The Project Gutenberg EBook of Won from the Waves, by W.H.G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Won from the Waves

Author: W.H.G. Kingston

Illustrator: J.B. Greene

Release Date: November 24, 2007 [EBook #23602]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WON FROM THE WAVES ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

W.H.G. Kingston

"Won from the Waves"

Chapter One.

On the Pier.

It was a gloomy evening. A small group of fishermen were standing—at the end of a rough wooden pier projecting out into the water and forming the southern side of the mouth of a small river. A thick mist, which drove in across the German Ocean, obscured the sky, and prevented any object being seen beyond a few hundred fathoms from the shore, on which the dark leaden-coloured waves broke lazily in with that sullen-sounding roar which often betokens the approach of a heavy gale.

On the north side of the river was a wide extent of sandy ground, where the vegetation consisted of stunted furze-bushes and salt-loving plants with leaves of a dull pale green, growing among patches of coarse grass, the roots of which assisted to keep the sand from being blown away by the fierce wintry gales which blew across it. On the right hand of the fishermen as they looked seaward, and beyond an intervening level space, rose a line of high cliffs of light clay and sand extending far to the southward, with a narrow beach at their base. Parallel with the river was a green bank, on the sides of which were perched several cottages, the materials composing them showing that they were the abodes of the hardy men who gained their livelihood on the salt deep. The palings which surrounded them, the sheds and outhouses, and even the ornaments with which they were decorated, were evidently portions of wrecks. Over the door of one might be seen the figure-head of some unfortunate vessel. An arbour, not rustic but nautical, was composed of the carved work of a Dutch galliot; indeed, the owners of few had failed to secure some portion of the numerous hapless vessels which from time to time had been driven on their treacherous coast.

On the level ground between the cliff and the river stood two or three other cottages. One, the largest of them, appeared to be built almost entirely of wreck wood, from the uneven appearance presented by the walls and roof, the architect having apparently adapted such pieces of timber as came to hand without employing the saw to bring them into more fitting shape; the chimney, however, and the lower portions of the walls, were constructed of hewn stone, taken probably from some ancient edifice long demolished. Though the exterior of the cottage, with its boat and fish sheds, looked somewhat rough, it had altogether a substantial and not uncomfortable appearance.

The most conspicuous object in the landscape was a windmill standing a little way to the southward on the top of the cliff. Its sails were moving slowly round, but their tattered condition showed that but a small amount of grist was ground within.

Such was the aspect of the little village of Hurlston and its surroundings towards the end of the last century. It was not especially attractive—indeed few scenes would have appeared to advantage at that moment; but when sunshine lighted up the blue dancing waters, varied by the shadows of passing clouds, the marine painter might have found many subjects for his pencil among the picturesque cottages, their sturdy inhabitants, the wild cliffs, and the yellow strand glittering with shells.

Farther inland the country improved. On the higher ground to the south were neat cottages rising among shrubberies, the parish church with its square tower, and yet farther off the mansion of Sir Reginald Castleton, in the midst of its park, with its broad lake, its green meadows and clumps of wide-spreading trees, surrounded by a high paling forbidding the ingress of strangers, and serving to secure the herd of graceful deer which bounded amidst its glades.

The fishermen—regardless of the driving mist, which, settling on their flushing coats and sou’-westers, ran off them in streamlets—kept turning their eyes seawards, endeavouring to penetrate the increasing gloom.

“Here comes Adam Halliburt!” exclaimed one of them, turning round; “we shall hear what he thinks of the weather. If he has made up his mind to go to sea to-night, it must come on much worse than it now is to keep him at home.”

As these words were uttered, a tall man a little past middle age, strongly-built and hardy-looking as the youngest, habited like the rest in fisherman’s costume, was seen approaching from the largest of the cottages on the level ground. His face, though weather-beaten, glowed with health, his forehead was broad, his bright blue eyes beaming with good-nature and kindly feeling. He was followed by a stout fisher-boy carrying a coil of rope over his shoulders, and a basket of provisions in his hand. Two other lads, who had been with the men on the pier, ran to meet him.

“They are doubtful about going to sea to-night. What do you think of it, father?” said the eldest.

“There is nothing to stop us that I see, Ben, unless it comes on to blow harder than it does now,” answered Adam, in a cheery voice. “The Nancy knows her way to our fishing-grounds as well as we do, and it must be a bad night indeed to stop her.”

“What do you think of it, Adam?” asked two or three of the men, when he got among them.

Halliburt turned his face seaward, sheltering his eyes with his hand from the thick drizzle which the mist had now become.

“If the wind holds from the south-east there will be nothing to stop us,” he answered, after waiting a minute. “It is likely, however, to be a dirtier night than I had thought for—I will own that. Jacob,” he said to his youngest boy, “do you go back and stay with your mother, she wants some help in the house, and you can look after the pigs and poultry before we are back in the morning.”

Jacob, a fine lad of ten or twelve years, though he looked older, seemed somewhat disappointed, as he had expected to have gone to sea with his father and brothers. Without attempting, however, to expostulate, he immediately turned back towards the cottage, while the rest of the party proceeded to the Nancy, a fine yawl which lay at anchor close to the pier.

She was quickly hauled alongside, when some of the men jumped into her. Before following them, Adam Halliburt took another glance seaward. The wind drove the rain and spray with greater force than before against his face.

“We will wait a bit, lads,” he said. “There is no great hurry, and in a few minutes we shall make out what the weather is going to be.”

His own sons and some of the men remained in the boat, knowing that he was not likely to give up his intention unless the weather speedily became much worse. Others followed him back to the pier-head, over which the spray beat in frequent showers, showing that the sea had got up considerably, even since they had left it.

They had retreated back a few paces to avoid the salt showers. Adam still seemed somewhat unwilling to give up putting to sea, when the dull sound of a gun from the offing reached their ears. Another and another followed.

“There is a ship on Norton Sands,” observed one of the men. “Those guns are too far off for that,” answered Halliburt. Two others followed, and then came the thunder-sounding reports of several fired together.

“I was sure those were not guns of distress. They come from ships in action, depend on that; and the news is true we heard yesterday, that the French and English are at it again,” exclaimed Adam. “I thought we shouldn’t long remain friends with the Mounsiers.”

“Good luck be with the English ships!” cried one of the fishermen.

“Amen to that! but they must be careful what they are about, for with the wind dead on shore, if they knock away each other’s spars, they are both more than likely to drift on Norton Sands, and if they do, the Lord have mercy on them,” said Adam, solemnly. “Whichever gets the victory, they will be in a bad way, as I fear, after all, it will be a dirty night. The wind has shifted three points to the eastward since I left home, and it’s blowing twice as hard as it did ten minutes ago. We may as well run the Nancy up to her moorings, lads.”

As one of the men was hurrying off to carry this order to the rest, a heavier blast than before came across the ocean. It had the effect of rending the veil of mist in two, and the rain ceasing, the keen eyes of the fishermen distinguished in the offing two ships running towards the land, the one a short distance ahead of the other, which was firing at her from her bow-chasers, the leading and smaller vessel returning the fire with her after guns, and apparently determined either to gain a sheltering harbour or to run on shore rather than be taken. The moment that revealed her to the spectators showed those on board how near she was to the shore, though evidently they were not aware of the still nearer danger of the treacherous sandbank. An exclamation of dismay and pity escaped those who were looking at her.

“If she had been half a mile to the nor’ard she might have stood through Norton Gut and been safe,” observed Halliburt; “but if she is a stranger there is little chance of her hauling off in time to escape the sands.”

While he was speaking, the sternmost ship was seen to come to the wind; her yards were braced up, and now, apparently aware of her danger, she endeavoured to stand off the land before the rising gale should render the undertaking impossible. The hard-pressed chase directly afterwards attempted to follow her example. She was already on a wind when again the mist closed over the ocean, and she was hidden from sight.

“We will keep the Nancy where she is,” said Halliburt; “we don’t know what may happen. If yonder ship drives on the sands—and she has but a poor chance of keeping off them, I fear—we cannot let her people perish without trying to save them; and though it may be a hard job to get alongside the wreck, yet some of the poor fellows may be drifted away from her on rafts or spars, and we may be able to pick them up. Whatever happens, we must do our best.”

