This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Under the Rose

Author: Frederic Stewart Isham

Release Date: December 2, 2007 [eBook #23675]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK UNDER THE ROSE***

"A song, sweet Jacqueline!"

"No, no—"

"Jacqueline!—Jacqueline!—"

"No more, I say—"

A jingle of tinkling bells mingled with the squeak of a viola; the guffaws of a rompish company blended with the tuneless chanting of discordant minstrels, and the gray parrot in its golden cage, suspended from one of the oaken beams of the ceiling, shook its feathers for the twentieth time and screamed vindictively at the roguish band.

Jingle, jingle, went the merry bells; squeak, squeak, the tightened strings beneath the persistent scraping of the rosined bow. On his throne in Fools' hall, Triboulet, the king's hunchback, leaned complacently back, his eyes bent upon a tapestry but newly hung in that room, the meeting place of jesters, buffoons and versifiers.

"We appeal to Triboulet—"

"Triboulet!"

A girl's silvery laugh rang out.

"Triboulet!"

Again the derisive musical tones.

Upon his chair of state, the dwarf did not answer; professed not to hear. By the uncertain glimmer of torches and the flickering glow of the fire he was engaged in tracing a resemblance to himself in the central figure of the composition wrought in threads of silk—Momus, fool by patent to Jove, thrust from Olympus and greeting the earth-born with a great grin.

"An excellent likeness!" muttered Triboulet. "A very pretty likeness!" he continued, swelling with pride.

And truly it was said that sprightly ladies, working between love and pleasure times, drew from the court fool for their conception of the mythological buffoon, reproducing Triboulet's great head; his mouth, proportionately large; his protruding eyes; his bowed back, short, twisted legs and long, muscular arms; and his nose far larger than that of Francis, who otherwise had the largest nose in the kingdom.

But how could they depict the meanness of soul that dwelt in that extraordinary shell? The blithesome tapestry-makers, albeit adepts in form, grace and harmony, could not touch the subjectiveness of existence. Thus it was a double pleasure for Triboulet to see, limned in well-chosen hues, his form, the crookedness of which he was as proud as any courtier of his symmetry and beauty, the while his dark, vain soul lay concealed behind the mask of merry deformity and laughing monstrosity.

"Would your Majesty like to command me?"

The mocking feminine voice recalled Triboulet from his pleasing contemplation.

"No, no!" he answered, sullenly, and condescended to turn his glance upon the assemblage.

Over a goodly gathering of jesters, buffoons, poets, and even philosophers, he lorded it, holding his head as high as his hump would permit and conscious of his own place in the esteem of the king. Not long ago the monarch had laughed and applauded when Triboulet had twisted his features into a horrid grimace, and since then the dwarf's little heart had expanded with such arrogance, it seemed to him he was almost Francis himself as he sat there on Francis' sometime throne; and these Sir Jollys were his subjects all—Marot, Caillette, Brusquet, Villot, and the lesser lights, jesters of barons, cardinals and even bishops! Rabelais, too, that poor, dissolute devil of a writer, learned as Homer, brutish as Homer's swine—all subjects of his, the king of jesters, save one; one whom he eyed with certain fear and wonder; fear, because she was a woman—and Triboulet esteemed all the sex but "highly perfected devils"—and wonder, at finding her different from, and more perplexing than even the rest of her kind!

"Jacqueline!—"

now she was perched on one corner of the table, and her face had a witch-like loveliness, as though borrowing its pallor and beauty from the moon, source of all magic and necromancy. Her eyes shone with such luster that, seeking their hue, they held the observer's gaze in mocking languor, and cheated the inquisitive coxcomb of his quest, the while the disdainful lips curved laughingly and so bewildered him, he forgot the customary phrases and stood staring like a nonny. Her footstep fell so light, she was so agile and quick, the superstitious dwarf swore she was but a creature of the night and held surreptitious meetings with all the familiar spirits of demonology. As she never denied the uncanny imputation, but only displayed her small white teeth maliciously, by way of answer, Triboulet felt assured he was right and crossed himself religiously whenever she gazed too fixedly at him.

A most gracieuse folle, her dress was in keeping with her character, yellow being the predominating color. To the fanciful adornment of the gown her lithe figure lent itself readily, while her rebellious curls were well adapted to that badge of her servitude, the jaunty cap that crowned their waving abundance.

In especial disdain, from her position upon the corner of the table, her glance wandered down the board and rested on Rabelais, the gourmand, before whom were an empty trencher and tankard. The priest-doctor-writer-scamp who affected the company of jesters and liked not a little the hospitality of Fools' hall, which adjoined the pastry branch of the castle kitchen and was not far removed from the wine butts, had just unrolled a bundle of manuscript, all daubed with trencher grease and tankard drippings, and was about to read aloud the strange adventures of one Pantagruel, when, overcome by indulgence, his head fell forward on the table, almost in the wooden platter, and the papers fluttered to the floor.

"Put him out!" commanded Triboulet from his high place.

But she of the jaunty cap sprang from the table.

"How wise are your Majesty's decrees!" she said mockingly with her glance upon the dwarf. He shifted uneasily in the throne. "You should have put him out before! But now"—turning contemptuously to the poor figure of the great man—"he's harmless. His silence is golden; his speech was dross."

"And yet," answered Marot, thoughtfully, "the king esteems him; the king who is at once scholar, poet, wit, soldier—"

"Soldier!" she exclaimed, quickly. "When he can not conquer Italy and regain his heritage!"

"Can not?" ventured Triboulet, mindful of the dignity of his royal master. "Why not?"

"Because the women would conquer him!"

"Nay; the king prefers the blue eyes of France," spoke up the cardinal's fool, he of the viola.

"Then do you set our queen of fools, our fair Jacqueline, out of his Majesty's good graces," interposed one of the lesser jesters, a mere baron's hireling, who long had burned with secret admiration for the maid of the coquettish cap.

"I am such a fool as to want the good graces of no man—or monarch!" she replied boldly, without glancing at the speaker.

"An he were in love, you would be two fools!" laughed Caillette, the court poet.

"In love, 'tis only the man is the fool or—the fooled!" she returned pointedly, and Caillette, despite his self-possession, flushed painfully. Since Diane de Poitiers had wedded her ancient lord, the poet had become grave, studious, almost sad.

"And is your mistress, the king's ward, fooling with her betrothed?" he asked quickly, conscious of knowing winks and nudges.

"The Princess Louise and the Duke of Friedwald are to wed for reasons of state," said the young woman, gravely. "There'll be no fools."

"Ah, a loveless match!"

"But not a landless one!" retorted she of the cap without the bells. "Besides, it cements the friendship of Francis and Charles V! What more would you? But I'll tell you a secret."

At that the company flocked around her, as though there was something enticing in her tone; the vague promise of an interesting bit of gossip or the indefinite suggestion of a court scandal.

"A secret!" said the cardinal's fool, rubbing his hands together. His master often rewarded him for particularly choice morsels of loose tittle-tattle.

"Oh, nothing very wicked!" she answered, waving them back with her small hand. "'Tis only that they play at make-believe in love, the princess and her betrothed! But after all, it is far more sensible than real love-making, where if the pleasure be more acute, the pangs are therefore the greater. She addresses to him the tenderest counterfeit verses; he returns them in kind. She even simulated such an illusory sadness that the duke has sent his own jester, who has but just arrived at court, to amuse her (ahem!) dullness, until he himself could come!"

At this the cardinal's buffoon looked disappointed, for his master liked more highly-flavored hearsay, while Triboulet frowned and brought down his heavy fist upon the arm of the throne.

"A new jester forsooth!" he exclaimed.

"And why not?" Lifting her swart brows, quizzically.

"We are already overstocked with 'prentice fools," he retorted, looking over the throng.

"Ah, you fear perhaps some one may depose you?" remarked Jacqueline coldly.

A guarded laugh arose from the gathering and the dwarf's eyes gleamed.

"Depose me, Triboulet!" he shouted, rising. "Triboulet is sovereign lord of all at whom he mocks! His wand is mightier than an episcopal miter!"

In his overweening rage and vanity he fairly crouched before the throne, eying them all like a cat. His thick lips trembled; his eyes became bloodshot.

He forgot all prudence.

"Doth not the king himself seek my advice?" He laughed horribly. "Hath not, perhaps, many a fair gentleman been burned—aye, burned to ashes as a Calvinist!—at my suggestion!"

"Miserable wretch! Spy!" exclaimed the young woman, paler than a lily, as she bent her eyes, with fully opened lids, upon him.

As if to shield himself, he raised his hand, yet drunkenness or wrath overcame caution and superstition, and the red eyes met the dark ones. But a moment, and the former dropped sullenly; a strange thrill ran through him. He thought he was bewitched.

