“What’s ’is business?”

“’E’s a taxidermist.”

“Oh, is ’e? Well, ’e seems to ’ave done better out of it than I ’ave.”

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 158, May 12, 1920

Author: Various

Editor: Owen Seaman

Release Date: December 31, 2007 [eBook #24095]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI, VOL. 158, MAY 12, 1920***

We are pleased to note that the King’s yacht Britannia is about again after being laid up since August, 1914.

Smoking and chatting periods have been introduced in some Massachusetts factories. Extremists in this country complain that, while this system may be all right, there is just the danger that working periods might also be introduced.

We are pleased to report that the eclipse of the moon on May 3rd passed off without any serious hitch. This speaks well for the police arrangements.

“Audiences at the music-halls,” writes an actor to the Press, “are more difficult to move on Saturdays than on other days.” This is not our experience. On a Saturday we have often withdrawn without any pressure after the first turn or two.

Sir L. Worthington Evans, says a contemporary, has been asked to investigate the mutton glut. What is wanted, we understand, is more glutton and less mutt.

Mme. Landru, the wife of the Parisian “Bluebeard,” has been granted a divorce. We gather that there is something or other about her husband which made their tastes incompatible.

It appears that Mr. Jerry McVeagh is of the opinion that the Home Rule Bill is quite all right except where it applies to Ireland.

A visit to the Royal Academy this year again encourages us to believe that, though we may be a bad nation, we are not so bad as we are painted.

According to a morning paper a commercial traveller who became violently ill in the Strand was found to have a small feather stuck in the lower part of the throat. If people will eat fresh eggs in restaurants they must be prepared to put up with the consequences.

The report that no inconvenience was experienced by any of the passengers in the South London train which collided with a stationary goods-engine now turns out to be incorrect. It transpires that a flapper complains that she dropped two stitches in her jumper as a result of the shock.

A water-spaniel was responsible last week for the overturning of a motor-car driven by a Superintendent of the Police near Norton Village in Hertfordshire. We understand that the dog has had his licence endorsed for reckless walking.

According to a Manchester paper a new tram, while being tested, jumped the lines and collided with a lamp-post. It is hoped that, when it grows more accustomed to street noises, it will get over this tendency to nervous excitement.

A serious set-back to journalism is reported from South Africa. It appears that the Army aviator who flew from England to his home at Johannesburg, after an absence of four and a half years, deliberately arranged to see his parents before being interviewed by reporters.

In a London Police Court the other day a defendant stated that he was so ashamed of his crime that he purchased a revolver with the intention of shooting himself. On second thoughts he let himself off with a caution.

Apparently the clothing of the Royal Air Force is not yet complete. Large headings announcing an R.A.F. Divorce Suit appeared in several papers recently, although its design and colouring were not mentioned.

Builders have been notified that the prices of wall-paper are to be raised forty to fifty per cent. In view of the vital part played by the wall-paper in the construction of the modern house, the announcement has caused widespread consternation among building contractors.

An American contemporary inquires why Germany cannot settle down. A greater difficulty appears to be her inability to settle up.

A shop at Twickenham bears the notice, “Shaving while you wait.” This obviates the inconvenience of leaving one’s chin at the barber’s overnight.

“Life and property,” writes a correspondent, “are as safe in Hungary to-day as they are in England.” It should be borne in mind that there is usually a motive underlying these alarmist reports.

“It is ten days,” writes a naturalist, “since I heard the unmistakable ‘Cuck, cuck, cuck’ of the newly-arrived cuckoo at Hampstead.” Not to be confused with the “Cook, cook, cook!” of the newly-married housewife at Tooting.

A weekly paper has an article entitled “The Lost Haggis.” We always have our initials put on a haggis with marking ink before despatching it to be tailor-pressed.

At the annual meeting of the National Federation of Fish-fryers the President asked whether it was not possible to make fried fish shops more attractive. It appears that no serious attempt has yet been made to discover a fish that gives off an aroma of violets when fried.

The Directors of the Underground offer a prize of twenty pounds to their most polite employee. We have always felt that the conductor who pushes you off a crowded train might at least raise his hat to you as he moves out of the station.

After considering the Budget very carefully some people are veering round to the theory that we didn’t win the War, but just bought it.

“What’s ’is business?”

“’E’s a taxidermist.”

“Oh, is ’e? Well, ’e seems to ’ave done better out of it than I ’ave.”

“Wanted, Youth of sixteen for one of the healthiest jobs in the world, most of the time spent basking in the sun, listening to skylarks and throstles; wages 35s. guaranteed to smart youth. Lots of weaklings have been set on their feet and prepared to face the world at this situation.”—Provincial Paper.

Rest from your work, awhile, my son,

And let a mug of beer replace

The moisture—sign of duty done—

That oozes from your honest face;

Your tale of bricks,

A long hour’s task, already totals 6.

Our goose that lays the bars of gold

Must not incur too big a strain;

Nor need you, as I think, be told

To keep a check on hand and brain,

Lest you exceed

Your Union’s limit in respect of speed.

For homes a homeless people cries,

But you’ve a principle at stake;

Though fellow-workers, lodged in styes,

Appeal to you for Labour’s sake

To fill their lack,

Shall true bricklayers waive their Right to Slack?

Never! You’ll lay what bricks you choose,

And let the others waste their breath,

These myriads, ranged in weary queues,

Who desperately quote Macbeth:—

“Lay on, Macduff,

And damned be he that first cries ‘Hold, enough’!”

Your high profession stands apart;

By years of toil you’ve learned the trick

(Like Pheidias with his plastic art)

Of slapping mortar on a brick;

Touched too the summit

Of science with your lore of line and plummet.

And none may join your sacred Guild,

Save only graduates (so to speak),

Experts with hod and trowel, skilled

In the finesse of pure technique:

And that is why

No rude untutored soldier need apply.

I have been in the Army for over five years; I have wallowed in Flanders mud; I have killed thousands of Huns with my own hand; I have seen my friends resume the habiliment of gentlemen and retire to a life of luxury and ease; and yet I am still in the Army.

I am informed that I am indispensable and that, although I shall be allowed to go in due course, the fate of the nation depends on my sticking to my job for a short time more. It would be against the best interests of discipline for me to tell you what my job is.

Last week I yearned for a civilian life and decided that not only would I leave the Army but immediately and in good style.

I laid my plans accordingly and proceeded to Mr. Nathan’s. There for the expenditure of a few shillings I purchased the necessary material for my guile.

I retired to my office, that is the desk that I sit at in a room with two other officers, and I armed myself with a file which would act as a passport to the Assistant of a Great Man, who in turn is Assistant to a Very Great Man. They all reside at the War Office. I went there and was conducted to the Assistant of the Great Man. Everything was proceeding according to plan.

I found him, after the manner of Assistants, working hard. He did not look up, so I laid my file before him. It was entitled “Demobilization, letters concerning,” and this was followed by a long number divided up by several strokes. Within the file were some letters that had nothing to do with my plan and still less to do with demobilization, but I hoped that the Assistant of the Great Man might not delve too deeply into their mysteries.

My hope was justified. “A personal application?” he asked as he glanced at the reference number.

“Undoubtedly, Sir,” I replied, and something in the soldierly timbre of my voice arrested his attention.

Carefully replacing his teacup in its saucer he raised his eyes towards me. As he did so he started as though he had received a shock; a look of perturbation came over his features; his cheeks assumed an ashy tint and for a moment my fate trembled in the balance. But gradually I could see his years of training were reasserting themselves; the moral support of the O.B.E. on his breast was restoring his courage; he muttered to himself, and I caught the words “Superior Authority.”

Still muttering he rose and retired into the next room. Everything was proceeding according to plan.

In less than a minute he reappeared and beckoned me to follow him. I then knew that I should soon be in the presence of the Great Man himself.

I stood in front of an oak desk and noticed the keen but suppressed energy of the wall-paper, the tense atmosphere of war vibrating through the room, the solid strength of England incarnate behind the oak desk.

The Great Man spoke. His opening words showed that his interest was centred rather in me personally than in the file that lay before him. He spoke again, rose from his seat and disappeared. And as he went I caught the words, “Superior Authority.” In less than a minute he returned and beckoned me to follow him. I then knew that I should soon be in the presence of the Very Great Man himself. Everything was proceeding according to plan.

I stood in front of a mahogany desk and noticed the keener but more suppressed energy of the wall-paper, the tenser atmosphere of war vibrating through the room, the solid strength of the Empire incarnate behind the mahogany desk.

The Very Great Man spoke. His opening remarks showed that his interest was centred in me personally. He spoke again, and these are his exact words: “Mr. Jones,” he said, “I perceive that you are a student of King’s Regulations, and that you conform your actions to those estimable rules. You will be demobilised forthwith, and in view of your gallant service I have pleasure in awarding you a bonus of two hundred pounds in addition to your gratuity; but please understand that this exceptional remuneration is given on the condition that you are out of uniform within two hours.”

With my feet turned out at an angle of about forty-five degrees, my knees straight, my body erect and carried evenly over the thighs, I saluted, about turned and marched to the door. Everything had proceeded according to plan.

