The Project Gutenberg EBook of French Pathfinders in North America, by William Henry Johnson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: French Pathfinders in North America Author: William Henry Johnson Release Date: May 20, 2007 [EBook #21543] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRENCH PATHFINDERS *** Produced by Al Haines

The compiler of the following sketches does not make any claim to originality. He has dealt with material that has been used often and again. Still there has seemed to him to be a place for a book which should outline the story of the great French explorers in such simple, direct fashion as might attract young readers. Trying to meet this need, he has sought to add to the usefulness of the volume by introductory chapters, simple in language, but drawn from the best authorities and carefully considered, giving a view of Indian society; also, by inserting numerous notes on Indian tribal connections, customs, and the like subjects.

By selecting a portion of Radisson's journal for publication he does not by any means range himself on the side of the scholarly and gifted writer who has come forward as the champion of that picturesque scoundrel, and seriously proposes {vi} him as the real hero of the Northwest, to whom, we are told, is due the honor which we have mistakenly lavished on such commonplace persons as Champlain, Joliet, Marquette, and La Salle.

While the present writer is not qualified to express a critical opinion as to the merits of the controversy about Radisson, a careful reading of his journal has given him an impression that the greatest part is so vague, so wanting in verifiable details, as to be worthless for historical purposes. One portion, however, seems unquestionably valuable, besides being exceedingly interesting. It is that which recounts his experiences on Lake Superior. It bears the plainest marks of truth and authenticity, and it is accepted as historical by the eminent critic, Dr. Reuben G. Thwaites. Therefore it is reproduced here, in abridged form; and on the strength of it Radisson is assigned a place among the Pathfinders.

|

JACQUES CARTIER From the original painting by P. Riis in the Town Hall of St. Malo, France |

Frontispiece |

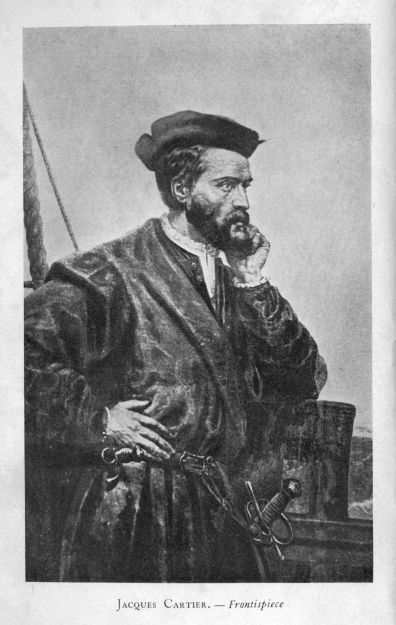

| Indian Family Tree | 23 |

|

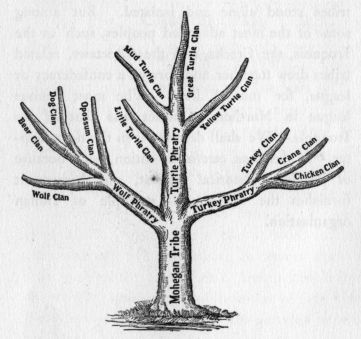

FORT CAROLINE

From De Bry's "Le Moyne de Bienville" |

82 |

|

SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN

From the Ducornet portrait |

104 |

|

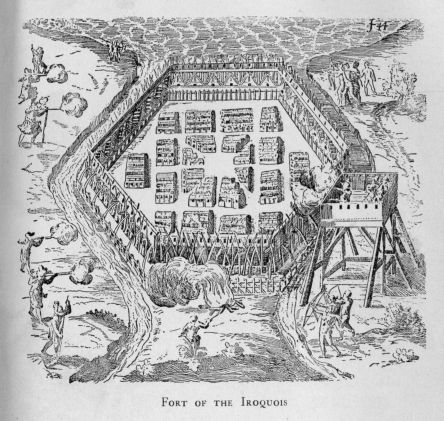

FORT OF THE IROQUOIS

From Laverdière's "Oeuvres de Champlain" |

129 |

|

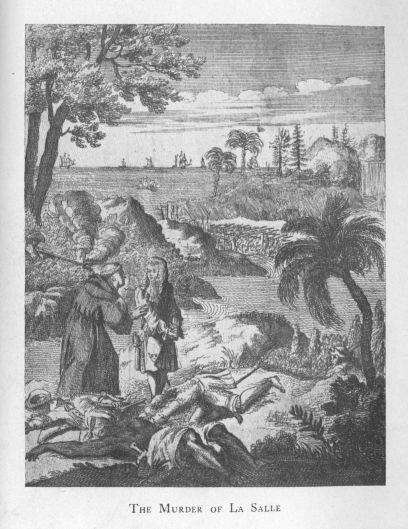

THE MURDER OF LA SALLE

From Hennepin's "A New Discovery of a Vast Country in America" |

278 |

|

LE MOYNE DE BIENVILLE

From the original painting in the possession of J. A. Allen, Esq., Kingston, Ont. |

284 |

|

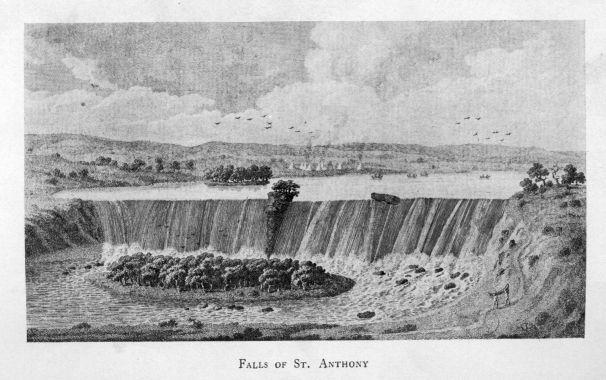

FALLS OF ST. ANTHONY

From Carver's "Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America" |

309 |

America probably peopled from Asia.—Unity of the American Race.—The Eskimo, possibly, an Exception.—Range of the Several Groups.

In an earlier volume, "Pioneer Spaniards in North America," the probable origin of the native races of America has been discussed. Let us restate briefly the general conclusions there set forth.

It is the universal opinion of scientific men that the people whom we call Indians did not originate in the Western World, but, in the far distant past, came upon this continent from another—from Europe, some say; from Asia, say others. In support of the latter opinion it is pointed out that Asia and America once were connected by a broad belt of land, now sunk {4} beneath the shallow Bering Sea. It is easy, then, to picture successive hordes of dusky wanderers pouring over from the old, old East upon the virgin soil of what was then emphatically a new world, since no human beings roamed its vast plains or traversed its stately forests.

Human wave followed upon wave, the new comers pushing the older ones on. Some wandered eastward and spread themselves in the region surrounding Hudson Bay. Others took a southeast course and were the ancestors of the Algonquins, Iroquois, and other families inhabiting the eastern territory of the United States. Still others pushed their way down the Pacific coast and peopled Mexico and Central America, while yet others, driven no doubt by the crowding of great numbers into the most desirable regions of the isthmus, passed on into South America and gradually overspread it.

Most likely these hordes of Asiatic savages wandered into America during hundreds of years and no doubt there was great diversity among them, some being far more advanced in the arts of life than others. But the essential thing to notice is that they were all of one blood. Thus their descendants, however different they may {5} have become in language and customs, constitute one stock, which we call the American Race. The peoples who reared the great earth-mounds of the Middle West, those who carved the curious sculptures of Central America, those who built the cave-dwellings of Arizona, those who piled stone upon stone in the quaint pueblos of New Mexico, those who drove Ponce de Leon away from the shores of Florida, and those who greeted the Pilgrims with, "Welcome, Englishmen!"—all these, beyond a doubt, were of one widely varying race.

To this oneness of all native Americans there is, perhaps, a single exception. Some writers look upon the Eskimo as a remnant of an ancient European race, known as the "Cave-men" because their remains are found in caves in Western Europe, always associated with the bones of arctic animals, such as the reindeer, the arctic fox, and the musk-sheep. From this fact it seems that these primitive men found their only congenial habitation amid ice and snow. Now, the Eskimo are distinctly an arctic race, and in other particulars they are amazingly like these men of the caves who dwelt in Western Europe when it had a climate like that of Greenland. The lamented {6} Dr. John Fiske puts the case thus strongly: "The stone arrow-heads, the sewing-needles, the necklaces and amulets of cut teeth, and the daggers made from antler, used by the Eskimos, resemble so minutely the implements of the Cave-men, that if recent Eskimo remains were to be put into the Pleistocene caves of France and England, they would be indistinguishable in appearance from the remains of the Cave-men which are now found there."

