"'Well,' says she, 'we never played anything for pikers, did we, dad?'"

"'Well,' says she, 'we never played anything for pikers, did we, dad?'"

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Man Next Door

Author: Emerson Hough

Release Date: November 24, 2007 [eBook #23606]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAN NEXT DOOR***

I - How Come Us to Move

II - Where We Threw In

III - Us Living in Town

IV - Us and Christmas Eve

V - Us and the Home Ranch

VI - Us and Them Better Thing

VII - What Their Hired Man Done

VIII - How Old Man Wright Done Business

IX - Us and Their Fence

X - Us Being Alderman

XI - Us and the Freeze-Out

XII - Us and a Accidental Friend

XIII - Them and the Range Law

XIV - How Their Hired Man Come Back

XV - The Commandment That Was Broke

XVI - How I Was Foreman

XVII - Him and the Front Door

XVIII - How Tom Stacked Up

XIX - Them and Bonnie Bell

XX - What Our William Done

XXI - Her Pa's Way of Thinking

XXII - Me and Their Line Fence

XXIII - Tom and Her

XXIV - How Bonnie Bell Left Us All

XXV - Me and Them

XXVI - How I Went Back

XXVII - How I Quit Old Man Wright

XXVIII - The Hole in the Wall

XXIX - How the Game Broke

XXX - How It Come Out After All

"'Well,' says she, 'we never played anything for pikers, did we, dad?'"

"'Well,' says he, 'our dog is more of a trench fighter.'"

"'I know now what it means to be a woman and in love.'"

"She knowed where he carried his gun."

Bonnie Bell was her real name—Bonnie Bell Wright. It sounds like a race horse or a yacht, but she was a girl. Like enough that name don't suit you exactly for a girl, but it suited her pa, Old Man Wright. I don't know as she ever was baptized by that name, or maybe baptized at all, for water was scarce in Wyoming; but it never would of been healthy to complain about that name before Old Man Wright or me, Curly. As far as that goes, she had other names too. Her ma called her Mary Isabel Wright; but her pa got to calling her Bonnie Bell some day when she was little, and it stuck, especial after her ma died.

That was when Bonnie Bell was only four years old, that her ma died, and her dying made a lot of difference on the ranch. I reckon Old Man Wright probably stole Bonnie Bell's ma somewhere back in the States when he was a young man. She must of loved him some or she wouldn't of came to Wyoming with him. She was tallish, and prettier than any picture in colors—and game! She tried all her life to let on she liked the range, but she never was made for it.

Now to see her throw that bluff and get away with it with Old Man Wright—and no one else, especial me—and to see Old Man Wright worrying, trying to figure out what was wrong, and not being able to—that was the hardest thing any of us ever tried. The way he worked to make the ma of Bonnie Bell happy was plain for anybody to see. He'd stand and look at the place where he seen her go by last, and forget he had a rope in his hand and his horse a-waiting.

We had to set at the table, all three of us, after she died—him and the kid and me—and nobody at the end of the table where she used to set—her always in clothes that wasn't just like ours. I couldn't hardly stand it. But that was how game Old Man Wright was.

He wasn't really old. Like when he was younger, he was tall and straight, and had sandy hair and blue eyes, and weighed round a hundred and eighty, lean. Everybody on the range always had knew Old Man Wright. He was captain of the round-up when he was twenty and president of the cattle association as soon as it was begun. I don't know as a better cowman ever was in Wyoming. He grew up at it.

So did Bonnie Bell grow up at it, for that matter. She pleased her pa a plenty, for she took to a saddle like a duck, so to speak. Time she was fifteen she could ride any of the stock we had, and if a bronc' pitched when she rid him she thought that was all right; she thought it was just a way horses had and something to be put up with that didn't amount to much. She didn't know no better. She never did think that anything or anybody in the world had it in for her noways whatever. She natural believed that everything and everybody liked her, for that was the way she felt and that was the way it shaped there on the range. There wasn't a hand on the place that would of allowed anything to cross Bonnie Bell in any way, shape or manner.

She grew up tallish, like her pa, and slim and round, same as her ma. She had brownish or yellowish hair, too, which was sunburned, for she never wore no bonnet; but her eyes was like her ma's, which was dark and not blue, though her skin was white like her pa's under his shirt sleeves, only she never had no freckles the way her pa had—some was large as nickels on him in places. She maybe had one freckle on her nose, but little.

Bonnie Bell was a rider from the time she was a baby, like I said, and she went into all the range work like she was built for it. Wild she was, like a filly or yearling that kicks up its heels when the sun shines and the wind blows. And pretty! Say, a new wagon with red wheels and yellow trimmings ain't fit for to compare with her, not none at all!

When her ma died Old Man Wright wasn't good for much for a long time, for he was always studying over something. Though he never talked a word about her I allow that somehow or other after she died he kind of come to the conclusion that maybe she hadn't been happy all the time, and he got to thinking that maybe he'd been to blame for it somehow. After it was too late, maybe, he seen that she couldn't never have grew to be no range woman, no matter how long she lived.

But still we all got to take things, and he done so the best he could; and after the kid begun to grow up he was happier. All the time he was a-rolling up the range and the stock, till he was richer than anybody you ever did see, though his clothes was just about the same. But, come round the time when Bonnie Bell was fourteen or fifteen years old, about proportionate like when a filly or heifer is a yearling or so, he begun to study more.

There was a room up in the half-story where sometimes we kept things we didn't need all the time—the fancy saddles and bridles and things. Some old trunks was in it. I reckon maybe Old Man Wright went up there sometimes when he didn't say nothing about it to nobody. Anyhow once I went up there for something and I seen him setting on the floor, something in his hand that he was looking at so steady he never heard me. I don't know what it was—picture maybe, or letter; and his face was different somehow—older like—so that he didn't seem like the same man. You see, Old Man Wright was maybe soft like on the inside, like plenty of us hard men are.

I crept out and felt right much to blame for seeing what I had, though I didn't mean to. Seems like all my life I had been seeing or hearing things I hadn't no business to—some folks never do things right. That's me. I never told Old Man Wright about my seeing him there and he don't know it yet. But it wasn't so long after that he come to me, and he hadn't been shaved for four days, and he was looking kind of odd; and he says to me:

"Curly, we're up against it for fair!" says he.

"Why, what's wrong, Colonel?" says I, for I seen something was wrong all right.

He didn't answer at first, but sort of throwed his hand round to show I was to come along.

At last he says:

"Curly, we're shore up against it!" He sighed then, like he'd lost a whole trainload of cows.

"What's up, Colonel?" says I. "Range thieves?"

"Hell, no!" says he. "I wish 'twas that—I'd like it."

"Well," says I, "we got plenty of this water, and we branded more than our average per cent of calves this spring." For such was so that year—everything was going fine. We stood to sell eighty thousand dollars' worth of beef cows that fall.

He didn't say a word, and I ast him if there was any nesters coming in; and he shook his head.

"I seen about that when I taken out my patents years ago. No; the range is safe. That's what's the matter with it; the title is good—too good."

"Well, Colonel," says I, some disgusted and getting up to walk away, "if ever you want to talk to me any send somebody to where I'm at. I'm busy."

"Set down, Curly," says he, not looking at me.

So I done so.

"Son," says he to me—he often called me that along of me being his segundo for so many years—"don't go away! I need you. I need something."

Now I ain't nothing but a freckled cowpuncher, with red hair, and some says both my eyes don't track the same, and I maybe toe in. Besides, I ain't got much education. But, you see, I've been with Old Man Wright so long we've kind of got to know each other—not that I'm any good for divine Providence neither.

"Curly," says he after a while when he got his nerve up, "Curly, it looks like I got to sell out—I got to sell the Circle Arrow!"

Huh! That was worse than anything that ever hit me all my life, and we've seen some trouble too. I couldn't say a word to that.

After about a hour he begun again.

"I reckon I got to sell her," says he. "I got to quit the game. Curly, you and me has got to make a change—I'm afraid I've got to sell her out—lock, stock and barrel."

"And not be a cowman no more?" says I.

He nods. I look round to see him close. He was plumb sober, and his face was solemn, like it was the time I caught him looking in the trunk.

