This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Wonder Island Boys: Conquest of the Savages

Author: Roger Thompson Finlay

Release Date: June 14, 2007 [eBook #21832]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS: CONQUEST OF THE SAVAGES***

THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS

By ROGER T. FINLAY

Thrilling adventures by sea and land of two boys and an aged Professor who are cast away on an island with absolutely nothing but their clothing. By gradual and natural stages they succeed in constructing all forms of devices used in the mechanical arts and learn the scientific theories involved in every walk of life. These subjects are all treated in an incidental and natural way in the progress of events, from the most fundamental standpoint without technicalities, and include every department of knowledge. Numerous illustrations accompany the text.

Two thousand things every boy ought to know. Every page

a romance. Every line a fact.

6 titles—60 cents per volume

THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS

The Castaways

THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS

Exploring the Island

THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS

The Mysteries of the Caverns

THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS

The Tribesmen

THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS

The Capture and Pursuit

THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS

The Conquest of the Savages

PUBLISHED BY

THE NEW YORK BOOK COMPANY

147 Fourth Avenue New York

|

The Wonder Island Boys THE CONQUEST OF THE SAVAGES BY ROGER T. FINLAY ILLUSTRATED  N Y B Co.

N Y B Co.

THE NEW YORK BOOK COMPANY New York |

Copyright, 1914, by

THE NEW YORK BOOK COMPANY

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Compact Between the Four Allied Tribes, | Page 11 |

The camp startled by Sutoto. Confederation of the Tuolos, Kurabus and Illyas. A council of all the chiefs. The Professor's address. Advising unity of all the tribes against the hostiles. The assent of the chiefs. The views of Oma, Uraso and Muro. How the allied tribes met. Review of the work of the Professor and the boys. Determine to send a force to the Cataract. Conclude to remove all tools to the southwest. The warriors selected. Adopting a settled plan. Mustering the warriors. Sending for Chief Suros of the Berees. The muster roll. John in command of the forces to the Cataract. Blakely in command of the home forces. The march to protect the Brabos. A compact between the allied tribes. John and his party on the march. Sadness at giving up Cataract. At the Cataract. The flag as a charm. Uraso's interpretation of the flag. |

||

| II. | Busy Times at the Cataract. The Alarming News | Page 24 |

The tribute to the flag. A national talisman. Entertaining the warriors. Starting the water wheel in motion. The sawmill at work. Making spears. Gathering and threshing barley. The roast ox and the feast. Making bread. The surprising novelties for the warriors. Determining to make guns before dismantling. Building a new wagon. Uraso directing the work of the men. The universal tattoo. Its significance. Designating name and rank. Clothing. Blakely drilling the army at the Brabo village. News of the approach of the old chief Suros. The Professor and party receiving him with honor. The conversation with Suros. His hearty accord. Jim and Will. Their observations. The value of unity. Sutoto's report about the confederated tribes. Information of their movement toward Cataract. John's scouts at the Cataract capture two Kurabus. Startling intelligence. Interviewing the captives. Completing the new wagon. Sending out scouts toward the Kurabus. |

||

| III. | Intercepting the March of the Confederates. The Treasure | Page 37 |

Blakely with a force to intercept the confederates. Sutoto delegated to inform John. Reaching the Cataract. Interesting scenes at the Cataract for Sutoto. The scouts report the tribes to the west. Blakely's force near the confederates. Watching their movements. John's messenger to Blakely. Advice that the tribes are waiting for reinforcements. The tribes on the march east. Blakely's message to John. Blakely intercepting the tribes. His message to the enemy. Their surprise. To give their answer in two suns. The message to the Professor. The Professor decides to capture the Kurabus' village. On the march. Capturing the Kurabus' reinforcements. The villages in his possession. The Professor's message to John and Blakely. A message from Blakely. Hurrying the work at Cataract. Making guns and spears. Taro. The treasure in the cave. Decide to take it to their new home. Loading up the wagons. Transferring the hoard in the caves. A messenger informing John of the battle. Instructs Muro to go to aid of Blakely. |

||

| IV. | The Surrender of the Kurabus | Page 50 |

The load of treasure. A doleful sound. The "cry of the lost soul." Activity at Cataract. Bringing in the flag. The trip to Observation Hill. The warriors participate. George and Harry lower the flag. An impressive scene. The last sad night at the Cataract. A runner from John to the Professor. The confederates within eight miles of Cataract. A movement to capture them. Messenger from the Kurabus' village arrives too soon. The flight of the confederated tribes. The Kurabus determine to defend their village. John orders a forced march to assist the Professor. The messenger from Muro advises the Professor. He learns of the approach of the Professor. The arrival of John. The confederates at the Kurabus' village. Surprise of the latter at the leniency of the Professor. Advancing on the Kurabus' village. A messenger from, the Kurabus. Agree to surrender. The flight of the Tuolos and Illyas. The Kurabus join the allies. Submission. Tastoa's message to the other tribes. |

||

| V. | The New Town Site. The Water Wheel and Sawmill | Page 62 |

Return to the Brabo village. The train from Cataract in sight. The triumphal entrance into the village. The festivities. Safety of the Brabos assured. The Professor tells the chiefs his object in forming the alliance. Suggests the building of a new town. To belong to all the tribes. To take all the chiefs to the new town. The boys want their herd of yaks. Sutoto and party go for them. Blakely's fighting force. The Banyan tree. Its peculiar growth. Sap in trees. Capillary attraction. Hunting a town site. Uraso selects a place. A water-fall. An ideal spot. Reported arrival of the herd. Fencing off a field. How the fence was built. The warriors at work. Building a new water wheel. Erecting a sawmill. The warriors at work bringing in logs. The sawmill at work. |

||

| VI. | Building Up the New Town | Page 74 |

Disquieting rumors of the confederates. Shop and laboratory put up. A safe place for the treasure. Making looms. Searching for minerals. Putting up a furnace and smelter. Making molds for copper coins. The mint. Teaching the people how to use money. First lessons in industry. The measure of value. Coins of no value. Paying wages. Inculcating the ideas of pay for labor. Teaching natives the principles of purchase and sale. Making bargains. Begin the erection of buildings. The Tuolos and Illyas still bitter. Evidences of hostilities. Decide to conquer the Tuolos. John at the head of an expedition. The natives encouraged to bring in all kinds of vegetables. Chica. Burning oil. Why different plants grow differently on the same soil. Ralph and Tom accompany John on the expedition. Going to visit the tribe which captured them. |

||

| VII. | The Expedition Against the Tuolos | Page 86 |

Crossing the West River. Approaching the Tuolos village from the south. The advance scouts. First signs of the Tuolos. The feasting at the village. Ralph and Tom wander from the camp. They discover a cave. Striking a match. The weird interior. Leave the cave to notify John. Return to the cave. A hurried exploration. The home of the Medicine men. Their absence at the village. Meeting the Medicine men at the entrance. Effecting a capture. The Krishnos. A curious cross found by John in the cave. Its history. The uproar in the village. John confronting the Medicine men. They tell him the Great Spirit will destroy him. John strikes a light on the cross with, matches. The Medicine men in terror. Orders one of them to go to the village and tell the Chief to surrender. Surrounding the village. Muro captures a rival set of Medicine men. Another cave. Questioning the newly-arrived captives. They are defiant. |

||

| VIII. | The Submission of the Tuolos | Page 100 |

Threatening the Medicine men. Beating them for lying. Morning. Dissensions in the village. Learn they are surrounded. The Chief comes forward. Meeting John and Muro. John's plain talk to the Chief. Demands his immediate surrender. The Chief stunned. Says he will go and tell his people. The Chief returns. Surrenders. The warriors march into the village. Liberating the captured Brabos. Ralph and Tom visit the large hut where they were confined. Blakely showing the Chief the maneuvers of the warriors. The Chief proposes to torture the Medicine men. John interferes. Asks that they be turned over to him. The Professor and the colony. The insulting message from the Illyas. The messenger to John. Building chairs and tables. Two-and three-room cottages. Stimulating individual efforts. The first thief and the treatment. John and party visit the cave east of the village. |

