The Project Gutenberg EBook of The New Forest Spy, by George Manville Fenn

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The New Forest Spy

Author: George Manville Fenn

Illustrator: W.D.E. Evans

Release Date: November 15, 2007 [EBook #23502]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NEW FOREST SPY ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

George Manville Fenn

"The New Forest Spy"

Chapter One.

An Encounter in the Wood.

“Hullo! What’s that?”

The lad who uttered those words dropped a short, stiff fishing-rod in amongst the bracken and furze, and made a dash in the direction of a sharp rustling sound to his right, ran as hard as he could, full-pelt, for about five-and-twenty yards, and then, catching his toe in a tough stem of heather, went headlong down into a tuft of closely-cropped furze—the delicate finer kind—which had been nibbled off year after year till it had assumed the form of a great green-and-gold cushion, beautiful to look at, but too pointed in its attentions to make a pleasant resting-place.

“Bother!” shouted the boy, as he scrambled up. “Oh, what an ass I am! Anyone would think I was old enough to know that I couldn’t catch a rabbit on the run, even if he had no hole among the hazel-stubbs. Hole? Hundreds, where he could dive down. Horrid, prickly things furzes are. That was a sharp one; but there, it hasn’t hurt much, only it makes one so jolly hot.”

He walked backward along the edge of the forest much more deliberately to stoop and pick up his rod.

“Yes, of course,” he grumbled, and he screwed up a rather good-looking young manly face into a grin of annoyance which shewed all his closely set white teeth; “I might have known—all in a tangle. The hook broken, of course!”

He let the butt of the rod which bore a very old-fashioned brass winch, rest in the hollow of his arm, while he carefully extricated the hook at the end of his line from where it had fallen and caught hold of a stem of dwarf bracken, while to free it and the hair, feather, and dubbing which had transformed the said hook into what was supposed to be a big artificial fly, although it was not in the slightest degree like any insect that ever flew, required no little care.

“Humph!” he grunted; “might have been worse. But what a stupid a trout must be to go at a thing like that! Well, so much the better for me. Now then: once more, to begin.”

But the boy seemed in no hurry to start. His exertions, though slight, had made him very hot, and he took off his cap to wipe away the shining drops that covered his sun-tanned forehead and stood thickly where, higher up, the skin was white amongst the thickly set curls of his brown hair.

He looked round at a common-like portion of the New Forest over a slightly undulating stretch of velvety grass, bracken, heather and stunted oak-trees, which gave the place a park-like aspect, running right up to where the oaks were clustered thickly, with an occasional silvery or ruddy barked birch, and made dense with hazel-stubbs and alder.

“Oh, what a jolly day!” he said; “but isn’t it hot!”

It was, for the autumn sun shone down out of a vivid blue sky upon the gloriously green growth which was beginning here and there to look mellow and ripe as if shot with ruddy gold.

“I might just as well lie down and read under the shade of one of the trees,” mused the boy, “for the trout will be all in the most cranky places right under the stones and roots. But one can’t read without a book, and I came out on purpose to catch something, and I mean to do it; so here goes.”

He made for the nearest portion of the forest, and plunged in at once, holding his fly carefully between finger and thumb, and shouldering his rod so that, as he walked on with the trees clustering thicker and thicker, he drew the top after him, and got on fairly well without entangling his line.

Deeper and deeper into the forest, which grew more and more dense, till, breaking away from its level, it suddenly began to descend in a stiff slope, which rose as steeply fifty yards farther on, forming in all a wandering, tangled little valley, at the bottom of which trickled and gurgled a tiny river some few yards wide, flashing brightly in places where the sun passed through the overhanging trees, but for the most part darkly hidden, and only to be approached with some little difficulty and at the risk of being caught and held by one of the briars’ hundred hands.

The valley was very beautiful, gloriously attractive, and evidently a very sanctuary for blackbirds, one of which every now and then darted out in full velvet plumage, skimmed a few yards, and then dived out of sight again.

They were too common objects to take the boy’s attention as he cautiously made his way towards the edge of the little river, but he did stop for a minute as a loud yuk, yuk, yuk, rang out, and a good-sized bird made a streak of green, and, once well in the sunshine, of brilliant scarlet, as it flew over the bushes and amongst the trees in a series of wave-like curves before it disappeared.

“That’s the greenest woodpecker and the reddest head I have seen this season,” said the boy thoughtfully. “That’s a fine old cock-bird, and no mistake. Well, green woodpeckers aren’t trout, and he wouldn’t take my fly if I dropped it near him, and I don’t want him to. Now, then, what do you say to a try here?”

The lad asked himself the question, and responded by going on cautiously for about a dozen yards through about the most unsuitable pieces of woodland possible for a fly-fisher to try his craft.

But Waller Froy, only son of the Squire of Brackendene, was not going to wield a twelve-foot fly-rod, tapering and lissom, and suitable for sending a delicate line floating through the air to drop its lure lightly on the surface of the water. Such practices would have been utterly impossible on any part of the woodland rivulet. But, all the same, he knew perfectly well what he was about, and how to catch the large, fat, dark-coloured, speckled beauties that haunted the stream—the only way, in fact, unless he had descended to the poacher-like practice of “tickling,” and that he scorned.

Waller’s way was to proceed cautiously through the undergrowth without stirring bough or leaf till he came to some opening on the bank where he could see the dark, slowly gliding stream, or perhaps eddy, through the overhanging boughs.

Then, with his fly wound up close to the top ring of his short rod, he would pass it through the leaves and twigs with the greatest care and unwind again, letting the fly descend till it dropped lightly on the surface. This he did patiently in fully a dozen different places, winding up after each attempt, and then cautiously following the edge of the stream to try again wherever he came upon a suitable spot. But upon that particular occasion the trout were not at home at the lairs he tried, or else not hungry, so the fly was drawn up again for fresh trials.

“It’s too hot,” muttered the boy.

But he had all the good qualities of a fisherman, including patience and perseverance, and he went on and on deeper and deeper into the forest, managing so skilfully that he never once entangled his line.

It was very beautiful there in the soft shades. The sun was almost completely shut out, and in some of the openings the pools looked absolutely black, while Waller, perfectly confident that there were plenty of good pound trout lurking in this hiding-place of theirs, went on and on.

He had left the outskirts of the forest far behind, threading the rugged oaks, to make his way through the undergrowth that flourished amongst the beeches—huge forest monarchs that had once been pollarded by the foresters of old, to sprout out again upon losing their heads into a cluster of fresh stems, each a big tree—so ancient that, as the boy gazed back at them from where he wound his way in and out, following the curves and zigzags of the little river, he asked himself why it was that this tract of land was called the New Forest, where everything looked so old.

“How stupid!” he muttered, the next moment. “I forgot. Of course, it was because William Rufus made it for hunting in. It was new then if it isn’t now. I wonder whether he ever fished for trout,” added the boy, with a laugh. “Good thing for him if he had; people who go fishing don’t often get shot. Ah! there ought to be one here.”

The denseness of the briars and wild-rose tangles had forced him to make a détour, and now, on drawing near the river again, he came upon so likely a spot that, practising the greatest caution, he dropped his big ugly fly through what was quite a hole in the overgrowth of verdure, beneath which the water lay still and dark.

He was quite right. He felt that there ought to be a fish there waiting for some big fat caterpillar or fly to drop from the leaves above; and his ugly lure had hardly touched the surface of the water before there was a loud smack, a disturbance as if a stone had been thrown in to fall without a splash, and a well-hooked trout was darting here and there at the end of the short line, making frantic struggles to escape.

But though Waller Froy had so many yards of twisted silk upon his winch for the convenience of lowering and winding-in his bait, the tangle of bushes and overhanging boughs necessitated fishing with a tight line, with trust in its strength for the rapid hauling out of the prize.

It was no question of skill, but the roughest of rough work; and after a few rapid plunges and splashes, the fish was lifted out on to the bank, to begin leaping and making the first steps to entangle the line amongst the twigs which rose everywhere about the boy’s knees.

“What a beauty!” he cried, as he released his hook, placed his prize in his creel, and proceeded to examine his ruffled fly, getting it ready for tempting another fish.

This was tried for in a similar place about a dozen yards farther along the river, but without result; and on stepping onwards the river wound along a dell amongst the great beech trees, with the sunlight flashing from the surface and turning to bronzed silver patch after patch of bracken that spread its broad fronds in glistening sheets five and six feet high.

