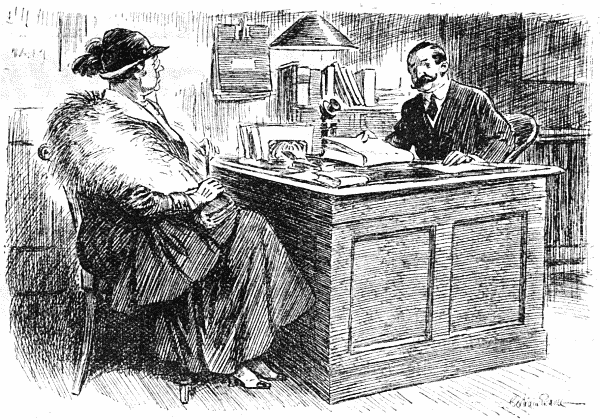

Lady (to manager of Servants' Registry). "I wish to obtain a new governess."

Manager. "Well, Madam, you remember we supplied you with one only last week, but, judging by the report we have received, what you really need is a lion-tamer."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 158, April 28, 1920, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 158, April 28, 1920 Author: Various Editor: Owen Seaman Release Date: September 17, 2007 [EBook #22653] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, VOL. 158, APRIL 28, 1920 *** Produced by V. L. Simpson, Jonathan Ingram and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

General Denikin is now in London. This is the first visit he has paid to this country since his last assassination by the Bolshevists.

New proposals regarding telephone charges are expected as soon as the Select Committee has reported. If the system of charging by time in place of piece-work is adopted it will mean ruination to many business-men.

The Swiss Government has issued orders that ex-monarchs may enter the country without passports. It is required, however, that they should take their places in the queue.

It is reported that a Londonderry man walked up to a Sinn Feiner the other day and said, "Shoot me." We understand that the real reason why the fellow was not accommodated was that he omitted to say "Please." The best Sinn Feiners are very punctilious.

"The drinking of intoxicants," says an American prohibitionist, "causes early death in ninety-five cases out of a hundred." Several Americans, we are informed, have gallantly offered themselves for experimental purposes.

"It is a scandal," says a contemporary, "that the clerks at Llanelly should ask for twelve pounds fifteen shillings a week." But surely there is no harm in asking.

According to a weekly paper not only is Constance Binney a famous screen star, but she is also a first-class ukelele player. The latest reports are that the news has been received quietly.

"If slightly cut before cooking, potatoes slip out of their skins easily," says a home journal. This is better than frightening them out of their skins by jumping out from behind a door and saying "Boo."

Mr. William Aird, the germ-proof man, has been giving demonstrations in London. It is reported that last week a germ snapped at him and broke off two of its teeth.

"In New York the other day," says a contemporary, "the sky kept streaming silver sheen; mistlike lights pulsated in rapid flashes to the apex and piled-up stars could be seen." The fact that New York can still see things like this must be a sorry blow to the Prohibitionists.

"Working men have been hit very hard by the tyrannical Budget," announces a morning paper. We too are in sympathy with those miners who are now faced with only one bottle of champagne a day.

"These cotton boom profits," said the President of the Textile Institute recently, "are abnormal and unhealthy." The Manchester man, however, who recently came out with innumerable spots resembling half-crowns as the result of the boom, declares that no inconvenience is suffered once the dizziness has passed away.

From Bungay in Suffolk comes the news that a water-wagtail has built its nest in a milk-can. We resolutely refrain from comment.

A youth recently arrested in Dublin was found not to have a revolver on him. He is being detained for a medical examination.

A great many people are committing suicide, says the Vicar of St. Mathew's, Portsmouth, because they have nothing to live for. We disagree. The Weekly Dispatch's accounts of the next world are well worth staying alive for.

Airships under construction, declares Air-Commodore E. M. Maitland, will make the passage to Australia in nine and a-half days. In tax-paying circles it is said that the fashionable thing will be to start now and let the airship overtake you if it can.

More than a million Americans, it is stated, are preparing to visit Europe this summer. It is thought that there is at least a sporting chance that some of them will be hoist with their own bacon.

"The man who does not know Latin," says the Dean of Durham, "is not really educated." Several uneducated business men are said to have written to the Dean asking the Latin for what they think of the new Budget.

At a recent wedding in Tyrone young men who had come to wish the bride and bridegroom luck lit a fire against the door, blocked the chimney with straw, broke the windows, threw water and cayenne-pepper on the wedding-party and bombarded the house with stones for two hours. It is just this joyous, care-free nature of the Irish that the stolid Englishman will never learn to appreciate.

We understand that the man who tried to gain admission to the Zoo on Sunday by making a noise like a Fellow of the Zoological Society was detected in the act.

A person who recently attempted to commit suicide by lying down on the Caledonian Railway line was found to have a razor in one pocket and a bottle of laudanum in the other. The Company, we understand, strenuously deny the necessity of these alternatives.

Lady (to manager of Servants' Registry). "I wish to obtain a new governess."

Manager. "Well, Madam, you remember we supplied you with one only last week, but, judging by the report we have received, what you really need is a lion-tamer."

"The christening ceremony was performed by Lady Maclay, wife of the Shipping Controller. Thousands of people saw her go down the slips, and cheers were raised as she took the water without the slightest hitch."

Daily News.

We gather from the expression, "without the slightest hitch," that not one of the onlookers made any effort to save the lady.

By a Patriot.

O. S.

The public torturer hurried home in an irritable frame of mind. The day had been for him one long round of annoyances. When he commenced his duties that morning, already exasperated by the thought that if the drought continued the produce of his tiny patch of ground would be completely ruined, he was aggrieved to find that far more than his fair share of a recently arrived batch of heretics had been allotted to him. During the midday break for refreshments his dreamy assistant had allowed the furnace to go out, bringing upon the torturer's own head a severe censure for the consequent delay. In the afternoon, glancing occasionally through the narrow window, he was mortified to see that the promising rain-clouds, which might yet have saved his cabbages, were dispersing; and then, to crown all, just as he was finishing for the day he had caught hold of a pair of pincers a trifle too near the white-hot end and seared his hand.

As he approached the cottage which was enshrined in his heart by a thousand sacred associations as home, the torturer strove to rise superior to his worries. He whistled bravely as he crossed the threshold and caressed his wife with his usual tenderness. Intuitively she divined the bitterness of the mood which lay beneath the torturer's seeming cheerfulness, but she stifled her curiosity like the wise little woman she was and hastened to lay his supper before him. Through the progress of the meal—prepared by her in the way the torturer loved so well—she diverted him with her lively prattle. And at length, when she trod on the dog and caused it to give out a long-drawn howl, she made such a neat allusion to the Chamber and heretics that the torturer laughed till the tears streamed down his cheeks.

After the table was cleared the torturer's little blue-eyed girl came toddling up to him for her usual half-hour's cuddle. It made a beautiful picture—the little mite with her father's merry eyes and her mother's rosebud mouth, sitting on the torturer's knee, her golden hair mingling with his beard. And how her silvery laugh brightened the place as she played her favourite game of stretching her rag doll on a toy model of a rack.

The sound of rain outside brought the torturer and his wife to the door. As they stood side by side watching the downpour the last vestige of the torturer's ill-humour passed away. This rain would mean a record year for his cabbages, and would do wonders for his beans, which were already a long way more forward than those of the executioner.

