The Project Gutenberg EBook of Halsey & Co., by H. K. Shackleford

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Halsey & Co.

or, The Young Bankers and Speculators

Author: H. K. Shackleford

Release Date: June 29, 2007 [EBook #21963]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HALSEY & CO. ***

Produced by Richard Halsey

Mr. Barron, the rich banker in Broad street, was seated at his desk in his private office one day when the door was opened by the porter, who said:

"There's a newsboy out here who says he must see you, sir."

"Go and tell him to let you know what he wants. If it's a situation, tell him we have none vacant."

The porter went back to the outer office. In a minute or two the door opened again and the newsboy entered and closed the door behind him. The banker recognized him as the boy who had brought him the afternoon papers daily for a year back.

"The bouncer told me to go away, sir," the boy said, doffing his hat as he spoke, "but I knew my business better than he does. There's a couple of men putting up a big job on your bank, and I knew if I didn't tell you about it they'd scoop you for a big pile."

The banker wheeled his chair around so as to face the boy, and laid his gold glasses on the desk.

"Who are they, and how did you find out about it?" he asked.

"I don't know who they are, but I found it out by overhearing their talk."

"What is their plan?"

"A forged check."

"Whose name is forged?"

"I don't know, sir. They had a genuine check and were comparing it to the forged one. They said it was perfect and would be paid if presented when the cashier was busy."

"Ah! I see. That means a little before three o'clock. Now, my boy, do you think you could point them out to a detective when they come up to the cashier's window?"

"Yes, sir."

"Not afraid of them, eh?"

"No, sir. I am not afraid of anybody."

The banker smiled, reached over on his desk and tapped a small bell. The door opened and a messenger appeared.

"Tell Caruth to come here," the banker said to him.

The messenger disappeared, and a few moments later the bank detective came in.

"Caruth," said the banker, "this boy tells me he overheard two men plotting to present a forged check to-day. Take him out there with you and arrest the man he points out to you. Let the man get the money, though, so as to make a good case against him."

Caruth looked at the boy and said:

"I know you by sight. What's your name?"

"Fred Halsey."

"Well, go along with him, Fred," the banker said to him. "It may be a bad business if you make a mistake."

"Come on, Halsey," and the detective led the way out into the public hall of the bank.

Fred followed him, and the two were soon in a crowd of people, who were coming and going all the time. Caruth took up a position near the cashier's window where he could see every man who stopped there. Fred stood by his side and closely scanned the faces of those who came and went.

More than an hour passed, and still they stood there on the watch. The detective was used to it, but Fred had been more active, and he began to wish the men would come along. Suddenly he nudged Caruth with his elbow–nudged him good. Caruth leaned over till his face was on a level with Fred's.

"That's him–the man in the gray ulster."

Caruth looked up and saw a man in a gray ulster and with gold glasses on.

"Do you see the other one?" he asked.

"No, I don't see him."

"Well, look for him. Sure you have the right man now?"

"Yes. That's one of 'em."

Caruth did not pretend to look at the man in the line. But he kept him in view all the time. The man finally got up to the window and presented a check. The cashier looked at the check and then at the endorsement. He gave the man a hasty glance and then began counting out a large sum of money, using bills of large denomination to expedite the counting. He handed out the money and the man gathered it up and was putting it into his pocket when Caruth laid a hand on his arm and said:

"The president of the bank wants to see you in his private office a few moments."

Suddenly, and without any warning, the stranger kicked Caruth's feet from under him, and he fell heavily on the tiled flooring, his head striking it so hard that he became instantly unconscious. The stranger made a break for the street entrance. Quick as a flash Fred Halsey sprang forward in front of him, darted between his legs, and caused him to fall forward on his face. The man was quick, though, and caught on his hands. He was on his feet again in an instant. Again Fred darted between his legs and threw him. This time he rolled completely over and Fred saw the handle of a revolver protruding from a hip pocket. He grabbed it, cocked it, and held the muzzle within a foot of the forger's head, saying:

"I'll shoot!"

The man lay still, glaring at the black muzzle of the weapon like one confronting a ghost. Mr. Barron heard the noise of the three falls, and rushed out of the office in time to see Fred aim the revolver at the head of the forger.

"Arrest that man!" he cried. "He is a forger."

A forger is the one criminal most hated in Wall Street, and as soon as it was announced that he was one, the stranger was instantly surrounded and captured. A policeman came in from the street and put the nippers on him.

"Bring him into my office, officer," said the banker. "He has a lot of the bank's money in his possession."

The officer took him to the president's room, and Fred followed, with the pistol still in his hand. He was searched, and the money found in his pocket. The cashier brought in the check and said he did not believe it was forged.

"Send for Mr. Manson and see what he says about it," suggested the banker.

Manson was a rich broker, whose name had been forged to the check. He was found at his office and came over to the bank immediately. Taking the check, which was for $10,000, he made a close examination of it.

"I never gave that check to any one," he said. "It is a forgery, but such a good one that ordinarily I would not be able to detect it myself."

"I took it in good faith," said the stranger. "Can you swear it was forged?"

"Yes, for I have given out no check for that amount to-day."

"The date is nothing. Is that your signature?"

"It is very much like it, but I did not write it, nor did I ever give a check to any such party."

"You will swear to that?" Barron asked him.

"Yes–a thousand times."

"Then I'll take the responsibility of the man's arrest and prosecution. You may take him away, officer."

The policeman led his prisoner out, and a dozen prominent brokers got around Barron to congratulate him on the arrest. Barron looked around and saw Fred standing near the door, still holding the revolver in his hand.

"Ah! There's the one to whom I am indebted for the arrest," and he went over to where Fred was standing, extended his hand to him, and added:

"He not only came and gave me warning, but actually made the arrest himself. Caruth, our detective, was hurt, and the forger would have escaped but for this boy here," and he, wrung Fred's hand as he spoke.

"That's so," remarked a broker, shaking Fred's hand. "I saw the whole business myself, but didn't know what it meant. Shake, my dear boy," and he gave him a hearty handshake. A half dozen others followed, and one said:

"Here, let's set him up. We want to encourage boys like him," and he drew a ten-dollar bill from the inside pocket of his vest and laid it on the desk. "Cover that with as much as you please, gentlemen."

Seven other laid down similar amounts, and Barton remarked;

"Whatever you give, gentlemen, I'll double it."

"Very good," said another, putting down a ten. "We'll all chip in."

The sum of $130 was laid on the desk while Fred stood there looking on, with his heart way up in his throat.

"Now, Fred Halsey," the banker said to the newsboy. "I am going to double this sum, giving you two hundred and sixty dollars. What are you going to do with so much money?"

"Set up a bank of my own," was the prompt reply at which the banker and the brokers broke into a roar of laughter.

"Gimme ten dollars," Fred said, "and keep the rest in the bank for me."

"Very well; here's the ten," and Fred took the bill and went out on the street, feeling richer than ever before in his life.

Fred Halsey was a sturdy youth of sixteen whose father had died when he was but ten years old. He was a manly little fellow who knew how to take care of himself in his career of newsboy. He had laughing blue eyes and a handsome face, while his mouth showed that he possessed a dauntless spirit. His mother died long before his father did, and he and his little sister lived with an aunt–his mother's sister–who was a childless widow. She was a mother to him and Adah, who was two years younger than Fred, a pretty blue-eyed little miss with golden hair and pearly teeth.

She did washing, and Fred sold papers, while Adah was a cash girl in one of the big stores on Grand street. Even then it was but a poor living for them in the great city, where grasping landlords demanded rent money with the regularity of the almanac. When Fred Halsey went out of the bank with ten dollars in his pocket and $250 more in the bank behind him, he had a feeling in his heart he never had there before. The whole world seemed opened to him. Rich bankers and brokers had shaken hands with him and praised him for what he had done.

"And I'm rich now myself," he said to himself, as he darted up toward Broadway. "Whew! I'm rich! I'm rich!"

"Hello, Fred!"

"Hello, Bob! Where are you going?"

"Up to the telegraph office."

"I'm going that way, too," and he went along with Bob Newcombe, a messenger boy in Broker Manson's office, who was his chum and friend, and about the same age as himself.

"Sold all your papers?" Bob asked.

"Yes, all I am going to sell to-day,"

"Made enough to stop on, eh?"

"Yes."

Bob laughed and remarked:

"If I had a hundred dollars I could make three hundred in a week."

Fred started.

"How?" he asked.

"Big deal going on in the Stock Exchange. Heard 'em fixing it up in the office this morning."

"What is it?"

"Corner in B. & H."

