The Project Gutenberg EBook of Gaspar the Gaucho, by Mayne Reid

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Gaspar the Gaucho

A Story of the Gran Chaco

Author: Mayne Reid

Illustrator: F.C. Tilney

Release Date: November 28, 2007 [EBook #23648]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GASPAR THE GAUCHO ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Captain Mayne Reid

"Gaspar the Gaucho"

Chapter One.

The Gran Chaco.

Spread before you a map of South America. Fix your eye on the point of confluence between two of its great rivers—the Salado, which runs south-easterly from the Andes mountains, and the Parana coming from the north; carry your glance up the former to the town of Salta, in the ancient province of Tucuman; do likewise with the latter to the point where it espouses the Paraguay; then up this to the Brazilian frontier fort of Coimbra; finally draw a line from the fort to the aforementioned town—a line slightly curved with its convexity towards the Cordillera of the Andes—and you will thus have traced a boundary embracing one of the least known, yet most interesting, tracts of territory in either continent of America, or, for that matter, in the world. Within the limits detailed lies a region romantic in its past as mysterious in its present; at this hour almost as much a terra incognita as when the boats of Mendoza vainly endeavoured to reach it from the Atlantic side, and the gold-seekers of Pizarro’s following alike unsuccessfully attempted its exploration from the Pacific. Young reader, you will be longing to know the name of this remarkable region; know it, then, as the “Gran Chaco.”

No doubt you may have heard of it before, and, if a diligent student of geography, made some acquaintance with its character. But your knowledge of it must needs be limited, even though it were as extensive as that possessed by the people who dwell upon its borders; for to them the Gran Chaco is a thing of fear, and their intercourse with it one which has brought them, and still brings, only suffering and sorrow.

It has been generally supposed that the Spaniards of Columbus’s time subdued the entire territory of America, and held sway over its red-skinned aborigines. This is a historical misconception. Although lured by a love of gold, conjoined with a spirit of religious propagandism, the so-called Conquistadores overran a large portion of both divisions of the continent, there were yet extensive tracts of each never entered, much less colonised, by them—territories many times larger than England, in which they never dared set foot. Of such were Navajoa in the north, the country of the gallant Goajiros in the centre, the lands of Patagonia and Arauco in the south, and notably the territory lying between the Cordilleras of the Peruvian Andes and the rivers Parana and Paraguay, designated “El Gran Chaco.”

This vast expanse of champaign, large enough for an empire, remains to the present time not only uncolonised, but absolutely unexplored. For the half-dozen expeditions that have attempted its exploration, timidly entering and as hastily abandoning it, scarce merit consideration.

And equally unsuccessful have been all efforts at religious propagandism within its borders. The labours of the padres, both Jesuit and Franciscan, have alike signally failed; the savages of the Chaco refusing obedience to the cross as submission to the sword.

Three large rivers—the Salado, Vermejo, and Pilcomayo—course through the territory of the Chaco; the first forming its southern boundary, the others intersecting it. They all take their rise in the Andes Mountains, and after running for over a thousand miles in a south-easterly direction and nearly parallel courses, mingle their waters with those of the Parana and Paraguay. Very little is known of these three great streams, though of late years the Salado has received some exploration. There is a better acquaintance with its upper portion, where it passes through the settled districts of Santiago and Tucuman. Below, even to the point where it enters the Parana, only a strong military expedition may with safety approach its banks, by reason of their being also traversed by predatory bands of the savages.

Geographical knowledge of the Vermejo is still less, and of the Pilcomayo least of all; this confined to the territory of their upper waters, long since colonised by the Argentine States and the Republic of Bolivia, and now having many towns in it. But below, as with the Salado, where these rivers enter the region of the Chaco, they become as if they were lost to the geographer; even the mouth of the Pilcomayo not being known for certain, though one branch of it debouches into the Paraguay, opposite the town of Assuncion, the capital of Paraguay itself! It enters the river of this name by a forked or deltoid channel, its waters making their way through a marshy tract of country in numerous slow flowing riachos, whose banks, thickly overgrown with a lush sedgy vegetation, are almost concealed from the eye of the explorer.

Although the known mouth of the Pilcomayo is almost within gun-shot of Assuncion—the oldest Spanish settlement in this part of South America—no Paraguayan ever thinks of attempting its ascent, and the people of the town are as ignorant of the land lying along that river’s shores as on the day when the old naturalist, Azara, paddles his periagua some forty miles against its obstructing current. No scheme of colonisation has ever been designed or thought of by them; for it is only near its source, as we have seen, that settlements exist. In the Chaco no white man’s town ever stood upon its banks, nor church spire flung shadow athwart its unfurrowed waves.

It may be asked why this neglect of a territory, which would seem so tempting to the colonist? For the Gran Chaco is no sterile tract, like most parts of the Navajo country in the north, or the plains of Patagonia and the sierras of Arauco in the south. Nor is it a humid, impervious forest, at seasons inundated, as with some portions of the Amazon valley and the deltas of the Orinoco.

Instead, what we do certainly know of the Chaco shows it the very country to invite colonisation; having every quality and feature to attract the settler in search of a new home. Vast verdant savannas—natural clearings—rich in nutritious grasses, and groves of tropical trees, with the palm predominating; a climate of unquestionable salubrity, and a soil capable of yielding every requisite for man’s sustenance as the luxury of life. In very truth, the Chaco may be likened to a vast park or grand landscape garden, still under the culture of the Creator!

But why not also submitted to the tillage of man? The answer is easy: because the men who now hold it will not permit intrusion on their domain—to them hereditary—and they are hunters, not agriculturists. It is still in the possession of its red-skinned owners, the original lords of its soil, these warlike Indians, who have hitherto defied all attempts to enslave or subdue them, whether made by soldier, miner, or missionary. These independent savages, mounted upon fleet steeds, which they manage with the skill of Centaurs, scour the plains of the Chaco, swift as birds upon the wing. Disdaining fixed residence, they roam over its verdant pastures and through its perfumed groves, as bees from flower to flower, pitching their toldos, and making camp in whatever pleasant spot may tempt them. Savages though called, who would not envy them such a charming insouciant existence? Do not you, young reader?

I anticipate your answer, “Yes.” Come with me, then! Let us enter the “Gran Chaco,” and for a time partake of it!

Chapter Two.

Paraguay’s despot.

Notwithstanding what I have said of the Chaco remaining uncolonised and unexplored, I can tell of an exception. In the year 1836, one ascending the Pilcomayo to a point about a hundred miles from its mouth, would there see a house, which could have been built only by a white man, or one versed in the ways of civilisation. Not that there was anything very imposing in its architecture; for it was but a wooden structure, the walls of bamboo, and the roof a thatch of the palm called cuberta—so named from the use made of its fronds in covering sheds and houses. But the superior size of this dwelling, far exceeding that of the simple toldos of the Chaco Indians; its ample verandah pillared and shaded by a protecting roof of the same palm leaves; and, above all, several well-fenced enclosures around it, one of them containing a number of tame cattle, others under tillage—with maize, manioc, the plantain, and similar tropical products—all these insignia evinced the care and cultivating hand of some one else than an aboriginal.

Entering the house, still further evidence of the white man’s presence would be observed. Furniture, apparently home-made, yet neat, pretty, and suitable; chairs and settees of the caña brava, or South American bamboo; bedsteads of the same, with beds of the elastic Spanish moss, and ponchos for coverlets; mats woven from fibres of another species of palm, with here and there a swung hammock. In addition, some books and pictures that appeared to have been painted on the spot; a bound volume of music, with a violin and guitar—all speaking of a domestic economy unknown to the American Indian.

In some of the rooms, as also in the outside verandah, could be noticed objects equally unlike the belongings of the aboriginal: stuffed skins of wild beasts and birds; insects impaled on strips of palm bark; moths, butterflies, and brilliant scarabaei; reptiles preserved in all their repulsive ugliness, with specimens of ornamental woods, plants, and minerals; a singular paraphernalia, evidently the product of the region around. Such a collection could only belong to a naturalist, and that naturalist could be no other than a white man. He was; his name Ludwig Halberger.

The name plainly speaks his nationality—a German. And such was he; a native of the then kingdom of Prussia, born in the city of Berlin.

