The Project Gutenberg EBook of Owen Hartley; or, Ups and Downs, by

William H. G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Owen Hartley; or, Ups and Downs

A Tale of Land and Sea

Author: William H. G. Kingston

Illustrator: M. Stretch

Release Date: February 3, 2008 [EBook #24502]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OWEN HARTLEY; OR, UPS AND DOWNS ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

William H G Kingston

"Owen Hartley; or, Ups and Downs"

Chapter One.

“Well, boy, what do you want?”

These words were uttered in a no pleasant tone by an old gentleman with a brownish complexion, a yellowish brown scratch wig, somewhat awry, a decidedly brown coat, breeches, and waistcoat, a neckcloth, once white, but now partaking of the sombre hue of his other garments; brown stockings and brownish shoes, ornamented by a pair of silver buckles, the last-mentioned articles being the only part of his costume on which the eye could rest with satisfaction.

On his lap was placed a pocket handkerchief, of a nondescript tint, brown, predominating, in consequence of its frequent application to a longish nose, made the recipient of huge quantities of snuff. Altogether there was a dry, withered-leaf-like look about the old man which was not prepossessing. His little grey eyes were sunk deeply in his head, his sight being aided by a large pair of tortoiseshell spectacles, which he had now shoved up over his forehead.

He was seated on a high stool at a desk in a little back dingy office, powerfully redolent of odours nautical and unsavoury, emanating from coils of rope, casks of salt butter, herrings, Dutch cheese, whale oil, and similar unaromatic articles of commerce. It was in that region made classical by Dibdin—Wapping. The back office in which the old gentleman sat opened out of one of much larger proportions, though equally dull and dingy, full of clerks, old and young, on high stools, busily moving their pens, or rapidly casting up accounts—evidence that no idleness was allowed in the establishment. On one side was a warehouse, in which large quantities of the above named and similar ship’s stores were collected. In front was a shop, the ceiling hung with tallow candles, brushes, mats, iron pots, and other things more useful than ornamental. From one end to the other of it ran a long, dark-coloured counter, behind which stood a man in a brown apron, and sleeves tucked up, ready to serve out, in small quantities, tea, sugar, coffee, tallow candles, brushes, twine, tin kettles, and the pots which hung over his head, within reach of a long stick, placed ready for detaching them from the hooks on which they were suspended. In the windows, and on the walls outside, were large placards in red and black letters, announcing the sailing of various ships of wonderful sea qualities, and admirable accommodation for passengers, with a statement that further information would be afforded within.

“Speak, boy; what do you want?” repeated the old gentleman, in a testy and still harsher tone than before, as he turned round on his stool with an angry glance under his spectacles. “Eh?”

The person he addressed was a fair complexioned boy, about twelve years old, with large blue eyes, and brown hair in wavey curls, a broad forehead, and an open, frank, intelligent countenance. He was dressed in a jacket and trousers of black cloth, not over well made perhaps, nor fresh looking, although they did not spoil his figure; his broad shirt collar turned back and fastened by a ribbon showed to advantage his neck and well-set-on head. It would have been difficult to find two people offering a greater contrast than the old man and the boy.

“Please, sir,” answered the latter, with considerable hesitation, “Farmer Rowe wished me to come here to see you, as he hopes—”

“And who in the name of wonder is Farmer Rowe, and who are you?” exclaimed the old gentleman, kicking his heels against the leg of the stool.

Before the boy could find words to go on with what he was saying, or could check the choking sensation which rose in his throat, a clerk, the counterpart of his master, in respect of dinginess and snuffiness, entered with a handful of papers which required signing, and a huge folio under his arm. As, in the eyes of the old gentleman, his business was of far more consequence than any matter which could be connected with that pale-faced, gentle boy in the threadbare suit, he turned round to the desk, and applied himself to the papers, as his clerk handed them to him in succession.

The boy was, in the meantime, left unnoticed to his own reflections. While the old gentleman was absorbed in the folio, the clerk gave a glance round at the young stranger, and the expression conveyed in that glance did not add pleasantness to the lad’s feelings, as he stood clutching his crape-bound hat. Leaving the two old men engaged in their books and papers, a fuller account must be given of the boy than he was likely to afford of himself.

Some thirty years before the period at which this history commences a young gentleman, Owen Hartley, who was pursuing his academical course with credit, preparatory to entering the ministry, fell in love during a long vacation with a well-educated young lady of respectable position in life, if not of birth equal to his. She returned his affection, and it was agreed that they should marry when he could obtain a living. Being ordained, he was appointed to a curacy of 50 pounds a year, in which post he faithfully discharged his duty, expecting to obtain the wished-for incumbency. Susan Walford existed on the same hope, but year after year passed by, and she grew pale, and even his spirits sometimes sank, when the realisation of their expectations seemed likely to be indefinitely deferred. At length, however, he obtained a living. It was one no person, except in his circumstances, would have taken. No wonder; it was among the fens of Lincolnshire, and, after certain deductions, scarcely produced a hundred a year. Still it was a living, and a certainty. At the same time Susan received a legacy. It made their hearts very grateful; although the amount was small, yet, in their eyes, it seemed magnificent, a clear 350 pounds. To be sure, 300 pounds would produce only 12 pounds a year when invested, still, that was something added to a hundred.

The extra fifty was retained for furnishing the vicarage. Ten years they had waited patiently, now they were married, and were contented and happy. They did not live for themselves alone, but to be a blessing to all around them. True, they could not give money, but Owen gave Gospel truths, simple and without stint; and she, kind words and sympathy, and a portion of many of their scanty meals. The hale as well as the sick were visited, believers strengthened and encouraged, and inquirers instructed. They reaped a rich harvest of affection from their parishioners. Three years after their marriage a son was born; he was a treasure for which they were grateful, and he was their only one. The little Owen flourished, for he was acclimatised, but the breezes which blow over those Lincolnshire fens are raw and keen, if not generally unhealthy to the natives, and the vicar and his wife began to complain of touches of ague, which became, as time went on, more and more frequent. An income of 112 pounds a year will not allow the happy possessors to indulge in many of the luxuries of life, and certainly not in that of foreign travel. When, therefore, the parish doctor hinted that a change of climate, and more generous diet and port wine, were absolutely necessary for their restoration, Mr Hartley smilingly observed, that as he did not think a better climate would come to them, and as they certainly could not go to it, he did not see how the combination could be brought about; and as to port wine, it had long been a stranger to his palate, and was likely to continue so. Still the doctor urged that he must take it, and sent him some from his own store, and, moreover, spoke so very earnestly to Mrs Hartley, saying that her husband would altogether be incapacitated from performing his duties unless he was supplied with stimulants and more food, that she resolved to do what many have resolved to do before, and will do again under similar circumstances. She did not exactly kill the golden goose, but began to sell out. It was indeed pleasant to have 20 pounds at command. She ordered wine of the best, with beef steaks and mutton chops, such things had rarely before been seen at the vicarage. The butcher wondered, but she paid regularly, and he asked no questions. She, however, only made-believe to eat of them herself, that Owen might have the more; and when he came home to dinner she was sure to have taken a large luncheon while he was out. She thought that his health was improving, and he declared that he felt stronger.

So delighted was she with the result of this new system, that she ordered more port wine, and still more amply supplied the table. Yet the doctor was not satisfied, and urged change of air for a short time—“His life is so valuable,” was his remark, and the doctor’s observation conquered all scruples. A clergyman to do Owen’s duty was to be obtained, no easy matter, and he must be paid. One was found, and the excursion made. Mr Hartley felt wonderfully better, but not many weeks after his return the terrible ague again attacked him. Week after week he was unable to perform his ordinary duty. He staggered to the church, and in a voice which he could with difficulty render audible, preached the glorious Gospel as before.

The parish did not suffer so much as it might have done, for Susan visited the parishioners more frequently than ever. At length the faithful wife herself fell ill.

The disease made more rapid progress in her weak frame than it had done in that of her husband. Owen now compelled her to take the same remedies which she had given to him; both lingered on, striving to do their duty. The vicar was apparently getting better, and Susan revived sufficiently to enable her to assist in the education of the younger Owen. Year after year showed the ravages illness was making on their frames; the doctor shook his head when the parishioners inquired after them. Susan died first, Owen did not mourn as one without hope, although it was evident that he had received a terrible blow. Since his marriage he had placed all worldly concerns in Susan’s hands—no child could have known less than he did how to manage them—the consequences were inevitable. The vicar got into debt, not very deeply at first, a few pounds only, but to these few pounds others were gradually added.