Fred had been selling papers in Wall Street long enough to be familiar with all the terms used by brokers and bankers. He knew all about "puts" and "calls," "bulls" and "bears," and had read eagerly the stories of fortunes won or lost in the mad whirl of speculation down there.

"Sure you could make it, Bob?" he finally asked of the messenger boy.

"Of course I am. I've seen it done many a time. When three or four big brokers club together to boom a stock it booms, and then the lambs lose their fleece."

"But wouldn't you be a lamb and lose your fleece, too?"

"No. I wouldn't buy when it had boomed. I'd buy before and sell when it went up."

They entered the telegraph office, and Bob sent off the message he had brought, after which they went out on the street again.

"What's B. & H. going at now?" Fred asked.

"It's going at forty-seven. It will be up to fifty to-morrow when the Stock Exchange closes."

"How do you know that?"

"Mr. Manson is going to buy up all the stock. He has millions behind him. The stock will go up, up, up, till it topples over on the lambs. Oh, I've seen it done a dozen times. If I had one hundred dollars, I'd put it up on ten percent margin–every dollar of it–and scoop in three hundred dollars inside of a week."

"Say, Bob, I've got the 'scads.'"

"Eh! Huh?" and Bob stopped and stared at him.

"I've got the 'chink,' the 'rhino,' the hundred dollars," and Fred told him the story of what had taken place in the bank but a short half hour before.

Bob was staggered.

"Git a hundred quick, Fred. Mr. Tabor will buy on a margin for us."

"Come on. I'll do it," and Fred hurried back to the bank and sent word in to Mr. Barron that he wanted $100 more of his money.

It was sent out to him, and he and Bob ran round to Broker Tabor's office. It lacked but ten minutes of three o'clock.

"Mr. Tabor, will you buy on a margin for us?" Bob asked the broker.

"Hello, Halsey!" exclaimed the broker, on seeing Fred.

"Hello, sir," returned Fred, seeing he was one of the brokers who had given him the money in Barron's office.

"Yes. What is it you want bought?" the broker asked Bob.

"B. & H., sir."

"All right; where's your money?"

"Here it is," said Fred, handing him the money.

"Going into business, eh?"

"Yes, sir."

"Well, what name shall I use?" and Tabor took up his pen to write a receipt for the money.

"Halsey & Co.," said Bob. "I don't know whether Mr. Manson would like to have me do such a thing, so put it that way. It's Fred's money, too."

The broker laughed, wrote the receipt, and handed it to Fred, with the remark:

"You will soon learn how easy it is to lose money in Wall Street."

"When a man loses, somebody wins," Fred replied, and Tabor never forgot the remark, for he had reason to remember it ere he was a year older. The two boys went out and Bob said, when they reached the sidewalk:

"I've got to go back to the office, but won't have to stay long as it is nearly three o'clock. Come along and wait for me."

Fred went with him and waited downstairs at the street entrance for him while he was standing there. Manson, whose name had been forged to the check which Fred had been instrumental in stopping, came down the stairs, accompanied by a tall, white-haired old man.

"Ah! There's the boy now, general," said Manson, on seeing Fred. "He threw the villain twice and then held him with the revolver till others secured him."

"Well, really, my lad," said the general, extending his hand to Fred. "I honor courage wherever I find it. Shake hands with me. I am glad to know you."

Fred shook hands with the old man without uttering a word, the meeting taking him quite by surprise. Just as he was going to speak several brokers came up and shook hands with the general, and he was forgotten. In a little while Bob came down, and the two went away together.

"See here, Fred," Bob said, "we must not say a word about this thing. I got the tip in the office, you know."

"Yes, I know."

"At 47 one thousand will get 21 shares." Bob continued. "Par value is 100. They will try to run it in to that; if they do, we'll make more than $300."

"But if it goes backwards or down instead of up, we won't know what hit us," remarked Fred.

"That's true. But it's going up," said Bob, with a good deal of emphasis. "I have seen it done before, and know just how it works."

They walked up to Broadway and turned toward the City Hall. All the newsboys knew them, and, as a late edition of the afternoon papers had an account of the arrest of the forger, in which Fred's name was mentioned, some of the boys ran to him to ask him about it. The account said nothing about the money that had been given Fred, so he felt relieved. Of course he had to stop and tell them about it. While he was doing so a man came by and asked:

"Do any of you know a newsboy named Fred Halsey?"

"Yes, I do," replied Fred very promptly, ere any of the others could do so.

"Where can I find him?"

"Oh, he's around somewhere, He never stops long in one place," and he winked at the boys as he spoke.

They all understood at once that Fred did not wish them to give him away, and not one would have done so under any circumstances.

"I'd like to give one of you a dollar to find him and point him out to me."

"Show us your dollar and I'll tell you how to find him yourself," said Fred.

"Here's your money," and the man handed him a dollar bill. Fred took it and said:

"That cop over there by the Astor House corner is his dad. Just go over there and stand there a while and you'll see him come up to the old man. He meets him there about this time every day."

The man, who seemed to be in earnest, seemed half inclined to doubt what Fred had told him.

"Is that so, boys?" he asked, appealing to the boys.

"Yes!" the entire crowd sung out.

He turned away and walked over to the Astor House corner.

"What's yer givin' 'im, Fred?" one of the boys asked.

"Whist!" half whispered Fred. "He's a pal of that forger and is looking for me to do me up. Come on and we'll eat up this dollar," and he led the way to a fruit stand up beyond the City Hall, where he spent the money the man had given him for bananas for the boys.

"Well, that was the slickest thing I ever saw done," said Bob. "Why don't you have him arrested and sent to join the other fellow?"

"Got no proof on him."

"You said he was his pal."

"Yes, but I couldn't prove it, only my word for it, that's all. He wants to lay me out for giving the snap away."

"How do you know he does?"

"Do you think he wants to thank me, give me a new suit of clothes and invite me to dine with him at Del's?" and Fred gave the least tinge of a sneer to his tones as he spoke.

"Well, hardly," Bob replied, laughing good-naturedly. "It is well enough to know what the fellow wants, though."

Fred did not reply, and Bob added:

"He'll find you out, anyway."

"Yes, so he will. Better go back and see what he wants. I'll go with you. He can't do us both up."

"Come on. Let's go and see if he is there," and the two young friends turned and made their way back to the Astor House where they had sent him.

When the two boys arrived at the Astor House corner, they failed to find the man there. While looking around for him he came up to Fred, laid a hand on his shoulder and said:

"It was a neat little game you played on me. Where does the laugh come in?"

Fred laughed and asked:

"Where were you born?"

"Right here in New York."

"Must have got lost then. What do you want of me?"

"I am a detective and have been on the tracks of a band of forgers for months. I see in the papers that you helped bag one of them to-day. You gave warning to the bank. That's what I want to see you about. There is a big reward up for the arrest of the gang. If you can give me any information that may lead to the arrest of any of them you can have one half the reward."

"Not much I won't," Fred replied, shaking his head. "I can arrest the whole gang myself and get all the reward."

"That's all nonsense. You can't arrest any man. You're but a boy yet."

"Yes, that's so. But I got one of 'em to-day. I could call that cop over here now and get another but I am not ready for you yet."

"What do you mean?' the man asked, turning pale with a frightened look in his eyes.

"I mean I am on to you."

"How on to me?"

"Oh, you make me tired. I got your pal to-day. Look out I don't get you to-morrow."

The look of amazement on the man's face was a picture. Fred looked up at him and laughed. Then he turned away and went over across the street, as if to speak to the policeman there. The man hurried across Broadway, and was lost in the crowd surging along Park Row.

"That was a good scare you gave him, Fred," Bob said, as they walked on up the street.

"Yes. I knew it would be. I wouldn't tell him how I got onto his game. That's what he wanted to find out."

"You have got to look out for him after this."

"I am going to do that."

They went up Broadway to Grand street, and then turned toward the Bowery. Both lived on the east side, above Grand street, in the densely populated districts where rents were cheap and everybody poor. Adah had not come in from the store. His aunt was very tired from the labor of a hard day's wash, and therefore not in the best of humor.

"What brought you home so soon?" she asked, looking at him.

"Just to make you stop work. You are killing yourself, aunt."

"Would you tell me which is the best way to die–of hard work or starvation?" she asked.

"Oh, we are not going to die for a long time yet. You'll marry again, and we'll all be rich."

She straightened herself up by the side of the tub and glared at him.

"What's the matter with you, Freddie?" she asked. "Are you sick, child?"

Fred laughed and said:

"Not sick, but tired."

"Well, so am I, and all poor people, as for that matter. Did you give up selling papers and come home to rest?"

"No, aunt. I came home to give you a rest. Just look at the color of that, and tell me what you think of it," and as he spoke he laid a ten-dollar bill on the corner of a little table near where she stood.

