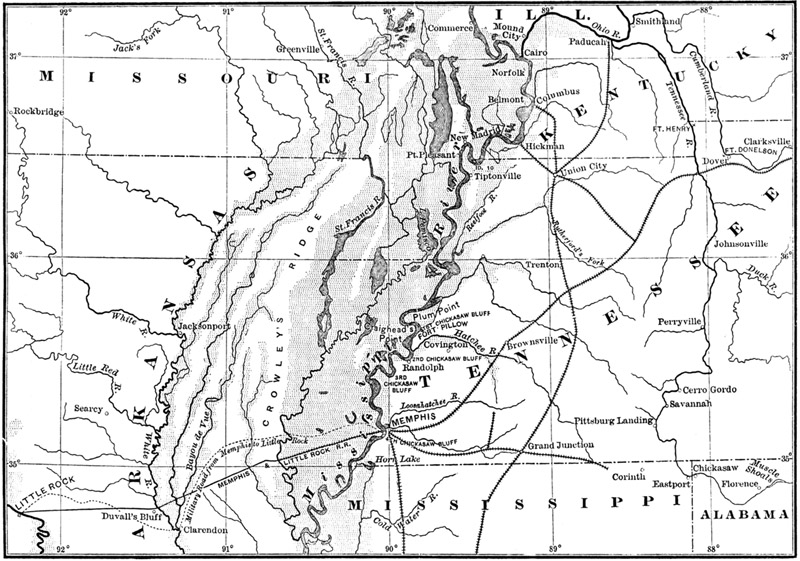

MISSISSIPPI VALLEY—CAIRO TO MEMPHIS.ToList

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Gulf and Inland Waters, by A. T. Mahan

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Gulf and Inland Waters

The Navy in the Civil War. Volume 3.

Author: A. T. Mahan

Release Date: May 22, 2007 [EBook #21562]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GULF AND INLAND WATERS ***

Produced by Jeannie Howse, Steven Gibbs and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

This document is volume three of the series "The Navy in the Civil War". For more information on the series see the advertisement following the index.

Inconsistent hyphenation in the original document has been preserved.

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected in this text.

For a complete list, please see the end of this document.

Click on the images to see a larger version.

The narrative in these pages follows chiefly the official reports, and it is believed will not be found to conflict seriously with them. Official reports, however, are liable to errors of statement and especially to the omission of facts, well known to the writer but not always to the reader, the want of which is seriously felt when the attempt is made not only to tell the gross results but to detail the steps that led to them. Such omissions, which are specially frequent in the earlier reports of the Civil War, the author has tried to supply by questions put, principally by letter, to surviving witnesses. A few have neglected to answer, and on those points he has been obliged, with some embarrassment, to depend on his own judgment upon the circumstances of the case; but by far the greater part of the officers addressed, both Union and Confederate, have replied very freely. The number of his correspondents has been too numerous to admit of his thanking them by name, but he begs here to renew to them all the acknowledgments which have already been made to each in person.

A.T.M.

June, 1883.

| PAGE | |

| List of Maps, | ix |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Preliminary, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| From Cairo to Vicksburg, | 9 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| From the Gulf to Vicksburg, | 52 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Recoil from Vicksburg, | 98 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Mississippi Opened, | 110 |

| CHAPTER VI.[viii] | |

| Minor Occurrences in 1863, | 175 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Texas and the Red River, | 185 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Mobile, | 218 |

| APPENDIX, | 251 |

| INDEX, | 255 |

| PAGE | |

| Mississippi Valley—Cairo to Memphis, | to face 9 |

| Mississippi Valley—Vicksburg to the Gulf, | to face 52 |

| Battle of New Orleans, | 74 |

| Battle at Vicksburg, | 92 |

| Mississippi Valley—Helena to Vicksburg, | to face 115 |

| Battle at Grand Gulf, | 159 |

| Red River Dam, | 208 |

| Battle of Mobile Bay, | to face 229 |

The naval operations described in the following pages extended, on the seaboard, over the Gulf of Mexico from Key West to the mouth of the Rio Grande; and inland over the course of the Mississippi, and its affluents, from Cairo, at the southern extremity of the State of Illinois, to the mouths of the river.

Key West is one of the low coral islands, or keys, which stretch out, in a southwesterly direction, into the Gulf from the southern extremity of the Florida peninsula. It has a good harbor, and was used during, as since, the war as a naval station. From Key West to the mouth of the Rio Grande, the river forming the boundary between Mexico and the State of Texas, the distance in a straight line is about eight hundred and forty miles. The line joining the two points departs but little from an east and west direction, the mouth of the river, in 25° 26' N., being eighty-three miles north of the island; but the shore line is over sixteen hundred miles, measuring from the southern extremity of Florida. Beginning at that point, the west side of the peninsula runs north-northwest till it reaches the 30th degree of latitude; turning then, the coast follows that parallel [2]approximately till it reaches the delta of the Mississippi. That delta, situated about midway between the east and west ends of the line, projects southward into the Gulf of Mexico as far as parallel 29° N., terminating in a long, narrow arm, through which the river enters the Gulf by three principal branches, or passes. From the delta the shore sweeps gently round, inclining first a little to the north of west, until near the boundary between the States of Louisiana and Texas; then it curves to the southwest until a point is reached about one hundred miles north of the mouth of the Rio Grande, whence it turns abruptly south. Five States, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, in the order named, touch the waters bounded by this long, irregular line; but the shore of two of them, Alabama and Mississippi, taken together, extends over little more than one hundred miles. All five joined at an early date in the secession movement.

The character of the coast, from one end to the other, varies but slightly in appearance. It is everywhere low, and either sandy or marshy. An occasional bluff of moderate height is to be seen. A large proportion of the line is skirted by low sandy islands, sometimes joined by narrow necks to the mainland, forming inland sounds of considerable extent, access to which is generally impracticable for vessels of much draft of water. They, however, as well as numerous bays and the mouths of many small rivers, can be entered by light vessels acquainted with the ground; and during the war small steamers and schooners frequently escaped through them, carrying cargoes of cotton, then of great value. There is but little rise and fall of the tide in the Gulf, from one to two feet, but the height of the water is much affected by the direction of the wind.

The principal ports on or near the Gulf are New Orleans [3]in Louisiana, Mobile in Alabama, and Galveston in Texas. Tallahassee and Apalachicola, in Florida, also carried on a brisk trade in cotton at the time of the secession. By far the best harbor is Pensacola Bay, in Florida, near the Alabama line. The town was not at that time a place of much commerce, on account of defective communication with the interior; but the depth of water, twenty-two feet, that could be carried over the bar, and the secure spacious anchorage within made it of great value as a naval station. It had been so used prior to the war, and, although falling at first into the hands of the Confederates, was shortly regained by the Union forces, to whom, from its nearness to Mobile and the passes of the Mississippi, as well as from its intrinsic advantages, it was of great importance throughout the contest.

The aim of the National Government in connection with this large expanse of water and its communications was two-fold. First, it was intended to enter the Mississippi River from the sea, and working up its stream in connection with the land forces, to take possession of the well-known positions that gave command of the navigation. Simultaneously with this movement from below, a similar movement downward, with the like object, was to be undertaken in the upper waters. If successful, as they proved to be, the result of these attacks would be to sever the States in rebellion on the east side of the river from those on the west, which, though not the most populous, contributed largely in men, and yet more abundantly in food, to the support of the Confederacy.

The second object of the Government was to enforce a strict blockade over the entire coast, from the Rio Grande to Florida. There were not in the Confederate harbors powerful fleets, or even single vessels of war, which it was necessary to lock up in their own waters. One or two quasi men-of-war escaped from them, to run short and, in the main, [4]harmless careers; but the cruise that inflicted the greatest damage on the commerce of the Union was made by a vessel that never entered a Southern port. The blockade was not defensive, but offensive; its purpose was to close every inlet by which the products of the South could find their way to the markets of the world, and to shut out the material, not only of war, but essential to the peaceful life of a people, which the Southern States were ill-qualified by their previous pursuits to produce. Such a blockade could be made technically effectual by ships cruising or anchored outside; but there was a great gain in actual efficiency when the vessels could be placed within the harbors. The latter plan was therefore followed wherever possible and safe; and the larger fortified places were reduced and occupied as rapidly as possible consistent with the attainment of the prime object—the control of the Mississippi Valley.

