The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirate Island, by Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

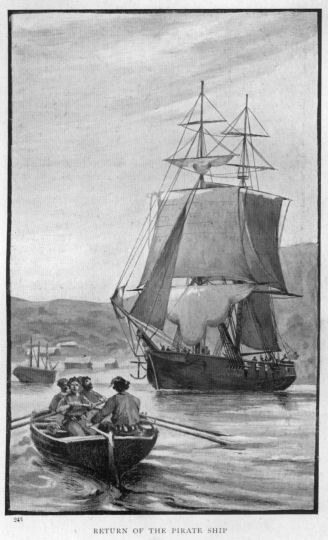

Title: The Pirate Island

A Story of the South Pacific

Author: Harry Collingwood

Illustrator: C.J. Staniland and J.R. Wells

Release Date: April 13, 2007 [EBook #21072]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATE ISLAND ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"The Pirate Island"

A Story of the South Pacific.

Chapter One.

The Wreck on the “Gunfleet.”

It was emphatically “a dirty night.” The barometer had been slowly but persistently falling during the two previous days; the dawn had been red and threatening, with a strong breeze from S.E.; and as the short dreary November day waxed and waned this strong breeze had steadily increased in strength until by nightfall it had become a regular “November gale,” with frequent squalls of arrowy rain and sleet, which, impelled by the furious gusts, smote and stung like hail, and cleared the streets almost as effectually as a volley of musketry would have done.

It was not fit for a dog to be out of doors. So said Ned Anger as he entered the snug bar-parlour of the “Anchor” at Brightlingsea, and drawing a chair close up to the blazing fire of wreck-wood which roared up the ample chimney, flung himself heavily down thereon to await the arrival of the “pint” which he had ordered as he passed the bar.

“And yet there’s a many poor souls as has to be out in it, and as is out in it,” returned the buxom hostess, entering at the moment with the aforesaid pint upon a small tray. “It’s to be hoped as none of ’em won’t meet their deaths out there among the sands this fearful night,” she added, as Ned took the glass from her, and deposited his “tuppence” in the tray in payment therefor.

A sympathetic murmur of concurrence went round the room in response to this philanthropic wish, accompanied in some instances by doubtful shakes of the head.

“Ay, ay, we all hope that,” remarked Dick Bird—“Dicky Bird” was the name which had been playfully bestowed upon him by his chums, and by which he was generally known—“we all hopes that; but I, for one, feels uncommon duberous about it. There’s hardly a capful of wind as blows but what some poor unfort’nate craft leaves her bones out there,”—with a jerk of the thumb over his shoulder to seaward,—“and mostly with every wreck there’s some lives lost. I say, mates, I s’pose there’s somebody on the look-out?”

“Ay, ay,” responded old Bill Maskell from his favourite corner under the tall old-fashioned clock-case, “Bob’s gone across the creek and up to the tower, as usual. The boy will go; always says as how it’s his duty to go up there and keep a look-out in bad weather; so, as his eyes is as sharp as needles, and since one is as good as a hundred for that sort of work, I thought I’d just look in here for a hour or two, so’s to be on the spot if in case any of us should be wanted.”

“I’ve often wondered how it is that it always falls to Bob’s lot to go upon the look-out in bad weather. How is it?” asked an individual in semi-nautical costume at the far end of the room, whose bearing and manner conveyed the impression that he regarded himself, as indeed he was, somewhat of an intruder. He was a ship-chandler’s shopman, with an ambition to be mistaken for a genuine “salt,” and had not been many months in the place.

“Well, you see, mister, the way of it is just this,” explained old Maskell, who considered the question as addressed more especially to him: “Bob was took off a wrack on the Maplin when he was a mere babby, the only one saved; found him wrapped up warm and snug in one of the bunks on the weather side of the cabin with the water surging up to within three inches of him; so ever since he’s been old enough to understand he’ve always insisted as it was his duty, by way of returning thanks, like, to take the look-out when a wrack may be expected. And, don’t you make no mistake, there ain’t an eye so sharp as his for a signal-rocket in the whole place, see’s ’em almost afore they be fired—he do.”

“And did you ever try to find his relatives?” asked the shopman.

“Well, no; I can’t say as we did, exactly,” answered old Bill, “’cause you see we didn’t rightly know how to set to work at the job. The ship as he was took off of was a passenger-ship, the Lightning of London, and, as I said afore, he was the only one saved. There were nobody else as we could axe any questions of, and, the ship hailing from London, there was no telling where his friends might have come from. There was R.L. marked on his little clothes, and that was all. So we was obliged to content ourselves with having that fact tacked on to the yarn of the wrack in all the papers, in the hope that some of his friends or relations might get to see it. But, bless yer heart! we ain’t heard nothing from nobody about him, never a word; so I just adopted him, as the sayin’ is, and called him Robert Legerton, arter a old shipmate of mine that’s been drowned this many a year, poor chap.”

“And how long is it since the wreck happened?” inquired the shopman.

“Well, let me see,” said old Bill. “Blest if I can rightly tell,” he continued, after a moment or two of reflection. “I’ve got it wrote down in the family Bible at home, but I can’t just rightly recollect at this moment. It’s somewheres about fourteen or fifteen years ago this winter, though.”

“Fourteen year next month,” spoke up another of the company, decidedly. “It was the same gale as my poor brother Joe was drowned in.”

“Right you are, Tom,” returned Bill. “I remember it was that same gale now, and that’s fourteen year agone. And the women as took charge of poor little Bob when we brought him ashore reckoned as he was about two year old or thereaway; they told his age by his teeth—same as you would tell a horse’s age, you know, mister.”

“Ay! that was a terrible winter for wrecks, that was,” remarked Jack Willis, a fine stalwart young fellow of some five-and-twenty. “It was my first year at sea. I’d been bound apprentice to the skipper of a collier brig called the Nancy, sailing out of Harwich. The skipper’s name was Daniell, ‘Long Tom Dan’ell’ they used to call him because of his size. He was so tall that he couldn’t stand upright in his cabin, and he’d been going to sea for so many years that he’d got to be regular round-shouldered. I don’t believe that man ever knowed what it was to be ill in his life; he used to be awful proud of his good health, poor chap! he’s dead now—drowned—jumped overboard in a gale of wind a’ter a man as fell off the fore-topsail-yard while they was reefing; and, good swimmer as he was, they was both lost. Now, he was a swimmer if you like. You talk about young Bob being a good swimmer, but I’m blessed if I think he could hold a candle to this here Long Tom Dan’ell as I’m talking about. Why, I recollect once when we was lyin’ wind-bound in Yarmouth Roads—”

At this point the narrator was interrupted by the sudden opening of the door and the hurried entry of a tall and somewhat slender fair-haired lad clad in oilskin jumper, leggings, and “sou’-wester” hat, which glistened in the gaslight; while, as he stood in the doorway for a moment, dazzled by the abrupt transition from darkness to light, the water trickled off him and speedily formed a little pool at his feet on the well sanded floor.

This new-comer was Bob Legerton, the hero of my story.

“Well, Bob, what’s the news?” was the general exclamation, as the assembled party rose with one accord to their feet. “Rockets going up from the ‘Middle’ and the ‘Gunfleet,’” panted the lad, as he wiped the moisture from his eyes with the back of his hand.

“All right,” responded old Bill. Then drawing himself up to his full height and casting a scrutinising glance round the room, he exclaimed—

“Now, mates, how many of yer’s ready to go out?”

“Why, all of us in course, dad,” replied Jack Willis. “’Twas mostly in expectation of bein’ wanted that we comed down here to-night. And we’ve all got our oilskins, so you’ve only got to pick your crew and let’s be off.”

A general murmur of assent followed this speech, and the men forthwith ranged themselves along the sides of the room so as to give Bill a clear view of each individual and facilitate a rapid choice.

“Then I’ll take you, Jack; and you, Dick; and you; and you; and you;” quickly selecting a strong crew of the stoutest and most resolute men in the party.

The chosen ones lost no time in donning their oilskin garments, a task in which they were cheerfully assisted by the others; and while they were so engaged the hostess issued from the bar with tumblers of smoking hot grog, one of which she handed to each of the adventurers, saying—

“There, boys, drink that off before you go out into the cold and the wet; it’ll do none of you any harm, I’m sure, on a night like this, and on such an errand as yours. And you, Bill, if you save anybody and decide to bring ’em into Brightlingsea, send up a signal-rocket as soon as you think we can see it over the land, and I’ll have hot water and blankets all ready for the poor souls against they come ashore.”