"That irrigation syndicate is after me again," says he.

"Well, what of it?" says I. "Let 'em go some place else. It ain't needful for us to make no more money—we're plumb rich enough for anybody on earth. Besides, when a man is a cowman he's got as far as he can go—there ain't nothing in the world better than that. You know it and so do I."

He nods, for what I said was true, and he knowed it.

"Colonel," I ast him, "have you been playing poker?"

"Some," says he. "Down to the Cheyenne Club."

"How much did you lose?"

"I didn't lose nothing—I won several thousand dollars and eight hundred head of steers last week," says he.

"Well, then, what in hell is wrong?" says I.

"It goes back a long ways," says he after a while, and now his face looked more than ever like it did when he was there a-going through them trunks. I turns my own face away now, so as not to embarrass him, for I seen he was sort of off his balance.

"It's her," says the old man at last.

I might have knew that—might have knew it was either Bonnie Bell or her ma that he had in his mind all the time; but he couldn't say a damn word. He went on after a while:

"When she was sick I begun to get sort of afraid about things. One day she taken Bonnie Bell by one hand and me by the other, and says she to me: 'John Willie'—she called me that, though nobody knew it maybe—'John Willie,' says she, 'I want to ask something I never dared ask before, because I never did know before how much you cared for me real,' says she. Oh, damn it, Curly, it ain't nobody's business what she said."

After a while he went on again.

"'Lizzie,' says I to her, 'what is it? I'll do anything for you.'

"'Promise me, then, John Willie,' says she, 'that you'll educate my girl and give her the life she ought to have.'

"'Why, Lizzie,' says I, 'of course I will. I'll do anything in the world you say, the way you ask it.'

"'Then give her the place that she ought to have in life,' she says to me."

He stopped talking then for maybe a hour, and at last he says again:

"Well, Curly, let it go at that. I can't talk about things. I couldn't ever talk about her."

I couldn't talk neither. After a while he kind of went on, slow:

"The kid's fifteen now," says he at last. "She's going to be a looker like her ma. It's in her blood to grow up in the cow business too—that's me. But she's got it in her, besides, like her ma, to do something different.

"I don't like to do my duty no more than anybody else does, but it shore is my duty to educate that kid and give her a chance for a bigger start than she can get out here. It was that that was in her ma's mind all the time. She didn't want her girl to grow up out here in Wyoming; she wanted her to go back East and play the game—the big game—the limit the roof. She ast it; and she's got to have it, though she's been dead more than ten years now. As for you and me, it can't make much difference. We've brought her up the best we knew this far."

"Well, you can't sell the Circle Arrow now," says I, "and I'll tell you why."

"Tell me," says he.

"Well, let's figure on it," says I. "It'll take anyways four years to develop Bonnie Bell ready to turn off the range, according to the way such things run. She'll have to go to school for at least four years. Why not let the thing run like it lays till then, while you send her East?"

"You mean to some girls' college?" says he. "Well, I've been thinking that all out. She'll have to go to the same kind of schools her ma did and be made a lady of, like her ma." He looks a little more cheerful and says to me: "That'll put it off four years anyways, won't it?"

"Shore it will," says I. "Maybe something will happen by that time. It don't stand to reason that them syndicate people will be as foolish four years from now as they are today; and like enough you can't sell the range then nohow." That makes us both feel a lot cheerfuller.

Well, later on him and me begun looking up in books what was the best college for girls, though none of 'em said anything about caring special for girls that knew more of horses and cows than anything else. We seen names of plenty of schools—Vassar and Ogontz and Bryn Mawr—but we couldn't pronounce them names; so we voted against them all. At last I found one that looked all right—it was named Smith.

"Here's the place!" says I to Old Man Wright; and I showed him on the page. "This man Smith sounds like he had some horse sense. Let's send Bonnie Bell to Old Man Smith and see what he'll do with her."

Well, we done that. Old Man Smith must of knew his business pretty well, for what he done with Bonnie Bell was considerable. She was changed when she got back to us the first time, come summer of the first year. I didn't get East and I never did meet up with Old Man Smith at all; but I say he must of knowed his business. His catalogue said his line was to make girls appreciate the Better Things of life. He spelled Better Things in big letters. Well, I don't know whether Bonnie Bell begun to hanker after them Better Things or not, but she was changed after that every year more and more when she come home. In four years she wasn't the same girl.

She wasn't spoiled—you couldn't spoil her noways. She was as much tickled as ever with the colts and the calves and the chickens and the alfalfa and the mountains; and she could still ride anything they brought along, and she hadn't forgot how to rope. Still, she was different. Her clothes was different. Her hats was different. Her shoes was different. Her hair was done up different. Somehow she had grew up less like her pa and more like her ma. So then I seen that 'bout the worst had happened to him and me that could happen. Them Better Things was not such as growed in Wyoming.

Now, Old Man Wright and me, us two, had brought up the kid. Me being foreman, that was part of my business too. We been busy. I could see we was going to be a lot busier. Before long something was due to pop. At last the old man comes to me once more.

"Curly," says he, "I was in hopes something would happen, so that this range of ours wouldn't be no temptation to them irrigation colonizers; I was hoping something would happen to them, so they would lose their money. But they lost their minds instead. These last four years they raised their bid on the Circle Arrow a half million dollars every year. They've offered me more money than there is in the whole wide world. They say now that for the brand and the range stock and the home ranch, and all the hay lands and ditches that we put in so long ago, they'll give me three million eight hundred thousand dollars, a third of it in real money and the rest secured on the place. What do you think of that?"

"I think somebody has been drunk," says I. "There ain't that much money at all. I remember seeing Miss Anderson, Bonnie Bell's teacher down at Meeteetse, make a million dollars on the blackboard, and it reached clear acrost it—six ciphers, with a figure in front of it. And that was only one million dollars. When you come to talking nearly four million dollars—why, there ain't that much money. They're fooling you, Colonel."

"I wisht they was," says he, sighing; "but the agent keeps pestering me. He says they'll make it four million flat or maybe more if I'll just let go. You see, Curly, we picked the ground mighty well years ago, and them ditches we let in from the mountains for the stock years ago is what they got their eyes on now. They say that folks can dry-farm the benches up toward the mountains—they can't, and I don't like to see nobody try it. I'm a cowman and I don't like to see the range used for nothing else. But what am I going to do?"

"Well, what are you going to do, Colonel?" says I. "I know what you'll do, but I'll just ast you."

"Of course," says he, "it ain't in my heart to sell the Circle Arrow—you know that—but I got to. Here's Bonnie Bell. She's finished—that is to say, she ain't finished, but just beginning. She's at the limit of what the range will produce for her right now. We got to move on."

I nodded to him. We both felt the same about it. It wasn't so much what happened to us.

"Well," says he, "we got to pick out a place for her to live at after we sell the range. I thought of St. Louis; but it's too hot, and I never liked the market there. Kansas City is a good cowtown; but it ain't as good as Chicago. I reckon Chicago maybe is as good a cowtown as there is."

"Well, Colonel," says I, "I reckon here's where I go West."

"You go where?" says he to me, sharp.

"West," says I.

"There ain't no West," says he. "Besides, what do you mean? What are you talking about, going anywheres?"

"You said you was going to sell the range," says I. "That ends my work, don't it? I filed on eight or ten homesteads, and so did the other boys. It's all surveyed and patented, and it's yours to sell."

He didn't say nothing for a while, his Adam's apple walking up and down his neck.

"You been square to me all your life, Colonel," says I, "and I can't kick. All cowpunchers has to be turned out to grass sometime and it's been a long time coming for me. I'm as old as you are, Colonel, and I can't complain."

"Curly," says he, "what you're saying cuts me a little more than anything ever did happen to me. Ain't I always done right by you?"

"Of course you have, Colonel. Who said you hadn't?"

"Ain't you always been square with me?"

"Best I knew how," says I. "I never let my right hand know what my left was doing with a running iron—and I was left-handed."

"That's right; you helped me get my start in the early days. I owe a lot to you—a lot more than I've ever paid; but the least I could do for you would be to give you a home and a place at my table as long as ever you live, and more wages than you're worth—ain't that the truth?"

"I don't know how you figure that," says I.

