The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mate of the Lily, by W. H. G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Mate of the Lily

Notes from Harry Musgrave's Log Book

Author: W. H. G. Kingston

Illustrator: unknown

Release Date: May 15, 2007 [EBook #21469]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MATE OF THE LILY ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

W H G Kingston

"The Mate of the Lily"

Chapter One.

Jack Radburn, mate of the “Lily,” was as prime a seaman as ever broke biscuit. Brave, generous, and true, so said all the crew, as did also Captain Haiselden, with whom he had sailed since he had first been to sea. Yet so modest and gentle was he on shore that, in spite of his broad shoulders and sun-burnt brow, landsmen were apt to declare that “butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth.”

A finer brig than the “Lily” never sailed from the port of London. Well built and well found—many a successful voyage had she made to far distant seas. Jack Radburn might have got command of a larger craft, but Captain Haiselden, who had nursed him through a fever caught on the coast of Africa, and whose life on another occasion he had saved, thus closely cementing their friendship, begged him to remain with him for yet another voyage, likely to be the most adventurous they had ever yet undertaken.

Jack Radburn, who was my uncle, stayed when on shore—not often many weeks together—with his sister, Mrs Musgrave, my mother.

Though he was my uncle, I have spoken of him as Jack Radburn, mate of the “Lily,” as did everybody else; indeed, he was, I may say, as well known as the captain himself. My mother, who was the daughter of a clergyman long since dead, had not many acquaintances. She had been left by my grandfather with little or nothing to depend upon, when her brother introduced to her my father, then first mate of the ship to which he belonged.

Her greatest friend was Grace Bingley, who lived with her mother, wife of a ship-master, a few doors off from us.

Uncle Jack had consequently seen much of Grace Bingley, and had given her the whole of his warm honest heart, nor was it surprising that he had received hers in return, and pretty tightly he held it too. Even my mother acknowledged that she was worthy of him, for a sweeter or more right-minded girl was not, far or near, to be found.

Some four years before the time of which I am now speaking, my father sailed in command of a fine ship, the “Amphion,” for the Eastern seas. The time we had expected him to return had long passed away. My mother did not, however, give up all expectation of seeing him, but day after day and week after week we looked for him in vain. The owners at last wrote word that they feared the ship had been lost in a typhoon, but yet it was possible that she might have been cast away on some uninhabited island from whence the crew could not effect their escape. My mother therefore still hoped on and endeavoured to eke out her means so as to retain her house that my father might find a home should he return.

I was setting off with Uncle Jack for the “Lily,” which was undergoing a thorough repair, and he seldom failed to pay her one or two visits in the day to see how things were going on, when two seamen came rolling up the street towards us in sailor fashion, and looking, it seemed to me, as if they had been drinking, though they may not have been exactly drunk. As they approached one nudged the other, and, looking at Uncle Jack, exchanged a few words.

They would have passed us, when he, having noticed this, hailed them—

“What cheer, my hearties, have we ever sailed together?”

“Can’t say exactly, sir, for we’ve knocked about at sea so long that it’s hard to mind all the officers we’ve served under. But now I looks at you, sir, I think you used to come aboard the ‘Amphion’ before she left Old England. We heard say you were the captain’s brother.”

“The ‘Amphion!’” exclaimed Uncle Jack, eagerly, looking hard at the men. “Can you give me any news of her?”

“Aye, sir, but it’s bad news.”

“Out with it, whatever it is,” exclaimed Uncle Jack, fixing his eyes on the man, to judge whether he spoke the truth.

“It’s a matter of over four years gone by when we sailed for the Eastern seas. We had been knocking about in them parts for some months, when we were caught in a regular hurricane, which carried away our topmasts and mainyard, and did other damage. At the same time we sprang a leak, and had to keep the pumps going without a moment’s rest. When night came on, and a terrible dark night it was, sir, matters grew worse and worse, not a hope but that the ship would go down, though we well-nigh worked our arms off to keep her afloat. Howsomedever before long, she struck on a reef, though she hadn’t been thrashing away on it three minutes when she drove off, and the water came rushing in like a mill stream. ‘Out boats,’ was the cry. Bill here and I, with three others, got into the jolly-boat, but before another soul could spring aboard her she drifted away from the ship. We felt about, and found a lugsail and an oar. To go back was more than we could do, and it’s our belief that scarcely had we left her than the ship went down. As our only chance of keeping the boat afloat was to run before the sea, we stepped the mast and set the lug close reefed, hoping to come upon some land or other. When morning broke no land was in sight. We thought we saw what looked like it far away on the starboard quarter, but we could only go where the wind drove us. Three days we scudded on without a drop of water or bit of food to put into our mouths. I speaks the truth, Bill, don’t I?”

“Ay, ay!” said Bill, looking as if he did not even like to think of that time; “you does, mate.”

“Go on,” said Uncle Jack.

“Well, first one went mad and jumped overboard, then another died, then another, and I thought that Bill would die too, when down came a shower, and with the help of our sail we filled an empty breaker which we had in the boat. Then we knocked down a bird which came near us, and that gave us a little more strength. Then three flying-fish came aboard, which kept us for three days more, and after that we caught a small shark, but the water came to an end, and we were both so well-nigh done for that neither Bill nor I could hold an oar to steer by, nor knew where we were going—I speaks the truth, don’t I, Bill?”

“I suppose you does, but I don’t mind much what happened then. I was too bad,” said Bill.

“Well, as I was a-saying, I thought it was all over with us, when a ship hove in sight and took us aboard. She was a foreign craft, and not a word of what her people said could we make out, any more than they could understand us. We were not over well treated, so we ran from her the first place we touched at; and after knocking about for a long spell in them South Sea islands among the savages, in one craft or another, we got home at last. What I’ve told you is the blessed truth; ain’t it, Bill?”

Bill grunted his assent to this assertion; he evidently was not a man of words.

My uncle cross-questioned the men, but could get nothing more out of either of them. Whether or not he was perfectly satisfied I could not tell. Still it seemed too probable that the “Amphion,” with my father and all hands, was lost.

Having lodged the seamen so as to find them again, my uncle returned with me to my mother. She was prepared for the information he had to give her. She had for some time been persuaded of what everybody else believed, that my father was lost, and she now knew herself to be a widow. It was a severe shock to her notwithstanding. She looked at me and my five brothers and sisters, all younger than I was.

“What shall I do with these fatherless children?” she asked, while her eyes filled with tears, thinking more of us than of herself; “my means are almost exhausted, for my dear husband saved but little, and I shall not have the wherewithall to pay the rent of this house, much less their food and clothing.”

“God has promised to provide for the fatherless and widows,” answered Uncle Jack; “while I have a shilling in my pocket it shall be yours, Mary. Harry, too, is able to support himself. We’ll take him aboard the ‘Lily,’ and soon make a prime seaman of him.”

My mother looked at me, grieving at the thought that I must so soon be taken from her. Then other thoughts came into her mind.

“But you, my dear Jack, require all the means you possess for yourself. Grace has promised to become yours whenever you desire it.”

“I know that,” answered Uncle Jack. “I prize her love, but we are both young and can wait, and true as mine is for her it must not overcome my duty to you and yours. Captain Haiselden talks of some day going to live on shore, when he will give up charge of the ‘Lily’ to me, or I may obtain a larger craft and shall make enough for Grace, and you, and myself, I hope. At all events, my dear sister, you and the children must not starve, and we shall have Harry here making his fortune. So cheer up, Mary, and trust in God.”

“I do, Jack, I do,” she answered, taking his hands, while the tears still flowed down her pale cheeks. “Harry will do his duty, I know, and some day be able to help me, and I must try to do what I can for myself, though I fear it will be but little.”

“You have friends who will be glad to lend you a helping hand,” said Uncle Jack, who judged of others by himself. “We may have, I trust, a successful voyage, and all will go well, Mary.”