As I reached the door the Very Great Man spoke to the Great Man. “You will draft an Army Order at once,” he said, “in these words: King’s Regulations. Amendment. Para. 1696 will be amended, and the following words deleted:—‘Whiskers, if worn, will be of moderate length.’”

I am still in the Army. The truth of the matter is that what I have described did not really happen. My nerve failed me at the door of Mr. Nathan’s. But I believe that whiskers, detachable, red, can be obtained from Mr. Nathan for a few shillings.

Motto for the Anti-British Écho de Paris: “Ludum insolentem ludere Pertinax.”

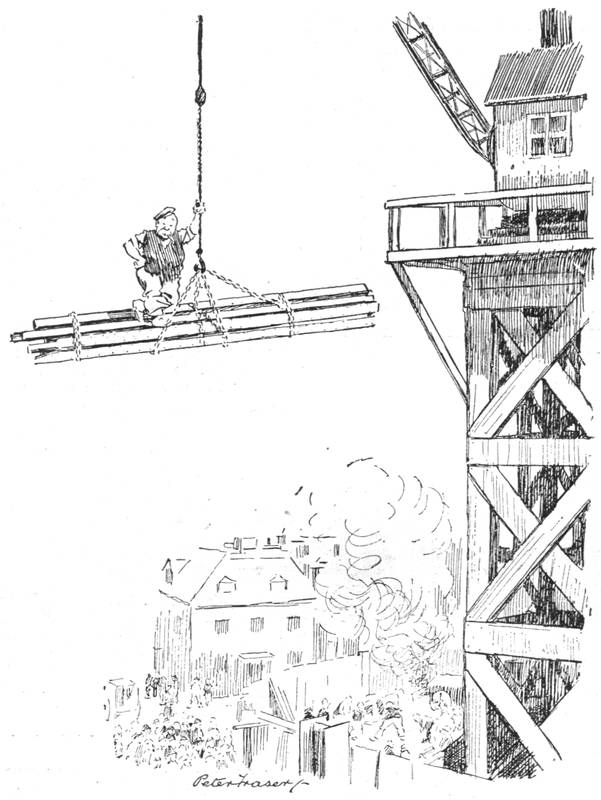

First Bricklayer (pausing so as not to exceed his Union’s speed limit). “BOUGHT ANY OF THESE ’OUSING BONDS, MATE?”

Second Bricklayer (ditto). “NOT ME; THEY’LL NEVER GET NO ’OUSES BUILT, NOT IF THINGS GO ON THE WAY THEY’RE GOING.”

Dashing round to Downing Street on our motor-scooter we were just in time to catch Sir Philip Kerr by one of his coat-tails as he was disappearing into the door of No. 10 and to ask him whether the strange rumour as to the Prime Minister’s latest project was true.

“Perfectly,” replied the genial Secretary, gently disengaging us. “Mr. Lloyd George has been greatly struck by Mr. Jack Jones’s comparison of Lord Robert Cecil to Oliver Cromwell, and has been studying the whole Irish Question anew from an historical standpoint. He has decided that the mandate for Ireland ought never to have been undertaken for the Papal See by Henry II. Strongbow——”

“Let’s see, wasn’t he a Marathon runner?” we asked.

“You are thinking of Longboat,” he replied. “The Earl of Pembroke was invited to enter Ireland by Desmond MacMorogh, and between you and me and the lamp-post Desmond was a bad hat. Look at the way he stole Devorghal, the wife of Tigheiranach O’Rourke.”

“Quite, quite,” we replied. As a matter of fact, if he had mentioned “The Silent Wife” we should have felt a bit more at home with the situation.

“Now take the Danes,” said Sir Philip. “Do you ever hear an Irishman complain of the injustice done to Ireland by the Danes? After that little scrap at Clontarf they accepted the Danish invasion quite naturally. Anyhow, the Danes got there first, and the Prime Minister’s view is ‘first come first served.’”

“But will Denmark undertake the mandate?” we asked doubtfully.

“Why not? They have Iceland already, and there is only one letter different.”

Scooting thoughtfully away, we went to visit Mr. T. P. O’Connor, feeling sure he would have some light to throw on the situation. We found him overjoyed with the proposal.

“Ireland and Denmark are simply made for each other,” he pointed out; “both are butter-producing countries and, welded together, they will form one homogeneous and indissoluble pat. Peace will reign in Ireland from marge to marge.”

Mr. Devlin was less optimistic. The rule of Dublin Castle under Olaf Trygvesson was, he declared, not a whit better than the rule of Dublin Castle to-day. It was true that Turges the Dane was King of All Ireland in 815, but it was not until that chieftain had been very rightly and carefully killed by Melachlin that the Golden Age of Ireland began. He was doubtful whether Mr. Edmund de Valera would consent to be a toparch under Danish suzerainty. As for himself, he held by the Home Rule Bill of 1914 or, failing that, Brian Boru.

When we asked Sir Edward Carson how he viewed the prospect of becoming a Scandinavian jarl, he adopted a morose expression reminding us not a little of the “moody Dane.”

“If the Prime Minister’s proposal becomes law,” he said firmly, “I shall have no alternative but to hand over Ulster to Holland.”

We scooted slowly back to the office, forced to the conclusion that the Irish Question is not settled even yet.

Shall I ever see again

In the human head a brain

Like the article that fills

That interior of Bill’s?

Never a day can pass but he

Makes some great discovery;

His inventions are so many

That you cannot think of any

Realm of science, wit or skill

That is not enriched by Bill.

To relieve the awful strain

Of possessing such a brain

William always used to play

Eighteen holes each Saturday.

But he scarce could see at all,

And he often lost his ball,

Plus his temper and his pelf,

So he made a ball himself,

Which, if it should chance to roam

Out of sight, played “Home, Sweet Home”

On a small euphonium he

Had inserted in its tummy.

Next he wrought with cunning hand

Round its waist an endless band,

An ingenious affair

Such as tanks delight to wear;

And, inside, a little motor

Started every time you smote or

Even when you topped your shot;

And, once started, it would not

Stop, for if it came within

Half a furlong of the pin,

Then it was designed to roll

Straight and true towards the hole.

This is scarcely strange, because

It was bound by Nature’s laws,

And a magnet was the force

(Hidden ’neath its skin, of course)

Which, thought he, would make it feel

Drawn towards a pin of steel.

When he practised first with it

William almost had a fit,

For the ball with sudden whim

Started madly chasing him!

“That’s a game that I’ll soon settle,”

William said; “my clubs are metal;

Spoons and other clubs of wood

Will be every bit as good.”

Then he found to his dismay

Every time he tried to play

That the ball with sundry hoots

Chased the hob-nails in his boots.

Finally he had to use

On his feet a pair of shoes

Of a most peculiar shape

Made of insulating tape.

So the final test arrives

When once more he tees and drives.

Joy! As soon as he has hit he

Sees it toddling down the pretty,

Never swerving left or right

Till it waddles out of sight,

Plodding through a bunker and

Braying like a German band.

Reader, possibly you’ll guess

That the ball was a success.

’Twas in fact a super-sphere,

But—I shed a scalding tear

On these verses as I write ’em—

He forgot just one small item

Which (as small things often will)

Simply put the lid on Bill:

For the hole proved far too small

To accommodate his ball.

Best Man. “’Ow much?”

Parson. “Well, the law allows me seven-and-sixpence.”

Best Man. “Then ’ere’s ’arf-a-crahn. That makes it up to ’arf-a-quid.”

“Wanted Situation by respectable middle-aged Girl; working housekeeper, can cook, bake; would not object to milk one cow (Protestant).”—Ulster Paper.

As distinct from a Papal Bull.

“Having successfully towed the disabled American steamer Tashmoo 1,200 miles, the Fort Stephens, a Cunard steamer, arrived at Queenstown on Saturday.”—Daily Paper.

“Having successfully towed the disabled American steamer Tashmos, with which she fell in last Monday, 200 miles, the Fort Stephen, a Cunard steamer, arrived at Queenstown on Saturday.”—Same paper, same day.

“The King has notified his intention to command the attendance of Lieutenants of Counties and the Lord Mayors and the Lost Provosts of Great Britain, at Buckingham Palace on the 15th instant.”—Glasgow Paper.

Mr. Punch hopes that this additional publicity will lead to the recovery of the missing magistrates.

Literature is becoming so commercialised that it is to be expected that before long popular authors, who already surreptitiously practise the tradesman’s art, will go a step further and write their own advertisements. No longer will they be content to get themselves interviewed on the subject of their next book, their new car and their favourite poodle, or to depend on the oleaginous eulogies of the publishers.

For instance:

Mr. DOUGLAS DORMY

begs to announce that he is

NOW SHOWING

his new Novel,

THE HIDDEN HAND OF HATE,

and confidently recommends it to

his Customers.

It contains no fewer than 92,563 of the

BEST WORDS

in the English Language

and is guaranteed

free from Split Infinitives.

