The Project Gutenberg EBook of Michael Penguyne, by William H. G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Michael Penguyne

Fisher Life on the Cornish Coast

Author: William H. G. Kingston

Release Date: October 25, 2007 [EBook #23188]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MICHAEL PENGUYNE ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

William H G Kingston

"Michael Penguyne"

Chapter One.

As the sun rose over the Lizard, the southernmost point of old England, his rays fell on the tanned sails of a fleet of boats bounding lightly across the heaving waves before a fresh westerly breeze. The distant shore, presenting a line of tall cliffs, towards which the boats were steering, still lay in the deepest shade.

Each boat was laden with a large heap of nets and several baskets filled with brightly-shining fish.

In the stern of one, tiller in hand, sat a strongly-built man, whose deeply-furrowed countenance and grizzled hair showed that he had been for many a year a toiler on the ocean. By his side was a boy of about twelve years of age, dressed in flushing coat and sou’wester, busily employed with a marline-spike, in splicing an eye to a rope’s-end.

The elder fisherman, now looking up at his sails, now stooping down to get a glance beneath them at the shore, and then turning his head towards the south-west, where heavy clouds were gathering fast, meanwhile cast an approving look at the boy.

“Ye are turning in that eye smartly and well, Michael,” he said. “Whatever you do, try and do it in that fashion. It has been my wish to teach you what is right as well as I know it. Try not only to please man, my boy, but to love and serve God, whose eye is always on you. Don’t forget the golden rule either: ‘Do to others as you would they should do to you.’”

“I have always wished to understand what you have told me, and tried to obey you, father,” said the boy.

“You have been a good lad, Michael, and have more than repaid me for any trouble you may have caused me. You are getting a big boy now, though, and it’s time that you should know certain matters about yourself which no one else is so well able to tell you as I am.”

The boy looked up from his work, wondering what Paul Trefusis was going to say.

“You know, lad, that you are called Michael Penguyne, and that my name is Paul Trefusis. Has it never crossed your mind that though I have always treated you as a son—and you have ever behaved towards me as a good and dutiful son should behave—that you were not really my own child?”

“To say the truth, I have never thought about it, father,” answered the boy, looking up frankly in the old man’s face. “I am oftener called Trefusis than Penguyne, so I fancied that Penguyne was another name tacked on to Michael, and that Trefusis was just as much my name as yours. And oh! father, I would rather be your child than the son of anybody else.”

“There is no harm in wishing that, Michael; but it’s as well that you should know the real state of the case, and as I cannot say what may happen to me, I do not wish to put off telling you any longer. I am not as strong and young as I once was, and maybe God will think fit to take me away before I have reached the threescore years and ten which He allows some to live. We should not put off doing to another time what can be done now, and so you see I wish to say what has been on my mind to tell you for many a day past, though I have not liked to say it, lest it should in any way grieve you. You promise me, Michael, you won’t let it do that? You know how much I and granny and Nelly love you, and will go on loving you as much as ever.”

“I know you do, father, and so do granny and Nelly; I am sure they love me,” said the boy gazing earnestly into Paul’s face, with wonder and a shade of sorrow depicted on his own countenance.

“That’s true,” said Paul. “But about what I was going to say to you.

“My wife, who is gone to heaven, Nelly’s mother, and I, never had another child but her. Your father, Michael, as true-hearted a seaman as ever stepped, had been my friend and shipmate for many a long year. We were bred together, and had belonged to the same boat fishing off this coast till we were grown men, when at last we took it into our heads to wish to visit foreign climes, and so we went to sea together. After knocking about for some years, and going to all parts of the world, we returned home, and both fell in love, and married. Your mother was an orphan, without kith or kin, that your father could hear of—a good, pretty girl she was, and worthy of him.

“We made up our minds that we would stay on shore and follow our old calling and look after our wives and families. We had saved some money, but it did not go as far as we thought it would, and we agreed that if we could make just one more trip to sea, we should gain enough for what we wanted.

“You were about two years old, and my Nelly was just born.

“We went to Falmouth, where ships often put in, wanting hands, and masters are ready to pay good wages to obtain them. We hadn’t been there a day, when we engaged on board a ship bound out to the West Indies. As she was not likely to be long absent, this just suited us. Your father got a berth as third mate, for he was the best scholar, and I shipped as boatswain.

“We made the voyage out, and had just reached the chops of the Channel, coming back, bound for Bristol, and hoping in a few days to be home again with our wives, when thick weather came on, and a heavy gale of wind sprang up. It blew harder and harder. Whether or not the captain was out of his reckoning I cannot say, but I suspect he was. Before long, our sails were blown away, and our foremast went by the board. We did our best to keep the ship off the shore, for all know well that it is about as dangerous a one as is to be found round England.

“The night was dark as pitch, the gale still increasing.

“‘Paul,’ said your father to me as we were standing together, ‘you and I may never see another sun rise; but still one of us may escape. You remember the promise we made each other.’

“‘Yes, Michael,’ I said, ‘that I do, and hope to keep it.’

“The promise was that if one should be lost and the other saved, he who escaped should look after the wife and family of the one who was lost.

“I had scarcely answered him when the look-out forward shouted ‘Breakers ahead!’ and before the ship’s course could be altered, down she came, crashing on the rocks. It was all up with the craft; the seas came dashing over her, and many of those on deck were washed away. The unfortunate passengers rushed up from below, and in an instant were swept overboard.

“The captain ordered the remaining masts to be cut away, to ease the ship; but it did no good, and just as the last fell she broke in two, and all on board were cast into the water, I found myself  clinging with your father to one of the masts. The head of the mast was resting on a rock. We made our way along it; I believed that others were following; but just as we reached the rock the mast was carried away, and he and I found that we alone had escaped.

clinging with your father to one of the masts. The head of the mast was resting on a rock. We made our way along it; I believed that others were following; but just as we reached the rock the mast was carried away, and he and I found that we alone had escaped.

“The seas rose up foaming around us, and every moment we expected to be washed away. Though we knew many were perishing close around us we had no means of helping them. All we could do was to cling on and try and save our own lives.

“‘I hope we shall get back home yet, Michael,’ I said, wishing to cheer your father, for he was more down-hearted than usual.

“‘I hope so, Paul, but I don’t know; God’s will be done, whatever that will is. Paul, you will meet me in heaven, I hope,’ he answered, for he was a Christian man. ‘If I am taken, you will look after Mary and my boy,’ he added. Again I promised him, and I knew to a certainty that he would look after my Nelly, should he be saved and I drowned.

“When the morning came at last scarcely a timber or plank of the wreck was to be seen. What hope of escape had either of us? The foaming waters raged around, and we were half perished with cold and hunger. On looking about I found a small spar washed up on the rock, and, fastening our handkerchiefs together, we rigged out a flag, but there was little chance of a boat putting off in such weather and coming near enough to see it. We now knew that we were not far off the Land’s End, on one of two rocks called The Sisters, with the village of Senum abreast of us.

“Your father and I looked in each other’s faces; we felt that there was little hope that we should ever see our wives and infants again. Still we spoke of the promise we had made each other—not that there was any need of that, for we neither of us were likely to forget it.

“The spring tides were coming on, and though we had escaped as yet, the sea might before long break over the rock and carry us away. Even if it did not we must die of hunger and thirst, should no craft come to our rescue.

“We kept our eyes fixed on the distant shore; they ached with the strain we put on them, as we tried to make out whether any boat was being launched to come off to us.

“A whole day passed—another night came on. We did not expect to see the sun rise again. Already the seas as they struck the rock sent the foam flying over us, and again and again washed up close to where we were sitting.

“Notwithstanding our fears, daylight once more broke upon us, but what with cold and hunger we were well-nigh dead.

“Your father was a stronger man than I fancied myself, and yet he now seemed most broken down. He could scarcely stand to wave our flag.