“Ay, ay, Adam,” answered several of his hardy crew, who stood around him; “where you think fit to go we are ready to go too.”

The party had not long to wait before their worst apprehensions were realised. The dull report of a gun, which their practised ears told them came from Norton Sands, was heard; in another minute the sound of a second gun boomed over the waters; a third followed even before the same interval had elapsed. That the ship had struck and was in dire distress there could be no doubt, but when they gazed at the dark, heaving waves which rolled in crested with foam, and just discernible in the fast waning twilight, and felt the fierce blast against which even they could scarcely stand upright on the slippery pier, hardy and bold as they were, they hesitated about venturing forth to the rescue of the hapless crew. Long before they could reach the wreck darkness would be resting on the troubled ocean; they doubted, indeed, whether they could force their boat out in the teeth of the fierce gale.

Adam took a turn on the pier. His heart was greatly troubled. He had never failed, if a boat could live, to be among the first to dash out to the rescue of his fellow-creatures when a ship had been cast on those treacherous sandbanks. The hazard was great. He knew that with the strength of his crew exhausted the boat might be hurled back amid the breakers, to be dashed on the shore; or, should they even succeed in reaching the neighbourhood of the wreck, where the greatest danger was to be encountered, they might fail in getting near enough to save any of the people.

Every moment of delay increased the risk which must be run.

“Lads, we will try and do it,” he said at length; “maybe she has struck on the lowest part of the bank, and we shall be able to cross it at the top of high water. Come along, we will talk no more about it, but try and do what we have got to do.”

Just at that instant the words, uttered in a shrill, loud tone, were heard:—

“Foolish men, have you a mind to drown yourselves in the deep salt sea! Stay, I charge you, or take the consequence.”

The voice seemed to come out of the darkness, for no one was seen. The men looked round over their shoulders. Directly afterwards a tall thin figure, habited in grey from head to foot, emerged from the gloom. Those who beheld it might have been excused if they supposed it rather a phantom than a being of the earth, so shadowy did it appear in the thick mist.

“The spirit of the air forbids your going, and I, his messenger, warn you that you seek destruction if you disobey him.”

The men gathered closer to each other as the figure approached. It was now seen to be that of a tall, gaunt woman. Her loose cloak and the long grey hair which hung over her shoulders blew out in the wind, giving her face a wild and weird look, for she wore no covering to restrain her locks, with the exception of a mass of dry dark seaweed, formed in the shape of a crown, twisted round the top of her head.

“I have seen the ship you are about to visit. I knew what her fate would be even yesternight when she was floating proudly on the ocean; she was doomed to destruction, and so will be all those who venture on board her. If you go out to her, I tell you that none of you will return. I warn you, Adam Halliburt, and I warn you all! Go not out to her, she is doomed! she is doomed! she is doomed!”

As the woman uttered these words she disappeared in the darkness. The men stood irresolute.

“What, lads, are you to be frightened at what ‘Sal of the Salt Sea’ says, or ‘Silly Sally,’ as some of you call her?” exclaimed Adam. “Let us put our trust in God, He will take care of us, if it’s His good pleasure. It’s our duty to try and help our fellow-creatures. Do you think an old mad woman knows more than He who rules the waves, or that anything she can say in her folly will prevent Him from watching over us and bringing us back in safety?”

Adam’s appeal had its due effect. Even the most superstitious were ashamed of refusing to accompany him. When he sprang on board the boat his crew willingly followed. He would have sent back his second boy Sam, but the lad earnestly entreated to be taken.

“If you go, father, why should I stop behind? Jacob will look after mother, and I would rather share whatever may happen to you,” he said.

Adam and his men were soon on board the boat: the most of them had shares in her, and thus they risked their property as well as their lives. The oars were got out, and the men, fixing themselves firmly in their seats, prepared for the task before them.

Shoving off from the shore, Adam took the helm. The men pulled away right lustily, and emerging from the harbour, in another minute they were breasting the heaving foam-crested billows in the teeth of the gale. Sometimes, when a stronger blast than usual swept over the water, they appeared, instead of making headway, to be drifting back towards the dimly-seen shore astern. Now, again exerting all their strength, they once more made progress in the direction of the wreck.

All this time the minute guns had been heard, showing that the ship still held together, and that help, if it came, would not be useless. The sound encouraged Adam and his crew to persevere. The reports, however, now came at longer intervals than at first from each other. Several minutes at length elapsed, and no report was heard. Adam listened—not another came. The crew of the Nancy, however, persevered, but even Adam, as he observed the slow progress they had made, became convinced that their efforts would prove of no avail.

The gale continued to increase, the foaming seas leaped and roared around them more wildly than before. Even to return would now be an operation of danger, but Adam with sorrow saw that it must be attempted. For an hour or more no headway had been made. He waited for a lull, then giving the word, the boat was rapidly pulled round, and surrounded by hissing masses of foam, she rapidly shot back within the shelter of the harbour. The sinews of her crew were too well strung to feel much fatigue under ordinary circumstances, but the strongest had to acknowledge that they could not have pulled much longer.

“We must not give it up, though, lads,” said Adam. “I am sure no beachmen will be able to launch their boats to-night along the coast. If the wind goes down ever so little, we must try it again; you will not think of deserting the poor people if there is a chance of saving them, I know that.”

His crew responded to his appeal, and agreed to wait for the chance of being able to get off later in the night.

Looking towards the landing-place, the tall figure of Sal of the Salt Sea was seen standing on the edge of the pier gazing down upon them.

“Foolish men! you have had your toil for nought, yet it is well for you that you could not reach the doomed ship. I warned you, and you disregarded me. I commanded the winds and waves to stop your progress; they listened to my orders and obeyed me. You will not another time venture to disregard my warnings. Now go to your homes, and be thankful that I did not think fit to punish you for your folly. Again I warn you that yonder ship is doomed! is doomed! is doomed!”

While the old woman was uttering these words in the same harsh, loud tones as before, Adam and his crew were making their way to the landing-place. Before they reached it, however, the strange being had disappeared in the darkness, though her voice could be heard as she took her way apparently towards the cliffs.

“Again, lads, I say, don’t let what you have heard from the poor mad woman trouble you,” exclaimed Adam. “Come to my cottage, and we will have a bite of supper, and wait till we have the chance of getting off again.”

Dame Halliburt, expecting them, had prepared supper. The sanded floors and rough chairs and stools which formed the furniture of her abode were not to be injured by their dripping garments. During the meal Adam, or one of the men, went out more than once to judge if there was likely to be a change. Still the gale blew as fiercely as ever. Some threw themselves down on the floor to rest, while Adam, filling his pipe, sat in his arm-chair by the fire, still resolved as at first to persevere.

Chapter Two.

At the Wreck.

Thus the greater part of the night passed by. Towards dawn Adam started up. The howling of the wind in the chimney and the rattling sound of the windows which looked towards the sea decreased.

“Lads!” he shouted, “the gale is breaking, we may yet be in time to save life, and maybe to get salvage too from the wreck. We will be off at once.”

The crew required no second summons. Telling his dame to keep up her spirits, and that he should soon be back, he led the way to the pier.

Some of the men, hardy fellows as they were, looked round nervously, expecting the appearance of Sal of the Salt Sea. She did not return, however, and they were soon on board. The poor creature, probably not supposing that they would again venture out, had not thought of being on the watch for them.

Once more the Nancy, propelled by the strong arms of her hardy crew, was making her way towards Norton Sands. It was still dark as before, but the wind had gone down considerably, and the task, though such as none but beachmen would have attempted, seemed less hopeless. After rowing for some time amidst the foaming seas, Adam stood firmly up and endeavoured to make out the ship. At length he discovered a dark object rising above the white seething waters: it was the wreck. Two of her masts were still standing. She was so placed near the tail of the bank, where the water was deepest, that he hoped to be able to approach to leeward, and thus more easily to board her if necessary.

“We shall be able to save the people if we can get up to her soon, lads,” he exclaimed. “Cheer up, my brave boys, it will be a proud thing if we can carry them all off in safety.”