Much more he said to the same effect. My mother appeared comforted, at all events she grew calm, and as Captain Haiselden consented to take me on board as an apprentice, she set herself busily to work to prepare my outfit, while my sister Mary, who was next to me, and my two younger brothers were sent to school, and Grace Bingley came in every day to assist her in her task.

How industriously Grace sat working away with her needle, every now and then jumping up to prevent Frank or Sally from getting into mischief! Some of the larger garments were certainly not for me. My mother had promised to overhaul Uncle Jack’s wardrobe and supply what was wanting, according to a list he gave her. I should like to describe Grace as she sat in the bay window opposite my mother with the work-table near them, but it will suffice to say that she was young, fair, and pretty, with eyes that seemed to have borrowed their colour from the sky. My mother had assumed the widow’s cap, and might from her clear complexion, and her brown hair braided across her brow, have been taken for Grace’s elder sister. Though the heart of Grace must have been sad enough I suspect, she talked cheerfully, endeavouring to distract my mother’s mind from the thoughts of the past as well as the approaching parting from me. I came in occasionally and found the two sitting as I have described, but I was generally on board the brig with Uncle Jack, assisting in fitting her out, and thus got initiated into many of my duties before I ever went to sea. The captain often came on board during the evening to see how we were getting on, but during the day he was mostly engaged in looking out for freight in addition to the cargo he intended to ship on his own account. He was just the man the crew were willing to serve under, his countenance exhibiting sense and determination, and a kindly spirit beaming from his eyes; his hair grizzled rather by weather than by years; his figure, of moderate height, broad and well knit, betokening strength and activity.

We were to sail for Singapore, after which we were to proceed eastward to trade with the various islands in that direction.

We expected to have the “Lily” ready for sea in about a week, when just before this time Captain Bingley, who had been long absent in command of the ship “Iris” of some four hundred tons, returned home. I was at my mother’s one evening when Uncle Jack, with Grace Bingley, came in. She looked, I thought, somewhat out of spirits. My mother thought so too, and asked her the cause. She hesitated for a moment as if to master her feelings, and then said—

“It is, I have no doubt, for the best, and father wishes it. Mother and I are to accompany him on his next voyage round Cape Horn and up the western coast of America, then across the Pacific to Java, and so round the world. I cannot refuse to go, and of course we should both like to see strange lands, as well as being with father, but I had hoped to be able to remain with you, Mary, and you know how happy I should have been in doing so.”

My poor mother looked much distressed. “Of course, if your father wishes you to go you have no choice, but I shall miss you greatly.” She could scarcely restrain her tears as she spoke.

Uncle Jack became very grave as he heard what Grace said.

“You sail round the world! Has your father positively determined on this?” he asked.

I guessed his thoughts; he was ready enough to encounter all the risks and perils of the sea himself, but he was very unwilling that Grace should be exposed to them. What if the ship should be wrecked! What if sickness should break out on board, or a mutiny occur, or should she be captured by an enemy! He dreaded dangers for Grace which he did not take into a moment’s consideration in regard to himself, but he strove not to allow her to perceive his anxiety.

“Father is not a person, as you well know, to be turned from his purpose,” she answered, trying to smile. “Mother has promised to go, and I cannot let her go without me. She or father might fall ill, for he is not so strong as he was, and I ought to be ready to nurse them, and I hope, my dear Jack, that we shall be back as soon as you are, though my chief anxiety is leaving Mary; and Harry also away. Perhaps, too, we may meet; my father doesn’t know exactly where we shall go after we leave the China seas; it must depend upon the freight obtained.”

“It is a wide region, and I was hoping that I could picture you when I was away, safe at home,” answered Uncle Jack, but he refrained from saying more. He was unwilling to create any anxiety in Grace’s mind. He certainly, however, looked more distressed than any of the party.

After this Grace could be less at our house than usual, as she had to help her mother in preparing for their voyage. The “Iris,” she told us, was to be got ready for sea with all despatch. Uncle Jack and I one evening went on board to have a look at the ship that, as he observed, he might at least know what sort of a craft Grace was sailing in. The cabins were comfortably fitted up and well suited for the accommodation of the captain’s wife and daughter, as well as for a few other passengers. I asked him what he thought of the ship.

“She’s a fine enough vessel, but I can judge better of her if she were loaded, and I should like to know what sort of a crew she has,” he answered. “Captain Bingley is a good seaman, and I respect him as Grace’s father; but he wants to make money, and he may be tempted to overload his ship, or visit dangerous places to obtain freight.”

I did not see the parting between Uncle Jack and Grace, as I went on board the “Lily” the night before we sailed. I had already wished good-bye to my dear mother and all the young ones, and as she had to look after them, she could not come to see us off. I know very well what she must have felt, and I heartily wished, when the moment came for leaving, that I could have remained to comfort and protect her. My going away must have brought back to her recollection with painful vividness the time when my kind father last sailed I suspect she thought that she might never see me again; still she knew that I must work for my livelihood, as I did myself, and I was going to begin the profession I had chosen, and for which I had long had a desire. For dangers and hardships I was ready, fully persuaded that, though I might encounter, I should get through them.

We were at sea at last, running down channel with a fair wind. Uncle Jack had had no difficulty in obtaining a good crew, for when he could find them, he picked up old shipmates, who were always glad to sail with him. He had promised Timothy Howlett and Bill Trinder to look them up, and they, having spent the last shilling in their pockets, were glad to ship on board, he hoping that they having been before in those seas might be useful. James Ling was second mate and Sam Crowfoot boatswain, making up the complement of our officers, besides which there was our supercargo, Edward Blyth, a young but very intelligent man, who had already made a voyage to the Eastern seas, understood Dutch as well as the Malay languages, and was thus able to act as interpreter at many of the places where we were going. He was well informed on many subjects also, and possessed a good knowledge of natural history. I must not forget “Little Jem,” the smallest boy on board. Instead of being knocked about and bullied, he was somewhat of a favourite among the men, with whom, however, he was pretty free and easy in his way of talking; but they liked him all the better for that. To the officers he was always respectful, well-mannered, and, being very intelligent and active, was consequently a favourite with them.

We had on board four carronades and a long gun, as where we were going it was necessary to have the means of defence, but they were stowed below during the first part of the voyage. We had also a supply of cutlasses, pistols, and boarding pikes for all hands, which ornamented the fore bulk head of the main cabin, though occasionally taken down to be cleaned and polished, so that they might be of use when wanted.

Uncle Jack took great pains to teach me navigation, and, as I had learnt mathematics at school, I was soon able to take a good observation with my sextant and to work out the calculations correctly. A knowledge of seamanship I found was not to be obtained so rapidly, though Crowfoot, the boatswain, was always ready to give me instruction and express his opinion how a vessel ought to be handled under all possible circumstances, but a large amount of presence of mind, and what may be called invention, has to be exercised on numerous occasions, for which no rules can be laid down.

“Now, Harry, you see wits is what a sailor wants. You’ve got learning, and with learning you can pick up navigation pretty smartly. I haven’t got the learning, and so I can’t get a mate’s certificate; but I’ve got the wits and have been many a long year at sea, and so I am fit for a boatswain, and can take charge of a watch with any man,” he remarked.

The wind favouring us after we left the chops of the channel, we ran into the north-east trades, which took us to within two or three degrees of the equator; and after that we had the calms and heavy rains which are invariably met with, and were sometimes wet to the skin, at others roasted in the hot sun. No one suffered, however, and after getting out of them, we picked up a fine south-east trade wind. This carried us down to twenty-six degrees south. The meridian of the Cape was passed about the fiftieth day after leaving the Lizard. We ran down our easting on parallel forty south. The brig was going about eight knots before the wind, when one morning there was a cry of “Man overboard!”

Uncle Jack, who had been below, sprang up the companion-ladder, and, looking over the side, saw that it was little Jem, who had fallen from the fore yardarm. Ordering all hands to brace up the yards and the man at the wheel to put down the helm, while he threw off his jacket, he leaped overboard and struck out for the boy.

“Heave a grating here!” he shouted. “Harry, don’t come,” and I, who was on the point of following, did as he directed.