||

| IX. | Plans for the Benefit of the Natives | Page 111 |

Entering the cave. What they found. The treasure as John had described it. Removing it to the wagon. The Chief, the Krishnos and a number of the warriors taken to the new town. Approaching home. The Chief Marmo. Meets the Professor. The welcoming functions. Interest in the works. Watching the loom. Trying to teach him new ideas. A lesson in justice. Told the difference between right and wrong. Blakely the man of business. The island as a source of wealth. Blakely determines to stay on the island. Agree to build a large vessel. Projecting a trip home. Agricultural pursuits. The states. How lands were to be disposed of. Value of land. Proposing an expedition to the Illyas. Marmo sends a message to the Illyas. Making new guns for the expedition. |

||

| X. | The Peculiar Savage Beliefs and Customs | Page 124 |

The Krishnos. Chief Marmo learning. The Tuolo workman asks permission to bring his family to the new town. The boys find a name for the town. Unity. The Hindoo christening. The expedition against the Illyas. Three hundred warriors. Reflections of the boys. Six tribes. Heading for the Saboro village. Muro happy. A day and night of feasting. Muro's family. The pocket mirrors. Lolo. An artisan. Events at Unity. Two deaths. The peculiar rites. The Spirits in the air. Rewards. Savage beliefs. The honored dead. Lessons from the Great Spirit. |

||

| XI. | Expedition to Subdue the Illyas | Page 137 |

The warriors' families. The plaintain leaf. The native loom. Weaving. Primitive goods. A store set up. Kitchen utensils. Bringing in ore and supplies. Sanitary arrangements. Home comforts. Native combs. Fish fins. An immense turtle. Tortoise shells. John and the war party. Illyas reported in front. Character of country. Savage beliefs. The moon in their worship. Distance to the Illyas village. In sight of the first Illyas. Borderlines. Double line of guards. Illyas surprised. Capturing an Illyas warrior. Sending him back with a peace message. A strong position. The history of the Illyas. Differences in the color of the various tribes. |

||

| XII. | The Perilous Trip of the Wagon | Page 149 |

At Unity. Suros and Oma announce they will not return to their tribes. The return of the Tuolo warrior and family. A cottage for him. Famished. How the Professor explained his act of humanity to Chief Marmo. The principles of justice. Marmo accompanies the Professor through the town. An object lesson. Ralph and Jim in charge of the factory. Sending out hunters to gather in yaks. Laying out fields. Wonderful vegetation. John and the Illyas. Planking movement around the Illyas. The charge. The Illyas in confusion. Their retreat. The forest a barrier. Sighting the main village. Astonishment at its character. An elevated plateau. A town by design. Peculiarly formed hills or mounds. Fortified. The mystery. Sending the wagons to the south. Avoiding the forest. No word from the team. The teams reach the river. Intercepted. Illyas in front. Blocked by precipitous banks. Forming camp. Sending messengers to John. Muro gets the message. Hastens to relieve the force with the wagon. The savage attack. A volley behind the Illyas. |

||

| XIII. | The Remarkable Discovery at Blakely's Mountain Home | Page 163 |

At Unity. The weekly outing. The great forest to the west. The trip of the whites to Blakely's forest home. Driftwood. Centrifugal and centripetal motion. The forest animals. Orang-outan. The monkeys. Reaching the hill. The scaling vine. Reaching the recessed rocks. The two skeletons in the rocks. A gun and trinkets. A sextant. A letter. No identity. The message. Effort to decipher it. A mound for the bones. Forwarding copy of message to John. John's examination of the Illyas' village. The remarkable character of the buildings. Muro returns with the wagons. The Tuolos as fighters. Two captured. Trying to open communications. Returns of the messengers. Defiance. Permitting the messenger to return. |

||

| XIV. | The Surprise and Capture of the Illyas' Stronghold | Page 175 |

Astonishment of the Illyas' messenger. The character of the eastern side of the town. A movement in the night. Surrounding the town. Muro and Uraso as warriors. The architecture of the buildings. Not built by the natives. Different kinds of architecture. Their distinction. Disposing the forces. The signal for attack. John, and his party rush the breastworks. Enter the town. The surprise and confusion of the Illyas. Harry observes the Illyas' chief and attendants. Surrounds and capture them. Muro makes a charge. The chief signals surrender. Uraso surrounds the Illyas. Marched to the great square. The conference between John and the chief. The Doric building. The Illyas' chief. His imperious air. Dignity of Uraso and Muro. |

||

| XV. | The Rescue of Five Captives | Page 187 |

The chief's question. John's brief answer. The chief trying to deceive John. Questions the chief about the messages. The lying answers. The punishment imposed on the warriors. Orders the same punishment for the chief. Consternation. Uraso and Muro plead for the chief. Whipping the most disgraceful punishment for a chief. Demands the white captives. Sama to show the way to their hiding place. The wagon brought out. The boys, accompanied by Lolo, and commanded by Stut. Reach the village. The captives' hut. The rush for the door. The five captives. Three Investigator's boys. A pitiable sight. Hungry. Harry's inscription on the litter. A Saboro and a white man. Taking the Illyas' warriors along. Feeding the rescued ones. |

||

| XVI. | Remarkable Growth of Unity | Page 199 |

Awaiting word from John. Telegraph line needed. Wireless telegraphy. Sound and power. Vibrations. A universal force. B Street in Unity. Visiting the villagers in their homes. Incentives to beautify their houses. Erecting larger dwellings for the chiefs. The schoolhouse. A growing town. Marvels to the chiefs. The mysterious things the white men do. The thermometer. Teaching medicine. Cinchona. Calisaya. Acids. The boys reach the Illyas' village with the liberated prisoners. Making them comfortable. The white man a former companion of John. A health resort. The Investigator's lifeboat No. 3. Mystery about the note. The commotion outside. Capturing the Illyas' reinforcements from the south. Provisions. Cultivation of the soil. George and Harry explore the buildings. Trying to solve the puzzle. Arrangements of the streets. |

||

| XVII. | The Mysterious Cave. Returning to Unity | Page 211 |

Cornerstones. The treasure chart. Caves near the town. A guess at the meaning of the buildings. The Medicine men. Questioning the chief. He says John will be destroyed if he enters the cave. John's test of the truth of the chief's statement. The trip to the cave. Proving that the Medicine men lied. The chief enjoys his first ride. The cave entrance. John goes in. He finds the Krishnos. Their conversation. John appears before them. The consternation. Orders them to leave the cave. Shows the chief that the Medicine men have lied. Taking them to the village. John and the boys explore the cave alone. No treasure. An immense deposit of copper. Probable explanation of the houses of the town. An immense chamber. The start for Unity. Sighting the Saboro village. Muro's family. Waiting to go to Unity. The town out to meet the returning warriors. Angel at the reception. |

||

| XVIII. | Building a Ship to Take Them Home. Peace, | Page 221 |

Oroto surprised at the appearance of Marmo. Anxious to see the great White Chief. The Professor welcomes the Illyas' chief. His great surprise. Friendship. Has no further belief in the wise men. Life and death. Why he was brought to Unity. Peace among the tribes. Oroto and Marmo confer. A jollification of the whites. What had been accomplished in two years. Building a ship for home. Sadness as well as joy. The engineering force of Unity. How the different tribes lived together. Rich soil. New houses. New people. A printing press. A schoolhouse. Making paper. Many mysteries unsolved. One thing lacking. The flag. Getting the flagpole. The ceremony. Hoisting OLD GLORY. |