He realised now that he had allowed the mishaps of the day to worry him unduly. After all, his hand had suffered little more than a scorch and no longer pained him, and, although the censure he had received in the Chamber and the possible consequences had been very disquieting, yet he was now able to assure himself and his wife that if henceforth he kept his assistant from wool-gathering all would be well.

Suddenly he fell back trembling from the threshold, his face blanched with terror. A large rain-drop had splashed on his forehead, reminding him abruptly that before coming home that evening he had neglected to fill the water-dripping apparatus, which might be required at dawn for the more obstinate of the heretics.

The fact that the Bishop-Elect of Pretoria, the Rev. Neville Talbot, is no less than six feet six inches high, surpassing his predecessor by two inches, has been freely commented on in the Press. Anxious to ascertain from leaders of public opinion the true significance of the appointment, Mr. Punch has been at pains to collect their views. How divergent and even contradictory they are may be gathered from the following selection:—

Sir Martin Conway, the Apostle of Altitude, as he has been recently denominated, welcomed the appointment of Bishop Talbot as a good omen for the campaign which he is so ably conducting. "Nothing," he remarks, "has impressed me so much in the works of Tennyson as the line, 'We needs must love the highest when we see it.' Mountain or building or man, it is all the same. I never felt so happy in all my travels in South America as when I was in Patagonia, the home of tall men and the giant sloth. At all costs we should recognise and cultivate the human skyscraper."

The Bishop of Hereford (Dr. Hensley Henson) expressed the hope that the appointment of bishops would not be governed solely by an anthropometric standard. It would be a misfortune if the impression were created that preferment to the episcopal bench was confined to High Churchmen.

The Editor of The Times declined to dogmatize on the subject. He pointed out however that the average height of the Yugo-Slavs exceeded that of the Welsh. The claims of small nations could not, of course, be overlooked, but he considered it as little short of a calamity when a Great Power had an undersized Prime Minister. Short men liked short cuts, but, as Bacon said, the shortest way is commonly the foulest.

Dr. Robert Bridges (the Poet-Laureate) writes to say that, having given special study to the hexameter, he was much interested to find that the measure now in vogue amongst bishops was that of six feet and over. He hoped [Pg 323] to treat the subject exhaustively in his forthcoming treatise on Ecclesiastical Prosody.

Colonel L. C. Amery, M.P., strongly deprecated the attempt to identify excessive height with extreme efficiency. In the election to Fellowships at All Souls no height limit was imposed. Napoleon and the late Lord Roberts were both small men, and he believed that the remarkable elusiveness displayed by Colonel Lawrence in the War was greatly facilitated by his diminutive stature. The testimony of literature throughout the ages was almost unanimous in its condemnation of giants. He had never heard of a small ogre. On the subject of Shakespeare's height he could not speak with assurance, but Keats was only just over five feet. Jumbomania, or the worship of mammoth dimensions, was a modern disease. Far better was the philosophy crystallised in such immortal sayings as "Love me little, love me long," and "Infinite riches in a little room."

Mr. Mallaby-Deeley, M.P., observed that, man being an imitative animal and bishops being regarded by many as good examples, there seemed to him a serious danger of an epidemic of what he might call Brobdingnagitis. Fortunately the results would not be immediately apparent, otherwise he would be compelled to raise his tariff for cheap suits. A rise of six inches in the average height of his customers would throw out all his calculations and eat up the modest margin of profit which he now allowed himself.

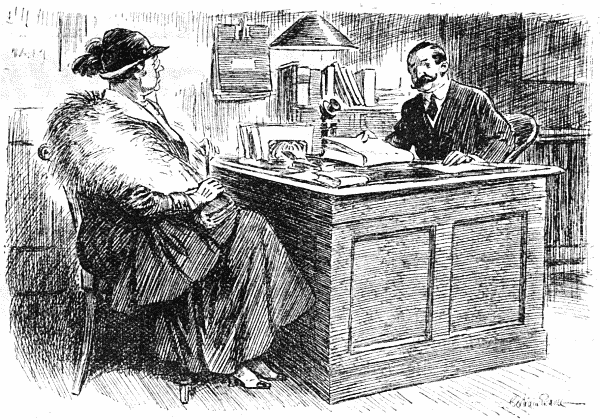

Entente Policeman (to Germany Militant). "ARE YOU GOING TO TAKE THAT STUFF OFF OR MUST I DO IT FOR YOU?"

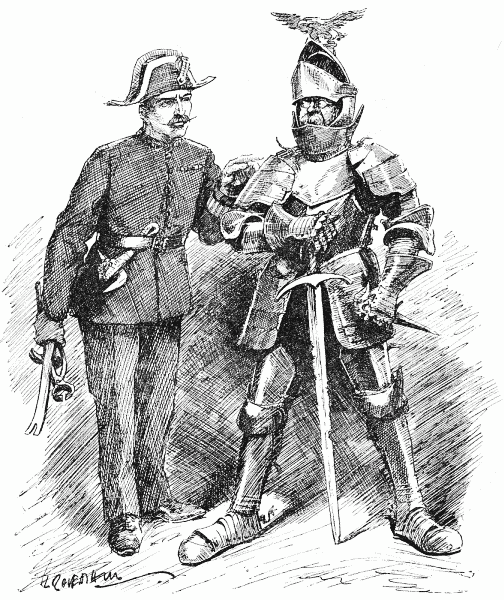

Café Genius. "The fact is we make ourselves too cheap. Of course the public pays to see our pictures, but the blighters can come and see US for nothing."

"The weather of the week has been characteristic of the month. A dawn breaks with a fair sunset."—Scotch Paper.

Of course this happens only very far North.

(According to local legend, Whitby Abbey possesses a ghost which only appears in a blaze of sunshine).

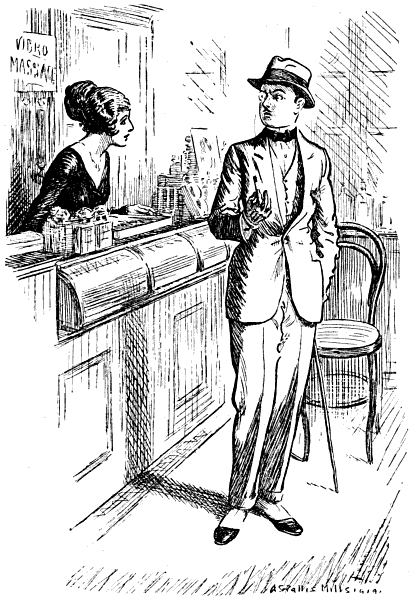

Assistant. "I'm afraid we're right out of moustache brushes, Sir, but that's an eyebrow brush, and it would, I think, serve the purpose."

By Beau Brummel.

The news that the price of lounge suits will have risen to twenty-four pounds by the autumn has created something of a sartorial panic in the City and the West End.

Famous old wardrobes are being broken up on all sides by owners anxious to acquire fresh clothing before it is too late, whilst the small properties thus created find eager tenants amongst those who cannot afford a new outfit at all.

Many tailors who have built new suits are beginning to dispose of them on three or five year repairing leases, and possession of these may sometimes be secured from the present occupiers on payment of a substantial premium.

Gentlemen possessing both town and country sets of suitings are in many cases letting the latter in order to come up to London for the season, whilst others are resorting to various economical artifices to meet the crisis. Plus four golf knickers, let down, make admirable wedding trousers for a short man, and many are the old college blazers dyed black and doing duty as natty pea-jackets.