There was no tempting fishing-place here among the broad slopes, but beyond there was more than one favourite spot from which in times past the boy had taken many a speckled beauty, and to reach one of these he was pressing on with arms raised, and creel and rod held high, simply wading, as it were, through the rustling bracken, and every now and then beating back some frond that attacked his face, when, all at once, he stopped short, with his heart beating fast, for there was a quick rush, and something sprang up from almost at his feet and dashed away.

The bracken was so thick that all he saw was the quivering fronds, and, with no other thought than to catch a glimpse of the deer he had started from its lair, Waller rapidly gave a turn to the ferrule which made one rod of its two joints, and, using the butt to strike right and left at the ferns which impeded his way, he dashed on for about a dozen yards, and then stopped short. For he had brought his quarry to bay, forcing it to turn upon him fiercely, while the boy’s heart beat faster still from the exertion mingled with his startled surprise.

But it was no fat buck with palmated antlers ready to be thrown forward for a fierce attack, for in his rapid glance amongst the bracken Waller found himself face to face with a lad of about his own age—no poaching gipsy, given to preying upon the indwellers of the forest, but a strange-looking, wild-eyed being, sunken of cheek, hollow of eye, and with long unkempt hair hanging about his shoulders. Yet he was no threatening beggar, for, in spite of his garments being muddied, stained, and torn, he was well dressed, but menacing of aspect all the same; for as he stood there, bareheaded and fierce, there was danger in his dark flashing eyes, and a gleam of white, as, like those of some animal, his thin lips were drawn from his glistening teeth.

“Who are you? What do you want?” cried Waller, in his excitement; while, as the words left his lips, there was a quick movement upon the stranger’s part, and he felt for and drew something from his breast.

The next moment he was presenting a big flintlock pistol at his pursuer’s head.

Chapter Two.

A Surrender.

Waller had a glimpse of the pistol as it was suddenly presented at his head, and then he only saw what seemed to be a round, rusty ring, through which he peered at nothing, but in full expectation of seeing a puff of smoke and hearing a report, while in the quick flash of thought that darted through his brain, the question he asked himself was, “Will it kill me?”

But he did not stop to think, in this startling, novel position, for he acted simultaneously. As quick as his thought he gave a turn to the lower joint of his rod, separated the two pieces, and delivered a cut with the butt end, which took effect upon the presented weapon, knocking it out of its holder’s hands, and then, tossing the rod aside, he sprang forward and closed, while the stranger, breathing hard, finding himself unarmed, tried to get a grip at his adversary’s throat, failed, and wound his arms well round him instead, following this up by trying to lift Waller from the ground and throw him backward.

The next moment the beautiful little miniature tropic forest of ferns was faring badly, being kicked, broken, and trampled down as the two boys, breathing hard and panting with their exertions, swayed here and there, and wherever they planted foot there came up a curious crackling sound, for beneath the huge trees the earth was thickly covered with beechmast.

“Brute—savage!”

Whop!

The dull sound was caused by the wild-looking young stranger coming down flat upon his back. For after a brief struggle, during the first part of which he was furious and strong, all his power seemed to depart at once like a blown-out flame, while Waller, who had grown stronger moment by moment, and hotter with temper as he wrestled here and there, put an end to the struggle as cleverly as any wrestler by heaving up the frantic youth, and falling with him to the earth.

For quite a minute they lay motionless, arms interlocked and chest to chest, their breath coming and going with a hoarse, harsh sound, and their eyes glaring as they looked defiance one at the other. Then, as the conquered stranger’s face grew more savage, Waller’s, in his triumph, slowly softened down into a smile, and as he recovered his breath, he said triumphantly:

“Done you, in spite of your old pistol! I say, was it loaded?”

There was no reply, but the panting of the stranger’s breast seemed to grow louder.

“You coward!” he groaned out, at last, in a despairing tone.

“Ha, ha!” laughed Waller. “Brute, savage, and now coward! Why, you were the coward to aim at me with a pistol when I had nothing but a stick. Suppose it had gone off!”

“I wish it had,” panted the prostrate boy, with a vicious look.

“What! Why, it might have killed me!” cried Waller.

“I wish it had,” repeated the boy viciously.

“Stuff! You are savage because you are beaten.”

“Get off!” cried the stranger; and he made a desperate effort to throw his adversary from his chest, but only for Waller to wrench out his hands plant them upon the other’s breast, and thrust him down helpless and exhausted, while he raised himself up, got well astride, and sat up, laughing in the stranger’s face, as he raised one hand and dragged the strap of the creel over his head and tossed it aside.

“Got rid of you,” he muttered. “There, it’s no good,” he cried. “I have you quite tight. If you try to get up again I will give you such a drubbing.”

“Oh–oh!” groaned the boy addressed, passionately; and his breast heaved with the despairing, hysterical sobs that struggled for utterance.

“Ah, that’s right!” cried Waller. “You had better lie still. I am too strong for a fellow like you.”

“Yes,” panted the other; “I’m beaten. It’s all over now.”

“Then you give in?” cried Waller, who grew more and more excited in his triumph, while he gazed down at the distorted countenance beneath him, wondering who the lad was and why there was a something un-English in his accent and the turn of his words, though they sounded native all the same.

“Yes, I give up,” panted the boy; “and you can be proud of having mastered a poor starving wretch who never did you any harm.”

“No, because I stopped you,” cried Waller. “Who are you, and where did you steal that pistol?”

“It was my own,” said the other proudly.

“But what were you doing with that pistol here?—poaching, I suppose? Lucky for you my fine fellow, that I stopped you. Do you know what would have happened to you if you had killed one of the deer? Ha, ha, ha! Killed one of the deer! Why, you could not have hit a haystack with that thing.”

“Deer!” cried the lad. “I did not want to kill the deer.”

“Don’t believe you!” cried Waller.

The lad’s face flushed, and an indignant flash darted from his eyes.

“How dare you doubt my word of honour,” he cried. “Here, let me get up.”

“Shan’t! Lie still!” shouted Waller, flinging out his doubled fist and holding it within a few inches of his prisoner’s nose. “Your word of honour, eh? Why, who do you call yourself, my dirty, ragged Jack, with your honour! Who are you, and where do you come from?”

“Yes, you are a coward,” said the lad bitterly, “or you would not insult a gentleman lying weak and helpless at your mercy.”

Waller felt a little touched.

“Oh, I don’t want to insult you,” he said: “and perhaps I am as much of a gentleman as you are. But look here; who are you?”

“You know,” said the lad bitterly. “I give up, I tell you. Be content that you have got the upper hand of me. I won’t struggle against fate; only make me one promise,” he continued, in a bitter, mocking tone.

“Well, what is it?” said Waller.

“Come and see your prisoner hung, for I suppose your brutal Dutchmen will not have me shot.”

“I say,” said Waller, staring more wonderingly than ever at his prisoner, “you are using very fine language. Are you a bit off your head? Who wants to hang or shoot you? What Dutchmen?”

“The enemy—the brutal soldiery, of course.”

“I say, look here, I don’t know what you are talking about,” said Waller, “and I don’t know who you are, only that you jumped out at me like a highwayman with a pistol. I say, what are you?”

“One of the spies, I suppose,” said the boy mockingly. “One of the poor unfortunate wretches you people are hunting through the woods.”

“Nonsense!” cried Waller. “You must be fancying all this. There are no soldiers here hunting people. Do you know where you are?”

“Yes; in the New Forest.”

“That’s right, and in the part my father holds the shooting over. But,” continued Waller, showing his white teeth, “he wouldn’t want to shoot you if he were at home; you are not fat enough. Pooh! Nobody would want to shoot a boy like you.”

“Boy! Who do you call a boy?” cried the poor fellow, flushing up again.

“Why, you, of course. You are no older than I am, and I am a boy.”

“Well, never mind that. You have made me a prisoner. What are you going to do next?”

“Well, I think I am going to pick up that pistol, wherever it lies.”

“Bah!” cried the prisoner. “I only did it to scare you off. It isn’t loaded.”

“Oh!” said Waller. “Well, that’s one to you. I couldn’t tell.”

“What are you going to do with me now?” said the lad haughtily. “Chain me?”

“Chain you!” said Waller, laughing, “why, you are not a dog. I am not going to do anything with you. I don’t want you.”

“No; but you want the blood-money, I suppose.”

“There you go again,” cried Waller pettishly. “Chains and blood! I say, do you know what you are talking about? Blood-money?”

“Yes; the reward for taking me.”

