The Project Gutenberg EBook of Derrick Sterling, by Kirk Monroe

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Derrick Sterling

A Story of the Mines

Author: Kirk Monroe

Release Date: June 19, 2007 [EBook #21863]

[Last updated on October 24, 2007]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DERRICK STERLING ***

Produced by David Edwards, Brett Fishburne, Mary Meehan

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

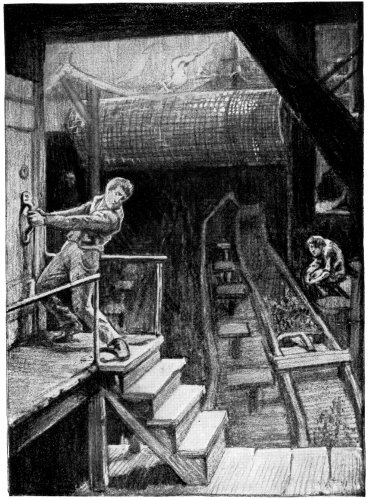

In the burning breaker.

CHAPTER I. In the Burning Breaker

CHAPTER II. A Fearful Ride

CHAPTER III. The Mine Boss Takes Derrick into his Confidence

CHAPTER IV. Introducing Harry, the Bumping-mule

CHAPTER V. Attacked by Enemies, and Lost in the Mine

CHAPTER VI. The Secret Meeting.—A Plunge down an Air shaft

CHAPTER VII. A Cripple's Brave Deed

CHAPTER VIII. Derrick Sterling's Splendid Revenge

CHAPTER IX. Socrates, the Wise Mine Rat

CHAPTER X. In the Old Workings.—Misled by an Altered Line

CHAPTER XI. A Fatal Explosion of Fire-damp

CHAPTER XII. The Mine Boss in a Dilemma

CHAPTER XIII. Ladies in the Mine.—Harry Mule's Sad Mishap

CHAPTER XIV. A Life is Saved and Derrick is Promoted

CHAPTER XV. A "Squeeze" and a Fall of Rock

CHAPTER XVI. Bursting of an Underground Reservoir

CHAPTER XVII. Imprisoned in the Flooded Mine

CHAPTER XVIII. To the Rescue!—A Message from the Prisoners

CHAPTER XIX. Restored to Daylight

CHAPTER XX. Good-by to the Colliery

"Here, lad, lead this mule down the rest of the way, will ye?"

Suddenly there came a blinding flash, a roar as of a cannon

"Fire! Fire in the breaker! Oh, the boys! the poor boys!" These cries, and many like them—wild, heartrending, and full of fear—were heard on all sides. They served to empty the houses, and the one street of the little mining village of Raven Brook was quickly filled with excited people.

It was late in the afternoon of a hot summer's day, and the white-faced miners of the night shift were just leaving their homes. Some of them, with lunch-pails and water-cans slung over their shoulders by light iron chains, were gathered about the mouth of the slope, prepared to descend into the dark underground depths where they toiled. The wives of the day shift men, some of whom, black as negroes with coal-dust, powder-smoke, and soot, had already been drawn up the long slope, were busy preparing supper. From the mountainous piles of refuse, of "culm," barefooted children, nearly as black as their miner fathers, were tramping homeward with burdens of coal that they had gleaned from the waste. High above the village, sharply outlined against the western sky, towered the huge, black bulk of the breaker.

The clang of its machinery had suddenly ceased, though the shutting-down whistle had not yet sounded. From its many windows poured volumes of smoke, more dense than the clouds of coal-dust with which they were generally filled, and little tongues of red flame were licking its weather-beaten timbers. It was an old breaker that had been in use many years, and within a few days it would have been abandoned for the new one, recently built on the opposite side of the valley. It was still in operation, however, and within its grimy walls a hundred boys had sat beside the noisy coal chutes all through that summer's day, picking out bits of slate and tossing them into the waste-bins. From early morning they had breathed the dust-laden air, and in cramped positions had sorted the shallow streams of coal that constantly flowed down from the crushers and screens above. Most of them were between ten and fourteen years of age, though there were a few who were even younger than ten, and some who were more than sixteen years old.[1]

Among these breaker boys two were particularly noticeable, although they were just as black and grimy as the others, and were doing exactly the same work. The elder of these, Derrick Sterling, was a manly-looking fellow, whose face, in spite of its coating of coal-dust, expressed energy, determination, and a quicker intelligence than that of any of his young companions. He was the only son of Gilbert Sterling, who had been one of the mining engineers connected with the Raven Brook Colliery. The father had been disabled by an accident in the mines, and after lingering for more than a year, had died a few months before the date of this story, leaving a wife and two children, Derrick and little Helen.

For nearly five years before his father's death Derrick had attended a boarding-school near Philadelphia; but the sad event made a vast difference in his prospects for life, and compelled his return to the colliery village that he called home.

Mr. Sterling had always lived up to his moderate income, and though his salary was continued to the time of his death, the family then found themselves confronted by extreme poverty. They owned their little vine-covered cottage, at one end of the straggling village street, and in this Mrs. Sterling began to take boarders, with the hope of thus supporting her children. Her struggle was a hard one, and when one of the boarders, who was superintendent of the breaker, or "breaker boss," offered Derrick employment in his department, the boy was so anxious to help his mother that he gladly accepted the offer. Nothing else seemed open to him, and anything was better than idleness. So, after winning a reluctant consent from his mother, Derrick began to earn thirty-five cents a day, at that hardest and most monotonous of all forms of youthful labor, picking slate in a coal-breaker.

He had been brought up and educated so differently from any of his companions of the chutes that the life was infinitely harder for him than for them. He hated dirt, and loved to be nice and clean, which nobody could be for a minute in the breaker. He also loved the sunlight, the fields, and the woods; but no sunshine ever penetrated the thick dust-clouds within these walls. In the summer-time it shone fierce and hot on the long sloping roof, just above the boys' heads, until the interior was like an oven, and in winter they were chilled by the cold winds that blew in through the ever-open windows.

Here, and under these conditions, Derrick must work from seven o'clock in the morning until six in the evening. At noon the boys were allowed forty minutes in which to eat the luncheons brought in their little tin pails, and draw a few breaths of fresh air. During the first few weeks of this life there were times when it seemed to Derrick that he could not bear it any longer. More than once, as he sat beside the rattling chute, mechanically sorting the never-ending stream, with hands cut and bruised by the sharp slate, great tears rolled down his grimy cheeks. Over and over again had he been tempted to rush from the breaker, never to return to it; but each time he had seemed to see the patient face of his hard-working mother, or to feel the clinging arms of little Helen about his neck. He would remember how they were depending on his two dollars a week, and, instead of running away, would turn again to his work with a new energy, determined that, since he was to be a breaker boy, he would be the best in the colliery.

In this he had succeeded so well as to win praise, even from Mr. Guffy, the breaker boss, who usually had nothing but harsh words and blows for the boys who came under his rule. He had also been noticed by the superintendent of the colliery, and promised a place in the mine as soon as a vacancy should occur that he could fill. In the breaker he had been promoted from one seat to another, until for several weeks past he had occupied the very last one on the line of his chute. Here he gave the coal its final inspection before it shot down into the bins, from which it was loaded into cars waiting to carry it to cities hundreds of miles away. Above all, Derrick was now receiving the highest wages paid to breaker boys, and was able to hand his mother three big silver dollars every Saturday night.

The first time he did this seemed to him the proudest moment of his life, for, as she kissed him, his mother said that this sum was sufficient to pay all his expenses, that he was now actually supporting himself, and was therefore as independent as any man in the colliery.

It was a wonderful help to him, during the last few weeks of his breaker boy life, to think over these words and to realize that by his own efforts he had become a self-supporting member of society. It really seemed as though he increased in stature twice as fast after that little talk with his mother. At the same time his clothes appeared to shrink from the responsibility of covering an independent man, instead of the boy for whom they had originally been intended.

