The Project Gutenberg EBook of Anecdotes of the Habits and Instinct of Animals, by R. Lee This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Anecdotes of the Habits and Instinct of Animals Author: R. Lee Illustrator: Harrison Weir Release Date: June 30, 2007 [EBook #21973] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HABITS AND INSTINCT OF ANIMALS *** Produced by David Edwards, Marcia Brooks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The University of Florida, The Internet Archive/Children's Library)

In making a selection of anecdotes, those have been assembled which were supplied by me to other works, and in most instances have received considerable amplification; others have been given which never before were printed—perhaps not even written; while all which have been transferred from other pages to mine have received the stamp of authenticity. Besides those whose names are already mentioned, I have to thank several friends who have drawn from their private stores for my advantage, and thus enabled me to offer much that is perfectly new.

Dry details of science and classification have been laid aside, but a certain order has been kept to avoid confusion; and, although endeavours have been made to throw as much interest as possible over these recorded habits and actions of the brute creation; I love the latter too well to raise a doubt by one word of embellishment, even if I did not abstain from principle.

The intentions with which this work was commenced have not been carried out, inasmuch as materials have crowded upon me beyond all calculation; and, although a large portion has been rejected, the anecdotes related go no farther than the Mammalia, while almost all animals were to have been included.

With regard to the remaining orders—if the present work should meet with a favourable reception, I shall hope next year to present the public with touching and amusing proofs of the sagacity and dispositions of birds, and of "hair-breadth scapes" from reptiles, etc., some of which will, like those in the present volume, be carefully selected from the works of travellers, from the resources of friends, and from my own experience.

To the pleasing task of enlightening those, who, shut up in close cities, have no opportunity of observing for themselves, and to the still higher enjoyment of directing young minds to an elevating pursuit, the naturalist adds a gratification even better than all, by making known the hidden wonders of nature; and leaving to those who delight in argument, the ever unsolved question of where instinct ends and reason begins, he sets forth the love of the great Creator towards all His creatures, and the ways He takes to show His wisdom.

Formed like man, and practicing similar gestures, but with thumbs instead of great toes upon their feet, and with so narrow a heel-bone, that even those who constantly walk upright have not the firm and dignified step of human beings; the Quadrumana yet approximate so closely to us, that they demand the first place in a book devoted principally to the intellectual (whether it be reason or instinct) history of animals. This approximation is a matter of amusement to some; but to the larger portion of mankind, I should say, it is a source of disgust. "Rapoynda," I exclaimed, one day, to a troublesome, inquisitive, restless negro, pointing to a black monkey, which much resembled him in character, "that is your brother." Never shall I forget the malignant scowl which passed over the man's features[Pg 2] at my heedless comparison. No apology, no kindness, not even the gift of a smart waistcoat, which he greatly coveted, ever restored me to his good graces; and I was not sorry when his Chief summoned him from my vicinity, for I dreaded his revenge.

A few years after, I stood lost in admiration before Sir Edwin Landseer's inimitable picture of "the monkey who had seen the world," in which nature and truth lend their tone and force to the highest efforts of art; when a voice exclaimed, "How can you waste your time looking at that thing; such creatures ought never to have been painted;" and although the speaker was a religious man, he muttered to himself, "I am not sure they ought ever to have been made." The voice proceeded from one of the finest instances of manly beauty; one famed also for talent and acquirement. Rapoynda started into my recollection; and as I slowly left the talented picture, I could not help smiling at the common feeling between the savage and the gentleman, thereby proving its universality.

Never did any one start for a tropical climate with a greater antipathy towards these "wild men" than I did; I lived years in their vicinity and yet contrived to avoid all contact with them, and it was not till I was homeward-bound that my conversion was effected. The ship in which Mr. Bowdich and myself took a round-about course to[Pg 3] England, was floating on a wide expanse of water, disturbed only by the heavy swell, which forms the sole motion in a calm; the watch on deck were seated near the bows of the vessel, the passengers and officers were almost all below, there was only myself and the helmsman on the after-deck; he stood listlessly by the binnacle, and I was wholly occupied in reading. A noise between a squeak and a chatter suddenly met my ears; and before I could turn my head to see whence it proceeded, a heavy, living creature jumped on to my shoulders from behind, and its tail encircled my throat. I felt it was Jack, the cook's monkey; the mischievous, malicious, mocking, but inimitable Jack, whose pranks had often made me laugh against my will, as I watched him from a distance, but with whom I had never made the least acquaintance. Whether from fear or presence of mind I do not pretend to say, but I remained perfectly still, and in a minute or two Jack put his head forward and stared me in the face, uttering a sort of croak; he then descended on to my knees, examined my hands as if he were counting my fingers, tried to take off my rings, and when I gave him some biscuit, curled himself compactly into my lap. We were friends from that moment. My aversion thus cured, I have ever since felt indescribable interest and entertainment in watching, studying, and protecting monkeys. We had several on board the above-[Pg 4]mentioned vessel, but Jack was the prince of them all.

Exclusively belonging to the cook, although a favourite with the whole crew, my friend (a Cercopithecus from Senegal) had been at first kept by means of a cord, attached to the caboose; but, as he became more and more tame, his liberty was extended, till at last he was allowed the whole range of the ship, with the exception of the captain's and passengers' cabins. The occupations which he marked out for himself began at early dawn, by overturning the steward's parrot-cage whenever he could get at it, in order to secure the lump of sugar which then rolled out, or lick up the water which ran from the upset cup; he evidently intended to pull the parrot's feathers, but the latter, by turning round as fast as Jack turned, always faced him, and his beak was too formidable to be encountered. I was frequently awakened by the quick trampling of feet at this early hour, and knew it arose from a pursuit of Jack, in consequence of some mischief on his part. Like all other nautical monkeys, he descended into the forecastle, where he twisted off the night-caps of the sailors as they lay in their hammocks, stole their knives, tools, etc., and if they were not very active in the pursuit, these purloinings were thrown overboard.

When the preparations for breakfast began, Jack took his post in a corner near the grate, and when[Pg 5] the cook's back was turned, hooked out the pieces of biscuit which were toasting between the bars for the men, and snatched the bunches of dried herbs, with which they tried to imitate tea, out of the tin mugs. He sometimes scalded or burnt his fingers by these tricks, which kept him quiet for a few days; but no sooner was the pain gone than he repeated the mischief.