In the City, of course, fustian and corduroys are almost the only wear, and there is much divergence of opinion on the Stock Exchange as to the best knot for spotted red neckerchiefs and the proper way of tying the difficult little bow beneath the knees.

In Parliament, where of course the old costly fashions have long been out of vogue, the change is equally noticeable. Lord Robert Cecil, for instance, habitually wears the white canvas suit in which Mr. Augustus John painted him; Lord Birkenhead mounts the Woolsack in an old cassock, which, as he points out, not only allows a very scanty attire underneath it, but gives him particular confidence in elucidating St. Matthew; while the Prime Minister himself set off for San Remo in a simple set of striped sackcloth dittos. Many Members are having their old pre-war morning coats turned; Mr. Winston Churchill in machine-gun overalls, Mr. Mallaby-Deeley self-dressed, Sir Edward Carson in a simple union suit, are conspicuous figures, and Mr. Horatio Bottomley by a whimsical yet thrifty fancy often attends the House in the humble attire of the Weaver in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Even in the Welsh collieries it is becoming the habit to go down the pits in rough home-spun, and reserving the top hat, morning coat and check trousers for striking in.

LOOKING FOR A LITTLE HOUSE IN ENGLAND."

Evening Standard.

The gallant General is not the only one who is worn out with this hopeless task.

"Sir John Cadman, head of the British Oil Department, has left Birmingham for San Remo."—Evening Paper.

Was this the last hope of restoring calm to the "troubled waters"?

"He has represented Lowestoft at St. Stephen's—one of the most important fishing centres in the country—for many years past."

Daily Paper.

The House of Commons seems to have been confused with Izaak Walton Heath.

Miss —— played badly and tore up her card as well as many other ladies of note."

Provincial Paper.

But it is hoped that this method of thinning out the competitors will not be generally resorted to.

Speaking at Manchester last night Lord Haldane advocated a great and new national reform by enabling the Universities to train the best teachers of their own level to go out and do extra Mural teaching on a huge scale."

Provincial Paper.

We gather that in our contemporary's opinion it is high time that our Universities recognised "the writing on the wall."

The great auk is but a memory; the bittern booms more rarely in our eastern marshes; and now they tell me Brigadiers are extinct. Handsomest and liveliest of our indigenous fauna, the bright beady eye, the flirt of the trench coat-tail through the undergrowth, the glint of red betwixt the boughs, the sudden piercing pipe—how well I knew them, how often I have lain hidden in thickets and behind hedgerows to study them more closely. How inquisitive the creature was, yet how seldom would it feed from the hand. And now, it seems, they are gone.

Vainly I rack my brains to envisage the manner of their passing. Is there to be nothing left but silence and a shadow or a specimen in a dusty case of glass preserved in creosol and stuffed with lime? Or did not the Brigadiers rather, when they felt their last hour was upon them, retire like the elephants of the jungle to some distant spot and shuffle off the mortal coil in the midst of Salisbury Plain or (for so I still picture it despite the ravages of a rude commercialism) the vast solitude of Slough?

Or it may be that they underwent some classic metamorphosis, translated to a rainless paradise, where they dreamed of battalions for ever inspected and the general salute eternally blown.

"And there, they say, two bright and agéd snakes

Who once were brigadiers of infantry

Bask in the sun."

Anyhow, I cannot believe that ex-Brigadiers die. They only fade away. Fade away, I think, like the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland, leaving at the last not a grin but a scowl behind them. "Brigadiers will fade away," I imagine, ran the instruction from the Army Council, "passing the vanishing point in the following order:—

But oh, how they will be missed, with their insatiable hunger for replies! I remember one in particular, very fierce and black-moustached, who used to pop up suddenly from behind a Loamshire hedge with an enormous note-book in his hand and say to unhappy company commanders, "The situation is so-and-so and so-and-so; now let me hear you give your orders." And the Company-Commander, who would have liked to read through Infantry Training once or twice and then hold a sort of inter-allied conference with his Platoon-Commander, putting the Company Sergeant-Major in the chair, felt that after frightfulness of this kind mere actual war would probably be child's-play. And yet they tell me he was a pleasant enough fellow in the Mess, this Brigadier, and liked good cooking. Now I come to think of it, he faded away before the War came to an end. He faded away into a Major-General.

How different from this sort was the type that could always be placated by a glittering bayonet charge or a thoroughly smart salute! I remember one of this kind who came charging across the landscape, his Staff Captain at his heels, to a point where he saw a friend of mine apparently lost in meditation and sloth. Unfortunately the great man's horse betrayed him as he tried to jump a low hedge, and, when he had clambered up again and arrived in a rather tumbled condition to ask indignantly what had happened to the scouts, "They have established a number of hidden observation posts," my friend replied, keeping his presence of mind, "and are making an exact report of everything that transpires on the enemy's front," and he waved his arm towards the scene of the catastrophe. It was not thought necessary to examine their notes.

In France Brigadiers were mainly divided into the sort that came round the front line themselves, and the sort that sent the Brigade-major or somebody else who had broken out into a frontal inflammation to do it for them. It is difficult to say which genus was the more alarming.

The first was apt to exhibit its contempt for danger by strolling about in perilous places for five minutes and leaving them to be shelled in consequence for a week.

The second sort was apt to issue orders depending for fulfilment on a faulty map reference or a landmark which had been carelessly removed by an H.E. shell. One of the most intransigeant of this kind whom I remember could always, however, be softened by souvenirs; a cast-off Uhlan's lance or the rifle of a Bosch sniper went far to console him for the barrenness of a patrol report. I feel sure he must have faded at Slough.

But it was in battle that their wild appetite for information was most amazingly displayed. At moments when nobody knew where anybody else was or whether the ground underneath him was likely to remain in that sector more than a few moments or be detached and transferred to another, they would send by telephone or by a runner wild messages for an exact résumé of the situation. It was at such times, I think, that some of those eminent war correspondents recently knighted would have done yeoman service in the front line. I can imagine them telephoning somewhat after this manner, in answer to the querulous voice:—

"All hell has broken loose in front of us. The earth shivers as if a volcano is beneath our feet. The pock-marked ridges in the distance are covered with the advancing waves of field-grey forms. Our boys are going up happily shouting and singing to the battle. Sorry, I didn't quite catch what you said about being in touch on the right. The brazen roar of the cannon is mingled with the intermittent rattle of innumerable machine guns. Eh, what? What?"

Yes, I think the Brigadiers would have liked that. But, alas, it could not be. And now they have gone, with their passion for questions, never to return, or never till the next A.C.I. cancels the last.

as Swinburne put it; or

as No. 1 platoon of A Company used to sing. Ah, well.

Evoe.

"In a collision between his vehicle and a tramcar yesterday a passenger was injured and removed to hospital.

For other Sporting News see Page 6."

Irish Paper.

"——'S SIPPING AGENCY, Ltd."

Le Réveil (Beyrouth).

A popular establishment, we feel confident.

PAVLOVITIS.