The wind continued to decrease. As they neared the bank, the force of the sea, broken by it, offered less opposition.

Just then amidst the gloom he caught sight of another object at a little distance from the wreck: it was a lugger under close-reefed sails standing away on a wind towards the south. “Can she have been visiting the wreck?” thought Adam; “it looks like it. If so, she must have taken off the people. Then why does she not run for Hurlston, where she could most quickly land them?”

As these thoughts passed through his mind, the lugger, which a keen eye like his alone could have discerned, disappeared in the darkness.

“I wonder if that can be Miles Gaffin’s craft,” he thought; “no one, unless well acquainted with the coast, would venture in among these sandbanks in this thick weather; she is more likely to be knocking about here than any other vessel that I know of. She has been after her usual tricks, I doubt not.”

Adam, however, did not utter his thoughts aloud. Indeed, unless he had spoken at the top of his voice he could not have been heard even by the man nearest him, while all his attention was required in steering the boat.

The crew had still some distance to pull, and their progress against the heavy seas was but slow. At length dawn began to break, and the wreck rose clearly before them. She was a large ship. The foremast had gone by the board, but the main and mizzen-masts, though the topmasts had been carried away, were still standing.

With cool daring they pulled under her stern. To their surprise, no one hailed them—not a living soul did they see on the deck.

As a sea which swept round her lifted the boat, Adam, followed by his son Ben and another man, sprang on board. A sad spectacle met their sight. The sea had made a clean sweep over the fore part of the ship, carrying away the topgallant, forecastle, and bulwarks, and, indeed, everything which had offered it resistance, but the foremast still hung by the rigging, in which were entangled the bodies of three or four men who had either been crushed as it fell or drowned by the waves washing over them. The long-boat on the booms had also been washed away—indeed, not a boat remained. The guns, too, of which, though evidently a merchantman, she had apparently carried several, had broken adrift and been carried overboard, with the exception of the aftermost one, which lay overturned, and now held fast a human being, and, as her dress proved her to be a woman. The complexion of the poor creature was dark, and the costume she wore showed Adam that she was from the far-off East. Ben lifted her hand; it fell on the deck as he let it go; it was evident that no help could be of use to her. Her distorted countenance exhibited the agonies she must have suffered.

“She must have been holding on to the gun,” observed Adam, “when it capsized; and if I read the tale aright, she was standing there calling to those in the boats to come back for her as they were shoving off. If the boats had not been lowered, we should have seen some of the wreck of them hanging to the davits. See, the falls are gone on both sides.”

Having made a rapid survey of the deck, Adam looked seaward.

“We have no time to lose,” he said, “for the sky looks dirty to windward, and we shall have the gale down on us again before long, I suspect. We must first, though, make a search below, for maybe some of the people have taken shelter there. I fear, however, the greater number must have been washed away, or attempted to get off in the boats.”

Adam, leading the party, hurried below.

The water was already up to the cabin deck, and the violent rocking of the ship told them that it would be dangerous to spend much time in the search. No one was to be found.

“Let us have the skylight off, Tom, to see our way,” said Ben.

Tom sprang on deck and soon forced it off, and the pale morning light streamed down below. Everything in the main cabin was in confusion.

“This shows that the people must have got away in the boats, and have carried off whatever they could lay hands on, unless some one else has visited the wreck since then,” remarked Adam; and he then told Ben of his having observed the lugger in the neighbourhood of the wreck.

“She looks to me like a foreign-built ship, although her fittings below are in the English fashion,” he observed, examining the cabins as far as the dim twilight which made its way through the open hatch would allow.

“As we came under her stern I saw no name on it; I cannot make out what she can be.”

The lockers in the captain’s state cabin were open, and none of his instruments were to be seen. Two or three of the other side cabins had apparently been searched in a hurry for valuables. The doors of the aftermost ones were however still closed. The violent heaving and the crashing sounds which reached their ears, showing how much the ship was suffering from the rude blows of the seas, made Adam unwilling to prolong the search. He and his companions secured such articles as appeared most worth saving.

“Let us look into the cabin before we go,” exclaimed Ben, opening the door of one which seemed the largest. As he did so a cry was heard, and a child’s voice asked, “Who’s there?” He and Adam sprang in.

Chapter Three.

Safe to Land.

As Adam Halliburt and his son sprang into the cabin, they saw in a small cot by the side of a larger one, a little girl, her light hair falling over her fair young neck. She lifted her head and gazed at them from her blue eyes with looks of astonishment mingled with terror.

“Is no one with you, my pretty maiden?” exclaimed Adam; “how came you to be left all alone here?”

“Ayah gone. I called, she no come back,” answered the child.

“This is no place for you, my little dear, we will take care of you,” said Adam, lifting her up and wrapping the bed clothes round her, for she was dressed only in her nightgown.

“Oh, let me go; I must stay here till my ayah comes back,” cried the child; yet she did not struggle, comprehending, it seemed, from the kind expression of Adam’s countenance, that he intended her no harm.

“The person you speak of won’t come back, I fear; so you must come with us, little maid, and if God wills we will carry you safely on shore,” answered Adam, folding the clothes tighter round the child, and grasping her securely in his left arm as a woman carries an infant, and leaving his right one at liberty, for this he knew he should require to hold on by, until having made his way across the heaving, slippery deck, he could take the necessary leap into the boat.

“It is wet and cold, we must cover you up,” he said, adding to himself, “The child would otherwise see a sight enough to frighten her young heart.”

The little girl did not again speak as Adam carried her through the cabins.

“You must let go those things, lads, and stand ready for lending me a hand to prevent any harm happening to this little dear,” he said, as he mounted the companion-ladder.

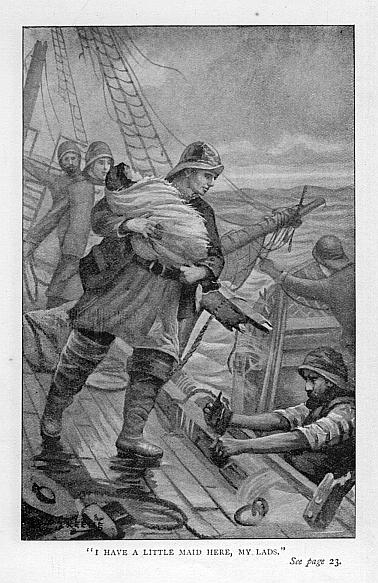

Before reaching the deck he drew the blanket over the child’s face, and then, with an activity no younger seaman could have surpassed, he sprang to the side of the ship and grasped a stanchion, to which he held on while he shouted to the crew of his boat, who had for safety’s sake pulled her off a few fathoms from the wreck, keeping their oars going to retain their position.

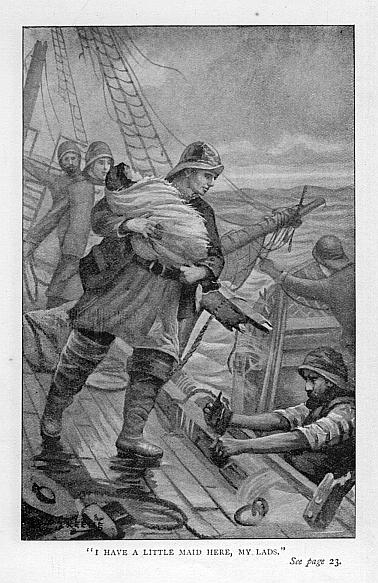

“Pull up now, lads! We have got all there is time for,” he cried out. “Ben and Tom, do you leap when I do. I have a little maid here, my lads, and we must take care no harm comes to her.”

While he was speaking the boat was approaching. Now she sank down, almost touching the treacherous sands beneath her keel—now, as the sea rolled in, part of which broke over the wreck, she rose almost to a level with the deck. Adam, who had been calculating every movement she was about to make, sprang on board. Steadying himself by the shoulders of the men, he stepped aft with his charge. Ben and Tom followed him.

The men in the bows, immediately throwing out their starboard oars, pulled the boat’s head round, and the next instant, the mast being stepped and the sail hoisted, the Nancy was flying away before the following seas towards the shore. Adam steered with one hand while he still supported the child on his arm.