The captain was on deck a moment afterwards and made ready to lower the lee quarter boat. Every one on board, as may be supposed, was busy pulling and hauling and bracing up the yards and backing the main topsail, so that there was no time to see what had become of the first mate and boy, but the captain had his eye upon them. It was sharp work, for we knew the lives of our fellow-creatures depended upon our exertions. I wished that I had possessed the strength of two men. As soon as the brig was hove to, I took one glance to windward. I thought I saw Uncle Jack and the boy, but I also saw what filled me with alarm, a huge albatross flying above, apparently about to swoop down upon them. It was but a glance, for I sprang over to the other side to jump into the boat, eager to be among those going to save them. The second mate was already in the boat, three other hands following. As soon as we got under the stern of the brig, we saw the captain standing aft, pointing in the direction we were to steer. The second mate, I thought, appeared very cool.

“Give way, lads,” he shouted. “We shall be up to them before that bird strikes either of them on the head, for it seems that is what he is trying to do.”

A long rolling sea was running, and only when we were at the top of a wave were those ahead of us visible to the mate, who stood up every now and then the better to watch them.

“There’s that bird making another swoop!” he exclaimed, and soon afterwards he cried out, “He has risen again. Give way, lads! He may not have struck both.”

I did give way as may be supposed. If one had been struck, might it not have been Uncle Jack!

“He has hold of the grating at last!” cried the mate. “I see him waving his hand. There comes the bird again!”

Once more my heart sank within me. I could not turn round to look, or I might have missed my stroke. The boat seemed to be making but fearfully slow progress as I watched the brig rising to the seas, and as she pitched into them, throwing the spray over her bows. There stood the captain pointing with his hand, as if to encourage us to persevere. On and on we pulled, I expecting every moment to hear the mate exclaim that the albatross had made a fatal swoop. At last I heard a voice, though a very weak one, cry, “Take the boy in first.”

I knew it was that of Uncle Jack; I saw him lift little Jem up while he held on to the gunwale. The two men in the bow then hauled him in, and next the grating on which he had supported himself.

Uncle Jack sank down utterly exhausted. We passed the boy aft. He seemed to be dead. We then dragged the first mate into the stern-sheets, but could not attend to him, for we were compelled to keep our oars going to get the boat round as soon as possible. Uncle Jack lay without moving. I saw that one of his shoes was off. He presently came to. His first thought was for the boy, whose hands and chest he began to chafe as well as his weakness would allow.

The second mate, I thought, might have spared a hand to help him, but he looked on, it seemed to me, with indifference, jealous that the first mate should have behaved so gallantly, or—although I tried to put the thought from me—angry that he had escaped. We pulled away until rounding the stern of the brig, we got alongside, when a cheer burst from the crew as they saw that we had the first mate and little Jem safe. Eager hands stood by to lift them or board, for even Uncle Jack was still too weak to help himself. While the boat was being hoisted up the captain directed Mr Blyth and me to carry the boy into his own cabin, he and two of the men following with the first mate, who was placed in his own berth. We, in the meantime, had got the boy’s clothes off him and had wrapped him up in a dry blanket, while we kept chafing his chest, arms, and feet until he breathed freely. He soon returned to consciousness, and looking about him was much surprised to find where he was.

“Where’s Mr Radburn? Oh, sir, have you got him safe?” was his first question.

He is all right, my lad.

“It’s that bird, sir; it’s that bird, sir! Oh, save me from it!” he continued crying out.

“The bird won’t hurt you, and Mr Radburn is safe in his cabin, I hope,” answered Mr Blyth, in a kind voice.

As soon as I could I went to see how the first mate was getting on. He had swallowed a cup of hot tea, for we were just going to breakfast, and this had greatly restored him; and though the captain had advised him to be still, he was putting on his dry clothes, and in a short time joined us at table.

Uncle Jack said that he had felt the tips of the bird’s wing pass over his head each time that it swooped down, but that he had taken off his shoe and attempted to defend himself, until the bird had seized upon it and carried it off. “It will find the shoe a tough morsel to digest,” he added, laughing; “but truly I have reason to thank God that it did not strike either little Jem or me with its sharp beak, and I was so exhausted that if the boat hadn’t come up when she did, I should have been unable to keep him longer at bay.”

Either Mr Blyth or I stayed by “Little Jem” all day, the captain and first mate every now and then looking in. By night he was well enough to be removed to his own berth forward, where the men promised to look after him.

The captain and Mr Blyth complimented the first mate on his gallant conduct, but he seemed to think he had done nothing out of the way.

“There is one thing a man should consider before he jumps overboard, and that is, whether there is too much sea on to allow of a boat being lowered, for if there is he will not only lose his own life, but cause the loss of others,” observed the captain. “It is a hard matter, however, to lay down a rule. Still it is very certain that we should do our best to save the lives of our fellow-creatures.”

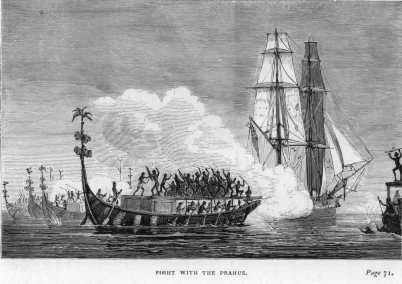

We once sighted an island, which I believe was one of the Crozet group. In rather over three months we entered the Straits of Sunda, when, as we were approaching shores the inhabitants of which were addicted to piracy, we got up our guns from the hold and mounted them, and overhauled our firearms. Before long we had a good chance of requiring them, for when running through the Straits of Banca, between that island and Sumatra—while nearly becalmed—we made out three large prahus full of people, pulling towards us. Whether their intentions were friendly or the reverse we could not ascertain, but we certainly did not like their looks; a breeze, however, sprang up and we stood on our course. Soon afterwards we came in sight of the fine town of Singapore, founded in 1819 by Sir Stamford Raffles, who made it a free port. At that period a wretched village stood on its site, the neighbouring harbour being the rendezvous only of a few trading prahus. It is now a magnificent city, and upwards of a thousand square-rigged vessels anchor annually in the roads. On the hills beyond it can be seen the residences of the merchants, surrounded by plantations of spice-trees, while excellent roads with bridges over the streams run in all directions.

Besides English churches and chapels, there are Chinese Joss houses, Hindoo temples, and Mohammedan mosques, while large numbers of Chinese and Malay cottages form the suburbs. The Chinese are here seen in considerable numbers, being the most industrious part of the population, and include many wealthy merchants. There are Klings from Western India; Arabs, chiefly shop-keepers; Parsee merchants; Bengalese, mostly grooms and washmen; Japanese sailors, many of whom are also domestic servants; Portuguese clerks, and traders from Celebes, Boli, and other islands of the vast archipelago.

Having discharged part of our cargo, we took on board such articles as we heard were in demand among the natives with whom we hoped to open up a trade. In the interval Mr Blyth proposed that he and I should make a trip into the interior. We could not, however, go far, for the island is only about twenty-seven miles in length and eleven in breadth. We were particularly warned not to venture into the forest, as we should run a great risk of being carried off by tigers, large numbers of which infest the jungles, and, it is said, kill a Chinaman a day, they being the chief workers in the plantations. The captain gave me leave to accompany the supercargo, and we hired two small Timor ponies for our excursion. We had not got far when we met a party of men carrying between them the skin of a large tiger, propped up on a sort of platform formed of bamboos, looking very fierce, with its mouth open and tail on end. They were on their way to the government office to receive the reward given for every animal killed, just as payment was made in former years in England for the head of each wolf put out of existence. The animal had been caught in a pit covered over with sticks and leaves, the usual mode in which they are trapped. We kept a sharp look-out, with our pistols ready to shoot a tiger should one attack us. We heard several roars, and a huge beast crossed the road in front of us. After this we did not feel altogether comfortable, expecting every moment that it would spring out from the jungle and carry off one or both of us.

