CARRIED OFF

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Carried Off

A Story of Pirate Times

Author: Esmè Stuart

Release Date: August 06, 2012 [EBook #23892]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CARRIED OFF ***

Produced by Al Haines.

CARRIED OFF

A STORY OF PIRATE TIMES

BY

ESMÉ STUART

AUTHOR OF 'FOR HALF-A-CROWN' 'THE LAST HOPE'

'THE WHITE CHAPEL' ETC.

WITH FOUR FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

NATIONAL SOCIETY'S DEPOSITORY

BROAD SANCTUARY, WESTMINSTER

NEW YORK: THOMAS WHITTAKER, 2 & 3 BIBLE HOUSE

1888

TO

CLARISSA AND JOHN

I dedicate this story, knowing they are already fond of travelling. They may be glad to hear that the chief events in it are true, and are taken out of an old book written more than two hundred years ago. Yet they may now safely visit the West Indies without fear of being made prisoners by the much dreaded Buccaneers.

E.S.

[All rights reserved]

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

CARLO REFUSED ADMISSION (missing from book)

'SHALL WE LAND?' (missing from book)

CARRIED OFF.

CHAPTER I.

THE SACRIFICE.

It was a beautiful warm spring evening, and as the sun sank slowly in the west it illuminated with quivering golden light the calm waters that surrounded green, marshy Canvey Island, which lies opposite South Benfleet, in the estuary of the Thames.

Harry Fenn had just come out of church, and, as was often his wont, he ran up a slight hill, and, shading his eyes, looked intently out towards Canvey and then yet more to his left, where Father Thames clasps hands with the ocean.

The eminence on which young fair-haired Harry stood was the site of a strong castle, built long ago by Hæsten, the Danish rover, in which he stowed away Saxon spoil and Saxon prisoners, till King Alfred came down upon him, pulled down the rover's fortress, seized his wife and his two sons, and relieved the neighbourhood of this Danish scourge. How often, indeed, had the peaceful inhabitants trembled at the sight of the sea robber's narrow war-vessels creeping up the creek in search of plunder!

Harry, however, was not thinking of those ancient days; his whole soul and mind was in the present, in vague longings for action; full, too, of young inquisitiveness as to the future, especially his own future, so that he forgot why he had come to this spot, and did not even hear the approach of the Rev. Mr. Aylett, who, having been listening to a tale of distress from one of his parishioners at the end of the evening service, had now come to enjoy the view from Hæsten's hill. As he walked slowly towards the immovable form of the boy, he could not help being struck by the lad's graceful outline; the lithe, yet strongly built figure, the well-balanced head, now thrown back as the eyes sought the distant horizon; whilst the curly fair locks appeared to have been dashed impatiently aside, and now were just slightly lifted by the evening breeze; for Harry Fenn held his cap in his hand as he folded his arms across his chest. He might have stood for the model of a young Apollo had any artist been by, but art and artists were unknown things in South Benfleet at that time.

Mr. Aylett shook his head as he walked towards the lad, even though a smile of pleasure parted his lips as he noted the comeliness of his young parishioner, whom he now addressed.

'Well, Harry, my boy, what may be the thoughts which are keeping you so unusually still?' Harry started and blushed like a girl, and yet his action was simple enough.

'Indeed, sir, I did not hear you. I--I came here to have a look at our cows down on the marsh. Father----'

Mr. Aylett laughed good-humouredly.

'Am I to believe that that earnest look is all on account of the cattle, Harry?' Harry felt at this moment as if he had told a lie, and had been found out by Mr. Aylett, who was so good and clever that he could almost, nay, sometimes did, tell one's thoughts.

'No, sir;' then, with a winning smile, the lad added, 'in truth I had forgotten all about the cattle. I was dreaming of----'

'Of the future, Harry. Listen, did not those same thoughts run thus? That it is dull work staying at home on the farm; that some of thy relations in past days had famous times in our civil wars, and went to battle and fought for the King, and that some even had been settlers in the old days of Queen Bess, and that, when all is said and done, it wants a great deal of self-denial to stay as thou art now doing, cheering the declining years of thy good father and mother. Some such thought I fancied I could read in your face, boy, when singing in the choir just now. Was it so? I would have you use candour with me.'

Harry turned his cap round and round slowly in his hands. Mr. Aylett was certainly a diviner of thoughts; but Harry was far too honest, and of too good principle, to deny the truth. It was his honesty, as well as his pluck and courage, that made him so dear to the clergyman, who had taught the boy a great deal more learning than usually fell to the lot of a yeoman's son in those days, even though Mr. Fenn farmed his own land, was well-to-do, and could, had he so willed, have sent his son to Oxford; but he himself had been reared on Pitsea Farm, had married there, and there he had watched his little ones carried to the grave, all but Harry. Yes, Harry was his all, his mother's darling, his father's pride; the parson was welcome to teach him his duty to his Church, his King and his country, and what more he liked, but no one must part the yeoman from his only child.

And Harry knew this, and yet often and often his soul was moved with that terribly strong desire for change and for a larger horizon, which, so long as the world lasts, will take possession of high-spirited boys. However, the lad was as good as he was brave; he knew that he must crush down his desire, or at least that he must not show it to his parents; but he did not try to resist the pleasure of indulging in thoughts of a larger life, thoughts which Mr. Aylett guessed very easily, but which would have made his father's hair stand on end. This evening Mr. Aylett's face looked so kind that Harry's boyish reserve gave way, and with rising colour he exclaimed:

'Oh, sir, I can't deny it; it is all true, that, and much more; just now I had such dreadful thoughts. I felt that I must go out yonder, away and away, and learn what the world is like; I felt that even father's sorrow and mother's tears would not grieve me much, and that I must break loose from here or die. I know it was wicked, and I will conquer the feeling, but it seems as if the devil himself tempts me to forget my duty; and worse,' added poor Harry, who having begun his confession thought he would make a clean breast of it, 'I feel as if I must go straight to my father and tell him I will not spend my life in minding cattle and seeing after the labourers, and that after telling him, I would work my way out into the big world without asking him for a penny. Sir, would that be possible?'

Harry looked up with trembling eagerness, as if on this one frail chance of Mr. Aylett's agreement depended his life's happiness; but the clergyman did not give him a moment's hope.

'No, Harry, that is not possible, my lad. You are an only child. On you depends the happiness of your parents. This sacrifice is asked of you by God, and is it too hard a matter to give up your own will? Look you, my dear Harry, I am not over-blaming you, nor am I thinking that the crushing of this desire is not a difficult matter, but we who lived through the late troublous times see farther than young heads, who are easily persuaded to cozen their conscience according to their wishes. And if you travelled, Harry, temptations and trials would follow too, and be but troublesome companions; and further, there would be always a worm gnawing at your heart when you thought of the childless old folks at home. Believe me, Harry, even out in "the golden yonder," as some one calls it, you would not find what you expect; there would be no joy for you who had deprived those dependent on you of it. Take my advice, boy, wait for God's own good time, and do not fall into strong distemper of mind.'

Mr. Aylett paused and put a kind hand on the boy's shoulder. Harry did not answer at once, but slowly his eyes turned away from the waters and the golden sun, slowly they were bent upon the marshes where the cattle were grazing, and then nearer yet to where Pitsea Manor Farm raised its head above a plantation of elms and oaks. Then a great struggle went on in the boy's mind; he remembered he was but sixteen years old, and that many a year must most likely elapse before he became the owner of Pitsea Farm and could do as he pleased, and that those years must be filled with dull routine labour, where little room was left for any adventure beyond fishing in the creek, or going over to Canvey Island to watch when the high waves broke over the new embankments made by Joas Croppenburg, the Dutchman, whose son still owned a third of the rich marshland of the island as a recompense for his father's sea walls. But young Joas used to tell tales of great Dutch sea fights and exploits, which, if Harry made the sacrifice Mr. Aylett was asking him to make, would but probe the wound of his desire, and so Croppenburg's stories must also be given up.

Harry's courage, however, was not merely nominal, it was of the right sort. The sacrifice he was asked to make was none the less great because it was one not seen of men. He was to give up his will, the hardest thing a man or a boy can do; but it needed only Mr. Aylett's firm answer to show Harry that his duty was very plain, and that God required this of him.

It was like taking a plunge into cold water, where it is the first resolution that is the worst part of the action; suddenly, with a quick lifting of his head, and a new hopeful light in his blue eyes very different from the unsatisfied longing gaze of ten minutes ago, Harry spoke, and as he did so his clenched hands and his whole demeanour told plainly that the boy meant what he said.