“The day wore on, the wind veered a few points to the nor’ard, and the sun burst out now and then from among the clouds, and, just as we were giving up all hope, his light fell on the sails of a boat which had just before put off from the shore. She breasted the waves bravely. Was she, though, coming towards us? We could not have been seen so far off. Still on she came, the wind allowing her to be close-hauled to steer towards the rock. The tide meantime was rapidly rising. If she did not reach us soon, we knew too well that the sea would come foaming over the rock and carry us away.

“I stood up and waved our flag. Still the boat stood on; the spray was beating in heavy showers over her, and it was as much as she could do to look up to her canvas. Sometimes as I watched her I feared that the brave fellows who were coming to our rescue would share the fate which was likely to befall us. She neared the rock. I tried to cheer up your father.

“‘In five minutes we shall be safe on board, Michael,’ I said.

“‘Much may happen in five minutes, Paul; but you will not forget my Mary and little boy,’ he answered.

“‘No fear of that,’ I said; ‘but you will be at home to look after them yourself.’

“I tried to cheer as the boat came close to the rock, but my voice failed me.

“The sails were lowered and she pulled in. A rope was hove, and I caught it. I was about to make it fast round your father.

“‘You go first, Paul,’ he said. ‘If you reach the boat I will try to follow, but there is no use for me to try now; I should be drowned before I got half way.’

“Still I tried to secure the rope round him, but he resisted all my efforts. At last I saw that I must go, or we should both be lost, and I hoped to get the boat in nearer and to return with a second rope to help him.

“I made the rope fast round my waist and plunged in. I had hard work to reach the boat; I did not know how weak I was. At last I was hauled on board, and was singing out for a rope, when the people in the boat uttered a cry, and looking up I saw a huge sea come rolling along. Over the rock it swept, taking off your poor father. I leapt overboard with the rope still round my waist, in the hopes of catching him, but in a moment he was hidden from my sight, and, more dead than alive, I was again hauled on board.

“The crew of the boat pulled away from the rock; they knew that all hopes of saving my friend were gone. Sail was made, and we stood for the shore.

“The people at the village attended me kindly, but many days passed before I was able to move.

“As soon as I had got strength enough, with a sad heart I set out homewards. How could I face your poor mother, and tell her that her husband was gone? I would send my own dear wife, I thought, to break the news to her.

“As I reached my own door I heard a child’s cry; it was that of my little Nelly, and granny’s voice trying to soothe her.

“I peeped in at the window. There sat granny, with the child on her knee, but my wife was not there. She has gone to market, I thought. Still my heart sank within me. I gained courage to go in.

“‘Where is Nelly?’ I asked, as granny, with the baby in her arms, rose to meet me.

“‘Here is the only Nelly you have got, my poor Paul,’ she said, giving me the child.

“I felt as if my heart would break. I could not bring myself to ask how or when my wife had died. Granny told me, however, for she knew it must be told, and the sooner it was over the better. She had been taken with a fever soon after I had left home.

“It was long before I recovered myself.

“‘I must go and tell the sad news I bring to poor Mary,’ I said.

“Granny shook her head.

“‘She is very bad, it will go well-nigh to kill her outright,’ she observed.

“I would have got granny to go, but I wanted to tell your poor mother of my promise to your father, and, though it made my heartache, I determined to go myself.

“I found her, with you by her side.

“‘Here is father,’ you cried out, but your mother looked up, and seemed to know in a moment what had happened.

“‘Where is Michael?’ she asked.

“‘You know, Mary, your husband and I promised to look after each other’s children, if one was taken and the other left; and I mean to keep my promise to look after you and your little boy.’

“Your mother knew, by what I said, that your father was gone.

“‘God’s will be done,’ she murmured; ‘He knows what is best—I hope soon to be with him.’

“Before the month was out we carried your poor mother to her grave, and I took you to live with granny and Nelly.

“There, Michael, you know all I can tell you about yourself. I have had hard times now and then, but I have done my duty to you; and I say again, Michael, you have always been a good and dutiful boy, and not a fault have I had to find with you.”

“Thank you, father, for saying that; and you will still let me call you father, for I cannot bring myself to believe that I am not really your son.”

“That I will, Michael; a son you have always been to me, and my son I wish you to remain. And, Michael, as I have watched over you, so I want you to watch over my little Nelly. Should I be called away, be a brother and true friend to her, for I know not to what dangers she may be exposed. Granny is old, and her years on earth may be few, and when she is gone, Michael, Nelly will have no one to look to but you. She has no kith nor kin, that I know of, able or willing to take care of her. Her mother’s brother and only sister went to Australia years ago, and no news has ever come of them since, and my brothers found their graves in the deep sea, so that Nelly will be alone in the world. That is the only thing that troubles me, and often makes me feel sad when we are away at night, and the wind blows strong and the sea runs high, and I think of the many I have known who have lost their lives in stouter boats than mine. But God is merciful; He has promised to take care of the widow and orphan, and He will keep His word. I know that, and so I again look up and try to drive all mistrustful thoughts of His goodness from my mind.”

“Father, while I have life I will take care of Nelly, and pray for her, and, if needs be, fight for her,” exclaimed Michael.

He spoke earnestly and with all sincerity, for he intended, God willing, to keep his word.

Chapter Two.

The fleet of fishing-boats as they approached the coast steered in different directions, some keeping towards Kynance and Landewednach, while Paul Trefusis shaped his course for Mullyan Cove, towards the north, passing close round the lofty Gull Rock, which stands in solitary grandeur far away from the shore, braving the fierce waves as they roll in from the broad Atlantic.

Asparagus Island and Lion Rock opened out to view, while the red and green sides of the precipitous serpentine cliffs could now be distinguished, assuming various fantastic shapes: one shaped into a complete arch, another the form of a gigantic steeple, with several caves penetrating deep into the cliff, on a level with the narrow belt of yellow sand.

Young Michael, though accustomed from his childhood to the wild and romantic scenery, had never passed that way without looking at it with an eye of interest, and wondering how those cliffs and rocks came to assume the curious forms they wore.

The little “Wild Duck,” for that was the name Paul Trefusis had given his boat, continued her course, flying before the fast increasing gale close inshore, to avoid the strong tide which swept away to the southward, till, rounding a point, she entered the mouth of a narrow inlet which afforded shelter to a few boats and small craft. It was a wild, almost savage-looking place, though extremely picturesque. On either side were rugged and broken cliffs, in some parts rising sheer out of the water to the gorse-covered downs above, in others broken in terraces and ledges, affording space for a few fishermen’s cottages and huts, which were seen perched here and there, looking down on the tranquil water of the harbour.

The inlet made a sharp bend a short distance from its mouth, so that, as Paul’s boat proceeded upwards, the view of the sea being completely shut out, it bore the appearance of a lake. At the further end a stream of water came rushing down over the summit of the cliffs, dashing from ledge to ledge, now breaking into masses of foam, now descending perpendicularly many feet, now running along a rapid incline, and serving to turn a small flour-mill built a short way up on the side of the cliff above the harbour.

Steep as were the cliffs, a zigzag road had been cut in them, leading from the downs above almost to the mouth of the harbour, where a rock which rose directly out of the water formed a natural quay, on which the fishing-boats could land their cargoes. Beyond this the road was rough and steep, and fitted only for people on foot, or donkeys with their panniers, to go up and down. Art had done little to the place.

The little “Wild Duck,” a few moments before tossed and tumbled by the angry seas, now glided smoothly along for a few hundred yards, when the sails were lowered, and she floated up to a dock between two rocks. Hence, a rough pathway led from one of the cottages perched on the side of the cliff. At a distance it could scarcely have been distinguished from the cliff itself. Its walls were composed of large blocks of unhewn serpentine, masses of clay filling up the interstices, while it was roofed with a thick dark thatch, tightly fastened down with ropes, and still further secured by slabs of stone to prevent its being carried away by the fierce blasts which are wont to sweep up and down the ravine in winter.

There was space enough on either side of the cottage for a small garden, which appeared to be carefully cultivated, and was enclosed by a stone wall. At the upper part of the pathway a flight of steps, roughly hewn in the rock, led to the cottage door.