“You are all right now, my little maid,” he said, looking down on her sweet face, the expression of which showed the alarm and bewilderment she felt, he having thrown off the blanket.

“We will soon have you safe on shore in the care of my good dame. She will be a mother to you, and you will soon forget all about the wreck and the things which have frightened you.”

As Adam turned a glance astern, he was thankful that he had not delayed longer on board the wreck. The wind blew far more fiercely than before, and the big seas came hissing and foaming in, each with increased speed and force.

The Nancy flew on before them. The windmill, the best landmark in the neighbourhood, could now be discerned through the mist and driving spray. Adam kept well to the nor’ard of it. The small house near the pier-head, which served to shelter pilots and beachmen who assembled there, next came into view, and the Nancy continuing her course, guided by the experienced hand of her master, now mounting to the top of a high sea, now descending, glided into the mouth of the harbour, up which she speedily ran to her moorings.

Adam, anxious to get his little maid, as he called her, out of the cold and damp, and to place her in charge of his wife, sprang on shore. Jacob, who had been on the look-out for the return of the Nancy since dawn, met him on the landing-place.

“Are all safe, father?” he asked, in an anxious tone.

“All safe, boy, praised be His name who took care of us, and no thanks to that poor creature, Mad Sal, who would have frightened the lads and me from going off, and allowed this little maid here to perish.”

“What! have you brought her from the wreck?” inquired Jacob, eagerly, looking into the face of the child, who at that moment opened her large blue eyes and smiled, as she caught sight of the boy’s good-natured countenance.

“Is she the only one you have brought on shore, father?” he added.

“The only living creature we found on board, more shame to those who deserted her, though it was God’s ordering that she might be preserved,” answered Adam. “But run on, Jacob, and see that the fire is blazing up brightly, we shall want it to dry her damp clothes and warm her cold feet, the little dear.”

“The fire is burning well, father, I doubt not, for I put a couple of logs on before I came out; but I will run on and tell mother to be ready for you,” answered Jacob, hastening away.

Adam followed with rapid strides.

The dame stood at the open door to welcome him as he entered.

“What, is it as Jacob says, a little maid you have got there?” she exclaimed, opening her arms to receive the child from her husband.

The dame was an elderly, motherly-looking woman, with a kindly smile and pleasant expression of countenance, which left little doubt that the child would be well cared for.

“Bless her sweet face, she is a little dear, and so she is!” exclaimed the dame, as she pressed her to her bosom. “Bless you, my sweet one, don’t be frightened now you are among friends who love you!” she added, as she carried her towards the fire which blazed brightly on the hearth, and observed that the child was startled on finding herself transferred to the arms of another stranger.

“Bring the new blanket I bought at Christmas for your bed, Jacob, and I will take off her wet clothes and wrap her in it, and warm her pretty little feet. Don’t cry, deary, don’t cry!” for the child, not knowing what was going to happen, had now for the first time begun to sob and wail piteously.

“Maybe she is hungry, for she could have had nothing to eat since last night, little dear,” observed Adam, who was standing by, his damp clothes steaming before the blazing fire.

“We will soon have something for her, then,” answered the dame.

Jacob brought the blanket, which the dame gave Adam to warm before she wrapped it round the child.

“Run off to Mrs Carey’s as fast as your legs can carry you, and bring threepenny-worth of milk,” she said to her son. “Tell her why I want it; she must send her boy to bring in the cow; don’t stop a moment longer than you can help.”

Jacob, taking down a jug from the dresser, ran off, while the dame proceeded to disrobe the little stranger, kissing and trying to soothe her as she did so. Round her neck she discovered a gold chain and locket.

“I was sure from her looks that she was not a poor person’s child, this also shows it,” she observed to her husband; “and see what fine lace this is round her nightgown. It was a blessed thing, Adam, that you saved her life, the little cherub; though, for that matter, she looks as fit to be up in heaven as any bright angel there. But what can have become of those to whom she belongs? Of one thing I am very sure, neither father nor mother could have been aboard, for they would not have left her.”

“I’ll tell thee more about that anon,” observed Adam, recollecting the poor coloured woman whose wretched fate he had discovered; “I think thou art right, mother.”

The child had ceased sobbing while the dame was speaking, and now lay quietly in her arms enjoying the warmth of the fire.

“She will soon be asleep and forget her cares,” observed the dame, watching the child’s eyelids, which were gradually closing. “Now, Adam, go and get off thy wet clothes, and then cut me out a piece of crumb from one of the loaves I baked yestere’en, and bring the saucepan all ready for Jacob when he comes with the milk.”

“I’ll get the bread and saucepan before I take off my wet things,” answered Adam, smiling. “The little maid must be the first looked to just now.”

Jacob quickly returned, and the child seemed to enjoy the sweet bread-and-milk with which the dame liberally fed her.

A bed was then made up for her near the fire, and smiling her thanks for the kind treatment she received, her head was scarcely on the pillow before she was fast asleep.

Chapter Four.

May’s New Home.

“What are you going to do with her?” asked Jacob, who having stolen down from his roosting-place after a short rest, found his father and mother sitting by the fire watching over the little girl, who was still asleep.

“Do with her!” exclaimed Dame Halliburt, looking at her husband, “why, take care of her, of course, what else should we do?”

“No one owns her who can look after her better than we can; we have a right to her, at all events, and we will do our best for the little maiden,” responded Adam, returning his wife’s glance.

“I thought as how you would, father,” said Jacob, in a tone which showed how greatly relieved he felt. “I knew, mother, you would not like to part with the little maid when once you had got her, seeing we have no sister of our own; she will be a blessing to you and to all of us, I am sure of that.”

“I hope she will, Jacob; I sighed, I mind, when I found you were not a girl, for I did wish to have a little daughter to help me, though you are a good boy, and you mustn’t fancy I love you the less because you are one.”

“I know that, mother,” answered Jacob, in a cheerful tone; “but I don’t want her to work instead of me, that I don’t.”

“Of course not, Jacob,” observed Adam; “she is a little lady born, there is no doubt about it; and we must remember that, bless her sweet face. I could not bear the thoughts of such as she having to do more work than is good for her. Still, as God has sent her to us, if no one claims her we must bring her up as our own child, and do our best to make her happy, and she will be a light and joy in the house.”

“That I’m sure she will,” interrupted Jacob; “and Ben and Sam and I will all work for her, and keep her from harm, just as much as if mother had had a little maid, that we will.”

“Yes, yes, Jacob, I am sure of it,” exclaimed the dame, smiling her approval as she glanced affectionately at her son.

So the matter was settled, and the little girl was to be henceforth looked on as the daughter of the house.

“Of course, dame, I must do what I can, though, to find out whether the little maid has any friends in this country,” observed Adam, after keeping silence for some minutes, as if he had been considering over the subject; “she may or she may not, but when I come to think of the poor dark woman who was on board, and who I take to have been her nurse, she must have come from foreign parts. Still, as she speaks English, even if her fair hair and blue eyes did not show that, it is clear that she has English parents, and if they were not on board, and I am very sure they were not, she must have been coming to some person in England, who will doubtless be on the look-out for her. So you must not set your heart on keeping the little maiden, for as her friends are sure to be rich gentlefolks she would be better off with them than with us.”

“As to that Adam, I have been thinking as you have; but then you see it’s not wealth that gives happiness, and if we bring her up and she knows no other sort of life, maybe she will be as happy with us as if she were to be a fine lady,” answered the dame looking affectionately at the sleeping child.

“But right is right,” observed Adam; “we would not let her go to be worse off than she would be with us, that’s certain; but we must do our duty by her, and leave the rest in God’s hands.”

Just then the child opened her large blue eyes, and after looking about with a startled expression, asked, “Where ayah?” and then spoke some words in a strange-sounding language, which neither the fisherman nor his wife could understand.

“She you ask for, my sweet one, is not here,” said the dame, bending over her; “but I will do instead of her, and you just think you are at home now with those who love you, and you shall not want for anything.”

While the dame was speaking the two elder lads came downstairs, and as the appearance of so many strangers seemed to frighten the little girl, Adam, putting on his thick coat and sou’-wester, and taking up his spyglass, called to his sons to come out and see what had become of the ship.