The vicar had a faithful servant, Jane Hayes, who, when a girl, had come to him and Mrs Hartley on their marriage, for her food and enough wages to buy clothes. Jane went and went again to the shops for such provisions as she considered the vicar and Master Owen required.

One was too ill, the other too young to make inquiries or consider how they were to be paid for. When by chance any tradesman demurred, Jane was very indignant, asserting confidently that the vicar would pay for whatever he had when his dues came in.

Mr Hartley now no longer rose from his bed. A neighbouring clergyman, not much better off than himself, came over occasionally to perform the duty in the church, getting his own done by a relative who was paying him a visit. Mr Hartley, although ready to depart, clung to existence for the sake of his boy. When he had sufficient strength to speak, he repeated to young Owen the advice and exhortations he had constantly given him when in health. They came now, however, with greater force than ever from the lips of the dying man, and words which before had been heard unheeded, now sank deeply into the heart of the boy.

Young Owen knew nothing of the world, he had never left home, but he was thus really better prepared to encounter its dangers and difficulties than many who go forth, confident in their own strength and courage. He scarcely had, hitherto, realised the fact that his father was to be taken from him.

“My boy,” said the village doctor, as he led him into his father’s room, “you must be prepared for the worst.”

These words made Owen feel sick at heart.

While the vicar clasped the hand of his boy, and gazed into that beloved young face, his gentle spirit winged its flight to heaven, and Owen knew that he was an orphan. He was not aware, however, how utterly destitute he had been left. The vicar had to the last been under the impression that the larger portion of Susan’s fortune, for so he was pleased to call it, still remained, and that it would be sufficient to start Owen in life. He had paid great attention to the education of his boy, who possessed a much larger amount of general knowledge than most lads of his age. The principal people in the parish attended the coffin of their late vicar to the grave. They had not far to go from the vicarage to the churchyard.

Farmer Rowe, who lived near, at Fenside Farm, had been the faithful friend of Mr Hartley from the time of his first coming to the parish, and taking him by the hand, followed as a mourner. Owen bore up during the ceremony, but on returning to his desolate home, at length gave way to the grief which was well-nigh breaking his young heart.

“Don’t take on so, Master Owen,” cried Jane, leading him to his little room; “he who is gone would not wish you to grieve. He is happy, depend upon it, and he wants you to be happy too. We shall have to leave this, I am afraid, for they will not let you take your father’s place, seeing you are somewhat young, otherwise I am sure you could do it. You read so beautiful like, and I would rather hear a sermon from you than any one.”

Owen shook his head.

“No, Jane, I should have to go to college first; a person must be regularly ordained before he could come and preach in our church.”

Still Jane was not convinced on that point, and she inquired from Farmer Rowe whether he could get Master Owen made vicar in his fathers stead.

“That is impossible, Jane,” answered the farmer, smiling. “We will, however, do our best for the boy; we must look into the state of his affairs, for I can hear of no kindred of his who are likely to do so.”

Owen was allowed to remain at the vicarage longer than might have been expected. It was not easy to find a successor to Mr Hartley. The place had a bad name, few incumbents had lived long there. The tradesmen of Reston, the neighbouring town, however, somewhat hesitated about supplying Jane with provisions.

“But there is the furniture,” she answered, “and that will sell for I don’t know how much; it is very beautiful and kept carefully.”

In Jane’s eyes it might have been so, as it was superior to what she had seen in her mother’s humble cottage. In the meantime she employed herself in preparing a proper suit of mourning for Owen.

“The dear boy will have to go out among strangers, and he shall be well dressed, at all events,” she observed as she stitched away at his garments. She had to work up all sorts of old materials. Her own small wages were due, but of that she thought not; her great desire was that her young master should be properly dressed.

At length, however, the creditors put in their claims; the furniture and all the property of the late vicar had to be sold, but it was insufficient to meet their demands. Farmer Howe, knowing he matters were likely to turn out, took Owen to his house.

The farmer had a large farm of his own, but there had been a bad harvest, and at no time had Fenside Farm been a very profitable one; he therefore could not do as much for the poor lad as his kind heart dictated. His second son David, the scholar of the family, as he called him, who was articled to an attorney in a neighbouring town, happened at the time to be at home.

“David,” said Farmer Howe, “surely the vicar and his wife must have had some kith and kin, and we must find out who they are; they may be inclined to do something for the boy, or, if not, they ought to do so.”

“The first thing I would suggest, father, is to question Owen, and hear what he knows about the matter,” answered David; “we may then see what letters the poor lady or the vicar have left; they may throw some light on the subject.”

Owen was forthwith called in. He had seldom heard his parents allude to their relatives, but he held an opinion that his father had several, and from the way in which he had heard them spoken of he fancied that they were some great people, but who they were he could not tell. They certainly, however, had never shown any regard for Mr Hartley, or paid him the slightest attention. Owen knew that his mother had relations, and that her father had been in some public office, but had died without leaving her any fortune; his grandmother had also died a year or two after her marriage. This much Owen knew, but that was very little. “Oh yes,” he said, “I remember that her name was Walford.”

“Well, that must have been your grandfather’s name too. Do you know what your mother’s maiden name was?” asked David.

Owen could not tell.

“Perhaps it will be in some of her books,” suggested David. “They sometimes help one in such cases as this.”

“The books, I am afraid, were sold with the other property,” said the farmer.

“Then we must find out who bought them,” remarked David; “perhaps Dobbs of our town did. I saw him at the sale. He is not likely to have disposed of them yet; I will get him to let me look over them.”

David fulfilled his promise. Mr Dobbs allowed him to look over the library of the late Vicar of Fenside, and at length he came to a volume of “Sturm’s Reflections,” on the title page of which was written, in a clear mercantile hand, “Given to Susan Fluke, on her marriage with Henry Walford Esquire, by her loving cousin Simon Fluke.”

David bought the volume and returned with it in triumph. “I have, at all events, found out the maiden name of the boy’s grandmother on his mother’s side, so, if we cannot discover his relatives on one side, we may on the other. We have now got three names—Fluke, Walford, and Hartley. The Hartley side will give us most difficulty, for it is clear that the vicar and his father held no communication for many years with any of the relatives they may have possessed. Fluke, however, is not a common name; we will search among the Flukes and Walfords, and see if any persons or person of those names will acknowledge young Owen. Simon Fluke, Simon Fluke—the London and County Directories may help us; if they cannot, we must advertise. It will be hard if we cannot rake up Simon Fluke or his heirs. To be sure, that book may have been given to his grandmother fifty years ago or more, and Simon Fluke may be dead.”

David carefully locked up the book. “It may tend to prove your relationship with the said Simon Fluke; and who knows that he may be, or may have been, a rich man, and that you may become his heir,” he remarked to Owen.

Owen, although he listened to what the young lawyer said, scarcely understood the full meaning of his observations. Farmer Rowe, ill as he could afford the expense, sent David off next day to London to make inquiries. Both the farmer and his family did their best to amuse the orphan.

Although the hearts of the young are elastic, his loss had been so recent, and his grief so overpowering, that, in spite of all the efforts of his kind friends, he could not recover his spirits. Owen, however, had become calmer when Jane Hayes came to wish him good-bye. She had been offered another situation, which, seeing that he was well taken care of, she had accepted. Owen was in the garden when Jane arrived; the sight of her, as she came to meet him, renewed his grief. They sat down on a bench together, under a tall old tulip-tree, just out of sight of the house. Owen burst into tears.

“That’s just what I feel like to do, Master Owen,” said the faithful woman, taking his hand; “but it seems to me, from all master used to say when he was down here with us, that up there, where he and missis have gone, there is no crying and no sorrow. So you see, Master Owen, you should not take on so. They had their trials on earth, that I am sure they had, for I seed it often before you was born; but when you came you was a blessing to them. Now they are happy, that is the comfort I have.”

“I am not crying for them, Susan,” said Owen, trying to stifle his tears, “I am crying for myself; I cannot help it. I know you love me, and you always have ever since I could remember—if you punished me it was kindly done—and now you are going away, and I do not know when I shall see you again. Mr Rowe is very kind and good, and so are Mrs Rowe, and John, and David, and their sisters, but, Jane, it is from pity, for they cannot care much about me, and I feel all alone in the world.”