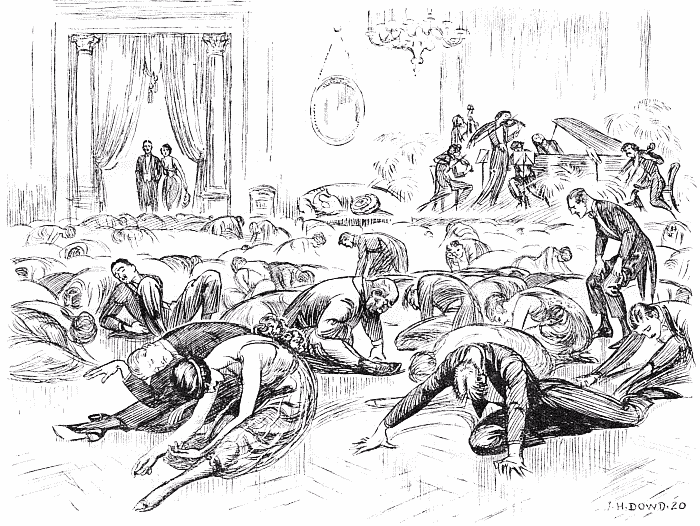

[It is announced that at a coming Charity Ball there will be a dance to the music of Saint-Säens' Le Cygne. Our artist anticipates the moment of the Dying Swan's collapse.]

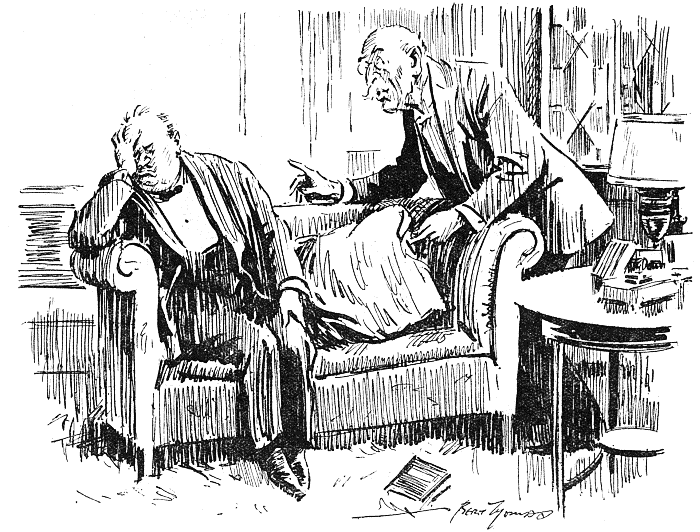

Host (to friend who feels faint.) "Now, what you want is a good stiff glass of"—(suddenly remembering the Budget)—"soda!"

Tea was over, a clearing was made of the articles of more fragile virtue, and Timothy, entering in state, was off-loaded from his nurse's arms into his mother's.

"Isn't he looking sweet to-day?" said Suzanne. "It's really time we had him photographed."

"Why?" I asked.

"Well, why do people as a rule get photographed?"

"That," I said, "is a question I have often asked myself, but without finding a satisfactory answer. What do you propose to do with the copies?"

"There are dozens of people who'll be only too glad to have them. Aunt Caroline, for instance——"

"Aunt Caroline one day took me into her confidence and showed me what she called her scrap-heap. It was a big box full of photographs that had been presented to her from time to time, and she calculated that if she had had them all framed, as their donors had doubtless expected, it would have cost her some hundreds of pounds. While her back was turned I looked through the collection. Your photograph was there—and mine, Suzanne."

"Anyhow, we shall want one to keep ourselves. Think what a pleasure it will be to him when he grows up to see what he looked like as a tiny baby."

I called to mind an ancestral album belonging to my own family that I had carefully kept guarded from Suzanne precisely for the reason that it contained various presentments of myself at early ages in mirth-compelling garments and attitudes; but of course I could not now urge that chamber of horrors in opposition to her demand.

"Besides," she went on, "we needn't buy any copies at all if we don't like them. Snapper and Klick are continually worrying me to have Baby taken. Once a week regularly, ever since the announcement of his birth appeared, they've rung me up to ask when he will give them a sitting. Sometimes it's Snapper and sometimes it's Klick; I don't know which is which, but one of them has adenoids. We can't do any harm by taking him there, because they say in their circulars they present two copies free and there's no obligation to purchase any."

"I wonder how they make that pay?"

"Oh," said Suzanne, "they keep the copyright, you know, and then when he does anything famous they send it round to the illustrated papers, which pay them no end of money for permission to reproduce it."

"But by the time he does anything famous," I objected, "won't this photograph be a trifle out of date? Supposing, for instance, in twenty or thirty years' time he marries a Movie Queen——"

Just then the telephone-bell rang, and Suzanne, as is her wont, rushed to[Pg 328] answer it, dropping Timothy into my arms on the way.

"Hello!" I heard her say. "Yes; speaking. Yes, I was just going to write. Yes; that will do quite well. What? Yes, about eleven. Good-bye."

"Not another appointment with the dressmaker?" I inquired.

"No. Curiously enough it was Klick again—or Snapper—and his adenoids are worse than ever; I suppose it's the damp weather gets into them. So I said we'd take Baby to-morrow."

"I don't quite see the connection," I said. "Besides, aren't they catching?"

"Now you're being funny again. Save that up for to-morrow."

"What do you mean?" I asked in some alarm. "And why did you say we'd take Baby?"

"Why, of course you've got to come too. You can always make him laugh better than anyone else; it's your métier. And I do want his delicious little dimples to come out."

"Do I understand that I'm to go through my répertoire in cold blood and under the unsympathetic gaze of Messrs. Snapper and Klick? Suzanne, it can't be done."

"Oh, nonsense! You've only got to sing Pop Goes the Weasel in a falsetto voice and make one of those comic faces you do so well, and he'll gurgle at once. Well, that's settled. We start at half-past ten to-morrow."

The coming ordeal so preyed upon my mind that I spent a most restless night, during which, so Suzanne afterwards told me, I announced at frequent intervals the popping of the weasel. The day dawned with a steady drizzle of rain, and, after a poor attempt at breakfast, I scoured the neighbourhood for a taxi. Having at last run one to earth, I packed the expedition into it—Suzanne, Timothy, Timothy's nurse and Barbara (who begged so hard to be allowed to "come and see Father make faces at Baby" that Suzanne weakly consented).

Arrived at our destination, Suzanne bade the driver wait. "We shall never find another cab to take us home in this downpour," she said, "and we shan't be kept long."

We were ushered into the studio by a gentleman I now know to have been Mr. Klick. He aroused my distrust at once by the fact that he did not wear a velvet coat, and I pointed out this artistic deficiency in a whisper to Suzanne.

"Never mind," she whispered back; "we needn't buy any if they're not good."

Timothy, who had by now been put straight by his attendant, was carefully placed on all-fours on a pile of cushions, which he promptly proceeded to chew. Mr. Klick, on attempting to correct the pose, was received with a hymn of hate that compelled him to bury his head hastily in the camera-cloth, and Suzanne arranged the subject so that some of his more recognisable features became visible.

"Now then," she said to me, "make him smile."

With a furtive glance at Mr. Klick, who fortunately was still playing the ostrich, I essayed a well-tried "face" that had almost invariably evoked a chuckle from Timothy, even when visitors were present. On this occasion, however, it failed to produce anything more than a woebegone pucker that foreshadowed something worse. Hastily I switched off into another expression, but with no better result.

"Go on, Father," encouraged Bar[Pg 329]bara, who had been taking a breathless interest in these proceedings; "try your funny voice."

Mr. Klick had emerged from cover and was standing expectantly with his hand on the cap.