'I will give it up, sir; as it is, the wishing brings me no happiness, so I will even put the wishing to flight.'

Mr. Aylett grasped the lad's hand warmly.

'God bless you, Harry, you are a brave fellow. I am proud of you. Come to me to-morrow, and I will show you a new book a friend has sent me; or, better, walk back with me to the Vicarage.'

'I would willingly, sir,' said Harry quietly, 'but father bade me go to the meadow and see if White Star should be driven in under shelter to-night. Our man Fiske has met with an accident, so I promised to see after White Star before sundown. She was a little sick this morning.'

'To-morrow will do well enough,' said Mr. Aylett, glad to see that Harry was beginning already to turn his mind steadily to home matters, 'and if you have time we will go to St. Catherine's Church on Canvey. There is a young clergyman come there to see if he will accept the cure, and I know you will row me over.' Harry promised gladly, and then Mr. Aylett with another shake of the hand turned his face homeward. When he was gone Harry flung himself on the ground to think over the promise he had just given. He would--yes, he would keep his word.

CHAPTER II.

CAPTURED.

How long he lay there, Harry never could recollect afterwards, but feeling a chilliness creeping over him he suddenly remembered his duty. He must make haste, for the sun was setting, and if White Star did not seem to be better she must be led home from the damp marsh meadows that bordered the water. Though Harry was feeling intensely sad, he had a secret feeling of satisfaction at having conquered in a very hard struggle, and this perhaps made him look more at the things he was passing than, as he was wont to do, at the distant sea. This evening everything was calm and quiet, both on the darkening waters and on the green meadows. Harry noted a gate that needed repairing, and made up his mind to tell his father that it must be seen to, or the cattle would be straying; then he glanced at the little cart-horse foal that promised to be a rival of its mother. The Pitsea Farm cart-horses were deservedly famous, and Harry's father, George Fenn, was as good a breeder of horses as he was a staunch Churchman and opposed to the Puritan element only now quieting down.

At last Harry reached the meadow where White Star was grazing and where some thirty sheep were sharing the pasture. He went up to examine the gentle creature, and she knew well enough the young master's voice and touch, so that she hardly stopped chewing the cud to give him a kindly stare.

'White Star seems not so bad,' thought Harry. 'I'll tell father to give her another day in the meadow, she is not too ill to enjoy this sweet grass.'

Harry had been so much engaged in attending to White Star that he did not hear the soft splash of some oars at the bottom of the meadow he was in, nor did he see that four strong, rough-looking men in seafaring attire had quietly moored their long-boat to an old willow stump, and that two of them were hastily scanning the sheep and cattle that were only a few yards away.

'Zounds!' muttered the first who stepped up the bank, 'what have we here? a lad in this very field. I'faith, I saw no one from the creek.'

'A mere sapling,' laughed the other, 'take no heed of him, and he will soon take to his heels at the sight of us. Now, quick's the word, the captain is impatient to be off with the tide.'

In another instant the men had begun their work. They had come for the purpose of carrying off some sheep and cattle, and having waited till this late hour they had not expected to find a witness to their robbery. Quietly and stealthily as they had landed, however, their intentions could not be carried out without some disturbance, and Harry was first made aware of their presence by the sudden helter-skelter of the sheep and the immediate curiosity expressed by poor White Star, whose evening meal was to be so violently disturbed.

In a moment more Harry had seized the situation, which indeed it was not difficult to do, as he now beheld one of his father's sheep suddenly captured by the clever expedient of an extemporised lasso, and when the poor animal had been dragged towards its captor the robber made short work of tying his victim's legs together, and leaving it to bleat beside him whilst he proceeded to capture another in the same manner, before dragging them to the long-boat.

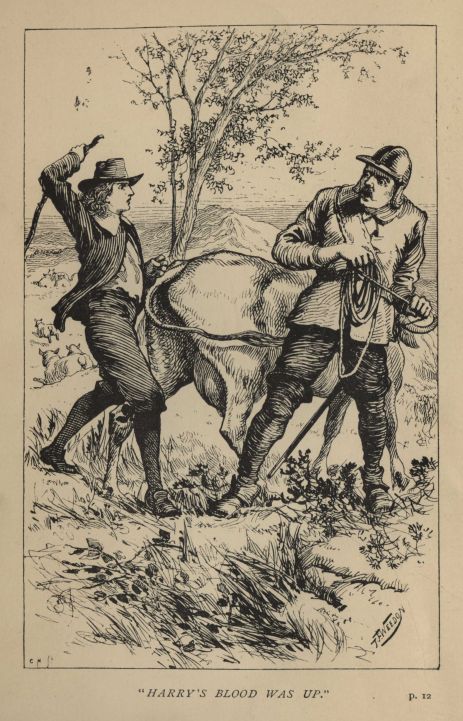

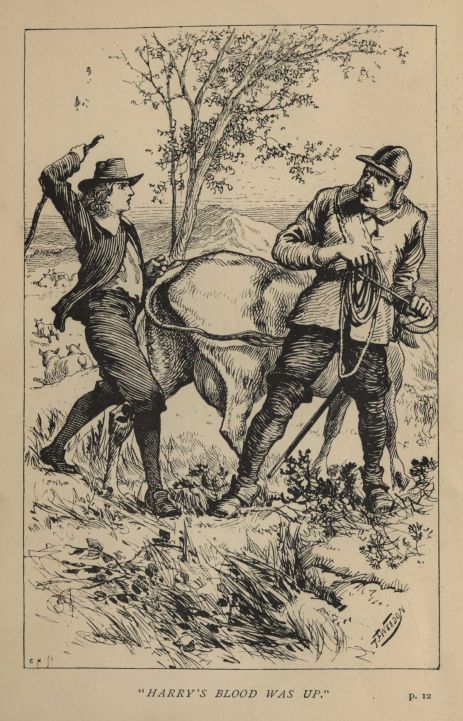

All the fierce courage of the hardy yeoman's son rose to its height as he beheld this daring robbery carried on under his very eyes. Nay, when the strongest and foremost man began unconcernedly to make his way towards White Star herself, the boy's indignation knew no bounds.

'How now?' he cried indignantly. 'What do you mean, you rascals, by coming here? this is our field and our cattle; away at once, and unloose the sheep, or, by'r laykin! it will be worse for you. I will call for help, and you will soon be treated in such a manner as you deserve.'

This fierce speech had not, however, the desired effect. The man laughed ironically as if Harry were a mere baby, and approaching White Star he swiftly threw the lasso over the animal's sleek head.

'Out of the way, young blusterer, or it will be the worse for thee. Our master, the captain, requires these cattle to victual our ship before sailing; come, off with thee! and don't halloo all the breath out of thy body.'

But Harry's blood was up. Enraged at the man's daring and effrontery, he seized a stout stick from the hedge-row and sprang upon the intruder with the fury of a young lion. He never considered the inequality of the struggle or the folly of his engaging single-handed with a ruffian of this description; he only thought of saving his father's property and avenging the insult. Nor were his well-directed blows mere make-believe, and as the man before him was suddenly aware of a sharp stinging pain across his forehead, he let go the lasso and sprang on to the boy with a fierce oath.

'What, you young viper, you dare to strike me? Well, take that. Here, Jim, this way, bring the rope here; I'll teach this churl to bethump me.'

As he spoke he wrenched away poor Harry's stick, and with a well-directed blow he laid the boy on the ground. Harry felt a terrible pain in his head, his brain seemed to reel; bright, blood-red flashes blotted out the familiar fields, and then with a groan of pain he stretched out his right arm to grasp at some support, after which he remembered no more.

The man appealed to as Jim had now run up, and laughed as he saw Harry fall insensible on the dewy grass.

'Bravo! the lad fell in fair fight, Joseph; but i'fecks! who would have thought of seeing you engaged in a hand-to-hand struggle with such a stripling? Hast done for him, comrade?' he added with curiosity, in which was mingled neither pity nor fear. And yet the sight of Harry Fenn might have softened even a hard heart, one would have thought, as he lay there in the twilight on the dewy grass, whilst a slow trickling line of red blood fell from his forehead over his fair curling hair.

'Here, make haste,' said the first man, whom his friend addressed as Coxon, 'the captain's orders were that we must lose no time; there'll be several more trips this evening, and he means to run down the Channel before morning.'

'Then we'd best not leave the lad here. What say you, Coxon, shall I despatch him for fear of his waking up and telling tales before we return?'

Coxon looked down on the brave lad, and decided, he knew not why, to act more mercifully.