“Well, I will give up the place, Master Owen, and work for you; I cannot tell how I should ever have had the heart to think of going away and leaving you among strangers, although I have known Farmer Rowe and his family all my born days, and good people they are as ever breathed.”

Owen took her hand and put his head on her lap, just as he used to do when he was a little child, and thus he remained without speaking. Jane looked down on him with the affection of a mother, and tears dropped slowly from her eyes.

“The Lord bless the boy,” she murmured to herself, as she lifted her face towards the blue sky, “and take care of him, and give him strength against all the enemies he will have to meet—the world, the flesh, and the devil.” Her plain features—for Jane had little to boast of in regard to good looks—were lighted up with an expression which gave her a beauty many fairer faces do not possess.

Owen lay still for some time; Jane thought that he was sleeping, and was unwilling to arouse him. At length, looking up, he said—

“I never can repay you enough for all you have done for me. I should be acting a cowardly part if I were to let you give up a good place for my sake, and allow you to toil and slave for me, when I am ready enough to work for my own support; you cannot tell how much I can do, and how much I know. I do not say it for the sake of boasting, but my father assured me that I knew enough to teach boys much older than myself. If I was bigger, I could become an usher at a school, or perhaps Mr Orlando Browne, David Howe’s employer, would take me as a clerk. So you see, Jane, that I am not afraid of having to work, or afraid of starving; you must therefore go to Mrs Burden’s and look after her children, I am sure that they will love you, and then you will be happy. It is the knowing that some one loves us that makes us happy, Jane. I know that you love me, and that makes me happy now.”

“Ah, Master Owen, there is One who loves you ten thousand times more than I can do, and if you will always obey Him, you will never cease to be happy too. Master often used to say that to us, you mind. Ah! if you think of his sayings—and he spoke the truth out of the Book—it will be a blessing to you.”

“Thank you, Jane, for reminding me,” answered Owen, his countenance brightening. “I do, I do; I will try ever to do so.”

“That’s right, Master Owen, that’s right,” said Jane; “it makes me very glad to hear you say that.”

The shades of evening were coming on; they warned Jane that she ought to be on her way. Unwillingly she told Owen that she must be going. He accompanied her to the gate, for she could not bring herself to go in and say good-bye to the farmer’s family. “They will know that it was from no want of respect,” said Jane. “God bless you, Master Owen, God bless you.”

Owen looked after her until she was lost to sight at the end of the lane. It was some time before he could command himself sufficiently to go back into the house.

Chapter Two.

David Rowe had been a week in London engaged in the search for Owen’s relatives. At last a letter came from him, desiring that the trap might be sent over to Reston, as he would be down, God willing, by the coach that day.

His arrival was eagerly looked for by all at Fenside Farm. David’s laconic letter had not mentioned anything to satisfy their curiosity.

“Well, lad, what news?” exclaimed the farmer, as David stood while his mother and sister Sarah assisted him off with his great-coat. “Have you found out friends likely to help young Owen?”

“As to that I cannot exactly say,” answered David; “I have discovered a relative who ought to help him—the identical Simon Fluke who gave the book to Susan Walford. Simon Fluke must be the boy’s cousin, although removed a couple of degrees; but that should make no difference if Simon had any affection for his cousin, for the boy is certainly her only surviving descendant.”

“But have you had any communication with Simon Fluke?” inquired the farmer.

“No, I thought that would be imprudent; it would be politic to let the boy introduce himself. I made all inquiries in my power, however, and ascertained that Simon Fluke is a bachelor, reputed to be rich, and has a flourishing business as a ship’s chandler. As to his character, all I can learn is, that he is looked upon as a man of honour and credit in his business, although of somewhat eccentric habits. In regard to his private character I could gain no information; he may be as hard-hearted as a rock, or kind and generous. I went to his place of business in the hopes of having the opportunity of forming an opinion for myself, but I failed to see him, and therefore had to come away as wise as I went.”

“What step do you advise us to take next?” asked the farmer.

“Send him up at once, and let him present himself at Simon Fluke’s—say who he is, that his parents are dead, and that he wishes for employment. Do not let him appear like a beggar asking for alms; he will succeed best by exhibiting an independent spirit, and showing that he is ready to do any work which is given to him. We know he is quick, intelligent, writes a beautiful hand, and has as good a head on his shoulders as many a much older person.”

“But surely we cannot send the boy up by himself,” urged Mrs Rowe; “and you, I suppose, cannot go again! David?”

“I’ll go with him, mother,” said John, the eldest son, “and willingly bear the charge, for I should be glad to get a chance of seeing the big city. If Simon Fluke were to refuse to receive young Owen, what would become of the boy? I have heard of dreadful things happening to lads in London, especially when they have no friends to care for them.”

And so it was settled. John undertook to start the very next morning, if Owen was willing to go.

Owen, who had been out in the garden making himself useful, now came in. David gave him the information he had obtained, and inquired whether he wished to pay a visit to his supposed relative?

“If he is likely to give me something to do, I am willing to go and ask him,” answered Owen.

“There is nothing like trying, and you can lose little by asking for it,” observed David.

Susan had prepared Owen’s wardrobe to the best of her ability, so that he was ready the next morning to start with John Rowe. They duly reached the great city, and John and Owen managed to find their way to Wapping. They walked about for some time, making inquiries for Paul Kelson, Fluke and Company, whose place of business was at last pointed out to them. They had passed it once before, but the name on the side of the door was so obliterated by time that it was scarcely legible.

“Now, Owen, you go in, and success attend you,” said John, shaking him by the hand, as if they were about to separate for an indefinite period. “Do not be afraid, I will not desert you!”

Owen, mustering courage, entered the dingy-looking office. John remained outside while Owen presented himself, as has been already described, to Simon Fluke.

Faithful John walked up and down, keeping a watchful eye on the door, in case Owen might be summarily ejected, and resolved not to quit his post until he had ascertained to a certainty that the boy was likely to be well cared for. “If the old man disowns him, I will take him to some London sights, and then we will go back to Fenside, and let him turn farmer if he likes, and I’ll help him; or it may be that David will hear of something more to his advantage, or perhaps find out some of his other relatives. David is as keen as a ferret, and he’ll not let a chance pass of serving the lad.” John’s patience was seriously tried. He saw seafaring men of various grades pass in and out, corroborating the account of the flourishing business of Paul Kelson, Fluke and Company, and he concluded, while Simon Fluke was engaged with them, that young Owen would have but small chance of being attended to.

“Well, I can but wait until they are about to close the place; then, if Owen does not come out, I must go in and look for him,” thought John. He was resolved, however, not to do anything which might interfere with the boy’s interests; it took a good deal to put John out of temper.

Meantime Owen’s patience was undergoing a severe trial. The two brown-coated old gentlemen appeared to him to be a long time looking over those big books. They had just concluded, when a junior clerk came in to say that Captain Truck wished to see Mr Fluke. Glancing at Owen as he passed, Mr Fluke hurried into his private room, while the old clerk, tucking the big books under his arm, and filling his hands with the papers, left the office. He stopped as he was passing young Owen.

“Sit down there, boy,” he said, pointing to a bench near the door; “Mr Fluke will speak to you when he is disengaged.”

Several persons came in, however, before Captain Truck had gone away. They were admitted in succession to speak to Mr Fluke; so Owen had to wait and wait on, watching the clerks as they sat at their desks, and observing the visitors as they paced up and down, while waiting their turns to have an interview with the principal of the establishment. This impressed Owen with the idea that the brown, snuffy old gentleman was a far more important personage than he had at first supposed. Several of the clerks who were moving about with papers in their hands frequently passed the young stranger, but no one spoke, or bestowed even an inquiring glance at him. Owen, who was tired with his journey and long walk, was, in spite of his anxiety, nearly dropping asleep, when he heard the words—

“Well, boy, what is it you want? Quick, say your business, I have no time to spare.”

The words were spoken by the brown-coated old gentleman. Owen, starting up, followed him into the inner office. Here Mr Fluke, nimbly taking his seat on his high stool with his back to the desk, again asked in a testy tone, “What is it you want?” Owen stood, hat in hand, as he had done nearly two hours before, and began briefly recounting his history.