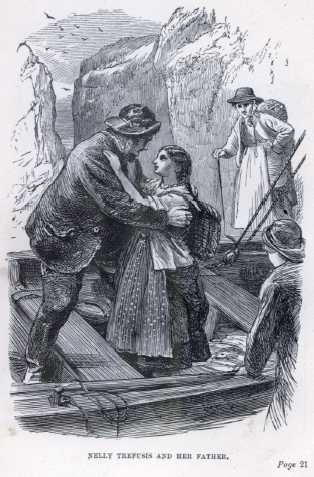

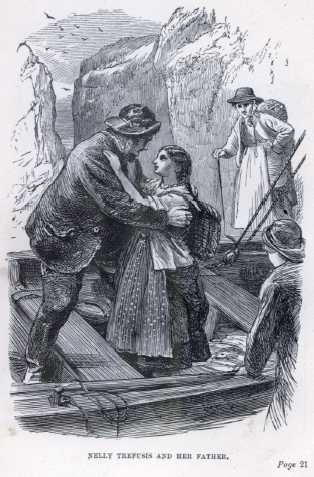

The door opened as soon as Paul’s boat rounded the point, and a young girl with a small creel or fish basket at her back was seen lightly tripping down the pathway, followed by an old woman, who, though she supported her steps with a staff, also carried a creel of the ordinary size. She wore a large broad-brimmed black hat, and a gaily-coloured calico jacket over her winsey skirt; an apron, and shoes with metal buckles, completing the ordinary costume of a fish-wife of that district. Little Nelly was dressed very like her grandmother, except that her feet were bare, and that she had a necklace of small shells round her throat. Her face was pretty and intelligent, her well-browned cheeks glowed with the hue of health, her eyes were large and grey, and her black hair, drawn up off her forehead, hung in neat plaits tied with ribbons behind her back. Nelly Trefusis was indeed a good specimen of a young fisher-girl.

She tripped lightly down the pathway, springing  to the top of the outermost rock just before her father’s boat glided by it, and in an instant stepping nimbly on board, she threw herself into his arms and bestowed a kiss on his weather-beaten brow.

to the top of the outermost rock just before her father’s boat glided by it, and in an instant stepping nimbly on board, she threw herself into his arms and bestowed a kiss on his weather-beaten brow.

Michael had leaped on shore to fend off the boat, so that he lost the greeting she would have given him.

“You have had a good haul with the nets to-night, father,” she said, looking into the baskets; “Granny and I can scarce carry half of them to market, and unless Abel Mawgan the hawker comes in time to buy them, you and Michael will have work to do to salt them down.”

“It is well that we should have had a good haul, Nelly, for dirty weather is coming on, and it may be many a day before we are able to cast our nets again,” answered Paul, looking up affectionately at his child, while he began with a well-practised hand to stow the boat’s sail.

Nelly meantime was filling her creel with fish, that she might lessen the weight of the baskets which her father and Michael had to lift on shore. As soon as it was full she stepped back on the rock, giving a kiss to Michael as she passed him.

The baskets were soon landed, and the creel being filled, she and Nelly ascended the hill, followed by Paul and Michael, who, carrying the baskets between them, brought up the remainder of the fish.

Breakfast, welcome to those who had been toiling all night, had been placed ready on the table, and leaving Paul and his boy to discuss it, Polly Lanreath, as the old dame was generally called, and her little granddaughter, set off on their long journey over the downs to dispose of their fish at Helston, or at the villages and the few gentlemen’s houses they passed on their way. It was a long distance for the old woman and girl to go, but they went willingly whenever fish had been caught, for they depended on its sale for their livelihood, and neither Paul nor Michael could have undertaken the duty, nor would they have sold the fish so well as the dame and Nelly, who were welcomed whenever they appeared. Their customers knew that they could depend on their word when they mentioned the very hour when the fish were landed.

The old dame’s tongue wagged cheerfully as she walked along with Nelly by her side, and she often beguiled the way with tales and anecdotes of bygone days, and ancient Cornish legends which few but herself remembered. Nelly listened with eager ears, and stored away in her memory all she heard, and often when they got back in the evening she would beg her granny to recount again for the benefit of her father and Michael the stories she had told in the morning.

She had a cheerful greeting, too, for all she met; for some she had a quiet joke; for the giddy and careless a word of warning, which came with good effect from one whom all respected. At the cottages of the poor she was always a welcome visitor, while at the houses of the more wealthy she was treated with courtesy and kindness; and many a housewife who might have been doubtful about buying fish that day, when the dame and her granddaughter arrived, made up her mind to assist in lightening Nelly’s creel by selecting some of its contents.

The dame, as her own load decreased, would always insist on taking some of her granddaughter’s, deeming that the little maiden had enough to do to trot on so many miles by her side, without having to carry a burden on her back in addition. Nelly would declare that she did not feel the weight, but the sturdy old dame generally gained her point, though she might consent to replenish Nelly’s basket before entering the town, for some of their customers preferred the fish which the bright little damsel offered them for sale to those in her grandmother’s creel.

Thus, though their daily toil was severe, and carried on under summer’s sun, or autumn’s gales, and winter’s rain and sleet, they themselves were ever cheerful and contented, and seldom failed to return home with empty creels and well-filled purses.

Paul Trefusis might thus have been able to lay by a store for the time when the dame could no longer trudge over the country as she had hitherto done, and he unable to put off with nets or lines to catch fish; but often for weeks together the gales of that stormy coast prevented him from venturing to sea, and the vegetables and potatoes produced in his garden, and the few fish he and Michael could catch in the harbour, were insufficient to support their little household, so that at the end of each year Paul found himself no richer than at the beginning.

While Nelly and her grandmother and the other women of the village were employed in selling the fish, the men had plenty of occupation during the day in drying and mending their nets, and repairing their boats, while some time was required to obtain the necessary sleep of which their nightly toil had deprived them. Those toilers of the sea were seldom idle. When bad weather prevented them from going far from the coast, they fished with lines, or laid down their lobster-pots among the rocks close inshore, while occasionally a few fish were to be caught in the waters of their little harbour. Most of them also cultivated patches of ground on the sides of the valley which opened out at the further end of the gorge, but, except potatoes, their fields afforded but precarious crops.

Paul and Michael had performed most of their destined task: the net had been spread along the rocks to dry, and two or three rents, caused by the fisherman’s foes, some huge conger or cod-fish, had been repaired. A portion of their fish had been sold to Abel Mawgan, and the remainder had been salted for their own use, when Paul, who had been going about his work with less than his usual spirit, complained of pains in his back and limbs. Leaving Michael to clean out the boat and moor her, and to bring up the oars and other gear, he went into the cottage to lie down and rest.

Little perhaps did the strong and hardy fisherman suppose, as he threw himself on his bunk in the little chamber where he and Michael slept, that he should never again rise, and that his last trip on the salt sea had been taken—that for the last time he had hauled his nets, that his life’s work was done. Yet he might have had some presentiment of what was going to happen as he sailed homewards that morning, when he resolved to tell Michael about his parents, and gave him the account of his father’s death which has been described.

The young fisher boy went on board the “Wild Duck,” and was busily employed in cleaning her out, thinking over what he had heard in the morning. Whilst thus engaged, he saw a small boat coming down from the head of the harbour towards him, pulled by a lad somewhat older than himself.

“There is Eban Cowan, the miller’s son. I suppose he is coming here. I wonder what he wants?” he thought. “The ‘Polly’ was out last night, and got a good haul, so it cannot be for fish.”

Michael was right in supposing that Eban Cowan was coming to their landing-place. The lad in the punt pulled up alongside the “Wild Duck.”

“How fares it with you, Michael?” he said, putting out his hand. “You did well this morning, I suspect, like most of us. Did Abel Mawgan buy all your ‘catch’? He took the whole of ours.”

“No, granny and Nelly started off to Helston with their creels full, as they can get a much better price than Mawgan will give,” answered Michael.

“I am sorry that Nelly is away, for I have brought her some shells I promised her a month ago. But as I have nothing to do, I will bide with you till she comes back.”

