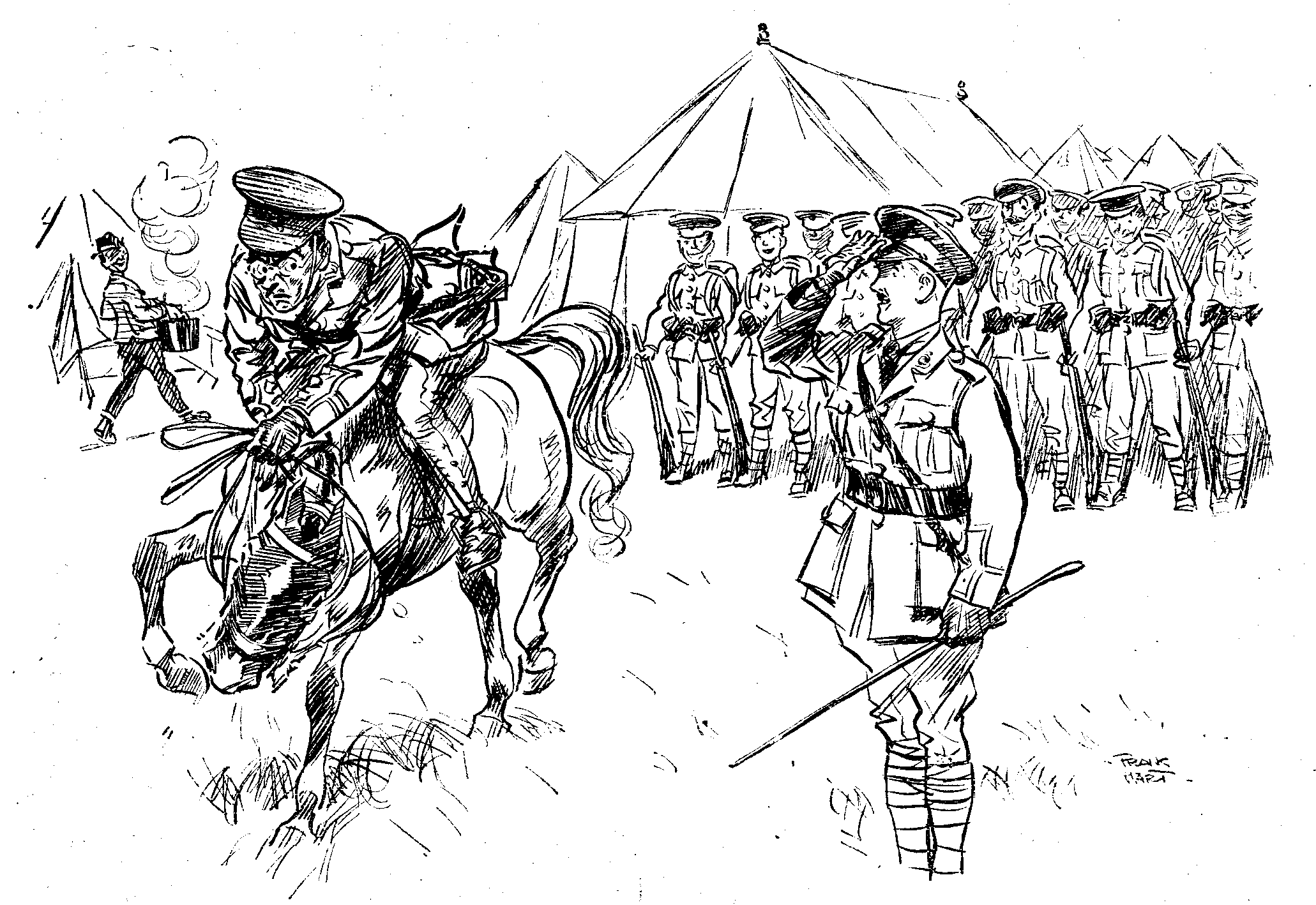

Junior Sub. "The Colonel says will you dismiss the parade, Sir?"

Newly-mounted Captain. "Confound it! Do it yourself, Smith. I'm busy riding."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 150, April 12, 1916, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 150, April 12, 1916 Author: Various Editor: Owen Seaman Release Date: December 5, 2007 [EBook #23746] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Jane Hyland, Jonathan Ingram and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Junior Sub. "The Colonel says will you dismiss the parade, Sir?"

Newly-mounted Captain. "Confound it! Do it yourself, Smith. I'm busy riding."

We are in a position to state that the efficiency of Germany's new submersible Zeppelins has been greatly exaggerated.

Many schemes for coping with our £2,100,000,000 War indebtedness are before the authorities, and at least one dear old lady has written suggesting that they should hold a bazaar.

It is stated that the monkey market at Constantinople, which for hundreds of years has supplied the baboons found in Turkish harems, has closed down. German competition is said to be responsible for the incident.

The Government's indifference to the balloon type of aircraft has received a further illustration. They have rejected Highgate's fat conscript.

German scientists are now making explosives out of heather. Fortunately the secret of making Highlanders out of the same material still remains in our hands.

Deference to one's superiors in rank is all very well up to a point, but we should never go so far as to allow an article by a titled war-correspondent to be headed "The Great Offensive at Verdun."

British songsters, says a writer in The Daily Chronicle, are now being illegally used to regale the wealthy gourmets of the West End in place of the foreign varieties, which can no longer be imported. For ourselves, who are nothing if not British, we are glad of any sign that native musicians are coming by their own.

The practice of interning travellers in Tube and other stations during the progress of Zeppelin raids on the North-East Coast having become extremely popular, it is suggested that some much-needed revenue might be obtained by imposing a small tax—a penny, say, per hour—upon those who thus enjoy the protection and hospitality of our railways.

It is officially announced that Oxford is to have no more Rhodes Kolossals.

Lord Robert Cecil admitted in Parliament last week that the contraband list is to be enlarged, and it is rumoured that, notwithstanding the serious effect the step may have in the United States and elsewhere, the list will be extended to include munitions of war.

A prominent City barber points out to an Evening News correspondent that it would be most unfortunate if the high cost of shaves should result in a discontinuance of the practice of tipping the operator, and adds that only two of the services have increased in price. He means, of course, to draw attention to the fact that sporting chatter, dislocation of the neck, and the removal of superfluous portions of the ears are still provided free of charge.

From a feuilleton (showing what our serial fictionists have to put up with):—

"'To-morrow?' repeated Rosalie, dully. 'I'm afraid I can't to-morrow.'

To-morrow——!

There will be another fine instalment to-morrow."—Daily Mirror.

and certain old associations revived by a draught of this nutritious bean.

["The rate on cocoa is raised from 1-½d. to 6d. per lb." (Loud cheers). The Chancellor's Budget Speech.]

Now, ere the price thereof goes soaring up,

Ere yet the devastating tax comes in,

I wish to wallow in the temperate cup

(Loud cheers) that not inebriates, like gin;

Ho, waiter! bring me—nay, I do not jest—

A cocoa of the best!

Noblest of all non-alcoholic brews,

Rich nectar of the Nonconformist Press,

Tasting of Cadbury and The Daily News,

Of passive martyrs and the law's distress,

And redolent of the old narcotic spice

Of peace-at-any-price—

What memories, how intolerably sweet,

Hover about its fat and unctuous fumes!

Of Little England and a half-baked Fleet,

Of German friendship pure as vernal blooms,

And that dear country's hallowed right to dump

Things on us in the lump;

Of tropic isles whereon this beverage springs,

And niggers sweating out their pagan souls;

Of British workmen, flattered even as kings,

So to secure their suffrage at the polls;

Of liberty for all to go on strike

Just when and where they like.

