The Project Gutenberg EBook of The South Sea Whaler, by W.H.G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The South Sea Whaler

Author: W.H.G. Kingston

Illustrator: W.H.C. Groome

Release Date: May 15, 2007 [EBook #21479]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SOUTH SEA WHALER ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

W.H.G. Kingston

"The South Sea Whaler"

Chapter One.

The Champion Whaler—The Captain and his Children—Sights at Sea—Frigate-Birds and Flying-Fish—A Bonito—Catching Albatrosses—Mutinous Mutterings—A Timely Warning.

“A prosperous voyage, and a quick return, Captain Tredeagle,” said the old pilot as he bade farewell to the commander of the Champion, which ship he had piloted down the Mersey on her voyage to the Pacific.

“Thank you, pilot. I suppose it will be pretty nearly three years before we are back again,—with a full cargo, I hope, and plenty of dollars to keep the pot boiling at home. It’s the last voyage I intend to make; for thirty years knocking about at sea is enough for any man.”

“Many say that, captain; but when the time comes they generally find a reason for making one voyage more, to help them to start with a better capital. But as you have got your young ones aboard, you will have their company to cheer you.”

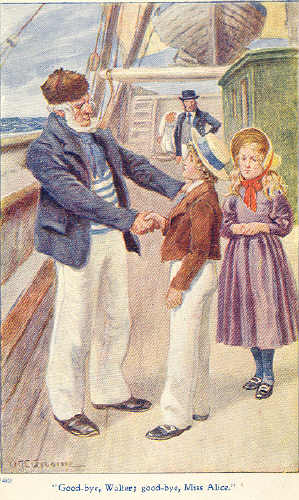

As the old pilot stepped along the deck he shook hands with two young people, a boy and a girl, who were standing near the gangway.

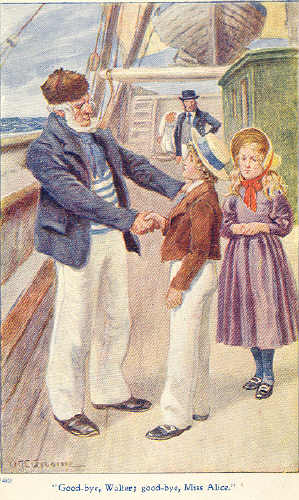

“Good-bye, Walter; good-bye, Miss Alice; look after father, and obey him, and God will bless you. If we are all spared, I hope to see you, Walter, grown into a tall young man; and you, Miss Alice, I suppose I shan’t know you again. Good-bye; Heaven protect you.” Saying this, the old pilot lowered himself into his boat alongside, and pulled away for his cutter, which lay hove-to at a little distance.

The Champion was a South Sea whaler of about four hundred tons burden; with a crew, including Mr Andrew Lawrie, the surgeon, of fifty officers and men. The chief object of the voyage was the capture of the sperm whale,—which creature is found in various parts of the Pacific Ocean; but as the war in which England had been engaged since the commencement of the century was not over, she carried eight guns, which would serve to defend her both against civilised enemies and the savage inhabitants of the islands she was likely to visit. The usual license for carrying guns, or “Letters of Marque,” had been obtained for her by the owners; she was thus able not only to defend herself, but to attack and capture, if she could, any vessels of the enemy she might meet with. Captain Tredeagle, being a peace-loving man, had no intention of exercising this privilege,—his only wish being to dispose of the ventures he carried, and to obtain by honest exertions a full cargo of sperm oil.

Walter and Alice waved their hands to the old pilot, as his little vessel, close-hauled, stood away towards the mouth of the river. It seemed to them that in parting from him the last link which bound them to their native land was severed. They left many friends behind them; but it was their father’s wish that they should accompany him, and they eagerly looked forward to the pleasure of seeing the beautiful islands they were likely to visit, and witnessing the strange sights they expected to meet with during the voyage.

While the pilot vessel was standing away, the head-yards of the Champion were swung round, the sails sheeted home; with a brisk northerly wind, and under all the canvas she could carry, she ran quickly down the Irish Channel.

“Here we are away at last,” said Captain Tredeagle, as his children stood by his side; “and now, Walter, we must make a sailor of you as fast as possible. Don’t be ashamed to ask questions, and get information from any one who is ready to give it. Our old mate, Jacob Shobbrok, who has sailed with me pretty nearly since I came to sea, is as anxious to teach you as you can be to get instruction; but remember, Walter, you must begin at the beginning, and learn how to knot and splice, and reef, and steer, and box the compass, before you begin on the higher branches of seamanship. You will learn fast enough, however, if you keep your eyes and ears open and your wits about you, and try to get at the why and wherefore of everything. Many fail to be worth much at sea as well as on shore, because they are too proud to learn their A B C. Just think of that, my son.”

“I will do my best, father, to follow your advice,” answered Walter, a fine lad between fourteen and fifteen years of age. His sister Alice was two years younger,—a fair, pretty-looking girl, with the hue of health on her cheeks, which showed that she was well able to endure the vicissitudes of climate, or any hardships to which she might possibly be subjected at sea.

When Captain Tredeagle resolved to take his children with him, he had no expectation of exposing them to dangers or hardships. He had been thirty years afloat, and had never been wrecked, and he did not suppose that such an occurrence was ever likely to happen to him. He forgot the old adage, that “the pitcher which goes often to the well is liable to be broken at last.” He had lost his wife during his previous voyage, and had no one on whom he could rely to take care of his motherless children while he was absent from home. Walter had expressed a strong wish to go to sea, so he naturally took him; and with regard to Alice, of two evils he chose that which he considered the least. He had seen the dangers to which girls deprived of a mother’s watchful care are exposed on shore, and he knew that on board his ship, at all events, Alice would be safe from them. Having no great respect for the ordinary female accomplishments of music and dancing, he felt himself fully competent to instruct her in most other matters, while he rightly believed that her mind would be expanded by visiting the strange and interesting scenes to which during the voyage he hoped to introduce her. “As for needle-work and embroidery, why, Jacob and I can teach you as well as can most women; and our black fellow Nub will cut out your dresses with all the skill and taste of a practised mantua-maker,” he had said when talking to Alice on the subject of her going.

Alice was delighted to accompany her father, and hoped to be a real comfort to him. She would take charge of his cabin and keep it in beautiful order, and repair his clothes, and take care that a button was never wanting; and would pour out his coffee and tea, and write out his journal and keep his accounts, she hoped. And should he fall sick, how carefully she would watch over him; indeed, she flattered herself that she could be of no slight use. Then, she might be a companion to Walter, who might otherwise become as rough and rude as some ship-boys she had seen; not that it was his nature to be rough, she thought, but she had often written in her copy-book, “Evil communications corrupt good manners,” and Walter’s truly good manners might deteriorate among the rough crew of the whaler. Alice also intended to be very diligent with her books, and she could learn geography in a practical way few young ladies are able to enjoy. And, lastly, she had a sketch-book and a colour-box, by means of which she hoped to make numberless drawings of the scenery and people she was to visit. Altogether, she was not likely to find the time hang heavy on her hands.

In many respects she was not disappointed in her expectations. As soon as the ship was clear of the Channel and fairly at sea, her father began the course of instruction he intended to pursue during the voyage. Mr Jacob Shobbrok the mate, and Nub, delighted to impart such feminine accomplishments as they possessed; and it amused her to see how deftly their strong hands plied their needles.

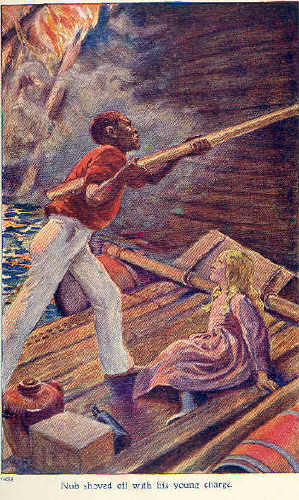

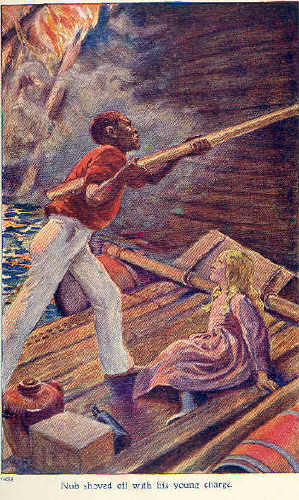

Nub, as the black steward was generally called, had been for the best part of his life at sea with her father. He had been christened Nubia, which name was abridged into Nub; and sometimes she and Walter, when they were little children, had been accustomed, as a term of endearment, to call him “Nubby,” and even now they frequently so called him. He was truly devoted to his captain’s children, but more especially were the affections of the big warm heart which beat in his black bosom bestowed upon Alice. It is no exaggeration to say that he would gladly have died to save her from harm.