"Yes; you do, too, know how I figure that—you know there ain't but one way I could figure it. You stay with me till hell freezes under both of us; and I don't want to hear no more talk about you going West or nowheres else."

Folkses' Adam's apples bothers sometimes.

"We built this brand together," says he, "and what right you got to shake it now?" says he; me not being able now to talk much. "We rode this range, every foot of it, together, and more than once slept under the same saddle blanket. I've trusted you to tally a thousand head of steers for me a half dozen times a year. You've had the spring rodeo in your hands ever since I can remember. You've been one-half pa of that kid. Has times changed so much that you got a right to talk the way you're talking?"

"You're going back into the States, though, Colonel," says I. "They turn men out there when they're forty—and I'll never see forty again. I read in the papers that forty is the dead line back there."

"It ain't in Wyoming," says he.

"We won't be in Wyoming no more, there," says I.

He set and looked off across the range toward the Gunsight Gap, at the head of the river, and I could see him get white under his freckles. He was game, but he was scared.

"We can't help it, Curly," says he. "We've raised the girl between us and we've got to stick all the way through. You've been my foreman here and you got to be my foreman there in the city. We'll land there with a few million dollars or so and I reckon we'll learn the game after a while."

"I'd make a hell of a vallay, wouldn't I, Colonel?" says I.

"I didn't ast you to be no vallay for me," says he. "I ast you to be my foreman—you know damn well what I mean."

I did know, too, far as that's concerned, and I thought more of Old Man Wright then than I ever did. Of course it's hard for men to talk much out on the range, and we didn't talk. We only set for quite a while, with our knees up, breaking sticks and looking off at the Gunsight Gap, on top of the range—just as if we hadn't saw it there any day these past forty years.

I was plenty scared about this new move and so was he. It's just like riding into a ford where the water is stained with snow or mud and running high, and where there ain't no low bank on the other side. You don't know how it is, but you have to chance it. It looked bad to me and it did to him; but we had rid into such places before together and we both knew we had to do it now.

"Colonel," says I at last to him, "I don't like it none, but I got to go through with you if you want me to."

He sort of hit the side of my knee with the back of his hand, like he said: "It's a trade." And it was a trade.

That's how come us to move from Wyoming to Chicago, looking for some of them Better Things.

"Well, Curly," says Old Man Wright to me one day a couple of months after we had our first talk, "I done it!"

"You sold her?" says I.

"Yes," says he.

"How much did you set 'em back, Colonel?" says I; and he says they give him a million and a half down, or something like that, and the balance of four million and a quarter deferred, one, two, three.

That's more money than all Wyoming is worth, let alone the Yellow Bull Valley, which we own.

"That's a good deal of money deferred, ain't it, Colonel?" says I.

"Well, I don't blame 'em," he says. "If I had to pay anybody three or four million dollars I'd defer it as long as I could. Besides, I'm thinking they'll defer it more than one, two and three years if they wait for them grangers to pay 'em back their money with what they can raise.

"But ain't it funny how you and me made all that money? It's a proof of what industry and economy can do when they can't help theirselfs. When Tug Patterson wished this range on me forty years ago I hated him sinful. Yet we run the ditches in from year to year, gradual, and here we are!

"Well, now," he goes on, "they want possession right away. We got to pull our freight. You and me, Curly, we ain't got no home no more."

That was the truth. In three weeks we was on our way, turned out in the world like orphans. Still, Old Man Wright he just couldn't bear to leave without one more whirl with the boys down at the Cheyenne Club. He was gone down there several days; and when he come back he was hungry, but not thirsty.

"It's no use, Curly," says he. "It's my weakness and I shore deplore it; but I can't seem to get the better of my ways."

"How much did you lose, Colonel?" I ast him.

"Lose?" says he. "I didn't lose nothing. I win four sections of land and five hundred cows. I didn't go to do it and I'm sorry; because, what am I going to do with them cows?"

"Deed 'em to Bonnie Bell," says I. "Trust 'em out to some square fellow you know on shares. We may need 'em for a stake sometime."

"That's a good idea," says he. "Not that I'm scared none of going broke. Money comes to me—I can't seem to shoo it away."

"I never had so much trouble," says I, "but if you're feeling liberal give me a chaw of tobacco and let's talk things over."

We done that, and we both admitted we was scared to leave Wyoming and go to Chicago. We had to make our break though.

Bonnie Bell was plumb happy. She kept on telling her pa about the things she was going to do when she got to the city. She told him that, so far as she was concerned, she'd never of left the range; but since he wanted to go East and insisted so, why, she was game to go along. And he nods all the time while she talks that way to him—him aching inside.

We didn't know any more than a rabbit where to go when we got to Chicago; but Bonnie Bell took charge of us. We put up in the best hotel there was, one that looks out over the lake and where it costs you a dollar every time you turn round. The bell-hops used to give us the laugh quiet at first, and when the manager come and sized us up he couldn't make us out till we told him a few things. Gradual, though, folks round that hotel began to take notice of us, especial Bonnie Bell. They found out, too, like enough, that Old Man Wright had more money than anybody in Chicago ever did have before—at least he acted like he had.

"Curly," says he to me one day, "I got to go and take out a new bank account. I can't write checks fast enough on one bank to keep up with Bonnie Bell," says he.

"What's she doing, Colonel?" I ast him.

"Everything," says he. "Buying new clothes and pictures, and lots of things. Besides, she's going to be building her house right soon."

"What's that?" I says.

"Her house. She's bought some land up there on the Lake Front, north of one of them parks; it lays right on the water and you can see out across the lake. She's picked a good range. If we had all that water out in Wyoming we could do some business with it, though here it's a waste—only just to look at.

"She's got a man drawing plans for her new house, Curly—she says we've got to get it done this year. That girl shore is a hustler! Account of them things, you can easy see it's time for me to go and fix things up with a new bank."

So we go to the bank he has his eye on, about the biggest and coldest one in town—good place to keep butter and aigs; and we got in line with some of these Chicago people that are always in a hurry, they don't know why. We come up to where there is a row of people behind bars, like a jail. The jail keepers they set outside at glass-top tables, looking suspicious as any case keeper in a faro game. They all looked like Sunday-school folks. I felt uneasy.

Old Man Wright he steps up to one of the tables where a fellow is setting with eyeglasses and chin whiskers—oldish sort of man; and you knowed he looked older than he was. He didn't please me. He sizes us up. We was still wearing the clothes we bought in Cheyenne at the Golden Eagle, which we thought was good enough; but this man, all he says to us was:

"What can I do for you, my good people?"

"I don't know just what," says Old Man Wright, "but I want to open a account."

"Third desk to the right," says he.

So we went down three desks and braced another man to see if we please could put some money in his bank. This one had whiskers parted in the middle on his chin. I shore hated him.

"What can I do for you, my good man?" says he.

"I was thinking of opening a account," says Old Man Wright.

"What business?" says he.

"Poker and cows," says Old Man Wright.

The fellow with whiskers turned away.

"I'm very busy," says he.

"So am I," says Old Man Wright. "But what about the account?"

"You'd better see Mr. Watts, three windows down," says the man with the whiskers. So we went on a little farther down.

"How much of a deposit did you want to make, my good friend?" ast this new man, who had little whiskers in front of his ears. I didn't like him none at all.

Old Man Wright he puts his hand in his pocket and pulls out a lot of fine cut, and some keys and a knife and some paper money, and says he:

"I don't know—it might run as high as three hundred dollars."

The man with the little whiskers he pushes back his roll.

"We couldn't think of opening so small a account," says he. "I recommend you to our Savings Department, two floors below."

Old Man Wright he turns to me and says he:

"Haven't they got the fine system? They always have a place for your money, even if it's a little bit."

"Hold on a minute," says he after a while and pulls a card out of his pocket. "Take this in to your president and tell him I want to see him."

That made the man with the little whiskers get right pale. His mouth got round like that of a sucker fish.

"What do you mean?" says he.

"Nothing much," says Old Man Wright. "I may have overlooked a few things. I was wrong about that three hundred dollars."

He flattens out on the table a mussed-up piece of paper he found in his side pocket.

