This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Wonder Island Boys: Exploring the Island

Author: Roger Thompson Finlay

Release Date: February 16, 2007 [eBook #20588]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WONDER ISLAND BOYS: EXPLORING THE ISLAND***

CHAPTER I. The Fourth Voyage of Discovery

The journey into the forest. Restlessness of the yaks. The alarm. Wild animals. George Mayfield and Harry Crandall. Their companion, an aged Professor. Their history. How they were shipwrecked. Thrown on an island without weapons, tools, food, or any of the requirements of life. What they had accomplished previous to the opening of this chapter. Making tools. Capturing yaks and training them. The three previous expeditions, and what they discovered. The mysterious occurrences. The fourth voyage of discovery. Losing sight of the strange animals. The forest. Discovering orang-outans. Capturing a young orang. Christening the "Baby." Its strange and restless actions. A shot. A wild animal. The wildcat. Enemy of the orang-outan. Distances deceptive, and why. Peculiar sensations at altitudes. Tableland. The fifth day. Discovery of a broad river. Progress barred.

CHAPTER II. The Mysterious Lights

A mountain chain beyond the river. Adventures along the river. Decide to follow the river to the north. Camping at the shore of a small stream. Prospecting tour on the stream. The flint arrow. The arrow in the skull of an animal. Different kinds of arrows. Home-sick. The light across the river. The test of firing a gun. Disappearance of the light. Seeking explanation. The night watch. The early breakfast and start. Scouting in advance. Qualifications in scouting.

A coast line of steep hills. Shooting an animal. The answering shot. The wonderful echo. Calculating distance of the bluff by the sound. The bear. The attack of the bear. The Professor's shot. The frightened yaks. Recovery of the wagon. Death of the bear. Rugged traveling. Changing their course. Deciding to return to their home. Stormy weather. The traveling chart. Methods used to determine course in traveling. An adjustable square. Obtaining angles from the shadows.

CHAPTER IV. The Disappearance of the Yaks

Breezes from the north. Indications of proximity of the sea. Warm winds. What wind temperatures tell. The missing yak herd. Mystery of the turning water wheel. The mill and workshop. Their home. "Baby" learning civilized ways. The noise in the night. The return of the yaks. The need for keeping correct time. Shoe leather necessary. Threshing out barley. The flail. The grindstone. Making flour. Baking bread. How the bread was raised. What yeast does in bread. Temperature required. The "Baby" and the honey pot. The bread with large holes in it. George's trip to the cliffs. A peculiar sounding noise and spray from the cliffs. An air pocket. Compressed air. Non-compressible water.

Earthquake indications. The seismograph. The theory about the interior of the earth. How geologists know the composition of the interior of the earth for miles down. The earth's "crust." The weekly hunting trip. Determine to cross South River and explore. The lost hatchet found. Making a raft to cross the river. Going into the interior. The sound of moving animals. Caution in approaching. Discovering the beast. Two shots. The disappearing animal. Indications that the animal was hit. Trail lost. Returning to the river. The animal again sighted. Firing at the animal. The shots take effect. The animal too heavy to carry. Return to the Cataract home. Finding the camphor tree. Its wonders as a medicine. Calisaya. Algoraba, a species of bean, or locust. Sarsaparilla. The trip to South River with the team. Finding the shot animal. The ocelot. Two bullet holes instead of one. The animal not at the place where it was shot the night before. Mystery explained by the finding of second animal which they had shot. Skinning the animals.

CHAPTER VI. Hunting Vegetables and Plants

The accomplishments of George and Harry. Theory and practice. Fermentation. How heat develops germs. Bacteria. Harmless germs. Tribes of germs. Septic system of sewage. The war between germs. Setting germs to work. Indications from the vegetable world as to the climate. Prospecting in the hills. Tanning leather. Bark, and what it does in tanning. Different materials used. The gall nut and how it is formed. Different kinds of leaves. The edges of leaves. The most important part of every vegetation. Trip to the cliffs. Hunting for the air pocket. Discovery of a cave. Exploring the cave. The water in the cave. Indication of marine animal in the water. Return to the mouth of the cave. Discovering the air pocket. The peculiar light in the cave. Calcium coating.

CHAPTER VII. Investigating the Prospector's Hole

Speculation as to the animal in the cave. Determined to explore the mystery of the "hole" in the hill. Trip to the hills. Difficulty in finding the "hole." Accidental discovery of a rock. The "hole" found. Indication that it was made by man. Why plants flourish around holes and stones. Moisture and heat. Object of cultivating plants. Lead and silver ore. Zinc. Working with their ore furnace. Putting metals to work. Labor-saving tools, what they are and what they do. Roasting ore. Melting roasted ore in crucible. Recovering zinc. Light from zinc and copper. Harry bitten by a "cat." The zibet.