Dear reader, have you ever been called upon to sing Pop Goes the Weasel in a falsetto voice before a fractious baby, a small but intensely critical child, a stolidly contemptuous nurse, an agitated mother and a gaping photographer, with the knowledge that success or failure hangs upon your lips, and that all the time a diabolical machine in the street below is scoring threepence against you every minute or so? Of course you haven't; but possibly you may be able to enter into my feelings in this hour of trial. With a prickly heat suffusing my whole body and a melting sensation at the collar I struggled through the wretched lyric once. Timothy regarded me first with scorn and then with positive distaste. In desperation I squeaked it out again and yet again, but each succeeding "pop" only registered another scowl on the face of my offspring and another threepence on that of the cabman's clock.

I was maddened now, and Suzanne sought to restrain me; but I shook her off violently and went on again da capo, and was just giving vent for about the seventeenth time to a particularly excruciating "pop" when the door of the studio opened and a benevolent-looking old gentleman entered. He gazed at us all in wonderment, and, overcome by mingled shame and exhaustion, I sank into a chair and popped no more.

"Ah, Mr. Snapper," said Mr. Klick, "we were just trying to get this young gentleman amused."

Mr. Snapper, who, I should imagine, was the adenoid victim, looked first at me and next at Timothy, and then blew his nose vigorously. It was not an ordinary blast, but had a peculiarly musical timbre, very much like the note of a mouth-organ. It certainly attracted Timothy's attention, for he at once looked round and the glimmer of a smile appeared upon his tear-stained face.

"That's it!" cried Barbara excitedly. "Do it again."

"Oh, please do," entreated Suzanne.

Mr. Snapper, adenoids or no adenoids, was a sportsman. He quickly understood what was required of him and blew his nose again and again. And with each blow Timothy's smile became wider, the dimples grew deeper, and Mr. Klick at the camera was pushing in and pulling out plates for all he was worth. At last Mr. Snapper could blow no more, and with profuse thanks we gathered ourselves, together and departed. On our arrival home the cabman, fortunately, was induced to accept a cheque in payment.

The photographs have turned out a great success. One in particular, which shows the first smile breaking through Timothy's tears, is of a very happy character, and Mr. Snapper has asked and received permission to send it to the illustrated Press under the title, "Sunshine and Shower"; and Aunt Caroline has not only been given a copy, but has had it framed.

Now, when I am called upon to produce a laugh from Timothy, I no longer make faces or "pop." I have discovered how to blow my nose like a mouth-organ. It's trying work, but the effect is magical.

Redintegratio Amoris.

"The Public is hereby notified that myself and my Wife Millicent —— is together again. I got hasty and advertised her with no just cause. Fitz ——."—West Indian Paper.

"This telegram had been preceded by others, which were, unfortunately, contrary to instructions at the Post Office, delivered at this office, which was closed, and, therefore, not opened."—Irish Paper.

That, of course, would be so.

"At a meeting of the Child Study Society on Thursday, April 29th, at 6 p.m., Sir A. E. Shipley, G.B.E., D.Sc., F.R.S., will give a lecture, illustrated by lantern slides, on biting insects and children."

British Medical Journal.

And we had always thought him such a kind man!

Gloomy Artist. "Yes, I gave her all my last year's sketches for her jumble-sale in the East-End. Told her to get rid of them for anything she liked—half-a-crown or a couple of bob——" (Pauses for exclamations of horror at the sacrifice.)

Friend. "And did they sell?"

(Being the scenario of a modern doggerel Epic.)

ONE PROPOSES KNEELING OUTSIDE HOUSE OF COMMONS."

"Star" Headlines.

We have read the article carefully, but the Member to whom this Leap-Year proposal was made is not mentioned.

Monday, April 19th.—Primrose day in the House of Commons was more honoured in the breach than the observance. Barely a dozen Members sported Lord Beaconfield's favourite flower (for salads), and one of them found himself so uncomfortably conspicuous that shortly after the proceedings opened he furtively transferred his buttonhole to his coat-pocket. Among those who remained faithful were Lord Lambourne (in the Peers' Gallery), who had for this occasion substituted a posy of primroses for his usual picotee, and, quaintly enough, Mr. Hogge, who had not hitherto been suspected of Disraelian sympathies.

"Mr. Hogge had not hitherto been suspected of Disraelian sympathies."

For a Budget-day the attendance was smaller than usual. But it was large enough to prevent Mr. Billing from securing his usual seat. The Speaker, however, did not smile upon his suggestion that he should occupy one of the vacant places on the Front Opposition Bench, and curtly informed him that there was plenty of room in the Gallery. Thither Mr. Billing betook himself, and thence he addressed a question which Mr. Hope, the Minister concerned, was unable to catch, his ears not being attuned to sounds from that altitude.

Otherwise Question-time was chiefly remarkable for the loud and continued burst of cheering from the Coalition benches which greeted Mr. Will Thorne's suggestion (à propos of Lenin's industrial conscription) that "it would be a very good thing to make all the idlers in this country work." Mr. Thorne seemed quite embarrassed by the popularity of his proposal, which did not, however, appear to arouse the same enthusiasm among his colleagues of the Labour Party.

It was four o'clock when Mr. Chamberlain rose to "open the Budget" (he clings to that old-fashioned phrase), and just after six when he completed a speech which Mr. Asquith (himself an ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer) justly praised for its lucidity and comprehensiveness.

Mr. Chamberlain could not on this occasion congratulate himself (as his predecessors were wont to do) on the accuracy of his forecasts. He had two shots last year, in Spring and Autumn, but both times was many millions out in his calculations. Fortunately all the mistakes were on the right side, and he came out with a surplus of one hundred and sixty-four millions (about as much as the whole revenue of the country when first he went to the Exchequer) to devote to the redemption of debt.

But that did not content him. For an hour by the clock he piled up the burdens on the taxpayer. His arguments were not always consistent. It is not quite easy to see why, because ladies have taken to smoking cigarettes, an extra heavy duty should be imposed on imported cigars; or how the appearance of "a new class of champagne-drinkers" justifies a further tax upon the humble consumer of "dinner-claret."

Nor is it easy to follow the process of reasoning by which the Chancellor convinced himself that the Excess Profits Tax, which last year he described as a great deterrent to enterprise and industry, only, justifiable as "a temporary measure," should now be not merely continued but increased by fifty per cent.

Mr. Chamberlain. "I don't care what anybody says about this blooming tree (I use the epithet in its literal sense); I shall let it keep on for another year."

This proposal seemed to excite more hostility than any other. But the single taxers were annoyed by the final disappearance of the Land Values Duties (the only original feature of Mr. Lloyd George's epoch-making first Budget). Mr. Raffan pictured their author being dragged at the Tory chariot-wheels, and Dr. Murray observed that the land-taxes were evidently not allowed "on the other side of the Rubicon."

The general view was that the Government had shown courage in imposing fresh taxation, but would have saved themselves and the country a great deal of trouble if they had been equally bold in reducing expenditure.

Tuesday, April 20th.—When a local band at Cologne recently played the "Wacht am Rhein" the British officers present stood up, on the ground (as they explained to a surprised German) that they were now the Watch on the Rhine. But are they? According to Colonel Burn the Army of the Rhine is now so short of men that it is compelled to employ German civilians as batmen, clerks and even telephone-operators; and Mr. Churchill was fain to admit that it would not surprise him to hear that "some assistance has been derived from the local population."