She glanced at the bill and almost gasped out:

"Ten dollars! Fred Halsey, where did you get that money?"

"Downtown, aunt. Does it relieve that tired feeling to look at it?"

"Whose is it? Why don't you tell me about it?"

"It's yours, every cent of it, and I've got fifteen more bills of that size in the bank."

The good woman dropped down into a chair and glared at her nephew. Fred went to her, put his arms about her neck, kissed her and said:

"I've had good luck to-day, aunt. Just read that and you will understand it all," and he gave her a copy of an afternoon paper in which was the story of the capture of the forger in Barron's bank.

"And they gave you this money for what you did?" she exclaimed, when she had finished reading it.

"Yes. They just chipped in and gave me a pile of money. I left all in the bank but this, which I wanted to give to you. And you can have every cent of the rest whenever you want it–you and sister."

"Oh, you dear, good boy!" she exclaimed, her eyes filling with tears as she caught him in her arms. "I knew you would always be good to me."

"You've been a mother to us, aunt, and I'll never go back on my mother!"

Adah came home from the store tired and hungry. At supper her aunt told her of Fred's adventure and good fortune. She sprang up and danced around the room in her joy and then kissed him a half dozen times.

It did seem like an enormous sum to her a girl of but fourteen summers.

"What are you going to do with it, Fred?" she finally asked.

"Give it to aunt and to use for you and herself."

They all had pleasant dreams that night. Fred dreamed of the big fortune made in Wall Street; and Adah dreamed that she was no longer a cash girl in a big store, but wore fine dresses and rode in a carriage. The next morning, however, Fred ate early and hurried off downtown to sell papers, and Adah was at the store at her usual hour. Fred delivered to all his Wall Street patrons and then sold on the street to passersby all the morning. He was all around the Stock Exchange, for there he found the most customers. Inside the Stock Exchange he heard the brokers yelling like so many lunatics. That was so often the case, however, that he gave it little thought. But soon he saw Bob Newcombe, Manson's messenger, come out in a great hurry and dart off down the street.

"Guess Manson is busy inside," he said to himself as he kept his eyes open for customers.

In a few moments Bob came running back. He ran up against Fred.

"Just go up in the gallery and see how B. & H. is climbing up, Fred," he said to him.

"How much has it gone up, Bob?" Fred asked him.

"Five points, and that means $100 for us," Bob replied.

"Whew!" and Fred whistled.

Bob dashed into the Exchange by way of the side entrance on New street and disappeared from view.

"Guess I'll go up in the gallery and look on a while," Fred said to himself. "Here, Mugsey, you can have my papers," and he turned over about one dozen papers to an ugly little newsboy whom the others called Mugsey.

The little fellow was astonished.

"Do yer give 'em ter me, Fred?" he asked before taking them.

"Yes. I'm done for the day."

Fred found quite a crowd of people up in the gallery, and among them a party of ladies from out of town. They were sightseeing. But there was nothing new to him up there. He wanted to see Broker Manson and watch the rise of B. & H. stock. It took him some time to find Manson in the moving mass of yelling brokers on the floor below. But he finally found him, and for half an hour never took his eyes off of him. He heard him offering fifty-three and finally fifty-four for B. & H. It has thus gone up seven points since the day before.

"Bob was right," he said. "He knew what he was about. B. & H. is climbing right up to the top. Hanged if I don't put in another hundred!" and he ran down and out into the street like a young lunatic. In five minutes he had put up another hundred dollars with Broker Tabor for Halsey & Company to buy more B. & H. stock on margin. The stock was bought immediately at 54 1/2-eighteen shares.

That done, Fred returned to the Exchange and watched proceedings from the gallery. He kept his eyes on Broker Manson. The big broker was buying the stock at a tremendous rate, all that was offered him. People were coming and going all the time. Fred finally turned to look at a young girl whose voice sounded like music in his ears. She was close by his side. She was accompanied by an elderly couple, evidently her parents. He thought her very beautiful and that she had the most musical voice he had ever heard.

She changed positions several times as though looking for somebody on the floor below. He noticed a tall, well-dressed man keeping close behind her, peering over her shoulder at the crowd below. Something in his movements caused Fred to look at him the second time, and to his amazement he saw him pick the pockets of both the ladies. The thief then started to leave, but Fred grabbed his coat-tail, saying:

"Here, I saw that little game. It won't go. Ladies, this man has got your pocketbooks."

Quick as a flash the thief grabbed him and lifted him above his head. Fred saw he was going to be hurled headlong among the brokers below, and to save himself seized his assailant's coat collar. The two ladies screamed, and the next moment Fred and the pickpocket fell over the gallery and went down in a heap on the yelling brokers below.

The screams of the ladies caused every broker to look up from the floor of the Stock Exchange. Like a flash they saw a man and boy come tumbling down upon them from the gallery. There was a party of four brokers grouped together immediately under them, and, as a matter of gravitation, they landed on top of them–on their heads and shoulders. Hats were crushed and a confused mass of humanity scrambled about on the floor. The yelling ceased when the shrill screams from the gallery were heard, and brokers ran forward to help those who had fallen. The pickpocket struck out desperately, trying to shake off Fred. In doing so he hit Broker Bryant in the face. Bryant was a hard hitter himself, and instantly returned the blow–a half dozen or more.

"Blast you, take that!" he hissed, and he gave him lightning-like blows till he sank down on the floor unconscious.

"Won't somebody hold him?" Fred cried out. "He's a pickpocket!"

"Who is he?" somebody asked Bryant.

"I don't know and don't care," was the blunt reply. "He hit me in the face after tumbling down on my head."

By this time the policeman on duty at the Stock Exchange pushed his way through the crowd of brokers and called out:

"What is it? What's the trouble here?" and he looked at the pickpocket, who was slowly pulling himself together.

"This man is a pickpocket," said Fred. "He took those ladies' purses up there, and when I caught him at it he tried to throw me over the gallery. He did throw me, but I brought him down with me."

"Good–good!" cried a broker. "Three cheers for the kid!"

The brokers cheered and then laughed.

"I am no pickpocket," exclaimed the thief, as soon as he saw the officer had him. "The boy lies. I merely—"

"Officer, search him!" cried the elder of the two ladies up in the gallery. "He has my purse and that of my daughter."

"Yes, search him! Search him!" called out a dozen at once.

Brokers held him and the officer searched him. He found the two purses or pocketbooks in his pockets.

"That one is mine!" cried the elderly woman.

"What does it contain, madam?" the officer asked.

"Money and two diamond rings. You can open it and see for yourself."

It was opened and her claim verified.

"Madam, you will have to appear against this man," said the officer, looking up at the elderly lady, and he led the prisoner out of the Stock Exchange and into one of the many offices of the building.

The lady, accompanied by her husband and daughter, appeared in the room and claimed her property. The young girl, who seemed to be about sixteen years old, turned to Fred and said:

"We are indebted to you for recovering our purses. I hope you were not hurt by the fall?"

"Only a little bit," he replied.

"I'm so sorry!"

"Oh, it's nothing," and he laughed. "It was fun to jerk him over with me."

Then she laughed, too, and Fred thought hers the sweetest face he had ever seen in all his life.

"What is your name?" she asked him.

"Fred Halsey."

"My name is Eva Gaines. I want to remember your name, for I never had such a fright in all my life."

"I'll be sure to remember yours," Fred remarked.

"Why will you? Because you were hurt?"

Fred looked around and saw that everybody also in the room was listening to the claiming of the two purses, so he went close up to her and said in a half whisper:

"Because you are the most beautiful girl I ever saw."

"Oh, my!" and her face flushed and eyes sparkled.

Young as she was, she was woman enough to know that it was honest admiration on the part of the youth. Fred seemed half frightened over what he had said and drew back. But she gave him a look and a smile that told him plainly he had not offended. He was going to say more to her, but at that moment her father turned to her, saying:

"Here, daughter, your purse is yours again," and he held it out to her.

She took it, opened it quickly and glanced at its contents.

"Young man," said Mr. Gaines, turning to Fred, "you've got the right stuff in you," and he extended his hand, which Fred grasped and shook. "I won't forget you. I have a brother who is a member of the Stock Exchange, and I want send your name to him. What is it?"

"I have his name, father," said the young girl.

"Ah, very well, then," and he gave Fred's hand another shake and turned away.

But he left a $20 gold coin in it, which Fred's fingers closed over very promptly. The next moment they were gone. Fred put the goldpiece in his pocket, while the thought flashed through his mind that the young girl was all gold herself. The officer took his name and address as a witness, and then led his prisoner away to the police station. Just as he was leaving the room a broker called out to Fred:

"That man will never forgive you for his arrest. He will set some friends of his after you, so you had better be on your guard."