'Let him be, or wait--tie his legs and throw him in the long-boat; on our ship he'll tell no tales, and when we cast anchor we can drop him somewhere, or give him a seaman's burial if he's dead, for, to tell the truth, it was a good whack that I dealt him. Now, Jim, quick, for fear some of those land dolts come down upon us, and deafen us with their complaints.'

After this quick certainly was the word. Harry was tied, much after the fashion of his own sheep, and cast with little ceremony into the long-boat; further booty was secured, till no more could be carried during this trip, and then, as silently as it had come, the boat was rowed swiftly down the creek till they reached their destination, namely, the good ship 'Scorpion,' a privateer bound for the West Indies, after having lately made a very successful bargain with the cargo it had safely brought home.

How long Harry remained unconscious he never knew: when he came to himself it was some time before he could collect any sequence in his thoughts. He felt, however, that he was in a cramped and confined place, and so put out his hands to make more room, as it were, for his limbs; but he could give no explanation to himself of his whereabouts, though he half realised that the night air was blowing in his face, and that something like sea spray now and then seemed to be dashed on his head. His hands were free, but what of his legs? He experienced a sharp cutting pain above his ankles, and with some difficulty he reached down to the seat of pain with one of his hands. Yes, there was a rope tied round his legs; who had done this, and where was he? He remembered standing on Hæsten's mound looking longingly at the sea, and he also recalled Mr. Aylett's words and his own fierce struggle against his strong inclinations, and then--what had followed?

Here for a long time his mind remained a blank, till a decided lurch forced the conviction upon him that he was certainly in a ship, not on the green marsh meadow at home.

Home! He must make haste and get home; his father would wonder what kept him so long, it was quite dark; how anxious his fond mother would be. He must at once get rid of that horrid thing that prevented his rising, and he must run as fast as he could back to Pitsea Farm. But what of White Star? White Star, the meadow, the--the----

All at once the scene of his conflict flashed into his mind, and the awful truth burst upon him. He was a prisoner in some enemy's ship--or could it be in one of those dreadful privateers, whose ravages were often spoken of, and whom Mr. Aylett had said ought to be put down by Government with a firm hand? Ay, and those ruffians who had treated him with such brutality, they must be no other than some of those dreaded buccaneers, whose atrocities in the West Indies made the blood of peaceable people run cold, and wonder why God's judgments did not descend on all who abetted such crimes. Harry, as we know, was very brave, and yet he shuddered as the truth forced itself on his mind; it was not so much from a feeling of fear, but because, to the boy's weak, fevered brain, the terrible calamity that had overtaken him seemed to be, as it were, a punishment for his old and secret longings, and his discontent at the dull home life.

Then followed a period of great mental pain for the boy, and after having vainly tried to free himself, he lay back utterly spent with the exertion, and with the feeling that perhaps he was reserved for worse tortures. Harry had heard many and many a terrible story of the doings of these buccaneers, who plundered, without distinction, the ships of all nations, and amassed treasures in the West Indies and the Spanish Main, and whose inhuman conduct to their prisoners was not much better than that experienced by the unfortunate Christian prisoners from the pirates of Algiers. Harry's courage was nearly giving way at these thoughts, and as no one was by to see him a few bitter tears rolled down his cheeks; but as he put up his hand to brush them away he suddenly felt ashamed of his weakness.

'God helping me,' thought he, 'whatever these rascals call themselves they shall not see me in tears, be the pretence never so great; it were a pretty story to take back to my father and good Mr. Aylett, that I was found weeping like a girl; but all the same I wish they would give me something to eat. In truth I could devour very willingly a sirloin of beef if it were offered me.'

Hunger is but a melancholy companion, and as the time still passed on and no one came near him, though Harry could hear the tramp of feet above him distinctly enough, the boy began to fear he should be left to die of slow starvation; and though this idea was very fearful to a growing lad, yet he determined that even this suffering should not make him cry out, and, clenching his teeth together, he lay down again and tried to say a few mental prayers. Evidently he must have dozed off, for the next thing he remembered was the sound of a rough voice telling him to get up; at the same time the rope that tied his feet was hastily cut and he felt himself led along a dark passage and pushed up a hatchway, feeling too dazed and weak to notice anything till he was thrust through the door of a small cabin.

By this time Harry's spirit had returned; he forgot his pain and his hunger, and, straightening himself, tried to wrench his arm away from the iron grasp of the sailor that led him.

'What right have you fellows to keep me prisoner here?' cried Harry. 'But as we are upon the high seas it's not likely I can escape, so you need not pinion me down in this fashion.'

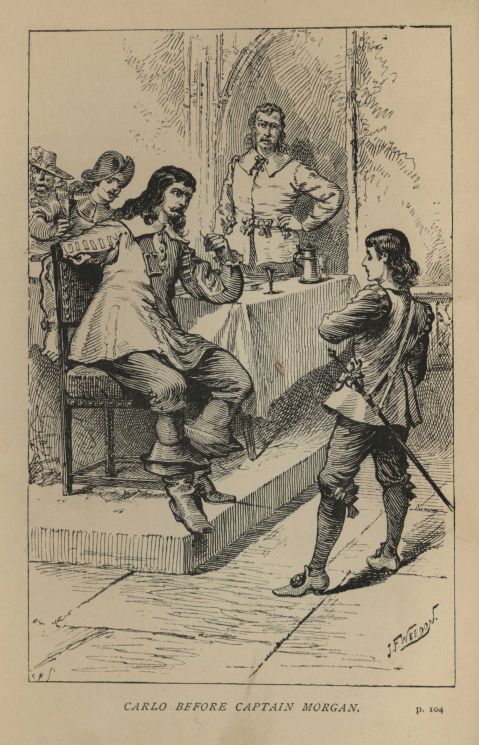

At this moment a tall, powerful, and very handsome man entered the cabin, and, hearing Harry's words, burst into a loud and cheerful laugh.

'What, Mings! is this the boy you spoke of? By my faith, you have caged a little eaglet! But we can soon cut his claws and stop his pretty prating. How now, boy: answer truly, and tell me thy name; for we are no lovers of ill-manners and insolence.'

Harry Fenn had been struck dumb by the appearance of the new comer, so that he had ceased struggling with Mings, and now gazed at the courtly-looking man, whose whole bearing spoke of a certain rough refinement and assured courage, such as Harry had believed attainable only by a gentleman of birth and breeding. Evidently the man before him was the captain of the crew, but he was no mere rough sailor such as Harry had often seen at home; on the contrary, his dress was both rich and elegant; he wore his hair in flowing locks just below his neck; a cravat of muslin edged with rich lace was round his throat, and the ends of the bow hung over his thick doublet, which was embroidered in a running pattern. His scarf, thrown over one shoulder and tied at his waist, was heavy with gold embroidery and fringe, and the sword that dangled at his side was evidently of Spanish make, and richly chased. As to his countenance, the more Harry gazed the less he could believe this man had anything to do with the buccaneers of the West Indies he had heard so much about, for the Captain's expression was open, and even pleasant. His eyes were of a pale blue, shaded by soft and reddish eyebrows; his nose straight and well formed; and though his mouth was somewhat full and coarse, yet there was nothing bad-tempered about it; and the curling moustache and small tuft of hair on his chin reminded one of a jolly cavalier more than of a dreaded sea-captain. Yes, Harry fancied he might be mistaken, and that this gentleman was in truth a loyal captain of His Majesty's Navy, and that his own capture was all some terrible mistake. This idea gave him courage, and, shaking himself free from his jailor, he advanced boldly towards the handsome-looking man, who surely must be the soul of honour, and no enemy to the public.

'Oh, sir, I fancied I had fallen into the hands of evil men; but surely I am mistaken, and you will see justice done me. I am a yeoman's son. My name is Harry Fenn, and my father owns a farm at South Benfleet. I had but gone down to see after one of our cows who had been sick, when suddenly your men waylaid me when I defended our cattle, and used me in a brutish manner. Had they wanted to buy cattle, my father could have directed them to those willing to sell. I did but my duty in defending my father's property, and I doubt not that they gave you quite a wrong tale of my behaviour; but indeed, sir, it was not true, and though I have been treated very roughly I beg you to see justice done to me, and to have me landed on our English coast; for my parents will be sadly put about on account of my disappearance, and very solicitous about my safety.'

Harry paused, expecting the handsome captain to express his regret at what had happened. Instead of this, his words were received with a loud laugh by Mings; and apparently they also much tickled the fancy of the Captain, for he joined in the merriment, though he looked with kindly eyes on the handsome youth, who, in spite of his being a good deal bespattered with mud and blood stains, was yet a very pleasant picture of a bold, fearless English boy.