“Reward! For taking you?”

“Yes, where are your bloodhounds?”

“Well, you are a rum chap,” said Waller, laughing. “You talk like a fellow in a romance. We have no bloodhounds. We have a pointer, a water-spaniel, and a retriever. Why, what sort of an idea have you got in your head about bloodhounds hunting you?”

“I—I meant the soldiers,” said the poor fellow faintly: and his eyes began to close. “Let me sit up, please. I think I’m dying.”

Chapter Three.

On Parole.

The words sounded so real, and there was such a deathly aspect in the pallor and the cold perspiration that started upon the prostrate lad’s ghastly-looking face, that Waller was convinced at once, and quickly rising from where he sat he bent over and raised the lad’s head a little, but only to lay it down again as the poor fellow fell back quite insensible.

But the attack passed off as quickly as it had come, and, relieved by the removal of the heavy pressure upon his chest, he began to breathe more freely, his eyes opened slowly in a wild stare of wonder as if he could not comprehend where he was, and then, as his senses fully returned, a faint smile dawned upon his thin lips.

“Don’t laugh at me,” he said. “It was like a great girl. I must have fainted dead away.”

“Yes, you did, and no mistake,” said Waller. “Come down to the stream and have a drink of water.—If I let you get up you won’t try to escape?”

“No,” said the lad bitterly, as he raised one hand, and let it fall again heavily amongst the bracken. “I am as weak as a child.”

“Yes,” said Waller, “you are. Now, look here; you remember what you said about the honour of a gentleman?”

The lad bowed his head slightly.

“You are a gentleman?”

“Yes.”

“Then give me your word that you won’t try to escape.”

“I will not try to escape. I could not if I wished. I tell you it is all over now, I am taken at last.”

“I say,” cried Waller, gazing at the poor fellow anxiously, “why are you here? What have you done?” And then slowly, and in almost a whisper, as he glanced sharply round for the pistol, “You haven’t killed anybody, have you?”

“Killed! No! What have I done? Nothing that should disgrace a gentleman. Nothing but fight for the cause of my lawful king.”

Waller looked at the lad curiously, for his words and the wildness of his looks again brought up the idea that he was a little off his head.

“But I say,” he said, “if you were fighting, as you call it, for your lawful king, why should the soldiers be after you?”

“Because I am an enemy—a follower of the Stuarts.”

“Oh,” said Waller, in a puzzled tone, as the lad slowly and painfully rose and then snatched at something to save himself, for he reeled. “Here, I say, you are weak,” cried Waller, saving him from falling, “lean on me. The stream is just over there,” and he led his feeble adversary down the slope to the nearest opening where he could lie down and reach over the bank to drink from the clear water in the most ancient and natural way—that is, by lowering his lips till they touched the surface.

The lad drank deeply, and then rose to a sitting position, making no effort to stand.

“Ah,” he said faintly, “I feel better now. There,” he went on, “I suppose you didn’t know the soldiers were here?”

Waller shook his head, content to listen.

“They are; and you know all about the trouble—about the Stuarts making another stand for their rights?”

“Oh, not much,” said Waller. “I have read, of course, about the Old Pretender and the Young Pretender.”

“Pretenders!” said the lad bitterly. “Those who fought for their rights as heirs to the British Crown. They are at rest, but an heir still lives, and it is his fortunes we follow.”

“Oh,” said Waller thoughtfully. “Yes, I have heard of him—in France,” and he looked more curiously in the other’s eyes as he asked his next question, thinking the while of the slight accent in the lad’s speech.

“But you have not come from there?”

“Yes,” said the lad quietly, and with a bitter tone of sadness in his words; “we crossed over from Cherbourg—oh, it must be a month ago.”

“We?” said Waller inquiringly.

“Yes; I came with my father and four other gentlemen to Lymington.”

“And are they here in the forest?”

The lad looked at him wonderingly.

“No,” he said; “they were all hunted down like wild beasts—treated as spies.”

“And where are they now?” said Waller eagerly.

“Who knows?” replied the lad sadly. “Lingering in prison, if they have not already been shot. Quick! Tell me,” he continued, catching Waller by the arm. “My father! Have you heard anything about him?”

“I? No,” said Waller. “Oh, surely not shot! But in this quiet country place at the Manor we hear so little of what is going on. I can’t help being so ignorant about all these things.”

“You are all the happier, perhaps,” said the lad sadly.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Waller. “I am afraid I don’t know much about what’s going on. I am fond of being out here in the woods. It is holiday-time now my father’s out. But I say,” he continued, with a frank laugh, “isn’t it rather funny that you and I should be talking together like this, after—you know—such a little while ago?”

“Yes, I suppose so; but I thought you were one of the enemy coming to take me.”

“Yes,” said Waller; “and I don’t know what I thought about you when I was looking down the barrel of that pistol.”

“I—I beg your pardon,” faltered the lad. “I was half-mad.”

“Quite mad, I think,” said Waller to himself. Then aloud, “But, I say, why were you here?”

“I was hiding; trying to get down to the coast and make my way back to France. The soldiers have been hunting me for days, but I have escaped so far.”

“To get back to France?” said Waller. “But are you not English?”

“Yes, of course. Don’t I speak like an Englishman?”

“Well, there is a little something queer about it,” said Waller—“a sort of accent.”

“I said English,” continued the other, “but my family, the Boynes, are of Irish descent, and staunch followers of the Stuarts.”

“Yes; but that’s all over now, you know,” said Waller. “Don’t you think you had better give all that up and go back?”

“I was trying to go back,” said the lad despairingly.

“Or stop here.”

“You talk like a follower of the Pretender,” said the lad bitterly.

“That I don’t!” cried Waller indignantly. “My father is a magistrate, and a staunch supporter of King George. But there, I didn’t mean to talk like that,” he cried, as he noted the change that came over his companion’s face. “Here, I say, never mind about politics. You look—well, very ill. Hadn’t you better go home?”

“Go home! How? Separated from my friends, who perhaps by now are dead!” The words came with a sob, “Go! How? Hunted from place to place like a wolf!” He tried to rise, but sank back. “Ill? Yes,” he groaned; “deadly faint. You don’t know what I have suffered. I am starving.”

“How long have you been here?” said Waller, whose sympathies were growing more and more strong in favour of his prisoner.

“I don’t know. Days.”

“But why were you starving?” said Waller half-indignantly.

“Why should I not be?” said the boy bitterly. “Alone in these wilds.”

“Well,” cried Waller. “I shouldn’t have starved if I had been like you. I should have liked it, and had rather a jolly time,” and he gazed hard at the delicate-looking lad, whose very aspect, in spite of his disorder, suggested that he had led a gentle life, possibly mingling with the followers of the Court.

The gaze was returned—a gaze full of wonderment.

“What would you have done?” said the stranger. “Eaten the bitter acorns and the leaves?”

“No,” cried Waller, laughing, “I should just think not! Why, I should have done as Bunny Wrigg would—scraped myself out a good hole in the side of one of the sandpits, half-filled it with dry bracken for my bed, made a corner for my fire somewhere outside, and then had a good go in at the rabbits and the fish; and there are plenty of pig-nuts and truffles, if you know how to hunt for them. There are several places where you can get mushrooms out in the open part among the furze where the grass grows short; and then there’s that kind that grows on the oak-trees. You can trap birds, too, or knock over ducks that come down the stream if you are lucky. I have several times got one with a bow and arrow. Oh, there are lots of ways to keep from starving out in the woods.”

“Ah,” said the lad feebly, “you are a country boy. I come from French cities, and know nothing of these things.”

“Oh!” said Waller thoughtfully. “What have you had to eat this morning?”

The boy laughed sadly. “I have picked some leaves,” he said.

“Picked some leaves!” cried Waller contemptuously. “Why didn’t you hunt for some of the hens’ eggs? There are lots about here, half-wild, that have strayed away from the farms and taken to the woods. Of course a raw egg is not so good as one nicely cooked, but it would keep a fellow from looking as bad as you do. Here, I say, I am sorry that I knocked you about so. I didn’t know that you were so bad as this.”

“It doesn’t matter now,” was the reply. “You had better give me up to the soldiers at once. I suppose they will give me something to eat. My pride’s all gone now, and I only want to get it over and bring it to an end. It’s very contemptible, I know, but it is very horrible, all the same.”

“What is?” said Waller quickly.

“To feel that you are starving to death.”