Alice, indeed, was perfectly happy, not feeling the slightest regret at having left England. The weather was fine, the sea generally smooth, and the ship glided so rapidly on her course that Alice persuaded herself she was not likely to encounter the storms and dangers she had heard of. She carried out her intentions with exemplary perseverance. Never had the captain’s cabin been in such good order. She learned all the lessons he set her, and read whenever she had time; she plied her needle diligently; and Mr Shobbrok took especial delight in teaching her embroidery, in which, notwithstanding the roughness of his hands, he was an adept. Indeed, not a moment of her time was idly spent. She took her walks regularly on deck during the day, with her father or Walter: and when they were engaged, Nub followed her about like her shadow; not that he often spoke to her, but he seemed to think that it was his duty ever to be on the watch to shield her from harm.

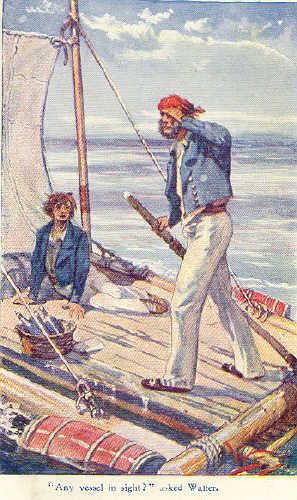

Walter, in the meantime, was picking up a large amount of nautical knowledge: for he, like his sister, was always diligent, and, following his father’s advice, never hesitated to ask for information from those about him; and as he was always good-natured and good-tempered, and grateful for help received, it was willingly given. He was as active and daring as any of the crew, and he could soon lay out on the yards and assist in reefing topsails as well as anybody on board. He could soon, also, take his trick at the helm in fine weather; indeed, it was generally acknowledged that he gave good promise of becoming a prime seaman. The crew were constantly exercised at their guns; and Walter, though not strong enough to work at them himself, soon thoroughly understood their management, and could have commanded them as well as any of the officers. He also studied navigation under his father in the cabin, and could take an observation and work a day’s work with perfect accuracy. He advanced thus rapidly in his professional knowledge, not because he possessed any wonderful talent except the very important one of being able to give his mind to the subject, and in being diligent in all he undertook. He was happy and contented, because he really felt that he was making progress, and every day adding to his stock of knowledge. He had also the satisfaction of being conscious that he was doing his duty in the sight of God as well as in that of man: he was obedient, loving, and attentive to his father, from the highest of motives,—because God told him to be so, not in any way from fear, or because he felt that it was his interest to obey one on whom he depended for support. Captain Tredeagle himself was a truly religious, God-fearing man; that is to say, he feared to offend One who, he knew, loved him and had done so much for him—an all-pure and all-holy God, in whose sight he ever lived—and therefore did his best to bring up his children in the fear and nurture of the Lord; and he had reason to be thankful that his efforts were not in vain.

Had all his crew been like Captain Tredeagle, his would have been a happy ship. His good mate, Jacob Shobbrok, was in some respects like him; that is to say, he was a Christian man, though somewhat rough in his outward manner and appearance, for he had been at sea all his Life. He was an old bachelor, and had never enjoyed the softening influence of female society. Still his heart was kind and gentle. Both Alice and Walter, having discernment enough to discover that, were accordingly much attached to him. There were several other worthy men on board. Andrew Lawrie, the surgeon, was in most respects like Jacob, possessing a kind, honest heart, with a rough outside. Nub has been described. He made himself generally popular with the men by his good temper and jokes, and by bearing patiently the ill-treatment to which he was often subjected by the badly disposed among them. But though kicked, rope’s-ended, and made to perform tasks which it was not his duty to do, he never complained or showed any vindictive feeling. His chief friend was Dan Tidy. Dan, who had not been long at sea, and consequently was not much of a sailor, was quite as badly treated as Nub, but did not take it with nearly the same equanimity. He generally retaliated, and many a tough battle he had to fight in consequence. But though he was often beaten, his spirit had not given way. A common suffering united him and Nub, and when they could they helped each other.

A large portion of the crew were rough, ignorant, and disorderly. The war had kept all the best men employed, and even a well-known commander like Captain Tredeagle had a difficulty in getting good men; so that the few only who had constantly sailed with him could be depended on. The rest would remain with him and do their duty only so long as they thought it their interest. And though he did his utmost to keep up strict discipline, he was obliged to humour them more than he would have been justified in doing under other circumstances. Though he might have used the lash,—very common in those days,—to flog men was repugnant to his feelings, and he preferred trying to keep them in order by kindness. Unhappily, many of them were of too brutal a nature to understand his object, so they fancied that he treated them as he did from timidity. Old Jacob Shobbrok urged stronger measures when some of the men refused to turn out to keep their watch, or went lazily about their work.

“We shall have the masts whipped out of the ship, if we don’t trice up some of these fellows before long,” he observed one day to the captain.

“Wait a bit, Jacob,” answered Captain Tredeagle; “I will try them a little longer; but you can just let them know that if any of them again show a mutinous disposition, they will be flogged as surely as they are living men.”

“They don’t understand threats, captain,” answered Jacob. “There’s nothing like the practical teaching the cat affords with fellows of this description. I’ll warn them, however, pretty clearly; and if that don’t succeed, I must trust to you to show them that you will stand it no longer.”

Jacob did not fail to speak to the men as he promised, and for a time they went on better; but the spirit of insubordination still existed among them, and gave the good captain much concern.

The boatswain, Jonah Capstick, who ought to have been the first to preserve discipline, was among the worst. It was the first voyage he had made with Captain Tredeagle, to whom he had been recommended as a steady man. One of his mates, Tom Hulk,—well named, for he was a big hulking ruffian,—was quite as bad, and with several others supported the boatswain.

Alice knew nothing of what was going forward, though Walter suspected that things were not quite right.

The great delight of Alice, as the ship entered the tropics, was to watch the strange fish which swam about the ship as she glided calmly on; to observe the ocean bathed in the silvery light of the moon, or the sun as it sank into its ocean bed, suffusing a rich glow over the sky and waters.

She and Walter were one day standing on deck together, when, looking up, they saw a small black dot in the blue sky.

“What can that be?” asked Alice. “It seems as if some one had thrown a ball up there. Surely it cannot be a balloon such as I have read of, though I never saw one.”

“That is not a balloon, but a living creature,” observed Jacob, who had overheard her. “It is a frigate-bird watching for its prey; and before long we shall see it pounce down to the surface of the ocean if it observes anything to pick up, though it is a good many hundred feet above our heads just now.”

“See! see! what are those curious creatures which have just come out of the water? Why, they have wings! Can they be birds?” she exclaimed.

“No; those are flying-fish,” said Walter, who knew better than his sister.

“And the frigate-bird has espied them too,” exclaimed the mate. “Here he comes.”

As he spoke, a large bird came swooping down like a flash of lightning from the heavens; and before the flying-fish, with their wings dried by the air, had again fallen into the water, it had caught one of them in its mouth. Swallowing the fish, the bird rapidly ascended, to be ready for another pounce on its prey. The flying-fish had evidently other enemies below the surface, for soon afterwards they were seen to rise at a short distance ahead; and once more the bird, descending with the same rapid flight as before, seized another, which it bore off.

“Poor fish! how cruel of the bird to eat them up,” cried Alice.

“It is its way of getting its dinner,” said the mate, laughing. “You would not object to eat the fish were they placed before you nicely fried at breakfast. Many seamen have been thankful enough to get them, when their ship has gone down and they have been sailing in their boats across the ocean, hard pressed by hunger.”

“I was foolish to make the remark,” said Alice; “and yet I cannot help pitying the beautiful flying-fish, snapped up so suddenly. But how can the bird come out here, so far away from land? Where can it rest at night?”

“It can keep on the wing for days and days together,” answered the mate. “It is enabled to do this by having the muscles of its breast, which work the wings, of wonderful strength, while the rest of the body is exceedingly light. Its feet are so formed that it cannot rest on the surface of the water as do most other sea-birds; which proves what I say about its powers of flying.”