We returned to the city, however, without an actual encounter. I cannot stop further to describe this interesting place. In a few days we sailed for George Town on the eastern side of the island of Penang, the seat of Government of the British possessions in the Straits of Malacca, Penang is larger than Singapore, a considerable portion being rocky, and those most industrious of mortals, the Chinese, form the chief part of the population. After discharging the cargo we had brought from England for this place, we again sailed, steering through the straits of Singapore for the eastward.

Chapter Two.

We were bound for Kuching, the capital town of the province of Sarawak in Borneo, where Mr Brooke, who went out in 1839 in his yacht the “Royalist,” had, by his judgment and intrepidity, established a thriving community, of which he had been appointed the chief or rajah. The captain and supercargo had mapped out our future course. This was to be along the north coast of Borneo, through the Sooloo archipelago, across the sea of Celebes to the coast of Papua, and thence through the Banda sea to Timor, whence we were to return home along the southern coast of Java. It took two days to get up to Kuching, the capital of the province of Sarawak, after we had entered the mouth of the river on the banks of which it stands. On either side were hills covered with jungle, with here and there clearings where the peaceably-disposed natives had established themselves.

Mr Blyth and I had an opportunity, in company with a gentleman who was making a shooting expedition, of taking a trip into the interior. I wish that I could describe the magnificent vegetation, the gigantic trees, and the curious animals we saw. One of the most curious was the mias. What is a mias? will be asked. It is the native name of the far-famed ourang-outang, the principal wild inhabitants of this region. We were proceeding through the forest, with our guns, when one of our Dyak companions came running up to tell us that he had seen a mias, and that if we made haste we might be in time to shoot it.

We hurried on, the Dyak leading the way, until we entered a thick jungle. He pointed to a tree far above our heads. Upon looking up we saw a great hairy body and a huge black face gazing down upon us, as if wondering what strange creatures we could be. Mr Blyth and our friend fired; whether they had hit the mias we could not tell, but it began to move away among the higher branches at a rapid rate. Led by the Dyak we followed, when again we caught sight of it on the branch of a tree, where it remained for a minute or more. By this time we were joined by several other Dyaks, whose shouts appeared to frighten the ourang-outang, which tried to get along the edge of the forest by some lower trees, keeping, however, beyond the reach of our rifles. The Dyaks, flourishing their weapons, rushed on ahead of us hoping to have the honour of killing the monster. We had lost sight of them for a few seconds, when we heard fearful shrieks and shouts, and running forward, we saw that the mias had either voluntarily descended the tree, or had fallen to the ground, and had rushed at one of the natives, who, unable to escape, was standing with his spear ready to defend himself. We were afraid in attempting to kill the mias that we might shoot the native, when, just as the creature was about to seize the man with its mouth and formidable claws, our friend fired and the animal fell, shot through the heart.

On measuring the mias, from the top of its head to its heel, we found that it was four feet two inches long, while its outstretched arms measured seven feet three inches across. Its head and body were of the size of a man’s, the legs being very short in proportion. This mias was of the larger species, many being under four feet high, and some of the females not more than three feet six inches.

We saw a frog, with large web feet and inflated body, fly from the top of a tall tree. It was about four inches long, the back and limbs of a shining black hue, with yellow beneath. Our friend had promised us a rich treat at supper, and he produced a fruit which he told us was the Durian. It was of the size of a large cocoa-nut, the husk of a green colour, and covered all over with short stout spines. It grows on a lofty tree, somewhat resembling the elm. It falls immediately it is ripe; but the outer rind is so tough that it is never broken by the fall. There are marks which show where it may be divided into five portions; these are of a satin whiteness, and each one is filled with an oval mass of cream-coloured pulp, in which are two or three seeds about the size of chestnuts. This pulp is the eatable part. Its consistency is that of a rich custard. As to describing its taste, that is more than I can do. It is not acid, nor is it sweet, nor juicy, but yet, as we ate it, we agreed that none of these qualities were wanting, and that it was the most delicious fruit we had ever met with. The Mangosteen, which comes to perfection in Borneo, is another splendid fruit of a sub-acid flavour, better known than the Durian. But I must not stop to give long descriptions either of the animals or fruits we met with. Blyth and I had to return, as we could not long be absent from the brig.

Often had the now smiling plantations through which we passed been plundered by blood-thirsty pirates, and the heads of their inhabitants carried off. A visitor on board gave us dreadful accounts of the atrocities committed by the pirates in the seas through which we were to sail.

“We will show them that they had better not attack us,” observed Captain Haiselden, pointing to our guns. “The ‘Lily’ is a match for all their fleets put together.”

“Not if the ‘Lily’ is caught at anchor or in a calm; you may then find that they are too much for her,” was the answer. “These prahus often carry sixty men or more, with guns and small arms, and you would find it no easy matter, were you to be attacked, to beat them off.”

“They’ll not stop us; but we will keep a bright look-out for them,” answered Captain Haiselden.

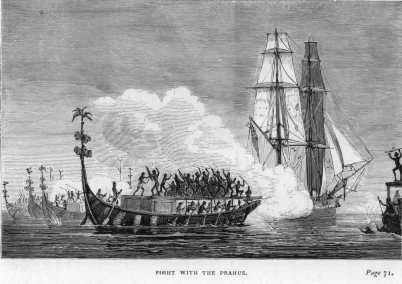

We had a fine breeze as we ran along the coast of Borneo, and although we saw in the distance not a few long suspicious-looking prahus, we sailed too fast for them to overtake us. We saw one of these crafts lately captured, which had been brought to Kuching. She was about ninety feet in length, and of proportionate beam. In the bow she carried a long twelve-pounder gun, and six swivels on each broadside, besides which she had thirty or forty rifles or muskets on board, and other small arms, swords, pistols, and pikes. She pulled eighty oars in two tiers, and had had a crew of a hundred men. Over the rowers, extending the whole length of the vessel, was a light flat roof composed of fine strips of bamboo covered with matting, which, notwithstanding its lightness, was very strong. This deck served as a platform, on which the fighting men stand to fire their muskets or hurl their spears, while the rowers below them sit cross-legged on a shelf projecting outwards from the bends of the vessel.

The Dyak piratical vessels are called “Bang Kongs.” Although they are a hundred feet in length by ten in beam, they draw but little water, and are both light and faster than the Malay prahus. They have long overhanging stems and sterns, are propelled by eighty paddles, and are as swift as any craft afloat. Some mount a few small swivels, and each carries a certain number of Malays armed with muskets, besides which they have their regular crew of Dyaks, whose weapons are spears. From drawing so little water they are much dreaded, as they can run up the shallowest river, when their savage crews, landing, commit most horrible atrocities on the inhabitants living near the banks.

We had left Sarawak about three days, when it fell almost calm; still the vessel was making some way through the water. I was stationed forward to keep a look-out. As I turned my eyes around the horizon ahead I fancied that I could distinguish what appeared just like a small number of black dots rising above it. Before I sang out, however, asking the boatswain, who had come on the forecastle to take my place, I ran aloft, with a spy-glass slung to my back, to satisfy myself whether I was right or not. Reaching the fore-topmast cross-trees, I took a steady look in the direction I had seen the dots I was convinced that they were prahus, though whether large or small I could not be certain, pulling towards the coast of Borneo. I counted six altogether. On my return I went aft to report what I had seen to the captain.

“We will keep away a little, and pass astern of them. They may possibly not have seen us, or if they have, they’ll think it prudent not to come nearer.”

The first mate on hearing my report also went aloft, and on his return corroborated it. I confess that I felt somewhat uneasy at the sight of these vessels. They might be peaceable traders, but they might be pirates, who, should they find us becalmed, might try to obtain a rich booty such as our vessel would afford them.

I was surprised that my uncle and the captain took the matter so coolly. I watched the strangers until they were no longer to be seen from the deck. After some time we again hauled up and stood on our course to the eastward. Later in the day, on going aloft, I again caught sight of the prahus, as I believed them to be, but as they were very low in the water, they were scarcely visible to any but a sharp pair of eyes, such as I possessed.