Though not strange his being a naturalist—since the taste for and study of Nature are notably peculiar to the German people—it was strange to find Prussian or other European having his home in such an out-of-the-way place. There was no civilised settlement, no other white man’s dwelling, nearer than the town of Assuncion; this quite a hundred miles off, to the eastward. And north, south, and west the same for more than five times the distance. All the territory around and between, a wilderness, unsettled, unexplored, traversed only by the original lords of the soil, the Chaco Indians, who, as said, have preserved a deadly hostility to the paleface, ever since the keels of the latter first cleft the waters of the Parana.

To explain, then, how Ludwig Halberger came to be domiciled there, so far from civilisation, and so high up the Pilcomayo—river of mysterious note—it is necessary to give some details of his life antecedent to the time of his having established this solitary estancia. To do so a name of evil augury and ill repute must needs be introduced—that of Dr Francia, Dictator of Paraguay, who for more than a quarter of a century ruled that fair land verily with a rod of iron. With this same demon-like tyrant, and the same almost heavenly country, is associated another name, and a reputation as unlike that of José Francia as Hyperion to the Satyr, and which justice to a godlike humanity forbids me to pass over in silence. I speak of Amadé, or, as he is better known, Aimé Bonpland—cognomen appropriate to this most estimable man—known to all the world as the friend and fellow-traveller of Humboldt; more still, his assistant and collaborates in those scientific researches, as yet unequalled for truthfulness and extent—the originator and discoverer of much of that learned lore, which, with modesty unparalleled, he has allowed his more energetic and more ambitious compagnon de voyage to have credit for.

Though no name sounds more agreeably to my ears than that of Aimé Bonpland, I cannot here dwell upon it, nor write his biography, however congenial the theme. Some one who reads this may find the task both pleasant and profitable; for though his bones slumber obscurely on the banks of the Parana, amidst the scenes so loved by him, his name will one day have a higher niche in Fame’s temple than it has hitherto held—perhaps not much lower than that of Humboldt himself. I here introduce it, with some incidents of his life, as affecting the first character who figures in this my tale. But for Aimé Bonpland, Ludwig Halberger might never have sought a South American home. It was in following the example of the French philosopher, of whom he had admiringly read, that the Prussian naturalist made his way to the La Plata and up to Paraguay, where Bonpland had preceded him. But first to give the adventures of the latter in that picturesque land, of which a short account will suffice; then afterwards to the incidents of my story.

Retiring from the busy world, of which he seems to have been somewhat weary, Bonpland took up his residence on the banks of the Rio Parana; not in Paraguayan territory, but that of the Argentine Republic, on the opposite side of the river. There settled down, he did not give his hours to idleness; nor yet altogether to his favourite pursuit, the pleasant though somewhat profitless one of natural history. Instead, he devoted himself to cultivation, the chief object of his culture being the “yerba de Paraguay,” which yields the well-known maté, or Paraguayan tea. In this industry he was eminently successful. His amiable manners and inoffensive character attracted the notice of his neighbours, the Guarani Indians—a peaceful tribe of proletarian habits—and soon a colony of these collected around him, entering his employ, and assisting him in the establishment of an extensive “yerbale,” or tea-plantation, which bid fair to become profitable.

The Frenchman was on the high-road to fortune, when a cloud appeared, coming from an unexpected quarter of the sky—the north. The report of his prosperity had reached the ears of Francia, Paraguay’s then despot and dictator, who, with other strange theories of government, held the doctrine that the cultivation of “yerba” was a right exclusively Paraguayan—in other words, belonging solely to himself. True, the French colonist, his rival cultivator, was not within his jurisdiction, but in the state of Corrientes, and the territory of the Argentine Confederation. Not much, that, to Dr Francia, accustomed to make light of international law, unless it were supported by national strength and backed by hostile bayonets. At the time Corrientes had neither of these to deter him, and in the dead hour of a certain night, four hundred of his myrmidons—the noted quarteleros—crossed the Parana, attacked the tea-plantation of Bonpland, and after making massacre of a half-score of his Guarani peons, carried himself a prisoner to the capital of Paraguay.

The Argentine Government, weak with its own intestine strife, submitted to the insult almost unprotestingly. Bonpland was but a Frenchman and foreigner; and for nine long years was he held captive in Paraguay. Even the English charge d’affaires, and a Commission sent thither by the Institute of France, failed to get him free! Had he been a lordling, or some little viscomte, his forced residence in Paraguay would have been of shorter duration. An army would have been despatched to “extradite” him. But Aimé Bonpland was only a student of Nature—one of those unpretending men who give the world all the knowledge it has, worth having—and so was he left to languish in captivity. True, his imprisonment was not a very harsh one, and rather partook of the character of parole d’honneur. Francia was aware of his wonderful knowledge, and availed himself of it, allowing his captive to live unmolested. But again the amiable character of the Frenchman had an influence on his life, this time adversely. Winning for him universal respect among the simple Paraguayans, it excited the envy of their vile ruler; who once again, and at night, had his involuntary guest seized upon, carried beyond the confines of his territory, and landed upon Argentine soil—but stripped of everything save the clothes on his back!

Soon after, Bonpland settled near the town of Corrientes, where, safe from further persecution, he once more entered upon agricultural pursuits. And there, in the companionship of a South American lady—his wife—with a family of happy children, he ended a life that had lasted for fourscore years, innocent and unblemished, is it had been useful, heroic, and glorious.

Chapter Three.

The Hunter-Naturalist.

In some respects similar to the experience of Aimé Bonpland was that of Ludwig Halberger. Like the former, an ardent lover of Nature, as also an accomplished naturalist, he too had selected South America as the scene of his favourite pursuits. On the great river Parana—better, though erroneously, known to Europeans as the La Plata—he would find an almost untrodden field. For although the Spanish naturalist, Azara, had there preceded him, the researches of the latter were of the olden time, and crude imperfect kind, before either zoology or botany had developed themselves into a science.

Besides, the Prussian was moderately fond of the chase, and to such a man the great pampas region, with its pumas and jaguars, its ostriches, wild horses, and grand guazuti stags, offered an irresistible attraction. There he could not only indulge his natural taste, but luxuriate in them.

He, too, had resided nine years in Paraguay, and something more. But, unlike Bonpland, his residence there was voluntary. Nor did he live alone. Lover of Nature though he was, and addicted to the chase, another kind of love found its way to his heart, making himself a captive. The dark eyes of a Paraguayan girl penetrated his breast, seeming brighter to him than the plumage of the gaudiest birds, or the wings of the most beautiful butterflies.

“El Gilero” the blonde—as these swarthy complexioned people were wont to call the Teutonic stranger—found favour in the eyes of the young Paraguayense, who reciprocating his honest love, consented to become his wife; and became it. She was married at the age of fourteen, he being over twenty.

“So young for a bride!” many of my readers will exclaim. But that is rather a question of race and climate. In Spanish America, land of feminine precocity, there is many a wife and mother not yet entered on her teens!

For nigh ten years Halberger lived happily with his youthful esposa; all the happier that in due time a son and daughter—the former resembling himself, the latter a very image of her mother—enlivened their home with sweet infantine prattle. And as the years rolled by, a third youngster came to form part of the family circle—this neither son nor daughter, but an orphan child of the Señora’s sister deceased. A boy he was, by name Cypriano.

The home of the hunter-naturalist was not in Assuncion, but some twenty miles out in the “campo.” He rarely visited the capital, except on matters of business. For a business he had; this of somewhat unusual character. It consisted chiefly in the produce of his gun and insect-net. Many a rare specimen of bird and quadruped, butterfly and beetle, captured and preserved by Ludwig Halberger, at this day adorns the public museums of Prussia and other European countries. But for the dispatch and shipment of these he would never have cared to show himself in the streets of Assuncion; for, like all true naturalists, he had no affection for city life. Assuncion, however, being the only shipping port in Paraguay, he had no choice but repair thither whenever his collections became large enough to call for exportation.

Beginning life in South America with moderate means, the Prussian naturalist had prospered: so much, as to have a handsome house, with a tract of land attached, and a fair retinue of servants; these last, all “Guanos,” a tribe of Indians long since tamed and domesticated. He had been fortunate, also, in securing the services of a gaucho, named Gaspar, a faithful fellow, skilled in many callings, who acted as his mayor-domo and man of confidence.