"It wasn't three hundred dollars at all, but three hundred thousand dollars," says he. "I forgot. Go ask your president if he'll please let me open a account, especial since I bought four thousand shares in this bank the other day when I was absent-minded—my banker out in Cheyenne told me to do it. You can see why I come in, then—I wanted to see how the hands in this business was carrying it on, me being a stockholder. Now run along, son," says he, "and bring the president out here, because I'm busy and I ain't got long to wait."

And blame me if the president didn't come out, too, after a while! He was a little man, yet looked like he'd just got his suit of clothes from the tailor that morning, and his necktie too—white and rather soft-looking; not very tall, but wide, with no whiskers. I didn't have no use for him at all.

The president he came smiling, with both his hands out. He certainly was a glad-hand artist, which is what a bank president has to be today—he's got to be a speaker and a handshaker. The rest don't count so much.

He taken us into his own room. I never had knowed that chairs growed so large before or any table so long; but we set down. That president certainly knew good cigars.

"My dear Mr. Wright," says he, "I'm profoundly glad that you have at last came in to see us. I knew of your purchase in our institution and we value your association beyond words. With the extent of your holdings—which perhaps you will increase—you clearly will be entitled to a place on our board of directors. I'm a Western man myself—I came from Moline, Illinoy; and perhaps it will not be too much if I ask you to let me have your proxy, just as a matter of form." He talks like a book.

We had some more conversation, and when we went out all the case keepers stood up and bowed, one after the other. We didn't seem to have no trouble opening a account after that.

"The stock in this bank's too low," says Old Man Wright to me on the side. "That's why I bought it. They're going to put it up after a while; and when they start to put things up they put 'em farther when you begin on the ground floor. Do you see?"

I begun to think maybe Old Man Wright was something more than a cowman, but I didn't say nothing. We went back to the hotel and he calls in Bonnie Bell to our room.

"Look at me, sis," says he. "Is they anything wrong with me?"

She sits down on his knee and pushes back his hair.

"Why, you old dear," says she, "of course they ain't."

"Is they anything wrong with my clothes or Curly's?" he says.

"Well now——" she begins.

"That settles it!" says he; and that afternoon him and me went down to a tailor.

What he done to each of us was several suits of clothes. Old Man Wright said he wanted one suit each of every kind of clothes that anybody ever had been knew to wear in the history of the world. I was more moderate. I never was in a spiketail in my whole life and I told him I'd die first. Still, I could see I was going to be made over considerable.

As for Bonnie Bell, when she went down the avenue, where the wind blows mostly all the time, she looked like she'd lived there in the city all her life. She always had a good color in her cheeks from living out-of-doors and riding so much, and she was right limber and sort of thin. Her hat was sort of little and put some on one side. Her shoes was part white and part black, the way they wore 'em then, and her stockings was the color of her dress; and her dress was right in line, like the things you saw along in the store windows.

It was winter when we hit Chicago and she wore furs—dark ones—and her muff was shore stylish. When she put it up to the side of her face to keep off the wind she was so easy to look at that a good many people would turn round and look at her. I don't know what folks thought of her pa and me, but Bonnie Bell didn't look like she'd come from Wyoming. Once two young fellows followed her clear to the door of the hotel, where they met me. They went away right soon after that.

Bonnie Bell just moved into Chicago like it was easy for her. As for Old Man Wright, about all him and me could do was to go down to the stockyards and see where the beef was coming from. We looked for some of our brand, and when he seen some of the Circle Arrow cows come in he wouldn't hardly talk to anybody for two or three days.

I never did see where Bonnie Bell's new house was, because she said it was a secret from me. Her pa told me that he paid round two hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars for the land, without no house on it.

"Why, at that," says I, "you'll be putting up a house there that'll cost over six thousand dollars, like enough!"

Bonnie Bell hears me and says she:

"I shouldn't wonder a bit if it would cost even more than that. Anybody that is somebody has to have a good house, here in Chicago."

"Are we somebody, sis?" says Old Man Wright, sudden.

"Dear old dad!" says she, and she kisses him some more. "We'll be somebody before we quit this game—believe me!"

"Curly," says the old man to me soon after, "that girl's got looks—Lord! I didn't know it till I seen her all dressed up the way she is here. She's got class—I don't know where she got it, but she has. She's got brains—Lord knows where she got them; certain not from me. She's got sand too—you can't stop her noways on earth. If she starts she's going through. And she says she only come here because she knew I wanted to!" says he.

"What's the difference?" I ast him. "We fooled her, didn't we?"

"Maybe," says he. "I ain't shore."

Well, anyway, this is what we'd swapped the old days out on the Yellow Bull for. We'd done traded the mountains and the valley and the things we knew for this three or four rooms at several hundred dollars a month in a hotel that looked out over the water, and over a lot of people on the keen lope, not one of them caring a damn for us—leastways not for her pa or me.

I never had lived in town this long, not in all my life before, and, far as I know, the boss hadn't, neither. We wasn't used to this way of living. We'd been used to riding some every day. Out in the parks, even in the winter, once in a while you could see somebody riding—or thinking they was riding, which they wasn't.

One day Old Man Wright, come spring, he goes down to the stockyards and buys a good saddle horse for Bonnie Bell to ride. It cost him twenty-five dollars a month to keep that horse, so he would eat his head off in about three months at the outside. Old Man Wright tells me that I'll have to ride out with the kid whenever she wanted to go. That suited me. Of course that meant we had to buy another horse for me. That made the stable bill fifty dollars a month. I never did know what we paid for our rooms at the hotel, but it was more every month than would keep a family a year in Wyoming.

Bonnie Bell she could ride a man's saddle all right, and she had a outfit for it. When it got a little warmer in the spring we used to go in the parks every once in a while. One day we rid on out into a narrow sort of place along the lake. There was houses there—a row of them, all big, all of stone or brick; houses as big as the penitentiary in Wyoming and about as cheerful.

We stopped right in front of a big brick-and-stone house, which had trees and flower beds and hedges all along; and says she:

"Curly, how would you like to live in a house like that?"

"I wouldn't live in the damn place if you give it to me, Bonnie Bell," says I, cheerful.

She looked at me kind of funny.

"That's the kind of a house the best people have in this town," says she. "For instance, that house we're looking at looks as though the best architects in town had designed it. That place, Curly, cost anywhere from a half to three-quarters of a million, I'll betcha."

"Well, that's a heap more money than anybody ought to pay for a place to live in," says I. "They ought to spend it for cows."

"But it fronts the lake," says she, "and it's right in with the best people."

"Is that so?" says I. "Then here is where we ought to of come—some place like that; for what we're here for is to break in with the best people. Ain't that the truth, Bonnie Bell?"

"Maybe," says she after a while—"bankers, I suppose, merchants, wholesale people—hides, leather, packing——"

"And not cowmen?" says I.

"Certainly not!" says she. "To be the best people you must deal in something that somebody else has worked on—you must handle a manufactured product of some kind. You mustn't be a producer of actual wealth."

"Sho! Bonnie Bell," says I, "if you're in earnest you're talking something you learned at Old Man Smith's college. I don't know nothing about them things. Folks is folks, ain't they? A square man is a square man, no matter what's his business."

"It's different here," says she.

"Well, now, while we're speaking about houses," says I, us setting there on our horses all the time and plenty of people going by and looking at us—or leastways looking at her—"why don't you tell me where your house is going to be at? You never did show it to me once."

"I'm not going to, Curly," says she. "That's going to be a secret. Of course dad knows where it is; but as for you—well, maybe we will get into it by Christmas."

"Now, for instance," says I—and I waves my hand toward a place that was just starting alongside this big house we'd been looking at—"it like enough taken a year or so to get this here place as far along as it is."

"Uh-huh!" says she.

So then we turned away and rid back home. When we got back to the hotel we found Old Man Wright setting in a chair, with his legs stuck out and his hands in his pockets, looking plumb unhappy.

"What's the matter, dad?" ast Bonnie Bell. "Have you lost any money or heard any bad news?"

"No, I ain't," says he. "It all depends on what people need to make them happy."

"Well," says Bonnie Bell—her face was right red from the ride we had and she was feeling fine—"I'm perfectly happy, except there ain't any place you can ride a horse in this town and have any fun at it, the roads are so hard. Everybody seems to go in motor cars nowadays, anyways."