"I'm on my guard all the time, sir," Fred replied.

"What is your name?"

"Fred Halsey."

The broker wrote the name on his cuff and then went out of the room. Fred thought nothing of the incident, and went out a moment or two later himself, going to the street, hoping to see Bob and find out how B. & H. was doing. Out on the street he found that nobody had heard of the pickpocket's arrest in the Exchange building.

"I am $20 in on that racket, anyhow," he said to himself as he walked around to the side entrance of the Exchange. "I would like to do as well every day in the year. Lord, but she is a beauty!"

He was thinking of the girl. Somebody ran into him and the two came near going down in a heap together.

"Hello, Fred! I'm in a hurry!" exclaimed the other.

It was Bob!

"Well, don't you know me well enough not to try to run over or through me? You can save time by running around me every time."

But Bob was off like a flash, and Fred judged by that B. & H. was humming, for Manson was booming it and Bob was his messenger. Seeing two brokers talking near the New street entrance, Fred went over near enough to hear one say:

"It will go to 70 to-morrow and somebody will be burnt."

"Yes, I think so, too,"

The Exchange closed for the day, and Fred went around to meet Bob again. He met Manson at the foot of the stairs, his face flushed from the excitement of his tremendous battle in the Exchange.

"Ah!" the big broker exclaimed. "I see you caught another thief to-day. Why don't you turn detective? It seems to be your forte."

"I'd rather be a broker, sir," Fred replied.

"A broker, eh?" and Manson looked him full in the eyes. "Think you have nerve enough for that?"

"Yes, sir. I've got nerve enough. It's money I want."

Manson laughed and shook his head.

"We all want money. That's what we are here for. But there are more losers than winners."

"What one man loses another one wins," said Fred.

"Of course, but one man sometimes wins from a thousand at one turn, so you see there are always more losers than winners," and the big broker went on up to his office, leaving Fred at the foot of the stairs waiting for Bob.

He was quietly waiting there and watching people come and go when he was startled by a cry above. He glanced up and saw some one falling from the upper floor and sprang aside just in time to escape being crushed. It was a messenger boy from Broker Tracey's office.

"Oh, Lord!" gasped Fred. "He must be killed!" and he sprang forward to pick him up.

The boy was unconscious. Instantly a dozen brokers were on hand to render aid. Broker Tracey came running down to see about him and get the telegram the boy was sent out with. Bob came hurrying down too.

"This is too bad," said Tracey. "I am sorry. He is a good messenger. Janitor! Janitor!"

The janitor came and by that time the boy had recovered consciousness. He groaned in agony. The physician, whose office was in the building, examined him.

"Left arm and leg broken," he said.

"Lord, but I am sorry. Doctor, take charge of him, see him through and send your bill to me. Tom, my boy, your pay shall go on just the same. See if anything is wanted, janitor, and get it for him. Where is the telegram, Tom?"

"In my pocket, sir," said Tom, white as a sheet.

It was found and given to the broker, who turned to Bob and said:

"Please send that off for me, Bob, and if you know of a boy who can make a good messenger send him to me in the morning."

"Hello, Fred! This is the place for you!" and Bob grabbed Fred by the arm and forced him around in front of Tracey. "Here's the one you want, sir–Fred Halsey."

"All right; come here to-morrow morning."

So the next morning Fred went to Tracey's office and was engaged as messenger. During the day B. & H. went to 87 and Fred as soon as he was sent on an errand stopped in at the bank and bad his shares sold for Halsey & Co.

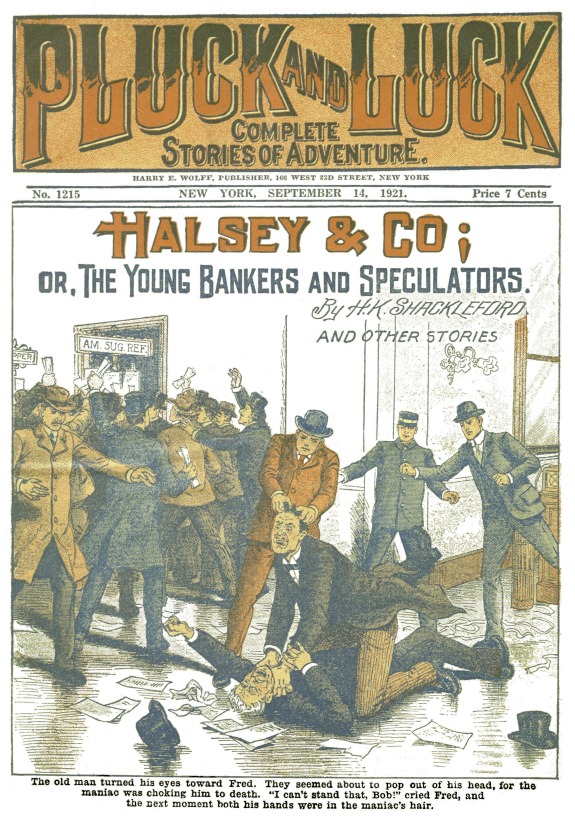

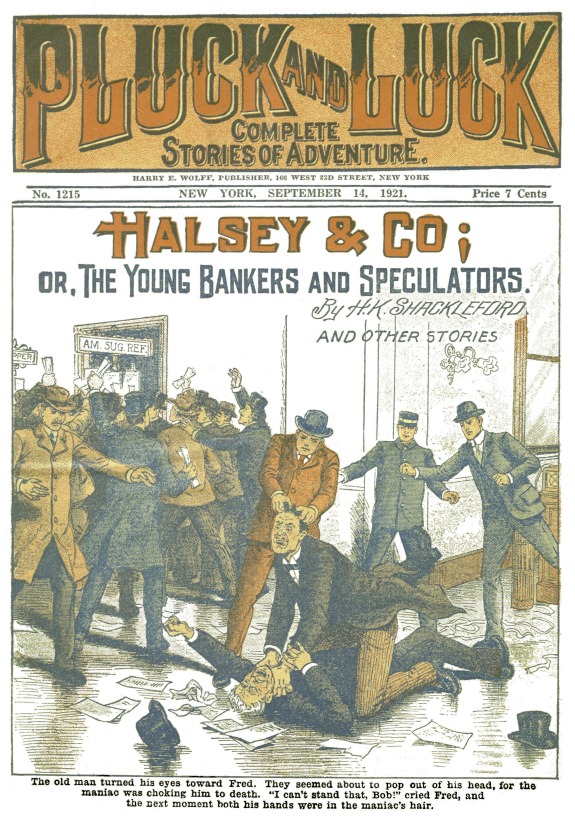

Bob was getting $6 a week as messenger for Tracey and it pleased his aunt greatly. The next day Tabor gave Bob a statement for Halsey & Co., showing a net profit of over $1,200, which he placed to their credit. Fred and Bob were standing under the gallery of the Stock Exchange in the place allotted to messengers, when Broker Keeley gave a howl and sprang at the throat of Broker Gaines. They fell to the floor. The old man turned his eyes toward Fred. They seemed to pop out of his head for the maniac was choking him.

"I can't stand that!" cried Fred, and the next moment both his hands were in Broker Keeley's hair. He let go the old man's throat, and a dozen brokers ran in to separate them and quell the row.

Next day Fred said to Bob: "I met Gaines's typewriter just now and she said Mr. Gaines had not been to the office since his row with Broker Keeley. The clerk who is running the office insulted her and she wants to leave."

"By George!" answered Bob, "Bryant's girl has just asked me to find a place for her. What did you tell Callie?"

"I told her I would look out for her, and I will."

During the day Fred got a place for Callie with Broker Tabor, and Bob secured a temporary place for Bertie Clayton in old Broker Bowles's office.

The day after the two boys met the girls in a restaurant, and Callie told Fred of a tip she had come across. It was Pacific Mail, and it was going to be cornered.

Fred and Bob came away from the restaurant with the two girls, going toward Wall Street. Fred asked Callie several questions about the deal she had mentioned.

"I'll make a note of what I can find out," she said to him, "and let you know after 3 o'clock."

"But be careful and let no one else know it," he replied.

"Oh, I can keep a secret even if I am a girl," and she left him on the corner of Nassau and Wall to go to the bank.

Fred clutched Bob's arm when the two girls were gone, and said:

"Callie says a big corner in Pacific Mail is being made up in Barron's office."

"By George! Is it straight, do you think?"

"Yes. She says she'll make notes and give 'em to me. She let it out by saying if she had any money laid up she could make a pile out of Pacific Mail. I soon got the whole thing out of her."