"Non nobis Domine!" he murmured, striving to recall a hymn. As Latin was the language of witchcraft, so, also, was it the antidote. Contemptuously she turned her back and walked slowly to the fire. Upon her white face and supple figure played the elfish glow, lighting the little cap and the waving tresses beneath.

Regarding her furtively, Triboulet's courage returned, since she was looking at the coals, not at him.

"Ho, ho!" he said jocosely. "You all thought I was sincere. Listen, my children! The art of fooling lies in trumped-up earnestness." He smiled hideously.

"Bravo, Triboulet!" cried an admiring voice.

"Only time and art can give you such mastery over the passions," continued the jester. "Which one of you would depose me? Who so ugly as I? Poets, philosophers! I snap my fingers at them. Poor moths! And you dare bait me with a new-comer! Let him look to himself!" From earnestness to grandiloquence was but a step.

"Let him come!" And Triboulet, imitating the pose of Francis himself, drew his wooden sword.

"Let him come!" he repeated, fiercely.

"Who?" called out a gay and reckless voice.

Through the doorway leading into the kitchen stepped a young man; slender, almost boyish in appearance, with light-brown hair and deep-set eyes that belied the gaiety and mirth of his features. His costume, that of a Jester, was silk of finest texture and design, upon which were skilfully fashioned in threads of silver the arms of Charles V, King of Spain and Emperor of Germany, the powerful rival of Francis, whose friendship now, for reasons of state, the latter sought.

Smilingly the foreign jester gazed around the room; at the unusual furnishings, picturesque, yet appropriate; at the inmates, the fools scattered about the great board or near the mighty fireplace; the renowned philosopher, Rabelais, sleeping on his arms, with hand outstretched toward the neglected tankard; at the striking appearance of the girl who looked with casual, careless interest upon him; at the grotesque, crook-backed figure before the throne.

And observing the incongruity of his surroundings, he laughed lightly, while his glance, turning inquiringly if not insolently, from one to the other, lingered in some surprise upon the young woman. He had heard that in far-away France the motley was not confined to men. Had not Jeanne, queen of Charles I, possessed her jestress, Artaude de Puy, "folle to our dear companion," as said the king? Had not Madame d'Or, wearer of the bells, kept the nobles laughing? Had not the haughty, eccentric Don John, his handsome, merry joculatrix, attached to his princely household?

But knowing only by rumor of these matters, the jester from abroad looked hard at her, the first madcap in petticoats he had ever seen. For her part, Jacqueline bore his scrutiny with visible annoyance.

"Well," she said impatiently, a flash of resentment in her fine eyes, "have you conned me over enough?"

"Too much, mistress," he replied in no wise abashed, "an it hath displeased you. Too little to please myself."

"Yourself!" she returned, with sudden anger at his persistent gaze. "Some lord's plaything to beat or whip; a toy—"

"And yet a poet who can make rhymes on woman's beauty," he answered with a careless laugh.

"Another courtier!" grumbled Triboulet. "Lacking true wit, fools nowadays essay only compliments to cover their dullness."

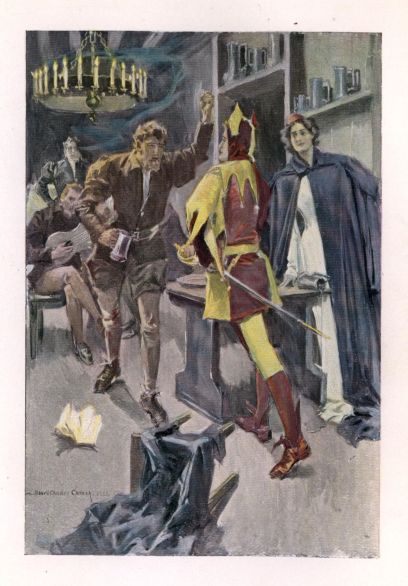

With the same air of insolent amusement, the new-comer turned to the throne and its occupant, whom he subjected to an even more deliberate investigation.

"Is it man or manikin, gentle mistress?" he asked, after concluding his examination.

She did not deign to answer, but the offended Triboulet waved his wooden sword vindictively.

"Manikin!" he roared, and sprang with vicious lunges upon the duke's jester, who falling back before the suddenness of the assault, whipped out his weapon in turn, and, laughing, threw himself into an attitude of defense.

"A mortal combat!" cried the cardinal's wit-snapper.

"Charles V and Francis!" exclaimed Caillette, referring to the personal challenge which had once passed between the two great monarchs. "With a throne for the victor!" he added gaily, indicating Triboulet's chair of state.

The clatter and din awoke Rabelais, who drowsily regarded the combatants with lack-luster gaze and undoubtedly thought himself once more amid the fanciful conflicts of fearful giants.

"Fall to, Pantagruel, my merry Paladin!" he exclaimed bombastically. "Cut, slash, stab, fence and justle!" And himself, reaching for an imaginary sword, encountered the tankard which he would have raised to his lips but that his shaggy head fell again to the board before his willing arm had obeyed the passing impulse of his sluggish brain.

"Fence!—justle!" he murmured, and slept once more.

But the parrot, again disturbed, could not so easily compose itself to slumber. Whipping its head from its downy nest, it outspread its gray wings gloriously and screamed and shouted, as though venting all the thunders of the Vatican upon the offending belligerents. And above the uproar and noise of arms, rabble and bird, arose the piercing voice of Triboulet:

"Watch me spit this bantam-cock!"

Tough and sharp-pointed, a wooden sword was no insignificant weapon, wielded by the thews and sinews of a Triboulet. Crouching like an animal, the king's buffoon sprang with headlong fury, uttering hoarse, guttural sounds that awakened misgivings regarding the fate of his too confident antagonist.

"Do not kill him, Triboulet!" cried Marot, alarmed lest the duke's fool should be slain outright. "Remember he has journeyed from the court of Charles V!"

"Charles V!" came through Triboulet's half-closed teeth. "My master's one great enemy!"

"Hush!" muttered Villot. "Our master's enemy is now his dear friend!"

"Friend!" sneered the other, but even as he thrust, his sword tingled sharply in his hand, and, whisked magically out of his grip, described a curve in the air and fell at a far end of the room. At the same time a stinging blow descended smartly on the dwarf's hump.

"Pardon me!" laughed the duke's fool. "Being unused to such exercise, my blade fell by mistake on your back."

If looks could have killed, Triboulet would have achieved his original purpose, but after a vindictive though futile glance his head drooped despondently. To have been thus humiliated before those whom he regarded as his vassals! What jest could restore him the prestige he had enjoyed; what play of words efface the shame of that public chastisement? Had he been beaten by the king—but thus to suffer at the hand of a foreign fool! And the monarch—would he learn of it?—the punishment of the royal jester? As in a dream, he heard the hateful voices of the company.

"'Tis not the first time he has been wounded—there!" said fearless Caillette, who openly acknowledged his aversion for the king's favorite fool. "But be seated, gentle sir," he added to the stranger, "and share our rough hospitality."

"Rough, certes!" commented the other, as he returned his blade to his belt. "And as I see no stool—"

"There's the throne!" returned Caillette, courteously. "Since you have overcome Triboulet, his place is yours."

"A precarious place!" said the new-comer, easily, dropping, nevertheless, into the chair.

"The king is dead! Long live the king!" cried the cardinal's jester.

"Long live the king!" they shouted, every fool and zany raising a tankard, save the dwarf and the young woman, the former continuing to glare vindictively upon the usurper, and the latter to all intent remaining oblivious of the ceremony of installation. Poised upon a chair, she idly thrust her fingers through the gilded bars of the cage that hung from the rafters and gently stroked the head of the now complaisant bird.

"Poor Jocko! Poor Jocko!" she murmured.

"La!—la!—la!—" sang the parrot, responsive to her light caress.

"Your Majesty's wishes! Your Majesty's decree!" exclaimed the monastic wit-worm.

"Hear! hear!" roared Brusquet.

"Silence!" commanded Marot. "His Majesty speaks."

"Toot! toot! toot!" rang out the flourish of a trumpet, a clarion prelude to the fiat from the throne.

The new king in motley arose; heedless, devil-may-care, very erect in his preposterously pointed shoes.

"I appoint you, Thony, treasurer of the exchequer, because you are quick at sleight-of-hand," he began.

"Good," laughed Marot. "An he's more light-fingered than his predecessor, he's a master of prestidigitation!"

"You, Brusquet," went on the new master of Fool's hall, "I reward with the government of Guienne, for he who governs his own house so ill is surely fitted for greater tasks of incompetency."

This allusion to the petticoat rule which dominated the luckless jester at home was received in good part by all save the hapless domestic bondman himself.

"You, Villot, are made admiral of the fleet."

Villot smiled, thinking how Francis had but recently bestowed that office upon the impoverished husband of pretty Madame d'Etaille.

"Thanks, your Majesty," he began, "but if some post nearer home—"

"You are to sail at once!"

"But my wife—"

"Will remain at court!" announced the duke's jester with great decision.