In the afternoon I was taking a turn on deck with Mr Blyth, the captain and first mate being below, and the third mate in charge of the brig, when I observed a small cloud coming up on the port bow.

“There’s wind in that cloud, I’m sure,” I said to my companion. “I’ll point it out to the mate, for he doesn’t seem to see it.” I did so.

“That’s all you know about the matter, youngster,” he answered in a scornful tone.

“We shall be taken aback if we don’t shorten sail, and I don’t know what will happen,” I remarked to Blyth, when I rejoined him. “I have a good mind to run down and tell the first mate.”

Scarcely had I said this, and was about to spring down the companion-hatch, when Mr Ling sang out—

“Ready, about ship!”

The helm was put down, the yards were being braced round, and the brig’s head brought to the wind, when, as I looked up, I saw every sail aback. At that moment I heard the voice of the captain, who had just come on deck, shouting, “All hands shorten sail and save ship,” but the order was given too late. The squall I had seen coming up just then struck her, and in one moment, with a fearful crash, the main-mast fell. I should have been crushed had I not by tumbling head first down the hatchway avoided it; the next instant the foremast followed, and the bob-stays giving way, dragged the bowsprit on board. The moment the crash was heard the first mate sprang up the companion-ladder shooting me with his head on deck again. I looked round expecting to see many of the crew killed. My eye first fell on Mr Blyth, who was holding on by a stanchion, and apparently uninjured. The second mate, too, excepting a blow on the shoulder, had escaped, while of the crew, though they looked very much astonished, not a man was seriously hurt. Several of them, indeed, who had been below, had only rushed up on hearing the crash of the falling masts. They were gazing with open eyes on the utterly dismantled state of the brig, lately so taunt and trim, waiting for the captain’s orders what to do. But what had become of him? He was nowhere to be seen. At first I feared that he had been knocked overboard, but as I looked about I caught sight of a man’s legs sticking out from under a mass of sails and rigging. Knowing that it must be the captain, I ran to drag him out, calling on Blyth to assist me.

We soon got him free, but he did not move; we feared that he was dead. At Blyth’s suggestion, with the help of two of the men, we carried him below and placed him on his bed.

Greatly to our relief he in a short time began to show signs of life.

“He will soon come round,” said Blyth; “I will watch him, so do you go on deck, Harry, where I am sure you will be wanted, and tell the first mate how he is getting on.”

I hurried up, and reported the captain’s state to my uncle.

“Thank heaven!” he exclaimed; “I had no wish to take his place, but I must attend to the work before us—we have plenty of it.”

He then turned round to the bewildered crew—

“We must first haul in all the gear trailing overboard, my lads, and then get up jury-masts,” he shouted out, hurrying along the deck to examine the state of things forward.

Having got the spars and rigging on board, we commenced unbending the sails and unreefing and coiling away the ropes. As we got the yards free we stowed them amidships, that we might use those of them which were most suitable for jury-masts. The wind had in the meantime been increasing, and the sea was getting up. All we could do was to keep the vessel before it, while we laboured hard to rig a jury-mast forward that we might, as soon as possible, get sail on the brig to steady her. She was now rolling fearfully, and it was with difficulty even that we could keep our feet. I looked out more than once in the direction where I had seen the prahus, fearing that should they discover our present defenceless condition they might attack us, for although we might fight our guns it would be at a great disadvantage.

The gale blew harder and harder. I had not heard for what port the first mate intended to steer, though I of course knew that he would endeavour to make one as soon as possible, either Sarawak or Singapore; but as the gale was at present blowing us away from both of them until we could get up jury-masts and haul our wind it would be impossible to reach either the one or the other. There were numerous dangers in the way which would at all events have to be encountered.

We were moving sluggishly on amid the fast rising seas, when I saw an object in the water, still at a considerable distance ahead. Now it appeared on the summit of a sea, now it sank into a hollow. It looked so much like the wreck of a vessel that I reported it to the first mate.

“Maybe some unfortunate craft capsized by the squall, a fate which might have been ours had not the masts given way,” he observed. “We’ll endeavour to keep close to her in case any of the crew may have escaped and be clinging to the wreck.”

As we got nearer I jumped up on the forecastle, when I saw that the object was a vessel of some sort, but not an European craft. She was a prahu, probably one of the fleet we had before seen. In a short time I perceived that there was some one on board clinging to the stern, which was the highest part out of water.

I at once told the first mate. He and the second mate held a short consultation as to the best means of rescuing the person—pirate as he might be, we could not leave him to perish.

Some spars had been lashed to the stump of the foremast on which a royal had been set, and this enabled us to have the brig somewhat under command. Ropes were got ready to heave to the man. The boatswain, who took the helm, steered the vessel so as to pass close to the wreck without the danger of running her down. Immediately the brig’s side touched her a rope was hove to the man, who was standing up ready to catch it.

“Haul away!” he shouted, as he clutched it firmly, and several willing hands being ready to haul him in. The next instant he was on board the brig, while the wreck, bounding off from us, dropped aft, about, it seemed, to plunge beneath the foaming seas.

“Why, my lad, who are you?” asked the first mate, who had assisted him on board.

“I am an Englishman,” was the answer of the stranger, but he in vain tried to say more.

“Though you are pretty well sun-burnt, you have an Englishman’s face sure enough, though you seem to have lost the use of your tongue.”

“Long, long time no talk English,” replied the man, who seemed to understand pretty clearly what was said to him. We had too much to do, however, to spend time in asking him questions.

Before night we had some spars lashed to the stump of the main-mast, which enabled us to set a little after sail and bring the vessel to.

It was of the greatest importance not to run further eastward. Happily the wind shifted, and getting the vessel’s head round we steered for Singapore. The gale, too, began to abate, and the sea to go down, so that we were able to carry on our work with less difficulty than had before been the case. The dangers in our course were numerous, but we hoped, by constant vigilance, to avoid them.

Chapter Three.

We had an anxious time of it as we made our way back to Singapore, between islands innumerable and coral reefs below water, on which it was often with difficulty we avoided running. The first mate was seldom off the deck, and Crowfoot, the boatswain, showed that he did not boast without justice of his seamanship.

It is on such occasions that a sailor has an opportunity of proving what he is made of. The wind continued fair and the weather fine, or our difficulties would have been greatly increased. The less I say of the second mate the better. Uncle Jack did not trust him, and while it was his watch on deck constantly sent me up, or made an excuse for running up himself to see how matters were going on. He insisted also on taking his share in attending on our poor captain, who remained in his berth unable to move, and, as we feared, in a very precarious state. Blyth and I assisted in nursing him, but the second mate, through whose carelessness the brig had been dismasted and the captain injured, refused to take the slightest trouble to help us—indeed, he kept out of the cabin altogether. The young man we had rescued from the Malay prahu gradually regained his recollection of English, but from the first he showed an unwillingness to talk about himself, and I observed that he kept aloof as much as possible from the crew. When I asked his name he said it was Ned Light, that he had been wrecked somewhere to the eastward, and, narrowly escaping with his life, had been taken prisoner by the pirates, who had kept him ever since in bondage. He appeared to be more ready to talk to little Jem than to any one else, and the two were constantly together. When I tried to find out from the boy what account Ned gave of himself, Jem was remarkably reticent. At length, however, one day he said, “He seems to be afraid of some of the men, sir. He thinks that they intend to do him harm, but I cannot find out why he has got that idea into his head. I told him that he might trust you and the first mate, but he only answers, ‘Better not talk.’”