In truth, was Ludwig Halberger in the enjoyment of a happy existence, and eminently prosperous. Like Aimé Bonpland, he was fairly on the road to fortune; when, just as with the latter, a cloud overshadowed his life, coming from the self-same quarter. His wife, lovely at fourteen, was still beautiful at twenty-four, so much as to attract the notice of Paraguay’s Dictator. And with Dr Francia to covet was to possess, where the thing coveted belonged to any of his own subjects. Aware of this, warned also of Francia’s partiality by frequent visits with which the latter now deigned to honour him, Ludwig Halberger saw there was no chance to escape domestic ruin, but by getting clear out of the country. It was not that he doubted the fidelity of his wife; on the contrary, he knew her to be true as she was beautiful. How could he doubt it, since it was from her own lips he first learnt of the impending danger?

Away from Paraguay, then—away anywhere—was his first and quickly-formed resolution, backed by the counsels of his loyal partner in life. But the design was easier than its execution; the last not only difficult, but to all appearance impossible. For it so chanced that one of the laws of that exclusive land—an edict of the Dictator himself—was to the point prohibitive; forbidding any foreigner who married a native woman to take her out of the country, without having a written permission from the Executive Head of the State. Ludwig Halberger was a foreigner, his wife native born, and the Head of the State Executive, as in every other sense, was José Gaspar Francia!

The case was conclusive. For the Prussian to have sought permission to depart, taking his wife along with him, would have been more than folly—madness—hastening the very danger he dreaded.

Flight, then? But whither, and in what direction? To flee into the Paraguayan forests could not avail him, or only for a short respite. These, traversed by the cascarilleros and gatherers of yerba, all in the Dictator’s employ and pay, would be no safer than the streets of Assuncion itself. A party of fugitives, such as the naturalist and his family, could not long escape observation; and seen, they would as surely be captured and carried back. The more surely from the fact that the whole system of Paraguayan polity under Dr Francia’s régime was one of treachery and espionage, every individual in the land finding it to his profit to do dirty service for “El Supremo”—as they styled their despotic chief.

On the other side there was the river, but still more difficult would it be to make escape in that direction. All along its bank, to the point where it enters the Argentine territory, had Francia established his military stations, styled guardias, where sentinels kept watch at all hours, by night as in the day. For a boat to pass down, even the smallest skiff, without being observed by some of these Argus-eyed videttes, would have been absolutely impossible; and if seen as surely brought to a stop, and taken back to Assuncion.

Revolving all these difficulties in his mind, Ludwig Halberger was filled with dismay, and for a long time kept in a state of doubt and chilling despair. At length, however, a thought came to relieve him—a plan of flight, which promised to have a successful issue. He would flee into the Chaco!

To the mind of any other man in Paraguay the idea would have appeared preposterous. If Francia resembled the frying-pan, the Chaco to a Paraguayan seemed the fire itself. A citizen of Assuncion would no more dare to set foot on the further side of that stream which swept the very walls of his town, than would a besieging soldier on the glacis of the fortress he besieged. The life of a white man caught straying in the territory of “El Gran Chaco” would not have been worth a withey. If not at once impaled on an Indian spear held in the hand of “Tova” or “Guaycuru,” he would be carried into a captivity little preferable to death.

For all this, Ludwig Halberger had no fear of crossing over to the Chaco side, nor penetrating into its interior. He had often gone thither on botanising and hunting expeditions. But for this apparent recklessness he had a reason, which must needs here be given. Between the Chaco savages and the Paraguayan people there had been intervals of peace—tiempos de paz—during which occurred amicable intercourse; the Indians rowing over the river and entering the town to traffic off their skins, ostrich feathers, and other commodities. On one of these occasions the head chief of the Tovas tribe, by name Naraguana, having imbibed too freely of guarapé, and in some way got separated from his people, became the butt of some Paraguayan boys, who were behaving towards him just as the idle lads of London or the gamins of Paris would to one appearing intoxicated in the streets. The Prussian naturalist chanced to be passing at the time; and seeing the Indian, an aged man, thus insulted, took pity upon and rescued him from his tormentors.

Recovering from his debauch, and conscious of the service the stranger had done him, the Tovas chief swore eternal friendship to his generous protector, at the same time proffering him the “freedom of the Chaco.”

The incident, however, caused a rupture between the Tovas tribe and the Paraguayan Government, terminating the tiempo de paz, which had not since been renewed. More unsafe than ever would it have been for a Paraguayan to set foot on the western side of the river. But Ludwig Halberger knew that the prohibition did not extend to him; and relying on Naraguana’s proffered friendship, he now determined upon retreating into the Chaco, and claiming the protection of the Tovas chief.

Luckily, his house was not a great way from the river’s bank, and in the dead hour of a dark night, accompanied by wife and children—taking along also his Guano servants, with such of his household effects as could be conveniently carried, the faithful Caspar guiding and managing all—he was rowed across the Paraguay and up the Pilcomayo. He had been told that at some thirty leagues from the mouth of the latter stream, was the tolderia of the Tovas Indians. And truly told; since before sunset of the second day he succeeded in reaching it, there to be received amicably, as he had anticipated. Not only did Naraguana give him a warm welcome but assistance in the erection of his dwelling; afterwards stocking his estancia with horses and cattle caught on the surrounding plains. These tamed and domesticated, with their progeny, are what anyone would have seen in his corrals in the year 1836, at the time the action of our tale commences.

Chapter Four.

His Nearest Neighbours.

The house of the hunter-naturalist was placed at some distance from the river’s bank, its site chosen with an eye to the picturesque; and no lovelier landscape ever lay before the windows of a dwelling. From its front ones—or, better still, the verandah outside them—the eye commands a view alone limited by the power of vision: verdant savannas, mottled with copses of acacia and groves of palm, with here and there single trees of the latter standing solitary, their smooth stems and gracefully-curving fronds cut clear as cameos against the azure sky. Nor is it a dead level plain, as pampas and prairies are erroneously supposed always to be. Instead, its surface is varied with undulations; not abrupt as the ordinary hill and dale scenery, but gently swelling like the ocean’s waves when these have become crestless after the subsidence of a storm.

Looking across this champaign from Halberger’s house at almost any hour of the day, one would rarely fail to observe living creatures moving upon it. It may be a herd of the great guazuti deer, or the smaller pampas roe, or, perchance, a flock of rheas—the South American ostrich—stalking along tranquilly or in flight, with their long necks extended far before, and their plumed tails streaming train-like behind them. Possibly they may have been affrighted by the tawny puma, or spotted jaguar, seen skulking through the long pampas grass like gigantic cats. A drove of wild horses, too, may go careering past, with manes and tails showing a wealth of hair which shears have never touched; now galloping up the acclivity of a ridge; anon disappearing over its crest to re-appear on one farther off and of greater elevation. Verily, a scene of Nature in its wildest and most interesting aspect!

Upon that same plain, Ludwig Halberger and his people are accustomed to see others than wild horses—some with men upon their backs, who sit them as firmly as riders in the ring; that is, when they do sit them, which is not always. Often may they be seen standing erect upon their steeds, these going in full gallop! True, your ring-rider can do the same; but then his horse gallops in a circle, which makes it a mere feat of centrifugal and centripetal balancing. Let him try it in a straight line, and he would drop off like a ripe pear from the tree. No curving course needs the Chaco Indian, no saddle nor padded platform on the back of his horse, which he can ride standing almost as well as seated. No wonder, then, these savages—if savages they may be called—have obtained the fanciful designation of centaurs—the “Red Centaurs of the Chaco.”

Those seen by Ludwig Halberger and his family are the “Tovas,” already introduced. Their village, termed tolderia, is about ten miles off, up the river. Naraguana wished the white man to have fixed his residence nearer to him, but the naturalist knew that would not answer. Less than two leagues from an Indian encampment, and still more if a permanent dwelling-place, which this tolderia is, would make the pursuit of his calling something more than precarious. The wild birds and beasts—in short, all the animated creation—dislike the proximity of the Indian, and flee his presence afar.

It may seem strange that the naturalist still continues to form collections, so far from any place where he might hope to dispose of them. Down the Pilcomayo he dares not take them, as that would only bring him back to the Paraguay river, interdict to navigation, as ever jealously guarded, and, above all, tabooed to himself. But he has no thought, or intention, to attempt communicating with the civilised world in that way; while a design of doing so in quite another direction has occurred to him, and, in truth, been already all arranged. This, to carry his commodities overland to the Rio Vermejo, and down that stream till near its mouth; then again overland, and across the Parana to Corrientes. There he will find a shipping port in direct commerce with Buenos Ayres, and so beyond the jurisdiction of Paraguay’s Dictator.