Villot made a wry face. The king in motley smiled significantly. "A safe haven, Villot! Besides, remember a court without ladies is like a spring without flowers."

A movement resembling apprehension swept through the company. The epigram had been Francis'; the court—a flower-bed of roses—was, in consequence, a thorny maze for a jester to tread. From her chair at the far end of the room, the young woman looked at the new-comer for the first time since his enthronement. Her fingers yet played between the gilded bars; the posture she had assumed set forth the pliant grace of her figure. Above the others, she glanced at him, her hair very black against the golden cage; her arm, very white, half unsheathed from the great hanging sleeve.

"You are over-bold," she said, a peculiar smile upon her lips.

"Nay; I have spoken no treason, mistress," he retorted blithely.

"Not by word of mouth, perhaps, but by imputation."

He raised his brows with a gesture of wanton protest, while the face before him clouded. Her eyes held his; her little teeth just gleamed between the crimson of her lips.

"I presume you consider Charles the more fitting monarch?" she continued.

Was it the disdain of her voice? Did she read his passing thoughts? Did she challenge him to utter them?

"In truth," the jester said carelessly, "Charles builds fortresses, not pleasure palaces; and garrisons them with soldiers, not ladies."

She half-smiled. Her glance fell. Her hand moved caressingly, the sleeve waving beneath.

"Poor Jocko! Poor Jocko!" she murmured.

Triboulet's glance beamed with delight. She was casting her spell over his enemy.

"Oh," muttered Triboulet, "if the king could but have heard!"

Perhaps it was a breath of air, but the tapestry depicting the misadventures of Momus waved and moved. Triboulet, who noted everything, saw this, and suffered an expression of triumph momentarily to rest upon his malignant features. Had his prayer been answered? "A spring without flowers," forsooth! Dearly cherished the august gardener his beautiful roses. Great red roses; white roses; blossoms yet unopened!

Following his gaze, a significant light appeared in the young woman's eyes, while her arm fell to her side.

"Now to see Presumption sue for pardon," she whispered to herself.

One by one the company, too, turned in the direction Triboulet was looking. In portraiture the classical buffoon grinned and gibed at them from the tapestry; and even from his high station above the clouds Jupiter, who had ejected the offending fool of the gods, looked less stern and implacable. An expectant hush fell upon the assemblage, when suddenly Jove and Momus alike were unceremoniously thrust aside, and, as the folds fell slowly back, before the many-hued curtain stood a man of stately and majestic mien.

A man whose appearance caused deep-seated consternation, whose forbidding aspect made the very silence portentous and terrifying. With dress slashed and laced, rich in jewelry and precious stones, he remained motionless, regarding the motley gathering, while an ominous half-smile played about his features. He said nothing, but his reserve was more sinister than language. Capricious, cruel was his face; in his eyes shone covert enjoyment of the situation.

Would he never speak? With one hand he stroked his beard; with the other he toyed with the lace on his doublet.

"You were talking, children," he said, finally, "before I came in."

"If your Majesty," ventured Triboulet, "has heard all, your Majesty will not blame—us!" And he glanced malevolently toward the duke's Jester, who, upon the king's abrupt entrance, had descended from the platform.

Observing the emblazoned arms of Charles V upon the dress of the culprit, a faint look of surprise swept Francis' face. Did it recall that fatal day, when on the field of battle, a rival banner had waved ever illusively; ever beyond his reach? Now it shone before him as though mocking his friendship for his one-time powerful enemy, the only man he feared, the emperor who had overthrown him. The sinister smile of the king gave way to gloomy thoughtfulness.

"Who is this knave?" he asked at length, fixedly regarding the erstwhile badge of his defeat.

"A poor fool, Sire!" replied the kneeling man.

"Those arms, embroidered on your dress—what do they mean?" said the king shortly.

"The arms of my master's master, your Majesty!" was the over-confident answer.

"Who is your master?"

"The Duke of Friedwald, Sire, the betrothed of the Princess Louise."

"And your purpose here?"

"My master sent me to the princess. 'I'll miss thee, rogue,' said he. ''Tis proof of love to send thee, my merry companion of the wine cup! But go! Nature hath formed thee to conjure sadness from a lady's face.' So I set out upon my perilous journey, and, favored by fortune, am but safely arrived. I was e'en now about to repair to the princess, whom I trust, in my humble way, to amuse."

"And thou shalt!" said the king, significantly.

"Oh, your Majesty!" with assumed modesty.

"That is," added Francis, "if it will amuse her to see you hanged!"

"And if it did not amuse her, Sire?" spoke up the new-comer, without a tremor in his voice.

"What then?" asked the king.

"It would be a breach of hospitality to hang me, the servant of the duke who is servant of Charles V!" he replied boldly.

Francis started. Like a menace shone the arms of the great emperor. Vividly he recalled his own humiliation, his long captivity, and mistrusted the power of his subtile, amiable friend-enemy. Friendship? Sweeter was hatred. But the promptings of wisdom had suggested the policy of peace; the reins of expediency drove him, autocrat or slave, to the doctrines of loving brotherhood. He turned his gloomy eyes upon the glowing countenance of Triboulet.

"What say you, fool?"

"Your Majesty," answered the eager dwarf, "could hang him without breach of hospitality."

"How do you make that good, Triboulet?" asked the monarch.

"The duke has given him to the princess. The princess is a subject of your Majesty. The king of France has jurisdiction over the princess' fool and surely can proceed in so small a matter as hanging him."

Francis bent a malignant look upon the young man. Behind the dwarf stood the jestress, now an earnest spectator of the scene.

"This new-comer's stay with us promises to be brief, Caillette," she whispered.

"Hark, you witch! He answers," returned the poet.

"What can he say?" she retorted, shrugging her shoulders. "He is already condemned."

"Are you pleased, mistress? Just because the poor fellow stared at you overmuch."

"Oh," she said, insensibly, "it was written he should hang himself. Now we'll hear how ably Audacity parleys with Fate."

"It would be no breach of hospitality, Sire, to hang the princess' fool," spoke the condemned man with no sign of waning confidence, "yet it would seem to depreciate the duke's gift. Your Majesty should hang the one and spare the other. 'Tis a matter of logic," he went on quickly, "to point out where the duke's gift ends and the princess' fool begins. A gift is a gift until it is received. The princess has not yet received the duke's gift. Therefore, your Majesty can not hang me, as the princess' fool; nor would your Majesty desire to hang me as the duke's gift."

Imperceptibly the monarch's mien relaxed, for next to a contest with blades he liked the quick play of words.

"Answer him, Triboulet," he said.

"Your Majesty—your Majesty—" stammered the dwarf, and paused in despair, his wits failing him at the critical juncture.

"Enough!" commanded the king, sternly. A sound of suppressed merriment even as he spoke startled the gathering. "Who laughed?" he cried suddenly. "Was it you, mistress?" fastening his eyes upon the young woman.

Her head fell lower and lower like some dark flower on a slender stem. From out of the veil of her mazy hair came a voice, soft with seeming humility.

"It might have been Jocko, Sire," she said. "He sometimes laughs like that."

The king looked from the woman to the bird; then from the bird to the woman, a gleam of recollection in his glance.

"Humph!" he muttered. "Is this where you serve your mistress? Look to it you serve not yourself ill!"

An instant her eyes flashed upward.

"My mistress is at prayers," she answered, and looked down again as quickly.

"And you meanwhile prefer the drollery of these madcaps to the attentions of our courtiers?" said Francis, more gently. "Certes are you gipsy-born!"

Her hands clasped tighter, but she answered not, and he turned more sternly to the new king of the motley. "As for you," he continued, "for the present the duke's gift is spared. But let the princess' fool look to himself. Remember, a guarded tongue insures a ripe old age, and even a throne in Fools' hall is fraught with hazard. Here! some of you, take this"—indicating the sleeping Rabelais—"and throw it into the horse-pond. Yet see that he does not drown—your heads upon it! 'Tis to him France looks for learning."

He paused; glanced back at the kneeling girl. "You, Mistress Who-Seeks-to-Hide-Her-Face, teach that parrot not to laugh!" he added grimly.

The tapestry waved. Mute the motley throng stared where the king had stood. A light hand touched the arm of the duke's fool, and, turning, he beheld the young woman; her eyes were alight with new fire.

"In God's name," she exclaimed, passionately, "let us leave. You have done mischief enough. Follow me."

"Where'er you will," he responded gallantly.

The sun and the breeze contended with the mist, intrenched in the stronghold of the valley. From the east the red orb began its attack; out of the west rode the swift-moving zephyrs, and, vanquished, the wavering vapor stole off into thin air, or hung in isolated wreaths above the foliage on the hillside. Soon the conquering light brightly illumined a medieval castle commanding the surrounding country; the victorious breeze whispered loudly at its gloomy casements. A great Norman structure, somber, austere, it was, however brightened with many modern features that threatened gradually to sap much of its ancient majesty.