'Thou art over-bold, young fellow,' said Mings when he had laughed heartily. 'Doubtless our captain will teach thee how to mind thy speech. Shall I stow the lad away, sir, in the hold? I take it he will come forth in a humbler frame of mind, and with less zeal for defending cattle.'

'Nay, Mings, leave him to me; such a home bird is an uncommon sight, and having fallen on deck for want of a stronger wing, he must needs stay aboard. Go and attend to the guns, and tell the watch to keep a sharp look-out for any strange sail, and I'll see to the boy.'

Mings appeared a little sulky at this order, and took the opportunity of roughly grasping Harry's shoulder as he went by, with the remark:

'Keep a civil tongue in thy head, young scarecrow, or Captain Henry Morgan will soon teach thee to wag it less glibly. It would want but a small gun to blow thee back to the English shore if thou art so anxious to get back--eh, Captain?'

The Captain frowned instead of answering, and Mings made off as quickly as possible; but by this time Harry had recovered from his surprise.

'Then it's true,' he said quickly; 'you are in truth the infamous Henry Morgan the buccaneer, whose name is a terror to all honest folk. I only hope one of His Majesty's men-of-war will give chase, and I will do all in my power to give information. It is a dastardly act that you have done, for you have stolen our property and allowed your men shamefully to ill-use me.'

Harry never stayed to think how unwise his words were: he was so angry at having made a mistake and having fancied this courtly man was an honest gentleman, that he cared nothing at the moment about the consequences of his violent language; indeed, he was all the more furious when he noticed that Captain Morgan seemed only amused by his burst of indignation.

'Thou art a brave lad, and I like to see thy spirit. Tell me thy name. I wager it is an honest one.'

'Ay, truly. Harry Fenn is my name--an honest English yeoman's son, and one that will receive no favours from a buccaneer,' answered Harry, crossing his arms.

'Then thou art my namesake, lad, i' fecks! See, I'll forgive thy hasty words, and take thee for my godson. As for thy parents, well, they must take the chances of war as others do, for there can be no putting back to land now. We had to be very crafty to avoid a large three-decker of sixty-four guns that, I fancy, had scent of my poor frigate; but we ran up the French flag, and so got off; and now we are making a very fair journey towards Jamaica. Art hungry, lad? There's no use lying about thy stomach, for it's a hard taskmaster, and, now I come to think of it, no one has heeded thee or thy wants since the cutter put thee aboard.'

Hunger was indeed a very hard taskmaster for at this moment Harry Fenn felt a dizziness which he could hardly control, and he half fell on a bench which was beside him, and against which he had been leaning. Captain Morgan continued:

'Come, Harry Fenn, you're a brave lad, and we'll strike a bargain. I've taken a fancy to you, my boy, and I'll try and protect you from the sailors. We are rough people at times, but not so bad as we're painted; so if you'll work like the rest, I'll warrant you good provender and as merry a life as we sea-folk know how to lead.'

'I will not work for such as you,' said Harry boldly; 'my father brought me up in honest ways. I would rather die than join hands with such men as your crew.'

'By my troth, boy, you are ignorant of our good deeds, I well see,' said Captain Morgan. 'Many of those in power are glad enough of our inroads on the Spanish Settlements, for those rogues get only their deserts if we make them discharge a little of their gold. Hast never heard of our worthy predecessors? The authorities were less squeamish in those days, and called the deeds of bold men by fine names, whereas now, in truth, it is convenient to dub us buccaneers. There was Sir Thomas Seymour, and before him there were fine doings by Clarke's squadron. By St. George, he was a lucky man! and after six weeks' cruise he brought back a prize of 50,000*l.* taken from the Spaniards. And how about Drake, Hawkins, and Cavendish? There were no ugly names hurled at them, and yet methinks they and we go much on the same lines. In truth we have done good service also against those rascally Dutch, and for that alone we deserve better treatment than we get.'

Captain Morgan now noticed that Harry had become deadly pale, and, hastily rising, the buccaneer opened a locker and took from it a black bottle, the contents of which he poured into a glass.

'Here, lad, thou art faint; this will revive thy courage. But first swear that thou wilt be one of us.'

Harry had eagerly stretched forth his hand to take the glass, but at these words he drew back.

'Nay, but I will not swear; if God wills, I can die, but I will not sully my father's name.'

Captain Morgan frowned angrily, and, striding up to Harry, took hold of his arm with his left hand, and with his right seized the hilt of his sword as he exclaimed--

'Swear, boy, or it will be worse for thee.' Harry Fenn made one last great effort and staggered to his feet; then with his right hand he struck the glass with as much strength as he possessed, and saw the red wine spurt out upon the floor and upon the Captain's doublet.

'God helping me, I will not swear,' he cried; but the words were barely audible, as he fell fainting on the floor.

'As brave a lad as I ever cast eyes on!' said the Captain, losing his stern expression, and, stooping down, he poured a few drops of the wine into Harry's mouth; then, calling for the cook, he bade him tend the boy till he should have regained his strength.

'Harry Fenn shall be under my protection,' said the Captain to himself, 'but in time he must be one of us.'

CHAPTER III.

A BEAUTIFUL ISLAND.

It is the beginning of December 1670 in the beautiful little Island of St. Catherine, one of the West Indian Islands, which were at this time the rich treasure-house of most of the European nations, where Spaniards, French, English, and Dutch all hoped to make their fortunes in some way or other, and where, alas! the idle and good-for-nothing men of the Old World attempted by unlawful means to win fame and fortune, which, when achieved, as often as not brought them neither happiness nor profit.

Though it is December, in St. Catherine there is nothing cold or disagreeable in the weather, and all around the beauty of the scene delights the eye. The mountains, though of no great height, are wooded with the loveliest tropical vegetation; the well-watered valleys are little Gardens of Eden; whilst in some portions, not yet cleared by either natives, Spaniards, or Englishmen, the original forests rise up like giants of nature whom no hand of man has laid low. In these forests are endless varieties of birds--parrots, pigeons, and hummingbirds of every colour. Here, too, can be found land-crabs which much resemble sea-crabs in shape and manner of walking; but instead of finding a home under rocks and boulders, these crabs burrow in the forests, and once a year form themselves into a regiment and march down to the sea-coast for the purpose of depositing their young in the waters. This regiment has only one line of march; it never diverges from it, but whatever comes in its way is climbed over--straight over it go the crabs; and such a noise they make that you can hear the clattering of their claws for a considerable distance.

We must not now stop to describe this West Indian island, which is full of beauty and curious plants and trees; but if you come to the wood that leads to the great Spanish fortress of Santa Teresa, you will find a steep path through the luxurious forest, leading over a drawbridge to the castle. What a view can be seen from thence over the port! But it was not the view that the Governor's children were thinking of as they walked together in the garden which sloped down towards the sea, and which was especially reserved for the Governor and his family.

Felipa del Campo was a tall dark girl of about fourteen years of age, but she looked older, and there was a sad expression on her face as she gazed up to her brother, a noble-looking fellow a year older, with the long, grave-looking countenance of the Spanish nobility. He was dressed, after the fashion of that time, in embroidered doublet, short velvet tunic, and trunk hose; whilst his well-shaped limbs were displayed to perfection in silk stockings. His shoes had buckles set with diamonds, and his tall Spanish hat was plumed.

Felipa, on her side, had a long silver-embroidered skirt, beneath which her dainty feet hardly appeared; a small stomacher sewn with seed pearls set off her lithe figure, whilst her pretty, dark hair strayed from beneath a rich black lace kerchief.

'Where is my father, Carlo?' asked Felipa. 'Old Catalina says he has been down to-day to give orders about the repair of the bridge between the two islands. Do you think he is expecting any danger? Surely the forts are well protected; but what can make him so busy?'

'I don't know what to think,' said Carlo sadly, 'our father is so strange of late. I have been trying to speak to you about it, Felipa, for several days, but sometimes I fancy he seems to watch me as if he suspected me; though of what I cannot imagine. And then--have you noticed?--he cannot make up his mind to anything; he orders something one day, and the next he has altered his mind. He promised me the command of the little fort of Santa Cruz when I should be fifteen; but this morning when I reminded him of this he spoke quite roughly, and told me I was fit for nothing but playing with girls.'