Naraguana has promised him not only an escort of his best braves, but a band of cargadores (carriers) for the transport of his freight; these last the slaves of his tribe. For the aristocratic Tovas Indians have their bondsmen, just as the Caffres, or Arab merchants of Africa.

Nearly three years have elapsed since the naturalist became established in his new quarters, and his collection has grown to be a large one. Safely landed in any European port, it would be worth many thousands of dollars; and thither he wishes to have it shipped as soon as possible. He has already warned Naraguana of his wish, and that the freight is ready; the chief, on his part, promising to make immediate preparations for its transport overland.

But a week has passed over, and no Naraguana, nor any messenger from him, has made appearance at the estancia. No Indian of the Tovas tribe has been seen about the place, nor anywhere near it; in short, no redskin has been seen at all, save the guanos, Halberger’s own male and female domestics.

Strange all this! Scarce ever has a whole week gone by without his receiving a visit from the Tovas chief, or some one of his tribe; and rarely half this time without Naraguana’s own son, by name Aguara, favouring the family with a call, and making himself as agreeable as savage may in the company of civilised people.

For all, there is one of that family to whom his visits are anything but agreeable; in truth, the very reverse. This Cypriano, who has conceived the fancy, or rather feels conviction, that the eyes of the young Tovas chief rest too often, and too covetously, on his pretty cousin, Francesca. Perhaps, except himself, no one has noticed this, and he alone is glad to count the completion of a week without any Indian having presented himself at his uncle’s establishment.

Though there is something odd in their prolonged non-appearance, still it is nothing to be alarmed about. On other occasions there had been intervals of absence as long, and even longer, when the men of the tribe were away from their tolderia, on some foraging or hunting expedition. Nor would Halberger have thought anything of it; but for the understanding between him and the Tovas chief, in regard to the transport of his collections. Naraguana had never before failed in any promise made to him. Why should he in this?

A sense of delicacy hinders the naturalist from riding over to the Tovas town, and asking explanation why the chief delays keeping his word. In all such matters, the American Indian, savage though styled, is sensitive as the most refined son of civilisation; and, knowing this, Ludwig Halberger waits for Naraguana to come to him.

But when a second week has passed, and a third, without the Tovas chief reporting himself, or sending either message or messenger, the Prussian becomes really apprehensive, not so much for himself, as the safety of his red-skinned protector. Can it be that some hostile band has attacked the Tovas tribe, massacred all the men, and carried off the women? For in the Chaco are various communities of Indians, often at deadly feud with one another. Though such conjecture seems improbable, the thing is yet possible; and to assure himself, Halberger at length resolves upon going over to the tolderia of the Tovas. Ordering his horse saddled, he mounts, and is about to ride off alone, when a sweet voice salutes him, saying:—

“Papa! won’t you take me with you?”

It is his daughter who speaks, a girl not yet entered upon her teens.

“In welcome, Francesca. Come along!” is his answer to her query.

“Then stay till I get my pony. I sha’n’t be a minute.”

She runs back towards the corrals, calling to one of the servants to saddle her diminutive steed. Which, soon brought round to the front of the house, receives her upon its back.

But now another, also a soft, sweet voice, is heard in exhortation. It is that of Francesca’s mother, entering protest against her husband either going alone, or with a companion so incapable of protecting him. She says:—

“Dear Ludwig, take Caspar with you. There may be danger—who knows?”

“Let me go, tio?” puts in Cypriano, with impressive eagerness, his eyes turned towards his cousin as though he did not at all relish the thought of her visiting the Tovas village without his being along with her.

“And me, too?” also requests Ludwig, the son, who is two years older than his sister.

“No, neither of you,” rejoins the father. “Ludwig, you would not leave your mother alone? Besides, remember I have set both you and Cypriano a lesson, which you must learn off to-day. There is nothing to fear, querida!” he adds, addressing himself to his wife. “We are not now in Paraguay, but a country where our old Friend Francia and his satellites dare not intrude on us. Besides, I cannot spare the good Caspar from some work I have given him to do. Bah! ’Tis only a bit of a morning’s trot there and back; and if I find there’s nothing wrong, we’ll be home again in little ever a couple of hours. So adios! Vamos, Francesca!”

With a wave of his hand he moves off, Francesca giving her tiny roadster a gentle touch of the whip, and trotting by his side.

The other three, left standing in the verandah, with their eyes follow the departing equestrians, the countenance of each exhibiting an expression that betrays different emotions in their minds, these differing both as to the matter of thought and the degree of intensity. Ludwig simply looks a little annoyed at having to stay at home when he wanted to go abroad, but without any great feeling of disappointment; whereas Cypriano evidently suffers chagrin, so much that he is not likely to profit by the appointed lesson. With the Señora herself it is neither disappointment nor chagrin, but a positive and keen apprehension. A daughter of Paraguay, brought up to believe its ruler all powerful over the earth, she can hardly realise the idea of there being a spot where the hand of “El Supremo” cannot reach and punish those who have thwarted his wishes or caprices. Many the tale has she heard whispered in her ear, from the cradle upwards, telling of the weird power of this wicked despot, and the remorseless manner in which he has often wielded it. Even after their escape into the chaco, where, under the protection of the Tovas chief, they might laugh his enmity to scorn, she has never felt the confidence of complete security. And now, that an uncertainty has arisen as to what has befallen Naraguana and his people, her fears became redoubled and intensified. Standing in the trellissed verandah, her eyes fixed upon the departing forms of her husband and daughter, she has a heaviness at the heart, a presentiment of some impending danger, which seems so near and dreadful as to cause shivering throughout her frame.

The two youths, observing this, essay to reassure her—one in filial duty, the other with affection almost as warm.

Alas! in vain. As the crown of the tall hat worn by her husband, goes down behind the crest of a distant ridge, Francesca’s having sooner disappeared, her heart sinks at the same time; and, making a sign of the cross, she exclaims in desponding accents:—

“Madre de Dios! We may ne’er see them more!”

Chapter Five.

A Deserted Village.

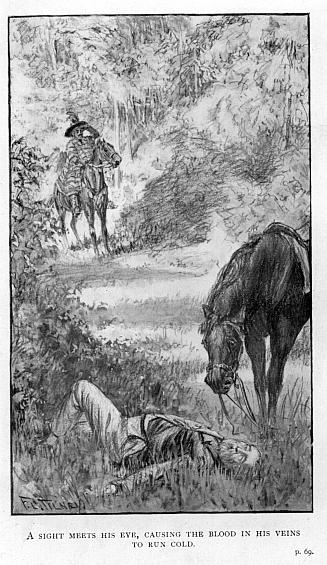

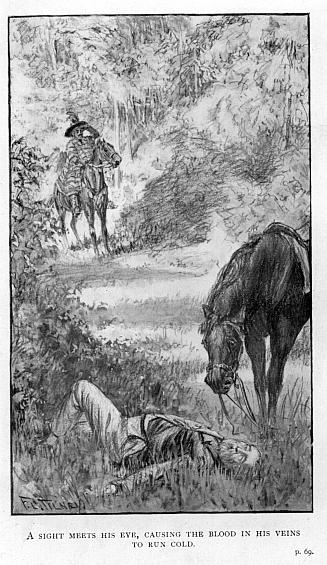

Riding at a gentle amble, so that his daughter on her small palfrey may easily keep up with him, Halberger in due time arrives at the Indian village; to his surprise seeing it is no more a village, or only a deserted one! The toldos of bamboo and palm thatch are still standing, but untenanted—every one of them!

Dismounting, he steps inside them, one after the other, but finds each and all unoccupied—neither man, woman, nor child within; nor without, either in the alleys between, or on the large open space around which the frail tenements are set, that has served as a loitering-place for the older members of the tribe, and a play-ground for the younger.

The grand council room, called malocca, he also enters with like result; no one is inside it—not a soul to be seen anywhere, either in the streets of the village or on the plain stretching around!