“Tut, tut, what’s all that to me?” exclaimed the old gentleman, pushing up his spectacles, and taking a huge pinch of snuff, as he narrowly scrutinised the boy with his sharp grey eyes. “What more have you got to say for yourself?”

“I did not explain, sir, as I ought to have done at first, that my mother’s name was Walford, and that she was the daughter of a Miss Susan Fluke, who married my grandfather, Mr Henry Walford.”

The old gentleman had not hitherto ceased kicking his legs against the high stool, a custom which had become habitual. He stopped, however, on hearing this, and looked more keenly than ever at Owen.

“What proof have you got, boy, that your mother was once Susan Fluke?” he asked in a sharp tone.

“David Rowe, who is clerk to Mr Orlando Browne the lawyer, found the name in a book which had once been my grandmother’s, and left by her to my mother, called ‘Sturm’s Reflections.’”

“I should like to see the book,” said Mr Fluke, in a tone which showed more interest than he had hitherto exhibited.

“David Rowe has the book at Fenside, but I could get it sent to you, sir, if you wish to see it,” said Owen.

“I do wish to see it; I want proof of the strange story you tell me,” said the old man, taking another pinch of snuff. “And suppose it is true, what do you want of me?”

“I want to find employment, sir, and the means of supporting myself. I don’t wish to be a burden on Farmer Rowe, the only friend I have beside Jane Hayes, my old nurse.”

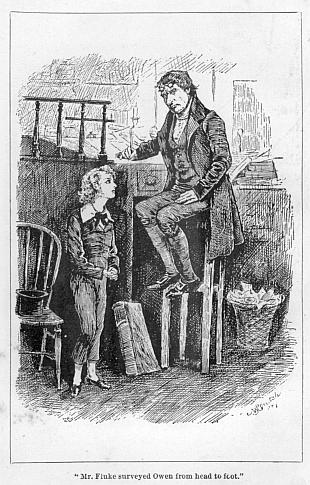

Mr Fluke surveyed Owen from head to foot. “What can such a boy as you do, except run errands, or sweep out the office?” he asked in a tone of contempt. “What do you happen to know? Can you write? Have you any knowledge of arithmetic?”

“Yes, sir,” said Owen, “I am tolerably well acquainted with quadratic equations; I have gone through the first six books of Euclid, and have begun trigonometry, but have not got very far. I am pretty well up in Latin. I have read Caesar and Virgil, and a little of Horace; and in Greek, the New Testament, Xenophon, and two plays of Aeschylus; and my father considered me well acquainted with English history and geography.”

“Umph! a prodigy of learning!” muttered the old gentleman. “Can you do the rule of three and sum up?—that’s more to the purpose. What sort of fist do you write? Can you do as well as this?” and he exhibited a crabbed scrawl barely legible.

“I hope that my writing would be more easily read than that, sir,” answered Owen. “I could do the rule of three several years ago, and am pretty correct at summing up.”

“Umph!” repeated the old gentleman, “if I take you at your word, I must set you down as a genius. I don’t know that the learning you boast of will be of much use to you in the world. If, however, I find the account I have just heard correct, I may perhaps give you a trial. I am not to be taken in by impostors, old or young; you will understand, therefore, that I make no promises. I am busy now and cannot spend more time on you, so you must go. I suppose that you did not come up here by yourself?”

“No, sir, John Howe, Farmer Rowe’s eldest son, accompanied me, and is waiting outside; if you cannot give me employment, he wants me to go back with him to Fenside.”

“Tell him to stay in town until I have seen the book, and have had time to look into the matter,” said Mr Fluke. “Where are you stopping, in case I may wish to send to you? But I am not likely to do that. Come again when you have got the book.”

“We are stopping at the ‘Green Dragon,’ Bishopsgate Street, sir,” said Owen.

“Well, write down your address and the name of your friend,” and Simon Fluke handed a pen to Owen, and placed a piece of paper on the desk before him. “Umph! a clear hand, more like a man’s than a boy’s,” muttered the old gentlemen to himself as he examined what Owen had written. “You may go now, and remember what I told you.”

Saying this, Mr Fluke turned round on his stool, and applied himself to his work without another parting word to Owen, who, making the best of his way through the office, hastened out at the door. He looked up and down the street, wondering whether John would have got tired and gone away, but John was too faithful a friend to do that. He had merely crossed over the street, keeping his eye on Paul Kelson, Fluke and Company’s office. Seeing Owen, John hastened over to meet him.

“Well, what news, Owen?” he asked, without uttering a word of complaint at the time he had been kept waiting.

Owen described his interview with Simon Fluke.

“Not very promising,” observed John; “I suspect that Simon Fluke’s heart is very like what David thought it might be, hard as a rock, or he would have shown more interest in you when he heard that you were Susan Fluke’s grandson. However, we will do as he asks, and send for the book, and in the meantime you and I’ll go and see this big city of London. There’s the Tower, and Exeter Change, the British Museum, Saint Paul’s, and Westminster Abbey, and other places I have heard speak of. The Tower is not far from here—we passed it as we came along; we will go and see that first.”

On their way, however, they began to feel very hungry, and were thankful to find an eating-house where they could satisfy their appetites. The fare was not of the most refined character, nor were the people who came in. Two or three, seeing at a glance that John was fresh from the country, offered to show him and his son the way about London.

“Maybe you’d like to take a glass for good fellowship,” said one of the men who addressed him.

But John, suspecting the object of the offer, declined it, as he did others subsequently made him, and taking Owen by the hand, he gladly got out of the neighbourhood. They made but a short visit to the Tower, as John was anxious to get back to the “Green Dragon,” that he might write to David for the book.

“We will show it to the suspicious old gentleman, but we must take care he does not keep it,” said John. “I don’t think, Owen, you must raise your hopes too high. If he gives you the cold shoulder, you will not be worse off than you were before, and you shall come back with me. You will not be left without friends while father, David, and I are alive, so cheer up whatever happens.”

John, who, although country-born and bred, had his wits about him, managed to see as many of the sights of London as he intended. Owen was much interested by all he saw, and the days passed quickly by. The important volume, which was, he hoped, to convince Simon Fluke of his relationship, safely arrived one evening, and he and John the following morning set off with it to Wapping. John insisted on remaining outside while Owen had his interview with Simon Fluke, and ascertained whether any employment was to be given him.

“If I find you are comfortably settled, then I shall go home happy in my mind,” said John; “if not, as I said before, you shall come back with me; I won’t leave you alone in this big city.”

Owen entered the office with the book in his hand. Mr Fluke was engaged in his private room. Mr Tarwig, the head clerk, got off his stool to speak to him, and had Owen put a proper value on this piece of condescension, he would have considered it a good sign.

“Sit down, my boy, the master will be out soon, and he has something to say to you,” said Mr Tarwig, pointing to a bench, and nodding to Owen, he returned to his seat. In a few minutes the door opened, and a fine-looking seafaring man, evidently the master of a ship, came out. As he passed by he gave a glance at Owen, who heard him addressed by Mr Tarwig as Captain Aggett. “What a pleasant look he has,” thought Owen; “I should like to be under him. I wonder if he can give me anything to do?” Mr Fluke put his head out directly afterwards, and seeing Owen, beckoned him in.

“Well, lad, have you got the book?” he asked.

Owen undid the parcel, and handed him the volume. The old man examined it minutely, but Owen could detect no change in his countenance.

“That’s my handwriting, there’s no doubt about it, written when I gave the book to my cousin Susan, as she was about to marry Henry Walford,” muttered Mr Fluke to himself. He was then silent for some time, forgetting, apparently, that any one was in the room. “Have you any books with the name of Walford in them?” he asked, fixing his keen glance on Owen; “that would be more clear proof that you are the person whom you say you are.”

“Yes, sir, I remember several of my mother’s books which she had before her marriage, and others which had belonged to my grandmother, with their names in them; I do not know, however, whether they can be recovered. A bookseller purchased the whole of them at the sale which took place at the vicarage, but perhaps he has not yet disposed of them.”

“Boy, the books must be got at any price,” exclaimed the old man, in an authoritative tone, like that of a person not accustomed to be contradicted. “Write to your friends, and tell them to buy them all up; I will send them a cheque for the amount. We must not let them go to the grocer’s to wrap up butter and cheese.”