||

| Glossary of Words Used in the Texts | Page 237 | |

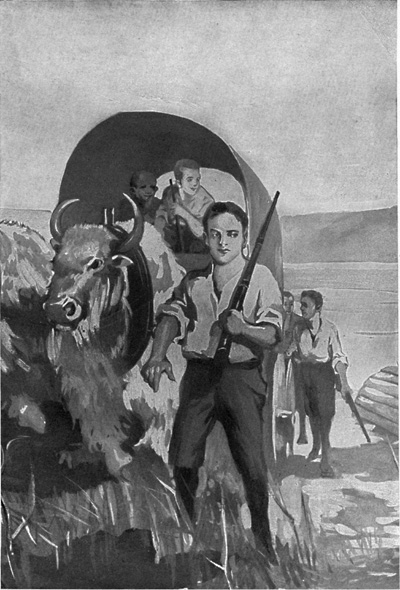

| "The warriors, together with the chief and the two boys, Jim and Will, rushed to meet them" | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| "Meantime John consulted Muro and Uraso, and the three picked out the most trustworthy scouts" | 38 |

| "The act was such a startling one that they threw themselves on the ground in terror" | 86 |

| "The party plunged into the forest, taking the direction which Tom and Ralph had gone on the former trip" | 230 |

| Position of Wagon and Attacking Force | 18 |

| George's Old Dutch Oven | 26 |

| The Tattooed Arm. Antelope | 29 |

| The Taro Plant and Bulb | 45 |

| The Banyan Tree | 65 |

| Showing Capillary Attraction | 68 |

| Sample of Island Fence | 71 |

| The One-cent Coin | 76 |

| The Five-cent Coin | 77 |

| Chica. The Gum Plant | 84 |

| Stone Cross Found in the Cave | 92 |

| Ancient Crosses | 93 |

| Ready for the Happy Hunting Grounds | 131 |

| Primitive Weaving-Frame | 137 |

| Comb from Fin of Fish | 140 |

| The Marmoset | 166 |

| Proboscis Monkey | 167 |

| The Mysterious Message | 170 |

| Orders of Architecture | 179 |

| The Peculiar Illya Village | 212 |

| Diagram of Cross-shaped Cave | 219 |

| Paper-making Machine | 231 |

| The Stars and Stripes | 236 |

When the morning sun was struggling to come up over the mountains in the east, the whole camp was startled by Sutoto, who, with a number of the Berees during the night, had acted as a picket, to observe the attitude of the defeated tribes.

He made his way to the Professor, who had taken his old place in the wagon. "The Tuolos, Kurabus and Illyas have all united and are now on the big river."

"When did you last see them?"

He held up his fingers to indicate the time, and the Professor called to Will: "Do you know what time he means?"

Will soon interpreted the sign to mean three in the morning.

"If they have not been separated it is a sign that they intend to continue the fight," said John.

"I suggest," replied the Professor, "that we call a council of the principal men in the tribes, and let them fully understand what our aim and desires are, and thus unite the four tribes in a bond of unity. This is a most opportune time."

The news of the obvious action of the tribes to the north was soon learned by all, and whenp. 12 the Professor's view was communicated there was a universal assent.

Within an hour the chiefs assembled, and the Professor addressed them as follows: "My brothers, I am glad to be able to talk to you, and Uraso and Muro will tell you what I have to say. The Great Spirit sent us here, and we tried for a long time to tell you why we came, but you did not understand it.

"The Great Spirit is the same to all tribes; he does not favor one more than the other, but sometimes one tribe will understand better than the other what he wants, and when they do know what he says it makes them stronger and better.

"We believe the Great Spirit wants the different tribes to live together in peace, and not kill each other, and for that purpose he has given each one something to do. If he does that in a right way he not only helps himself, but he helps everyone else.

"We want to show you how to do this, but before we can start we must all be like one family. We do not ask the Berees to give up their customs and become Saboros, nor do we want the Brabos to do as the Osagas do. We do not care what you believe about this or that, or how you shall dress, or what language you shall speak. The only thing we should be careful to do alike is to so work that we shall not injure each other.

"It will not be hard to learn this, and we will all be patient, and we ask you to be patient with us. We want to show you that the ground is your mother, and when you ask her for fruit shep. 13 will give you plenty, and you can soon learn to make things which will make your wives and children happy and contented.

"You will know that anything you own will be yours, and none can take it from you, and if anyone tries to take it, everyone will stand up and protect you. The tribes which are now to the north must be made to understand this, and we must unite to compel them to agree to this manner of living.

"I know that the tribes are powerful enemies, and can bring a great many warriors to fight against us, but we do not want to kill, nor do we want them to kill us. Your weapons are not any better than the ones they have, and we want to make some that will enable us to overcome them, not for the purpose of killing them, but only to protect ourselves and our homes and children.

"If that is what you want and you agree with me that it is the right thing to do, we will help you. To do that you must not fight each other. I have heard that you do not believe in sacrificing captives, as the Tuolos and the Illyas and the Kurabus do, and I am glad of it.

"I am told that you all know Suros, the great, father of the Berees, and that he is wise. He is my friend, and he must be present at our councils, but we cannot go to him now, because we must protect our friends, the Brabos, against the warring tribes.

"But we must also be prepared to meet those enemies, and where we live, we have the workshop by which we can make all the wonderful thingsp. 14 needed for our protection. We must go to the Brabos' village, to be on guard, while others must go to our village and bring back those articles, and we will make the things at your own homes, so we can compel those tribes to submit."

These words affected all the warriors, and they gathered around the chiefs and expressed their willingness to do all that the Professor had suggested.

One after the other, the chiefs assented, and the Brabos were especially pleased. Their chief, Oma, arose and said: "We have been fighting our friends, and not our enemies, but we did not know any better. We thought everyone was an enemy. The Great White Chief has told us a new way to live, and we will do whatever he says."

Uraso, chief of the Osagas, held up his hand, and turned to the people: "I was wounded by the White Chief, and he took me to his village and treated me like a friend. He cured me of my wounds, and I became his friend. I left him and tried to come back and tell my people what a wonderful father he was, but the Illyas captured me, and when I escaped, and returned, found my people had gone out to fight him and his people. This made me sorry. I cannot tell you of all the things I saw at his village, and now let the White Chief say what I shall do and my whole tribe will help him. Muro will tell you what he has learned, because he, too, knows him."

"I do not know how to tell you about this wonderful man," said Muro. "I have seen him refuse to kill his enemies, when he could easily do it. Hep. 15 healed the Kurabus, and returned him to his friends, and that is something new for us to think about. His enemies are our enemies, and his friends are our friends."

This remarkable scene, which took place on the battle-field, could not be properly understood without some explanation of the preceding affairs in the history of Wonder Island.

About a year and a half previous to this, the Professor referred to, and two boys, George Mayfield and Harry Crandall, who were companions on the schoolship Investigator, were wrecked and cast ashore on the island. It was fortunate that they landed on a portion of the island remote from the inhabited part, and for several months had no idea that any human beings lived there.

They had absolutely nothing but their clothing; not even a knife or other tool, but despite this, set to work to make all the appliances used in civilized life. The preceding volumes showed how this was done, and what the successive steps were to obtain food and clothing, and to make tools and machinery.

They built a home, and put up a water wheel, a workshop and laboratory; captured a species of cattle, called the yak, and used the milk for food, and trained the oxen to do the work of transportation; they found ramie fiber and flax, built a loom and wove goods from which clothing was made; they found various metals, in the form of ore and extracted them; and finally made guns, electric batteries, and did other things, as fast as they were able to carry on the work.

In the meantime several exploring trips were undertaken, and they learned of the existence of savage tribes, and what was more startling still, ascertained that other boats, belonging to the ill-fated Investigator, had been cast ashore, and later on came in contact with several tribes with whom they had a number of fights, and by chance discovered a tribe, the Tuolos, who held two of the boys in captivity.