Before the war the Atlantic and Gulf waters of the United States, with those of the West Indies, Mexico, and Central America, were the cruising ground of one division of vessels, known as the Home Squadron. At the beginning of hostilities this squadron was under the command of Flag-Officer G.J. Pendergrast, who rendered essential and active service during the exciting and confused events which immediately followed the bombardment of Fort Sumter. The command was too extensive to be administered by any one man, when it became from end to end the scene of active war, so it was soon divided into three parts. The West India Squadron, having in its charge United States interests in Mexico and Central America as well as in the islands, remained under the care of Flag-Officer Pendergrast. Flag-Officer Stringham assumed command of the Atlantic Squadron, extending as far south as Cape Florida; and the Gulf, from Cape Florida to the Rio Grande, was assigned to Flag-Officer [5]William Mervine, who reached his station on the 8th of June, 1861. On the 4th of July the squadron consisted of twenty-one vessels, carrying two hundred and eighty-two guns, and manned by three thousand five hundred men.

Flag-Officer Mervine was relieved in the latter part of September. The blockade was maintained as well as the number and character of the vessels permitted, but no fighting of any consequence took place. A dashing cutting-out expedition from the flag-ship Colorado, under Lieutenant J.H. Russell, assisted by Lieutenants Sproston and Blake, with subordinate officers and seamen, amounting in all to four boats and one hundred men, seized and destroyed an armed schooner lying alongside the wharf of the Pensacola Navy Yard, under the protection of a battery. The service was gallantly carried out; the schooner's crew, after a desperate resistance, were driven on shore, whence, with the guard, they resumed their fire on the assailants. The affair cost the flag-ship three men killed and nine wounded.

Under Mervine's successor, Flag-Officer W.W. McKean, more of interest occurred. The first collision was unfortunate, and, to some extent, humiliating to the service. A squadron consisting of the steam-sloop Richmond, sailing-sloops Vincennes and Preble, and the small side-wheel steamer Water Witch had entered the Mississippi early in the month of October, and were at anchor at the head of the passes. At 3.30 A.M., October 12th, a Confederate ram made its appearance close aboard the Richmond, which, at the time, had a coal schooner alongside. The ram charged the Richmond, forcing a small hole in her side about two feet below the water-line, and tearing the schooner adrift. She dropped astern, lay quietly for a few moments off the port-quarter of the Richmond, and then steamed slowly up the river, receiving broadsides from the Richmond and Preble, [6]and throwing up a rocket. In a few moments three dim lights were seen up the river near the eastern shore. They were shortly made out to be fire-rafts. The squadron slipped their chains, the three larger vessels, by direction of the senior officer, retreating down the Southwest Pass to the sea; but in the attempt to cross, the Richmond and Vincennes grounded on the bar. The fire-rafts drifted harmlessly on to the western bank of the river, and then burned out. When day broke, the enemy's fleet, finding the head of the passes abandoned, followed down the river, and with rifled guns kept up a steady but not very accurate long-range fire upon the stranded ships, not venturing within reach of the Richmond's heavy broadside. About 10 A.M., apparently satisfied with the day's work, they returned up river, and the ships shortly after got afloat and crossed the bar.

The ram which caused this commotion and hasty retreat was a small vessel of three hundred and eighty-four tons, originally a Boston tug-boat called the Enoch Train, which had been sent to New Orleans to help in improving the channel of the Mississippi. When the war broke out she was taken by private parties and turned into a ram on speculation. An arched roof of 5-inch timber was thrown over her deck, and this covered with a layer of old-fashioned railroad iron, from three-fourths to one inch thick, laid lengthways. At the time of this attack she had a cast-iron prow under water, and carried a IX-inch gun, pointing straight ahead through a slot in the roof forward; but as this for some reason could not be used, it was lashed in its place. Her dimensions were: length 128 feet, beam 26 feet, depth 12½ feet. She had twin screws, and at this time one engine was running at high pressure and the other at low, both being in bad order, so that she could only steam six knots; but carrying the current with her she struck the [7]Richmond with a speed of from nine to ten. Although afterward bought by the Confederate Government, she at this time still belonged to private parties; but as her captain, pilot, and most of the other officers refused to go in her, Lieutenant A.F. Warley, of the Confederate Navy, was ordered to the command by Commodore Hollins. In the collision her prow was wrenched off, her smoke-stack carried away and the condenser of the low-pressure engine gave out, which accounts for her "remaining under the Richmond's quarter," "dropping astern," and "lying quietly abeam of the Preble, apparently hesitating whether to come at her or not." As soon as possible she limped off under her remaining engine.

Although it was known to the officers of the Union fleet that the enemy had a ram up the river, it does not appear that any preparation for defence had been made, or plan of action adopted. Even the commonplace precaution of sending out a picket-boat had not been taken. The attack, therefore, was a surprise, not only in the ordinary sense of the word, but, so far as appears, in finding the officer in command without any formed ideas as to what he would do if she came down. "The whole affair came upon me so suddenly that no time was left for reflection, but called for immediate action." These are his own words. The natural outcome of not having his resources in hand was a hasty retreat before an enemy whose force he now exaggerated and with whom he was not prepared to deal; a move which brought intense mortification to himself and in a measure to the service.

It is a relief to say that the Water Witch, a small vessel of under four hundred tons, with three light guns, commanded by Lieutenant Francis Winslow, held her ground, steaming up beyond the fire-rafts until daylight showed her the larger vessels in retreat.

During the night of November 7th the U.S. frigate [8]Santee, blockading off Galveston, sent into the harbor two boats, under the command of Lieutenant James E. Jouett, with the object of destroying the man-of-war steamer General Rusk. The armed schooner Royal Yacht guarding the channel was passed unseen, but the boats shortly after took the ground and were discovered. Thinking it imprudent to attack the steamer without the advantage of a surprise, Lieutenant Jouett turned upon the schooner, which was carried after a sharp conflict. The loss of the assailants was two killed and seven wounded. The schooner was burnt.

On November 22d and 23d Flag-Officer McKean, with the Niagara and Richmond, made an attack upon Fort McRea on the western side of the entrance to Pensacola Bay; Fort Pickens, on the east side, which remained in the power of the United States, directing its guns upon the fort and the Navy Yard, the latter being out of reach of the ships. The fire of McRea was silenced the first day; but on the second a northwest wind had so lowered the water that the ships could not get near enough to reach the fort. The affair was entirely indecisive, being necessarily conducted at very long range.

From this time on, until the arrival of Flag-Officer David G. Farragut, a guerilla warfare was maintained along the coast, having always the object of making the blockade more effective and the conditions of the war more onerous to the Southern people. Though each little expedition contributed to this end, singly they offer nothing that it is necessary to chronicle here. When Farragut came the squadron was divided. St. Andrew's Bay, sixty miles east of Pensacola, was left in the East Gulf Squadron; all west of that point was Farragut's command, under the name of the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron. Stirring and important events were now at hand, before relating which the course of the war on the Upper Mississippi demands attention.

At the 37th parallel of north latitude the Ohio, which drains the northeast portion of the Valley of the Mississippi, enters that river. At the point of junction three powerful States meet. Illinois, here bounded on either side by the great river and its tributary, lies on the north; on the east it is separated by the Ohio from Kentucky, on the west by the Mississippi from Missouri. Of the three Illinois was devoted to the cause of the Union, but the allegiance of the two others, both slave-holding, was very doubtful at the time of the outbreak of hostilities.