They found it blowing as hard as ever. The sea came rolling towards the shore in dark foaming billows. The atmosphere was, however, clear; and the wreck could still be distinguished, though much reduced in size. While Adam had his glass turned towards it he observed the mizzen-mast, which had hitherto stood, go by the board, and the instant afterwards the whole of the remaining part of the hull seemed to melt away before the furious seas which broke against it.

“I warned you that the ship was doomed, and that no human being would reach the shore alive,” shrieked a voice in his ears; “such will be the fate, sooner or later, of all who go down on the cruel salt sea.”

Adam turning saw Mad Sally standing near him, and pointing with eager gestures towards the spot where the wreck had lately appeared.

“Ah, ah, ah!” she shouted, in wild, hoarse tones, resembling the cries of the sea-gull as it circles in the air in search of prey.

“Sad news, sad news, sad news I bring,

Sad news for our good king,

For one of his proud and gallant ships

Has gone down in the deep salt sea, salt sea,

Has gone down in the deep salt sea.”

“Yonder ship has gone to pieces, there is no doubt about that, mother,” said Adam; “but you were wrong to warn us not to go off to her, for go off we did, and brought one of her passengers on shore who would have perished if we had listened to you, so don’t fancy you are always right in what you say.”

“If you brought human being from yonder ship woe will come of it. Foolish man, you fought against the fates who willed it otherwise.”

“I know nothing about the fates, mother,” answered Adam; “but I know that God willed us to bring on shore a little girl we found on board, and protected us while we did so.”

“Think you that He would have protected you when He did not watch over my boy, who was carried away over the salt sea?” she exclaimed, making a scornful gesture at Adam. “He protects not such as you, who madly venture out when in His rage He stirs up the salt sea, salt sea, salt sea!” and she broke out into a wild song—

“There were three brothers in Scotland did dwell,

And they cast lots all three,

Which of them should go sailing

On the wide salt sea, salt sea;

Which of them should go sailing

On the wide salt sea;”

and, wildly flourishing her arms, she stalked away towards the cliffs, up which she climbed, still making the same violent gestures, although her voice could no longer be heard, till she disappeared in the distance.

A number of people had collected along the beach, eagerly looking out for any portion of the wreck or cargo which might be washed on shore, but they looked in vain; the sands swallowed up the heavier articles, while the rest were swept by the tide out to sea. Nothing reached the shore by which the name or character of the vessel which had just gone to pieces could be discovered.

Adam Halliburt, finding that there was no probability of the weather mending sufficiently to enable the Nancy to put to sea, returned home.

“Look you, lads,” he observed, calling his sons to his side; “you heard what that poor mad woman said. You see how she was all in the wrong when she told us not to put off to the wreck, and warned us that we should come to harm if we did. Now, to my mind, she is just a poor mad creature; but if she does know anything which others don’t, it’s Satan who teaches her, and he was a liar from the beginning, and therefore she is more likely to be wrong than right; and when you hear her ravings, don’t you care for them, but go on and do your duty, and God will take care of you; leave that to Him.”

“Ay, ay, father,” answered Jacob; “she would have had us leave the little maiden to perish, if we had listened to her; I will never forget that.”

While the elder lads went on board the Nancy to do one of the numberless jobs which a sailor always finds to be done on board his craft, Jacob and his father entered the cottage.

The little girl was seated on the dame’s knee, prattling in broken language, which her kind nurse in vain endeavoured to understand. She welcomed the fisherman and his son with a smile of recognition.

“Glad to see you well and happy, my pretty maiden,” said Adam, stooping down to kiss her fair brow, his big heart yearning towards her as if she were truly his child.

“Maidy May,” she said, with an emphasis on the last word, as if wishing to tell him her proper name.

“Yes, our ‘Maiden May’ you are,” he answered, misunderstanding her, and from that day forward Adam called her Maiden May, the rest of the family imitating him, and she without question adopting the name.

Chapter Five.

Dame Halliburt.

Dame Halliburt was a good housewife, and an active woman of business. Every morning she was up betimes with breakfast ready for her husband and sons waiting the return of the Nancy, and as soon as her fish-baskets were loaded, away she went, making a long circuit through the neighbouring country to dispose of their contents at the houses of the gentry and farmers, among whom she had numerous customers. She generally called at Texford, though, as Sir Reginald Castleton lived much alone, she was not always sure of selling her fish there, and had often to go a considerable distance out of her way for nothing. If Mr Groocock, the steward, happened to meet her on the road he seldom failed to stop his cob, or when she called at the house to come out and inquire what was going on at Hurlston, or to gain any bits of information she might have picked up on her rounds.

Maiden May had been for upwards of a year under her motherly care, when one morning as she was approaching Texford with her heavily-loaded basket, she caught sight of the ruddy countenance of Mr Groocock, with his yellow top-boots, ample green coat, and three-cornered hat on the top of his well-powdered wig, jogging along the road towards her.

“Good-morrow, dame,” he exclaimed, pulling up as he reached her. “I see that you have a fine supply of fish, and you will find custom, I doubt not, at the Hall this morning. There are three or four tables to be served, for we have more visitors than Sir Reginald has received for many a day.”

As he spoke he looked into the dame’s basket, turning the fish with the handle of his whip.

“Ah, just put aside that small turbot and a couple of soles for my table, there’s a good woman, will you? You have plenty besides for the housekeeper to choose from.”

“I will not forget your orders, Mr Groocock,” said the dame; “and who are the guests, may I ask?”

“There is Mrs Ralph Castleton and her two sons, the eldest, Mr Algernon, who is going to college soon, and Mr Harry, a midshipman, who has just come home from sea; a more merry, rollicking young gentleman I never set eyes on; indeed, if the house was not a good big one he would turn it upside-down in no time. There is also his sister, Miss Julia, with her French governess, and Sir Reginald’s cousins, the Miss Pembertons. One of them, the youngest, Miss Mary they call her, is blind, poor dear lady; but, indeed, you would not think so to see the bright smile that lights up her face when she is talking, and few people know so much of what is going on in the world, not to mention all about birds, and creeping things, and flowers. The other day she was going through the garden, when just by touching the flowers with her fingers she was able to tell their colour and their names as well as the gardener himself.

“Then there is a Captain Fancourt, a naval officer, a brother of Mrs Ralph Castleton, and Mr Ralph Castleton himself is expected, but he is taken up with politics and public business in London, and it is seldom he can tear himself away from them.”

“I suppose Mr Ralph, then, is Sir Reginald’s heir,” observed the dame.

“That remains to be seen,” answered the steward. “You know Sir Reginald has another nephew older than Mr Ralph, who has been abroad since he was a young man. Though he has not been heard of for many years, he may appear any day. The title and estates must go to him, whatever becomes of the personalty.”

“You know when I was a girl I lived in the family of Mr Herbert Castleton, their father, near Morbury, so I remember the young gentlemen as they were then, and feel an interest in them, and so I should in their children.”

“Ah! that just reminds me that you or your husband may do Master Harry a pleasure. He has not been on shore many days before he is wanting to be off again on the salt water, and who should he fall in with but Miles Gaffin, who came up here to see me about the rent of the mill. Master Harry found out somehow or other that Miles had a lugger, and nothing would content him but that he must go off and take a cruise in her. Now, between ourselves, Mrs Halliburt, I do not trust that craft or her owner. You know, perhaps, as much about them as I do; your husband knows more, but I think it would content the young gentleman if Halliburt would take him off in his yawl, and he need not go so far from the shore as to run any risk of being picked up by an enemy’s ship.”

“Bless you, Mr Groocock, of course Adam will be main proud to take out Sir Reginald’s nephew, and for his own sake will be careful not to go far enough off the land to run the risk of being caught by any of the French cruisers,” answered the dame. “When would the young gentleman like to come? He must not expect man-of-war’s ways on board the Nancy, and it would not do for Adam and the lads to lose their day’s fishing.”

“As to that, he is not likely to be particular, and the sooner he can get his cruise the better he will be pleased. It seems strange to me that any one, when once he is comfortable on shore, should wish to be tumbling about on the tossing sea. Though I have lived all my life in sight of the ocean, I never had a fancy to leave the dry land. Give me a good roof over my head, plenty to eat and drink, and a steady cob to ride, it’s all I ask; a man should be moderate in his desires, dame, and he will get them satisfied, that is my notion of philosophy.”