Or again:—

Are you one of the

mentally alert men, the wistful women,

who have filled up an application form

to-day for

PATTERNS OF CHAPTER ONE

of

SEPTIMUS POSHER’S

New great romance of love and mystery

THE SICKENING THUD?

If you have not already done so, lose no time, but write asking for sample of

OPENING CHAPTER

(where the pink-eyed woman prevents the marriage of Ethel and Ludovic);

of

CHAPTER NINETY,

with its nine superb-quality murders;

or

CHAPTER TWO HUNDRED

(the last), where Ethel and Ludovic at last set out through the

FAIRYLAND OF LIFE.

You incur no risk in asking for these exquisite samples.

Write direct to Septimus Posher.

Or yet again:—

Mr. BOREAS BINKS

has pleasure in announcing that his new volumes of

RECOLLECTIONS

is now showing at all Libraries. He can confidently claim that this work, entitled

PEOPLE I HAVE MET AND

WHAT IS WRONG WITH THEM,

is absolutely the most refined volume of Scandal on the market. All the reminiscences are novel and tasty.

Or once more:—

KEATS WILLIAMS,

Poet and Critic.

Poems of every description completed

at the shortest notice.

Ask to see our choice spring lines.

Specimens Free.

Epics within Two Days.

Odes within a few Hours.

Sonnets, Rondeaux, Triolets, Quatrains

while you wait.

A well-known Judge writes: “I should very much like to give you a trial. I am sure you deserve it.”

[“One hundred Diplomatists’ Writing Tables, Cupboards, etc., for immediate delivery.—Office Furniture Manufacturers, —— and Co., ——, Berlin.”—The Times “Business Opportunities” column.]

Lightly loose the silken cable,

Swell, ye sails, by zephyrs kissed,

Bearing me the walnut table

Thumped by Bethmann-Hollweg’s fist;

Steering, not by course erratic,

Safe to the appointed wharf,

Bring, O bark, the diplomatic

Kneehole desk of Ludendorff.

Softly now, ye dockers, pardie,

Cease your wrangling for a bit,

Dump the seat whereon Bernhardi

Bowed his dreadful form to sit;

Make no scratch however tiny

When the circling crane-arm sags

On the chair that rendered shiny

Hindenburg’s enormous bags.

Blotting-papered, india-rubbered,

Good as new, with pencils piled,

Bring me the immortal cupboard

Where the Hymn of Hate was filed;

Who can say how oft, when brisker

Beat the heart behind his ribs,

Tirpitz wiped upon a whisker

Pensively these part-worn nibs?

Here are Kultur’s very presses,

Calendars that marked The Day,

Max von Baden’s ink-recesses,

Dernberg’s correspondence-tray;

Gone the imperial years, and cooler

Counsels on the Spree are planned,

Still one may acquire the ruler

Toyed with by a War Lord’s hand.

Waft them then, ye winds, let Fritz’s

Office furniture be mine;

Each one of these priceless bits is

Salvage from a Junker shrine;

Breathing still the ancient essence,

They shall give me, when I speak,

Something of the German presence

And the blazing German cheek.

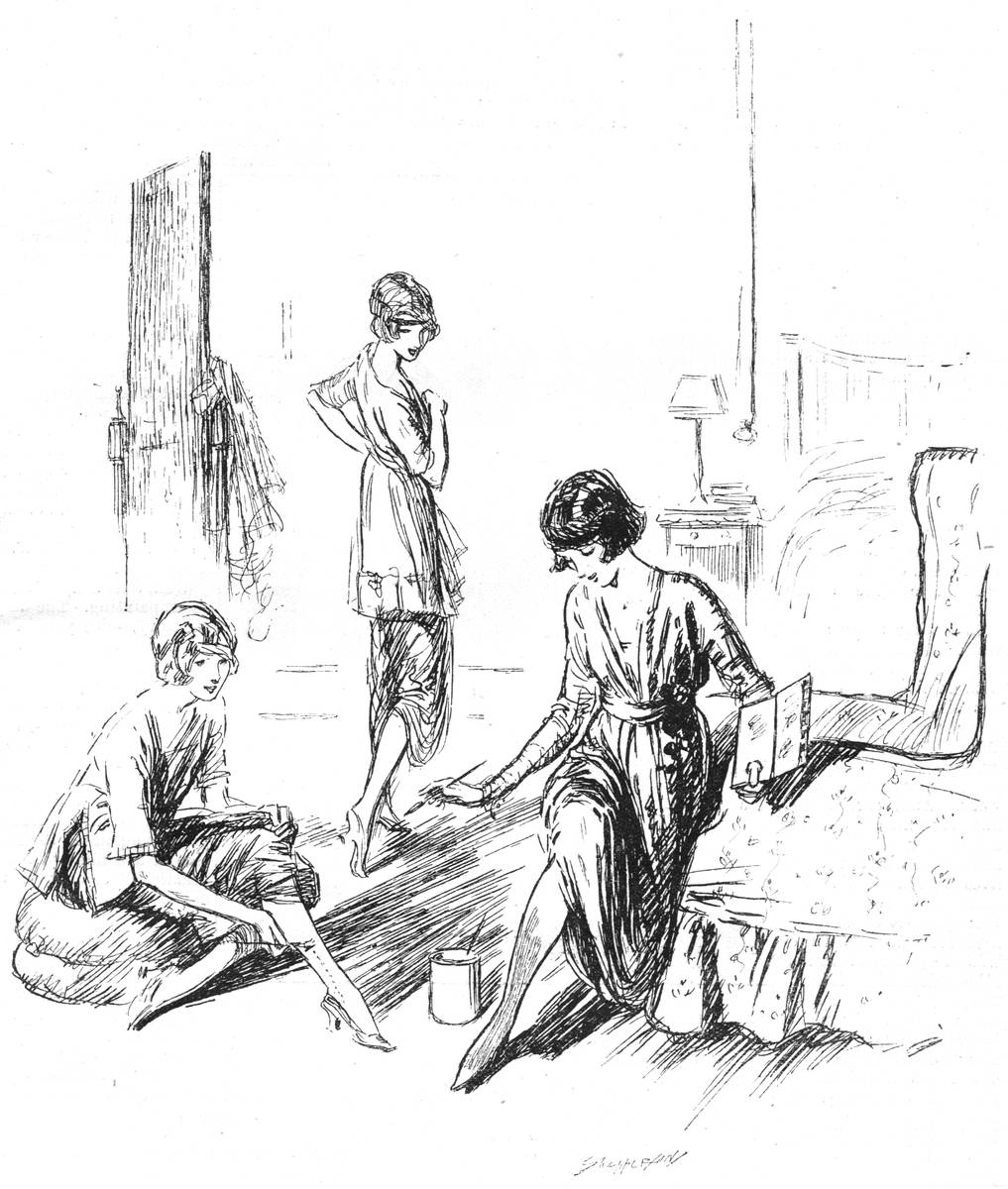

OWING TO THE SHORTAGE AND PROHIBITIVE PRICE OF SILK STOCKINGS, THE LADIES MAYFAIR DECIDE TO DO WITHOUT THEM AND HAVE RECOURSE TO PAINT.

Mistress (to maid who has just served boarders’ breakfast). “What were they talking about, Jane?”

Jane. “You, Mum.”

One point emerges very clearly from the murky chaos of the industrial situation to-day; and that is that the brain-worker will not for ever be content to be merely a brain-worker, thinking and thinking, hour after hour, day after day. He is beginning to realise his latent capacity for manual labour; and he demands as his right a larger opportunity for self-development, so that he too may escape from the drudgery of brain-work and rise at last to the higher, freer life of muscular exertion. There must already be many brain-workers who are well-fitted to take their place in the ranks of manual labour; and the cry goes up with increasing force that, given only that opportunity which is every man’s due, millions of their fellows are capable of lifting themselves to the same standard.

In my house the cry goes up with peculiar force about Easter-time, when I repaint as much of the house as I am allowed and whitewash the rest, and can appreciate what I am missing in my everyday calling. It is astonishing to think that one used actually to pay people money to paint and whitewash, and looked on with meek wonder, for six weeks, while they did it. Bourgeois I may be, but I have put aside that folly. The Easter holidays now are to me the best holidays of the year, because for four whole days I can do almost unlimited decorating. I begin with the conservatory; I do it a delicate pale blue, and it looks very lovely. The vine in the conservatory no longer yields her increase as she used to do, but I can’t help that. After the conservatory I start on the basement, and the opportunities in the basement are endless. It is a curious thing that brain-workers who do much decorating in their spare time do most of it in the basement and not in the rooms they have to occupy themselves. The basement is fair game. Another curious thing is that the people who do have to occupy the basement never seem to appreciate what you are doing for them. They appear to think you are merely amusing yourself.

The best day for doing the basement therefore is Easter Monday, when you can legitimately send the whole staff (if any) away for a holiday, and commandeer the entire kitchen equipment. This point is more important than you may suppose; since if the staff are at home and you want to use the basement bucket or the soft broom (both of which are essential for efficient whitewashing) it is almost certain that they will at the same time want to put them to some preposterous use of their own; and this causes either delay or friction, probably both. Besides, they keep bustling about behind you and saying, “’T’t, ’t’t,” or “Busy to-day!” in a surprised voice. This is most irritating, and an irritated painter always goes over the edges.