"Fill up the moat," Francis had ordered. "'Tis barbaric! What lover would sigh beneath walls thirty feet thick! And the portcullis! Away with it! Summon my Italian painters to adorn the walls. We may yet make habitable these legacies from the savage, brutal past."

So the mighty walls, once set in a comparative wilderness, a tangle of thicket and underbrush, now arose from garden, lawn and park, where even the deer were no longer shy, and the water, propelled by artificial power, shot upward in jets.

Seated at a window which overlooked this sylvan aspect, modified if not fashioned by man, a young woman with seeming conscientiousness, told her beads. The apartment, though richly furnished, was in keeping with the devout character of its fair mistress. A brush or aspersorium, used for sprinkling holy water, was leaning against the wall. Upon a table lay an open psalter, with its long hanging cover and a ball at the extremity of the forel. Behind two tall candlesticks stood an altar-table which, being unfolded, revealed three compartments, each with a picture, painted by Andrea del Sarto, the once honored guest of Francis.

The Princess Louise, cousin of Francis' former queen, Claude, had been reared with rigid strictness, although provided with various preceptors who had made her more or less proficient in the profane letters, as they were then called, Latin, Greek, theology and philosophy. The fame of her beauty had gone abroad; her hand had been often sought, but the obdurate king had steadfastly refused to sanction her betrothal until Charles, the emperor, himself proposed a union between the fair ward of the French monarch and one of his nobles, the young Duke of Friedwald. To this Francis had assented, for he calculated upon thus drawing to his interests one of his rival's most chivalrous knights, while far-seeing Charles believed he could not only retain the duke, but add to his own court the lovely and learned ward of the king.

And in this comedy of aggrandizement the puppets were willing—as puppets must needs be. Indeed, the duke was seriously enamored of the princess, whose portrait he had seen in miniature, and had himself importuned the emperor to intercede with Francis, knowing that the only way to the lady's hand was through the good offices of him who aspired to the mastery of all Europe, if not the world.

Charles, unwilling to disoblige one whose principality was the most powerful of the Austrian provinces he sought to absorb in his scheme for the unification of all nations, offered no demur to a request fraught with advantage to himself. Besides, cold and calculating though he was, the emperor entertained a certain affection for the duke, who on one occasion, when Charles had been sore beset by the troops of Solyman, had extricated his royal leader from the alternatives of ignominious capture or an untimely end. Accordingly, a formal proposal, couched in language of warm friendship to the king, was despatched by the emperor. When Francis, with some misgiving, arising from experience with womankind, laid the matter before Louise, she, to his surprise, proved her devotion and loyalty by her entire submissiveness, and the king, kissing her hand, generously vowed the wedding festivities should be worthy of her beauty and fealty.

Was she thinking of that scene now and the many messages which had subsequently passed between her distant lover and herself, as the white fingers ceased to tell the beads? Was she questioning fate and the future when the rosary fell from her hand and the clinking of the great glass beads on the hard floor aroused her from a reverie? Languidly she rose, crossed the room toward a low dressing table, when at the same time one of the several doors of the apartment opened, admitting the jestress, Jacqueline, whose long, flowing gown of dark green bore no distinguishing mark of the motley she had assumed the night before. The dreamy, almost lethargic, gaze of the princess rested for a moment upon the ardent eyes of the maid who stood motionless before her.

"The duke's jester who arrived last night awaits your pleasure without," said the girl.

"Bid him enter. Stay! The fillet for my hair. Seems he a merry fellow?"

"So merry, Madam, he mimicked the king last night in Fool's hall, beat Triboulet, appointed knaves in jest to high offices, and had been hanged for his forwardness but that he narrowly saved his neck by a slender device."

"What; all that in so short a time!" exclaimed the princess. "A most presumptuous rogue!"

"The king, Madam, was behind the tapestry and heard it all: his appointment of Thony as treasurer, because he is apt at palming money; Brusquet, governor of Guienne, since he governs his own home so ill; and Villot, admiral of the fleet, that he might sail away and leave his pretty wife behind him."

"I'll warrant me the story is known to the entire court ere this," laughed the lady. "Won't Madame d'Etaille be in a temper! And the admiral when he hears of it—on the high seas! The king was eavesdropping, you say, and yet spared the jester? He must bear a charmed life."

"He dubbed himself the duke's gift, Madam, and boldly claimed privilege under the poor cloak of hospitality."

"Surely," murmured the princess, "there will be no lack of entertainment with this knave under the same roof. Too much entertainment, I fear me. Well, admit the bold fellow."

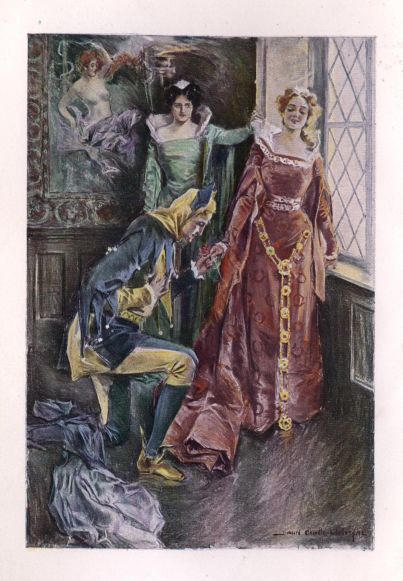

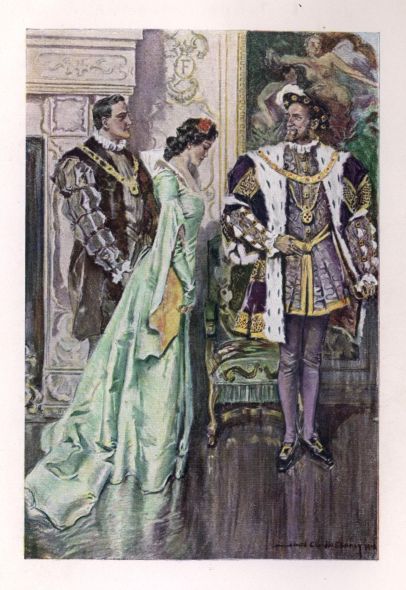

Crossing to the door, the maid pushed it back and the figure of the jester passed the threshold:—a figure so graceful and well-built, the lady's eyes, turning toward him with mild inquiry, lingered with approval; lingered, and were upraised to a fair, handsome face, when approval gave way to wonder.

Was this the imprudent, hot-brained rogue who had swaggered in Fools' hall, and made a farce of the affairs of the nation? His countenance seemed that of a courtier rather than a low-born scape-grace; his bearing in consonance, as, approaching the princess, he knelt near the edge of her sweeping crimson garment. Quietly the maid withdrew to a corner of the apartment where she seated herself on a low stool, her fingers idly playing with the delicate carvings of a vase of silver, containing water that had been blessed and standing conveniently near the aspersorium.

"You come from the Duke of Friedwald, fool?" said the mistress, recovering from her surprise.

"Yes, Princess."

Louise smiled, and looked toward the maid as if to say: "Why, he's a model of decorum!" but the girl continued regarding the figures on the vase, seemingly indifferent to the scene before her.

"I hear, sirrah, but a poor account of your behavior last night," continued the princess. "You must have a care, or I shall send you back to the duke and command him to have you whipped. You have been here but overnight, yet how many enemies have you made? The king; the admiral, and—last but not least—a certain lady. Poor fool! you may have saved your neck, but for how long? Fie! what an account must I give of you to your master!"

"Ah, Madam," he answered quickly, "you show me now the folly of it all."

"Let me see," she went on more gently, "what we may do, since you are penitent? The king may forgive; the admiral forget, but the lady—she will neither forget nor forgive. Fortunately, I think she fears to disoblige me, and, if I let it be known you are an indispensable part of my household—" she paused thoughtfully—"besides, she has a little secret she would keep from the king. Yes; the secret will save you!" And Louise smiled knowingly, as one who, although most devout, perhaps had missed a few paters or credos in listening to idle worldly gossip.

"Madam," he said, raising his head, "you overwhelm me with your goodness."

"Oh, I like her not; a most designing creature," returned the lady carelessly. "But you may rise. Hand me that embroidery," she added when he had obeyed. "How do I know the duke, my betrothed, whom I have never seen, has not sent you to report upon my poor charms? What if you were only his emissary?"

"Princess," he answered, "I am but a fool; no emissary. If I were—"

"Well?"

She smiled indulgently at the open admiration written so boldly upon his face, and, encouraged by her glance, he regarded her swiftly, comprehensively; the masses of hair the fillet ill-confined; eyes, soft-lidded, dreamy as a summer's day; a figure, pagan in generous proportions; a foot, however, petite, Parisian, peeping from beneath a robe, heavy, voluminous, vivid!