Carlo's colour heightened at the very idea of this rebuke; for if there was one virtue the boy admired more than any other it was courage. These two children had been early left motherless; but old Catalina, a faithful servant, had done all she could to make their lives happy since she had brought them here from Spain, after the Marquis Don Estevan del Campo had been made Governor of St. Catherine.

'Catalina says that our father is not the same man he was when our mother first married him,' said Felipa thoughtfully. 'The many worries he has have made the change. But never mind, Carlo, this mood will pass by, and we shall be happy again. When our brave uncle, Don Alvarez, comes with dear Aunt Elena, then they will advise our father, and he always takes Uncle Alvarez's opinion. He always does, because uncle speaks so decidedly.'

The two children spoke in Spanish, but, strangely enough, they often put in English words and whole English phrases; and the reason of this was soon apparent, for at this moment a pretty, fair girl was seen running towards them with nimble feet down the slope, and, picking her way among the gorgeous flower-beds, she cried out in pure English, though with a slightly foreign accent:

'Dear Felipa, what do you think! There is a trading-vessel in the port, and the merchant has just come to offer us some beautiful cloth, and silver buckles! Catalina dares not send him away till you have seen him.'

Carlo smiled as he looked at the English girl's beautiful fair hair, rosy cheeks, and active limbs. To him she appeared like some angel, for he was accustomed to seeing only dark people, and the Spanish women in the island were anything but beautiful. Felipa shook her head as she answered:

'Tell Catalina to say I want nothing.' The Governor's daughter spoke with just that tone of command which showed she was accustomed to be first, even though her gentle manner and sad face plainly indicated that her real nature was rather yielding than imperious.

'I can see Etta admired the silver buckles,' said Carlo kindly. 'Come, Mistress Englishwoman, I will buy you a pair; for, with the dislike to long petticoats that comes from your English blood, the pretty buckles are more necessary for you than for Felipa.'

'Oh, dear Carlo, will you really!' said Etta, her face beaming with pleasure. 'How good you are to me!' All at once, however, the smile died away, and, sitting down on a seat near Felipa, the English girl added, with tears in her blue eyes:

'But no, Carlo, I will not accept your buckles: a prisoner has no right to wear pretty things.'

'A prisoner! Oh, Etta!' said Felipa, throwing her arms round Etta's neck, 'why do you say that? Do we not love you dearly? Am I not a sister to you? and Carlo a dear brother? Do I not share all my things with you? And when Catalina is cross to you I make her sorry.'

'And my father has almost forgotten you are not one of his own,' added Carlo, standing behind Etta and taking one of the fair curls in his hand; for he dearly loved this English sister, as he called Etta Allison.

'Yes, yes, it is all true, and Santa Teresa is a lovely home; but I cannot forget I am English, and that I am really a prisoner. I once asked Don Estevan to send me back to England by one of the big ships, and he refused; and yet my mother's last words were that I was not to forget my own land.'

At the thought of her mother Etta's tears came fast; but at this moment the Governor of St. Catherine himself appeared in the garden, and Etta, being afraid to be seen crying, dried her tears and stooped down to play with Felipa's little dog, so as not to show her red eyes. When she looked up again the sunshine had returned to her bonnie-looking face.

The Marquis Don Estevan del Campo was a small thin-looking man, who had long suffered from a liver complaint, and in consequence his whole nature seemed to be changed. From a determined, clever administrator he had become peevish, undecided, and ill-tempered; and the men under him hardly knew how to obey his orders, which were often very contradictory.

To-day he walked towards Carlo, with a troubled expression on his face, and on the way he took occasion to find fault with a slave who was watering the flower-beds. The slave trembled, as he was bidden in a very imperious fashion to be quicker about his work.

Carlo came to meet his father, doffing his hat in the courtly fashion of a young Spanish noble.

'What are you doing here, children?' the Marquis said. 'Is not this your hour of study?'

'You have forgotten, my father, that it is a holiday to-day; and I was coming to ask if Felipa and Etta might not come down to the bay with me and have a row in my canoe.'

The Marquis looked up quickly.

'No, no: there must be no rowing to-day; I have set workmen to repair the bridge, and you had best keep at home.'

'Then we will go to the Orange Grove,' said Felipa, coming up and putting her hand on her father's arm, 'and Etta and I will pick some of the sweetest fruit for your dessert this evening.'

'As you like, Felipa; but do not go far, and take Catalina and some of the slaves with you, for I hear several of the wild dogs have been seen in this neighbourhood. Anyhow, you will not have very long before sunset.'

'I will let the girls go alone, then,' said Carlo, 'and come with you, father.' And so saying the Marquis and his son walked away, whilst the girls with an escort of slaves entered the forest and went down the mountain side. This forest was not, however, such a one as could be found in England. Here the pleasant breeze played among the leaves of a huge fan palm with leaf-stalks ten feet long and fans twelve feet broad; next to it might be found a groo-groo or coco palm, and bananas and plantains; and below these giant trees of the tropics were lovely shrubs, covered with flowers of every hue and shape, round which flitted great orange butterflies larger than any we can see in our colder climate; and Etta with her English blood and active nature was never tired of chasing them, though now and then a little afraid of meeting with snakes.

A great deal of this forest had not been cleared; but close by the path the Governor had had much of the undergrowth cut away, and lower down he had planted a grove of orange-trees, whose green fruit Etta and Felipa loved to pick; and round about was a lovely wild garden where grew sensitive plants and scarlet-flowered balisiers and climbing ferns, over which twined convolvuli of every colour, whilst the bees buzzed about these honeycups, never caring to fly up to the great cotton-trees so far above them, because they found enough beauty and sweetness in the flowers below.

Felipa and Etta did not know the names of even half the beautiful flowers they gathered that evening; but they invented fancy names for many of them, and arranged with good taste a bunch of roses they picked from a bush twenty feet high, glad that a few were within their reach, and longing for Carlo, so that he might pull down some more for them.

Of course there were drawbacks even in this lovely place, for there were the wasps and the spiders to avoid, and centipedes and ants, too; though Etta was never tired of watching the 'parasol ants' who walk in procession, each carrying a bit of green leaf over its head, on which were to be found now and then baby ants, having a ride home in their elegant carriage.

Ah, it was a beautiful and wonderful home these young Spaniards had on this Santa Teresa hill; but at that time even the children in West Indian homes knew there were dangers that might come upon them, and St. Catherine had already been the scene of disasters which Etta could just remember, but which Felipa had seen nothing of as yet, having only been brought from Spain when the Marquis was firmly established as Governor of the island.

After the girls had gathered as big nosegays as they could carry they began to ascend the hill again, for darkness would soon come upon them, there being no twilight in this lovely region, and even with their escort of slaves they were not allowed to be out after sunset.

'Dear Etta,' said Felipa, putting her arm round her friend's neck, 'promise me you will never again call yourself a prisoner. You would not care to leave me and beautiful Santa Teresa to go back to that dreadfully cold, foggy England? Surely you have not found us such cruel Spaniards as your people talk of; and Carlo loves you better than he loves me, I think.'

Etta smiled and kissed her friend, but she answered:

'I love you and Carlo very, very much, Felipa; but my dear mother told me before she died that I was never to part with the letters she gave me, and that some day I must go home and find my relations; for in my country I come from an honourable family, but here I am only an English prisoner.'

Felipa was going to argue the question again, when Carlo came running down to meet them.

'Make haste, Felipa and Etta: my father has suddenly made up his mind to go to the other island this evening; he means to sleep at the Fort St. Jerome, and he says we may accompany him.' The girls, always ready for a little journey, as they seldom left Santa Teresa, clapped their hands in joy and ran up the narrow path to the entrance of the castle, in high glee at the unexpected pleasure.

CHAPTER IV.

THE PIRATES ARE COMING.

St. Catherine is composed of two islands, but so small was the space between them that the Marquis had had a secure bridge built across the tiny strait, and the two islands were always reckoned as one. The children were quite ignorant of the reason of their sudden trip to the greater island, and indeed they only thought of enjoying the fun of going to a new residence; for close to St. Jerome was the Governor's house, near a battery called the Platform, and in sight of the Bay of Aquada Grande. A river ran from the Platform to the sea, and the Marquis had wished to assure himself of the forts being in good order, as the captain of a friendly ship touching lately at St. Catherine had sent a message to him that there were rumours of some attempt on Panama being set on foot by the pirates, and that the Governor of Panama begged Don Estevan del Campo to keep a sharp look-out at St. Catherine, for that island had once been in the hands of the English pirates, and it was known that since the great buccaneer Mansfelt had died and the island had been re-taken by the Spaniards great hopes were entertained by several bands of English pirates that this little island might once more belong to them. It was for this reason that the Spaniards had constructed many forts on the island, especially on the lesser St. Catherine, which was not quite so well provided with natural defences as was the larger island.