When you have got rid of the staff (if any) you can get to work on the scullery and whitewash the ceiling. Whitewashing is much superior to painting. Painting looks lovely while you are doing it, but is very horrible when it is dry, being streaky or blistery or covered with long hairs. Whitewash looks horrible while you are doing it, but marvellous when it is dry, which is much more satisfactory. In a life of average prosperity and no small public distinction, including an intimacy with a professional tenor and two or three free lunches with noblemen, I can recall few moments of such genuine rapture as the one when you creep down to the basement to find the whitewash dry at last and brilliant as the driven snow.

The other thing about whitewashing is that it is done with a broom, not with a finicking brush and a small pot, but a good fat bucket and the housemaid’s soft-broom. In this way you can really get some bravura into your work. And, except perhaps for watering the garden with a hose, there is no quicker way of making a really good mess. Whitewashing by this method, I find that it takes much longer to remove the whitewash from the floors and other places where it is not intended to go than it does to put the whitewash on the places where it is intended to go; but the charwoman does the removing on Easter Tuesday, and I still think that that method is the best. Especially, perhaps, for outside walls, because in one’s artistic frenzy it is usual to cover most of the rose-trees with whitewash; they look then like those whitewashed orchards, and visitors think you are a scientific gardener, combating Plant Pests.

Personally I don’t pay too much attention to the rather arbitrary rules on painting laid down by the Painters’ Union. Life is too short. For instance, I don’t put my brushes in turpentine when I have finished for the day; and if I do I put the green brush and the light-blue brush and the black brush and the white brush in the same pot, and terrible things happen. I don’t like my art to be hampered by petty notions of economy, and if brushes persist in crystallising into tooth-brushes when left to themselves for an hour or two I simply use a new brush.

Nor do I insist on “cleaning thoroughly the surface before the paint is applied.” Anyone who sets out in practice to clean thoroughly the surface of the basement before applying the paint will find that the Easter holidays have slipped away long before any paint is applied at all. Besides, one of the main objects of paint is to hide the dirt, so why waste time in removing it?

On the other hand, I am not content with mere painting; I go in thoroughly for all the refinements like driers and varnishes and gold-size. Driers and gold-size are extremely necessary when painting the basement, because if there is one thing the staff enjoy more than tea-cups coming away in the ’and, it is really rubbing themselves against wet paint and wandering round muttering complaints about it. Without a driers or some drier or whatever it is, the basement remains wet for ever, and all work ceases while the staff amble about, ecstatically rubbing themselves against the doorposts and saying “T’tt, t’tt,” in a meaning way.

It is a sad quality of oil-paint that when it is dry it no longer looks so lovely and shiny as it looks when it is wet. It was found that the sense of disappointment which this produced was greater than the Painters’ Union could bear; so someone, in order to prevent industrial strife, invented some stuff called varnish, by which, at the very moment of disillusion, the maximum of shininess can be again produced with the minimum of effort. It is one of the few inventions which make a man grateful for the advance of science.

Well, that is all there is about painting. The only difficulty, once you have begun, is to know when to stop. Painting is a kind of fever. The painting of a single chair makes the whole room look dirty; so the whole room has to be painted. Then, of course, the outside of the windows has to be brought up to the same standard; and if once you have painted the outside of a window you are practically committed to painting the whole house.

The only thing that stops me painting is a turpentine crisis, which usually occurs just before church on Sunday morning, when one has three workmanlike coats of glossy enamel or pale-green on one’s hands. Week-end painters should keep a close eye on the situation, and cease work while there is yet sufficient turpentine to cope with the workmanlike coats; for I find that in these days the churchwardens look askance at you if you put in a penny with a pale-green hand.

The extraordinary thing is that this painting fever doesn’t seem to afflict professional painters; they know exactly when to stop. But then they don’t appreciate the luxury of their lot. They don’t realise that theirs is one of the few forms of labour in which a man has some tangible result (well, not tangible, perhaps) to show for his work at the end of the day. There is nothing more satisfactory than that. It is true, no doubt, that the professional painter would rather have a windy article like this to show; all I can say is I would rather have a bright-blue basement or a middle-green conservatory.

Young Lady (making conversation). “How perfectly sweet! I’m sure I must have been there. I remember those glorious pines.”

Real Artist. “I call that ‘The Fertilising Influence of the Sun’s Rays on the Mind of a Poet lost in Thought.’”

Young Lady. “How perfectly sweet! No wonder he lost it, poor darling.“

In a Press sighing deeply over the various Labour crises there is the glad news that Mr. Clem Edwards, M.P. (barrister), of the National Democratic Party, has made a match with Mr. James Walton, M.P. (miner), of the Labour Party, to “hew, fill and train two tons of coal in the shortest time for fifty pounds a side.” The contest is to take place at Whitsuntide.

We hope that more Members of Parliament will follow suit, and challenge each other to feats of wholesome toil, to the great benefit of the nation.

In time no doubt the idea would take on with the masses and an immense amount of useful work would be performed disguised as sport. August Bank Holiday might become the great yearly fixture for a sort of Gentlemen v. Players bricklaying competition, and we may one day read of huge crowds being attracted to the East India Docks on Easter Monday to watch stockbrokers, flushed with their victory of Boxing Day, playing a return match with the dockers at unloading margarine. The movement might expand until even on Labour Day work would be in progress.

All this is, however, remote, but the solid fact remains that during Whitsuntide of this very year work will actually be done in a coal-mine. So far the miners themselves have expressed no official views on the contest, but there is a general feeling of amazement among them that anyone should work so hard on the chance of winning a mere fifty pounds. For the public at large there is the gratifying thought that Messrs. Edwards and Walton are very nearly matched, and they should therefore produce between them in their friendly struggle the best part of four tons of coal, an unexpected windfall for the nation.

“POST OFFICE TREASURY BONDS.

It should be noted that, as regards the Post Office issue, dividends on registered bonds will not be deducted at the source.”—Daily Paper.

Nor, we understand, has the Chancellor of the Exchequer any present intention of confiscating the capital.

“America’s first Floating Bar-room. The City of Miami.—300,000 dols. has been spent in fitting up this vessel for thirsty American citizens. She will ply between Miami, Fla. and Havana, Cuba. A special bilge keel is being fitted to steady ship and passengers.”—Shipping Journal.

A very necessary precaution.

Fond and resourceful Mother. “It’s baby’s birthday to-morrow. He’s too young to invite children, so I’m having fifteen people in to play bridge.”

The exodus was ended; stilled the urging

To “wait and let the passengers off first;”

I and my fellow-sufferers were surging

Along the gangway in one short sharp burst,

Clutching the straps so thoughtfully provided

Stamping on any feet that lay about,

And, Lady, it was then that you decided

This was where you got out.

I noted with an awestruck admiration

The gallant way in which you faced the press,

What force, what vigour, what determination,

What almost everything but politesse;

And then I gave back several hasty inches

Before your mænad rush; I felt alarmed

Lest you should use a hatpin in the clinches

While I was all unarmed.

So in a more or less intact condition

You made your exit through the trellised gate,

And (this, I must admit, is mere suspicion)

Asked of a porter was your hat on straight;

And lo! the bard, left dreaming suo more,

Mused upon things the future hid from view;

He looked adown the years and saw the glory

England would win through you.

For in my morning sheet I’d seen it bruited,

Mid talk of Jazz and Fox Trot, plaids and checks,

That boxing was a sport precisely suited

To what it quaintly called the gentler sex;

I thought about the coming day when bevies

Of beauty would be found inside the ropes,

And saw you, eminent among the “heavies,”

The whitest of white hopes.

I saw—and at the vision England’s stock ran

High above par—how in the padded strife,

Beneath the auspices of Mr. Cochran,

You’d whip the world, or should I say his wife?

Our land once more would boast the champion thumper,

The doughtiest dealer of the hefty welt,

The holder of—but no, by then a jumper

Will have replaced the belt.

“OFFICERS’ HEAVY-WEIGHTS.

Final: Lt. W. R. Nicol (R.F.A.) knocked out Lt.-General Lord Rawlinson, Commanding at Aldershot.”—Sportsman.

That’s more than Ludendorff could do.

“Some years have passed since I last saw Mr. ——, and last evening I found him considerably aged. His one black hair is very grey.”

Provincial Paper.

Probably the result of depression caused by loneliness.

“The Prince of —— has returned recently from England where he was educated. He is to marry several wives, as is the custom of ——. His education is to continue.”—North China Daily News.

We can well believe it.

“The Chester Vase resolved itself into a contest between a four-year-old and some three-year-olds, but in this case the four-year-old was Buchan, a Trojan among minnows.”—Provincial Paper.

The writer seems to be a student of “classic” form.