"When will you see her again?"

"After three o'clock."

It was a little after three o'clock when Fred saw her come out of the bank. He went to meet her, and she said to him:

"Bryant is going to do the buying–begins to-morrow. You won't tell any one that I told you?"

"No; that would never do."

She lived over on the west side, and had a widowed mother and little brother to support. He walked nearly all the way home with her. Bob went uptown with Gertie Clayton, and did not see Fred again till the next morning.

"I am going to buy Pacific Mail, Bob," Fred said to him.

"Go ahead then–for Halsey & Company–the whole pile."

Pacific Mail was going that morning at 52. Fred went to Tabor and asked him to buy Pacific Mail on 10 per cent margin. Tabor gave a start, looked keenly at him for a moment, and then asked:

"Why do you buy that stock?"

"I heard a man tell another one it was safe to try it."

"Give me his name."

"No, sir. Will you buy it for me?"

"I'd rather not do it," and he shook his head.

"Oh! Then I'll try somebody else," and Fred went away with a check for $1,200 in his pocket.

He went over to Bowles' office, and arranged with the old man to buy for him 230 shares at 52. The old broker had the shares bought inside of ten minutes. By twelve o'clock Fred saw Bryant buying all that he could get hold of, but there were thousands and thousands of shares on the market, and he had bought 10,000 ere there was any signs of life in the deal. Then it began slowly to advance. It closed with an advance of one point on the first day. But the next day saw it go up three points, and the brokers in the Exchange began to hustle. It was an immense concern and the shares were in every broker's hands. But Bryant gathered them in by the thousand at a time. On the third day it was up to sixty, and Fred met Callie at lunch to tell her she had got the thing down fine.

"Oh, if I only had some money to put up!" she said.

"You have got ten per cent interest in my little pile," he said to her.

"What! Just for the tip?"

"Yes."

"Oh, my! I could give you tips almost every day."

"Wall Street is always full of tips," and he laughed. "Such a thing as this, though, comes but once or twice a year."

"B. & H. was a big thing for some of the brokers," she replied.

"Yes, and a very bad one for a number of them, too."

"Do you know, I think Mr. Gaines was badly squeezed in that deal?"

"Ah! I saw him nearly choked to death by that fellow who lost his head. If I had not interfered he'd have been killed."

"Oh, was it you?" and she opened wide her blue eyes.

"Yes–why?"

"Why, he has sent down to the office instructing the clerks to try to find out who it was. His niece, Miss Eva Gaines, called at the office and spoke to me about it."

Fred opened his eyes in astonishment.

"She is such a sweet girl," added Callie, "I promised to let her know if I ever found out who it was. Why, he might give you a gold watch or something. Who knows?" and she laughed merrily as she told him the story.

"Well, I am surprised," was all he could say.

"What shall I say to her when I see her or write to her?" Callie asked him.

"Tell her what you please."

They left the little restaurant together and did not meet again till the same hour the next day. Then Pacific Mail was going at 66 and the brokers were again in a furor. Coming so soon after the panic caused by the corner in B. & H. shares, it caused a general interest throughout the city.

"I wrote to Miss Gaines yesterday," Callie said to him, "and told her that you–Fred Halsey–was the one who had saved her uncle's life in the Stock Exchange, and you may expect a sweet-scented note of thanks from her at any moment."

On returning home from lunch Fred found the excitement in the Exchange greater than ever, the shares had bounded up to 72. He went to the office and found Tracey out.

"He is around at the Exchange," the head bookkeeper said to him. "Go and report to him at once."

Tracey was howling like the rest of them when Fred touched him on the arm and said:

"I am ready for duty, sir."

"Ah! Find Manson and bring him to me–quick!"

He looked about among the brokers, but failed to find him. Meeting Bob, he told him Tracey wanted to see Manson.

"He is in his office," Bob replied.

"I'll go after him then," and he darted out of the side door of the Exchange and hurried around to Manson's office.

"Mr. Manson," he said, "Mr. Tracey told me to bring you to him at once."

"When did he tell you?"

"Just two minutes ago in the Stock Exchange."

Manson arose, put on his hat and went out. Fred followed him, and both were soon in the midst of the frantic mob of brokers again. Bryant was the coolest man in the whole crowd. He knew what he was there for and kept taking all the shares that were offered him. Fred saw Manson and Tracey meet and go under the gallery for a few moments' consultation. He kept an eye on them, for he was not sure of their connection with the P. M. combine. By and by they went out and he followed. In the crowd on the street he lost sight of them. Then he went back to the office and told the head clerk.

"Wait here and see if he returns," said the clerk, and he did so.

The broker came back a few minutes before the Exchange closed and sent Fred to the bank with a big check to deposit. After depositing the check he turned to look into the president's room. Barron was out, but he saw through the glass door that Callie was idle. She caught his eye and came out to speak to him.

"Any news?" he asked.

"No. Mr. Barron told a man just now that he thought P. M. would go to par to-morrow."

"Then I won't sell to-day."

"Why, no, wait till to-morrow. How much did you put up, Fred?"

"Oh, I had to buy on a margin," he replied.

"Of course. I didn't expect you to do otherwise. Did you put up as much as fifty dollars?"

"Yes, more," he replied.

"Oh, my!" she exclaimed. "That would get nearly ten shares on ten per cent, margin. You promised me ten per cent, for the tip, mind you."

"Yes, and you shall have it," he replied, "but don't say a word or you'd be discharged."

"Oh, I can hold my tongue when I want to," and she turned and went back into the office.

When Fred returned to the office the Exchange had closed for the day. Pacific Mail closed at 76. Bob met him at the foot of the stairs, grasped his hand and said:

"We've struck it rich, Fred!"

"Yes, but you want to keep mum."

"Of course."

They went home and spent the evening together making calculations. Adah wanted to know why they were making such a lot of figures, and Bob said to her:

"Wall Street men have to do a good deal of figuring."

"Yes, so I've heard, but I didn't know the boys did."

Fred laughed, nudged Bob and remarked:

"That's one on you, old man!"

The next day they found that the shares opened at 79–two hours later they were going at 82.

"I'm going to sell, Bob," said Fred. "It's getting dangerous."

"It may go up to 100."

"We had better stand from under," said Fred, shaking his head.

"Well, let her go."

Fred hastened to Bowles' office and told him to sell. In five minutes it was done, and they had made over $6,000 on the deal. Manson sent Bob to Bryant with a note. Somebody had just dumped 3,000 shares on the big broker and he was in a bad humor when Bob came to him with the note. He looked down and saw who it was–the boy who had gotten the situation for his typewriter–and quick as a flash he gave him a kick that sent him sprawling on the floor. Bob had the note still in his hand when he scrambled to his feet again. But he did not deliver it. He staggered out of the Exchange, feeling sick from the effects of the blow, and made his way back to the office, where he told Mr. Manson what had happened.

"It was an accident, Bob," the broker said. "The excitement in there is awful, you know."

"No, sir. It was no accident," said Bob. "He hates me because I found a place for his typewriter who left him because he wanted to make love to her."

Munson laughed and said:

"That must me a mistake, my boy."

"No mistake about it. The girl is in Bowles' office, and she'll tell you the same thing. I am going to have him arrested."

"Oh, that won't do."

"I'll make it do."

Bob was mad.

"See here, young man, I'll give you your walking papers if I hear any more talk like that!"

"Give 'em to me right away then," said Bob. "I'm going to see if a man can kick the innerds out of a boy just for fun and not pay for it."

Manson was surprised at Bob's spunk. He looked at him in silence for a minute or two and then said:

"You are mad clear through, eh?"

"You bet I am!"

"Well, wait till I see him before doing anything."

"All right; but you want to see him soon."

"I'll see him after 3 o'clock."

After 3 o'clock Bob, Fred and Broker Manson went over to Bryant's office. Bryant was at his desk.

"Why did you kick my messenger, Bryant?" Manson asked.

"Was it your messenger?"

"Yes."

"I didn't know who it was. I felt some one pulling my coat-tail and kicked out. It was no time for fooling. You know, somebody is always fooling over there?"

"That's a lie," said Bob. "You know I touched your elbow, not your coat-tail. You looked down in my face, saw who it was and then kicked me."

Bryant was so astounded at being given the lie so bluntly he sat still and heard Bob through without uttering a word; then he looked up at Manson and said:

"There's cheek for you!"

"Cheek!" exclaimed Bob. "Don't say a word about cheek! Your cheek drove your typewriter out of your office. I got a place for her, and you had the cheek to go to her new place and raise a row. That is what you kicked me for. Two members of the Exchange told me to prosecute you and call them as witnesses–Mr. Turner and Mr. Agnew."