Two days in each week, the pigs, which formed part of our live stock, were allowed to run about the deck for exercise, and then Jack was particularly happy: hiding himself behind a cask, he would suddenly spring on to the back of one of them, his face to the tail, and away scampered his frightened steed. Sometimes an obstacle would impede the gallop, and then Jack, loosening the hold which he had acquired by digging his nails into the skin of the pig, industriously tried to uncurl its tail, and if he were saluted by a laugh from some one near by, he would look up with an assumed air of wonder, as much as to say; What can you find to laugh at? When the pigs were shut up, he thought it his turn to give others a ride, and there were three little monkeys, with red skins and blue faces, whom he particularly favored: I frequently met him with all of them on his back at the same time, squeaking and huddling together, and with difficulty preserving their seat; when he suddenly stopped, and seemed to ask me to praise the good-[Pg 6]natured action which he was performing. He was, however, jealous of all those of his brethren who came in contact with me, and freed himself from two of his rivals by throwing them into the sea. One of them was a small Lion monkey, of great beauty and extreme gentleness, and immediately after I had been feeding him, Jack called him with a coaxing, patronizing air; but as soon as he was within reach, the perfidious creature seized him by the nape of his neck, and, as quick as thought, popped him over the side of the ship. We were going at a brisk rate, and although a rope was thrown out to him, the poor little screaming thing was soon left behind, very much to my distress, for his almost human agony of countenance was painful to behold. For this, Jack was punished by being shut up all day in the empty hen-coop, in which he usually passed the night, and which he so hated, that when bed-time came, he generally avoided the clutches of the steward; he, however, committed so much mischief when unwatched, that it had become necessary to confine him at night, and I was often obliged to perform the office of nursemaid. Jack's principal punishment, however, was to be taken in front of the cage in which a panther belonging to me was placed, in the fore part of the deck. His alarm was intense; the panther set up his back and growled, but Jack instantly closed his eyes, and made himself perfectly rigid. I generally[Pg 7] held him up by the tail, and if I moved, he cautiously opened one eye; but if he caught sight of even a corner of the cage, he shut it fast, and again pretended to be dead. His drollest trick was practised on a poor little black monkey; taking the opportunity when a calm, similar to that spoken of above, left him nearly the sole possessor of the deck. I do not know that he saw me, for I was sitting behind the companion door. The men had been painting the ship outside, and were putting a broad band of white upon her, when they went to dinner below, leaving their paint and brushes on the upper deck. Jack enticed his victim to him, who meekly obeyed the summons; and, seizing him with one hand, he, with the other, took the brush, and covered him with the white fluid from head to foot. The laugh of the man at the helm called my attention to the circumstance, and as soon as Jack perceived he was discovered, he dropped his dripping brother, and rapidly scampered up the rigging, till he gained the main-top, where he stood with his nose between the bars, looking at what was going on below. As the other monkey began to lick himself, I called up the steward, who washed him clean with turpentine, and no harm ensued; but Jack was afraid to come down, and only after three days passed in his elevated place of refuge did hunger compel him to descend. He chose the moment when I was sitting on deck, and, swinging himself by a rope, he[Pg 8] dropped suddenly into my lap, looking so imploringly at me for pardon, that I not only forgave him myself, but procured his absolution from others. Jack and I parted a little to the south of the Sicily Islands, after five month's companionship, and never met again; but I was told that he was much distressed at my absence, hunted for me all over the vessel in the most disconsolate manner, even venturing into my cabin; nor was he reconciled to the loss of me when the ship's company parted in the London docks.

Another monkey, of the same species as Jack, was trained by a man in Paris to perform a multitude of clever tricks. I met him one day suddenly as he was coming up the drawing-room stairs. He made way for me by standing in an angle, and when I said, "Good morning," took off his cap, and made me a low bow. "Are you going away?" I asked; "where is your passport?" Upon which he took from the same cap a square piece of paper which he opened, and shewed to me. His master told him my gown was dusty, and he instantly took a small brush from his master's pocket, raised the hem of my dress, cleaned it, and then did the same for my shoes. He was perfectly docile and obedient; when we gave him something to eat, he did not cram his pouches with it, but delicately and tidily devoured it; and when we bestowed money on him, he immediately put it into his master's hands.[Pg 9]

Much more accomplished monkeys than those of which I have spoken, have been known to act plays, and to assume the characters they have undertaken, with a spirit and aptitude which might tempt us to suppose that they were perfectly cognizant of every bearing of their different parts; and their stratagems to procure food, and defend themselves, are only equalled by human beings.

Denizens of those mighty forests, which clothe the earth between the tropics of both the Old and New World, assembling by hundreds in those lands where the Palm, the Banyan, the Baobab, the Bombax, and thousands of magnificent trees adorn the soil; where the most delicious fruits are to be procured, by merely stretching out the hand to separate them from their parent stem; no wonder that both apes and monkeys there congregate, and strike the European, on his first arrival among them, with astonishment. I had seen many at Cape Coast; but not till I advanced into the forest up the windings of the river Gaboon, could I form any idea of their multitude, or of the various habits which characterize their savage lives. The first time the reality burst upon me, was in going up a creek of that river to reach the town of Naängo when the most deafening screams were to be heard over head, mixed with squeaks and sundry strange noises. These proceeded from red and grey parrots, which were pursued to the tops of the tallest trees[Pg 10] by the monkeys. The birds were not frightened; on the contrary, they appeared to enjoy the fun, and perching on slight twigs, which would not bear the weight of their playfellows, they stretched out their wings, and seemed vociferously to exclaim, "You can't catch me!" Sometimes, however, they were surprised, and then there was such a scuffle and noise. The four-handed beast, however, plucked the red feathers from the tail of the bird; and careless of its anger, seated himself on a branch, sucking the quills till they were dry, when he started for a fresh supply.

That monkeys enjoy movement, that they delight in pilfering, in outwitting each other and their higher brethren—men; that they glory in tearing and destroying the works of art by which they are surrounded in a domestic state; that they lay the most artful plans to effect their purposes, is all perfectly true; but the terms mirthful and merry, seem to me to be totally misapplied, in reference to their feelings and actions; for they do all in solemnity and seriousness. Do you stand under a tree, whose thick foliage completely screens you from the sun, and you hope to enjoy perfect shade and repose; a slight rustling proves that companions are near; presently a broken twig drops upon you, then another, you raise your eyes, and find that hundreds of other eyes are staring at you. In another minute you see the grotesque faces to[Pg 11] which those eyes belong, making grimaces, as you suppose, but it is no such thing, they are solemnly contemplating the intruder; they are not pelting him in play, it is their business to drive him from their domain. Raise your arm, the boughs shake, the chattering begins, and the sooner you decamp; the more you will shew your discretion.

Watch the ape or monkey with which you come into closer contact; does he pick up a blade of grass, he will examine it with as much attention as if he were determining the value of a precious stone. Do you put food before him, he tucks it into his mouth as fast as possible, and when his cheek pouches are so full that they cannot hold any more, he looks at you as if he seriously asked your approval of his laying up stores for the future. If he destroy the most valuable piece of glass or china in your possession, he does not look as if he enjoyed the mischief, but either puts on an impudent air, as much as to say, "I don't care," or calmly tries to let you know he thought it his duty to destroy your property. Savage, violent and noisy are they when irritated or disappointed, and long do they retain the recollection of an affront. I once annoyed a monkey in the collection of the Jardin des Plantes, in Paris, by preventing him from purloining the food of one of his companions; in doing which I gave him a knock upon his paws. It was lucky that strong wires were between us, or he[Pg 12] would probably have hurt me severely in his rage; he shook the cage, he rolled about and screamed, and did not forget the offence. On future occasions, the instant he heard my voice, he put himself into a passion: and several months after, although I had been absent the whole time, he seized on my gown while I incautiously stood too near to him, dragged a portion of it within the bars, and bit a great piece out of it, although it was made of a very strong material.

A monkey, of I know not what species, was domiciled in a family in Yorkshire to whom my mother was paying a visit of some days. A large dinner-party was given in honor of the guest, the master of the house helped the soup; but as he was talking at the time, he did not observe its appearance. Presently all to whom it had been served, laid down their spoons, or sent their plates away. This of course attracted attention, and on inspection, the liquid was discovered to be full of short hairs. The servants in attendance were questioned, but they declared they were ignorant of the cause; and the wisest and politest proceeding was, to send the tureen from the table, and, serving the fish, make no further comment. The mistress of the family, however, when the ladies left the dining-room, slipped away from her friends, and summoning the cook to her presence, received an explanation of the mystery. The woman said, she[Pg 13] had left the kitchen only for one minute, and when she returned, she saw the monkey standing on the hob of the kitchen grate, with one fore-paw resting on the lid of the boiler which contained the soup. "Oh, Mr. Curiosity," she exclaimed, "that is too much for you, you can't lift that up." To her horror and amazement, however, he had lifted it up, and was putting it on again after popping the kitten in, whose remains were discovered at the bottom when the soup was strained. The poor cook was so bewildered, that she did not know what to do: it was time for the dinner to be served, and she, therefore, for the look's sake, thought it best to send the soup in as it was, even if it were sent out again immediately, "because you know ma'am," said she, "that would prove you had ordered it. I always thought the monkey would do the kitten a mischief, he was so jealous of it, and hated it so because it scratched him, so he seized it when asleep."