Beside Derrick Sterling, that hot summer afternoon, sat Paul Evert, a slender, delicate boy with a fine head set above a deformed body. He did not seem much more than half as large as Derrick, though he was but a few months younger, and his great wistful eyes held a frightened look, as of some animal that is hunted. He too had been compelled by poverty to go into the cruel breaker, and try to win from it a few loaves of bread for the many little hungry mouths at home, which the miner father and feeble mother found it so hard to feed.

For a long time the rude boys of Raven Brook had teased and persecuted "Polly Evert," as they called him, on account of his humped back and withered leg, and for a long time Derrick Sterling had been his stanch friend and protector. While the even-tempered lad used every effort to avoid quarrels on his own behalf, he would spring like a young tiger to rescue Paul Evert from his persecutors. Many a time had he stood at bay before a little mob of sooty-faced village boys, and dared them to touch the crippled lad who crouched trembling behind him.

On this very day, during the noon breathing-spell, he had been compelled to thrash Bill Tooley, the village bully, on Paul's behalf. Bill had been a mule-driver in the mine, but had been discharged from there a few days before, and taken into the breaker. He now sat beside Paul, and during the whole morning had steadily tormented him, in spite of the lad's entreaties to be let alone and Derrick's fierce threats from the other side.

That Derrick had not escaped scot-free from the noon-hour encounter was shown by a deep cut on his upper lip. That Bill Tooley had been much more severely punished was evident from the swollen condition of his face, and from the fact that he now worked in sullen silence, without attempting any further annoyance of the hump-backed lad beside him. Only by occasional glances full of hate cast at both Derrick and Paul did he show the true state of his feelings, and indicate the revengeful nature of his thoughts.

This was Paul's first day in the breaker, where he had been given work by the gruff boss only upon Derrick Sterling's earnest entreaty. Derrick had promised that he would initiate his friend into all the details of the business, and look after him generally. He had his doubts concerning Paul's fitness for the work and the terrible life of a breaker boy, and had begged him not to try it.

Paul's pitiful "What else can I do, Derrick? I have got to earn some money somehow," completely silenced him; for he knew only too well that in a colliery there is but one employment open to a boy who cannot drive a mule or find work in the mine. Therefore he had promised to try and secure a place for his crippled friend, and had finally succeeded.

Paul was struggling bravely to finish this long, weary first day's work in a manner that should reflect credit upon his protector; but the hours seemed to drag into weeks, and each minute he feared he should break down entirely. He tried to hide the cruel slate cuts on his hands, nor let Derrick discover how his back ached, and how he was choked by the coal-dust. He even attempted to smile when Derrick spoke to him, though his ear, unaccustomed to the noise of the machinery and the rushing coal, failed to catch what was said.

While the crippled lad, in company with a hundred other boys, was thus anxiously awaiting the welcome sound of the shutting-down whistle, at the first blast of which the torrents of coal would cease to flow, and they would all rush for the stairway that led out-of-doors, the air gradually became filled with something even more stifling than coal-dust—something that choked them and made their eyes smart. It was the pungent smoke of burning wood; and by the time they fully realized its presence the air was thick with it, and to breathe seemed wellnigh impossible. Then, just as the boys were beginning to start from their seats, and cast frightened glances at each other, the machinery stopped; and amid the comparative silence that followed they heard the cry of "Fire!" and the voice of the breaker boss shouting, "Clear out of this, you young rascals! Run for your lives! Don't you see the breaker's afire?"

As he spoke a great burst of flame sprang up one of the waste chutes from the boiler-room beneath them, and with a wild rush the hundred boys made towards the one door-way that led to the open air and safety.

Obeying the impulse of the moment, Derrick sprang toward it with the rest. Before he could reach it a faint cry of "Derrick, oh, Derrick, don't leave me!" caused him to turn and begin a desperate struggle against the mass of boys who surged and crushed behind him. Several times he thought he should be borne through the door-way, but he fought with such fury that he finally won his way back out of the crowd and to where Paul was still sitting.

"Come on, Polly," he cried, "we haven't any time to lose."

"I can't, Derrick," was the answer; "my crutch is gone."

Surely enough, the lame boy's crutch, which had been leaned against the wall behind him, had disappeared, and he was helpless.

At first Derrick thought he would carry him, and made the attempt; but his strength was not equal to the task, and he was forced to set his burden down after taking a few steps towards the door.

He called loudly to the last of the boys, who was just disappearing through the door-way, to come and help him. At the call the boy turned his face towards them. It was that of Bill Tooley, and it bore a grin of malicious triumph.

The next instant the great door swung to with a crash that sounded like a knell in the ears of Derrick Sterling, for he knew that it closed with a powerful spring lock, the key of which was in Mr. Guffy's pocket.

The crash of the closing door was followed by a second burst of flame that came rushing and leaping up the chutes, and above its roar the boys heard shrill voices in the village crying, "Fire! Fire in the breaker!"

As Derrick and Paul realized that they were left alone in the burning breaker, in which the heat was now intense, and that they were cut off from the stairway by the closed and bolted door, they remained for a moment speechless with despair. Then Derrick flung himself furiously against the heavy door again and again, with a vague hope that he might thus force it to give way. His efforts were of no avail, and he only exhausted his strength; for the massive framework did not even tremble beneath the weight of his body.

Still he could not believe but that somebody would open it for them, and he would not leave the door until tiny flames creeping beneath it warned him that the stairway was on fire and that all chances of escape in that direction were gone. He tried to make himself seen and heard at one of the open windows, but was driven back by the swirling smoke. Then he turned to Paul, who still sat quietly where he had been left. The crippled lad had not uttered a single cry of fear, though the eager flames had approached him so closely that he could feel their hot breath, and knew that in another minute the place where he sat would be surrounded by them.

As Derrick sprang to his side, with the intention of dragging him as far as possible from them, he said,

"The slope, Derrick! If we could only get to the top of the slope, couldn't we somehow escape by it?"

"I never thought of it!" cried Derrick. "We might. We'll try anyhow, for if we stay here another minute we shall be roasted to death."

Stooping, he lifted Paul in his lithe young arms, and with a strength born of despair began to carry him up the long and devious way that led to the very top of the lofty building. He had scarcely taken a dozen steps, and was already staggering beneath his burden, when he stumbled and nearly fell over some object lying on the floor. With an exclamation, he set Paul down and picked it up.

It was the crutch, Paul's own crutch; and it was so far above where they had sat at work that it seemed as though it must have been flung there.

The boys did not pause to consider how the crutch came to be where they found it, but joyfully seizing it, Paul used it so effectively that they quickly gained the top of the building and stood at the upper end of the long slope.

It was a framework of massive timbers supported by high trestle-work, that led from the highest point of the breaker down the hill-side into the valley, where it entered the ground. From there it was continued down into the very lowest depths of the mine. On it were double tracks of iron rails, up which, by means of an immensely long and strong wire cable, the laden coal cars were drawn from the bottom of the mine to the top of the breaker. As a loaded car was drawn up, an empty one, on the opposite track, went down. The angle of the slope was as steep as the sharply pitched roof of a house, and its length, from the bottom of the mine to the top of the breaker, was over half a mile.

This particular slope was provided with a peculiar arrangement by which a car loaded with slate or other refuse, after being drawn up from the mine to a point a short distance above the surface, could be run backward over a vertical switch that was lowered into place behind it. This vertical switch would carry it out on the dump or refuse heap. The top of the dump presented a broad, level surface for half a mile, on which was laid a system of tracks. Over these the waste cars were drawn by mules to the very edge of the dump, where their contents were tipped out and allowed to slide down the hill-side. During working hours a boy was stationed at this switch, whose business it was to set it according to the instructions received from a gong near him. This could be struck either from the bottom of the mine or the top of the breaker, by means of a strong wire leading in both directions from it. One stroke on the gong meant to set the switch for the mine, and two strokes to set it for the dump. A flight of rude steps led up along the side of the slope from the mouth of the mine to the top of the breaker.