I would renew these wistful dreams to-night;

For, since upon my precious nibs, when ground,

McKenna's minions, with to-morrow's light,

Will plant a tax of sixpence in the pound,

My sacred memories, cheap enough before,

Will clearly cost me more.

O. S.

I look all right, and I feel all right, but the doctor said the Army was no place for me. Having given me a piece of paper which said so, he looked over my head and called out, "Next, please." It was with this document I was going to produce a delicious thrill—what I might call an "electric" moment. I carefully rehearsed what should happen, though I was not quite sure what attitude to adopt—whether to give the impression that I was a member of a pacific society, look elaborately unconcerned or truculently youthful. This, I decided, had better be left to the psychological moment.

I would take my seat or strap in the crowded tram or train. Observing that I wore neither khaki nor armlet someone would want to know why "a big, strong, healthy-looking fellow like you was not in the Army." I should then try to look pacific or elaborately—see above again. But I should say nothing. My studied silence would annoy everybody. I was quite sure of this, because I really can do that sort of silence very well. The inevitable old woman with a bundle would fix me with her watery eye. "The man in the street," who, of course, would now be in the tram or train, would give a brief history of his three sons and one brother-in-law at the Front. The armleted conductor (we are now in the tram) would give my ticket a very rude punch and my penny a very angry stare. When I was quite sure I had been set down as a slacker, I should produce the doctor's certificate of exemption. In my ultra-polite manner, which is nearly as good as my annoying silence, I should hand it to the man whose three sons and one brother-in-law had evidently been writing for more cigarettes. I would then say, "I know you can talk. It is possible you can read. Would you be good enough to read aloud this certificate?" It would be read and then handed back to me. I would fold it carefully and place it in my inside pocket. Looking very tenderly at the long row of rebuked countenances, I should get up and make for the door. This would be the delicious thrill, the electric moment. The following is what did happen.

I was on the Tube. Conditions were favourable, as Sir Oliver Lodge would say to Mrs. Piper. The old woman with the bundle was not there, but the shop-girl with three regimental brooches was. Everything was going as well as I could have wished. The shop-girl closed her novel and fingered her brooches. A fat old gentleman sniffed vigorously, and someone asked why "a big, strong, healthy, etc., etc." Nobody seemed to be impressed by my splendid silence, but it was there all the same, and somebody was going to be very sorry before he got home. I touched my tie and lit a fresh cigarette. The air was tense. I could almost see my electric moment walking down the compartment to meet me. We were nearing a station. I felt in my pocket.

I had left the certificate at home!

The Army and Navy Exemptions Supply Association, Limited, offer facilities for the evasion of military service.

Ladies supplied to act as Widowed Stepmothers to young Slackers.

Gentlemen not desirous of serving should inspect one of our Bijou Residences. Bath (h. and c.); rent inclusive. District enjoys best water supply and most lenient Exemption Tribunal in the Home Counties.

Persons requiring the Loan of Children may obtain these useful aids to exemption in lots of not less than half-a-dozen (mixed), by the day, week, or month, as desired.

FLAT FOOT IN TWELVE DAYS! A GENUINE DISCOVERY.

Gentlemen wishing to acquire this useful impediment may do so with secrecy and despatch on application (with fee). No permanent disability need be feared, a certain cure being guaranteed within one calendar month after date of signing peace, upon payment of a further fee.

LEARN TO FAINT.

One Correspondence Course will teach you this useful art in two and a half lessons.

Do you want not to go to the Front? Then try our Little White Liver Pills and you will never have another worry. Dose: One, once. Sold everywhere.

HOW TO LOOK OLD. A USEFUL WRINKLE.

No more worry. No matter how youthful your appearance, in Ten Minutes we can make you look

As Grey as Grandpa.

Call and inspect our appliances. They will convince you.

Are you a Man of Genius? And young? And in perfect health? We will see that you are saved for your country. In the words of one of our exempted clients:—

"For why should youth aglow with gifts divine

Be driven forth to glut the foreign swine?"

[Pg 278]

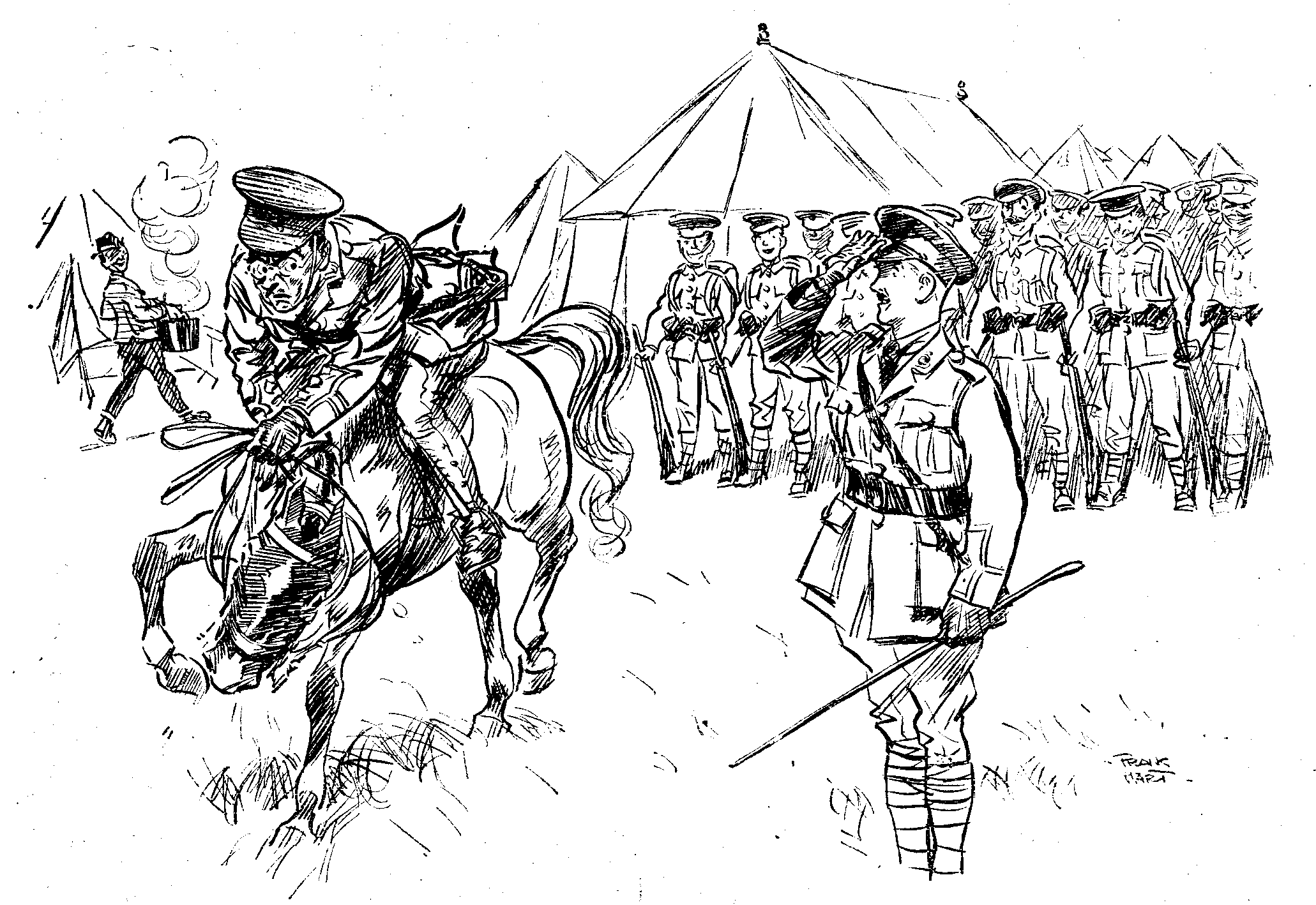

The Old Fox. "YOU DON'T SEEM TO BE GETTING MUCH NEARER THEM."