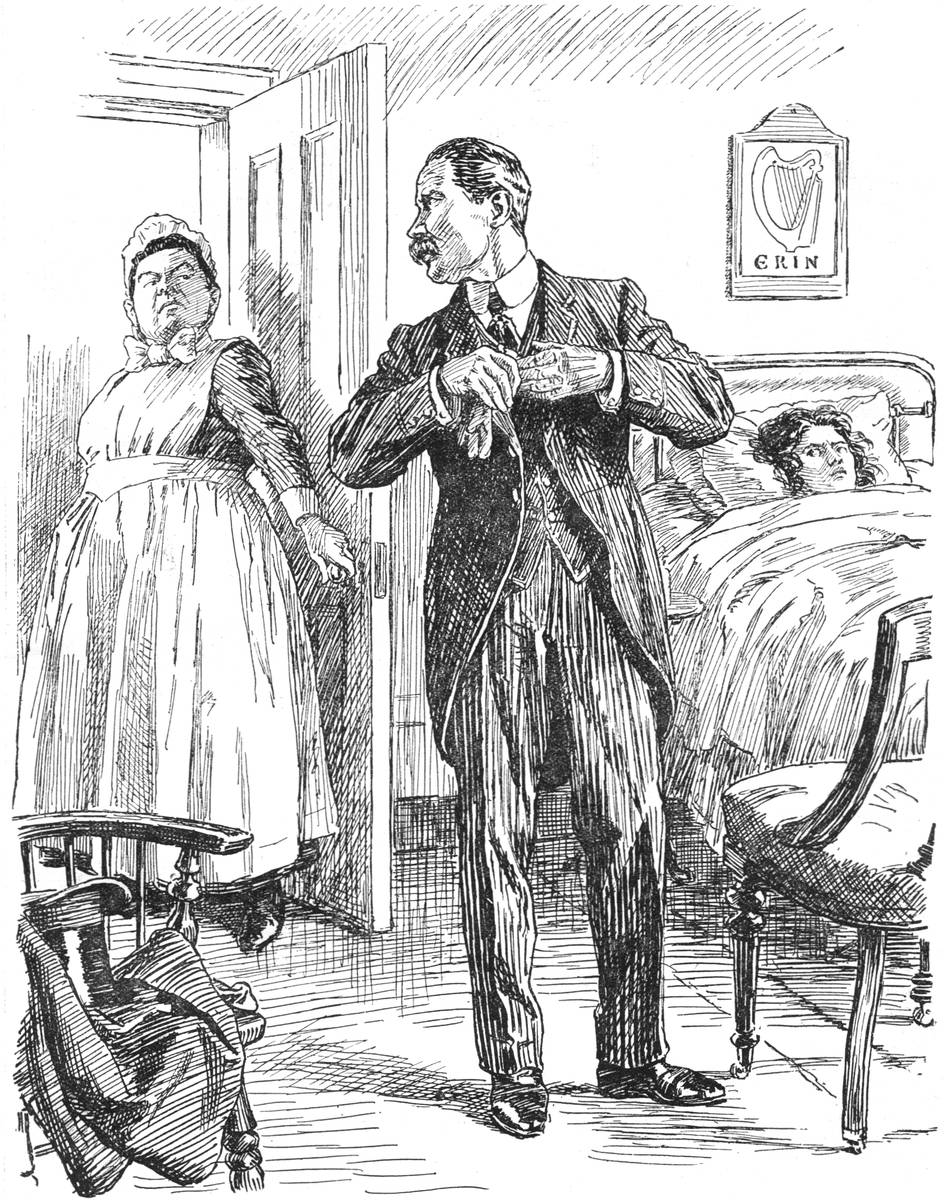

Dr. Bonar (to Nurse Devlin). “MUST YOU GO, NURSE? (Resignedly) WELL, WE SHALL HAVE TO DO OUR BEST WITHOUT YOU.”

[Nationalist Members have decided to take no further part in the discussion of the Government of Ireland Bill.]

Monday, May 3rd.—The Prime Minister being confined to his bed and Mr. Bonar Law being engaged elsewhere in inaugurating the Housing campaign the House of Commons was in charge of the Home Secretary. Consequently Questions went through with unusual speed, for Mr. Shortt has a discouraging way with him. The most searching “Supplementary” rarely receives any recognition save a stony glare through his inseparable eye-glass, as who should say, “How can So-and-so be such an ass as to expect an answer to his silly question?”

People who consider that the Minister of Transport is too much of “a railway man” will, I fear, be confirmed in their belief. In his opinion the practice of the Companies in refusing a refund to the season ticket-holder who has left his ticket behind and has been compelled to pay his fare is “entirely justifiable.” He objected, however, to Sir C. Kinloch-Cooke’s interpretation of this answer as meaning that it was the policy of H.M. Government “to rob honest people,” so there may be hope for him yet.

It is wrong to suppose that the class generally known as “Young Egypt” is solely responsible for the anti-British agitation in the Protectorate. Among a long list of deportees mentioned by Lieut.-Colonel Malone, and subsequently referred to by Mr. Harmsworth as “the principal organisers and leaders of the disturbances” in that country, appeared the name of “Mahmoud Pasha Suliman, aged ninety-eight years.”

The process of cleaning-up after the War involves an Indemnity Bill. Sir Ernest Pollock admitted that there was “some complexity” in the measure, and did not entirely succeed in unravelling it in the course of a speech lasting an hour and a half. His chief argument was that, unless it passed, the country might be let in for an additional expenditure of seven or eight hundred millions in settling the claims of persons whose goods had been commandeered. An item of two million pounds for tinned salmon will give some notion of the interests involved and incidentally of the taste of the British Army.

Lawyers and laymen vied with one another in condemning the Bill. Mr. Rae, as one who had suffered much from requisitioners, complained that their motto appeared to be L’état c’est moi. Sir Gordon Hewart, in mitigation of the charge that there never had been such an Indemnity Bill, pointed out that there never had been such a War. The Second Reading was ultimately carried upon the Government’s undertaking to refer the Bill to a Select Committee, from which, if faithfully reflecting the opinion of the House, it is conjectured that the measure will return in such a shape that its own draftsman won’t know it.

Tuesday, May 4th.—The Matrimonial Causes Bill continues to drag its slow length along in the House of Lords. Its ecclesiastical opponents are gradually being driven from trench to trench, but are still full of fight. The Archbishop of Canterbury very nearly carried a new clause providing that it should not be lawful to celebrate in any church or chapel of the Church of England the marriage of a person, whether innocent or guilty, whose previous union had been dissolved under the provisions of the Bill. His most reverend brother of York spoke darkly of Disestablishment if the clause were lost, and eleven Bishops voted in its favour, but the Non-Contents defeated it by 51 to 50.

Captain Wedgwood Benn wanted to know whether swords still formed part of the uniform of Royal Air Force officers, and, if so, why. He himself, I gather, never found any use for one in the “Side Shows” which he has described so picturesquely. Mr. Churchill’s defence of its retention was more ingenious than convincing. Swords, he said, had always been regarded as the insignia of rank, and even Ministers wore them on occasions. But the fact that elderly statesmen occasionally add to the gaiety of the populace at public celebrations by tripping over their “toasting-forks” hardly seems a sufficient reason for burdening young officers with a totally needless expense.

The Postmaster-General is all for a quiet life. When the Dublin postal workers announced their intention of stopping work for two days in sympathy with a Sinn Fein strike, did he dismiss them? Not he. You can’t, as he said, dismiss a whole service. No, he simply gave them two days’ leave on full pay, a much simpler plan.

Thanks to the Irish Nationalists, who have announced their intention of taking no part in the discussion of the Government of Ireland Bill, Mr. Bonar Law was able to drop the scheme for closuring it by compartments. The new Irish doctrine of self-extermination has given much satisfaction in Ministerial circles. Mr. Churchill’s gratitude, I understand, will take the form of a portrait of Mr. Devlin as Sydney Carton under the shadow of the guillotine.

On the Vote for the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Colonel Burn suggested that a new Department should be set up to deal with the harvest of the sea. Dr. Murray approved the idea, and thought that the Minister without Portfolio might give up loafing and take to fishing.

Wednesday, May 5th.—Apparently it is not always selfishness that makes Trade Unionists unwilling to admit ex-service men to their ranks, but sometimes solicitude for the welfare of these brave fellows. Take the manufacture of cricket-balls, for example. You might not think it a very arduous occupation, but Dr. Macnamara assured the House that it required “a high standard of physical fitness,” and that leather-stitching was as laborious as leather-hunting. It is true that some of the disabled men with characteristic intrepidity are willing to face the risk, but the Union concerned will not hear of it, and the Minister of Labour appears to agree with them.

Even on the Treasury Bench, however, doctors disagree. Dr. Addison seems distinctly less inclined than Dr. Macnamara to accept the claims of the Trade Unionists at their own valuation. The bricklayers have agreed to admit a few disabled men to their union—bricklaying apparently being a less strenuous occupation than leather-stitching—but exclude other ex-service men unless they have served their apprenticeship as well as their country. Upon this the Minister of Health bluntly observed that the idea that it takes years to train a man to lay a few bricks was in his opinion all nonsense.