“Ay, ay, mother; I will,” replied old Bill. “Only hope we may be lucky enough to get out to ’em in time; the wind’s dead in our teeth all the way. Now, lads, if ye’re all ready let’s be off. Thank’ee, mother, for the grog.”

The men filed out, Bill leading, and took their way down to the beach, a very few yards distant, the dim flickering light of a lantern being exhibited from the water-side for a moment as they issued into the open air.

“There’s Bob waitin’ with the boat; what a chap he is!” ejaculated one of the men as the light was seen. “I say, Bill, you won’t take Bob, will you, on an errand like this here?”

“Oh, ay,” responded Bill. “He’ll want to go; and I promised him he should next time as we was called out. He’s a fine handy lad, and old enough to take care of himself by this time. Besides, it’s time he began to take his share of the rough work.”

Reaching the water’s edge they found Bob standing there with the painter of a boat in his hand, the boat itself being partially grounded on the beach. They quickly tumbled in over the gunwale; Bob then placed his shoulder against the stem-head, and with a powerful “shove,” drove the boat stern-foremost into the stream, springing in over the bows and stowing himself away in the eyes of the boat as she floated.

It appeared intensely dark outside when the members of the expedition first issued from the hospitable portal of the “Anchor;” but there was a moon, although she was completely hidden by the dense canopy of fast-flying clouds which overspread the heavens; and the faint light which struggled through this thick veil of vapour soon revealed a small fleet of fishing smacks at anchor in the middle of the creek. Toward one of these craft the boat was headed, and in a very few minutes the party were scrambling over the low bulwarks of the Seamew—Bill Maskell’s property, and the pride of the port.

The boat was at once dragged in on deck and secured, and then, without hurry or confusion of any kind, but in an incredibly short time, the smack was unmoored and got under weigh, a faint cheer from the shore following her as she wound her way down the creek between the other craft, and, hauling close to the wind, headed toward the open sea.

In a very few minutes the gallant little Seamew had passed clear of the low point upon which stands the Martello Tower which had been Bob’s place of look-out, and then she felt the full fury of the gale and the full strength of the raging sea. Even under the mere shred of sail—a balance-reefed main-sail and storm jib—which she dared to show, the little vessel was buried to her gunwale, while the sea poured in a continuous cataract over her bows, across her deck, and out again to leeward, rendering it necessary for her crew to crouch low on the deck to windward under the partial shelter of her low bulwarks, and to lash themselves there.

It was indeed a terrible night. The thermometer registered only a degree or two above freezing-point; and the howling blast, loaded with spindrift and scud-water, seemed to pierce the adventurers to their very marrow, while, notwithstanding the care with which they were wrapped up, the continuous pouring of the sea over them soon wet them to the skin.

But the serious discomfort to which they had voluntarily exposed themselves, so far from damping their ardour only increased it. As the veteran Bill, standing there at the tiller exposed to the full fury of the tempest, with the tiller-ropes pulling and jerking at his hands until they threatened to cut into the bone, felt his wet clothing clinging to his skin, and his sea-boots gradually filling with water, he pictured to himself a group of poor terror-stricken wretches clinging despairingly to a shattered wreck out there upon the cruel sands, with the merciless sea tugging at them fiercely, and the wind chilling the blood within their veins until, perchance, their benumbed limbs growing powerless, their hold would relax and they would be swept away; and as the dismal scene rose before his mental vision he tautened up the tiller-ropes a trifle, the smack’s head fell off perhaps half a point, and the wind striking more fully upon the straining canvas, she went surging out to seaward like a startled steed, her hull half buried in a whirling chaos of flying foam.

Old Bill, the leader of this desperate expedition, was a fisherman in winter and a yachtsman in summer, as indeed were most of the crew of the Seamew on this eventful night. Many a hard-fought match had Bill sailed in, and more than one flying fifty had he proudly steered, a winner, past the flag-ship; but his companions agreed, as they crouched shivering under the bulwarks, that he never handled a craft better or more boldly than he did the Seamew on that night. One good stretch to the eastward, until the “Middle” light bore well upon their weather quarter, and the helm was put down; the smack tacked handsomely, though she shipped a sea and filled her deck to the gunwale in the operation, and then away she rushed on the other tack, with the light bearing well upon the lee bow.

In less than an hour from the time of starting the light ship was reached; and as the smack, luffing into the wind, shaved close under the vessel’s stern with all her canvas ashiver, Bill’s stentorian voice pealed out—

“Middle, ahoy! where a way’s the wrack?”

“About a mile and half to the nor’ard, on the weather side of the Gunfleet. Fancy she must have broke up, can’t make her out now. Wish ye good luck,” was the reply.

“Thank’ee,” roared back Bill. “Ease up main and jib-sheets, boys, and stand clear for a jibe.”

Round swept the little Seamew, and in another moment, with the wind on her starboard quarter, she was darting almost with the speed of her namesake, along the weather edge of the shoal, upon her errand of mercy.

All eyes were now keenly directed ahead and on the lee bow, anxiously watching for some indication of the whereabouts of the wreck, and in a few minutes the welcome cry was simultaneously raised by three or four of the watchers, “There she is!”

“Ay, there she is; sure enough!” responded old Bill from his post at the tiller, he having like the rest caught a momentary glimpse under the foot of the main-sail of a shapeless object which had revealed itself for a single instant in the midst of the whirl of boiling breakers, only to be lost sight of again as the leaping waves hurled themselves once more furiously down upon their helpless prey.

As the smack rapidly approached the scene of the disaster the wreck was made out to be that of a large ship, with only the stump of her main-mast standing. She was already fast settling down in the sand, the forepart of the hull being completely submerged, while the sea swept incessantly over the stern, which, with its full poop, formed the sole refuge of the hapless crew.

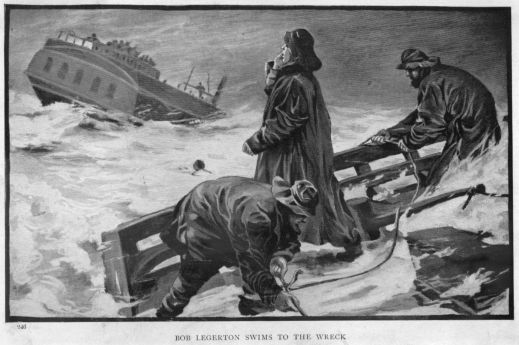

“Now, boys,” remarked old Bill when they had approached closely enough to perceive the desperate situation of those on the wreck. “Now, boys, whatever we’re going to do has got to be done smart; the tide’s rising fast, and in another hour there won’t be enough of yon ship left to light a fire wi’. Are yer all ready wi’ the anchor?”

“Ay, ay; all ready,” was the prompt response.

The helm was put down, and the smack plunged round head to wind, her sails flapping furiously as the wind was spilled out of them. There was no need for orders; the men all knew exactly what to do, and did it precisely at the right moment. Jib and main-sail were hauled down and secured in less time than it takes to describe it; and then, as the little vessel lost her “way,” the heavy anchor—carried expressly for occasions like the present—was let go, and the cable veered cautiously out so that the full strain might not be brought to bear upon it too suddenly. Old Bill, meanwhile, stood aft by the taffrail with the lead-line in his hand, anxiously noting the shoaling water as the smack drifted sternward toward the wreck.

“Hold on, for’ard,” he shouted at last, when the little Seamew had driven so far in upon the sand that there was little more than a foot of water beneath her keel when she sank into the trough of the sea. “Now lay aft here, all hands, and let’s see if we can get a rope aboard of ’em.”

The smack was now fairly among the breakers, which came thundering down upon the shoal with indescribable fury, boiling and foaming and tumbling round the little vessel in a perfect chaos of confusion, and falling on board her in such vast volumes that had everything not been securely battened down beforehand she must inevitably have been swamped in a few minutes. As for her crew, every man of them worked with the end of a line firmly lashed round his waist, so that in the extremely likely event of his being washed overboard his comrades might have the means of hauling him on board again.

Nor wore these the only dangers to which the adventurers were exposed. There was the possibility that the cable, stout as it was, might part at any moment, and in such a case their fate would be sealed, for nothing could then prevent the smack from being dashed to pieces on the sands.

Yet all these dangers were cheerfully faced by these men from a pure desire to serve their fellow-creatures, and without the slightest hope of reward, for they knew at the very outset that there would not be much hope of salvage, with a vessel on the sands in such a terrible gale.