The Cub. "NO, FATHER. HADN'T WE BETTER GIVE IT OUT THAT THEY'RE SOUR?"][Pg 279]

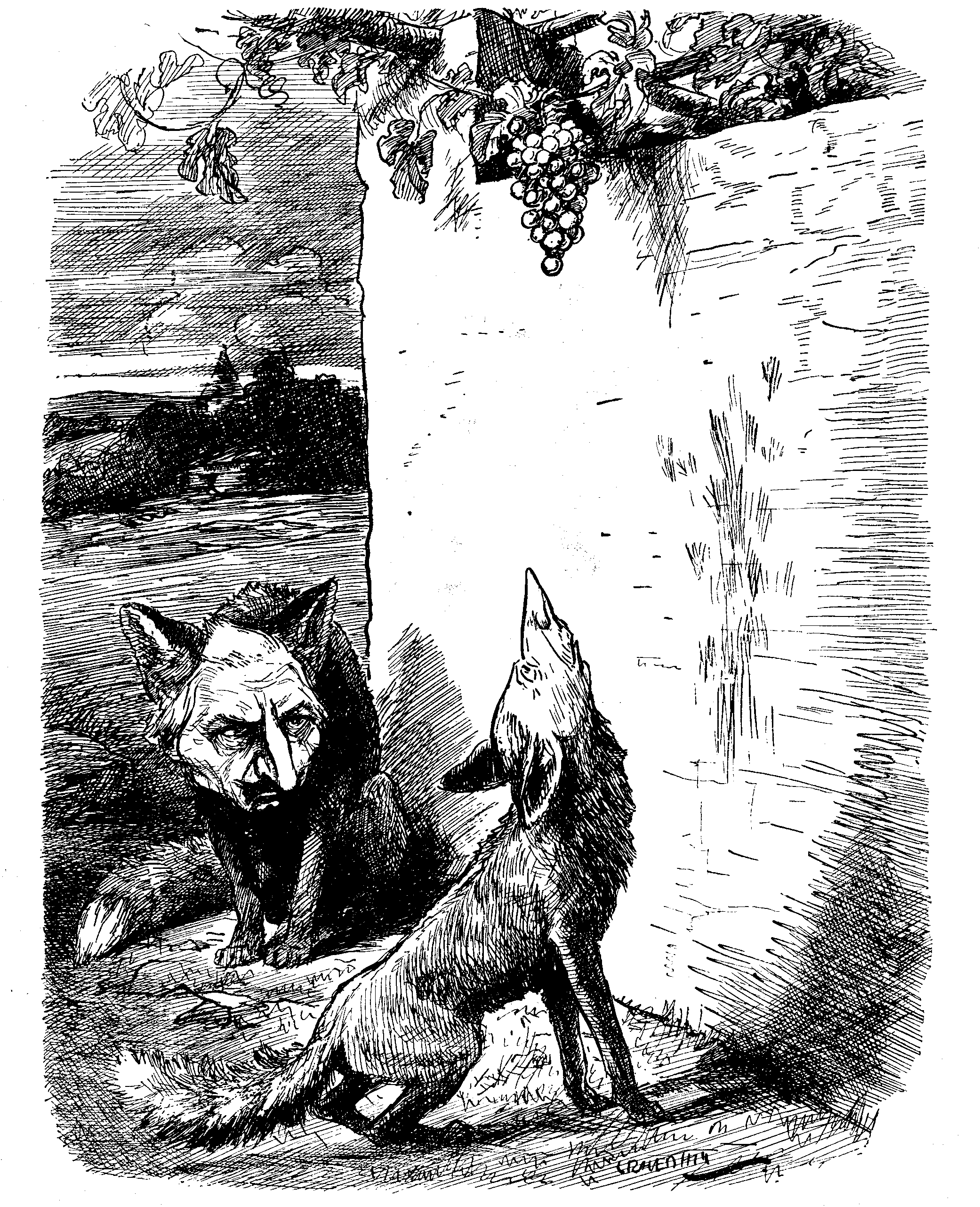

His Fiancée. "He had very bad luck. He was knocked over by a ricochet."

Her Aunt. "Really? I didn't know the Germans had any native troops fighting for them."

XXXVII.

My dear Charles,—This letter is written in England, but the reason for my presence here is not to be dismissed in a breath or mentioned first anyhow. It is to be led up to gradually, the music being stopped and the audience being asked to refrain from shuffling their feet about and coughing when we come to the critical moment.

Reviewing my military career, I do not look upon myself as great; I look upon myself rather as very great. Even at the beginning of it I had a distinct way with me. I would say to fifty men, "Form fours," and sure enough they would form them. I would then rearrange my ideas and say, "Form two-deep," and there, in the twinkling of an eye, was your two deep. This is not common, I think; it was just something in me, some peculiar gift for which I was not responsible. So pleasing was the effect that I would sometimes go on repeating the process for ten minutes or so, and every time it fell out exactly as I said it would, no one ever daring to suggest that the sooner I settled down to a definite policy, whether in fours or twos, the sooner the War would end.

For six months I continued performing this difficult and dangerous work, only once making the mistake of ordering my men to take a left turn and myself taking a right one. Fortunately this happened in a local town of tortuous by-ways, and so it fell out that I and my platoon only met again later in the day; and a most touching meeting it was. Discussing the matter afterwards with my C.O., I inclined to the view that it was an accident which I, for my part, was quite ready to forgive and forget. My C.O. was, however, out of sorts at the moment; in fact he let his tongue run away with him. He even proposed to put me on the Barrack Square for a month, a suggestion which caused my Adjutant (who was interfering as usual) to smile quite unpleasantly. I just looked them straight in the face and said nothing. This, I think, was little short of masterly on my part, since I knew all the time, and knew that they know, that there was in fact no Barrack Square thereabouts to put me on.

After this my men did so extraordinarily well that I became a marked man. I was, in fact, invited to step over to France and to give some practical demonstrations in the art of making war. To pack a few articles into a bag and to parade my men was with me the work of a moment. Before starting it was, however, proper to address a pre-battle speech to them. Silence was enjoined and I spoke, spoke simply and honestly as a great soldier should. "Form fours," said I, and paused dramatically. "Form two-deep," I continued, and my meaning was understood. "Form fours," I concluded ... and we were ready for the worst.

So we moved away for the Field. We did this, I remember, at 5 A.M. Not a moment was to be lost. Our train started at noon and we had three miles to march to the station. Running it pretty close, wasn't it?

Never shall I forget the anxious faces which greeted our arrival at the French port. "Nip up to the trenches," said O.C. megaphone, "and save the situation if you can." Up to the trenches we nipped, covering the distance of sixty miles in less than three weeks. There was no doubt about our willingness and ability to do as we were told; our only difficulty was to[Pg 280] discover in the dark where the situation was. Never shall I forget the tense strain that first night, my men standing to arms through the long hours, with their rifles pointing into the darkness beyond. But not a shot was fired, and when dawn broke all was well. True, the first light revealed the fact that I had got us all with our backs to the enemy, so that if there had been a battle it would have been between ourselves and Mr. Jones's platoon. But you can't have everything; and sense of direction never was my strong point. Never shall I forget our first breakfast in the trenches. It consisted of bacon and eggs, marmalade and tea. How strange and novel an experience it was to be at war!

Mistress. "Well, Jane, what sort of news have you from your young man at the front?"

Jane. "Fatal, Mum."

Mistress. "Dear, dear! I'm very sorry——"

Jane. "Yes, Mum. 'E's broke it off, Mum."