“I will do as you desire, sir,” said Owen.

“I am inclined to believe the account you give of yourself, boy, and you shall have a trial,” said Mr Fluke; his manner was far less abrupt than it had hitherto been, and comparatively gentle. “Go to the outer office, I am busy now; Mr Tarwig will look after you, and tell me what he thinks.”

He went to the door, and summoned his head clerk.

“Try him,” said Mr Fluke, pointing to Owen.

“Come along with me,” said Mr Tarwig, and he made a sign to Owen to get up on a high stool, handing him, at the same time, the draft of a letter. “There, copy that.”

Owen transcribed it in a clear, regular hand, correcting two or three errors in spelling.

“Good,” said Mr Tarwig, as he glanced over it, perhaps not discovering the improvement in the latter respect. “Now cast up these figures,” and he handed him a long account.

Owen performed the work rapidly, and when checked by Mr Tarwig, it was found to be perfectly correct.

“Good,” said the head clerk; “you’ll do.”

He handed him several accounts in succession, and which required considerable calculation.

“Ah me!” exclaimed Mr Tarwig, and taking the papers he actually went across the office to show them to his immediate surbordinate, who looked round with a surprised glance at the young stranger.

What “Ah me!” meant Owen could not tell, but he judged that Mr Tarwig was satisfied with his performance. Owen had not forgotten John.

“A friend is waiting for me outside, sir,” he said; “if I am not wanted, I must rejoin him.”

“Stay and hear what Mr Fluke has got to say to you,” answered Mr Tarwig; “or go out and call your friend in, perhaps the master may have a word to say to him.”

Owen gladly did as he desired.

“I think they are pleased with me,” he said to John; “and I understand that Mr Fluke wants to speak to you, I suppose it is about getting back my mother’s books,” and Owen related what had occurred.

“A good sign,” said John. “Things look brighter than I expected they would, but we must not raise our hopes too high.”

Owen ushered John into the office, feeling almost at home there already. In a short time Owen and John were summoned into Mr Fluke’s room. John was not prepossessed by that worthy’s manner.

“You are John Rowe, I understand,” he began. “Believing this boy’s account of himself I am going to give him a trial; if he behaves well, he will rise in this office, for there is no doubt that he possesses the talents he boasts of. He shall come and stop at my house. Go and get his things and bring them here, for I shall take him home with me. Now listen, Mr John Rowe, I want you to perform a commission for me. Here is a cheque, you can get it cashed in the country. Buy up all the books with the name of Walford in them which were sold at the Fenside Vicarage sale.”

As he spoke, he handed a cheque for 10 pounds to John, adding, “Do not tell the bookseller why you want them, or he will raise the price. Buy them in your own name. If this sum is not sufficient, let me know; should it be more than you require, take it to defray the expenses you have been at on the boy’s account.”

John thanked Mr Fluke, and promised to carry out his wishes, highly pleased at what he considered Owen’s good fortune.

Owen, however, felt somewhat disappointed at not being able to spend another evening with his friend.

From Mr Fluke’s manner, John saw that it was time to take his departure, and Owen followed him to the door. John had to return with Owen’s box of clothes, but there probably would not then be time for any conversation.

Owen sent many grateful messages to Fenside Farm. “I hope that Mr Fluke will let me go down and see you sometimes,” he added, “for I never can forget all the kindness you, your father, and David have shown me, and your mother and sisters.”

“Well, if you are not happy here, mind you must tell us so, and you shall ever be welcome at Fenside,” said John, as they parted.

Chapter Three.

John Rowe brought Owen’s little trunk all the way from the “Green Dragon” on his own broad shoulders, and deposited it at Paul Kelson, Fluke and Company’s office. Having done so he hurried off, not wishing to be thanked, and considering there was not much advantage to be gained by another parting with his young friend. Owen, however, was disappointed, when he found that his box had arrived, that he had missed seeing John.

The instant five o’clock struck, Simon Fluke came out of his office, and directing one of his porters to bring along the boy’s trunk, took Owen by the hand, and having tucked a thick cotton umbrella under his other arm, led him out. They trudged along through numerous dirty streets and alleys, teeming with a ragged and unkempt population, and redolent of unsavoury odours, until they emerged into a wide thoroughfare.

“Call a coach, boy!” said Mr Fluke, the first words he had spoken since he had left the office. “How am I to do that, sir?” asked Owen.

“Shout ‘Coach,’ and make a sign with your hand to the first you see.”

“Will the coach come up, sir, if I call it?” asked Owen.

“Of course, if the driver hears you,” answered Mr Fluke in a sharp tone. “The boy may be a good arithmetician, but he knows nothing of London life,” he muttered to himself. “To be sure, how should he? But he must learn—he will in time, I suppose; I once knew no more than he does.”

Owen saw several coaches passing, and he shouted to them at the top of his voice, but no one took the slightest notice of him. At length the driver of a tumble-down looking vehicle, with a superb coat of arms on the panel, made a signal in return and drew up near the pavement.

“You will know how to call a coach in future,” said Mr Fluke. “Step in.”

The porter, who had been watching proceedings, not having ventured to interfere by assisting Owen, put the box in, after Mr Fluke had taken his seat, and then told the coachman where to drive to. The latter, applying his whip to the flanks of his horses, made them trot off, for a few minutes, at a much faster rate than they were accustomed to move at. They soon, however, resumed their usual slow pace, and not until Mr Fluke put his head out of the window, and shouted, “Are you going to sleep, man?” did he again make use of his whip.

“You must learn to find your way on foot, boy,” said Mr Fluke. “I do not take a coach every day; it would be setting a bad example. I never yet drove up to the counting-house, nor drove away in one, since I became a partner of old Paul Kelson, and he, it is my belief, never got into one in his life, until he was taken home in a fit just before his death.”

Owen thought he should have great difficulty in finding his way through all those streets, but he made no remark on the subject, determining to note the turnings as carefully as he could, should he accompany Mr Fluke the next morning back to Wapping.

The coach drove on and on; Mr Fluke was evidently not given to loquacity, and Owen had plenty of time to indulge in his own reflections. He wondered what sort of place his newly found relative was taking him to. He had not been prepossessed with the appearance of the office, and he concluded that Mr Fluke’s dwelling-house would somewhat resemble it. The coach at last emerged from the crowded streets into a region of trees and hedge-rows, and in a short time stopped in front of an old-fashioned red brick house, with a high wall apparently surrounding a garden behind it. At that moment the door of the house opened, and a tall thin female in a mob cap appeared.

“Bless me!” she exclaimed, as she advanced across the narrow space between the gate and the doorway; “and so he has come!”

She eyed Owen narrowly as she spoke. Simon Fluke declining her help as he stepped out, pointed to Owen’s box, which the coachman, who had got down from his seat, handed to her. Mr Fluke having paid the fare, about which there was no demur, he knowing the distance to an inch, led the way into the house, followed by Owen, the old woman, carrying his box, bringing up the rear.

“I have brought him, Kezia, as I said I possibly might. Do you look after him; let us have supper in a quarter of an hour, for I am hungry, and the boy I am sure is.”

The house wore a greater air of comfort than Owen expected to find. In the oak panelled parlour into which Mr Fluke led him a cheerful fire burned brightly, although the spring was well advanced, while a white cloth was spread ready for supper.

“Now come into the garden,” said his host, who had entered the room, apparently merely to deposit his umbrella. A glass door opened out on some steps which led down into a large garden, laid out in beds in which bloomed a number of beautiful flowers, such as Owen had never before seen in his life, and on one side, extending along the wall, was a large greenhouse.

“Do you know what those are, boy?” asked Mr Fluke. “Every one of those flowers are worth a hundred times its weight in gold. They are all choice and rare tulips, I may say the choicest and rarest in the kingdom. I prize them above precious stones, for what ruby or sapphire can be compared to them for beauty and elegance? You will learn in time to appreciate them, whatever you do now.”

“I am sure I shall, and I think they are very beautiful!” said Owen.

Mr Fluke made up for his former silence by expatiating on the perfections of his favourites. While the old gentleman was going the round of his flower beds, stooping down with his hands behind him, to admire, as if to avoid the temptation of touching the rich blossoms, a person approached, who, from his green apron, his general costume, and the wheelbarrow he trundled full of tools before him, was easily recognised as the gardener. He could not have been much younger than his master, but was still strong and hearty.