The general course of the Mississippi here being south, while that of the Ohio is southwest, the southern part of Illinois projects like a wedge between the two other States. At the extreme point of the wedge, where the rivers meet, is a low point of land, subject, in its unprotected state, to frequent overflows by the rising of the waters. On this point, protected by dikes or levees, is built the town of Cairo, which from its position became, during the war, the naval arsenal and dépôt of the Union flotilla operating in the Mississippi Valley.

From Cairo to the mouths of the Mississippi is a distance of ten hundred and ninety-seven miles by the stream. So devious, however, is the course of the latter that the two points are only four hundred and eighty miles apart in a due [10]north and south line; for the river, after having inclined to the westward till it has increased its longitude by some two degrees and a half, again bends to the east, reaching the Gulf on the meridian of Cairo. Throughout this long distance the character of the river-bed is practically unchanged. The stream flows through an alluvial region, beginning a few miles above Cairo, which is naturally subject to overflow during floods; but the surrounding country is protected against such calamities by raised embankments, or dikes, known throughout that region as levees.

The river and its tributaries are subject to very great variations of height, which are often sudden and unexpected, but when observed through a series of years present a certain regularity. They depend upon the rains and the melting of the snows in their basins. The greatest average height is attained in the late winter and early spring months; another rise takes place in the early summer; the months of August, September, and October give the lowest water, the rise following them being due to the autumnal rains. It will be seen at times that these rises and falls, especially when sudden, had their bearing upon the operations of both army and navy.

At a few points of the banks high land is encountered. On the right, or western, bank there is but one such, at Helena, in the State of Arkansas, between three and four hundred miles below Cairo. On the left bank such points are more numerous. The first is at Columbus, twenty-one miles down the stream; then follow the bluffs at Hickman, in Kentucky; a low ridge (which also extends to the right bank) below New Madrid, rising from one to fifteen feet above overflow; the four Chickasaw bluffs in Tennessee, on the southernmost of which is the city of Memphis; and finally a rapid succession of similar bluffs extending for two hundred and fifty miles, [11]at short intervals, from Vicksburg, in Mississippi, about six hundred miles below Cairo, to Baton Rouge, in Louisiana. Of these last Vicksburg, Grand Gulf, and Port Hudson became the scenes of important events of the war.

It is easy to see that each of these rare and isolated points afforded a position by the fortification of which the passage of an enemy could be disputed, and the control of the stream maintained, as long as it remained in the hands of the defenders. They were all, except Columbus and Hickman, in territory which, by the act of secession, had become hostile to the Government of the United States; and they all, not excepting even the two last-named, were seized and fortified by the Confederates. It was against this chain of defences that the Union forces were sent forth from either end of the line; and fighting their way, step by step, and post by post, those from the north and those from the south met at length around the defences of Vicksburg. From the time of that meeting the narratives blend until the fall of the fortress; but, prior to that time, it is necessary to tell the story of each separately. The northern expeditions were the first in the field, and to them this chapter is devoted.

The importance of controlling the Mississippi was felt from the first by the United States Government. This importance was not only strategic; it was impossible that the already powerful and fast-growing Northwestern States should see without grave dissatisfaction the outlet of their great highway pass into the hands of a foreign power. Even before the war the necessity to those States of controlling the river was an argument against the possibility of disunion, at least on a line crossing it. From the military point of view, however, not only did the Mississippi divide the Confederacy, but the numerous streams directly or indirectly tributary to it, piercing the country in every direction, [12]afforded a ready means of transport for troops and their supplies in a country of great extent, but otherwise ill-provided with means of carriage. From this consideration it was but a step to see the necessity of an inland navy for operating on and keeping open those waters.

The necessity being recognized, the construction of the required fleet was at the first entrusted to the War Department, the naval officers assigned for that duty reporting to the military officer commanding in the West. The fleet, or flotilla, while under this arrangement, really constituted a division of the army, and its commanding officer was liable to interference, not only at the hands of the commander-in-chief, but of subordinate officers of higher rank than himself.

On May 16, 1861, Commander John Rodgers was directed to report to the War Department for this service. Under his direction there were purchased in Cincinnati three river-steamers, the Tyler, Lexington, and Conestoga. These were altered into gunboats by raising around them perpendicular oak bulwarks, five inches thick and proof against musketry, which were pierced for ports, but bore no iron plating. The boilers were dropped into the hold, and steam-pipes lowered as much as possible. The Tyler mounted six 64-pounders in broadside, and one 32-pounder stern gun; the Lexington, four 64s and two 32s; the Conestoga, two broadside 32s and one light stern gun. After being altered, these vessels were taken down to Cairo, where they arrived August 12th, having been much delayed by the low state of the river; one of them being dragged by the united power of the three over a bar on which was one foot less water than her draught.

On the 7th of August, a contract was made by the War Department with James B. Eads, of St. Louis, by which he [13]undertook to complete seven gunboats, and deliver them at Cairo on the 10th day of October of the same year. These vessels were one hundred and seventy-five feet long and fifty feet beam. The propelling power was one large paddle-wheel, which was placed in an opening prepared for it, midway of the breadth of the vessel and a little forward of the stern, in such wise as to be materially protected by the sides and casemate. This opening, which was eighteen feet wide, extended forward sixty feet from the stern, dividing the after-body into two parts, which were connected abaft the wheel by planking thrown from one side to the other. This after-part was called the fantail. The casemate extended from the curve of the bow to that of the stern, and was carried across the deck both forward and aft, thus forming a square box, whose sides sloped in and up at an angle of forty-five degrees, containing the battery, the machinery, and the paddle-wheel. The casemate was pierced for thirteen guns, three in the forward end ranging directly ahead, four on each broadside, and two stern guns.

As the expectation was to fight generally bows on, the forward end of the casemate carried iron armor two and a half inches thick, backed by twenty-four inches of oak. The rest of the casemate was not protected by armor, except abreast of the boilers and engines, where there were two and a half inches of iron, but without backing. The stern, therefore, was perfectly vulnerable, as were the sides forward and abaft the engines. The latter were high pressure, like those of all Western river-boats, and, though the boilers were dropped into the hold as far as possible, the light draught and easily pierced sides left the vessels exposed in action to the fearful chance of an exploded boiler. Over the casemate forward was a pilot-house of conical shape, built of heavy oak, and plated on the forward side with 2½-inch iron, on the after [14]with 1½-inch. With guns, coal, and stores on board, the casemate deck came nearly down to the water, and the vessels drew from six to seven feet, the peculiar outline giving them no small resemblance to gigantic turtles wallowing slowly along in their native element. Below the water the form was that of a scow, the bottom being flat. Their burden was five hundred and twelve tons.

The armament was determined by the exigencies of the time, such guns as were available being picked up here and there and forwarded to Cairo. The army supplied thirty-five old 42-pounders, which were rifled, and so threw a 70-pound shell. These having lost the metal cut away for grooves, and not being banded, were called upon to endure the increased strain of firing rifled projectiles with actually less strength than had been allowed for the discharge of a round ball of about half the weight. Such make-shifts are characteristic of nations that do not prepare for war, and will doubtless occur again in the experience of our navy; fortunately, in this conflict, the enemy was as ill-provided as ourselves. Several of these guns burst; their crews could be seen eyeing them distrustfully at every fire, and when at last they were replaced by sounder weapons, many were not turned into store, but thrown, with a sigh of relief, into the waters of the Mississippi. The remainder of the armament was made up by the navy with old-fashioned 32-pound and VIII-inch smooth-bore guns, fairly serviceable and reliable weapons. Each of these seven gunboats, when thus ready for service, carried four of the above-described rifles, six 32-pounders of 43 cwt., and three VIII-inch shell-guns; total, thirteen.

The vessels, when received into service, were named after cities standing upon the banks of the rivers which they were to defend—Cairo, Carondelet, Cincinnati, Louisville, Mound [15]City, Pittsburg, St. Louis. They, with the Benton, formed the backbone of the river fleet throughout the war. Other more pretentious, and apparently more formidable, vessels, were built; but from thorough bad workmanship, or appearing too late on the scene, they bore no proportionate share in the fighting. The eight may be fairly called the ships of the line of battle on the western waters.