These they rescued, namely, Thomas Chambers and Ralph Wharton. Returning from one of these expeditions they found a man at their home, who had entirely lost his memory. This was John L. Varney, a highly educated man, who had seen service in many lands, and later on was restored to reason.

Prior to the present enterprise, which was related in the opening pages, a chief, Uraso, of the Osagas, was wounded and captured by them, and taken to their Cataract home, as they called it, and when healed, he had left them, for the purpose of returning to his own tribe, so that he might bring them to the Cataract as friends; but he was captured and detained.

During this interim, the last expedition was organized, and after some mishaps, they proceeded into the part of the country where the savages lived, and on the way rescued the chief of the Saboros, and also a former companion of John.

Two weeks before our story begins, the Professor was captured by a band of Berees, and taken to their village, where he was instrumental in healing the chief's favorite daughter, and inp. 17 gratitude, placed his warriors at the Professor's disposal to rescue his friends, who were about to be attacked by the hostile tribes.

The Professor saw and rescued two more of the shipwrecked boys, who were held captive by the Berees, and together they started to relieve the occupants of the wagon. The various tribes had been at war with each other, and when they learned that the wagon with the whites was entering their country, all sought to effect the capture; but the enmity between certain tribes caused several of them to unite and the three most bitter and vindictive, namely, the Tuolos, Kurabus and the Illyas, were opposed to the Osagas, the Saboros and the Berees.

It was fortunate that all these forces met at the place where the wagon was located, and in the battle which followed, the whites and their allies won. The situation was, however, that the victory might soon be a fruitless one, because the three tribes could muster a larger force than the four tribes now joined under the Professor, and might renew the attack at any time.

"Let us now see what the situation is," said the Professor, to the chiefs. "I have made a map of the island, showing where the various tribes are located, and where the villages are situated, so we may all have a like understanding."

"I would suggest," said John, "that a part of the force be sent to the Cataract and bring all the machinery and stock we have at that place, to this part of the island, where it can be set up andp. 18 operated. In that way we can the more readily teach the people how to do the work."

"That is absolutely necessary, as it is too far off where the plant is now located, to be of service to us."

"If you will allow me to say something it might help us," remarked Muro. "Let the Professor select a certain number of warriors from each tribe, to go to your village and bring the things here, and others will remain, and watch our enemies."

"That is a good idea," observed Blakely, "but before doing that I think we ought to muster our forces, so that we may know what we have top. 19 depend on, and the chiefs can tell us who are the best fitted for the various tasks."

"Your view is the correct one," answered the Professor, "and Muro, you, Uraso and Ralsea, inform all of them what is required. I shall expect you, Blakely, to take charge of the mustering of the forces."

The suggestion was understood and agreed to by all, and the various tribes were arranged in columns.

The Professor addressed them as follows: "In our country, we have a plan for everything we do, and everything is done in order. We try to follow the plan in which the Great Spirit orders everything done. We want every man to do something and be responsible for one part of the work."

"While the people are gone to the White Chief's village, others might go to the Berees' village and bring the Great Chief Suros, as he is wise, and we should like to have him here," added Uraso.

"Your suggestion," said the Professor, "is a wise one, and it will show how earnest you are in making this bond a lasting one among you. I thank you for calling attention to the matter, and it shall be acted on at once."

|

The muster roll, as prepared by Blakely, showed the following results: The Berees: Sub-chief Ralsea and eighty-five warriors. The Osagas: Chief Uraso, two sub-chiefs and one hundred and ten warriors. The Saboros: Chief Muro, three sub-chiefs and p. 20one hundred and fifteen warriors. The Brabos: Chief Oma, two sub-chiefs and one hundred and five warriors. The whites were enumerated as follows:

The Professor. |

|

| { George Mayfield, | |

| { Harry Crandall, | |

| { Thomas Chambers, | |

| The boys: | { Ralph Wharton, |

| { James Redfield, | |

| { William Rudel. | |

The combined force thus numbered four hundred and twenty-four, not counting Angel. It should be said that Angel was an orang-outan, captured while a baby, and he had been educated by George to do many wonderful things. It is well known that these animals are great imitators, but this one really learned many useful things. One of them was to climb the tallest trees and warn George of the approach of enemies, and this was such a wonderful thing, that Muro explained it to his people and they really admired the animal, and who was, in consequence, a great pet.

When the council met the Professor said: "I will detail one hundred and fifty men to accompany John to our village to bring the things from that place, and those remaining will go to the Brabos' village to watch our enemies and to protect the home of our friends. Ralsea should take the litter and twenty men and go after the Greatp. 21 Chief Suros, and bring him here, so that we may consult with him."

"We have thirty guns," said John, "and at least half should be left with you while we are away."

"It might also be well," remarked Blakely, "to have the different chiefs select the most competent men in the four tribes to whom instructions might be given in the use of the guns, and I will drill them and show how to handle them to the best advantage."

The four chiefs selected the men for the expedition from the respective tribes, and the four boys who had been together for so long, begged that they might be of the party also, and the Professor could not deny them this privilege.

Early in the morning the entire force started on the march for the Brabos' village, and before night arrived at the main one, where the Professor and his party had the first close sight of the village and the inhabitants.

Runners were sent ahead to inform the people of the expected arrivals. This was the first time in the history of the island that a foreign tribe had ever visited them, except in a hostile manner, and the curiosity of the women and children was intense.

Oma, the chief, had graciously ordered the best hut for the Professor, but he declined it with many thanks, and presented the chief's wife with one of the mirrors, which delighted them. Some of the warriors were designated to procure game, and others to bring in wood for the fires, and thep. 22 most skilled were selected to scout to the northwest to determine the movements of the enemy.

In the morning, John and his party, with the wagon, started for the Cataract home. Uraso and Muro were designated to accompany them, and you may be sure that to the boys this trip had in it every enjoyment that could be brought to them.

"What a difference there is in things, now," mused Harry, as he drove the yaks along. "I hope they will have no trouble with those treacherous tribes until we get back."

"It makes me sad to think that we have to give up the Cataract," said George. "The past year has been a happy one to all of us, even though we have had serious times. And what shall we do with the flag?"

They had made a beautiful flag, which floated from a tall staff on Observation Hill. It would have been a grief to permit it to remain.

John overheard the conversation. "Yes; we shall certainly take it with us, and teach the natives here to respect it." And the boys applauded the sentiment.

In two days more the party sighted the Cataract, and saw "Old Glory" floating from the mast. When they saw it again, they took off their hats and gave three cheers. This so astonished the natives that they could not understand it, and Uraso told his people that the flag was worshipped by the white people.

"Did you hear what Uraso told them?" asked John.

"No; what was it!"

"He said that white people did not carry individual charms to ward off troubles, but that they had the flag for that purpose, and the one flag was the charm of all the people; and he also told them it was made a certain way for that purpose."

The flag incident, and Uraso's interpretation of it, amused the boys immensely.

"Do you know why Uraso thought so?" asked John.

"No; I can't understand why he ever had such an idea," replied Tom.

"You forget it has been our custom, ever since I can remember, to go to Observation Hill, each day, to watch the sea, in the hope that a vessel might be sighted. Uraso thought that was intended as a tribute to the flag."

"After all," said Ralph, on reflecting, "they are not so much out of the way, and the flag is really our talisman, isn't it?"

"Yes; because it is a real protection, and not a fancied one. It is a symbol, behind which lies all the power of a material kind, which is able to help us everywhere, and among all people. The charm which the savage wears, is a symbol to him, and that typifies protection from some unknown power. To us that is a reality, and we know where the power is."

The dear old Cataract home. How the boys roamed over every part of it, and went down where the cattle were still ranging around. The place was a study for the warriors.

"Now, boys, for the first day entertain your visip. 25tors, show them everything, and amuse them in every way possible; and after to-morrow we must commence work in earnest," was John's injunction to the boys.