The bird which he was describing was of a rich black plumage, the throat being white and the beak red. Nothing could be more graceful than the way it hovered above the ship in beautiful undulations, or the rapidity with which it darted on its prey. Alice and Walter stood admiring it.

“It is a determined pirate,” observed the mate. “When it cannot catch fish for itself, it watches for the gannets and sea-swallows after they have been out fishing all day, and darting down upon them, compels them in their fright to throw some of their prey out of their crops, when it is caught by the plunderer before it reaches the water. The gannets are such gluttons, they generally fly home so full of fish that they are unable to close their beaks. If the gannet does not let some of the fish fall, the frigate-bird darts rapidly down and strikes it on the back of the head; on which it never fails to give up its prey to the marauder.”

“Though I cannot, I must confess, help admiring the beauty of the frigate-bird, robber as he is, my sympathy is all with the flying-fish,” said Alice.

“They are certainly to be pitied,” said the mate; “for they have enemies in the water and out of it. Several of those we saw just now are by this time down the throats of the albicores or bonitoes, which are following them. To try to escape from their foes, they rise out of the water, and fly fifty yards or more, till, their wings becoming dry, they cannot longer support themselves, when they fall back again into the sea, if they are not in the meantime picked up by a frigate-bird or some other winged enemy. I have known a dozen or more fly into a boat, or even on to the deck of a ship; and very delicate they are when cooked, though hungry people are glad enough to eat them raw.”

Sometimes at night Alice came on deck, when the stars were shining brightly and the ship was bounding over the waves, to watch the foam as it was dashed from off the bows to pass hissing by, covered with sparks of phosphorescent light, while the summits of the dark waves in every direction shone with the utmost brilliancy. The strange light, her father told her, was produced by countless millions of minute creatures, or, as some supposed, by decomposed animal matter. She delighted most, however, in going on deck on a calm night, when the moonbeams cast their soft light upon the ocean, and the ship seemed to be gliding across a sea of burnished silver. Walter now regularly took his watch, and never failed to call her when he knew she would be interested in any of the varied beauties which the changing ocean presented.

Frequently the ship was surrounded by bonitoes, moving through the waters much like porpoises; and the seamen got their harpoons ready, to strike any which might come near.

As the ship one day was gliding smoothly on, the boatswain descended to the end of the dolphin-striker, a spar which reaches from the bowsprit down almost to the water. Here he stood, ready to dart his harpoon at any unwary fish which might approach. Walter and Alice were on the forecastle watching him. They had not long to wait before a bonito came gambolling by. Quick as lightning the harpoon flew from his hand, and was buried deeply in the body of the fish. A noose was then dexterously slipped over its head and another over its tail, and it was quickly hauled up on deck by the crew. It was a beautiful creature, rather more than three feet long, with a sharp head, a small mouth, large gills, silvery eyes, and a crescent-shaped tail. Its back and sides were greenish, but below it was of a silvery white. The body was destitute of scales, except on the middle of the sides, where a line of gold ran from the head to the tail.

Alice was inclined to bemoan its death; but Walter assured her afterwards that she need not expend her pity on it, as three flying-fish had been found in its inside. Several other bonitoes were caught which had swallowed even a greater number. Indeed, they are the chief foes of the flying-fish, which, had not the latter the power of rising out of the water to escape them, would quickly be exterminated.

Some of the officers got out lines and hooks baited with pieces of pork; not to attract fish, however, but to catch some of the numerous birds flying astern and round the ship. Several flights of stormy petrels had long been following in the wake of the ship, with other birds,—such as albatrosses, cape-pigeons, and whale-birds. No sooner did a pigeon see the bait than it pounced down and seized it in its mouth, when a sharp tug secured the hook in its bill, and it was rapidly drawn on board. Several stormy petrels, which the sailors call “Mother Carey’s chickens,” were also captured. They are among the smallest of the web-footed birds, being only about six inches in length. Most of the body is black, glossed with bluish reflections; their tails are of a sooty-brown intermingled with white. In their mode of flight, Walter remarked that they resembled swallows: rapidly as they darted here and there, now resting on the wing, now rising again in the air; uttering their clamorous, piercing cries, as they flocked together in increasing numbers.

“We shall have rough weather before long, or those birds would not shriek so loudly,” observed Jacob to Walter. “I don’t mind a few of them; but when they come in numbers about a ship, it is a sure sign of a storm.”

“We have had so much fine weather, that I suppose it is what we may expect,” answered Walter. “We cannot hope to make a long voyage without a gale now and then!”

“It is not always the case,” said the mate. “I have been round the world some voyages with scarcely a gale to speak of; and at other times we have not been many weeks together without hard weather.”

Though the stormy petrel shrieked, the wind still remained moderate, and the sailors continued their bird-catching and fishing.

Among those who most eagerly followed the cruel sport was Tom Hulk, the boatswain’s mate. He had got a long line and a strong hook, which he threw overboard from the end of the main-yard.

“I don’t care for those small birds,” he cried out. “I have made up my mind to have one of the big albatrosses. I want his wings to carry home with me, and show what sort of game we pick up at sea.”

Several of his messmates, who had a superstitious dread of catching an albatross, shouted out to him not to make the attempt, declaring that he would bring ill-luck to himself, or perhaps to the ship. Though not free from superstition himself, he persevered from very bravado.

“I am not to be frightened by any such notions,” he answered scornfully. “If I can catch an albatross I will, and wring his neck too.”

Before long, a huge white albatross, with wide-extended wings, which had been hovering about the ship, espying the bait darted down and swallowed it at a gulp, hook and all. In an instant it was secured, and the bold seaman came running in along the yard to descend on deck; while the bird, rising in the air, endeavoured to escape. Its efforts were in vain; for several other men aiding Hulk, in spite of its struggles it was quickly drawn on board. Even then it fought bravely, though hopelessly, for victory; but its captor despatched it with a blow on the head.

“It would have been better for you if you had let that bird enjoy its liberty,” said the boatswain with a growl. “I have never seen any good come from catching one of them.”

“Did you ever see any harm come?” innocently asked Walter, who had come forward to look at the bird.

“As to that, youngster, it’s not to every question you will get an answer,” growled the boatswain, turning away. Walter, though liked by most on board, was not a favourite of the surly boatswain, who, for his own reasons, objected to have the keen eyes of the sharp-witted boy observing his proceedings.

Walter, begging Hulk to stretch out the bird’s wings, went to bring Alice to look at it. He told her what the boatswain had said about the ill-luck which would pursue those who killed an albatross.

“Depend on it, God would not allow what He has ordained to be interfered with by any such occurrence,” observed the captain to his children. “It may be a cruel act to kill a bird without any reason; but though persons who have caught or shot albatrosses may afterwards have met with accidents, it does not at all follow that such is the result of their former acts. I have seen many albatrosses killed, and the people who killed them have returned home in safety; though possibly accidents may have occurred in other instances to those who have killed one of the birds. Still seamen have got the notion into their heads, and it is very hard to drive it out.”

“I am sure of that,” said Walter, “though the boatswain was quite angry with me for doubting what he asserted.”

While he was speaking, another large albatross came sweeping by.

“For my part, I am not afraid of catching a second,” exclaimed Hulk; “and if there is ill-luck in killing one, there may be good luck in catching two.” Saying this, he prepared his hook and line, and was ascending to the yard to let it tow overboard as before.

“It will be a good thing for you if you do catch two,” exclaimed the boatswain. “We want good luck for the ship, for little enough of it we have had as yet.” But before Hulk could get out his line the albatross was seen to swoop downwards, and immediately afterwards it rose with a huge fish in its talons, into which it plunged its powerful beak with a force which must have speedily put an end to its prey. Powerful, however, as were its wings, it could not rise with so great a weight, but commenced tearing away at the flesh of its victim as it floated on the surface. It thus offered a fair mark to any who might wish to shoot it. Three of the ship’s muskets were brought up by some of the younger officers, who were about to fire.

“Let me have a shot,” said the boatswain, taking one of them. “I seldom miss my aim.”

The captain, who had been below, just then coming on deck, observing what they were about, ordered them to desist, observing—

“I don’t wish to lower a boat to pick up the bird, and I consider it wanton cruelty to shoot at it.”