The wreck was now directly astern of the smack, and only about one hundred feet distant, so that she could be distinctly seen, as it fortunately happened that the sky had been steadily clearing for the last quarter of an hour, allowing the moon to peep out unobscured now and then through an occasional break in the clouds. By the increasing light the smack’s crew were not only enabled to note the exact position of the wreck, but they could also see that a considerable number of people were clustered upon the poop of the half-submerged hull, some of them being women and children. The poor souls were all watching with the most intense anxiety the movements of those on board the smack, and if anything had been needed to stimulate the exertions of her crew it would have been abundantly found in the sight of those poor helpless mothers and their little ones clinging there to the shattered wreck in the bitter winter midnight, exposed to the full fury of the pitiless storm.

A light heaving-line was quickly cleared away, and one end bent to a rope becket securely spliced to a small keg, which was then thrown overboard and allowed to drift down toward the wreck, the line being veered freely away at the same time.

The crew of the wreck, anxiously watching the motions of those on board the smack, at once comprehended the object of this manoeuvre, and, as the keg drifted down toward them, made ready to secure it. But the set of the tide, the wash of the sea, or some other unexplained circumstance caused it to deviate so far from its intended course that it passed at a considerable distance astern of the wreck, notwithstanding the utmost endeavours of those on board to secure it; in consequence of which it had to be hauled on board the smack again, and thus valuable time was lost. The smack’s helm was at once shifted, and the tide, aided by the wind, gave her so strong a sheer in the required direction that it was hoped a repetition of the mischance would be impossible. The keg was again thrown overboard, the line once more veered away. Buoyantly it drifted down toward the wreck, now buried in the hissing foam-crest of a mighty breaker, and anon riding lightly in the liquid valley behind it. All eyes were intently fixed upon it, impatiently watching its slow and somewhat erratic movements, when the smack seemed to leap suddenly skyward, rearing up like a startled courser, and heeling violently over on her beam-ends at the same moment; there was a terrific thud forward, accompanied by a violent crashing sound, and the Seamew’s crew had barely time to grasp the cleat or belaying-pin nearest at hand when a foaming deluge of water hissed and swirled past and over them, the breaker of which it formed a part sweeping from under the smack down toward the wreck in an unbroken wall of green water, capped with a white and ominously curling crest. The roller broke just as it reached the wreck, expending its full force upon her already shattered hull; the black mass was seen to heel almost completely over in the midst of the wildly tossing foam, there was a dull report, almost like that of a gun, a piercing shriek, which rose clearly above the howling of the gale and the babel of the maddened waters, and when the wreck again became visible it was seen that she had broken in two amidships, the bow lying bottom-upward some sixty feet farther in upon the sand, while the stern, which retained its former position, had been robbed of nearly half its living freight. And, to make matters worse, the floating keg had once more missed its mark.

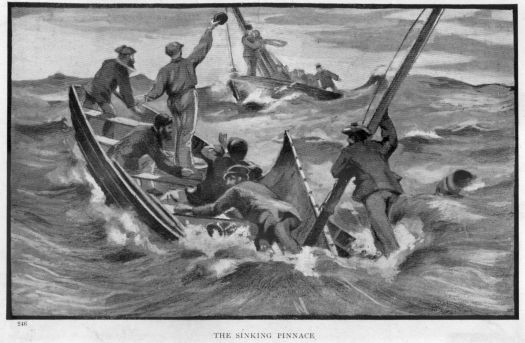

This repeated failure was disheartening. The tide was rising rapidly; every minute was worth a human life, and it began to look as though, in spite of all effort, the poor souls clinging to the wreck would be swept into eternity before the Seamew’s crew could effect a communication with them.

“Let’s have one more try, boys,” exhorted old Bill; “and if we misses her this time we shall have to shift our ground and trust to our own anchor and chain to hold us until we can get ’em off.”

Risky work that would be, as each man there told himself; but none thought of expressing such a sentiment aloud, preferring to take the risk rather than abandon those poor souls to their fate.

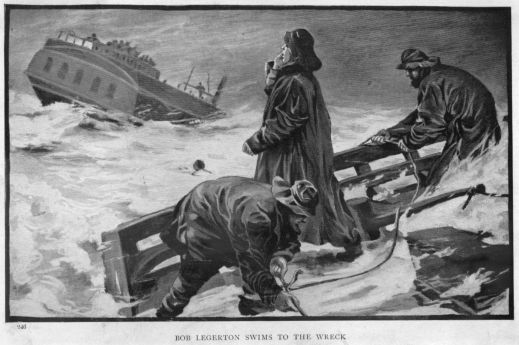

The line and keg were rapidly hauled on board the smack once more, and Bill was standing aft by the taffrail watching for a favourable moment at which to make another cast, when Bob exclaimed excitedly—

“’Vast heavin’, father; ’taint no use tryin’ that dodge any more—we’re too far to leeward. Cast off the line and take a turn with it round my waist; I’m goin’ to try to swim it. I know I can do it, dad; and it’s the only way as we can do any good.”

The old man stared aghast at the lad for a moment, then he glanced at the mad swirl of broken water astern, then back once more to Bob, who, in the meantime, was rapidly divesting himself of his clothing.

“God bless ye, boy, for the thought,” he at length ejaculated; “God bless ye, but it ain’t possible. Even if the water was warm the breaking seas ’d smother ye; but bitter cold as ’tis you wouldn’t swim a dozen yards. No, no, Bob, my lad, put on your duds again; we must try sum’at else.”

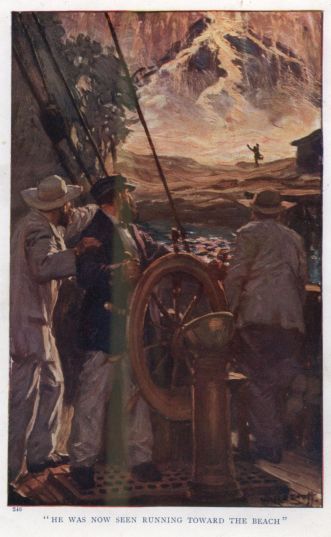

But Bob had by this time disencumbered himself of everything save a woollen under-shirt and drawers; and now, instead of doing his adopted father’s bidding, he rapidly cast off the line from the keg, and, making a bowline in the end, passed it over one shoulder and underneath the other arm. The next instant he had poised himself lightly upon the taffrail of the wildly tossing smack, and, a mighty breaker sweeping by, with comparatively smooth water behind it, without a moment’s hesitation thence plunged head-foremost into the icy sea.

The broken water leaped and tossed wildly, as if in exultation, over the spot where the brave lad had disappeared; while all hands—both those on board the smack and the people on the wreck—waited breathlessly for his reappearance on the surface. An endless time it seemed to all; and but for the rapid passage of the thin light line out over the smack’s taffrail, indicating that Bob was swimming swiftly under water, old Bill Maskell would have dreaded some dreadful mishap to his protégé; but at last a small round dark object appeared in bold relief in the midst of a sheet of foam, which gleamed dazzling white in the clear cold light of the moon.

It was Bob’s head.

“There he is!” was the exultant exclamation of every one of the smack’s crew, and then they sent forth upon the wings of the gale a ringing cheer, in which those upon the wreck faintly joined.

“Now, boys,” exclaimed old Bill, “clear away this here line behind me, some of yer; and look out another nice light handy one to bend on to it in case we wants it.”

The old man himself stood on the taffrail, paying out the line and attentively watching every heave of the plunging smack, so that Bob might not be checked in the smallest degree in his perilous passage, nor, on the other hand, be hampered by having a superabundance of line paid out behind him for the tide to act upon and drag hint away to leeward.

The distance from the smack to the wreck was but short, a mere hundred feet or so, but with the heavy surf to contend against and the line sagging and swaying in the sea behind him, it taxed Bob’s energies to their utmost limit to make any progress at all. Indeed, it appeared to him that, instead of progressing, he was, like the keg, drifting helplessly to leeward with the tide. The cold water, too, chilled him to the very marrow and seemed to completely paralyse his energies, while the relentless surf foamed over his head almost without intermission, so that he had the utmost difficulty in getting his breath. Nevertheless he fought gallantly on until, after what seemed to be an eternity of frightful exertion, he reached the side of the wreck, and grasped the rope which its occupants flung to him. He was too completely exhausted, however, to mount the side at that moment; and while he clung to the rope, regaining his breath and his strength, a mighty roller came sweeping down upon the sands, burying the smack for the moment as it rushed passed her, and then surging forward with upreared threatening crest toward the wreck.