Different fruit, flowers and vegetables. The thistle. Its nutritious qualities. Why animals can eat it. The sorrel and the shamrock. Significance of the latter. Vanilla. Smell is vibration. Harmony and discord in odors. What essences are composed of. Preserving seeds for planting. Food elements in vegetables. Surprising increase in their herd of yaks. Investigation. The wild bull. Apollo, the bull of their herd. His absence. The wild bull charging George. Stampede of the herd. George carried with them. Appearance of Apollo. Engaging in combat. Apollo the stronger. Reappearance of George. Return of the cows. Apollo the victor. Finding a brand mark on the wild bull. Inventory of their stock. Work in tanning vats. The flash of Harry's gun in the distance. Explanation of the difference in time between the flash and report. "Sound" or "noise." Vibrations. Light. The locomotive whistle explained.

CHAPTER IX. Exciting Experiences with the Boats

Health on the island. Illness of Harry. Fever. Determining temperature. Making a thermometer. Substitutes for glass and mercury. How Fahrenheit scale is determined. Centigrade scale. Testing the thermometer. Determining fever. Danger point. Why a coiled pipe tries to straighten out under pressure. Medicine for fever. Rains and rising Cataract River. Decision to explore sea coast to the east. Yoking up the yaks. Gathering samples of plants and flowers. The beach. Following the shore line. Discovering the boat which had disappeared from the Falls in South River. Surprising find of strange oars and unfamiliar rope in the boat. Harry and George decide to sail the boat around the cliff point to the Cataract River. The Professor takes the team home. Sighting an object on the cliffs. Going ashore at the foot of the cliffs for an examination. Ascending the cliffs. Discovering the wrecked remains of their life-boat. Consternation when their boat is washed away from the shore. Getting the wreck of the life-boat down to the water. The watching and waiting Professor. The boys launch the life-boat and float to the mainland. Meeting the Professor. Explanations.

CHAPTER X. The Birthday Party and the Surprise

Theory that their island is near some other inhabited island. The mysterious occurrences of the fire in the forest; the lights across the river. The disappearance of their boat. The removal of the flagpole and flag; the arrows; the hole in the hillside; the finding of the boat with unfamiliar oars and rope on it. Conclude to make another boat. Unsanitary arrangement of their kitchen. Purifying means employed. Different purifying agents. Primary electric battery. The cell; how made. The electrodes. Clay. The positive and the negative elements. How connected up. The battery. Making wire. How electricity flows. Rate of flow. Volts and amperes. Pressure and quantity. Drawing out the wire. Tools for drawing the wire. Friction. Molecules and atoms. Accomplishments of "Baby." Climbing trees and finding nuts. George as cook. Making puddings. "Baby's" aid. Finding eggs of prairie chicken. Planning a surprise for the Professor. The birthday party. George's cakes to celebrate the event. Harry's gong. The missing cakes. "Baby" the thief. The feast. Why laughter is infectious. Odors. Beautiful perfumes wafted to long distances. Bad odors destroyed. Why. Oxygen as a purifying agent.

CHAPTER XI. The Gruesome Skeleton

The Cataract water. Common oak chips as purifiers. Tannic acid. Bitter almonds. Universal purification of water. The Bible method. Albumen impurities in water. Electric battery. The electrode. How the cells were made. Object of plurality of cells. Volts, amperes and watts, and their definitions. A new boat determined on. Determining size of the boat. Recovering their life-boat. Visit to Observation Hill. Hunting for the lost flagpole and flag. Wreckage of a ship's boat discovered. The Professor sent for. Ascertain it is not part of their wrecked boat. Gathering up portions of the boat. Amazing discovery of skull and skeleton. Methods of determining age. Condition of the skull and teeth. Carrying the remains to the Cataract. The funeral. The seven ages in the growth of man. Sadness. The skeleton at the feast. Why is death necessary. One of the many reasons.

CHAPTER XII. The Distant Ship and Its Disappearance

The endive. Chicory. The principle in the plant. The root. Curious manner of preparing it. A surprise for Harry. Making clay crocks. How to glaze or vitrify them. The use of salt in the process. A potter's wheel. Uses of the wheel. Its antiquity. Inspecting the electric battery. How it is connected up. Peculiarities in designating parts of the battery. Making the first spark. Necessary requirements for making a lighting plant. The arc light. What arc is and means. The incandescent light. Why the filament in bulb does not readily burn out. Oxygen as a supporter of combustion. Carbon, how made. Essential of the invention of the arc light. Determine again to explore cave. The lamps, spears and other equipment. Exciting discovery of a sail. Signaling the ship. The ship disappears. Discouragement. Determine to make a large flag and erect a new flagpole. Visiting the cave. Exploring it. Mounting one of the lamps on ledge for safety. Water not found where it was on previous visit. Discovery of a large domed chamber. Bringing forward the light on the ledge. Entering the chamber. Disappearance of the light from the ledge. The outlet of the chamber. Searching for the lost light. Determine to chart the cave. Steps taken. Surveying methods. Substitutes for paper and pencil. Soot. The base, the angle, and the projecting lines. How the side walls were charted.