“There, now you are talking nonsense,” said Waller warmly. “Why, of course it is. Who’s going to starve to death? Here, I suppose I oughtn’t to help you?”

“No; I am an enemy. Give me up to the soldiers as quickly as you can.”

“Bother the soldiers!” cried Waller hotly. “Let them do their work themselves. I don’t know anything about enemies. You are half-starved and ill, and if you stop till I come back I’ll run off and get you something to eat. I could take you home with me at once, but if I did the servants would see you, and begin to talk, and then it might get to the ears of the soldiers, if there are any about. Don’t run away till I come back with them,” continued Waller, with a mocking laugh. “You don’t want any more water, do you?”

The lad shook his head.

“Then creep in there under those ferns. Nobody could see you even if he came by, and Bunny Wrigg is the only one likely to be about here. Clever as he is, I don’t suppose he would spy you out. Why, I shouldn’t have seen you if you hadn’t started up as you did. That’s right. I shan’t be long.”

Waller snatched up the two joints of his rod, and the creel which he had thrown down, and started off at a smart trot in and out amongst the great beeches, not traversing the way by which he had come, but striking a bee-line for home.

Chapter Four.

A Raid on the Larder.

Brackendene was the very model of an Elizabethan country house, with clusters of twisted chimneys, and ivy clinging to the red bricks everywhere that it could find a hold.

There was an attractive porch opening out upon the well-kept pleasaunce, but, instead of going straight to it, Waller looked sharply to right and left, saw nobody and heard nothing but a dull, distant thump, thump, and the barking of a dog from somewhere at the back.

The next minute he was through one of the dining-room casements, and crossed into the hall, where he stood listening for a moment or two to the thump, thump, which now sounded nearer.

“That’s Martha at her churn,” he muttered. “How stupid it seems! Anyone would think I was a thief.”

He felt like one as he crossed the hall, opened a big oak door cautiously, and made his way into the great red-brick-floored kitchen, where from an opening to his left the thumping of the churn came louder still, accompanied by a dull humming sound, something like the buzz of a musical bee, but which was intended by the utterer to represent a tune.

Waller nodded his head with satisfaction, and went off to his right out of the kitchen into a cool stone passage, and then through a door into a stone-floored larder, whose wire-covered, ivy-shaded windows gave upon the north.

But Waller Froy had no thought for the situation of the larder. His attention was taken up by about three-quarters of a raised pork-pie, which he took off the dish, and, after a moment’s hesitation, drew his big trout out of the creel and dabbed it in where the pie had stood, making the latter take the fish’s place in the creel.

“Make it taste a bit,” muttered the boy. “Can’t stop to find a cloth, and he will be too hungry to notice. Now for some bread.”

The larder was not his place, but the boy was quite at home there, due to surreptitious visits connected with fishing excursions and provisions for lunch.

Taking the great brown lid off a bread-pan, he placed it on the floor and pounced upon a loaf, which he broke in two and crammed into his fishing-creel. He then rose up and looked round, till his eyes lighted upon a big jug full of creamy-looking milk, which he annexed at once, and then made for the door, passed through the kitchen, where the thumping and musical buzz still went on, made his way back to the dining-room, and through the window again out into the garden, and then passed breathlessly into the dense forest once again, panting slightly from his exertions.

“I have as good a right to the things as anybody,” he muttered, to quiet his uneasy conscience, “and if Martha asks me if I took the pie I shall say yes, of course. I am not going to enter into explanations. Let her think I was hungry and wanted some lunch; and if she does think it’s my doing—oh!” he ejaculated, “she will know it was when she finds the fish; and there—if I didn’t leave the great cover of the pan on the floor! Bother!” he ejaculated. “I am master when father’s out, and I shall do as I like. Wish I could,” he grumbled, as he hurried along, not so fast as he wished, for his way was rough and tangled, and the jug of milk was very full, besides being an awkward thing to carry steadily where brambles continually crossed the path and the thorny strands of the dog-rose hung down from on high as if fishing for everyone who passed. “I should like to think about what to do,” mused Waller to himself, “but it only makes one so uncomfortable. This fellow must be one of the King’s enemies, and if I am helping the King’s enemies, shan’t I be committing high treason? Oh, bother!” he cried aloud. “I am going to give a poor fellow who is starving something to eat, and, enemy or no, I am sure if King George saw him starving he’d do the same. There, I won’t think about it any more.”

He reached the spot where he had left his new acquaintance, in a state of repentance because he had not lowered the milk by taking a good draught, the consequence being that he had spilt a good deal.

All was perfectly still, and he began to wade through the ferns, and then stopped to look straight before him, and then sharply to right and left.

“Why, he isn’t a gentleman, after all,” muttered the boy. “He’s gone. It was just in there that I told him to crawl, and—no, it was farther on, by that next beech—no—oh, I say, how much alike all these places are! I believe I must have passed it.”

He stood still and whistled. There was no reply. Then he whistled again, and, after glancing about him, hazarded a call.

“Hi! Hullo! Where are you?—It’s all right; no soldiers near.”

There was a faint rustling then amongst the bracken, and the stranger’s head was slowly raised some thirty yards away.

Waller hurried to him.

“What made you change your place?” he said, as he came up.

“Change my place? I have not moved.”

“Never mind. There, sit down now. Here’s something to take off the hunger. There, if I didn’t forget a knife! Never mind; mine will do. It’s quite clean. That’s right. Nobody’s likely to come by here. Take a good drink of this first.”

He placed the jug in the lad’s hand as he seated himself between the great buttress-like roots of a huge beech: and after that long, deep drink there was an interval of time during which Waller watched, with a feeling of wonder, the ravenous manner in which his new friend—or enemy—partook of food.

“I am ashamed,” he muttered; “I am ashamed. But eat some, too.”

“Oh, no; go on,” said Waller.

“I can’t eat another mouthful unless you join.”

“Oh, very well; there is plenty,” said Waller, “and seeing you eat has made me hungry, too.”

No more words were spoken for a time, and at last, with the hunger of both pretty well assuaged, Waller began to note the humour of the position, and in a half-bantering way exclaimed:

“Here, I say, you ought to leave a snack for the soldiers when they come.”

The lad’s hand dropped, and he turned, with a wild look, to fix his eyes on Waller’s.

“Ah,” he said, the next moment, with his face softening, “you are laughing at me.”

“Well, suppose I am. It’s because I am pleased to see you better now.”

“Better! Yes. I think you have saved my life,” said the lad softly. “I say, I wish we could be friends—but no; impossible. You could not be, with one like me.”

“I don’t see why not,” said Waller. “We are good enough friends now. There, I am sorry I knocked you about so much and treated you as I did. I didn’t know you were so weak and hungry. Will you shake hands?”

“Will I shake hands?” cried the lad, with all the effusion of a young Frenchman, and catching the one which Waller stretched out, he held it tightly for a few moments between his own, holding it until Waller drew it away.

“There,” he said, “I must be going back now. There isn’t much left, but I must have the empty basket. You had better lie down here and have a good rest, and I will come back to you in the evening and see if I can’t think out some way of helping you to get down to Lymington.”

“To Lymington? Yes!” cried the boy eagerly; for now that he was somewhat refreshed the light seemed to come back into his eyes, and a certain eagerness into his whole aspect. “But, look here,” he said, “a little while ago I thought I had nothing to do but lie down and die; now you have made me feel as if I want to live. Could you—can you find out whether there are any soldiers near?”

“I don’t know, but I’ll try,” said Waller. “But I say, talk about soldiers—we never picked up that pistol, and I don’t believe we could find it now.”

“Here it is,” said the lad, pointing to his breast. “I crawled about till I found it after you had gone.”

“Then you had better give it to me to put away. Pistols are nasty things.”

Waller held out his hand, but the lad shrank back, with a suspicious look.

“Oh, very well,” said Waller, rising; “don’t trust me unless you like.”

“I do trust you,” cried the lad eagerly; and, snatching out the pistol, he pressed it into the other’s hand.

“There, they will be wondering what has become of me,” cried Waller. “I will come back and see you in the evening, and by then I shall have thought of somewhere for you to hide to-night. Good-bye.”

Waller hurried off, thinking deeply to himself, and making the best of his way for about a hundred yards.

“I wish I hadn’t brought away his pistol,” he said. “He will be thinking again that I am going to betray him. Here, I shall take it back.”