“She and granny won’t be back till late, I am afraid, and you lose your time staying here,” said Michael.

“Never mind, I will lend you a hand,” said Eban, making his punt fast, and stepping on board the “Wild Duck.”

He was a fine, handsome, broad-shouldered lad, with dark eyes and hair, and with a complexion more like that of an inhabitant of the south than of an English boy.

He took up a mop as he spoke, whisking up the bits of seaweed and fish-scales which covered the bottom of the boat.

“Thank you,” said Michael; “I won’t ask you to stop, for I must go and turn in and get some sleep. Father does not seem very well, and I shall have more work in the evening.”

“What is the matter with Uncle Paul?” asked Eban.

Michael told him that he had been complaining since the morning, but he hoped the night’s rest would set him to rights.

“You won’t want to go to sea to-night. It’s blowing hard outside, and likely to come on worse,” observed Eban.

Though he called Paul “uncle,” there was no relationship. He merely used the term of respect common in Cornwall when a younger speaks of an older man.

Eban, however, did not take Michael’s hint, but continued working away in the boat till she was completely put to rights.

“Now,” he said, “I will help you up with the oars and sails. You have more than enough to do, it seems to me, for a small fellow like you.”

“I am able to do it,” answered Michael; “and I am thankful that I can.”

“You live hard, though, and your father grows no richer,” observed Eban. “If he did as others do, and as my father has advised him many a time, he would be a richer man, and you and your sister and Aunt Lanreath would not have to toil early and late, and wear the life out of you as you do. I hope you will be wiser.”

“I know my father is right, whatever he does, and I hope to follow his example,” answered Michael, unstepping the mast, which he let fall on his shoulder preparatory to carrying it up to the shed.

“I was going to take that up,” said Eban; “it is too heavy for you by half.”

“It is my duty, thank you,” said Michael, somewhat coldly, stepping on shore with his burden.

Slight as he looked, he carried the heavy spar up the pathway and deposited it against the side of the house. He was returning for the remainder of the boat’s gear, when he met Eban with it on his shoulders.

“Thank you,” he said; “but I don’t want to give you my work to do.”

“It’s no labour to me,” answered Eban. “Just do you go and turn in, and I will moor the boat and make a new set of ‘tholes’ for you.”

Again Michael begged that his friend would not trouble himself, adding—

“If you have brought the shells for Nelly and will leave them with me, I will give them to her when she comes home.”

Nothing he could say, however, would induce Eban to go away. The latter had made up his mind to remain till Nelly’s return.

Still Michael was not to be turned from his purpose of doing his own work, though he could not prevent Eban from assisting him; and not till the boat was moored, and her gear deposited in the shed, would he consent to enter the cottage and seek the rest he required.

Meantime Eban, returning to his punt, shaped out a set of new tholes as he proposed, and then set off up the hill, hoping to meet Nelly and her grandmother.

He must have found them, for after some time he again came down the hill in their company, talking gaily, now to one, now to the other. He was evidently a favourite with the old woman.

Nelly thanked him with a sweet smile for the shells, which he had collected in some of the sandy little bays along the coast, which neither she nor Michael had ever been able to visit.

She was about to invite him into, the cottage, when Michael appeared at the door, saying, with a sad face—

“O granny! I am so thankful you are come; father seems very bad, and groans terribly. I never before saw him in such a way, and have not known what to do.”

Nelly on this darted in, and was soon by Paul’s bedside, followed by her grandmother.

Eban lingered about outside waiting. Michael at length came out to him again.

“There is no use waiting,” he said; and Eban, reluctantly going down to his boat, pulled away up the harbour.

Chapter Three.

Paul continued to suffer much during the evening; still he would not have the doctor sent for. “I shall get better maybe soon, if it’s God’s will, though such pains are new to me,” he said, groaning as he spoke.

The storm which had been threatening now burst with unusual strength. Michael, with the assistance of Nelly and her grandmother, got in the nets in time.

All hope of doing anything on the water for that night, at all events, must be abandoned; the weather was even too bad to allow Michael to fish in the harbour.

Little Nelly’s young heart was deeply grieved as she heard her father groan with pain—he who had never had a day’s illness that she could recollect. Nothing the dame could think of relieved him.

The howling of the wind, the roaring of the waves as they dashed against the rock-bound coast, the pattering of the rain, and ever and anon the loud claps of thunder which echoed among the cliffs, made Nelly’s heart sink within her. Often it seemed as if the very roof of the cottage would be blown off. Still she was thankful that her father and Michael were inside instead of buffeting the foaming waves out at sea.

If careful tending could have done Paul good he would soon have got well. The old dame seemed to require no sleep, and she would scarcely let either of her grandchildren take her place even for a few minutes. Though she generally went marketing, rather than leave her charge she sent Michael and Nelly to buy bread and other necessaries at the nearest village, which was, however, at some distance.

The rain had ceased, but the wind blew strong over the wild moor.

“I am afraid father is going to be very ill,” observed Michael. “He seemed to think something was going to happen to him when he told me what I did not know before about myself. Have you heard anything about it, Nelly?”

“What is it?” asked Nelly; “till you tell me I cannot say.”

“You’ve always thought that I was your brother, Nelly, haven’t you?”

“As to that, I have always loved you as a brother, and whether one or no, that should not make you unhappy. Has father said anything to you about it?”

“Yes. He said that I was not your brother; and he has told me all about my father and mother: how my father was drowned, and my mother died of a broken heart. I could well-nigh have cried when I heard the tale.”

Nelly looked up into Michael’s face.

“It’s no news to me,” she said. “Granny told me of it some time ago, but I begged her not to let you find it out lest it should make you unhappy, and you should fancy we were not going to love you as much as we have always done. But, Michael, don’t go and fancy that; though you are not my brother, I will love you as much as ever, as long as you live: for, except father and granny, I have no friend but you in the world.”

“I will be your brother and your true friend as long as I live, Nelly,” responded Michael; “still I would rather have thought myself to be your brother, that I might have a better right to work for you, and fight for you too, if needs be.”

“You will do that, I know, Michael,” said Nelly, “whatever may happen.”

Michael felt that he should be everything that was bad if he did not, though it did not occur to him to make any great promises of what he would do.

They went on talking cheerfully and happily together, for though Nelly was anxious about her father, she did not yet understand how ill he was.

They procured the articles for which they had been sent, and, laden with them, returned homewards. They were making their way along one of the hedges which divide the fields in that part of Cornwall—not composed of brambles but of solid rock, and so broad that two people can walk abreast without fear of tumbling off—and were yet some distance from the edge of the ravine down which they had to go to their home, when they saw Eban Cowan coming towards them.

“I wish he had gone some other way,” said Nelly. “He is very kind bringing me shells and other things, but, Michael, I do not like him. I do not know what it is, but there is something in the tone of his voice; it’s not truthful like yours and father’s.”

“I never thought about that. He is a bold-hearted, good-natured fellow,” observed Michael. “He has always been inclined to like us, and shown a wish to be friendly.”

“I don’t want to make him suppose that we are not friendly,” said Nelly; “only still—”

She was unable to finish the sentence, as the subject of their conversation had got close up to them.

“Good-day, Nelly; good-day, Michael,” he said, putting out his hand. “You have got heavy loads; let me carry yours, Nelly.”

She, however, declined his assistance.

“It is lighter than you suppose, and I can carry it well,” she answered.

He looked somewhat angry and then walked on, Michael having to give way to let him pass. Instead, however, of doing so, he turned round suddenly and kept alongside Nelly, compelling Michael in consequence to walk behind them.

“I went to ask after your father, Nelly,” he said, “and, hearing that you were away, came on to meet you. I am sorry to find he is no better.”

“Thank you,” said Nelly; “father is very ill, I fear; but God is merciful, and will take care of him and make him well if He thinks fit.”

Eban made no reply to this remark. He was not accustomed in his family to hear God spoken of except when that holy name was profaned by being joined to a curse.

“You had better let me take your creel, Nelly; it will be nothing to me.”

