend withal. And when ye have changed, sup with us in the cabin, and we will talk further together.”

Marshall then beckoned to Bascomb, and gave the latter instructions to open the slop chest and do his best to provide the newcomers with dry clothes; whereupon the master, in turn, beckoned to Philip and Dick to follow him below, where in due time both were provided with a change of clothing, the resources of the slop chest happily proving fully equal to the strain upon its resources imposed by Chichester’s bulky proportions. The change was effected in good time to allow the two friends to join the occupants of the poop cabin at supper, where Captain Marshall made them duly acquainted with his fellow adventurers. These were five in number, consisting respectively of Mr George Lumley and Mr Thomas Winter, Marshall’s lieutenants, Mr Walter Dyer and Mr Edmund Harvey, gentlemen adventurers who, with Marshall, had provided the wherewithal for the fitting out of the expedition, and Mr William Bascomb, the master aforesaid. They were all fellow Devonians, a genial and hearty company, in the best of good spirits at the prospect of stirring times before them, with the chance of returning home made men. It is true that—not to put too fine a point upon it—they were pirates, of a sort; but so were Grenvile, Drake, Hawkins, and the rest of their illustrious contemporaries; and piracy was at that time regarded as a quite honourable profession—provided that the piracies were perpetrated solely against the hated Spaniard.

It was by this time dark enough to render necessary the lighting of the great cabin lamp which swung in the skylight; and the apartment, with its long table draped with snowy napery and abundantly furnished with smoking viands flanked with great flagons of foaming ale, presented a particularly cosy and inviting appearance as Dick and Phil, having been introduced in due form to the others, took their seats; the more so, perhaps, from the fact that both of them, having been too eager for their sail to wait for a meal at the conclusion of their day’s labours, had tasted neither bite nor sup since midday, and were now each in possession of a truly voracious appetite. Then, the conversation as the meal progressed—the wonderful, almost incredible, stories of past adventure related by Marshall and Bascomb, both of whom had already once visited the Indies, and the confidence with which all anticipated their return to England laden with wealth unimaginable—exercised an almost irresistible fascination over the two newcomers, one at least of whom—Philip Stukely to wit—began to feel, before the meal was over, that he cared not a jot though he should be compelled by force of circumstances to join those daredevil adventurers who made it clearly understood that, so far as the outside world was concerned, they intended to be a law unto themselves. Marshall’s and Bascomb’s talk, especially, of cloudless skies of richest blue, out of which the sun darted his flaming rays by day, and in which the stars blazed like jewels at night; of tranquil seas of sapphire in which creatures of strange forms and brilliant hues disported themselves; of tropic shores, coral fringed and clothed with graceful feathery palms backed by noble forest trees of precious woods, made glorious by flowers of every conceivable hue and shape, amid which hovered birds of such gorgeous plumage that they gleamed and shone in the sun like living gems; of rich and luscious fruits to be had for the mere trouble of plucking; of fireflies spangling the velvet darkness with their fairy lamps; and of the gentle Indians who—at least when not brought under the malign influence of the cruel Spaniard—regarded white men as gods; all these appealed with singular force and fascination to Stukely, who sat listening breathlessly and with glowing eyes to everything that the two sailors said about these wonders.

For, singularly enough, although the man had never until now been out of sight of English soil, and although he had never read about them, all these things seemed strangely familiar to him. Times without number, as he had sat meditating over the fire on a winter’s night, or had sprawled among the hay or upon the sandy beach on a summer evening, had visions of just such lands and just such enchanting scenes as Marshall and Bascomb described come floating to him like vague and distant but cherished memories.

He awoke, as from a delightful dream, when, the meal being finished, Marshall arose from his chair and invited his guests to accompany him out on deck. It was quite dark when they emerged from the cabin; so dark indeed that for a moment, their eyes being still dazzled by the bright light of the cabin lamp, they groped their way like blind men, and were fain to stand still, clinging to whatsoever their hands happened to find. Then, their sight coming to them again, they followed Marshall up the poop ladder, and stood, staring out upon a night of blusterous wind and faintly phosphorescent, foam-capped sea; of flying clouds amid which the stars twinkled mistily and vanished, to re-appear presently with the tall spars and swelling canvas of the ship swaying dizzily and black among them; a night full of unaccustomed sounds of creaking and groaning timbers, of the splashing and roaring of water under the ship’s bows, along her bends, and about her rudder; of strange sighings and moanings aloft; and of the low murmur of men’s voices as the watch clustered under the shelter of the towering forecastle, discussing, mayhap, like their superiors aft, the prospects of the voyage.

The Captain peered about him on either side of the ship, anon stooping to send his glances forward into the darkness beyond the heaving bows; then he hailed the lookouts upon the forecastle, demanding in sharp, imperative tones whether there were sail of any kind in sight. The answer was in the negative.

“Well, my masters,” said he, turning to Stukely and Chichester, “you see how it is; there is nothing in sight; and every mile that we travel lessens your chance of our falling in with anything into which we can transfer you. If this good breeze holds—as I trust in God that it will—we shall be off Falmouth shortly after midnight, but much too far out to render it at all likely that we shall sight any of its fishing craft; and, once to the westward of Falmouth, your last chance of getting ashore will be gone. Now, what say ye? Will ye, without more ado, up and join us? I talked the matter over with my partners while you were changing your duds before supper, and I can find room in the ship for both of you. We have no surgeon with us, so that berth will fit you finely, Mr Stukely; while, as for you, my young son of Anak,” turning to Chichester, “a lad of your thews and sinews can always earn his keep aboard ship. But I can offer ye something better than the berth of ship’s boy; we have but one carpenter among us, and I will gladly take you on with the rating of carpenter’s mate, if that will suit ye. Iss, fegs, that I will! Now, what say ye? Shall us call it a bargain, and have done wi’ it?”

“So far as I am concerned, you certainly may—if Dick will join, too,” answered Stukely. “I will not let him go ashore alone to answer for the loss of the boat; for the accident which caused the plight in which you found us was at least as much my fault as his. But I do not believe that we are going to have the chance to get ashore, therefore—what say you, Dick, shall we accept Captain Marshall’s very generous offer, and so settle the matter?”