Derrick and Paul thought that perhaps they might make their way down this flight of steps and thus escape from the blazing building; but when they reached the end of the slope, and looked down, they saw that this would be impossible. Already the steps were on fire, and the whole slope, as far as they could see, was enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke. Through it shot flaming tongues that were greedily licking the timbers of the tall trestle-work.

If Derrick had been alone he would have made the attempt to rush down the steps, and force his way through the barrier of smoke and flame; but he knew that for his companion this would be impossible, and that even to try it meant certain death.

As he hesitated, and turned this way and that, uncertain of what to attempt, an ominous crash from behind, followed by another and another, warned them that the floors of the building were giving way and letting the heavy machinery fall into the roaring furnace beneath. They knew that the walls must quickly follow, and that with them they too must be dragged down into the raging flames.

Paul, sitting on the floor, buried his face in his hands, shutting his eyes upon the surrounding horrors, and prayed.

Derrick stood up, gazing steadily at the rushing flames, and thought with the rapidity of lightning. Suddenly his eye fell upon an empty coal-car standing on the track at the very edge of the slope, and he cried,

"Here's a chance, Paul! and it's our only one. Get into this car, quick as you can. Hurry! I feel the walls shaking."

As Paul clambered into the car in obedience to his friend's instructions, though without an idea of what was about to happen, Derrick sprang to one side, where a brass handle hung from the wall, and pulled it twice with all his might; then back to the car, where he cast off the hooks by which the great wire cable was attached to it. Again he pulled furiously, twice, at the brass handle.

He had done all that lay in his power, and was now about to make one last, terrible effort to escape. The red flames had crept closer and closer, and were now eagerly reaching out their cruel arms towards the boys from all sides. Beneath them the supports of the building tottered, and in another moment it must fall. Down the slope the shining rails of the track disappeared in an impenetrable cloud of smoke, and Derrick could not see whether his signal to the switch-tender had been obeyed or not.

As Paul crouched on the bottom, at one end of the car, his companion said,

"I'm going to push her over and let her go down the slope, Polly. If the trestle hasn't burned away she'll take us through the fire and smoke quick enough. If there's anybody down there and he's heard the gong and set the switch, we'll go flying off over the dump. I guess I can stop her with the brake before she gets to the edge. It's half a mile, you know. If the switch is open, we'll go like a streak down into the mine and be smashed into a million pieces. It won't be any worse than being burned to death, though. Now good-by, old man, if I don't ever see you alive again. Here goes."

"Good-by, dear Derrick."

Then the crippled lad closed his eyes and held his breath in awful expectation. Derrick placed one shoulder against the car, gave a strong push, and, as he felt it move, sprang on one of the bumpers and seized the brake handle that projected a few inches above its side.

In the mean time the two boys had been missed in the village, and as it became known that they were still within the breaker, the entire population, frenzied with excitement, gathered about the blazing building, making vain efforts to discover their whereabouts, that they might attempt a rescue.

No men on earth are braver in time of danger, or more ready to face it in rescuing imperilled comrades, than the miners of the anthracite collieries. Had they known where to find Derrick and Paul, a score of stalwart fellows would willingly have dashed into the flames after them. As it was, no sign that they were still in existence had been discovered, and the spectators of the fire were forced to stand and watch it in all the bitterness of utter helplessness.

One man indeed ran up the blazing stairway, and with a mighty blow from the pick he carried crashed open the door against which Derrick had so vainly flung himself. Only a great burst of flame leaped forth and drove him backward, with his clothing on fire and the hair burned from his face. He was Paul Evert's father.

Upon receipt of the tidings that her boy was shut up in the burning breaker, without any apparent means of escape, Mrs. Sterling had fallen as though dead, and now lay, happily, unconscious of his awful peril. Little Helen sat by her mother's bedside, too stunned and frightened even to cry.

In Paul's home a crowd of wailing women surrounded Mrs. Evert, whose many children clung sobbing to her skirts.

Suddenly two sharp strokes of a gong rang out, loud and clear, above the roar of the flames and the crash of falling timbers. The crowd of anxious spectators heard the sound, and from them arose a mighty, joyous shout. "They're alive! They're alive! They're at the top of the slope!"

But what could be done? The trestle was already blazing, and the upper end of the slope was hidden from the view of those below by dense volumes of ink-black smoke.

Again the gong rang out, "one, two," and one man of all that throng thought he knew what it meant. Springing to the mine entrance, the old breaker boss threw over the switch bar, and set the vertical switch for the dump.

Then came a crash of falling walls, and out of the accompanying burst of fire and smoke, down along the shining track of the slope, shot a thunder-bolt.

It seemed like a thunder-bolt to the awe-stricken spectators, as it rushed out of the flames, leaving a long trail of smoke behind it. In reality it was a coal-car, bearing in one end a crouching figure and a crutch. At the other end stood Derrick Sterling, bareheaded, with rigid form and strained muscles, and with one hand on the brake handle.

With a frightful velocity the car crossed the vertical switch and shot out over the level surface of the dump. Derrick felt the strength of a young giant as he tugged at that brake handle. The wood smoked from the friction as it ground against the wheel; but it did its duty. On the very edge of the dump, half a mile from the vertical switch, the car stopped, and Derrick sat down beside it, sick and exhausted from the terrible nervous strain of the few minutes just past.

It seemed hours since the machinery had stopped in the breaker and the rush of boys had been made for the door-way; but it was barely ten minutes since the first alarm had been given. From the time he stood face to face with death at the top of the slope, and started that car on its downward rush through the flame and smoke, less than two minutes had passed, but they spanned the space between life and death.

As yet Derrick could not realize that they had escaped nor did he until he felt a pair of arms thrown about his neck and heard Paul's voice saying,

"Derrick, dear Derrick! you have saved my life, and as long as it lasts I shall love you. If ever I have a chance to show it, you shall see how dearly."

Then Derrick stood up and looked about him. A crowd of men and boys were running along the top of the dump towards them. In another minute they had both been placed in the car, and amid the joyous cries and exultant cheers it was being rapidly rolled back towards the village.

When Mrs. Sterling began to recover consciousness she smiled at the boy whom she saw standing beside her, and said, faintly,

"I've had an awful dream, Derrick, and I thank God it was only a dream."

And Derrick said, "Amen, mother."

In a mining community serious accidents, and even terrible disasters, are of such frequent occurrence that in Raven Brook the burning of the old breaker soon ceased to furnish a topic of conversation.

It was not until the day after that of the fire that Derrick learned of the presence of mind displayed by the old breaker boss in comprehending his signal on the gong and setting the vertical switch for the dump. As soon as the old man came home that evening, Derrick went to his room prepared to pour out his heartfelt thanks. He had hardly begun when the breaker boss interrupted him with,

"There, that'll do, an' I don't want to hear no more on it. Any fool knows that two gongs means 'dump switch,' an' when one's been in the mines forty year, man an' boy, as I have, he don't take no credit to himself for doing fool's work. When you get older you'll know better'n to mention sich a thing."

"But, Mr. Guffy—"

"That'll do, I tell ye!" roared the irascible old man. "Clear outen here, and go over to Warren Jones's; he wants to see ye. Hold on!" he added, as Derrick was about to leave the room. "On your way stop and tell that hunchback butty[2] of yourn to be on hand in the new breaker at sharp seven to-morrow morning, if he wants to keep his job. Do ye hear?"

As he went out Derrick smiled to think of the old man's pride, which would not allow him to accept thanks or praise from a boy for performing a creditable action.

At the same time the breaker boss was muttering to himself, "He's a fine lad. If he'd 'a' come to grief through any fault of mine I'd never got over it. 'Twon't do, though, to let him see that I think more of him than of any others of the young scoundrels. Boys allus gets so upperty if they thinks you're a-favorin' of 'em. They must be kep' down! Yes, sir! kep' down, boys must be."

Derrick could not help wondering why he too had not been ordered to report at the new breaker the next morning, but thought it better not to ask any questions. After supper he went over to see Mr. Jones, in obedience to the instructions received from the breaker boss.