"Huh!" says her pa. "That's what I should think." He holds up a newspaper in front of him. "When I first come here," says he, "I seen that everybody was riding in cars, and I figured that more of them was going to; so I taken a flyer, sixty thousand dollars or so, in some stock in a company that was making one of them cars that sells right cheap. Now them people have gave me eighty per cent stock for a bonus and raised the dividend to twenty-five per cent a year. She's going to make money all right. Shouldn't wonder if that stock would more than double in a year or so."

"For heaven's sake, Colonel," says I, "ain't there nothing a-tall that you can get into without making money?" says I.

"No, there ain't," says he, sad. "It happens that way with some folks—I just can't help making it; yet here I am with more money than any of us ought to have. But I had to do it," says he to Bonnie Bell. "I get sort of lonesome, not having much to do; so that I have to mix up with something. Cars, sis?" says he. "Why, let me give you two or three of the kind our company makes."

"No you don't!" says Bonnie Bell. "I want one that——"

"Huh! that costs about eight or ten thousand dollars, maybe?"

"Well," says she, "you have to sort of play things proportionate, dad; and I think that kind of a car is just about proportionate to what you and me is going to do in this little town when we get started."

She turns and looks out the window some more. That was a way she had. You see, all these months we'd been there already we didn't know a soul in that town. Womenfolks always hate each other, but they hate theirselves when other womenfolks don't pay no attention to them. Bonnie Bell was used to neighbors and she didn't have none here; so, though she was busy buying everything a girl couldn't possibly want, she didn't seem none too happy now.

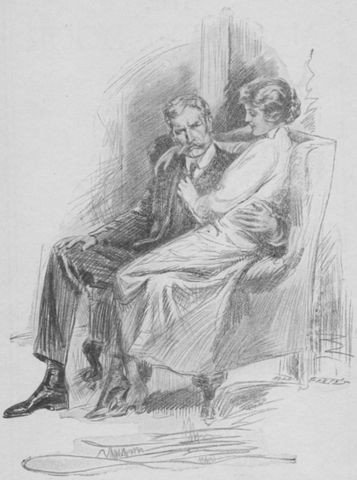

"What's wrong, sis?" says her pa after a while, pulling her over on his knee. "Ain't me and Curly treating you all right?"

She pushed back his face from her and looks at him; and says she, right sober:

"Dad," she says, "you mustn't ever really ask me that. You're the best man in all the world—and so is Curly."

"No, we ain't," says he. "The best man hasn't really showed yet for you, sis."

"Why, dad," says she, "I'm only a young girl!"

"You're the finest-looking young girl in this town," says he, "and the town knows it."

"Huh!" says she, and sniffs up her nose. "It don't act much like it."

"If I can believe my eyes," says her pa, "when I walk out with you a good many people seem to know it."

"That don't count, dad," says she. "Men, and even women, look at a girl on the street—men at her ankles and women at her clothes; but that doesn't mean anything. That doesn't get you anywhere. That isn't being anybody. That doesn't mean that you are one of the best people."

"And you want to be one of the best people—is that it, sis?"

She set her teeth together and her eyes got bright.

"Well," says she, "we never played anything for pikers, did we, dad?"

Then them two looked each other in the eyes. I looked at them both. To me it seemed there certainly was going to be some doings.

"Go to it, sis!" says her pa. "You've got your own bank account and it's bigger than mine. The limit's the roof.

"Speaking of limits," says he, "reminds me that the president of our bank he got me elected to the National League Club here in town; him having such a pull he done it right soon—proxies, maybe. I've been over there this afternoon trying to enjoy myself. Didn't know anybody on earth. One or two folks finally did allow me to set in a poker game with them when I ast. It wasn't poker, but only a imitation. I won two hundred and fifty dollars and it broke up the game. If a fellow pushes in half a stack of blues over there they all tremble and get pale. This may be a good town for women, but, believe me, sis, it's no town for a real man."

"Well, never mind, dad," says she. "If you get lonesome I'll have you help me on the house. We'll have to get our servants together. For instance, we've got to have a butler—and a good one."

"What's a butler?" says I.

"He stands back of your chair and makes you feel creepy," says Old Man Wright. "We've got to have one of them things, shore. Then there's the chauffore for the car when you get it, and the cook. That's about all, ain't it?"

"That's about the beginning," says Bonnie Bell. "You have to have a cook and a kitchen girl and two first-floor maids and two upper-floor maids and a footman."

"Well, that will help some," says her pa. "I've been bored a good deal and lonesome, but maybe, living with all them folks, somebody will start something sometime. When did you say we could get in?"

"They tell me we'll be lucky if we have everything ready by Christmas," says Bonnie Bell.

"It looks like a merry summer, don't it?" says he sighing.

"And like a hell of a Merry Christmas!" says I.

How we spent all that spring and summer I don't hardly see now. We was the lonesomest people you ever seen. Old Man Wright he'd go over to his new club once in a while and sometimes out to the stockyards, and sometimes he'd fuss round at this or that. Bonnie Bell and me we'd go riding once in a while when she wasn't busy, which was most of the time now. She had a lot of talking to do with the folks that was building her house and furnishing it—she never would tell me where it was.

Well, it got cold right early in the winter. It was awful cold, colder than it gets in Wyoming. When it gets cold in Chicago the folks say: "This certainly is most unusual weather!"—just like we do when there is a blizzard out in Wyoming. Old Man Wright and me we thought we'd freeze, because, you see, we had to wear overcoats like they had in the city, and couldn't wear no sheep-lined coats like we would have wore on the range.

"Well, you see," said Bonnie Bell when we complained to her, "when we get our motor car running we won't have to walk. Nobody that amounts to anything walks in the city. Our best people all have cars; so they don't need sheepskin coats. Our car will be here any time now; so we can see more of the city and be more comfortable than you can on horseback. Nobody rides horseback except a few young people in the parks in the summertime—I found that out."

"Don't our best people do that now?" ast her pa.

"Some, but not many," says she. "There's a good many people that wants you to think they're the best people; but they ain't. You can always tell them by the way they play their hands. Most of the people I've seen riding in the parks is that sort—they want you to look at them when they ride because they're perfectly sure they're doing what our best people are doing. You can tell 'em by their clothes, whether they are riding or walking. It's easy to spot them out."

"I wonder," says I, "if they can spot out your pa and me?"

She comes over and rumples up my hair like she sometimes did.

"You're a dear, Curly!" says she.

"I know that," says I; "but don't muss up my new necktie, for I worked about a hour on that this morning, and at that it's a little on one side and some low. But I'm coming on," says I.

Now, Old Man Wright, when he wore his spiketail coat, he had the same trouble with his tie that I had with mine. He told his tailor about that one time, but his tailor told him that the best people wore them that way—mussed up and careless. Natural like it was a hard game to play, because how could you tell when to be careless and when not to be? But, as I said, we was coming on.

Mr. Henderson—he was the hotel manager and a pretty good sport too—he sort of struck up a friendship with Old Man Wright, and you couldn't hardly say we didn't have no visitors, for he come in every once in a while and was right nice to us. You see, what with Old Man Wright wearing his necktie careless and Bonnie Bell dressing exactly like she come out of a fashion paper, if it hadn't been for me our outfit might of got by for being best people, all right. Like enough I queered the game some; but Henderson he didn't seem to mind even me.

The day before Christmas Bonnie Bell said her new house was all done and all furnished, everything in, servants and all, ready for us to move in that very night and spend Christmas Eve there. But she says Mr. Henderson, the manager of the hotel, wanted us to eat our last dinner that night in the hotel before we went home. To oblige him we done so.

He taken us in hisself that night. The man at the door snatched our hats away, but he taken Bonnie Bell's coat—fur-lined it was and cost a couple of thousand dollars—over his arm, and he held back the chair for her. There was flowers on the table a plenty. I reckon he fixed it up. There wasn't no ham shank and greens, but there was everything else.

I shouldn't wonder if some of the best people was there. Everybody had on the kind of clothes they wear in the evening in a town like this—spiketails for the men, and silk things, low, for the womenfolks. Old Man Wright, with his red moustache, a little gray, him tall, but not fat, and his necktie a little mussed up, was just as good-looking a man as was in the place.