“I am not thinking of the boat—Gramfer Heard is rich enough to bear the loss of her without feeling it—but it is my uncle that I’m troubling about. I am afraid that he will be greatly distressed at my sudden and unaccountable disappearance,” answered Dick.

“True,” assented Stukely; “doubtless he will. But what about thy aunt, Dick? Will not she rejoice that your worthy uncle’s exchequer is relieved of the cost of your maintenance? I have heard that she keeps a tight hold upon her husband’s purse strings; and it has been whispered that she begrudges every tester that the good man spends upon thee. Believe me, she will soon find words to console him for thy loss.”

“That is true, Phil,” returned Dick, with a sigh. “She would sit and watch me eating, like any cat, so that often enough, for very shame, I rose from the table still hungry. But my uncle is not a rich man, and he has three maidens of his own to feed and clothe, so that perhaps it may be just as well that I should take advantage of this opportunity to relieve him of the cost of an extra mouth to fill, and an extra body to cover. But what of Master Summers, Phil? How will he manage without thee?”

“Master Summers must e’en get another dispenser,” answered Stukely, with a shrug. “I trow there are plenty of them to be had. But I would that I had my books with me. Not having them, however, I must contrive as best I can to do without them.”

“Then,” cut in the Captain, somewhat impatiently, “may I understand that you are willing to join us? You will never have another such an opportunity to make your fortunes.”

Phil looked enquiringly at Dick, who, after a moment’s hesitation, nodded; whereupon Stukely, speaking for both, announced that they were ready to sign the agreement whenever it might be convenient for them to do so.

“No time like the present,” asserted Marshall. “You may as well do it now.” And, leading the way into the cabin, he produced a parchment setting forth the articles of agreement, which he read over to them. The two friends then took the pen and inscribed their names at the foot of the document, thus forging the last link in a chain which was to drag them into a series of adventures of so extraordinary a character that it is doubtful whether even Stukely, with all his inborn love of adventure, would have been willing to proceed, could he but have foreseen what awaited him in the future.

Chapter Two.

How the “Adventure” fought and took the “Santa Clara” off Barbados.

And now, at the very outset, almost before the ink of their signatures had fairly dried, a hitch threatened to occur over the matter of berthing the two new recruits. For, Stukely being entered as surgeon, Marshall offered him, as a matter of course, a stateroom aft, while Chichester, being shipped merely as carpenter’s mate, was directed to go forward and establish himself in the house abaft the fore hatch, in which were lodged the other petty officers. Dick, to do him justice, was willing enough to accept the lodging assigned to him; but it was Stukely who objected to being separated from his friend. He insisted that Dick, being a gentleman, although merely a shipwright’s apprentice, was as much entitled to a cabin aft as he was himself; and when the unreasonableness of this demand was pointed out to him he proposed that he also should be permitted to berth forward. But neither could this be managed, for there was only one spare bunk available in the petty officers’ house, namely that assigned to Chichester; therefore the Captain’s arrangement had perforce to stand, after all.

“Very well,” said Stukely, when at last he was convinced that what he desired was impossible; “let be; you and I, Dick, can at least walk and talk together when we are off duty. And—listen, lad—in an adventure such as this is like to be, many changes are both possible and probable; my advice therefore is that you make friends with Master Bascomb and get him to instruct you in the science of navigation, so that you may be fully qualified to act as pilot, should the occasion arise. You will be no worse a pilot because you happen to be a good shipwright; and your proper place is aft among the gentles, where I hope to see thee soon.”

“That’s as may be,” answered Dick, with a laugh. “Nevertheless thy advice is good, and I will take it.”

“And I, for my part, will give friend Bascomb a hint that he is to teach thee all that thou art willing to learn,” cut in Marshall. “For the doctor is right; many changes are like to occur among us before we see old England’s shores again; and I shall be glad to know that I have one aboard who is fit to take Bascomb’s place, should aught untoward befall him. And now, my masters both, away to your quarters and get a good night’s rest. You, doctor, will of course sleep in all night, and be on duty all day; but as for you, Chichester, I will put you in a watch to-morrow morning.”

The next day saw the good ship Adventure clear of the Channel; for the breeze which had interfered so unceremoniously with the fortunes of Dick and his friend held all through the night and contrary to expectation increased, at the same time hauling gradually round from the north-east, to the great joy of the Captain and Bascomb, who at eight o’clock in the morning shaped a course for the Azores, where it was intended to wood and water the ship, and lay in a goodly stock of fruit and vegetables to stave off the scurvy among the crew for as long a time as might be.

The weather continued fine and the wind fair for four days, during which the ship, with squared yards, made excellent progress; then came a strong breeze from the westward which drove them nearly a hundred miles out of their course. This, in its turn, was followed by light winds and fair weather, with a sun so hot that the pitch began to melt and bubble out of the deck seams, so that the mariners, who had hitherto been going about their duty barefoot, were fain to don shoes to save their feet from being blistered. Finally, after a voyage of twenty-four days, they came to the Azores, where they remained four days, filling up their fresh water, replenishing their stock of wood, and taking in a bounteous supply of vegetables and fruit, especially “limmons”—as Marshall called them—for the prevention of scurvy.

Then, greatly refreshed by their short sojourn, and by the entire change of diet which they enjoyed during their stay, they again set sail, and, making their way to the southward and westward, at length fell in with that beneficent wind which blows permanently from the north-east, and which in after-years came to be known as the Trade Wind. With this blowing steadily behind them day after day, they squared away for the island of Barbados, where, if there happened to be no Spaniards to interfere with them, it was Marshall’s intention to lay up for a while, to give his men time to recruit their health, and also to careen the ship and clear her of weed before beginning his great foray along the Spanish Main.