He is alarmed as much as surprised; indeed more, since he has been anticipating something amiss. But by degrees, as he continues to make an examination of the place, his apprehensions became calmed down, these having been for the fate of the Indians themselves. His first thought he had entertained while conjecturing the cause of their long absence from the estancia, was that some hostile tribe had attacked them, massacred the men, and carried captive the women and children. Such tragical occurrences are far from uncommon among the red aborigines of America, Southern or Northern. Soon, however, his fears on this score are set at rest. Moving around, he detects no traces of a struggle, neither dead bodies nor blood. If there had been a fight the corpses of the fallen would surely still be there, strewing the plain; and not a toldo would be standing or seen—instead, only their ashes.

As it is, he finds the houses all stripped of their furniture and domestic utensils; these evidently borne off not as by marauders, but taken away in a systematic manner, as when a regular move is made by these nomadic people. He sees fragments of cut sipos and bits of raw-hide thong—the overplus left after packing.

Though no longer alarmed for the safety of the Indians, he is, nevertheless, still surprised and perplexed. What could have taken them away from the tolderia, and whither can they have gone? Strange, too, Naraguana should have left the place in such unceremonious fashion, without giving him, Halberger, notice of his intention! Their absence on this occasion cannot be accounted for by any hunting or foraging expedition, nor can it be a foray of war. In any of these cases the women and children would have been left behind. Beyond doubt, it is an absolute abandonment of the place; perhaps with no intention of returning to it; or not for a very long time.

Revolving these thoughts through his mind, Halberger climbs back into his saddle, and sits further reflecting. His daughter, who has not dismounted, trots up to his side, she, too, in as much wonderment as himself; for, although but a very young creature, almost a child in age, she has passed through experiences that impart the sageness of years. She knows of all the relationships which exist between them and the Tovas tribe, and knows something of why her father fled from his old home; that is, she believes it to have been through fear of El Supremo, the “bogie” of every Paraguayan child, boy or girl. Aware of the friendship of the Tovas chief, and the protection he has extended to them, she now shares her father’s surprise, as she had his apprehensions.

They exchange thoughts on the subject—the child equally perplexed with the parent; and after an interval passed in conjecturing, all to no purpose, Halberger is about to turn and ride home again, when it occurs to him he had better find out in what direction the Indians went away from their village.

There is no difficulty in discovering this; the trail of their ridden horses, still more that of their pack animals, is easily found and followed. It leads out from the village at the opposite end from that by which they themselves entered; and after following it for a mile or so along the river’s bank, they see that it takes an abrupt turn across the pampa. Up to this point it has been quite conspicuous, and is also beyond; for although it is anything but recent, no rain has since fallen, and the hoof-prints of the horses can be here and there distinguished clean cut on the smooth sward, over which the mounted men had gone at a gallop. Besides, there is the broad belt of trodden grass where the pack animals toiled more slowly along; and upon this bits of broken utensils, with other useless articles, have been dropped and abandoned, plainly proclaiming the character of the cavalcade.

Here Halberger would halt, and turn back, but for a remembrance coming into his mind which hinders, at the same time urging him to continue on. In one of his hunting excursions he had been over this ground before, and remembers that some ten miles further on a tributary stream flows into the Pilcomayo. Curious to know whether the departing Tovas have turned up this tributary, or followed the course of the main river, he determines to proceed. For glancing skyward, he sees that the sun is just crossing the meridian, and knows he will have no lack of time before darkness can overtake him. The circumstances and events, so strange and startling, cause him to forget that promise made to his wife—soon to be back at the estancia.

Spurring his horse, and calling on Francesca to follow, he starts off again at a brisk gallop; which is kept up till they draw bridle on the bank of the influent stream.

This, though broad, is but shallow, with a selvedge of soft ooze on either side; and on that where they have arrived the mud shows the track of several hundred horses. Without crossing over, Halberger can see that the Indian trail leads on along the main river, and not up the branch stream.

Again he is on the balance, to go back—with the intention of returning next day, accompanied by Caspar, and making further search for the missing Indians—when an object comes under his eye, causing him to give a start of surprise.

It is only the track of a horse; and strange that this should surprise him, among hundreds. But the one on which he has fixed his attention differs from all the rest in being the hoof-print of a shod horse, while the others are as Nature made them. Still even this difference would not make so much impression upon him were the tracks of the same age. Himself skilled as any Indian in the reading of pampas sign, at a glance he sees they are not. The hoof-marks of the Tovas horses in their travelling train are all quite three weeks old; while the animal having the iron on its heels, must have crossed over that stream within the week.

Its rider, whoever he was, could not have been in the company of the departing Tovas; and to him now regarding the tracks, it is only a question as to whether he were a white man, or Indian. Everything is against his having been the former, travelling in a district tabooed to the palefaces, other than Halberger and his—everything, save the fact of his being on the back of a shod horse; while this alone hinders the supposition of the animal being bestridden by an Indian.

For a long while the hunter-naturalist, with Francesca by his side, sits in his saddle contemplating the shod hoof-prints in a reverie of reflection. He at length thinks of crossing the tributary stream, to see if these continue on with the Indian trail, and has given his horse the spur, with a word to his daughter to do likewise, when voices reach his ear from the opposite side, warning him to pull in again. Along with loud words and ejaculations there is laughter; as of boys at play, only not stationary in one place, but apparently moving onward, and drawing nearer to him.

On both sides of the branch stream, as also along the banks of the river, is a dense growth of tropical vegetation—mostly underwood, with here and there a tall moriché palm towering above the humbler shrubs. Through this they who travel so gleefully are making their way; but cannot yet be seen from the spot where Halberger has halted. But just on the opposite bank, where the trail goes up from the ford, is a bit of treeless sward, several acres in extent, in all likelihood, kept clear of undergrowth by the wild horses and other animals on their way to the water to drink. It runs back like an embayment into the close-growing scrub, and as the trail can be distinguished debouching at its upper end, the naturalist has no doubt that these joyous gentry are approaching in that direction.

And so are they—a singular cavalcade, consisting of some thirty individuals on horseback; for all are mounted. Two are riding side by side, some little way ahead of the others, who follow also in twos—the trail being sufficiently wide to admit of the double formation. For the Indians of pampa and prairie—unlike their brethren of the forest, do not always travel “single file.” On horseback it would string them out too far for either convenience or safety. Indeed, these horse Indians not unfrequently march in column, and in line.

With the exception of the pair spoken of as being in the advance, all the others are costumed, and their horses caparisoned, nearly alike. Their dress is of the simplest and scantiest kind—a hip-cloth swathing their bodies from waist to mid-thigh, closely akin to the “breech-clout” of the Northern Indian, only of a different material. Instead of dressed buckskin, the loin covering of the Chaco savage is a strip of white cotton cloth, some of wool in bands of bright colour having a very pretty effect. But, unlike their red brethren of the North, they know nought of either leggings or moccasin. Their mild climate calls not for such covering; and for foot protection against stone, thorn, or thistle, the Chaco Indian rarely ever sets sole to the ground—his horse’s back being his home habitually.

Those now making way through the wood show limbs naked from thigh to toe, smooth as moulded bronze, and proportioned as if cut by the chisel of Praxiteles. Their bodies above also nude; but here again differing from the red men of the prairies. No daub and disfigurement of chalk, charcoal, vermilion, or other garish pigment; but clear skins showing the lustrous hue of health, of bronze or brown amber tint, adorned only with some stringlets of shell beads, or the seeds of a plant peculiar to their country.

All are mounted on steeds of small size, but sinewy and perfect in shape, having long tails and flowing manes; for the barbarism of the clipping shears has not yet reached these barbarians of the Chaco.

Nor yet know they, or knowing, they use not saddle. A piece of ox-hide, or scrap of deer-skin serves them for its substitute; and for bridle a raw-hide rope looped around the under jaw, without head-strap, bittless, and single reined, enabling them to check or guide their horses, as if these were controlled by the cruellest of curbs, or the jaw-breaking Mameluke bitt.

As they file forth two by two into the open ground, it is seen that there is some quality and fashion common to all; to wit, that they are all youths—not any of them over twenty—and that they wear their hair cropped in front, showing a square line across the forehead, but left untouched on the crown and back of the head. There it falls in full profuseness, reaching to the hips, and in the case of some mingling with the tails, of their horses.