Further, these ancient men had an astonishing talent for delineating animals and hunting scenes. In the caves of France have been found carvings on bone and ivory, probably many tens of thousands of years old, which represent in the most life-like manner mammoths, cave-bears, and other animals now extinct. Strangely enough, of all existing savage peoples the Eskimo alone possess the same faculty. These circumstances make it probable that they are a remnant of the otherwise extinct Cave-men. If this is so, their ancestors probably passed over to this continent by a land-connection then existing between Northern Europe and Northern America, of which Greenland is a survival.

From the Eskimo southward to Cape Horn {7} we find various branches of the one American race. First comes the Athapascan stock, whose range extends from Hudson Bay westward through British America to the Rocky Mountains. One branch of this family left the dreary regions of almost perpetual ice and snow, wandered far down toward the south, and became known as the roaming and fierce Apaches, Navajos, and Lipans of the burning southwestern plains.

Immediately south of the Athapascans was the most extensive of all the families, the Algonquin. Their territory stretched without interruption westward from Cape Race, in Newfoundland, to the Rocky Mountains, on both banks of the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes. It extended southward along the Atlantic seaboard as far, perhaps, as the Savannah River. This family embraced some of the most famous tribes, such as the Abnakis, Micmacs, Passamaquoddies, Pequots, Narragansetts, and others in New England; the Mohegans, on the Hudson; the Lenape, on the Delaware; the Nanticokes, in Maryland; the Powhatans, in Virginia; the Miamis, Sacs and Foxes, Kickapoos and Chippeways, in the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys; and the Shawnees, on the Tennessee.

{8} This great family is the one that came most in contact and conflict with our forefathers. The Indians who figure most frequently on the bloody pages of our early story were Algonquins. This tribe has produced intrepid warriors and sagacious leaders.

Its various branches represent a very wide range of culture. Captain John Smith and Champlain, coasting the shores of New England, found them closely settled by native tribes living in fixed habitations and cultivating regular crops of corn, beans, and pumpkins. On the other hand, the Algonquins along the St. Lawrence, as well as some of the western tribes, were shiftless and roving, growing no crops and having no settled abodes, but depending on fish, game, and berries for subsistence, famished at one time, at another gorged. Probably the highest representatives of this extensive family were the Shawnees, at its southernmost limit.

Like an island in the midst of the vast Algonquin territory was the region occupied by the Huron-Iroquois family. In thrift, intelligence, skill in fortification, and daring in war, this stock stands preëminent among all native Americans. It included the Eries and Hurons, in Canada; {9} the Susquehannocks, on the Susquehanna; and the Conestogas, also in Pennsylvania. But by far the most important branch was the renowned confederacy called the Five Nations. This included the Senecas, Onondagas, Cayugas, Oneidas, and Mohawks. These five tribes occupied territory in a strip extending through the lake region of New York. At a later date a kindred people, the Tuscaroras, who had drifted down into Carolina, returned northward and rejoined the league, which thereafter was known as the Six Nations. This confederacy was by far the most formidable aggregation of Indians within the territory of the present United States. It waged merciless war upon other native peoples and had become so dreaded, says Dr. Fiske, that at the cry "A Mohawk!" the Indians of New England fled like sheep. It was especially hostile to some alien branches of its own kindred, the Hurons and Eries in particular.

South of the Algonquins was the Maskoki group of Indians, of a decidedly high class, comprising the Creeks, or Muskhogees, the Choctaws, the Chickasaws, and, later, the Seminoles. They occupied the area of the Gulf States, from the Atlantic to the Mississippi River. The {10} building of the Ohio earthworks is by many students attributed to the ancestors of these southern tribes, and it was they who heroically fought the Spanish invaders.

The powerful Dakota family, also called Sioux, ranged over territory extending from Lake Michigan to the Rocky Mountains and covering the most of the valley of the Missouri.

The Pawnee group occupied the Platte valley, in Nebraska, and the territory extending thence southward; and the Shoshonee group had for its best representatives the renowned Comanches, the matchless horsemen of the plains.

On the Pacific coast were several tribes, but none of any special importance. In the Columbia and Sacramento valleys were the lowest specimens of the Indian race, the only ones who may be legitimately classed as savages. All the others are more properly known as barbarians.

In New Mexico and Arizona is a group of remarkable interest, the Pueblo Indians, who inhabit large buildings (pueblos) of stone or sun-dried brick. In this particular they stand in a class distinct from all other native tribes in the United States. They comprise the Zuñis, Moquis, Acomans, and others, having different languages, {11} but standing on the same plane of culture. In many respects they have advanced far beyond any other stock. They have specially cultivated the arts of peace. Their great stone or adobe dwellings, in which hundreds of persons live, reared with almost incredible toil on the top of nearly inaccessible rocks or on the ledges of deep gorges, were constructed to serve at the same time as dwelling-places and as strongholds against the attacks of the roaming and murdering Apaches. These people till the thirsty soil of their arid region by irrigation with water conducted for miles. They have developed many industries to a remarkable degree, and their pottery shows both skill and taste.

These high-class barbarians are especially interesting because they have undergone little change since the Spaniards, under Coronado, first became acquainted with them, 364 years ago. They still live in the same way and observe the same strange ceremonies, of which the famous "Snake-dance" is the best known. They are, also, on a level of culture not much below that of the ancient Mexicans; so that from the study of them we may get a very good idea of the people whom Cortes found and conquered.

Mistakes of the Earliest European Visitors as to Indian Society and Government.—How Indian Social Life originated.—The Family Tie the Central Principle.—Gradual Development of a Family into a Tribe.—The Totem.

The first white visitors to America found men exercising some kind of authority, and they called them kings, after the fashion of European government. The Spaniards even called the head-chief of the Mexicans the "Emperor Montezuma." There was not a king, still less an emperor, in the whole of North America. Had these first Europeans understood that they were face to face with men of the Stone Age, that is, with men who had not progressed further than our own forefathers had advanced thousands of years ago, in that dim past when they used weapons and implements of stone, and when they had not as yet anything like written language, they would have been saved many blunders. They would not have called native chiefs by such high-sounding titles as "King {16} Powhatan" and "King Philip." They would not have styled the simple Indian girl, Pocahontas, a princess; and King James, of England, would not have made the ludicrous mistake of being angry with Rolfe for marrying her, because he feared that when her father died, she would be entitled to "the throne," and Rolfe would claim to be King of Virginia!

The study of Indian life has this peculiar interest, that it gives us an insight into the thinking and acting of our own forefathers long before the dawn of history, when they worshiped gods very much like those of the Indians.

All the world over, the most widely separated peoples in similar stages of development exhibit remarkably similar ideas and customs, as if one had borrowed from the other. There is often a curious resemblance between the myths of some race in Central Africa and those of some heathen tribe in Northern Europe. The human mind, under like conditions, works in the same way and produces like results. Thus, in studying pictures of Indian life as it existed at the Discovery, we have before us a sort of object-lesson in the condition of our own remote ancestors.

Now, the first European visitors made serious {17} errors in describing Indian life. They applied European standards of judgment to things Indian. A tadpole does not look in the least like a frog. An uninformed person who should find one in a pool, and, a few weeks later, should find a frog there, would never imagine that the tadpole had changed into the frog. Now, Indian society was in what we may call the tadpole stage. It was quite unlike European society, and yet it contained exactly the same elements as those out of which European society gradually unfolded itself long ago.

Indian society grew up in the most natural way out of the crude beginnings of all society. Let us consider this point for a moment. Suppose human beings of the lowest grade to be living together in a herd, only a little better than beasts, what influence would first begin to elevate them? Undoubtedly, parental affection. Indeed, mother-love is the foundation-stone of all our civilization. On that steadfast rock the rude beginnings of all social life are built. Young animals attain their growth and the ability to provide for themselves very early. The parents' watchful care does not need to be long exercised. The offspring, so soon as it is weaned, is quickly {18} forgotten. Not so the young human being. Its brain requires a long time for its slow maturing. Thus, for years, without its parents' care it would perish. The mother's love is strengthened by the constant attention which she must so long give to her child, and this is shared, in a degree, by the father. At the same time, their common interest in the same object draws them closer together. Before the first-born is able to find its own food and shelter other children come, and so the process is continually extended. Thus arises the family, the corner-stone of all life that is above that of brutes.