There was a warning cry from those on board the wreck, as they saw this terrible wall of water rushing down upon them, and each seized with desperate grip whatever came nearest to hand, clinging thereto with the tenacity of despair. Bob heard the cry, saw the danger, and had just time to struggle clear of the wreck and pass under her stern when the breaker burst upon them. Blinded, stunned, and breathless, he felt himself whirled helplessly hither and thither, while a load like that of a mountain seemed to rest upon him and press him down. At last he emerged again, considerably to leeward of the wreck, but with the rope which they had thrown him still in his hands. As he gasped for breath and shook the salt water out of his eyes, something swayed against him beneath the surface—something which he knew instantly must be a human body. In a second he had it in his grasp, and, dragging it above water, found it to be the body of a child, apparently about two years old. At the same moment a powerful strain came upon the line which he held in his hand, and he had only time to take, by a rapid movement, two or three turns of it round his arm when those on the wreck began to haul him on board.

In less time than it takes to tell of it, he was dragged inboard, and lay panting and exhausted upon the steeply inclined deck of the wreck, with a curious crowd of haggard-eyed anxious men and women gathered round him. A man dressed in a fine white linen shirt and blue serge trousers (he was the master of the ship, and had given his remaining garments to shield the poor shivering, frightened children) was in the act of kneeling down by Bob’s side, apparently intending to question him, when a piercing shriek was heard, and a woman darted forward with the cry “My child! my child!” and seized the body which Bob had brought on board and still held in his arms.

This incident created a diversion; and Bob speedily recovering the use of his faculties, and rapidly explaining the intentions of those on board the smack, a strong hawser was soon stretched from the Seamew to the wreck, a “bo’sun’s chair” slung thereto; and the transport of the shipwrecked crew and passengers at once commenced.

The journey, though short, was fraught with the utmost peril; for it being impossible to keep the hawser strained taut, the poor unfortunate wretches had to be dragged through rather than over the surf; and when all was ready the women, who were of course to go first, found their courage fail them. In vain were they remonstrated with; in vain were they reminded that every second as it flew bore mayhap a human life into eternity with it; the sight of the wild surf into which the hawser momentarily plunged completely unnerved them, and they one and all declared that, rather than face the terrible risk, they would die where they were.

At last Bob, who knew as well as, if not better than, anyone on board the importance of celerity, whispered a word or two in the captain’s ear. The latter nodded approvingly; and Bob at once got into the “chair,” some of the ship’s crew rapidly but securely lashing him there, in obedience to their captain’s order. When all was ready the skipper, approaching the terrified group of women, took one of their children tenderly in his arms, and, before the unhappy mother could realise what was about to take place, handed it to Bob.

The signal was instantly given to those on board the smack, who hauled swiftly upon the hauling-line; Bob went swaying off the gunwale, with his precious charge encircled safely in his arms, and in another moment was buried in a mountain of broken water which rushed foaming past. Only to reappear instantly afterwards, however; and in a very brief space of time he and his charge had safely reached the smack. The little one was handed over to the rough but tender-hearted fishermen; but Bob, seeing that he could be useful there, at once returned to the wreck.

There was now no further difficulty with the women. The mother whose child had already made the adventurous passage was frantic to rejoin her baby, and eagerly placed herself in the chair as soon as Bob vacated it. She, too, accomplished the journey in safety; and then the others, taking courage once more from her example, quietly took their turn, some carrying their children with them, while others preferred to confide their darlings to Bob, or to one of the seamen, for the dreadful passage through the wintry sea.

The women once safe, the men made short work of it; and in little over two hours twenty-five souls—the survivors of a company of passengers and crew numbering in all forty-two—were safely transferred to the Seamew, which, slipping her cable, at once bore away with her precious freight for Brightlingsea.

Chapter Two.

The “Betsy Jane.”

Once fairly out of the breakers the fishermen—at great risk to their little craft—opened the companion leading down into the Seamew’s tiny after-cabin, and the poor souls from the wreck were conveyed below, out of the reach of the bitter blast and the incessant showers of icy spray. Bob and two or three others of the smack’s crew also went below and busied themselves in lighting a fire, routing out such blankets and wraps of various kinds as happened to be on board, and in other ways doing what they could to ameliorate the deplorable condition of their guests. Fortunately the wind, dead against them on the way out, was fair for the homeward run, and the Seamew rushed through the water at a rate which caused “Dicky” Bird to exclaim—

“Blest if the little huzzy don’t seem to know as they poor innercent babbies’ lives depends on their gettin’ into mother Salmon’s hands and atween her hot blankets within the next hour! Just see how she’s smoking through it.”

Very soon the “Middle” lightship was reached, and as the smack swept past old Bill shouted to the light-keepers the joyful news of the rescue. A few minutes afterwards three rockets were sent up at short intervals from the smack, as an intimation to “mother” Salmon that her good services were required; and in due time the gallant little smack found her way back to her moorings in the creek.

The anchor was scarcely let go when three or four boats dashed alongside, and “Well, Bill, old man, what luck?” was the general question.

“Five-and-twenty, thank God, men, women, and children,” responded old Bill. “Did ye catch sight of our rockets, boys!”

“Ay, ay; never fear. And ‘mother’ ashore there, she’s never turned-in at all this blessed night. Said as she was sure you’d bring somebody in; and a rare rousing fire she’s got roaring up the chimbley, and blankets, no end; all the beds made up and warmed, and everything ready, down to a rattlin’ good hot supper; so let’s have these poor souls up on deck (you’ve got ’em below, I s’pose), and get ’em ashore; they must be pretty nigh froze to death, I should think.”

At Bill’s cheery summons the survivors from the wreck staggered to the smack’s deck—their cramped and frozen limbs scarcely able to sustain them—and the bewildered glances which they cast round them at the scarcely ruffled waters of the creek glancing in the clear frosty moonlight, with the fishing smacks and other small craft riding cosily at anchor on either side, the straggling village of Brightlingsea within a stone’s throw—a tiny light still twinkling here and there in the cottage windows, and a perfect blaze of ruddy light streaming from the windows of the “Anchor,” and flooding the road with its cheerful radiance—the bewildered glances with which they regarded this scene, I say, showed that even now they were scarcely able to realise the fact of their deliverance.

But they were not left very long in doubt about it. As they emerged with slow and painful steps from the smack’s tiny companion, strong arms seized them, all enwrapped in blankets as they were, and quickly but tenderly passed them over the side into the small boats which had come off from the shore for them. Then, as each boat received its complement, “Shove off” was the word; the bending oars churned the water into miniature whirlpools, and with a dozen powerful strokes the boat was sent half her length high and dry upon the shore. Then strong arms once more raised the sufferers, and quickly bore them within the wide-open portal of the hospitable “Anchor,” where “mother” Salmon waited to receive them.

“Eh, goodness sakes alive!” she exclaimed, as the first man appeared within the flood of light which streamed from the “Anchor” windows. “You, Sam; you don’t mean to say as there’s women amongst ’em.”

“Ah! that there is, mother,” panted Sam, “and children—poor little helpless babbies, some on ’em, too.”

The quick warm tears of womanly sympathy instantly flashed into the worthy woman’s eyes; but she was not one prone to much indulgence in sentiment, particularly at a time like the present; so instead of lifting up her hands and giving expression to her pity in words, she faced sharply round upon the maids who were crowding forward, with the curiosity of their sex, to catch a first glimpse of the strangers, and exclaimed—

“Now then, you idle huzzies, what d’ye mean by blocking up the passage so that a body can get neither in nor out? D’ye want these poor souls to be quite froze to death before you lets ’em in? You, Em’ly, be off to Number 4 and run the warmin’ pan through the bed, and give the fire a good stir. Emma, do wake up, child, and take a couple of buckets of hot water up to Number 4, and put ’em in the bath. Run, Mary Jane, for your life, and see if the fire in Number 7 is burning properly; and you, Susan, be off and turn down all the beds.”

The maids rushed off to their several duties like startled deer, while the mistress turned to Sam and directed him to convey his burden to Number 4, herself leading the way.

A number of women, the mothers and wives of the fishermen, had gathered at the “Anchor” as soon as it was known that the smack had gone out to a wreck, in order that they might be at hand to render any assistance which might be required. They were all collected in the bar-parlour; and two of them now rose, in obedience to “mother” Salmon’s summons, and following her upstairs, took over from Sam their patient; and, shutting the door, lost not a moment in applying such restoratives and adopting such measures as their experience taught them would be most likely to prove beneficial.