And in due time—on the fiftieth day from that on which Dick and Phil were rescued from the sinking boat, to be precise—with the rising of the sun a faint blue blur, wedge-shaped, with the sharp edge pointing toward the south, appeared upon the horizon, straight ahead, and the joyous shout of “Land ho!” burst from the lips of the man stationed as lookout upon the lofty forecastle. Yes; there it was; land, unmistakably, sharp and clear-cut, with a slate-blue cloud—the only cloud in the sky—hovering over it, from the breast of which vivid lightning flashed for a space, until, having emptied itself of electricity, the cloud-pall passed away, leaving the island refreshed by the shower that had accompanied the storm, gradually to change from soft blue to a vivid green as the Adventure, with widespread pinions, rushed toward it before the favouring breeze. And with the cry of the lookout the ship at once awoke to joyous life; the watch below, ay, and even the sick, sprang from their hammocks and rushed—or crawled, as the case might be—on deck to feast their eyes once more upon the sight of a bit of solid earth, green with verdure, and promising all manner of delights to those who had been pent up for so long between wooden bulwarks, and whose eyes had for so many weary days gazed upon naught but sea and sky. It is true that Stukely had never tired of gazing upon that same sea and sky; with the spirit of the artist that dwelt within him he had been able to see ever-changing beauty where others had beheld only monotony; but to the crew at large that wedge of land, growing in bulk and importance as the ship rushed toward it, was more beautiful than the most glorious sunset that had ever presented itself to their wondering eyes.

“What island is that?” demanded Stukely of the master, who was standing halfway up the poop ladder, gazing at the distant land under the foot of the foresail.

“It should be Barbados, unless I am a long way out of my reckoning. But there is no fear of that; besides, I know the look and shape of the place; I have been there before; and it was just so that it looked when I got my last glimpse of it. Yes, that is Barbados; and, please God, we shall all sleep ashore to-night. There is good, safe anchorage round on the other side of that low point, with a snug creek into which the ship, with but a little lightening, may be taken and careened. I pray that there may be no Spaniards there, for there is no better place on God’s good earth for landing and recruiting a scurvy-ridden crew.”

“Are there any Indians on the island?” asked Stukely.

“There may be; I cannot say; but I never saw any,” answered Bascomb. “And if there be,” he continued, “they are not likely to interfere with us. Such Indians as I have met have ever been very shy of showing themselves to the whites, and always keep out of their way, if they can. That is to say, they do so among the islands. On the Main, where they have been cruelly ill-treated and enslaved by the Spaniard, they are very different, being cruel and treacherous, and ever ready to attack the whites and destroy them with the poisoned darts which they discharge from blowpipes, and their poisoned arrows. But, have no fear; the Indians on yonder island—if indeed there be any—will be of a very different temper, and quite gentle.”

“Indeed, then, I pray that they may be,” returned Stukely. “For though we have been marvellously fortunate, thus far, in the matter of sickness, there are still too many men in the sick bay for my liking; and we ought to have every one of them sound and fit for duty again before we go on with our great adventure. But, look now, what comes yonder? Surely that is a ship’s canvas just beginning to show over the land there near the southern end of the island?”

Bascomb shaded his eyes with his hand and looked toward where Stukely pointed. The island was by this time about five miles distant, and the colours of the vegetation were showing up clearly in the brilliant light of the tropic day. But beyond it again, and showing over the tree-tops, there was a faint grey film that was evidently moving, sliding along, as it were, toward the low point. Even as they looked the filmy grey object suddenly became a strong white and assumed a definite form as it emerged from the shadow of a cloud, revealing itself as the upper canvas of a large ship which had either just got under way from the anchorage on the lee side of the point, or—and this seemed to be the more likely of the two—was working up to windward in the smooth water, having sighted the island on her way to the eastward.

“Iss, sure,” agreed Bascomb, relapsing into the Devonshire dialect in his excitement; “that’s a ship, sure enough, moreover a Spaniard at that, most likely; and, if so, we shall have a fight on our hands afore long. Do ’e see thicky ship t’other side of the island, yonder, Cap’n Marshall?” he continued, addressing himself to the Captain, who was on the poop, conversing earnestly with Messrs Dyer and Harvey, his partners in the adventure.

“Ship, sayest thou? Where then?” demanded Marshall, breaking off his conversation and running forward to the head of the poop ladder.

“Why, there a be, with the sails o’ mun just showing over the low point,” answered the master. “She’ll be clear of the land in another minute or two; and then they’ll see us as clearly as we see them. She’s a Spaniard, to my thinking, Cap’n; and there may be fine pickings aboard of her—if her don’t turn and run so soon’s she sees us.”

“She’ll not do that, Master Bascomb; she be a bigger ship nor we. Besides, how’s she to know we baint a Spaniard like herself, if we don’t tell her. We’ll clear the decks and make all ready before we show our flag, gentles; and see what comes of it. Let the mariners get to work at once, Mr Bascomb.”

The excitement aroused by the appearance of land on the horizon, after so many weary weeks of gazing upon sea and sky only, was intensified tenfold when the strange sail—the first they had seen since leaving the Azores—was discovered; and when it was further understood that the chances were in favour of her proving to be a Spaniard, the preparations for a possible fight were entered upon with the utmost eagerness and alacrity. Fortunately, there was not very much that needed to be done; for Marshall, rendered wise by past experience, had consistently made a point of always having the decks kept clear of unnecessary lumber of every kind; but the bulwarks were strengthened and raised, for the purpose of affording the crew as much protection as possible from the enemy’s musketry fire; the lower yards were fitted with chain slings, so that the risk of their being shot away, and the ship thus disabled at a critical moment, might be minimised as much as possible; parties of musketrymen were sent aloft into the round tops, with instructions to hamper the enemy as much as possible by their fire, especially by picking off the helmsman and the officers; the powder room was opened, and ammunition sent on deck for the culverins, sakers, and swivels, all of which were loaded; and the men, having armed themselves with cutlass, pistol, bow, and pike, stripped to their waists, bound handkerchiefs round their heads, and took up their several stations by the guns, or at the halliards and sheets. Marshall took command of the ship as a whole; while Lumley and Winter, his lieutenants, assumed charge of the poop and forecastle respectively, Bascomb, the master, taking charge of the main deck. Stukely, with his knives, saws, and bandages, established himself in the cockpit; and Dick Chichester, who had contrived to gain the reputation of being the best helmsman in the ship, was ordered to the tiller.