Warren Jones, the assistant superintendent, or, as he was generally termed, the "mine boss," of the Raven Brook Colliery, was a pleasant-faced, outspoken young man of about thirty. At present he was acting as superintendent, and the burden of responsibility bore heavily upon him. He had a host of warm friends, but had made some bitter enemies among the miners by his direct honesty of purpose and determination to deal out even-handed justice to all over whom he exercised authority. Although generally good-natured and slow to find fault, he could be quick and stern enough when occasion demanded.

Such was the man who greeted Derrick Sterling cordially that evening, showed him into his library, and made him sit down, saying that he wished to have a little talk with him. He spoke in terms of such praise of Derrick's behavior on the previous day as to bring a blush of pleasure to the boy's cheeks.

"By-the-way, Derrick," he asked, "how did the breaker catch fire?"

"I haven't the least idea, sir," answered Derrick, looking up in surprise.

"Oh, all right," said the other, carelessly. "I didn't know but what you might have heard something said about it."

"No, sir, I haven't; that is, not anything that I thought amounted to anything. I have heard some of the boys talking about 'Mollies,' and saying that they beat the world for floods and fires. What are 'Mollies' anyway, Mr. Jones?"

The mine boss looked at him curiously for a moment before replying,

"If you really don't know, it's time you did, for you're likely to see and hear a great deal of them if you decide to make mining your business in life. All that I know about them is this:

"Many years ago a young woman named Mary, or Mollie Maguire, was murdered in Ireland, and several young fellows belonging to an order called 'Ribbonmen' bound themselves by an oath to avenge her death and kill her murderer. They succeeded so well in this undertaking, and escaped detection so easily, that they proceeded to redress other wrongs, real and fancied. They were joined by other men of their own way of thinking, and finally they became a widely spread and powerful society. In course of time, whenever anybody was mysteriously killed in Ireland, it came to be said that the Mollie Maguires had done it, and so the name clung to them.

"At last the murderous order was introduced into this region by some Irish miners who wished to get rid of an objectionable overseer, and also to control the labor unions among the miners. It has so spread that now its members are known to exist in every mining community of the anthracite country. It is one of the most cowardly organizations ever formed by men, and one of the most cruel. Its victims are given no warning of the fate in store for them, but are struck down in the dark, or from an ambush, by unseen hands.

"Often the murderer has no previous acquaintance with, or knowledge of, the man whom he kills. He blindly obeys the command of his infernal order, and is thus made a tool to avenge some petty grievance or fancied injury.

"The Mollies have become a plague-spot that threatens the health and life of this region. It is the duty of every honest man and boy who is brought into any sort of contact with them to thwart their evil designs in every possible way."

"Well," said Derrick, drawing a long breath, "I had no idea that there were such wicked men in this country."

"No," he answered the mine boss, "you are but a boy, and have had but little experience in the wickedness of this world; but I know you are brave, and I believe you to be honest and loyal. I am therefore going to trust you, and tell you something that I had no intention of mentioning when I sent for you this evening. It is this:

"I have every reason to believe the Mollies are strong in this colliery, and that they intend to make trouble here. I have lately received several anonymous letters making demands that cannot possibly be granted, and containing vague threats of what will happen in case they are not satisfied. This morning I found this note pinned to my door."

Here Mr. Jones opened a drawer of his desk, and took from it a dirty sheet of paper, which he handed to Derrick. On it was scrawled the following:

"Bosses take Wornin'. New breakers can burn as well as old. Fires cost munny. Better pay it in wage to

"Mollie."

As the boy finished reading this strange communication which was at the same time an admission and a threat, he looked up in surprise and began, "Then you think, sir—"

"Yes," interrupted the mine boss. "I not only think, but I feel convinced, that the mischief has begun. Moreover, I am determined that it shall end before it goes any further. I am most anxious to discover who is at the bottom of it, and in this I want you to help me."

"Want me to help!" exclaimed Derrick, in astonishment.

"Yes, you," answered Mr. Jones, smiling. "Your very youth and inexperience will render you less likely to be suspected than an older person. I am certain that I can count upon the son of my old friend Gilbert Sterling to perform truly and faithfully any duty which his employers may see fit to intrust him with. Is it not so, Derrick?"

"Yes, sir, it is," cried the boy. "Just tell me what you want me to do, and if I don't succeed it won't be because I haven't tried my best."

"That is just what I expected you to say," remarked the mine boss, quietly. "Now we will lay our first plans. I suppose you have had enough of the breaker, haven't you?"

"Indeed I have, sir."

"Very well. For a change I am going to offer you a job in the mine where I will give you a bumping-mule to drive. Your wages will be five dollars a week."

"A bumping-mule?" queried Derrick, in a tone of perplexity not unmixed with disappointment. From the preceding conversation he had expected to be intrusted with something very different from mule-driving; nor had he any idea what sort of an animal the one in question might be.

This time Mr. Jones not only smiled but laughed outright; for, from the boy's face and tone, he easily understood what was passing in his mind.

"A bumping-mule," he explained, "is the animal that draws the loaded coal-cars from the chambers, or breasts, to where they are made up into trains. These trains are then hauled by a team of mules to the foot of the slope. Then, when the empty cars are brought back, the bumping-mule distributes them to the several places where they are required. I suppose his title comes from his causing the cars to bump together as he makes them up into trains. In attending to your duties as driver of this most important mule, I can assure you that your time will be fully occupied from the minute you go into the mine until you leave it.

"I suppose," he added, with a humorous twinkle in his eyes, "that our conversation led you to think you were to be appointed 'air boss' of the mine, or placed in charge of a gang at the very least?"

"No, sir," answered Derrick, a little hesitatingly; "I ain't quite such a greeny as that. But I don't see how I can help you very much by just driving a bumping-mule."

"You can help me in two ways: first, by doing your duty so faithfully that I may be able to depend on you at all times; second, while I am in doubt as to whom I may trust, it will be of great assistance to me to know that there is at least one person constantly in the mine who will be true to the interests of his employers, and on the alert to detect any attempt to injure them."

"I hope you don't mean that I am to be a spy in the mine, sir?"

"No, my boy, I do not. I want you to attend strictly to your duties as driver of a bumping-mule. At the same time I want you to consider that your eyes and ears are acting in the place of my eyes and ears. If at any time they see or hear anything which according to your best judgment I ought to know, I hope you will be man enough to tell me of it."

"Well, sir," answered Derrick, "I am glad of a chance to go into the mine and to earn five dollars a week. If you will let me do whatever I think is right about telling you things without making any promises, I will keep my eyes and ears wide open."

"That is all that I want you to do, my boy."

"All right, sir, then I'll do my best; and I hope I sha'n't have anything to tell you except about the bumping-mule."

"So do I hope so with all my heart, Derrick," said the mine boss, gravely; "for I am inclined to think that if you have anything else to tell me it will be something very serious and unpleasant. Now you may take this order for a pair of rubber boots and a miner's cap and lamp over to the store and get the things. Be on hand to go down with the first gang of the morning shift. You will find me in the mine, and I will see that you are properly set to work. Good-night."

"Good-night," answered Derrick, as, with the store order in his hand, and his mind full of conflicting emotions, he left the house.

Several miners of the day shift were in the store when Derrick went to present his order. By questioning him as to what he wanted with mine clothes, they soon learned that he was to begin life underground the next day as driver of a bumping-mule.

"De young bantam'll find it a tougher job than riding empty cars down de slope," sneered one big ugly-looking fellow, whose name was Monk Tooley, and who was Bill Tooley's father.

"I reckon you've laid in a big supply of cuss-words as a stock in trade! Eh, lad?" asked another.

"No, I haven't," said Derrick, flushing hotly. "I don't believe in swearing, and if I can't drive a mule without it I won't drive him at all."

"Then I reckon you'll hunt some other business putty quick," answered the miner with a coarse laugh in which the others joined. "Mules won't work without they hears the peculiar langwidge they's most fond of."

"Well," said Derrick, "we'll see." And leaving the store with his purchases he started homeward. On the way he stopped to deliver Mr. Guffy's message to Paul Evert, and to tell his friend the great news that on the following day he was to begin the life of a miner.