CHAPTER XIII. The Exciting Hunt in the Forest

An eventful day. Accounting for the disappearance of the water in the cave. The animal in the cave. Subterranean connection with the sea. Starting to make the large flag. Regulation flag determined on. The stripes and their colors, and how arranged. Their significance. The blue field and how studded. Its proportional size. How the yellow ramie cloth was made white. The bleaching process. Chloride of lime. The red color. The madder plant. Its powerful dyeing qualities. Coffee. The surprise party for Harry. Chicory leaves as a salad. Exhilarative substances and beverages. The cocoa leaf. Betel-nut. Pepper plants. Thorn apples. The ledum and hop. Narcotic fungus. "Baby's" experiment with the red dye test sample. Test samples in dyeing. Color-metric tests in analyzing chemicals. Reagents. The meaning and their use. Bitter-sweet. Blue dye. Copper and lime as coloring substance. The completed flag. A hunting trip for the pole. Making a trailer. A pole fifty feet long determined on. Tethering the yaks at the river. Searching for pole. The shell-bark hickory. The giant ant-killer. His peculiarities. Weight of hickory. Weight of the pole. Problem to convey it to the river. Determine to get the yaks. Swimming them across the river. The Professor absent on their return. Searching for the Professor. A shot heard. Going in the direction of the shot. Another shot from vicinity of the team. Returning in the direction of last shot. Find the Professor with team on way to river. How they made a circle without knowing it. A lesson in judgment.

CHAPTER XIV. The Raising of the Flag, and Angel's Part In It

Absence of Red Angel. The search. Sorrow at his flight. The morning breakfast. Reappearance of Red Angel with nuts. The honey pot and Red Angel. The voluntary exchange of nut for honey. How the orang reasoned. Preparation for pole-raising day. The capstans. The ropes and forked poles. The Angel invited to attend. How the pole was raised. Preparation to hoist the flag. The interference of Red Angel. How he mounted the pole. How honey was no temptation. George's discovery that Angel had eaten all the honey. The ceremony of raising the flag. Trying to sing the Star-Spangled Banner. The failure. Taking possession of the island in the name of the United States. Significance of the act of taking possession. Heraldry and the bending of the flag on the halliards. The banner and flag in ancient times. Leaving the flag at half-mast. The banner in the Bible. The necessity for making glass. Its early origin. The crystal of the ancients. What it is made of. The blowing process. An acid and an alkali. Sand as an acid. Lime, soda, and potash as alkalis. The result when united. Transparent and translucent. Opaqueness. Making sheet glass. Why the eye cannot see through rough glass. How sheets are prevented from being cracked.

CHAPTER XV. Mysterious Happenings on the Island

Heating the crucibles for fusing glass. Eliminating impurities. Result of too much alkali. A test sample of glass. Speculation as to the inhabitants of the island. Their knowledge of the presence of savages. Mysterious occurrences while on the island. Determining to make further explorations for their own safety. The guns they had made. The hesitation about the trip inland. The hope for another ship. Discussing the probability of meeting the savages. Questions to be decided in building their boat. Possibilities of an island near them. Reasons for that view. A year from the time they sailed from New York. The spring. Planting a garden. Preparing the ground. The buckwheat. Propagation. Wild oats. How cultivated. Budding, grafting and inarching. Seedless fruit. Conclude to utilize the wrecked part of the life-boat as part of the new boat. Size of the new vessel. Its size and weight What is a ship. A brig, a sloop. Single masters. The sails. Different parts of the masts. The bowsprit and boom. The triangular sail.

CHAPTER XVI. Discovery of the Savages' Huts

The hunting expedition. The forest below South River. Suggestions of the Professor concerning the importance of that section. The trail through the dense woods. Wild animals. Different varieties of game. Directing course by the sun. Character of the country. Discovery of native huts. A vegetable garden. The surprising contents of the huts. Accidentally finding paper containing writing. Other articles of interest among the rubbish. A mineral spring. A monogrammed silver cup. The return journey. Discussing the articles found.

CHAPTER XVII. The Grim Evidence in the Hills

Trying to decipher the writing traces on the paper. Conclusions. The Professor's journey. Prospecting in the hills. Discovery of numerous fissures in the rocks. A skeleton in one of them. The telltale arrows. Mute evidence of the character of the inhabitants of the island.

CHAPTER XVIII. Strange Discovery of a Companion Lifeboat

Work on the new boat. Variety of their work. The regular hunting day. The joke on the Professor. Old age. How old age becomes a habit. The discussion on hunting. Deciding where to go. Conclude to visit the forests to the west. Provisioning for the journey. Reaching the edge of the main forest, accompanied by Red Angel. In the proximity of the Falls. Decided to go in that direction. Reach the river. Searching for the spot where the boat was left and from which place it had been taken. No traces of the mooring place. Examining driftwood and debris along river bank. Amazing discovery of one of Investigator's boats. Speculation as to the mystery. Evidence that it came over the Falls. Disappearance of the lockers of the boat, similar to those on their own. Discussion as to the fate of their companions. Decide to seclude the boat. Sudden appearance of Red Angel in excitement. Following him back to the location of the wagon. Disappearance of the yaks and wagon.