A much better disposed monkey belonged to my eldest daughter; and we brought him to England from the Gambia. He seemed to know that he could master the child, and did not hesitate to bite and scratch her whenever she pulled him a little harder than he thought proper. I punished him for each offence, yet fed and caressed him when good; by which means I possessed an entire ascendancy over him. He was very wretched in London[Pg 14] lodgings, where I was obliged to fasten him to the bars of a stove, and where he had no fresh air; and he was no sooner let loose than he tried to break everything within his reach; so I persuaded his young mistress to present him to the Jardin des Plantes. I took him there; and during my stay in that place paid him daily visits. When these were discontinued, the keeper told me that he incessantly watched for my return, and it was long before he recovered his disappointment, and made friends with his companions in the same cage. Two years after, I again went to see him; and when I stood before him and said, "Mac, do you know me?" he gave a scream of delight, put both his paws beyond the bars, stretched them out to me, held his head down to be caressed, uttering a low murmur, and giving every sign of delighted recognition.

The most melancholy of all monkeys is, apparently, the Chimpanzee; and although he has perhaps evinced more power of imitating man than any other, he performs all he does with a sad look, frequently accompanied by petulance, and occasional bursts of fury. One of the smaller species, such as those which at different times have been brought to England and Paris, was offered to Mr. Bowdich for purchase, while our ship lay in the river Gaboon. His owner left him with us for four weeks, during which time I had an opportunity of watching his[Pg 15] habits. He would not associate with any other of the tribe, not even the irresistible Jack; but was becoming reconciled to me, when one unlucky day I checked his dawning partiality. He followed me to the Panther's cage, and I shall never forget the fearful yell which he uttered. He fled as swiftly as possible, overturning men and boys in his way, with a strength little to be expected from his size, nor did he stop till he had thrust himself into a boat sail on the after-deck, with which he entirely covered himself, and which was thenceforward his favourite abode. It was several days before I could reinstate myself in his good opinion, for he evidently thought I had had something to do with the panther. The latter had been in such a fury, that the sailors thought he would have broken his cage; and he continued restless and watchful for hours afterwards, proving that the chimpanzee is found in his country of Ashanti, further to the north than we had imagined. We did not buy the animal, on account of the exorbitant sum asked for him, and the risk of his living during a long voyage. He was always very sad, but very gentle; and his attachment to his master was very great, clinging to him like a child, and going joyfully away in his arms. Of those kept in the Zoological gardens of England and Paris, many anecdotes have been related, evincing great intelligence. One of the latter used to sit in a chair, lock and unlock his[Pg 16] door, drink tea with a spoon, eat with a knife and fork, set out his own dinner, cry when left alone, and delight in being apparently considered one of his keeper's family.

It is in equatorial Africa that the most powerful of all the Quadrumana live, far exceeding the Oran Outang, and even the Pongo of Borneo. Mr. Bowdich and myself were the first to revive and confirm a long forgotten, and vague report of the existence of such a creature, and many thought, as we ourselves had not seen it, that we had been deceived by the natives. They assured us that these huge creatures walk constantly on their hind feet, and never yet were taken alive; that they watch the actions of men, and imitate them as nearly as possible. Like the ivory hunters, they pick up the fallen tusks of elephants, but not knowing where to deposit them, they carry their burthens about till they themselves drop, and even die from fatigue: that they build huts nearly in the shape of those of men, but live on the outside; and that when one of their children dies, the mother carries it in her arms till it falls to pieces; that one blow of their paw will kill a man, and that nothing can exceed their ferocity.

A male and female, of an enormous species of chimpanzee, were brought to Bristol by the master of a vessel coming from the river Gaboon, he had been commissioned to bring them alive, but as this[Pg 17] was impracticable, he put the male into a puncheon of rum, and the female into a cask of strong brine, after they had been shot. The person who had ordered, refused to take them, and Professor Owen secured them for the College of Surgeons. The flesh of that in salt and water fell from the bones, but it was possible to set the other up so as to have his portrait taken, which likeness is now in the museum of the college. The rum had so destroyed the hair, that he could not be stuffed, he was between four and five feet high, his enormous nails, amounting to claws, were well adapted for digging roots, and his huge, strong teeth, must have made him a formidable antagonist. There could not be any thing much more hideous than his appearance, even when allowances were made for the disfiguring effects of the spirit in which he had been preserved. He was entirely covered with hair, and not wrinkled and bare in front like the smaller Chimpanzee; and it was for some time supposed, that this was the Ingheena reported by Mr. Bowdich. Since then, however, some skulls have been sent to England from the same locality, of much larger proportions, betokening an almost marvellous size and strength; and these probably, belonged to the real Ingheena. They go about in pairs; and it is evident from their enormous teeth, that, as they are not flesh-eating animals, these weapons must have been given to them as means[Pg 18] of defence against the most powerful enemies; in fact, against each other.

I now come from my own knowledge and personal experience to those of others, and I cannot begin with a more interesting account than that given by Mr. Bennett of the Ungka Ape, or Gibbon of Sumatra, the Simia Syndactyla of naturalists. He stood two feet high when on his hind legs, and was covered with black hair, except on the face, the skin of which was also black; the legs were short in proportion to the body and arms, the latter being exceedingly long. His only pouch was under the throat, the use of which was not apparent, for he did not make it a reservoir for food. He uttered a squeaking or chirping note when pleased, a hollow bark when irritated, and when frightened or angry he loudly called out "Ra, ra, ra." He was as grave as the rest of his tribe, but not equally mischievous; he, however, frequently purloined the ink, sucking the pens, and drinking the liquid whenever he could get at it. He soon knew his name, and readily went to those who called him. The chief object of his attachment was a Papuan child; and he would sit with one of his long arms round her neck, share his biscuit with her, run from or after her in play, roll on the deck, entwining his arms around her, pretend to bite, swing himself away by means of a rope, and then drop suddenly upon her, with many other frolics of a childish character.[Pg 19] If, however, she tried to make him play when he was not inclined to do so, he would gently warn her by a bite, that he would not suffer her to take any liberties. He made advances to several small monkeys, but they always drew themselves up into an opposing force, and he, to punish their impertinence, seized hold of their tails, and pulled them till the squeaking owners contrived to escape, or he dragged them along by these appendages up the rigging, and then suddenly let them go, he all the time preserving the utmost gravity.

When the hour came for the passengers' dinner he took his station near the table, and, if laughed at while eating, barked, inflated his pouch, and looked at those who ridiculed him in the most serious manner till they had finished, when he quietly resumed his own meal. This is often done by others of his race, and some seem to inquire what you see to laugh at, while others fly into a passion when such an affront is offered.

Ungka greatly disliked being left alone, and when refused anything which he wished for, rolled upon the deck, threw his arms and legs about, and dashed every thing down which came within his reach, incessantly uttering "Ra, ra, ra." He had a great fancy for a certain piece of soap, but was always scolded when he tried to take it away. One day, when he thought Mr. Bennett was too busy to observe him, he walked off with it, casting glances[Pg 20] round to see if he were observed. When he had gone half the length of the cabin, Mr. Bennett gently called him; and he was so conscience-stricken that he immediately returned the soap to its place, evidently knowing he had done wrong. He was very fond of sweetmeats; but although good friends with those who gave them to him, he would not suffer them to take him in their arms, only allowing two persons to use that familiarity, and particularly avoiding large whiskers. He felt the cold extremely as he proceeded on his voyage, was attacked with dysentery, and died as he came into a northern latitude.