“It is nothing to me either,” answered Nelly, laughing. “I undertook to bring home the things, and I do not wish anybody else to do my work.”

Still Eban persisted in his offers; she as constantly refusing, till they reached the top of the pathway.

“There,” she said, “I have only to go down hill now, so you need not be afraid the load will break my back. Good-bye, Eban, you will be wanted at home I dare say.”

Eban looked disconcerted; he appeared to have intended to accompany her down the hill, but he had sense enough to see that she did not wish him to do so. He stopped short, therefore.

“Good-bye, Eban,” said Michael, as he passed him; “Nelly and I must get home as fast as we can to help granny nurse father.”

“That’s the work you are most fitted for,” muttered Eban, as Michael went on. “If it was not for Nelly I should soon quarrel with that fellow. He is always talking about his duty, and fearing God, and such like things. If he had more spirit he would not hold back as he does from joining us. However, I will win him over some day when he is older, and it is not so easy to make a livelihood with his nets and lines alone as he supposes.”

Eban remained on the top of the hill watching his young acquaintances as they descended the steep path, and then made his way homewards.

When Nelly and Michael arrived at the cottage the dame told them, to their sorrow, that their father was not better but rather worse. He still, however, forbad her sending for the doctor.

Day after day he continued much in the same state, though he endeavoured to encourage them with the hopes that he should get well at last.

The weather continued so bad all this time that Michael could not get out in the boat to fish with lines or lay down his lobster-pots. He and Nelly might have lost spirit had not their granny kept up hers and cheered them.

“We must expect bad times, my children, in this world,” she said. “The sun does not always shine, but when clouds cover the sky we know they will blow away at last and we shall have fine days again. I have had many trials in my life, but here I am as well and hardy as ever. We cannot tell why some are spared and some are taken away. It is God’s will, that’s all we know. It was His will to take your parents, Michael, but He may think fit to let you live to a green old age. I knew your father and mother, and your grandmother too. Your grandmother had her trials, and heavy ones they were. I remember her a pretty, bright young woman as I ever saw. She lived in a gentleman’s house as a sort of nurse or governess, where all were very fond of her, and she might have lived on in the house to the end of her days; but she was courted by a fine-looking fellow, who passed as the captain of a merchant vessel. A captain he was, though not of an honest trader, as he pretended, but of a smuggling craft, of which there were not a few in those days off this coast. The match was thought a good one for Nancy Trewinham when she married Captain Brewhard. They lived in good style and she was made much of, and looked upon as a lady, but before long she found out her husband’s calling, and right-thinking and good as she was she could not enjoy her riches. She tried to persuade her husband to abandon his calling, but he laughed at her, and told her that if it was not for that he should be a beggar.

“He moved away from Penzance, where he had a house, and after going to two or three other places, came to live near here. They had at this time two children, a fine lad of fifteen or sixteen years old, and your mother Judith.

“The captain was constantly away from home, and, to the grief of his wife, insisted on taking his boy with him. She well knew the hazardous work he was engaged in; so did most of the people on the coast, though he still passed where he lived for the master of a regular merchantman.

“There are some I have known engaged in smuggling for years, who have died quietly in their beds, but many, too, have been drowned at sea or killed in action with the king’s cruisers, or shot landing their goods.

“There used to be some desperate work going on along this coast in my younger days.

“At last the captain, taking his boy with him, went away in his lugger, the ‘Lively Nancy,’ over to France. She was a fine craft, carrying eight guns, and a crew of thirty men or more. The king’s cruisers had long been on the watch for her. As you know, smugglers always choose a dark and stormy night for running their cargoes. There was a cutter at the time off the coast commanded by an officer who had made up his mind to take the ‘Lively Nancy,’ let her fight ever so desperately. Her captain laughed at his threats, and declared that he would send her to the bottom first.

“I lived at that time with my husband and Nelly’s mother, our only child, at Landewednach. It was blowing hard from the south-west with a cloudy sky, when just before daybreak a sound of firing at sea was heard. There were few people in the village who did not turn out to try and discover what was going on. The morning was dark, but we saw the flashes of guns to the westward, and my husband and others made out that there were two vessels engaged standing away towards Mount’s Bay. We all guessed truly that one was the ‘Lively Nancy,’ and the other the king’s cutter.

“Gradually the sounds of the guns grew less and the flashes seemed further off. After some time, however, they again drew near. It was evident that the cutter had attacked the lugger, which was probably endeavouring to get away out to sea or to round the Lizard, when, with a flowing sheet before the wind, she would have a better chance of escape.

“Just then daylight broke, and we could distinguish both the vessels close-hauled, the lugger to leeward trying to weather on the cutter, which was close to her on her quarter, both carrying as much sail as they could stagger under. They kept firing as fast as the guns could be loaded, each trying to knock away her opponent’s spars, so that more damage was done to the rigging than to the crews of the vessels.

“The chief object of the smugglers was to escape, and this they hoped to do if they could bring down the cutter’s mainsail. The king’s officer knew that he should have the smugglers safe enough if he could but make them strike; this, however, knowing that they all fought with ropes round their necks, they had no thoughts of doing.

“Though the lugger stood on bravely, we could see that she was being jammed down gradually towards the shore. My good man cried out, ‘that her fore-tack was shot away and it would now go hard with her.’

“The smugglers, however, in spite of the fire to which they were exposed, got it hauled down. The cutter was thereby enabled to range up alongside.

“By this time the two vessels got almost abreast of the point, but there were the Stags to be weathered. If the lugger could do that she might then keep away. There seemed a good chance that she would do it, and many hoped she would, for their hearts were with her rather than with the king’s cruiser.

“She was not a quarter of a mile from the Stags when down came her mainmast. It must have knocked over the man at the helm and injured others standing aft, for her head fell off and she ran on directly for the rocks. Still her crew did their best to save her. The wreck was cleared away, and once more she stood up as close as she could now be kept to the wind. One of her guns only was fired, for the crew had somewhat else to do just then. The cutter no longer kept as close to her as before; well did her commander know the danger of standing too near those terrible rocks, over which the sea was breaking in masses of foam.

“There seemed a chance that the lugger might still scrape clear of the rocks; if not, in a few moments she must be dashed to pieces and every soul on board perish.

“I could not help thinking of the poor lad whom his father had taken with him in spite of his mother’s tears and entreaties. It must have been a terrible thought for the captain that he had thus brought his young son to an untimely end. For that reason I would have given much to see the lugger escape, but it was not to be.

“The seas came rolling in more heavily than before. A fierce blast struck her, and in another instant, covered with a shroud of foam, she was dashed against the wild rocks, and when we looked again she seemed to have melted away—not a plank of her still holding together.

“The cutter herself had but just weathered the rocks, and though she stood to leeward of them on the chance of picking up any of the luggers crew who might have escaped, not one was found.

“Such was the end of the ‘Lively Nancy,’ and your bold grandfather. Your poor grandmother never lifted up her head after she heard of what had happened. Still she struggled on for the sake of her little daughter, but by degrees all the money she possessed was spent. She at once moved into a small cottage, and then at last she and her young daughter found shelter in a single room. After this she did not live long, and your poor mother was left destitute. It was then your father met her, and though she had more education than he had, and remembered well the comfort she had once enjoyed, she consented to become his wife. He did his best for her, for he was a true-hearted, honest man, but she was ill fitted for the rough life a fisherman’s wife has to lead, and when the news of her husband’s death reached her she laid down and died.

“There, Michael, now you have learned all you are ever likely to know of your family, for no one can tell you more about them than I can.

“You see you cannot count upon many friends in the world except those you make yourself. But there is one Friend you have Who will never, if you trust to Him, leave or forsake you. He is truer than all earthly friends, and Paul Trefusis has acted a father’s part in bringing you up to fear and honour Him.”

“I do trust God, for it is He you speak of, granny,” said Michael, “and I will try to love and obey Him as long as I live. He did what He knew to be best when He took my poor father away, and gave me such a good one as he who lies sick in there. I wish, granny, that you could have given me a better account of my grandfather.”