The rest of the survivors speedily followed; the women and children being promptly conveyed to the rooms already prepared for them; but the men, for the most part, proved to be very little the worse for their exposure, seeming to need for their restoration a good hot supper more than anything else; and this contingency also having by “mother” Salmon’s experience and foresight been provided for, the rescued and their rescuers were soon seated together at the same table busily engaged in the endeavour to restore their exhausted energies.

One man only of the entire party seemed unable to do justice to the meal spread before him, and this was the master of the wrecked ship. He seated himself indeed at the table, and made an effort to eat and drink, but his thoughts were evidently elsewhere. He could not settle comfortably down to his meal, but kept gliding softly out of the room, to glide as softly back again after an absence of a few minutes, when he would abstractedly swallow a mouthful or two, and then glide out once more. At length, after a somewhat longer absence than before, he returned to the room in which the meal was being discussed, the look of care and anxiety on his face replaced by an expression of almost overwhelming joy, and, walking up to Bob, somewhat astonished that individual by exclaiming—

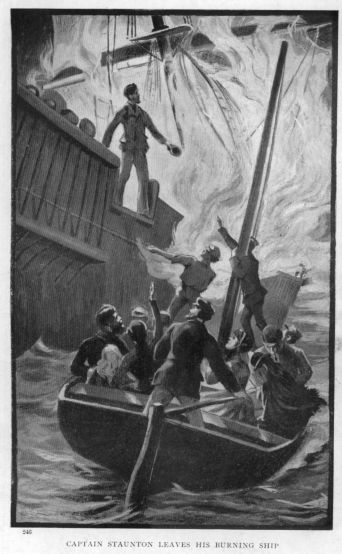

“Young man, let me without further delay tender you and your brave comrades my most hearty thanks for the rescue of my passengers, my crew, and myself from a situation of deadly peril, a rescue which was only effected at very great hazard to yourselves, and which was successfully accomplished mainly—I am sure your comrades will join me in saying—through your indomitable courage and perseverance. The debt which I owe you is one that it will be quite impossible for me ever to repay; I can merely acknowledge it and testify to the overwhelming nature of my obligation, for to your gallant behaviour, under God, I owe not only the deliverance of twenty-five human lives from a watery grave, but also the safety of my wife and only child—all, in fact, that I have left to me to make life worth living. As I have said, it will be quite impossible for me ever to cancel so heavy a debt; but what I can do I will. Your conduct shall be so represented in the proper quarter as to secure for you all the honour which such noble service demands; and, for the rest, I hope you will always remember that Captain Staunton—that is my name—will deem no service that you may require of him too great to be promptly rendered. And what I say to you especially, I say also to all your gallant comrades, who will, I hope, accept the grateful thanks which I now tender to them.”

Poor Bob blushed like a girl at these warm outspoken praises, and stammered some deprecatory remarks, which, however, were drowned by the more vigorous disclaimers of the rest of the fishermen and their somewhat noisy applause of the shipwrecked captain’s manly speech; in the midst of which commotion “mother” Salmon entered to enjoin strict silence and to announce the gratifying intelligence that all the women and children were doing well, including the skipper’s little daughter, the apparently lifeless body of whom Bob had recovered when first he boarded the wreck. A low murmur of satisfaction greeted this announcement, and then all hands fell to once more upon their supper, which was soon afterwards concluded, when old Bill and his mates, shaking hands heartily all round, retired to seek the rest which they had so well-earned, while the shipwrecked men were disposed of as well as circumstances would allow in the few remaining unappropriated bed-rooms of the hospitable “Anchor.”

By noon next day the shipwrecked party had all so far recovered that they were able to set out on the journey to their several homes. Captain Staunton sought out old Bill and arranged with him respecting the salvage of the wrecked ship’s cargo, after which he handed the veteran fisherman, as remuneration for services already rendered, a draft upon the owners of the Diadem, which more than satisfied the smack’s crew for all their perils and exertions of the previous night. He then left for London to perform the unpleasant duty of reporting to his owners the loss of their ship, mentioning, before he left, the probability of his speedy return to personally superintend the salvage operations. In bidding adieu to Bob, who happened to be present while the final arrangements with old Bill were being made, Captain Staunton remarked to him—

“I have been thinking a great deal about you, my lad. You are a fine gallant young fellow, and it seems to me it would be a very great pity for you to waste your life in pursuit of the arduous and unprofitable occupation of fishing. What say you? Would you like to take to the sea as a profession? If so, let me know. I owe you a very heavy debt, as I have already said, and nothing would afford me greater pleasure than to repay you, as far as possible, by personally undertaking your training, and afterwards using what little interest I possess to advance you in your career. Think the matter over, and consult with your father upon it”—he was not then aware of poor Bob’s peculiar position—“and let me know your decision when I return. Now, once more, good-bye for the present.”

The weather having moderated by the next day, the Seamew’s crew commenced salvage operations at the wreck, and for more than a week all hands were so busy, early and late, that Bob had literally no time to think about, much less to consult with old Bill respecting, Captain Staunton’s proposal.

On the third day the chief mate of the Diadem appeared at Brightlingsea, having been sent down by the owners to superintend the work at the wreck. He announced that he had been sent instead of Captain Staunton, in consequence of the appointment of the latter by his owners to the command of a fine new ship then loading in the London Docks for Australia. It appeared that Captain Staunton stood so high in the estimation of his employers, and possessed such a thoroughly-established reputation for skill and sobriety that, notwithstanding his recent misfortune, there had been no hesitation about employing him again. A few days later a letter came from the captain himself to Bob confirming this intelligence, and stating that he had then a vacancy for his young friend if he chose to fill it.

Bob, however, as has already been remarked, was at the time too busy to give the matter proper consideration, so he wrote back saying as much, and hinting that perhaps on the return of the ship to England he might be glad to have a repetition of the offer.

To this letter a reply soon came, announcing the immediate departure of the ship, and containing a specific offer to receive Bob on board in the capacity of apprentice on her next voyage.

The idea of taking to the sea as a profession was so thoroughly novel to Bob that he had at first some little difficulty in realising all that it meant. Hitherto he had had no other intention or ambition than to potter about in a fishing smack with old Bill, living a hard life, earning a precarious subsistence, and possibly, if exceptionally fortunate, at some period in the far-distant future, attaining to the ownership of a smack himself. But a month or two later on, when all had been saved that it was possible to save from the wreck, and when nothing remained of the once fine ship but a few shattered timbers embedded in the sand, and showing at low water like the fragment of a skeleton of some leviathan; when Bob found time to fully discuss the matter with old Bill Maskell and his mates, these worthies painted the advantages of a regular seaman’s life over those of the mere fisherman in such glowing colours, and dwelt so enthusiastically upon the prospects which would surely open out before our hero under the patronage of a man like Captain Staunton, that Bob soon made up his mind to accept the captain’s offer and join him on his return to England.

Having once come to this decision the lad was all impatience for the time to arrive when he might embark upon his career. As it is with most lads, so it was with him, the prospect of a complete change in his mode of life was full of pleasurable excitement; and perhaps it was only natural that, now he had decided to forsake it, the monotonous humdrum fisher’s life became almost unbearably irksome to him. Old Bill Maskell was not slow to observe this, and with the unselfishness which was so eminently characteristic of him, though he loved the lad as his own soul, he decided to shorten for him as far as possible the weary time of waiting, and send him away at once.

Accordingly, on the first opportunity that presented itself, he remarked to Bob—

“I say, boy, I’ve been turnin’ matters over in my mind a bit, and it seems to me as a v’yage or two in a coaster ’d do you a power o’ good afore you ships aboard a ‘South-Spainer.’ You’re as handy a lad as a man need wish to be shipmates with, aboard a fore-and-aft-rigged craft; but you ought to know some’at about square-rigged vessels too afore you sails foreign. Now, what d’ye say to a trip or two in a collier brig, just to larn the ropes like, eh?”

Note: “South-Spainer”—A term frequently employed by seamen to designate a foreign-going ship, especially one sailing to southern waters.—H.C.

Life on board a collier is not, as a rule, a condition of unalloyed felicity; but Bob was happily, or unhappily, ignorant of this; the suggestion conveyed to his mind only the idea of change, and his face lighted joyfully up at his benefactor’s proposition, to which he at once eagerly assented.