"I wish I was going with you," said Paul.

"I wish you were, Polly," answered Derrick. "Perhaps there will be a chance for you down there before long, and by that time I will have learned all the ropes, and can tell you what's what."

Although Derrick had lived much among collieries, he had never been allowed to go down into a mine. His parents had kept him as much as possible from associating with the rough mine lads of the village. Thus, until he went into the breaker to earn his own living, he had held but slight intercourse with them. His friend Paul, being the son of a miner, knew far more of underground life than he, and often smiled at his ignorance of many of the commonest mine terms.

Derrick was a peculiar boy in one respect. He disliked to ask questions, and would rather spend time and patience in finding out things for himself, if it were possible for him to do so. What he thus learned he never forgot.

He was thoroughly familiar with the surface workings of a colliery, and could explain the construction of the great pumps that kept the mine free from water, the huge, swiftly revolving fan that drew all foul air from it, or any of its other machinery. His father's profession had long seemed to him a most desirable one, and he spent much of his spare time in studying such engineering books as still remained in the house. He loved to pore over his father's tracings and maps of the old workings. With these he had become so well acquainted that he believed he could locate on the surface the exact spots beneath which ran the gangways, headings, and breasts of the abandoned portions of the mine.

By means of these old maps he had also discovered on the mountain side, more than a mile away, the mouth of a drift leading into a vein worked out and abandoned more than twenty years before. This discovery he kept to himself as a precious secret bequeathed to him by his father, though he had not the slightest idea that it would ever be of any practical value to him.

After leaving Paul, Derrick hurried home to tell his mother the great news that he was to work in the mine and earn five dollars a week, and to show her his mine clothes. He was greatly disappointed that instead of rejoicing over his brightening prospects she only gazed at him without speaking, until the tears filled her eyes and rolled down her pale cheeks.

"Why, mother," he said, "aren't you glad? Only think—five dollars a week!"

"Oh, my boy, my boy," she exclaimed, drawing him to her, "I can't let you go down into that horrible place! 'Twas there your father met his death."

"Shall I go back to the breaker, then, mother?"

"No, no; I didn't mean what I said. God has delivered you from one fearful peril, and he can guide you safely through all others. Yes, I am glad, Derrick—glad of any step that you take forward; but oh, my boy, be very careful wherever you go. Remember how precious your life is to me."

Dressed in his new mine clothes, Derrick hurried through breakfast the next morning, and started for the mouth of the slope bright and early.

On his way he met Bill Tooley, who stopped him by calling out, "Look a-here, young feller. They say yer a-going down ter drive my mule."

"Didn't know you had a mule," answered Derrick, pleasantly.

"Well, I did have a mule; an' what's more, I'm going ter have him again. Any feller that goes to driving him before I get back will be sorry he ever done it, that's all. I don't care if he is the bosses' pet, and did take a ride in a hand-car."

As Derrick walked towards the entrance to the mine, he wondered what the bully whom he had just met meant by what he said. He did not then know that Bill Tooley had been discharged from the mine by Mr. Jones for brutal treatment of the mule he had driven, and for general laziness and neglect of his duties.

At the mouth of the "travelling-road," down which the early arrivals were compelled to make their way into the mine, Derrick was greeted by a little group of miners who were lighting their lamps and preparing to descend.

"'Tis bonny to see thee, Derrick lad," called out one of them.

"'Twill be luck to the mine to have such as you in her," said another.

"My lad would ha' been your age an' he'd lived," said a third. "'Twould ha' been a proud day for me to ha' seen him alongside o' thee, lad, lighting his bit lamp, and ready to take up the life of an honest miner."

In the group was Tom Evert, Paul's father, a brawny, muscular man, who was considered one of the best miners in Raven Brook. Taking Derrick a little to one side, he said,

"They tell me, lad, thou'rt to drive Bill Tooley's mule."

"I don't know anything about Bill Tooley's mule," answered Derrick. "I only know that Mr. Jones said I was to drive a bumping-mule, and I intend to do exactly what he tells me."

"Of course, lad, of course; but the bumping-mule he has in mind will be Bill Tooley's, I doubt not, and I'd rather 'twould be another than you had the job. Bill Tooley, with his feyther to back him, is certain to take it out, some way or another, of the lad that steps into his place."

"I'm not afraid of Bill Tooley, as you ought to know, Mr. Evert," said Derrick, somewhat boastfully, as he thought of the thrashing he had so recently given the young man in question.

"Of course not, lad, of course not. I know you can lick him fast enough in fair fight. My poor little Paul can bear ready witness to that, for which I'm under obligations to you. It's not fair fighting I mean; for when it comes to argyfying with them Tooleys, it's foul play you must look out for; and what the young un lacks in pluck he makes up in inflooence."

Derrick was about to ask what he meant, but was interrupted by a movement of the miners towards the entrance. In another moment he found himself rapidly descending the steep steps of the travelling-road, and feeling that the attempt to keep pace with the long-limbed fellows ahead of him must certainly result in his pitching headlong into the unknown depth of blackness.

The travelling-road was a gigantic stairway, leading at a steep angle directly down into the earth. It was high enough for a man to stand upright in without hitting his head against the roof, and it was provided with steps. They were cut or dug out of the rock, earth, or coal down through which the road passed, and were very broad and very high. The front edge of each was formed of a smooth round log. From the roof and sides of the road dripped and trickled little streams of water that made everything in it wet and soggy, and rendered the edges of the steps particularly slippery.

The air in the road was chilly in comparison with that of the warm summer's morning in which the outside world was rejoicing, and Derrick shivered as he first encountered its penetrating dampness. Of course the darkness was intense, but at first it was partially dispelled by the lights of the half-dozen miners in whose company he had entered the road. As they gradually left him behind, their twinkling lights grew fainter and fainter, until at last they vanished entirely, and Derrick found himself stumbling alone down the apparently interminable stairway.

While yet in company with the miners, he had passed through one door made of heavy planks, that completely closed the road, and now he came to another. Through its chinks and cracks there was a rush of air from outside inward that hummed and whistled like a small gale. It took all of Derrick's strength to pull this door open, and it closed behind him with a crash that reverberated in long, hollow echoes down the black depths before him.

Some distance below he was startled by a heavy booming sound from above, which was followed by a tremendous clattering, mingled with shouts and cries. In the first of these sounds he recognized the closing of the door through which he had recently passed, but he could not account for the others.

They were continued, and grew louder and louder as they approached, until at length they were close at hand, and he saw lights and a confused mass of struggling forms directly above him. Stepping to one side, Derrick flattened himself against the wall to let them pass; but just as the miner who came first reached that point, he tossed the end of a rope into the boy's hands, saying, "Here, lad, lead this mule down the rest of the way, will ye? I'm in a powerful hurry myself."

"Here, lad, lead this mule down the rest of the way, will ye?"

In another instant he had gone, leaping with immense strides down the precipitous steps, and Derrick found himself staring into the comical face of a large mule which, with his fore-feet on one step and his hind ones on that above, looked as though he were about to stand on his head.

"Go on, can't yer!" called out an impatient voice from behind the mule. "Do ye think I can hang onto this 'ere blessed tail all day? A mule's no feather-weight, let me tell yer."

Then Derrick realized that another man held the mule by the tail, and was exerting all his strength to prevent him from going down too fast. Accepting the situation, he started ahead, encouraging the mule to follow; but this arrangement did not seem to suit the animal, for he refused to budge a step from where he stood, nor could the man in the rear push him along.

"Here, you!" the man called out to Derrick, "come back here and steer him while I take his head. When he gets started, hang on to his tail with all your might, and hold back all yer can."

So they changed places, and the mule was so greatly pleased at having got his own way that he began to plunge down the stairs with great rapidity. Derrick felt almost as though he were being rushed through space on the tail of a comet, and shuddered to think of the broken limbs and general destruction that must inevitably follow such reckless travelling. The mule, however, seemed to know what he was about as well as the man who led him, and took such good care of himself that Derrick soon plucked up courage, and even began to enjoy the situation.