Thursday, May 6th.—Possibly it was because to-day was originally assigned for the opening of the Committee stage of the Home Rule Bill that Members in both Houses drew special attention to the present state of lawlessness in Ireland. If their idea was to create a hostile “atmosphere” it did not succeed, for, owing to Mr. Long’s indisposition, the Bill was postponed. Besides, the fact that every day brings news of policemen murdered, barracks burned, tax-collectors assaulted and mail-bags stolen, while to one class of mind it may argue that the present is a most inopportune moment for a great constitutional change, may to another suggest that only such a change will give any hope of improvement.

It is, at any rate, something to know that Irishmen have not in trying circumstances entirely lost their saving grace of humour. Thus the writer of a letter to Lord Askwith, describing with much detail a raid for arms, in the course of which his house had been smashed up and he himself threatened with instant death, wound up by saying, “I thought I would jot down these particulars to amuse you.”

The Commons had a rather depressing speech from Mr. McCurdy. His policy had been gradually to remove all food-controls and leave prices to find their own proper (and, it was hoped, lower) level. But in most cases the result had been disastrous, and the Government had decided that control must continue. Sir F. Banbury complained of the conflict of jurisdiction between the Departments. It certainly does seem unfair that the Food-Controller should be blamed because the Board of Trade is “making mutton high.”

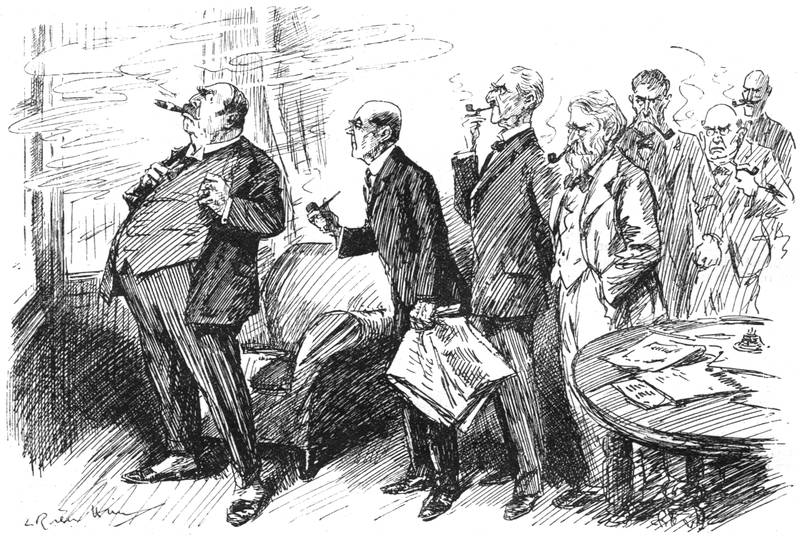

Spokesman of Club Deputation. “We trust, Sir, that you are not deliberately wearing that band on your cigar, as it is the desire of your fellow-members that you should oblige them by removing it.”

Mr. John Murray, the famous publisher, has recently given a representative of The Pall Mall Gazette some interesting facts and figures bearing on the impending crisis in the publishing trade. It is a gloomy recital. Men doing less work per hour with the present forty-eight hour week than with the old fifty-one hour week, and agitating for a further reduction of hours; paper rising in price by leaps and bounds. “Between the two they are forcing up the price of books to a point when we can only produce at a loss.” In other words, we are threatened with not merely a shortage but an absolute deprivation of all new books. The horror of the situation is almost unthinkable, but it must be faced. We can dispense with many luxuries—encyclopædias and histories and scientific treatises and so forth—but among the necessities of modern life the novel stands only third to the cinema and the jazz. It is possible that in time the first-named may reconcile us to booklessness, but that time is not yet.

What amazes us in Mr. John Murray’s pessimistic forecast is his failure to recognise and advocate the only and obvious remedy. By the reduction of the Bread Subsidy fifty millions have been made available for the relief of national needs. We do not say that this would be enough, but if carefully laid out in grants to deserving novelists, so as to enable them to co-operate with publishers on lines that would allow a reasonable margin of profit, it might go some way towards averting the appalling calamity which Mr. John Murray anticipates.

The Ministry of Information is closed, but should be at once reorganised as the Ministry of Fiction, with a staff of no fewer than five hundred clerks, and installed in suitable premises, the British Museum for choice, thus emancipating the younger generation from the dead hand of archæology. Similarly the utmost care should be taken to exclude from the direction of the Ministry any representatives of Victorianism, Hanoverism, or the fetish-worship of reticence or restraint. But no time should be lost. The duty of the State is clear. It only needs some public-spirited and respected Member of Parliament, such as Lieutenant-Commander Kenworthy or Colonel Josiah Wedgwood, to promote the legislative measures necessary to secure a supply of really nutritious mental pabulum for the million.

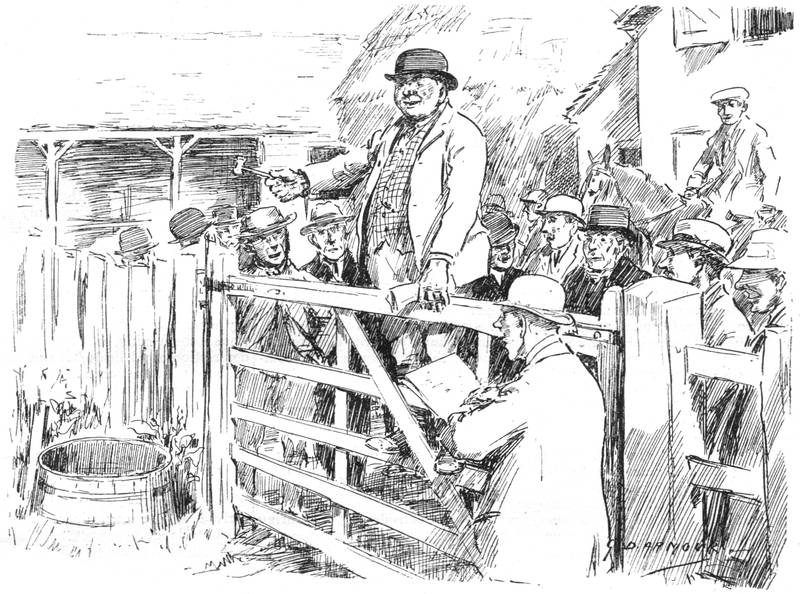

Auctioneer (selling summer “grass-keep”). “Now then, how much for this field? Look at that grass, gentlemen. That’s the kind of stuff Nebuchadnezzar would have given ten pounds an acre for.”

“Salary, £50 per annum, rising upon satisfactory service by annual increments of £5 to a maximum of £880.”—Welsh Paper.

“Conscience Money.—The Chancellor of the Exchequer acknowledges the receipt of 10/- from Liverpool.

The charge for announcements in the Personal Column is 7/6 for two lines (minimum), and 3/6 for each additional line.”—Times.

Any large outbreak of conscientiousness on this scale will mean ruin for the country.

“A band of armed ruffians disguised as soldiers held up a train near Parghelia, in Calabria, and carried off the contents of two vons, consisting chiefly of sausages.”—Scotch Paper.

This is an abbreviated way of speaking. By “the contents of two vons” the writer evidently means the contents of the baggage of two German noblemen.

It all happened so naturally, so inevitably, yet so tragically—like a Greek play, as Willoughby said afterwards.

Willoughby is my younger brother, and in his lighter moments is a Don at Oxford or Cambridge; it will be safer not to specify which. In his younger and more serious days he used to play the banjo quite passably, and, when the Hicksons asked us to dine, they insisted that he should bring his instrument and help to make music to which the young people might dance, for it seems that this instrument is peculiarly suited to the kind of dancing now in vogue. Willoughby had not played upon the banjo for fifteen years, but he unearthed it from the attic, restrung it, and in the event did better than might have been expected.

Anyhow, he did not succeed in spoiling the evening, which I consider went well, despite the severe trial, to one of my proportions, of having to perform, soon after dinner, a number of scenes “to rhyme with hat.” Indeed, when I was finally pushed alone on to the stage, any chagrin I might have felt at the ease with which the audience guessed at once that I represented “fat” was swallowed up in the relief at being allowed to rest awhile, for “fat” proved to be correct.

It is not of dumb-crambo, however, nor of hunt-the-slipper (a dreadful game), nor of “bump” (a worse game) that I wish to speak, but of that which befell after.

It was a very wet night, and when the hour for our departure arrived there arose some uncertainty as to whether we could find a taxi willing to take us home.

“I will interview the porter,” said Willoughby (the Hicksons live in a flat), and he disappeared, to return in a few minutes with something of the air of a conspirator.

“Get your coat on,” he said curtly.

“Have you a taxi?”

“No, I have a car. Get your coat on, and be quick about it.”

“A car?” I said. “What car? Whose car?”

Willoughby turned upon me. “If you prefer to walk, you can,” he said; “if not, get your coat on, as I say, and don’t ask stupid questions.”

I did not prefer to walk—would that I had!—but proceeded to bid my host and hostess Good-night. Even as I was doing so the porter came to the door.