“I thought it best that you should know the truth, Michael, and as you cannot be called to account for what he was, you need not trouble yourself about that matter. Your grandmother was an excellent woman, and I have a notion that she was of gentle blood, so it is well you should remember her name, and you may some day hear of her kith and kin: not that you are ever likely to gain anything by that; still it’s a set-off against what your grandfather was, though people hereabouts will never throw that in your face.”

“I should care little for what they may say,” answered Michael; “all I wish is to grow into a strong man to be able to work for you and Nelly and poor father, if he does not gain his strength. I will do my best now, and when the pilchard season comes on I hope, if I can get David Treloar or another hand in the boat, to do still better.”

Chapter Four.

Day after day Paul Trefusis lay on his sick-bed. A doctor was sent for, but his report was unfavourable. Nelly asked him, with trembling lips, whether he thought her father would ever get well.

“You must not depend too much on that, my little maiden,” he answered; “but I hope your brother, who seems an industrious lad, and that wonderful old woman, your grandmother, will help you to keep the pot boiling in the house, and I dare say you will find friends who will assist you when you require it. Good-bye; I’ll come and see your father again soon; but all I can do is to relieve his pain.”

Dame Lanreath and Michael did, indeed, do their best to keep the pot boiling: early and late Michael was at work, either digging in the garden, fishing in the harbour, or, when the weather would allow him, going with the boat outside. Young as he was, he was well able, under ordinary circumstances, to manage her by himself, though, of course, single-handed, he could not use the nets.

Though he toiled very hard, he could, however, obtain but a scanty supply of fish. When he obtained more than were required for home consumption, the dame would set off to dispose of them; but she had no longer the companionship of Nelly, who remained to watch over her poor father.

When Paul had strength sufficient to speak, which he had not always, he would give his daughter good advice, and warn her of the dangers to which she would be exposed in the world.

“Nelly,” he said, “do not trust a person with a soft-speaking tongue, merely because he is soft-speaking; or one with good looks, merely because he has good looks. Learn his character first—how he spends his time, how he speaks about other people, and, more than all, how he speaks about God. Do not trust him because he says pleasant things to you. There is Eban Cowan, for instance, a good-looking lad, with pleasant manners; but he comes of a bad stock, and is not brought up to fear God. It is wrong to speak ill of one’s neighbours, so I have not talked of what I know about his father and his father’s companions; but, Nelly dear, I tell you not to trust him or them till you have good cause to do so.”

Nelly, like a wise girl, never forgot what her father said to her.

After this Paul grew worse. Often, for days together, he was racked with pain, and could scarcely utter a word. Nelly tended him with the most loving care. It grieved her tender heart to see him suffer; but she tried to conceal her sorrow, and he never uttered a word of complaint.

Michael had now become the main support of the family; for though Paul had managed to keep out of debt and have a small supply of money in hand, yet that was gradually diminishing.

“Never fear, Nelly,” said Michael, when she told him one day how little they had left; “we must hope for a good pilchard-fishing, and we can manage to rub on till then. The nets are in good order, and I can get the help I spoke of; so that I can take father’s place, and we shall have his share in the company’s fishing.”

Michael alluded to a custom which prevails among the fishermen on that coast. A certain number, who possess boats and nets, form a company, and fish together when the pilchards visit their coast, dividing afterwards the amount they receive for the fish caught.

“It is a long time to wait till then,” observed Nelly.

“But on most days I can catch lobsters and crabs, and every time I have been out lately the fish come to my lines more readily than they used to do,” answered Michael. “Do not be cast down, Nelly dear, we have a Friend in heaven, as father says, Who will take care of us; let us trust Him.”

Time passed on. Paul Trefusis, instead of getting better, became worse and worse. His once strong, stout frame was now reduced to a mere skeleton. Still Nelly and Michael buoyed themselves up with the hope that he would recover. Dame Lanreath knew too well that his days on earth were drawing to an end.

Michael had become the mainstay of the family. Whenever a boat could get outside, the “Wild Duck” was sure to be seen making her way towards the best fishing-ground.

Paul, before he started each day, inquired which way the wind was, and what sea there was on, and advised him where to go. “Michael,” said Paul, as the boy came one morning to wish him good-bye, “fare thee well, lad; don’t forget the advice I have given thee, and look after little Nelly and her grandmother, and may God bless and prosper thee;” and taking Michael’s hand, Paul pressed it gently. He had no strength for a firm grasp now.

Michael was struck by his manner. Had it not been necessary to catch some fish he would not have left the cottage.

Putting the boat’s sail and other gear on board, he pulled down the harbour. He had to pull some little way out to sea. The wind was setting on shore. He did not mind that, for he should sail back the faster. The weather did not look as promising as he could have wished: dark clouds were gathering to the north-west and passing rapidly over the sky. As he knew, should the wind stand, he could easily regain the harbour, he went rather more to the southward than he otherwise would have done, to a good spot, where he had often had a successful fishing. He had brought his dinner with him, as he intended to fish all day. His lines were scarcely overboard before he got a bite, and he was soon catching fish as fast as he could haul his lines on board. This put him in good spirits.

“Granny will have her creel full to sell to-morrow,” he thought. “Maybe I shall get back in time for her to set off to-day.”

So eagerly occupied was he that he did not observe the change of the weather. The wind had veered round more to the northward. It was every instant blowing stronger and stronger, although, from its coming off the land, there was not much sea on.

At last he had caught a good supply of fish. By waiting he might have obtained many more, but he should then be too late for that day’s market. Lifting his anchor, therefore, he got out his oars and began to pull homewards. The wind was very strong, and he soon found that, with all his efforts, he could make no headway. The tide, too, had turned, and was against him, sweeping round in a strong current to the southward. In vain he pulled. Though putting all the strength he possessed to his oars, still, as he looked at the shore, he was rather losing than gaining ground. He knew that the attempt to reach the harbour under sail would be hopeless; he should be sure to lose every tack he made. Already half a gale of wind was blowing, and the boat, with the little ballast there was in her, would scarcely look up even to the closest reefed canvas.

Again he dropped his anchor, intending to wait the turn of the tide, sorely regretting that he could not take the fish home in time for granny to sell on that day.

Dame Lanreath and Nelly had been anxiously expecting Michael’s return, and the dame had got ready to set off as soon as he appeared with the fish they hoped he would catch. Still he did not come.

Paul had more than once inquired for him. He told Nelly to go out and see how the wind was, and whether there was much sea on.

Nelly made her way under the cliffs to the nearest point whence she could obtain a view of the mouth of the harbour and the sea beyond. She looked out eagerly for Michael’s boat, hoping to discover her making her way towards the shore; but Nelly looked in vain. Already there was a good deal of sea on, and the wind, which had been blowing strong from the north-west, while she was standing there veered a point or two more to the northward.

“Where could Michael have gone?” She looked and looked till her eyes ached, still she could not bring herself to go back without being able to make some report about him. At last she determined to call at the cottage of Reuben Lanaherne, a friend of her father’s, though a somewhat older man.

“What is it brings you here, my pretty maiden?” said Uncle Reuben, who, for a wonder, was at home, as Nelly, after gently knocking, lifted the latch and entered a room with sanded floor and blue painted ceiling.

“O Uncle Lanaherne,” she said, “can you tell me where you think Michael has gone? he ought to have been back long ago.”

“He would have been wiser not to have gone out at all with the weather threatening as it has been; but he is a handy lad in a boat, Nelly, and he will find his way in as well as any one, so don’t you be unhappy about him,” was the answer.

Still Reuben looked a little anxious, and putting on his hat, buttoning up his coat, and taking his glass under his arm, he accompanied Nelly to the point. He took a steady survey round.

“Michael’s boat is nowhere near under sail,” he observed. “There seems to me a boat, however, away to the southward, but, with the wind and tide as at present, she cannot be coming here. I wish I could make out more to cheer you, Nelly. You must tell your father that; and he knows if we can lend Michael a hand we will. How is he to-day?”

“He is very bad, Uncle Lanaherne,” said Nelly, with a sigh; “I fear sometimes that he will never go fishing again.”