It was the receipt of this news that had so greatly disturbed the much-worn-out Marquis, and his nerves were indeed hardly equal to the difficult duties entrusted to him. Pirates had increased terribly of late years. Jamaica, though it had a Governor supposed to be engaged in suppressing them, was yet quite a nest of these bold outlaws, who, taking advantage of the English jealousy of Spain, cared not what outrage they committed on Spanish towns and Spanish islands; though, in truth, other nations fared but little better at their hands.

The Marquis had examined the fortresses in the lesser island, and was much troubled at the few men that were at his disposal for manning them, and for the defence of the island generally; and now, having come to St. Jerome, he determined to send a boat down the river this very evening in order to ask for help and advice from the Governor of Costa Rica, Don John Perez de Guzman, who had five years before so ably retaken the island. But all this amount of thought and anxiety had quite unnerved the poor Marquis, who scolded every one about him, found fault with the garrison, and severely punished some negro slaves for their idleness in the plantations of the Platform; but, as the negroes were always idle, they considered their punishment very unfair.

The next evening Carlo went into the pretty sitting-room of the girls, which looked upon the river and out towards the beautiful bay; but when Felipa, who was very musical, and could sing in French, Spanish, and English, took up her lute, begging him to join in, he shook his head and surprised her by his answer.

'Felipa, don't ask me to sing; I am sure something is the matter with our father. He has got into a passion with Espada, and has put him in irons. It is very unwise, for Espada is a revengeful man, and he has great influence with the other men in the fort, some of whom were once outlaws from Puerto Velo. I wish I were a man and that my father would consult me. His Catholic Majesty ought to give my father a pension and let us all go back to Spain, for I am sure this place does not agree with him.'

Etta listened sadly to Carlo's words; when he was troubled about his father she was very sorry, for the boy was one whom nobody could help loving and admiring.

'Dear Carlo, if the King of Spain knew you he would, I am sure, make you Governor of beautiful St. Catherine, and then the poor negroes would not be oppressed, nor the gentle Indians hunted with dogs as you say they are sometimes. My father used to tell me of the dreadful cruelties used towards those poor people in past days. In England such things would not be allowed.' And, so saying, Etta raised her head proudly, feeling that an Englishman was better than a Spaniard.

Felipa passed her hands over the lute, saying, as the sweet tones were wafted through the room:

'Do not talk of such things, Etta. I am sure our Indians are not unhappy. Andreas loves us clearly; and we make the negroes, not the Indians, work on the marshes. Now I shall sing to drive away your ugly fancies.'

And she sang softly an evening hymn in Spanish, and Carlo and Etta joined in too, so that the sound of the young voices floated over the clear waters of the river, whilst the scent of sweet spice plants was wafted in. Surely Felipa was right: it was not suitable to talk of human miseries when all around nature was so exquisite. Old Catalina soon came in with the evening supper, saying the Marquis had gone out and would sup alone; and very early the girls retired to bed; Carlo told them not to dream of troubles, because he should be next door to them in case they were frightened. He felt that his sister was under his charge now that their father the Marquis was so little able to see after her.

Old Catalina counted her beads and muttered her prayers long after the two girls were sleeping soundly; and as she stooped over Etta's bed and noticed how fair the girl was, she murmured: 'It is a pity this pretty child is a Protestant; but I hope when she is older she will be one with us; for otherwise the Marquis will thrust her out and not let her come home with us to Spain, and my darling Felipa will break her heart, for she loves her English playfellow dearly.'

But the night was not to pass as quietly and peacefully as it had begun. Catalina lay on a mattress in her young mistress's room; but, being a heavy sleeper, she did not hear a hasty knock at the door, and the repeated call of 'Catalina! Felipa! quick! open the door! Why do you all sleep so soundly!'

Etta was the first to awake, and, throwing a coloured shawl about her, she ran to the door and opened it.

'What is up, Carlo?' she said rather sleepily.

'Wake Catalina and Felipa, and make haste and dress yourselves. My father says we must fly from here at once: the pirates are outside the bay. They will land early to-morrow, perhaps opposite this very fort. I beseech you, make all haste you can.' In a few minutes the frightened girl had shaken Catalina, and was trying to explain to Felipa what the danger was which threatened them.

'Oh, Felipa, the pirates are coming! Quick! quick! make haste and dress, for the Marquis says we must go back to Santa Teresa at once.'

Catalina began wringing her hands as poor Felipa turned deadly pale.

'We shall all be killed! May the saints protect us! Ah, my poor lamb! who could have believed those wicked wretches would have dared to show themselves here again, and in your father's lifetime. Alas! alas! make haste, sweetheart, and let us fly!'

Felipa was so frightened that she could hardly dress herself; and poor Etta, who knew more about the dreaded sea-robbers than did Felipa, tried to be brave in order not to increase the Spanish girl's terror. Etta was brave, and in many ways fearless in all ordinary affairs; but the cry 'The pirates are coming!' was one of the most dreaded in the West Indies--a cry which had often taken the spirit out of the heart of a bold sea-captain, who knew the desperate courage and reckless indifference to life exhibited by the men who infested these seas.

When Catalina and the girls were dressed they stepped forth, to find the Marquis and Carlo waiting for them. The former was walking up and down the hall of the house discussing the terrible news with some Spanish officers.

'Your Excellency knows that this fort cannot long resist a fierce assault,' said one of them. 'Were it not better to evacuate the Platform and concentrate our forces on the lesser island batteries? The fortresses there are strongly built, and with our men we could put them in a better state of resistance.'

'They will not land to-night,' said the wretched Marquis, looking the picture of an undecided man. 'If you think, Don Francisco, that flight would be the best plan, give orders to your men. Ah, here are the children. Are the horses ready? We have no time to waste; and yet what say you? Perhaps these wretches will think better of it, and leave Port St. Catherine in peace. Were it not better after all to stay here?'

'Let us stay, father,' put in Carlo. 'If you will let me fight, I am sure I shall be able to defend this place. Do not let this handful of rascals believe we fear them.'

'Give your opinion, Carlo, when you are asked, and not before. Are the horses ready? Now, Felipa, wrap your scarf well round you; we have a long way to go. Yes, I think it is better to go than to stay.'

'We shall be safe at Santa Teresa, father, are you sure?' sobbed Felipa; whilst Etta, looking at Carlo's fearless expression of face, determined to say nothing, for he had once said girls were always afraid.

It was a very anxious and silent cavalcade that made its way back towards the small island that night, and contrasted strangely with that which had come hither but quite lately, laughing and chatting to their hearts' content.

Carlo, however, managed to ride near Etta occasionally when the ground was clearer so as to allow their horses to walk abreast. Felipa kept close to her father, as if near him she would be quite safe from the dreaded foes. Every now and then she looked back into the darkness towards the little village at the foot of the Platform; where, however, all was at present still and quiet.

'Is it really true?' whispered Etta to Carlo, as if she could be heard from this distance; 'have they been seen?'

'I think so. José the one-eyed, who, they say, was once a pirate himself, noticed the ships creeping round towards the bay just before sundown, and he came all the way from San Salvador to give the news, hearing my father was here. However, of course they may think better of attacking us. José believes he recognises one of Mansfelt's old ships; but I think terror gives him double sight, For all that, I wish my father would have stayed and driven off the rascals on their first landing. It looks as if we feared them, and that will make them bolder.'

Not much more was said, and the cavalcade rode through the dark forest, and then emerged on the sea coast, for towards the north of the island the cliffs became lower, and before reaching the bridge there was a good stretch of open country.

'God be praised, and all his saints!' said Catalina, 'I can see the crest of Santa Teresa. We shall now soon be in safety. The rascals cannot climb our mountain; and if they come we can hurl them down into the sea. I wouldn't mind helping to do that with my own hands.'

The Marquis had already sent on a messenger to collect several officers at the Castle of Santa Teresa, which, with its thick walls, its great moat, its impregnable cliff on the sea-side, and its difficult ascent towards the land, was a secure retreat, where the Governor could hold a council of war, and decide what course to take as to repulsing the enemy should he land on the shores of St. Catherine.