“Ah! and a very good notion too,” said Mistress Halliburt, who had great respect for the loquacious steward of Texford. “But you will excuse me, Mr Groocock, I ought to be up at the Hall. I will tell Adam of Master Harry’s wish, and he will be on the look-out for him.”

“Here comes the young gentleman to speak for himself,” said the steward.

At that moment a horse’s hoofs were heard clattering along the road, and a fine-looking lad in a midshipman’s uniform cantered up on a pony, holding his reins slack, and sitting with the careless air of a sailor. He had a noble broad brow, clear blue eyes, and thick, clustering, brown curls, his countenance being thoroughly bronzed by southern suns and sea air. His features were well formed and refined, without any approach to effeminacy.

“Good-morrow, Mr Groocock,” he exclaimed, in a clear voice, pulling up as he spoke. “Good-morrow, dame,” he added, turning to Mrs Halliburt.

“I was just speaking to the dame here about your wish, Mr Harry, to take a trip to sea. Her husband, Adam Halliburt, has as fine a boat as any on the coast, and he is a trustworthy man, which is more than can be said, between ourselves, of the tenant of Hurlston Mill. Adam will give you a cruise whenever you like to go, wind and weather permitting, though, as the dame observed, you must not expect much comfort on board the Nancy.”

“I care little for comfort—we have not too much of that sort of thing at sea to make me miss it,” answered Harry, laughing. “If the dame can answer for her husband, I will engage to go as soon as he likes.”

“Adam will be glad to take you, I am main sure of that, Mr Harry,” said the dame. “But as the Nancy will be ready to put off before I get back, I would ask you to wait till to-morrow afternoon, when she will go out for the night’s fishing.”

Harry, well pleased at the arrangement, having wished the dame good-bye, accompanied Mr Groocock on his morning’s ride.

Chapter Six.

Lord Howe’s Victory.

Harry got back at luncheon time to Texford, where the family were assembled in the dining-hall. Sir Reginald—a fine-looking old man, the whiteness of whose silvery locks, secured behind a well-tied pig-tail, was increased by the hair-powder which besprinkled them—sat at the foot of the table in the wheel-chair used by him to move from room to room. His once tall and strongly-built figure was slightly bent, though, unwilling to show his weakness, he endeavoured to sit as upright as possible while he did the honours of his hospitable board. Still it was evident that age and sickness were making rapid inroads on his strength.

He had deputed his niece, Mrs Castleton, to take the head of his table. She had been singularly handsome, and still retained much of the beauty of her younger days; with a soft and feminine expression of countenance which truly portrayed her gentle, and perhaps somewhat too yielding, character—yielding, at least, as far as her husband, Ralph Castleton, was concerned, to whose stern and imperious temper she had ever been accustomed to give way.

“My dear Harry, we were afraid that you must have lost your way,” she said, when the young midshipman entered the room.

“I rode over to the post-office at Morbury for letters, and had to wait while the bag was made up. I slung it over my back, and I fancy was taken for a government courier as I rode along. I have brought despatches for every one in the house, I believe; a prodigious big one for you, Uncle Fancourt, from the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, I suspect, for I saw the seal when it was put into the bag,” he said, addressing a sunburnt, fine-looking man, with the unmistakable air of a naval officer, seated by his mother’s side. “Mr Groocock, to whom I gave the bag, will send them up as soon as he has opened it. There is something in the wind, I suspect, for I heard shouting and trumpeting just as I rode out of the town. Knowing that I had got whatever news there is at my back, I came on with it rather than return to learn more about the matter.”

“Probably another enemy’s ship taken,” observed Captain Fancourt.

“Are the Admiralty going to send you to sea again, Fancourt?” asked Sir Reginald, who had overheard Harry’s remark.

“They are not likely, during these stirring times, Sir Reginald, to allow any of us to remain idle on shore if they think us worth our salt, and I hope to deserve that, at least,” answered Captain Fancourt.

“You are worth tons of that article, or the admiral’s despatches greatly overpraise you,” observed Sir Reginald, laughing at his own joke. “I remember reading with great delight the gallant way in which, after your captain was wounded, you fought the Hector on your voyage home from the West Indies, when she was attacked by two 40-gun French frigates. You had not, I fancy, half as many men, or as many guns mounted, as either one of them, while, in addition to their crews, they were full of troops, yet you beat them off when they attempted to board; and though they had pretty well knocked your ship to pieces, you compelled them to make sail away from you, leaving you to your fate. If I recollect rightly, you bore up for Halifax with more than half your crew killed and wounded.”

“You give me more credit than is my due, Sir Reginald,” observed Captain Fancourt, “I was but a young lieutenant, though I did my duty. Captain Drury fought the ship, and we should all have lost our lives had not we fallen in with the Hawk brig, which rescued us just as the old Hector sank under our feet.”

“Well, well, when our enemies find out that it is the fashion of English sailors to fight till their ship goes down, they will be chary of attacking them with much hopes of victory.”

While the baronet was speaking, Harry had taken his seat next to a pretty dark-eyed young girl, giving her a kiss on the cheek and at the same time a pat on the back, a familiarity to which his sister Julia was well accustomed from her sailor brother, who entertained the greatest admiration and affection for her.

“You should not treat the demoiselle in that mode at table, Monsieur Harry,” observed a lady who was sitting on his other side.

“I beg your pardon, Madame De La Motte, I ought, I confess, to have paid my respects to you first.”

“Ah, you are mediant, incorrigible,” said the lady, in broken English, laughing as she spoke.

“No, I am only very hungry, so you will excuse me if I swallow a few mouthfuls before we discuss that subject,” said Harry, applying himself to the plate of chicken and ham which the footman had just placed before him. “I’m afraid that you think I have forgotten my manners as well as the French you taught me before I went to sea. But I hope to prove to you that I retain a fair amount of both,” and Harry began to address the lady in French. When he mispronounced a word and she corrected him he bowed his thanks, repeating it after her.

“Ah, you are charmant, Monsieur Harry, you have not forgotten your manners any more than the language of La Belle France, which I will continue to teach you whenever you will come and take a lesson with Mademoiselle Julia. When will you come?”

“Every day that I am at home till my country requires my services,” answered Harry.

“I never learned French, but I should think it must be a very difficult language to acquire,” observed a pale middle-aged lady of slight figure who sat opposite Harry, turning her eyes towards him, but those orbs were of a dull leaden hue, the eyelids almost closed. She was totally blind.

Her features were beautifully formed, and had a peculiarly sweet and gentle expression, though the pallor of her cheeks betokened ill-health.

“I will help you to begin, Miss Mary, while you are here, and then you can go on by yourself,” said Madame De La Motte, in her usual sprightly way.

“I thank you, madame,” answered Miss Mary Pemberton, “but I am dependent on others. Jane has no fancy for languages, and her time is much occupied in household matters and others of still higher importance.”

“Yes, indeed, Mary speaks truly,” observed Miss Pemberton, a lady of a somewhat taller and not quite so slight a figure as her sister, and who, though her features had a pleasant expression, could not, even in her youth, have possessed the same amount of beauty. She always took her seat next to Mary, that she might give her that attention which her deprivation of sight required. “While we have such boundless stores of works on all important subjects in our own language, we waste our time by spending it in acquiring another.”

“Very right, my good cousin, very right,” exclaimed Sir Reginald; “stick to our good English books, for at the present day, what with their republicanism, their infidelity, and their abominable notions, we can expect nothing but what is bad from French writers.”

“Pardonnez moi, Sir Reginald,” exclaimed Madame De La Motte, breaking off the conversation in which she was engaged with Harry, and looking up briskly. “Surely la pauvre France has produced some pure and religious writers, and many works on science worthy of perusal.”

“I beg ten thousand pardons, madame, I forgot that a French lady was present. I was thinking more of the murderous red republicans who have cut off the heads of their lawful sovereign and his lovely queen, Marie Antoinette. I remember her in her youth and beauty at the court of her brother, the Emperor Leopold, when I paid a visit to Germany some years ago. When I think how she was treated by those ruffians with every possible indignity, and perished on a scaffold, my heart swells with indignation, and I am apt to forget that there are noble and honest Frenchmen still remaining who feel as I do.”