Two, however, are notably different from the rest; they riding in the advance, with a horse’s length or so of interval between them and their following. One of the two differs only in the style of his dress; being an Indian as the others, and, like them, quite a youth, to all appearance the youngest of the party. Yet also their chief, by reason of his richer and grander dress; his attire being of the most picturesque and costly kind worn by the Chaco savages. Covering his body, from the breast to half-way down his thighs, is a sort of loosely-fitting tunic of white cotton stuff. Sleeveless, it leaves his arm bare from nigh the shoulder to the wrist, around which glistens a bracelet with the sheen of solid gold. His limbs also are bare, save a sort of gartering below the knee, of shell and bead embroidery. On his head is a fillet band ornamented in like manner, with bright plumes, set vertically around it—the tail-feathers of the guacamaya, one of the most superb of South American parrots. But the most distinctive article of his apparel is his manta, a sort of cloak of the poncho kind, hanging loosely behind his back, but altogether different from the well-known garment of the gauchos, which is usually woven from wool. That on the shoulders of the young Indian is of no textile fabric, but the skin of a fawn, tanned and bleached to the softness and whiteness of a dress kid glove, the outward side being elaborately feather-worked in flowers and patterns, the feathers obtained from many a bird of gay plumage.

Of form perfectly symmetrical, the young Indian, save for his complexion, would seem a sort of Apollo, or Hyperion on horseback; while he who rides alongside him, withal that his skin is white, or once was, might well be likened to the Satyr. A man over thirty years of age, tall, and of tough, sinewy frame, with a countenance of the most sinister cast, dressed gaucho fashion, with the wide petticoat breeches lying loose about his limbs, a striped poncho over his shoulders, and a gaudy silken kerchief tied turban-like around his temples. But no gaucho he, nor individual of any honest calling: instead, a criminal of deepest dye, experienced in every sort of villainy. For this man is Rufino Valdez, well-known in Assuncion as one of Francia’s familiars, and more than suspected of being one of his most dexterous assassins.

Chapter Six.

An Old Enemy in a New Place.

Could the hunter-naturalist but know what has really occurred in the Tovas tribe, and the nature of the party now approaching, he would not stay an instant longer on the banks of that branch stream; instead, hasten back home with his child fast as their animals could carry them, and once at the estancia, make all haste to get away from it, taking every member of his family along with him. But he has no idea that anything has happened hostile to him or his, nor does he as yet see the troop of travellers, whose merry voices are making the woods ring around them: for, on the moment of his first hearing them, they were at a good distance, and are some considerable time before coming in sight. At first, he had no thought of retreating, nor making any effort to place himself and his child in concealment. And for two reasons: one, because ever since taking up his abode in the Chaco, under the protection of Naraguana, he has enjoyed perfect security, as also the consciousness of it. Therefore, why should he be alarmed now? As a second reason for his not feeling so, an encounter with men, in the mood of those to whom he is listening, could hardly be deemed dangerous. It may be but the Tovas chief and his people, on return to the town they had abandoned; and, in all likelihood, it is they. So, for a time, thinks he.

But, again, it may not be; and if any other Indians—if a band of Anguite, or Guaycurus, both at enmity with the Tovas—then would they be also enemies to him, and his position one of great peril. And now once more reflecting on the sudden, as unexplained, disappearance of the latter from their old place of residence—to say the least, a matter of much mystery—bethinking himself, also, that he is quite twenty miles from his estancia, and for any chances of retreat, or shifts for safety, worse off than if he were alone, he at length, and very naturally, feels an apprehension stealing over him. Indeed, not stealing, nor coming upon him slowly, but fast gathering, and in full force. At all events, as he knows nothing of who or what the people approaching may be, it is an encounter that should, if possible, be avoided. Prudence so counsels, and it is but a question how this can best be done. Will they turn heads round, and go galloping back? Or ride in among the bushes, and there remain under cover till the Indians have passed? If these should prove to be Tovas, they could discover themselves and join them; if not, then take the chances of travelling behind them, and getting back home unobserved.

The former course he is most inclined to; but glancing up the bank, for he is still on the water’s edge, he sees that the sloping path he had descended, and by which he must return, is exposed to view from the opposite side of the stream, to a distance of some two hundred yards. To reach the summit of the slope, and get under cover of the trees crowning it, would take some time. True, only a minute or two; but that may be more than he can spare, since the voices seem now very near, and those he would shun must show themselves almost immediately. And to be seen retreating would serve no good purpose; instead, do him a damage, by challenging the hostility of the Indians, if they be not Tovas. Even so, were he alone, well-horsed as he believes himself to be—and in reality is—he would risk the attempt, and, like enough, reach his estancia in safety. But encumbered with Francesca on her diminutive steed, he knows they would have no chance in a chase across the pampa, with the red Centaurs pursuing. Therefore, not for an instant, or only one, entertains he thought of flight. In a second he sees it would not avail them, and decides on the other alternative—concealment. He has already made a hasty inspection of the ground near by, and sees, commencing at no great distance off, and running along the water’s edge, a grove of sumac trees which, with their parasites and other plants twining around their stems and branches, form a complete labyrinth of leaves. The very shelter he is in search of; and heading his horse towards it, at the same time telling Francesca to follow, he rides in by the first opening that offers. Fortunately he has struck upon a tapir path, which makes it easier for them to pass through the underwood, and they are soon, with their horses, well screened from view. Perhaps, better would it have been for them had they continued on, without making any stop, though not certain this, for it might have been all one in the end. As it is, still in doubt, half under the belief that he may be retreating from an imaginary danger—running away from friends instead of foes—as soon as well within the thicket, Halberger reins up again, at a point where he commands a view of the ford as it enters on the opposite side of the stream. A little glade gives room for the two animals to stand side by side, and drawing Francesca’s pony close up to his saddle-flap, he cautions her to keep it there steadily, as also to be silent herself. The girl needs not such admonition. No simple child she, accustomed only to the safe ways of cities and civilised life; but one knowing a great deal of that which is savage; and young though she is, having experienced trials, vicissitudes and dangers. That there is danger impending over them now, or the possibility of it, she is quite as conscious as her father, and equally observant of caution; therefore, she holds her pony well in hand, patting it on the neck to keep it quiet.

They have not long to stay before seeing what they half expected to see—a party of Indians. Just as they have got well fixed in place, with some leafy branches in front forming a screen over their faces, at the same time giving them an aperture to peep through, the dusky cavalcade shows its foremost files issuing out from the bushes on the opposite side of the stream. Though still distant—at least, a quarter of a mile—both father and daughter can perceive that they are Indians; mounted, as a matter of course, for they could not and did not, expect so see such afoot in the Chaco. But Francesca’s eyes are sharper sighted than those of her father, and at the first glance she makes out more—not only that it is a party of Indians, but these of the Tovas tribe. The feathered manta of the young chief, with its bright gaudy sheen, has caught her eye, and she knows whose shoulders it should be covering.

“Yes, father,” she says, in whisper, as soon as sighting it. “They are the Tovas! See yonder! one of the two leading—that’s Aguara.”

“Oh! then, we’ve nothing to fear,” rejoins her father, with a feeling of relief. “So, Francesca, we may as well ride back out and meet them. I suppose it is, as I’ve been conjecturing; the tribe is returning to its old quarters. I wonder where they’ve been, and why so long away. But we shall now learn all about it. And we’ll have their company with us, as far as their talderia; possibly all the way home, as, like enough, Naraguana will come on with us to the estancia. In either case—ha! what’s that. As I live, a white man riding alongside Aguara! Who can he be?”

Up to this, Halberger has neither touched his horse nor stirred a step; no more she, both keeping to the spot they had chosen for observation. And both now alike eagerly scan the face of the man, supposed to be white.

Again the eyes of the child, or her instincts, are keener and quicker than those of the parent; or, at all events, she is the first to speak, announcing a recognition.

“Oh, papa!” she exclaims, still in whispers, “it’s that horrid man who used to come to our house at Assuncion—him mamma so much disliked—the Señor Rufino.”

“Hish!” mutters the father, interrupting both with speech and gesture; then adds, “keep tight hold of the reins; don’t let the pony budge an inch!”

Well may he thus caution, for what he now sees is that he has good reason to fear; a man he knows to be his bitter enemy—one who, during the years of his residence in Paraguay, had repeatedly been the cause of trouble to him, and done many acts of injury and insult—the last and latest offered to his young wife. For it was Rufino Valdez who had been employed by the Dictator previously to approach her on his behalf.

And now Ludwig Halberger beholds the base villain in company with the Tovas Indians—his own friends, as he had every reason to suppose them—riding side by side with the son of their chief! What can it mean?