Bryant turned white as a sheet. Those two brokers were his bitterest enemies. They stood high, and their evidence would down him.

"See here, my boy," he said, "I ought to kick you clean through that window for your impudence, but I won't. I tell you—"

"Of course, you won't," said Bob, interrupting him. "It's my time to kick now."

Bryant was cool, pale, and yet in a rage. He saw that he was in a serious scrape, and Bob, though a boy, was game all through.

"Are you willing for Mr. Manson to settle the matter?" he asked.

"No, sir. He is not my lawyer."

Bryant gave a start.

"Who is pour lawyer?" he asked.

"I haven't engaged one yet, but you can bet I am going to."

"Well, I see you are very mad about it. We can settle it ourselves, I think, Just tell me what you want me to do."

"Well, I think you ought to be made to break stone over on the Island for about six months. You need a good lesson and I'd like to see you get one of that kind."

"The court would probably fine me $50. Will that sum satisfy you?"

"No, sir. You think money is everything. I don't. Just acknowledge that you are an old hog and beg my pardon, and you may go to the Old Harry for all I care!"

That was too much for the big broker. He sprang forward and dealt Bob a stinging slap in the face. But the next moment both Bob and Fred sprang up like two wildcats.

He tried to defend himself, of course, but those two boys had fought many a battle in the street and were fighters from way back. They rolled on the floor together, while Manson kept calling out:

"Boys! Boys! I'll call the police to you!"

They never heard him. If they did they didn't heed him. In half a minute both eyes were blacked, all the beard from one side of his face gone, and fully one-half of his hair lay on the floor. And still they went for him. Suddenly the shrill scream of a woman startled them, and the two boys desisted to turn and look at the newcomer.

It happened to be Bryant's wife who uttered the scream when she saw what was taking place. Of course the row ended then and there. Bryant got up, explained to his wife what it all was about and apologized right then for his action. Of course Bob accepted it, and the matter was settled, as the boys thought. But the next day Bob met Fred and told him he had been discharged by Manson, saying that of course Bryant was responsible for it.

A couple of days later Fred was the recipient of a handsome gold watch and chain, a present from Mr. Gaines.

One day Callie came to Fred and told him of a tip she had got hold of. It was M. & C. Fred went to see Broker Bowles, and asked him to buy 3,000 shares of M. & C. for him. The broker bid in the amount of shares Fred wanted. The price soon went up to 90, and then Bowles sold him out. The next day Fred and Bob visited Bowles, who gave them a statement showing they had made $170,000 profit.

"Mr. Bowles," said Fred, "Risley & Cohn have failed. If their office is to rent please rent it for five years for Halsey & Co., and buy all the furniture. Pay a year's rent in advance."

"Bob, I'm going to resign," said Fred, when they came out from Bowles' office.

"Resign what?"

"My place at Tracey's."

"Well, I think you can afford to."

"Yes. We can go in on our own hook now," and he went over to the office and told the gruff old broker he wanted to quit.

"What's the matter?" Tracey asked.

"Going to open a bank."

"What with, a jimmy?"

"No, a key."

"Going to play craps, I guess. Do you know a boy I can get?'

"Yes, sir."

"Bring him here then and I'll let you off."

In half an hour Fred had a youth on hand who lad been looking for a place for mouths. He then went downstairs and joined Bob. They agreed to keep the deal a secret as long as possible. Bob was to wait for Gertie Clayton, Bowles' typewriter, and warn her to say nothing about it to any one, while Fred was to wait for Callie as she came out of Barron's bank. When business closed for the day, Fred saw Callie come up and go up toward Broadway. He soon joined her.

"Have you heard the news from the deal in M. & C.?" he asked her.

"No. How did is turn out?"

"It sold at 80."

"Did you sell?"

"Yes."

She made a rapid calculation and said:

"You have made a fortune."

"Yes, so we have, but mum is the word."

"Do I get anything?"

"Of course; ten percent."

She gasped, turned pale, and seemed almost ready to faint.

"I have a check for your share in my pocket," he added.

"How much is it?"

"Seventeen thousand."

"Oh, Fred!"

"Do suppose you would turn up your nose at a eager boy now if he were to come courting he remarked.

"That depends on who he is and how he behaves himself," she replied, regaining control of herself.

Then a minute or two later she asked:

"What am I to do? Please tell me for my head is all in a whirl."

"Oh, don't lose your head," said he laughing. "Just leave it where you left the other one and that will be all right. Keep your eyes and ears open for another tip."

"Why, must I keep on at work?"

"Yes, of course. How can you get any tips if you don't?"

"I'm afraid I can't do much work with so much money in bank."

"Why, that ought to make you work harder. You should not think of stopping before you have made at least one hundred thousand dollars. Then you could live in a fine house and keep a carriage."

They went on up the street talking and laughing. He gave her the check and she put it in her pocket.

"Now, Callie," he said, "I've rented a flat in the block above where you live and have bought some furniture for it. I want you to select the carpets, curtains and other things for me, as I don't know what they are worth, or even what sort to get. I am preparing a surprise for my aunt and sister."

"Oh, that is good of you! They don't know of your good luck yet?"

"They don't even dream of it."

"Oh, what a surprise it will be to them. Of course I will help you, Fred. Where are you going to buy?"

"Come along with me," and they went to a big store where he had already purchased some things. She had good tastes, good judgment and was a quick buyer. In half an hour she had made the selections; Fred paid the bill and ordered everything put into the flat as soon as possible.

Then he saw her home, left her at the entrance and made his way across town toward his aunt's humble abode. She was still at work over the tub, and, as a matter of course, very tired.

"I'll break all that up in a few days," he said to himself.

Two days later Broker Bowles said to him:

"You can get Risley & Cohn's offices, but the rent is high–$5,000 a year. They ask $3,000 for the furniture as it stands."

"Take both for Halsey & Company," said Fred. "Pay one year in advance. I'll give you a check for $8,000," and he did.

"I'll have the lease for you this afternoon," said the old man.

Bob and Fred then went off to engage a sign painter to put up their firm name in big gold letters on the immense plate glass front of the offices.

The next day they found their name

"HALSEY & COMPANY, "Bankers, "Speculators in Stocks, Bonds, etc."

in big gold letters, the handsomest on the street. Mr. Allison, the man who had kept the books for Risley & Cohn for fifteen years, had been engaged for them by Bowles, who told him they were a couple of boys. He was elderly, bald, with a full, round face known to every broker in Wall Street. His knowledge of Wall Street was thorough.

"It will create a sensation when it is known who Halsey & Company are," he remarked to them, as they watched the people admire the sign as they went by.

"Yes, I guess so. We'll have some fun with 'em. But see here, Mr. Allison, we are no fools if we haven't got any beards. We want you to manage the banking end of this thing, and stand ready to collar us when you see us going wrong. Do you understand?" and Fred faced him as he spoke.

The old man looked over his glasses at him for a few moments as if surprised at what he had just heard.

"Well, that shows you have good, old-fashioned horse sense, young man," he replied. "Most boys of your age think they know it all, and have to pay dearly for lessons they might have had free."

Just then Broker Tracey came by and stopped to look at the new firm name on the glass front. Fred went to the door and invited him in. Tracey looked at him in astonishment and then at the sign again.

"How do you like our new quarters?" Fred asked him.

"Whose quarters?"

"Halsey & Company–Fred Halsey and Bob Newcombe–we are the firm. Mr. Allison here is our manager."

Tracey glanced at Allison, whom he had known for years, and the old man said:

"It is true, Sir."

"Got any capital?" Tracey asked.

"Plenty of it," replied Allison.

He turned on Fred and asked:

"What has happened? Where did you get it?"

"What some people lose others gain," Fred replied. "I got a good deal of fleece out of M. & C. the other day. Did you lose any wool?"

Tracey's face was a picture to look at. He was a loser in that deal to the tune of some $20,000, and this sudden and unexpected discovery of where it had gone was a shock to him.

"Well, I'm jiggered!" he exclaimed, looking at Allison. "I've been thirty years in Wall Street and these are the first boy bankers I ever saw."

"They are the first I ever saw, too, sir," said Allison, "and I've been thirty-five years in the Street. They've both got good heads on their shoulders."

"Just come in here and let me show you something. Mr. Tracey," said Bob, leading the way into the private office of the former bankers. "I want to show you some fleece we have on exhibition," and he pointed to a large bunch of white wool hanging to a hook on the wall above his desk, labeled:

"JAMES BRYANT, "M. & C. fleece."

The old broker roared.

"Say, I hope you won't hang mine up that way!" he exclaimed.

"We have too much respect for you to do that sir."

"How about Manson?"