A female Gibbon was for some time exhibited in London, whose rapid and enormous springs verified the account given of her brethren by M. Duvaueel, who said that he had seen one of these animals clear a space of forty feet, receiving an impetus by merely touching the branch of a tree, and catching fruit as she sprang: the one in England could stop herself in the most sudden manner, and calculate her distances with surprising accuracy. She uttered a cry of half tones, and ended with a deafening shake, which was not unmusical. She made a chirping cry in the morning, supposed to be the call for her companions, beginning slowly, and ending by two barks, which sounded like the tenor E and its octave, at which time the poor thing became evidently agitated.[Pg 21] She was, generally speaking, very gentle, and much preferred ladies to gentlemen; but if her confidence had been once acquired, she seemed to place as much reliance on a man as she bestowed unsolicited on a woman.

Monkeys in India are more or less objects of superstitious reverence, and are, consequently, seldom, or ever destroyed. In some places they are even fed, encouraged, and allowed to live on the roofs of the houses. If a man wish to revenge himself for any injury committed upon him, he has only to sprinkle some rice or corn upon the top of his enemy's house, or granary, just before the rains set in, and the monkeys will assemble upon it, eat all they can find outside, and then pull off the tiles to get at that which falls through the crevices. This, of course, gives access to the torrents which fall in such countries, and house, furniture, and stores are all ruined.

The large Banyan trees of the Old World are the favourite resorts of monkeys and snakes; and the former when they find one of the latter asleep, seize it by the neck, scramble from their branch, and dash the reptile's head against a stone, all the time grinning with rage.

The Budeng of Java (Semnopithecus Maurus) abounds in the forests of that island, and flies from the presence of man, uttering the most fearful screams, and using the most violent gestures; but[Pg 22] this is not a frequent antipathy, and there is an amusing account of the familiarity which monkeys assume with men, written by a traveller, who, probably, was not a naturalist, for he does not give the technical appellation of any of the species with which he meets in India. From what he says, however, I should suppose some of his heroes to be the same as the Macacus Rhesus. He expresses his surprise, when he sees monkeys "at home," for the first time, as being so different to the individuals on the tops of organs, or in the menageries of Europe. Their air of self-possession, comprehension, and right to the soil on which they live is most amusing. From thirty to forty seated themselves to look at his advancing palanquin and bearers, just as villagers watch the strange arrival going to "the squire's," and mingled with the inhabitants, jostling the naked children, and stretching themselves at full length close to the seated human groups, with the most perfect freedom. This freedom often amounts to impudence; and they frequent the tops of bazaars, in order to steal all they can lay their hands upon below. The only way to keep them off, is to cover the roof with a prickly shrub, the thorns of which stick to the flesh like fishhooks. The above mentioned traveller watched one, which he calls a bandar, and which took his station opposite to a sweetmeat shop. He pretended to be asleep, but every now and then softly raised[Pg 23] his head to look at the tempting piles and the owner of them, who sat smoking his pipe without symptoms even of a dose. In half an hour the monkey got up, as if he were just awake, yawned, stretched himself, and took another position a few yards off, where he pretended to play with his tail, occasionally looking over his shoulder at the coveted delicacies. At length the shop-man gave signs of activity, and the bandar was on the alert; the man went to his back room, the bandar cleared the street at one bound, and in an instant stuffed his pouches full of the delicious morsels. He had, however, overlooked some hornets, which were regaling themselves at the same time. They resented his disturbance, and the tormented bandar, in his hurry to escape, came upon a thorn-covered roof, where he lay, stung, torn, and bleeding. He spurted the stolen bon-bons from his pouches, and barking hoarsely, looked the picture of misery. The noise of the tiles which he had dislodged in his retreat brought out the inhabitants, and among them the vendor of sweets, with his turban unwound, and streaming two yards behind him. All joined in laughing at the wretched monkey; but their religious reverence for him induced them to go to his assistance; they picked out his thorns, and he limped away to the woods quite crestfallen.

The traveller came in constant contact with monkeys in his occupations of clearing land and[Pg 24] planting, and at first, as he lay still among the brushwood, they gamboled round him as they would round the natives. This peaceable state of things, however, did not last, when he established a field of sugar-canes in the newly-cleared jungle. He tells the story so well, that I must be allowed to use his own expressions:—

"Every beast of the field seemed leagued against this devoted patch of sugar-cane. The wild elephants came, and browsed in it; the jungle hogs rooted it up, and munched it at their leisure; the jackals gnawed the stalks into squash; and the wild deer ate the tops of the young plants. Against all these marauders there was an obvious remedy—to build a stout fence round the cane field. This was done accordingly, and a deep trench dug outside, that even the wild elephant did not deem it prudent to cross.

"The wild hogs came and inspected the trench and the palisades beyond. A bristly old tusker was observed taking a survey of the defenses; but, after mature deliberation, he gave two short grunts, the porcine (language), I imagined, for 'No go,' and took himself off at a round trot, to pay a visit to my neighbour Ram Chunder, and inquire how his little plot of sweet yams was coming on. The jackals sniffed at every crevice, and determined to wait a bit; but the monkeys laughed the whole intrenchment to scorn. Day after day was I[Pg 25] doomed to behold my canes devoured, as fast as they ripened, by troops of jubilant monkeys. It was of no use attempting to drive them away. When disturbed, they merely retreated to the nearest tree, dragging whole stalks of sugar-cane along with them, and then spurted the chewed fragments in my face, as I looked up at them. This was adding insult to injury, and I positively began to grow blood-thirsty at the idea of being outwitted by monkeys. The case between us might have been stated in this way.

"'I have, at much trouble and expense, cleared and cultivated this jungle land,' said I.

"'More fool you,' said the monkeys.

"'I have planted and watched over these sugar-canes.'

"'Watched! ah, ha! so have we for the matter of that.'

"'But, surely I have a right to reap what I sowed?'

"'Don't see it,' said the monkeys; 'the jungle, by rights prescriptive and indefensible, is ours, and has been so ever since the days of Ram Honuman of the long tail. If you cultivate the jungle without our consent you must look to the consequences. If you don't like our customs, you may get about your business. We don't want you.'

"I kept brooding over this mortifying view of the matter, until one morning I hatched revenge in a[Pg 26] practicable shape. A tree, with about a score of monkeys on it, was cut down, and half-a-dozen of the youngest were caught as they attempted to escape. A large pot of ghow (treacle) was then mixed with as much tartar emetic as could be spared from the medicine chest, and the young hopefuls, after being carefully painted over with the compound, were allowed to return to their distressed relatives, who, as soon as they arrived, gathered round them, and commenced licking them with the greatest assiduity. The results I had anticipated were not long in making their appearance. A more melancholy sight it was impossible to behold; but so efficacious was this treatment, that for more than two years I hardly ever saw a monkey in the neighbourhood."

When we read of the numbers, the intelligence, and the audacity of monkeys in this part of the world, it becomes a matter of curious speculation as to how they will behave when the railroad is made across India.

It has been frequently observed, that there is nothing more distressing than to see a wounded or suffering monkey. He lays his hand upon the part affected, and looks up in your face, as if appealing to your kindly feelings; and if blood flow, he views it with so frightened an expression, that he seems to know his life is going from him. An inquisitive monkey, among the numerous company[Pg 27] which sailed in a ship, always seemed desirous of ascertaining the nature of everything around him, and touched, tasted, and closely scrutinized every object to which he had not been accustomed. A pot of scalding pitch was in use for caulking the seams of the upper deck, and when those who were employed in laying it upon the planks turned their heads from him, he dipped one paw into it, and carrying it to his chin, rubbed himself with the destructive substance. His yell of pain called the attention of the sailors to him, and they did all in their power to afford alleviation; the pitch was taken off as well as it could be, his pouches being entirely burnt away, his poor cheeks were wrapped up with rags steeped in turpentine; and his scalded hand was bandaged in the same manner. He was a piteous sight, and seemed to look on all who came near, as if asking for their commiseration. He was very gentle and very sad, submitted to be fed with sugar and water through a tube, but after a few days he laid his head down and expired.