The Benton was of the same general type as the others, but was purchased by, not built for, the Government. She was originally a snag-boat, and so constructed with special view to strength. Her size was 1,000 tons, double that of the seven; length, 202 feet; extreme breadth, 72 feet. The forward plating was 3 inches of iron, backed by 30 inches of oak; at the stern, and abreast the engines, there was 2½-inch iron, backed by 12 inches of oak; the rest of the sides of the casemates was covered with 5/8-inch iron. With guns and stores on board, she drew nine feet. Her first armament was two IX-inch shell-guns, seven rifled 42s, and seven 32-pounders of 43 cwt.; total, sixteen guns. It will be seen, therefore, that she differed from the others simply in being larger and stronger; she was, indeed, the most powerful fighting-machine in the squadron, but her speed was only five knots an hour through the water, and her engines so little commensurate with her weight that Flag-Officer Foote hesitated long to receive her. The slowness was forgiven for her fitness for battle, and she went by the name of the old war-horse.

There was one other vessel of size equal to the Benton, which, being commanded by a son of Commodore Porter, of the war of 1812, got the name Essex. After bearing a creditable part in the battle of Fort Henry, she became separated by the batteries of Vicksburg from the upper squadron, and is less identified with its history. Her armament was three IX-inch, one X-inch, and one 32-pounder.

[16]On the 6th of September Commander Rodgers was relieved by Captain A.H. Foote, whose name is most prominently associated with the equipment and early operations of the Mississippi flotilla. At that time he reported to the Secretary that there were three wooden gunboats in commission, nine ironclads and thirty-eight mortar-boats building. The mortar-boats were rafts or blocks of solid timber, carrying one XIII-inch mortar.

The construction and equipment of the fleet was seriously delayed by the lack of money, and the general confusion incident to the vast extent of military and naval preparations suddenly undertaken by a nation having a very small body of trained officers, and accustomed to raise and expend comparatively insignificant amounts of money. Constant complaints were made by the officers and contractors that lack of money prevented them from carrying on their work. The first of the seven ironclads was launched October 12th and the seven are returned by the Quartermaster's Department as received December 5, 1861. On the 12th of January, 1862, Flag-Officer Foote reported that he expected to have all the gunboats in commission by the 20th, but had only one-third crews for them. The crews were of a heterogeneous description. In November a draft of five hundred were sent from the seaboard, which, though containing a proportion of men-of-war's men, had a yet larger number of coasting and merchant seamen, and of landsmen. In the West two or three hundred steamboat men, with a few sailors from the Lakes, were shipped. In case of need, deficiencies were made up by drafts from regiments in the army. On the 23d of December, 1861, eleven hundred men were ordered from Washington to be thus detailed for the fleet. Many difficulties, however, arose in making the transfer. General Halleck insisted that the officers of the regiments must accompany their [17]men on board, the whole body to be regarded as marines and to owe obedience to no naval officer except the commander of the gunboat. Foote refused this, saying it would be ruinous to discipline; that the second in command, or executive officer, by well-established naval usage, controlled all officers, even though senior in rank to himself; and that there were no quarters for so many more officers, for whom, moreover, he had no use. Later on Foote writes to the Navy Department that not more than fifty men had joined from the army, though many had volunteered; the derangement of companies and regiments being the reason assigned for not sending the others. It does not appear that more than these fifty came at that time. There is no more unsatisfactory method of getting a crew than by drafts from the commands of other men. Human nature is rarely equal to parting with any but the worst; and Foote had so much trouble with a subsequent detachment that he said he would rather go into action half manned than take another draft from the army. In each vessel the commander was the only trained naval officer, and upon him devolved the labor of organizing and drilling this mixed multitude. In charge of and responsible for the whole was the flag-officer, to whom, though under the orders of General Fremont, the latter had given full discretion.

Meanwhile the three wooden gunboats had not been idle during the preparation of the main ironclad fleet. Arriving at Cairo, as has been stated, on the 12th of August, the necessity for action soon arose. During the early months of the war the State of Kentucky had announced her intention of remaining a neutral between the contending parties. Neither of the latter was willing to precipitate her, by an invasion of her soil, into the arms of the other, and for some time the operations of the Confederates were confined to [18]Tennessee, south of her borders, the United States troops remaining north of the Ohio. On September 4th, however, the Confederates crossed the line and occupied in force the bluffs at Columbus and Hickman, which they proceeded at once to fortify. The military district about Cairo was then under the command of General Grant, who immediately moved up the Ohio, and seized Paducah, at the mouth of the Tennessee River, and Smithland, at the mouth of the Cumberland. These two rivers enter the Ohio ten miles apart, forty and fifty miles above Cairo. Rising in the Cumberland and Alleghany Mountains, their course leads through the heart of Tennessee, to which their waters give easy access through the greater part of the year. Two gunboats accompanied this movement, in which, however, there was no fighting.

On the 10th of September, the Lexington, Commander Stembel, and Conestoga, Lieutenant-Commanding Phelps, went down the Mississippi, covering an advance of troops on the Missouri side. A brisk cannonade followed between the boats and the Confederate artillery, and shots were exchanged with the gunboat Yankee. On the 24th, Captain Foote, by order of General Fremont, moved in the Lexington up the Ohio River to Owensboro. The Conestoga was to have accompanied this movement, but she was up the Cumberland or Tennessee at the time; arriving later she remained, by order, at Owensboro till the falling of the river compelled her to return, there being on some of the bars less water than she drew. A few days later this active little vessel showed herself again on the Mississippi, near Columbus, endeavoring to reach a Confederate gunboat that lay under the guns of the works; then again on the Tennessee, which she ascended as far as the Tennessee State Line, reconnoitring Fort Henry, subsequently the scene of Foote's first decisive victory over the enemy. Two days later the Cumberland was entered for [19]the distance of sixty miles. On the 28th of October, accompanied by a transport and some companies of troops, she again ascended the Cumberland, and broke up a Confederate camp, the enemy losing several killed and wounded. The frequent appearances of these vessels, while productive of no material effect beyond the capture or destruction of Confederate property, were of service in keeping alive the attachment to the Union where it existed. The crews of the gunboats also became accustomed to the presence of the enemy, and to the feeling of being under fire.

On the 7th of November a more serious affair took place. The evening before, the gunboats Tyler, Commander Walke, and Lexington, Commander Stembel, convoyed transports containing three thousand troops, under the command of General Grant, down the Mississippi as far as Norfolk, eight miles, where they anchored on the east side of the river. The following day the troops landed at Belmont, which is opposite Columbus and under the guns of that place. The Confederate troops were easily defeated and driven to the river's edge, where they took refuge on their transports. During this time the gunboats engaged the batteries on the Iron Banks, as the part of the bluff above the town is called. The heavy guns of the enemy, from their commanding position, threw easily over the boats, reaching even to and beyond the transports on the opposite shore up stream. Under Commander Walke's direction the transports were moved further up, out of range.

Meanwhile the enemy was pushing reinforcements across the stream below the works, and the Union forces, having accomplished the diversion which was the sole object of the expedition, began to fall back to their transports. It would seem that the troops, yet unaccustomed to war, had been somewhat disordered by their victory, so that the return was [20]not accomplished as rapidly as was desirable, the enemy pressing down upon the transports. At this moment the gunboats, from a favorable position, opened upon them with grape, canister, and five-second shell, silencing them with great slaughter. When the transports were under way the two gunboats followed in the rear, covering the retreat till the enemy ceased to follow.

In this succession of encounters the Tyler lost one man killed and two wounded. The Lexington escaped without loss.

When a few miles up the river on the return, General McClernand, ascertaining that some of the troops had not embarked, directed the gunboats to go back for them, the general himself landing to await their return. This service was performed, some 40 prisoners being taken on board along with the troops.

In his official report of this, the first of his many gallant actions on the rivers, Commander Walke praises warmly the efficiency as well as the zeal of the crews of the gunboats, though as yet so new to their duties.