The boatswain pretended not to hear him, and taking aim, he fired. The bird was seen to let go its prey, and, after rising a few feet, to fall back with wings extended into the water, where it lay fluttering helplessly. The ship gliding on, soon left it astern.

“I consider that a piece of wanton cruelty, Mr Capstick,” exclaimed the captain. “I must prohibit the ship’s muskets being made use of for such a purpose; they are intended to be used against our enemies, not employed in slaughtering harmless birds.”

The boatswain returned the musket to the rack, muttering as he did so; but what he said neither the captain nor his mates were able to understand.

The ship had now nearly reached the latitude of the Falkland Islands, and in a short time she would be round Cape Horn, and traversing the broad waters of the Pacific. Hitherto few ships had been seen, either friends or foes; a lookout had been kept for the latter, as the crew hoped that, should they fall in with an enemy’s merchantman of inferior size, the captain would capture her to give them some much coveted prize-money. Two had been seen which were supposed to be small enough to attack, but the captain had declined going in chase of them, greatly to the annoyance of the crew; and the boatswain and others vowed they would not longer stand that sort of thing.

Walter was walking the deck during his middle watch the next night, when Dan Tidy came up to him.

“Hist, Mr Walter,” he said in a low voice. “Will you plaise just step to the weather-gangway, out of earshot of the man at the helm? I have got something I would like to say to you.”

Walter stepped to the gangway, and, seeing no one near, asked Tidy what he had to communicate.

“I wouldn’t wish to be an eavesdropper or a tale-bearer, Mr Walter; but when the lives of you and your father and most of the officers are at stake, it’s time to speak out. I happened to be awake during my watch below when the boatswain came for’ard, and I heard him and Tom Hulk and about a dozen others talking in whispers together. I lay still, pretending to be asleep, as, of course, they thought were the rest of the watch. Capstick began grumbling at the chance there was that we should take no prizes; and declared that, for his part, he was not going to submit to that sort of thing. The others agreed with him, and swore that they would stand by him, and do whatever he proposed. Some said that the best thing would be to go to the captain, and insist that he should attack the first enemy’s merchantman they could fall in with. ‘And the captain will tell you to mind your own business, and that he intends to act as he considers is most for his own interest and that of the owners,’ said Hulk, with an oath. ‘I tell you, the only thing we can do is to make him and his young fry, and the old mate and some of the rest of them, prisoners; or, better still, knock them on the head and heave them overboard, and then we will make the boatswain captain, and live a life of independence, just taking as many prizes as we want, and never troubling ourselves to give an account of them to the owners.’ Some agreed to this, and some didn’t seem to like the thought of it; but they were talked over by the boatswain and Hulk, and agreed to what they proposed. I cannot say, however, when they intend to carry out their plan. They talked on for some time longer, and then they all turned into their hammocks. I lay as quiet as a mouse in a cheese, and when I thought they were all asleep slipped up on deck to tell you or the mate, if I could manage to speak to either of you unobserved, that you might let the captain know of their intentions towards him.”

Walter, though considerably agitated at this information, acted with much discretion, telling Tidy to keep the matter to himself, and to behave towards the intended mutineers as he had always done, without letting them have a shade of suspicion that he had discovered their plot. Having no fear, from what Tidy said, that they intended carrying it out immediately, he waited till his watch was over to inform his father and the chief mate. Bidding Tidy go below and turn in again, he resumed his walk on deck.

They would probably, he thought, wait for a change of weather and a dark night to execute their project which, it was evident, was not as yet fully matured.

The second mate had charge of the watch, but Walter was unwilling to communicate the information to him; for, though an honest man, he somewhat doubted his discretion. It was an anxious time for the young boy, but his courage did not quail, as he felt sure that his father and Mr Shobbrok, aided by the other officers and the better-disposed part of the crew, would be able to counteract the designs of the mutineers.

Chapter Two.

Precautions—A Mutiny—Mutineers Defeated—Attempt to round Cape Horn—Driven back—A Fearful Gale—Amidst Icebergs—A Magnificent Sight—Man Overboard—Mutineer killed by an Albatross.

Walter was thankful to hear eight bells strike, when Mr Shobbrok coming on deck, sent the second mate below.

“Why don’t you turn in, Walter?” asked the first mate, on seeing him still lingering on deck.

“I should like to speak a word to you,” said Walter.

“If it’s a short one, my lad, say it, but I don’t wish to keep you out of your berth.”

As several of the mutineers were on deck, Walter thought he might be observed, and therefore merely whispered to the mate, “Be on your guard. I have information that the boatswain is at the head of a conspiracy to take possession of the ship. I will go below and tell my father how matters stand. Be careful not to be taken at a disadvantage, and let none of the men come near you.”

“I am not surprised. I will be on my guard,” answered the mate in a low tone; adding in a higher one—

“Now go below, youngster, and turn in.”

Walter, hurrying to the cabin, found his father asleep. A touch on the arm awoke him.

“I want to speak to you about something important,” he said; and then told him all he had heard from Dan Tidy.

“It does not surprise me,” he observed, repeating almost the words of the mate. “We of course must take precautions to counteract the designs of the misguided men without letting them suspect that we are aware of their intentions. Call Mr Lawrie, that I may tell him what to do; and then I will go on deck and speak to the first mate.”

“I have told him already. I thought it better to put him on his guard,” said Walter.

“You did right,” said the captain. “We must let the other officers know. Bring me two brace of pistols from the rack.” The captain quickly loaded the firearms. “Now, Walter, do you go and wake up Nub; then bring all the muskets into my cabin while I am on deck.”

The captain’s appearance would not excite suspicion, as it is customary for a commander to go on deck at all hours of the night, especially when there is a change of weather; and the mate was heard at that moment ordering the watch on deck to shorten sail. Captain Tredeagle did not interfere, but allowing the mate to give the necessary orders, waited till the topgallant-sails were furled and two reefs taken in the topsails. He then went across to where Mr Shobbrok was standing.

“Walter has told me what the men intend doing,” he said in a low voice. “Do you try and find out who are likely to prove stanch to us.”

“I think we may trust nearly half the crew,” answered the mate; “and I will try and speak to those on whom we can most certainly rely. Tidy will be able to point them out.”

“In case they should attempt anything immediately, here are the means of defending yourself,” said the captain; and finding that none of the men were observing him, he put a brace of pistols into the mate’s hands.

“Who is at the helm?” he asked.

“Tom Hulk,” answered the mate.

“He is among the ringleaders,” said the captain; “he will be suspicious if he sees us talking together. I’ll warn Beak, that he may be on the alert, and will send him to speak with you.”

The captain crossed the deck to where Mr Beak, the fourth mate, was standing. Telling him of the conspiracy which had been discovered, he put a pistol into his hand, and desired him to go over and speak with the first mate, who would direct him what to do. On returning below, he found that Walter and Nub had carried out his orders, and that Mr Lawrie had awakened the other two mates, who soon made their appearance in the cabin. Two midshipmen, or rather apprentices, who slept further forward, had now to be warned. Nub undertook to do this without exciting the suspicion of the mutineers. The captain in the meantime gave the officers the information he had received, and told them the plan he proposed following,—assuring them that they had only to be on the alert and to remain firm, and that he had no doubt, should the mutineers proceed to extremities, they would soon be put down; no one, however, felt inclined to turn in again, not knowing at what moment the mutiny might break out. Had the boatswain and his companions guessed that Tidy had overheard their conversation, they would have lost no time in carrying out their plan, and would probably have caught the captain unprepared.

The night passed quietly away, and when morning came the mutineers went about their duty as usual. Notwithstanding the threatenings of a gale on the previous evening, the wind continued fair and moderate, and the ship was standing on under all sail.

Breakfast was over, and the captain and mate, with Walter, were standing with their sextants in hand taking an observation to ascertain the ship’s latitude. Mr Lawrie having been in his surgery mixing some medicines for two men who were on the sick-list, was going forward when he observed a number of the crew with capstan-bars, boat-stretchers, and other weapons in their hands, the boatswain and Tom Hulk being among them. He at once hurried to the captain and told him what he had seen.

“Call aft the men whom we selected as a guard, Mr Shobbrok,” whispered the captain—“Let the officers arm themselves, but keep out of sight in the cabin, ready to act if necessary.”