Halberger’s first thought is that Valdez may be their prisoner; for he, of course, knows of the hostility existing between them and the Paraguayans, and remembers that, in his last interview with Naraguana, the aged cacique was bitter as ever against the Paraguayan people. But no; there is not the slightest sign of the white man being guarded, bound, or escorted. Instead, he is riding unconstrained, side by side with the young Tovas chief, evidently in amicable relations—the two engaged in a conversation to all appearance of the most confidential kind!

Again Halberger asks, speaking within himself, what it can mean? and again reflecting endeavours to fathom the mystery: for so that strange juxtaposition appears to him. Can it be that the interrupted treaty of peace has been renewed, and friendship re-established between Naraguana and the Paraguayan Dictator? Even now, Valdez may be on a visit to the Tovas tribe on that very errand—a commissioner to arrange new terms of intercourse and amity? It certainly appears as if something of the kind had occurred. And what the Prussian now sees, taken in connection with the abandonment of the village alike matter of mystery—leads him to more than half-suspect there has. For again comes up the question, why should the Tovas chief have gone off without giving him warning? So suddenly, and not a word! Surely does it seem as if there has been friendship betrayed, and Naraguana’s protection withdrawn. If so, it will go hard with him, Halberger; for well knows he, that in such a treaty there would be little chance of his being made an object of special amnesty. Instead, one of its essential claims would sure be, the surrendering up himself and his family. But would Naraguana be so base? No; he cannot believe it, and this is why he is as much surprised as puzzled at seeing Valdez when he now sees him.

In any case things have a forbidding look, and the man’s presence there bodes no good to him. More like the greatest evil; for it may be death itself. Even while sitting upon his horse, with these reflections running through his mind—which they do, not as related, but with the rapidity of thought itself—he feels a presentiment of that very thing. Nay, something more than a presentiment, something worse—almost the certainty that his life is near its end! For as the complete Indian cohort files forth from among the bushes, and he takes note of how it is composed—above all observing the very friendly relations between Valdez and the young chief—he knows it must affect himself to the full danger of his life. Vividly remembers he the enmity of Francia’s familiar, too deep and dire to have been given up or forgotten. He remembers, too, of Valdez being noted as a skilled rastrero, or guide—his reputed profession. Against such a one the step he has taken to conceal himself is little likely to serve him. Are not the tracks of his horse, with those of the pony, imprinted in the soft mud by the water’s edge where they had halted? These will not be passed over by the Indians, or Valdez, without being seen and considered. Quite recent too! They must be observed, and as sure will they be followed up to where he and his child are in hiding. A pity he has not continued along the tapir path, still further and far away! Alas! too late now; the delay may be fatal.

In a very agony of apprehension thus reflecting, Ludwig Halberger with shoulders stooped over his saddle-bow and head bent in among the branches, watches the Indian cavalcade approaching the stream’s bank; the nearer it comes, the more certain he that himself and his child are in deadliest danger.

Chapter Seven.

Valdez the “Vaqueano.”

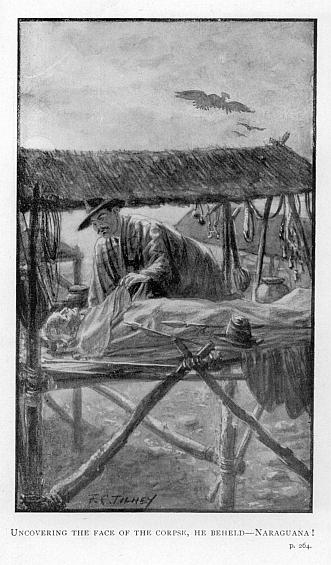

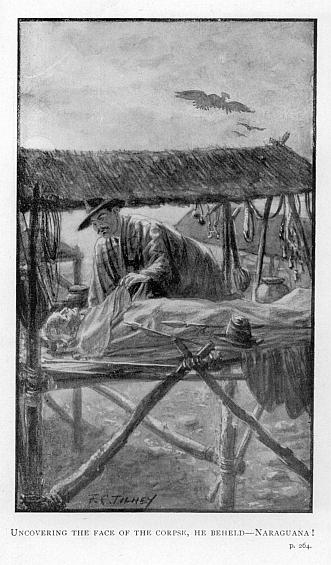

To solve the seeming enigma of Rufino Valdez travelling in the company of the Tovas Indians, and on friendly terms with their young chief—for he is so—it will be necessary to turn back upon time, and give some further account of the vaqueano himself, and his villainous master; as also to tell why Naraguana and his people abandoned their old place of abode, with other events and circumstances succeeding. Of these the most serious has been the death of Naraguana himself. For the aged cacique is no more; having died only a few days after his latest visit paid to his palefaced protégé.

Nor were his last moments spent at the tolderia, now abandoned. His death took place at another town of his people some two hundred miles from this, and farther into the interior of the Chaco; a more ancient residence of the Tovas tribe—in short, their “Sacred city” and burying-place. For it is the custom of these Indians when any one of them dies—no matter when, where, and how, whether by the fate of war, accident in the chase, disease, or natural decay—to have the body borne to the sacred town, and there deposited in a cemetery containing the graves of their fathers. Not graves, as is usual, underground; but scaffolds standing high above it—such being the mode of Tovas interment.

Naraguana’s journey to this hallowed spot—his last in life—had been made not on horseback, but in a litera, borne by his faithful braves. Seized with a sudden illness, and the presentiment that his end was approaching, with a desire to die in the same place where he had been born, he gave commands for immediate removal thither—not only of himself, but everything and even body belonging to his tribe. It was but the work of a day; and on the next the old settlement was left forsaken, just as the hunter-naturalist has found it.

Had the latter been upon the banks of that branch stream just three weeks before, he would there have witnessed one of those spectacles peculiar to the South American pampas; as the prairies of the North. That is the crossing of a river by an entire Indian tribe, on the move from one encampment, or place of residence, to another. The men on horseback swimming or wading their horses; the women and children ferried over in skin boats—those of the Chaco termed pelotas—with troops of dogs intermingled in the passage; all amidst a fracas of shouts, the barking of dogs, neighing of horses, and shrill screaming of the youngsters, with now and then a peal of merry laughter, as some ludicrous mishap befalls one or other of the party. No laugh, however, was heard at the latest crossing of that stream by the Tovas. The serious illness of their chief forbade all thought of merriment; so serious, that on the second day after reaching the sacred town he breathed his last; his body being carried up and deposited upon that aerial tomb where reposed the bleaching bones of many other caciques—his predecessors.

His sudden seizure, with the abrupt departure following, accounts for Halberger having had no notice of all this—Naraguana having been delirious in his dying moments, and indeed for some time before. And his death has caused changes in the internal affairs of the Tovas tribe, attended with much excitement. For the form of government among these Chaco savages is more republican than monarchical; each new cacique having to receive his authority not from hereditary right, but by election. His son, Aguara, however, popular with the younger warriors of the tribe, carried the day, and has become Naraguana’s successor.

Even had the hunter-naturalist been aware of these events, he might not have seen in them any danger to himself. For surely the death of Naraguana would not affect his relations with the Tovas tribe; at least so far as to losing their friendship, or bringing about an estrangement. Not likely would such have arisen, but for certain other events of more sinister bearing, transpiring at the same period; to recount which it is necessary for us to return still further upon time, and again go back to Paraguay and its Dictator.

Foiled in his wicked intent, and failing to discover whither his intended victims had fled, Francia employed for the finding of them one of his minions—this man of most ill repute, Rufino Valdez. It did not need the reward offered to secure the latter’s zeal; for, as stated, he too had his own old grudge against the German, brought about by a still older and more bitter hostility to Halberger’s right hand man—Gaspar, the gaucho. With this double stimulus to action, Valdez entered upon the prosecution of his search, after that of the soldiers had failed. At first with confident expectation of a speedy success; for it had not yet occurred to either him or his employer that the fugitives could have escaped clear out of the country; a thing seemingly impossible with its frontiers so guarded. It was only after Valdez had explored every nook and corner of Paraguayan territory in search of them, all to no purpose, that Francia was forced to the conclusion, they were no longer within his dominions. But, confiding in his own interpretation of international law, and the rights of extradition, he commissioned his emissary to visit the adjacent States, and there continue inquiry for the missing ones. That law of his own making, already referred to, led him to think he could demand the Prussian’s wife to be returned to Paraguay, whatever claim he might have upon the Prussian himself.