As he was thinking that they must be somewhere near the centre of the earth, the mule gave an unusually violent plunge forward, and then stopped so suddenly that poor Derrick found himself sprawling on the animal's back, with both arms clasped tightly about his neck. With this the mule began to caper and shake himself so violently that the boy was forced to loose his hold and fall to the ground, amid roars of laughter from a score of miners who witnessed the scene.

Greatly confused, Derrick scrambled to his feet, gave a reproachful glance at the mule, which was calmly gazing at him with a wondering look in his wide-open eyes, and turned to see in what sort of a place he had been so unceremoniously landed. At the same moment Mr. Jones, dressed in miner's costume, and looking as grimy as any of the others, stepped from the laughing group and said,

"My boy, I congratulate you on being the first person who ever rode into this mine on mule-back, I am glad you found the travelling-road so good. Came on your own mule too. How did you know this was the bumping-mule you were to drive?"

"I didn't know what sort of a mule he was until just as we got here and he bumped me off his back," replied Derrick; "and I begin to think that he knows more about driving than I do."

"Well, you have made a notable beginning," said the mine boss, "and I am sure you two will get along capitally together. Harry Mule, this is Derrick Sterling, who is to be your new driver, and I want you to behave yourself with him." Then to Derrick he said, "Harry has the reputation of being the most knowing, and at the same time the most perverse, mule in the mine. I believe though he only shows bad temper to those who abuse him, and I have selected you to be his driver because I know you will treat him kindly, and give him a chance to recover his lost reputation. If he does not behave himself with you, I shall put him in the tread-mill. Now stand there out of the way for a few minutes, and then I will show you where you are to work."

Derrick did as he was directed, and quickly found himself intensely interested in the strange and busy scene before him. The travelling-road entered the mine in a large chamber close beside the foot of the slope that led upward to the new breaker. From this chamber branched several galleries, or "gangways," in which were laid railway-tracks. Over these, trains of loaded and empty coal-cars drawn by mules were constantly coming and going. By the side of the track in each gangway was a ditch containing a stream of ink-black water, flowing towards a central well in one corner of the chamber, from which it was pumped to the surface. Opposite to where he stood, Derrick saw the black, yawning mouth of another slope, which, as he afterwards learned, led down into still lower depths of the mine. The men around him were handling long bars of railroad iron, which they were loading with a great racket on cars, and despatching to distant gangways in which new tracks were needed. Two large reflector lamps in addition to the miners' lamps made the chamber quite bright, and with all its noise and bustle it seemed to Derrick the most interesting place he had ever been in. He was sorry when the mine boss called and told him to bring along his mule and follow him.

They entered one of the gangways, leading from the central chamber, which the mine boss said was known as Gangway No. 1. He also told Derrick something about his mule, and said that by its last driver, Bill Tooley, the poor animal had been so cruelly abused that he had sent it to the surface for a few days to recover from the effects.

"I guess he has recovered," said Derrick, "judging from the way he brought me into the mine."

They had not gone very far before they came to a closed door on one side of the gangway beyond which the mule absolutely refused to go, in spite of all Derrick's coaxings and commands.

"It is the door of his stable," said the mine boss, who stood quietly looking on, without offering any assistance or advice, waiting to see what the boy would do.

Tying the end of the halter to one of the rails of the track on which they were walking, Derrick started into the stable, where he quickly found what he wanted. Coming out with a handful of oats, he let the mule have a little taste of them; and then, loosening the halter, tried to tempt him forward with them. This plan failed, for Harry declined to yield to temptation, and remained immovable. Then Derrick turned a questioning glance upon the mine boss, who said,

"Never again hitch an animal to a track along which cars are liable to come at any moment. Now, why don't you beat the mule?"

"Oh no, sir!" exclaimed Derrick, in distress. "I don't want to do that."

"Neither do I want you to," laughed the other. "I only asked why you didn't?"

"Because," said Derrick, "I want him to become fond of me, and my mother says the most stubborn animals can be conquered by kindness, while beatings only make them worse."

"Which is as true as gospel," said the mine boss. "Well, the only other thing I can suggest is for you to go into the stable, get the harness that hangs on the peg nearest the door, and put it on him."

Acting upon this hint, Derrick had hardly finished buckling the last strap of the harness when the mule began to move steadily forward of his own accord.

"That's his way," said the mine boss. "In harness he knows that he is expected to work, but without it he thinks he may do as he pleases."

Presently the mule stumbled slightly, and again he stopped and refused to go ahead.

"Do you know what is the matter now, sir?" asked Derrick.

"I think perhaps he wants his lamp lighted," replied the mine boss.

A miner's lamp, attached to a broad piece of leather, hung down in front of the mule from his collar.

The boy lighted this lamp, and immediately the mule began to move on, showing that this was exactly what he had wanted.

"Seems to me he knows almost as much as folks," cried Derrick, highly delighted at this new proof of his mule's intelligence.

"Quite as much as most folks, and more than some," answered his companion, dryly.

During their long walk they passed through several doors which, as Derrick was told, served to regulate the currents of air constantly flowing in and out of the mine, and kept in motion by the great fan at its mouth. Whenever they approached one of these the mine boss called, loudly, "Door," and it was immediately opened by a boy who sat behind it and closed it again as soon as they had passed. Each of these boys had besides his little flaring lamp, such as everybody in the mine carried, a can of oil for refilling it, a lunch-pail and a tin water-bottle, and each of them spent from eight to ten hours at his post without leaving it.

Finally Derrick and the mine boss came to a junction of several galleries, a sort of mine cross-roads, and the former was told that this was to be his headquarters, for here was where the trains were made up, and from here the empty cars were distributed. At the farther end of each of the headings leading from this junction two or more miners were at work drilling, blasting, and picking tons of coal from between its enclosing walls of slate. They were all doing their best to fill the cars which it was Derrick's business to haul to the junction and replace with empty ones. There were also a number of miners at work in breasts, or openings at the sides of the gangways that followed the slant of the coal vein, who expected to be supplied with empty cars and have their loaded ones taken away by Derrick. These breast miners filled their cars very quickly, as the moment they loosened the coal it slid down the slaty incline, above which it had been bedded, to a wooden chute on the edge of the gangway that discharged it directly into them.

As Derrick was told of all this, he realized that he and Harry Mule would have to get around pretty fast to attend to these duties, and supply empty cars as they were needed.

What interested him most in this part of the mine was an alcove hewn from solid rock near the junction, in which was a complete smithy. It had forge, anvil, and bellows, and was presided over by a blacksmith named Job Taskar, as ugly a looking fellow, Derrick thought, as he had ever seen. Here the mules were shod, tools were sharpened, and broken iron-work was repaired. It was a busy place, and its glowing forge, together with the showers of sparks with which Job Taskar's lusty blows almost constantly surrounded the anvil, made it appear particularly cheerful and bright amid the all-pervading darkness. Nearly every man and boy in that section of the mine was obliged to visit the smithy at least once during working hours. Thus it became a great news centre, and offered temptations to many of its visitors to linger long after their business was finished.

After pointing out to Derrick the several places at which his services would be required, the mine boss left him, and the boy found himself fully launched on his new career.

He soon discovered that Harry Mule knew much more of the business than he did, and by allowing him to have his own way, and go where he thought best, Derrick got along with very few mistakes. Among the miners upon whom he had to attend he found brawny Tom Evert, stripped to the waist, lying on his side, and working above his head, but bringing down the coal in glistening showers with each sturdy blow of his pick. When he saw Derrick he paused in his work long enough to exchange a cheery greeting with him and to dash the perspiration from his eyes with the back of his grimy hand; then at it he went again with redoubled energy.

At the end of one of the headings Derrick found another acquaintance in the person of Monk Tooley. He scowled when he saw the new driver, and growled out that he'd better look sharp and see to it he was never kept waiting for cars, or it would be the worse for him.