"If you were?" she suggested, passing a golden thread through the cloth she held.

"I would write him the miniature he has of you told but half the truth."

"So you have seen the miniature? It lies carelessly about, no doubt?" Yet her tone was not one of displeasure.

"The duke frequently draws it from his breast to look at it."

"And so many handsome women in the kingdom, too!" laughed the princess. "A tiny, paltry bit of vellum!"

Her lips curled indulgently, as of a person sure of herself. Did not the fool's glance pay her that tribute to which she was not a stranger? Her lashes, suddenly lifted, met his fully, and drove his look, grown overbold, to cover. The princess smiled; she might well believe the stories about him; yet was not ill-pleased. "Like master; like man!" says the proverb. She continued to survey the graceful figure, well-poised head and handsome features of the jester.

"Tell me, sirrah," she continued, "of the duke. Straightforwardly, or—I'll leave thee to the mercy of madam the admiral's wife! What is he like?"

"A fairly likely man!"

"'Tis what one says of a man when one can say nothing else. He is not then very handsome?"

"He has never been so considered!"

The princess' needle remained suspended, then viciously plunged into the golden Cupid she was embroidering. "The king hath played with me," she murmured. "He represented him as one of the most distinguished-appearing knights in the emperor's domains. Is he dark or light?" she went on.

"Dark."

"Tall?"

"Rather short."

"His eyes?" said the lady, after an ominous pause.

"Brown."

"His manners?"

"Those of a soldier."

"His speech?"

"That of one born to command."

"Command!" returned the princess, ironically. "Odious word!"

"You, Madam," quickly answered the jester, "he would serve."

A moment her glance challenged his, coldly, proudly, and then her features softened. The indolent look crept into her eyes once more; the tension of her lips relaxed.

"Command and serve!" laughed the princess. "A paradox, if not a paragon, it seems! Not handsome—probably ugly!—a soldier—full of oaths—a blusterer—strong in his cups! What a list of qualifications! Well"—with a sigh—"what must needs be must be! The emperor plays the rook; Francis moves his pawn—my poor self. The game, beyond the two moves, is naught to us. Perhaps we shall be sacrificed, one or both! What of that, if it's a draw, or one of the players checkmates the other—"

"But, Princess," cried the fool, "he loves you! Passionately!—devotedly!—"

"A passing fancy for a painted semblance!" said the lady, as rising she turned toward the casement, the golden Cupid falling from her lap to the floor. In the rhythmic ease of her movement, in her very attitude, was consciousness of her own power, but to the poet-jester, surrounded as he was by symbols of worship and devotion, her expressed self-doubt seemed that of some saintly being, cloistered in the solitude of a sanctuary.

"Nay," he answered swiftly, "he has but to see you—with the sunlight in your hair—as I see you now! The pawn, Madam, would become a queen; his queen! What would matter to him the game of Charles or Francis? Let Charles grow greater, or Francis smaller. His gain would be—you!"

The fingers of the maid who sat at the far end of the room ceased to caress the silver vase; her hands were tightly clasped together; in her dark eyes was an ironical light, as her gaze passed from the jester to her mistress. Almost motionless stood the princess until he had finished; motionless it would have seemed but for the chain on her breast, which rose and fell with her breathing. From the jeweled network which half-bound her hair shone flashes of light; a tress which escaped the glittering environment lay like a serpent of gold upon the crimson of her gown where the neck softly uprose. A hue, delicately rich as the tinted leaves of orange blossoms, mantled her cheeks.

She shook her head in soft dissent. "Queen for how long?" she answered gently. "As long as gentle Claude was queen for Francis? As long as saintly Eleanor held undisputed sway?"

"As long as Eleanor is queen in the hearts of her people!" he exclaimed, passionately. "As long as France is her bridegroom!"

Deliberately she half-turned, the coil of gold falling over her shoulder. Near her hand, white against the dark casement, a blood-red rose trembled at the entrance of her chamber, and, grasping it lightly, she held it to her face as if its perfume symbolized her thoughts.

"Is there so much constancy in the world?" she asked musingly. "Can such singleness of heart exist? Like this flower which would bloom and die at my window? A bold flower, though! Day by day has it been growing nearer. Here," she added, breaking it from the stem and holding it to the jester.

"Madam!" he cried.

"Take it," she laughed, "and—send it to the duke!" Kneeling, he received it. "Thou art a fellow of infinite humor indeed. Equally at home in a lady's boudoir, or a fools' drinking bout. Come, Jacqueline, Queen Marguerite awaits our presence. She has a new chapter to read, but whether another instalment of her tales, or a prayer for her Mirror of the Sinful Soul, I know not. As for you, sir"—with a parting smile—"later we shall walk in the garden. There you may await us."

"Well, Sir Mariner, do you not fear to venture so far on a dangerous sea?" asked a mocking voice.

"A dangerous sea, fair Jacqueline?" he replied, stroking the head of the hound which lay before the bench. "I see nothing save smiling fields and fragrant beds of flowers."

"Oh, I recognize now Monsieur Diplomat, not Sir Mariner!" she retorted.

Beneath her head-dress, resembling in some degree two great butterfly wings, her face looked smaller than its wont. Laced tight, after the fashion, the cotte-hardie made her waist appear little larger than could be clasped by the hands of a soldier, while a silken-shod foot with which she tapped the ground would have nestled neatly in his palm. Was it pique that moved her thus to address the duke's jester? Since he had arrived, Jacqueline had been relegated, as it were, to the corner. She, formerly ever first with the princess, had perforce stood aside on the coming of the foreign fool whose company her mistress strangely seemed to prefer to her own.

First had it been talking, walking and jesting, in which last accomplishment he proved singularly expert, judging from the peals of laughter to which her mistress occasionally gave vent. Then it had become riding, hawking and, worst of all, reading. Lately Louise, learned, as has been set forth, in the profane letters, had displayed a marked favor for books of all kinds—The Tree of Battles, by Bonnet, the Breviary of Nobles in verse, the "Livre des faits d'armes et de chevalerie," by Christine de Pisan; and in a secluded garden spot, with her fool and servant, she sedulously pursued her literary labors.

As books were rare, being hand-printed and hand-illumined, the princess' choice of volumes was not large, but Marguerite, the king's sister, possessed some rarely executed poems—in their mechanical aspect; the monarch permitted her the use of several precious chronicles; while the abbess in the convent near by, who esteemed Louise for her piety and accomplishments, submitted to her care a gorgeously painted, satin-bound Life of Saint Agnes, a Roman virgin who died under the sanguinary persecution of Diocletian. But Jacqueline frowningly noticed that the saint's life lay idle—conspicuously, though fittingly, on the altar-table—while a manuscript of the Queen of Navarre suspiciously accompanied the jester when he sought the pleasant nook selected for reading and conversation.

It was to this spot the maid repaired one soft summer afternoon, where she found the fool and a volume—Marguerite's, by the purple binding and the love-knot in silver!—awaiting doubtless the coming of the princess; and at the sight of them, the book of romance and the jester who brought it, what wonder her patience gave way?

"You have been here now a fortnight, Monsieur Diplomat," she continued, bending the eyes which Triboulet so feared upon the other.

"Thirteen days, to be exact, sweet Jacqueline!" he answered calmly.

"Indeed! Then there is some hope for you, if you've kept track of time," she returned pointedly.

Still he forbore to qualify his manner, save with a latent smile that further exasperated the girl.

"What mean you, gentle mistress?" he asked quietly, without even looking at her.

"'Sweet Jacqueline!' 'Gentle mistress!' you are profuse with soft words!" she cried sharply.

"And yet they turn you not from anger."

"Anger!" she said, her eyes flashing. "Not another man at court would dare to talk to me as you do."

At this he lifted his brows and surveyed her much as one would a spoiled child, a glance that excited in her the same emotion she had experienced the night of his arrival in Fools' hall, when he had contemplated her in her garb of Joculatrix, as some misplaced anomaly.

"I know, mistress," he returned ironically, "you have a reputation for sorcery. But I think it lies more in your eyes than in the moon."

"And yet I can see the future for all that," she replied, persistently, defiantly.

"The future?" he retorted, and looked from the earth to the sky. "What is the goal of yonder tiny cloud? Can you tell me that?"

"The goal?" she repeated, uplifting her head. "Wait! It is very small. The sun is already swallowing it up."

"Heigho!" yawned the jester, outstretching his yellow-pointed boot, "I catch not the moral to the fable—an there be one!

"The moral!" she said, quickly. "Ask Marot."

"Why Marot?" Balancing the stick with the fool's head in his hand.

"Because he dared love Queen Marguerite!" she answered impetuously. "The fool in motley; the lady in purple! How he jested at her wedding! How he wept when he thought himself alone!"

"He had but himself to blame, Jacqueline," returned the other with composure, although his eyes were now bent straight before him. "He could not climb to her; she could not stoop to him. Yet I daresay, it was a mad dream he would not have foregone."