“Hurry up, Sir,” he called to Willoughby in a stage whisper. “He can’t wait; he’s late already.”

As we followed him into the hall the porter went on whispering to Willoughby.

“Friend of mine. Always do me a turn. Going right to your square.” He continued to nod his head confidentially.

Willoughby turned to me.

“Got half-a-crown?” he grunted.

I had. The porter’s head-noddings redoubled.

Arrived at the door, we found a resplendent car, a chauffeur of the imperturbable order seated at the wheel.

“I’m very much obliged——,” Willoughby began.

“That’s all right, Sir,” said the man. “I’m going that way.”

We stepped in, drew the fur rug over our legs, and the car glided off.

“It’s a nice car,” said Willoughby.

“I understand that the chauffeur is a friend of the hall porter?” I commented.

“That is so.”

“And the owner of the car is——?”

“Some person unknown.”

“Where ignorance is bliss——”

“I am a little doubtful if the chauffeur will mention our ride to his master, if that is what you mean,” said Willoughby.

“Have you considered the bearing of the law concerning Conspiracy on this case?” I asked.

“I have not, nor do I intend to,” said Willoughby airily. “The law concerning Bribery and Corruption has a much more direct bearing. Got two more half-crowns?”

I was searching for them as we turned into the square in which we live and the car slowed down.

“Tell him it’s at the far corner,” I said.

And then suddenly a rasping voice sounded on the night air:—

“Here, Rodgers! Where are you off to? You’re very late, you know—very late.”

The car had stopped with a jerk before a house which was certainly not our house. A stream of light from the open door flooded the pavement. On the steps stood Percival, the man I had that row with about the Square garden. On the pavement, his hand outstretched to open the car door, was he of the rasping voice.

“This is the owner,” said Willoughby, and he laughed quietly to himself. He always giggles in a crisis. I could have kicked him. But at the moment I was hurriedly debating whether I could possibly escape by the door on the far side without being seen. “A small thin man might have done it,” I thought. But, alas! I am neither small nor thin.

Then the door of the car opened and Willoughby stepped forth into the limelight, as it were. During the evening the dumb-crambo and such had rather dishevelled his hair, and a wisp of it now appeared from beneath the brim of an elderly Homburg hat pushed on to the back of his head. Under his arm was the banjo. On his face was that maddeningly good-natured smile of his.

“What are you doing in my car?” demanded the rasping voice.

Willoughby did not answer for a moment, but simply stood there smiling.

Then he said, “Entirely my fault. Your chauffeur is in no way to blame. The fact is we couldn’t get a taxi, and my brother being rather delicate——”

“What, another?” barked the rasper.

There was nothing for it. Acutely conscious as I was how emphatically my countenance, flushed by the exertions of the evening, belied Willoughby’s description of “delicate,” it was impossible for me to remain in the car, and I stepped heavily out.

“It rhymes with hat,” said Willoughby softly.

As we slunk off down the Square, after as painful a five minutes as I care to remember, Willoughby kept repeating, “Very unlucky—very unlucky,” till we arrived at our own door. Then he began to laugh.

“And what is the joke?” I asked.

“There is no joke,” he said—“no joke at all.”

“Indeed there is not,” I said bitterly. “You must remember that, unlike yourself, I live here permanently.”

“I realise it,” said Willoughby. “But do you not think, on consideration, that that really gives you the advantage? I mean, you have thus the opportunity of living down the unfortunate accusation of inebriety that has been brought against us, which I shall not be in a position to do.”

I hate living things down.

From a restaurant bill-of-fare:—

“Develled Leg of Foul and Curly Bacon, 2/6.”

“WORMWOOD SCRUBS’S ILL-HEALTH.

Released to Private Hospital.

Mr. Kelly, the Lord Mayor of Dublin, has released Wormwood Scrubs owing to his health.”—Australian Paper.

Some trouble in the cellular system, we gather.

Mr. James Sexton, M.P., who was howled down at a meeting at St. Helens recently, said he refused to bow the knee to a lot of body-snatchers who wanted him to sacrifice his manhood and conscience to satisfy their inclinations. A self-respecting sexton could do no less.

(After Ann and Jane Taylor.)

High on a mountain’s haughty steep

Lord Hubert’s palace stood;

Before it rolled a river deep,

Behind it waved a wood.

Low in an unfrequented vale

A peasant had his cell;

Sweet flowers perfumed the cooling gale

And graced his garden well.

But proud Lord Hubert’s house and lands,

Of which he’d fain be rid,

Long linger on the agents’ hands—

He cannot get a bid.

On sauces rich and viands fine

Lord Hubert’s father fed;

Lord Hubert, when he wants to dine,

Eats margarine and bread.

How diff’rent honest William’s lot!

He’s cheerful and content;

He always lets his humble cot

At thrice its yearly rent.

His dapple-cow and garden-grounds

Produce him ample spoil;

His lodgers pay him pounds and pounds,

He has no need to toil.

Lord Hubert sits in thrall and gloom

And super-taxes grim

Pursue him to his marble tomb,

And no one grieves for him.

But, when within his narrow bed

Old William comes to lie,

They’ll find (I mean when William’s dead)

A tidy bit put by.

Navvy on girders (soliloquising). “’Eaven ’elp them poor perishers underneaf if this ’ere chain breaks!”

(From an Oxford Correspondent.)

The list of the recipients of honorary degrees to be conferred by the University of Cambridge has already been announced. We are glad to be able to supplement it by information, derived from a trustworthy source, of the corresponding intentions of the University of Oxford.

The Oxford list is not yet complete, but the following names and the reasons for which the distinction is to be conferred may be regarded as certain and authentic:—

The Right Hon. Winston Churchill, M.P., for his strenuous efforts to brighten Sunday journalism.

Mr. Augustus John, for unvarnished portraiture and the stoical fortitude exhibited by him in face of the persecution of the Royal Academy.

Mr. Lovat Fraser, for his divine discontent with everything and everybody and his masterly use of italic type.

Lady Cooper, the wife of the Lord Mayor, for conspicuous gallantry in advocating the taxing of cosmetics.

Sir Philip Gibbs, for his generous recognition of the services of British generals during the War, and for promoting cordial relations between all ranks in the Army.

Mr. Wickham Steed, for his invaluable and untiring exertions in familiarising the public with Jugo-Slav geography.

All the above will receive the D.C.L. It is also proposed to confer the degree of Honorary Master of Arts on the entire body of Oxford road-sweepers, for their disinterested patriotism in accepting a wage on a par with that received by many tutors and demonstrators of the University.

Since I first saw her this year she has been a Sleeping Beauty (very wide awake) and a Chrysanthemum and many other lovely things. In Autumn Leaves, where her bloom is blown away by the fierce ardour of the Wind, and she is left to die forsaken, she recalled a little the moving sadness of her Dying Swan. It was a “choreographic poem” of her own making—to music of Chopin—and I think I have never seen anything more fascinating than the colour and movement of the Autumn Leaves and the “splendour and speed” of the Autumn Wind. This was danced by Mr. Stowitts, and it couldn’t have been in better hands or feet. M. Volinine is largely content to be a source of support and uplift to his partner, but in The Walpurgis Night he gave us an astounding exhibition of poise and resilience. In The Magic Flute (not Mozart’s but Drigo’s), Mlle. Butsova had a great triumph. She has all the arts and graces of her craft that can be taught, and to these she adds one of the few gifts that no training can confer—the natural joy of life that comes of just being young.

“Food prices were coming down. Soap had already been reduced 1d. a lb.”—Daily Paper.

We tried it in 1917, but found it deficient in protein.

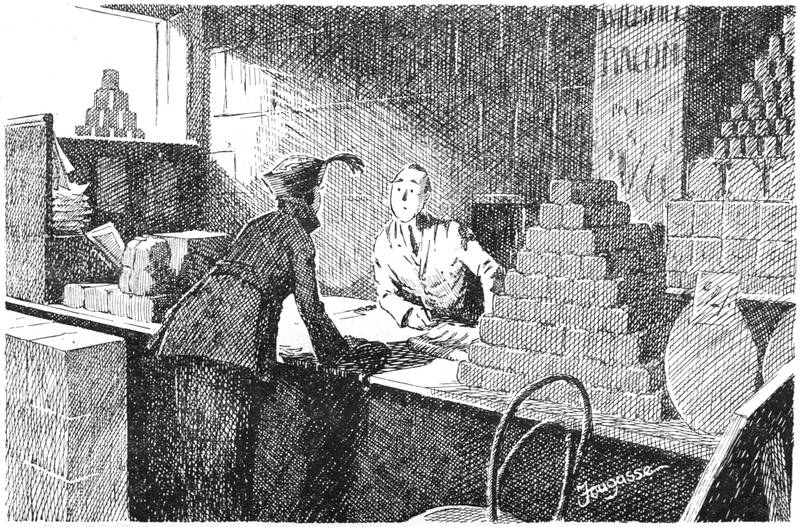

“You’re sure this is Wiltshire bacon?”

“Er—I wouldn’t like to guarantee it, Madam—not absolutely.”

“Where do you get it from, then?”