Meanwhile, the strange ship, having cleared the land, revealed herself as a craft of probably quite a hundred tons bigger than the Adventure, and carrying four more pieces of great ordnance than the latter. But this fact by no means dismayed the English; for the stranger was what was called a race ship, and was nearly twice as long as the Adventure; Marshall therefore confidently reckoned that, should the two vessels come to blows, the superior nimbleness of his own ship would more than counterbalance the advantage conferred upon the other by her greater weight of metal. The stranger, when she cleared the land, was close-hauled on the larboard tack, heading about south-south-east, and it was judged, from her position relative to the land, that she had not actually touched at the island, but had simply availed herself of its presence to gain a few miles by turning to windward in the smooth water under its lee. The discovery of the presence of the English ship did not appear to have caused any uneasiness to her commander, for he did not deviate a hairbreadth from his course, but stood on, maintaining his luff, the only indication that he had observed the Adventure at all being the display of the yellow flag of Spain, which he had hoisted to the head of his ensign staff within five minutes of the time when he cleared the island. Probably he imagined that the Adventure was also Spanish.

The English, on their part, took no notice of the stranger, except by gradually edging down toward her, until their preparations for battle were complete; then indeed they hoisted the white flag bearing the crimson cross of Saint George, and hauled their wind sufficiently to enable them to intercept the Spaniard. At this invitation to battle symptoms of alarm and indecision began to manifest themselves on board the latter, for she first put up her helm and kept away, as though about to turn tail and run, but presently came to the wind again and tacked, heading now to the northward.

“Over with the helm, and steer for the northern end of the island,” cried Marshall to Dick; “that ought to enable us to intercept him. Thank God, he means to fight instead of running, and the matter will the sooner be settled. Look to that, now; he is stripping for battle, for in comes all his light canvas, and up goes his mainsail. The man who commands that ship is a right valiant cavalier, and will put up a good fight; therefore, let no man put match to culverin or finger to trigger until I give the word. Now, let the waits play up ‘The brave men of Devon!’”

Therewith the waits, five in number, stationed on the main deck, between the poop and the mainmast, struck up that favourite and inspiring air with such good effect that before two minutes had passed every man and boy in the ship was singing the song at the top of his voice, and feeling quite ready to fight all the Spaniards who might care to come against them.

A quarter of an hour later the two ships had closed to within musket shot of each other, the Adventure having the weather gage, when crash came the whole of the Spaniard’s broadside, great guns and small; but so bad was the aim that every shot flew high overhead, and not so much as a rope was touched.

“Good!” ejaculated Marshall. “Now, steersman, up with your helm, and shave past as close under his stern as you can without touching. Starboard gunners, be ready to pour your shot into his stern as we pass! Musketrymen and archers, pick off as many men as you can see, and especially the helmsman! Sail trimmers, to your stations, and be ready to go about!”

Two minutes later the Adventure slid square athwart the towering, gilt-bedizened stern of the Spaniard, and one after another, as they were brought to bear, her ordnance belched forth their charges of round and canister, smashing the Spanish gingerbread work to splinters, shivering every pane of glass in the stern windows, and sweeping the decks of the stranger from end to end, the deadly nature of the discharge being evidenced by the outburst of shrieks which instantly followed aboard the stranger.

“Well done, gallants!” cried Marshall, waving his sword. “Now, ready about, and larboard gunners stand by to repeat the dose. Down helm, steersman, and let her come round! Raise fore tack and sheet! Ha! she is falling off, and means to give us her larboard broadside while we are in stays—if she can. Topmen, do your best, now, and pick me off her helmsman before it is too late. Well done!”—as the Spaniard began to come ponderously to the wind again, showing that her helmsman was down—“Let the man who did that come to me by and by, and he shall have a noble for that good shot. Swing the mainyard! Musketrymen, clear the enemy’s tops of archers, and shoot down any that may attempt to take their places! Trim aft the head sheets! Swing the foreyard! Starboard gunners, reload your ordnance! We will try that trick again if they will but give us the chance. Now, larboard gunners, be ready, and let her have it as we pass!”

A minute later, and the Adventure’s broadside again crashed into the Spaniard’s stern; and again uprose the hideous answering outburst of shrieks and yells on board the latter as the English ship, with her sails clean full, slid square across her antagonist’s stern, the only reply to her broadside being four shot discharged from the enemy’s stern ports, not one of which did a groat’s worth of damage.

A tall figure completely encased in armour sprang up on the Spanish ship’s poop rail and, shaking his naked sword at Marshall, shouted in Spanish:

“You are a coward, señor Englishman! Why do you not fight fair, broadside to broadside, instead of sheltering yourself under my stern, where my shot cannot reach you?”

“Because, señor, I do not happen to be a fool,” retorted Marshall in the same language. “But neither am I a coward,” he continued, “as I will prove to you within the next five minutes, if you will do me the honour to meet me on your own deck, whither I intend to come without further ado.”

“I shall be most happy, señor,” was the reply; and down jumped the Spaniard in a hurry, to issue certain orders apparently, for his voice, hollow in his helmet, was heard pealing out in a tone of command as the two ships drew apart.

“Larboard gunners, load your pieces again,” commanded Marshall, “and level them so as to take her on the main deck while we are in stays. Luff, helmsman, all you can; I want to get far enough to windward to be able to run down and lay her aboard on the next tack. Boarders, see to the priming of your pistols, and be ready to follow me presently. Now, ready about again, men! Down helm!”

As the Adventure hove in stays both ships fired their broadsides simultaneously, one of the English shot entering a port and dismounting a gun, while the rest struck fair in the wake of the deck and went clean through the Spaniard’s side, as could clearly be seen; while the Spaniard’s shot, as usual, flew overhead, again by great good luck missing everything.