As for Bonnie Bell—well, I looked at our girl as I set there in my own best clothes and my necktie tied the best I knew how, and, honest, she was so pretty I was scared. The fact is, pretty ain't just the word. She was more than that—she was beautiful.

Her dress was some sort of soft green silk, I reckon, cut low, and her neck was high and white, and her hair was done up high behind and tied up somehow, and her chin was held up high. She had some color in her face—honest color—and her eyes was big and bright. Her arms was bare up above where her gloves come to. She didn't have on very many rings—though, Lord! if she wanted them she could of had a bushel. She didn't have on much jewelry nowhere; but I want to tell you everybody in that room looked at her all they dared.

I looked at her and so did her pa. I don't know as you could say we both was proud—that ain't the right word for it. We was both scared. It didn't seem possible she could be ours. It didn't seem possible that us two old cowmen had raised her that way out on the range and that she had changed so soon. She must of had it in her—her ma, I reckon.

There was a table not very far from ours, just across the first window, where there was a old man and a old woman and a young man. They seen us all right. I seen the young man looking at Bonnie Bell two or three times, always looking down when he seen I noticed. He was a good-looking young man and dressed well, I suppose, for all the men was dressed alike. His necktie was tied kind of mussy and careless, like Old Man Wright's, and he didn't have to keep pushing at his shirt. Did Bonnie Bell notice him? Maybe she did—you can't tell about womenfolks; their eyes is set on like a antelope's and they can see behind theirself.

"That's Old Man Wisner," says Henderson, the hotel manager, quiet, to us, leaning over and pretending like he was fixing our flowers some more. "Mrs. Wisner and young Mr. James Wisner are with him. You know, he is one of the richest men here in Chicago—packing and banking, and all that sort of thing. They are among our best people. They live up in Millionaire Row."

"Yes, I know," says Bonnie Bell.

From where I set I could see them Wisners over at the other table. The old man was big, with gray whiskers and gray hair, rather coarse. He had big eyebrows and his eyes was kind of cross-looking, like his stomach wasn't right. He was a portly sort of man—you've seen that kind. Some is bankers and some packers and some brewers; they all look alike, no matter what they are. They can't ride or walk.

This old party he didn't seem to be paying much attention to his wife, and I don't know as I blame him. She may have had some looks once, but not recent. They wasn't happy.

After a while the folks at that table got up and went on out before we was done with our dinner, which was going strong at the end of a couple of hours—there wasn't anything in the whole wide world we didn't have to eat except ham shank and greens. At that, we had a right good time.

By and by it got to be maybe eleven o'clock, and Bonnie Bell turns down her long white gloves, which she had tucked the hands of them back into the wrists.

"Shall I call your car, Mr. Wright?" ast the manager, Mr. Henderson.

"I don't know," says Old Man Wright. "Have we got a car, sis?"

"Yes, papa," says she—she mostly said "papa" when folks was round; don't overlook it that Old Man Smith turned out girls with real class. She didn't talk like her pa and me neither.

"Yes, papa," says she now. "I was going to surprise you about our car; it's been on hand for a week. I employed a driver and told him to be ready for us about now." You see all our things had gone out to the new house.

We all three of us helped Bonnie Bell on with her coat. She picked up her muff and we all went out. I don't think any man in the place that had brass buttons forgot that Christmas Eve.

The tall man in front at the door, like a drum major in a band, he knew us well enough by now; he opens the door for us and we stand there, looking out.

I said it was cold in Chicago and it was shore cold that night. It was snowing—snow coming in off the lake slantwise, like a blizzard on the plains. You couldn't hardly see across the walk. Out beyond the awning, which covered the sidewalk, we could see our new car—a long, shiny one with lights inside and lamps all over it, red, white and blue, or maybe green. There was a couple of men on the front seat outside—I don't know when the kid had hired them. They was both wrapped up in big fur overcoats, which they certainly did need that night, since they couldn't ride in the e-limousine, like us.

Bonnie Bell walks across the sidewalk now, under the awning, with her muff up against her face, bending over against the storm. She looks up, after she has said good-by to Mr. Henderson, who run out with us, laughing and saying "Merry Christmas!"—she just looks up at the man on the seat, and says she: "Home, James!"

I reckon the man must of been new that she had hired. He looks round at first, as if he was trying to read our brand. Then all at once, sudden, he jumps down offen the seat, touches his cap and opens the door.

We all got in and said good-by to the hotel where we'd been living so long. The chauffore touches his hat again, shuts the door and climbs back in his seat. He turned that long car round in one motion in the street. The next minute we was out on the avenue, away from the hotel, and right in the middle of that row of lights several miles long, where the bullyvard is at, along the lake there. He turns her north on the bullyvard, without a skip or a bobble, and she runs smooth as grease. I seen Bonnie Bell was certainly a good judge of a car, like she was of a horse or anything else.

"Daughter," says Old Man Wright to her after a time—and he didn't usual call her that—"you're a wonder to your dad tonight! Where did you get it? Where did you learn it?"

She looks up at him quick from her muff, plumb serious, and just put out her hand on his, in its white glove.

We moved right along up the avenue, along a little crooked street or so, round a corner and over the bridge; and then we come out where the lights was in a long row again, and we could hear the roar of the lake right close to the road.

"Where are you taking us, kid?" says I after a while, seeing that her pa wasn't going to say nothing, nohow.

She only smiled.

"Wait, Curly; you'll see the new ranch house before so very long."

By and by we was right at the lower end of that long row of big houses that cost so much money, where the best people live—Millionaire Row, they called it then.

I knew where we was. After a while we come right to the place where Bonnie Bell and me once had set on our horses and looked out at a new house that wasn't finished, but was just beginning. It was done now—all complete, from top to bottom, right where the foundations had been last spring! I could see where the walks was laid out and some trees had been planted that fall—big ones, as though they had always growed there. Here and there was statues, women mostly and looking cold that night.

On behind you could see the line of the low buildings, like the outlying barns of the home ranch on the Yellow Bull; but this house stood there just inside, where the lake come in rolling and roaring, and fronted right on this avenue, where our best people lived. It was stone, three stories or more, maybe, with a place for buckboards to drive under and a stone porch over the front door, and a walk and steps. And it was all lit up from top to bottom; all the windows was bright.

We wasn't cold or wet or tired, us three, but we wasn't feeling good—not one of us. Now when we stopped there for some reason and looked at all them red lights shining, I sort of felt a wish that I could see a light shining in some home ranch once more, like I had so often out on the Yellow Bull. I set there looking at that place, all lit up for somebody, all waiting for somebody; and for a time I forgot where I was—forgot even that the car had stopped.

I turns round; and there was Bonnie Bell pulling her coat up round her neck and fixing her hands in her muff, and her pa was buttoning up his coat. Just then, too, I seen the chauffore jump down offen the front seat. He comes round to the door, right where the walk was that led up to this new big house, and he opens the door and touches his hat, and stands there, waiting.

What with their laughing and pulling at me, and me sort of hanging back, we kind of forgot it was Christmas Eve. Old Man Wright thought of it, sudden; and he turns back to the man, who still stood at the door looking after Bonnie Bell and us as though we'd forgot something. He puts his hand in his waistcoat pocket and hauls out a ten-dollar gold piece, and puts it into the hand of this new chauffore of ours.

"Here you go, son," says he. "Merry Christmas! And I hope you'll take good care of my daughter."

The new chauffore, standing there in the snow—he was tall and a right good-looking chap too—he touches his cap.

"Thank you, sir," says he.

I seen the car move on away. It didn't turn in at our alley, but went on to the next gate, because our road wasn't quite finished yet. A minute afterward Bonnie Bell had me inside the door in the hall and was kissing us both, right in front of a sad-looking man in clothes like ours.

We stood for just a minute near the big door, and before we got it shut she looked out once more into the night, with the lights shining all through the snow, and the trees looking white and thin in the drift.

"Call the chauffore in and have him get a drink," says Old Man Wright. "That was a cold ride."