The mate had agreed on a private signal with the trustworthy men. He was to let fly the mizzen-royal, when they were to come aft on the pretence of hauling in the sheet. This would give them the start of the mutineers, and allow them time to obtain arms,—though of course the object of the device would quickly be perceived.

The captain and Walter went on taking their observation full in sight of the crew forward, as if there were nothing to trouble them. The mate made the signal agreed on. As the sail fluttered in the wind, Dan Tidy and eight others came running aft, and immediately the muskets, which had already been loaded, were handed up from below and placed in their hands. So quick had been their movements that the mutineers, who had been looking at the captain, had not observed them; and, confiding in their numbers, and not knowing that the officers were armed or prepared for them, came rushing aft, led by the boatswain, uttering loud shouts, to intimidate their opponents. The captain stood perfectly calm, with Walter by his side.

“What does this strange conduct mean, my men?” he asked, turning round.

“We will show you, captain,” answered the boatswain. “We want a captain who understands his own interest and ours, and won’t let the prizes we might have got hold of slip through our fingers as you have done.”

“You are under a mistake, my friends, in more ways than one,” answered the captain. “I call on all true men on board to stand by me.”

As he spoke, Tidy and the men who had come aft showed themselves with muskets in their hands; and at the same moment the officers sprang on deck, fully armed.

“Now I will speak to you,” said the captain, handing his sextant to Walter, and drawing his pistols. “The first man who advances another step must take the consequences. I shall be justified in shooting him, and I intend to do so. His blood be upon his own head. Now lay down these capstan-bars and stretchers, and tell me, had you overpowered us, what you intended to do.”

The mutineers were dumbfounded, and even the boldest could make no reply. Most of them, indeed, did as they were ordered and threw their weapons on the deck, hanging down their heads and looking ashamed of themselves. The boatswain and Hulk, and a few of the more daring, tried to brazen it out.

“All we want is justice,” blustered out the boatswain. “We shipped aboard here to fight our enemies, like brave Englishmen, and to take as many prizes as we could fall in with; but there does not seem much chance of our doing so this voyage.”

“You shipped on board to do as I ordered you, and not to act the part of sea-robbers and pirates, which is what you would wish to be,” answered the captain. “Those who intend to act like honest men, and obey orders, go over to the starboard side; the rest stand on the other.”

The greater number of the crew—with the exception of the boatswain and Hulk and two others—went over to starboard. The captain then ordered the remainder of the crew to be piped on deck. They quickly came up.

“Now, my lads, those who wish to obey me and do their duty, join their shipmates on the starboard side; those who are inclined the other way, stand on one side with Mr Capstick and his mate.”

Two or three cast a look at the boatswain, but one and all went over to the starboard side. The boatswain looked greatly disconcerted, for he had evidently counted on being joined by the greater part of his shipmates.

“Now,” said the captain, “I am averse to putting men in irons, but as these have shown a spirit of insubordination which would have been destructive, if successful, to all on board, they must take the consequences. Mr Shobbrok, seize the fellows and put them in confinement below.”

The three mates, calling six other men, sprang on the mutineers, who, drawing their knives, attempted to defend themselves; but they were quickly disarmed, and their weapons being thrown overboard, their hands were lashed behind them, and they were carried below, to have the irons put on by the armourer, who was among those who could be trusted. None of the rest of the crew attempting to interfere, order was speedily restored on board the Champion.

Though the captain had quelled the mutiny, he lost the services of four of the most active of the hands; but he hoped that reflection would bring them to reason, and that, repenting of their folly, they would be willing to return to their duty.

While these events had been occurring a dark bank of clouds had been gathering to the southward; and though the ship still sailed with a fair wind, it was evident that a change was about to take place. The cloud-bank rose higher and higher in the sky.

“All hands shorten sail,” cried the captain. The crew flew aloft to obey the order and lay out on the yards, each man striving to get in the sail as rapidly as possible. Sail after sail was taken in, but before the work could be completed the gale was upon them—not a soft breeze, such as they had been accustomed to, but a sharp cutting wind, with hail and sleet, which struck their faces and hands with fearful force, benumbing their bodies, dressed only in light summer clothing. It seemed as if on a sudden the ship had gone out of one climate into another.

“This is regular Cape Horn weather,” observed the mate to Walter, who stood shivering on deck. “You had better go below and get on your winter clothing. It may be many a day before we are in summer again, if the wind comes from the westward.”

Walter hesitated, for he thought it manly to stand the cold; but his father told him to do as the mate advised, so he hastened into the cabin. He found Alice looking very much alarmed, not having been able to make out all that had been occurring. She had seen the officers come down and arm themselves, and the muskets loaded and handed out, and had supposed that they were about to encounter an enemy. Walter quieted her fears, by assuring her that though there had been danger it was all over, and that they had now only to battle with a storm, such as all good sailors are ready to encounter and overcome.

Walter was soon equipped and ready to go on deck again, and Alice wanted to accompany him.

“Why, you will be frozen if you do, so pray don’t think about it,” he answered. “I am sure father will wish you to remain in the cabin.”

The gale increased, however, and the ship rolled, pitched, tossed, and tumbled about, in a way Alice had never before experienced. She sat holding on to the sofa trying to read, and wondering why neither her father nor Walter again came below. “What could have occurred?” She heard loud peals of thunder, the sea dashing against the ship’s sides, the howling of the wind in the rigging, the stamp of the men’s feet overhead, and other noises sounding terrific in her ears. The uproar continued to increase, and the ship seemed to tumble about more and more. At last she could endure it no longer.

“I must go on deck and see what is the matter,” she said to herself putting on her cloak and hat. She endeavoured to make her way to the companion-ladder, first being thrown on one side and then on the other, and running a great risk of hurting herself. At length, however, she managed to reach the foot of the ladder. Just at that moment Walter appeared at the top of it, looking down at her. She felt greatly relieved on seeing him.

“Oh, what has happened?” she exclaimed as he came below.

“Only a regular Cape Horn gale,” he answered. “We have got the ship under close-reefed fore and main topsails, and she is behaving nobly. It is cold, to be sure; but the men have been sent below, as they could be spared, to put on warmer clothing, and we shall get out of it some day or other.”

Walter’s remarks greatly restored Alice’s spirits. She had expected to see him with alarm on his countenance, bringing her the announcement that the ship was in fearful danger. The time had not been quite so long as Alice had supposed. Nub brought in dinner for her and Walter, which he advised them to take on the deck of the cabin, as there would be little use in placing it on the table, in spite of puddings and fiddles to keep the dishes in their places.

“You see, Missie Alice, if de ship gib a roll on one side den half de soup go out, and den when she gib a roll on de oder side de oder half go out, and you get none; and de ’taties come flying ober in de same way; den de meat jump out of de dish, and before you can stop it will be on de oder side of de cabin; and de mustard and pepper pots dey go cruising about by demselves. Now, if you sit on de deck, you put de tings in one corner and you sit round dem, and when dey jump up you catch dem and put dem back, and tell dem to stop till you want to eat dem.”

Nub’s graphic description of the effects likely to be produced by the storm induced Alice and Walter to agree to his proposal, and they partook of their meal in a corner of the cabin. The latter enjoyed it, for he was very hungry. Alice could eat but little; she was, however, very anxious that her father should come down, or that he would allow her to send him up some food.

Walter laughed. “I am sure he will not do that,” he answered. “He is too much occupied at present to come below.”

When Walter went on deck again, Alice felt very forlorn. Nub, however, now and then looked in to cheer her up.

“It’s all right, Miss Alice, only de wind it blow bery hard,—enough to shave a man in half a minute. The captain told me to keep below or I turn into one icicle.” Towards the evening Nub brought in a pot of hot coffee, which he had managed to boil at the galley-fire; and presently the captain and Walter came down. The captain had no time to eat anything, but he drank two cupfuls of the coffee scalding hot.

“Bless you, my child,” he said to Alice. “We have a stormy night before us; but God looks after us, and I wish you to turn in and try and go to sleep. We are doing our best, and the ship behaves well, so keep up a good heart and all will be right.”

The mates and Mr Lawrie came down, and Nub supplied them also with coffee. The surgeon declared he could stand it no longer, and as he was not required on deck he sat down in the cabin and tried to read; but he had to give it up and stagger off to his berth. Walter at last came below again, saying that his father would not allow him to remain longer on deck; though, like a gallant young sailor, he had wished to share whatever the rest had to endure. In a very few minutes, notwithstanding the tossing of the ship and the uproar of the elements, he was fast asleep.