Never shall I forget.... Now I know there was something else, but there are such a lot of things that I am never going to forget about this War that I cannot be expected to remember them all. It was something about someone not shaving, and being in the rear rank while the front rank was being inspected, and in the front rank while the rear rank was being inspected. It was by such brilliance of strategy as this that I was able to do the Bosch out of that little dinner he meant to have in Paris. It was owing to the same, and to my being overheard to remark that I could run the blessed War by myself better than this, that I was given a pen and a piece of blotting-paper and told to carry on. After which, of course, the wretched Bosch never even got as far as Calais.

Truly a remarkable man! But hear the crisis of my career.

This letter is written in England. If you would only read your morning paper properly, you would know why. Looking down the Births Column to see if anybody you know has been born, you would have noticed that We, Henry, are the father of a son, a tall, good-looking fellow, who weighs eight, eighteen or eighty pounds (I could not be sure which) and is a man of few words, obviously the strong silent sort.

On hearing the news we at once reported our achievement to the Staff and asked what we were to do about it. We were informed that, as far as we were concerned, the War stood adjourned for eight days. Later, as we stood in the street trying to think it all out and to remodel our demeanour so as to suggest the responsibility and respectability of a father, we were asked severely why we were standing idle, and told that, unless we were seen forthwith moving off for England at the double, action would be taken. So home, where we were very respectfully saluted by the New Draft. A strange but nice woman who had the parade in hand invited us to come a little closer, but this we refused to do, giving as our reason that we were beginning as we meant to go on and that undue familiarity is bad for discipline. We then addressed a few kind words to the Lady in the Case, who appeared to take it all very much as a matter of course, and with her discussed future dispositions. The Army and the Bar were negatived at once; it was suggested (not by us) that we have already in our small family an example sufficiently fortunate of both. He will be a sailor or a financier. There is something about sailors; it is always a pleasure and a pride to take one of them out to dinner in a public place, especially if he's your own. On the other hand the financier alternative is suggested with a view to the possibility (as things tend) that it may be he who has to take us out to dinner.

Yours ever, Henry.

"The fall of rain during February in Exeter amounted to 5.39 inches. During the same month 80 hours 58 mins. of sunshine were recorded, being an average of 2 hours 42 mins. per day. The chief tradesmen of the district are responsible for this gratifying result." Express and Echo (Exeter).

They seem to be easily satisfied down in the West. If London tradesmen take to purveying the weather we shall want a little less rain and a good deal more sunshine.[Pg 281]

[Professor Robert Wallace, of Edinburgh University, has been defending the cat as a useful member of society and a defence against the ravages of plague, and encourages the breeding, collecting and distributing of types of cats known to be "superior ratters."]

In these days of stress and passion

Feline charms are out of fashion,

And the cult of Pasht is coldly looked upon;

But cat-lovers may take solace

From the words of Robert Wallace,

Who's a scientific Edinboro' don.

Cats as lissome merry minxes,

Or impenetrable Sphinxes—

Leonine, aloof, impassive, topaz-eyed—

Leave our staid professor chilly,

For he clearly thinks it silly

To regard them from the decorative side.

It is not their grace, now serious,

Now malicious, now mysterious,

That appeals to his utilitarian mind;

But, when viewed as extirpators

Of disease-disseminators,

Then he looks with admiration on their kind.

For if cats should ever shun us

Rats with plague would overrun us,

And they're bad enough on economic grounds;

For their annual depredation

On the food-stuffs of the nation

He would estimate at twenty million pounds.

True, O Puss, romance is lacking

In your latest champion's backing,

But at least he isn't talking through his hat;

And if, after all, what matters

Is to have "superior ratters"—

Well, he pays the highest homage to the Cat.

There are heroes and heroes. All heroes are heroes: that is certain. But there are some heroes whose heroism involves more thought (shall I say?), more material, than that of others, who are heroic in a kind of rush, without any premeditation—heroic by instinct. Now it seems to me that the rewards of the more complex heroes ought—but let me illustrate.

I have a friend who is a hero. The other day in France he did one of the most desperate things, and did it apparently as a matter of course; and he is to have the V.C. for it. But is the V.C. enough'? If it's enough for the instinctive heroes, is it enough for him? That is my question. The secret history of his deed is known only to me and to himself, and when I give you an idea of it you will be able to answer.

I will tell you.

Never mind what the deed was. All I will say is that it is comparable to the glorious feat of Lieutenant Warneford, who bombed the Zeppelin from above and sent it crashing down. My friend is an aviator too, and since I am not allowed to describe his great performance in detail let us pretend that it was an exact replica of the Warneford triumph. Armed with his bombs he saw the approaching Zepp and flew high, six or seven thousand feet, to get above it. So far he had merely obeyed the dictates of his brave impulsive nature. He had given no thought to the chances of danger or death, but had flown direct to his duty. So far he was instinctive. But my friend, as well as being unusually brave, is a singularly retiring kind of man. He hates publicity, ostentation. Very shy and very quiet, he moves about the world unperceived, and has all the reluctances of the anchorite. Nothing but his deep feeling about the War could have got him to do anything as prominent as aviation, so that it is not unnatural that, as he mounted higher and higher and came nearer and nearer to the desired point over the Zepp, he should suddenly realise what it would mean for him if he succeeded in bringing it down.

Not that he had too much time for such reflections, for until the envelope intervened between him and the Zepp's marksmen he was being blazed at steadily. Bullets whistled about him. But one thinks swiftly, and in a flash he saw the extremely distasteful consequences to humility, and the dislocation of his secluded way of life if, dropping his bombs accurately, he earned (as he was bound to do) the Victoria Cross. All this he saw, and was properly furious at his bad luck—at the trick that destiny had played on him. He then dropped the bombs, the envelope ignited, and the Zepp, with its crew and its deadly cargo, fell to earth and was blown to atoms.

Now my point is that for such a hero as my friend, whose whole soul is to be outraged by publicity and réclame, and much of whose dearly loved privacy is to be lost for ever, there ought to be a V.C. above and beyond the ordinary V.C.—a super V.C.; for he performed not one deed, but two: he not only destroyed the Zepp but he surrendered his sanctuary.

An Exhibition of Mr. Punch's War Cartoons is now being held at the Leicester Galleries, Leicester Square.

who recently brought down a Zeppelin.

When, Gunner, through the breech you passed

That wingéd messenger of death,

And having made the breech-block fast,

With pounding heart and bated breath

Drew back the rod of tempered steel

That frees the charge and fires the fuse,

I would have given much to feel

My feet in your distinguished shoes.

But when your deadly missile burst

Right on the rover, checked his speed,

And made him rock like one whose thirst

Has frankly caused him to exceed,

You must have felt as feels a god

To whom whole nations bend the knee—

Whichever of the dozen odd

Disputant gunners you may be.

"Who can tell but what Rumania's watchful eye will yet sound the bugle note which at the psychological moment will unite the Balkan thrones?"—Shanghai Mercury.

Rumania seems to have something more than a speaking eye. It even plays tunes.

From a German paper quoted by The Times:—

"The German people fully recognises the nicely retiring manner of the Kaiser during this war."

The Allies are confident that it will receive further recognition before long.

In an article entitled "The Superiority of German Strategy" the Frankfurter Zeitung says:—

"The road before us is, however, long and calls for great achievements. We are not lacking in strength. Let us wait and see."

Mr. Asquith is wondering what this flattery portends.

"I have spoken of the good there is in grooves, in the groovy way of life ... Who can be blind to the fact that life in a groove leads to bigotry and nar-grooves, in the groovy way of life?"

"Claudius Clear" in "The British Weekly."

Not we. We have never been blind to anything of the sort.