Mr. Forbes tells a story of a female monkey, (the Semnopithecus Entellus), who was shot by a friend of his, and carried to his tent. Forty or fifty of her tribe advanced with menacing gestures, but stood still when the gentleman presented his gun at them. One, however, who appeared to be the chief of the tribe, came forward, chattering and threatening in a furious manner. Nothing short of[Pg 28] firing at him seemed likely to drive him away; but at length he approached the tent door with every sign of grief and supplication, as if he were begging for the body. It was given to him, he took it in his arms, carried it away, with actions expressive of affection, to his companions, and with them disappeared. It was not to be wondered at that the sportsman vowed never to shoot another monkey.

Monkeys are eaten in some parts of the Old World, and universally in South America. M. Bonpland speaks of the flesh as lean, hard and dry; but that which I tasted in Africa, was white, juicy, and like chicken. Mr. Bowdich had monkeys served whole before him at the table of the king of Ashanti, having been roasted in a sitting posture, and he said, nothing could be more horrid or repugnant than their appearance, with the skin of the lips dried, and the white teeth, giving an aspect of grinning from pain.

The howling monkeys of South America, who make the forests resound at night, or before a coming storm, with their hideous choruses, and whose hollow and enlarged tongue bone, and expanded lower jaw enable them to utter those melancholy and startling cries, are larger and fatter than many others in the same country, and are constantly sought for as food. They eat the thick, triangular Brazil nuts (Bertholletia Excelsa), and break the hard pod which contains them with a stone, laying[Pg 29] it on the bough of a tree, or some other stone. They sometimes get their tail between the two, of course the blow falls upon the tail, and the monkey bounds away, howling in the most frightful manner.

The prettiest of all monkeys is the Marmozet; the Ouistiti of Buffon; the Simia Jacchus of Linnæus. It is extremely sensitive to cold; nevertheless, if plentifully supplied with wool, cotton, and other warm materials, will live for years in this climate. Dr. Neill of Edinburgh, that most excellent protector and lover of animals, brought one from Bahia, which he found great difficulty in training. It even resisted those who fed it, not allowing them to touch it, putting on an angry, suspicious look, and being roused by even the slightest whisper. During the voyage it ate corn and fruit, and when these became scarce, took to cockroaches; of which it cleared the vessel. It would dispatch twenty large, besides smaller ones, three or four times in each day, nipping off the head of the former, and rejecting the viscera, legs, and hard wing cases. Besides these, it fed on milk, sugar, raisins, and bread-crumbs. It afterwards made friends with a cat, and slept and eat with this animal, but it never entirely lost its distrustful feelings.

Lieutenant Edwards, in his voyage up the Amazon, mentions a domestic white monkey, which had[Pg 30] contrived to get to the top of a house, and no persuasions or threats could get him down again. He ran over the roof, displaced the tiles, peeped into the chambers below (for there are no ceilings in that country), and when called, put his thumb up to his nose. He was shot at with corn, but having found a rag, he held it up before him, and so tried to evade the shot; every now and then peeping over the top. At last he was left to himself; and when no endeavours were made to get him down, he came of his own accord. Captain Brown mentions a monkey, who, when he was troublesome in the cabin of a ship, was fired at with gunpowder and currant jelly; and in order to defend himself, used to pick up the favorite monkey, and hold him between the pistol and himself when it was presented.

A race of animals exists in Madagascar, and some of the Eastern islands, to which the name of Maki has been given, and which, although differing in the formation of the skull and teeth, must, from having four hands, be placed among the Quadrumana. They are nocturnal in their habits, very gentle and confiding, with apparently one exception, which is called the Vari. M. Frederic Cuvier has told us, that two of these being shut up in a cage together, one killed and eat his companion, leaving nothing but the skin. Two of them are remarkable for their slow, deliberate movements; and one[Pg 31] of them, named the Lemur Tardigradus, was procured at Prince of Wales's Island by Mr. Baird. He tells us that his eyes shone brightly in the dark, and that he moved his eyelids diagonally, instead of up and down. He had two tongues, one rough like that of a cat, the other narrow and sharp, and both projected at the same time, unless he chose to retain the latter. He generally slept rolled up like a ball, with his arms over his head, taking hold of his cage. He and a dog lived together in the same cage, and a great attachment subsisted between them; but nothing could reconcile him to a cat, which constantly jumped over his back, thereby causing him great annoyance.

I cannot better close this notice of Monkeys than by giving a curious legend which is told in Northwestern Africa, and which is more uncommon than the belief, which is to be found in most countries, that "monkeys can talk if they like, but they won't, for fear white men should make them work." It was related by the negroes to each other with infinite humour; the different voices of the characters were assumed, and the gestures and countenance were in accordance with the tale.

"There was once a big and a strong man, who was a cook, and he married a woman who thought herself very much above him, so she only accepted him on condition that she should never be asked to go into the cook-house (kitchen), but live in a[Pg 32] separate dwelling. They were married, and all the house he had for her was the kitchen; but she did not at first complain, because she was afraid to make her husband unhappy. At last she became so tired of her life, that she began to find fault; but at first was very gentle. At last she scolded incessantly, and the man, to keep her quiet, told her he would go to the bush (forest), and fetch wood to build her a new house. He went away, and in a few hours brought some wood. The next day his wife told him to go and fetch some more. Again he went away, stayed all day, and only brought home a few sticks, which made her so angry, that she took the biggest and beat him with it. The man went away a third time, and stayed all night, not bringing home any wood at all, saying that the trees which he had cut down were so heavy that he could not bring them all the way. Then he went and stayed two days and nights, which made his wife very unhappy. She cried very much, intreated him not to leave her, promised not to scold or beat him any more, and to live contentedly in the kitchen; but he answered 'No! you made me go to the bush, now I like the bush very much, and I shall go and stop there for ever.' So saying, he rushed out of the cook-house into the bush, where he turned into a monkey, and from him came all other monkeys."

A race of beings, to which the epithet mysterious may be with some truth applied, affords more interest from its peculiar habits, than from any proof which can be given of its mental powers; and its place in this work is due to the marvellous histories which have been related concerning it, and which have made it an object of superstitious alarm.

Bats, or Cheiroptera, are particularly distinguished from all other creatures which suckle their young, by possessing the power of flight. A Lemur Galeopithecus, which exists in the Eastern part of the globe, takes long sweeps from tree to tree, and owes this faculty to the extension of its skin between its fore and hind limbs, including the tail; but it cannot be really said to fly. The Bats, then, alone enjoy this privilege; and the prolongation of what, in common parlance, we should call the arms and fingers, constitutes the framework which supports the skin, or membrane forming the wings. The thumbs, however, are left free, and serve as hooks for various purposes. The legs, and tail (when they have any), generally help to extend the membrane of the wing; and the breast-bone is so formed as to support the powerful muscles which aid their locomotive peculiarities. They climb and[Pg 34] crawl with great dexterity, and some will run when on the ground; but it is difficult for most of them to move on a smooth, horizontal surface, and they drag themselves along by their thumbs. A portion of the Cheiroptera feeds on insects, and another on fruits; one genus subsists chiefly on blood. The first help to clear the atmosphere of those insects which fly at twilight; the second are very destructive to our gardens and orchards; the last are especially the object of that superstitious fear to which I have already alluded. They are all nocturnal or crepuscular, and during the day remain suspended by the sharp claws of their feet to the under-branches of trees, the roofs of caves, subterranean quarries, or old ruins, hanging with their heads downwards; multitudes live in the tombs of Egypt.