All night long the ship stood on close-hauled, battling bravely with the gale, showers of sleet, snow, and hail driving furiously against the faces of the crew. The captain, with his mates and both watches, remained on deck, to be ready for any emergency.

The topgallant-masts and royal-masts had been sent down; the studding-sail-booms and gear unrove, to lighten the ship as much as possible of all top hamper.

It was still dark when Walter awoke. The ship was pitching into the seas as heavily as before, and the wind roaring as loudly. He longed to go on deck to ascertain the state of things; but the captain had told him to remain in his berth till summoned, and he had learned the important duty of implicit obedience to his father’s commands. At length the light of day came down through the bull’s-eye overhead into his little berth. He quickly dressed, and entering the main cabin, found that his father had just come below. He was taking off his wet outer clothing preparatory to throwing himself on his bed.

“You go on deck now, Walter; but don’t remain long, or you will be well-nigh frozen,” he said. “I am to be called should any change in the weather take place.”

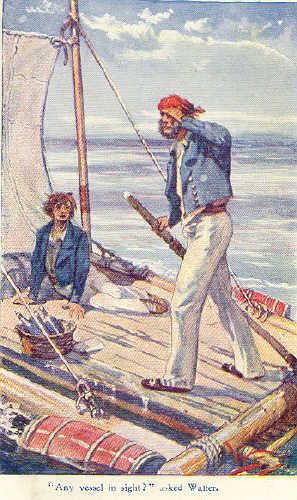

Walter sprang on deck, but he had need of all his courage to stand the keen cutting south-westerly wind, which seemed sufficient to blow his teeth down his throat. The ship looked as if made of glass, for every rope and spar was coated over with ice. The men were beating their hands to keep them warm; and when they moved about the deck they had to keep close to the bulwarks, and catch hold of belaying-pins, ropes, or stanchions, to prevent themselves from slipping away to leeward. The sea, as it broke on board, froze on the deck, till it became one mass of ice. Walter, who had thought only of smooth seas and summer gales, was little prepared for this sort of weather.

“Cheer up, my lad, never mind it; we shall be in summer again, and find it pretty hot too, when we round the Horn,” observed the first mate.

“I don’t mind it,” answered Walter, his teeth chattering. “Do you think it will last long?”

“That depends on the way the wind blows,” answered the first mate.

Dark seas rose up on every side, higher than he had ever seen them before; the foam driven aft in white sheets, their combing crests shining brilliantly as the sun burst forth from the driving clouds.

“Now you have seen enough of it; you had better go below,” said the mate. “One of those seas might break aboard and sweep you off the deck. As you can do nothing now, it is useless to expose your life to danger.”

Walter, who would have wished to remain had the wind been less cutting, thought the mate right, and obeyed him. He had been for some time in the cabin when the fourth mate came down.

“Come on deck, Walter,” he said, “and see something you have never before set eyes on.” Walter followed the mate up the companion-ladder.

As far as the eye could reach, the sea was of a dark-blue tint; the waves still high and foam-crested, sparkling in the rays of the sun, while at some distance on the larboard bow rose a vast mountain-island, its numerous pinnacles glittering in the sun like the finest alabaster, and its deep valleys thrown into the darkest shade. The summit of the mighty mass was covered with snow, and its centre of a deep indigo tint.

“What island is that?” asked Walter.

“It’s an island, though it’s afloat. That is an iceberg,” answered the mate. “It’s little less, I judge, than three miles in circumference, and is several hundred feet in height.”

The vast mass rose and fell in the water with a slow motion, while its higher points seemed to reach to the sky, and often to bend towards each other as if they were about to topple over. The waves furiously dashed against its base, breaking into masses of foam; while ever and anon thundering sounds, louder than any artillery, reached the ears of the voyagers, as from the mighty berg, cracking in all directions, huge pieces came tumbling down into the water. Above the thick fringe of white foam appeared an indigo tint, which grew lighter and lighter, till it shaded off from a dark-blue to the pile of pure snow which rested on the summit.

Walter could not resist the temptation of bringing Alice to see the strange and beautiful sight. Hurrying below, he wrapped her up in a warm cloak, and, calling Nub to his assistance, they brought her on deck.

“That is beautiful,” she exclaimed; “but how dreadful it would be to run against it in the dark!” she added, after a minute’s silence.

“We hope to keep too bright a lookout for anything of that sort,” said the mate; “and, happily, at night we know when we are approaching an iceberg by the peculiar coldness of the air and the white appearance which it always presents even in the darkest nights. However, there can be no doubt that many a stout ship has been cast away on such a berg as that; or on what is more dangerous still, a floating mass of sheet-ice just flush with the water.”

The mate would not allow Alice to remain long on deck for fear of her suffering from the cold, and Walter and Nub hurried her below. Walter was soon again on deck. The ship was passing the iceberg, leaving it a mile to leeward. As it drew over the quarter there was a cry from forward of “Ice ahead!” The captain was immediately called.

“Hard up with the helm!” he shouted; and the ship passed a huge mass of ice, such as the mate had before described, flush with the water. Had the ship struck against it, her fate would have been sealed. The sharpest eyes in the ship were kept on the lookout: one man on each bow, and another in the bunt of the fore-yard; the third mate forward, and one on each quarter. Two of the best hands were at the wheel; while the captain and first mate were moving about with their eyes everywhere. All knew that the slightest inattention might cause the destruction of the ship.

Hour after hour went by. No one spoke except those on the lookout or the officer in command, when the cry came from forward, “Ice on the weather bow,” “Another island ahead,” “Ice on the lee bow,” and so on. Evening at length approached. Walter for the first time became aware of the perilous position in which the ship was placed; yet his father stood calm and unmoved, as he had ever been, and not by look or gesture did he betray what he must have felt; indeed, he had too long been inured to peril of all sorts to be moved as those are who first experience it. Gradually, however, the sea began to go down and the wind to decrease, shifting more to the southward. A clear space appearing, the captain eagerly wore ship, and then hauling up on the other tack, stood to the southward, hoping to weather the icebergs among which he had before passed. The cold was as intense as before, but it could be better borne as hopes were entertained that the gale would abate, and that at length Cape Horn would be doubled.

That night, however, was one of the greatest anxiety; for, owing to the darkness, the ice-field could not be seen at any distance, and it might be impossible to escape running on it. Captain Tredeagle could therefore only commit himself and ship to the care of Heaven, and exert his utmost vigilance to avoid the surrounding dangers.

He and all on board breathed more freely when daylight returned, and the field of ice they had just weathered was seen over the quarter, with clear water ahead. A few more icebergs were passed; some near, shining brilliantly in the sun, and others appearing like clouds floating on the surface.

In two days more there was a cry of “Land on the starboard bow!” The ship rapidly neared it. The wind coming from the eastward, the reefs were shaken out of the topsails, the courses set, and she stood towards the west. The land became more and more distinct.

“Now,” said the first mate to Walter, “if Alice would like to see Cape Horn, bring her on deck. There it is, broad on our starboard beam.”

Alice quickly had on her cloak. “Is that Cape Horn?” she asked, pointing to a dark rugged headland which rose, scarcely a mile off, out of the water. “What a wild, barren spot! Can any human beings live there?”

“I have heard that some do,” answered the mate; “and what is very strange, that they manage to exist with little or no clothing to shield their bodies from the piercing winds! It’s a wonder they can stand it; but then they are savages who have been accustomed to the life since they were born, and know no better.”

Scarcely was the ship round Cape Horn when the wind moderated, and the sea went down till it was almost calm. The order was now given to get up the topgallant and royal-masts and rig out studding-sail-booms.

The mutineers had long been kept in irons, and some of the men declared that they were better off than themselves during the bitter weather to which they had been exposed; but the boatswain and the rest had more than once petitioned to be set free, promising to be obedient in the future. The captain, willing to try them, at length liberated them, and they were now doing duty as if nothing had happened, though the captain was too wise a man not to keep a watchful eye on them.