“They are doing well, Joseph; we shall have some more in bloom in a day or two,” observed Mr Fluke.

“Yes, praise the Lord, the weather has been propitious and rewarded the care we have bestowed on His handiworks,” answered the old gardener. “I am in hopes that the last bulbs the Dutch skipper Captain Van Tronk brought over will soon be above ground, and they will not be long after that coming into bloom.”

Mr Fluke, having had some confidential conversation with his gardener on the subject of his bulbs, and given him various directions, it by that time growing dusk, summoned Owen to return to the house.

“A pretty long quarter of an hour you’ve been,” exclaimed Kezia to her master, as he re-entered; “it’s always so when you get talking to my man Joseph Crump about the tulips. If the rump steak is over-done it’s not my fault.”

Mr Fluke made no reply, except by humbly asking for his slippers, which Kezia having brought, she assisted him in taking off his shoes.

“There, go in both of you, and you shall have supper soon,” she exclaimed in an authoritative tone, and Mr Fluke shuffled into his parlour.

Owen remarked, that though Mr Fluke ruled supreme in his counting-house, there was another here to whom he seemed to yield implicit obedience. Not a word of remonstrance did he utter at whatever Kezia told him to do; it was, however, pretty evident that whatever she did order, was to his advantage. Probably, had she not assumed so determined a manner, she would have failed to possess the influence she exerted over her master. He made a sign to Owen to take a seat opposite him on one side of the fire. Mrs Kezia Crump, as she was generally designated outside the house, placed an ample supper on the board—in later days it would have been called a dinner—two basins of soup, some excellently cooked rump steak, and an apple tart of goodly proportions.

“I know boys like apple tart, and you may help him as often as he asks for it,” she remarked as she put the latter dish on the table.

A single glass of ale was placed by Mr Fluke’s side. Owen declined taking any, for he had never drank anything stronger than water.

“Very right and wise, boy,” observed his host in an approving tone. “You are the better without what you don’t require. I never drank a glass of ale till I was fifty, and might have refrained ten years longer with advantage, but Kezia insisted that I should take a glass at supper, and for the sake of quiet I did so. Kezia is not a person who will stand contradiction. She is sensible though. Could not have endured her if she were not. But she is not equal to her husband Joseph. The one rules supreme in the house, the other in the garden. You’ve seen what Joseph Crump has done there. What do you think of my tulips? I am indebted to Joseph for them. Beautiful! glorious! magnificent! Are they not?”

Owen nodded his head in assent.

“Their worth cannot be told. Once upon a time one of those splendid bulbs would have fetched thousands. That was nearly two centuries ago, that events repeat themselves, and, for what we can tell, that time may come round again, then, Owen, I shall be the richest man in England. No one possesses tulips equal to mine.”

“Indeed,” said Owen; and he thought to himself, when at Wapping this old man’s whole soul seems to be absorbed in business, while out here all his thoughts appear to be occupied in the cultivation of tulips. How could he have been first led to admire them? Before many minutes were over Mr Fluke answered the question himself.

“Twenty years ago I scarcely knew that such a flower as a tulip existed, when one day going on board a Dutch vessel I saw a flower growing in a pot in the cabin. I was struck by the beauty of its form—its brilliant colours. I learned its name. I was seized with the desire to possess it. I bought it of the skipper. The next voyage he brought me over a number of bulbs. I wanted something to engage my thoughts, and from that day forward I became fonder and fonder of tulips.”

The evening was passed more pleasantly than Owen had anticipated. Mr Fluke, indeed, appeared to be an altogether different person to what he had seemed at his first interview with his young relative.

“Boys want more sleep than old men,” said Mr Fluke, pulling out his turnip-like watch.

“Here, Kezia!” he shouted, “come and take him off to bed. She will look after you,” he added, nodding to Owen; “you must do as she bids you though.”

The old man did not even put out a finger as Owen advanced to take his hand to wish him good night, but said, pointing to Kezia, who just then entered the room, “There she is; go with her.”

“How impatient you are, Mr Fluke, this evening,” exclaimed the dame. “In half a minute more I should have been here, and saved you from bawling yourself hoarse. I know how the time goes, I should think, at my age.”

Her master made no reply, but merely attempted to whistle, while Kezia, turning to Owen, said, “Come along, my child.” She led him up an oaken staircase into a room of fair proportions, in which, although the furniture was of a sombre description, there stood a neat dimity-curtained bed.

“There, say your prayers and go to bed,” said Kezia. “I will come in presently to tuck you up, and to take away your candle.”

“Thank you,” said Owen; “you are indeed very kind.”

“No, I ain’t kind, I just do what I think right,” answered the dame, who, if she did not pride herself on being an original, evidently was one. “The old man told me that you had lost your parents, and you’ll feel the want of some one to look after you. I once had a little boy myself. He grew to be bigger than you are, but he was never strong or hearty. He used to go to the office every day of his life, hot or cold, rain or sunshine, wet through or dry; he died from over work. It was more my fault than the old man’s though, so I don’t blame him, for I ought to have kept the poor boy in bed instead of letting him go out and get wet through and through as he did time after time; but I’ll take care that it is not your fate,” and Mrs Kezia sighed. “I must not stand prating here though.”

She came in according to her promise. Having carefully tucked him up, she stooped down and kissed his brow.

“Thank you, thank you,” said Owen. The tears rose to his eyes, and he felt more happy than he could have supposed possible.

“Have you said your prayers?” asked Kezia.

“Yes, I never forget to do that,” answered Owen.

“Good night, my child,” she said; “the Lord watch over you and keep you.” Taking the light she left him.

His slumbers were peaceful. Kezia took care to call him betimes in the morning.

“The old man is off early, and he would not be pleased if you were not ready to start with him,” she said.

When Owen came down he saw Mr Fluke in the garden, holding a conference with Joseph. He presently came in to breakfast, which was as ample a meal as the supper had been.

Kezia put a small paper parcel into Owen’s pocket.

“That will be for your dinner,” she said; “you’ll want something before you come back, and you’ll get nothing there fit to eat. It’s as bad to let growing boys starve as to leave plants without water, as Joseph Crump says,” and she looked hard at her master.

“Kezia’s a wonderful woman,” remarked Mr Fluke, after she had left the room. “I have a great respect for her, as you see. She is worth her weight in gold; she keeps everything in order, her husband and me to boot. Years ago, before she came to me, I had a large black tom cat; he was somewhat of a pet, and as I kept him in order, he always behaved properly in my presence. He had, however, a great hatred of all strangers, especially of the woman kind, and no female beggar ever came to the door but he went out and arched his back, and spat and screeched and hissed at her until she took her departure. When I engaged Kezia and Joseph Crump, I thought Tom would understand that they were inmates of the house, and behave properly. But the very first time Kezia went upstairs, after she and her husband had installed themselves in their room below, there was Tom standing on the landing with his back up lashing his tail, and making a most hideous noise. Most women would have turned round and run down again, or perhaps tumbled over and broken their necks; but Kezia advanced, keeping her eye on Tom, and as he sprang at her, she guessing that he would do so, seized him by the neck and held him at arm’s length until every particle of breath was squeezed out of his body. ‘There,’ she exclaimed, as she threw him over the banisters, ‘two cannot rule in one house,’ and she went upstairs and commenced her work. When I arrived at home, and saw Tom lying dead on the floor, I asked who had killed the cat. ‘I killed him,’ answered Kezia, and she then told me how it had happened. ‘If you think I was wrong, and don’t like it, give me a month’s warning; I am ready to go,’ she said. I didn’t say a word in reply, and I tell you I have a greater respect for that woman than for any of her sex, and maybe I have more fear of her than I ever had of old Tom, who, once or twice, until I taught him better manners, had shown his evil disposition even to me.”

“Mrs Kezia is a very kind, good woman,” observed Owen; “I am sure of that.”

“She’s a wise woman,” answered Mr Fluke; “if she were not, she could not manage my house. Now, boy, finish your breakfast, and be prepared to start with me in ten minutes.”

Owen lost no time in getting ready.

“Come along,” he heard Mr Fluke shout; and hurrying out of the room where he was waiting, he found that gentleman descending the steps.

“Stay, you have forgotten your umbrella. What are you thinking about, Mr Fluke, this morning?” exclaimed Kezia, handing it to him as she spoke.