"Little Lady, during all these months thoughts entirely with you, treasuring up unbleaching memory of happy hours spent together."—Advertisement in "The Times."

Presumably in the wash-house. Unless some confusion arose, in the mind of the advertiser, between dying and bleaching.[Pg 282]

"It's lovely, but I'm afraid thirty guineas is too much for me."

"It is a good deal, but Madam must remember this a genuine old dress. We Guarantee it to have been in constant wear for at least five years."

"I like it, but it looks dreadfully new."

"If you feel that, Madam, might I suggest that you have it soiled by our special process? We only charge three guineas extra."

"Come along, Mabel. Don't make your mouth water looking in there. Old clothes are not for the likes of Us."[Pg 283]

Since the Budget was produced the match-mendicant is at work more industriously than ever, patting his pockets and looking round expectantly at his fellow-travellers. The surreptitious filling of private boxes in restaurants and club smoke-rooms is rapidly on the increase. Yet if men would only meet the proposed match-tax calmly and thoughtfully they might still remain honest and independent.

There are too many three-match men. Just as the tennis-player sends down the first ball into the net with a fine abandon, and is more careful with the second, so the three-match man strikes his first match without arresting his progress along the street, only slows down a little with the second, and not until the third is in his fingers does he look about for a doorway.

If deep doorways and public telephone boxes were put to better use by the smokers of England much waste of matches would be avoided.

And why do not men buy their matches in a businesslike way? Every man should ask to see them before making a purchase. He should compare the brands, take note of the length and thickness of the sticks, examine the size and quality of the heads, test the durability of the sides of the boxes, compare the numbers in the various boxes, test the breaking strain of the matches and the strength of the flares when struck, and time with a stop-watch the burning of a certain length of match.

Many matches are ruined and wasted by harsh treatment. Strong men are apt to use their strength like giants in striking their matches, with the result that the matches break, or their heads are pulled off, or the side of the box is irreparably injured. Remember that the striking of a match is more of a wrist movement than an arm movement. The man who strikes a match straight from the shoulder deserves to lose it; and the average match is not made to be struck even from the elbow. Many a man, puzzled at his lack of success in striking matches, will find the secret of his failure in too vigorous a use of the forearm. The best plan—one that is adopted by our leading actors and other experts—is to stand firmly with the feet about fourteen inches apart, hold the box between the thumb and fingers of the left hand (be careful to avoid the unsightly method, which some strikers adopt, of holding it in the palm), take the match about one inch and an eighth from the head with the thumb and forefinger of the right hand, bend back the right wrist until the head of the match is two and a half inches from the end of the box, and with a swift but not too sudden wrist-movement away from you rub the head of the match against the side of the box. A little careful practice will soon get one into the way of judging the distance accurately, so that, on the one hand, the box is not missed, and, on the other hand, the head of the match is not too severely strafed.

"Five Zeppelins were seen off the East Coast between nine and ten last night. They appeared to be rather larger machines than those visiting the coast on previous occasions. Measures were taken." Western Evening Herald.

We always use a simple foot-rule for this purpose.

"Forty Thousand American inhabitants at Erzram were massacred by the Turks." Zululand Times.

More trouble for President Wilson.[Pg 284]

Tuesday, April 4th.—When introducing a Budget designed to raise a revenue of seventy or eighty millions, Mr. Gladstone was wont to speak for four or five hours. Mr. McKenna, confronted with the task of raising over five hundred millions, polished off the job in exactly seventy-five minutes. Mr. Gladstone used to consider it necessary to prepare the way for each new impost by an elaborate argument. That was all very well in peace-time. But we are at war, when more than ever time is money, and so Mr. McKenna was content to rely upon the imperative formula of the gentlemen of the road, "Stand and deliver."

For a moment, it is true, he reverted to the old traditions of Budget-night. After observing that there was no parallel in history to the willingness to be taxed which had been displayed by the British people, he declared that it would be a mistake to drive this spirit of public sacrifice too hard. The difficulty which many people had in maintaining a standard of life suitable to their condition was described in such moving terms as to convince some of Mr. McKenna's more ingenuous hearers that the income-tax was not going to be raised after all.

They were quickly disillusionised. The rich will have to contribute (with super-tax) close on half their incomes; the comparatively well-to-do a fourth; even the class to whose special hardships the Chancellor had just made such pathetic allusion will have to pay an additional sixpence in the pound. If in the circumstances some of them feel inclined to echo Sir Peter Teazle's remark to Joseph, "Oh, damn your sentiment," I think they may be excused.

That, however, was Mr. McKenna's only lapse. The rest of his speech was ruthlessly and refreshingly practical. The millions were ticked off as rapidly, and almost as mechanically, as the two-pences in the other taxis. Five millions from cinemas, horse-races, and other amusements, three from railway tickets, seven from sugar, two from mineral waters, another two from coffee and cocoa (even the great Liberal drink cannot escape under a Cocoalition), and nearly a million from motor vehicles.

Forty-five years ago Mr. Lowe proposed to extract "ex luce lucellum" by putting a tax of a half-penny a box upon matches, and was duly punished for his pun. When the matchmakers of the East-end (quite as dangerous in their way as those of the West-end) marched in procession to the House of Commons, the Government bowed before the storm. Undeterred by their fate, Mr. McKenna now proposes to put a tax of 4d. on every thousand matches, and expects to get two millions out of it. But it must not be forgotten that there are substitutes for matches; and I should not be surprised if Mr. McKenna himself has to put up with a spill.

Not much criticism was however to be heard to-night, though Mr. William O'Brien gave it as his opinion that Ireland ought to be omitted from the Budget altogether. With him was Mr. Timothy Healy, whose principal complaint was that the tax on railway tickets would put a premium on foreign travel. People would go to Paris instead of Dublin, and Switzerland instead of Killarney. Here somebody tactlessly reminded him that a war was going on in Europe, and shunted him on to a less picturesque line of argument.

Wednesday, April 5th.—Congratulations are due to the Earl of Meath on a long-delayed triumph. For fifteen years he has been trying to convince the British Government that there is an institution called Empire Day. Throughout the Dominions, May 24th, Queen Victoria's birthday, is kept as a public holiday, and even in the Old Country, despite official discouragement, the Union Jack is hoisted on thousands of schools and saluted by millions of children. To the suggestion that the public offices should be similarly adorned the Government, under the erroneous belief that patriotism and militarism were identical, has hitherto maintained an unflagging opposition. But to-day Lord Crewe admitted that the proposal was reasonable.

Sir George Reid has made the surprising discovery that there are a number of excellent speakers in the House of Commons who do not speak, but concentrate themselves upon the despatch of business. Perhaps this was his genial way of indicating the more obvious fact that there are others of a precisely opposite kind. He himself is an excellent speaker who speaks; but concentration is perhaps hardly his strongest point, and he wandered to-day over so many fields that the Chairman had more than once, with obvious regret, to recall him to the strict path of the Finance Bill, which ultimately passed its first reading, amid cheers that it would have done the Kaiser good to hear.

Mr. Pemberton-Billing, having been prevented by the Budget from making his usual Tuesday speech, delivered it to-day, and had a success which was, I trust, as gratifying to him as it was surprising to the House.[Pg 286]

Wife. "Do you think the Zeppelins will come here?"

Husband. "Very possibly, I should say."

Wife. "Then I shan't start the Spring cleaning."

At the close of his now customary catalogue of the defects he has discovered in our air-service, he offered personally to organize raids upon the enemy's aircraft headquarters, and ventured to believe that he could bag as many Zeppelins in a day as the Government could bring down in a year by their present methods of misplaced guns and misplaced confidence.