“Now, up helm, steersman, and lay us aboard!” commanded Marshall. “Be ready, men, to throw your grapnels the moment that we touch; and boarders, stand by to follow me into the enemy’s main chains!”

As the two ships closed in toward each other for the final grip which was to decide the matter, the Spaniard holding her luff while the English ship bore up and ran down with the wind free, the archers and musketeers on both sides became busy, the Spaniards having a slight advantage because of the superior height of their ship, although this was more than counterbalanced by the greater quickness and accuracy of aim on the part of the English, who shot as coolly as though they had been practising at the butts, and seldom failed to hit their mark. Nevertheless, several Englishmen went down during the ensuing five minutes, and were carried below to Stukely, who now began to find himself surrounded by quite as many patients as he could conveniently attend to. Then the two ships crashed together, the grapnels were thrown, and Marshall, followed by every man whose legs could carry him and whose hands could wield a weapon, sprang into the Spaniard’s main rigging, leaving the Adventure to take care of herself.

It was a rash thing to do, perhaps; but it succeeded; for the Spaniards were too busily engaged in endeavouring to keep the enemy out of their own ship to think of boarding the other. And most desperate was the fight that ensued, the English being fully determined to force their way aboard the Spaniard, while the Spanish were as fully determined that they should not. The air became thick with flying arrows, and with the smoke of grenades and stinkpots flung down upon the boarders out of the enemy’s tops; while swords and pikes flashed in the sun, pistols popped, and men shouted and execrated as they cut and slashed at each other; and the glorious tropic morning was filled with the sounds of deadly strife. Dick Chichester—to let the reader into a secret—had, upon the first appearance of the Spanish ship, been greatly exercised in his mind lest he should fail in courage when the two ships came to blows; but with the discharge of the first shot the queer agitated feeling which he had mistaken for fear completely passed away, and was instantly forgotten; and now, his services being no longer required at the helm, he armed himself with a handspike snatched from the deck, and, watching his opportunity, flung himself from the Adventure’s poop into the enemy’s mizzen chains, climbing thence to the Spaniard’s poop, where was no one to oppose him. From thence he made his way down to the main deck, where were gathered all the crew in one spot, crowding together to resist the attack of the English; and upon the rear of these he flung himself with indescribable fury, whirling the terrible handspike with such destructive effect that the astounded Spaniards, thus taken unexpectedly in the rear, went down like ninepins, while their yells of anguish and dismay quickly threw the entire crew into complete disorder. So violent, indeed, was the commotion that the attention of the Spaniards was momentarily distracted from what may be termed the frontal attack, and of this distraction Marshall instantly availed himself to dash in on deck, where, with a few sweeps of his sword, he soon cleared standing room, not only for himself but also for half a dozen of his immediate followers. These in turn cleared the way for others, and thus in the course of a couple of breathless minutes every man of the Adventure’s crew had gained the deck of the Spaniard, after which the capture of the ship was a foregone conclusion. The rush of Marshall and his party on the one hand, and the onslaught of Dick Chichester with his whirling handspike on the other so utterly distracted and demoralised the Spaniards that they presently broke and fled, flinging away their weapons, and crying out that their foes were a crew of demons who had assumed for the nonce the outward semblance of Englishmen! The hatches were promptly clapped on over the fugitive Spaniards, then Marshall and his followers paused to recover their breath and look about them.

The first thing to claim their attention was the ships themselves. These, being lashed together by means of the grapnels, were grinding and rasping each other’s sides so alarmingly, as they rolled and plunged in the sea that was running, that they had already inflicted upon each other an appreciable amount of damage, and threatened to do a great deal more if prompt preventive measures were not taken. Marshall therefore called upon Winter, one of his lieutenants, to take a party of twenty men, and with them return to the Adventure, cast her adrift from the prize, and lie off within easy hailing-distance of the latter. This was done at once, Dick Chichester being one of those called upon by Winter to follow him aboard the Adventure, and as soon as the two ships were parted an investigation was made into the extent of the damage incurred by each ship. The result of this investigation was the discovery that the Adventure was much the greater sufferer of the two, her larboard main channel piece having been wrenched off, and the seams in the immediate neighbourhood opened, while three of the channel plates were broken, thus leaving the mainmast almost entirely unsupported on the larboard side. Water was entering the ship in quite appreciable quantities through the opened seams, and the men were therefore at once sent to the pumps to keep the leak from gaining, while the carpenter and Dick went below to see what could be done toward stopping it.

Meanwhile Marshall, assisted by his co-adventurers Dyer and Harvey, proceeded to overhaul the prize systematically, with the view of determining her value. The first fact ascertained was that the ship was named the Santa Clara; the second, that she hailed from Cadiz, in Old Spain; and the third, that she was homeward-bound from Cartagena, from which port she was twenty-two days out. Her cargo, although valuable enough in its way, was not of such a character as to tempt the English to go to the labour of transferring any portion of it to their own vessel. But, apart from the cargo proper, she was taking home ten chests of silver ingots, two chests of bar gold, and a casket of pearls, all of which were quickly transhipped to the Adventure, the crew of which thus found themselves the possessors of a fairly rich booty, while still upon the very threshold, as it were, of those seas wherein they hoped to make their fortune. But this was not all; for, in the process of rummaging the captain’s cabin, Marshall found certain letters which he unhesitatingly opened and read, and among these was a communication from the governor of Cartagena advising the home authorities of the impending dispatch of a rich plate ship for Cadiz. The probable date of dispatch was given as three months after the departure of the Santa Clara, or about ten weeks from the date of that vessel’s capture by the English. That letter Marshall thrust into his pocket, together with certain other documents which he thought might possibly prove of value; then, summoning the unhappy Spanish captain to his presence, he informed him that the English having now helped themselves to all that they required, he was at liberty to proceed upon his voyage; and this Marshall recommended him to do with all diligence and alacrity, lest peradventure he should fall into the hands of certain other British buccaneers, at the existence of whom the Englishman darkly hinted, hoping thus to nip in the bud any plan which the Spaniard might have formed for a return to Cartagena with a report of the presence of English corsairs in the Caribbean Sea. The two ships then parted company, the Santa Clara steering northward close-hauled against the trade wind, while the Adventure bore up for Barbados, shaping a course to pass round its southern extremity. Two hours later the English ship was riding snugly at anchor in what is now known as Carlisle Bay, in five fathoms of water, within four hundred feet of the beach, and the same distance from the mouth of a small river, within which, as Bascomb explained, lay the creek which he had fixed upon in his mind as a suitable spot wherein to careen the ship.