What could be more natural than to start the water wheel in motion? The warriors stood on the bank, watched them push it in place, and then the sawmill was started. The process of turning out lumber with the saw was marvelous. Every part of the shop was filled, as the boys set the grindstone, the lathe, and the gristmill into motion.

When a log was finally secured to be cut into shafts for spears, and they saw the wood-turning lathe make the shaft round and true, their enthusiasm knew no bounds.

"Tell them, Muro, that is what we want them to do," said John, and they opened their eyes at the possibilities.

There was still quite an amount of barley which had not been ground, and the willing warriors helped the boys bring a lot to the mill and the production of the flour before their eyes was such an amazing thing that they could not even give vent to their expressions.

Early in the day one of the bullocks had been killed by John's order, and a roasting pit dug out, and this was now being prepared for the principal meal of the day, and many of them were interested in this new way of roasting an entire carcass.

A quantity of vegetables had also been gathered by the parties detailed for the purpose, and Georgep. 26 was the busiest of the lot, as he personally attended to the cooking of the various dishes. He had most willing helpers, each one trying to lend a hand, so that he did little more than direct.

But he was determined to have bread, and it did not take long to improvise an old Dutch oven with the firebrick, and in this a fire was built, so that the bricks were heated up intensely, and the fire then withdrawn, and a cover put over the chimney. The heated brick, therefore, did the baking. Loaf after loaf was put in, and while the dough had not risen as it should have done, owing to lack of time, still the bread produced was something so unlike anything the natives had ever seen, that the making of it in their presence was a joy, to say nothing of the eating of it when the meal was served.

It was not only a picnic; it was a feast. None there, excepting Uraso and Stut, had ever tasted such things before. They knew what honey was, but sugar was a novelty, and this was suppliedp. 27 without stint. George had no opportunity to make any delicacies in the form of cakes, but he made a barley pudding in which was a bountiful supply of sago.

After the meal, John called the boys together and said: "Before dismantling the place here it has occurred to me that there are some things which we ought to make, because it will take some time to set up the parts, even after we get them in the new locality. I believe we still have quite a quantity of the cast-steel bars, from which we intended making gun barrels."

"In looking over the stock to-day," said Harry, "I find we have sufficient to make at least fifty barrels, and I have prepared the lathe to do just what you have suggested."

"Good boy," responded John. "You and Tom keep at that, and don't mind about anything else. If we can once get the barrels bored out, and the fittings made, we can put them together without having the shop in running order."

"In talking with Harry yesterday," said Tom, "we made up the scheme of putting a small bench in the wagon, with the vise, so that we can put together some of the guns on our way."

"All that is in the right direction. And now, another thing. The wagon we have is not at all adequate for what we have to take with us, but we have plenty of people to carry things, and they will be glad to do it, but some things are very inconvenient to carry, so that it will be of material assistance if we build another wagon."

The boys looked at John, merrily laughing at the suggestion.

"Just the thing," said Ralph, "and it is easily done. We still have the old wheels that were used before we built the last set."

"Quite true; I had entirely forgotten about that. Uraso will help, and will be just the fellow to direct his men. Now let us start at this with vigor. We must return as early as possible. The hostiles may attack the Professor at any time, and the weapons are necessary articles."

As they were about to separate, Harry remarked: "We have a quantity of the iron which we made, and instead of carrying it along in the wagon, it occurred to me that we ought to forge out some spears and bolos."

"I had counted on doing that myself, but many thanks for the suggestion," answered John.

There was one thing noticeable in all the warriors, and that was the universal tattoo. This was something practiced by all. Referring to the custom, Ralph asked: "What is the cause of the tattooing habit?"

John looked at him with a smile, as he answered: "People who wear few clothes want something with which to decorate themselves. The idea always was and always will be, to improve on nature. That is one of the reasons. The other is, that it was an original way of distinguishing one individual from another. You will notice among these people, that the chiefs have a different tattoo from the others in the tribe."

"Do you mean that the name of each manp. 29 was tattooed so he would be known in that way?"

"Yes; and also to designate his rank. The names of great warriors and wise men of the tribe are generally descriptive. The North American Indian adopted that course, and it was a very sensible thing to do. You have heard of Sitting Bull, Rain in the Face (that is, a pock-marked individual), Antelope, and others of like character, could be drawn, and thus convey the name without difficulty. Uraso and Muro mean some particular things or objects which can be depicted, and thus one tribe can communicate with the other, even though they do not understand each other's language."

"Then clothing is also another way of showing rank or title?"

"In countries where people are compelled to wear covering as a matter of comfort, the clothing was adopted as a means of expressing the person's position in life."

After John and his party left the Brabos' village, the Professor called Blakely into consultation, and advised him to organize the remaining warriors into some cohesive form, and provide a definite and orderly plan of carrying out the scouting and picketing tactics necessary to keep them advised of the movements of the hostiles.

Blakely had already acquired a fairly good knowledge of the rudiments of the native tongue, so that he was able to get along well in giving his orders and disposing of the warriors. He was ably seconded by Ralsea and Sutoto; and especially, the latter, became one of the most important factors in the organization of the tribes in making a strong and intelligent fighting force.

Two days after John left, it was announced that the old Chief Suros was on his way from the southern part of the island, and the Professor headed a party of thirty picked men, accompanied by Sutoto, to welcome him. The warriors were taken from the four tribes.

They met the litter, bearing the Chief, fully five miles from the village, and Suros was visibly affected at the honor shown him. The Professor extended every act of courtesy, and when they arrived at the village, the Professor was quick to give him the full details of all the happenings since their last interview.

"We have talked over the plans to make youp. 31 and all of your people happy and strong. I have sent a number of the warriors to my village, and they will bring all our things with them, so that we may put them up in your country, and teach your people how to build and to make useful articles, and beautiful ornaments."

"I have heard the wonderful things which you have done, and what you have promised, and we will try and follow your words," he answered.

"I have told the people that you must be here, as we value your wisdom. We would go to you, but we still have powerful enemies to the north, and they are waiting to attack us. Until we are safe from them we cannot go to you; but when my people return we will be better prepared to resist."

The chief was visibly affected at this consideration for him, and he thanked the Professor for sending the messengers.

The boys, Jim and Will, were interested observers in all that was taking place, and the Professor had them about him at all times, and to them he communicated his orders. Their ready understanding of the native tongue was a great help to the Professor.

It was for this reason that the Professor was glad the two boys were content to remain with him. Speaking about the savages, to the Professor, Jim remarked: "There is always one thing which seems singular about these fellows. They are awfully quick at learning. Now, what I can't understand is, that, quick as they are, theyp. 32 do not seem to advance very much, but stay in the same rut right along."

The Professor smiled at the observation, as he replied: "Sir John Lubbock, a noted English naturalist, sums up his estimate of the savage mind in the following statement: 'Savages unite the character of childhood with the passions and strength of men.' Their utter simplicity is their weakness. When that is aroused, if properly done, they become men."

"But what is the great difficulty in the way of their advance?"

"The greatest writers seem to agree that the primary want of the savage is a rigid, definite and concise law. The idea of order does not appeal to him, except to a limited extent. Like children, they do not go beyond the immediate thing. The reasoning faculties are not impaired, but are undeveloped."

But Jim's observation was true. Blakely early discovered this in treating with the natives, and it did not take long to make them understand that by working together for the common defense they could be made far more effective than by permitting each to do as his own impulse dictated.

Thus, by constant association with the head men in the different tribes, he early learned who were the best runners, and the most skillful scouts, and who were particularly reliable for the different branches of the service.

Sutoto, as stated, was the most valuable factor, and the Professor grew to love him. One day he came in great haste, and said: "I have news forp. 33 you. The tribes are directly north of us, and appear to be moving to the east."

"Do you know how large a force they have?"

"Fully three hundred."

"Have you any theory why they have not attacked us before?"