The flotilla being at this time under the War Department, as has been already stated, its officers, each and all, were liable to orders from any army officer of superior rank to them. Without expressing a decided opinion as to the advisability of this arrangement under the circumstances then existing, it was entirely contrary to the established rule by which, when military and naval forces are acting together, the commander of each branch decides what he can or can not do, and is not under the control of the other, whatever the relative rank. At this time Captain Foote himself had only the rank of colonel, and found, to use his own expression, that "every brigadier could interfere with him." On the 13th of November, 1861, he received the appointment [21]of flag-officer, which gave him the same rank as a major-general, and put him above the orders of any except the commander-in-chief of the department. Still the subordinate naval officers were liable to orders at any time from any general with whom they might be, without the knowledge of the flag-officer. It is creditable to the good feeling and sense of duty of both the army and navy that no serious difficulty arose from this anomalous condition of affairs, which came to an end in July, 1862, when the fleet was transferred to the Navy Department.

After the battle of Belmont nothing of importance occurred in the year 1861. The work on the ironclads was pushed on, and there are traces of the reconnoissances by the gunboats in the rivers. In January, 1862, some tentative movements, having no particular result, were made in the direction of Columbus and up the Tennessee. There was a great desire to get the mortar-boats completed, but they were not ready in time for the opening operations at Fort Henry and Donelson, their armaments not having arrived.

On the 2d of February, Flag-Officer Foote left Cairo for Paducah, arriving the same evening. There were assembled the four armored gunboats, Essex, Commander Wm. D. Porter; Carondelet, Commander Walke; St. Louis, Lieutenant Paulding; and Cincinnati, Commander Stembel; as well as the three wooden gunboats, Conestoga, Lieutenant Phelps; Tyler, Lieutenant Gwin; and Lexington, Lieutenant Shirk. The object of the expedition was to attack, conjointly with the army, Fort Henry on the Tennessee, and, after reducing the fort, to destroy the railroad bridge over the river connecting Bowling Green with Columbus. The flag-officer deplored that scarcity of men prevented his coming with four other boats, but to man those he brought it had been necessary to strip Cairo of all men except a crew for one gunboat. [22]Only 50 men of the 1,100 promised on December 23d had been received from the army.

Fort Henry was an earthwork with five bastions, situated on the east bank of the Tennessee River, on low ground, but in a position where a slight bend in the stream gave it command of the stretch below for two or three miles. It mounted twenty guns, but of these only twelve bore upon the ascending fleet. These twelve were: one X-inch columbiad, one 60-pounder rifle, two 42- and eight 32-pounders. The plan of attack was simple. The armored gunboats advanced in the first order of steaming, in line abreast, fighting their bow guns, of which eleven were brought into action by the four. The flag-officer purposed by continually advancing, or, if necessary, falling back, to constantly alter the range, thus causing error in the elevation of the enemy's guns, presenting, at the same time, the least vulnerable part, the bow, to his fire. The vessels kept their line by the flag-ship Cincinnati. The other orders were matters of detail, the most important being to fire accurately rather than with undue rapidity. The wooden gunboats formed a second line astern, and to the right of the main division.

Two days previous to the action there were heavy rains which impeded the movements of the troops, caused the rivers to rise, and brought down a quantity of drift-wood and trees. The same flood swept from their moorings a number of torpedoes, planted by the Confederates, which were grappled with and towed ashore by the wooden gunboats.

Half an hour after noon on the 6th, the fleet, having waited in vain for the army, which was detained by the condition of the roads, advanced to the attack. The armored vessels opened fire, the flag-ship beginning, at seventeen hundred yards distance, and continued steaming steadily ahead to within six hundred yards of the fort. As the [23]distance decreased, the fire on both sides increased in rapidity and accuracy. An hour after the action began the 60-pound rifle in the fort burst, and soon after the priming wire of the 10-inch columbiad jammed and broke in the vent, thus spiking the gun, which could not be relieved. The balance of force was, however, at once more than restored, for a shot from the fort pierced the casemate of the Essex over the port bow gun, ranged aft, and killing a master's mate in its flight, passed through the middle boiler. The rush of high-pressure steam scalded almost all in the forward part of the casemate, including her commander and her two pilots in the pilot-house. Many of the victims threw themselves into the water, and the vessel, disabled, drifted down with the current out of action. The contest was vigorously continued by the three remaining boats, and at 1.45 P.M. the Confederate flag was lowered. The commanding officer, General Tilghman, came on board and surrendered the fort and garrison to the fleet; but the greater part of the Confederate forces had been previously withdrawn to Fort Donelson, twelve miles distant, on the Cumberland. Upon the arrival of the army the fort and material captured were turned over to the general commanding.

In this sharp and decisive action the gunboats showed themselves well fitted to contend with most of the guns at that time to be found upon the rivers, provided they could fight bows on. Though repeatedly struck, the flag-ship as often as thirty-one times, the armor proved sufficient to deflect or resist the impact of the projectiles. The disaster, however, that befell the Essex made fearfully apparent a class of accidents to which they were exposed, and from which more than one boat, on either side, on the Western waters subsequently suffered. The fleet lost two killed and nine wounded, besides twenty-eight scalded, many of whom died. [24]The Essex had also nineteen soldiers on board; nine of whom were scalded, four fatally.

The surrender of the fort was determined by the destruction of its armament. Of the twelve guns, seven, by the commander's report, were disabled when the flag was hauled down. One had burst in discharging, the rest were put out of action by the fire of the fleet. The casualties were few, not exceeding twenty killed and wounded.

Flag-Officer Foote, having turned over his capture to the army, returned the same evening to Cairo with three armored vessels, leaving the Carondelet. At the same time the three wooden gunboats, in obedience to orders issued before the battle, started up river under the command of Lieutenant Phelps, reaching the railroad bridge, twenty-five miles up, after dark. Here the machinery for turning the draw was found to be disabled, while on the other side were to be seen some transport steamers escaping up stream. An hour was required to open the draw, when two of the boats proceeded in chase of the transports, the Tyler, as the slowest, being left to destroy the track as far as possible. Three of the Confederate steamers, loaded with military stores, two of them with explosives, were run ashore and fired. The Union gunboats stopped half a mile below the scene, but even at that distance the force of the explosion shattered glasses, forced open doors, and raised the light upper decks.

The Lexington, having destroyed the trestle-work at the end of the bridge, rejoined the following morning; and the three boats, continuing their raid, arrived the next night at Cerro Gordo, near the Mississippi line. Here was seized a large steamer called the Eastport, which the Confederates were altering into a gunboat. There being at this point large quantities of lumber, the Tyler was left to ship it and guard the prize.

[25]The following day, the 8th, the two boats continued up river, passing through the northern part of the States of Mississippi and Alabama, to Florence, where the Muscle Shoals prevented their farther progress. On the way two more steamers were seized, and three were set on fire by the enemy as they approached Florence. Returning the same night, upon information received that a Confederate camp was established at Savannah, Tennessee, on the bank of the river, a party was landed, which found the enemy gone, but seized or destroyed the camp equipage and stores left behind. The expedition reached Cairo again on the 11th, bringing with it the Eastport and one other of the captured steamers. The Eastport had been intended by the Confederates for a gunboat, and was in process of conversion when captured. Lieutenant Phelps reported her machinery in first-rate order and the boilers dropped into the hold. Her hull had been sheathed with oak planking and the bulkheads, forward, aft, and thwartships, were of oak and of the best workmanship. Her beautiful model, speed, and manageable qualities made her specially desirable for the Union fleet, and she was taken into the service. Two years later she was sunk by torpedoes in the Red River, and, though partially raised, it was found impossible to bring her over the shoals that lay below her. She was there blown up, her former captor and then commander, Lieutenant Phelps, applying the match.