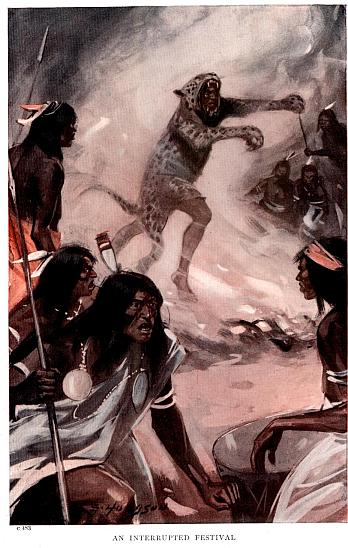

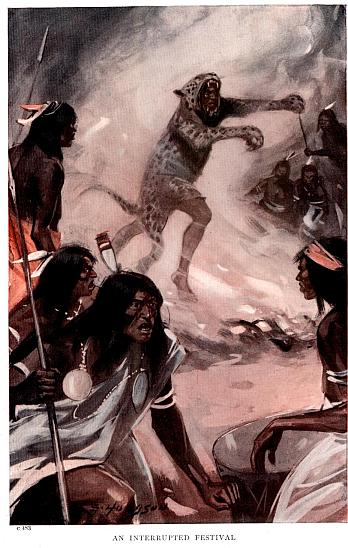

Chapter Three.

How they came to Barbados; and what they did there.

The rumbling of the great hempen cable out through the hawse-pipe served as a signal to some dozen or more of poor scurvy-stricken wretches who lay gasping in their hammocks in the stifling forecastle. They had heard the cry of “Land ho!” some hours before, and had groaned with bitter impatience when the subsequent sounds from the deck had made it clear to them that a battle must be fought before they could feast their eyes upon the sight of solid earth and green trees once more, and satisfy their terrible craving for the luscious fruits which they had been given to understand were to be obtained on the delectable island in sight for the mere trouble of plucking. But now at last the time of waiting was over; the sounds and shouts incidental to the taking in of sail, and, still more, the splash of the anchor and the roar of the cable as it rushed through the hawse-pipe told them that the ship had arrived, and with one accord they rolled out of their hammocks—the less heavily stricken helping their weaker fellow sufferers—and made their way on deck, where the business of stowing the ship’s canvas was still in full progress. The poor wretches were constantly getting in the way of those who were well and busy, but the latter were themselves just then much too happy to grumble or find fault, so the invalids were good-humouredly assisted up the ladder to the top of the forecastle, where they could enjoy an uninterrupted view of the island, and left there to feast their eyes upon its beauties in peace, until the time should arrive when their shipmates would be ready to man the boats and take them ashore.

And what a glorious sight it was that met their gaze. First of all there was the green and placid water, alive with fish, rippling gently to a narrow beach of golden sand, and beyond that sand nothing but vegetation, rich, green, and luxuriant. Green! yes, but of a hundred different tints, from the tender hue of the young shoots that was almost yellow, to a deep olive that turned to black in the shadows. If the tints of the vegetation were admirable, no less so were its forms; for there were palms of many different kinds, including the coconut palm in thousands, close down to the water’s edge. The traveller tree, shaped like a fan made of organ pipes; the banana and plantain, loaded with great bunches of fruit, each bunch a fair load for a man; there were great clumps of feathery bamboo; there were big trees covered with scarlet flowers instead of leaves; there was the flaming bougainvillea in profusion; and, in addition, there were great trailing cables of orchids, of weird shapes and vivid colouring reaching from bough to bough. Yes, there was plenty to see and marvel at, and there would be more when those few yards of rippling water had been spanned and their feet pressed the lush grass of yonder flowery mead close by the river’s margin; humming birds, the plumage of which shone in the sun like burnished gold and glowing gems, butterflies as big as sparrows, with wings painted in hues so gorgeous that the painter who should attempt to reproduce them would be driven to despair, enormous dragon-flies flitting hither and thither over the still surface of the river, kingfishers as big as parrots, monkeys in hundreds, agoutis, and, alas!—to strengthen its resemblance to that other Eden—serpents as well, contact with which meant death.

At last! at last! the sails were furled, the ropes coiled neatly down, the decks restored to order, and the word was given to lower the boats. Never, probably, was an order more joyously obeyed. The men rushed to the tackles with shouts and laughter, like schoolboys who have unexpectedly been given a holiday, and in an incredibly short time the boats were all afloat and were being brought one by one to the gangway. Then, under the joint supervision of the Captain and Stukely, the sick were led or carried along the deck and handed gently down over the side, the whole of them being sent ashore in the first boat that left the ship, with Bascomb, the master, in charge, his duty being to see that no unwholesome fruit or poisonous berries were eaten unwittingly. Next, the sick having been temporarily disposed of, there followed the strong and able-bodied, who took ashore with them spars, tackles, and spare sails, with which to rig up temporary tents; and soon the greensward was dotted with busy men, who, in the intervals of their labour, drank coconuts or eagerly devoured bananas, prickly pears, guavas, soursops, grapes, mangoes, and the various other fruits with which the island abounded. By and by, when a certain large tent had been erected beneath the shade of a giant ceiba tree, a boat put off from the shore to the ship, and presently returned bearing nine wounded men—the result of their fight that morning—under the especial care of Philip Stukely. These men, lying in their hammocks as they had been taken out of the ship, were then carried up to the completed tent, when their hammocks were re-slung to stout poles firmly driven into the ground, and where Stukely once more, and at greater leisure, attended to their hurts. But there was one form, lying stark in a laced-up hammock deeply stained with blood, which was not brought up to the tent. It was all that remained of George Lumley, Captain Marshall’s chief lieutenant, who had been shot to death in the very act of boarding the Spaniard, a few hours before; and a grave having been prepared in a small open space on the opposite side of the river, under the shadow of a splendid bois immortelle which strewed the ground with its glowing scarlet flowers, a trumpet was blown, calling the crew together. Then, when they were all assembled, they entered the boats, at a sign from Marshall, took in tow the boat containing the body of the officer, with Saint George’s Cross at half-mast trailing in the water astern of her, and, having reached the other side, reverently bore the shrouded corpse to its last resting-place, lowered it into the grave, Marshall, meanwhile, reading the burial service, and covered it up with the rich brown earth. This service rendered they returned to the site of the camp, and rapidly proceeded to put up the other tents needed to enable all hands to sleep ashore that night.