The appearance of Bats is always more or less grotesque; but this term more aptly applies to those which live on animal food, in consequence of the additions made to the nose and ears, probably for the sake of increasing their always acute senses of smell and hearing. The ears are frequently of an enormous size, and are joined together at the back of the head; besides which they have leaf, or lance-shaped appendages in front. A membrane of various forms is also often attached to the nose, in one species the shape of a horse-shoe. The bodies are always covered with hair, but the wings consist of[Pg 35] a leathery membrane. Another singularity in one genus is the extremity of the spine being converted into two jointed, horny pieces, covered with skin, so as to form a box of two valves, each having an independent motion. The large bats of the East Indies measure five feet from the tip of one wing to that of the other, and they emit a musky odour. The skin of the Nycteris Geoffroyi is very loose upon the body; and the animal draws air through openings in the cheek pouches, head, and back, and swells itself into a little balloon; the openings being closed at pleasure by means of valves. The bite of all is extremely sharp; and we seldom hear of an instance of one being tamed. They try to shelter themselves from chilly winds, and frequent sheltered spots, abounding in masonry, rocks, trees, and small streams.

About the Vampire, or the blood-sucker, there are different opinions: that of the East is said to be quite harmless; but it is asserted that the South American species love to attach themselves to all cattle, especially to horses with long manes, because they can cling to the hair while they suck the veins, and keep their victim quiet by flapping their wings over its head; they also fasten themselves upon the tail for the first reason, and a great loss of blood frequently ensues. Fowls are frequently killed by them as they roost upon their perches, for so noiseless and gentle are they in their flight[Pg 36] and operations, that animals are not awakened out of their sleep by their attacks. The teeth are so disposed that they make a deep and triple puncture, and one was taken by Mr. Darwin in the act of sucking blood from the neck of a horse. This able naturalist and accurate observer is of opinion, that horses do not suffer from the quantity of blood taken from them by the Vampire, but from the inflammation of the wound which they make, and which is increased if the saddle presses on it. Horses, however, turned out to grass at night, are frequently found the next morning with their necks and haunches covered with blood; and it is known that the bat fills and disgorges itself several times. Dr. Carpenter is of the same opinion as Mr. Darwin, and also disbelieves that these creatures soothe their victims by fanning them with their wings.

Captain Stedman, who travelled in Guiana, from 1772 to 1777, published an account of his adventures, and for several years afterwards, it was the fashion to doubt the truth of his statements. In fact, it was a general feeling, up to a much later period than the above, that travellers were not to be believed. As our knowledge, however, has increased, and the works of God have been made more manifest, the reputation of many a calumniated traveller has been restored, and, among others, that of Captain Stedman. I shall, therefore, unhesitatingly quote his account of the bite of the vampire,[Pg 37] "On waking, about four o'clock this morning, in my hammock, I was extremely alarmed at finding myself weltering in congealed blood, and without feeling any pain whatever. Having started up and run to the surgeon, with a firebrand in one hand, and all over besmeared with gore, the mystery was found to be, that I had been bitten by the vampire or specter of Guiana, which is also called the flying dog of New Spain. This is no other than a bat of monstrous size, that sucks the blood from men and cattle, sometimes even till they die; knowing, by instinct, that the person they intend to attack is in a sound slumber, they generally alight near the feet, where, while the creature continues fanning with his enormous wings, which keeps one cool, he bites a piece out of the tip of the great toe, so very small indeed, that the head of a pin could scarcely be received into the wound, which is consequently not painful; yet, through this orifice, he contrives to suck the blood, until he is obliged to disgorge. He then begins again, and thus continues sucking and disgorging till he is scarcely able to fly, and the sufferer has often been known to sleep from time into eternity. Cattle they generally bite in the ear, but always in those places where the blood flows spontaneously. Having applied tobacco-ashes as the best remedy, and washed the gore from myself and my hammock, I observed several small heaps of congealed blood all around the place where[Pg 38] I had lain, upon the ground; upon examining which, the surgeon judged that I had lost at least twelve or fourteen ounces during the night. Having measured this creature (one of the bats), I found it to be, between the tips of the wings, thirty-two inches and a half; the colour was a dark brown, nearly black, but lighter underneath."

Mr. Waterton, whom all the world recognizes as a gentleman, and consequently a man of truth, laboured at one time under the same stigma of exaggeration as Captain Stedman, and many other illustrious travellers; and he confirms the blood-sucking in the following terms:—"Some years ago, I went to the river Paumarau, with a Scotch gentleman. We hung our hammocks in the thatched loft of a planter's house. Next morning I heard this gentleman muttering in his hammock, and now and then letting fall an imprecation or two, 'What is the matter, Sir,' said I softly, 'is anything amiss?' 'What is the matter!' answered he surlily, 'why the vampires have been sucking me to death.' As soon as there was light enough, I went to his hammock, and saw it much stained with blood. 'There,' said he, thrusting his foot out of the hammock, 'see how these imps have been drawing my life's blood.' On examining his foot, I found the vampire had tapped his great toe. There was a wound somewhat less than that made by a leech. The blood was still oozing from it, and[Pg 39] I conjectured he might have lost from ten to twelve ounces of blood."

Mr. Waterton further tells us, that a boy of ten or eleven years of age was bitten by a vampire, and a poor ass, belonging to the young gentleman's father, was dying by inches from the bites of the larger kinds, while most of his fowls were killed by the smaller bats.

The torpidity in which bats remain during the winter, in climates similar to that of England, is well known; and, like other animals which undergo the same suspension of powers, they have their histories of long imprisonment in places which seem inimical to life. There are two accounts of their being found in trees, which are extremely curious, and the more so, because the one corroborates the other. In the beginning of November, 1821, a woodman, engaged in splitting timber for rail-posts, in the woods close by the lake at Haining, a seat of Mr. Pringle's, in Selkirkshire, discovered, in the centre of a large wild-cherry tree, a living bat, of a bright scarlet colour, which, as soon as it was relieved from its entombment, took to its wings and escaped. In the tree there was a recess sufficiently large to contain the animal; but all around, the wood was perfectly sound, solid, and free from any fissure through which the atmospheric air could reach the animal.

A man engaged in splitting timber, near Kelsall,[Pg 40] in the beginning of December, 1826, discovered, in the centre of a large pear-tree, a living bat, of a bright scarlet colour, which he foolishly suffered to escape, from fear, being fully persuaded (with the characteristic superstition of the inhabitants of that part of Cheshire), that it was "a being not of this world." The tree presented a small cavity in the centre, where the bat was enclosed, but was perfectly sound and solid on each side. The scarlet colour of each of these prisoners seems at present to be inexplicable, and makes these statements still more marvellous.

Professor Bell, in his admirable work on British Quadrupeds speaks of a long-eared bat which fed from the hand; and if an insect were held between the lips, it would settle on its master's cheek, and take the fly from his mouth with great quietness. So accustomed was it to this, that it would seek his lips when he made a buzzing noise. It folded its beautiful ears under its arm when it went to sleep, and also during hibernation. Its cry was acute and shrill, becoming more clear and piercing when disturbed. It is most frequently seen in towns and villages. This instance of taming to a certain extent might, perhaps, be more frequently repeated, if bats were objects of more general interest.

There is a tribe of animals constantly around our country habitations, of underground and nocturnal habits, some of which become torpid in winter. All are timid and unobtrusive, and yet have great influence upon our welfare; for they check the rapid increase of those worms and insects which live and breed beneath the soil, and would destroy the crops which are necessary to our existence. There are certain and constant characters in their formation, which bring them all under one group, called Insectivora, or Insect-eating Mammalia, by naturalists; but among them are smaller groups of individuals, with peculiar characters, adapted to their different habits.