Mr Fluke tucked it under his arm, and taking Owen by the hand they set off.

“Do not dawdle on the way back, and take the coach if it rains hard,” cried Kezia, shouting after them.

They walked the whole distance at a fair pace, which Owen could easily maintain. He was glad of the exercise, although he did not like passing through the narrow and dirty streets at the further end of his walk, where squalor and wretchedness appeared on every side. Mr Fluke being so used to it, was not moved by what they beheld.

“Surely something ought to be done for these poor people,” thought Owen. “If my father had been here, he would have spent every hour of the day in visiting among them, and trying to relieve their distress.” Owen was not aware that much of the misery he witnessed arose from the drunken and dissipated habits of the husbands, and but too often of the wives also.

On their arrival at the office, which had just before been opened, Mr Fluke handed Owen over to Mr Tarwig, who at once set him to work. There was plenty to do. Two clerks had recently left; their places had not been supplied. Owen was therefore kept hard at work the greater part of the day, and a short time only allowed him for eating the dinner which Kezia Crump had provided. He was better off, however, than most of the clerks, who had only a piece of bread to eat if they remained in the office, or if they went out, had to take a very hurried, ill-dressed meal at a cookshop. Some, indeed, were tempted to imbibe instead a glass of rum or gin, thus commencing a bad habit, which increased on those who indulged in it.

The weather was fine, and Owen walked backwards and forwards every day with Mr Fluke. One day a box arrived marked private, and addressed to S. Fluke, Esquire. On glancing at the contents, Mr Fluke had it again closed, and that evening he went away earlier than usual, a porter carrying the box to the nearest coach-stand. Owen was saved his long walk, which, as the weather grew warmer, was sometimes fatiguing. The box, which had been carried into the parlour was again opened by Kezia and Owen, who begged leave to help her. After supper Mr Fluke, who appeared for the time to have forgotten his tulips, employed himself in examining the contents, which proved to be the books he had directed John Rowe to purchase for him.

“Your friend has performed his commission well,” he said, as he looked over book after book. “I recognise Susan’s handwriting—your grandmother, I mean; it must seem a long time ago to you, but to me it is as yesterday. I had not from the first moment any doubt as to your being Susan Fluke’s grandchild, but I am now convinced of it. You will find more interesting reading in these books than in any I possess, and you are welcome to make use of them.”

Owen accepted the offer, and for many an evening afterwards pored over in succession most of the well-remembered volumes.

Mr Fluke, the next morning, on his way to the office, called at an upholsterer’s, and purchased a dark oak bookcase, which he ordered to be sent home immediately. On his return home, with evident satisfaction he arranged the books within it.

Owen had every reason to be thankful for the kind treatment he received, but the life he spent was a dull one. In reply to letters he wrote to his friends at Fenside they warmly congratulated him on his good fortune.

Day after day he went to the office, where he was kept hard at work from the moment of his arrival until the closing hour, for, as it was found that he was more exact in his calculations than any one else, and as he wrote a hand equal to the best, he had always plenty to do, a few minutes only were allowed him to take his frugal dinner. Frequently also he was unable to enjoy even a few mouthfuls of such fresh air as Wapping could afford.

Generally he walked in and out with Mr Fluke, but he sometimes had to go alone. He was soon able to find his way without difficulty, but he never had an opportunity of going in other directions, so that all he knew of London was the little he saw of it while visiting the sights with John Rowe. Whatever the weather, he had to trudge to and fro. Several times he got wet through, and had to sit all day in his damp clothes.

Kezia suggested to Mr Fluke that the boy required a fresh suit—“His own is threadbare, and would be in holes if I did not darn it up at nights,” she observed.

“It’s good enough for the office, and what more does he want?” answered Mr Fluke. “Why, I have worn my suit well-nigh ten years, and it is as good as ever. Who finds fault with my coat, I should like to know?”

“The boy wants a thick overcoat, at all events,” continued Kezia, who had no intention of letting the matter drop. “If you don’t get him one, I will. He will catch his death of cold one of these days. He is not looking half as well as he did when he came, although he has grown wonderfully; he will, indeed, soon be too big for his jacket and trousers, if they do not come to pieces first.”

“Do as you choose, Kezia,” said Mr Fluke. “You always will have your own way, so there’s no use contradicting you.”

“Then I’ll get him a fresh suit and a topcoat before many hours are over, and not a day too soon either,” answered Kezia, rubbing her hands in the way she always did when well satisfied with herself or with things in general.

“No! no!” almost shrieked Mr Fluke. “If he gets a topcoat that will hide the threadbare jacket you talk of, and that will serve well enough in the office for a year to come, or more.”

“You said, Mr Fluke, that I was to do as I chose,” exclaimed Kezia, looking her master in the face. “You are a man of your word, and always have been from your youth upwards, and I, for one, will not let you break it in your old age. I choose to get Owen a new suit and a topcoat, so say no more about the matter.”

The next morning Kezia appeared in her bonnet and shawl as Owen was about to start.

“Let the old man go on first, I am going with you,” she said.

Mr Fluke was never a moment behind time in starting from home, and he knew that Owen could easily overtake him.

Kezia accompanied Owen to Mr Snipton’s, a respectable tailor in the City, where she ordered an entire suit and a thoroughly comfortable topcoat.

“Take his measure,” she said, “and allow for his growing; remember Simon Fluke will pay for the things.”

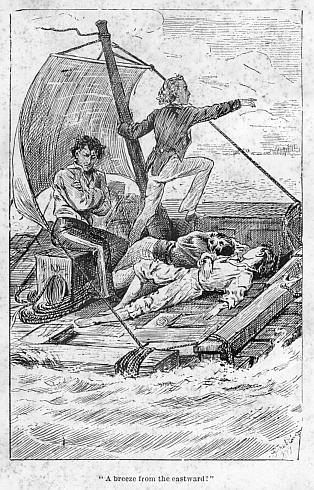

Mr Snipton did as he was directed, and while Owen hurried on to overtake Mr Fluke before he reached the office, Kezia returned home. Owen had, however, to wear his threadbare jacket for some days longer. During this period he was returning one evening, and was crossing Bishopsgate Street, when a hooded gig, or cab, as it was called, containing two young gentlemen—one of whom, dressed in a naval uniform, was driving—came dashing along at a rapid rate. It was in a narrow part of the street, of which a waggon and some other vehicles occupied a considerable portion. In attempting to pass between the waggon and pavement the cab was driven against the hinder wheel of the ponderous waggon, which was going in the same direction that it was—towards the Bank. The natural consequence ensued—the horse came down, and both the young gentlemen were thrown out, one narrowly escaping falling under the wheel of the waggon, while the tiger behind, whose head struck against the hood, fell off stunned. Owen ran forward to render what assistance he could.

“Go to the horse’s head, boy!” exclaimed the elder of the gentlemen, addressing Owen in an imperious tone, while he was picking himself up. “Reginald, are you hurt?”

“Not much,” was the answer of the younger, who began swearing in no measured terms at the waggoner for not keeping out of the way, and ordering him to stop. The latter, however, taking no notice of this, went on. “They got the worst of it this time,” he muttered. “Better that than to have run over an old woman, as I see’d just such a pair as they do not long ago.”

A fresh volley of abuse uttered by the young naval officer followed the retreating waggoner.

“Come, Reginald, don’t waste your breath on the rascal,” cried the elder gentleman. “I’ll help the boy to hold down the horse, while you undo the traces. What’s become of Cato?”

“Here I, my Lord,” said the black tiger, who, having partially recovered, now came hobbling up.

Owen, in the meantime, had been using every exertion to keep down the spirited horse, until the harness, detached from the cab, would allow the animal to rise without injuring itself. Several persons, mostly idle men and women, instead of coming forward to assist, stood by, amused at the disaster which had occurred to the gentlemen.

“Had but the young cove kept a decent tongue in his head plenty would have been ready to help him,” remarked one of the bystanders.

The black boy seemed somewhat afraid of the horse, and having scarcely recovered was of no use. The gentlemen, therefore, had to depend on their own exertions, aided by Owen.

The one called Reginald, when once he set to work, quickly got the harness unstrapped.

“Here, Arlingford, you take the horse’s head, and let him get up. Out of the way, boy, or he’ll be over you,” he shouted to Owen.