"Oh, we got a good lot off him, but I was once in his employ."

"Well, I'm glad you haven't got mine hung up," and he went out, laughing heartily.

In an hour the whole Street had the news, and scores of brokers came by to look in at the two boys. They were all amused, for they laughed and joked each other about it.

Half an hour later a wave of jolly laughter went through the Street as the fleece story was told. Bryant was guyed till he had to shut himself up in his office and refuse to see any one. Manson came in and whispered to Bob to drop that Bryant's fleece business, adding:

"He has a host of friends in Wall Street, and it will hurt your business to make an enemy of him."

"He is already my enemy," Bob replied, "and had me discharged from your employ. I will never let up on him as long as I live."

Just before business closed Bryant rushed into the office and said:

"I want to see the bunch of wool you have here with my name on it."

"Here it is," said Bob, opening the door of the private office and pointing to the wool hanging against the wall.

Bryant grabbed it and started to the door with it. Bob opened the drawer of the desk, took out a revolver, and aiming at him, said:

"Here's something to go with it."

Bryant wheeled around and found himself looking down the muzzle of the revolver.

When Broker Bryant saw the muzzle of a revolver staring him in the face he turned white as a sheet.

"Just drop that fleece on the desk there; if you please," said Bob very coolly.

He laid it down without saying a word, never once taking his eyes off the revolver.

"You may go now," Bob said. "You can't get any fleece out of this office."

"Put up that gun. You are making a fool of yourself," said Bryant finally.

"Maybe I am. All the same, I'd have made a corpse of you if you had not dropped that wool."

"What have you got my name on it for?"

"I am having a little fun out of it–that's all."

"You have no right to use my name at all."

"Maybe I haven't. Go to law about it, and let the court decide that question. I am going to keep it there, for you are the meanest man in Wall Street. You had a messenger boy discharged from his position of five dollars a week. It will be a long time before I can have fun enough with you to satisfy me, Mr. Bryant."

"I did not have you discharged."

"Oh, that's all right."

"But you can ask Manson."

"Yes, I know. We got more of his fleece than we did of yours. I haven't had much fun with him yet. One at a time and it will last longer."

"You must take my name off that thing there."

"Not at your command I won't."

"Well, I'll see about it," and he turned and went out.

Fred and those in the main office were not aware of what had been going on between Bob and Bryant in the private office.

"What did he say, Bob?" Fred asked.

Bob told him what had passed between the broker and himself, adding:

"He is the maddest man on earth. I am getting even with him, and am going to run that fleece business till some court tells me to stop it."

"By George," exclaimed Fred, "if he goes to law about it we'll be the best advertised firm in the Street."

"That's so," remarked Allison, his broad face wreathed in smiles. "He is a strong man–has many friends; but Wall Street brokers are always ready to shear each other."

"Of course they are. Business knows no friendship. It is merciless in its operations."

Allison looked at him in no little surprise. Such a hard, cynical view of business coming from one so young almost startled him.

"Where did you pick up that idea?" he asked Fred.

"In the Stock Exchange when I was a messenger boy," was the reply.

"Who gave it to you?"

"Nobody. I got the idea from what I saw going on all around me."

"Well, you have observed closely, young man. It's a harsh judgment, but correct in the main. I hope, though, that in your success you will not forget those who are unfortunate."

"I hope so, too, Mr. Allison. It is not my nature to be mean or stingy. Bob gave the old beggar with the red shawl a dollar yesterday."

"He did, eh?"

"Yes, sir. She's sixty if a day."

"Yes, and has been begging in Wall Street for twenty years. I'd wager a month's salary she has ten thousand dollars in bank and owns real estate somewhere on Manhattan island."

"What are you giving me?" and Fred looked the picture of incredulity.

"The straight truth. I have a nephew in a little east side bank above Grand street, and he says she has a fat account there, and that he has seen three other bank books in her possession."

"Well, I'll be hanged!" exclaimed Fred. "I thought I knew a thing or two, but that yarn jiggers me."

The old man laughed and was going to say more when a crowd of boys came in. Business had closed for the day, and every messenger boy in Wall and Broad streets had made a rush to see Fred and Bob in their new role as bankers. Boothblacks and newsboys were among them, and they made the welkin ring with their shouts.

"Say, give us a loan, Bob."

"Cash a check for me, Fred."

"How much chink have you got, boys?"

"Where did you break in, Fred?"

"How much did you get?"

"Where were the cops?"

"Ah, let up on that, cullies!" sung out Fred. "Come by to-morrow at this time and get a ticket for a square meal. It's none of your business where we got it. We've got it and that's enough."

They gave Halsey & Company three cheers and left. Just an they were about to close the doors Callie Ketcham came in.

"Oh, my, what a grand place it is, Fred!" she exclaimed, as she looked around the place. "Promise me a situation when you need a typewriter."

"Indeed I won't!" he replied.

"Why?" and she looked at him in surprise.

"Tips!" he whispered.

She laughed and exclaimed:

"Oh, yes, I see!"

"Besides, if you were here all the time I'd do very little business, I fear."

"Oh, that's some of your talk again. Have you any depositors?"

"No. Just opened to-day."

"May I be one of your depositors?"

"Of course, if you wish. Mr. Allison is the cashier," and he introduced the old man to her.

"Give me a check, please," she said, and when she got it she filled it out for $10,000, handed it to the old man, saying:

"I am your first depositor, and am so glad to know it."

"I'll send you a book to-morrow," he said, as he put it away.

"No, don't send it; I'll call for it myself," she replied.

"Very well, Miss Ketcham."

The old cashier was knocked topsy-turvy at receiving a check for such a sum from a young typewriter. As they were going out Gertie Clayton came by and said:

"They told me you had opened a bank here, Bob, and I wanted to see if it was true," and she looked up at the sign on the big plate glass front.

Callie caught her hand, kissed her as girls do, and said:

"Oh, Gertie, it's just too grand for anything in there! Would you believe it, I am the first depositor on their books!"

"I wish I could put money in the bank, but I can't. It takes all I can make to keep a roof over our heads."

"Why don't you strike old Bowles for a raise in your salary?" Bob asked her.

"It is useless. He told me to-day he would not want me after this week."

"The deuce he did! What's the matter?" Bob blurted out.

"I am sure I don't know. He has never found fault with my work, He said I could go back to Bryant's, as he had said I could always find a place there."

"Well, don't you go there," said Bob. "I'll see if I can't find another place for you."

"I am such a trouble to you, Bob."

"Indeed you are not."

Fred and Callie had gone on ahead, and Bob walked with Gertie. They passed Broker Bryant on Broadway, and Gertie gave a shudder as she saw him, saying to Bob:

"I am afraid of that man. He looks at me sometimes as though he wanted to kill me."

"He is bad enough to do it," Bob said. "He hates me like poison, and would poison me if he could."

"I believe he paid Mr. Bowles to discharge me."

"Why, what good would that do him?"

"He thinks I'll go back to his office if I can't get a place anywhere else."

"Well, if you can't get a place, you can have deskroom with us and do chance work. You must not go back to him," and Bob was very earnest in his way as he spoke.

Bob saw her to her home and then hastened to his own humble domicile. When he got there he found the sidewalk in front of the tenement piled up with furniture. Two families were being ejected for non-payment of rent–$9 each. The landlord was there directing the officers. Bob looked on for a few minutes, and then quietly handed a ten-dollar bill to each of the two mothers, saying:

"Go across the street and get rooms. You can get 'em for $8 over there."

They both sprang up and showered blessings on his head and curses at the landlord.

One day a week later Bob received a tip from Gertie Clayton that Rock Island shares were going to be cornered. Bob saw Fred about it and they watched Rock Island. Pretty soon they saw it advance. Then Fred ordered 15,000 shares bought for the firm. The next day a man called and asked them to lend him $10,000 on a good stock worth double that amount. Fred asked to see the stock. It was K. & T. Fred took the stock to Mr. Allison for his advice, and the bookkeeper denounced the stock as a clever forgery. When the man heard that he made a snatch for the paper, missed it, and then made a break for the door. Fred darted across his path and upset him near the door. He fell heavily, striking the plate glass and shattering it.

"I'm a dead man!" he gasped, rolling over on the floor, the blood spurting from a cut on the side of his head.

When Fred saw the red stream spurt from the man's neck he sprang back and exclaimed:

"It was the glass!"

Bob ran out from another room. So did the clerk, and Mr. Allison came around from behind the cashier's desk. Others who heard the glass rattle down on the sidewalk ran in to see what had happened.

"The man is bleeding to death!" cried some one. "Send for a doctor!"

"Call an ambulance!" said somebody, and both were summoned.