The sun was within an hour of setting when at length everything was completed to Marshall’s satisfaction, and the men were told that they might cease work and amuse themselves as they pleased, the permission being accompanied by a caution that they were not to wander more than a quarter of a mile from the camp, not to go even as far as that, singly, and not to go unarmed; for although it was assumed that the island was uninhabited, save by themselves, it was recognised as quite possible that a band of Spaniards might be somewhere upon it; and, if so, they would probably have witnessed the arrival of the ship, and might, if strong enough, attempt to surprise and capture both camp and ship. The men therefore made up little parties, and for the most part went off into the woods, either to gather more fruit or to look for gold, some of them seeming to be possessed of a firm conviction that, being now in “the Indies”, they must inevitably find the precious metal if they only searched for it with sufficient diligence. As for Dick and Stukely, the latter having by this time done all that he could for his patients, they went off for a stroll together along the beach, in the direction of the southern end of the bay.

“Well, Dick, what think ye of fighting, now that you have had a taste of it?” demanded Stukely, slipping his hand under Chichester’s arm as they turned their backs upon the camp. “And, by the way,” he continued, without waiting for a reply to his question, “you must permit me to offer the tribute of my most respectful admiration; for I am told that you carried yourself like a right valiant and redoubtable cavalier; indeed the Captain has not hesitated to say that, but for your most furious onslaught upon the Spaniards’ rear this morning, while he was leading the attack by way of the main rigging, matters were like enough to have gone very differently with us.”

“Oh, that is all nonsense,” laughed Dick. “I saw that Marshall wished to reach the deck of the Spaniard; I noticed that the Spanish crew had all congregated together in one place to stop him; and it struck me that I could best help by falling upon them in the rear, which I saw might be done right easily, there being no man to stop me—so—I did it.”

“Precisely; with the result that the Spaniards, finding themselves thus suddenly and furiously assailed by one who bore himself like a very Orson, and feeling no desire to have their brains beaten out with so heathenish a weapon as a handspike, incontinently gave way before you and scattered, affording Marshall an opportunity to climb in over the bulwarks. But were ye not afraid, lad, that some proud Spaniard, resenting your interference, might slit your weasand with his long sword?”

“Afraid?” returned Dick. “Not a whit. ’Tis true that when we first sighted the enemy coming out from behind this same island, and I learned that our Captain meant to attack him, I turned suddenly cold, hot as was the morning, and was seized with a plaguy doubt as to whether I should be able to carry myself as an Englishman and a Devon man should in the coming fight; but when the battle began I forgot all about my doubts, and thought no more of them until the fight was over and done with. Indeed, to be quite frank with ye, Phil, I was never happier, nor enjoyed myself more, than during the few minutes that the fight lasted. You know not what it feels like, for you were down in the cockpit, which was your proper place; but you may take my word for it that there is nothing in this world half so exhilarating as a good brisk fight.”

Stukely laughed. “True, lad,” he said; “I do not know from actual experience what it feels like to be engaged in a life-and-death struggle; for I have never yet taken part in such. Yet I can well believe that it is as you say; for even down in the cockpit I felt the thrill and tingle of it all as I listened to the booming of the ordnance and heard the shouts of the men and the commands of the Captain; nay, I will go even farther than that, and confess that I had much ado to restrain myself from deserting my post and rushing up on deck to take my part in it all. And, a word in your ear, Dick—I believe I should make a far better leader than I am ever like to be a surgeon; for as I stood there, listening to the sounds of the conflict, the strangest feeling of familiarity with it all came to me. I suddenly felt that I had fought many’s the time before; fleeting, indistinct visions of contending hosts, strangely armed and arrayed, floated before me; cries in a strange language, which still I seemed to understand, rang in my ears; and for a moment I completely lost sight of my surroundings, being transported to a land of cloudless skies, even as this, clothed with vegetation very similar to what we now behold around us, although the land of my vision was mountainous, with lakes that shone like mirrors embosomed among the mountains and were dotted with islands, some of them palm-crowned, while others bore stately temples of strange but beautiful architecture. And the strangest part of it all was that, while it lasted, it was like a vivid memory of some scene that my eyes had rested upon often enough to grow familiar with, ay, as familiar as I am with the streets of Devonport and Plymouth!”

“Ay; you were ever a fanciful fellow and a dreamer, Phil,” replied Dick, who was one of the most matter-of-fact individuals who ever breathed. “I mind me how, many a time, when we have been sailing together outside Plymouth Sound, where a clear view could be had of the setting sun, you used to trace cloudy continents with bays, inlets, harbours, and outlying islands in the western sky; yes, and even ships sailing among them, and cities rearing themselves among the golden edges of the clouds.”