But the little household, living in a cave and fighting hand to hand with wild beasts and equally wild men, has a hard struggle to maintain itself. In time, however, through the marriage of the daughters—for in savage life the young men usually roam off and take wives elsewhere, while the young women stay at home—instead of the original single family, we have the grown daughters, with their husbands, living still with their parents and rearing children, thus forming a group of families, closely united by kinship. In the next generation, by the same process continued, we have a dozen, perhaps twenty, families, {19} all closely related, and living, it may be, under one shelter, the men hunting and providing food for the whole group, and the women working together and preparing the food in common.

Moreover, they all trace their relationship through their mothers, because the women are the home-staying element. In our group of families, for instance, all the women are descendants of the original single woman with whom we began; but the husbands have come from elsewhere. This is no doubt the reason why among savages it seems the universal practice to trace kinship through the mother. Again, in such a little community as we have supposed, the women, being all united by close ties of blood, are the ruling element. The men may beat their wives, but, after all, the women, if they join together against any one man, can put him out and remain in possession.

These points it is important to bear in mind, because they explain what would otherwise appear very singular features of Indian life. For instance, we understand now why a son does not inherit anything, not so much as a tobacco-pipe, at his father's death. He is counted as the mother's child. For the same reason, if the {20} mother has had more than one husband, and children by each marriage, these are all counted as full brothers and sisters, because they have the same mother.

Such a group of families as has been supposed is called a clan, or in Roman history a gens. It may be small, or it may be very numerous. The essential feature is that it is a body of people united by the tie of common blood. It may have existed for hundreds of years and have grown to thousands of persons. Some of the clans of the Scotch Highlands were quite large, and it would often have been a hopeless puzzle to trace a relationship running back through many generations. Still, every Cameron knew that he was related to all the other Camerons, every Campbell to all the other Campbells, and he recognized a clear duty of standing by every clansman as a brother in peace and in war. We see thus that the clan organization grows naturally out of the drawing together of men to strengthen themselves in the fierce struggle of savage life. The clan is simply an extension of the family. The family idea still runs through it, and kinship is the bond that holds together all the members.

{21}Now, this was just the stage of social progress that the Indians had reached at the Discovery. Their society was organized on the basis of the clan, and it bore all the marks of its origin.

Indians, however, have not any family names. Something, therefore, was needed to supply the lack of a common designation, so that the members of a clan might know each other as such, however widely they might be scattered. This lack was supplied by the clan-symbol, called a totem. This was always an animal of some kind, and an image of it was often rudely painted over a lodge-entrance or tattooed on the clansman's body. All who belonged to the clan of the Wolf, or the Bear, or the Tortoise, or any other, were supposed to be descended from a common ancestress; and this kinship was the tie that held them together in a certain alliance, though living far apart. It mattered not that the original clan had been split up and its fragments scattered among several different tribes. The bond of clanship still held. If, for example, a Cayuga warrior of the Wolf clan met a Seneca warrior of the same clan, their totem was the same, and they at once acknowledged each other as brothers.

{22}Perhaps we might illustrate this peculiar relation by our system of college fraternities. Suppose that a Phi-Beta-Kappa man of Cornell meets a Phi-Beta-Kappa man of Yale. Immediately they recognize a certain brotherhood. Only the tie of clanship is vastly stronger, because it rests not on an agreement, but on a real blood relationship.

According to Indian ideas, a man and a woman of the same clan were too near kindred to marry. Therefore a man must always seek a wife in some other clan than his own; and thus each family contained members of two clans.

The clan was not confined to one neighborhood. As it grew, sections of it drifted away and took up their abode in different localities. Thus, when the original single Iroquois stock became split into five distinct tribes, each contained portions of eight clans in common. Sometimes it happened that, when a clan divided, a section chose to take a new totem. Thus arose a fresh centre of grouping. But the new clan was closely united to the old by the sense of kinship and by constant intermarriages. This process of splitting and forming new clans had gone on for a long time among the Indians—for how {23} many hundreds of years, we have no means of knowing. In this way there had arisen groups of clans, closely united by kinship. Such a group we call a phratry.

A number of these groups living in the same region and speaking a common dialect constituted a larger union which we sometimes call a nation, more commonly a tribe.

This relation may be illustrated by the familiar device of a family-tree, thus:

{24} Here we see eleven clans, all descended from a common stock and speaking a common dialect, composing the Mohegan Tribe. Some of the smaller tribes, however, had not more than three clans.

The point that we need to get clear in our minds is that an Indian tribe was simply a huge family, extended until it embraced hundreds or even thousands of souls. In many cases organization never got beyond the tribe. Not a few tribes stood alone and isolated. But among some of the most advanced peoples, such as the Iroquois, the Creeks, and the Choctaws, related tribes drew together and formed a confederacy or league, for mutual help. The most famous league in Northern America was that of the Iroquois. We shall describe it in the next chapter. It deserves careful attention, both because of its deep historical interest, and because it furnishes the best-known example of Indian organization.

History of the League.—Natural Growth of Indian Government.—How Authority was exercised, how divided.—Popular Assemblies.—Public Speaking.—Community Life.

Originally the Iroquois people was one, but as the parent stock grew large, it broke up into separate groups.

Dissensions arose among these, and they made war upon one another. Then, according to their legend, Hayawentha, or Hiawatha, whispered into the ear of Daganoweda, an Onondaga sachem, that the cure for their ills lay in union. This wise counsel was followed. The five tribes known to Englishmen as the Mohawks, the Oneidas, the Onondagas, the Cayugas, and the Senecas—their Indian names are different and much longer—buried the hatchet and formed a confederacy which grew to be, after the Aztec League in Mexico, the most powerful Indian organization in North America. It was then known as "The Five Nations."

{28}About 1718, one of the original branches, the Tuscaroras, which had wandered away as far as North Carolina, pushed by white men hungry for their land, broke up their settlements, took up the line of march, returned northward, and rejoined the other branches of the parent stem. From this time forth the League is known in history as "The Six Nations," the constant foe of the French and ally of the English. The Indian name for it was "The Long House," so called because the wide strip of territory occupied by it was in the shape of one of those oblong structures in which the people dwelt.

When the five tribes laid aside their strife, the fragments of the common clans in each re-united in heartiest brotherhood and formed an eightfold bond of union. On the other hand, the Iroquois waged fierce and relentless war upon the Hurons and Eries, because, though they belonged to the same stock, they refused to join the League. This denial of the sacred tie of blood was regarded by the Iroquois as rank treason, and they punished it with relentless ferocity, harrying and hounding the offending tribes to destruction.

Indian government, like Indian society, was just such as had grown up naturally out of the {29} conditions. It was not at all like government among civilized peoples. In the first place, there were no written laws to be administered. The place of these was taken by public opinion and tradition, that is, by the ideas handed down from one generation to another and constantly discussed around the camp-fire and the council-fire. Every decent Indian was singularly obedient to this unwritten code. He wanted always to do what he was told his fathers had been accustomed to do, and what was expected of him. Thus there was a certain general standard of conduct.

Again, the men who ruled, though they were formally elected to office, had not any authority such as is possessed by our judges and magistrates, who can say to a man, "Do thus," and compel him to obey or take the consequences. The influence of Indian rulers was more like that of leading men in a civilized community: it was chiefly personal and persuasive, and it was exerted in various indirect ways. If, for example, it became a question how to deal with a man who had done something violently opposed to Indian usage or to the interest of the tribe, there was not anything like an open trial, but the chiefs held a secret council and discussed the case. If they {30} decided favorably to the man, that was an end of the matter. On the other hand, if they agreed that he ought to die, there was not any formal sentence and public execution. The chiefs simply charged some young warrior with the task of putting the offender out of the way. The chosen executioner watched his opportunity, fell upon his victim unawares, perhaps as he passed through the dark porch of a lodge, and brained him with his tomahawk. The victim's family or clan made no demand for reparation, as they would have done if he had been murdered in a private feud, because public opinion approved the deed, and the whole power of the tribe would have been exerted to sustain the judgment of the chiefs.