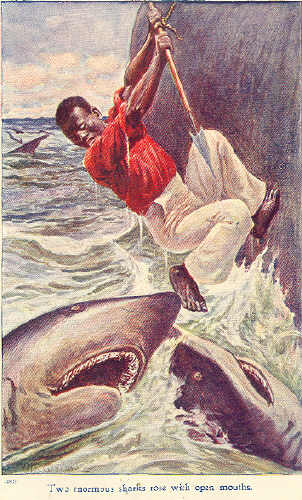

Alice, after being so long shut up in the cabin, was glad to be on deck as much as she could during the day, watching the various operations going on. The men were aloft rigging out studding-sail-booms, when, to her horror, she saw one of them fall from the fore-yard. Her instinctive cry was, “Save him! save him!”

“A man overboard!” shouted those who saw the accident. The ship was running rapidly before the wind, and under such circumstances considerable time elapsed before sail could be shortened and the ship hove-to. Preparations had in the meantime been made to lower a boat, and willing hands jumped into her, under the command of the second mate, to go to the rescue of the drowning man. The captain had kept an eye on the spot where he had fallen, so as to direct the boat in what direction to pull. Away dashed the hardy crew, straining every muscle to go to the rescue of their fellow-creature.

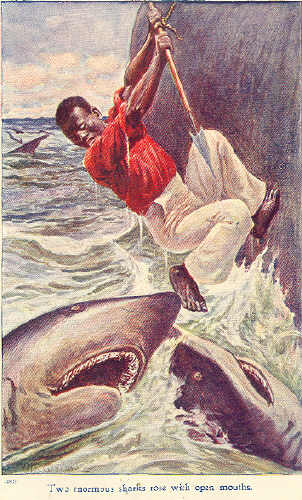

A moment before not a bird had been in sight, but just then a huge albatross was seen soaring high in the air. Its keen eye had caught sight of the unfortunate man. The boat dashed on, the mate and the crew shouting loudly in the hope of scaring off the bird; but heeding not their cries, downwards it flew with a fearful swoop. In vain the wretched man, who was a strong swimmer, endeavoured to defend himself with his hands; its sharp beak pierced his head, and in another instant he floated a lifeless corpse on the surface of the water.

“Who is he?” asked several voices.

“Tom Hulk,” answered the mate. “I caught sight of his face just as the bird struck him, and I hope I may never again see such a look of horror in the countenance of a fellow-creature as his presented.”

“It was a bad ending to a bad life,” said one of the men. “A greater villain never came to sea, and it’s the belief of some of us that he would have worked more mischief aboard before long.”

“That he would,” said another. “He was always jeering at the boatswain for his cowardice, and telling him he ought to act like a man. We knew pretty well what he meant by that.” Similar remarks were made by others; for all the men in the boat were honest and true, and had been among those who had at once sided with the captain and officers. Such are always found the most ready to go to the aid of a fellow-creature, and they had been the first to spring into the boat.

By this time they were nearly up to the body of the dead man. The albatross, on seeing them coming, had flown away. Just then, either some ravenous fish had seized it from below, or the body, no longer supported by the talons of the bird, lost its buoyancy, or from some other cause, it began to sink; and before the boatman could catch it with his boat-hook it had disappeared from sight, sinking down to the depths of the ocean, there to remain till the sea gives up its dead. When the mate returned on board, he did not fail to tell the captain what the men had said. “We must nevertheless keep a watchful eye on the boatswain and others who associated with him,” was the answer. “If Hulk, however, was the chief malcontent, we have little reason to fear them.”

The ship, with her lighter canvas set, was now making rapid progress towards the warm latitudes of the Pacific.

Chapter Three.

The “Champion” in the Pacific—First Whales Caught—Cutting in and Trying out—Various Places Visited—A Chase and Battle—A Prize Taken—The Prize parts Company—The Boats in chase of Whales—Walter’s Boat Destroyed—The Mate and Walter on the Wrecked Boat—A Fire Seen.

Walter had been rapidly gaining a knowledge of navigation and seamanship; he had now to learn something of the business of whale-catching. The Champion carried six boats, which were so built as to possess the greatest amount possible of buoyancy and stability as well as to be able to move swiftly. They were about twenty-seven feet long by four wide, and sharp at both ends, so that they could move both ways. At one end, considered the stem, was a strong, upright, rounded piece of wood, called the loggerhead; at the other, or bow, a deep groove for the purpose of allowing the harpoon-line to run through it.

The most experienced hands among the crew were busy in preparing the boats for active work. In each boat were stowed two lines, two hundred fathoms in length, coiled away in their respective tubs ready for use; four harpoons, and as many lances; a keg, containing several articles, among which were a lantern and tinder-box; three small flags, denominated whifts, for the purpose of inserting into a dead whale, when the boats might have to leave it in chase of others; and two cirougues—pieces of board of a square form with a handle in the centre, so that they could be secured to the end of the harpoon-line, to check the speed of the whale when running or sounding. Six men formed the crew of each boat: four for pulling, and two being officers; one called the boat-steerer, and the other the headsman.

Hitherto not a whale had been caught; but they were in hourly expectation of falling in with some. A sharp lookout was kept for them; a man for the purpose being placed at each masthead, while one of the officers took post on the fore-topgallant-yard. Day after day passed by, and still no whales were seen, till the men began to grumble at their ill-luck. Still they could not blame the captain, for he was doing the utmost in his power to fall in with them. The boatswain, however, took the opportunity of urging the rest of the crew that, since they could not find whales, they should go in search of an enemy, and try and pick up a prize. Tidy, as before, managed to hear what was going forward, and informed the captain. Notwithstanding this, he kept to his resolution to search for whales, and not to attack any of the enemy’s merchant-vessels, unless they should fall directly in his way, or come in chase of him. He trusted to the number of true men on board, and cared very little for the grumbling of the rest.

At length, one forenoon—the ship being only a few degrees south of the line, off the coast of Peru, as she was standing on under easy sail, the crew engaged in their various occupations, or moving listlessly about the decks overcome by the heat of the sun, which was very great, some grumbling, and nearly all out of spirits at the ill success of the voyage—the voice of one of the lookouts was heard shouting—

“There she spouts!”

The words acted like a talisman. In one moment, from the extreme of apathy, the crew were aroused into the utmost activity.

“Where away?” asked the captain in an animated tone.

“On the weather bow,” was the answer. “There again! there again!” came the cry from aloft, indicating that other whales were spouting in the same direction.

The crew were rushing with eager haste to the boats, each man to the one to which he belonged. The captain went away in one; the whale-master and two of the officers in the others,—for five only were lowered.

Walter and Alice were on deck, as eager as any one. Walter was about to slip into one of the boats when the first mate saw him.

“No, no, my lad; the danger is too great for you. The captain has not ordered you not to go; but I am right sure he would not allow it.”

Walter felt much disappointed, as he was very anxious to see the sport. He would not have called it sport for the poor whales, had he witnessed the mighty monsters writhing in agony as harpoons and spears were plunged into their bodies.

Away dashed the boats as fast as the hardy crews could lay their backs to the oars, the captain’s boat leading, while the ship was heading up towards them. All hands on deck watched their progress, till they looked mere specks on the ocean, although the backs of the whales and their heads could be seen above the surface as they spouted up jets of breath and spray.

Walter was surprised to see the third mate and surgeon with pistols in their belts and cutlasses by their sides, while Nub and Tidy and several other trustworthy men gathered aft, also with cutlasses, pistols, and muskets in their hands.

“Why are you all armed?” asked Walter. “I thought there was no fear of the mutineers playing any tricks.”

“We obey the captain’s orders,” answered Mr Lawrie.

“I thought that as Hulk is dead, and the boatswain is away, none of the rest would venture to mutiny.”

“The boatswain is cunning as well as daring, and while the captain and most of the other officers are away, he might come back and induce those he has won over to take possession of the ship,” answered the surgeon. “Your father is right to take precautions, though there may be but little chance of anything of the sort happening.”

“We must not tell Alice, or she may be alarmed,” observed Walter. “If she observes that you are armed, I will tell her that our father directed it should be so.”

The captain’s boat had in the meantime reached one of the whales, just at the moment that the monster, rising above water, had begun to spout. Two of the boats remained with him, while two others went in search of another whale. The captain’s boat dashing up rapidly towards the creature, he stepped to the bows, harpoon in hand. Hurling it with all his force, he fixed it deeply into the body of the whale; while one of the other boats coming up, a second harpoon was struck into its body.