Mr. Tennant did not think our confidence was misplaced. But he would certainly accept Mr. Billing's offer, and would confer with him as to how to make the best use of his services. It seems probable, therefore, that for some little time the House will have to do without its weekly lecture from the Member for East Herts. Under the shadow of this impending bereavement Mr. Tennant is bearing up as well as can be expected.

Thursday, April 6th.—Everyone was delighted to see the Prime Minister back in his place to-day after his three weeks' absence. Members on both sides cheered loudly and long as he entered the House. They also displayed a gratifying curiosity regarding his views on various subjects, and to that end had put down no fewer than thirty-two questions for his consideration. The amount of information they received was hardly commensurate with the industry displayed in framing them. Mr. Asquith made, however, one announcement of great moment. The Government are now considering how many recruits they have got, and how many they still want. They will then announce their decision as to the method to be adopted for obtaining more, and will give a day for its discussion. This is to be done before Easter. Asked how long the House would adjourn for, Mr. Asquith replied, with obvious sincerity, "I hope for some time."

The great crisis of which we have heard so much in the newspapers is thus postponed. But a little crisis, not altogether unconnected with the other, had still to be resolved. The Government had a motion down to stop the payment of double salaries to Members on service, and to this Sir Frederick Banbury had tabled an amendment providing that Parliamentary salaries should be dropped altogether. Mr. Duke and other Unionists subsequently put down another amendment, designed to stop the discussion of the larger question on the ground that it was a breach of the party truce.

The Speaker however decided that Sir Frederick was entitled to first cut at the Banbury cake. He made, as I thought, a very fair and not unduly partisan use of his opportunity, arguing that the conditions of Parliamentary life had changed since the War, and that as Members were no longer called upon to work hard they should save the country a quarter-of-a-million by dropping their salaries.

No one, I think, was prepared for the tremendous blast of invective which came from Mr. Duke. In language which seemed to cause some trepidation even to the Ministers he was supporting he denounced his right hon. friend for introducing "this stale and stinking bone of contention," and plainly hinted that it was part of a plot to get rid of the Prime Minister. If that eminent temperance advocate, Sir Thomas Whittaker, had not poured water into Mr. Duke's wine, and emptied the House in the process, there might have been a painful scene.[Pg 287]

"Disraeli."

Our early-Victorian oligarchs disdained their Disraeli as a mountebank because he wore the wrong waistcoats and had genius instead of common-sense. If he had grown to be the least like Mr. Louis Napoleon Parker's Disraeli, if he had taken to standing over Governors of the Bank of England and forcing them to sign documents under threat of smashing up their silly old bank, if he had been such a judge of men as to have made that prize ass, Lord Deeford, his secretary, or conducted his menage at Downing Street in the highly diverting manner exhibited in Mr. Parker's second Act, one trembles to think what they would have called him—and done to him. And whether, if the Bank had ever had such a Governor as Sir Michael Probert, England would have ever been in a position to buy a single share in the Suez Canal or any other venture, is a question for the curious to consider.

No wonder the Americans enjoyed Disraeli! Reinhardt should pirate it for Berlin, as it would lend some colour to the imaginative Dr. Hellferich's airy dissertations on English finance. Can it be that our author is a hyphenated patriot in disguise and that this is merely a ramification of the so thorough German Press Bureau's activities? Perish the thought!

At the opening of the play, with Mr. Disraeli and his wife as guests at Glastonbury Towers, all went well. The almost uncanny lifelikeness of Mr. Dennis Eadie's make-up, the steady flow of the great man's good things, which had been discerningly culled and quite skilfully put together, his swift parries and kindly thrusts, his charming tenderness towards that best of wives, the shining heroine of the crushed thumb, all this was admirable, was eminently believable—that is if you except the exaggerated futility and insolence of the aristocratic background. It was when the adventuress got going; when casements began to be mysteriously unlocked by fair hands, and pretty ears applied to key-holes at vital moments of quite improbable disclosures to more than improbable young men; when important despatches and secret codes began to be left about in conspicuous places, in rooms conveniently vacated for notoriously suspect plotters; when the Prime Minister began to bounce and prance and to lay booby traps, into which not his enemies but his incomparable secretary promptly blundered—it was then that things went crooked.

It is perhaps not to be regretted. Nothing is more diverting to the perceptive playgoer than these little dramatic-simplicities; as when, the great Suez deal having been completed—a fact that it was enormously important to conceal from the Press and the country (and the adventuress)—a telegram with full details in the plainest of plain English is despatched from the local post-office to the great financier who had made the deal possible. The charming naïveté of the family gathering at the Foreign Office (it might have been Mme. Tussaud's) and the adorable ingenuousness of the idea of bringing down a great international financier by holding up his cargo of bullion in a foreign port, should lead no one to complain that high politics are dull.

I wouldn't have missed Mr. Dennis Eadie's Disraeli for a good deal. Where it was at all possible—which it was in general; Mr. Parker only sprinkled his extravagances—the ease and plausibility of it were quite admirable. This adroit player gave us the tact, the wit, the gallantry, the generosity, the romantic exuberance. It was a fine performance, and it will be finer as its firm outline is filled in. The play, for all its vagaries, may even serve to remind a careless age of its too lightly forgotten spacious dead. Miss Mary Jerrold's Lady Beaconsfield was, I suppose, more in the nature of an imaginary portrait. It was beautiful and convincing. As a stage adventuress Mme. Dorziat was most attractive, if only she had been credible. She had no business to be in any of the situations in which she found herself, and must have needed all her skill to conceal the fact from herself. Miss Mary Glynne as The Lady Clarissa, the portentous Duchess of Glastonbury's pretty daughter and the doomed bride of the egregious Deeford, was quite charming to watch and hear. Mr. Cyril Raymond should, I am sure, mitigate the asinine priggishness of the young viscount's bearing in the First Act. His conversion from this to the merely crass stupidity of the second was too much for us to bear. Mr. Vincent Sternroyd as Mr. Hugh Meyers looked quite as if he might have been able to put his hand on two million; Mr. Harben as Sir Michael Probert just as if he would sign any document which was put before him under threat or suggestion. Mr. Campbell Gullan, as the adventuress's husband, made himself the kind of clerk that no one would have trusted for a moment with even the petty cash. These things I know are necessary and I acquit him of any artistic impropriety. But you will go to see this piece chiefly for the sake of Mr. Eadie's tour de force, for the thrill of the rather pleasant sensation (mingled with a slightly horrified suspicion of sacrilege) of seeing a queer resurrection, and for the fragrance of a touching little idyll of married friendship—one of the most enduring of Disraeliana. T.

"Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands?"

Merchant of Venice, Act iii. Sc. I

Benjamin Disraeli ... Mr. Dennis Eadie. Mrs. Noel Travers ... Mlle. Gabrielle Dorziat

A Special Matinée, at which the Queen will be present, is to be given at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, at 2.30, on Friday, April 14th, in aid of of the Y. W. C. A.'s fund for providing Hostels, Canteens and Rest Rooms for women engaged in munition and other war-work. Among the artists who have promised to appear are Madame Sarah Bernhardt, Miss Gladys Cooper, Mr. Joseph Coyne, Mr. Gerald du Maurier, Mr. Dennis Eadie, Miss Lily Elsie, Madame Genée, Mr. Robert Hale, Mr. Charles Hawtrey, Madame Kirkby Lunn, Mr. George Robey and Miss Irene Vanbrugh. The Matinée has been organised by Miss Olga Nethersole, and the stage will be under the direction of Mr. Dion Boucicault.

Applications for seats should be addressed to the Manager, Box Office, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Cheques to be made payable to Lady Sydenham.

Officer (to Sentry on fire-step in the trenches). "Anything to report, Sentry?"