Lieutenant Phelps and his daring companions returned to Cairo just in time to join Foote on his way to Fort Donelson. The attack upon this position, which was much stronger than Fort Henry, was made against the judgment of the flag-officer, who did not consider the fleet as yet properly prepared. At the urgent request of Generals Halleck and Grant, however, he steamed up the Cumberland River [26]with three ironclads and the wooden gunboats, the Carondelet having already, at Grant's desire, moved round to Donelson.

Fort Donelson was on the left bank of the Cumberland, twelve miles southeast of Fort Henry. The main work was on a bluff about a hundred feet high, at a bend commanding the river below. On the slope of the ridge, looking down stream, were two water batteries, with which alone the fleet had to do. The lower and principal one mounted eight 32-pounders and a X-inch columbiad; in the upper there were two 32-pounder carronades and one gun of the size of a X-inch smooth-bore, but rifled with the bore of a 32-pounder and said to throw a shot of one hundred and twenty-eight pounds. Both batteries were excavated in the hillside, and the lower had traverses between the guns to protect them from an enfilading fire, in case the boats should pass their front and attack them from above. At the time of the fight these batteries were thirty-two feet above the level of the river.

General Grant arrived before the works at noon of February 12th. The gunboat Carondelet, Commander Walke, came up about an hour earlier. At 10 A.M. on the 13th, the gunboat, at the general's request, opened fire on the batteries at a distance of a mile and a quarter, sheltering herself partly behind a jutting point of the river, and continued a deliberate cannonade with her bow guns for six hours, after which she withdrew. In this time she had thrown in one hundred and eighty shell, and was twice struck by the enemy, half a dozen of her people being slightly injured by splinters. On the side of the enemy an engineer officer was killed by her fire.

The fleet arrived that evening, and attacked the following day at 3 P.M. There were, besides the Carondelet, the [27]armored gunboats St. Louis, Lieutenant Paulding; Louisville, Commander Dove; and Pittsburg, Lieutenant E. Thompson; and the wooden vessels Conestoga and Tyler, commanded as before. The order of steaming was the same as at Henry, the wooden boats in the rear throwing their shell over the armored vessels. The fleet reserved its fire till within a mile, when it opened and advanced rapidly to within six hundred yards of the works, closing up later to four hundred yards. The fight was obstinately sustained on both sides, and, notwithstanding the commanding position of the batteries, strong hopes were felt on board the fleet of silencing the guns, which the enemy began to desert, when, at 4.30 P.M., the wheel of the flag-ship St. Louis and the tiller of the Louisville were shot away. The two boats, thus rendered unmanageable, drifted down the river; and their consorts, no longer able to maintain the unequal contest, withdrew. The enemy returned at once to their guns, and inflicted much injury on the retiring vessels.

Notwithstanding its failure, the tenacity and fighting qualities of the fleet were more markedly proved in this action than in the victory at Henry. The vessels were struck more frequently (the flag-ship fifty-nine times, and none less than twenty), and though the power of the enemy's guns was about the same in each case, the height and character of the soil at Donelson placed the fleet at a great disadvantage. The fire from above, reaching their sloping armor nearly at right angles, searched every weak point. Upon the Carondelet a rifled gun burst. The pilot-houses were beaten in, and three of the four pilots received mortal wounds. Despite these injuries, and the loss of fifty-four killed and wounded, the fleet was only shaken from its hold by accidents to the steering apparatus, after which their batteries could not be brought to bear.

[28]Among the injured on this occasion was the flag-officer, who was standing by the pilot when the latter was killed. Two splinters struck him in the arm and foot, inflicting wounds apparently slight; but the latter, amid the exposure and anxiety of the succeeding operations, did not heal, and finally compelled him, three months later, to give up the command.

On the 16th the Confederates, after an unsuccessful attempt to cut their way through the investing army, hopeless of a successful resistance, surrendered at discretion to General Grant. The capture of this post left the way open to Nashville, the capital of Tennessee, and the flag-officer was anxious to press on with fresh boats brought up from Cairo; but was prevented by peremptory orders from General Halleck, commanding the Department. As it was, however, Nashville fell on the 25th.

After the fall of Fort Donelson and the successful operations in Missouri, the position at Columbus was no longer tenable. On the 23d Flag-Officer Foote made a reconnoissance in force in that direction, but no signs of the intent to abandon were as yet perceived. On March 1st, Lieutenant Phelps, being sent with a flag of truce, reported the post in process of being evacuated, and on the 4th it was in possession of the Union forces. The Confederates had removed the greater part of their artillery to Island No. 10.

About this time, March 1st, Lieutenant Gwin, commanding the Lexington and Tyler on the Tennessee, hearing that the Confederates were fortifying Pittsburg Landing, proceeded to that point, carrying with him two companies of sharpshooters. The enemy was readily dislodged, and Lieutenant Gwin continued in the neighborhood to watch and frustrate any similar attempts. This was the point chosen a few weeks later for the concentration of the Union army, to [29]which Lieutenant Gwin was again to render invaluable service.

After the fall of Columbus no attempt was made to hold Hickman, but the Confederates fell back upon Island No. 10 and the adjacent banks of the Mississippi to make their next stand for the control of the river. The island, which has its name (if it can be called a name) from its position in the numerical series of islands below Cairo, is just abreast the line dividing Kentucky from Tennessee. The position was singularly strong against attacks from above, and for some time before the evacuation of Columbus the enemy, in anticipation of that event, had been fortifying both the island and the Tennessee and Missouri shores. It will be necessary to describe the natural features and the defences somewhat in detail.

From a point about four miles above Island No. 10 the river flows

south three miles, then sweeps round to the west and north, forming a

horse-shoe bend of which the two ends are east and west from each

other. Where the first horse-shoe ends a second begins; the river

continuing to flow north, then west and south to Point Pleasant on the

Missouri shore. The two bends taken together form an inverted S

( ). In making this detour, the river, as far as Point

Pleasant, a distance of twelve miles, gains but three miles to the

south. Island No. 10 lay at the bottom of the first bend, near the

left bank. It was about two miles long by one-third that distance

wide, and its general direction was nearly east and west. New Madrid,

on the Missouri bank, is in the second bend, where the course of the

river is changing from west to south. The right bank of the stream is

in Missouri, the left bank partly in Kentucky and partly in Tennessee.

From Point Pleasant the river runs southeast to Tiptonville, in

Tennessee, the extreme point of the ensuing operations.

). In making this detour, the river, as far as Point

Pleasant, a distance of twelve miles, gains but three miles to the

south. Island No. 10 lay at the bottom of the first bend, near the

left bank. It was about two miles long by one-third that distance

wide, and its general direction was nearly east and west. New Madrid,

on the Missouri bank, is in the second bend, where the course of the

river is changing from west to south. The right bank of the stream is

in Missouri, the left bank partly in Kentucky and partly in Tennessee.

From Point Pleasant the river runs southeast to Tiptonville, in

Tennessee, the extreme point of the ensuing operations.

[30]When Columbus fell the whole of this position was in the hands of the Confederates, who had fortified themselves at New Madrid, and thrown up batteries on the island as well as on the Tennessee shore above it. On the island itself were four batteries mounting twenty-three guns, on the Tennessee shore six batteries mounting thirty-two guns. There was also a floating battery, which, at the beginning of operations, was moored abreast the middle of the island, and is variously reported as carrying nine or ten IX-inch guns. New Madrid, with its works, was taken by General Pope before the arrival of the flotilla.

The position of the enemy, though thus powerful against attack, was one of great isolation. From Hickman a great swamp, which afterward becomes Reelfoot Lake, extends along the left bank of the Mississippi, discharging its waters into the river forty miles below Tiptonville. A mile below Tiptonville begin the great swamps, extending down both sides of the Mississippi for a distance of sixty miles. The enemy therefore had the river in his front, and behind him a swamp, impassable to any great extent for either men or supplies in the then high state of the river. The only way of receiving help, or of escaping, in case the position became untenable, was by way of Tiptonville, to which a good road led. It will be remembered that between New Madrid and Point Pleasant there is a low ridge of land, rising from one to fifteen feet above overflow.