GLOSSARY OF WORDS USED IN TEXT

Other books from THE NEW YORK BOOK COMPANY

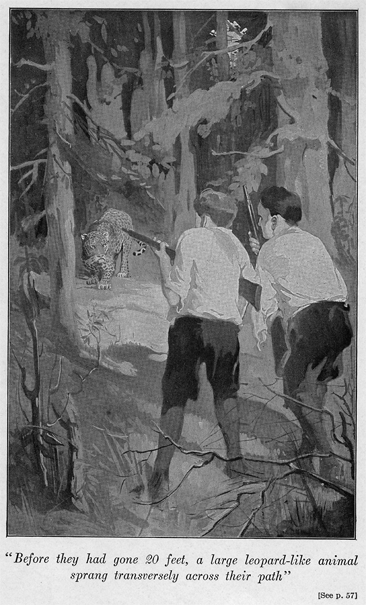

"Before they had gone 20 feet, a large leopard-like animal sprang transversely across their path"

"George saw his peril and now realized that he could not possibly reach a place of safety"

"'What is this? a party?' said the Professor. 'Yes; a birthday party,' said Harry"

"Red Angel saw George's design, and without saying a word he slowly descended"

12. Branch of the Camphor Tree

22. The Mysterious Brand on the Yak

27. Complete Battery with Connections

35. Chart Showing How the Boys Were Lost

"I wonder why the yaks are so wild and difficult to handle this morning?" said George, as he stopped the wagon and tried to calm them by soothing words.

At that moment Harry, who was in the lead, sprang back with a cry of alarm, and quietly, but with-evident excitement, whispered: "There are some big animals over to the right!"

The Professor was out of the wagon in an instant and moved forward with Harry. "You would better remain with the team, George," was the Professor's suggestion.

George Mayfield and Harry Crandall, two American boys, attached to a ship training school, had been shipwrecked, in company with an aged professor, on an unknown island, somewhere in the Pacific, over four months prior to the opening of this chapter; and, after a series of adventures, had been able, by ingenious means, to devise many of the necessaries of life from the crude materials which nature furnished them; and they were now on their third voyage of discovery into the unknown land.

For your information, a brief outline is given of a few of the things they had discovered, of some of their adventures, and of what they had made, and why they were now far out in the wilderness.

When they landed they had absolutely nothing, in the way of tools or implements. Neither possessed even a knife, so they had to get food and clothing and prepare shelter with the crudest sort of appliances.

By degrees they began to make various articles, found copper, iron and various ores, as well as lime-rock and grindstone formations. With these, and the knowledge of the Professor, they finally succeeded in making iron and copper tools and implements, built a water wheel, erected a sawmill, and eventually turned out a primitive pistol or gun.

During this time, however, they were interested in discovering what the island contained. The first voyage was on foot through a forest, where they saw an exciting combat between bears for the possession of a honey tree, and witnessed the death of one of them. By the accidental discovery of the honey tree they were supplied with an excellent substitute for sugar.

In the next voyage a large river was discovered to the south, which they named the South River. The second voyage was along that stream, until they reached a falls, where they were compelled to leave the crude boat which was made before starting on this voyage, and they proceeded on foot.

After a week's adventure in the forest they found a fire plot, which was the first indication that the island was inhabited. As up to this time they had no weapons but bows and arrows, which they had made, they returned home hurriedly. On the journey they had the fortune to capture a yak and her calf, and subsequently became possessors of a small herd, two of which they trained. A wagon was built and a store of provisions gathered in. A crude machine was constructed to weave the ramie fiber, the plant of which they found growing on the banks; in addition they had success in making felt cloth from the hair of the yak.

After providing many of the things which were necessaries, and several samples of firearms, as stated, they determined to go on their third voyage of discovery. During the various trips several mysterious and inexplainable things occurred. First, the fire on the banks of the Cataract River, about fifty miles from their home. Second, the disappearance of their boat, which had been left below the falls in South River; and, third, the removal of their flag and pole at Observation Hill, a half mile from their home, during the time they were absent on the third voyage.

They were now on their fourth voyage, and the incident mentioned on the opening page of this chapter related to the first large animal they had discovered.

In a short time Harry and the Professor returned from the search. "We have lost them, but shall undoubtedly find them later on," was all he said.

The forest was still to the south of them, and to the north the sea was now distant fully three or four miles, as the coast seemed to trend to the northwest, after passing the wild barley fields. The ground appeared to be more open and level, so a more southerly course was taken in that direction. Before night they emerged from the dense forest, which still continued to the right.

No stirring incidents occurred during the day, until night was approaching, when, on entering a straggling forest of detached trees and thick underbrush, George, who was in the lead, and acting the part of the scout, rushed back and held up a warning hand. The team stopped while Harry and the Professor quickly moved toward George.