For over two years has Rufino Valdez been occupied in this bootless quest, without finding the slightest trace of the fugitives, or word as to their whereabouts. He has travelled down the river to Corrientes, and beyond to Buenos Ayres, and Monte Video at the La Plata’s mouth. Also up northward to the Brazilian frontier fort of Coimbra; all the while without ever a thought of turning his steps towards the Chaco!

Not so strange, though, his so neglecting this noted ground; since he had two sufficient reasons. The first, his fear of the Chaco savages, instinctive to every Paraguayan; the second, his want of faith, shared by Francia himself, that Halberger had fled thither. Neither could for a moment think of a white man seeking asylum in the Gran Chaco; for neither knew of the friendship existing between the hunter-naturalist and the Tovas chief.

It was only after a long period spent in fruitless inquiries, and while sojourning at Coimbra that the vaqueano first found traces of those searched for; there learning from some Chaco Indians on a visit to the fort—that a white man with his wife, children, and servants, had settled near a tolderia of the Tovas, on the banks of the Pilcomayo river. Their description, as given by these Indians—who were not Tovas, but of a kindred tribe—so exactly answered to the hunter-naturalist and his family, that Valdez had no doubt of its being they. And hastily returning to Paraguay, he communicated what he had been told to the man for whom he was acting.

“El Supremo,” overjoyed at the intelligence, promised to double the reward for securing the long-lost runaways. A delicate and difficult matter still; for there was yet the hostility of the Tovas to contend against. But just at this crisis, as if Satan had stepped in to assist his own sort, a rumour reaches Assuncion of Naraguana’s death; and as the rancour had arisen from a personal affront offered to the chief himself, Francia saw it would be a fine opportunity for effecting reconciliation, as did also his emissary. Armed with this confidence, his old enmity to Halberger and gaucho, ripe and keen as ever, Valdez declared himself willing to risk his life by paying a visit to the Tovas town, and, if possible, induce these Indians to enter into a new treaty—one of its terms to be their surrendering up the white man, who had been so long the guest of their deceased cacique.

Fully commissioned and furnished with sufficient funds—gold coin which passes current among the savages of the Chaco, as with civilised people—the plenipotentiary had started off, and made his way up the Pilcomayo, till reaching the old town of the Tovas. Had Halberger’s estancia stood on the river’s bank, the result might have been different. But situated at some distance back, Valdez saw it not in passing, and arrived at the Indian village to find it, as did the hunter-naturalist himself, deserted. An experienced traveller and skilled tracker, however, he had no difficulty in following the trail of the departed people, on to their other town; and it was the track of his horse on the way thither, Halberger has observed on the edge of the influent stream—as too well he now knows.

Chapter Eight.

A Compact between Scoundrels.

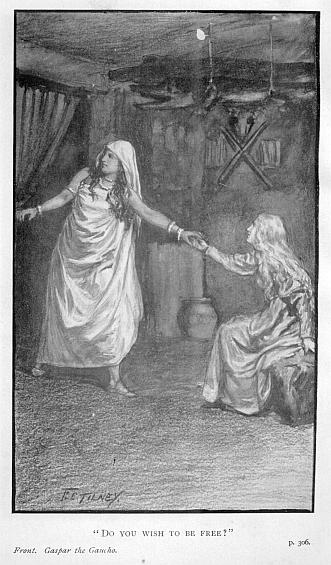

What the upshot of Valdez’s errand as commissioner to the Tovas tribe may be told in a few words. That he has been successful, in some way, can be guessed from his being seen in close fellowship with him who is now their chief. For, otherwise, he would not be there with them or only as a prisoner. Instead, he is, as he appears, the accepted friend of Aguara, however false the friendship. And the tie which has knit them together is in keeping with the character of one, if not both. All this brought about without any great difficulty, or only such as was easily overcome by the Paraguayan plenipotentiary. Having reached the Tovas town—that where the tribe is now in permanent residence—only a day or two after Naraguana’s death, he found the Indians in the midst of their lamentations; and, through their hearts rendered gentle by grief, received friendly reception. This, and the changed régime, offered a fine opportunity for effecting his purpose, of which the astute commissioner soon availed himself. The result, a promise of renewal of the old peace treaty; which he has succeeded in obtaining, partly by fair words, but as much by a profuse expenditure of the coin with which Francia had furnished him. This agreed to by the elders of the tribe; since they had to be consulted. But without a word said about their late chiefs protégé—the hunter-naturalist—or aught done affecting him. For the Paraguayan soon perceived, that the sagamores would be true to the trust Naraguana had left; in his last coherent words enjoining them to continue protection to the stranger, and hold him, as his, unharmed.

So far the elders in council; and the astute commissioner, recognising the difficulty, not to say danger, of touching on this delicate subject, said nothing to them about it.

For all, he has not left the matter in abeyance, instead, has spoken of it to other ears, where he knew he would be listened to with more safety to himself—the ears of Aguara. For he had not been long in the Tovas town without making himself acquainted with the character of the new cacique, as also his inclinings—especially those relating to Francesca Halberger. And that some private understanding has been established between him and the young Tovas chief is evident from the conversation they are now carrying on.

“You can keep the muchachita at your pleasure,” says Valdez, having, to all appearance, settled certain preliminaries. “All my master wants is, to vindicate the laws of our country, which this man Halberger has outraged. As you know yourself, Señor Aguara, one of our statutes is that no foreigner who marries a Paraguayan woman may take her out of the country without permission of the President—our executive chief. Now this man is not one of our people, but a stranger—a gringo—from far away over the big waters; while the Señora, his wife, is Paraguayan, bred and born. Besides, he stole her away in the night, like a thief, as he is.”

Naraguana would not tamely have listened to such discourse. Instead, the old chief, loyal to his friendship, would have indignantly repelled the allegations against his friend and protégé. As it is, they fall upon the ear of Naraguana’s son without his offering either rebuke or protest.

Still, he seems in doubt as to what answer he should make, or what course he ought to pursue in the business between them.

“What would you have me do, Señor Rufino?” he asks in a patois of Spanish, which many Chaco Indians can speak; himself better than common, from his long and frequent intercourse with Halberger’s family. “What want you?”

“I don’t want you to do anything,” rejoins the vaqueano. “If you’re so squeamish about giving offence to him you call your father’s friend, you needn’t take any part in the matter, or at all compromise yourself. Only stand aside, and allow the law I’ve just spoken of to have fulfilment.”

“But how?”

“Let our President send a party of his soldiers to arrest those runaways, and carry them back whence they came. Now that you’ve proposed to renew the treaty with us, and are hereafter to be our allies—and, I hope, fast friends—it is only just and right you should surrender up those who are our enemies. If you do, I can say, as his trusted representative, that El Supremo will heap favours, and bestow rich presents on the Tovas tribe; above all, on its young cacique—of whom I’ve heard him speak in terms of the highest praise.”

Aguara, a vain young fellow, eagerly drinks in the fulsome flattery, his eyes sparkling with delight at the prospect of the gifts thus promised. For he is as covetous of wealth as he is conceited about his personal appearance.

“But,” he says, thinking of a reservation, “would you want us to surrender them all? Father, mother—”

“No, not all,” rejoins the ruffian, interrupting. “There is one,” he continues, looking askant at the Indian, with the leer of a demon, “one, I take it, whom the young Tovas chief would wish to retain as an ornament to his court. Pretty creature the niña was, when I last saw her; and I have no doubt still is, unless your Chaco sun has made havoc with her charms. She had a cousin about her own age, by name Cypriano, who was said to be very fond of her; and rumour had it around Assuncion, that they were being brought up for one another.”

Aguara’s brow blackens, and his dark Indian eyes seem to emit sparks of fire.

“Cypriano shall never have her!” he exclaims in a tone of angry determination.

“How can you help it, amigo?” interrogates his tempter. “That is, supposing the two are inclined for one another. As you know, her father is not only a paleface, but a gringo, with prejudices of blood far beyond us Paraguayans, who are half-Indian ourselves. Ah! and proud of it too. Being such, he would never consent to give his daughter in marriage to a red man—make a squaw of her, as he would scornfully call it. No, not even though it were the grandest cacique in the Chaco. He would see her dead first.”