"I think they are sending for more warriors."

"How many more can they depend on from their tribes?"

"Not more than one hundred and fifty or two hundred."

"Do you think it is possible, Blakely, that they have learned of the force which we have sent to the Cataract?"

"This movement to the east seems to indicate it."

"In order to satisfy yourself it would be wise for you to ascertain their actions at once."

"I have selected a hundred picked men, and shall take the field this afternoon. I have suspicions that they are delaying on account of reinforcements, or waiting for reports from the runners which they have, no doubt, sent to the Cataract."

"I was rather stupid in that matter," exclaimed the Professor. "I had overlooked the fact that the Kurabus were the ones who attacked us at the Cataract, and as they know its locality it is but natural they should make an advance in that quarter."

Blakely and his men were on the way within a half hour after this conversation. This was now the fifth day after the departure of John.

The Professor, and the chiefs, Oma and Suros, were in daily consultation, and together were developing a plan by which the different tribal interests could be welded together, and to establish a form of government which would be agreeable to all.

On the morning of the sixth day, after John's party left the Brabos' village, three of the hunters who were of the party delegated to bring in game, and one of whom had been instructed in the use of the gun, captured two Kurabus within a mile of the Cataract.

These were brought to John at once, and there was high glee at the success of the hunters. Harry was the first to see the captives and he rushed in to John with this information:

"The hunters have captured two Kurabus, and who do you suppose is one of them? He is the fellow we wounded and brought here with us. Don't you remember the one we carried out at the time I put an inscription on his litter?"

John smiled, as he recalled the litter. His association with the different ones made him fairly well acquainted with the language by this time; but Uraso and Muro were present. As they were brought in, John looked at them and his brow darkened, as he addressed them sternly.

"Why are you here?"

They cringed before his piercing look.

"Answer me! Do you want us to kill all of your people? Did you tell your chief when we let you go, that we did not want war, but peace?"

Neither of them answered, but shrank back.p. 35 John assumed a terrible anger, as he continued: "We healed you, and tried to show our friendship, but you tried to kill us. Is that what you people believe in?"

Tama, who was the warrior alluded to by Harry, soon recovered his speech, and after glancing around at the chiefs, said: "The chiefs would not believe what you said."

"What are you here for now?"

"I was sent here to see what you were doing."

"How many were sent?"

"No one but Reto and myself."

"Lock them up," said John, "and keep a good guard over them. So that is their game, is it? So much the more important for us to get the weapons ready."

The new wagon was now ready for the top, and this was completed in short work. John started on the bolos immediately, and also forged out a number of spears. The boys were set to work preparing the stocks for the barrels, and these were cut out in the rough at the sawmill, and several more knives prepared. The most skillful of the warriors were then instructed to dress them up and get them ready for the barrels.

The work was prosecuted not only during the day, but at night, as well. It was fortunate that during the time the yaks were lost, some months before, they had trained a pair to drive, and these were now again yoked up to give them experimental training for the coming journey.

Meantime John consulted Muro and Uraso, and the three picked out the most trustworthy scouts.p. 36 Giving them explicit instructions to proceed westward, and discover, if possible, whether their enemies were making any movement toward the Cataract, and if, on the other hand, the movement was toward the Professor and the Brabos' village, to send one runner to the village and the other back to the Cataract.

In less than ten days' time Harry had turned out thirty-two barrels, and John had given a great deal of attention to the preparation of the ammunition.

Blakely started north with the picked warriors, and before evening came in sight of them, headed for the east. It was evident that they were about to go to the Cataract.

Sutoto begged to be permitted to go there and inform them of the danger of attack, and Blakely consented, and without waiting for the morning, was on his way. He traveled most of the night, reaching the place in the afternoon, and was received by John and the others with the most effusive welcome.

"What are you here for?" asked John hurriedly.

"The tribes are coming this way."

"I have just learned from one of our runners that they went far to the north of you, and assumed that the intention was to attack us."

"The Professor should be warned at once," was Sutoto's response.

"I have instructed that to be done," answered John.

The scenes around the Cataract were intensely interesting to him. He wandered around with the boys, and asked questions on every conceivable subject. Blakely had given him one of the guns, and he was taken to the workshop and toldp. 38 how they were made. These things so fascinated him that, hungry as he was, he could hardly be induced to take time for his meals.

The boys admired him immensely, and together they acted like boys. The water wheel; the sawmill; the two stones which served as the gristmill; the grindstones; the lathes; and the little foundry were entrancing.

When the boys took him to the blacksmith shop, and he saw the forge, and the numerous spear heads which John had turned out, as well as the bolos, his eyes showed the intense delight the sight afforded him.

The next morning one of the runners appeared and stated that the tribes were still waiting, and also imparted the further information that Blakely and his party were at a safe distance, and unknown to the hostiles.

It was obvious now that they were awaiting the arrival of the two scouts who had been captured before advancing. Several scouts and runners were again sent forward, with instructions to return with information the moment an advance was made.

When Blakely reached the vicinity of their confederated enemies, he thought it wise to keep in the background, and was at a loss to account for the delay during the entire day, but before evening one of the Berees, who had been sent by John, arrived in camp.

"I have just come from the white man's village, and they know that the tribes are moving in that direction."

"How did they discover it?"

"We captured two spies and have them as captives."

This information suggested the cause of the delay. He immediately called a runner, and indited the following letter: "I am keeping on the watch, and am not afraid to attack the whole of them, if need be. If the guns you are making are not completed, do not worry about it, as I shall keep them interested here for several days longer. I will not appear unless I find they have taken up the march in your direction. Blakely."

The following day the scouts informed Blakely that the allies had broken camp and were about to move to the east. Calling the warriors together, he addressed them as follows: "My friends; we are about to meet your enemies, not for the purpose of fighting them, but to prevent them from attacking our friends at the white man's home. Our friends there are preparing the fire guns for us, before they come to us, and we must now stand together to prevent them from going there until we are ready to meet them."

The warriors all crowded around, and showed by their attitude that they could be depended upon.

"We have with us eleven fire guns, and I will now tell you how we must fight them, if it is necessary. I will stand in the center of the front line, with the guns, and on each side of us will be the ones I shall select. All those in front will have bows and arrows, but you will not need them, unless they come up too close. We must nowp. 40 march to the right, as fast as we can, and get between them and our friends."

The column started out on its mission, and made its way with the utmost speed to the east, and before noon turned to the north, being thus placed directly in the path of the oncoming forces. The allies moved along deliberately, entirely unaware of the existence of any force.

Before four o'clock the first signs of the advance were observed. Blakely had selected a strong position on a slight elevation, on the east side of one of the little streams which flowed into the Cataract River, that commanded an open front. His entire force was placed between two natural objects, the right resting behind a rocky projection and the left to the rear of a heavy chaparral of wood.

Entirely unsuspecting, the allies marched along the stream, and crossed not a hundred yards below. When they were within hailing distance, John and Ralsea suddenly appeared in front of their concealed column, and the latter, at the instigation of Blakely, addressed them as follows:

"The white men do not want war, but peace. They have come only to rescue their own people. You must give them up, or there can be no peace. The white chief tells me that if you injure or kill the white men you now have he will hold you responsible, because he is powerful, and is now ready to destroy you and your wives and children, but he does not want to do that. We are here to prevent you from going to the white man's house."

The consternation on the faces of the savages, atp. 41 the appearance of two, was easily discernible. They listened in silence while Ralsea spoke, and, then indicated that they would hold a council and give their answer.

It was evident that the allies were taken by surprise, and it must have been obvious that they had no idea of the force which was in their front. Blakely had wisely stationed pickets to the right and the left, in order to observe their movements, after the first surprise was over.

The conference lasted until night fell, and thus the first object was gained; delay. In the morning one of the chiefs appeared, and Blakely and Ralsea again went to the front.