“Well, it comes from America, Madam.”

(By Mr. Punch’s Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Probably one of your first, and abiding, impressions of The Third Window (Secker) will be that of almost extreme modernity. Certainly Anne Douglas Sedgwick (Mrs. Basil de Selincourt) has produced a story that, both in its protagonists—a young war-widow and a maimed ex-officer—and in its theme—spirit-communication and survival of personality—is very much of the moment. It is a short book, not two hundred pages all told, and with only three characters. You observe that I have given you no particulars as to the third, though (or because) she is of the first importance to the development. To say more of this would be to ruin all, since suspense is essential to its proper savouring; though I may indicate that it turns upon the question whether the dead husband is still so far present as to forbid the union of his widow and his friend. The thing is exceedingly well done, despite a suggestion now and again that the situation is becoming something too fine-drawn; I found myself also in violent disagreement with the ending, though for what reasons I must deny myself the pleasure of explaining. Perhaps the cleverest feature of an unusual tale is the idea of Wyndwards, the modern “artistic” house that is its setting—a house rather over deliberate and self-conscious in its simplicity and beauty, lacking soul, but swept and garnished for the reception of the seven devils of bogiedom. The atmosphere of this is both new and conveyed with a very subtle skill.

It must be admitted that Mrs. Belloc Lowndes’s young ladies enjoy singularly poor luck, as is shown notably by their habit when in foreign parts of picking up the worst people and generally surrounding themselves with a society that it would be flattery to call dubious. The latest victim to this tendency is Lily, heroine of The Lonely House (Hutchinson). It was situate, as you might not expect from its name, at Monte Carlo, and Lily had come there as the paying guest of a courtesy uncle and aunt of foreign extraction, about whom she really knew far too little. They had tried to postpone her visit at least for a couple of days, the awkward fact being that the evening of her arrival was already earmarked for an engagement that Auntie euphemistically called “seeing a friend off on a long journey.” If you know Mrs. Belloc Lowndes at her creepiest, you can imagine the spinal chill produced by this discovery. Gradually it transpires (though how I shall not say) that whenever the Count and Countess Polda were in want of a little ready cash they were in the habit of “seeing off” some unaccompanied tourist known to have well-filled pockets. So you can suppose the rest. If I have a criticism for Mrs. Lowndes’ otherwise admirable handling of the affair it is that she depends too much on the involuntary eavesdropper; before long, indeed, I was forced to conclude either that Lily possessed a miraculous sense of overhearing, or that the acoustic properties of the lonely house rendered it conspicuously unsuited for the maturing of felonious little plans. But this is a trifle compared with the delights of such a feast of first quality thrills.

The extraordinary cleverness of A Woman’s Man (Heinemann) is the thing which most impresses me about this life story of a French man of letters, at the height of his fame somewhere in the eighteen-nineties. He is made to tell his own story, and pitfalls for the author must have abounded in such a scheme, but Miss Marjorie Patterson seems to have fallen into very few of them. Armand de Vaucourt is a self-deceiving sensualist who justifies his amours as necessary to literary inspiration and neglects his wife only to find, too late, that she has been his guardian angel, her love the source of all that was worth while in his life and work. There have been such characters as Armand in fiction who yet made some appeal to the reader’s affection; it is the book’s worst defect that Armand makes none. His recurring despairs and passions grow tedious; his final but rather incomplete change of heart left me sceptical as to how long it would have lasted had the book carried his history any further. Armand as a study of a certain type of egoist is supreme; my difficulty was that I had no desire to study him. Even Maria-Thérèse Colbert, the decadent wife of his publisher, a very monster among women, is more interesting. Miss Patterson is on the side of the angels, but she makes her way to them through some nasty mire, calling spades spades with a vigour which seems to have prevented her from paying much attention to some beautiful and hopeful things which also have everyday names.

Germany’s High Sea Fleet in the World War (Cassell), which is Admiral Scheer’s addition to the entertaining series, “How we really won after all,” by German Military and Naval commanders, gives you, on the whole, the impression of an honest sailor-man telling the truth as he sees it and only occasionally remembering that he must work in one of the set pieces of official propaganda. To a mere layman this record is of immense and continual interest; to the professional, keen to know what his opposite number was doing at a given time, it must be positively enthralling, especially the chapter on the U-boats, with its discreet excerpts from selected logs. Incidentally one can’t withhold tribute of reluctant admiration for the technical achievements of the submarines and the courage, skill and tenacity of their commanders and crews. Most readers will find themselves turning first to the account of the Jutland battle. The tale is told not too boastfully, though the Admiral claims too much. Perhaps that may be forgiven him, as he certainly took his long odds gamely and fought his fleet with conspicuous dexterity. Also the German naval architects and ordnance folk proved to have a good thing or two up their sleeves, and the gunnery, for a time at any rate, was unexpectedly excellent. Naturally perhaps Admiral Scheer may be claimed as supporting the Beattyites rather than the Jellicoists. But he is biassed and goes further than the most extreme of the former school. For his real grievance against the British Navy, constantly finding vent, is that it did not ride bravely in, with bands playing, to the perfectly good battleground prepared with good old German thoroughness under the guns of Heligoland.

No pioneer work was ever more persistently attacked by the weapons of ridicule and contempt than that of the Salvation Army, and I suggest that all who sat in the hostile camp should read William Booth, Founder of the Salvation Army (Macmillan), and see for themselves what ideas and ideals they were opposing. Mr. Harold Begbie has done his work well, and the only fault to be found with him is that his ardour has sometimes beguiled him into recording trivialities; and this error strikes one the more as Booth, both in his strength and in his weakness, was not trivial. When this, however, is said, nothing but praise remains for a careful study both of the man and of his methods. The instrument upon which Booth played was human nature, and he played upon it with a sure hand because he understood how difficult it is to touch the spirit when the body is suffering from physical degradation. To this must be added a genuine spiritual exaltation and love of his fellow-man and also an indomitable courage. Few men could have emerged with hope and enthusiasm unquenched from such a childhood as Booth’s; but we know how he lived to conquer all opposition and to promote and organise what is perhaps the greatest movement of modern times. In paying our tribute to him for his successful crusade against misery and evil we are not to forget his wife, whose unfailing love and devotion were his constant support.

Mr. John Galsworthy’s short stories and studies in Tatterdemalion (Heinemann) are divided into “of war-time” and “of peace-time.” I think the greater part of the author’s faithful company of readers will prefer the latter. Mr. Galsworthy has less than most men the kind of mind that can put off the burden of the suffering of war or submit easily to the difficult need for us all to think one way in a time of national crisis. But “Cafard,” study of a poilu in the despairing depression that comes of the fatigue and horror of long fighting, who is lifted back to courage by a little frightened beaten mongrel whose confidence he wins, so forgetting his own trouble, was written, one can feel, because the author wanted to write it, not because he felt it was expected of him. Of the peace-time sketches “Manna,” with the theme of a penniless and eccentric parson charged with stealing a loaf of bread and acquitted against the evidence, is as admirable as it is unexpected in flavour. For the rest there is good Galsworthy, if not of the very best, and but little that one would not praise highly if it came from an author of lower standards.

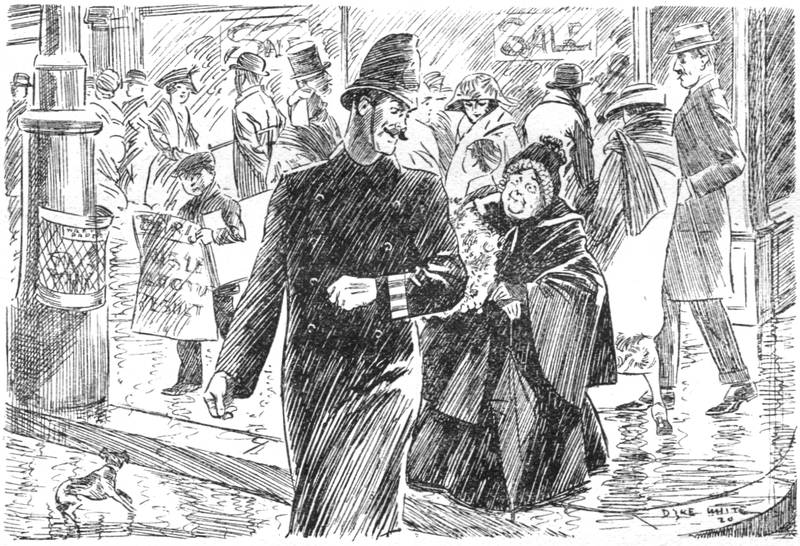

Dear Old Soul. “Thank you very much for bringing me across. I do so hope you’ll get safe back again.”

Three members, quite immune to scowl or snub,

Disturbed the quiet of the selfsame club;

The first in resonance of snore surpassed,

The next in raucousness, in both the last.

Patience, exhausted, heaved a futile sigh;

No force can cure them and they will not die.

***END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI, VOL. 158, MAY 12, 1920***

******* This file should be named 24095-h.txt or 24095-h.zip *******

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/4/0/9/24095

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://www.gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the