Sentry (who has been gazing steadily at wire entanglements), "All quiet, Sir, except them posts out there. If I watch 'em long enough they start forming fours.".

We learn that at a recent matinée performance of a play by Mr. W. B. Yeats, "instead of scenery a Chorus of singers was introduced, who described the scene as well as commenting upon the action." In these times that call for frugality other managements would do well to copy. One might mount an entire West-End Society comedy, and bring as it were the scent of Hay Hill across the footlights, at no greater expense than the cost of a back-curtain and a Chorus. The latter might go something as follows:—

This is the morning-room of the heroine's house in Half Moon Street;

Noble and large is the room, with three windows, two doors and a fireplace

(Goodness knows how many more in the wall through which we are looking).

Nobly and well is it furnished, with chairs and with tables and couches,

Couches beyond computation, and all of them soon to be sat on;

So may you see that the play will be dialogue rather than action.

Pleasant and fresh in the footlights the chintzes with which they are covered,

Giving a summer effect, helped out by the plants in the fireplace.

Curtains at each of the windows are flooded with limelight of amber,

Whence you may learn that the time is a fine afternoon in the season.

Centre of back a piano, whose makers are told on the programme,

Promises snatches of song, or it may be a heartbroken solo.

Carpets and rugs and the like you can fill in without any prompting;

Pictures and china and books, and photographs circled in silver.

Yes, you may take it from us that the piece has been mounted regardless.

[Enter the leading lady. She just pushes the back-curtains apart and emerges on to the stage, dressed in any old thing (what a saving!). The Chorus continues ecstatically.]

See where the heroine comes, flinging open the door from the staircase

(Marked you the head of the stairs and the artist-proof on the landing?

That's what I call realistic). She's threaded her way through the couches,

Sinks upon one for an instant, then rises and walks to the window,

Showing the back of her gown to be fully as chic as the front part.

So to the door (in the curtain) and slams it with signs of emotion,

Slams it so hard and so fierce that the walls of the room are a-quiver;

Even the opposite side of the roadway, as seen through the windows,

Shares in the general movement, as though it were struck by an earthquake.

And so on. You catch the idea? Bare boards, a passion and a Chorus; and the management would save enough to make the amusement-tax a matter of indifference.

V.—Swiss Cottage.

I heard a Jodeller

In a Swiss cottage

Eating a crust

And a bowlful of pottage.

He jodelled and jodelled

'Twixt every bite;

He jodelled until

Not a crumb was in sight.

He jodelled and jodelled

'Twixt every sup;

He jodelled until

He had drunk it all up.

He put down his bowl

And he came to the door,

And jodelled and jodelled

And jodelled for more!

"The exportation of the following goods is prohibited to all destinations:—

Acetic acid, cinematograph films, ferro-molybdenum, ferro-silicon, ferro-tungsten, gramophone and other sound records, photographic sensitive firms, &c., &c." Liverpool Daily Post.

"Two photographers from Devonport, who had been already deferred ten groups, asked that their claims should be heard in camera." Western Morning News.

No doubt they belonged to one of the sensitive firms above mentioned.[Pg 289]

Every Englishman who has taken even a very humble part in the consideration and discussion of public affairs is or ought to be aware that the most gratuitous error he can commit is to take a side in American politics and to criticise American public men from the British point of view. From that error I propose to abstain most rigorously. It is the right of Americans to criticise their own Government and the public acts of their statesmen, and on that right I shall not infringe. It cannot, however, be improper for an Englishman to set out before his fellow-countrymen the utterances of a great American on matters which vitally affect not only America but the whole civilised world. Mr. Roosevelt—for Mr. Roosevelt is the great American of whom I speak—has done more than give utterance to his opinions; he has deliberately collected them into a book, Fear God and Take Your Own Part (Hodder and Stoughton), and has thus invited us to read and consider his views. I accept his invitation and trust I shall not abuse the privilege.

It is a refreshment to go about with Mr. Roosevelt through the pages of this book. Here are no doubts and no hesitations, no timidity and no blurred outlines. Everything is clear cut and well defined. Where Mr. Roosevelt blames he blames with a vigour which is overwhelming; where he approves he approves with a resonant zeal and enjoyment. He has no drop of English blood in his veins—he himself has said it more than once—yet he is strong in his praise of our conduct and even stronger in his denunciation of the faithlessness and inhumanity of Germany. The contemplation of German atrocities and of what he considers to be America's weak compliance with them fills him with a rage which is fortunately articulate. His indictment of Germany is as vigorous as the most ardent pro-Ally can desire. It would be agreeable to watch the Kaiser's face if he should happen to take up this book in an idle moment between one front and another.

Mr. Roosevelt's position can be best defined in his own words. "We Americans," he says, "must pay to the great truths set forth by Lincoln a loyalty of the heart and not of the lips only. In this crisis I hold that we have signally failed in our duty to Belgium and Armenia, and in our duty to ourselves. In this crisis I hold that the Allies are standing for the principles to which Abraham Lincoln said this country was dedicated; and the rulers of Germany have, in practical fashion, shown this to be the case by conducting a campaign against Americans on the ocean, which has resulted in the wholesale murder of American men, women and children, and by conducting within our own borders a campaign of the bomb and the torch against American industries. They have carried on war against our people; for wholesale and repeated killing is war, even though the killing takes the shape of assassination of non-combatants, instead of battle against armed men."

Here again is a passage which is not lacking in emphasis: "Of course, incidentally, we have earned contempt and derision by our conduct in connection with the hundreds of Americans thus killed in time of peace without action on our part. The United States Senator or Governor of a State or other public representative who takes the position that our citizens should not, in accordance with their lawful rights, travel on such ships, and that we need not take action about their deaths, occupies a position precisely and exactly as base and as cowardly (and I use those words with scientific precision) as if his wife's face were slapped on the public streets and the only action he took was to tell her to stay in the house."

This, too, on the hyphenated is good: "As regards the German-Americans who assail me in this contest because they are really mere transported Germans, hostile to this country and to human rights, I feel, not sorrow, but stern disapproval. I am not interested in their attitude toward me, but I am greatly interested in their attitude toward this nation. I am standing for the larger Americanism, for true Americanism; and as regards my attitude in this matter I do not ask as a favour, but challenge as a right, the support of all good American citizens, no matter where born and no matter of what creed or national origin." That puts the matter in a nutshell.

I might continue with pithy extracts until the columns of Punch were filled to overflowing, and even then I should not have exhausted the interest of this virile and timely book. The reading of it can only serve to confirm an Englishman's faith in his country's cause. Thank you, Mr. Roosevelt, for your admirable tonic.

He entered the train at St. James' Park—a dark-eyed young Belgian wearing the new khaki uniform of King Albert's heroic Army. I had watched him hobbling along the platform, and my own boots and puttees being coated with mud after a day's trench-digging in Surrey I drew them in as he took the corner seat opposite mine, stretching out rather stiffly before him the leg which had no doubt stopped a Bosch's bullet. Here was the opportunity for an interesting exchange of views. I was mentally rehearsing a few bright opening sentences in French when the train again stopped. Half twisting in his seat he peered uncertainly out of window.

"Victoria," I informed him; but he obviously didn't understand. I raised my voice.

"Victoria Station," I told him again. "Er—er, Victoire."

His stick fell clattering to the floor, his mouth broadened into a fraternal smile and, seizing both my hands, he worked them like pump-handles.

"Ah, bon, bon! À la victoire! Vivent les Alliés!"

"Brazil.—The British Consul at Porto Alegre states that there appears to be a prospect of the work of repaying the town being carried out in the near future. The contract provides for the repaving of an area of 500,000 square miles at a total cost of £223,200." Morning Paper.