Twice Derrick started to leave this place, and each time the miner called him back on some trivial pretext. The boy could not see, nor did he suspect, what the man was doing, but as he turned away for the third time, Monk Tooley sprang past him with a shout, and ran down the heading. Derrick did not hear what he said, but turning to look behind him, he saw a flash of fire, and had barely time to throw himself face downward, behind his car, when he was stunned by a tremendous explosion. Directly afterwards he was nearly buried beneath an avalanche of rock and coal.

Although Derrick was terribly frightened by the explosion, and considerably bruised by the shower of rocks and coal that followed it, the car had so protected him that he was not seriously hurt. Had his mule started forward the heavily loaded car must have run over and killed him. Fortunately Harry was too experienced a miner to allow such a trifling thing as a blast to disturb his equanimity, especially as the two false starts already made had placed him at some little distance from it. To be sure, he had shaken his head at the flying bits of coal, and had even kicked out viciously at one large piece that fell near his heels. The iron-shod hoof had shattered the big lump, and sent its fragments flying over Derrick, but in the darkness and confusion the boy thought it was only part of the explosion, and was thankful that matters were no worse.

As Derrick cleared himself from the mass of rubbish that had fallen on him, and staggered to his feet, he was nearly suffocated by the dense clouds of powder-smoke from the blast. He was also in utter darkness, both his lamp and that of Harry Mule having been blown out. In his inexperience he had not thought to provide matches before entering the mine, and now he found himself in a darkness more dense than any he had ever dreamed of, without any means of procuring a light. His heart grew heavy within him as he realized his situation, for he had no idea whether the miner who had played so cruel and dangerous a trick upon him would return or not.

An impatient movement on the part of Harry Mule suggested a plan to him. Casting off the chain by which the mule was attached to the car, and holding the end in his hand, he said, "Go on, Harry, and take me out of this place." At this command the intelligent animal started off towards the junction as unhesitatingly as though surrounded by brightest daylight, and Derrick followed.

They had not gone far before they met Monk Tooley, leisurely returning to the scene of his labors.

"Hello! Mr. Mule-driver," he shouted, "what are you a-doing here in de dark, an' how do yer like mining far as ye've got? Been studying de effect of blarsts, and a-testing of 'em by pussunal experience?"

Derrick felt a great lump rising in his throat, and bitter thoughts and words crowded each other closely in his mind. He knew, however, that the man before him was as greatly his superior in wordy strife as in bodily strength, so he simply said,

"The next time you try to kill me you'd better take some surer means of doing it."

"Kill you! Who says I wanted to kill you?" demanded the miner, fiercely, as he stopped and glared at the boy. "Didn't I holler to ye to run? Didn't I give yer fair warnin' that I was shootin' a blarst? Didn't I? Course I did and yer didn't pay no 'tention to it. Oh no, sonny! 'twon't do. Ye mustn't talk 'bout killin' down in dese workin's, cause 'twon't be 'lowed. Come back now, an' git my wagon. Here's a light for yer, but don't let me hear no more talk 'bout killin', or ye may have a chance to wish yer was dead long before yer really is."

Derrick made no reply to this, but turning Harry Mule about, they went back after the car. He was convinced that this man was his bitter and unscrupulous enemy, and made up his mind that he must be constantly on his guard against him. He did not tell anybody of this startling incident of his first day's experience in the mine for a long time afterwards; as, upon thinking it over, he realized that the peril, which he had so happily escaped might readily be charged to his own carelessness.

At lunch time he let Harry Mule make his own way back to the mine stable for oats and water. He had been told by the mine boss that the knowing animal would not only do this, but would afterwards return to his place of duty when started towards it by one of the stable-boys. While the mule was gone, his young driver went into the blacksmith's shop to eat his own lunch in company with Job Taskar, who had invited him to do so. Job questioned Derrick closely as to his acquaintance among the men and boys of the colliery, and asked particularly in regard to his likings or dislikings of the several overseers.

"I hear thee's a great friend o' t' mine boss," said Job.

"Not at all," answered Derrick. "Mr. Jones was a friend of my father's, but I hardly know him."

"All says thee's boss's favorite."

"I'm sure I don't know why they should. Of course it was good of him to give me a job; but he had to get somebody to drive the mule. It doesn't seem to me that I've got any easier place than anybody else."

Here Derrick put one hand up to his badly aching head, which had been bruised by a flying chunk from Monk Tooley's blast.

Noting the movement, Job asked what was the matter, for although he had heard about the blast from Monk Tooley, he wanted to learn what the boy thought of it.

"I got hit by a falling chunk," replied Derrick, guardedly.

"Humph!" growled Job; "better keep clear o' they chunks. One on 'em might hit ye once too often some time."

Job held no more conversation with the boy, but lighted his pipe, and sat at one side of the forge, scowling and smoking. Derrick also kept silence, as he sat on the opposite side of the forge, rubbing his aching head with a grimy hand.

While they sat thus, several miners dropped in for a smoke and a chat. They all looked curiously at Derrick, but none of them spoke to him. Thus neglected, he felt very unhappy and uncomfortable, and was glad when the jingling of Harry Mule's harness outside gave notice that it was again time to go to work.

The rest of the day passed uneventfully and monotonously, for, with the exception of burly Tom Evert, who gave the lad a cheery word whenever he passed him, nobody spoke to him. Even Harry Mule seemed to realize that his young driver was not having a very pleasant time, and rubbed his nose sympathetically against his shoulder, as much as to say, "I'm sorry for you, and I'll stand by you even if nobody else does."

At last, in some mysterious way, everybody seemed to know all at once, that it was time to quit work, and Harry Mule knew it as quickly as anybody. Before Derrick noticed that the miners had stopped work, this remarkable animal, having just been unhitched from a car, threw up his head, uttered a prolonged and ear-rasping bray, and started off on a brisk trot, with a tremendous clatter and jingling of chains, towards his stable.

The door-boys heard him coming, opened their doors to let him pass, closed them after him, and started on a run for the foot of the slope.

Of course Derrick followed his charge as fast as possible, calling, as he ran, "Whoa, Harry! Whoa! Stop that mule, he's running away!" Neither Harry nor anybody else paid the slightest attention to him, and when he finally reached the stable he found his mule already there, exchanging squeals and kicks with several other bumping-mules that had come in from other parts of the mine.

Then he knew that it was really quitting-time, and went to work, as quickly as his inexperience would allow, to rub Harry down, water and feed him, and make him comfortable for the night. Everybody else who had stable-work to do finished it before he, and when at last he felt at liberty to leave the mine and start towards the upper world and the fresh air he longed so ardently to breathe again, he was alone.

Derrick found his way without difficulty to the large chamber at the foot of the slope. There, as he did not see any cars ready to go up, he turned towards the travelling-road, with the intention of climbing the steep stairway he had descended that morning.

Suddenly there arose cries of "There he is! There he is! Head him off!"

Before the startled lad knew what was about to happen, he was surrounded by a score of sooty-faced boys. Cutting him off from the travelling-road, these boys pushed him, in spite of his opposition and protests, into a far corner of the chamber, where, with his back against the wall, he made a stand and demanded what they wanted of him.

"A treat! a treat!" shouted several.

Then room was made for one who seemed to exercise authority over them, and who, as he stepped forward, Derrick recognized with surprise as Bill Tooley, ex-mule driver, and now breaker boy.

"What are you down here for, and what does all this mean, Bill?" asked Derrick, as calmly as he could.

"It means," answered Bill, putting his disagreeable face very close to Derrick's, "dat yer've got ter pay fer comin' down inter de mine, an' fer takin' my mule, when I told yer not ter; dat's what it means. An' it means dat we're goin' ter initerate yer inter de order of 'Young Sleepers,' what every boy in de mine has got ter belong ter."

Derrick had heard of this order of "Young Sleepers," and knew it to be composed of the very worst young rascals in the coal region. He knew that they were up to all kinds of wickedness, and that most of the petty crimes of the community were charged to them. In an instant he made up his mind that he would rather suffer almost anything than become a member of such a gang.