The horse, hitherto held down by Owen, rose to its feet. It took some time before the eldest of the young men, by patting its neck and speaking soothingly, could quiet the animal sufficiently to be again put into the cab. Owen assisted in buckling up the harness, while the black tiger, now recovered, came and held the horse.

“Have you got a coin about you of some kind, Arlingford?” asked the naval officer. “If you have, chuck it to the young fellow.”

Owen did not hear this remark.

“Here, boy,” cried the elder, putting half-a-crown into Owen’s hand; “just take this.”

“No, thank you, sir,” answered Owen, returning the money. “I am happy to have been of any service. I did not think of a reward.”

“Take it, stupid boy,” said Reginald.

Owen persisted in declining, and turned away.

“A proud young jackanapes! What is he thinking about?” exclaimed Reginald, who spoke loud enough for Owen to hear him.

“Here, I say, boy, don’t be a fool, take this,” and Reginald pitched the coin at Owen, who, however, not stopping to pick it up, walked on. As may be supposed, a scramble immediately ensued among the mob to obtain possession of the coin, until, shoving at each other, three or four rolled over against the horse. The effect of this was to make the animal set off at a rate which it required the utmost exertions of the driver to control. Indeed the cab nearly met with another accident before it had proceeded many yards.

Owen had remarked a coronet on the cab. “Can those possibly be young noblemen who made use of such coarse language, and who appear to be so utterly devoid of right feeling?” he thought to himself. “I hope that I shall not meet them again; but I think I should remember them, especially the youngest, who had on a naval uniform. His being a sailor will account for the activity he showed in unbuckling the harness.”

Owen gave an account of the incident to Mrs Kezia.

“That is like you, Owen,” she said. “Do what is right without hope of fee or reward. I am afraid that the old man does not give you much of either. What salary are you getting?”

“I have received nothing as yet; nor has Mr Fluke promised me a salary,” answered Owen. “I conclude that he considers it sufficient to afford me board and lodging, and to teach me the business. I should not think of asking for more.”

“And you’ll not get it until you do,” observed Mrs Kezia. “I’ll see about that one of these days.”

“Pray do not speak to Mr Fluke,” exclaimed Owen, earnestly; “I am perfectly content, and I am sure that I ought not to think of asking for a salary. If he is good enough to pay for the clothes you have ordered, I shall be more than satisfied, even were I to work even harder than I do.”

Mr Fluke, however, grumbled, and looked quite angry at Owen, when he appeared in his new suit. Mrs Kezia had been insisting, in her usual style, that the boy required new shoes, a hat, and underclothing.

“You’ll be the ruin of me with your extravagant notions, Kezia,” exclaimed Mr Fluke; “you’ll spoil the boy. How can you ever expect him to learn economy?”

He, notwithstanding, gave Mrs Kezia the sum she demanded.

Had it not been for her, Owen would probably have had to wear his clothes into rags. Mr Fluke would certainly not have remarked their tattered condition.

Notwithstanding all Kezia’s care, however, Owen’s health did not mend. Months went by, he was kept as hard at work as ever.

Kezia expostulated. At last Mr Fluke agreed to give him some work in the open air.

“I’ll send him on board the ships in the river; that will do him good perhaps.”

The very next day Owen was despatched with a letter on business to Captain Aggett of the ship “Druid,” then discharging cargo in the Thames.

Owen had seen Captain Aggett at the office; he was a tall, fine-looking man, with a pleasant expression of countenance. He recognised Owen as he came on board.

“Stop and have some dinner, my boy,” he said; “the steward is just going to bring it in.”

Owen, being very hungry, was glad to accept the invitation, and Captain Aggett himself declared that he could not write an answer until he had had something to eat. Possibly he said this that Owen might have a legitimate excuse for his delay. The captain had a good deal of conversation with Owen, with whom he seemed highly pleased. He took him over the ship, and showed him his nautical instruments, which Owen said he had never seen, although he had read about them, and knew their use.

“What! have you learned navigation?” asked Captain Aggett.

“I am acquainted with the principles, and could very soon learn it, I believe, if I had a book especially explaining the subject,” answered Owen.

Captain Aggett handed one to him, telling him to take it home and study it.

“Is this the first time you have been on board a ship?” asked the captain.

“Yes, sir; for since I came to London I never have had time, having always had work to do in the office,” answered Owen.

“How long have you been there?” asked the captain, who remarked that Owen had a cough, and looked very pale.

“Rather more than a year, sir.”

“Not a very healthy life for a lad accustomed to the country. A sea trip would do you good. Would you like to make one?”

“Very much, if Mr Fluke would allow me,” answered Owen. “I should not wish to do anything of which he might not approve.”

“I’ll see about it, youngster,” said Captain Aggett.

Although Owen was sent on several trips of the same description to other vessels, he was still kept too constantly at work in the office to benefit much by them.

He naturally told Kezia of his visit to Captain Aggett, and of the invitation he had received.

“Although I should be very sorry to have you go away from here, Owen, I am sure that the captain is right. It is just what you want; a sea voyage would set you up, and make a man of you, and if you remain in the office you’ll grow into just such another withered thing as the old man. I’ll speak to him, and tell him, if he wants to keep you alive and well, he must let you take a voyage with the good captain. I have heard of him, and Mr Fluke has a great respect for him, I know.”

Mrs Kezia did not fail to introduce the subject in her usual manner. Mr Fluke would not hear of it.

“Nonsense,” he answered, “the boy does very well; he can walk to and from the office, and eats his meals.”

“He does not eat one-half what he used to do,” answered Kezia; “he is growing paler and paler every day. He has a nasty cough, and you will have him in his grave before long if you don’t take care.”

“Pooh! pooh!” answered Mr Fluke. “Boys don’t die so easily as that.” He turned away his head to avoid Kezia’s glance.

She did not let the matter drop, however. A fortnight or more had passed by. Mr Fluke had missed one of his favourite tulips, which grew in a flower-pot.

On inquiring for it of Joseph: “It’s all safe,” was the answer, “I’m trying an experiment with it.”

Whenever Mr Fluke asked about the tulip, he always received the same reply: “We shall see how it gets on in a few days.” At length one afternoon when he came home, somewhat to his surprise, Kezia appeared in the garden.

“What about that tulip, Joseph, which master was asking for?” she said.

“Should you like to see it, sir?” asked Joseph.

“Of course I should,” answered Mr Fluke, expecting to see the flower greatly improved in size and beauty.

“I told Joseph to put it in the tool-house, just to see how it looks after being shut up in the dark without air,” said Kezia in her most determined manner.

“In the tool-house!” exclaimed Mr Fluke. “What in the world made you put it there, Joseph?”

“Kezia bade me, sir, and you know I dare not disobey her,” answered Joseph, demurely.

“And I bade him just for the reason I said,” exclaimed Kezia.

“Let us see it by all means,” cried Mr Fluke, hastening in the direction of the tool-house, which was in a corner of the garden on the north side, out of sight.

Kezia stalked on before her master and her husband. She entered first, and came out with a flower-pot in her hand. The tulip, instead of having gained in size and beauty, looked withered, and its once proud head hung down, its colours sadly faded.

“There,” she exclaimed; “that’s just like our Owen. You shut him up in your dark office, and expect him to grow up strong and healthy, with the same bright complexion he had when he came to us. Some natures will stand it, but his, it is very certain, cannot. Maybe, if we put this tulip in the sun and give it air and water, it will recover; and so may he, if you allow him to enjoy the fresh breezes, and the pure air of the sea. Otherwise, as I have told you, all your kindness and the good intentions you talk of to advance him in life will come to nothing. I repeat it, Mr Fluke, Owen Hartley will be in his grave before another year is out if he has to breathe for eight hours or more every day the close atmosphere of Kelson, Fluke and Company’s office.”

Mr Fluke walked away without answering Kezia, and kept pacing up and down the garden in a state of perturbation very unusual for him.

Owen had been kept at the office, and did not get home until late. He observed that Mr Fluke was watching him narrowly.

“Yes, you do look somewhat pale,” said the old gentleman; “I see it now. How do you feel, boy?”

“Very well, sir,” answered Owen, naturally enough; “only a little tired now and then. It is my own fault, I suppose, that I do not sleep so soundly as I used to do, and do not care much about my food.”