“Ah, truly Sir Reginald, we loyal French feel even more bitterly, for we have shame added to our grief and indignation, that they are our compatriots who are guilty of such unspeakable atrocities as are now deluging our belle France with blood,” said Madame De La Motte, putting her handkerchief to her face to hide the tears which the mention of the fate of the hapless queen seldom failed to draw from the eyes of French loyalists in those days.

“You will pardon me, madame, for my inadvertent remark,” said Sir Reginald, bowing as he spoke towards the French lady.

“Certainly, Sir Reginald, and I am grateful for your sympathy in the sufferings of those I adore.”

Just at that instant the butler entered the room bearing a salver covered with letters, which most of the party were soon engaged in reading. An exclamation from Captain Fancourt made every one look up.

“There is indeed news,” he exclaimed. “Sir Roger Curtis has arrived with despatches from Earl Howe announcing a magnificent victory gained by him with twenty-five ships over the French fleet of twenty-six, on the 1st June, west of Ushant; seven of the French captured, two sunk, when the French admiral, after an hour’s close action, crowded sail, followed by most of his ships able to carry their canvas, and made his escape, leaving the rest either crippled or totally dismasted behind him. Most of our ships were either so widely separated or so much disabled, that several of the enemy left behind succeeded in making their escape under spritsails. One went down in action, when all on board perished; another sank just as she was taken possession of, and before her crew could be removed, though many happily were saved. There had been several partial actions between them.”

Exclamations of delight and satisfaction burst from the lips of all the party on hearing this announcement.

“I only wish that I had been there,” exclaimed Harry, and Captain Fancourt looked as if he wished the same.

“You might have been among those who lost their lives,” observed Miss Pemberton; “we would rather have you safe on shore.”

“We must take our chance with others,” said Harry. “I only hope, Uncle Fancourt, that you will soon be able to get me afloat again, though I am not tired of home yet.”

“I shall be able to fulfil your wishes, for the Admiralty have appointed me to the command of the Triton, 38-gun frigate, ordered to be fitted out with all despatch at Portsmouth. Before many weeks are over she will, I hope, be ready for sea. I shall have to take my leave of you, Sir Reginald, sooner than I expected. I must go down at once to look after her. Harry need not join till I send for him.”

“I congratulate you, Fancourt,” said Sir Reginald, “though I am sorry that your visit should be cut short.” The great battle was the subject of conversation for the remainder of the day, every one eagerly looking forward to the arrival of the newspapers the next morning for fuller particulars.

Chapter Seven.

The Casteltons and Gouls.

In those days, when coaches only ran on the great high roads, and postal arrangements were imperfect, even important news was conveyed at what would now be considered a very slow rate.

Adam knew no one in London to whom he could write about the little girl he had saved from the wreck, and many days passed before he could get to Morbury, the nearest town to Hurlston. It was a place of some importance, boasting of its mayor and corporation, its town-hall and gaol, its large parish church, and its broad high street.

Adam first sought out the mayor, to whom he narrated his story. That important dignitary promised to do all in his power through his correspondents in London to discover the little girl’s friends, but warned him that, as during war time the difficulties of communication with foreign countries were so great, he must not entertain much hope of success. “However, you can in the meantime relieve yourself of the care of the child by sending her to the workhouse, or if you choose to take care of her, her friends, when they are found, will undoubtedly repay you, though I warn you they are very likely, after all, not to be discovered,” he added.

“Send the little maiden to the workhouse!” he exclaimed, as, quitting Mr Barber’s mansion, he pressed his hat down on his head; “no, no, no; and as to being repaid by her friends, if it was not for her sake, I only hope they may never be found.”

The lawyer, Mr Shallard, on whom Adam next called, had the character of being an honest man, and having for many years been Sir Reginald Castleton’s adviser, he was universally looked up to and trusted by all classes, except by these litigants who were conscious of the badness of their causes.

He was a tall, thin man, of middle age, with a pleasant expression of countenance. He listened with attention to Adam’s account of his rescuing the little girl, but gave him no greater expectation of discovering her friends than had the mayor.

“You will, I suspect, run a great risk of losing your reward,” he observed; “but if you are unwilling to bear the expense of her maintenance, bring her here, and I will see what can be done for her. Of course, legally, you are entitled to send the foundling to the workhouse.”

“You wouldn’t advise me to do that, I’m thinking,” said Adam.

“No, my friend, but it is my duty to tell you what you have the right to do,” answered the lawyer.

“Well, sir, I’d blush to call myself a man if I did,” replied the fisherman, and without boasting of his intentions, he added that he and his dame were quite prepared to bring up the little girl like a daughter of their own.

When Adam offered the usual fee, the lawyer motioned him to put it into his pocket.

“Friend Halliburt, you are doing your duty to the little foundling, and I will do mine. If her friends can be found, I daresay I shall be repaid, and at all events, when you come to Morbury again you must call and let me know how she thrives.”

Adam, greatly relieved at feeling that, having done what he could towards finding the child’s friends, there was great probability that she would be left with him and his wife, returned home.

“Any chance of hearing of our little maiden’s friends?” asked the dame, on Adam’s return.

“None that I can see, mother,” he answered, taking his usual seat in his arm-chair. “As it seems clear that they are in foreign lands, those I have spoken to say, now that war has broken out again, it will be a hard matter to get news of them.”

“Well, well, you have done your duty, Adam, and you can do no more,” answered his wife, looking much relieved. “If it is God’s will that the little girl should remain with us, we will do our best to take care of her, that we will.”

“What do you think, though?” he continued, after he had given an account of his first visit; “Mr Mayor advises us to send her to the workhouse. It made my heart swell up a bit when he said so, I can tell ye.”

“Sure it would, Adam,” exclaimed the dame; “little dear, to think on’t.”

“Mr Shallard said something of the same sort too, but he showed that he has a kind heart, for he told me to bring the child to him if we didn’t want to have charge of her, and when I offered his fee he wouldn’t even look at it.”

“Good, good!” exclaimed the dame; “I’ve no doubt he’d act kindly by her, but I wouldn’t wish to give her up to him if I could help it. It’s not every one who would have refused to take his fee, and it’s more, at all events, than old Lawyer Goul would have done, who used to live when I was a girl where Mr Shallard does now. There never was a man like him for scraping money together by fair means or foul. And yet it all went somehow or other, and there was not enough left when he died to bury him, and his poor heart-broken, crazy wife was left without house or home, and went away wandering through the country no one knew where. Some said she had cast herself into the sea and was drowned; but others, I mind, declared they had seen her after that as wild and witless as ever. Hers was a hard fate whatever it might have been, for her husband hadn’t a friend in the world, no more had she; and when she went mad there was no one to look after her.”

Then Dame Halliburt told a tale, interrupted by many questions by the good Adam, of which this is the substance.

Lawyer Goul had a son, and though he and his wife agreed in nothing else, they did in loving and in spoiling that unhappy lad. He caused the ruin of his father, who denied him nothing he wanted. Old Goul wouldn’t put his hand in his pocket for a sixpence to buy a loaf of bread for a neighbour’s family who might be starving, but he would give hundreds or thousands to supply young Martin’s extravagance. He wanted to make a gentleman of his son, and thought money would do it. His son thought so too, and took good care to spend his father’s ill-gotten gains. As he grew up he became as audacious and bold a young ruffian as could well be met with. He had always a fancy for the sea, and used often to be away for weeks and months together over to France or Holland in company with smugglers and other lawless fellows, so it was said, and it was suspected that he was mixed up with them, and had spent not a little of his father’s money in smuggling ventures which brought no profit. Old Martin Goul had wished to give his son a good education, and had sent him to the very same school to which the sons of Dame Halliburt’s master, Mr Herbert Castleton, went. There were two of them, Mr Ranald and Mr Ralph. Mr Herbert was Sir Reginald Castleton’s younger brother. He was a proud man, as all the Castletons were, and hot-tempered, and not what one may call wise. He was sometimes over-indulgent to his children, and sometimes very harsh if they offended him. For some cause or other Mr Ranald, the eldest, was not a favourite of his, though many liked him the best. He was generous and open-hearted, but then, to be sure, he was as hot-tempered and obstinate as his father. While he was at college it was said he fell in love with a young girl who had no money, and was in point of family not a proper match for a Castleton. Some one informed his father, who threatened to disown him if he married her. He could not keep him out of Texford, for he was Sir Reginald’s heir after himself. This fact enraged him still more against his son, as he thus had not the full power he would have liked to exercise over him. When Mr Herbert married, his wife brought him a good fortune, which was settled on their children, and that he could not touch either. They had, besides their two sons, a daughter, Miss Ellen Castleton, a pretty dark-eyed young lady. She was good-tempered and kind to all about her, but not as sensible and discreet as she should have been.