But by this time he was gone; so we all turns back to wrastle with this sad man, who evident was intending to mix it with us.

When all three of us—Old Man Wright and Bonnie Bell and me—went inside the door of that big new house we stood there for a minute or so; and at first I thought we had got into the wrong place—especial since that sad man looked like he thought so too.

It was all lit up inside and you could see 'way back into the hall—little carpets of all sorts of colors laying round, and pictures on the wall, and a fire 'way on beyond somewhere in a grate. I never seen a hotel furnished better.

Old Man Wright was like a man that's won a elephant on a lottery ticket. Bonnie Bell looks at him and looks at me like she missed something. On the whole, I reckon we was the three lonesomest, scaredest, unhappiest people in all that big town—it was Christmas Eve too!

There was a lot of other people in a row standing down the hall, back of this sad man. He located us at last and began to help Old Man Wright take off his overcoat—and me too; but I wouldn't let him. I wasn't sick or nothing. So we stood there a little while, dressed up and just come to our new home ranch.

"That will do, William," says Bonnie Bell to the sad man.

"Father," says she, and she leads him to the row of folks in the hall, "these are all our people that I have engaged. This is Mary, our cook; and Sarah, the first maid. Annette is going to be my maid."

Well, she went down the line and introduced us to a dozen of 'em, I reckon. I just barely did know enough not to shake hands. Some of 'em touched their foreheads and the girls bobbed. They didn't talk none and they didn't shake hands.

By now Bonnie Bell's maid had her coat over her arm and them two was starting upstairs.

"I'll be back in a minute, dad," says she. "William will take you and Curly into your room."

The sad man he walks off down the hall, us following, and we come to a place right in the center of the house—and he left us there. We stopped when we went through the door.

What do you know? Bonnie Bell had fitted up that room precisely like the big room in the old home ranch! All our old things was there—how she got them I never knew. There was the old table, with the pipes and papers on it, and tobacco scattered round, and bottles over on the shelf, and a bridle or so—just the same place all the way through. She even had the stones of the old fireplace brought on, one nicked, where Hank Henderson shot the cook once.

"Look-a-here, Curly," says Old Man Wright after a while.

He leads me over to the corner of the room, aside of the fireplace. Dang me, if there wasn't our two old saddles, wore slick and shiny! Old Man Wright stands there in his spiketail coat, and he runs his hand down that old stirrup leather a time or two; and for a little while he can't say nothing at all—me neither.

"Ain't she some girl, Curly?" says he after a while.

"She's the ace, Colonel," says I.

"Ain't a thing overlooked," says he, thoughtful, walking round the place, his hands in his pockets.

By and by he come up to half a bottle of corn whisky—the same one that had stood on the table out on the Circle Arrow. He picks it up and pours hisself out a drink, thoughtful, and shoves it over to me.

"Every little thing!" says he. "Not a thing left out! It's the same place. Gawd bless the girl, anyways! I don't think I could of stood it at all if she hadn't fixed up this room for you and me. I was just going to stampede."

"Well, Colonel," says I, "here's looking at you! I see we've got a place where we can come in and unbuckle. It makes it a heap easier. I wasn't happy none at all before now."

"She done it all herself," says her pa, setting his glass down and looking round the room once more. "I give her free hand. The architect had marked this place 'Den,' I reckon. Huh! I don't call it a den—I call it home, sweet home. If it wasn't for this room," says he, "this would be one hell of a Christmas, wouldn't it, Curly? But never mind; we're going to break into this town, or get awful good reasons why."

"You reckon we can, Colonel?" says I.

"Shore, we can!" says he. "We got to! Don't she want it?"

"For instance," says I, "what's the name of our neighbors over next door to us, you reckon?"

"That's where Old Man Wisner lives," says he, grinning. "Them was the folks that set over at the table that Henderson pointed out to us tonight. He's the biggest packer in Chicago, president or something in about all the banks and everything else—there ain't no better people than what the Wisners are. And don't we live right next door to 'em? Can you beat it? That's why the land cost so much.

"Wisner didn't want us to buy this place; he wanted to buy it hisself, but buy it cheap. It was him or me, and I got it. Still, when I want to be neighbor to a man I'm going to be a neighbor whether he likes it or not."

"You reckon they'll like us?" says I.

"They got to," says he.

We was standing up, our glasses in hand, looking out through the door down the hall to where things was all bright and shiny; and just then we heard Bonnie Bell come down the stairs and call out:

"Oo-hoo, dad!"

We raises our glasses to her when she come in the door. She had took off the clothes she wore down at the hotel and had on something light and loose, silk, better for wearing in the house. The house was all warm, too, and in our fireplace, the old smoky one, some logs was burning right cheerful.

It was a new sort of Christmas to us, but we lived it down. The next morning we all acted as much like kids as we could, which is all there is to any Christmas. My socks was full of candy, and Old Man Wright he had a Teddy bear in his—part ways anyhow. Then Bonnie Bell she give him a new gold watch with bells in it, and me a couple of pins for my necktie. I never could get 'em in right.

After a while we come down to breakfast. We was in a big room that faced toward the Wisners' and likewise toward the lake. I reckon you could see forty miles up and down from where we set eating. It was warm in the room, though there wasn't much fire, and we all felt comfortable.

You could see out our windows right over the lot of the Wisners'; we could see into their house same as they could see into ours. There was a garridge set back toward the lake, same as ours, about on the same line, and beyond that you could see a boathouse. They had trees in their yard like ours, but ours was almost as big, though just planted. You could see where our flower beds was laid out, and the lines of little green trees all set in close together. On beyond the Wisners' you could see a whole row of other houses, all big and fine like theirs and ours.

All the whole country was covered with snow that morning. The wind was still blowing and the lake coming in mighty rough; you could hear the noise of it through the windows. It looked mighty cold outside and it was cold. You can freeze to death respectable in Wyoming, but in Chicago you keep on freezing and don't freeze to death, but wish you would, you are that cold.

Well, like I said, it was warm in the big room where we et. Bonnie Bell had a couple of yellow canary birds which was able to set up and sing, which Old Man Wright said was almost more than he could do hisself. Breakfast come on a little at a time—you couldn't tell how much of it there was going to be; but it made good, though it didn't start out very strong. By and by it got round to ham and aigs, which made us feel better. I never tasted better coffee; it was better than anything we had on the Yellow Bull. Ours out there was mostly extract, in pound packages—beans, I think, maybe.

"How do you like our new house, dad?" says she.

"They can't beat it, Bonnie Bell," says he.

"Dad; dear old dad!" says she. "I'm so glad you like it. I done it all for you."

"How do you mean?" says he.

"Why, of course, you know what a sacrifice it was for me to come here and leave the old place! But I seen you wanted it. If I thought it wasn't all right I believe it would break my heart."

"I know it," says he. "I know what a sacrifice you made when you come here on my account. If anything comes out wrong for you because of that sacrifice it shore would break my heart. 'Button, button,' says he, 'who's got the sacrifice?' If you leave it to me I'd say it was Curly, and not neither of us. Forget it, sis, and have another warfle."

"How do you like the place, Curly?" says she to me.

"I never seen anything like it," says I. "Like enough you paid too much though. I bet you paid two or three thousand dollars for this land—you was fooling when you said over two hundred thousand; and there ain't enough of it to rope a cow on at that. You could have bought several sections of real land for the same money; and how many cows this here house cost there can't nobody figure."

About then I heard a noise out in the street. Four or five people—Dutch, maybe—was playing in a band out there in front of the Wisners'. A man come out and shooed 'em away. They stood out in front of our place then and kept on playing. It seems like you can't eat in Chicago without some one plays music around.

"Here; take 'em out some money, William," says Old Man Wright. "It's Christmas."

They played some more then, and every morning since. I always hated 'em and I reckon everybody else did along in there, but there didn't seem to be no way to run 'em off.

"Well," says Old Man Wright when we finished our breakfast, "what are we going to do today, sis?" says he. "It's good tracking snow, but there ain't nothing to track. There ain't no need to see how the hay's holding out or to wonder if the cows can break through the ice to get at water. There ain't no horses in the barns. We ain't got a single thing to do—not even feed the dogs."