"I have seen some orang-outans; come quickly."

Moving forwardly they could hear a plaintive cry, not unlike the wail of an infant. All stopped in surprise. The Professor was the first to speak: "That is a young orang. See if you can locate him."

As they moved still nearer the sound, there was a scampering of several orangs, and not fifty feet away was a pair of babies, struggling to reach the most convenient tree.

Harry pounced on the pair and caught one of them, which set up a vigorous shriek. The other, in the excitement, got too far beyond the reach of George, who, in his eagerness, was too busy watching Harry's captive to notice the other animal, and before he could reach the tree one of the grown orangs had reached the ground, gathered up the infant and again sprang up the tree.

"Give it some honey," said the Professor, laughing.

"What are the things good for, anyway?" asked Harry.

"Of course, you are not compelled to keep it, but while you have it feed and treat it well."

"What does it eat?"

"Principally nuts and fruit, as well as vegetables. If properly prepared they will eat almost everything man eats, except meats."

At first, as a matter of curiosity, they restrained him, and as it was near camping time for the night, the Professor suggested that it would be well to make camp close to the tree which had harbored the orang family.

After a good supper the Baby nestled up in the mattress, and was sound asleep in fifteen minutes. When the boys arranged the mattresses for the night, Baby did not seem at all disturbed, and he slept peacefully until morning.

After breakfast no effort was made to deprive the Baby of its liberty, but no attempt was made on his part to leave the wagon. He relished the honey and the other delicacies, all of which were undoubtedly, a surprise to him.

The parent orangs were in sight on the trees beyond, but made no demonstrations, although they saw the young one crawling and swinging on and around the wagon.

You may be sure that the petting Baby got was enough to spoil any infant. Probably, the parents saw the affection lavished on it, or knew that it was not curtailed of its liberty.

When they again set out on the march Baby kept a firm hold on the mattress, or lazily swung from the cross bars of the wagon top. It was having the time of its life.

Before noon of the next day, Baby began to act strangely. It would jump first to one side, then to the other. Harry, who was in the lead, was called up, and the wagon stopped. The antics of Baby looked like fear. Before Harry reached the wagon the Professor and George heard a shot, and the next moment something struck the canvas top and rolled to the ground. It was up in an instant and sprang to the back of one of the yaks, before the Professor, who was driving, could realize what was happening.

George was off the wagon in an instant, and seeing the strange animal on the back of the yak, drew his gun, and two shots rang out almost at the same instant.

When Harry turned back, at the call of the Professor, he saw the animal in the tree, which was then alongside of the wagon, and without waiting to give a warning, had shot at it, the bullet going through its forelegs. The result was it fell, striking the wagon, rolled over, and then sprang to the back of the yak. George's nimbleness in jumping from the wagon, and running around, enabled him to get in a shot at the same time the Professor fired. Both of their shots took effect, and it rolled to the ground.

"What is it?" asked George.

"A wildcat; no wonder the poor Baby was frightened!"

"How did Baby, inside of the wagon, know of the cat?"

"The wildcat is the mortal enemy of the orang-outan. While they fear to encounter the grown animals, they will attack the young, and the orangs seem to have the instinct of danger from that source born in them."

The Baby's nerves were unstrung with the din of the guns, and it was an hour before he could be calmed down. The wildcat was skinned, and it was days before the orang could be reconciled to the sight of the pelt or the smell of the animal.

"That is an instinct in certain animals. Nature has provided them with warnings of danger when their enemies are near."

"What a short tail the cat has," remarked George; "so unlike the tame cat."

"That, and the head, which is much larger and flatter than the common cat, as well as the shorter legs, show the distinguishing differences. Its color, as this one is, uniformly grayish-brown, with stripes running around the body, is a peculiarity found in the tame species, known as the 'tiger-cat,' to which they are the most closely allied."

Before nightfall fairly level ground was reached, and this being the third day, they judged their location was fully sixty miles due west of the Cataract. Far to the south and southeast the mountains could be distinctly seen, but the Professor did not think the ranges were very high.

In the far west the cloudy aspect of the sky prevented them from judging of the character of the land, but it had the appearance of mountains, as well.

"How far away are the mountains in the south, do you think?" asked the Professor.

"I estimate them at about five miles," was George's response.

"What is your idea, Harry?"

"I don't think George is far out of the way."

"Would you be surprised if I should put it at twenty-five miles, or more?"

"What makes you think so?"

"Appearances are always deceptive when you have nothing intervening to measure by."

"Is that the reason distances on water are always so deceptive?"

"Yes; have you ever noticed that you can judge distances better if the intervening landscape is rolling?"

"I think that is true in my case. But there is another thing I have noticed: When I am standing on the ground and looking up at an object, it never seems as far as when I am up there looking down: Why is that so?"

"That is simply the effect of habit, or familiarity. You are accustomed to look up at objects. The perspective, the altitude, and the appearance of the heights are natural things to you; but, when you are above, things below you have an entirely different perspective outline. Their arrangement is unfamiliar. Probably that is one of the reasons why we should always look upwardly in life, and not downwardly."

"But," inquired Harry, "is that the reason why some people, when at an elevation, like a tall building, or on a high precipice, say they feel like jumping down?"

"That is a species of paralysis, growing out of a sense of insecurity. It is purely an unnatural sensation, that temporarily disorganizes the nervous system. I knew a man who, whenever placed in such a position, could not speak."

They were now on what might be called the table land of the island. A broad plateau, with frequent groves, and any quantity of young trees scattered about everywhere, gave a most pleasing view. During the fourth day of the journey occasional little streams, flowing to the north, were crossed, and in the forenoon they had to halt for two hours and camp during the heaviest rainstorm which had fallen since they came to the island.

On the fifth day a broad river was sighted, flowing to the north, and before noon the banks were reached. Its width barred their further progress, unless a raft could be made large enough to take the team across. This was considered a hazardous task, and the distance from home was too great to take the risk. It was a larger stream than South River.

The usual rate of travel did not average two and a half miles an hour, and while the first and second days were vigorous ones, they were not so much disposed to hurry up now, and were taking the trip more leisurely, thus giving more time to the examination of trees and plants and flowers, and to investigating the geological formation of the country. The new river was not, in all probability, more than seventy miles from the Cataract home.

Beyond, fully a day's march, was the mountain chain—not a high range, but an elevation which showed a broken skyline. The mountains below the South River did not now seem so formidable; and directly to the south they could see no ranges or hill elevations. To the north the sea might be ten or fifty miles away. The river flowed past them at the rate of about two miles an hour.

That evening, while sitting on the bank, Harry had an idea. "We made a mistake in calling our home river the West River. Let us call this the West, and rename our stream the Cataract River."

"Very well; as George does not object, the Geographical Society will please take notice, and make the change."

George was of the impression that to settle the question of the direction they should take in their future explorations, was the most important thing to determine.

An entire day was spent in and about the vicinity of the river. New plants and shrubbery of various kinds were constantly sought for and examined—they fished and hunted; and on the morning of the third day it was decided to move on.

"We have not yet sighted any original inhabitants, and have found no signs of people living here; nevertheless, we had traces of a fire thirty or forty miles east of here. That is what puzzles me."

"I am in favor of following this stream to the north," was Harry's conclusion, "unless we make a raft and cross the river."

Harry's view finally prevailed, and at noon of that day they camped at the mouth of a little stream which flowed into the West River. Beyond was a forest, and on the opposite side of the West River the wood had all along been dense. At that point the trees did not come down to the stream, and there was considerable lowland between the river and the forest.

The Professor and George wandered up the banks of the little stream on a prospecting tour, as had been their constant practice. When they returned Harry knew something unusual had occurred from the excited appearance of George.

"What is it? Any animals?"

"No; only this." And George held up an arrow made of flint. The wooden portion of the arrow was really of good workmanship, and of hard, stiff wood.

"Where did you find this?"

"Not more than five hundred feet from here."

Harry looked at the Professor for an explanation, but he was silent. By common consent they now agreed upon making a more extended investigation of the vicinity for other traces, if possible. Within an hour Harry stumbled across the skull of an animal. This was not an unusual sight, as bones had been found at various places in their travels, but here was a specimen, lying on a rocky slope, with but little vegetation about it.

"I should like to know what animal this belonged to?"

The Professor examined the bones critically, without venturing an opinion. "What is this?" were his first words. Directly behind the ear cavity was a split or broken cleavage in which they found a round piece of dark wood.

"Get the bolo, George; we may find something interesting here." With a few strokes the skull was opened, and embedded within the brain receptacle was an arrow.

"This animal was, as you see, killed by the inhabitants of the island. I infer that there are several tribes living here."

The boys looked at each other in astonishment.

"Why do you think so?"

"This arrow is different in shape and in structure from the sample we found this morning."

The boys now noticed the difference.

"Do different tribes make their implements differently?"

"There is just as much difference among savages in the way they make their weapons and different implements, as among civilized people. Our customs differ; our manufactured articles are not the same; and sometimes the manner of using the tools is unlike; and the divergence is frequently so wide that it has been difficult in many cases to trace the causes and explain the reasons. Such an instance may be found in the Chinese way of holding a saw, with the teeth projecting from the sawyer. For years all tools and machinery made in England could be instantly recognized by those versed in manufacturing, on account of the bulk, as their tools were uniformly made larger and heavy, as compared with the French and American manufacture."

This conclusion verified the Professor's observation, and you may be sure that the new discovery gave an air of gravity to the camp which it did not have before.

"I also wanted to say to-day," was the Professor's last remark that night, "I am satisfied that there is no intimate intercourse between the different tribes on the island." The boys looked at each other without questioning, as usual; but the next morning, as soon as George awoke, his first observation was: "I can't understand what makes you think that the natives of the different tribes do not associate with each other."

"Simply for the reason that the styles of the arrows differ so greatly. With them, as with civilized people, the intermingling of the races should tend to make their tools and implements alike."

The next night, after the evening meal, they sat in the wagon until late, discussing their future course. It was now fully nine months since they left home. The thought that their parents and friends would consider them lost was the hardest thing to bear. Did the boys ever get homesick? I need not suggest such an idea to make it more real than it was to them. With beautiful home surroundings, loving parents and brothers and sisters, absence, uncertainty; the fear that they would never again be able to return; danger all about them; the belief that perils still awaited them, which fears were now, in all probability, to be realized, all these things did not tend to produce a pleasant perspective to the mind.

But the Professor was a philosopher. He knew that the human mind craved activity. If it could not be exercised in a useful direction it would invariably spend its energies in dangerous channels. He knew this to be particularly true of young people.

Boys are naturally inquisitive. Their minds are active, like their bodies. They must have exercise; why not direct it into paths of usefulness, where their accomplishments could be seen and understood by the boys themselves.

That thought is the parent of the manual training system, where the education imparted comes through the joint exercise of brain and muscle. Boys resent all work which comes to them under the guise of play; and all play which is labeled "work." But when there is a need for a thing, and the inquisitive nature of the boy, or his mental side, starts an inquiry, the manual, or the muscular part of him, is stimulated to the production of the article needed to fill that want.

The Professor did not force any information upon the boys, as will be noticed. It was his constant aim to let inquiry and performance come from them.

Could anything have been more stimulating or encouraging than the building of the water wheel, the sawmill, or the wagon? See what enjoyment and profit they derived from it. Thus far they had not given their time and the great enthusiasm to their various enterprises because of the money returns. Do you think it would have made their labors lighter, or the knowledge of their success any sweeter if they had been paid for their work?

The "Baby" went to sleep early, as was his custom now, and the boys and the Professor sat up later that night than usual, talking over their condition, and the situation as it appeared to them. The day had been exceedingly warm, following the rains.

Harry, who was seated facing the river, suddenly sprang up and excitedly grasped the Professor's arm, as he pointed across the river: "Look at that light!"

There, plainly in the distance, was a light, not stationary, but flickering, and, apparently, moving slightly to and fro.

"It seems as though it is at the edge of the woods," remarked George. The distance was fully a half mile away.

"It can't be possible that people are over there," said Harry, not so much in a tone of inquiry as of surprise. "How far do you think it is from here?"

"Probably one-half mile, or more. We might be able to learn something if we should fire a gun," was the Professor's reply.

The boys were naturally astonished at the boldness of this remark. Other lights now appeared, some dim, others brighter. The firing of a gun seemed to them a most hazardous thing to do, but no doubt the Professor had a reason for making the suggestion.

It was quite a time before either of the boys responded to this proposal. In their minds it was a daring enterprise.

"If we should fire a gun the noise would likely startle them, and the first impulse of the savages would be to extinguish the lights."

George, who had the spirit of adventure more strikingly developed than Harry, was the first to concur.

"I am going to try it at any rate; we might just as well know what we have to face now, as later on."

"So you are really going to shoot?" said the Professor.

"If you so urge it, yes."

"Then let me suggest what to do. All savages have a keen sense of direction. It is one of their chief accomplishments. You and Harry go back, up the river, a quarter of a mile, or so, and take with you one of our coverings. Then shoot behind the blanket, so the flash will not be seen, and I will remain here and watch the effect."

There was no delay in their preparations. Within fifteen minutes the shot rang out, and almost immediately thereafter every light had disappeared. The boys were also keen enough to note the extinguished lights, and returned to the Professor in a hurry.

"The disappearance of the lights is not conclusive evidence that human beings were there. It might have been a mere coincidence."

"Coincidence! What do you mean by that?"

"Did it not occur to you that the lights might be natural phenomena?"

"Of what?"

"Of phosphorescence."

"Do you mean 'will-o'-the-wisp'?"

"It is sometimes called by that name. It is caused by decaying vegetable matter, and exhibits itself in the form of gases of phosphorus, which appears to burn, but does not, like the vapor which is produced by rubbing certain matches in the dark."

"But how do you account for the disappearance after we shot?"

"I thought they might have disappeared naturally, after you fired, and, therefore, said it might have been a mere coincidence."

This explanation was not a satisfying one for the boys, and the Professor did not place much faith in it, for the following reasons:

"I believe it is our duty now to keep watches during the night, which we can do by turns, so that the sentinel will quietly awaken the next one in his turn, or both in the event of any unusual happening; and furthermore, we should make an early start in the morning."

George was the first watch, and, by agreement, Harry was to be the next, in two hours, for the second period. Before that time passed Baby was very restless, and George tried to soothe him; but before long he began crying. A lusty orang, however small, in a still night, makes an awfully loud noise. The boys never heard anything as loud and as frightful as that cry appeared to them.

All were awake, of course, but the Baby refused to be quieted for fully a quarter of an hour.