The Carnarvonshire police are peeved because they are not allowed to belong to any secret society except the Freemasons, and consequently are debarred from membership of the Royal Ante-diluvian Order of Buffaloes. Mr. Shortt disclaimed responsibility, but it is expected that the Member for the Carnarvon Boroughs, who is notoriously sympathetic to Ante-diluvians (is not his motto Après moi le déluge?), will take up the matter on his return from San Remo.

Having had time to consider the Budget proposals in detail Mr. Asquith was less complimentary and more critical. Good-humoured chaff of the Prime Minister on the demise of the Land Values Duties before they had yielded the "rare and refreshing fruits" promised ten years ago, was followed by a reasoned condemnation of the proposed increase in the wine duties, which he believed would diminish consumption and cause international complications with our Allies. The Chancellor, again, had thought too much of revenue and too little of economy. He urged him—in a magnificent mixture of[Pg 334] metaphors—to cut away those parasitic excrescences upon the normal administrative system of the country which now constituted an open tap.

Wednesday, April 21st.—The abolition of the Guide-lecturer at Kew Gardens was deplored by Lord Sudeley and other Peers. But as, according to Lord Lee, out of a million visitors last year only five hundred listened to the Guide—an average of less than three per lecture—the Government can hardly be blamed for saving a hundred pounds. Retrenchment, after all, must begin somewhere.

Sir Donald Maclean cannot have heard of this signal example of Government economy or he would not have denounced Ministers so vehemently for their extravagance. His most specific charge was that in Mesopotamia they were "spending money like water in looking for oil."

In a further defence of the Budget proposals Mr. Chamberlain disclaimed the notion that it was the duty of the Chancellor of the Exchequer to denounce in the House the Estimates which he had approved in Cabinet. His business was to find the money. Circumstances had altered his attitude to the Excess Profits Duty, and he was now determined to stick to it. Did not a cynic once say that nothing succeeds like excess?

Mr. Barnes, who was loudly cheered on his return to the House, joined in the cry for economy. "Some departments," he declared, "existed only because they had existed."

The country clergy are without doubt the most over-rated persons in the country—I mean, of course, from a fiscal point of view. Consequently the House gave a friendly reception to a Bill intended to relieve them of some of their pecuniary burdens.

"If, as appears to be the case, it is for the moment more or less decently interred, its epitaph should be not Reguiescat but Resurget" (cheers).

Mr. Asquith on the Land Values Duties.

Thursday, April 22nd.—When Dr. Macnamara was Secretary to the Admiralty no Minister was clearer or more direct in his answers. Now that he has become Minister he has laid aside his quarter-deck manner and adopted tones of whispering humbleness which hardly reach the Press Gallery.

He ought to take example fro Mr. Stanton, who never leaves the House in doubt as to what he means. This afternoon, his purpose was to announce that a certain "Trio" on the Opposition Benches was in league with the forces of disorder. "Bolshies!" he shouted in a voice that frightened the pigeons in Palace Yard.

Later in the evening Mr. Stanton indicated that unless the salaries of Members of Parliament were raised he should have seriously to consider the question of returning to his old trade of a coal-hewer, at which I gathered he could make much more money with an infinitely smaller exertion of lung-power.

The vote for Agriculture and Fisheries was supported by Sir A. Griffith-Boscawen in a speech crammed full of miscellaneous information. We learned that the Minister once smoked a pipe of Irish tobacco, and said "Never Again"; that the slipper-limpet, formerly the terror of the oyster-beds had now by the ingenuity of his Department been transformed into a valuable source of poultry-food, and that the roundabout process by which the Germans in bygone days imported eel-fry from the Severn for their own rivers, and then exported the full-grown fish for the delectation of East-end dinner-tables, had been done away with. In the matter of eels this country is now self-supporting.

"The stock markets showed a good deal of uncertainty this morning and dealers marked prices lower in many cases to protect themselves against possible sales on the Budget proposals, particularly the excess profits duty and the corruption tax."—Provincial Paper.

Mr. Chamberlain omitted to mention the last-named impost, but no doubt that was his artfulness.

"The Bear-Garden."

The authors of the guide-books have signally failed to discover the really interesting parts of Law-land. I have looked through several of these works and not one of them refers, for example, to the "Bear-Garden," which is the place where the preliminary skirmishes of litigation are carried out. The Bear-Garden is the name given to it by the legal profession, so I am quite in order in using the title. In fact, if you want to get to it, you have to use that title. The proper title would be something like "the place where Masters in Chambers function at half-past one;" but, if you go into the Law Courts and ask one of the attendants where that is, he will say, rather pityingly, "Do you mean the Bear-Garden?" and you will know at once that you have lost caste. Caste is a thing you should be very careful of in these days, so the best thing is to ask for the Bear-Garden straightaway.

It is in the purlieus of the Law Courts and very hard to find. It is up a lot of very dingy back-staircases and down a lot of very dingy passages. The Law Courts are like all our public buildings. The parts where the public is allowed to go are fairly respectable, if not beautiful, but the purlieus and the basements and the upper floors are scenes of unimaginable dinginess and decay. The Law Courts' purlieus are worse than the Houses of Parliament's purlieus, and it seems to me that even more disgraceful things are done in them. It only shows you the danger of Nationalisation.

On the way to the Bear-Garden you pass the King's Remembrancer's This is the man who reminds His Majesty about people's birthdays; and in a large family like that he must be kept busy. Not far from the King's Remembrancer there is a Commissioner for Oaths; you can go into his room and have a really good swear for about half-a-crown. This is cheaper than having it in the street—that is, if you are a gentleman; for by the Profane Oaths Act, 1745, swearing and cursing are punishable by a fine of one shilling for every day-labourer, soldier or seaman; two shillings for every other person under the degree of a gentleman; and five shillings for every person of or above the degree of a gentleman. This is not generally known. The Commissioner of Oaths is a very broad-minded man, and there is literally no limit to what you may swear before him. The[Pg 335] only thing is that he insists on your filing it before you actually say it. This may cause delay; so that if you are feeling particularly strongly about anything it is probably better to have it out in the street and risk being taken for a gentleman.

There are a number of other interesting functionaries on the way to the Bear-Garden; but we must get on. When you have wandered about in the purlieus for a long time you will hear a tremendous noise, a sort of combined snarling and roaring and legal conversation. When you hear that, you will know that you are very near the bears. They are all snarling and roaring in a large preliminary arena, where the bears prepare themselves for the struggle; all round it are smaller cages or arenæ, where the struggles take place. If possible you ought to go early, so that you can watch the animals massing. Lawyers, as I have had occasion to observe before, are the most long-suffering profession in the country, and the things they do in the Bear-Garden they have to do in the luncheon-hour, or rather in the luncheon half-hour, between half-past one and two.

This accounts perhaps for the extreme frenzy of the proceedings. They hurry in a frenzy up the back-stairs about 1.25, and they pace up and down in a frenzy till half-past one. There are all sorts of bears, most of them rather seedy old bears, with shaggy and unkempt coats. These are solicitors' clerks, and they all come straight out of Dickens. They have shiny little private-school handbags, each inherited, no doubt, through a long line of ancestral solicitors' clerks; and they all have the draggled sort of moustache that tells you when it is going to rain. While they are pacing up and down the arena they all try to get rid of these moustaches by pulling violently at alternate ends; but the only result is to make it look more like rain than ever.