“Well, and was that so very wonderful?” retorted Stukely. “Look at yonder sky, for instance. Can you not imagine that great purple mass of cloud to be a vast island set in the midst of the sea represented by the blue-green expanse of sky beyond it? And can you not see how the shape of the cloud lends itself to the fancy of jutting capes and forelands, of gulfs and sounds and estuaries? And look at those small, outlying clouds nearest us; are not they the very image and similitude of islets lying off the coast of the main island? And, as to cities, what can be a more perfect picture of a golden city built along the shore of a landlocked bay than that golden fringe of cloud yonder? And behold the mountains and valleys—ay, and there is a lake opening up now in the very centre of the island. Oh, Dick, my son, if you have not imagination enough to translate these pictures of the evening sky into glimpses of fairy land, and to derive pleasure therefrom, I pity you from my very soul.”

“Nay, then, no need to waste your pity on me, Sir Dreamer, for I need it not,” retorted Dick. “Doubtless you take joy of your fancies; but realities are good enough for me, at least such realities as these. Look at that bird hovering over yonder flower, for instance; smaller, much smaller, than a wren is he, yet how perfectly shaped and how gloriously plumaged. Look to the colour of him, as rich a purple as that of your sunset cloud, with crest and throat like gold painted green. And then, the long curved beak of him, see how daintily he dips it into the cup of the flower and sips the honey therefrom. And his wings, why they are whirring so quickly that you cannot see but can only hear them! Can any of your fancies touch a thing like that for beauty?”

“That is as may be, Dick,” answered Stukely. “The bird is beautiful, undoubtedly, and no less beautiful is the flower from which he sips the honey that constitutes his food; indeed all things are lovely, had we but eyes to perceive their loveliness. But come, the sun has set, and darkness will be upon us in another five minutes; it is time for us to be getting back to the camp.”

Despite the croaking of the frogs, the snore of the tree toads, the incessant buzz and chirr of insects, and the multitudinous nocturnal sounds incidental to life upon a tropical island overgrown with vegetation, ay, and despite the mosquitoes, too, all hands slept soundly that night, and awoke next morning refreshed and invigorated, the sick especially exhibiting unmistakable symptoms of improvement already, due doubtless to the large quantities of fruit which they had consumed on the preceding day. The wounded, too, were doing exceedingly well, the coolness of the large tent in which they had passed the night, as compared with the suffocating atmosphere of their confined quarters aboard ship, being all in their favour, to say nothing of the assiduous care which Phil bestowed upon them.

The first thing in order was for all hands who were able to go down to the beach and indulge in a good long swim, shouting at the top of their lungs, and splashing incessantly, in accordance with Marshall’s orders, in order to scare away any sharks that might chance to be prowling in the neighbourhood. Then, a spring of clear fresh water having been discovered within about three-quarters of a mile of the camp, one watch was sent off to the ship to bring ashore all the soiled clothing, while the other watch mounted guard over the camp; after which all hands went to breakfast; and then, working watch and watch about, there ensued a general washing of soiled clothes at the spring, and a subsequent drying of them on the grass in the rays of the sun. This done, a gang was sent on board the ship to start the remaining stock of water and pump it out; after which the ship was lightened by the removal of her stores, ammunition, and ordnance, until her draught was reduced to nine feet, when her anchor was hove up and she was towed into the river, where she was moored, bow and stern, immediately abreast of the camp. The completion of this job finished the day’s work, at the end of which Marshall, having mustered all hands, proclaimed that in consequence of the lamented death of their gallant shipmate and officer, Mr Lumley, he had decided to promote Mr Winter to the position thus rendered vacant; and further that, as a second lieutenant was still required, he had determined, after the most careful consideration, to promote Mr Richard Chichester to that position, in recognition of the extraordinary valour which he had displayed on the previous day by boarding the Spanish ship and attacking her crew, single-handed, in the rear, thereby distracting the attention of the enemy and contributing in no small measure to their subsequent speedy defeat. This decision on the part of the Captain, strange to say, met with universal and unqualified approval; for Dick’s unassuming demeanour and geniality of manner had long since made him popular and a general favourite, while his superior intelligence, his almost instinctive grasp of everything pertaining to a ship and her management, and his dauntless courage, marked him out as in every respect most suitable for the position which he had been chosen to fill.

The next two days were spent in clearing everything movable out of the ship, in preparation for heaving her down; after which she was careened until her keel was out of water, when the grass, weed, and barnacles which had grown upon her bottom during the voyage were effectually removed, her seams were carefully examined, and re-caulked where required, and then her bottom was re-painted. This work was pushed forward with the utmost expedition, lest an enemy should heave in sight and touch at the island while the ship was hove down—for a ship is absolutely helpless and at the mercy of an enemy while careened—and when this part of the work was satisfactorily completed, all necessary repairs made, and the hull re-caulked and re-painted right up to the rail, the masts, spars, rigging, and sails were subjected to a strict overhaul and renovation. This work was done in very leisurely fashion; for Marshall had by this time quite made up his mind to lie in wait for the plate ship which, as he had learned through documents found on board the Santa Clara, was loading at Cartagena for Cadiz, and he speedily arrived at the conclusion that a considerable amount of the waiting might as well be done at Barbados as elsewhere. For the climate of the island was healthy, the sick were making excellent progress on the road toward recovery, and it was essential to the success of his enterprise that every man of his crew should be in perfect health; moreover, apart from the crew of the Santa Clara—which ship, he had every reason to believe, was daily forcing her way farther toward the heart of the North Atlantic—not a soul knew, or even suspected, the presence of the Adventure in those seas; consequently he resolved to remain where he was until the last possible moment. Such work, therefore, as needed to be done was done with the utmost deliberation and nicety; and when at length all was finished there still remained time to spare, which the men were permitted to employ pretty much as they liked, it having by this time been ascertained conclusively that, apart from themselves, the island was absolutely without inhabitants.

At length, however, the time arrived when it became necessary to put to sea again; and on a certain brilliant morning the camp was struck, all their goods and chattels were taken back to the ship; and, with every man once more in the enjoyment of perfect health, with every water cask full to the bung-hole of sweet, crystal-clear water, and with an ample supply of fruit and vegetables on board, the Adventure weighed anchor and stood away to the westward under easy sail, passing between the islands of Saint Vincent and Becquia with the first of the dawn on the following morning.