'I wish my father would take his own counsel,' thought Carlo for the hundredth time, 'and then he would at least know his own mind. However, now there is real danger, he cannot prevent my helping to defend my sister and my home.' And this feeling made the proud, brave boy forget that fighting does not always mean victory, and caused him not to be altogether sorry that he should have a chance of distinguishing himself, and perhaps--who knew?--the King of Spain would hear of it. Carlo had read of the deeds of brave knights and of their wonderful exploits, and was eager to begin also his own career of fame; but reality is often, alas, very unlike our dreams.

All nature was fully awake when the Governor reached Santa Teresa; and the girls, once more safely surrounded by habitual sights and sounds, forgot their fears, and, after a little rest and refreshment, began, as before, running happily about the gardens within the enclosure. The guards were, however, at once doubled, and the negro slaves posted in the wood.

'Here we shall not see the pirates land,' said Felipa, now almost disappointed, 'nor the punishment our people will give them. I am sure Carlo would have been able to defeat them with the help of a few men. Don't you think so, Etta?'

'I do not know; but, Felipa, let us say our prayers, and then we shall be sure they will not hurt us. Do you know that, in the excitement of the journey, I forgot mine this morning; and I promised my mother never to leave them out.'

'So did I,' exclaimed Felipa, 'but I shall tell Padre Augustine and he will forgive me.' Etta had no such comfort, for she had been early imbued by her parents with a great disbelief in the religion of the Spanish settlers; but from living with Felipa, and being kindly treated by her captors, she had begun to take Felipa's opinions as a matter of course; though now and then the girls had little differences as to the various merits of their Churches. Had Etta not been of a very determined character, most likely she would have forgotten her own faith; but early troubles had made her old in ideas, and passionate love for her dead parents kept all their wishes in her mind. She would sooner have died than have become a Roman Catholic, and at present the Marquis had not taken the trouble to inquire into the matter. Had Felipa not wanted a companion, Etta's fate might have been a sad one; as it was, she enjoyed all the privileges of the Governor's little daughter. But often the English girl would steal away to read over some of her precious letters, or to kiss the few relics she possessed of the gentle mother who had died at St. Catherine. In these days many sad stories might have been told of the sufferings of the wives of the merchants or Governors who had to live away from their country, or who for some reason crossed the seas to come to the West Indies. The prisons of Algeria and the haunts of the West Indian pirates could have revealed, and did reveal, many a sad story of captivity and ill-treatment.

But the day was not to pass without news of the enemy; for in the afternoon Carlo, who had been round the fort with his father, ran in to tell the girls that a messenger had just arrived from the other island.

'The saints protect us! And what does he say? Have they made dried meat of them already?' said Catalina, referring to the meaning of the word buccaneer.

'The enemy has landed below the Platform; they are about a thousand strong, and their leader is no other than the terrible Captain Morgan the Englishman,' said Carlo, much excited.

'A thousand strong!' exclaimed Felipa. 'Then we shall need all our men. But they cannot reach us here. What does our father say?'

Carlo shrugged his shoulders.

'He will give no positive orders, but the rascals are really marching through the woods towards us. I wonder at their rashness, for here we are so well prepared to receive them that they will find it too warm for them. We are to have a council of war this evening. Now, if I were Governor I would starve them out.'

'Will father let you attend the council?' asked Felipa, looking upon her brother as already a knight of renown.

'Nay, but he must. I can use a sword as well as any one. Etta, you shall tie my scarf, and I will wear your colours on my scabbard.'

Etta shook her head sadly.

'The pirates are from my country. Your father will be angry with me, Carlo; and yet my father was none of them. He was a brave and honest merchant.'

'No one shall blame thee, dear Etta,' said the boy, 'or if they do, I will offer single combat.' And Carlo went through his military exercises with great show and laughter, till Catalina and some slaves arrived, and desired the young people to come and help with the defence of the castle by taking away all the valuables and hiding them in the dungeons below or in a well under the flags of the inner courtyard.

Carlo was very angry at this order of his father's: it seemed to presuppose the taking of Santa Teresa.

'As if the pirates would ever enter this stronghold!' he said impatiently. 'If I may be allowed to speak, I will offer to lead out a party from Santa Teresa, and the robbers will see something worth seeing then. I must go and find my father and persuade him.'

In spite of his objection, however, Carlo, as well as every one else, had to work with a will within the walls of Santa Teresa; whilst the Marquis, hardly able to hide his fears, paced restlessly up and down without the castle, often sending negro scouts on all sides to ascertain the real truth; but he got such contradictory answers that he half feared the negroes were too much afraid to venture near enough to the advancing enemy to ascertain how matters stood.

CHAPTER V.

THE SCOUTS.

The council of war presided over by the Marquis took place late that afternoon; and Carlo, bent on proving his capabilities as a soldier, slipped in with the officers and various Spaniards in authority who had been able to leave their several stations to join in the discussion. The Marquis was so much disturbed and troubled that he took no heed of his son, for as the officers entered the private room of the Governor the sound of cannon was distinctly heard in the distance, much to the dismay of many present.

'Those are the guns of St. Jerome,' said one of the officers. 'The enemy must have reached the bridge, and we may expect them here by sunset. Shall we give the order for all the neighbouring guns to fire, sir.'

'That will not be necessary,' answered the Marquis, testily. 'How many guns are there at St. Jerome? Surely enough to drive these robbers back to their boats?'

'We have eight, Señor, at St. Jerome, and those will play freely on them; they will be caught in a trap.'

'Well, then, that will settle them. We know they cannot advance up the river below this hill.'

'Only a canoe could reach us here, and that would hold but a few men,' said Don Francisco.

'The blacks declare that Captain Morgan has only four hundred men with him; if so, there will be no great difficulty.'

'Nay, but the Indian Andreas,' said Carlo, 'has just told me they are more like a thousand strong. I believe Andreas is the only scout who gets near enough to know.'

Carlo had an especial liking for Andreas, who often accompanied him out into the woods to kill the birds. He was a very sharp fellow, and knew every turn and winding in the islands.

'A thousand strong! What nonsense, Carlo! Your opinion was not asked, boy, and silence is your best course,' said the Marquis, angrily.

Carlo blushed, but all the same he knew he was right, and was terribly annoyed at hearing his father ask counsel first of one and then of another, without coming to any decision. He saw several of the officers looking evidently anxious, and when the council of war broke up--having decided nothing but that a scout should be sent to St. Jerome for news, and that there should be another meeting next morning--Carlo went up to an officer and said hastily:

'Why do we not collect a force of men and go out to meet them in the marshes?--for that is surely the way they will advance.'

'The Marquis thinks otherwise, Señorito; and he may be right, for they may find themselves in a sad fix in some of the swamps in the low ground or in the woods, and then they may think it better to return without trying to take a fortress. Besides, we do not know how much powder they may have brought, and we must not waste our own ammunition.'

This was all the consolation Carlo could get, and he went back to his sister's room looking very crestfallen and anxious. So to her eager questioning he answered:

'I wish father would let Don Francisco de Paratta take the command; he himself is quite unable to take it. I could see by Don Francisco's face that he thinks we are doing wrong. We have not even got true information yet as to their number. I have a great mind----' Carlo paused, for a sudden idea now entered his head.

'What are you thinking of?' said Felipa, turning pale. 'Oh, Carlo, do not do anything rash. What should we do without you?'

'Oh, you are safe enough here at Santa Teresa; it would be impossible to take this place by storm with a thousand men, or even double that number, so you need not be afraid, dear Felipa.'

'I know you mean to go and see for yourself,' said Etta. 'I wish I were a boy and I could go with you. To stay still makes one imagine many impossible things.'

'Hush! don't tell any one, especially Catalina,' said Carlo, looking round and seeing they were alone; 'she chatters so much. My plan is this: I will slip outside presently before the gate is shut and run down the hill to the river. There Andreas has a canoe safely hidden in the bushes, and he will paddle me down to the mangrove swamps, and from there we may get near to them and see for ourselves how the pirates are situated.'

'But you will get killed,' sobbed Felipa. 'These wicked English pirates are worse than cannibals; Catalina says that they roast their prisoners alive, and----'

'Nonsense! Dry your tears, little sister, and believe me, Andreas is too clever a fellow to let us get eaten. I shall be back before very late, and I know the only breach that can be climbed.'

Seeing her brother so cheerful, Felipa dried her tears, and hung a little coin round his neck, which, she said, would keep him from harm; and then she and Etta determined to sit up till he should come back, for when he was once gone they would not mind telling Catalina.