“I am afraid not, Nelly,” observed the rough fisherman, putting his hand on her head; “but you know you and your brother will always find a friend in Reuben Lanaherne. An honest man’s children will never want, and if there ever was an honest man, your poor father is one. I will keep a look-out for Michael, but do not be cast down, Nelly; we shall see him before long.”

The fisherman spoke in a cheery tone, but still he could not help feeling more anxiety than he expressed for Michael.

Every moment the wind was increasing, and the heavy seas which came rolling in showed that a gale had been blowing for some time outside.

Nelly hastened back to tell her father what Uncle Lanaherne had said.

When she got to his bedside she found that a great change had taken place during her absence. Her father turned his dim eye towards her as she entered, but had scarcely strength to speak, or beckon her with his hands. She bent over him.

“Nelly dear, where is Michael?” he asked, “I want to bless him, he must come quickly, for I have not long to stay.”

“He has not come on shore yet, father, but Uncle Lanaherne is looking out for him,” said Nelly.

“I wanted to see him again,” whispered Paul. “It will be too late if he does not come now; so tell him, Nelly, that I do bless him, and I bless you, Nelly, bless you, bless you;” and his voice became fainter.

Nelly, seeing a change come over her father’s features, cried out for her granny. Dame Lanreath hastened into the room. The old woman saw at a glance what had happened. Paul Trefusis was dead.

Closing his eyes, she took her grandchild by the hand, and led her out of the room.

Some time passed, however, before Nelly could realise what had happened.

“Your father has gone, Nelly, but he has gone to heaven, and is happier far than he ever was or ever could be down on earth even in the best of times. Bad times may be coming, and God in His love and mercy took him that he might escape them.”

“But, then, why didn’t God take us?” asked Nelly, looking up. “I would have liked to die with him. Bad times will be as hard for us to bear as for him.”

“God always does what is best, and He has a reason for keeping us on earth,” answered the dame. “He has kept me well-nigh fourscore years, and given me health and strength, and good courage to bear whatever I have had to bear, and He will give you strength, Nelly, according to your need.”

“Ah, I was wicked to say what I did,” answered Nelly; “but I am sad about father and you and myself, and very sad, too, about Michael. He will grieve so when he comes home and finds father gone, if he comes at all. And, O granny, I begin to fear that he won’t come home! what has happened to him I cannot tell; and if you had seen the heavy sea there was rolling outside you would fear the worst.”

“Still, Nelly, we must trust in God; if He has taken Michael, He has done it for the best, not the worst, Nelly,” answered Dame Lanreath. “But when I say this, Nelly, I don’t want to stop your tears, they are given in mercy to relieve your grief; but pray to God, Nelly, to help us; He will do so—only trust Him.”

Chapter Five.

The day was drawing to a close when the storm, which had been threatening all the morning on which Paul Trefusis died, swept fiercely up the harbour, showing that the wind had again shifted to the westward.

Poor Nelly, though cast down with grief at her father’s death, could not help trembling as she thought of Michael, exposed as she knew he must be to its rage. Was he, too, to be taken away from them?

She was left much alone, as Dame Lanreath had been engaged, with the assistance of a neighbour, in the sad duty of laying out the dead man. Nelly several times had run out to look down the harbour, hoping against hope that she might see Michael’s boat sailing up it.

At length, in spite of the gale, she made her way to Reuben Lanaherne’s cottage. His wife and daughter were seated at their work, but he was not there. Agitated and breathless from encountering the fierce wind, she could scarcely speak as she entered.

“Sit down, maiden; what ails thee?” said Dame Lanaherne, rising, and kindly placing her on a stool by her side.

Nelly could only answer with sobs.

Just then old Reuben himself entered, shaking the spray from his thick coat.

“How is thy father, Nelly?” he asked.

“He has gone,” she answered, sobbing afresh. “And, O Uncle Reuben, have you seen Michael’s boat? can you tell me where he is?”

“I have not forgotten him, Nelly, and have been along the shore as far as I could make my way on the chance that he might have missed the harbour, and had run for Kynance Cove, but not a sign of him or his boat could I see. I wish I had better news for you, Nelly. And your good father gone too! Don’t take on so—he is free from pain now—happy in heaven; and there is One above Who will look after Michael, though what has become of him is more than I can tell you.”

The old fisherman’s words brought little comfort to poor Nelly, though he and his wife and daughter did their best to console her. They pressed her to remain with them, but she would not be absent longer from her granny, and, thanking them for their kindness, hurried homewards.

The wind blew fiercely, but no rain had as yet fallen.

Their neighbour, having rendered all the assistance required, had gone away, and the old dame and her young grandchild sat together side by side in the outer room. They could talk only of Michael. The dame did not dare to utter what she thought. His small boat might have been swamped in the heavy sea, or he might have fallen overboard and been unable to regain her; or, attempting to land on a rocky coast, she might have been dashed to pieces, and he swept off by the receding surf. Such had been the fate of many she had known.

As each succeeding gust swept by, poor Nelly started and trembled in spite of her efforts to keep calm.

At length down came the rain battering against the small panes of glass.

At that instant there was a knocking at the door.

“Can you give us shelter from the storm, good folks?” said a voice; and, the latch being lifted, an elderly gentleman, accompanied by two ladies, one of whom was young and the other more advanced in life, appeared at the entrance.

They evidently took it for granted that they should not be denied.

“You are welcome, though you come to a house of mourning,” said Dame Lanreath, rising, while Nelly hastened to place stools for them to sit on.

“I am afraid, then, that we are intruders,” said the gentleman, “and we would offer to go on, but my wife and daughter would be wet through before we could reach any other shelter.”

“We would not turn any one away, especially you and Mistress Tremayne,” said the dame, looking at the elder lady.

“What! do you know us?” asked the gentleman.

“I know Mistress Tremayne and the young lady from her likeness to what I recollect of her mother,” answered Dame Lanreath. “I seldom forget a person I once knew, and she has often bought fish of me in days gone by.”

“And I, too, recollect you. If I mistake not you used to be pretty widely known as Polly Lanreath,” said the lady, looking at the old fish-wife.

“And so I am now, Mistress Tremayne,” answered the dame, “though not known so far and wide as I once was. I can still walk my twenty miles a-day; but years grow on one; and when I see so many whom I have known as children taken away, I cannot expect to remain hale and strong much longer.”

“You have altered but little since I knew you,” observed Mrs Tremayne, “and I hope that you may retain your health and strength for many years to come.”

“That’s as God wills,” said the dame. “I pray it may be so for the sake of my little Nelly here.”

“She is your grandchild, I suppose,” observed Mrs Tremayne.

“Ay, and the only one I have got to live for now. Her father has just gone, and she and I are left alone.”

“O granny, but there is Michael; don’t talk of him as gone,” exclaimed Nelly. “He will come back, surely he will come back.”

This remark of Nelly’s caused Mr and Mrs Tremayne to make further inquiries.

They at first regretted that they had been compelled to take shelter in the cottage, but as the dame continued talking, their interest in what she said increased.

“It seemed strange, Mistress Tremayne, that you should have come here at this moment,” she observed. “Our Michael is the grandson of one whom you knew well in your childhood; she was Nancy Trewinham, who was nurse in the family of your mother, Lady Saint Mabyn; and you, if I mistake not, were old enough at the time to remember her.”

“Yes, indeed, I do perfectly well; and I have often heard my mother express her regret that so good and gentle a young woman should have married a man who, though apparently well-to-do in the world, was more than suspected to be of indifferent character,” said the lady. “We could gain no intelligence of her after she left Penzance, though I remember my father saying that he had no doubt a noted smuggler whose vessel was lost off this coast was the man she had married. Being interested in her family, he made inquiries, but could not ascertain whether she had survived her unhappy husband or not. And have you, indeed, taken charge of her grandson in addition to those of your own family whom you have had to support?”

“It was not I took charge of the boy, but my good son-in-law, who lies dead there,” said the dame. “He thought it but a slight thing, and only did what he knew others would do by him.”