He made his way as fast as he could to where he had left his new friend, expecting to see him raise his head as he drew dear; but he looked in vain, for when he reached the spot, and parted the tall bracken, he was unable to find him for a few minutes, and when he did, the figure was recumbent, utterly exhausted, and sleeping hard, while he did not even move as Waller bent over him and carefully thrust the pistol into his breast.

Chapter Five.

Duty or Mercy.

“Oh, here you are, Master Waller!” said Bella, as he marched into the house. “Where have you been?”

“Fishing,” said Waller abruptly.

“But why didn’t you come back to your dinner?”

“Because I have been out in the forest, and—fishing, I tell you. Why?”

“Because Martha has been in such a way. There was your dinner kept three hours, till it was quite spoiled, and then we said it was no use to keep it any longer; and Martha is in a way.”

“What about?” said Waller absently, for his thoughts were still in the forest along with the young stranger.

“Because she says she won’t put up with it, and if you are to go in and out of the pantry helping yourself to what you please, she will complain to master as soon as he comes back.”

“Oh, very well, Bella,” giving the fresh-looking servant girl a nod.

“But aren’t you hungry?”

“No.”

“Well, you are a boy! You will want something to eat with your tea, won’t you?”

“Yes, I suppose so. But I say, Bella, have you heard anything about there being soldiers in the forest?”

“Oh, yes,” said the girl eagerly. “You haven’t seen any of them, have you?”

“I? No,” said Waller quickly. “What have you heard?”

“Oh, I only heard what Tony Gusset said to Martha when he came in to talk to her last night.”

“What!” cried Waller. “Was that old stupid here last night?”

“Yes; but he wasn’t here long. Martha won’t let him stay. She soon bundles him off again. She told me that he wouldn’t be so fond of his sister if she wasn’t the cook and couldn’t ask him to have something to eat when he came. She does hate to see him here.”

“But what did he tell her?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said the girl pettishly.

“Yes, you do, Bella. Tell me.”

“Well, will you promise to be a good boy and come back to your meals at proper times, and not keep everything waiting about?”

“Oh, yes, of course. Now what was it?”

“Oh, he told her that the French had landed on the coast to turn the King off the throne and put a new foreign one on it, and that the soldiers had met them and beaten them, all but a few who were spies, and had hidden themselves in the forest; but they were catching them all till there were hardly any left, and they were looking for them. And Tony Gusset said there was a reward of a hundred pounds offered for every one that was caught, and he meant to catch one and make himself rich.”

“He had better mind his mending shoes and hammering his old lapstone,” cried Waller, with an unwonted show of anger. “What’s it got to do with him?”

“There, now, if that isn’t funny!” said the girl, clapping her hands. “Why, that’s just what Martha said to him, and he quite quarrelled with her. He said it was his duty as the village constable to apprehend all vagabonds, and that if his sister did not know how to pay him more respect he should not stoop to come and speak to her again.”

“Well done, cook!” cried Waller, laughing. “What then?”

“Why, she up and told him that he was only a lazy vagabond himself, for he never did hardly any work, and that since he had been made constable the place had not been big enough to hold him. But there, I can’t stop talking here; I have got to get your tea. What am I to say to Martha about your taking that pork-pie?”

“Nothing,” said Waller gruffly.

“But she meant it for your tea.”

“Well, I had it for lunch instead. Now go away and don’t bother.”

“Well, I am sure!” cried the girl. “What’s come to you, Master Waller? You’re as cross as two sticks.”

“Of course I am, if you stop chattering here instead of getting me my tea.”

“But it won’t be tea-time for another hour.”

“I tell you it’s always tea-time for anyone who hasn’t had any dinner, so go and get it at once.”

Bella went out of the room, and gave the door a regular whisk to make it bang, but repented directly after, and let it strike against her foot, so that it was closed quietly.

Waller jumped up from his chair in an unwonted state of excitement, as soon as he was alone, and began to walk hurriedly up and down the room.

“Then it’s all true,” he mused. “There are soldiers about, and if they catch that poor fellow they will march him off to prison—and he is so ill after being hunted about. Oh, it’s too bad!” he continued, growing more and more excited. “And there’s no knowing what they would do. Why, they hung the poor wretch who wasn’t much more than a boy for stealing that sheep; and I believe it was only because he was hungry and out of work. Here, I know I oughtn’t to interfere, but father isn’t at home, and I feel as if I ought to do something. I want to do something. It seems so horrid. Suppose it had been I who went on like that poor fellow did. I don’t think I should ever do such a thing as he has, but what did he say? He came over with his father. Well, suppose I went over to France with my father. Of course, it isn’t likely, but one might have done such a thing, and I daresay they have got a New Forest in France. To be sure they have, and I know its name—Fountainebleau. Only fancy if I were being hunted through that place by soldiers. Ugh! If there was a young fellow there found me—a young fellow just about my age—and did not help me, he’d be a brute.”

In his excitement the boy went on marching up and down the quaint, old panelled dining-room, with his fists clenched and his eyes staring, as he recalled the scene in the woods that morning.

Just as he was opposite the door it was thrown open quickly by Bella, who entered with the tea-tray, and who stopped short, startled by the boy’s fierce looks, while as he turned sharply round to march to the other end of the room, Bella hurriedly placed the tea-tray upon the table, and then hastened back to go and tell Martha the cook that she believed Master Waller was going mad.

Chapter Six.

A Good Appetite.

“Yes, I’ll mad him,” retorted the cook, “if he comes meddling with my larder when my back’s turned. I have a very great mind not to finish cooking those sausage-meat cakes for his tea—behaving like that when the Squire’s out!”

But all the same Martha Gusset, who was a pleasant, portly dame, went back to her fire to continue her hurried cooking for her young master’s evening meal.

Meanwhile, without a thought of eating or drinking, Waller was still marching up and down the dining-room making up his mind what he should do; and, this made up, he waited impatiently for the maid’s return to finish her preparations, which were concluded by her bearing in a covered dish which evidently contained something hot and steaming, the vapour which escaped from beneath the cover having a very pleasant, savoury odour.

“There, Master Waller,” said the girl good-humouredly. “Now, do make a good tea, there’s a good boy, and you know what cook is; she don’t like to be put out. I know what I should do if I was you.”

“What?” said Waller, rather surlily.

“Go into the kitchen as soon as you have done tea, and tell her that you never had anything nicer than those cakes; and she will be so pleased that she won’t say another word about the pie.”

“Oh, very well,” said Waller, who was making another plan.

“That’s a good boy. Between you and me. Master Waller, Martha’s as nice as nice, but she’s just as proud and stuck up about her cooking as her brother is about being constable. Ring when you have done, please.”

Waller nodded, and lifted up the dish-cover, which the girl took from his hand, and then, nodding pleasantly, hurried out of the room.

The boy’s actions the next minute were rather curious, for he followed to the door, turned the little handle that shot the small bolt into its socket, and then, after a conspirator-like glance at both the windows, he went to the bookcase and took down six or eight books from the lower shelf, to place them on a chair, before he hurried back to the table, caught up a nice hot plate and a fork, and then transferred half a dozen out of the eight nicely browned meat buns from the dish, carried the plate to the opening in the bookshelf, and pushed it as far back as it would go.

Returning to the table, he paid his next attentions to a little pile of hot and buttered bread cakes, a kind of food in which Martha excelled. Taking up a couple of these, one in each hand, he was moving once more towards the bookcase, but turned back directly.

“Sure to be dusty in there,” he muttered; and, turning back to the table, he deposited the cakes in a plate, which the next minute was standing beside its fellow in the back of the bookcase.

The boy’s next act was to replace the books; but there was not room for them and the plates, and the consequence was that they projected about a couple of inches from the edge of the shelf, while when he tried to shut the glass bookcase door, it too, stood a little way out.

“Don’t suppose she will see,” he muttered, and, satisfied now with what he had done, he went and unbolted the dining-room door, and, feeling very guilty, took his place at the table, poured out his tea, was very liberal with the sugar and milk, and then helped himself to one of the two sausage cakes left and a slice of hot bread.

He had got about half-way through Martha’s appetising cake and had taken three good half-moon bites out of a slice of hot bread, thinking deeply the while, and munching mechanically with his mouth full, but quite unconscious of the flavour of that which he ate, when the door was thrown open and Bella entered, making the boy jump and feel more guilty than ever.

“It’s only me, Master Waller. I have just come to see how you are getting on,” continued the girl, as she advanced towards the table, scanning everything that it held, “and whether I can—oh, my!” she burst out, snatching up her apron and holding it to her mouth to try and stifle back an immoderate burst of laughter.