As soon as New Madrid was reduced, General Pope busied himself in establishing a series of batteries at several prominent points along the right bank, as far down as opposite Tiptonville. The river was thus practically closed to the enemy's transports, for their gunboats were unable to drive out the Union gunners. Escape was thus rendered impracticable, and the ultimate reduction of the place assured; but [31]to bring about a speedy favorable result it was necessary for the army to cross the river and come upon the rear of the enemy. The latter, recognizing this fact, began the erection of batteries along the shore from the island down to Tiptonville.

On the 15th of March the fleet arrived in the neighborhood of Island No. 10. There were six ironclads, one of which was the Benton carrying the flag-officer's flag, and ten mortar-boats. The weather was unfavorable for opening the attack, but on the 16th the mortar boats were placed in position, reaching at extreme range all the batteries, as well on the Tennessee shore as on the island. On the 17th an attack was made by all the gunboats, but at the long range of two thousand yards. The river was high and the current rapid, rendering it very difficult to manage the boats. A serious injury, such as had been received at Henry and at Donelson, would have caused the crippled boat to drift at once into the enemy's arms; and an approach nearer than that mentioned would have exposed the unarmored sides of the vessels, their most vulnerable parts, to the fire of the batteries. The fleet of the flag-officer was thought none too strong to defend the Upper Mississippi Valley against the enemy's gunboats, of whose number and power formidable accounts were continually received; while the fall of No. 10 would necessarily be brought about in time, as that of Fort Pillow afterward was, by the advance of the army through Tennessee. Under these circumstances, it cannot be doubted that Foote was justified in not exposing his vessels to the risks of a closer action; but to a man of his temperament the meagre results of long-range firing must have been peculiarly trying.

The bombardment continued throughout the month. Meanwhile the army under Pope was cutting a canal through the swamps on the Missouri side, by which, when completed [32]on the 4th of April, light transport steamers were able to go from the Mississippi above, to New Madrid below, Island No. 10 without passing under the batteries.

On the night of the 1st of April an armed boat expedition, under the command of Master J.V. Johnson, carrying, besides the boat's crew, fifty soldiers under the command of Colonel Roberts of the Forty-second Illinois Regiment, landed at the upper battery on the Tennessee shore. No resistance was experienced, and, after the guns had been spiked by the troops, the expedition returned without loss to the ships. In a despatch dated March 20th the flag-officer had written: "When the object of running the blockade becomes adequate to the risk I shall not hesitate to do it." With the passage of the transports through the canal, enabling the troops to cross if properly protected, the time had come. The exploit of Colonel Roberts was believed to have disabled one battery, and on the 4th of the month, the floating battery before the island, after a severe cannonade by the gunboats and mortars, cut loose from her moorings and drifted down the river. It is improbable that she was prepared, in her new position, for the events of the night.

At ten o'clock that evening the gunboat Carondelet, Commander Henry Walke, left her anchorage, during a heavy thunder-storm, and successfully ran the batteries, reaching New Madrid at 1 A.M. The orders to execute this daring move were delivered to Captain Walke on the 30th of March. The vessel was immediately prepared. Her decks were covered with extra thicknesses of planking; the chain cables were brought up from below and ranged as an additional protection. Lumber and cord-wood were piled thickly round the boilers, and arrangements made for letting the steam escape through the wheel-houses, to avoid the puffing noise ordinarily issuing from the pipes. The pilot-house, for [33]additional security, was wrapped to a thickness of eighteen inches in the coils of a large hawser. A barge, loaded with bales of hay, was made fast on the port quarter of the vessel, to protect the magazine.

The moon set at ten o'clock, and then too was felt the first breath of a thunder-storm, which had been for some time gathering. The Carondelet swung from her moorings and started down the stream. The guns were run in and ports closed. No light was allowed about the decks. Within the darkened casemate or the pilot-house all her crew, save two, stood in silence, fully armed to repel boarding, should boarding be attempted. The storm burst in full violence as soon as her head was fairly down stream. The flashes of lightning showed her presence to the Confederates who rapidly manned their guns, and whose excited shouts and commands were plainly heard on board as the boat passed close under the batteries. On deck, exposed alike to the storm and to the enemy's fire, were two men; one, Charles Wilson, a seaman, heaving the lead, standing sometimes knee-deep in the water that boiled over the forecastle; the other, an officer, Theodore Gilmore, on the upper deck forward, repeating to the pilot the leadsman's muttered "No bottom." The storm spread its sheltering wing over the gallant vessel, baffling the excited efforts of the enemy, before whose eyes she floated like a phantom ship; now wrapped in impenetrable darkness, now standing forth in the full blaze of the lightning close under their guns. The friendly flashes enabled her pilot, William E. Hoel, who had volunteered from another gunboat to share the fortunes of the night, to keep her in the channel; once only, in a longer interval between them, did the vessel get a dangerous sheer toward a shoal, but the peril was revealed in time to avoid it. Not till the firing had ceased did the squall abate.

[34]The passage of the Carondelet was not only one of the most daring and dramatic events of the war; it was also the death-blow to the Confederate defence of this position. The concluding events followed in rapid succession. Having passed the island, as related, on the night of the 4th, the Carondelet on the 6th made a reconnoissance down the river as far as Tiptonville, with General Granger on board, exchanging shots with the Confederate batteries, at one of which a landing was made and the guns spiked. That night the Pittsburg also passed the island, and at 6.30 A.M. of the 7th the Carondelet got under way, in concert with Pope's operations, went down the river, followed after an interval by the Pittsburg, and engaged the enemy's batteries, beginning with the lowest. This was silenced in three-quarters of an hour, and the others made little resistance. The Carondelet then signalled her success to the general and returned to cover the crossing of the army, which began at once. The enemy evacuated their works, pushing down toward Tiptonville, but there were actually no means for them to escape, caught between the swamps and the river. Seven thousand men laid down their arms, three of whom were general officers. At ten o'clock that evening the island and garrison surrendered to the navy, just three days to an hour after the Carondelet started on her hazardous voyage. How much of this result was due to the Carondelet and Pittsburg may be measured by Pope's words to the flag-officer: "The lives of thousands of men and the success of our operations hang upon your decision; with two gunboats all is safe, with one it is uncertain."

The passage of a vessel before the guns of a fortress under cover of night came to be thought less dangerous in the course of the war. To do full justice to the great gallantry shown by Commander Walke, it should be remembered that [35]this was done by a single vessel three weeks before Farragut passed the forts down the river with a fleet, among the members of which the enemy's fire was distracted and divided; and that when Foote asked the opinion of his subordinate commanders as to the advisability of making the attempt, all, save one, "believed that it would result in the almost certain destruction of the boats, passing six forts under the fire of fifty guns." This was also the opinion of Lieutenant Averett, of the Confederate navy, who commanded the floating battery at the island—a young officer, but of clear and calm judgment. "I do not believe it is impossible," he wrote to Commodore Hollins, "for the enemy to run a part of his gunboats past in the night; but those that I have seen are slow and hard to turn, and it is probable that he would lose some, if not all, in the attempt." Walke alone in the council of captains favored the trial, though the others would doubtless have undertaken it as cheerfully as he did. The daring displayed in this deed, which, to use the flag-officer's words, Walke "so willingly undertook," must be measured by the then prevalent opinion and not in the light of subsequent experience. Subsequent experience, indeed, showed that the danger, if over-estimated, was still sufficiently great.

Justly, then, did it fall to Walke's lot to bear the most conspicuous part in the following events, ending with the surrender. No less praise, however, is due to the flag-officer for the part he bore in this, the closing success of his career. There bore upon him the responsibility of safe-guarding all the Upper Mississippi, with its tributary waters, while at the same time the pressure of public opinion, and the avowed impatience of the army officer with whom he was co-operating, were stinging him to action. He had borne for months the strain of overwork with inadequate tools; his health was [36]impaired, and his whole system disordered from the effects of his unhealed wound. Farragut had not then entered the mouth of the Mississippi, and the result of his enterprise was yet in the unknown future. Reports, now known to be exaggerated, but then accepted, magnified the power of the Confederate fleet in the lower waters. Against these nothing stood, nor was soon likely, as it then seemed, to stand except Foote's ironclads. He was right, then, in his refusal to risk his vessels. He showed judgment and decision in resisting the pressure, amounting almost to a taunt, brought upon him. Then, when it became evident that the transports could be brought through the canal, he took what he believed to be a desperate risk, showing that no lack of power to assume responsibility had deterred him before.