According to our ideas, which demand a fair and open trial for every accused person, this was most abhorrent despotism. Yet it had one very important safeguard: it was not like the arbitrary will of a single tyrant doing things on the impulse of the moment. Indians are eminently deliberative. They are much given to discussing things and endlessly powwowing about them. They take no important step without talking it over for days. Thus, in such a case as has been supposed, there was general concurrence in the {31} judgment of the chiefs, because they were understood to have canvassed the matter carefully, and their decision was practically that of the tribe.

This singular sort of authority was vested in two kinds of men; sachems, who were concerned with the administration of the tribal affairs at all times, and war-chiefs, whose duty was limited to leadership in the field. The sachems, therefore, constituted the real, permanent government. Of these there were ten chosen in each of the five tribes. Their council was the governing body of the tribe. In these councils all were nominally equals. But, naturally, men of strong personality exercised peculiar power. The fifty sachems of the five tribes composed the Grand Council which was the governing body of the League. In its deliberations each tribe had equal representation through its ten sachems. But the Onondaga nation, being situated in the middle of the five, and the grand council-fire being held in its chief town, exercised a preponderating influence in these meetings.

Besides the Grand Council and the tribal council, there were councils of the minor chiefs, and councils of the younger warriors, and even councils of the women, for a large part of an Indian's {32} time was taken up with powwowing. Besides these formal deliberative bodies, there were gatherings that were a sort of rude mass-meeting. If a question of deep interest was before the League for discussion, warriors flocked by hundreds from all sides to the great council-fire in the Onondaga nation. The town swarmed with visitors. Every lodge was crowded to its utmost capacity; temporary habitations rose, and fresh camp-fires blazed on every side, and even the unbounded Indian hospitality was strained to provide for the throng of guests. Thus, hour after hour, and day after day, the issue was debated in the presence of hundreds, some squatting, some lying at full length, all absolutely silent except when expressing approval by grunts.

The discussion was conducted in a manner that would seem to us exceedingly tedious. Each speaker, before advancing his views, carefully rehearsed all the points made by his predecessors. This method had the advantage of making even the dullest mind familiar with the various aspects of the subject, and it resulted in a so thorough sifting of it that when a conclusion was reached, it was felt to be the general sense of the meeting.

From this account it will be evident that public {33} speaking played a large part in Indian life. This fact will help us to account for the remarkable degree of eloquence sometimes displayed. If we should think of the Indian as an untutored savage, bursting at times into impassioned oratory, under the influence of powerful emotions, we should miss the truth very widely. The fact is, there was a class of professional speakers, who had trained themselves by carefully listening to the ablest debaters among their people, and had stored their memories with a large number of stock phrases and of images taken from nature. These metaphors, which give to Indian oratory its peculiar character, were not, therefore, spontaneous productions of the imagination, but formed a common stock used by all speakers as freely as orators in civilized society are wont to quote great authors and poets. Among a people who devoted so much time to public discussion, a forcible speaker wielded great influence. One of the sources of the power over the natives of La Salle, the great French explorer, lay in the fact that he had thoroughly mastered their method of oratory and could harangue an audience in their own tongue like one of their best speakers.

The subject of the chiefship is a very {34} interesting one. As has already been explained, a son did not inherit anything from his father. Therefore nobody was entitled to be a chief because his father had been one. Chiefs were elected wholly on the ground of personal qualities. Individual merit was the only thing that counted. Moreover, the chiefs were not the only men who could originate a movement. Any warrior might put on his war-paint and feathers and sing his war-song. As many as were willing might join him, and the party file away on the war-path without a single chief. If such a voluntary leader showed prowess and skill, he was sure to be some day elected a chief.

It is very interesting to reflect that just this free state of things existed thousands of years ago among our own ancestors in Europe. At that time there were no kings claiming a "divine right" to govern their fellow men. The chiefs were those whose courage, strength, and skill in war made them to be chosen "rulers of men," to use old Homer's phrase. If their sons did not possess these qualities, they remained among the common herd. But there came a time when, here and there, some mighty warrior gained so much wealth in cattle and in slaves taken in battle, that {35} he was able to bribe some of his people and to frighten others into consenting that his son should be chief after him. If the son was strong enough to hold the office through his own life and to hand it to his son, the idea soon became fixed that the chiefship belonged in that particular family.

This was the beginning of kingship. But our aborigines had not developed any such absurd notion as that there are particular families to which God has given the privilege of lording it over their fellow men. They were still in the free stage of choosing their chiefs from among the men who served them best. We may say with confidence that there was not an emperor, or a king, or anything more than an elective chief in the whole of North America.

Not only had nobody the title and office of a king among the Indians; nobody had anything like kingly authority. Rulership was not vested in any one man, but in the council of chiefs. This feature, of course, was very democratic. And there was another that went much further in the same direction: almost all property was held in common. For instance, the land of a tribe was not divided among individual owners, but {36} belonged to the whole tribe, and no part of it could be bartered away without the entire tribe's consent. A piece might be temporarily assigned to a family to cultivate, but the ownership of it remained in the whole tribe. This circumstance tended more than anything else to prevent the possibility of any man's raising himself to kingly power. Such usurpations commonly rest upon large accumulations of private property of some kind. But among a people not one of whom owned a single rood of land, who had no flocks and herds, nor any domestic animals whatever, except dogs, and among whom the son inherited nothing from his father, there was no chance for anybody to gain wealth that would raise him above his fellows.

Thus we see that an Indian tribe was in many respects an ideal republic. With its free discussion of all matters of general interest; with authority vested in a body of the fittest men; with the only valuable possession, land, held by the whole tribe as one great family; in the entire absence of personal wealth; and with the unlimited opportunity for any man possessing the qualities that Indians admire to raise himself to influence, there really was a condition of affairs very like {37} that which philosophers have imagined as the best conceivable state of human society for preserving individual freedom.

Even the very houses of the Indians were adapted to community-life. They were built, not to shelter families, but considerable groups of families. One very advanced tribe, the Mandans, on the upper Missouri, built circular houses. But the most usual form, as among the Iroquois, was a structure very long in proportion to its width. It was made of stout posts set upright in the earth, supporting a roof-frame of light poles slanting upward and fastened together at their crossing. Both walls and roof were covered with wide strips of bark held in place by slender poles secured by withes. Heavy stones also were laid on the roof to keep the bark in place. At the top of the roof a space of about a foot was left open for the entrance of light and the escape of smoke, there being neither windows nor chimneys. At either end was a door, covered commonly with a skin fastened at the top and loose at the bottom. In the winter-season these entrances were screened by a porch.

In one of these long houses a number of families lived together in a way that carried out in {38} all particulars the idea of one great household. Throughout the length of the building, on both sides, were partitions dividing off spaces a few feet square, all open toward the middle like wide stalls in a stable. Each of these spaces was occupied by one family and contained bunks in which they slept. In the aisles, between every four of these spaces, was a fire which served the four families. The number of fires in a lodge indicated, quite nearly, the number of persons dwelling in it. To say, for instance, a lodge of five fires, meant one that housed twenty families.

This great household lived together according to the community-idea. The belongings of individuals, even of individual families, were very few. The produce of their fields of corn, beans, pumpkins, and sunflowers was held as common property; and the one regular meal of the day was a common meal, cooked by the squaws and served to each person from the kettle. The food remaining over was set aside, and each person might help himself to it as he had need. If a stranger came in, the squaws gave him to eat out of the common stock. In fact, Indian hospitality grew out of this way of living in common. A single family would frequently have been "eaten out of {39} house and home," if it had needed to provide out of its own resources for all the guests that might suddenly come upon it.