In the meantime all was bustle within the fort. The Spaniards had found out now that the Governor had entirely lost his nerve, and this increased the panic of the garrison. The men on watch amused themselves by telling thrilling and horrible stories of the various tortures inflicted by the pirates on their prisoners, and speculated as to the fate of the garrison of St. Jerome, whose fire had ceased when the sun went down. However, every one knew that Santa Teresa was safe enough, and that even if some bold spirits climbed up the steep path on the land side no great number could come on at the same time and so carry the place by assault.

At nightfall, Carlo, unseen by any one, slipped out of the fort; and, plunging into the wood, he was soon joined by the Indian Andreas, who was a fine fellow, a Christian, and, moreover, devotedly fond of the young Spaniard, who had always treated him with kindness. Andreas spoke fluent Spanish, from having been early taught by the Spanish priests, who had brought him up after his father's death.

'That's right, Andreas,' said Carlo, when he saw him. 'Now make haste and show me your path down to the river; the other one is watched by the slaves, and they might set the dogs on us by mistake. I reckon we can reach the swamps in two hours with your canoe, and you tell me that you are sure the enemy is encamped near there.'

'Yes, Señorito, that is the truth; my little boy brought me word. And I believe they are in great distress for want of food; but we shall see. Look, noble Carlo: I have brought my arrows; and woe to any one that tries to touch us!'

After some very difficult walking in the mazes of the forest, through which no one but an Indian could have steered, the two at last reached the river, which ran far below Santa Teresa; and though this stream was only navigable for canoes, it was often used by the Indians and Spaniards when in haste to reach the sea, instead of taking the longer journey by the land road. Andreas had powers of sight which appeared quite extraordinary to Carlo; and when the two were seated in the frail canoe, it was wonderful how the Indian paddled the boat, swiftly and surely, avoiding the rocks as if it were broad daylight, and never mistaking the many bends. Had Carlo been alone he would have grounded the boat half a dozen times, and not have reached his destination before daylight; but as it was, in two hours the boat glided swiftly into the midst of the mangrove swamp through which the river here made its way. All was quiet at first; the canoe did not even disturb the herons and pelicans which slept near by on the interlaced roots of the mangroves.

'If the pirates could have got into this swamp,' whispered Andreas, 'there would be no need of our cannon; but they are too crafty for that. They have doubtless seized a good guide who would not dare to betray them; otherwise they never could have reached Guana's Creek, where, I hear, they have encamped to-night.'

They drew up the canoe near to a great stump standing out in the water, and, mooring it there, Andreas stepped on to a dry piece of ground; then, stooping down, he listened intently, till like a stealthy animal he returned to Carlo.

'I am sure, Señorito, that I can hear the sound of the enemy. I must creep up through the grove and get to the higher ground; then I will return with news, if you will wait. I dare not let you come till I have seen how the land lies. Lie down in the canoe, and I will make haste. But cover yourself up, for the air is bad here, Señor; indeed you must chew this root, and then you will feel no harm.' And so saying, Andreas drew a dark-looking bit of root from his pocket, which was a secret remedy against the swamp malaria, known only to the Indians; then, walking quickly towards the jungle, he disappeared into the darkness.

Carlo had to wait what seemed to him a long time before Andreas came back; and what made it worse for him was the rain, which began to fall heavily. At last, when he was beginning to think his Indian friend had been caught by the pirates, he was startled by hearing a little splash in the water beside him, and in another moment Andreas himself was in the canoe.

'The young Señor did not hear me,' said the Indian, smiling at the start Carlo gave. 'It was to show him how well Andreas can walk in silence that I came so quietly.'

'Did you see them, good Andreas? Tell me quickly, shall I come now, or must we go back?'

'Yes, yes, Señor, I saw them. They are many--a thousand, I fancy, or about that number; but they are in a bad position; they have no food, and no fire to cook it with. I went up quite close and saw the Captain.'

'Captain Morgan! Oh, Andreas, did he look a wicked man? Tell me what he looked like.'

'A tall, fair Englishman, Señor, but not evil-looking; only some of his followers had the bad countenances of wicked men. I could see that they were discontented; and I heard some discussing if they should go back to their ships. Look now, Señor Carlo: if you can persuade the noble Governor to send a hundred well-armed soldiers to-night against these same men, we shall have no more trouble with them. We could drive them into the swamp, and then the swamp would do the rest. Why, they were badly off: some had naked feet like the poor Indians, and some had but ragged clothes, and very few had firearms. They were angry with the Captain at being led into the marsh, and they huddled together when the rain began to fall, cursing their misfortunes.'

'It will go on raining all night, I fancy,' said Carlo. 'I have been nicely sheltered here; but out where they are camped there are but few trees. How could you see all this, good Andreas, for it is still dark?'

'Well enough, Señor, for the rascals had pulled down some of the Indian huts that lie up above, and had made a fire of them. Captain Morgan was trying to make himself comfortable; and I saw a young lad about your size and your age, Señorito, in the Captain's rude tent. I thought he must be his son; but he looked sad and dejected, and not like one of the pirates. Perhaps some young prisoner they have taken. He was busy making up the fire, but I noticed that another fellow watched him pretty closely whenever he strayed a little. Yes, I am sure he was a prisoner.'

This did not interest Carlo so much as Andreas' idea about the hundred men being sent out against the pirates.

'Andreas, you are right. Quick, let us make haste home, and I will do my best to persuade my father to send a body of soldiers here by daybreak. If only he will believe us! Are you tired? Let me row a little.'

But Andreas laughed.

'The Señorito would stick us in the mud at the next bend,' he said, and, taking up his paddle, he sent the frail boat into mid-stream, and as silently as they had come they returned towards Santa Teresa. During the journey Carlo hardly spoke; he was planning the morning's expedition in his own mind; and already he had cleared the whole island of the dreaded horde, and covered the name of Estevan del Campo with glory and honour.

By the time the canoe shot into a tiny cove at the foot of Santa Teresa, Carlo was glad enough to jump up and follow his leader through the forest by an Indian path; and with Andreas' help the wall was scaled, and both entered the enclosure unperceived.

'It is to be hoped the pirates do not know this path,' he said to Andreas; 'but, even if they did, not more than a single file of men could get up here. Do the guides here know of it, Andreas?'

Andreas shook his head.

'Hush, young master, tell no one of it. It is known only to the Indians of my tribe, and there are but few of us now. Good-night, Señorito; I will be ready in the morning if you want another guide.'

Carlo warmly shook the faithful Indian's hand as he bade him good-bye. Before the Spanish occupation Andreas had been a chief's son; but his father had long ago been killed by the white men, and the tribe was broken up. The boy had been educated by the missionaries, but had never altogether forgotten his childhood; and but for his love of Carlo del Campo some said he would ere this have run away from the Governor's estate, where he was forced to tend the gardens and to see his children brought up as something not much better than mere slaves, whilst his gentle wife was expected to help Catalina in household duties, cook the food for the black slaves, and wait on the young ladies.

Carlo was able to creep upstairs unheard by any one; and, seeing a light in his sister's sitting-room, he knocked softly. Catalina opened the door, and the girls, who had fallen asleep on a couch, jumped up eagerly.

'Carlo, there you are! Tell us the news! How glad I am you are safe home!'

'I dreamt you were drawn and quartered by the pirates. My poor lamb,' cried Catalina, 'how we prayed for you, till we fell asleep and forgot to finish the Litany of Danger!'

'Nonsense! there was no danger at all; the pirates are in a bad way, and it is raining hard. But tell me where my father is. We have only to send out men and we are saved. Andreas knows exactly where they are encamped.'

'The noble Marquis was in the guard-room below when I came up,' said Catalina. 'No one has gone to bed this night.'

Carlo hastened away cheerfully. He was some time absent; but when he returned his young face was clouded over with deep disappointment.

'It is of no use; my father will not believe me. He refuses to do anything till there can be another council, and then it may be too late. Why am I not a man!'

'Never mind, dear Carlo,' whispered Etta softly; 'the council may believe you, and then----'

But Carlo shook his head, and, tired out, he went to his own bed and fell asleep from sheer fatigue.

CHAPTER VI.

HATCHING A PLOT.

The next morning the rain stopped, and the sun shone out brightly and powerfully over the beautiful wood which clothed the steep sides of Santa Teresa. The cocoa-nut trees and the various kinds of palms softly waved their beautiful heads in the morning breeze; the sulphur and black butterflies flew hither and thither about the crimson, yellow, and green pods of the cocoa, and on the orchids that hung from the giant stems. All this and much more beauty was unheeded by the people in Santa Teresa, for before the council of war could meet Andreas came running into the courtyard, where Carlo had just come down to hear what news he could, too angry to seek out his father after his disappointment of the previous night.