In the years since 1862, Island No. 10, the scene of so much interest and energy, has disappeared. The river, constantly wearing at its upper end, has little by little swept away the whole, and the deep current now runs over the place where the Confederate guns stood, as well as through the channel by which the Carondelet passed. On the other shore a new No. 10 has risen, not standing as the old one, in the stream with a channel on either side, but near a point and surrounded by shoal water. It has perhaps gathered around a steamer, which was sunk by the Confederates to block the passage through a chute then existing across the opposite point.

While Walke was protecting Pope's crossing, two other gunboats were rendering valuable service to another army a hundred miles away, on the Tennessee River. The United States forces at Pittsburg Landing, under General Grant, were attacked by the Confederates in force in the early morning of April 6th. The battle continued with fury all day, the enemy driving the centre of the army back half way from [37]their camps to the river, and at a late hour in the afternoon making a desperate attempt to turn the left, so as to get possession of the landing and transports. Lieutenant Gwin, commanding the Tyler, and senior officer present, sent at 1.30 P.M. to ask permission to open fire. General Hurlburt, commanding on the left, indicated, in reply, the direction of the enemy and of his own forces, saying, at the same time, that without reinforcements he would not be able to maintain his then position for an hour. At 2.50 the Tyler opened fire as indicated, with good effect, silencing their batteries. At 3.50 the Tyler ceased firing to communicate with General Grant, who directed her commander to use his own judgment. At 4 P.M. the Lexington, Lieutenant Shirk, arrived, and the two boats began shelling from a position three-quarters of a mile above the landing, silencing the Confederate batteries in thirty minutes. At 5.30 P.M., the enemy having succeeded in gaining a position on the Union left, an eighth of a mile above the landing and half a mile from the river, both vessels opened fire upon them, in conjunction with the field batteries of the army, and drove them back in confusion.

The army being largely outnumbered during the day, and forced steadily back, the presence and services of the two gunboats, when the most desperate attacks of the enemy were made, were of the utmost value, and most effectual in enabling that part of our line to be held until the arrival of the advance of Buell's army from Nashville, about 5 P.M., allowed the left to be reinforced and restored the fortunes of the day. During the night, by request of General Nelson, the gunboats threw a shell every fifteen minutes into the camp of the enemy.

Considering the insignificant and vulnerable character of these two wooden boats, it may not be amiss to quote the language of the two commanders-in-chief touching their [38]services; the more so as the gallant young officers who directed their movements are both dead, Gwin, later in the war, losing his life in action. General Grant says: "At a late hour in the afternoon a desperate attempt was made to turn our left and get possession of the landing, transports, etc. This point was guarded by the gunboats Tyler and Lexington, Captains Gwin and Shirk, United States Navy, commanding, four 20-pounder Parrotts, and a battery of rifled guns. As there is a deep and impassable ravine for artillery and cavalry, and very difficult for infantry, at this point, no troops were stationed here, except the necessary artillerists and a small infantry force for their support. Just at this moment the advance of Major-General Buell's column (a part of the division under General Nelson) arrived, the two generals named both being present. An advance was immediately made upon the point of attack, and the enemy soon driven back. In this repulse much is due to the presence of the gunboats." In the report in which these words occur it is unfortunately not made clear how much was due to the gunboats before Buell and Nelson arrived.

The Confederate commander, on the other hand, states that, as the result of the attack on the left, the "enemy broke and sought refuge behind a commanding eminence covering the Pittsburg Landing, not more than half a mile distant, under the guns of the gunboats, which opened a fierce and annoying fire with shot and shell of the heaviest description." Among the reasons for not being able to cope with the Union forces next day, he alleges that "during the night the enemy broke the men's rest by a discharge, at measured intervals, of heavy shells thrown from the gunboats;" and further on he speaks of the army as "sheltered by such an auxiliary as their gunboats." The impression among Confederates there present was that the gunboats saved the army by saving the [39]landing and transports, while during the night the shrieking of the VIII-inch shells through the woods, tearing down branches and trees in their flight, and then sharply exploding, was demoralizing to a degree. The nervous strain caused by watching for the repetition, at measured intervals, of a painful sensation is known to most.

General Hurlburt, commanding on the left during the fiercest of the onslaught, and until the arrival of Buell and Nelson, reports: "From my own observation and the statement of prisoners his (Gwin's) fire was most effectual in stopping the advance of the enemy on Sunday afternoon and night."

Island No. 10 fell on the 7th. On the 11th Foote started down the river with the flotilla, anchoring the evening of the 12th fifty miles from New Madrid, just below the Arkansas line. Early the next morning General Pope arrived with 20,000 men. At 8 A.M. five Confederate gunboats came in sight, whereupon the flotilla weighed and advanced to meet them. After exchanging some twenty shots the Confederates retreated, pursued by the fleet to Fort Pillow, thirty miles below, on the first, or upper Chickasaw bluff. The flag-officer continued on with the gunboats to within a mile of the fort, making a leisurely reconnoissance, during which he was unmolested by the enemy. The fleet then turned, receiving a few harmless shots as they withdrew, and tied up to the Tennessee bank, out of range.

The following morning the mortar-boats were placed on the Arkansas side, under the protection of gunboats, firing as soon as secured. The army landed on the Tennessee bank above the fort, and tried to find a way by which the rear of the works could be reached, but in vain. Plans were then arranged by which it was hoped speedily to reduce the place by the combined efforts of army and navy; but these [40]were frustrated by Halleck's withdrawal of all Pope's forces, except 1,500 men under command of a colonel. From this time the attacks on the fort were confined to mortar and long-range firing. Reports of the number and strength of the Confederate gunboats and rams continued to come in, generally much exaggerated; but on the 27th news of Farragut's successful passage of the forts below New Orleans, and appearance before that city, relieved Foote of his most serious apprehensions from below.

On the 23d, Captain Charles H. Davis arrived, to act as second in command to the flag-officer, and on the 9th of May the latter, whose wound, received nearly three months before at Donelson, had become threatening, left Davis in temporary command and went North, hoping to resume his duties with the flotilla at no distant date. It was not, however, so to be. An honorable and distinguished career of forty years afloat ended at Fort Pillow. Called a year later to a yet more important command, he was struck down by the hand of death at the instant of his departure to assume it. His services in the war were thus confined to the Mississippi flotilla. Over the birth and early efforts of that little fleet he had presided; upon his shoulders had fallen the burden of anxiety and unremitting labor which the early days of the war, when all had to be created, everywhere entailed. He was repaid, for under him its early glories were achieved and its reputation established; but the mental strain and the draining wound, so long endured in a sickly climate, hastened his end.

The Confederate gunboats, heretofore acting upon the river at Columbus and Island No. 10, were in the regular naval service under the command of Flag Officer George N. Hollins, formerly of the United States Navy. At No. 10 the force consisted of the McRae, Polk, Jackson, Calhoun, Ivy, Ponchartrain, Maurepas, and Livingston; the floating battery [41]had also formed part of his command. Hollins had not felt himself able to cope with the heavy Union gunboats. His services had been mainly confined to a vigorous but unsuccessful attack upon the batteries established by Pope on the Missouri shore, between New Madrid and Tiptonville, failing in which the gunboats fell back down the river. They continued, however, to make frequent night trips to Tiptonville with supplies for the army, in doing which Pope's comparatively light batteries did not succeed in injuring them, the river being nearly a mile wide. The danger then coming upon New Orleans caused some of these to be withdrawn, and at the same time a novel force was sent up from that city to take their place and dispute the control of the river with Foote's flotilla.