All had gone well in consequence of the constant watchfulness and untiring efforts of the first mate, when, as we were within about four days’ sail of our destination, while rigging out a boom on which to set a square sail, one of our best hands, Dick Mason, fell overboard. The brig was running about four knots through the water, and as Mason could swim well, no one felt much apprehension about his safety. The sails were instantly clewed up, and the only boat which had escaped injury was at once lowered. Ned and I, with Crowfoot, the boatswain, and two other hands jumped into her and pulled away towards our shipmate, who was striking out boldly to meet us. Before the boat was lowered, however, the brig had run some distance, and we had a considerable way to go. Just as I was going down the side I saw a black fin rising above the surface, passing close under the stern. The boatswain I knew had seen it too, for he urged us to use our utmost exertions to reach Mason, and sang out to him to keep splashing about with all his might. We did our best, making the oars bend again. We were within half a cable’s length of the poor fellow, when a fearful shriek reached our ears. I instinctively turned round just in time to see his head disappear beneath the bright surface. There was a ripple where he went down, and as we got up to the spot and looked into the depths of the ocean we could see a struggling human form surrounded by a ruddy tinge, and the glittering white of the shark’s lower jaws. Ned, who was in the bows, plunged down his boat-hook, but Mason’s hands were already far below the point he could reach. The next instant the shark had disappeared with its prey.

All hope of recovering even the body of our poor shipmate was gone, and we returned with sad hearts on board.

“He is a great loss to us,” remarked the boatswain. “He was one of the men I could always trust, and that’s more than I can say of some of the rest.”

“But Tim Howlett and Trinder are smart hands, surely?” I observed.

“They may be, but I don’t like their goings on. If others trust them, it’s more than I do.”

“I am sorry to hear you say that of the men,” I remarked. “I fancied that they were about the best men we have on board.”

“You haven’t seen as much of them as I have, or you wouldn’t say that of them,” replied the boatswain.

“I’ll give a hint to the first mate of what you think,” I said.

“No use in doing that. He generally has his weather eye open, but he’s too generous to believe evil of a man unless he has strong proof. You must leave him to find the matter out for himself.”

At last we sighted the island of Singapore. Instead, however, of bringing up before the town we made a signal for three boats, which towed us into the new harbour. There we came to an anchor close to the shore, and were able to refit much more rapidly than we could have done in any other place. Our crew generally laboured away from sunrise to sunset without complaining. But Howlett and Trinder grumbled at the additional work they had to perform. The second mate seemed always out of humour, and went about his duty in a listless fashion, frequently abusing the men without any cause for so doing. The captain, who was getting better, would not allow himself to be taken on shore to the hospital, asserting that he was much more comfortable on board with Mr Radburn, Blyth, and me to look after him, than he should be there. We, however, persuaded him to let us send for a doctor, who came, and, greatly to our relief, assured us that he was going on favourably, although it might be a long time before he would be able to attend to his duty on deck. The first mate had asked Ned if he would enter in place of Mason, but he did not—as I thought he would have been glad to do—accept the offer.

I spoke to him, advising him to remain, assuring him that he would be well treated.

“The first mate and boatswain are kind to me, but I think, sir, I had better ship on board another vessel homeward-bound,” he replied.

I asked him, however, to remain a day or two, which he agreed to do. Next morning, when the hands were mustered for work, Howlett and Trinder were not to be found. I was sent on shore to look for them, it being supposed that they were not far off, but after a long search I had to return on board and say that I could not find them. There was a creek a little way off lined with mangrove bushes. The captain therefore directed Mr Blyth and me to take one of the boats and pull up it with four hands, all of us well-armed, thinking that the deserters might have concealed themselves somewhere on its banks, hoping to get an opportunity of making their way over to Singapore.

We had got a short distance up the creek when I saw a vast number of dark objects hanging to the bows of the mangrove trees.

“Are those things fruit, or are they the nests of birds?” I asked, pointing them out to Mr Blyth.

“Neither one nor the other,” he answered: “those are bats, or, as they here are called, flying foxes. As we return they will be on the move, and you will then see what they are like.”

“I will take the present opportunity,” I answered, and steering the boat closer in to the shore I observed that there were thousands and tens of thousands of the creatures hanging by their claws to the boughs in a most curious manner as thick as a swarm of bees. With a boat-hook we pulled off two or three, which falling inboard were picked up. They showed, however, no fear, nor did they make any attempt to escape, but licked our hands and appeared perfectly at ease. The head was like that of a miniature fox, and the skin was beautifully soft. Blyth told me that they live upon fruit, large quantities of which they consume. On reaching the head of the creek we found a hut, in or about which it was supposed that the runaways might have concealed themselves, but we could discover no traces of them, and consequently judged that it would be useless to search further in that direction.

The dusk of evening had come over as we pulled down the creek, and the bats had begun to stir. Presently the whole air was filled with them as they took their flight towards the plantations where they were about to forage. They looked, with their wings stretched out, of wonderfully large size, so as literally to darken the sky.

The next day passed and still we could hear nothing of the two men. The captain on this sent Blyth and me over to Singapore, where we found that they had entered on board a homeward-bound ship and had sailed. With the assistance of the agent we succeeded in replacing them by two other Englishmen, and we also engaged four Lascars, fine active-looking fellows, who were likely to prove of much use, as they could endure the heat of the sun better than could our own men.

The captain inquired whether the man we had picked up had entered.

“He has been working very steadily,” answered the first mate, “but Harry shall ask him if he intends to remain.”

When the men knocked off work I went forward to speak to him.

“Well, Ned, what have you determined on?” I asked; “the captain wishes to know whether you will enter.”

“I will very gladly do so, Mr Harry,” he answered. “I like you and the first officer, and as I have no friends at home who care for me, I am in no hurry to get back to old England.”

“Why were you unwilling to enter before?” I inquired.

“Well, sir, I don’t mind telling you now. It was on account of those two fellows, Howlett and Trinder. I have served with them before, and us I know a thing or two about them, and that they are mutinous, ill-disposed rascals, I was afraid that they would find me out, and some dark night heave me overboard, or knock me on the head.”

“On board what ship did you serve with them?” I asked.

“On board the ‘Amphion,’” he answered. “They and several others of the crew, tarred with the same brush, stole a boat and deserted from her, leaving us so short-handed that, one of the officers and two other hands being washed overboard, when the ship caught in a typhoon we were unable to manage her, and she drove on a reef and was lost, we who remained scarcely escaping with our lives.”

“The ‘Amphion!’” I exclaimed, much astonished. “Why, that was my father’s ship! Did you say the captain escaped?”

“Yes; all of us, except one poor fellow, got safely on shore, but it was a wild place, and we found ourselves among savages, who threatened to take our lives, but they did not, though they ill-treated us, and made us work for them.”

“Do you think the captain is still alive? Can you pilot us to the place?” I inquired eagerly.

“All I can say is that the captain was well in health, though sadly cast down, when I last saw him,” answered Ned. “As to finding the spot where we were wrecked, that is what I fear I cannot do, for I don’t know even the name of the country; and as I am ignorant of navigation, and was soon afterwards carried away by the Malay pirates, who took me about with them from place to place, I have lost all reckoning, though I calculate that it was somewhere away to the eastward. I think, however, that I should know the country if I saw it again, though these islands are so much like one another that I could not be certain; but do you say, sir, that you are Captain Musgrave’s son? I have only heard you called Mr Harry, and I did not know it before, or I should have spoken to you.”

“Yes, Captain Musgrave, who commanded the ‘Amphion,’ was my father, and we have long given him up for lost,” I replied. “Do you think that he remained at the place where the ship was wrecked, or was he carried off by the pirates?”

“He was not carried off by those who took us, for he and the first mate and two seamen had gone up the country, and so escaped. Three others were taken with me, but what became of them I do not know, may be they were drowned or krissed by the Malays, as I never saw them again; indeed, it is a wonder that I am alive, seeing what I have gone through. The fellows who first got hold of me did not keep me long, but sold me to another gang. They and I were afterwards wrecked, and when we were trying to make our escape on board some canoes we had built, we were overtaken by another fleet of pirates, who killed most of my companions. They spared my life, but sold me after some time to the people to whom the prahu belonged, from the wreck of which you picked me up.”

“You must come aft and narrate what you have told me to the first mate,” I said.