If these figures are correct Porto Alegre must have the record for cheap paving, always excepting an even warmer place where good intentions are the material employed.[Pg 290]

Sergeant-Major (lecturing the young officers of a new battalion of an old regiment). "You 'aven't got to make traditions; you've only got to keep 'em. You was the Blankshire Regiment in 1810. You are the Blankshire Regiment in 1916. Never more clearly 'as 'istory repeated itself.".

There are some men whose patronymics are swallowed up in their nicknames, and my friend "Conky" is one of these. He has quite a decorative surname of his own, but it never counted. For the rest he is the possessor of a big booming bass voice, which he uses with more gusto than art. He is, apart from a certain pride in his musical accomplishments, a very good fellow; and so is Mrs. "Conky"—an amiable and agreeable woman, whose only fault is an excessive anxiety for the comfort of her guests, leading her at times to forget, in the words of the Chinese proverb, that "inattention is often the highest form of civility."

They are a devoted couple, and the only cloud on their happiness was caused by Conky's expectations from a mysterious and eccentric uncle. For a long time I was inclined to disbelieve in his existence, as he never "materialised." But I was converted from my scepticism, some three years ago, when, on meeting Conky, I was informed that Uncle Joseph had invited himself on a short visit. My friend betrayed a certain agitation. "You know," he said, "it is twenty years since I saw him last, when he came to look me up at school, and rather frightened me."

"Frightened you! But how?"

"Well, you see, he's got a way of thinking aloud, and it's rather embarrassing. I don't mind being called 'Conky,' as you know, but it was rather trying to hear him say, 'I hope his nose has stopped growing.' However, I couldn't very well put him off now. I'm his only nephew; he's an old man, and said to be very rich." Conky sighed, but added more hopefully, "Anyhow, I'm sure Marjorie will rise to the occasion." Personally I was by no means so sure. I felt that Marjorie might overdo it: also that Conky, who loved the sound of his voice, might be tempted to soothe the old man with intempestive gusts of song.

Unhappily my misgivings were realised. A few weeks later, on my way home from the club, I called in late one afternoon on the Conkys. They greeted me cordially as usual, but I could see something was amiss, and soon it all came out. The visit had been a fiasco. Uncle Joseph had been very friendly and even courteous, but at intervals he thought aloud with devastating frankness. Marjorie had exhausted herself in the labours of hospitality, but all in vain. Conky had sung, but the voice of the charmer had failed. And just as Uncle Joseph was going he observed in a final burst of candour, "Goo-ood people, very goo-ood people; but she's a second-rate Martha, and he sings like a bank-holiday trombone-player on Blackpool sands."

From that day till a week ago I never heard Conky or his wife allude to Uncle Joseph. The memory was too painful. And yet it is impossible to deny that the experience was salutary. Marjorie is certainly less overwhelming in her hospitality, and Conky less prodigal of song. And when Conky told me last week that Uncle Joseph had died and left him £10,000, I felt that the old man had atoned handsomely for his unconscious indulgence in a habit for which, after all, a good deal was to be said.[Pg 291]

The latest of our novelists to succumb to the temptations of the school story is Mr. E. F. Benson; and I am pleased to add that in David Blaize (Hodder and Stoughton) he seems to have scored a notable success. It is the record of a not specially distinguished, but entirely charming, lad during his career at his private and public schools. Incidentally, as such records must, it becomes the history of certain other boys, two especially, and of David's relations with them. It is this that is the real motive of the book. The friendship between Maddox and David, its dangers and its rewards, seems to me to have been handled with the rarest delicacy and judgment. The hazards of the theme are obvious. There have been books in plenty before now that, essaying to navigate the uncharted seas of schoolboy friendship, have foundered beneath the waves of sloppiness that are so ready to engulph them. The more credit then to Mr. Benson for bringing his barque triumphantly to harbour. To drop metaphor, the captious or the forgetful may call the whole sentimental—as if one could write about boys and leave out what is the greatest common factor of the race. But the sentiment is never mawkish. There is indeed an atmosphere of clean, fresh-smelling youth about the book that is vastly refreshing. Friendship and games make up the matter of it; there is nothing that I could repeat by way of plot; but if you care for a close and sympathetic study of boyhood at its happiest here is the book for your money. Finally I may mention that, though in sympathetic studies of boyhood the pedagogue receives as a rule scant courtesy, Mr. Benson's masters are (with one unimportant exception) such delightful persons that I can only hope that they are actual and not imaginary portraits.

You will get quite a serviceable impression of what the highlands and highlanders of Serbia and Montenegro were like in war, behind the lines when the lines still held, from The Luck of Thirteen (Smith, Elder), by Jan Gordon (colourist) and Cora his wife, if you are not blinded by the perpetual flashes of brightness—such flashes as "somebody had gnawed a piece from one of the wheels" as an explanation of jolting; "the twistiest stream, which seemed as though it had been designed by a lump of mercury on a wobbling plate;" the trees in the mist "seemed to stand about with their hands in their pockets, like vegetable Charlie——" But no! I am hanged if I will write the accurséd name. This plucky pair of souls had put in some stiff months of typhus-fighting with a medical mission in the early months of the war, and these are impressions of the holiday which they took thereafter among those fateful hills, with a little carrying of despatches, retrieving of stores and a good deal of parasite-hunting thrown in, until they were finally caught up in the tragic Serbian retreat; still remaining, of course, incurably "bright." I think I detect a certain amount of the too-British attitude that contemns what is strange and is more than a little scornful of poverty, official and private. And I suppose the artist's wife will scoff if I tell her that I was shocked that she should have taken some shots at the Austrians with a Montenegrin machine gun, as if war was just a cock-shy for tourists. But I was. If Mr. Jan Gordon found a good deal more colour in his subjects than we other fellows would have been able to see, that's what an artist's for.

SALVE.

Returning Soldier. "'Ullo, Mother!"

His Wife (with stoic self-control). "'Ullo, Fred. Better wipe yer boots before you come in—after them muddy trenches."

In Jitny and the Boys (Smith, Elder) there are those elements of patriotism, humour and pathos which I find so desirable in War-time books. Jitny was neither man nor woman, but a motor-car, and without disparaging those who drove her and rode in her I am bound to say that she was as much alive as any one of them. She certainly talked—or was responsible for—a lot of motor-shop, and I took it all in with the greatest ease and comfort. Jitny indeed is a great car, but she is not exactly the heroine of a novel. She is just the sit-point from which a very human family surveys the world at a time when that world is undergoing a vast upheaval. In the father of this family Mr. Bennet Copplestone has scored an unqualified success, but the boys are perhaps a little old for their years. This, however, is no great matter, for the essential fact is that the book is full of the thoughts which make us proud to-day and help us to face to-morrow. Yes, Jitny has my blessing.

Little Willie goes for more Loot.

"In the Woevre the Germans attempted on three occasions to capture from us an earthquake."—Glasgow Evening News.

A schoolgirl's translation:—"La marquise recommanda son âme à Dieu." "The Marquis wished his donkey good-bye."

"A number of officers in the province of Yunnan, China, hatched a plot to behead the Governor-General at Urumtsi, and proclaim the independence of the province of Sinkiang. The Governor, discovering the plot, invited ten of the conspirators to an official dinner, at which he beheaded them in turn."—Reuter.

"Another glass of wine, Mr. Wung Ti?" "No? Very well, then, if you would kindly stand up a moment and place your neck on the back of your chair—— Thank you. After the savoury I shall have the pleasure of calling upon the next on my list, Mr. Ah Sin," and so on. Quite a jolly dinner-party.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

150, April 12, 1916, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 23746-h.htm or 23746-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/3/7/4/23746/

Produced by Jane Hyland, Jonathan Ingram and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

[email protected]. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a