The mole is an instance of one of these minor groups; which, with one exception, has a portion of sight in spite of its reputation for being blind. Its smell and hearing, however, are so acute, that they make up for the deficiency in the other sense, a highly developed organ for which, would be very much in the way of an animal which makes its habitation within the earth, and which rarely comes to the surface in the day time. Its fore-feet are largest, and powerful muscles enable it to dig up the soil and roots which oppose the formation of its galleries, and which are thrown up as they become loosened.[Pg 42] The nose, or snout, is furnished with a bone at the end, with which it pierces the earth, and in one genus this bone has twenty-two small, cartilaginous points attached to it, which can be extended into a star. A vein lies behind the ear of all, the smallest puncture of which causes instant death.

The food of moles chiefly consists of worms, and the larvæ, or grubs of insects, of which they eat enormous quantities. They are extremely voracious, and the slightest privation of food drives them to frenzy, or kills them. They will all eat flesh, and when shut up in a cage without nourishment, have been known to devour each other. There is a remarkable instance of a mole, when in confinement, having a viper and a toad given to it, both of which it killed and devoured. All squeeze out the earthy matter which is inside worms, before eating them, which they do with the most eager rapidity. In June and July, they prowl upon the surface of the ground, generally at night, but they have been seen by day, and this is the time in which they indulge in fleshy food, for then they catch small birds, mice, frogs, lizards, and snails; but although when in confinement one was known to eat a toad, they generally refuse these reptiles, probably from the acrid humour which exudes from their skin. They, on these occasions of open marauding, are often caught and devoured in their turn by owls at night, and dogs by day. They have a remarkable[Pg 43] power of eating the roots of the colchicum, or meadow saffron, which takes such powerful effect on other animals, and which they probably swallow for the sake of the larvæ or worms upon them. Such is their antipathy to garlic, that a few cloves put into their runs, will cause their destruction.

A French naturalist, of the name of Henri Lecourt, devoted a great part of his life to the study of the habits and structure of moles, and he tells us, that they will run as fast as a horse will gallop. By his observations he rendered essential service to a large district in France, for he discovered that numbers of moles had undermined the banks of a canal, and that, unless means were taken to prevent the catastrophe, these banks would give way, and inundation would ensue. By his ingenious contrivances and accurate knowledge of their habits, he contrived to extirpate them before the occurrence of further mischief. Moles, however, are said to be excellent drainers of land, and Mr. Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, used to declare, that if a hundred men and horses were employed to dress a pasture farm of 1,500 or 2,000 acres, they would not do it as effectually as moles would do if left to themselves.

The late Earl of Derby possessed a small deserted island, in the Loch of Clunie, 180 yards from the main land, and as proof that moles swim well, a number of them crossed the water, and took[Pg 44] possession of this place. They are said to be dragged, as beavers are, by their companions, who lay hold of their tail, and pull them along while they lie on their backs, embracing a quantity of soil dug out in forming their runs. The fur of the mole is very short, fine, and close, and is as smooth and soft as Genoa velvet.

Moles display a high degree of instinct in the skilful construction of their subterranean fortresses. Their site is not indicated by those little mounds of loose earth, which we see raised up at night, and which mark their hunting excursions, but under a hillock reared by themselves, and protected by a wall, bank, or roots of a tree. The earth is well worked, so as to make it compact and hard, and galleries are formed which communicate with each other. A circular gallery is placed at the upper part of the mound, and five descending passages lead from this to a gallery below, which is of larger circumference. Within this lower gallery is a chamber, which communicates with the upper gallery by three descending tunnels. This chamber is, as it were, the citadel of the mole, in which it sleeps.

A principal gallery goes from the lower gallery, in a direct line to the utmost extent of the ground through which the mole hunts, and from the bottom of this dormitory is another, which descends farther into the earth, and joins this great or prin[Pg 45]cipal road. Eight or nine other tunnels run round the hillock at irregular distances, leading from the lower gallery, through which the mole hunts its prey, and which it constantly enlarges. During this process it throws up the hillocks which betray its vicinity to us. The great road is of various depths, according to the quality of the soil in which it is excavated; it is generally five or six inches below the surface, but if carried under a stream, or pathway, it will be occasionally sunk a foot and a half. If the hillock be very extensive there will be several high-roads, and they will serve for several moles, but they never trespass on each other's hunting grounds. If they happen to meet in a road, one is obliged to retreat, or they have a battle, in which the weakest always comes off the worst. In a barren soil, the searching galleries are the most numerous, and those made in winter are the deepest, because the worms penetrate beyond the line of frost, and the mole is as active in winter as in warm weather.

The females have a separate chamber made for them, in which they bring forth their young. This is situated at some distance from the citadel, and placed where three or four galleries intersect each other. There they have a bed made of dry grass, or fibres of roots, and four or five young are born at the same time, which begin to get their own food when they are half grown.[Pg 46]

Like all voracious animals, moles require a large quantity of water, consequently their run, or fortress, generally communicates with a ditch or pond. Should these dry up, or the situation be without such resources, the little architect sinks perpendicular wells, which retain the water as it drains from the soil.

Moles shift their quarters according to circumstances, and as they swim well, they migrate across rivers; and in sudden inundations are able, not to save themselves alone, but their young, to which they are much attached. The stratagem and caution which they practise in order to secure a bird are highly curious: they approach without seeming to do so, but as soon as they are within reach of their prey, they rush upon it, tear open its body, thrust their snout into the intestines, and revel in their sanguinary feast. They then sleep for three or four hours, and awake with renewed appetite.

All mole-catchers will bear testimony to the rapid movements and consequent difficulty of catching these animals. I have watched a gardener stand for half an hour by one of the little hillocks of loose earth, which, from its movement, showed that the mole was there at work, and remain motionless, spade in hand, and when he saw the earth shake, dash his weapon into the heap. The mere uplifting of his arm was sufficient, and before the spade could reach the ground the mole was gone. He could[Pg 47] scarcely reckon on securing his victim once out of twenty efforts.

No moles are found in the north of Scotland, or in Ireland, which some attribute to soil and climate; but they exist in other parts of Europe under similar circumstances.

Hedgehogs form one of the small groups of insect-eating mammalia, and are remarkable for being also able to eat those substances which are destructive to others; for instance, they will devour the wings of Spanish flies (Cantharides) with impunity, which cause fearful torments to other animals, and not the least to man, by raising blisters on his skin. It would seem that the hedgehog is also externally insensible to poison, for it fights with adders, and is bitten about the lips and nose without receiving any injury. An experiment has been made by administering prussic acid to it, which took no effect.

It is well known that hedgehogs are covered with bristles, amounting to sharp prickles, and that they roll themselves up into a ball. This is effected by a peculiar set of muscles attached to the skin, by which they pull themselves into this shape, and at the same time set up every bristle, and drag their[Pg 48] head and limbs within. Such is the resistance and elasticity of these bristles, that the owners of them may be thrown to great distances and remain unhurt, and they will even throw themselves down steep places when they wish to move from a particular spot.

Hedgehogs are nocturnal animals, and frequent woods, gardens, orchards, and thick hedge-rows. It is in the latter that I have heard of one being mistaken by a hen for a bush, in which she might lay her egg in safety. The fact was announced by the triumphant cackling which these birds vociferate on such occasions: the egg was consequently searched for, and found upon the hedgehog's back.