Some of the bears are robust old bears, with well-kept coats and loud roars; these are solicitors' clerks too, only better fed; or else they are real solicitors. And a few of the bears are perky young creatures—in barrister's robes, either for the first time, when they look very self-conscious, or for the second time, when they look very self-confident. All the bears are telling each other about their cases. They are saying, "We are a deceased wife's sister suing in forma pauperis," or "I am a discharged bankrupt, three times convicted of perjury, but I am claiming damages under the Diseases of Pigs Act, 1862," or "You are the crew of a merchant-ship and we are the editor of a newspaper." Just at first it is rather disturbing to hear snatches of conversation like that, but there is no real cause for alarm; they are only identifying themselves with the interests of their clients; and, when one realises that, one is rather touched.

At long last one of the keepers at the entrance to the small cages begins to shout very loudly. It is not at all clear what he is shouting, but apparently it is the pet-names of the bears, for there is a wild rush for the various cages. Across the middle of the cage a stout barricade has been erected, and behind the barricade sits the Master, pale but defiant. Masters in Chambers are barristers who have not got proper legal faces, and have had to give up being ordinary barristers on that account; in the obscurity and excitement[Pg 336] of the Bear-Garden nobody notices that their faces are all wrong. The two chief bears rush at the Master and the other bears jostle round them, egging them on. When they see that they cannot get at the Master they begin snarling. One of them snarls quietly out of a long document about the Statement of Claim. He throws a copy of this at the Master, and the Master tries to get the hang of it while the bear is snarling; but the other bear is by now beside himself with rage, and he begins putting in what are called interlocutory snarls, so that the Master gets terribly confused, though he doesn't let on.

By-and-by all pretence of formality and order is put aside and the battle really begins. At this stage of the proceedings the rule is that no fewer than two of the protagonists must be roaring at the same time, of which one must be the Master. But the more general practice is for all three of them to roar at the same time. Sometimes, it is true, by sheer roar-power the Master succeeds in silencing one of the bears for a moment, but he can never be said to succeed in cowing a bear. If anybody is cowed it is the Master. Meanwhile the lesser bears press closer and closer, pulling at the damp ends of their rainy moustaches and making whispered suggestions for new devilries in the ears of the chief bears, who nod their heads emphatically but don't pay any attention.

The final stage is the stage of physical violence, when the chief bears lean over the barricade and shake their paws at the Master; they think they are only making legal gestures, but the Master knows very well that they are getting out of hand; he knows then that it is time he threw them a bun. So he says a soothing word to each of them and runs his pen savagely through almost everything on their papers. The bears growl in stupefaction and rage, and take deep breaths to begin again. But meanwhile the keeper has shouted for a fresh set of bears, who surge wildly into the room. The old bears are swept aside and creep out, grunting. What the result of it all is I don't know. Nobody knows. But the new bears——

[Editor.—I am much bored with this.

Author.—Oh, very well.]

A. P. H.

Mistress. "At two o'clock this morning, Mary, we were wakened by loud knocking, and your master went down and found it was a policeman, who told him the pantry window was open."

Mary. "Oh, 'e did, did 'e? 'Ad 'e red 'air? I'll larn 'm to go 'ammerin' at decent people's door in the middle of the night just because I wouldn't go to the pictures with 'im last Friday. Imperence!"

From the directions on an omnibus ticket:—

"Passengers are requested not to stand on top of the Bus back seats for smoking."

This is a thing we never do.

"Mary Rose."

Of course nobody could possibly suspect Sir James Barrie of plagiarising (save from himself), yet it will explain something of the atmosphere of Mary Rose if I say that it is a story with such a theme as that admirable ghostmonger, the Provost of Eton, would whole-heartedly approve—thrilling, sinister, inconclusive—with (shall I say?) just a dash of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in his other-worldly mood to bring it well into the movement. Naturally the variations are sheer Barrie and of the most adroit.

THE BOY WHO WOULD GROW UP FASTER THAN HIS MOTHER.

Mary Rose . . . Miss Fay

Compton.

Harry . . . . Mr. Robert Loraine.

Mary Rose is in fact a girl who couldn't grow up, because whenever she visited a little mystery island in the Outer Hebrides "they" who lived in a "lovely, lovely, lovely" vague world beyond these voices would call her vaguely (to Mr. Norman O'Neill's charming music), and she would as vaguely return with no memory of what had passed and no change in her physical condition. This didn't matter so much when, as a mere child, she disappeared for thirty days; but when, mother of an incomparable heir of two, she was rapt away in the middle of a picnic for twenty-five years, and returned to find a husband, mother and father inexplicably old and changed, and dreadfully silent about her babe—well, you see for yourself how hopeless everything was. As if there were not enough real tragedy in the world and it were necessary to invent!

I don't think it fair to tell you any more. You shouldn't suffer these thrills at second-hand. But I can say that, in spite of making it a point of professional honour to try to keep a warm spine and check the unbidden tear from trickling down my nose (which makes you look such an ass before a cynical colleague during the intervals), I was beaten in both attempts. The "effects" were astonishingly well contrived by both author and producer (Mr. Holman Clark). You were not let down at the supreme moment by a hurried shuffle of dimly seen forms or the click of an electrician's gear suggesting too solid flesh. The house was in a queer way stunned by the poignancy of the last scene between the young ghost-mother and the long-sought unrecognised son, and had to shake itself before it could reward with due applause the fine playing of as perfect a cast as I have seen for a long time. There's no manner of doubt that Sir James "got it over" (as they say) all right.

Miss Fay Compton makes astonishing strides. Her Mary Rose had adorable shy movements, caresses, intonations, wistfulnesses. These were traits of Mary Rose, not tricks of Miss Compton. And they escaped monotony—supreme achievement in the difficult circumstances. Mr. Robert Loraine in the doubled rôles of Mary Rose's husband and son, showed a very fine skill in his differentiation of the husband's character in three phases of time and development, and of the son's, with its family likeness and individual variation. Mr. Ernest Thesiger, who seems to touch nothing he does not adorn, gave a fine rendering of as charming a character as ever came out of the Barrie box—the superstitious, learned, courteous crofter's son, student of Aberdeen University, temporary boatman and (later) minister. He did his best incidentally, by rowing away without casting off, to corroborate the local legend that the queer little island sometimes disappeared. Miss Mary Jerrold was just the perfect Barrie mother (of Mary Rose). Mr. Arthur Whitby's parson, Mr. Norman Forbes' squire, Miss Jean Cadell's housekeeper, left no chinks in their armour for a critic's spleenful arrow.

T.

"It was one of those perfect June nights that so seldom occur except in August."

—— Magazine.

The result of Daylight-saving, no doubt.

In the belief that the numerous signs and notices, such as those containing warnings and advice to the public, with which the eye is so familiar, might be employed as suitable media for commercial advertisement, the following suggestions are offered for what they are worth:—

"CHARLES ——

This week, Driven From Home.

Next week, At Sea."Daily Paper.