We are apt to think of the Indian as a silent, reserved, solitary being. Nothing could be further from the truth. However they may appear in the presence of white men, among themselves Indians are a very jolly set. Their life in such a common dwelling as has been described was intensely social in its character. Of course, privacy was out of the question. Very little took place that was not known to all the inmates. And we can well imagine that when all were at home, an Indian lodge was anything else than a house of silence. Of a winter evening, for instance, with the fires blazing brightly, there was a vast deal of boisterous hilarity, in which the deep guttural tones of the men and the shrill voices of the squaws were intermingled. Around the fires there were endless gossiping, story-telling, and jesting. Jokes, by no means delicate and decidedly personal, provoked uproarious laughter, in which the victim commonly joined.

A village, composed of a cluster of such abodes standing without any order and enclosed by a stockade, was, at times, the scene of almost {40} endless merry-making. Now it was a big feast; now a game of chance played by two large parties matched against each other, while the lodge was crowded almost to suffocation by eager spectators; now a dance, of the peculiar Indian kind; now some solemn ceremony to propitiate the spirits who were supposed to rule the weather, the crops, the hunting, and all the interests of barbarian life.

At all times there was endless visiting from lodge to lodge. Hospitality was universal. Let a visitor come in, and it would have been the height of rudeness not to set food before him. To refuse it would have been equally an offence against good manners. Only an Indian stomach was equal to the constant round of eating. White men often found themselves seriously embarrassed between their desire not to offend their hosts and their own repugnance to viands which could not tempt a civilized man who was not famished.

It seems strange to think of the women as both the drudges and the rulers of the lodge. Yet such they were. This fact arose from the circumstance already mentioned, that descent was counted, not through the fathers, but through the mothers. The home and the children were {41} the wife's, not the husband's. There she lived, surrounded by her female relatives, whereas he had come from another clan. If he proved lazy or incompetent to do his full share of providing, let the women unite against him, and out he must go, while the wife remained.

The community idea, which we have seen to be the key to Indian social life, showed itself in universal helpfulness. Ferocious and pitiless as these people were toward their enemies, the women even more ingeniously cruel than the men, nothing could exceed the cheerful spirit with which, in their own rough way, they bore one another's burdens. It filled the French missionaries with admiration, and they frequently tell us how, if a lodge was accidentally burned, the whole village turned out to help rebuild it; or how, if children were left orphans, they were quickly adopted and provided for. It is equally a mistake to glorify the Indian as a hero and to deny him the rude virtues which he really possessed.

The Difference between Spanish and French Methods.—What caused the Difference.—How it resulted.

A singular and picturesque story is that of New France. In romantic interest it has no rival in North America, save that of Mexico. Frenchmen opened up the great Northwest; and for a long time France was the dominant power in the North, as Spain was in the South. When the French tongue was heard in wigwams in far western forests; when French goods were exchanged for furs at the head of Lake Superior and around Hudson Bay; when French priests had a strong post as far to the West as Sault Ste. Marie, and carried their missionary journeyings still further, who could have foreseen the day when the flag of republican France would fly over only two rocky islets off the coast of Newfoundland, and to her great rival, Spain, of all {46} her vast possessions would remain not a single rood of land on the mainland of the world to which she had led the white race?

At the period with which we are occupied these two great Catholic powers seemed in a fair way to divide North America between them. Their methods were as different as the material objects which they sought. The Spaniard wanted Gold, and he roamed over vast regions in quest of it, conquering, enslaving, and exploiting the natives as the means of achieving his ends. The Frenchman craved Furs, and for these he trafficked with the Indians. The one depended on conquest, the other on trade.

Now trade cannot exist without good-will. You may rob people at the point of the sword, but to have them come to you freely and exchange with you, you must have gained their confidence. Further, there was a deep-lying cause for this difference of method. Wretched beings may be worked in gangs, under a slave-driver, in fields and mines. This was the Spanish way. But hunting animals for their skins and trapping them for their furs is solitary work, done by lone men in the wilderness, and, above all, by men who are free to come and go. You {47} cannot make a slave of the hunter who roams the forests, traps the brooks, and paddles the lakes and streams. His occupation keeps him a wild, free man. Whatever advantage is taken of him must be gained by winning his confidence.

Thus the object of the Frenchman's pursuit rendered necessary a constantly friendly attitude toward the Indians. If he displeased them, they would cease to bring their furs. If he did not give enough of his goods in exchange, they would take a longer journey and deal with the Dutch at Albany or with the English at their outlying settlements. In short, the Spaniard had no rival and was in a position allowing him to be as brutal as he pleased. The Frenchman was simply in the situation of a shopkeeper who has no control over his customers, and if he does not retain their good-will, must see them deal at the other place across the street.

There is no doubt that this difference of conditions made an enormous difference between the Spanish and the French attitude toward the Indians. The Spaniards were naturally inclined to be haughty and cruel toward inferior races, while the French generally showed themselves friendly and mingled freely with the natives in {48} new regions. But the circumstance to which attention has here been called tended to exaggerate the natural disposition of each. Absolute power made the Spaniard a cruel master: the lack of it drove the Frenchman to gain his ends by cunning and cajolery.

The consequence was, that while the Spaniard was dreaded and shunned, and whole populations were wiped out by his merciless rule, the Frenchman was loved by the Indians. They turned gladly to him from the cold Englishman, who held himself always in the attitude of a superior being; they made alliances with him and scalped his enemies, white or red, with devilish glee; they hung about every French post, warmed themselves by the Frenchman's fire, ate his food, and patted their stomachs with delight; and they swarmed by thousands to Quebec, bringing their peltries for trade, received gewgaws and tinsel decorations from the Governor, and swore eternal allegiance to his master, the Sun of the World, at Versailles.

In a former volume, "Pioneer Spaniards in North America," we have followed the steps of Spain's dauntless leaders in the Western World. We have seen Balboa, Ponce, Cortes, Soto, {49} Coronado, making their way by the bloody hand, slaying, plundering, and burning, and we have heard the shrieks of victims torn to pieces by savage dogs.

In the present volume quite other methods will engage our attention. We shall accompany the shrewd pioneers of France, as they make their joyous entry into Indian villages, eat boiled dog with pretended relish, sit around the council-fire, smoke the Indian's pipe, and end by dancing the war-dance as furiously as the red men.

Jacques Cartier enters the St. Lawrence.—He imagines that he has found a Sea-route to the Indies.—The Importance of such a Route.—His Exploration of the St. Lawrence.—A Bitter Winter.—Cartier's Treachery and its Punishment.—Roberval's Disastrous Expedition.

How early the first Frenchmen visited America it is hard to say. It has been claimed, on somewhat doubtful evidence, that the Basques, that ancient people inhabiting the Pyrenees and the shores of the Bay of Biscay, fished on the coast of Newfoundland before John Cabot saw it and received credit as the discoverer of this continent. So much, at any rate, is certain, that within a very few years after Cabot's voyage a considerable fleet of French, Spanish, and Portuguese vessels was engaged in the Newfoundland fishery. Later the English took part in it. The French soon gained the lead in this industry {54} and thus became the predominant power on the northern shores of America, just as the Spaniards were on the southern. The formal claim of France to the territory which she afterward called New France was based on the explorations of her adventurous voyagers.

Jacques Cartier was a daring mariner, belonging to that bold Breton race whose fishermen had for many years frequented the Newfoundland Banks for codfish. In 1534 he sailed to push his exploration farther than had as yet been attempted. His inspiration was the old dream of all the early navigators, the hope of finding a highway to China. Needless to say, he did not find it, but he found something well worth the finding—Canada.

Sailing through the Straits of Belle Isle, he saw an inland sea opening before him. Passing Anticosti Island, he landed on the shore of a fine bay. It was the month of July, and it chanced to be an oppressive day. "The country is hotter than the country of Spain," he wrote in his journal. Therefore he gave the bay its name, the Bay of Chaleur (heat). The beauty and fertility of the country, the abundance of berries, and "the many goodly meadows, full of {55} grass, and lakes wherein great pleanty of salmons be," made a great impression on him.

On the shore were more than three hundred men, women, and children. "These showed themselves very friendly," he says, "and in such wise were we assured one of another, that we very familiarly began to traffic for whatever they had, till they had nothing but their naked bodies, for they gave us all whatsoever they had." These Indians belonged undoubtedly to some branch of the Algonquin family occupying all this region.