Bob’s slender wardrobe was accordingly at once overhauled and put into a condition of thorough repair; Bill, meantime, employing himself laboriously in an effort to ascertain, through the medium of a voluminous correspondence, the whereabouts of an old friend of his—last heard of by the said Bill as in command of a collier brig—with a view to the securing for Bob a berth as “ordinary seaman” under a “skipper” of whom Bill knew something, and who could be trusted to treat the lad well.

Old Bill’s labours were at length rewarded with success, “Captain”—as he loved to be styled—Turnbull’s address in London being definitely ascertained, together with the gratifying intelligence that he still retained the command of the Betsy Jane.

Matters having progressed thus far satisfactorily, old Bill’s next business was to write to “Captain” Turnbull, asking him if he could receive Bob on board; and in about a month’s time a favourable answer was received, naming a day upon which Bob was to run up to London and sign articles.

Bob’s departure from Brightlingsea was regarded by his numerous friends in the village quite in the light of an event; and when the morning came, and with it the market-cart which was to convey him and his belongings, together with old Bill, to Colchester, where they were to take train to London, nearly all the fishermen in the place, to say nothing of their wives and little ones, turned out to say farewell.

The journey was accomplished in safety and without adventure; and shortly after noon Bill and Bob found themselves threading their way through the narrow crowded streets to the “captain’s” address, somewhere in the neighbourhood of Wapping.

On reaching the house the gallant skipper was found to be at home, in the act of partaking, together with his wife and family, of the mid-day meal, which on that occasion happened to be composed of “pickled pork and taturs.” Old Bill and Bob were gruffly but cordially invited to join the family circle, which they did; Bob making a thoroughly hearty meal, quite unmoved by the coquettish endeavours of Miss Turnbull, a stout, good-tempered, but not particularly beautiful damsel of some seventeen summers, to attract the attention and excite the admiration of “pa’s handsome new sailor.”

“Captain” Turnbull proved to be a very stout but not very tall man, with a somewhat vacant expression of feature, and a singular habit of looking fixedly and in apparent amazement for a full minute at anyone who happened to address him. These, with a slow ponderous movement of body, a fixed belief in his own infallibility, and an equally firm belief in the unsurpassed perfections of the Betsy Jane, were his chief characteristics; and as he is destined to figure for a very brief period only in the pages of the present history, we need not analyse him any further.

After dinner had been duly discussed, together with a glass of grog—so far at least as the “captain,” his wife, and old Bill were concerned—our two friends were invited by the proud commander to pay a visit of inspection to the Betsy Jane. That venerable craft proved to be lying in the stream, the outside vessel of a number of similar craft moored in a tier, head and stern, to great slimy buoys, laid down as permanent moorings in the river. A wherry was engaged by the skipper, for which old Bill paid when the time of settlement arrived, the “captain” being apparently unconscious of the fact that payment was necessary, and the three proceeded on board. The brig turned out to be about as bad a specimen of her class as could well be met with—old, rotten, leaky, and dirty beyond all power of description. Nevertheless her skipper waxed so astonishingly eloquent when he began to speak her praises, that the idea never seemed to occur to either Bill or Bob that to venture to sea in her would be simply tempting Providence, and it was consequently soon arranged that our hero was to sign articles, nominally as an ordinary seaman, but, in consideration of his ignorance of square-rigged craft, to receive only the pay of a boy.

This point being settled the party returned to the shore, old Bill and Bob going for a saunter through some of the principal streets, to enjoy the cheap but rare luxury, to simple country people like themselves, of a look into the shop windows, with the understanding that they were to accept the hospitality of the Turnbull mansion until the time for sailing should arrive on the morrow.

Bob wished very much to visit one of the theatres that evening—a theatre being a place of entertainment which up to that time he had never had an opportunity of entering; but old Bill, anxious to cultivate, on Bob’s behalf, the goodwill of the Betsy Jane’s commander, thought it would be wiser to spend the evening with that worthy. This arrangement was accordingly carried out, the “best parlour” being thrown open by Mrs Turnbull for the occasion. Miss Turnbull and Miss Jemima Turnbull contributed in turn their share toward the evening’s entertainment by singing “Hearts of Oak,” “The Bay of Biscay,” “Then farewell my trim-built wherry,” and other songs of a similar character, to a somewhat uncertain accompaniment upon a discordant jangling old piano—the chief merit of which was that a large proportion of its notes were dumb. Their gallant father meanwhile sipped his grog and puffed away at his “church-warden” in a high-backed uncomfortable-looking chair in a corner near the fire, utterly sunk, apparently, in a fit of the most profound abstraction, from which he would occasionally start without the slightest warning, and in a most alarming manner, to bellow out—generally at the wrong time and to the wrong tune—something which his guests were expected to regard as a chorus. The chorus ended he would again sink, like a stone, as abruptly back into his inner consciousness as he had emerged from it. So passed the evening, without the slightest pretence at conversation, though both Bill and Bob made several determined efforts to start a topic; and so, as music, even of the kind performed by the Misses Turnbull, palls after a time, about eleven p.m. old Bill hinted at fatigue from the unusual exertions of the day, proposed retirement, and, with Bob, was shown to the room wherein was located the “shakedown” offered them by the hospitable skipper. The “shakedown” proved to be in reality two fair-sized beds, which would have been very comfortable had they been much cleaner than they were, and our two friends enjoyed a very fair night’s rest.

Bob duly signed articles on the following morning, and then, in company with his shipmates, proceeded on board the Betsy Jane. Captain Turnbull put in an appearance about an hour afterwards, when the order was given to unmoor ship, and the brig began to drop down the river with the tide. Toward evening a fine fair wind sprang up, and the Betsy Jane, being only in ballast, then began to travel at a rate which threw her commander into an indescribable state of ecstasy. The voyage was accomplished without the occurrence of any incident worth recording, and in something like a week from the date of sailing from London, Bob found himself at Shields, with the brig under a coal-drop loading again for the Thames.

Some half a dozen similarly uneventful voyages to the Tyne and back to London were made by Bob in the Betsy Jane. The life of a seaman on board a collier is usually of a very monotonous character, without a single attractive feature in it—unless, maybe, that it admits of frequent short sojourns at home—and Bob’s period of service under Captain Turnbull might have been dismissed with the mere mention of the circumstance, but for the incident which terminated that service.

It occurred on the sixth voyage which Bob had made in the Betsy Jane. The brig had sailed from the Tyne, loaded with coals for London as usual, with a westerly wind, which, however, shortly afterwards backed to S.S.W., with a rapidly falling barometer. The appearance of the weather grew very threatening, which, coupled with the facts that the craft was old, weak, and a notoriously poor sailer with the wind anywhere but on her quarter, seemed to suggest, as the most prudent course under the circumstances, a return to the port they had just left. The mate, after many uneasy glances to windward, turned to his superior officer, who was sitting by the companion placidly smoking, and proposed this.

The skipper slowly withdrew his pipe from his mouth, and, after regarding his mate for some moments, as though that individual were a perfect stranger who had suddenly and unaccountably made his appearance on board, ejaculated—

“Why?”

“Well, I’m afeard we’re goin’ to have a very dirty night on it,” was the reply.

“Umph!” was the captain’s only commentary, after which he resumed his pipe, and seemed inclined to doze.

Meanwhile the wind, which had hitherto been of the strength of a fair working breeze, rapidly increased in force, with occasional sharp squalls preceded by heavy showers of rain, while the threatening aspect of the weather grew every moment more unmistakable. The brig was under topgallant-sails, tearing and thrashing through the short choppy sea in a way which sent the spray flying continuously in dense clouds in over her bluff bows, until her decks were mid-leg deep in water, and her stumpy topgallant-masts where whipping about aloft to such an extent that they threatened momentarily to snap off short at the caps. It was not considered etiquette on board the Betsy Jane for the mate to issue an order while the captain had the watch, as was the case on the present occasion; but seeing a heavy squall approaching he now waived etiquette for the nonce and shouted—

“Stand by your to’gallan’ halliards! Let go and clew up! Haul down the jib.”

“Eh!” said the skipper, deliberately removing his pipe from his mouth, and looking around him in the greatest apparent astonishment.

Down rushed the squall, howling and whistling through the rigging, careening the brig until the water spouted up through her scuppers, and causing the gear aloft to crack and surge ominously.

“Let fly the tops’l halliards, fore and main!” yelled the mate.

The men leapt to their posts, the ropes rattled through the blocks, the yards slid down the top-masts until they rested on the caps, and with a terrific thrashing and fluttering of canvas the brig rose to a more upright position, saving her spars by a mere hair’s-breadth.