“Back off, all!” was the cry, and the crews pulled away with might and main. The lines were run out to get to a distance from the now infuriated creature, which, seeing its foes, gave signs of making at them with open mouth; but they, pulling round towards the tail, avoided it; and the whale, no longer seeing them, lifting its flukes, dived far down into the depths of the ocean. The first lines being nearly run out, others were added on, which also rapidly ran out—a few fathoms only remaining. A third boat, which had been keeping pace with them, was now called up, that her lines might be added to those already out. Just then, however, the lines slackened, and the crews quickly hauled them in. It was a sign that the whale was once more coming to the surface. The mighty creature soon appeared, sending out from its spout-holes jets of blood and foam, and dyeing the water around with a ruddy hue. Again the boats approached, hauling themselves along by the lines made fast to its body, to inflict further wounds with the spears ready in the officers’ hands, when the whale again made towards them. It soon stopped, and began to lash the water furiously with its flukes, writhing and rolling in agony. Once more it ceased struggling, apparently exhausted; and the boats dashing up, more spears were struck into its body. The pain caused by the fresh wounds made it leap above the surface, and roll and lash the water with its flukes with greater violence than before, till the whole sea around was a mass of foam tinged with blood. The whale was in its “flurry.” These mighty exertions could not last long, and at length it lay an inert mass on the surface. Another whale was captured much in the same manner; when the boats, taking the creatures in tow, pulled towards the ship, the crews singing in chorus a song of triumph.

All on board had been eagerly looking out for their arrival. At length both were towed up, one being firmly secured by lashings to one side of the ship, and one to the other side, preparatory to the work of cutting in and trying out; that is, taking off the blubber or fat which surrounds the body, and boiling it in huge caldrons on deck.

Walter eagerly examined the monsters which had been brought alongside. They were sperm whales, which produce the oil so much valued for making candles. The head, as it was lifted out of the water, looked very much like the bottom end of a gigantic black bottle. This, the mate told him, was called the snout, or nose, and formed one-third of the whole length of the animal. At its junction with the body was a huge protuberance, which the mate called the “bunch” of the neck; immediately behind this was the thickest part of the body, which, from this point, gradually tapered off to the tail, or “small.” At this point was another protuberance, of a pyramidal form, called the “lump,” with several other small elevations, denominated the “ridge.” The end of the small was not thicker than the body of a man; it then expanded into the flukes, or, familiarly speaking, the tail,—the two flukes forming a triangular fin somewhat like the tail of a fish, but differing from it inasmuch as it was placed horizontally. The two flukes were about twelve feet or rather more in breadth, and six or seven in length. The whole animal was about eighty-four feet long, and the extreme breadth of the body between twelve and fourteen feet; thus the whole of the circumference did not exceed thirty-six feet. The mate said he had seldom seen whales larger. Though the upper part of the head was very broad, it decreased greatly below, so that it resembled somewhat the cutwater of a ship; thus, as the animal when moving along the surface raises its head out of the water, it is enabled to go at a great speed, the sharp lower part of the jaw performing the service of the stem of a ship. The mouth extended the whole length of the head, the lower jaw being very narrow and pointed,—no thicker in proportion than the lid of a box, supposing the box to be inverted. It had but a single blow-hole, about twelve inches in length, resembling a long S in shape. In the upper part of the head, the mate told him, there is a large triangular-shaped cavity called the “case,” which contains oil of great lightness, thus giving buoyancy to the enormous head. This oil is the spermaceti; and from the whale alongside, the mate said that probably no less than a ton, or upwards of ten large barrels of spermaceti, would be taken out. The throat, he asserted, was large enough to swallow a man, though the tongue was very small. The mouth was lined throughout with a pearly white membrane, which, when the whale lies below the surface with its lower jaw dropped down, attracts the unwary fish and other sea-creatures on which it feeds. When a number swim into the trap, it closes its jaw, and swallows the whole at a gulp.

“You see, Walter,” observed the mate, “the sperm whale differs very much in this respect from the Greenland whale, which has a remarkably small gullet, and a quantity of whalebone in its gills, through which it strains its food, so that nothing can get into its mouth which it cannot swallow. Now, the sperm whale has no whalebone in its jaws, and could manage to take in a fish of fifty pounds, or, for that matter, one of a hundred pounds, provided it had no sharp prickles on its back.

“Now, look at the eyes, how small they are, compared to the size of the animal. They have got eyelids, though; and they are placed in the most convenient spot, at the widest part of the head, so that it can see around it in every direction. Just behind the eyes are the openings of the ears; but they are very small,—not big enough to put in the tip of your little finger. Just astern of the mouth are the swimming paws; not that the whale makes much use of them, for it works itself on by its flukes, but they serve to balance the body, and assist the female in supporting her young.”

While Walter had been looking at the whales, the crew had been busy in preparing for the operation of “cutting in,” or taking off the blubber. Huge caldrons, or “try-pots,” had been got up on deck, with pans below them for holding the fire.

The first operation was to cut off the head; which being done, it was hauled astern and carefully secured with the snout downwards. Tackles being secured to the maintop, were brought to the windlass, when one of the crew being lowered on to the body of the whale with a huge hook in his hand, he fixed it into a hole cut for the purpose in the “blanket,” or outer covering, near the head. Others being lowered to assist him, they commenced cutting with sharp spades a strip between two and three feet broad, in a spiral direction round the body. This strip, as it was hoisted up by the tackles, caused the body to perform a rotatory motion, till the whole of the strip or “blanket-piece” was cut off to the flukes; which “blanket-piece,” by-the-by, the mate told Walter, was so called because it kept the whale warm. As soon as this was done, the shapeless mass, deprived of its fat, was allowed to float away, to become the prey of numberless seafowl and various fish. A hole being now cut into the case of the head, a bucket was fixed to a long pole and thrust down, and the valuable spermaceti bailed out till the case was emptied, when the head was let go, and, deprived of its buoyant property, quickly sank from view.

The next operation was to boil the spermaceti, and to stow it away in casks. The blanket-piece being cut up into small portions, they were thrown into the try-pots; the crisp pieces which remained after the oil was extracted, called “scraps,” serving for fuel. This last operation is called “trying out.”

Four days elapsed before both the carcasses were got rid of, and the oil stowed away in casks in the hold. Fortunately the weather remained calm, or the operation would have taken much longer. This was considered a very good beginning, and the captain hoped he should hear no more grumbling.

We must rapidly pass over the events of several weeks. Two ports in the northern part of Peru were visited, in order to dispose of to the inhabitants some of the goods brought out, and to obtain fresh provisions. It was a work of some risk, as the Champion would have to defend herself against any Spanish men-of-war which might fall in with her. After this, she touched at the volcanic-formed Galapagos Islands, situated on the line, at some distance from the continent. Here a number of huge tortoises were captured,—a welcome addition to the provisions on board. The ship remained some time in port, that the rigging might be set up, and that she might undergo several necessary repairs. From this place she sailed northward, touching at the Sandwich Islands,—then in almost as barbarous a condition as when discovered by Captain Cook. The inhabitants, however, had learned to respect their white visitors, and willingly brought them an abundance of fresh provisions. Captain Tredeagle was too wise not to take precautions against surprise. Some of the worst of the crew, however, grumbled greatly at not being allowed to visit the shore, and showed signs of mutinous intentions; their ringleader, as before, being the boatswain. By constant watchfulness and firmness the captain managed to prevent an actual outbreak; and having taken on board an ample supply of fresh provisions, and filled up with wood and water, he sailed for the south-west,—intending to try the fishing-grounds off the Kingsmill and Ellis’s groups, and thence to proceed to New Guinea and the adjacent islands.

After the Champion had been some weeks at sea, a sail was seen to the westward: whether a friend or a foe, could not be discovered; but she was apparently of no great size. The crew loudly insisted that chase should be given, and that she should be overhauled, many even of the better-disposed joining in the cry.

“I warn you, my men, that if a foe, though small she may be strongly armed, and you may have to fight hard for victory—not probably to be gained till several lives have been lost.”

“We want prize-money, and are ready to fight for it,” shouted the crew.

“I am willing to please you, though it is my belief that we shall be better off in the end if we keep to our proper calling. Even if we come off victorious, our crew will be weakened; and while we are repairing the damage we receive we might be filling our casks with oil.”

“One rich prize will be worth all the whales we can catch,” shouted the crew.

The captain yielded, and all sail was made in chase of the vessel in sight. The stranger soon discovered that she was pursued, and set all the canvas she could carry to escape.