“He deserved not the less credit,” said Mr Tremayne. “We shall, indeed, be anxious to hear that the boy has come to no harm, and I am sure that Mrs Tremayne will be glad to do anything in her power to assist you and him should he, as I hope, have escaped. We purpose staying at Landewednach for a few days to visit the scenery on the coast, and will send down to inquire to-morrow.”

While Mr and Mrs Tremayne and the old dame had been talking, Miss Tremayne had beckoned to Nelly to come and sit by her, and, speaking in a kind and gentle voice, had tried to comfort the young girl. She, however, could only express her hope that Michael had by some means or other escaped. Though Nelly knew that that hope was vain, the sympathy which was shown her soothed her sorrow more than the words which were uttered.

Sympathy, in truth, is the only balm that one human being can pour into the wounded heart of another. Would that we could remember that in all our grief and sufferings we have One in heaven Who can sympathise with us as He did when He wept with the sorrowing family at Bethany.

The rain ceased almost as suddenly as it had commenced, and as Mr and Mrs Tremayne, who had left their carriage on the top of the hill, were anxious to proceed on their journey, they bade Dame Lanreath and Nelly good-bye, again apologising for having intruded on them.

“Don’t talk of that please, Mistress Tremayne,” said the old dame. “Your visit has been a blessing to us, as it has taken us off our own sad thoughts. Nelly already looks less cast down, from what the young lady has been saying to her, and though you can’t bring the dead to life we feel your kindness.”

“You will let me make it rather more substantial, then, by accepting this trifle, which may be useful under the present circumstances,” said the gentleman, offering a couple of guineas.

The old dame looked at them, a struggle seemed to be going on within her.

“I thank you kindly, sir, that I do,” she answered; “but since my earliest days I have gained my daily bread and never taken charity from any one.”

“But you must not consider this as charity, dame,” observed Mrs Tremayne; “it is given to show our interest in your little granddaughter and in the boy whom your son-in-law and you have so generously protected so many years. I should, indeed, feel bound to assist him, and therefore on his account pray receive it and spend it as you may require.”

The dame’s scruples were at length overcome, and her guests, after she had again expressed her feelings of gratitude, took their departure.

They had scarcely gone when Eban Cowan appeared at the door.

“I have just heard what has happened, and I could not let the day pass without coming to tell you how sorry I am,” he said, as he entered.

Nelly thanked him warmly.

“Father has gone to heaven and is at rest,” she said, quietly.

“I should think that you would rather have had him with you down on earth,” observed Eban, who little comprehended her feelings.

“So I would, but it was God’s will to take him, and he taught me to say, ‘Thy will be done;’ and I can say that though I grieve for his loss,” answered Nelly. “But, O Eban, when you came I thought that you had brought some tidings of Michael.”

“No! Where is he? I did not know that he was not at home.”

Nelly then told Eban how Michael had gone away with the boat in the morning and had not returned. “I will go and search for him then,” he said. “He has run in somewhere, perhaps, along the coast. I wonder, when you spoke to Uncle Lanaherne, that he did not set off at once. But I will go. I’ll get father to send some men with me with ropes, and if he is alive and clinging to a rock, as he may be, we will bring him back.”

Nelly poured out her thanks to Eban, who, observing that there was no time to be lost, set off to carry out his proposal.

Dame Lanreath had said but little. She shook her head when he had gone, as Nelly continued praising him.

“He is brave and bold, Nelly, but that could be said of Captain Brewhard and many others I have known, who were bad husbands and false friends, and there is something about the lad I have never liked. He is inclined to be friendly now; and as you grow up he will wish, maybe, to be more friendly; but I warn you against him, Nelly dear. Though he speaks to you ever go fair, don’t trust him.”

“But I must be grateful to him as long as I live if he finds Michael,” answered Nelly, who thought her grandmother condemned Eban without sufficient cause.

Had she known how he had often talked to Michael, she might have been of a different opinion.

The storm continued to blow as fiercely as ever, and the rain again came pelting down; ever and anon peals of thunder rattled and crashed overhead, and flashes of lightning, seen more vividly through the thickening gloom, darted from the sky.

Dame Lanreath and Nelly sat in their cottage by the dead—the old woman calm and unmoved, though Nelly, at each successive crash of thunder or flash of lightning, drew closer to her grandmother, feeling more secure in the embrace of the only being on whom she had now to rely for protection in the wide world.

Chapter Six.

Young Michael sat all alone in his boat, tossed about by the foaming seas. His anchor held, so there was no fear of his drifting. But that was not the only danger to which he was exposed. At any moment a sea might break on board and wash him away, or swamp the boat.

He looked round him, calmly considering what was best to be done. No coward fear troubled his mind, yet he clearly saw the various risks he must run. He thought of heaving his ballast overboard and trying to ride out the gale where he was, but then he must abandon all hope of reaching the harbour by his own unaided efforts. He might lash himself to a thwart, and thus escape being washed away; still the fierce waves might tear the boat herself to pieces, so that he quickly gave up that idea. He was too far off to be seen from the shore, except perhaps by the keen-sighted coast-guard men; but even if seen, what boat would venture out into the fast-rising sea to his rescue. He must, he felt, depend upon himself, with God’s aid, for saving his life.

Any longer delay would only increase his peril. The wind and tide would prevent him gaining any part of the coast to the northward. He would therefore make sail and run for Landewednach, for not another spot where he had the slightest prospect of landing in safety was to be found between the Gull Rock and the beach at that place. He very well knew, indeed, the danger he must encounter even there, but it was a choice of evils. He quickly made up his mind.

He at first set to work to bail out the boat, for already she had shipped a good deal of water. He had plenty of sea room, so that he might venture to lift his anchor. But it was no easy work, and the sea, which broke over the bows again and again, made him almost relinquish the effort, and cut the cable instead. Still he knew the importance of having his anchor ready to drop, should he be unable to beach the boat on his arrival at the spot he had selected, so again he tried, and up it came. He quickly hauled it in, and running up his sail he sprang to the tiller, hauling aft his main-sheet.

Away flew the boat amid the tumbling seas, which came rolling in from the westward. He held the sheet in his hand, for there was now as much wind as the boat could look up to, and a sudden blast might at any moment send her over. That, too, Michael knew right well. On she flew like a sea-bird amid the foaming waves, now lifted to the summit of one, now dropping down into the hollow, each sea as it came hissing up threatening to break on board; now he kept away to receive its force on his quarter; now he again kept his course.

The huge Gull Rock rose up under his lee, the breakers dashing furiously against its base; then Kynance Cove, with its fantastically-shaped cliffs, opened out, but the sea roared and foamed at their base, and not a spot of sand could he discover on which he could hope to beach his boat, even should he pass through the raging surf unharmed. Meantale Point, Pradanack, and the Soapy Rock appeared in succession, but all threatened him alike with destruction should he venture near them.

He came abreast of a little harbour, but he had never been in there, and numerous rocks, some beneath the surface, others rising but just above it, lay off its entrance, and the risk of running for it he considered was too great to be encountered. Those on shore might have seen his boat as she flew by, but, should they have done so, even the bravest might have been unwilling to risk their lives on the chance of overtaking her before she met that fate to which they might well have believed she was doomed.

Michael cast but a glance or two to ascertain whether any one was coming; he had little expectation of assistance, but still his courage did not fail him.

The rocks were passed; he could already distinguish over his bow the lighthouses on the summit of the Lizard Point. Again he kept away and neared the outer edge of a line of breakers which roared fiercely upon it. He must land there notwithstanding, or be lost, for he knew that his boat could not live going through the race to the southward of the Lizard.

When off the Stags he could distinguish people moving along the shore. He had been seen by them he knew, and perhaps a boat might be launched and come to his rescue. There was no time, however, for consideration. What he had to do must be promptly done.

The water in the bay was somewhat smoother than it had hitherto been. In a moment his sail was lowered and his anchor let go. The rain came down heavily.

“The wind is falling,” he thought; “I will wait till the turn of the tide, when, perhaps, there will be less surf on.”