Captain Turnbull rose slowly to his feet, and, advancing to where the mate stood near the main-rigging, tapped that individual softly on the shoulder with his pipe-stem.

The mate turned round.

Captain Turnbull looked fixedly at him for some moments as though he thought he recognised him, but was not quite sure, and then observed—

“I say, are you the cap’n of this ship?”

“No, sir,” replied the mate.

“Very well, then,” retorted the skipper, “don’t you do it agen.” Then to the crew, all of whom were by this time on deck, “Bowse down yer reef-tackles and double-reef the taups’ls, then stow the mains’l.”

“Don’t you think we’d better run back to the Tyne, afore we drops too far to leeward to fetch it?” inquired the mate.

The captain looked at him in his characteristic fashion for a full minute; inquired, “Are you the cap’n of this ship?”

And then, without waiting for a reply, replaced his pipe between his lips, staggered back to his seat, and contemplatively resumed his smoking.

The fact is that Captain Turnbull was actually pondering upon the advisability of putting back when the mate unluckily suggested the adoption of such a course. Dull and inert as was the skipper of the Betsy Jane, he was by no means an unskilled seaman. The fact that he had safely navigated the crazy old craft to and fro between the Thames and the Tyne, in fair weather and foul, for so many years, was sufficient evidence of this. He had duly marked the portentous aspect of the weather, and was debating within himself the question whether he should put back, or whether he should keep on and take his chance of weathering the gale, as he had already weathered many others. Unfortunately his mind was, like himself, rather heavy and slow in action, and he had not nearly completed the process of “making it up” when the mate offered his suggestion. That settled the question at once. The “captain” was as obstinate and unmanageable a man as ever breathed, and it was only necessary for some one to suggest a course and he would at once adopt a line of action in direct opposition to it. Hence his resolve to remain at sea in the present instance.

Having finally committed himself to this course, however, he braced himself together for the coming conflict with the elements, and when the watch below was called at eight bells all hands were put to the task of placing the ship under thoroughly snug canvas before the relieved watch was permitted to go below. The brig was normally in so leaky a condition that she regularly required pumping out every two hours when under canvas, a task which in ordinary weather usually occupied some ten minutes. If the weather was stormy it took somewhat longer to make the pumps suck, and, accordingly, no one was very much surprised when, on the watch going to the pumps just before eight bells, an honest quarter of an hour was consumed in freeing the old craft from the water which had drained in here and there during the last two hours. Their task at length accomplished the men in the skipper’s watch, of whom Bob was one, lost no time in tumbling into their berths “all standing,” where they soon forgot their wet and miserable condition in profound sleep. Captain Turnbull, contrary to his usual custom, at the conclusion of his watch retired from the deck only to change his wet garments and envelop himself in a suit of very old and very leaky oilskins, when he resumed once more his favourite seat by the companion, stolidly resolved to watch the gale out, let it last as long as it might.

Note: “All standing” in this case means without removing any of their clothing.

A gale in good truth it had by this time become; the wind howling furiously through the brig’s rigging, and threatening momentarily to blow her old worn and patched canvas out of the bolt-ropes. The dull leaden-coloured ragged clouds raced tumultuously athwart the moonlit sky; now veiling the scene in deep and gloomy shadow as they swept across the moon’s disc, and anon opening out for an instant to flood the brig, the sea, and themselves in the glory of the silver rays. The caps of the waves, torn off by the wind, filled the air with a dense salt rain, which every now and then gleamed up astern with all the magical beauty of the lunar rainbow; but though the scene would doubtless have ravished the soul of an artist by its weird splendour, it is probable that such an individual would have wished for a more comfortable view-point than the deck of the Betsy Jane. That craft was now rolling and pitching heavily in the short choppy sea, smothering herself with spray everywhere forward of the fore-mast, filling her decks with water, which swished and surged restlessly about and in over the men’s boot-tops with every motion of the vessel, and straining herself until the noise of her creaking timbers and bulkheads rivalled the shriek of the gale.

At four bells the Betsy Jane gave the watch just half an hour of steady work to pump her out.

This task at length ended, the men, wet and tired, sought such partial shelter as was afforded by the lee of the longboat where she stood over the main hatch, the lee side of the galley, or peradventure the interior of the same, and there enjoyed such forgetfulness of their discomfort as could be obtained in a weazel-like surreptitious sleep—with one eye open, on watch for the possible approach of the skipper or mate. All of them, that is, except one, who called himself the look-out. This man, well cased in oilskin, stationed himself at the bowsprit-end—which being just beyond the reach of the spray from the bows, was possibly as dry a place as there was throughout the ship, excepting, perhaps, her cabin—and sitting astride the spar and wedging his back firmly in between the two parts of the double fore-stay, found himself so comfortably situated that in less than five minutes he was sound asleep.

Captain Turnbull, meanwhile, occupied his favourite seat near the companion, and smoked contemplatively, while the mate staggered fore and aft from the main-mast to the taffrail, on the weather side of the deck, it being his watch.

Suddenly the mate stopped short in his walk, and the skipper ejaculated “Umph!”

The attention of both had at the same moment been arrested by something peculiar in the motion of the brig.

“Sound the pumps,” observed the skipper, apparently addressing the moon, which at that moment gleamed brightly forth from behind a heavy cloud.

The mate took the sounding-rod, and, first of all drying it and the line carefully, dropped it down the pump-well. Hauling it up again, he took it aft to the binnacle, the somewhat feeble light from which showed that the entire rod and a portion of the line was wet.

“More’n three feet water in th’ hold!” exclaimed the mate.

“Call the hands,” remarked Captain Turnbull, directing his voice down the companion as though he were speaking to some one in the cabin.

The crew soon mustered at the pumps, and manned them both, relieving each other every ten minutes.

After three-quarters of an hour of vigorous pumping there was as little sign of the pumps sucking as at the commencement.

They were then again sounded, with the result that the crew appeared to have gained something like three inches upon the leak.

The men accordingly resumed pumping, in a half-hearted sort of way, however, which seemed to say that they had no very great hope of freeing the ship.

Another hour passed, and the pumps were again sounded.

“Three foot ten! The leak gains on us!” proclaimed the mate in a low voice, as he and the skipper bent together over the rod at the binnacle-lamp.

Shortly afterwards the wheel was relieved; the man who had been steering taking at the pumps the place of the one who had relieved him.

A hurried consultation immediately took place amongst the men; and presently one of them walked aft to where the skipper was seated, and remarked—

“The chaps is sayin’, skipper, as how they thinks the best thing we can do is to ‘up stick’ and run for the nearest port.”

The skipper looked inquiringly at the man for so long a time that the fellow grew quite disconcerted; after which he shook his head hopelessly, as though he had been addressed in some strange and utterly unintelligible language, and, withdrawing his pipe from his mouth, pointed solemnly in the direction of the pumps.

The man took the hint and retired.

The mate, who had witnessed this curious interview, then passed over to the lee side of the deck, and steadying himself by the companion, bent down and said in a low voice to his superior—

“After all, cap’n, Tom’s about right; the old barkie ’ll go down under our feet unless we can get her in somewheres pretty soon.”

Captain Turnbull, with his hands resting on his knees, and his extinguished pipe placed bowl downwards between his teeth, regarded his mate with the blank astonishment we may imagine in one who believes he at last actually sees a genuine ghost, and finally gasped in sepulchral tones—

“Are you the cap’n of this ship?”

The mate knew that, after this, there was nothing more to be said, so he walked forward to the pumps, and, by voice and example, strove to animate the men to more earnest efforts.

Another hour passed. The pumps were again sounded; and now it became evident that the leak was rapidly gaining. The general opinion of the men was that the labouring of the brig in the short sea had strained her so seriously as to open more or less all her seams, or that a butt had started. They pumped away for another hour; and then, feeling pretty well fagged out, and finding on trial that the leak gained upon them with increased rapidity, they left the pumps, and began to clear away the boats. The mate made a strong effort to persuade them to return to their duty, but, being himself by that time convinced of the impossibility of saving the ship, he was unsuccessful. Seeing this, he, too, retired below, and hastily bundling together his own traps and those of the skipper, brought them on deck and placed them in the stern-sheets of the longboat. The men had by this time brought their bags and chests on deck; and finding that the brig had meanwhile settled so deep in the water that her deck was awash, they lost no time in getting their belongings, as well as a bag or two of bread and a couple of breakers of water, into the boat. The Betsy Jane was then hove-to; and as she was rolling far too heavily to render it possible to hoist the boat out, the men proceeded to knock the brig’s bulwarks away on the lee side, with the intention of launching her off the deck. This task they at last accomplished, aided materially therein by the sea, which by this time was washing heavily across the deck. The crew then passed into her one by one—Bob among the rest—and made their final preparations for leaving the devoted brig.