"I will give you our answer," he said. "The white man attacked us, and we fought him back. He has killed our warriors, and we will not treat with him at this time."

Ralsea replied: "You have done the same that we have done toward the white man; we were always the first to attack them. They tried to be friendly, but we would not listen to them."

"We will let you know in two suns what our answer is." And he withdrew.

"That means," remarked Ralsea, "that they are waiting for reinforcements."

"So much the better. We will be reinforced much better than they by the time their reinforcements come to hand."

"We must send a runner to the Great White Chief, and tell him to stop the Kurabus from coming to their assistance," said Ralsea.

"That is a wise suggestion," answered Blakely;p. 42 and without delay one was selected and made his way to the Brabos' village.

When the Professor received Blakely's note he called in the Brabo chief, Oma, and said: "The forces we sent out are preventing the allies from going to our village, and have sent a runner here to inform us that the Kurabus are about to send more warriors to aid our enemies. Select one hundred warriors and let us go to the Kurabus' village and capture the warriors who are there, and also put the villages in our power. This may make them understand that they have no homes to go to unless they come to us."

This information delighted Oma, and he hurriedly gathered the warriors, and the Professor concluded to accompany them, as he did not want the warriors to commit any excesses against the villages and inhabitants of their former enemies, or exact any reprisals for the past indignities that some of them had suffered from the Kurabus.

A day's march brought them close to the main village, and scouts were sent to the front to ascertain whether the warriors still remaining in the village had gone forward. Before the scouts could return fully fifty warriors emerged from the village, and were taking up the march to join the allies.

The Professor instructed the warriors under his command to divide into three parties, one to remain with him, and the others to go to the right and to the left, so that the Kurabus would thus be entrapped.

The party marched forward unsuspectingly, dip. 43rectly toward the position occupied by the Professor, and he instructed Oma to show himself and inform them that they were surrounded and that resistance would be useless.

Some, more venturesome than others, started to retreat, but the unexpected appearance of the Professor's warriors drove them back, and without firing a shot or loosing an arrow they submitted. When the Professor appeared they were the more surprised. The whole were marched back to the village, and, although the women tried to escape, all were soon rounded up and brought back.

The captured Kurabus warriors were taken to the Brabos' village, and the women informed that they would not be injured, as the white man did not believe in making war.

The Professor at once sent a runner to Blakely and also to John. Two days afterwards the runner appeared at the Cataract with the following message from the Professor:

"We captured the Kurabus' village to-day, and all the warriors left there, as they were about to leave to join the forces now before Blakely. We have taken all of them to the Brabos' village, where they will be held. Make the utmost speed with the weapons. In the meantime, I have sent a force to the north to intercept any reinforcements that the Tuolos may forward."

The message from Blakely was as follows: "We arrested the movement of the allies yesterday, and asked why they were determined to attack us. They refused to give an answer, and they are, probably, awaiting reinforcements. My forces are bep. 44tween them and the Cataract, and they will give their answer in two days."

All this news was imparted to the people, and the knowledge was received with enthusiasm. It gave the warriors the first glimpse of the value of cooperation, and the benefits of a directing hand in their affairs.

At the Cataract matters were progressing favorably. Reports from Blakely and the Professor assured them that they would have no difficulty, in a few days, in getting at least thirty of the guns ready. Stut proved himself to be the most apt pupil, and nothing interested him as much as the forge and anvil, and John, noticing this, set him to work on the small anvil to forge out arrow heads.

The arrows used by the natives were uniformly of stone, but the metal ones were perfect, and so arranged that, with the ramie fiber, could be readily attached to the shaft. The most deft workers in the making of the native arrows were selected, and together they made up a large quantity of arrows, and Stut seemed to be indefatigable in turning out the heads for the workers.

During this period the larder was not forgotten. The hunters brought in every day an immense quantity of taro, which seemed to be their favorite vegetable.

This is a stemless plant, which has heart-shaped leaves, about a foot long, and the leaves and stalks are prepared by them in the same way that we use spinach and asparagus.

But the tuber, or root, of this vegetable is thep. 45 most valuable part. It is larger than the common beet, and sometimes grows to a foot or more in length. This was beaten into a pulp by the natives, and made into a bread or pudding.

"I like the taro," said George. "It can be used in so many ways, and I want to try it in the different forms as soon as we have an opportunity."

"In the Sandwich Islands, and in many other places it is the vegetable from which the well-known Poi is made," said John.

"Do you know how it is made?" asked George.

"It is beaten up, just as you see them do it here, and then set in the sun to ferment for about three or four days. It is afterwards boiled with fowl, and makes a very pleasant dish, most appetizing and nourishing. The fermented Poi will last for weeks. It is the same as the well-known kalo of the Pacific Island, the yu-tao of China, the sato imo of Japan, and the oto of Central America. A fine dish is made of it by boiling and then covering the leaves with a dressing of cocoanut oil."

Harry and the other boys had been in consultation for several days concerning the cave, and a day or two before they were ready to start had a talk with John about the treasure there. John listened attentively, and when they had finished, said:

"You are quite right in wanting to take care of the valuables there. You are entitled to them."

"But they are yours, as much as ours, and we shall not touch them unless it is with the understanding that you shall share with us," responded George.

"I could not consider it for a moment."

"You cannot help yourself," said the boys in chorus. "We have arranged all that matter, and you have nothing to say about it."

"But," protested John. "I do not deserve it."

"Well, do we?" asked Harry.

"But you and the Professor discovered it."

"Before you or Ralph and Tom came we arranged the division, so that the Professor has onep. 47-third of it, but we own two-thirds, and that we propose to divide equally among all of us," added Harry.

"Really," said Ralph, "Tom and I are in the same position as John, and we feel it is not right to take a share, but the boys insist on it."

"Well, if you consider that a settlement, I must say that I am going to make good more than my share and the shares of Ralph and Tom."

"We don't want you to make it good," insisted George.

"But you can't help yourself in that. The cave in the Tuolos' country has something in it that will make you wonder as much as the treasure you have here, and it will be fully as interesting to get at and recover as anything you have experienced here."

"When do you think we ought to start for the west?" asked Harry.

"Day after to-morrow will see everything ready. We shall then have all the ammunition sufficient to last us until we can reestablish the plant, and as the new wagon is ready, it should not take us more than a day, with all the help we have, to load and apportion the different loads among the warriors."

"Then why can't we take to-morrow for the expedition to the cave?"

"That will suit admirably," he replied.

On the following morning the boys had the yaks yoked up, and taking with them a number of the copper vessels, and a quantity of the ramie cloth, drove over to the side of the hill opposite the Catap. 48ract house, so as to reach the land entrance of the caverns.

"It is not desirable to have any here know of our visit nor our purpose. It would not make any material difference, as the treasure there is of no value to them; but our motives will be misunderstood," remarked John.

Under the circumstances John and the four boys were the only ones in the party.

"We are going to have some pretty tough work this morning. That gold weighs something."

"Wasn't it a good thing you suggested the making the wagon?"

John smiled without saying anything.

The boys eyed him sharply, and finally Harry said: "That is what you suggested the new wagon for, was it not?"

John nodded an assent.

"Did the Professor say anything to you about bringing it along?"

"He did say it might be taken if you thought so."

"Didn't he suggest that we should do so?"

"No; he said the matter was left entirely to your judgment, and that I should not say anything about it, unless you proposed that course."

"Well, I am thinking we shall have a pretty good load for one team with what we get out of the place," said George.

"It will make a good load, but we can add to it the lightest parts of the stock we have at the Cataract."

Before reaching the mouth of the cavern, ap. 49 messenger hurried over from the Cataract with the information that two runners had arrived from the Professor and from Blakely, and they drove back as quickly as possible, and reached there to learn that another had just arrived from Blakely.

The two runners first to arrive conveyed the information stated in the previous chapter, but the last carried the additional news that there had been a fight between Blakely and the tribes, and that he was slowly moving back to the Cataract, but there was no occasion for alarm.

