Project Gutenberg's On the Genesis of Species, by St. George Mivart This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: On the Genesis of Species Author: St. George Mivart Release Date: March 14, 2007 [EBook #20818] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ON THE GENESIS OF SPECIES *** Produced by Steven Gibbs, Keith Edkins and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

ON THE

BY

ST. GEORGE MIVART, F.R.S.

[The Right of Translation and Reproduction is reserved.]

TO

F.R.S., D.C.L., ETC. ETC.

My dear Sir Henry,

In giving myself the pleasure to dedicate, as I now do, this work to you, it is not my intention to identify you with any views of my own advocated in it.

I simply avail myself of an opportunity of paying a tribute of esteem and regard to my earliest scientific friend—the first to encourage me in pursuing the study of nature.

I remain,

My dear Sir Henry,

Ever faithfully yours,

ST. GEORGE MIVART.

7, North Bank, Regent's Park,

December 8, 1870.

INTRODUCTORY

The problem of the genesis of species stated.—Nature of its probable solution.—Importance of the question.—Position here defended.—Statement of the Darwinian Theory.—Its applicability to details of geographical distribution; to rudimentary structures; to homology; to mimicry, &c.—Consequent utility of the theory.—Its wide acceptance.—Reasons for this other than, and in addition to, its scientific value. Its simplicity.—Its bearing on religious questions.—Odium theologicum and odium antitheologicum.—The antagonism supposed by many to exist between it and theology neither necessary nor universal.—Christian authorities in favour of evolution.—Mr. Darwin's "Animals and Plants under Domestication."—Difficulties of the Darwinian theory enumerated ... Page 1

THE INCOMPETENCY OF "NATURAL SELECTION" TO ACCOUNT FOR THE INCIPIENT STAGES OF USEFUL STRUCTURES.

Mr. Darwin supposes that Natural-Selection acts by slight variations.—These must be useful at once.—Difficulties as to the giraffe; as to mimicry; as to the heads of flat-fishes; as to the origin and constancy of the vertebrate, limbs; as to whalebone; as to the young kangaroo; [viii]as to sea-urchins; as to certain processes of metamorphosis; as to the mammary gland; as to certain ape characters; as to the rattlesnake and cobra; as to the process of formation of the eye and ear; as to the fully developed condition of the eye and ear; as to the voice; as to shell-fish; as to orchids; as to ants.—The necessity for the simultaneous modification of many individuals.—Summary and conclusion ... Page 23

THE CO-EXISTENCE OF CLOSELY SIMILAR STRUCTURES OF DIVERSE ORIGIN.

Chances against concordant variations.—Examples of discordant ones.—Concordant variations not unlikely on a non-Darwinian evolutionary hypothesis.—Placental and implacental mammals.—Birds and reptiles.—Independent origins of similar sense organs.—The ear.—The eye.—Other coincidences.—Causes besides Natural Selection produce concordant variations in certain geographical regions.—Causes besides Natural Selection produce concordant variations in certain zoological and botanical groups.—There are homologous parts not genetically related.—Harmony in respect of the organic and inorganic worlds.—Summary and conclusion ... Page 63

MINUTE AND GRADUAL MODIFICATIONS.

There are difficulties as to minute modifications, even if not fortuitous.—Examples of sudden and considerable modifications of different kinds.—Professor Owen's view.—Mr. Wallace.—Professor Huxley.—Objections to sudden changes.—Labyrinthodont.—Potto.—Cetacea.—As to origin of bird's wing.—Tendrils of climbing plants.—Animals once supposed to be connecting links.—Early specialization of structure.—Macrauchenia.—Glyptodon.—Sabre-toothed tiger.—Conclusion ... Page 97

AS TO SPECIFIC STABILITY.

What is meant by the phrase "specific stability;" such stability to be expected a priori, or else considerable changes at once.—Rapidly increasing difficulty of intensifying race characters; alleged causes of this phenomenon; probably an internal cause co-operates.—A certain definiteness in variations.—Mr. Darwin admits the principle of specific stability in certain cases of unequal variability.—The goose.—The peacock.—The guinea fowl.—Exceptional causes of variation under domestication.—Alleged tendency to reversion.—Instances.—Sterility of hybrids.—Prepotency of pollen of same species, but of different race.—Mortality in young gallinaceous hybrids.—A bar to intermixture exists somewhere.—Guinea-pigs.—Summary and conclusion ... Page 113

SPECIES AND TIME.

Two relations of species to time.—No evidence of past existence of minutely intermediate forms when such might be expected a priori.—Bats, Pterodactyles, Dinosauria, and Birds.—Ichthyosauria, Chelonia, and Anoura.—Horse ancestry.—Labyrinthodonts and Trilobites.—Two subdivisions of the second relation of species to time.—Sir William Thomson's views.—Probable period required for ultimate specific evolution from primitive ancestral forms.—-Geometrical increase of time required for rapidly multiplying increase of structural differences.—Proboscis monkey.—Time required for deposition of strata necessary for Darwinian evolution.—High organization of Silurian forms of life.—Absence of fossils in oldest rocks.—Summary and conclusion ... Page 128

SPECIES AND SPACE.

The geographical distribution of animals presents difficulties.—These not insurmountable in themselves; harmonize with other difficulties.—Fresh-water fishes.—Forms common to Africa and India; to Africa and [x]South America; to China and Australia; to North America and China; to New Zealand and South America; to South America and Tasmania; to South America and Australia.—Pleurodont lizards.—Insectivorous mammals.—Similarity of European and South American frogs.—Analogy between European salmon and fishes of New Zealand, &c.—An ancient Antarctic continent probable.—Other modes of accounting for facts of distribution.—Independent origin of closely similar forms.—Conclusion ... Page 144

HOMOLOGIES.

Animals made up of parts mutually related in various ways.—What homology is.—Its various kinds.—Serial homology.—Lateral homology.—Vertical homology.—Mr. Herbert Spencer's explanations.—An internal power necessary, as shown by facts of comparative anatomy.—-Of teratology.—M. St. Hilaire.—Professor Burt Wilder.—Foot-wings.—Facts of pathology.—Mr. James Paget.—Dr. William Budd.—The existence of such an internal power of individual development diminishes the improbability of an analogous law of specific origination ... Page 155

EVOLUTION AND ETHICS.

The origin of morals an inquiry not foreign to the subject of this book.—Modern utilitarian view as to that origin.—Mr. Darwin's speculation as to the origin of the abhorrence of incest.—Cause assigned by him insufficient.—Care of the aged and infirm opposed by "Natural Selection;" also self-abnegation and asceticism.—Distinctness of the ideas right and useful.—Mr. John Stuart Mill.—Insufficiency of "Natural Selection" to account for the origin of the distinction between duty and profit.—Distinction of moral acts into material and formal.—No [xi]ground for believing that formal morality exists in brutes.—Evidence that it does exist in savages.—Facility with which savages may be misunderstood.—Objections as to diversity of customs.—Mr. Button's review of Mr. Herbert Spencer.—Anticipatory character of morals.—Sir John Lubbock's explanation.—Summary and conclusion ... Page 188

PANGENESIS.

A provisional hypothesis supplementing "Natural Selection."—Statement of the hypothesis.—Difficulty as to multitude of gemmules.—As to certain modes of reproduction.—As to formations without the requisite gemmules.—Mr. Lewes and Professor Delpino.—Difficulty as to developmental force of gemmules.—As to their spontaneous fission.—Pangenesis and Vitalism.—Paradoxical reality.—Pangenesis scarcely superior to anterior hypotheses.—Buffon.—Owen.—Herbert Spencer.—Gemmules as mysterious as "physiological units."—Conclusion ... Page 208

SPECIFIC GENESIS.

Review of the statements and arguments of preceding chapters.—Cumulative argument against predominant action of "Natural Selection."—Whether anything positive as well as negative can be enunciated.—Constancy of laws of nature does not necessarily imply constancy of specific evolution.—Possible exceptional stability of existing epoch.—Probability that an internal cause of change exists.—Innate powers somewhere must be accepted.—Symbolism of molecular action under vibrating impulses. Professor Owen's statement.—Statement of the Author's view.—It avoids the difficulties which oppose "Natural Selection."—It harmonizes apparently conflicting conceptions.—Summary and conclusion ... Page 220 [xii]

THEOLOGY AND EVOLUTION.

Prejudiced opinions on the subject.—"Creation" sometimes denied from prejudice.—The unknowable.—Mr. Herbert Spencer's objections to theism; to creation.—Meanings of term "creation."—Confusion from not distinguishing between "primary" and "derivative" creation.—Mr. Darwin's objections.—Bearing of Christianity on evolution.—Supposed opposition, the result of a misconception.—Theological authority not opposed to evolution.—St. Augustin.—St. Thomas Aquinas.—Certain consequences of want of flexibility of mind.—Reason and imagination.—The first cause and demonstration.—Parallel between Christianity and natural theology.—What evolution of species is.—Professor Agassiz.—Innate powers must be recognized.—Bearing of evolution on religious belief.—Professor Huxley.—Professor Owen.—Mr. Wallace.—Mr. Darwin.—A priori conception of Divine action.—Origin of man.—Absolute creation and dogma.—Mr. Wallace's view.—A supernatural origin for man's body not necessary.—Two orders of being in man.—Two modes of origin.—Harmony of the physical, hyperphysical, and supernatural.—Reconciliation of science and religion as regards evolution.—Conclusion ... Page 243

INDEX ... Page 289

Leaf Butterfly in flight and repose (from Mr. A. Wallace's "Malay Archipelago") ... 31

Walking-Leaf Insect ... 35

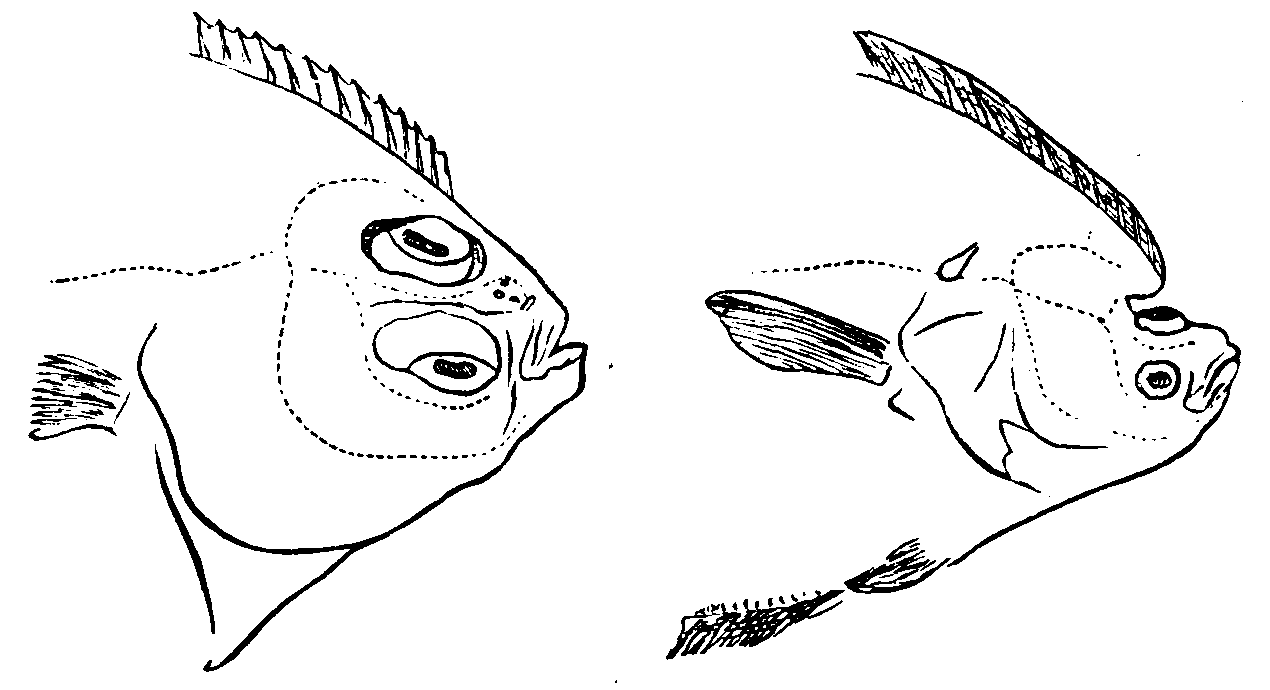

Pleuronectidæ, with the peculiarly placed eye in different positions (from Dr. Traquair's paper in Linn. Soc. Trans., 1865) ... 37, 166

Mouth of Whale (from Professor Owen's "Odontography") ... 40

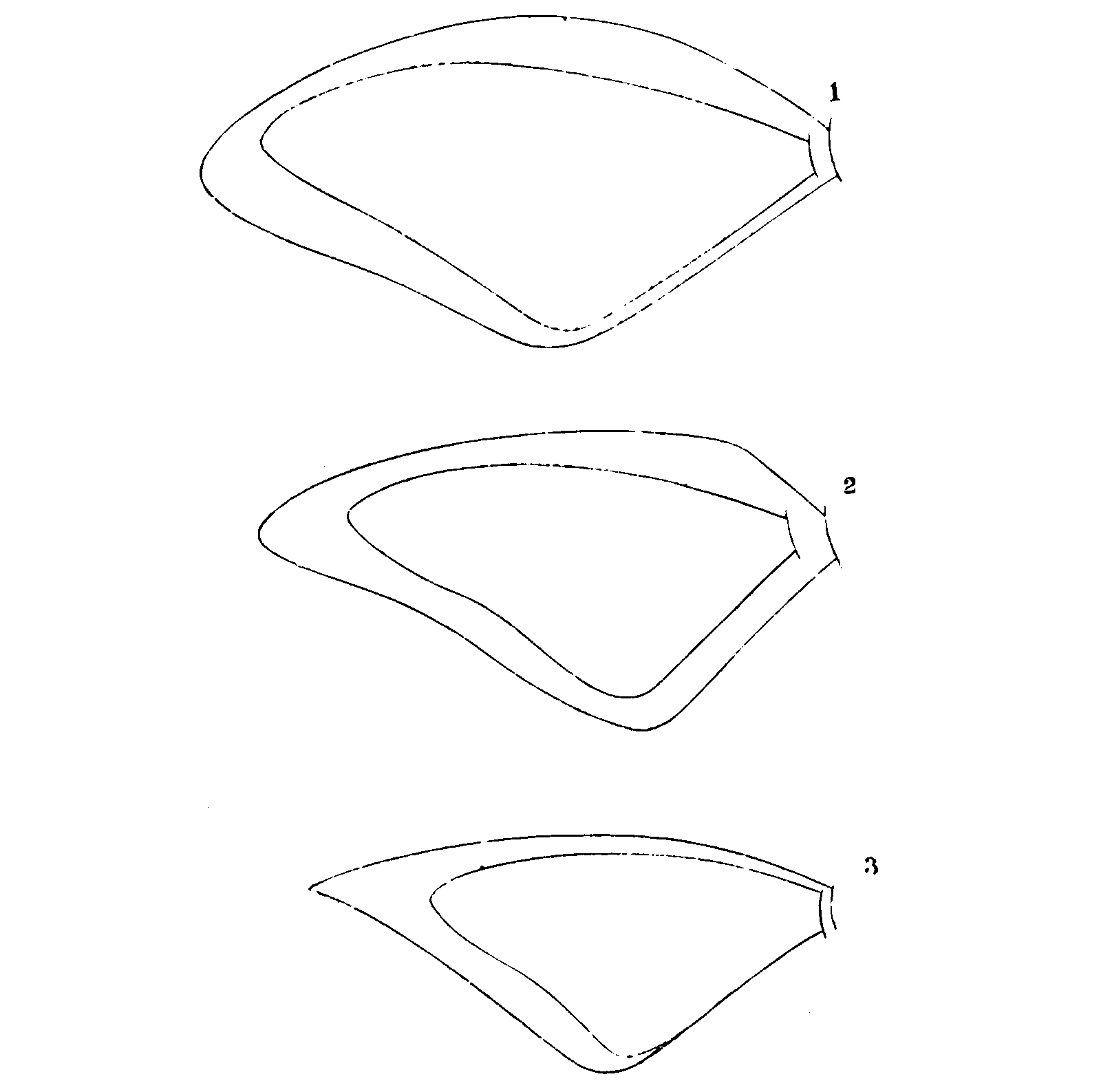

Four plates of Baleen seen obliquely from within (from Professor Owen's "Odontography") ... 41

Echinus or Sea Urchin ... 43, 167

Pedicellariæ of Echinus very much enlarged ... 44

Rattlesnake ... 49

Cobra (from Sir Andrew Smith's "Southern Africa") ... 50

Wingbones of Pterodactyle, Bat, and Bird (from Mr. Andrew Murray's "Geographical Distribution of Mammals") ... 64, 130, 157

Skeleton of Flying-Dragon ... 65, 158

Centipede (from a specimen in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons) ... 66, 159

Teeth of Urotrichus and Perameles ... 68

The Archeopteryx (from Professor Owen's "Anatomy of Vertebrata") ... 73, 132

Skeleton of Ichthyosaurus ... 78, 107, 132, 177

Cytheridea Torosa (from Messrs. Brady and Robertson's paper in Ann. and Mag. of Nat. Hist., 1870) ... 79

A Polyzoon, with Bird's-head processes ... 80

Bird's-head processes greatly enlarged ... 81

Antechimis Minutissimus and Mus Delicatulus (from Mr. Andrew Murray's "Geographical Distribution of Mammals") ... 82

Outlines of Wings of Butterflies of Celebes compared with those of allied species elsewhere ... 86

Great Shielded Grasshopper ... 89

The Six-shafted Bird of Paradise ... 90

The Long-tailed Bird of Paradise ... 91

The Red Bird of Paradise ... 92

Horned Flies ... 93

The Magnificent Bird of Paradise ... 93

(The above seven figures are from Mr. A. Wallace's "Malay Archipelago")

Much enlarged horizontal Section of the Tooth of a Labyrinthodon (from Professor Owen's "Odontography") ... 104

Hand of the Potto (from life) ... 105

Skeleton of Plesiosaurus ... 106, 133

The Aye-Aye (from Trans, of Zool. Soc.) ... 108

Dentition of Sabre-toothed Tiger (from Professor Owen's "Odontography") ... 110

Inner side of Lower Jaw of Pleurodont Lizard (from Professor Owen's "Odontography") ... 148

Solenodon (from Berlin Trans.) ... 149

Tarsal Bones of Galago and Cheirogaleus (from Proc. Zool. Soc.) ... 159

Squilla ... 160

Parts of the Skeleton of the Lobster ... 161 [xv]

Spine of Galago Allenii (from Proc. Zool. Soc.) ... 162

Vertebrae of Axolotl (from Proc. Zool. Soc.) ... 165

Annelid undergoing spontaneous fission ... 169, 211

Aard-Vark (Orycteropus capensis) ... 174

Pangolin (Manis) ... 175

Skeleton of Manus and Pes of a Tailed Batrachian (from Professor Gegenbaur's "Tarsus and Carpus") ... 178

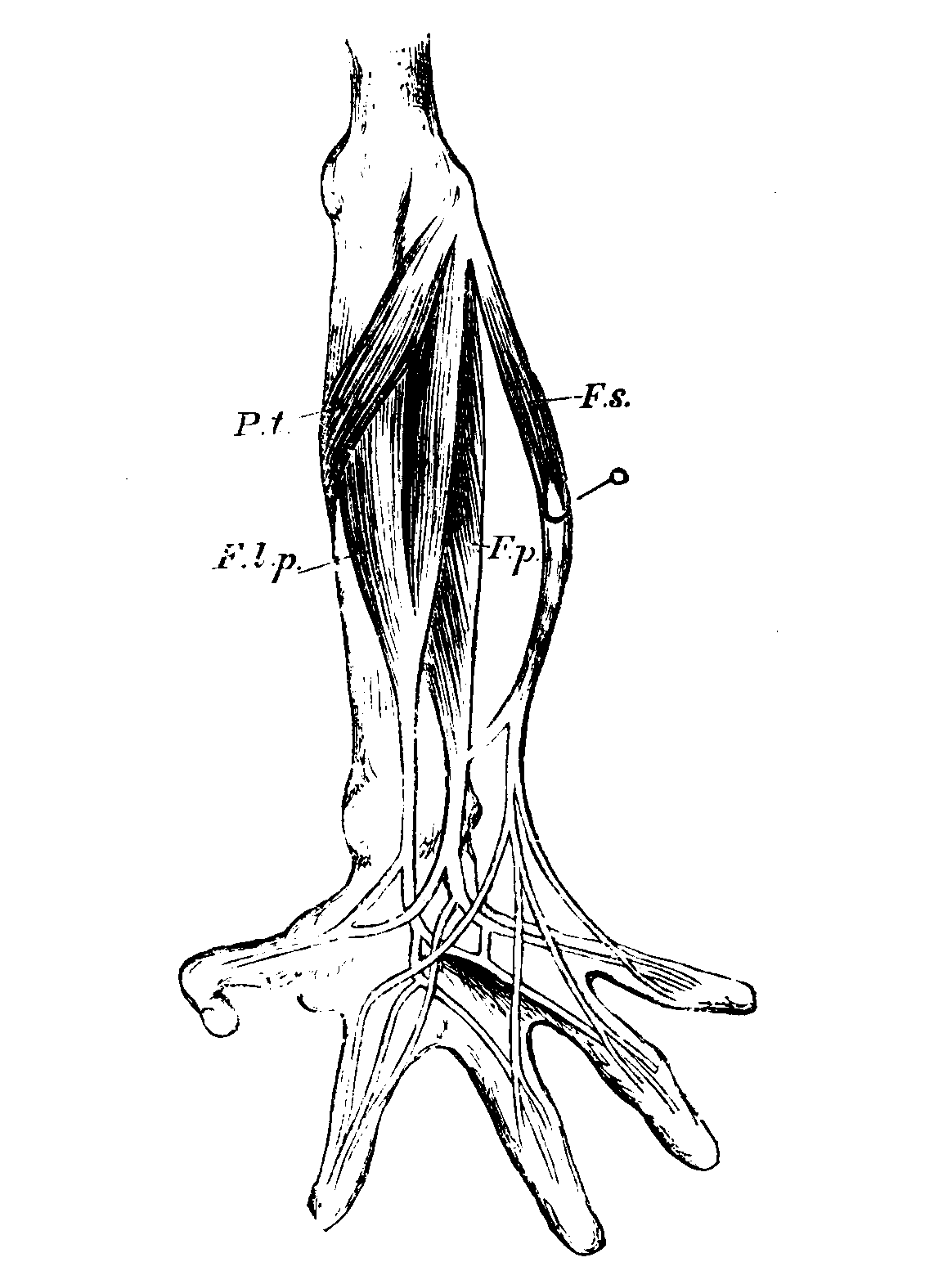

Flexor Muscles of Hand of Nycticetus (from Proc. Zool. Soc.) ... 180

The Fibres of Corti ... 279

INTRODUCTORY.

The problem of the genesis of species stated.—Nature of its probable solution.—Importance of the question.—Position here defended.—Statement of the Darwinian Theory.—Its applicability to details of geographical distribution; to rudimentary structures; to homology; to mimicry, &c.—Consequent utility of the theory.—Its wide acceptance.—Reasons for this, other than, and in addition to, its scientific value.—Its simplicity.—Its bearing on religious questions.—Odium theologicum and odium antitheologicum.—The antagonism supposed by many to exist between it and theology neither necessary nor universal.—Christian authorities in favour of evolution.—Mr. Darwin's "Animals and Plants under Domestication."—Difficulties of the Darwinian theory enumerated.

The great problem which has so long exercised the minds of naturalists, namely, that concerning the origin of different kinds of animals and plants, seems at last to be fairly on the road to receive—perhaps at no very distant future—as satisfactory a solution as it can well have.

But the problem presents peculiar difficulties. The birth of a "species" has often been compared with that of an "individual." The origin, however, of even an individual animal or plant (that which determines an embryo to evolve itself,—as, [2]e.g., a spider rather than a beetle, a rose-plant rather than a pear) is shrouded in obscurity. A fortiori must this be the case with the origin of a "species."

Moreover, the analogy between a "species" and an "individual" is a very incomplete one. The word "individual" denotes a concrete whole with a real, separate, and distinct existence. The word "species," on the other hand, denotes a peculiar congeries of characters, innate powers and qualities, and a certain nature realized indeed in individuals, but having no separate existence, except ideally as a thought in some mind.

Thus the birth of a "species" can only be compared metaphorically, and very imperfectly, with that of an "individual."

Individuals as individuals, actually and directly produce and bring forth other individuals; but no "congeries of characters" no "common nature" as such, can directly bring forth another "common nature," because, per se, it has no existence (other than ideal) apart from the individuals in which it is manifested.

The problem then is, "by what combination of natural laws does a new 'common nature' appear upon the scene of realized existence?" i.e. how is an individual embodying such new characters produced?

For the approximation we have of late made towards the solution of this problem, we are mainly indebted to the invaluable labours and active brains of Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace.

Nevertheless, important as has been the impulse and direction given by those writers to both our observations and speculations, the solution will not (if the views here advocated are correct) ultimately present that aspect and character with which it has issued from the hands of those writers.

Neither, most certainly, will that solution agree in appearance or substance with the more or less crude conceptions which have been put forth by most of the opponents of Messrs. Darwin and Wallace. [3]

Rather, judging from the more recent manifestations of thought on opposite sides, we may expect the development of some tertium quid—the resultant of forces coming from different quarters, and not coinciding in direction with any one of them.

As error is almost always partial truth, and so consists in the exaggeration or distortion of one verity by the suppression of another which qualifies and modifies the former, we may hope, by the synthesis of the truths contended for by various advocates, to arrive at the one conciliating reality.

Signs of this conciliation are not wanting: opposite scientific views, opposite philosophical conceptions, and opposite religious beliefs, are rapidly tending by their vigorous conflict to evolve such a systematic and comprehensive view of the genesis of species as will completely harmonize with the teachings of science, philosophy, and religion.

To endeavour to add one stone to this temple of concord, to try and remove a few of the misconceptions and mutual misunderstandings which oppose harmonious action, is the aim and endeavour of the present work. This aim it is hoped to attain, not by shirking difficulties, but analysing them, and by endeavouring to dig down to the common root which supports and unites diverging stems of truth.

It cannot but be a gain when the labourers in the three fields above mentioned, namely, science, philosophy, and religion, shall fully recognize this harmony. Then the energy too often spent in futile controversy, or withheld through prejudice, may be profitably and reciprocally exercised for the mutual benefit of all.

Remarkable is the rapidity with which an interest in the question of specific origination has spread. But a few years ago it scarcely occupied the minds of any but naturalists. Then the crude theory put forth by Lamarck, and by his English interpreter the author of the "Vestiges of Creation," had rather discredited than helped on a belief in organic evolution—a belief, [4]that is, in new kinds being produced from older ones by the ordinary and constant operation of natural laws. Now, however, this belief is widely diffused. Indeed, there are few drawing-rooms where it is not the subject of occasional discussion, and artisans and schoolboys have their views as to the permanence of organic forms. Moreover, the reception of this doctrine tends actually, though by no means necessarily, to be accompanied by certain beliefs with regard to quite distinct and very momentous subject-matter. So that the question of the "Genesis of Species" is not only one of great interest, but also of much importance.

But though the calm and thorough consideration of this matter is at the present moment exceedingly desirable, yet the actual importance of the question itself as to its consequences in the domain of theology has been strangely exaggerated by many, both of its opponents and supporters. This is especially the case with that form of the evolution theory which is associated with the name of Mr. Darwin; and yet neither the refutation nor the demonstration of that doctrine would be necessarily accompanied by the results which are hoped for by one party and dreaded by another.

The general theory of evolution has indeed for some time past steadily gained ground, and it may be safely predicted that the number of facts which can be brought forward in its support will, in a few years, be vastly augmented. But the prevalence of this theory need alarm no one, for it is, without any doubt, perfectly consistent with strictest and most orthodox Christian theology. Moreover, it is not altogether without obscurities, and cannot yet be considered as fully demonstrated.

The special Darwinian hypothesis, however, is beset with certain scientific difficulties, which must by no means be ignored, and some of which, I venture to think, are absolutely insuperable. What Darwinism or "Natural Selection" is, will [5]be shortly explained; but before doing so, I think it well to state the object of this book, and the view taken up and defended in it. It is its object to maintain the position that "Natural Selection" acts, and indeed must act, but that still, in order that we may be able to account for the production of known kinds of animals and plants, it requires to be supplemented by the action of some other natural law or laws as yet undiscovered.[1] Also, that the consequences which have been drawn from Evolution, whether exclusively Darwinian or not, to the prejudice of religion, by no means follow from it, and are in fact illegitimate.

The Darwinian theory of "Natural Selection" may be shortly stated thus:[2]—

Every kind of animal and plant tends to increase in numbers in a geometrical progression.

Every kind of animal and plant transmits a general likeness, with individual differences, to its offspring.

Every individual may present minute variations of any kind and in any direction.

Past time has been practically infinite.

Every individual has to endure a very severe struggle for existence, owing to the tendency to geometrical increase of all kinds of animals and plants, while the total animal and vegetable population (man and his agency excepted) remains almost stationary.

Thus, every variation of a kind tending to save the life of the individual possessing it, or to enable it more surely to propagate its kind, will in the long run be preserved, and will transmit its favourable peculiarity to some of its offspring, [6]which peculiarity will thus become intensified till it reaches the maximum degree of utility. On the other hand, individuals presenting unfavourable peculiarities will be ruthlessly destroyed. The action of this law of Natural Selection may thus be well represented by the convenient expression "survival of the fittest."[3]

Now this conception of Mr. Darwin's is perhaps the most interesting theory, in relation to natural science, which has been promulgated during the present century. Remarkable, indeed, is the way in which it groups together such a vast and varied series of biological[4] facts, and even paradoxes, which it appears more or less clearly to explain, as the following instances will show. By this theory of "Natural Selection," light is thrown on the more singular facts relating to the geographical distribution of animals and plants; for example, on the resemblance between the past and present inhabitants of different parts of the earth's surface. Thus in Australia remains have been found of creatures closely allied to kangaroos and other kinds of pouched beasts, which in the present day exist nowhere but in the Australian region. Similarly in South America, and nowhere else, are found sloths and armadillos, and in that same part of the world have been discovered bones of animals different indeed from existing sloths and armadillos, but yet much more nearly related to them than to any other kinds whatever. Such coincidences between the existing and antecedent geographical distribution of forms are numerous. Again, "Natural Selection" serves to explain the circumstance that often in adjacent islands we find animals closely resembling, and appearing to represent, each other; while if certain of these islands show signs (by depth of surrounding sea or what not) of more ancient separation, the [7]animals inhabiting them exhibit a corresponding divergence.[5] The explanation consists in representing the forms inhabiting the islands as being the modified descendants of a common stock, the modification being greatest where the separation has been the most prolonged.

"Rudimentary structures" also receive an explanation by means of this theory. These structures are parts which are apparently functionless and useless where they occur, but which represent similar parts of large size and functional importance in other animals. Examples of such "rudimentary structures" are the fœtal teeth of whales, and of the front part of the jaw of ruminating quadrupeds. These fœtal structures are minute in size, and never cut the gum, but are reabsorbed without ever coming into use, while no other teeth succeed them or represent them in the adult condition of those animals. The mammary glands of all male beasts constitute another example, as also does the wing of the apteryx—a New Zealand bird utterly incapable of flight, and with the wing in a quite rudimentary condition (whence the name of the animal). Yet this rudimentary wing contains bones which are miniature representatives of the ordinary wing-bones of birds of flight. Now, the presence of these useless bones and teeth is explained if they may be considered as actually being the inherited diminished representatives of parts of large size and functional importance in the remote ancestors of these various animals.

Again, the singular facts of "homology" are capable of a similar explanation. "Homology" is the name applied to the investigation of those profound resemblances which have so often been found to underlie superficial differences between animals of very different form and habit. Thus man, the horse, the whale, and the bat, all have the pectoral limb, whether it be the arm, or fore-leg, or paddle, or wing, formed on essentially the same type, though [8]the number and proportion of parts may more or less differ. Again, the butterfly and the shrimp, different as they are in appearance and mode of life, are yet constructed on the same common plan, of which they constitute diverging manifestations. No a priori reason is conceivable why such similarities should be necessary, but they are readily explicable on the assumption of a genetic relationship and affinity between the animals in question, assuming, that is, that they are the modified descendants of some ancient form—their common ancestor.

That remarkable series of changes which animals undergo before they attain their adult condition, which is called their process of development, and during which they more or less closely resemble other animals during the early stages of the same process, has also great light thrown on it from the same source. The question as to the singularly complex resemblances borne by every adult animal and plant to a certain number of other animals and plants—resemblances by means of which the adopted zoological and botanical systems of classification have been possible—finds its solution in a similar manner, classification becoming the expression of a genealogical relationship. Finally, by this theory—and as yet by this alone—can any explanation be given of that extraordinary phenomenon which is metaphorically termed mimicry. Mimicry is a close and striking, yet superficial resemblance borne by some animal or plant to some other, perhaps very different, animal or plant. The "walking leaf" (an insect belonging to the grasshopper and cricket order) is a well-known and conspicuous instance of the assumption by an animal of the appearance of a vegetable structure (see illustration on p. 35); and the bee, fly, and spider orchids are familiar examples of a converse resemblance. Birds, butterflies, reptiles, and even fish, seem to bear in certain instances a similarly striking resemblance to other birds, butterflies, reptiles, and fish, of altogether distinct kinds. The explanation of this matter which "Natural Selection" offers, as [9]to animals, is that certain varieties of one kind have found exemption from persecution in consequence of an accidental resemblance which such varieties have exhibited to animals of another kind, or to plants; and that they were thus preserved, and the degree of resemblance was continually augmented in their descendants. As to plants, the explanation offered by this theory might perhaps be that varieties of plants which presented a certain superficial resemblance in their flowers to insects, have thereby been helped to propagate their kind, the visit of certain insects being useful or indispensable to the fertilization of many flowers.

We have thus a whole series of important facts which "Natural Selection" helps us to understand and co-ordinate. And not only are all these diverse facts strung together, as it were, by the theory in question; not only does it explain the development of the complex instincts of the beaver, the cuckoo, the bee, and the ant, as also the dazzling brilliancy of the humming-bird, the glowing tail and neck of the peacock, and the melody of the nightingale; the perfume of the rose and the violet, the brilliancy of the tulip and the sweetness of the nectar of flowers; not only does it help us to understand all these, but serves as a basis of future research and of inference from the known to the unknown, and it guides the investigator to the discovery of new facts which, when ascertained, it seems also able to co-ordinate.[6] Nay, "Natural Selection" seems capable of application not only to the building up of the smallest and most insignificant organisms, but even of extension beyond the biological domain altogether, so as possibly to have relation to [10]the stable equilibrium of the solar system itself, and even of the whole sidereal universe. Thus, whether this theory be true or false, all lovers of natural science should acknowledge a deep debt of gratitude to Messrs. Darwin and Wallace, on account of its practical utility. But the utility of a theory by no means implies its truth. What do we not owe, for example, to the labours of the Alchemists? The emission theory of light, again, has been pregnant with valuable results, as still is the Atomic theory, and others which will readily suggest themselves.

With regard to Mr. Darwin (with whose name, on account of the noble self-abnegation of Mr. Wallace, the theory is in general exclusively associated), his friends may heartily congratulate him on the fact that he is one of the few exceptions to the rule respecting the non-appreciation of a prophet in his own country. It would be difficult to name another living labourer in the field of physical science who has excited an interest so widespread, and given rise to so much praise, gathering round him, as he has done, a chorus of more or less completely acquiescing disciples, themselves masters in science, and each the representative of a crowd of enthusiastic followers.

Such is the Darwinian theory of "Natural Selection," such are the more remarkable facts which it is potent to explain, and such is the reception it has met with in the world. A few words now as to the reasons for the very widespread interest it has awakened, and the keenness with which the theory has been both advocated and combated.

The important bearing it has on such an extensive range of scientific facts, its utility, and the vast knowledge and great ingenuity of its promulgator, are enough to account for the heartiness of its reception by those learned in natural history. But quite other causes have concurred to produce the general and higher degree of interest felt in the theory beside the readiness with which it harmonizes with biological facts. These latter could only be appreciated by physiologists, zoologists, and botanists; whereas [11]the Darwinian theory, so novel and so startling, has found a cloud of advocates and opponents beyond and outside the world of physical science.

In the first place, it was inevitable that a great crowd of half-educated men and shallow thinkers should accept with eagerness the theory of "Natural Selection," or rather what they think to be such (for few things are more remarkable than the way in which it has been misunderstood), on account of a certain characteristic it has in common with other theories; which should not be mentioned in the same breath with it, except, as now, with the accompaniment of protest and apology. We refer to its remarkable simplicity, and the ready way in which phenomena the most complex appear explicable by a cause for the comprehension of which laborious and persevering efforts are not required, but which may be represented by the simple phrase "survival of the fittest." With nothing more than this, can, on the Darwinian theory, all the most intricate facts of distribution and affinity, form, and colour, be accounted for; as well the most complex instincts and the most admirable adjustments, such as those of the human eye and ear. It is in great measure then, owing to this supposed simplicity, and to a belief in its being yet easier and more simple than it is, that Darwinism, however imperfectly understood, has become a subject for general conversation, and has been able thus widely to increase a certain knowledge of biological matters; and this excitation of interest in quarters where otherwise it would have been entirely wanting, is an additional motive for gratitude on the part of naturalists to the authors of the new theory. At the same time it must be admitted that a similar "simplicity"—the apparently easy explanation of complex phenomena—also constitutes the charm of such matters as hydropathy and phrenology, in the eyes of the unlearned or half-educated public. It is indeed the charm of all those seeming "short cuts" to knowledge, by which the labour of mastering scientific details is [12]spared to those who yet believe that without such labour they can attain all the most valuable results of scientific research. It is not, of course, for a moment meant to imply that its "simplicity" tells at all against "Natural Selection," but only that the actual or supposed possession of that quality is a strong reason for the wide and somewhat hasty acceptance of the theory, whether it be true or not.

In the second place, it was inevitable that a theory appearing to have very grave relations with questions of the last importance and interest to man, that is, with questions of religious belief, should call up an army of assailants and defenders. Nor have the supporters of the theory much reason, in many cases, to blame the more or less unskilful and hasty attacks of adversaries, seeing that those attacks have been in great part due to the unskilful and perverse advocacy of the cause on the part of some of its adherents. If the odium theologicum has inspired some of its opponents, it is undeniable that the odium antitheologicum has possessed not a few of its supporters. It is true (and in appreciating some of Mr. Darwin's expressions it should never be forgotten) that the theory has been both at its first promulgation and since vehemently attacked and denounced as unchristian, nay, as necessarily atheistic; but it is not less true that it has been made use of as a weapon of offence by irreligious writers, and has been again and again, especially in continental Europe, thrown, as it were, in the face of believers, with sneers and contumely. When we recollect the warmth with which what he thought was Darwinism was advocated by such a writer as Professor Vogt, one cause of his zeal was not far to seek—a zeal, by the way, certainly not "according to knowledge;" for few conceptions could have been more conflicting with true Darwinism than the theory he formerly maintained, but has since abandoned, viz. that the men of the Old World were descended from African and Asiatic apes, while, similarly, the American apes were the progenitors of the human beings of the New World. [13]The cause of this palpable error in a too eager disciple one might hope was not anxiety to snatch up all or any arms available against Christianity, were it not for the tone unhappily adopted by this author. But it is unfortunately quite impossible to mistake his meaning and intention, for he is a writer whose offensiveness is gross, while it is sometimes almost surpassed by an amazing shallowness. Of course, as might fully be expected, he adopts and reproduces the absurdly trivial objections to absolute morality drawn from differences in national customs.[7] And he seems to have as little conception of the distinction between "formally" moral actions and those which are only "materially" moral, as of that between the verbum mentale and the verbum oris. As an example of his onesidedness, it may be remarked that he compares the skulls of the American monkeys (Cebus apella and C. albifrons) with the intention of showing that man is of several distinct species, because skulls of different men are less alike than are those of these two monkeys; and he does this regardless of how the skulls of domestic animals (with which it is far more legitimate to compare races of men than with wild kinds), e.g. of different dogs or pigeons, tell precisely in the opposite direction. Regardless also of the fact that perhaps no genus of monkeys is in a more unsatisfactory state as to the determination of its different kinds than the genus chosen by him for illustration. This is so much the case that J. A. Wagner (in his supplement to Schreber's great work on Beasts) at first included all the kinds in a single species.

As to the strength of his prejudice and his regretable coarseness, one quotation will be enough to display both. Speaking of certain early Christian missionaries, he says,[8] "It is not so very improbable that the new religion, before which the flourishing Roman civilization relapsed into a state of barbarism, should have [14]been introduced by people in whose skulls the anatomist finds simious characters so well developed, and in which the phrenologist finds the organ of veneration so much enlarged. I shall, in the meanwhile, call these simious narrow skulls of Switzerland 'Apostle skulls,' as I imagine that in life they must have resembled the type of Peter, the Apostle, as represented in Byzantine-Nazarene art."

In face of such a spirit, can it be wondered at that disputants have grown warm? Moreover, in estimating the vehemence of the opposition which has been offered, it should be borne in mind that the views defended by religious writers are, or should be, all-important in their eyes. They could not be expected to view with equanimity the destruction in many minds of "theology, natural and revealed, psychology, and metaphysics;" nor to weigh with calm and frigid impartiality arguments which seemed to them to be fraught with results of the highest moment to mankind, and, therefore, imposing on their consciences strenuous opposition as a first duty. Cool judicial impartiality in them would have been a sign perhaps of intellectual gifts, but also of a more important deficiency of generous emotion.

It is easy to complain of the onesidedness of many of those who oppose Darwinism in the interest of orthodoxy; but not at all less patent is the intolerance and narrow-mindedness of some of those who advocate it, avowedly or covertly, in the interest of heterodoxy. This hastiness of rejection or acceptance, determined by ulterior consequences believed to attach to "Natural Selection," is unfortunately in part to be accounted for by some expressions and a certain tone to be found in Mr. Darwin's writings. That his expressions, however, are not always to be construed literally is manifest. His frequent use metaphorically of the expressions, "contrivance," for example, and "purpose," has elicited, from the Duke of Argyll and others, criticisms which fail to tell against their [15]opponent, because such expressions are, in Mr. Darwin's writings, merely figurative—metaphors, and nothing more.

It may be hoped, then, that a similar looseness of expression will account for passages of a directly opposite tendency to that of his theistic metaphors.

Moreover, it must not be forgotten that he frequently uses that absolutely theological term, "the Creator," and that he has retained in all the editions of his "Origin of Species" an expression which has been much criticised. He speaks "of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms, or into one."[9] This is merely mentioned in justice to Mr. Darwin, and by no means because it is a position which this book is intended to support. For, from Mr. Darwin's usual mode of speaking, it appears that by such divine action he means a supernatural intervention, whereas it is here contended that throughout the whole process of physical evolution—the first manifestation of life included—supernatural action is assuredly not to be looked for.

Again, in justice to Mr. Darwin, it may be observed that he is addressing the general public, and opposing the ordinary and common objections of popular religionists, who have inveighed against "Evolution" and "Natural Selection" as atheistic, impious, and directly conflicting with the dogma of creation.

Still, in so important a matter, it is to be regretted that he did not take the trouble to distinguish between such merely popular views and those which repose upon some more venerable authority. Mr. John Stuart Mill has replied to similar critics, and shown that the assertion that his philosophy is irreconcilable with theism is unfounded; and it would have been better if Mr. Darwin had dealt in the same manner with some of his assailants, and shown the futility of certain of their [16]objections when viewed from a more elevated religious standpoint. Instead of so doing, he seems to adopt the narrowest notions of his opponents, and, far from endeavouring to expand them, appears to wish to endorse them, and to lend to them the weight of his authority. It is thus that Mr. Darwin seems to admit and assume that the idea of "creation" necessitates a belief in an interference with, or dispensation of, natural laws, and that "creation" must be accompanied by arbitrary and unorderly phenomena. None but the crudest conceptions are placed by him to the credit of supporters of the dogma of creation, and it is constantly asserted that they, to be consistent, must offer "creative fiats" as explanations of physical phenomena, and be guilty of numerous other such absurdities. It is impossible, therefore, to acquit Mr. Darwin of at least a certain carelessness in this matter; and the result is, he has the appearance of opposing ideas which he gives no clear evidence of having ever fully appreciated. He is far from being alone in this, and perhaps merely takes up and reiterates, without much consideration, assertions previously assumed by others. Nothing could be further from Mr. Darwin's mind than any, however small, intentional misrepresentation; and it is therefore the more unfortunate that he should not have shown any appreciation of a position opposed to his own other than that gross and crude one which he combats so superfluously—that he should appear, even for a moment, to be one of those, of whom there are far too many, who first misrepresent their adversary's view, and then elaborately refute it; who, in fact, erect a doll utterly incapable of self-defence and then, with a flourish of trumpets and many vigorous strokes, overthrow the helpless dummy they had previously raised.

This is what many do who more or less distinctly oppose theism in the interests, as they believe, of physical science; and they often represent, amongst other things, a gross and narrow anthropomorphism as the necessary consequence of views [17]opposed to those which they themselves advocate. Mr. Darwin and others may perhaps be excused if they have not devoted much time to the study of Christian philosophy; but they have no right to assume or accept, without careful examination, as an unquestioned fact, that in that philosophy there is a necessary antagonism between the two ideas, "creation" and "evolution," as applied to organic forms.

It is notorious and patent to all who choose to seek, that many distinguished Christian thinkers have accepted and do accept both ideas, i.e. both "creation" and "evolution."

As much as ten years ago, an eminently Christian writer observed: "The creationist theory does not necessitate the perpetual search after manifestations of miraculous powers and perpetual 'catastrophes.' Creation is not a miraculous interference with the laws of nature, but the very institution of those laws. Law and regularity, not arbitrary intervention, was the patristic ideal of creation. With this notion, they admitted without difficulty the most surprising origin of living creatures, provided it took place by law. They held that when God said, 'Let the waters produce,' 'Let the earth produce,' He conferred forces on the elements of earth and water, which enabled them naturally to produce the various species of organic beings. This power, they thought, remains attached to the elements throughout all time."[10] The same writer quotes St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, to the effect that, "in the institution of nature we do not look for miracles, but for the laws of nature."[11] And, again, St. Basil,[12] speaks of the continued operation of natural laws in the production of all organisms. [18]

So much for writers of early and mediæval times. As to the present day, the Author can confidently affirm that there are many as well versed in theology as Mr. Darwin is in his own department of natural knowledge, who would not be disturbed by the thorough demonstration of his theory. Nay, they would not even be in the least painfully affected at witnessing the generation of animals of complex organization by the skilful artificial arrangement of natural forces, and the production, in the future, of a fish, by means analogous to those by which we now produce urea.

And this because they know that the possibility of such phenomena, though by no means actually foreseen, has yet been fully provided for in the old philosophy centuries before Darwin, or even before Bacon, and that their place in the system can be at once assigned them without even disturbing its order or marring its harmony.

Moreover, the old tradition in this respect has never been abandoned, however much it may have been ignored or neglected by some modern writers. In proof of this it may be observed that perhaps no post-mediæval theologian has a wider reception amongst Christians throughout the world than Suarez, who has a separate section[13] in opposition to those who maintain the distinct creation of the various kinds—or substantial forms—of organic life.

But the consideration of this matter must be deferred for the present, and the question of evolution, whether Darwinian or other, be first gone into. It is proposed, after that has been done, to return to this subject (here merely alluded to), and to consider at some length the bearing of "Evolution," whether Darwinian or non-Darwinian, upon "Creation and Theism."

Now we will revert simply to the consideration of the theory of "Natural Selection" itself.

Whatever may have hitherto been the amount of acceptance that this theory has met with, all, I think, anticipated that the appearance of Mr. Darwin's large and careful work on "Animals and Plants under Domestication" could but further increase that acceptance. It is, however, somewhat problematical how far such anticipations will be realized. The newer book seems to add after all but little in support of the theory, and to leave most, if not all, its difficulties exactly where they were. It is a question, also, whether the hypothesis of "Pangenesis"[14] may not be found rather to encumber than to support the theory it was intended to subserve. However, the work in question treats only of domestic animals, and probably the next instalment will address itself more vigorously and directly to the difficulties which seem to us yet to bar the way to a complete acceptance of the doctrine.

If the theory of Natural Selection can be shown to be quite insufficient to explain any considerable number of important phenomena connected with the origin of species, that theory, as the explanation, must be considered as provisionally discredited.

If other causes than Natural (including sexual) Selection can be proved to have acted—if variation can in any cases be proved to be subject to certain determinations in special directions by other means than Natural Selection, it then becomes probable a priori that it is so in others, and that Natural Selection [20]depends upon, and only supplements, such means, which conception is opposed to the pure Darwinian position.

Now it is certain, a priori, that variation is obedient to some law and therefore that "Natural Selection" itself must be capable of being subsumed into some higher law; and it is evident, I believe, a posteriori, that Natural Selection is, at the very least, aided and supplemented by some other agency.

Admitting, then, organic and other evolution, and that new forms of animals and plants (new species, genera, &c.) have from time to time been evolved from preceding animals and plants, it follows, if the views here advocated are true, that this evolution has not taken place by the action of "Natural Selection" alone, but through it (amongst other influences) aided by the concurrent action of some other natural law or laws, at present undiscovered; and probably that the genesis of species takes place partly, perhaps mainly, through laws which may be most conveniently spoken of as special powers and tendencies existing in each organism; and partly through influences exerted on each by surrounding conditions and agencies organic and inorganic, terrestrial and cosmical, among which the "survival of the fittest" plays a certain but subordinate part.

The theory of "Natural Selection" may (though it need not) be taken in such a way as to lead men to regard the present organic world as formed, so to speak, accidentally, beautiful and wonderful as is confessedly the hap-hazard result. The same may perhaps be said with regard to the system advocated by Mr. Herbert Spencer, who, however, also relegates "Natural Selection" to a subordinate rôle. The view here advocated, on the other hand, regards the whole organic world as arising and going forward in one harmonious development similar to that which displays itself in the growth and action of each separate individual organism. It also regards each such separate [21]organism as the expression of powers and tendencies not to be accounted for by "Natural Selection" alone, or even by that together with merely the direct influence of surrounding conditions.

The difficulties which appear to oppose themselves to the reception of "Natural Selection" or "the survival of the fittest," as the one explanation of the origin of species, have no doubt been already considered by Mr. Darwin. Nevertheless, it may be worth while to enumerate them, and to state the considerations which appear to give them weight; and there is no doubt but that a naturalist so candid and careful as the author of the theory in question, will feel obliged, rather than the reverse, by the suggestion of all the doubts and difficulties which can be brought against it.

What is to be brought forward may be summed up as follows:—

That "Natural Selection" is incompetent to account for the incipient stages of useful structures.

That it does not harmonize with the co-existence of closely similar structures of diverse origin.

That there are grounds for thinking that specific differences may be developed suddenly instead of gradually.

That the opinion that species have definite though very different limits to their variability is still tenable.

That certain fossil transitional forms are absent, which might have been expected to be present.

That some facts of geographical distribution supplement other difficulties.

That the objection drawn from the physiological difference between "species" and "races" still exists unrefuted.

That there are many remarkable phenomena in organic forms upon which "Natural Selection" throws no light whatever, but the explanations of which, if they could be attained, might throw light upon specific origination. [22]

Besides these objections to the sufficiency of "Natural Selection," others may be brought against the hypothesis of "Pangenesis," which, professing as it does to explain great difficulties, seems to do so by presenting others not less great—almost to be the explanation of obscurum per obscurius. [23]

THE INCOMPETENCY OF "NATURAL SELECTION" TO ACCOUNT FOR THE INCIPIENT STAGES OF USEFUL STRUCTURES.

Mr. Darwin supposes that natural selection acts by slight variations.—These must be useful at once.—Difficulties as to the giraffe; as to mimicry; as to the heads of flat-fishes; as to the origin and constancy of the vertebrate limbs; as to whalebone; as to the young kangaroo; as to sea-urchins; as to certain processes of metamorphosis; as to the mammary gland; as to certain ape characters; as to the rattlesnake and cobra; as to the process of formation of the eye and ear; as to the fully developed condition of the eye and ear; as to the voice; as to shell-fish; as to orchids; as to ants.—The necessity for the simultaneous modification of many individuals.—Summary and conclusion.

"Natural Selection," simply and by itself, is potent to explain the maintenance or the further extension and development of favourable variations, which are at once sufficiently considerable to be useful from the first to the individual possessing them. But Natural Selection utterly fails to account for the conservation and development of the minute and rudimentary beginnings, the slight and infinitesimal commencements of structures, however useful those structures may afterwards become.

Now, it is distinctly enunciated by Mr. Darwin, that the spontaneous variations upon which his theory depends are individually slight, minute, and insensible. He says,[15] "Slight [24]individual differences, however, suffice for the work, and are probably the sole differences which are effective in the production of new species." And again, after mentioning the frequent sudden appearances of domestic varieties, he speaks of "the false belief as to the similarity of natural species in this respect."[16] In his work on the "Origin of Species," he also observes, "Natural Selection acts only by the preservation and accumulation of small inherited modifications."[17] And "Natural Selection, if it be a true principle, will banish the belief ... of any great and sudden modification in their structure."[18] Finally, he adds, "If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down."[19]

Now the conservation of minute variations in many instances is, of course, plain and intelligible enough; such, e.g., as those which tend to promote the destructive faculties of beasts of prey on the one hand, or to facilitate the flight or concealment of the animals pursued on the other; provided always that these minute beginnings are of such a kind as really to have a certain efficiency, however small, in favour of the conservation of the individual possessing them; and also provided that no unfavourable peculiarity in any other direction accompanies and neutralizes, in the struggle for life, the minute favourable variation.

But some of the cases which have been brought forward, and which have met with very general acceptance, seem less satisfactory when carefully analysed than they at first appear to be. Amongst these we may mention "the neck of the giraffe."

At first sight it would seem as though a better example in support of "Natural Selection" could hardly have been chosen. [25]Let the fact of the occurrence of occasional, severe droughts in the country which that animal has inhabited be granted. In that case, when the ground vegetation has been consumed, and the trees alone remain, it is plain that at such times only those individuals (of what we assume to be the nascent giraffe species) which were able to reach high up would be preserved, and would become the parents of the following generation, some individuals of which would, of course, inherit that high-reaching power which alone preserved their parents. Only the high-reaching issue of these high-reaching individuals would again, cæteris paribus, be preserved at the next drought, and would again transmit to their offspring their still loftier stature; and so on, from period to period, through æons of time, all the individuals tending to revert to the ancient shorter type of body, being ruthlessly destroyed at the occurrence of each drought.

(1.) But against this it may be said, in the first place, that the argument proves too much; for, on this supposition, many species must have tended to undergo a similar modification, and we ought to have at least several forms, similar to the giraffe, developed from different Ungulata.[20] A careful observer of animal life, who has long resided in South Africa, explored the interior, and lived in the giraffe country, has assured the Author that the giraffe has powers of locomotion and endurance fully equal to those possessed by any of the other Ungulata of that continent. It would seem, therefore, that some of these other Ungulates ought to have developed in a similar manner as to the neck, under pain of being starved, when the long neck of the giraffe was in its incipient stage.

To this criticism it has been objected that different kinds of animals are preserved, in the struggle for life, in very different [26]ways, and even that "high reaching" may be attained in more modes than one—as, for example, by the trunk of the elephant. This is, indeed, true, but then none of the African Ungulata[21] have, nor do they appear ever to have had, any proboscis whatsoever; nor have they acquired such a development as to allow them to rise on their hind limbs and graze on trees in a kangaroo-attitude, nor a power of climbing, nor, as far as known, any other modification tending to compensate for the comparative shortness of the neck. Again, it may perhaps be said that leaf-eating forms are exceptional, and that therefore the struggle to attain high branches would not affect many Ungulates. But surely, when these severe droughts necessary for the theory occur, the ground vegetation is supposed to be exhausted; and, indeed, the giraffe is quite capable of feeding from off the ground. So that, in these cases, the other Ungulata must have taken to leaf eating or have starved, and thus must have had any accidental long-necked varieties favoured and preserved exactly as the long-necked varieties of the giraffe are supposed to have been favoured and preserved.

The argument as to the different modes of preservation has been very well put by Mr. Wallace,[22] in reply to the objection that "colour, being dangerous, should not exist in nature." This objection appears similar to mine; as I say that a giraffe neck, being needful, there should be many animals with it, while the objector noticed by Mr. Wallace says, "a dull colour being needful, all animals should be so coloured." And Mr. Wallace shows in reply how porcupines, tortoises and mussels, very hard-coated bombadier beetles, stinging insects and nauseous-tasted caterpillars, can afford to be brilliant by the various means of active defence or passive protection [27]they possess, other than obscure colouration. He says "the attitudes of some insects may also protect them, as the habit of turning up the tail by the harmless rove-beetles (Staphylinidæ) no doubt leads other animals, besides children, to the belief that they can sting. The curious attitude assumed by sphinx caterpillars is probably a safeguard, as well as the blood-red tentacles which can suddenly be thrown out from the neck by the caterpillars of all the true swallow-tailed butterflies."

But, because many different kinds of animals can elude the observation or defy the attack of enemies in a great variety of ways, it by no means follows that there are any similar number and variety of ways for attaining vegetable food in a country where all such food, other than the lofty branches of trees, has been for a time destroyed. In such a country we have a number of vegetable-feeding Ungulates, all of which present minute variations as to the length of the neck. If, as Mr. Darwin contends, the natural selection of these favourable variations has alone lengthened the neck of the giraffe by preserving it during droughts; similar variations, in similarly-feeding forms, at the same times, ought similarly to have been preserved and so lengthened the neck of some other Ungulates by similarly preserving them during the same droughts.

(2.) It may be also objected, that the power of reaching upwards, acquired by the lengthening of the neck and legs, must have necessitated a considerable increase in the entire size and mass of the body (larger bones requiring stronger and more voluminous muscles and tendons, and these again necessitating larger nerves, more capacious blood-vessels, &c.), and it is very problematical whether the disadvantages thence arising would not, in times of scarcity, more than counterbalance the advantages.

For a considerable increase in the supply of food would be requisite on account of this increase in size and mass, while at the same time there would be a certain decrease in strength; [28]for, as Mr. Herbert Spencer says,[23] "It is demonstrable that the excess of absorbed over expended nutriment must, other things equal, become less as the size of an animal becomes greater. In similarly-shaped bodies, the masses vary as the cubes of the dimensions; whereas the strengths vary as the squares of the dimensions.".... "Supposing a creature which a year ago was one foot high, has now become two feet high, while it is unchanged in proportions and structure—what are the necessary concomitant changes that have taken place in it? It is eight times as heavy; that is to say, it has to resist eight times the strain which gravitation puts on its structure; and in producing, as well as in arresting, every one of its movements, it has to overcome eight times the inertia. Meanwhile, the muscles and bones have severally increased their contractile and resisting powers, in proportion to the areas of their transverse sections; and hence are severally but four times as strong as they were. Thus, while the creature has doubled in height, and while its ability to overcome forces has quadrupled, the forces it has to overcome have grown eight times as great. Hence, to raise its body through a given space, its muscles have to be contracted with twice the intensity, at a double cost of matter expended." Again, as to the cost at which nutriment is distributed through the body, and effete matters removed from it, "Each increment of growth being added at the periphery of an organism, the force expended in the transfer of matter must increase in a rapid progression—a progression more rapid than that of the mass."

There is yet another point. Vast as may have been the time during which the process of evolution has continued, it is nevertheless not infinite. Yet, as every kind, on the Darwinian hypothesis, varies slightly but indefinitely in every organ and every part of every organ, how very generally must favourable [29]variations as to the length of the neck have been accompanied by some unfavourable variation in some other part, neutralizing the action of the favourable one, the latter, moreover, only taking effect during these periods of drought! How often must not individuals, favoured by a slightly increased length of neck, have failed to enjoy the elevated foliage which they had not strength or endurance to attain; while other individuals, exceptionally robust, could struggle on yet further till they arrived at vegetation within their reach.

However, allowing this example to pass, many other instances will be found to present great difficulties.

Let us take the cases of mimicry amongst lepidoptera and other insects. Of this subject Mr. Wallace has given a most interesting and complete account,[24] showing in how many and strange instances this superficial resemblance by one creature to some other quite distinct creature acts as a safeguard to the first. One or two instances must here suffice. In South America there is a family of butterflies, termed Heliconidæ, which are very conspicuously coloured and slow in flight, and yet the individuals abound in prodigious numbers, and take no precautions to conceal themselves, even when at rest, during the night. Mr. Bates (the author of the very interesting work "The Naturalist on the River Amazons," and the discoverer of "Mimicry") found that these conspicuous butterflies had a very strong and disagreeable odour; so much so that any one handling them and squeezing them, as a collector must do, has his fingers stained and so infected by the smell, as to require time and much trouble to remove it.

It is suggested that this unpleasant quality is the cause of the abundance of the Heliconidæ; Mr. Bates and other observers reporting that they have never seen them attacked by the birds, reptiles, or insects which prey upon other lepidoptera.

Now it is a curious fact that very different South American [30]butterflies put on, as it were, the exact dress of these offensive beauties and mimic them even in their mode of flight.

In explaining the mode of action of this protecting resemblance Mr. Wallace observes:[25] "Tropical insectivorous birds very frequently sit on dead branches of a lofty tree, or on those which overhang forest paths, gazing intently around, and darting off at intervals to seize an insect at a considerable distance, with which they generally return to their station to devour. If a bird began by capturing the slow-flying conspicuous Heliconidæ, and found them always so disagreeable that it could not eat them, it would after a very few trials leave off catching them at all; and their whole appearance, form, colouring, and mode of flight is so peculiar, that there can be little doubt birds would soon learn to distinguish them at a long distance, and never waste any time in pursuit of them. Under these circumstances, it is evident that any other butterfly of a group which birds were accustomed to devour, would be almost equally well protected by closely resembling a Heliconia externally, as if it acquired also the disagreeable odour; always supposing that there were only a few of them among a great number of Heliconias."

"The approach in colour and form to the Heliconidæ, however, would be at the first a positive, though perhaps a slight, advantage; for although at short distances this variety would be easily distinguished and devoured, yet at a longer distance it might be mistaken for one of the uneatable group, and so be passed by and gain another day's life, which might in many cases be sufficient for it to lay a quantity of eggs and leave a numerous progeny, many of which would inherit the peculiarity which had been the safeguard of their parent."

As a complete example of mimicry Mr. Wallace refers to a common Indian butterfly. He says:[26] "But the most wonderful and undoubted case of protective resemblance in a butterfly, [31]which I have ever seen, is that of the common Indian Kallima inachis, and its Malayan ally, Kallima paralekta. The upper surface of these is very striking and showy, as they are of a [32]large size, and are adorned with a broad band of rich orange on a deep bluish ground. The under side is very variable in colour, so that out of fifty specimens no two can be found exactly alike, but every one of them will be of some shade of ash, or brown, or ochre, such as are found among dead, dry, or decaying leaves. The apex of the upper wings is produced into an acute point, a very common form in the leaves of tropical shrubs and trees, and the lower wings are also produced into a short narrow tail. Between these two points runs a dark curved line exactly representing the midrib of a leaf, and from this radiate on each side a few oblique lines, which serve to indicate the lateral veins of a leaf. These marks are more clearly seen on the outer portion of the base of the wings, and on the inner side towards the middle and apex, and it is very curious to observe how the usual marginal and transverse striæ of the group are here modified and strengthened so as to become adapted for an imitation of the venation of a leaf." ... "But this resemblance, close as it is, would be of little use if the habits of the insect did not accord with it. If the butterfly sat upon leaves or upon flowers, or opened its wings so as to expose the upper surface, or exposed and moved its head and antennæ as many other butterflies do, its disguise would be of little avail. We might be sure, however, from the analogy of many other cases, that the habits of the insect are such as still further to aid its deceptive garb; but we are not obliged to make any such supposition, since I myself had the good fortune to observe scores of Kallima paralekta, in Sumatra, and to capture many of them, and can vouch for the accuracy of the following details. These butterflies frequent dry forests, and fly very swiftly. They were seen to settle on a flower or a green leaf, but were many times lost sight of in a bush or tree of dead leaves. On such occasions they were generally searched for in vain, for while gazing intently at the very spot where one had disappeared, it would often suddenly dart out, and again vanish twenty or fifty yards [33]further on. On one or two occasions the insect was detected reposing, and it could then be seen how completely it assimilates itself to the surrounding leaves. It sits on a nearly upright twig, the wings fitting closely back to back, concealing the antennæ and head, which are drawn up between their bases. The little tails of the hind wing touch the branch, and form a perfect stalk to the leaf, which is supported in its place by the claws of the middle pair of feet, which are slender and inconspicuous. The irregular outline of the wings gives exactly the perspective effect of a shrivelled leaf. We thus have size, colour, form, markings, and habits, all combining together to produce a disguise which may be said to be absolutely perfect; and the protection which it affords is sufficiently indicated by the abundance of the individuals that possess it."

Beetles also imitate bees and wasps, as do some Lepidoptera; and objects the most bizarre and unexpected are simulated, such as dung and drops of dew. Some insects, called bamboo and walking-stick insects, have a most remarkable resemblance to pieces of bamboo, to twigs and branches. Of these latter insects Mr. Wallace says:[27] "Some of these are a foot long and as thick as one's finger, and their whole colouring, form, rugosity, and the arrangement of the head, legs, and antennæ, are such as to render them absolutely identical in appearance with dry sticks. They hang loosely about shrubs in the forest, and have the extraordinary habit of stretching out their legs unsymmetrically, so as to render the deception more complete." Now let us suppose that the ancestors of these various animals were all destitute of the very special protections they at present possess, as on the Darwinian hypothesis we must do. Let it also be conceded that small deviations from the antecedent colouring or form would tend to make some of their ancestors escape destruction by causing them more or less frequently to [34]be passed over, or mistaken by their persecutors. Yet the deviation must, as the event has shown, in each case be in some definite direction, whether it be towards some other animal or plant, or towards some dead or inorganic matter. But as, according to Mr. Darwin's theory, there is a constant tendency to indefinite variation, and as the minute incipient variations will be in all directions, they must tend to neutralize each other, and at first to form such unstable modifications that it is difficult, if not impossible, to see how such indefinite oscillations of infinitesimal beginnings can ever build up a sufficiently appreciable resemblance to a leaf, bamboo, or other object, for "Natural Selection" to seize upon and perpetuate. This difficulty is augmented when we consider—a point to be dwelt upon hereafter—how necessary it is that many individuals should be similarly modified simultaneously. This has been insisted on in an able article in the North British Review for June 1867, p. 286, and the consideration of the article has occasioned Mr. Darwin to make an important modification in his views.[28]

In these cases of mimicry it seems difficult indeed to imagine a reason why variations tending in an infinitesimal degree in any special direction should be preserved. All variations would be preserved which tended to obscure the perception of an animal by its enemies, whatever direction those variations might take, and the common preservation of conflicting tendencies would greatly favour their mutual neutralization and obliteration if we may rely on the many cases recently brought forward by Mr. Darwin with regard to domestic animals.

Mr. Darwin explains the imitation of some species by others more or less nearly allied to it, by the common origin of both the mimic and the mimicked species, and the consequent possession by both (according to the theory of "Pangenesis") of gemmules tending to reproduce ancestral characters, which characters the [35]mimic must be assumed first to have lost and then to have recovered. Mr. Darwin says,[29] "Varieties of one species frequently mimic distinct species, a fact in perfect harmony with the foregoing cases, and explicable only on the theory of descent." But this at the best is but a partial and very incomplete explanation. It is one, moreover, which Mr. Wallace does not accept.[30] It is very incomplete, because it has no bearing on some of the most striking cases, and of course Mr. Darwin does not pretend that it has. We should have to go back far indeed to reach the common ancestor of the mimicking walking-leaf [36]insect and the real leaf it mimics, or the original progenitor of both the bamboo insect and the bamboo itself. As these last most remarkable cases have certainly nothing to do with heredity,[31] it is unwarrantable to make use of that explanation for other protective resemblances, seeing that its inapplicability, in certain instances, is so manifest.

Again, at the other end of the process it is as difficult to account for the last touches of perfection in the mimicry. Some insects which imitate leaves extend the imitation even to the very injuries on those leaves made by the attacks of insects or of fungi. Thus, speaking of one of the walking-stick insects, Mr. Wallace says:[32] "One of these creatures obtained by myself in Borneo (Ceroxylus laceratus) was covered over with foliaceous excrescences of a clear olive-green colour, so as exactly to resemble a stick grown over by a creeping moss or jungermannia. The Dyak who brought it me assured me it was grown over with moss although alive, and it was only after a most minute examination that I could convince myself it was not so." Again, as to the leaf butterfly, he says:[33] "We come to a still more extraordinary part of the imitation, for we find representations of leaves in every stage of decay, variously blotched, and mildewed, and pierced with holes, and in many cases irregularly covered with powdery black dots, gathered into patches and spots, so closely resembling the various kinds of minute fungi that grow on dead leaves, that it is impossible to avoid thinking at first sight that the butterflies themselves have been attacked by real fungi."

Here imitation has attained a development which seems utterly beyond the power of the mere "survival of the fittest" to produce. How this double mimicry can importantly aid in the struggle for life seems puzzling indeed, but much more so [37]how the first faint beginnings of the imitation of such injuries in the leaf can be developed in the animal into such a complete representation of them—a fortiori how simultaneous and similar first beginnings of imitations of such injuries could ever have been developed in several individuals, out of utterly indifferent and indeterminate infinitesimal variations in all conceivable directions.

PLEURONECTIDÆ, WITH THE PECULIARLY PLACED EYE IN DIFFERENT

POSITIONS.

PLEURONECTIDÆ, WITH THE PECULIARLY PLACED EYE IN DIFFERENT

POSITIONS.Another instance which may be cited is the asymmetrical condition of the heads of the flat-fishes (Pleuronectidæ), such as the sole, the flounder, the brill, the turbot, &c. In all these fishes the two eyes, which in the young are situated as usual one on each side, come to be placed, in the adult, both on the same side of the head. If this condition had appeared at once, if in the hypothetically fortunate common ancestor of these fishes an eye had suddenly become thus transferred, then the perpetuation of such a transformation by the action of "Natural Selection" is conceivable enough. Such sudden changes, however, are not those favoured by the Darwinian theory, and indeed the accidental occurrence of such a spontaneous transformation is hardly conceivable. But if this is not so, if the transit was [38]gradual, then how such transit of one eye a minute fraction of the journey towards the other side of the head could benefit the individual is indeed far from clear. It seems, even, that such an incipient transformation must rather have been injurious. Another point with regard to these flat-fishes is that they appear to be in all probability of recent origin—i.e. geologically speaking. There is, of course, no great stress to be laid on the mere absence of their remains from the secondary strata, nevertheless that absence is noteworthy, seeing that existing fish families, e.g. sharks (Squalidæ), have been found abundantly even down so far as the carboniferous rocks, and traces of them in the Upper Silurian.

Another difficulty seems to be the first formation of the limbs of the higher animals. The lowest Vertebrata[34] are perfectly limbless, and if, as most Darwinians would probably assume, the primeval vertebrate creature was also apodal, how are the preservation and development of the first rudiments of limbs to be accounted for—such rudiments being, on the hypothesis in question, infinitesimal and functionless?