Seeing that all was ready the mate then went up to the skipper, who still maintained his position on his favourite seat, and said—

“Come, skipper, we’re only waitin’ for you, and by all appearances we mustn’t wait very long neither.”

Captain Turnbull raised his head like one awakened from a deep sleep, glanced vacantly round the deserted decks, pulled strongly two or three times at his long-extinguished pipe, and then two tears welled slowly up into his eyes, and, overflowing the lids, rolled one down either cheek. Then he rose quietly to his feet and, with possibly the only approach to dignity which his actions had ever assumed, pointed to the boat and said—

“I’m cap’n of this ship. You go fust.” The mate needed no second bidding. He sprang to the ship’s side and stepped thence into the boat, taking his place at the tiller. Captain Turnbull, with his usual deliberation, followed.

He was no sooner in the boat than the anxious crew shoved off, and, bending to their oars, rowed as rapidly as possible away from their dangerous proximity to the sinking brig.

The short summer night was past, day had long since broken; and though the gale still blew strongly, the clouds had dispersed, and away to the eastward the sky was ablaze with the opal and delicate rose tints which immediately precede the reappearance of the sun. A few minutes later long arrowy shafts of light shot upward into the clear blue sky, and then a broad golden disc rose slowly above the wave-crests and tipped them with liquid fire. The refulgent beams flashed upon the labouring hull and grimy canvas of the brig, as she lay wallowing in the trough of the sea a quarter of a mile away, transmuting her spars and rigging into bars and threads of purest gleaming gold, and changing her for the moment into an object of dream-like beauty. The men with one accord ceased rowing to gaze upon their late home as she now glittered before their eyes in such unfamiliar aspect; and, as they did so, her bows rose high into the air, dripping with liquid gold, then sank down again slowly—slowly—lower and lower still, until, with a long graceful sliding movement, she plunged finally beneath the wave.

“There goes the old hooker to Davy Jones’ locker, sparklin’ like a di’mond—God bless her! Good-bye, old lass—good-bye!” shouted the men; and then, as she vanished from their sight, they gave three hearty cheers to her memory.

At the same time Captain Turnbull rose in the stern-sheets of the boat, and facing round in the direction of the sinking brig, solemnly lifted from his head the old fur cap which crowned his somewhat scanty locks. He saw that her last moment was at hand, and his lips quivered convulsively for an instant; then in accents of powerful emotion he burst forth into the following oration:—

“‘Then fare thee well, my old Betty Jane,

Farewell for ever and a day;

I’m bound down the river in an old steamboat,

So pull and haul, oh! pull and haul away.’

“Good-bye, old ship! A handsomer craft, a purtier sea-boat, or a smarter wessel under canvas—whether upon a taut bowline or goin’ free—never cleared out o’ the port of London. For a matter of nigh upon forty year you’ve carried me, man and boy, back’ards and for’ards in safety and comfort over these here seas; and now, like a jade, you goes and founders, a desartin’ of me in my old age. Arter a lifetime spent upon the heavin’ buzzum of the stormy ocean—‘where the winds do blow, do blow’—you’re bound to-day to y’ur last moorin’s in old Davy’s locker. Well, then, good-bye, Betsy Jane, my beauty; dear you are to me as the child of a man’s age; may y’ur old timbers find a soft and easy restin’ place in their last berth? And if it warn’t for the old ’oman and the lasses ashore there, I’d as lief go down with thee as be where I am.”

Then, as the brig disappeared, he replaced the fur cap upon his head, brushed his knotty hand impatiently across his eyes, flung his pipe bitterly into the sea, and sadly resumed his seat. A minute afterwards he looked intently skyward and exclaimed, “Give way, boys, and keep her dead afore it! I’m cap’n of this boat.”

The men, awe-stricken by the extraordinary display of deep feeling and quaint rugged eloquence which had just been wrung from their hitherto phlegmatic and taciturn skipper, stretched to their oars in dead silence, mechanically keeping the boat stern on to the sea, and so regulating her speed as to avoid the mischance of being pooped or overrun by the pursuing surges.

About mid-day—by which time the gale had broken—they sighted a schooner bound for the Thames, the master of which received them and their traps on board. Four days afterwards they landed in London; and upon receiving their wages up to the day of the Betsy Jane’s loss, dispersed to their several homes.

Chapter Three.

“Hurrah, my lads! We’re outward-bound!”

Bob returned to Brightlingsea just in the nick of time; for on the day following his arrival home, a letter reached him from Captain Staunton announcing that gentleman’s presence once more in England, and not only so, but that his ship had already discharged her inward cargo, and was loading again for Australia. He repeated his former offer, and added that he thought it would be a good plan for Bob to join at once, as he might prove of some assistance to the chief mate in receiving and taking account of their very miscellaneous cargo. Bob and old Bill consulted together, and finally came to the conclusion that there was nothing to delay the departure of the former, as his entire outfit could easily be procured in London. Bob accordingly replied to Captain Staunton’s note, naming the day but one following as that on which he would join; and on that day he duly put in an appearance.

Bill, as on the occasion when Bob joined the Betsy Jane, accompanied the lad to London. The ship was lying in the London Dock; and the first business of our two friends was to secure quarters for themselves, which they did in a comfortable enough boarding-house close to the dock-gates. They dined, and then sallied forth to take a look at the Galatea, which they found about half-way down the dock. She was a noble craft of sixteen hundred tons register, built of iron, with iron masts and yards, wire rigging, and all the most recent appliances for economising work and ensuring the safety of her passengers and crew. She was a beautiful model, and looked a regular racer all over. Her crew were comfortably berthed in a roomy house on deck forward, the fore part of which was devoted to the seamen, while the after part was occupied by the inferior officers. Captain Staunton and the chief mate had their quarters in light, spacious, nicely fitted cabins, one on each side of the foot of the saloon staircase; while the apprentices were berthed in a small deck-house just abaft the main-mast. The saloon was a splendid apartment, very elaborately fitted up in ornamental woods of several kinds, and with a great deal of carving and gilding about it. The upholstering of the saloon was of a kind seldom seen afloat except in yachts or the finest Atlantic liners; the stern-windows even being fitted with delicate lace curtains, draped over silken hangings. Eight berths, four on each side of the ship, afforded accommodation for sixteen passengers. These were located just outside the saloon, and the space between them formed a passage leading from the foot of the staircase to the saloon doors.

Bill and Bob had to find out all these things for themselves, the mate, at the moment of their arrival on board, being the only person present belonging to the ship, and he was so busy receiving cargo that he could scarcely find time to speak to them. On being told who they were, he simply said to Bob—

“All right, young ’un; Captain Staunton has told me all about you, and I’m very glad to see you. But I haven’t time even to be civil just now, so just take a look round the ship by yourselves, will you? I expect the skipper aboard before long, and he’ll do the honours.”

In about half an hour afterwards Captain Staunton made his appearance, and, hearing that Bill and Bob were down below aft somewhere, at once joined them in the saloon. He shook them both most heartily by the hand, and, in a few well-chosen words, expressed the gratification he felt at renewing his acquaintance with them, and at the prospect of having Bob with him.

“I have spoken to my owners concerning you,” he said to Bob, “and have obtained their permission to receive you on board as an apprentice. You will dress in uniform, and berth with the other apprentices in the after house; your duties will be light, and it will be my pride as well as my pleasure to do everything in my power to make a gentleman as well as a thorough seaman of you, and so fit you in due time to occupy such a position as the one I now hold, if not a still better one.” He suggested that Bob should sign his indentures on the following day, and then proposed that they should go at once, in a body, to see about our hero’s uniform and outfit, the whole of which, in spite of all protestation, he insisted on himself presenting to the lad.

On the following day Bob signed his indentures as proposed, and joined the ship, assisting the chief mate to receive and take account of the cargo. Four days of this work completed the loading of the vessel and the taking in of her stores; and a week from the day on which Bob first saw her, the Galatea hauled out of dock and proceeded in charge of the chief mate down the river as far as Gravesend, where her captain and passengers joined her.

It is now time to say a descriptive word or two concerning the various persons with whom our friend Bob was for some time to be so intimately associated.

Captain Staunton, as the head and chief of the little community, is entitled to the first place on the list.