Surely this pitiable case ought to be brought to the attention of the Actors' Benevolent Association.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

I have a mild grievance against that talented lady, Miss Marjorie Bowen, for labelling her latest novel "a romantic fantasy." Because, like all her other stories, The Cheats (Collins) moves with such an air of truth, its personages are so human, that I could delightfully persuade myself that it was all true, and that I had really shared, with a sometimes quickened pulse, the strange fortunes of the sombre young hero. But—fantasy! That is to show the strings and give away the whole game. However, if you can forget that, the coils of an admirably woven intrigue will grip your attention and sympathy throughout. The central figure is one Jaques, who comes to town as a penniless and love-lorn romantic, to be confronted with the revelation that he is himself the eldest son, unacknowledged but legitimate, of His Majesty King Charles the Second, then holding Court at Whitehall. It is from the plots and counter-plots, the machinations and subterfuges that follow that Miss Bowen justifies her title. Certainly The Cheats establishes her in my mind as our first writer of historical fiction. The character-drawing is admirable (especially of poor weak-willed vacillating Jaques, a wonderfully observed study of the Stuart temperament). More than ever, also, Miss Bowen might here be said to write her descriptions with a paint-brush; the whole tale goes by in a series of glowing pictures, most richly coloured. The Cheats is not a merry book; its treatment of the foolish heroine in particular abates nothing of grim justice; but of its art there can be no two opinions. I wish again that I had been allowed to believe in it.

It must be unusual in war for a commander-in-chief to be regarded by his opponents with the respect and admiration that the British forces in East Africa felt towards Von Lettow-Vorbeck; from General Smuts, who congratulated him on his Order "Pour le Mérite," down to the British Tommy who promised to salute him "if ever 'e's copped." The fact that Von Lettow held out from August, 1914, till after the Armistice with a small force mainly composed of native askaris, and with hardly any assistance from overseas, is proof in itself of his organizing ability, his military leadership and his indomitable determination. As these are qualities which are valued by his late enemies his story of the campaign, My Reminiscences of East Africa (Hurst and Blackett), should appeal to a large public, especially as it is written on the whole in a sporting spirit and not without some sense of humour. His descriptions of the natural difficulties of the country and the methods he adopted for handling them are interesting and instructive. But in military matters his story is not altogether convincing; for if his "victories" were as "decisive" as he represents them how is it that they were followed almost invariably by retirement? The results are attributed in these pages to "slight mischances" or "unfavourable conditions" or merely to "pressure of circumstances." Would it not have been better, while he was about it, to claim boldly that he was luring us on? This is a question on which one naturally refers to the maps, and it is therefore all the more regrettable that these contain no scale of mileage, an omission which renders them almost meaningless. How many readers, for instance, will realise that German East Africa was almost twice the size of Germany? The translation on the whole is good,[Pg 340] though some phrases such as "the at times barely sufficient ration" are rather too redolent of the Fatherland.

I see that on the title-page of his latest story Mr. W. E. Norris is credited with having already written two others (specified by name), etc. Much virtue in that "etc." I cannot therefore regard The Triumphs of Sara (Hutchinson) precisely as the work of a beginner, though it has a freshness and sense of enjoyment about it that might well belong to a first book rather than to—I doubt whether even Mr. Norris himself could say offhand what its number is. Sara and her circle are eminently characteristic of their creator. You have here the same well-bred well-to-do persons, pleasantly true to their decorous type, retaining always, despite modernity of clothes and circumstance, a gentle aroma of late Victorianism. Perhaps Sara is the most immediate of Mr.Norris's heroines so far. Her money-bags had been filled in Manchester, and from time to time in her history you are reminded of this circumstance. It explains much; though hardly her marriage with Euan Leppington, whose attraction apparently lay in being one of the few males of her acquaintance whom Sara did not find it fatally easy to bring to heel. Anyhow, after marriage she quickly grew bored to death of him; so much so that it required an attempt (badly bungled) by another woman to get Euan to elope with her, and a providential collapse of the very unwilling Lothario, to bring about that happy ending that my experience of kind Mr. Norris has taught me to expect. I may add that he has never done anything more quietly entertaining than the frustrated elopement; the luncheon scene at the Métropole, Brighton, between the angry but amused Sara and a husband incapacitated by rage, remorse and chill, is an especially well-handled little comedy of manners.

Sir Julian Corbett, in writing the first volume of Naval Operations (Longmans), has carried the semi-official history of the War at sea only as far as the Battle of the Falklands; but if the other three or four volumes—the number is still uncertain—are to be as full of romance as this the complete work will be a library of adventure in itself. Hardly ever turning aside to praise or blame, he says with almost unqualified baldness a multitude of astounding things—things we half knew, or guessed, or longed to have explained, or dared not whisper, or, most of all, never dreamt of. Here is a gold-mine for the makers of boys' books of all future generations to quarry in. Think, for instance, of the liner Ortega shaking off a German cruiser by bolting into an uncharted tide-race near the Horn; or the Southport, left for disabled by her captors, crawling two thousand miles to safety with only half an engine; or the triumphant raider Karlsruhe, her pursuers baffled, full to the hatches with captured luxuries, bands playing, flags flying, suddenly blown up in mid-Atlantic. The game of hide-and-seek, as played by the Emden and her like, naturally figures very largely in a volume which Henty could hardly have bettered. The author's veracious narrative, leaving all picturesque detail to the imagination, gets home every time by the sheer weight of its material. The War in Home waters is no less fascinatingly reconstructed, and the case of maps contains in itself living epics for all who study them with understanding.

In writing her second book Miss Hilda M. Sharp has allowed herself what is, I suspect, the lady novelist's greatest treat, the extraordinary achievement of using the first person singular and making it masculine. She has done it very well too, and I am happy to recall that, in another place, I was among the many who prophesied good concerning her future when she made her début as a novelist with The Stars in their Courses in Mr. Fisher Unwin's "First Novel Library." A Pawn in Pawn comes very properly from the same publisher. It has one of those plots which it is most particularly a reviewer's business, in the reader's own interest, not to reveal, but it is permissible to explain that the "pawn" of the title is a little girl adopted from an orphanage, where, as someone says, "the orphans aren't really orphans," by Julian Tarrant, whom a select circle acknowledged as the greatest poet that the last years of the nineteenth century produced. Miss Sharp earns my special admiration by getting through the inevitable description of the beginning of the Great War in fewer words than anybody whose attempt I have yet encountered, and steers throughout a pleasant course midway between a "bestseller" and a "high-brow." Lydia, the "pawn," is very charming, but quite possibly so, and though, of course, she must marry one of the three men interested in her adoption Miss Sharp will probably keep most of her readers, as she did me, in doubt as to which it is to be until quite the end of the book. I think that he may prove an acquired taste with most readers; but directly I found that he was apt to quote the reviews in Punch I realised that he was a man of discrimination and deserved his good luck.

"Proper fed up wiv you, I am. Cry, cry, cry all day long. I'd 'it yer over the 'ead wiv the bottle if I wos a modern woman."

"—— Co-Operative Society, Ltd.

Members are requested to hand in their Share Pass Books for Audit Purposes to the Head Office on or before at once."—Local Paper.

"Rev. —— writes:—'I have a Cousin residing in the Transvaal who has been living on three plates of porridge made of —— for five years, and is well and strong on it.'"—South African Paper.

It sounds very sustaining.

Transcriber's Notes:

Some illustrations have been

moved from the physical page order to facilitate text formatting for

this ebook.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume

158, April 28, 1920, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, VOL. 158, APRIL 28, 1920 ***

***** This file should be named 22653-h.htm or 22653-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/2/2/6/5/22653/

Produced by V. L. Simpson, Jonathan Ingram and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,