But ere either could get there the man was dead. The broken glass had cut a jugular vein and his life ebbed away inside of three minutes. A policeman ran in when he saw the crowd before the bank.

"How did it happen?" he asked.

"He fell against the glass and it cut his neck," replied the clerk.

"Did you see it?"

"Yes."

"Then I want you to go with me and tell the story to the coroner.

"We'll all do that," said Allison.

"Did you see it, too?"

"Yes."

"Then I want you, too."

"Very well."

The doctor who had been summoned came in and examined the wound.

"The jugular is severed," he said. "No power on earth could have saved him."

"Who was he?" the officer asked.

Nobody answered him.

"Does no one in this crowd recognize him?"

They gazed at the dead man, but none knew him.

"Who sent for me?" the doctor asked, looking around.

No one answered him.

"Who pays my fee?"

"You ought to know who told you about it," said the officer.

"Somebody called up to my window to come quick. I didn't see him."

"Doctor, I'll pay the bill," said Fred, "as long as it happened in here."

"Very well. Ten dollars, please," and the doctor held out his hand for the money.

Fred handed it to him, saying:

"Be kind enough to get out. You're a hog on two legs."

"What!" and the doctor gasped as if for breath.

"Get out of here, you old hog!" repeated Fred.

The doctor struck at him, his face livid with rage. The officer caught him by the arm, saying:

"If you raise a disturbance here I shall have to arrest you, sir."

"Did you hear him insult me?" cried the doctor.

"Yes, but you can't fight here."

"If he wants to fight, let him fight a man of his size, not a boy," said a broker in the crowd. "He is a hog, judging from his actions, and I am ready to back it up!"

"I'll sue you for slander!" hissed the doctor, as he made his way through the crowd.

"Sue and be hanged to you! You are a coward as well as a hog!" and the belligerent broker followed him out to the sidewalk.

The doctor got away in the crowd. The ambulance came, and the body was removed to the police station to await identification and the action of the coroner. The doors of the bank were closed, and a number of brokers remained inside to find out how the thing had happened. Mr. Allison related how it occurred, and produced the certificate, which they all examined. But not one of them was willing to say it was a forgery. The old man was the best posted of them all.

"I would have loaned him $20,000 on that," said a well-known broker as he examined it.

"You would have lost every penny of it, sir," replied Allison.

"Do you wish to wager anything on it?" the broker asked.

"I have no money to put up."

"Make the bet–I'll put up the money," said Bob. "I am willing to bet on you."

"Very well, I'll wager $10,000 that this is a forgery, that the company has never issued a 'Third series' of shares."

"Put up the money," said the broker. "I'll give my check. It can't be certified now, since the bank is closed."

"You won't stop it if you lose, eh?" Bob asked.

"No, not I."

"Very well, Mr. Allison, put up the money in the hands of any one you know."

The old man put up the money and Broker Dean put up his cheek.

"Now let's go to Doggett & Holmes' office and see what they say about it. They are the attorneys for the road and ought to know all about it," Allison said, and the whole party of about a dozen men went out and down on Broad street, where they soon climbed up three flights to the law offices of Doggett & Holmes.

Holmes was in. Doggett had left. He examined the certificate and pronounced it a forgery, saying:

"No 'Third series' has ever been issued by the company."

"Whoop!" yelled Bob, "I'll bet on my old man every time!"

The crowd roared and Dean was nettled.

"I want to have the statement of the president of the company before I give up," he said.

"Will the treasurer of the company do?" Holmes asked.

"Yes, of course."

"Well, he is here," and he sent a clerk into another room for a Mr. Timson, the treasurer of the company.

He came out and very promptly pronounced it a forgery.

"Whoop!" yelled Bob again. "Halsey & Company are bankers and speculators, and sometimes they bet on a dead sure thing. Say, Fred, we've got some more fleece to hang up."

The brokers yelled and Dean said to him:

"See here now, boys, none of that. If you get any of my fleece in a deal you can hang it up on your front door. This is quite a different thing."

"But do you give it up?" Bob asked.

"Oh, yes. You can have the money."

"All right. We can't call it fleece at all. Mr. Allison, one-half is yours. Shake, old man."

Allison jumped as though he had been shot.

"Do you mean that, Bob?" he asked.

"Of course I do."

"And you–is it all right?" he asked of Fred.

"Of course it is. You saved us $10,000, didn't you?"

"Well, that was my duty. I've been thirty-three years in Wall Street and never had so much consideration shown me before," and his eyes became moist and his voice husky.

"I say, boys!" called out another broker, "let's all go and dine together and have a bottle for each plate. I like these two boys and think we can learn something from them. Come on, every one of you."

They all laughed, shook hands with Bob, Fred and Allison and went downstairs and farther down the street to a well-known restaurant. There they had a royal feast for an hour. Dean became quite merry over his bottle and admitted that he knew Allison was one of the best posted men in the street, and was glad that he was to have one-half the amount he had lost. At that dinner the brokers became acquainted with Halsey & Company, and found that, though they were boys, they knew a good deal about taking care of Number One.

The accident in the banking house of Halsey & Company, by which a man lost his life, created a good deal of excitement in Wall Street. The prompt discovery of the forgery had the effect of convincing the Street that they were not to be victimized even if they were a couple of boys not yet out of their teens. The janitor of the building very promptly removed the blood stains and a glazier put up another glass in place of the one that was broken. The bank bad not been open an hour ere a carriage drove up in front and a tall, gray-haired man alighted and went in.

"Ah, you are Mr. Gaines!" said Fred, on seeing him. "Come into the little office and sit down. I am very glad to see you out again."

"Thank you, my young friend," said the old gentleman, following him into a little office and seating himself in a comfortable arm-chair. "I have called to thank you in person for the kind service you rendered me in the Stock Exchange that day. You saved my life!"

"Mr. Gaines, I am glad I was able to do as I did," said Fred. "You sent me a watch and chain, which I prize very highly. I am sure I don't deserve any more credit than what you have already given me."

"Well, I want to show my gratitude, for it is a pleasure to do so. Who is your broker in the Exchange now?"

"We have no regular broker. We have engaged a different one for each deal we have made."

"Would you like to have a seat there yourself?"

"Yes, sir, but I am too young, I guess."

"There is no limit as to age. If you are able to buy a seat you can have one."

"But a seat is worth $30,000."

"Yes. I have a seat. I am never going to use it again. I was badly squeezed that day in the Exchange, and lost many thousands of dollars. But I have enough to live and die on, and so intend to sell my seat. If you can pay $5,000 cash you can pay the balance in five years–$5,000 a year."

"I'll take it," said Fred.

"Very well. I can get $30,000 in cold cash for it, but don't care to let the man have it at any price."

Fred gave him the money and the seat was duly transferred.

"I wish you all the success in the world, my good friend," said the old man, rising and extending his hand to Fred.

"Thank you, sir. I am deeply grateful to you for this favor. May I ask you a question?"

"Yes, as many as you please," replied the old man, resuming his seat. "What is it?"

"Is Mrs. Bryant a relative of yours?"

"Yes. She is my niece. Why?"

"Mr. Bryant and I don't love each other much, and I heard the other day of your relationship to his wife. I didn't believe it."

"Yes, it's true. I heard you had some wool hung up and labeled 'Bryant's fleece.' Is it true?"

"Yes," and Fred laughed. "I'll show it to you," and he did.

"Bryant has been very sore over it, and so has his wife. I would advise you to take it down."

"I shall advise Bob to do so. It is his fight, you know."

"Yes, so I heard. Well, good-by. I shall drop in when I come downtown. I have no office now."

"Oh, you must make this your office!" exclaimed Fred; "we have plenty of room, for we don't do much business as yet. Our rent is paid up for one year."

"Well, I guess that's more, than any other firm in Wall Street can say," and he shook Fred's hand. "I shall be glad to accept your offer, though I shall not come down often."

He went out and Fred told old Allison that he had bought Gaines' seat in the Stock Exchange. The old cashier glared in astonishment, saying:

"I'm afraid that you will make a mistake in going in there."

"Why?"

"People get excited there and lose both their heads and fortunes in a very few minutes."

"Yes, I know. But I got used to that sort of thing when I was a messenger. It is not new to me."

Broker Gaines had not been gone ten minutes ere Gertie Clayton came in. She had a frightened look in her face. Bob met her, and she said:

"Oh, I saw it in the papers about the man being killed by the broken glass. It's awful, isn't it?"

"Yes, indeed. Come to the ladies' room if you have any time to spare," said Bob, who saw that something had happened.

She followed him, and in the cozy little parlor said to him:

"I can't go back to Mr. Bowles office any more, Bob."

"Why not?"