I ran down to tell the captain and first mate, who directed me to bring Ned below, that they might hear his story. Having cross-questioned him far more than I had done, they were perfectly satisfied that he had spoken the truth, though they found it impossible to make out where the ‘Amphion’ had been wrecked. They put a chart before him, but he was utterly unable to guess where the wreck had occurred, or even to point out Singapore, where we then were. Thus we were left in doubt whether the ‘Amphion’ had been lost on the coast of Borneo or on that of Celebes or Gillolo, or even as far east as New Guinea.

Ned’s account made my uncle and me more eager than ever to continue the voyage. The captain fully entered into our feelings, but at the same time he felt that it was his duty to attend to the interests of the owners, and to visit only the places where trade could be carried on. The Dutch, who hold possession of Java and many of the Spice Islands to the eastward, throw so many difficulties in the way of commerce for the sake of keeping it in their own hands, that the captain had been directed not to visit any of their ports if he could avoid doing so. Our object therefore was to trade chiefly with the natives, from whom we were more likely to learn something about the wreck of the “Amphion” than from the Dutch, for it was considered that if they had had any communication with the survivors of her crew, means would have been found to send home an account of the occurrence. Now, as I have said, nothing had been heard of the “Amphion” when we left England, nearly four years after the time it was supposed she had been lost, beyond the statement made by the two men who said they had escaped from her. Ned’s account showed that the owners were right in their conjectures as to the possibility of her having been cast on some desert shore, instead of having gone down, as was more generally believed, in a typhoon. By working night and day, we at length got the “Lily” ataunto, and we were thankful when being towed cut of harbour we found ourselves with a fair wind standing to the eastward. We had the same dangers of coral reefs, sand banks, and low islands to encounter as before, but we were in a better condition now to avoid them.

Having passed the island of Labuan—since taken possession of by the English—on the north-west of Borneo, we stood along the coast until we rounded the northern end of that large island. To give some idea of the size of Borneo, I may say that the whole of England, Ireland, and Scotland, with the Orkney and Shetland Islands, would fit inside it, leaving a very wide margin all round in addition. We were talking about the inhabitants, when Uncle Jack observed—

“With the exception of Sarawak in the west, the whole of this magnificent country is in a state of barbarism. The few Malay settlements along the coast are but very slightly removed from the same condition. It is said that the chief delight of the Dyak tribes, who inhabit the interior as well as the larger part of the coast and the banks of the rivers, is to attack their neighbours for the sake of obtaining heads, and that no lover can present himself before his intended bride until he offers her one of those gory trophies as a proof of his prowess. The greater the number of heads he can present, the more willing the damsel becomes to receive his advances. Notwithstanding such a peculiar custom, the Dyaks possess many excellent qualities. They are said to be truthful and honest, generally intelligent, kind tempered and mild, and tolerably industrious; superior indeed in many respects to the Malays and Chinese, who cheat and plunder them.

“While we are opening up Africa, it seems to me that we should make an effort to civilise and carry the blessings of Christianity to the numberless inhabitants of Borneo beyond the province of Sarawak.”

We passed through the Straits of Balabac, between Borneo and the long island of Palawan into the Sooloo Sea, said to be infested by pirates, who have little difficulty in escaping pursuit among the numerous islands to the south, forming the Looloo Archipelago. To the east of us were the Philippine islands, owned and misgoverned by the Spaniards.

We, however, kept along the coast of Borneo, and though pirates might have swarmed in its bays and rivers, we were fortunate in not falling in with any. We met, however, several traders, Chinese as well as Malay, from whom we made inquiries through Ned respecting the wreck of an English vessel in those seas. Blyth also endeavoured to obtain information as to where the articles we wished to procure were most likely to be obtained. The captain of one of the Malay vessels came on board us to do some trading on his own account. As he seemed inclined to be communicative, we put several questions to him through Ned, who was evidently highly interested in the replies he received.

To our questions as to what the Malay said, Ned replied, “He tells me, sir, that he has heard of several white men being at a village on the banks of a large river some way up from the coast. As far as I can make out, they have been there a long time, and the natives won’t let them get away. The people he speaks of may be Captain Musgrave and some of my old shipmates; but yet it does not seem to me from the sort of country he describes that it can be near the place where the ‘Amphion’ was lost.”

We told Ned to inquire if one of the men belonging to the prahu would be willing to pilot us up the river, promising him a handsome reward if he would do so, and undertaking to set him on shore at any place he might name which we could reach. For this purpose the first mate, Blyth, and I, taking Ned, went with the Malay captain on board his vessel. Summoning his crew, he explained the object of our visit and the offer which had been made. After a long palaver a man stepped out and expressed his readiness to accompany us. The Malay captain, after a short talk with the man, introduced him to us, saying that his name was Kalong, that he was well acquainted with the coast and an experienced sailor, as indeed are most of the Malays of the archipelago. This matter, with which all parties were pleased, being settled, we returned to the “Lily,” and sail was made for the part of the coast where Kalong informed us we should find the mouth of the river. We hove to soon after sunset that we might not pass the spot during the night.

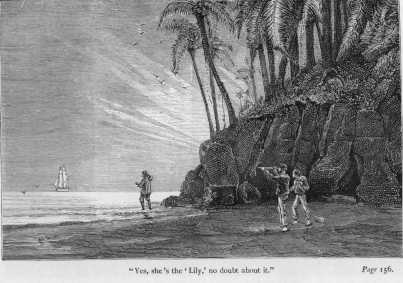

When Kalong came on deck at daybreak, we once more stood in for the coast. The wind, however, was light, so that we made but little progress. He pointed to the southward, indicating that we must steer in that direction. At length, to our great joy, we saw what was evidently the mouth of a large river, fringed thickly with mangrove trees.

Ned shook his head. “That’s not where the ‘Amphion’ was cast away,” he remarked, as we stood towards it. “Still it may be, notwithstanding, that our friends are up there. Kalong says that there is water enough for the brig all the way up to the village, but he thinks it would be wiser to anchor just within the mouth and let only the boats go up, as the wind might fail us and we might have a hard job to get out again. As it is a long pull he also advises that the boats should leave the brig in the evening, so as to get to the place the next day.”

This advice exactly agreed with what the first mate thought best, and Captain Haiselden, whom he consulted, was of the same opinion. We accordingly, the wind favouring us, stood on and brought up just inside the mouth, which formed a beautiful harbour. We lost no time in getting ready for our expedition. Two boats were lowered, each pulling four oars, the crews consisting of four Englishmen and four Lascars, besides Kalong and Ned, the first mate and I going in one and Mr Blyth and the boatswain in the other. We were all well-armed, and had provisions for a couple of days. We also carried a number of articles for trading with the natives, whom we hoped, from Kalong’s account, to find friendly.

We had thus left but a small number of men on board, but as the brig was in a safe place, the captain, trusting to Kalong’s report, considered that there was no risk of her being attacked by pirates. I heard him tell the first mate, however, when we went into his cabin to wish him good-bye, that he should have a sharp look-out kept, the guns loaded, and all hands armed in case of accident; and, he added, “Remember, Radburn, that you are to run no unnecessary risk; don’t trust the natives too much, and keep your party well together if you land, so as to be able to get back to the boats. Kalong may be a very honest fellow, but it is as well not to rely too much on him. If you hear of any Englishmen being in the village or neighbourhood, get Kalong to open up a communication with them, and send a written note to ask who they are.”

“Aye, aye, sir!” answered Uncle Jack; “you may depend upon my discretion.”

I naturally felt very eager, for I had persuaded myself that we should certainly find my father, notwithstanding Ned’s doubts. I do not think my uncle was quite so sanguine, still he was very willing to undertake the expedition. We had on board a small light canoe, which we had brought from Singapore, large enough to carry two or three people, but easily paddled by one. At the last moment it was determined to carry this canoe with us, as she could tow astern, and might be of great use in sending ahead to act as a scout.

As soon as everything was ready we shoved off, our shipmates remaining on board, giving us three hearty cheers as we pulled away. We found that the river made several bends, so that in a short time we were out of sight of the brig.