While these thoughts were passing through his mind the cry of "A treat! a treat!" was again raised, and Bill Tooley again addressed Derrick, saying,

"Ter pay yer way inter de mine, de fellers says yer must set up a kag er beer. Ter pay fer drivin' my mule, I say yer got ter take a lickin', an' after that we'll initerate yer."

Now, both Derrick's father and mother had taught him to abhor liquor in every form; so to the boy's first proposition he promptly answered,

"I haven't got any money, and couldn't afford to buy a keg of beer, even if I wanted to. I don't want to, because I'm a blue ribbon, and wouldn't buy even a glass of beer if I had all the money in the world. I won't join your society either, and I don't see how you can initiate me when I don't choose to become a member. As for a licking, it'll take more than you to give it to me, Bill Tooley!"

With these bold words the young mule-driver made a spring at his chief tormenter, in a desperate effort to break through the surrounding group of boys. In the distance he saw the twinkling lights of some miners, and thought if he could only reach them they would afford him protection.

Derrick's defiant speech for an instant paralyzed his hearers with its very boldness; but as he sprang at Bill Tooley they also made a rush at him with howls of anger. He succeeded in hitting their leader one staggering blow, but was quickly overpowered by numbers and flung to the ground, where the young savages beat and kicked him so cruelly that he thought they were about to kill him.

He tried to scream for help, but could not utter a sound, and the miners who passed on their way to the slope thought the fracas was only a quarrel among some of the boys and paid no attention to it.

At length Bill Tooley ordered the boys to cease from pummelling their victim, and stooping over him, tied a dirty cloth over his eyes; then he gave a whispered order, and several of the boys, lifting the helpless lad by his head and feet, bore him away.

After carrying him what seemed to Derrick an interminable distance, and passing through a number of doors, as he could tell by hearing them loudly opened and closed, his bearers suddenly dropped him on the hard ground. Then Bill Tooley's voice said,

"Yer'll lie dere now till yer make up yer mind ter jine de Young Sleepers. Den yer can come an' let me know, an' I'll attend ter yer initeration. Till then yer'll stay where yer are, if it's a thousand years; fer no one'll come a-nigh yer an' yer can't find de way out."

While Bill was thus talking the other boys quietly slipped away. As he finished he also moved off, so softly that Derrick did not hear the sound of his retreating footsteps. It was not until some minutes had passed that he realized that he had been left, and was alone.

Meantime those who had thus abandoned their victim to the horrors of black solitude, in what to him was an unknown part of the mine, were gathered together at no great distance from him. There they waited to gloat over the cries that they hoped he would utter as soon as he realized that he was abandoned. In this they were disappointed, for though they lingered half an hour not a sound did they hear; then two of the boldest among them decided to take a look at their prisoner. Shielding the single lamp that lighted their steps so that its rays should not be seen at any great distance, they crept cautiously to where they had left him.

He was gone!

This had not been expected, and with an ill-defined feeling of dread they hurried back to the others and made their report.

"Oh, well, let him go!" exclaimed Bill Tooley, brutally. "'Twon't hurt him to spend a while in de gangway. Let's go up to supper, and afterwards come down an' hunt him."

As none of them dared to object to any proposal made by the bully, the whole gang of begrimed and evil-minded young savages hurried to the foot of the slope. Here they tumbled into a car, and in a few minutes were drawn up to the surface, where they scattered towards their respective homes and waiting suppers.

Paul Evert, who ever since work had ceased in the breaker, more than an hour before, had lingered near the mouth of the slope, waiting for the appearance of his friend, ventured to ask one of them if he had seen Derrick.

"Don't know nothing about him," was the reply, as, greatly alarmed to find the lad whom he had helped to persecute already made an object of inquiry, the Young Sleeper hurried away.

Bill Tooley had overheard Paul's question, and stepping up to him, he said, "Look a-here, young feller, yer ain't got no call as I knows on to be a meddling wid what goes on in de mine and don't concern you. I don't mind tellin' yer, though, that yer butty's doin' overwork, and mebbe won't come up all night. I heerd one of de bosses orderin' him to it."

Although Paul thought this somewhat strange, he knew that the miners frequently stayed down to do overwork, and was much relieved at such a plausible explanation of his friend's non-appearance. On his way home he stopped to tell Mrs. Sterling what he had heard. He found her very anxious, and just about to go out and make inquiries concerning her boy. The information that Paul brought relieved her mind somewhat, and thanking him for it, she turned back into the house with a sigh, and gave little Helen her supper, at the same time setting aside a liberal portion for Derrick when he should come.

Until nearly ten o'clock she waited, frequently going to the door to look and listen; then she could bear the suspense no longer. Throwing a shawl over her head, and bidding Helen remain where she was for a few minutes, the anxious mother started to go to the house of the mine boss to gain certain information of her boy. As she opened her own front door, something that she saw caused her to utter a cry and stand trembling on the threshold.

What Mrs. Sterling saw was her own son Derrick, who was just about to enter the house. As the light from behind her shone full upon him, he presented a sorry spectacle, and one well calculated to draw forth an exclamation from an anxious mother. Hatless and coatless, his face bruised, swollen, and so covered with blood and coal-dust that its features were almost unrecognizable, he could not well have presented a more striking contrast to the clean, cheerful lad whom she had sent down into the mine with a kiss and a blessing that very morning.

"Why, Derrick!" she exclaimed, the moment she made sure that it was really he. "What has happened to you? has there been an accident? They said you were kept down for overwork. Tell me the worst at once, dear! Are you badly hurt?"

"No, indeed, mother," answered the boy in as cheerful a tone as he could command. "I am not much hurt, only bruised and banged a little by a blast that I carelessly stayed too close to. A little hot water and soap will put me all right again after I've had some supper; but, if you love me, mother, give me something to eat quickly, for I'm most starved."

By this time they were within the house, and as Mrs. Sterling hastened to make ready the supper she had saved for Derrick, he dropped into a chair utterly exhausted. He might well be exhausted, for what he had passed through and suffered since leaving home that morning could not have been borne by a boy of weaker constitution or less strength of will. He was greatly revived by two cups of strong tea and the food set before him. After satisfying his hunger he went to his own room, and took a bath in water as hot as he could bear it, and washed his cuts and bruises with white castile-soap, a piece of which Mrs. Sterling always managed to keep on hand for such emergencies. It was fortunate for her peace of mind that the fond mother did not see the cruel bruises that covered her boy's body from head to foot.

The bath refreshed him so much, and so loosened the joints that were beginning to feel very stiff and painful, that Derrick believed he was able, before going to bed, to perform the one duty still remaining to be done. Mrs. Sterling thought he had gone to bed, and was greatly surprised to see him come from his room fully dressed. When he told her that he must go out again to deliver an important message to the mine boss, she begged him to wait until morning, or at least to let her carry it for him. Assuring her that it was absolutely necessary that he should deliver the message himself that very night, and saying that he would be back within an hour, Derrick kissed his mother and went out.

On the street he met with but one person, a miner hurrying towards the slope, to whom he did not speak, and who he thought did not recognize him.

Mr. Jones had closed his house for the night, and was about to retire, when he was startled by a knock at the outer door. Recent events had rendered him so suspicious and cautious that he stepped to his desk and took from it a revolver, which he held in his hand as he stood near the door, and without opening it, called out,

"Who's there? and what do you want at this time of night?"

As softly as he could, and yet make himself heard, Derrick answered,

"It is I, sir, Derrick Sterling, and I have got something important to tell you."

At this answer a man who had stolen up behind Derrick, unperceived by him in the darkness, slipped away with noiseless but hurried footsteps.

"Is anybody with you?" demanded the mine boss, without opening the door.

"No, sir; I am all alone."

Then the door was cautiously opened, Derrick was bidden to step inside quickly, and it was immediately closed again and bolted. Leading the way into the library, the mine boss said, not unkindly, but somewhat impatiently,

"Well, Sterling, what brings you here at this time of night? working boys should be in bed and asleep before this."