Cartier did not scruple to take advantage of their simplicity. At Gaspé he set up a cross with the royal arms, the fleur-de-lys, carved on it, and a legend meaning, "Long live the King of France!" He meant this as a symbol of taking possession of the country for his master. Yet, when the Indian chief asked him what this meant, he answered that it was only a landmark for vessels that might come that way. Then he lured some of the natives on board and succeeded in securing two young men to be taken to France. This villainy accomplished, he sailed for home in great glee, not doubting that the wide estuary whose mouth he had entered was the opening of the long-sought passage to Cathay. In France {56} his report excited wild enthusiasm. The way to the Indies was open! France had found and France would control it!

Natural enough was this joyful feeling. The only water-route to the East then in use was that around the Cape of Good Hope, and it belonged, according to the absurd grant of Pope Alexander the Sixth, to Portugal alone. Spain had opened another around the Horn, but kept the fact carefully concealed. In short, the selfish policy of Spain and Portugal was to shut all other nations out of trading with the regions which they claimed as theirs; and these tyrants of the southern seas were not slow in enforcing their claims. Spain, too, had ample means at her disposal. She was the mightiest power in the world, and her dominion on the ocean there was none to dispute. At that time Drake and Hawkins and those other great English seamen who broke her sea-power had not appeared. This condition of affairs compelled the northern nations, the English, French, and Dutch, to seek a route through high latitudes to the fabled wealth of the Indies. It led to those innumerable attempts to find a northeast or a northwest passage of which we have read elsewhere. (See, in "The World's Discoverers," {57} accounts of Frobisher, Davis, Barentz, and Hudson, and of Nordenskjold, their triumphant successor.)

Now, Francis the First, the French monarch, a jealous rival of the Spanish sovereign, was determined to get a share of the New World. He had already, in 1524, sent out Verrazano to seek a passage to the East (See a sketch of this very interesting voyage in "The World's Discoverers"), and now he was eager to back Cartier with men and money.

Accordingly, the next year we find the explorer back at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, this time with three vessels and with a number of gentlemen who had embarked in the enterprise, believing that they were on their way to reap a splendid harvest in the Indies, like that of the Spanish cavaliers who sailed with the conquerors of Mexico and Peru. Entering, on St. Lawrence's day, the Gulf which he had discovered in the previous year, he named it the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The river emptying into it he called Hochelaga, from the Indian name of the adjacent country. Then, guided by the two young natives whom he had kidnapped the year before, whose home, though they had been seized near its mouth, was high up the river, he sailed up the {58} wide stream, convinced that he was approaching China.

In due time Stadaconé was reached, near the site of Quebec, and Cartier visited the chief, Donnaconna, in his village. The two young Indians who acted as guides and interpreters had been filling the ears of their countrymen with marvelous tales of France. Especially, they had "made great brags," Cartier says, about his cannon; and Donnaconna begged him to fire some of them. Cartier, quite willing to give the savages a sense of his wonderful resources, ordered twelve guns fired in quick succession. At the roar of the cannon, he says, "they were greatly astonished and amazed; for they thought that Heaven had fallen upon them, and put themselves to flight, howling and crying and shrieking as if hell had broken loose."

Leaving his two larger vessels safely anchored within the mouth of the St. Charles River, Cartier set out with the smallest and two open boats, to ascend the St. Lawrence. At Hochelaga he found a great throng of Indians on the shore, wild with delight, dancing and singing. They loaded the strangers with gifts of fish and maize. At night the dark woods, far and near, were {59} illumined with the blaze of great fires around which the savages capered with joy.

The next day Cartier and his party were conducted to the great Indian town. Passing through cornfields laden with ripening grain, they came to a high circular palisade consisting of three rows of tree-trunks, the outer and the inner inclining toward each other and supported by an upright row between them. Along the top were "places to run along and ladders to get up, all full of stones for the defence of it." In short, it was a very complete fortification, of the kind that the Hurons and the Iroquois always built.

Passing through a narrow portal, the Frenchmen saw for the first rime a group of those large, oblong dwellings, each containing several families, with which later travelers became familiar in the Iroquois and the Huron countries. Arriving within the town, the visitors found themselves objects of curious interest to a great throng of women and children who crowded around the first Europeans they had ever beheld, with expressions of wonder and delight. These bearded men seemed to them to have come down from the skies, children of the Sun.

{60}Next, a great meeting was held. Then came a touching scene. An aged chief who was paralyzed was brought and placed at Cartier's feet, and the latter understood that he was asked to heal him. He laid his hands on the palsied limbs. Then came a great procession of the sick, the lame, and the blind, "for it seemed unto them," says Cartier, "that God was descended and come down from Heaven to heal them." We cannot but recall how Cortes and his Spaniards were held by the superstitious Aztecs to have come from another world, and how Cabeza de Vaca was believed to exercise the power of God to heal the sick. (See "Pioneer Spaniards in North America.") Cartier solemnly read a passage of the Scriptures, made the sign of the cross over the poor suppliants, and offered prayer. The throng of savages, without comprehending a word, listened in awe-struck silence.

After distributing gifts, the Frenchmen, with a blast of trumpets, marched out and were led to the top of a neighboring mountain. Seeing the magnificent expanse of forest extending to the horizon, with the broad, blue river cleaving its way through. Cartier thought it a domain worthy or a prince and called the eminence Mont Royal. {61} Thus originated the name of the future city of Montreal, built almost a century later.

By the time that he had returned to Stadaconé the autumn was well advanced, and his comrades had made preparations against the coming of winter by building a fort of palisades on or near the site where Quebec now stands.

Soon snow and ice shut in the company of Europeans, the first to winter in the northern part of this continent. A fearful experience it was. When the cold was at its worst, and the vessels moored in the St. Charles River were locked fast in ice and burled in snow-drifts, that dreadful scourge of early explorers, the scurvy, attacked the Frenchmen. Soon twenty-five had died, and of the living but three or four were in health. For fear that the Indians, if they learned of their wretched plight, might seize the opportunity of destroying them outright, Cartier did not allow any of them to approach the fort. One day, however, chancing to meet one of them who had himself been ill with the scurvy, but now was quite well, he was told of a sovereign remedy, a decoction of the leaves of a certain tree, probably the spruce. The experiment was tried with success, and the sick Frenchmen recovered.

{62}At last the dreary winter wore away, and Cartier prepared to return home. He had found neither gold nor a passage to India, but he would not go empty-handed. Donnaconna and nine of his warriors were lured into the fort as his guests, overwhelmed by sturdy sailors, and carried on board the vessels. Then, having raised over the scene of this cruel treachery the symbol of the Prince of Peace, he set sail for France.

In 1541 Cartier made another, and last, voyage to Canada. On reaching Stadaconé he was besieged by savages eagerly inquiring for the chiefs whom he had carried away. He replied that Donnaconna was dead, but the others had married noble ladies and were living in great state in France. The Indians showed by their coldness that they knew this story to be false. Every one of the poor exiles had died.

On account of the distrust of the natives, Carder did not stop at Stadaconé, but pursued his way up the river. While the bulk of his party made a clearing on the shore, built forts, and sowed turnip-seed, he went on and explored the rapids above Hochelaga, evidently still hoping to find a passage to India. Of course, he was disappointed. He returned to the place {63} where he had left his party and there spent a gloomy winter, destitute of supplies and shunned by the natives.

All that he had to show for his voyage was a quantity of some shining mineral and of quartz crystals, mistaken for gold and diamonds. The treachery of the second voyage made the third a failure.

Thus ended in disappointment and gloom the career of France's great pioneer, whose discoveries were the foundation of her claims in North America, and who first described the natives of that vast territory which she called New France.

Another intending settler of those days was the Sieur de Roberval. Undismayed by Cartier's ill-success, he sailed up the St. Lawrence and cast anchor before Cap Rouge, the place which Cartier had fortified and abandoned. Soon the party were housed in a great structure which contained accommodations for all under one roof, so that it was planned on the lines of a true colony, for it included women and children. But few have ever had a more miserable experience. By some strange lack of foresight, there was a very scant supply of food, and with the winter came famine. Disease inevitably followed, so that before spring {64} one-third of the colony had died. We may think that Nature was hard, but she was mild and gentle, in comparison with Roberval. He kept one man in irons for a trifling offence. Another he shot for a petty theft. To quarreling men and women he gave a taste of the whipping-post. It has even been said that he hanged six soldiers in one day.