When Mr Ranald and Mr Ralph left school young Martin Goul, whose character was not so well known then as it was afterwards, came to the house to pay them a visit. As they had been playmates for some years, and he dressed well and rode a fine horse, they seemed to forget that he was old Martin Goul’s son, and treated him like one of themselves. To my mind, continued the dame, nothing belonging to old Goul was fit to associate with Mr Castleton’s sons. Once having got a footing in the house, he used to come pretty often, sometimes even when the young gentlemen were away from home, and it soon became known to every one except Mr and Mrs Castleton that Lawyer Goul’s son was making love to Miss Ellen. She, poor dear, knew nothing of the world, and thought if he was fit to be a companion of her brothers, it was no harm to give her heart to him. She could see none of his faults, and fancied him a brave, fine young fellow, and he could, besides, be as soft as butter when he chose, and was as great a hypocrite as his father. He knew it would not do to be seen too often at the house, or Mr and Mrs Castleton would have been suspecting something, and so he persuaded Miss Ellen to come out and meet him in the park, and she fancied that no one knew of it. This went on for some time till Mr Ranald and Mr Ralph came home from college. One evening, as Mr Ranald was returning from a ride on horseback, and had taken a short cut across the park, he found his sister and Martin Goul walking together in the wood. Now one might have supposed that if the account of his own love affair was true he would have had some fellow-feeling for his sister and old schoolmate, and not thought she was doing anything very wrong after all, but that wasn’t his idea in the least. Without more ado he laid his whip on Martin’s shoulders, and ordered him off the grounds, much as he would a poacher. Martin, the strongest of the two by far, would have knocked him down if Miss Ellen had not interfered and begged Martin to go away, declaring that if fault there was it was entirely hers. Martin did go, swearing that he would have the satisfaction one gentleman had a right to demand from another. Mr Ranald laughed at him scornfully, and, taking Miss Ellen’s arm, led her back to the house.

Mr Ranald was not on the terms, as I have said, which he should have been with his father or even with his mother, so he said nothing to them, but taking the matter into his own hands, told his sister to go to her room and remain there. She, as I said, was a gentle-spirited girl, and did as she was bid, only sitting down and crying and wringing her hands at the thoughts of what might come of what she had done. Poor dear young lady, she told me all about it afterwards, and I thought her heart would break; and I was not far wrong, as it turned out at last.

Now, though Mr Ranald and Mr Ralph were not on affectionate terms as brothers should be, and were seldom together, they were quite at one in this matter. Mr Ralph was by far the more clever, and had gained all sorts of honours at college we heard; so that Mr Ranald looked up to him when there was anything of importance to be done, and took his opinion when he wouldn’t have listened to any one else.

The brothers were closeted a long time together talking the matter over, as they thought very seriously of it, and considered that the honour of the family was at stake. They then got their sister to come to them, and tried to make her promise never to see young Martin Goul again; but notwithstanding all they could say, gentle as she was in most things, she would not say that. They warned her that the consequences would be serious to all concerned.

Martin Goul was as good as his word. He got another young fellow who passed for a gentleman, something like himself, to carry a challenge to Mr Ranald. The young fellow did not like to come into the house, so he waylaid Mr Ranald near the entrance of the park, and delivered a letter he had brought from Martin Goul. Mr Ranald, as soon as he found from whom it came, tore it up, and throwing it in the messenger’s face, so belaboured him with his whip, that he drove him out of the park faster than he had come into it.

Mr Ralph had, however, in the manner he was accustomed to manage things, taken steps to get Martin Goul out of the way. The last war between England and France had just begun; the pressgang were busy along the coast obtaining men for the navy. Mr Ralph happened to know the officer in command of a gang who had the night before come to Morbury. He told him, what was the truth, that young Martin was a seafaring man, and mixed up with a band of smugglers, and he hinted to the officer that he would be doing good service to the place, and to honest people generally, if he could get hold of the young fellow and send him away to sea. Martin was seized the same night, and before he could send any message home to say what had happened, he was carried to a man-of-war’s boat lying in the little harbour of Morbury, ready to receive any prisoners who might be taken. He was put on board a cutter with several others who had been captured in the place, and not giving him time to send even a letter on shore, she sailed away for the Thames, and he was at once sent on board a man-of-war on the point of sailing for a foreign station. Miss Ellen, when she heard what had happened, was more downcast and sad than before, and those who knew the secret of her sorrow saw that she was dying of a broken heart.

Poor Mrs Castleton had been long in delicate health, and soon after this she caught a chill, and in a short time died. Miss Ellen was left more than ever alone. From the day she last saw her worthless lover she never went into society, and seldom, indeed, except at church, was seen outside the park-gates.

Mr Castleton himself had become somewhat of an invalid, which made his temper even worse than before. He showed it especially whenever Mr Ranald was at home, and I am afraid that Mr Ralph often made matters worse instead of trying to mend them.

At last Mr Ranald left home altogether, for as he had come into a part of his mother’s property, he was independent of his father. Some time afterwards a letter was received from him saying that he had sailed for the Indies. Whether or not he had married the young lady spoken of at college was not known to a certainty.

As may be supposed, old Martin Goul and his poor witless wife were in a sad taking when they found that their son had been carried off by a pressgang. Old Goul vowed vengeance against those who had managed to have his son spirited away. His own days, however, were coming to a close. He found out the ship on board which young Martin had sailed, and he tried every means to send after him to get him back. That was no easy matter, however; indeed, the money which he had scraped together and cheated out of many a lone widow and friendless orphan had come to an end. No one knew how it had gone, except, perhaps, his son. He himself even, it was said, could not tell, though he spent his days and nights poring over books and papers, trying to find out, till he became almost as crazy as his wife. No one went to consult him on law business, except, perhaps, some smuggler or other knave who could get no decent lawyer to undertake his case, and then old Goul was sure to lose it, so that even the rogues at last would not trust him.

He and his wife had had for long only one servant in the house. A poor friendless creature was old Nan. One day the tax-gatherer called when Martin Goul, who was seated in his dusty room which had not been cleaned out for years, told him that Nan had the money to pay, and that he would find her in the kitchen. He went downstairs and there, sure enough, was poor Nan stretched out on the floor. She had died of starvation, there was no doubt about that, for there was not a crust of bread in the kitchen, nor a bit of coal to light a fire. How Martin Goul had managed to live it was hard to say, except that his wife had been seen stealing out at dusk, and it was supposed that she had managed to pick up food for herself and her husband.

Meantime it was known that young Martin had been aboard the Resistance frigate, which had gone away out to the East Indies. At last news came home that the Resistance had been blown up far away from any help in the Indian seas, and that every soul on board had perished or been killed by savages when they got on shore.

Mr Ralph tried to keep what had happened from the ears of his sister, but she was always making inquiries about the ships on foreign stations. At last one day she heard what it would have been better she had never known. We found her in a dead faint. She was brought to, but the colour had left her cheeks and lips, and she never again lifted up her head. Mr Ralph came to see her.

“It was all your doing,” she said to him in a reproachful tone. “He might have been wild, he might have been what you say he was, but he promised me that he would reform and be all I could wish.”

“Of whom do you speak, Ellen,” asked Mr Ralph.

“Of him who now lies dead beneath the waters of the Indian Ocean, of Martin Goul,” she said, and uttered a cry which went to our hearts.