Hedgehogs feed on insects, slugs, frogs, eggs, young birds in the nest, mice, fallen fruits, and the roots of vegetables, especially the plantain, boring into the ground to get at these substances. They will clear a house of black beetles in a few weeks, as I can attest from my own experience. My kitchen was much infested, not only by them, but by a sort of degenerated cockroach, descended from the better conditioned Blattæ, brought in my packages from a tropical country, and which had resisted all efforts for their extermination, such as boiling water, pepper, arsenic-wafers, mortar, etc. At last, a friend, whose house had been cleared of beetles by a hedgehog, made the animal over to me, very much to the discomfort of my cook, to whom it[Pg 49] was an object of terror. The first night of its arrival a bed was made for it in a hamper, half full of hay, and a saucer of milk was set within. The next morning the hedgehog had disappeared, and for several days the search made for it was fruitless. That it was alive was proved by the milk being drunk out of the saucer in which it was placed. One night I purposely went into the kitchen after the family had been for some time in bed, and, as I opened the door, I saw the little creature slink into a hole under the oven attached to the grate. Fearing this would sometimes prove too hot for it, I had some bricks put in to fill up the aperture. The next night the bricks were pulled away, and overturned, evincing a degree of strength which astonished us; but, after that, we left the animal to its own care. The beetles and cockroaches visibly disappeared, but as they disappeared other things also vanished; kitchen cloths left to dry at night were missing; then, a silk handkerchief. At last a night-cap left on the dresser was gone; and these abstractions were most mysterious. The next day there was a general search in possible and impossible places, and the end of a muslin string was seen in the oven-hole; it was seized on, and not only was the night-cap dragged out, but all the missing and not missing articles which the hedgehog had purloined; most of them were much torn, and it was supposed that the poor beast had taken[Pg 50] possession of them to make a soft bed. I have not seen such a propensity noticed elsewhere, and it may be a useful hint to those who keep hedgehogs. All endeavours to make this animal friendly were unavailing; but I am told, that hedgehogs are frequently quite domesticated; and even shew a degree of affection.

Dr. Buckland ascertained the manner in which hedgehogs kill snakes; they make a sudden attack on the reptile, give it a fierce bite, and then, with the utmost dexterity, roll themselves up so as to present nothing but spines when the snake retaliates. They repeat this manœuvre several times, till the back of the snake is broken in various places; they then pass it through their jaws, cracking its bones at short intervals; after which they eat it all up, beginning at the tail. The old legend, that hedgehogs suck the udders of cows as they lie on the ground chewing the cud is, of course, wholly without foundation. They retreat to holes in trees, or in the earth where they make a bed of leaves, moss, etc., in which they roll themselves, and these substances sticking to the spines make them look like a bundle of vegetable matter. In this condition they pass the winter, in a state of torpidity; but it should be mentioned, that one which was tame, retained its activity the whole year. There are instances of hedgehogs performing the office of turnspits in a kitchen; and, from the facility with[Pg 51] which they accommodate themselves to all sorts of food, they are easily kept. They, however, when once accustomed to animal diet, will attack young game; and one was detected in the south of Scotland in the act of killing a leveret.

Among the Carnivora, or flesh-eating animals, Bears take the first place; for their characters and habits link them in some degree with the preceding order, the Insectivora. Both principally live on fruit, grains, and insects, and only eat flesh from necessity, or some peculiarity of life, such as confinement, or education.

The Carnivora are divided by naturalists into three tribes, the characters for which are taken from their feet and manner of walking. Bears rank among the Plantigrada, or those which put the whole of their feet firmly upon the ground when they walk. They are occasionally cunning and ferocious, but often evince good humour, and a great love of fun. In their wild state they are solitary the greater part of their lives; they climb trees with great facility, live in caverns, holes, and hollow trees; and in cold countries, retire to some secluded spot during the winter, where they remain concealed, and bring forth their young. Some say[Pg 52] they are torpid; but this cannot be, for the female bears come from their retreats with cubs which have lived upon them, and it is not likely, that they can have reared them and remained without food; they are, however, often very lean and wasted, and the absorption of their generally large portion of fat, contributes to their nourishment. The story that they live by sucking their paws is, as may be supposed, a fable; when well-fed they always lick their paws, very often accompanying the action with a peculiar sort of mumbling noise. There are a few which will never eat flesh, and all are able to do without it. They are, generally speaking, large, clumsy and awkward, possessing large claws for digging; and often walk on their hind-feet, a facility afforded them by the peculiar formation of their thigh-bone. They do not often attack in the first instance, unless impelled by hunger or danger; they are, however, formidable opponents when excited. In former times there were few parts of the globe in which they were not to be found; but like other wild animals, they have disappeared before the advance of man. Still they are found in certain spots from the northern regions of the world, to the burning climes of Africa, Asia, and America. The latest date of their appearance in Great Britain, was in Scotland, during the year 1057.

Bears are always covered with thick fur; which, notwithstanding its coarseness, is much prized for[Pg 53] various purposes. They afford much sport to those inclined for such exercises; but the cruel practice of bear-baiting is discontinued. In an old edition of Hudibras, there is a curious note of a mode of running at the devoted bears with wheelbarrows, on which they vented their fury, and the baiters thus had them at their mercy. At present the hunts are regularly organised fights, or battles, besides which there are many ways of catching them in traps, pitfalls, etc.

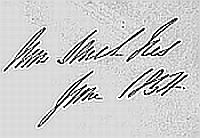

The large polar bear (Ursus Maritimus), with its white fur, its long, flattened head, and black claws, may be seen in great perfection at the Zoological Gardens. In its own country, during the winter, it lives chiefly on seal's flesh, but in the summer eats berries, sea-weed, and marsh plants. It is one of the most formidable of the race; and may be seen climbing mountains of ice, and swimming from floe to floe with the greatest rapidity. Captain Lyon tells us, that when a seal lies just ashore, the bear gets quietly into the water and swims away from him to leeward; he then takes short dives, and manages so that the last dive shall bring him back close to the seal, which tries to escape by rolling into the water, when he falls into the bear's paws; and if he should lie still, the bear springs upon and devours him; its favourite food, however, is the floating carcases of whales. The gait of all bears is a sort of shuffle; but this one goes at such[Pg 54] a rate, that its pace is equal to a horse's gallop. It is remarkably sagacious, and often defeats the stratagems practised for its capture. A female with two cubs was pursued across a field of ice by a party of sailors; at first she urged the young ones to increase their speed, by running in front of them, turning round, and evincing, by gesture and voice, great anxiety for their progress; but finding that their pursuers gained upon them, she alternately carried, pushed, or pitched them forwards, until she effected their escape. The cubs seemed to arrange themselves for the throw, and when thus sent forwards some yards in advance, ran on till she again came up to them, when they alternately placed themselves before her.

A she-bear and two large cubs, being attracted by the scent of some blubber, proceeding from a seahorse, which had been set on fire, and was burning on the ice, ran eagerly towards it, dragged some pieces out of the flames, and eat them with great voracity. The sailors threw them some lumps still left in their possession, which the old bear took away and laid before her cubs, reserving only a small piece for herself. As they were eating the last piece, the men shot the cubs, and wounded the mother. Her distress was most painful to behold, and, though wounded, she crawled to the spot where they lay, tore the piece of flesh into pieces, and put some before each. Finding they did not eat, she tried to[Pg 55] raise them, making piteous moans all the time. She then went to some distance, looked back and moaned, and this failing to entice them, she returned and licked their wounds. She did this a second time, and still finding that the cubs did not follow, she went round and pawed them with great tenderness. Being at last convinced that they were lifeless, she raised her head towards the ship, and, by a growl, seemed to reproach their destroyers. They returned this with a volley of musket balls;[1] she fell between her cubs, and died licking their wounds.

The black bear of Canada is a formidable creature, and Dr. Richardson contradicts the assertion that it is not swift of foot; he says that it soon outstrips the swiftest runner, and adds, that it climbs as well, if not better than a cat. It feeds on berries, eggs, and roots; but although it does not seek flesh, it does not refuse it when offered. A young bear of this kind roughly handled a Canadian settler, who, being a very large powerful man, returned hug for hug, till the surprised bear let go its hold. It had ventured into some young plantations, where it was committing much mischief, and the settler had endeavoured to frighten it away. A friend of mine was in the house when the gentleman returned home, his clothes torn in the struggle, and very much exhausted by the encounter; he dropped into [Pg 56]a chair, and nearly fainted, but a little brandy revived him, though he was ill some days from the pressure.