The next moment she had rushed out of the room, this time allowing the door to bang behind her, while Waller jumped up, staring hard at the partly closed bookcase door as if to read there the cause of the girl’s quick exit.

“She must have been watching at the keyhole,” he muttered to himself, for a guilty conscience needs no accuser, “and she’s gone to tell cook.”

But it was something quite different that Bella was telling her fellow-servant, after throwing herself down in one of the kitchen chairs and laughing hysterically till she cried and choked.

“Oh, don’t be such a stupid,” grunted plump Martha, standing over her and thumping her back. “What is it you have seen? Don’t keep it all to yourself. What are you laughing at? You will have a fit directly.”

“Oh! oh! oh–h–oh!” sobbed Bella. “Do leave off, cook. You hurt.”

“Then tell me what you are laughing at.”

“He’s—he’s—he’s—oh, dear!—oh, dear! I never saw such a sight in my life! I hadn’t been gone more than five minutes when—ho! ho! ho! ho!”

“Look here,” cried cook, who was enjoying her fellow-servant’s mirth, and who began thumping again at poor Bella’s back, “do you want me to thump it out of you?”

“Oh, no, no, no, no, no! Do a-done, cook!” sobbed out Bella, hysterically and incoherently. “Not more than five minutes, and his mouth so full he couldn’t speak, and his eyes staring at me out of his head, and he had gobbled up nearly all the sausage cakes and all the hot bread, and I don’t know how many cups of tea he had had, but the one before him was quite full. But oh, Martha, do a-done, and let me laugh it out, or I shall die!”

Plump Martha’s face was wreathed with smiles, and she chuckled a little audibly at her fellow-servant’s mirth, while her pleasant little vanity was agreeably tickled at the appreciation of her culinary efforts all the while.

“You are such a stupid, Bella,” she said, good-humouredly. “When once you begin to laugh you never know how to leave off. I don’t see anything to laugh at. Poor dear boy, he’d had no dinner, and only a morsel of cold pork-pie since breakfast, and he does like my cakes.”

Chapter Seven.

Secret Preparations.

Waller’s appetite was gone. The girl seemed to have taken it out of the room with her, and the boy thrust his hands into his pockets and sat thinking for some time about his plans, and ended by rising from his hardly touched meal to cross to the bell. But a fresh idea occurred to him, and, going back to the table, he took his untouched cup, carried it carefully to the open window, and emptied it upon a flower-bed; then, returning the cup, he rang the bell, waited till he heard Bella’s step in the hall, and then began to parade in a sort of “sentry go” up and down in front of the partly open bookcase, while the maid, after a glance at the boy’s averted countenance and frowning face, not daring to catch his eye for fear of bursting out into a fresh fit of laughter, began to clear the table.

Neither spoke till the task was pretty well finished, and then the girl looked up at Waller, next at the table, and lastly about the room.

“Well,” she exclaimed, “if I couldn’t declare that I brought two more plates!”

Waller paid no apparent heed to the remark, but continued his “sentry go,” breathing rather hard the while, till Bella left the room, when he uttered a low sigh of relief.

But the boy’s thoughts had not been idle during this time, and as soon as he was free to carry out his plans he opened the door, listened to the murmur of voices in the kitchen, and then ran to the bookcase, took out his supply of provender, had another listen, and then ran with the two plates upstairs, past the main set of bedrooms, and then up the next flight to a room in the front which was devoted to his pursuits.

Here he had books, tools, stuffed birds, fishing-tackle, a wonderfully untidy lot of specimen birds’ nests and their eggs arranged on shelves; in short, in addition to a pallet bedstead and bed that were very rarely used, a most glorious muddle of the odds and ends and collections dear to the heart of a country lad, all of which were under an interdict not to be touched by the brush, broom, or duster of the maids.

Waller’s actions gave the key to his thoughts.

The cereal and carnal cakes were thrust into a closet, and the boy proceeded then to turn down and feel the bed, over which he frowned and seemed in doubt; but the next minute he had rushed out of the room and downstairs to his own chamber, to strip a couple of blankets from the bed, smooth it over again, and make it rougher than it was before, a fact which he grasped and puzzled over for a moment, before exclaiming, “Bother!” and, after listening at the head of the stairs, he rushed up into his work-room with the blankets.

That seemed to him to be all that he could do, till it occurred to him that the room felt hot and stuffy, so he threw open the window, fastening back the casement, and stood gazing out at a great rugged old Scotch fir not many feet away, one apparently of great age, and which cut off a part of the view over the undulating greenery of the forest.

Quite satisfied now, and with a sigh of relief, the boy went out to the landing, carefully locked the door and pocketed the key.

“Let ’em think,” he muttered with a grim smile upon his lips, “it’s a curiosity I found in the woods.”

By this time he was down in the gallery and passing his own chamber, where he stopped short, bringing himself up with the ejaculation—

“Oh! Bella will be at me about the blankets! Bother! What shall I say? Tell her to mind her own business,” he cried half-savagely; and as if to get away from his thoughts he ran down into the hall, snatched his cap from the stand, and then hurried away for the woods.

But it was not in his ordinary free and careless fashion, for his thoughts haunted him, and every now and then he kept turning round as if fancying that he was followed. Now his eyes were directed back at the old ivy-covered house, where he expected to see the maid watching him from one of the windows. Soon after, when the Manor was hidden by the clustering oaks that were scattered park-like among the fields, he was looking over his left shoulder to see if that was the fat village constable in the distance bending down so as to creep along unobserved, and not one of his father’s mouse-coloured cows.

Hurrying on, and right into the forest, his next fancy was that he heard a distant shout, one that was answered, though it might have been an echo, and his heart beat a little faster as he set both sounds down to soldiers searching among the trees and hallooing to one another so as to keep in touch.

“Oh, I say,” he muttered to himself, as he proceeded, keeping to the densest portions of the forest, and doubling the labour in threading his way, “who could have thought that it would make one feel so queer? I haven’t done anything—at least, nothing much—to mind, and here am I feeling as if I had been guilty of nobody knows what. No wonder that poor chap felt so bad and pulled out the pistol. What did he say his name was? Boyne? Let’s see—Battle of the Boyne—where was that? Oh, I know—King James, and he was a Stuart. Nonsense! That couldn’t have had anything to do with his name. Let’s see; I had better wait till it gets dusk, and then—oh, I’ll risk it. I’ll smuggle him up to the house and upstairs. But what about Joe Hanson? Mustn’t run against him. He’s always pottering about outside the house towards evening, just as if he thought I wanted to go down the garden and help myself to apples and pears. Like his impudence, with his ‘my garden’ and ‘my fruit,’ and all the rest of it; and father said that I was to take what I liked, and that he should be proud to leave it to my discretion. It will come to a row one of these days, for I shall hit out at Master Joe, and then he will go and complain. Bother Joe Hanson! I want to think about that poor chap lying out there amongst the bracken. What a miserable, haggard scarecrow he did look, just like some poor beggarly tramp. But one could feel that he was a gentleman as soon as he began to speak. There; best way will be to take him boldly up to the front door and right up the stairs, and chance it. One never tries to play the sneak and get anywhere unseen without running bang up against somebody.”

These and similar thoughts so took up the boy’s attention that it was like a surprise to him when, close upon sunset, and when the shadows were deepening in the forest, he found himself close to the spot where he had left the fugitive; and there he stopped short, listening and then, feeling that he must not seem to be peering about, he took out his knife, cut down a nice straight rod of hazel, and began to whittle and trim it, apparently intent upon his task, but with his ears twitching and his lowered eyes peering to right and left in every direction, as he seemed to be unconsciously changing his position.

“Wish I were as clever as Bunny Wrigg,” he muttered. “He’s just like a fox for hiding, throwing anyone off the scent. He’d have got here without anybody seeing him, while, for aught I know, I may have been watched all the time—by soldiers, perhaps. That must have been some of them I heard shouting. Oh, it is so queer,” he muttered passionately, as he hacked off the twigs of the stout sapling. “Only this morning I was as happy as I could be, and now my head’s all of a buzz with worry. Wish I’d gone and found Bunny Wrigg and told him all; he’d have helped me and enjoyed the job. I don’t know, though. There’s that hundred pounds reward. I am glad, after all, I didn’t trust him. This is one of the things like father talked to me about where one has no business to trust anybody but oneself. Here, I mustn’t go straight up to the hiding-place, in case I am watched. Oh, how suspicious I do feel!”