"Not have foregone!" she exclaimed, quickly. "What would he not have given to tear it from his breast; aye, though he tore his heart with it! That day, bright and fair, when Henry d'Albret, King of Navarre, took her in his arms and kissed her brow! When amid gay festivities she became his bride! Not have foregone? Yes; Marot would forego that day—and other days."

Still that inertia; that irritating immobility. "What a tragic tale for a summer day!" was his only comment.

"And Caillette!" she continued, rapidly. "Distinguished in mien, graceful in manner. In the house of his patron, he dared look up to that nobleman's daughter, Diane de Poitiers. A dream; a youthful dream! Enter Monsieur de Brézé, grand seneschal of Normandy. Shall I tell you the rest? How Caillette stares, moody, knitting his brows at his cups! Of what is the jester thinking?"

"Whether the grand seneschal will let him sleep with the spaniels, Jacqueline, or turn him out," laughed the jester.

Angrily she clasped her hands before her. "Is it the way your mind would move?" she retorted.

"A jester without a roof to cover him is like a dog without a kennel, mistress."

Disdain, contempt, rapidly crossed her face, but her lip curved knowingly and her voice came more gently, because of the greater sting that lay behind her words.

"You but seek to flout me from my tale," she said sweetly. "Caillette is none such, as you know. They were young together. 'Twas said he confessed his love; that tokens passed between them. Rhymes he writ to her; a flower, perhaps, she gave him. A flower he yet cherishes, mayhap; dried, faded, yet plucked by her!"

Involuntarily the hand of her listener touched his breast, the first sign he had made that her story moved him. Jacqueline, watching him keenly, smiled, and demurely looked away. Her next words seemed to dance from her lips, as with head bent, like a butterfly poised, she addressed her remark to vacancy.

"A flower for himself, no doubt! Not given him for another!"

Whereupon she turned in time to catch the burning flush which flamed his cheek and left it paler than she had ever seen it. At this first signal of her success—proving that he was not impregnable to her attack—she hummed a little song and beat time on the sward with a green-shod foot.

"What mean you?" he asked, momentarily dropping his unruffled manner.

"Not much!" Lightly she tripped to a bush, broke off a flower and regarded it mischievously. "Why should people hide that which is so sweet and fragrant?" she remarked, and set the rose in her hair.

"Hide?" he said, looking at the flower, but not at her.

"I trust you kept the rose, Monsieur Diplomat?" she spoke up, suddenly, her expression most serious.

"What rose?" he asked, now become restless beneath her cutting tongue.

"What rose! As if you did not know! How innocent you look! How many roses are there in the world? A thousand? Or only one? What rose? Her rose, of course. Have you got it? I hope so—for the duke is coming and might ask for it!"

This, then, was the information she had taken such a roundabout way to communicate! It was to this end she had purposely led the conversation by adroit stages, studying him gaily, impatiently or maliciously, as she marked the effect of her words upon him. All alive, she stepped back laughing; elate, she put her arms about a branch of the rose-bush and drew a score of roses to her bosom, as though she were a witch, impervious to thorns. He had risen—yes, there was no doubt about it!—but her sunny face was turned to the flowers. His countenance became at once puzzled and thoughtful.

"The duke—coming—" He condescended to ask for information now.

Sidewise she gazed at him, unrelenting. "Does the flower become me?" she asked.

"The duke—coming—" he repeated.

"How impolite! To refuse me a compliment!" she flashed.

The next moment he was by her side, and had taken her arm, almost roughly. "Speak out!" he cried. "Some one is coming! What duke is coming?"

"You hurt me!" she exclaimed, angrily. He loosened his grasp.

"What duke?" she answered scornfully. "Her duke! Your duke! The emperor's duke!"

"The Duke of Friedwald?" he asked.

"Of course! The princess' fiancé; bridegroom-to-be; future husband, lord and master," she explained, with indubious and positive iteration.

"But the time—set for the wedding—-has not expired," he protested with what she thought seemed a suspicion that she was playing with him.

"That is easily answered," she said cheerfully. "The duke, it seems, has become more and more enamored. Finally his passion has so grown and grown he fears to let it grow any more, and, as the only way out of the difficulty, petitioned the king to curtail the time of probation and relieve him of the constantly augmenting suspense. To which his most gracious Majesty, having been a lover himself (on divers occasions) and measuring the poor fellow's troubles by the qualms he has himself experienced, has seen generously fit to cut off a few weeks of waiting and set the wedding for the near future."

"How know you this?" he demanded, sharply, striding to and fro.

"This morning the princess sent me with a message to the Countess d'Etampes. You know her? You have heard? She has succeeded the Countess of Châteaubriant. Well, the king was with her—not the Countess of Châteaubriant, but the other one, I mean. They left poor me to await his Majesty's pleasure, and, as the Countess d'Etampes has but newly succeeded to her present exalted position and the king has not yet discovered her many imperfections, I should certainly have fallen asleep for weariness had I not chanced to overhear portions of their conversation. The Countess d'Etampes, it seemed, was very angry. 'Your Majesty promised to send her home,' she said. 'But, my dear, give me time,' pleaded the king. 'Pack her off at once,' she demanded, raising her voice. 'Send her to her husband. That's where she belongs. Think of him, poor fellow!' Laughing, his Majesty capitulated. 'Well, well, back to her castle goes the Countess of Châteaubriant!' Thereupon—"

"But the duke, mistress," interrupted the jester, who had become more and more impatient during the prolonged narration. "The duke?"

"Am I not to tell it in my own way?" she returned. "What manners you have! First, you pinch my arm until I must needs cry out. Then you ask a question and interrupt me before I can answer."

"Interrupt!" he muttered. "You might have told a dozen tales. What care I for the king's Jezebels?"

"Jezebels!" she repeated, in mock horror. "I see plainly, if you don't die one way, you will another."

"'Tis usually the case. But go on with your story."

"If I can not tell it in my own way—"

"Tell it as you will, if your way be as slow as your tongue is sharp," he answered sullenly.

"Sharp! Jezebels! You deserve not to hear, but—the king, it seems, had laid the duke's request before the Countess d'Etampes. 'Here is an impatient suitor,' he said gaily. 'How shall we cure his passion?' 'By marrying him,' blithely answered this light-of-love. ''Tis a medicine that never fails!' His Majesty frowned; I could not see him, but felt sure of it from his tone, for although he neglects the queen, yet, to some degree, is mindful of her dignity. 'Marriage is a holy state, Madam,' he replied severely. 'There's no doubt about it, Francis,' returned the lady, 'and therefore is the antidote to passion. But a man bent on matrimony is like a child that wants a toy. Better give it to him at once—the plaything will the sooner be thrown aside!' 'Nay, Madam,' he said reprovingly, 'the duke shall have his wish, but for no such reason.' 'What reason then?' quoth she, petulantly. 'Because thou hast shown me love is a monarch stronger than any king and that we are but as slaves in its hands!' he exclaimed, passionately. 'I know I shall like the duke,' cried she, 'since he is the cause of that pretty speech.'

"At this point, not daring to listen longer, I coughed; there was silence; then the countess herself appeared at the door and looked at me sharply. With such grace as I could command, I delivered my message, left the house and was hurrying through the garden when chance threw you in my way. And now you have it all, sir."

"The princess—has she heard the king has received a letter from the duke, and that his Majesty has changed the wedding date?"

The jester spoke slowly, but Jacqueline was assured that beneath his deliberate manner surged deep and conflicting emotions; that his calmness was no more than a mask to conceal his pain. Had he given utterance to the feeling that beset him, had he betrayed more than a suggestion of the passion, rage or grief which struggles for mastery beneath a forced sloth of sensibility, she would have once more mocked him with laughter. But perhaps his very quiescence inclined her to look upon him with a grain of sympathy or compassion, for her tones were now grave.

"The princess knows; has heard all from the king. Not long since he sent for her. Will she consent? What else can she do? 'Tis the monarch who commands; we who obey!"

"Is the court then only a mart, a guildhall?" he exclaimed. "A woman—even a princess—should be won, not—exchanged!"

Her lashes drooped; in her gaze shone once more the ironical amusement. "Why," she said, "from what wilds, or forests, have you come? The heart follows where the trader lists! Think you the princess will wear the willow?" she laughed. "How well you know women!"

"Do you mean that she—"

"I mean that her welfare is in strong hands; that there will be few greater in all the land; none more honored! The duke's principality is vast—but here comes the princess." The hound sprang to his feet and ran gamboling down the path. "Ask her the rest yourself, most Unsophisticated Fool! Ah,"—with a touch she could not resist—"what a handsome bride she will make for the duke!"