Just what was the fate of this wretched little band has not been recorded. We only know that it did not survive long. With its failure closes the first chapter of the story of French activity on American soil. Fifty years had passed since Columbus had made his great discovery, and as yet no foothold had been gained by France anywhere, nor indeed by any European power on the Atlantic seaboard of the continent.

The Expedition of Captain Jean Ribaut.—Landing on the St. John's River.—Friendly Natives.—The "Seven Cities of Cibola" again!—The Coast of Georgia.—Port Royal reached and named.—A Fort built and a Garrison left.—Discontent and Return to France.

No doubt the severe winters of Canada determined Admiral Coligny, the leader of the Huguenots, or French Protestants, to plant the settlement which he designed as a haven of refuge from persecution, in the southern part of the New World.

Accordingly, on the first day of May, 1562, two little vessels under the command of Captain Jean Ribaut found themselves off the mouth of a great river which, because of the date, they called the River of May, now known as the St. John's.

{68}When they landed, it seemed to the sea-worn Frenchmen as if they had set foot in an enchanted world. Stalwart natives, whom Laudonnière, one of the officers, describes as "mighty and as well shapen and proportioned of body as any people in the world," greeted them hospitably.[1] Overhead was the luxuriant semi-tropical vegetation, giant oaks festooned with gray moss trailing to the ground and towering magnolias opening their great white, fragrant cups. No wonder they thought this newly discovered land the "fairest, fruitfullest, and pleasantest of all the world." One of the Indians wore around his neck a pearl "as great as an acorne at the least" and gladly exchanged it for a bauble. This set the explorers to inquiring for gold and gems, {69} and they soon gathered, as they imagined, from the Indians' signs that the "Seven Cities of Cibola" [2]—again the myth that had led Coronado and his Spaniards to bitter disappointment!—were distant only twenty days' journey. Of course, the natives had never heard of Cibola and did not mean anything of the kind. The explorers soon embarked and sailed northward, exploring the coast of Georgia and giving to the rivers or inlets the names of rivers of France, such as the Loire and the Gironde.

On May 27 they entered a wide and deep harbor, spacious enough, it seemed to them, "to hold the argosies of the world." A royal haven it seemed. Port Royal they named it, and Port Royal it is called to this day. They sailed up this noble estuary and entered Broad River. When they landed the frightened Indians fled. Good reason they had to dread the sight of white men, for this was the country of Chicora (South Carolina), the scene of one of those acts of brutal treachery of which the Spaniards, of European nations, were the most frequently all guilty.

Forty-two years before, Lucas Vasquez de {70} Ayllon, a high official of San Domingo, had visited this coast with two vessels. The simple and kindly natives lavished hospitality on the strangers. In return, the Spaniards invited them on board. Full of wondering curiosity, the Indians without suspicion explored every part of the vessels. When the holds were full of sight-seers, their hosts suddenly closed the hatches and sailed away with two ship-loads of wretched captives doomed to toil as slaves in the mines of San Domingo. But Ayllon's treachery was well punished. One of his vessels was lost, and on board the other the captives refused food and mostly died before the end of the voyage. On his revisiting the coast, six years later, nearly his entire following was massacred by the natives, who lured them to a feast, then fell upon them in the dead of night. Treachery for treachery!

The Frenchmen, however, won the confidence of the Indians with gifts of knives, beads, and looking-glasses, coaxed two on board the ships, and loaded them with presents, in the hope of reconciling them to going to France. But they moaned incessantly and finally fled.

These Europeans, however, had not done {71} anything to alarm the natives, and soon the latter were on easy terms with them. Therefore, when it was decided to leave a number of men to hold this beautiful country for the King, Ribaut felt sure of the Indians' friendly disposition. He detailed thirty men, under the command of Albert de Pierria, as the garrison of a fort which he armed with guns from the ship.

It would delight us to know the exact site of this earliest lodgment of Europeans on the Atlantic coast north of Mexico. All that can be said with certainty is that it was not many miles from the picturesque site of Beaufort.

Having executed his commission by finding a spot suitable for a colony, Ribaut sailed away, leaving the little band to hold the place until he should return with a party of colonists. Those whom he left had nothing to do but to roam the country in search of gold, haunted, as they were, by that dream which was fatal to so many of the early ventures in America. They did not find any, but they visited the villages of several chiefs and were always hospitably entertained. When supplies in the neighborhood ran low, they made a journey by boat through inland water-ways to two chiefs on the Savannah River, who furnished {72} them generously with corn and beans; and when their storehouse burned down, with the provisions which they had just received, they went again to the same generous friends, received a second supply, and were bidden to come back without hesitation, if they needed more. There seemed to be no limit to the good-will of the kindly natives.[3]

Their monotonous existence soon began to pall on the Frenchmen, eager for conquest and gold. They had only a few pearls, given them by the Indians. Of these the natives undoubtedly possessed a considerable quantity, but not baskets heaped with them, as the Spaniards said.

{73}Roaming the woods or paddling up the creeks, the Frenchmen encountered always the same rude fare, hominy, beans, and fish. Before them was always the same glassy river, shimmering in the fierce midsummer heat; around them the same silent pine forests.

The rough soldiers and sailors, accustomed to spend their leisure in taverns, found the dull routine of existence in Chicora insupportable. Besides, their commander irritated them by undue severity. The crisis came when he hanged a man with his own hands for a slight offence. The men rose in a body, murdered him, and chose Nicholas Barré to succeed him.

Shortly afterward they formed a desperate resolve: they would build a ship and sail home. Nothing could have seemed wilder. Not one of them had any experience of ship-building. But they went to work with a will. They had a forge, tools, and some iron. Soon the forest rang with the sound of the axe and with the crash of falling trees. They laid the keel and pushed the work with amazing energy and ingenuity, caulked the seams with long moss gathered from the neighboring trees and smeared the bottoms and sides with pitch from the pines. The {74} Indians showed them how to make a kind of cordage, and their shirts and bedding were sewn together into sails. At last their crazy little craft was afloat, undoubtedly the first vessel built on the Atlantic seaboard of America.

They laid in such stores as they could secure by bartering their goods, to the Indians, deserted their post, and sailed away from a land where they could have found an easy and comfortable living, if they had put into the task half the thought and labor which they exerted to escape from it.

Few voyages, even in the thrilling annals of exploration, have ever been so full of hardship and suffering as this mad one. Alternate calms and storms baffled, famine and thirst assailed the unfortunate crew. Some died outright; others went crazy with thirst, leaped overboard, and drank their fill once and forever. The wretched survivors drew lots, killed the man whom fortune designated, and satisfied their cravings with his flesh and blood. At last, as they were drifting helpless, with land in sight, an English vessel bore down on them, took them all on board, landed the feeblest, and carried the rest as prisoners to Queen Elizabeth.

[1] These people were of the Timucua tribe, one that has since become entirely extinct, and that was succeeded in the occupation of Florida by the warlike Seminoles, an off-shoot of the Creeks. They belonged to the Muskoki group, which Included some of the most advanced tribes on our continent. These Southern Indians had progressed further in the arts of life than the Algonquins and the Iroquois, and were distinguished from these by a milder disposition. Gentle and kind toward strangers, they were capable of great bravery when defending their homes or punishing treachery, as the Spanish invaders had already learned to their cost. They dwelt in permanent villages, raised abundant crops of corn, pumpkins, and other vegetables, and, amid forests full of game and rivers teeming with fish, lived in ease and plenty.

[2] See "Pioneer Spaniards in North America."

[3] These were Edistoes and Kiowas. The fierce Yemassees came into the country later. The kindness of the Southern Indians, when not provoked by wanton outrage, is strikingly illustrated in the letter of the famous navigator, Giovanni Verrazzano (See "The World's Discoverers"), who visited the Atlantic seaboard nearly about the same time as the kidnapper Ayllon. Once, as he was coasting along near the site of Wilmington, N. C., on account of the high surf a boat could not land, but a bold young sailor swam to the shore and tossed a gift of trinkets to some Indians gathered on the beach. A moment later the sea threw him helpless and bruised at their feet. In an instant he was seized by the arms and legs and, crying lustily for help, was borne off to a great fire—to be roasted on the spot, his shipmates did not doubt. On the contrary, the natives warmed and rubbed him, then took him down to the shore and watched him swim back to his friends.