Turning short round, he began to retrace his steps, acting as if he had fulfilled his purpose and come expressly for that hazel-rod, which he went on trimming, humming a tune the while, which unconsciously merged into one of the Scottish ditties about “Charley over the water.”

He sauntered on for some distance, till, coming to what he considered a suitable spot, he glanced furtively to right and left without turning his head, and then, having pretty well trimmed his rod, he began to treat it as if it were a javelin, darting it right away before him, and running after it to catch it up and aim it with a good throw at a tree some yards away. He went through this performance four or five times over before aiming for a dense clump of the abundant bracken, into the midst of which he darted his mock spear, dashed in after it, and did not appear again, for the hazel-rod was left where it fell, and the boy was crawling rapidly on hands and knees beneath the great bracken fronds, keeping well out of sight till, judging by the towering beeches which he took for his bearings, he stopped at last, hot and panting with his exertions, close to where he had left the young spy.

Chapter Eight.

Helping the Fugitive.

Waller had managed so well that he had only a few yards to go; in fact, if the task had been undertaken by the tall gipsy-like woodland dweller, to whom he had referred as Bunny—a nickname, by the way, bestowed upon him by the boy from his rabbit-like habits, though they were more foxy, as Waller felt, but he liked him too well to brand him with such a name—it could not have been done better.

The next minute, with a vivid recollection of the pistol which had been thrust into the fugitive’s breast, the boy was creeping forward and listening, till, as he came nearer, he became aware of a deep stertorous breathing, almost a snore, and, closing up, he bent over, to lay one hand on the hidden pistol, so as to be well on his defence, while with the other he gently shook the deep sleeper.

Waller expected that the poor fellow would start up in wild affright, but his touch only resulted in a dull, incoherent muttering, and the shake had to be repeated two or three times before the fugitive slowly sat up and gazed at him vacantly, laying one hand upon his burning forehead the while.

“Yes,” he said slowly, “What is it?”

“I have come back,” said Waller. “Don’t you know me? Why, you are not half awake yet. It will be dark soon, quite dark by the time we get home, and I am going to take you there.”

The poor fellow passed his hand two or three times across his forehead, as if to clear away some mist that hindered his perceptions.

“I say, you have had a splendid sleep,” continued Waller. “Feel better now?”

“Sleep? Better? I don’t know—don’t know. Yes, I do. You came and brought me something to eat, and I have been to sleep and dreaming about—Oh!” he groaned, and, leaning forward and covering his face with his hands, he began to rock himself to and fro as if the mental agony from which he suffered was too hard to bear.

Waller looked on in silence for a few moments, before reaching forward and laying his hand upon the poor fellow’s shoulder, when the touch acted like magic. His hands were caught in those of the fugitive, who rose painfully to his feet and spoke in a low, quick, hurried way.

“Yes,” he said, “I am ready. Take me where you said; but,” he added, glancing sharply round with a wild and fevered look in his eyes, “did the soldiers come, or did I dream it?”

“Dreamt it,” said Waller emphatically.

“Ah!” was sighed. “Am I speaking properly? I—I don’t quite know what I say. It’s my head, I suppose—my head.”

“You are not quite awake,” said Waller encouragingly. “There, come down to the river and bathe your face. It’s getting beautifully cool now; and then we will go gently home through the woods.”

The poor fellow nodded quickly, obeying his companion to the letter, and seeming to trust himself entirely in his hands.

He seemed a little clearer after lying down and bathing his face; but as they walked slowly towards the Manor there were moments when he began to turn dizzy and reeled. But they reached the old Elizabethan house at last, quite in the dusk of evening, and, following out his settled plans, Waller led his companion in through the porch, across the hall, and upstairs, quite unseen, and rather breathless himself, while his companion seemed to have grown calmer. He unlocked the door of his den, threw it open, and closed it upon them with a sigh of relief, as he said,—

“There, sit down in that old chair—gently, for the bottom’s broken. This is my own room.” Then, as the poor fellow sank back heavily in the very ancient chair, one that Waller had rescued from the lumber-room for his own particular use, he said, “I say: I won’t be above a minute. Don’t you stir. I am going downstairs to get a light.”

There was no reply, and, hurriedly descending, Waller fetched candle and stick, to return and find the “something” that he had brought in from the forest fast asleep once more.

“Now we shall be all right,” he said. “I have got some supper for you. What, asleep again?” he continued, more gently. “Well, you had better lie down. Here, I say, have a nap on the bed. Get up, and I’ll help you. You had better undress.”

The poor fellow grasped a portion of his wishes, and rose mechanically, reeled to the bed, and fell across it with his legs trailing upon the floor; but a few minutes after, with his young host’s help, he was properly installed outside, dressed as he was, to sink at once into a deep, feverish sleep.

There was no suppering that night for the stranger, who slept on, muttering quickly at intervals, and was still sleeping when Waller stole up to his side again and again at intervals during what seemed to be an interminably long night; for though he pretended to go to bed, the boy could not sleep for more than an hour at a time, and when he did it was only to start up from some troubled dream connected with the incidents of the past day, for he was suffering badly from a new complaint—fugitive on the brain.

Chapter Nine.

In Hiding.

“What’s he doing now?” said Martha. “Isn’t going to be ill, is he?”

“Ill?” said Bella, contemptuously. “Not he!”

“But he’s shut up in that attic, isn’t he?”

“Yes, I told you so. Got another of those whim-whams in his head, and making a litter of some kind—skinning snakes or something that he’s caught in the woods.”

“Ugh!” ejaculated cook. “If there’s anything I can’t abear it’s them nasty scrawmy things. Did you tell him his dinner was ready?”

“Yes, and he nearly snapped my head off.”

“What does he want to be skinning snakes for?” said the cook.

“Oh, I don’t know—horrid things! He’s got about half a dozen up there as he did last year; peels all the skins off, same as you do with the eels, and then turns them inside out again, fills them full of sand, and then twists them up and leaves them to dry.”

“And what then?” said cook.

“Pours all the sand out again.”

“But, I say, has he got them up there alive before he skins them?”

“I don’t know as he has got any at all,” said Bella shortly.

“Then why did you say he had?”

“I didn’t. I only said I supposed he had, because he’s always skinning something or another. He’s got owls, and stoats, and all sorts of things that he gets in the forest, or that nasty fellow Bunny Wrigg brings for him.”

“Oh!” said the cook. “Because I am not going to sleep upstairs if he’s got live snakes to come crawling out of his room at all times in the night.”

But though guilty of many such acts as the maid charged him with, Waller was not engaged with any taxidermic preparations, for his time during the past two days had been taken up in attendance upon the young fugitive.

For the first day the latter ate nothing, but passed the full twenty-four hours in a feverish sleep. Then he seemed to throw off the fever, and, thanks to his host, who was eager to supply him, gradually transformed himself from the miserable, ragged, famished object into such a specimen of humanity as made Waller smile with satisfaction.

“Why,” he said, “if the soldiers did come they wouldn’t know you again.”

“Again?” replied the lad. “They’ve never seen me.”

“Well, I mean they wouldn’t take you for a—for a—”

“There, say it,” cried the lad sadly, “For a spy.”

“I didn’t mean spy,” said Waller. “I meant fugitive.”

“But they would. If I were questioned, what account could I give of myself? I have tried to do the work for which I came—for which we came—and I have failed. I am not going to tell a lie.”

“No, of course not,” said Waller hotly; “but you might hold your tongue, or tell any impudent beggar who dared to ask you questions, to mind his own business, if he didn’t want to be kicked.”

“Should you speak to the soldiers like that?” said Boyne, with a smile.

“Of course,” cried Waller. “What do I care for the soldiers?”

“Ah!” sighed the lad. “But never mind that. I am so grateful to you for all you have done.”

“Oh, nonsense!” cried Waller, flushing. “People are always hospitable in the country.”

“So I have heard,” said the other; “but, if I had been your own brother you could not have done more for me. You have saved my life.”

“Oh, nonsense! I tell you. You make too much of it. I never had a brother, but fellows whom I have known at Winchester who have—they are not so very fond of doing things for one another. They generally like fighting and knocking one another about. I suppose they oughtn’t to, but they quarrel more with their brothers than they do with anyone else. But you mustn’t touch their brothers, for if you do—oh my! You have them on to you at once. Here, I say, I wish you wouldn’t talk like that.”

“Well, I will not. I don’t want to go away and leave you, but I must. I can think of nothing else.”

“But why?”