Through the flowery path, so narrow her gown brushed the leaves on either side, the Princess Louise appeared, walking slowly. A head-dress, heart-shaped, held her hair in its close confines; the gown of cloth-of-silver damask fitted closely to her figure, and, from the girdle, hung a long pendent end, elaborately enriched. With short, sharp barks, the dog bounded before her, but the hand usually extended to caress the animal remained at her side.

Intently the jester watched her draw near and ever nearer, their common trysting spot, her favorite garden nook. A handsome bride, forsooth, as Jacqueline had suggested. All in white was she now; a glittering white, with silver adornment; ravishingly hymeneal. A bride for a duke—or a king—more stately than the queen; handsomer than the favorite of favorites who ruled the king and France.

"Jacqueline," she said, evincing neither surprise nor any other emotion, as she approached, "go and fetch my fan. I believe 'tis in the king's ante-chamber."

"Madam carried no fan when"—began the girl.

"Then 'tis somewhere else. Do not bandy words, but find it."

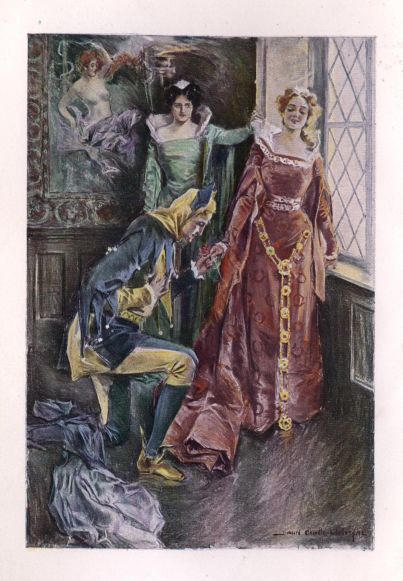

Sinking on the bench as the maid walked quickly away, she remained for some moments in silent thought,—a reverie the jester forbore to disturb. Her head rested on her arm, from which fell the flowing sleeve almost to the ground; her wrist was lightly inclasped by a slender golden band of delicate Byzantine enamel work; over the sculptured form of the stone griffin that constituted one of the supports of the ancient Norman bench flowed the voluminous folds of her dress, partly concealing the monster from view. Against the clambering ivy which for centuries had reveled in this chosen spot, and which the landscape gardeners of Francis had wisely spared, lay her hand, a small ring of curious workmanship gleaming from her finger. The ring caused the jester to start, remembering he had last seen it worn by the king.

Truly, the capricious, but august, monarch must have been well pleased with the complaisance of his fair ward, and the face of the fool, glowing and eager, became on the instant hard and cold. Did he experience now the first pangs of that sorrow Jacqueline had vividly portrayed as the love-portion of Marot and Caillette? Faintly the ivy whispered above the princess, telling perhaps of other days when, centuries gone by, some Norman lady had been wooed and won, or wooed and lost, in the shadow of the griffin, which, silent, sphinx-like, yet endured through the ages.

Idly the Princess Louise plucked a leaf from the old, old vine, picked it apart and let the pieces float away. As they fluttered and fell at the jester's feet she regarded him with thoughtful blue eyes.

"How far is it," she asked, "to the duke's principality?"

If he had doubted the maid's story, he was now convinced. The ring and her question confirmed Jacqueline's narrative. Moodily he surveyed the great claws of the griffin, firmly planted on the earth, and then looked from the feet to the laughing mouth of the stone figure, or so much of it as the shining dress left uncovered.

"About fifteen days' journey, Princess," he replied.

"No farther?"

"Barring accidents, it may be made in that time."

She did not notice how dull was his tone; how he avoided her gaze. Blind to him, she turned the ring around and around on her finger, as though her thoughts were concentrated on it.

"Accidents," she repeated, her hand now motionless. "Is the way perilous?"

"The country is most unsettled."

"What do you mean by unsettled?" she continued, bending forward with fingers clasped over her knees. Supinely she waved a foot back and forth, showing and then withdrawing the point of a jeweled slipper, and a suggestion of lavender in silk network above. "What do you call unsettled?"

"The country is infested with many roving bands commanded by the so-called independent barons who owe allegiance to neither king nor emperor," he answered. "Their homes are perched, like eagles' nests, upon some mountain peak that commands the valleys travelers must proceed through. A fierce, untamed crew, bent on rapine and murder!"

"Did you encounter any such?" Gently.

"Ofttimes."

"And left unscathed?"

"Because I was a jester, Madam; something less than man; a lordling's slave; a woman's plaything! Their sentinels shared with me their flasks; I slept before their signal fires, and even supped in the heart of their stone fastnesses. Fools and monks are safe among them, for the one amuses and the other absolves their sins. Yet is there one free baron," he added reflectively, "whom even I should have done well to avoid; he, the most feared, the most savage! Louis, the bastard of Pfalz-Urfeld!"

"Have you ever met him?" asked the princess, in a mechanical tone.

"No," with a short laugh. "A few of his knaves I encountered, however, whose conduct shamed the courtesy of the other mountain rogues. I all but fared ill indeed, from them. To the pleasantry of my greeting, they replied with the true pilferer's humor; the free baron had ordered every one searched. They would have robbed and stripped me, despite the color of my coat, only fortunately, instead of a fool's staff, I had a good blade of the duke's. For a moment it was cut and thrust—not jest and gibe; the suddenness of the attack surprised them, and before they could digest the humor of it the fool had slipped away."

She leaned inertly back against the soft cushion of ivy. In the shadow the tint on her cheeks deepened, but below the sunlight played about her shoulders through leafy interspace, or crept in dancing spots down over her gown and arms.

"The duke would not be molested by these outlaws?" she continued, pursuing her line of questioning.

"The duke has a strong arm," he answered cautiously. "They may be well content to permit him to come and go as he sees fit."

"Well, well," she said, perversely, "I was only curious about the distance and the country."

"For leagues the land is wild, bleak, inhospitable, and then 'tis level, monotonous, deserted, so lonely the song dies on the wandering minstrel's lips. But the duke rides fast with his troop and soon would cover the mountain paths and dreary wastes."

"Nay," she interrupted impatiently, "I asked not how the duke would ride."

"I thought you wished to know, Princess," he replied, humbly.

"You thought"—she began angrily, sitting erect.

"I know, Princess; a fool should but jest, not think."

"Why do you cross me to-day?" she demanded petulantly. "Can you not see—"

Abruptly she rose; impatiently moved away; but a few steps, however, when she turned, her face suddenly free from annoyance, in her eyes a soft decision.

"There!" she exclaimed with a smile, half-arch, half-repentant. "How can any one be angry on such a day—all sunshine, butterflies and flowers!"

He did not reply, and, mistress once more of herself, she drew near.

"What a contrast to the stuffy palace, with all the courtiers, ministers and lap-dogs!" she went on. "Here one can breathe. But how shall we make the most of such a day? Stroll into the forest; sit by the fountain; run over the grass?"

Her voice was softer than it had been; her words fraught with suggestions of exhilarating companionship. Did she note their effect? At any rate, she laughed lightly.

"But how," she resumed, surveying the great enfolding skirt, "could one trip the sward with this monstrous gown, weighted with wreaths of silver? Is it not but one of the many penalties of high birth? Oh, for the short skirts of the lowly! What comfort to be arrayed like Jacqueline!"

"And she, Princess, doubtless thinks likewise of more gorgeous apparel." His heart beat faster as he strove to answer her in kind.

"A waste of cloth in vanity, as saith Master Calvin!" she replied, lifting her arms that shone with creamy softness from the dangling folds of heavy silk. "Were it not for this courtly encumbrance, I should propose going into the fields with the haymakers. You may see them now—look!—through the opening in the foliage."

With an expression, part resignation, part regret, she leaned against the wind-worn griffin which formed the arm of the bench. Fainter sounded the warning of the jestress in the ears of the duke's fool; so faint it became but a weak admonition. More and more he abandoned himself to the pleasure of the moment.

"To make the most of the day," the princess had said.

How? By denying himself the sight of her ever-varying grace; by refusing to yield to the charm of her voice. He raised his head more boldly; through her drooping lashes a lazy light shot forth upon him, and the shadow of a smile seemed to say: "That is better. When the mistress is indulgent, a fool should not be unbending. A melancholy jester is but poor company."

And so her mood swayed his; he forgot his resolution, his pride, and yielded to the infatuation of the moment. But when he endeavored to call the weapons of his office to his aid, her glance and the shadow of that smile left him witless. Jest, fancy and whim had taken flight.

"Well?" she said. "Well, Sir Fool?"

His color shifted; withal his half-embarrassment, there was something graceful and noble in his bearing.

"Madam"—he began, and stopped for want of matter to put into words.

But if the princess was annoyed at the new-found dullness of her plaisant, her manner did not show it.

"What," she said, gently; "no news from the court; no word of intrigue; no story of the king? I should seek a courtier for my companion, not a jester. But there! What book have you brought?" indicating the volume that lay upon the bench.

"Guillaume de Lorris's 'Romance of the Rose,'" he answered, more freely.