Bonnie Bell was reading in the paper which William, the sad man, had put by our plates. Her eyes got kind of soft and wetlike.

"I'll tell you what we can do, dad," says she. "Look at this list of poor people here in town that ain't got no Christmas."

"I've got you, sis," says he. "William, go tell the driver to bring the big car round; and tell the cook to get several baskets, full of grub—we're going to have a little party."

Well, by and by the chauffore brought the car round in front and we went out; and William and the others loaded her up with baskets. The chauffore was looking kind of pale and shaky. He seemed to have something on his mind.

"I hope you'll excuse me, sir," says he, touching his hat to Old Man Wright. "I didn't mean to be late; but, you see, it was Christmas Eve——"

"Why, that's all right," says Old Man Wright to him. "Don't mention it—Christmas is due to come once a year anyhow."

"I'll not let it occur again," says the chauffore, touching his hat again.

"What? Christmas?" says he. "You can't help it."

The man looked at him kind of funny. I knew then he'd been celebrating the night before, and I was right glad he hadn't begun to celebrate until he'd drove us home, for he was jerky yet.

Christmas is a time when folks ought to be happy. We wasn't happy none that day. I never seen before what it was to be real poor. Here in this town, where there is so much money, it seemed like there was hundreds and thousands of people hadn't saw a square meal in their whole lives. You couldn't hardly stand it to see 'em—at least I couldn't. We spent our day that way—our first Christmas in town—trying to feed all the hungry people there was; and we couldn't. It was the saddest Christmas I ever had in all my life.

That night Old Man Wright and me didn't stop to put on our regular eating clothes, as Bonnie Bell said we ought to, and we all set down in her dining-room for dinner, feeling kind of thoughtful and thinking of how many people wasn't going to get no such a dinner that night. As for us, we had plenty; and, believe me, there was something which filled a long-felt want for Old Man Wright and me. What do you think? Why, ham shank and greens!

"Sis," says her pa, "you certainly are thoughtful."

We could see out our windows over into the Wisners' windows—it seemed like they had forgot to pull down their blinds, same as we had. They didn't seem to be nobody at home, only one young man. He come in all by hisself, all dressed up, and there was three men waiting on him at the table. At length I calls attention to this, and Bonnie Bell turns her head and looks across.

"William," says she, "draw the blinds; and be more careful after this."

Well, things rocked along this way and we got through the winter someways, though every once in a while I taken a cold along of being shut up so much. There wasn't nowhere to go and nothing to do except to read the papers and wish you was dead.

Old Man Wright couldn't stand it no more; so he goes downtown and rents him a fine large office in a big building, with long tables with glass on top, and big chairs, something like in a bank. He didn't put no business sign on the door—just his name: J. W. Wright.

I'm lazy enough for anybody, like any cowpuncher—I don't believe in working only in spots; but sometimes I'd get so tired of doing nothing at the house that I'd get the chauffore to take me down to Old Man Wright's office, where I felt more at home. Nobody never come in to see us once—not in three months. We didn't have no neighbors, and we begun to see that that was the truth. I couldn't understand it, for we'd never got caught at nothing.

"Colonel," says I one morning, "do you reckon they're holding our past up against us anyways?" says I. "We spend a awful lot of money, but what do we get for it? Not a soul has came in our new house. As for me, I know I ain't earning no salary."

"Don't worry about that, Curly," says he. "You're getting plenty of grub and a place to sleep, ain't you? I'm the one that ought to worry, because I can't hardly find nothing to do here except make a little money."

"Won't there nobody play cards or nothing? Ain't there no sports in this town?" says I.

"Poker here is a mere name." He shakes his head. "If you push in a hundred before the draw you're guilty of manslaughter. But there is other ways of making money."

"How is the deferred payments on the Circle Arrow coming on?" says I.

"One come in, so far, interest and all," says he. "I wisht it hadn't. First thing I know, I'll be as rich as Old Man Wisner here. I see he wants to run for alderman up in that ward. Now I wonder what his game is there—it don't stand to reason he'd want to be a alderman now, unless there's something under it. You'd think he was trying to run the town and the whole world, too, wouldn't you?"

"I don't like that outfit," says I. "They ain't friendly. If a man don't neighbor with you, like enough he's stealing somewhere and don't want to be watched."

"That certainly is so," says he. "Still, I been busy enough for a while."

"The first thing you know," I says to him, "you'll lose your roll, and then where will we be?" But he only laughs at that.

"For instance," says he, "you see all them electric lights all over this town. I begun to study about them things when I first come here. There's a sort of little thing inside that they burn—carbon, they call it. I seen that everybody would keep their eyes on the light and not notice the carbon. But still they had to have carbon. I put a little into a company that made them things—not much; only a hundred thousand or so. Since then, what have they done? Why, they've turned in and gave me eighty per cent stock for nothing, and raised the cash dividend until I'm making twenty per cent on all I invested and what I didn't invest too. Such things bores me.

"Then again, there's my rubber business," says he, "rubber tires. The second day we owned the big car she busts a couple of tires—fifty dollars or so per each. I begun to figure out how many cars they was running in this town, up and down the avenue and all over all the other streets, each one of 'em with four tires on and any one of 'em liable to bust any minute. I figure the tires runs from fifteen to sixty dollars apiece and that somebody spends a lot of money for them. Then I went and bought into a good company that makes them things, a few months ago—not much; only a couple of hundred thousand or so. But what's the use?" He sets back and yawns, looking tired.

"I can't help it. I can't find no game in this country that's hard enough to play for to be interesting. What them rubber-tire people done was to make me a present of a whole lot of other stock the other day and raise the dividends. I can't buy into no company at all, it seems like, 'less'n every twenty minutes or so they up and declare another dividend. I don't like it. I wisht I could find some real man's-size game to play, because I'm like you—I get lonesome."

Still, he was looking thoughtful.

"Some games we can play," says he. "Then again, seems like there's others we can't. Now about the kid——"

"She's busy all the time," says I to him. "She reads and paints. Sundays she goes to church, while you and me only put on a collar that hurts. Week days she goes down to the picture galleries and into the liberry. She buys books. She's got her own cars—the big car and the electric brougham you give her on her birthday last week—ain't a thing in the world she ain't got. She's plumb happy."

"Except that she ain't!"

"You mean that we don't know nobody—nobody comes in to visit?" He nods. "Well, why don't we go in and call on them Wisner people that lives next to us?" says I.

"We can't do that; the rules of the game is that the folks living in a place first has to make the first call."

"That's a fool rule," says I.

"Shore it is; but Bonnie Bell knows all them rules and she ain't going to make any break—Old Man Smith taught her a few things—or maybe she learned it instinctive from her ma. Her ma was a Maryland Janney. They pretty near knew. And yet she told me—— Oh, shucks, Curly!"

"Well, what did she say?"

"She says she met Old Lady Wisner fair out on the sidewalk one morning and she was going to speak to her; they was both of them going down to their cars, which was standing side by side on the street. The old lady, she turns up her nose, such as there was of it, and she looks the other way. That hurt my girl a good deal. You know she ain't got a unkind thought in her heart for nobody or nothing on earth. She never was broke to be afraid of nothing or expect nothing but good of nobody—you and me taught her that, didn't we, Curly? And that old cat wouldn't look at my girl! Well, Curly, that's what I mean when I say there is some games that seems hard to play. Don't a woman get the worst of it every way of the deck, anyhow?"

"Well now," says I, "ain't there no way we can break in there comfortable like?"

"I don't see how," says he, shaking his head.

"Why can't we kill their dog?" says I. "Something friendly, just to start things going."

"That ain't no good," says he. "We tried it. Bonnie Bell already killed two of their dogs with her new electric brougham. You see, she had to go out and try it for herself, for she says she can ride anything that has hair on it, even if it's only curled hair in the cushions. First thing you know, the Wisner dog—pug nose it was, with its tail curled tight—it goes out on the road, acting like it owned the whole street, same as its folks does. Well, right then him and Bonnie Bell's new electric mixes it. The dog got the worst of it.

"Look-a-here, Curly," says he after a while, and pulls a square piece of paper outen his pocket. "Here's what we got in return for that—before Bonnie Bell had time to say she was sorry. The old lady wrote, for once: