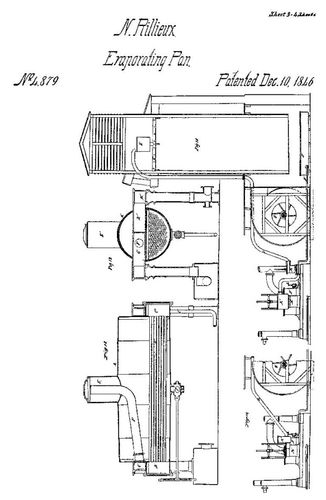

N. Rillieux Evaporating Pan. No. 4,879

N. Rillieux Evaporating Pan. No. 4,879Patented Dec. 10, 1846

Project Gutenberg's The Journal of Negro History, Volume 2, 1917, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Journal of Negro History, Volume 2, 1917 Author: Various Release Date: March 6, 2007 [EBook #20752] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NEGRO HISTORY *** Produced by Curtis Weyant, Richard J. Shiffer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible, including obsolete and variant spellings and other inconsistencies. Text that has been changed to correct an obvious error is noted at the end of this ebook. Also, the transcriber added the Table of Contents.

Vol II—January, 1917—No. 1

| Slavery and the Slave Trade in Africa | Jerome Dowd |

| The Negro in the Field of Invention | Henry E. Baker |

| Anthony Benezet | C. G. Woodson |

| People of Color in Louisiana - Part II | Alice Dunbar-Nelson |

| Notes on Connecticut as a Slave State | |

| Documents | |

| Letters of Anthony Benezet | |

| Reviews of Books | |

| Notes |

Vol II—April, 1917—No. 2

| Evolution of Slave Status in American Democracy - I | John M. Mecklin |

| John Woolman's Efforts in Behalf of Freedom | G. David Houston |

| The Tarik É Soudan | A. O. Stafford |

| From a Jamaica Portfolio | T. H. MacDermot |

| Notes on the Nomolis of Sherbroland | Walter L. Edwin |

| Documents | |

| Observations on the Negroes of Louisiana | |

| The Conditions against which Woolman and Anthony Benezet Inveighted | |

| Book Reviews | |

| Notes |

Vol II—July, 1917—No. 3

| Formation of American Colonization Society | Henry Noble Sherwood, Ph.D |

| Evolution of Slave Status in American Democracy - II | John M. Mecklin |

| History of High School for Negroes in Washington | Mary Church Terrell |

| The Danish West Indies | Leila Amos Pendleton |

| Documents | |

| Relating to the Danish West Indies | |

| Reviews of Books | |

| Notes | |

| African Origin of Grecian Civilization |

Vol II—October, 1917—No. 4

Slavery in Africa has existed from time immemorial, having arisen, not from any outside influence, but from the very nature of the local conditions. The three circumstances necessary to develop slavery are:

First, a country favored by the bounty of nature. Unless nature yields generously it is impossible for a subject class to produce surplus enough to maintain their masters. Where nature is niggardly, as in many hunting districts, the labor of all the population is required to meet the demands of subsistence.

Second, a country where the labor necessary to subsistence is, in some way, very disagreeable. In such cases every man and woman will seek to impose the task of production upon another. Among most primitive agricultural peoples, the labor necessary to maintenance is very monotonous and uninteresting, and no freeman will voluntarily perform it. On the contrary, among hunting and fishing peoples, the labor of maintenance is decidedly interesting. It partakes of the nature of sport.

Third, a country where there is an abundance of free land. In such a country it is impossible for one man to secure another to work for him except by coercion; for when[Pg 2] a man has a chance to use free land and its products he will work only for himself, and take all the product for himself rather than work for another and accept a bare subsistence for himself. On the contrary, where all the land is appropriated a man who does not own land has no chance to live except at the mercy of the landlord. He is obliged to offer himself as a wage-earner or a tenant. The landlord can obtain, therefore, all the help he may need without coercion. Free labor is then economically advantageous to both the landlord and the wage-earner, since the freedom of the latter inspires greatly increased production. From these facts and considerations, verified by history, it may be laid down as a sociological law that where land is monopolized slavery necessarily yields to a regime of freedom.[1]

In applying these principles to Africa it is necessary to take account of the natural division of the continent into distinct economic zones. Immediately under the equator is a wide area of heavy rainfall and dense forest. The rapidity and rankness of vegetable growth renders the region unsuited to agriculture. But the plentiful streams abound in fish and the forests in animals and fruits. The banana and plantain grow there in superabundance, and form the chief diet of the inhabitants. This may be called, for convenience, the banana zone. To the north and south of this zone are broad areas of less rainfall and forest, with a dry season suitable to agriculture. These may be called the agriculture zones. Still further to the north and south are areas of very slight rainfall and almost no forests, suitable for pasturage. Here cattle flourish in great numbers. These may be called the pastoral zones. These zones stretch horizontally across the continent except in case of the cattle zones, which, on account of the mountainous character of East Africa, include the plateau extending from Abyssinia to the Zambesi river. Each of these zones gives rise to different types of men, and different characteristics of economic organization, of family life, government, religion, and art.[Pg 3]

In the banana zone nature is extremely bountiful. The people subsist mostly upon the spontaneous products. A small expenditure of effort will support a vast population. Agriculture is very little practiced. Here the effort to live would seem to be easier and more agreeable than in any other part of the world, so that man would not be under pressure to enslave his kind. But alas, the work of gathering and transporting the fruits, of the preparation and cooking them, as well as the bringing home and cooking of the game, the building of houses, etc., is not altogether pleasant. It is uninteresting, and the heat and the humidity of the climate render it almost insupportable in certain seasons and hours of the day. The repugnance to labor of tropical people, whether natives or white immigrants, is proverbial. Every one in the banana zone, therefore, seeks to shift his burden upon another. As a first resort, he unloads it upon his wife, and she, finding it grievous, cries out, and he then relieves her by procuring additional wives. This kind of wife-slavery suffices for the support of the population in this zone, but in the case of families of rank, who have been accustomed to some degree of luxury, other helpers are needed, and these form a class of domestic slaves. Now, in this zone, the climatic conditions not only render labor disagreeable but tend to curb aspiration, so that people do not acquire a taste or demand for products which minister to the higher nature. Lassitude keeps the standard of living down to a low level. Hence, in this zone the labor of women suffices, for the most part, for the maintenance of the population. Since land is free and no one will voluntarily work for another, such additional workers as are needed must be obtained and bound to the master by coercion.

In this zone two very remarkable consequences follow from the fact that very few slaves are needed for workers. The first is the practice of cannibalism, once universal in this zone, and still in vogue throughout vast regions. The bountiful food supply attracts immigrants from all sides, and the result is a condition of chronic warfare. When one tribe defeats another the question arises, What is to be[Pg 4] done with the prisoners? As they cannot be profitably employed as industrial workers, they are used to supplement a too exclusive vegetable diet. Wars come to be waged expressly for the sake of obtaining human flesh for food. The Monbuttu eat a part of their captives fallen in battle, and butcher and carry home the rest for future consumption. They bring home prisoners not to reduce to slavery but as butcher-meat to garnish future festivals.

A second consequence of the limited demand for slaves is that war captives are sold to foreigners. Adjacent to the banana zone are zones of agriculture, where slaves are in great request, and, during the European connection with the slave trade, the normal demand for slaves in this zone was greatly heightened. Among the Niam Niam all prisoners belong to the monarch. He sells the women and keeps the children for slaves. Hence, the banana zone has been the great reservoir for supplying slaves to other parts of the world. Hundreds of thousands of slaves came from this zone to the West Indies, and to the slave states of North and South America. In Dahomey and Ashanti war captives used to be sold "en bloc" to white traders at so much per capita.

In the agricultural zones to the north and south nature is more niggardly, though she yields enough, when coaxed by the hoe, to permit of a large class of parasites. The labor of maintenance is more onerous than in the banana zone. While the heat and humidity are not so great the work is more grievous because of its greater quantity and monotony. The motive to shift the work is, therefore, very strong and the demand for slaves is very great. In fact, the ratio of slaves to freemen is about three or four to one. As land is free and the resources open, the only means of obtaining workers is by coercion. The supply of slaves is kept up by kidnapping, by warfare upon weak tribes, by the purchase of children from improvident parents, and by forfeiture of freedom through crime.

In the cattle zones farther to the north and south, nature is still less bountiful. The labor of maintenance requires[Pg 5] a combination of the pastoral art, agriculture and trade. A slave class could not maintain itself and at the same time support a large master class. The labor of a large proportion of the population is, in one way or another, necessary to existence. The nature of the work, so far as it is pastoral or trading, is not especially irksome, but rather fascinating. Tending cattle is full of excitement, and is a kind of substitute for hunting; while trading is an occupation which appeals with wonderful force to all the races of Africa. The impulse to shift labor in the cattle zones is, therefore, very slight, except in the case of a few populations subsisting largely upon agriculture. The ruling classes, therefore, instead of owning many personal slaves, make a practice of subjugating the agricultural groups in such a way as to constitute a kind of feudalism. As land is free the enslaved groups can be made to serve the free class only by coercion.

Similar conditions among the natural races all over the world give rise in the same way to the institution of slavery. Ellis thinks that slavery probably originated under the regime of exogamy where the sons born of captured women formed the slave class because they were considered inferior to the sons born of the women of the group.[2] But it is quite evident that slavery originated primarily from economic conditions. For further sociological explanations of slavery in the several zones the reader is referred to the author's first and second volumes on the Negro races.

The African slave trade goes back as far as our knowledge of the Negro race. The first Negroes of which we have any record were probably slaves brought in caravans to Egypt. They were in demand as slaves in all the oases of the deserts, and along the coasts of the Mediterranean. "Among the ruling nations on the north coast," says Heeren, "the Egyptians, Cyrenians and Carthaginians, slavery was[Pg 6] not only established but they imported whole armies of slaves, partly for home use, and partly, at least by the latter, to be shipped off to foreign markets. These wretched beings were chiefly drawn from the interior, where kidnapping was just as much carried on then as it is at present. Black male and female slaves were even an article of luxury, not only among the above mentioned nations, but even in Greece and Italy; and as the allurement to this traffic was on this account so great, the unfortunate Negro race had, even thus early, the wretched fate to be dragged into distant lands under the galling yoke of bondage."[3] Since the introduction of Mohammedanism, slaves have been carried eastward into all of the Moslem States as far as Asia Minor and Turkey, where they are still much valued as domestic servants or as eunuchs to guard the seraglios of Mohammedan princes. In the middle ages many African slaves were carried into Spain through the instrumentality of the Saracens, and from there the first slaves were imported into America. The supply of slaves for the Northern and Eastern States was obtained chiefly from the region of the Sudan. At an early period many caravan routes led northward from this region.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the slaves were obtained by a variety of methods, of which the most common was that of raiding the agricultural Nigritians who lived in towns and cities scattered and unorganized in the agricultural zone, and who were easy victims of the mounted bands of desert Berbers, Tuaregs and Arabs who descended into the region in quest of booty and captives. Robert Adams, an American sailor who was wrecked on the West Coast of Africa in 1810, said of the raiding parties sent out from Timbuktu, "These armed parties were all on foot except the officers. They were usually absent from one week to a month, and at times brought in considerable numbers," mostly from the Bambaras. "The slaves thus brought in were chiefly women and children, who, after[Pg 7] being detained a day or two at the king's house, were sent away to other parts for sale."[4]

The Fellatahs, who, since the beginning of the nineteenth century, have been the dominators of the Nigritians in West Africa, used to carry on a merciless campaign against their subjects, destroying their homes and fields, and seizing women and children by the thousands to barter away to the West, or to send across the desert. Describing the effects of a Fellatah raid, Barth says: "The whole village, which only a few moments before had been the abode of comfort and happiness, was destroyed by fire and made desolate. Slaughtered men, with their limbs severed from their bodies, were lying about in all directions and made passers-by shudder with horror."[5]

The slave traffic in the Sudan gave rise at a very early date to regular slave markets. The city of Jenné on the Niger was, in the middle ages, the greatest emporium in West Africa, far outshining Timbuktu. From the fifteenth century to the present time, the most celebrated slave markets have been Kuka, on Lake Chad, Timbuktu, capital of the Songhay empire, Kano, capital of the Haussa empire, and Katsena, capital of a district of the same name. Rohlfs found at the Kuka slave market, white haired old men and women, children suckling strange breasts, young girls and strong boys who had come from Bornu, Baghirmi, Haussa, Logun, Musgu, Waday and from lands still more distant.[6]

The slaves were carried across the desert by two kinds of caravans. First, those composed of nomad tribes, which migrated periodically from north to south. During the winter the tribes would pasture their camels along the edges of the desert, but in the spring they would visit the cities in the oases to gather up a supply of dates and other desert products to sell in the north. They would then in the same season proceed north to the cultivated regions of the Atlas mountains and arrive there in the midst of the harvest, exchanging their southern commodities for grain, raw-wool,[Pg 8] and a variety of European goods. At the end of the summer they would return to the south, arriving at the oases just as the dates were ripening. Here the grain, wool and other stuffs from the north would be exchanged for dates and manufactured articles of the desert. The same tribes which advanced from the oases of the desert to the north also descended towards the south, thus establishing intercourse between the Barbary States and Timbuktu. Many slaves picked up by these immigrating tribes were carried from one oasis to another until they were finally sold into the states bordering the Mediterranean.

The second kind of caravans were those conducted by merchants, traveling with hired camels, and making rapid and direct journeys across the desert to and from the chief slave markets. These caravans would come into the Sudan composed of men mounted upon camels, asses and mules, bringing salt, hides, cloth, and sundry articles from civilized North Africa, and return with slaves through Tibbu to Fezzan, and there fatten them for the Tripoli slave markets. Those that came to Timbuktu returned to any of the Barbary States, and there transferred their slaves to other traders who carried them as far as Turkey in Asia. Those that came to Kano usually passed out by way of Kuka or Katsena and proceeded thence by several routes to markets in North Africa.

The journey across the desert was exceedingly fatal to the blacks, since they were not accustomed to the northern climate. They suffered from hunger, thirst and cold, and a large per cent. of them perished along the way. Damberger, who traveled through the interior of Africa between 1781 and 1797, relates, as follows, his experience as a slave-captive in crossing the desert. Passing through the Sudan he fell in with some Moors, journeying to Tegorarin, where he was sold to a slave dealer, who resold him to a Mussulman en route to Mezzabath, a town on the river Oniwoh. Here again he was sold to a merchant who carried him to Marocco. He narrates that "On the 6th of September, my new master and I departed with the caravan. It consisted[Pg 9] of merchants from various nations, of persons of distinction, who had been performing a pilgrimage to Mecca, and of slaves. We proceeded slowly on our journey, as the roads were bad and our beasts were very heavily laden. Every day some of our company left the caravan, as we approached or passed the respective destinations. We traveled over mountains where the path was sometimes so narrow as only to permit the passage of one person at a time. We were constantly on the watch in these parts to prevent being surprised by the Arabs, as our caravan conveyed many valuable articles, which would have afforded rich plunder to those robbers. That which we apprehended actually happened on the seventh day after our departure, namely, on the 13th of Sept. A number of armed Arabs attacked us between the Cozul mountains and the river Tegtat; killed four of our slaves and three camels; and, though they lost several men in the attack, obstinately continued the combat. We defended ourselves to the utmost of our power, and at length had the good fortune to repel the whole troop. The victory, however, was not obtained till two of our merchants and five slaves were wounded, besides the four that were killed. We preserved all our property and the burthens of the slain camels were distributed among those that remained."[7]

An account of the caravan traffic from Timbuktu is given by Jackson, who says that Timbuktu "has from time immemorial carried on a very extensive and lucrative trade with the various maritime states of North Africa, viz., Marocco, Tunis, Algiers, Tripoli, Egypt, etc., by means of accumulated caravans, which cross the great desert of Sahara, generally between the months of September and April inclusive; these caravans consist of several hundred loaded camels, accompanied by the Arabs who let them to the merchants for the transportation of their merchandise to Fez, Marocco, etc., and at a very low rate. During their routes they were often exposed to the attacks of the roving Arabs of Sahara who generally commit their depredations as they[Pg 10] approach the confines of the desert."[8] The wind sometimes rolls up the sand like great billows of the ocean, and caravans are often buried under the pile, and then the wind, shifting, scatters in the air those newly constructed mounds, and forms, amidst the chaos, dreadful gulfs and yawning abysses: the traveler, continually deceived by the aspect of the place, can discover his situation only by the position of the stars.

When the caravans reach Akka, on the northern border of the desert, the camels and the guides are discharged, and others hired to proceed to Fez, Marocco, etc. The trip across the desert is made in about 130 days, including the necessary stops. Caravans go at the rate of three and one half miles an hour, and travel seven hours a day. The convoys of the caravan usually consist of two or more Arabs belonging to the tribe through whose territory the caravan passes. When the convoys reach the limit of their country, they transfer the caravan to other guides, and so on till the desert is crossed. The individuals who compose the caravans are accustomed to few comforts. "Their food, dress and accommodation are simple and natural: proscribed from the use of wine and intoxicating liquors by their religion, and exhorted by its principles to temperance, they were commonly satisfied with a few nourishing dates and a draft of water; and they will travel for weeks successively without any other food."[9]

The caravans from Timbuktu were wont to export to the Barbary States gold dust and gold rings, ivory, spices, and a great number of slaves. "A young girl of Haussa, of exquisite beauty," remarks Jackson, "was once sold at Marocco, whilst I was there, for four hundred ducats, whilst the average price of slaves is about one hundred."[10] As to the cost of transporting the slaves, Jackson states that "Ten dollars expended in rice in Wangara is sufficient for a year's consumption for one person; the wearing apparel[Pg 11] is alike economical; a pair of drawers, and sometimes a vest, forming all the clothing necessary in traversing the desert."[11]

Gen. Daumas describes a journey he made from Katsena in the Sudan across the desert about the middle of the nineteenth century. Arriving at Katsena, he says that his caravan was met by a great and mixed crowd of Negroes, who crowded around the camels, speaking in the most animated manner their unknown language. He and his companions were assigned to a special quarter of the city, and provided with lodgings. The camels were put in charge of some poor men of the caravan who led them away every day to the pasture, brought them back at four or five o'clock in the evening, and placed them in the enclosure in the city. The caravan leaders paid their respects to the chief of the city who bade them welcome and promised them protection. The business proceeded leisurely, as it was customary for the caravans to remain there two months.

The chief, not having a sufficient supply of slaves on hand to trade, caused his big drums to be beaten, and organized two bands of troops to execute a raid among the heathen tribes to the east and southwest. The raiding bands attacked only tribes with whom they were at war, or who refused to adopt the Mohammedan religion. While the troops were on the warpath, the caravan leaders visited the city slave market and made, from day to day, a few purchases. The price paid for an old Negro was 10,000 to 15,000 cowries, an adult Negro 30,000, a young Negro woman 50,000 to 60,000, a Negro boy or girl 35,000 to 45,000. The seller agreed to take back, within three days of the date of the purchase, any slaves that proved to have objectionable qualities, such as a disease, bad eyes or teeth, or a habit of snoring in sleep. As a rule slaves that come below Nupé were not salable for the reason that, being unaccustomed to eat salt, it was difficult for them to withstand the regime of the desert. Also, slaves from certain countries south of Kano were not salable because they were cannibals.[Pg 12] The slaves from this region were recognized by their teeth which were sharpened to a point, resembling those of a dog. Negroes from other tribes were not purchased because they were believed to have the power of causing a man to die of consumption by merely looking at him. The purchase of Fellatahs, or pregnant Negro women, or Jews was strictly forbidden by the Sultan. The Fellatahs were not bought because they boasted of being white people. The Negro women could not be bought because the child to be born would be the property of the Sultan if its mother were a heathen, and it would be free if the mother were a Mohammedan. The Jew Negroes could not be bought because they were jewelers, tailors, artisans and indispensable negotiators.

The raiding troops, after having been on the campaign for nearly a month, returned with 2,000 captives, who marched in front of the column, the men, women, old and young, almost all nude, or half clad in ragged blue cloth, and the children piled upon the camels. The women were groaning, and the children crying, while the men, though seemingly more resigned, bore bloody marks upon their backs made by the whips. The convoy was marched to the palace, where its arrival was announced to the Sultan by a band of musicians. The Sultan complimented the chief, examined the slaves and ordered them to the slave market; and the next morning the caravan leaders were invited to come and make their purchases.

After the slave-trading was over, it was necessary to purchase supplies of corn, millet, dried meat, butter and flour for three months, also to purchase camels and hide-tents. Daumas's caravan, which set out from Metlily with only 64 camels and sixteen men, had now increased to 400 slaves and nearly 600 camels.

A caravan from Tuat, which had joined that of Daumas, had augmented in the same proportions. It had bought 1,500 slaves and its camels had increased to 2,000. These two caravans waited two days to be joined by three others which had penetrated farther to the south. It was desirable[Pg 13] that all of the caravans recross the desert together in order better to resist attacks from the Tuaregs, Tibbus, and other highwaymen of that region.

The slaves had to be watched very closely, since believing that they were to be eaten by the white men, they were ready to take any chance of escaping. The women were tied in twos by the feet, and the men tied eight or ten together, each with his neck in an iron collar, to which was attached a short chain which held the hand of each slave at the height of his chest. At night Daumas fastened to his wrist the chains which bound all of his slaves together so that the least movement would wake him.

In a short time the three expected caravans arrived. One had originally come from Ghedames, one from Ghat and one from Fezzan. The first had gone as far as Nupé. It brought back 3,000 slaves and 3,500 camels. The second had gone to Kano and returned with 400 or 500 slaves and 700 or 800 camels. The third returned from Sokoto, and had about the same number of slaves and camels as the second.

After the proper ceremonies of farewell at the palace of the Sultan, the camels were loaded, and the children placed upon the baggage. The Negro men, chained together, were placed in the middle of each caravan, and the women were grouped eight or ten together, and guarded by a man with a whip. The signal was given, and the great combined caravans, consisting in all of about 6,000 slaves and 7,500 camels, started on their homeward march.

But suddenly there was a mighty noise of crying and groaning, of calling at each other and bidding farewell to friends. Some were so overcome at the fear of being eaten that they rolled upon the ground and absolutely refused to walk. Nothing could persuade them to get up until a guard came along with his great whip which brought blood at each lash. As the great army passed through the gate of the city, an officer of the Sultan examined every slave to be sure none was a Fellatah, Mohammedan, or Jew. The Ghat caravan happened to have among its slaves a[Pg 14] Fellatah, who was at once discovered and set free. At the first camp, says Daumas, "Each caravan established its bivouac separately, and as soon as the camels were crouched, and after having chained our Negro women by the feet and in groups of eight or ten, we forced our Negro men to aid us, with the left hand which we had left free, to unload our baggage, to arrange it in a circle and to stretch in the center the tents which we had brought from Katsena. Two or three of the oldest women that we had not put in chains, but who had always had their two feet fettered, were directed to prepare our supper. We ate in groups of four. This sad supper over, we placed the guards around our camp, and made the slave women and men sleep as before said."[12]

The next day the caravans were obliged to stop in consequence of a Negro woman who gave birth to a child. This stop, however, was not very lengthy. In a few hours she and her infant were placed upon a camel and the caravan went forward. When the camp was pitched for the next night, the leader, in making his rounds, ordered that the young Negro mother be left unshackled, and that she be given some meat for supper and allowed to sleep warmly upon a mat. But during the night, when everything was quiet, the mother put her infant in a basket filled with ostrich feathers, placed it upon her head, and made her escape.

Next morning, upon discovering her flight, several bands of men were sent out in different directions to find her. One of these, after a few hours of search, found her in a thicket nursing her child. She was led back to the camp, and two gun-shots recalled the other bands, and the caravans then resumed their march. The caravans stopped at Aghezeur to replenish their provisions and make repairs; and up to that time none of the people had died, and only one camel was lost.

After a month's traveling they reached "Ogla d'Assaoua," which was a rendezvous for all the marauding[Pg 15] bands that returned from the Sudan. It was particularly dangerous for the reason that it was the point at which groups of caravans divided and proceeded in different directions across the desert, and some of the independent caravans had to pass near the Tuareg nomads.

"None of our slaves," says Daumas, "I am sure, will ever forget this stop, for it was there that they were for the first time given their liberty after being in irons a month. The men and women danced all day after the fashion of their own country, until they fell prostrated with heat and fatigue. Even those whose legs and necks had been made sore from the chains took an active part in this fatiguing exercise, and all came to kiss our hands and to prostrate themselves at our feet and to sprinkle them with sand. We were careful not to interrupt this feast of good augury. It was the first proof to us that they had at last accepted their lot, and we had no longer to fear they would dream of escaping as they were so far from the Sudan and in the very middle of the desert.... From that day all were sincerely attached to us, and our joy was not less than theirs, for the continued watch which had been imposed upon us had been frightfully fatiguing. They helped us to load and unload our camels, to guide them en route, to stretch our tents, and to bring wood and water, labors which we alone had performed for a month. Finally we could lie down and sleep in peace."[13] At an early hour the next morning the tents were folded and the several caravans parted company. One went eastward through Ghat to Ghedames, accompanied as far as Ghat by another whose wares were sold in Fezzan and to other caravans coming from Murzuk. Another went eastward directly to Fezzan, where its merchandise was to be distributed to points in Tunis, Tripoli and Egypt. Daumas and his companion caravan of Tuat struck out to the northwest for the oasis of Tuat.

Two thirds of the camels bought by Daumas in the Sudan died before he reached "Isalab" (Ain Salah?), as they could not stand the hardship of the journey, especially the[Pg 16] chilly and damp nights of the desert. Arriving at Metlily the Arab merchants repaired to a mosque and thanked God for His protection.

In 1850 Barth estimated the number of slaves carried across the desert from Kuka at 5,000 per annum, and in 1865 Rohlfs estimated the number at 10,000. A British Blue Book of 1873 estimated that the Mohammedan States of North Africa absorbed annually one million slaves.

The mortality in crossing the desert was frightful. Denham saw near a well in the Tibbu country 100 skeletons of Negroes who had perished from hunger and thirst. In his travels he saw a skeleton every few miles, and for several days he passed from sixty to ninety skeletons per day. Sometimes a whole caravan perished, consisting of as many as 2,000 persons and 1,800 camels. The Negroes composing the caravans often had to walk and carry heavy loads. Rohlfs says that if one did not know the route of their pilgrimage he could find the way by the bones that lie to the right and left of the path. When he was passing through Murzuk in 1865, he gave medical aid to a slave dealer who was very ill, and, in compensation, received a boy about seven or eight years old. The boy had traveled four months across the desert from Lake Chad. He knew nothing of his home country, had even forgotten his mother tongue, and could jabber only some fragments of speech picked up from the other slaves of the caravan. As a result of the long journey he was emaciated to a skeleton and so enfeebled that he could scarcely stand up. He crawled on all fours and kissed the hand of his new master, and the first words he uttered were "I am hungry." The boy prospered and followed Rohlfs to Berlin. Thomson, in his travels, mentions having met a caravan of forty slave-girls crossing the Atlas Mountains on its way to Marocco. "A few were on camel-back, but most of them trudged on foot, their appearance[Pg 17] telling of the frightful hardships of the desert route. Hardly a rag covered their swarthy forms." Marocco used to be the destination of most of the slaves transported across the desert. About twenty-five years ago the center of the traffic in that state was Sidi Hamed ibu Musa, seven days journey south of Mogador where a great yearly festival was held. The slaves were forwarded thence in gangs to different towns, especially to Marocco City, and Mequinez. Writing in 1897, Vincent says the slave trade is as active as ever at Mequinez and Marocco City. The slaves were sold on Fridays in the public markets of the interior, but never publicly at any of the seaports, owing to the adverse European influence. There is a large traffic at Fez, but Marocco City is the great mart for them, where one may see frequently men, women and children sold at one time. Marakesh was once a chief market in Marocco. In 1892 a caravan from Timbuktu reached that city with no less than 4,000 slaves, chiefly boys and girls whose price ranged from ten to fourteen pounds per head. As many as 800 were sold there within ten days to buyers from Riff, Tafilett and other remote parts of the empire. A writer in the Anti-slavery Reporter, December, 1895, said: "Few people know the true state of affairs in Marocco; only those who live in daily touch with the common life of the people really get to understand the pernicious and soul-destroying system of human flesh-traffic as carried on in the public markets of the interior. Having resided and traveled extensively in Marocco for some seven years, I feel constrained to bear witness against the whole gang of Arab slave-raiders and buyers of poor little innocent boys and girls.

"When I first settled in Marocco I met those who denied the existence of slave-markets but since that time I have seen children, some of whom were of tender years, as well as very pretty young women, openly sold in the city of Marocco, and in the towns along the Atlantic seaboard. It is also of very frequent occurrence to see slaves sold in Fez, the capital of Northern Marocco.

"The first slave-girls that I actually saw being sold were[Pg 18] of various ages. They had just arrived from the Soudan, a distance by camel, perhaps, of forty days' journey. Two swarthy-looking men were in charge of them. The timid little creatures, mute as touching Arabic, for they had not yet learned to speak in that tongue, were pushed out by their captors from a horribly dark and noisome dungeon into which they had been thrust the night before. Then, separately, or two by two, they were paraded up and down before the public gaze, being stopped now and again by some of the spectators and examined exactly as a horse dealer would examine the points of a horse before buying the animal at any of the public horse-marts in England. The sight was sickening. Some of the girls were terrified, others were silent and sad. Every movement was watched by the captives, anxious to know their present fate. My own face blushed with anger as I stood helpless by and saw those sweet, dark-skinned, wooly-headed Soudanese sold into slavery.

"Our hearts have ached as we have heard from time to time from the lips of slaves of the indescribable horrors of the journeys across desert plains, cramped in pain, parched with thirst, and suffocated in panniers, their food a handful of maize. Again, we have sickened at the sight of murdered corpses, left by the wayside to the vulture and the burning rays of the African sun, and we have prayed, perhaps as never before, to the God of justice to stop these cruel practices."

Tunis and Algiers have also been great receptacles for the slaves of the Sudan. Describing the slave market at Tunis, Vincent says that it is a courtyard surrounded by arcades, the pillars of which are all of the old Roman fabrication. Around the court are little chambers or cells in which the slaves are kept, the men below, the women in the story above.

According to the statement of Barard, in 1906, Negro slavery is still prevalent throughout Marocco, and Negro women still populate the harems. "In the towns and plains, the present generations are pretty strongly colored by their[Pg 19] infusion of black blood. But the mountainous tribes who represent three fourths of a Maroccan population have kept themselves almost free from mixture; white or blond, they always resemble, by the color of their skin or texture of hair, the Europeans of Germany or France rather than the Mediterraneans of Spain and Italy." In Tunis the open sale of slaves is pretty well suppressed, but in a modified form the trade continues. Vivian says: "By resorting to fictitious marriages, and other subterfuges, the owner of a harem may procure as many slaves as he pleases, and, once he has got them into his house, no one can possibly interfere to release them. Slaves can, of course, escape and claim protection from the Consulates, but, as a matter of fact, they are generally quite contented with their position and know that such action would only involve them in ruin." In all of the Barbary States the slave trade is at the present time under prohibition, although it has not been effectively suppressed in any of them. According to a recent statement in the Anti-slavery Reporter, "a sale of slaves among which some white women and children were included, took place in a Fondak (an enclosure for accommodation of travelers and animals) in Tangier in April last (1906) and the sale was reported in a local newspaper, Al Moghreb Al Aksa." In July of the same year it was reported that a young black girl had been brought to the city and sold as a slave. The sultan had issued orders to the customs officers and at the various ports to prevent the transport of slaves by sea, and in event of any person discovered to be bringing slaves by sea, to punish him and free the slaves in his possession.

In July, 1906, the Anti-slavery Society of Italy published the particulars of a Turkish ship which left the port of Bengazi (Tripoli) for Constantinople with six slaves on board. Through the activity of the Society's agent the vessel was boarded and the slaves liberated.

Within the last decade the traffic in slaves across the desert has been limited to routes between the Niger and Marocco, and between Kuka and Tripoli. At the present[Pg 20] time there are probably no regular slave routes across the desert. Owing to the activity of European consuls in Northwest Africa caravans have a precarious existence and no safe markets.

"Only a few years ago," says the Anti-slavery Reporter, "Timbuctu, the famous trade metropolis of Central Africa, was also the most active center of the slave trade. French occupation (1894) has put an end to that traffic, and it is extending the pax Gallica throughout the vast and fertile territory of the Niger where formerly anarchy and brutality reigned."[14]

[1] Nieboer, "Slavery as an Industrial System," 257-348.

[2] "The Ewé Speaking Peoples," 222.

[3] "Historical Researches," 181.

[4] "Narrative of an American Sailor," 55.

[5] "Travels in North and Central Africa," II, 379.

[6] "Reise von Mittelmeer nach dem Tshad-See," I, 344.

[7] "Travels Through the Interior of Africa," 490.

[8] "An Account of the Empire of Morocco," 282.

[9] Ibid., 288.

[10] "Account of the Empire of Morocco," 292.

[11] Ibid., 295.

[12] "Le Grand Desert," 228.

[13] Ibid., 251.

[14] "Tunesia and the Modern Barbary Pirates," 65.

There is no branch of technical and scientific industry in our country that is at all comparable in scope and results with the business of perfecting inventions. These constitute the basis on which nearly all our great manufacturing enterprises are conducted, both as to the machinery employed and the articles produced. So vast is the field covered by inventors, and so industriously do they apply their talent to it that patents for new and useful inventions are now being granted them by our government at the rate of more than one hundred a day for every day that the office is open for business. And when one considers the enormous part played by American inventors in the economic, industrial and financial development of our country, it becomes a matter of importance to ascertain what share in this great work is done by the American Negro.

The average American seems not to know that the Negro has contributed very materially to this result. Not knowing it, he does not believe it, and not believing it he easily advances to the mental attitude of being ready to assert that the Negro has done absolutely nothing worth while in the field of invention. This conclusion necessarily grows out of the traditional attitude of the average American on the question of the capacity of the Negro for high scientific and technical achievement. This state of mind on the part of the general public is not perceptibly changed by the well-authenticated reports now and then of meritorious inventions in many lines of experiment made by Negroes in various parts of the country, notwithstanding the fact that these reports are frequently made through channels that would seem to leave nothing to doubt.

It has always been and presumably always will be difficult for truth to outrun a falsehood. One instance of the way in which such false and erroneous impressions of the[Pg 22] Negro's capacity and achievement gain currency and fix themselves in the public mind is shown sometimes in the campaign methods of some politicians. One of these, a Marylander, addressing a political gathering in his native State in behalf of his own candidacy for Congress, a few years ago declared that the Negro was not entitled to vote because he had never evinced sufficient capacity to justify such a privilege, and that not one of the race had ever yet reached the dignity of an inventor. It is not easy to understand how a gentleman of the requisite qualifications to represent an intelligent constituency acceptably in the Congress of the United States could so palpably pervert the truth in a matter on which he could so easily have rightly informed himself. At the time when this statement was made, 1903, in Talbot County, Maryland, there was on the shelves of the Library of Congress a book[15] containing a chapter on "The Negro as an Inventor," and citing several hundred patents granted by our government for inventions by Negroes. And still another instance is that of a leading newspaper of Richmond, which some time ago published the bold statement that of the many thousands of patents granted to the inventors in this country annually not a single patent had ever been granted to a colored man. These and similar general statements which make no mention of exceptions admit of but one interpretation. The wish may be father to the thought, but the truth is not father to their words.

In the cause of truth it is very gratifying to the writer to be able to show that notwithstanding the frequency and the persistency of these misrepresentations, the facts are gradually coming to the front to prove that the Negro not only now but in the remote past exhibited considerable of the inventive genius which has been so instrumental in the development of our country. In the ordinary course of investigation along this particular line the official records of the U. S. Patent Office must necessarily be referred to in[Pg 23] order to ascertain the number of patents granted either for a given class of inventors, or to a certain geographical group of citizens, as by State or nationality, or for a given period of time. But, voluminous as are these records, and various as are the items they cover, they make almost no disclosure of the fact that any of the multitude of patents that are granted daily are for inventions by Negroes. The solitary exception to this statement is the case of Henry Blair, of Maryland, to whom were granted two patents on corn harvesters, one in 1834, the other in 1836. In both cases he is designated in the official records as a "colored man." To the uninformed this very exception might appear conclusive, but it is not. It has long been the fixed policy of the Patent Office to make no distinction as to race in the records of patents granted to American citizens. All American inventors stand on a level before the Patent Office. It may perhaps be an open question whether, in the enforcement of such a policy, the advantages outweigh the disadvantages as it regards colored inventors.

In the period preceding the Civil War mechanical inventions of merit by colored persons were not numerous, so far as the investigation has shown, but this was also true of all classes of inventors of that time. With the great majority of slaves the question uppermost among them was how to effect their freedom, and those who were fortunately gifted with an active intelligence and some vision were, for the most part, using their mental faculties to devise some plan to interest others in their efforts for emancipation. This situation would obviously lend itself more readily to developing literary talent and oratorical ability than to producing machinists, engineers or inventors. Hence the preachers and teachers and orators of the colored race that here and there rose above the masses greatly outnumbered the inventors. But it should be remembered also in this connection that in the period just mentioned the mechanical industries of the South were carried on mostly by slaves, and that bits of history gathered here and there show that many of the simple mechanical contrivances of the day[Pg 24] were devised by the Negro in his effort to minimize the exactions of his daily toil. None of these inventions were patented by the United States as being the inventions of slaves; and it is quite conceivable that some inventions of value perfected by this class will be forever lost sight of through the attitude at that time of the Federal Government on that subject. In 1858 Jeremiah S. Black, Attorney-General of the United States, confirmed a decision of the Secretary of the Interior, on appeal from the Commissioner of Patents, refusing to grant a patent on an invention by a slave, either to the slave as the inventor, or to the master of the latter, on the ground that, not being a citizen, the slave could neither contract with the government nor assign his invention to his master.[16]

Another instance of this sort was an invention on the plantation owned by Jefferson Davis, of Mississippi, President of the late Confederate States. The Montgomerys, father and sons, were attached to this family, and some of them made mechanical appliances which were adopted for use on the estate. One of them in particular, Benjamin T. Montgomery, father of Isaiah T. Montgomery, founder of the prosperous Negro Colony of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, invented a boat propeller. It attracted the favorable attention of Jefferson Davis himself, who unsuccessfully tried to have it patented. The writer is informed by a recent letter from Isaiah T. Montgomery that it was Jefferson Davis's failure in this matter that led him to recommend to the Confederate Congress the law passed by that body favorable to the grant of patents for the inventions of slaves. The law was:

"And be it further enacted, that in case the original inventor or discoverer of the art, machine or improvement for which a patent is solicited is a slave, the master of such slave may take an oath that the said slave was the original; and on complying with the requisites of the law shall receive a patent for said discovery or invention, and have all the rights to which a patentee is entitled by law."[17]

The national ban on patents for the inventions of slaves did not, of course, attach itself to the inventions made by "free persons of color" residing in this country. So that when James Forten, of Philadelphia, who lived from 1766 to 1842, perfected a new device for handling sails, he had no difficulty in obtaining a patent for his invention, nor in deriving from it comfortable financial support for himself and family during the remainder of his life.

This was also true in the case of Norbert Rillieux, a colored Creole of Louisiana. In 1846 he invented and patented a vacuum pan which in its day revolutionized to a large extent the then known method of refining sugar. This invention with others which he also patented are known to have aided very materially in developing the sugar industry of Louisiana. Rillieux was a machinist and an engineer of fine reputation in his native State, and displayed remarkable talent for scientific work on a large scale. Among his other known achievements was the development of a practicable scheme for a system of sewerage for the city of New Orleans, but he here met his handicap of color through the refusal of the authorities to accord to him such an honor as would be evidenced by the acceptance and adoption of his plan.[18] Who knows but that the city of New Orleans might have been able to write a different chapter in the history of its health statistics on the Yellow Fever peril if its prejudices had not been allowed to dominate its prophecy?

Let us turn now to a consideration of those inventions made by colored inventors since the war period, and at a time when no obstacles stood in the way. With the broadening of their industrial opportunities, and the incentive of a freer market for the products of their talent, it was thought that the Negroes would correspondingly exhibit inventive genius, and the records abundantly prove this to have been true. But how have these records been made available? It has already been shown that no distinction as to race appears in the public records of the Patent Office,[Pg 27] and for this reason the Patent Office has been repeatedly importuned to set in motion some scheme of inquiry that would disclose, as far as is possible, how many patents have been granted by the government for the inventions of Negroes. This has been done by the Patent Office on two different occasions. The first official inquiry was made by the Office at the request of the United States Commission to the Paris Exposition of 1900, and the second at the request of the Pennsylvania Commission conducting the Emancipation Exposition at Philadelphia in 1913. In both instances the Patent Office sent out several thousand circular letters directed to prominent patent lawyers, large manufacturing firms, and to newspapers of wide circulation, asking them to inform the Commissioner of Patents of any authentic instances known by them to be such, in which the patents granted by the Office had been for inventions by Negroes.

The replies were numerous, interesting and informing. Every one of the several thousand that came to the Patent Office was turned over to the writer who, in his capacity as an employee of that department, very willingly assumed the additional task of assorting and recording them, verifying when possible the information presented, and extending the correspondence personally when this proved to be necessary either to trace a clew or clinch a fact. The information obtained in this way showed, first, that a very large number of colored inventors had consulted patent lawyers on the subject of getting patents on their inventions, but were obliged finally to abandon the project for lack of funds; secondly, that many colored inventors had actually obtained patents for meritorious inventions, but the attorneys were unable to give sufficient data to identify the cases specifically, inasmuch as they had kept no identifying record of the same; thirdly, that many patents had been taken out by the attorneys for colored clients who preferred not to have their racial identity disclosed because of the probably injurious effect this might have upon the commercial value of their patents; and lastly, that more than a thousand[Pg 28] authentic cases were fully identified by name of inventor, date and number of patent and title of invention, as being the patents granted for inventions of Negroes. These patents represent inventions in nearly every branch of the industrial arts—in domestic devices, in mechanical appliances, in electricity through all its wide range of uses, in engineering skill and in chemical compounds. The fact is made quite clear that the names obtained were necessarily only a fractional part of the number granted patents.

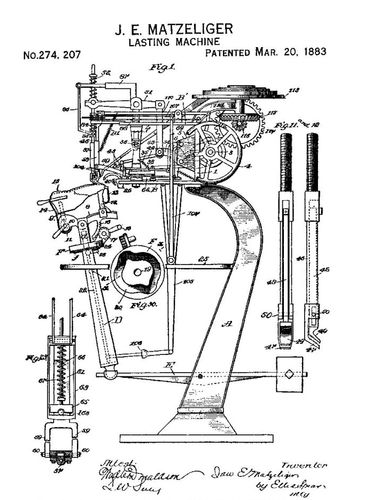

It developed through these inquiries that some very important industries now in operation on a large scale in our country are based on the inventions of Negroes. Foremost among these is the gigantic enterprise known as The United Shoe Machinery Company of Boston. In a biographical sketch of its president, Mr. Sidney W. Winslow, a multimillionaire,[19] it is related that he claims to have laid the foundation of his immense fortune in the purchase of a patent for an invention by a Dutch Guiana Negro named Jan E. Matzeliger. This inventor was born in Dutch Guiana, September, 1852. His parents were a native Negro woman and her husband, a Dutch engineer, who had been sent there from Holland to direct the government construction works at that place. As a very young man Matzeliger came to this country and served an apprenticeship as a cobbler, first in Philadelphia and later in Lynn, Massachusetts. The hardships which he suffered gradually undermined his health and before being able to realize the full value of his invention, he passed away in 1889 in the thirty-seventh year of his age.

He invented a machine for lasting shoes. This was the first appliance of its kind capable of performing all the steps required to hold a shoe on its last, grip and pull the leather down around the heel, guide and drive the nails into place and then discharge the completed shoe from the machine. This patent when bought by Mr. Winslow was made to form the nucleus of the great United Shoe Machinery Company, which now operates on a capital stock of[Pg 29] more than twenty million dollars, gives regular employment to over 5,000 operatives, occupies with its factories more than 20 acres of ground, and represents the consolidation of over 40 subsidiary companies. The establishment and maintenance of this gigantic business enterprise forms one of the biggest items in the history of our country's industrial development.

Within the first twenty years following the formation of The United Shoe Machinery Company, in 1890, the product of American shoe manufacturers increased from $220,000,000 to $442,631,000, and during the same period the export of American shoes increased from $1,000,000 to $11,000,000, the increase being traceable solely to the superiority of the shoes produced by the new American machines, founded on the Matzeliger type. The cost of shoes was reduced more than 50 per cent. by these machines and the quality improved correspondingly. The wages of workers greatly increased, the hours of labor diminished, and the factory conditions surrounding the laborers immensely improved. The improvement thus brought about in the quality and price of American shoes has made the Americans the best shod people in the world.[20]

That invention will serve as Matzeliger's towering monument far beyond our vision of years. Throughout all shoe-making districts of New England and elsewhere the Matzeliger type of machine is well known, and to this day it is frequently referred to in trade circles as the "Nigger machine," the relic, perhaps, of a possible contemptuous reference to his racial identity; and yet there were some newspaper accounts of his life in which it was denied that he had Negro blood in him. A certified copy of the death certificate of Matzeliger, which was furnished the writer by William J. Connery, Mayor of Lynn, on Oct. 23, 1912, states that Matzeliger was a mulatto.[Pg 30]

An illustration showing the models made by Matzeliger to illustrate

his inventions in shoe machines.

An illustration showing the models made by Matzeliger to illustrate

his inventions in shoe machines.Another prosperous business growing out of the inventions of a colored man is The Ripley Foundry and Machine Company, of Ripley, Ohio, established by John P. Parker. He obtained several patents on his inventions, one being a "screw for Tobacco Presses," patented in September, 1884, and another for a similar device patented in May, 1885. Mr. Parker set up a shop in Ripley for the manufacture of his presses, and the business proved successful from the first. The small shop grew into a large foundry where upwards of 25 men were constantly employed. It was owned and managed by Mr. Parker till his death. The factory is still being operated, and on the business lines originated by the founder, but the ownership has passed from the Parker family.

Another business, the development of which is due in large measure to the inventions of a colored man, Elijah McCoy, is that of making automatic lubricators for machinery. Mr. McCoy is regarded as a pioneer inventor in that line. He completed and patented his first lubricating cup in 1872. Since then he has patented both in this country and abroad nearly fifty different inventions relating principally to the art of automatic lubrication machinery, but including also a considerable variety of other devices. His lubricating cup was at one time in quite general use on the locomotives of the leading railways of the Northwest, on the steamers of the Great Lakes, and in up-to-date factories throughout the country. He is still living in Detroit, Michigan, and still adding new inventions to his already lengthy list.

In completing and patenting upwards of 50 different inventions Granville T. Woods, late of New York, appears to have surpassed every other colored inventor in the number and variety of his inventions. His inventive record began in 1884 in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he then resided, and continued without interruption for over a quarter of a century. He passed away January 30, 1910, in the city of New York, where he had carried on his business for several years immediately preceding. While his inventions relate principally to electricity, the list also includes such as a steam boiler furnace, the subject of his first patent, obtained in[Pg 32] June, 1884; an amusement apparatus, December, 1899; an incubator, August, 1900; and automatic airbrakes, in 1902, 1903, and 1905. His inventions in telegraphy include several patents for transmitting messages between moving trains, also a number of other transmitters. He patented fifteen inventions for electric railways, and as many more various devices for electrical control and distribution.

In the earlier stages of his career as a successful inventor he organized the Woods Electric Company, of Cincinnati, Ohio. This company took over by assignment many of his earlier patents; but as his reputation in the scientific world grew apace, and his inventions began to multiply in number and value, he seems to have found a ready market for them with some of the largest and most prosperous technical and scientific corporations in the United States. The official records of the United States Patent Office show that many of his patents were assigned to such companies as the General Electric Company, of New York, some to the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, of Pennsylvania, others to the American Bell Telephone Company, of Boston, and still others to the American Engineering Company, of New York. So far as the writer is aware there is no inventor of the colored race whose creative genius has covered quite so wide a field as that of Granville T. Woods, nor one whose achievements have attracted more universal attention and favorable comment from technical and scientific journals both in this country and abroad.

Granville Woods' brother, Lyates Woods, is credited with uniting with Granville in the joint invention of several machines. Most of these consisted of electrical apparatuses, but two of them seem to have been of sufficient importance to attract the attention of such corporations as the Westinghouse Electric Company, of Pennsylvania. Patents No. 775,825, of March 29, 1904, and No. 795,243, of July 18, 1905, both for railway brakes, were assigned by the Woods brothers to this company. The record shows that the American Bell Telephone Company purchased Woods' patent No. 315,386, granted April 7, 1885, for the latter's[Pg 33] invention of an apparatus for transmitting messages by electricity. The same inventor sold to the General Electric Company, of New York, his patent No. 667,110, of January 29, 1901, on his invention for electric railways.

We should mention here also two other inventors of importance in the line of appliances for musical instruments, Mr. J. H. Dickinson and his son S. L. Dickinson, both of New Jersey. They have been granted more than a dozen patents for their appliances, mostly in the line of devices connected with the player piano machinery. They are still engaged in the business of inventing, and both are holding responsible and lucrative positions with first-class music corporations.

The inventions of W. B. Purvis, of Philadelphia, in machinery for making paper bags are reported to be responsible for much of the great improvement made in that art; and his patents, more than a dozen in number on that subject alone, are said to have brought him good financial returns. Many of them are recorded as having been sold to the Union Paper Bag Company, of New York.

Another instance is that of an invention capable of playing an important part in the cotton raising industry. This was a cotton-picking machine covered by two patents granted to A. P. Albert, a native Louisiana Creole. Mr. Albert invented a second machine which is said to have the merit of perfect practicability, a feat not easy of accomplishment in that class of machinery. Special significance is attached to this case because of the inventor's experience in putting through his application for a patent. He was obliged to appeal from the adverse decision of the principal examiner to the Board of Examiners-In-Chief, a body of highly trained legal and technical experts appointed to pass upon the legal and mechanical merits of an invention turned down by the primary examiners. Albert appeared before this Board in his own defense with a brief prepared entirely by himself, and won his case through his thorough painstaking presentation of all the legal and technical points involved. Mr. Albert is a graduate of the Law Department of Howard University in Washington, and is connected with[Pg 34] the United States Civil Service as an examiner in the Pension Office.

Other colored men in the Departmental Civil Service at Washington have obtained patents for valuable inventions. W. A. Lavalette patented two printing presses, Shelby J. Davidson a mechanical tabulator and adding machine, Robert A. Pelham a pasting machine, Andrew F. Hilyer two hot air register attachments; and Andrew D. Washington a shoe horn. Nearly a dozen patents have been granted Benjamin F. Jackson, of Massachusetts, on his inventions. These consisted of a heating apparatus, a matrix drying apparatus, a gas burner, an electrotyper's furnace, a steam boiler, a trolley wheel controller, a tank signal, and a hydrocarbon burner system.

It is not generally known that Frederick J. Loudin, who brought fame and fortune to one of the leading Negro universities in the South by carrying the Fisk Jubilee Troupe of Singers on several successful concert tours around the world, is also entitled to a place on the list of Negro inventors. He obtained two patents for his inventions, one for a fastener for the meeting rails of sashes, December, 1893, and the other a key fastener in January, 1894. Several colored inventors have also applied their inventive skill to solving the problem of aerial navigation, with the result that some of them have been granted patents for their inventions in airships. Among these are J. F. Pickering, of Haiti, February 20, 1900; James Smith, California, October, 1912; W. G. Madison, Iowa, December, 1912; and J. E. Whooter, Missouri, 2 patents, October 30 and November 3, 1914. It has been reported that the invention in automatic car coupling covered by the patent to Andrew J. Beard, of Alabama, dated November 23, 1897, was sold by the patentee to a New York car company, for more than fifty thousand dollars. This same patentee has obtained patents on more than a half dozen other inventions, mostly in the same line.

Willie H. Johnson, of Texas, obtained several patents on his inventions, two of them being for an appliance for overcoming "dead center" in motion; one for a compound engine,[Pg 35] and another for a water boiler. Joseph Lee, a colored hotel keeper, of Boston, completed and patented three inventions in dough-kneading machines, and is reported as having succeeded in creating a considerable market for them in the bread-making industry in New England. Brinay Smartt, of Tennessee, made inventions in reversing valve gears, and received several patents on them in 1905, 1906, 1909, 1911 and 1913.

The path of the inventor is not always an easy one. The experiences of many of them often lie along paths that seem like the proverbial "way of the transgressor." This was fitly exemplified in the case of Henry A. Bowman, a colored inventor in Worcester, Massachusetts, who devised and patented a new method of making flags. After he had established a paying business on his invention, the information came to him that a New York rival was using the same invention and "cutting" his business. Bowman brought suit for infringement, but, as he informed the writer, the suit went against him on a legal technicality, and being unable to carry the case through the appellate tribunals, the destruction of his business followed.

One inventor, J. W. Benton, of Kentucky, completed an invention of a derrick for hoisting, and being without sufficient means to travel to Washington to look after the patent, he packed the model in a grip, and walked from Kentucky to Washington in order to save carfare. He obtained his patent, October 2, 1900.

One other instance in which the inventor regards his experience as one of special hardship is the case of E. A. Robinson of Chicago. He obtained several patents for his inventions, among which are an electric railway trolley, September 19, 1893; casting composite and other car wheels, November 23, 1897; a trolley wheel, March 22, 1898; a railway switch, September 17, 1907; and a rail, May 5, 1908. He regards the second patent as covering his most valuable invention. He says that this was infringed on by two large corporations, the American Car and Foundry Company, and the Chicago City Railway Company. He endeavored to stop[Pg 36] them by litigation, but the court proceedings in the case[21] appear to reveal some rather discouraging aspects of a fight waged between a powerless inventor on the one side and two powerful corporations on the other. So far as is known, the case is still pending.

These instances of hardships, however, in the lot of inventors are in no sense peculiar to colored inventors. They merely form a part of the hard struggle always present in our American life—the struggle for the mighty dollar; and in the field of invention as elsewhere the race is not always to the swift. A man may be the first to conceive a new idea, the first to translate that idea into tangible, practical form and reduce it to a patent, but often that "slip betwixt the cup and the lip" leaves him the last to get any reward for his inventive genius.

Because of the very many interesting instances at hand the temptation is very great to extend this enumeration beyond the intended limits of this article by specific references to the large number of colored men and women who in many lands and other days have given unmistakable evidence of really superior scientific and technical ability. But this temptation the writer must resist. Let it suffice to say that the citations already given show conclusively that the color of a man's skin has not yet entirely succeeded in barring his admission to the domain of science, nor in placing upon his brow the stamp of intellectual inferiority.

[15] "Twentieth Century Negro Literature," by W. W. Culp, page 399. Published by J. L. Nichols Co., Atlanta, Ga.

[16] Opinions of Attorney General of the U. S., Vol. 9, page 171.

[17] An act to establish a Patent Office, and to provide for granting patents for new and useful discoveries, inventions, improvements and designs. Statutes at large of the Confederate States of America, 1861-64, page 148.

[18] Desdunes, Nos Hommes et Notre Histoire, 101.

[19] Munsey's Magazine, August, 1912, p. 723.

[20] "Short History of American Shoemaking," by Frederick A. Gannon, Salem, Mass., 1912.

[21] A copy of this was shown the writer September, 1915.

During the eighteenth century the Quakers gradually changed from the introspective state of seeking their own welfare into the altruistic mood of helping those who shared with them the heritage of being despised and rejected of men. After securing toleration for their sect in the inhospitable New World they began to think seriously of others whose lot was unfortunate. The Negroes, therefore, could not escape their attention. Almost every Quaker center declared its attitude toward the bondmen, varying it according to time and place. From the first decade of the eighteenth century to the close of the American Revolution the Quakers passed through three stages in the development of their policy concerning the enslavement of the blacks. At first they directed their attention to preventing their own adherents from participating in it, then sought to abolish the slave trade and finally endeavored to improve the condition of all slaves as a preparation for emancipation.

Among those who largely determined the policy of the Quakers during that century were William Burling[22] of Long Island, Ralph Sandiford of Pennsylvania, Benjamin Lay of Abington, John Woolman of New Jersey and Anthony Benezet of Philadelphia. Early conceiving an abhorrence to slavery, Burling denounced it by writing anti-slavery tracts and portraying its unlawfulness at the yearly meetings of the Quakers. Ralph Sandiford followed the same[Pg 38] methods and in his "Mystery of Iniquity" published in 1729, forcefully exposed the iniquitous practice in a stirring appeal in behalf of the Africans.[23] Benjamin Lay, not contented with the mere writing of tracts, availed himself of the opportunity afforded by frequent contact with those in power to interview administrative officials of the slave colonies, undauntedly demanding that they bestir themselves to abolish the evil system.[24] Struck by the wickedness of the institution while traveling through the South prior to[Pg 39] the Revolution, John Woolman spent his remaining years as an itinerant preacher, urging the members of his society everywhere to eradicate the evil.[25] Anthony Benezet, going a step further, rendered greater service than any of these as an anti-slavery publicist and at the same time persistently toiled as a worker among the Negroes.

Benezet was born in St. Quentin in Picardy in France in 1713. He was a descendant of a family of Huguenots who after all but establishing their faith in France saw themselves denounced and persecuted as heretics and finally driven from the country by the edict of Nantes. One of the reformer's family, François Benezet, perished on the scaffold at Montpelier in 1755, fearlessly proclaiming to the multitude of spectators the doctrines for which he had been condemned to die.[26] Unwilling to withstand the imminent[Pg 40] persecution, however, John Stephen Benezet, Anthony's father, fled from France to Holland but after a brief stay in that country moved to London in 1715.

After being liberally educated by his father, Benezet served an apprenticeship in one of the leading establishments of London to prepare himself for a career in the commercial world. He had some difficulty, however, in coming to the conclusion that he would be very useful in this field. He, therefore, soon abandoned this idea and followed mechanical pursuits until he moved with his family to Philadelphia in 1731. There his brothers easily established themselves in a successful business and endeavored to induce Anthony to join them, but the youth was still of the impression that this was not his calling. His life's work was finally determined by his early connection with the Quakers, to the religious views and testimonies of whom he rigidly adhered. He continued his mechanical pursuit and later undertook manufacturing at Washington, Delaware, but feeling that neither of these satisfied his desire to be thoroughly useful he decided to return to Philadelphia to devote his life to religion and humanity.[27]

Benezet finally became a teacher. In this field he, for more than forty years, served in a disinterested and Christian spirit all who diligently sought enlightenment. He aimed to train up the youth in knowledge and virtue, manifesting in this position such "a rightness of conduct, such a courtesy of manners, such a purity of intention, and such a spirit of benevolence" that he attracted attention and ingratiated himself into the favor of all of those who knew him. He first served in this capacity in Germantown, working a part of his time as a proof reader. In 1742 he was chosen to fill a vacancy in the English department of the public school founded by charter from William Penn. After serving there satisfactorily twelve years he founded a female seminary of his own, instructing the daughters of the most aristocratic families of Philadelphia.[Pg 41][28]

Benezet was a really modern teacher, far in advance of his contemporaries. Much better educated than most teachers of his time, he could write his own textbooks. He had an affectionate and fatherly manner and always showed a conscientious interest in the welfare of his pupils. "He carefully studied their dispositions," says his biographer, "and sought to develop by gentle assiduity the peculiar talents of each individual pupil. With some persuasion was his only incitement, others he stimulated to a laudable emulation; and even with the most obdurate he seldom, if ever, appealed to any other corrective than that of the sense of shame and the fear of public disgrace." In his teaching, too, he endeavored to make "a worldly concern subservient to the noblest duties and the most intensive goodness."[29] In serious discussions like that of slavery he undertook to instill into the minds of his students firm convictions of the right, believing that in so doing he would greatly influence public sentiment when these properly directed youths should take their places in life.

This whole-souled energetic man, however, could not confine himself altogether to teaching. While following this profession he devoted so much of his time to philanthropic enterprises and reforms that he was mainly famous for his achievements in these fields. "He considered the whole world his country," says one, "and all mankind his brethren."[30] Benezet was for several reasons interested in the man far down. In the first place, being a Huguenot, he himself knew what it is to be persecuted. He was, moreover, during these years a faithful coworker of the Friends who were then fearlessly advocating the cause of the downtrodden. He deeply sympathized, therefore, with the Indians. His work, too, was not limited merely to that of relieving individual cases of suffering but comprised also the task of promoting the agitation for respecting the rights of that people. Unlike most Americans, he had faith in the Indians, believing that if treated justly they would give the[Pg 42] whites no cause to fear them. When in 1763 General Amherst was at New York preparing to attack the Indians, Benezet addressed him an earnest appeal in these words: "And further may I entreat the general, for our blessed Redeemer's sake, from the nobility and humanity of his heart, that he would condescend to use all moderate measures if possible to prevent that prodigious and cruel effusion of blood, that deep anxiety of distress, that must fill the breast of so many helpless people should an Indian war be once entered upon?"[31] Not long before his death Benezet expressed himself further on this wise in a work entitled "Some Observations on the Situation, Disposition, and Character of the Indian Natives of the Continent."