"Where did we leave off?"

"Where the hero, arriving at a fountain, beheld a beautiful rose tree," said the fool in a low tone. "Desiring the rose, he reached to gather it—"

"Yes, I remember. And then, Reason and Danger did battle with Love."

"Is it your wish we continue?" he asked, taking the book in his hand.

"I would fain learn if he gathers his rose. Nay, sit here on the bench and I"—brightly—"may look over your shoulder ever and anon, to steal a glimpse of the pretty pictures."

Unquestioningly, he obeyed her, the book, illumined, gleaming in the sunshine; the letters, red, gold, many-hued, dancing before them. Love in crimson, the five silver shafts of Cupid, the Tower of Jealousy, a frowning fortress, the Rose, incentive for endless striving and endeavor—all floated by on the creamy parchment leaves. So interested was she in these wondrous pages, executed with such precision and perfection, with marginal adornment, and many a graceful turn and fancy in initial letter and tail-piece, she seemed to him for the moment rather some simple lowly maiden than a proud princess of the realm.

"How much splendor the penman has shown!" she murmured, her breath on his cheek. "'Tis more beautiful than the 'Life of Saint Agnes.' Is not that figure well done? A hard, austere old man; Reason, I believe, in monkish attire."

"Reason, or Duty, ever partakes of the monastery," he retorted with a short, mirthless laugh.

"Duty; obedience!" she broke in. "Do I not know them? Please turn the page."

Reaching over, she herself did so, her fingers touching his, her bosom just brushing his shoulder; and then she flushed, for it was Venus's self the page revealed, standing on a grassy bank and showing Love the rose. Around the queen of beauty floated a silver gauze; her hair was indicated by threads of gold tossed luxuriantly about her; upon the shoulder of Love rested her hand, encouraging him in his quest. Most zealously had the monk-artist executed the lovely lady, as though some heart-dream flowed from the ink on his pen, every line exact, each feature radiantly shown. Some youthful anchorite, perhaps, was he, and this the fair temptation that had assailed his fancy; such a vision as St. Anthony wrestled with in the grievous solitude of his hermit cell.

From the book and the picture, the jester, feeling the princess draw back impulsively, dared look up, and, looking up, could not look down from a loveliness surpassing the idealization on vellum of a monkish dream. From head to foot, the sunlight bathed the princess, glistening in her hair until it was alive with light. Even when he gazed into her blue eyes he was conscious of a more flaming glory than lay in the heavens of their depths; a splendent maze that shed a brightness around her.

"Oh, Princess," he said, wildly, "I know what the king hath told you! Why you wear the monarch's ring!"

"The monarch's ring!" she repeated, as recalled suddenly from wandering thought. "Why—how know you—ah, Jacqueline—"

"And a ring signifieth consent. You will fulfill the king's desire?"

"The king's desire?" she replied, mechanically. "Is it not the will of God?"

"But your own heart?" he cried, holding her with his eager gaze.

She laid her hand on his shoulder; her eyes answered his. Did she not realize the tragedy the future held for him? Or did to-morrow seem far off, and the present become her greater concern? Was hers the philosophy of Marguerite's code which taught that the sweets of admiration should be gathered on the moment? That a cry of pain from a worshiping heart, however lowly, was honeyed flattery to Love's votaries? As the jester looked at her a sudden chill seized his breast. Jacqueline's mocking laughter rang in his ears. "Ask her the rest yourself, most Unsophisticated Fool!"

"Then you will obey the king?" he persisted, dully.

"Why," she answered, smiling and bending nearer, "will you spoil the day?"

"You would give yourself to a man, whether or not you loved him?"

A frown gathered on the princess' brow, but she stooped, herself picked up the book he had dropped, brushed the earth from it and seated herself upon the bench. Her manner was quiet, resolute; her action, a rebuke to the forward fool.

"Will you not read?" she said, with an inscrutable look.

"True," he exclaimed, rising quickly, "I was sent to amuse—"

"And you have found me a too exacting mistress?" she asked, more gently, checking the implied reproach.

"Exacting!" he repeated.

"What then?" she said, half sadly.

"Nothing," he answered.

But in his mind Jacqueline's scornful words reiterated themselves: "Think you the princess will wear the willow?"

Taking the book, he opened it at random, mechanically sinking at her feet. The quest, the idle quest! Was it but an awakening? So far lay the branch above his reach! His voice rose and fell with the mystic rhythm of the meter, now dwelling on death and danger, the shortness of life, the sweetness of passion; then telling the pleasures of the dance.

Lower fell the princess' hand until it touched the reader's head; touched and lingered. Before the fool's eyes the letters of the book became blurred and then faded away. Doubt, misgiving, fear, vanished on the moment. The flower she had given him seemed to burn on his heart. He forgot the decree of the king; her equivocation; the unanswered question. Passionately he thrust his hand into his doublet.

"The rose and love are one," he cried. "The rose is—"

"Pardon me, Madam," said a voice, and Jacqueline, clear-eyed, calm, stood before them; "the fan was not in the king's ante-chamber, or I should have been here sooner. I trust you have not been put out for want of it?"

"Not at all, Jacqueline," returned her mistress, with a natural, tranquil movement, "although"—sharply—"you were gone longer than you should have been!"

Proficient as a poet, bold as a soldier, adroit as a statesman, the king was, nevertheless, most fitted for the convivial role of host, and no part that he played in his varied repertoire afforded such opportunity for the nice display of his unusual talents. History hath sneered at his rhymes as flat, stale and unprofitable; upon the bloody field he had been defeated and subsequently imprisoned; clever in diplomacy, the sagacity of his opponent, Charles, had in truth overmatched him; yet as the ostentatious Boniface, in grand bib and tucker, prodigal in joviality and good-fellowship, his reputation rests without a flaw.

In anticipation of the arrival of the duke and his suite, the monarch had ordered a series of festivities and entertainments such as would gratify his desire for pageantry and display, and at the same time do honor to a guest who was to espouse one of France's fairest wards. To the castle repaired tailors, embroiderers and goldsmiths to make and devise garments for knights, ladies, lords and esquires and for the trapping, decking and adorning of coursers, jennets and palfries. Bales of silks and satins had been long since conveyed thither from distant Paris, in anticipation of the coming marriage; and the old Norman castle that had once resounded with the clashing of arms, the snap of the cross-bow and the clang of the catapult now echoed with the merry stir and flurry of peace; a bee-hive of activity wherein were no drones; marshal, grand master, chancellor and grand chamberlain preparing for mysteries and hunting parties; dowagers, matrons and maids making ready for balls and other pastimes.

With this new influx of population to the pleasure palace came a plentiful sprinkling of wayside minstrels, jugglers, mountebanks, dulcimer and lute players, street poets who sang the praises of some fair cobbleress or pretty sausage girl; scamps of students from the Paris haunts of vice, loose fellows who conned the classical poets by day and took a purse by night; dancers, dwarfs, and merry men all, not averse to—

"Haunch and ham, and cheek and chine

While they gurgled their throats with right good wine."

Here sauntered a wit-cracker, a peacock feather in his hand, arm-in-arm with an impoverished "banquet beagle," or "feast hound;" there passed a jack in green, a bladder under his arm and a tankard at his belt, with which latter he begged that sort of alms that flows from a spigot. As vagrant followers hover on the verge of a camp, or watchful vultures circle around their prey, so these lower parasites (distinct from the other well-born, more aristocratic genus of smell-feast) prowled vigilantly without the castle walls and beyond the limits of the royal pleasure grounds, finding occasional employment from lackey, valet or equerry, who, imitating their betters, amused themselves betimes with some low buffoon or vulgar clown and rewarded him for his gross stories and antics with a crust and a cup.

Faith, in those thrice happy days, every henchman could whistle to him his shabby poet, and every ostler hold court in the stable, with a visdase, or ass face, to keep the audience in a roar, and a nimble-footed trull to set them into ecstasies. But woe betide the honest wayfarer who strolled beyond the orderly precincts of the king's walls after dusk; for if some street coxcomb was too drunk to rob him, or a ribald Latin scholar saw him not, he surely ran into a nest of pavement tumblers or cellar poets who forthwith stripped him and turned him loose in the all-insufficient garb of nature.

A fantastic, waggish crew—yet Francis minded them not, so long as they observed sufficient etiquette to keep their distance from his royal person and immediate following. This nice decorum, however, be it said, was an unwritten law with these waifs and scatterlings, knowing the merry monarch who tolerated them afar would feel no compunction at hanging them severally, or in squads, from the convenient branches of the trees surrounding the castle, should the humor seize him that such summary chastisement were best for their morals and the welfare of the community. Thus, though bold, were they also shy, drinking humbly from a black-jack quart in the kitchen and vanishing docilely enough when the sovereign cook bid them be gone with warm words or by flinging over them ladles of hot soup.