“Because I am shut up here alone so much, a prisoner.”

“Yes, but it’s only until it’s safe for you to go away. You must see that you ought to be patient. There, I’ll bring you up books to read, to amuse you.”

“I can’t read them. They wouldn’t amuse me with my mind in this state.”

“Well; then, have a look at some of my things,” cried Waller, pulling out the drawer of a big press. “These are all traps and springs with which I catch birds and animals in the forest. Bunny Wrigg taught me how to make them and how to use them. I wish you knew him. He’s a capital fellow, and knows the forest ten times better than I do.”

“Oh, I don’t want to know the forest—nor, your friend,” said the lad wearily. “I want to be free to come and go—as free as the birds and those little animals, the squirrels, that I see out of the window.”

“Yes, of course you do, and so you shall be soon,” cried Waller. “But you haven’t quite recovered yet from that feverishness and all you went through. I say, have a look in this drawer.”

Waller thrust the open one in and pulled out another. “Look here, these are my old nets with which we drag the hammer pond, and catch the carp and tench; great golden fellows they are, some of them; but the worst of it is the pond’s so deep that the fish dive under the net and escape.”

“And those which do not,” said the lad sadly, “you take in that net and make prisoners of them. Poor things! And what good are they to you when you have caught them?”

“Good? Good to eat! I say, what a fellow you are to talk of the fish one catches as prisoners! Carp and tench are not human beings.”

“No, they are not human beings,” said the lad, smiling sadly; “but they are prisoners, the same as I am.”

“Oh, I say, what stuff! To call yourself a prisoner, when you are only a visitor here, and could come and go just as you like—at least, not quite, for it wouldn’t be safe; but it will be soon.”

“What’s that coil of new rope for?”

“That?” cried Waller. “Oh, that’s a new rope for my drag-net. The old one was quite worn out. You shall help me to fit this on if you like.”

“Thank you. I’ll help you if you wish.”

“Well, I do wish, when you get well; but I don’t care to see you in the dumps like this. Of course I know what it is: it’s being shut up in this room for so long. A few good walks in the forest would make you as right as could be.”

“Yes,” said the lad wearily. “I feel as if I should like to be out again, for I often think when I am shut up here that it’s like being a bird in a cage.”

“Ah, you won’t feel that long,” said Waller.

It was the very next day when, after taking his new friend a selection of what he considered interesting books, Waller announced that he should not come upstairs again till the evening, for he had several things to do, and among others to write a letter to his father in London, and then take it to the village post-office for despatch.

“I don’t think that either of the maids is likely to come up,” said Waller, at parting; “but if they should try the door, all you have got to do is to keep quite still. Of course, you will lock yourself in as soon as I am gone. Shall I bring you anything else to eat before I go?”

“No,” said the lad, with a weary look of disgust. “You bring me too much as it is; more than I care to have. Don’t bring me any more till I ask.”

“I shall,” said Waller, with a laugh. “I am not going to have you starve yourself to death up in my room. There, jump up and come and shut the door, and then have a good long read. I’ll get back to you as soon as I can, and then we will have a good game at draughts or chess. But I mustn’t be up here too much, or it will make the girls suspicious. There, good-bye for the present.”

Waller went down and busied himself at once over the letter to his father, telling him of some of the things that were going on, but carefully—though strongly tempted—omitting all allusion to the fugitive.

It was rather a slow and laborious task for the boy, clever as he was at most things, though none too able in the use of a quill pen. But he got his letter finished at last, the big post-paper carefully folded and sealed, and then went off to the post-bag at the little village shop, before hurrying back home to partake of his tea, which was waiting.

It was a lonely meal, and the boy sighed as he stirred the sugar, and wished he could have Godfrey Boyne down, as companion for himself, and to cheer the poor fellow up.

It was quite dark by the time he had done, and with the full intention of suggesting that they should wait till the girls had gone to bed, and then steal down together for a walk in the forest, the boy rose to go and make an observation or two as to the position of the servants, before stealing up to join his friend.

Waller rose, went across to the bell, the pull of which he had taken in his hand, when he was startled by a distant scream, followed by half a dozen more, and the trampling of feet somewhere above, while, as he rushed out into the hall, he was just in time to hear a door bang and quick steps hurrying along the kitchen passage.

Chapter Ten.

Alarming Sounds.

The thoughts of Godfrey Boyne occupied so much position in Waller’s brain that he at once concluded something must be wrong with him, and rushing upstairs two at a time, and making sure that he was not followed, he continued the rest of his way in the darkness as silently as he could, pausing to listen at the top of the attic stairs, and then cautiously creeping to and trying the door of his den.

All was perfectly still there, and he found the door fastened from within.

“False alarm,” he said to himself; and he crept down again to make his way to the kitchen, from which, as he drew nearer, there came faint hysterical cries and a most unpleasant smell of burning.

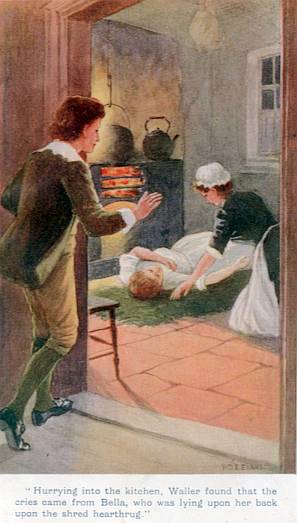

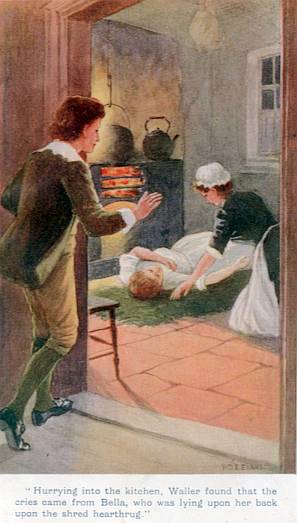

Hurrying into the kitchen, Waller found that the cries came from Bella, who was lying upon her back upon the shred hearthrug in front of the kitchen fire, while Martha was trying to bring her fellow-servant round from a fainting fit, and causing the horrible stench by burning the dried wing of a goose close to the girl’s nostrils and making her sneeze violently.

“Oh dear! Oh dear!” cried Bella, uttering a sob, and then giving vent to a tremendous sneeze.

“Bless the King!” said Martha Gusset quietly. “Sneeze again, dear; it’ll do you no end of good.”

The advice came rather late, for the girl’s face was already wrinkling up for another nervous convulsion that seemed stronger than the last.

“Bless the King!” said the cook again, “There, there, dear: you will be better soon.”

“What’s the matter, Martha?” said Waller anxiously, and with a horrible dread upon him that all had been found out.

“She’s had a fright, my dear. I don’t quite know yet what it all means. She thinks she’s seen something, but I daresay it’s only one of them owls.”

“Oh, no, no, no, no!” sobbed Bella, “it was something dreadful—something dreadful!”

“Well, well, then, my dear, tell us what it is,” said Martha, in her most motherly way, “and it will do you good.”

“Oh, it was dreadful!” moaned Bella. “I remembered that I had forgotten to shut the window in master’s chamber, which I opened this afternoon to let the sun in and get the room aired, and without stopping to fetch a light I went up in the dark, and then—and then—Oh dear! Oh dear! Oh dear! Oh dear!”

“Take another sniff of the feathers, my dear, and have a good sneeze, and that will relieve you.”

“Oh, do a-done, cook, and throw the nasty thing behind the fire. I was just coming out again into the gallery, when I heard something horrid.”

“Heard?” cried Waller excitedly. “Then you didn’t see it?”

“No, Master Waller. I only heard it walking. Somewhere up by your room—I mean your den, as you call it. And then all in the dark there come bumpity bump all down the stairs, and I shruck and shruck again, and ran for my life.”

“My!” said cook. “Was it as bad as that? But what was it, my dear?”

“Oh, I don’t know, cook. Something dreadfully horrid, and it was dragging a dead body all down the stairs, and knocking the back of the head hard on every step.”

“Fancy!” said Martha, with an emphatic sniff. “It’s all stuff, and nonsense. No such thing could have happened. It was all because you went up in the dark.”

From feeling startled, and in dread of his secret being known, a rapid change came over Waller; half-suspecting what must have occurred, and finding it covered by the girl’s superstitious notions, added to which there were the feathers, the sneezes, and the cook’s blessings upon his Majesty King George the Third, the boy’s risible faculties were so bestirred that he burst into a roar of laughter.