As we passed close, sometimes to one bank, sometimes to the other, we could hear the cooing of pigeons, the shrill call of peahens, and the notes of many song birds; above which rose the chattering of troops of monkeys, while parrots and other gaily-coloured birds flew from bough to bough. The monkeys occasionally showed themselves, leaping along the branches, often running out to those above our heads and uttering hoarse cries, as if ordering us away from their domains, grinning fiercely at us, hooting and chattering, and shaking the boughs in their indignation.

We had got up some distance, and calculated that it would be dark in the course of a short time, when, having entered another reach, we saw before us on the right hand shore an opening in which were several huts, of a construction common in that country, being erected on tall posts with a ladder leading to them.

Kalong said that he was not aware of any village being there, and that it had probably not long been established. As we could see only three huts, and as there were not likely to be many inhabitants, he and Ned offered to go on shore and obtain information, while we remained in the boats with our arms ready for use, should the natives show any signs of hostility. Uncle Jack, however, directed us to keep our weapons concealed, while we had, besides the English ensign, a white flag flying in the bows of our boat.

Blyth, on hearing of the plan, wished to land, and my uncle, after a little hesitation, gave me leave to accompany him, provided we kept behind Kalong and Ned until they had ascertained the character of the people. We accordingly at once pulled in for the bank. Kalong and Ned sprang on shore, Blyth and I fallowing. We had pistols in our belts, and each wore a sword; but, as the Malays all go armed, such weapons were not likely to make them suppose that we were otherwise than peaceably disposed.

We had not proceeded far, when several Dyaks, who had apparently been watching us from their elevated dwellings, came down the ladders which led from them to the ground, and made friendly gestures, inviting us to advance. The men wore waist cloths of blue cotton which hung down behind, and were bordered with blue, white, and red. Their heads were bound with handkerchiefs of the same colours. They wore earrings of brass, and heavy necklaces of black and white beads. On their arms were a number of rings of white shells or brass, their long shining black hair hanging over their shoulders, and to their waists, secured by a belt, was a pouch with materials for “betel” chewing. In the belt was stuck a long slender knife, and most of the men held in their hands a knife-headed spear.

The women, who were better clothed than the men, wore coils of rattan to which their petticoats were fastened round their waists, besides which their arms and legs were ornamented with rings of brass wire, and their heads by hats of curious shape, adorned with beads. They had generally a pleasant expression of countenance, and appeared ready to afford us a friendly welcome.

Kalong and Ned at once entered into conversation with them, as they seemed perfectly to understand each other. No information, however, could be obtained about the white men of whom we had heard. Without hesitation they came down to the boats, bringing some mats and other articles which we purchased at a very moderate rate. They had also with them some curious monkeys with enormous noses, faces of a brick-dust colour, and about as ugly specimens of the monkey tribe as I ever saw.

Their bodies were about three feet in length covered with thick fur, of a bright chestnut-red. I am almost afraid to say how long their noses were, but they stuck out with the nostrils at the tips and had certainly a most curious appearance. The arms and legs had somewhat of a whitish tinge, and the hands were grey rather than black. Ned told us that they were very active, and when at liberty could be seen leaping from branch to branch, generally in large troops, holloaing loudly as they go along. Blyth purchased a couple, as they were very tame and seemed well-mannered. He hoped to be able to keep them alive if he could obtain suitable food.

After a short and satisfactory intercourse with our native friends, we shoved off and proceeded up the river. The tide, however, soon turned, and Uncle Jack, considering that it would be useless to attempt pulling against it, brought up for the night a short distance from the left bank, but sufficiently far off not to run the risk of being surprised by hostile natives.

As we had a long pull before us, the first mate arranged that all hands should lie down except two in each boat to keep watch, that we might be the better able to work the next day. Supper, however, was first served out, for we had hitherto not had time to eat anything. It was arranged that Ned and I should have the first watch in our boat, and as soon as supper was over, the rest of the party stowed themselves away as best they could on or under the thwarts. The boats lay in the shadow cast by the tall trees on the bank nearest to us, from which strange sounds ever and anon came off, produced either by wild beasts or insects, not sufficiently loud to drown the ripple of the water as it flowed rapidly by. The bright stars shone down from a cloudless sky on the surface of the stream, flickering and dancing in the eddies caused by the current.

I found great difficulty in keeping awake, though, of course, I did my best to prevent my eyelids from closing by constantly shifting my position and looking round in every direction, not that I apprehended danger, but from knowing that it was my duty to be prepared for any contingency.

I had been on watch for an hour or more, when Ned, who was seated on a thwart, stepped aft. “Hist, Mr Harry,” he said, in a low whisper, “do you hear the sound of voices coming down the river?”

I fancied that I did.

“Just listen.”

I listened, and after some time could distinctly hear some strange sounds, though I was not certain that they were those of human voices. I awoke the first mate, who also heard them.

“If you like, sir, Kalong and I will pull up in the canoe and try and find out where they come from,” whispered Ned; “it may be that the natives are only holding one of their harvest feasts near the bank of the river, or it is just as likely that a fleet of pirates has come up through some other branch of the river, and has been plundering the villages they have fallen in with, as I have known them often to do in these parts. It wouldn’t be safe to fall in with them. They would soon run down our boats and not leave a man of us alive.”

“Though you may be mistaken, we will take the prudent course and try to find out who the people are,” answered the first mate. “Wake up Kalong, and you and he jump into the canoe and paddle ahead until you have discovered what they are about. Take care, however, that you are not caught yourselves.”

Ned awakened the Malay and explained the object we had in view, when the two hauling up the canoe alongside got into her and noiselessly paddled up the river, keeping near the bank where we lay moored.

We waited anxiously listening for any sound, but a light breeze rustling among the trees prevented those we had before heard from reaching our ears.

“Ned, I hope, may have been mistaken, after all,” observed the first mate; “it would be a pity, having got this far, to have to give up our expedition; but, as he says, it would never do to run the risk of an encounter with those savage pirates. If he is right we must do our best to avoid them and be ready for a start.”

All hands in both boats had been aroused, and we were prepared to heave up our anchors and get out the oars at a moment’s notice. We had not only our own safety to think of, but that of our shipmates, if there really was a fleet of pirates in the river, should they discover the brig—ill able to defend herself as she was—they might attack and capture her before we could get on board. We had brought the two boats alongside each other, so that we could talk without raising our voices. The first mate, who had been standing up on the after thwart that he might the better be able to see any object ahead, at length observed, “The canoe ought to have been back by this time. Can she have been taken by the savages?”

“If so, Kalong and Ned may for the sake of saving their lives have told them about the brig,” observed the boatswain. “If there is another channel the pirates will go down it and attack her before they look after us.”

“I feel very sure that Ned will not prove treacherous, though I cannot say how the Malay will act,” I observed.

“At all events we will get up our anchors and be ready for a start,” said the first mate.

He gave the order accordingly. Just as they were up to the bows, I caught sight of a small object ahead, which I trusted was the canoe. I pointed it out to the first mate.

“No doubt about it. I hope that we shall find that we might have saved ourselves the trouble of weighing,” he observed.

It approached rapidly. In little more than a minute it dropped alongside us and Ned and Kalong leapt into our boat.

“Not a moment to lose!” exclaimed Ned; “there’s a whole fleet of prahus in the next reach. Some of the people were ashore, and that we might find out who they were, we landed some way below where they lay and crept up close to them until we could hear them speaking. They know of the brig, and, we found, were just about to get under weigh hoping to surprise her.”

“We must be on board first, then, or they’ll murder the whole of us. Out oars, lads, and pull as you never pulled before,” cried the first mate.

The crews required no further orders, the boats were got round and away we went with the current, the men pulling with all their might.

“We must go on board and fight for our lives, for if we are taken they’ll not be worth much,” said the first mate.

“My poor father, what will become of him?” I exclaimed.

“We have no proof that your father is among the white men spoken of, Harry. If he is, he will not be worse off than he would have been had we not gone up the river. We must, however, try and ascertain the truth of the report, and make another attempt to rescue him should we find that he is really there.”