René de Laudonnière's Expedition to the St. John's.—Absurd Illusions of the Frenchmen.—Their Bad Faith to the Indians, and its Fatal Results.—The Thirst for Gold, and how it was rewarded.—Buccaneering.—A Storm-cloud gathers in Spain.—Misery in the Fort on the St. John's.—Relieved by Sir John Hawkins.—Arrival of Ribaut with Men and Supplies.—Don Pedro Menendez captures Fort Caroline and massacres the Garrison and Shipwrecked Crews.—Dominique de Gourgues takes Vengeance.

The failure at Port Royal did not discourage Admiral Coligny from sending out another expedition, in the spring of 1564, under the command of Rene de Laudonnière, who had been with Ribaut in 1562. It reached the mouth of the St. John's on the 25th of June and was joyfully greeted by the kindly Indians.

The lieutenant, Ottigny, strolling off into the woods with a few men, met some Indians and was conducted to their village. There, he {78} gravely tells us, he met a venerable chief who told him that he was two hundred and fifty years old. But, after all, he might probably expect to live a hundred years more, for he introduced another patriarch as his father. This shrunken anatomy, blind, almost speechless, and more like "a dead carkeis than a living body," he said, was likely to last thirty or forty years longer.

Probably the Frenchman had heard of the fabled fountain of Bimini, which lured Ponce de Leon to his ruin, and the river Jordan, which was said to be somewhere in Florida and to possess the same virtue, and he fancied that the gourd of cool water which had just been given him might come from such a spring.[1]

{79}This example shows how credulous these Frenchmen were, moving in a world of fancy, the glamour of romantic dreams about the New World still fresh upon them, visions of unmeasured treasures of silver and gold and gems floating through their brains.

It would make a tedious tale to relate all their follies, surrounded as they were by a bountiful nature and a kindly people, and yet soon reduced to abject want. In the party there were brawling soldiers and piratical sailors, with only a few quiet, decent artisans and shop-keepers, but with a swarm of reckless young nobles, who had nothing to recommend them but a long name, and who expected to prove themselves Pizarros in fighting and treasure-getting. Unfortunately, the kind of man who is the backbone of a colony, "the man with the hoe," was not there.

This motley crew soon finished a fort, which stood on the river, a little above what is now called St. John's Bluff and was named Fort {80} Caroline, in honor of Charles the Ninth. Then they began to look around, keen for gold and adventure.

The Indians had shown themselves hostile when they saw the Frenchmen building a fort, which was evidence that they had come to stay. Laudonnière quieted the chief Satouriona by promising to aid him against his enemies, a tribe up the river, called the Thimagoas. Next, misled by a story of great riches up the river, he actually made an alliance with Outina, the chief of the Thimagoas. Thus the French were engaged at the same time to help both sides. But the craze for gold was now at fever-heat, and they had little notion of keeping faith with mere savages. Outina promised Vasseur, Laudonnière's lieutenant, that if he would join him against Potanou, the chief of a third tribe, each of his vassals would reward the French with a heap of gold and silver two feet high. So, at least, Vasseur professed to understand him.

The upshot of the matter was that Satouriona was incensed against the French for breaking faith with him. And to make the situation worse, when he went, unaided, and attacked his enemies and brought back prisoners, the French {81} commander, to curry favor with Outina, compelled Satouriona to give up some of his captives and sent them home to their chief.

All this was laying up trouble for the future. Not a sod had the Frenchmen turned in the way of tilling the soil. The river flowing at their feet teemed with fish. The woods about them were alive with game. But they could neither fish nor hunt. Starving in a land of plenty, ere long they would be dependent for food on these people who had met them so kindly, and whom they had deliberately cheated and outraged.

Next we find Vasseur sailing up the river and sending some of his men with Outina to attack Potanou, whose village lay off to the northwest. Several days the war-party marched through a pine-barren region. When it reached its destination the Frenchmen saw, instead of a splendid city of the "kings of the Appalachian mountains," rich in gold, just such an Indian town, surrounded by rough fields of corn and pumpkins, as the misguided Spaniards under Soto had often come upon. The poor barbarians defended their homes bravely. But the Frenchmen's guns routed them. Sack and slaughter followed, with the burning of the town. Then the victors {82} marched away, with such glory as they had got, but of course without a grain of gold.

At Fort Caroline a spirit of sullenness was growing. Disappointment had followed all their reckless, wicked attempts to get treasure. The Indians of the neighborhood, grown unfriendly, had ceased to bring in food for barter. The garrison was put on half-rations. Men who had come to Florida expecting to find themselves in a land of plenty and to reap a golden harvest, would scarcely content themselves with the monotonous routine of life in a little fort by a hot river, with nothing to do and almost nothing to eat. It was easy to throw all the blame on Laudonnière.

"Why does he not lead us out to explore the country and find its treasures? He is keeping us from making our fortunes," the gentlemen adventurers cried.

Here again we are reminded of the Spaniards under Narvaez and Soto, who struggled through the swamps and interminable pine-barrens of Florida, cheered on by the delusive assurance that when they came to the country of Appalachee they would find gold in abundance. (See "Pioneer Spaniards in North America.")

{83}Another class of malcontents took matters into their own hands. They were ex-pirates, and they determined to fly the "jolly Roger" once more. They stole two pinnaces, slipped away to sea, and were soon cruising among the West Indies. Hunger drove them into Havana. They gave themselves up and made their peace with the Spanish authorities by telling of their countrymen at Fort Caroline.

Now, Spain claimed the whole of North America, under the Pope's grant. Moreover, Philip of Spain had but lately commissioned as Governor of Florida one Pedro Menendez de Aviles, a ruthless bigot who would crush a Protestant with as much satisfaction as a venomous serpent. Imagine the effect upon his gloomy mind of the news that reached him in Spain, by the way of Havana, of a band of Frenchmen, and, worst of all, heretics settled in Florida, his Florida!

Meanwhile the men at Fort Caroline, all unconscious of the black storm brewing in Spain, continued their grumbling. They had not heard of the fate of the party who had sailed away, and now nearly all were bent on buccaneering. One day a number of them mutinied, overpowered the {84} guard, seized Laudonnière, put him in irons, carried him on board a vessel lying in the river, and compelled him, under threat of death, to sign a commission for them to cruise along the Spanish Main. Shortly afterward they sailed away in two small vessels that had been built at Fort Caroline.

After their departure, the orderly element that remained behind restored Laudonnière to his command, and things went on smoothly for three or four months. Then, one day, a Spanish brigantine was seen hovering off the mouth of the river. It was ascertained that she was manned by the mutineers, now anxious to return to the fort. Laudonnière sent down a trusty officer in a small vessel that he had built, with thirty soldiers hidden in the hold. The buccaneers let her come alongside without suspicion and began to parley. Suddenly the soldiers came on deck, boarded, and overpowered them, before they could seize their arms. In fact, they were mostly drunk. After a short career of successful piracy, they had suddenly found themselves attacked by three armed vessels. The most were killed or taken, but twenty-six escaped. The pilot, who had been carried away against his will, cunningly steered {85} the brigantine to the Florida coast; and, having no provisions, they were compelled to seek succor from their old comrades. Still they had wine in abundance, and so they appeared off the mouth of the river drunk, and, as we have seen, were easily taken. A court-martial condemned the ringleader and three others to be shot, which was duly done. The rest were pardoned.

In the meantime the men in the fort had been inquiring diligently in various directions. There was still much talk of mysterious kingdoms, rich in gold. Once more they were duped into fighting his battles by the wily Outina, who promised to lead them to the mines of Appalachee. They defeated his enemies, and there was abundant slaughter, with plenty of scalps for Outina's braves, but, of course, no gold.

The expected supplies from France did not come. The second summer was upon them, with its exhausting heat. The direst want pinched them. Ragged, squalid, and emaciated, they dragged themselves about the fort, digging roots or gathering any plant that might stay the gnawings of hunger. They had made enemies of their neighbors, Satouriona and his people; and Outina, for whom they had done so much, sent them only {86} a meagre supply of corn, with a demand for more help in fighting his enemies. They accepted the offer and were again cheated by the cunning savage.