The latter part of the note read as follows: "Do not be alarmed and continue your work, and if the matter should be at all serious I will advise you by runner in ample time, and shall in any event send another in the next four hours."

John called in Muro and said:

"The forces with Blakely are having a fight with the tribes. I want you to take fifty men, and also twenty-five guns, and assist Blakely and his warriors, and keep me informed of the progress of events. Tell him that by day after to-morrow we shall be on our way. In the meantime you should draw them this way, as we do not want them to go back. For that purpose keep up the show of retreating, and hold them until day after to-morrow."

Within an hour the column was ready and moved toward the scene with celerity, equipped with the new guns, and an ample supply of ammunition, together with the new arrows which had been made.

It was late that afternoon before John and the boys again drove over to the hill, and lost no time in entering the cave. The first care was to bring to the steps at the entrance all the vessels in the first recess.

Some of them were so heavy that it was necessary for four to carry each load. They then proceeded to the inner recess, and here a search was made for every trace of the treasures there, the time required thus making it almost dark before they were able to carry out all the different lots.

These were all stored in the bottom of the wagon. It was dark as they started for the Cataract. As they were leaving they heard the night cry of a bird which had often been noticed before, and Ralph shuddered, as he said:

"It makes me tremble whenever I hear that doleful sound. It was above our head all of the night before the Tuolos captured us, and since that time it always sounded like an omen to me."

John turned to him, as he replied: "That is the voice of the bird called by the Spanish, Alma Perdida."

"Well it isn't a pleasant sound, to say the least," added George.

"It is very significant at this time, however," remarked John.

The boys all turned to him, as he continued: "It is the 'Cry of the Lost Soul'; that is what the name signifies."

And the boys thought of the terrible tragedy in the cave they had just left. The silence on the way home was significant.

The next morning marked the greatest activity in and about the buildings. The wagons were first loaded with the things contained in the shop, the laboratory and the home. Numerous packages were made up in form for the warriors to handle conveniently. Nothing was permitted to remain, as it was felt that the things they had made were too valuable to leave behind. It was past noon before the last articles were secured in bundles.

"You should explain to them, Uraso," said John, "that we shall have to give them pretty heavy loads for the first part of the journey, as the different things can be distributed to the others when we reach them."

"It will not be necessary to do this," he answered; "they are only too glad to carry the heaviest loads." And he refused to apologize to the warriors. This is referred to for the purpose of showing the spirit in which all of them worked to bring the things to their own country.

After the loads were all provided for, and the different ones instructed as to the parts which should be taken by each, John said:

"There is one thing which must now take our attention, and that is the bringing in of the flag."

The boys had forgotten this. "You may tell the warriors," said John, addressing Uraso, "that wep. 52 intend to go to the hill and bring in the flag, which must be taken with us."

As Uraso interpreted this to the people it had a remarkable significance to them. Uraso begged permission to take all of them on the expedition, and this was readily assented to.

The warriors all armed, as though going forth to battle, ascended the hill, with the boys in the lead. Arriving there John formed the column in a circle around the staff. Angel was present, and he shambled toward the pole and mounted it. He remembered the little wheel at the top, which had afforded them such an amusing incident when it was erected.

This time he came down without much solicitation on the part of George.

"As George and Harry were the ones to hoist the flag, I shall delegate them to lower it," said John.

The boys went forward, and at the quiet suggestion of John took off their hats. At this signal John took off his, and Uraso followed suit, and the hint was sufficient for the warriors, who stood with uncovered heads while the boys reverently lowered it.

The wonder and amazement depicted on the faces of those who witnessed it was a spectacle. What an impressive thing it was to them; it was the mystery, which to the savage mind is always an important factor, and John knew it.

The flag was folded with the greatest care, the natives watching each move with intense interest,p. 53 and was then wrapped in cloth, as though it was the most valuable treasure in the world.

"We want them to feel that it is something they must love and protect. It is safe to say, that after this exhibition, everyone of the warriors would have fought to the death to preserve that emblem of power, like the Israelites of old, who regarded the Ark of the Covenant as their fortress and strength."

The last night at the Cataract was a sad one for the boys. For a year and a half it had been their home. They had built every part of it. Each portion had some delicious memory connected with it, and all must now be left to the ravishes of time. Only the water wheel would be left.

It hardly seems possible that the accumulations at the Cataract would make over one hundred packages, aside from the contents of the wagon. When the entire stock of material was arranged the next morning, it was an interesting sight.

The two wagons were driven out from the yard, Harry and Tom in charge of one, and George and Ralph of the other team. Twenty-five light loads had been made for the advance warriors, so that in case of scouting work, one could take the loads of two, and thus leave at least a dozen free for that duty when required.

A quantity of lumber had been cut over six months before, and this was well dried, and would be very valuable to them in beginning operations, and the loads on the wagons were so great that but little of it could be taken in that way. Urasop. 54 saw the utility of the material and insisted that it should all be taken.

Besides the packages thus arranged the most expert of the warriors carried the thirty-two guns, and they had been instructed in their use. Each also carried a bow and set of arrows, and some of them were provided with spears.

During the preceding day no message had come from Blakely, but he knew that the party would leave the Cataract on this day, and they felt no apprehension on his account.

One of the runners from John reached the Professor on the day the train left the Cataract. While the latter tried to prevent the knowledge of his occupation of the Kurabus village from reaching the ears of the warriors, the scouts sent out by the Professor intercepted and tried to capture the messengers which were sent to inform the allies, but failed in their efforts.

When John and his party left, Blakely had drawn the allies to a point within eight miles of the Cataract, and with the reinforcements, headed by Muro, he made a stand. During the night, after a consultation with Muro, the latter, with fifty of his warriors, made a wide detour to the north, and swung around to the west, thus taking a position behind the allies, and this was effected without their knowledge, as they believed.

The object of this movement was to protect the Professor, as the force from the Cataract, joined to that of Blakely's, would be ample to drive them forward, and it was desirable to effect a capturep. 55 of the allies, and thus at one operation place them in their power.

Unfortunately, the messengers from the Kurabus' village reached the allies before Muro started on his trip. The effect on the allies was startling, and the Kurabus were determined to protect their homes. The latter believed that the object was to destroy the village and carry off the women and children, and it was but natural that they should go to their assistance.

As a result the allies during the night quietly stole to the south, which was in the direction of the Illyas' territory, intending to march thence west, and thus attack the Professor from the south.

Their departure was not discovered until morning had been well advanced, and Muro's runner did not reach Blakely until the train from the Cataract came in sight.

This was most discouraging news, as it meant danger to those left with the Professor.

"There is but one alternative now," said John. "We must make a forced march to the relief of the Professor. Uraso has the matter of controlling the force well in hand, and Blakely, you and I will take all the men excepting the one hundred in charge of the material, and go forward rapidly."

The first news the Professor had of the new situation was gleaned from the messenger which Muro had dispatched the moment the escape of the allies was discovered.

"Has the Professor been notified?" asked Blakely.

"I sent two messengers early this morning," was Muro's response.

"That was a wise thing," remarked John. "You are to be commended for the step. We must make a forced march at once, and you must lead the advance with your best men."

Muro was much gratified at this position of trust, and called up the warriors selected and spoke a few words to them. Without waiting to make any other preparations than to provide a day's provisions, his party sallied forth, and headed straight for the southwest.

The following day, the scouts sent out by the Professor to the southeast, discovered the allies rapidly moving toward the direction of the Kurabus' village, but he knew that he had not a sufficient force to meet them, and he also deemed it wise to permit them to reach their village, so that they might be able to learn for themselves that, while he had their homes in his power, he had not despoiled them.

This was surprising news to the allies. Such a course meant, either that the Professor and the tribes with him, were afraid of them, or, that Blakely's message to them was in reality true.