"Don't you think Baby's cries will direct the savages to us?"

"It is not at all likely. The savages have no doubt heard the cries many times. It is your imagination which is playing you tricks. Do you suppose the savages know we are here and have a captive orang?"

During the rest of the night they took sleep in snatches, and morning was long in coming. Harry had busied himself in getting a hasty breakfast while the others slept, and Baby was up leaping around nervously, and springing from branch to branch on the adjacent trees.

Having finished breakfast, the yaks were yoked, and before the sun was visible they were on their way to the north, as fast as the yaks could travel.

The whole camp partook of watchfulness now. Every hour and every mile they scanned the landscape, and, for further precaution, kept away from close proximity to the river bed. That was not a safe route, as enemies on the other side of the river would have an unobstructed view, whereas by traveling inland, but within sight of the river, they could still view the banks of the stream.

"The scout who leads the way must go a certain distance, then make observations in all quarters. He must take particular note of objects which afford places of concealment, and the eye must be alert enough to observe every undue movement in limb or leaf. Sound is one of the things he must cultivate. A noise of any kind should be analyzed. A scout once told me that on one occasion during the war, his life was saved because he saw one limb of a tree move more than an adjoining one. At another time, in trailing through a forest, he saw a leaf on the ground, differing in color from those around it. In walking along he had noticed that some of the leaves he overturned had the same color, and inferred that as no wind had been blowing, and all the trees were bare, something must have turned the leaf, and subsequent events confirmed his reasonings."

The boys quickly learned their lessons. Each knew that every step forward meant an entrance to an unknown world.

During the day, following the night when the mysterious lights appeared in the lowland directly to the west and beyond the river, they passed through several dense forests. George, who was in the lead at this time, emerged from the thickest wood into a rather open plain. He saw the river make a long circular sweep, and directly ahead noticed a coast line of steep hills which marked the shore of the river on the opposite side.

Harry and the Professor, who were behind with the team, had not yet reached the clearing. As George passed into the open space he saw an animal cross his path, and without waiting to inform the others, he shot. This alarmed Harry, who was out of the wagon without waiting for any word from the Professor. Immediately after George's shot was heard, they plainly heard another from the direction of the river ahead of them. The Professor, too, jumped from the wagon and followed Harry. George fired a second time, and another shot came from the river. Harry turned and looked back at the Professor in amazement.

"What can that mean? Did you hear four shots?"

"Yes; run ahead, and find George."

In a brief time both boys returned. "George says he did not hear the shots from the river."

"They were as plain as your own."

George did not know how to explain it. The Professor moved forward. "Let us get out into the opening."

As they reached the clearing beyond the wood, and the Professor saw the steep bluffs beyond, he laughed, and looking at the hills, said:

"That is where the shots came from."

His amusing smile was reassuring, although his words were not.

"That bluff over there is about 2,000 feet from here. We had better find out what he is doing there."

"Two thousand feet; and somebody there!"

"I did not say somebody was there, but that the noise of the shot came from that place."

"Do you think it was simply an echo?"

"Undoubtedly; didn't you hear Baby's cries repeated?"

"But how do you know that the hills are 2,000 feet away?"

"Sound travels at the rate of 1,040 feet per second, and I made a mental calculation that it took four seconds for Baby's cries to come back from the hills. In that case the sound had to go to the hills and back again, and it would, therefore, take two seconds to travel one way. Do you understand?"

"Oh, yes; that is perfectly clear."

The land now became more rolling, and was occasionally broken by ravines; and sometimes they had difficulty in getting their yaks and wagon across and over the rough ground.

Fallen trees were numerous; there were little mounds here and there, made by the remains of uprooted trees, which had long ago decayed, all of which made their traveling laborious and slow.

Here wild animals became more abundant, and wild game was found on every side. Several good shots by the boys replenished their larder with bird meat.

"See that bear!" cried Harry in great excitement.

The boys, as well as the Professor, were out with their guns at once. "Follow him up quickly now," and the Professor could hardly keep pace with them. The bear did not seem to be greatly frightened, and when Harry, who was ahead, stopped and aimed his gun for a shot, he was less than a hundred feet away. The shots from the two boys came close together, and bruin stopped in surprise, then, with a snarl, turned around and in a lumbering, shuffling movement started for the boys.

If either shot had taken effect it was not noticeable. The boys turned to run, one going to the right and the other to the left. This did not seem to disconcert him in the least, as he went right on. He had seen the Professor, who stopped and sprang to one side and bringing up his gun awaited the charge of the bear.

The boys, encouraged by the tactics of the bear in avoiding them, turned again, because they now appreciated that the Professor was in the bear's path.

"Don't shoot, boys; let him come nearer."

When he came within fifteen feet the Professor fired, and the boys also shot. The bear reared up, gave a terrific growl and again shambled forward, this time making a beeline for the wagon. This was too much for the yaks; they turned, almost upsetting the wagon, and Baby commenced to shriek in the most approved fashion.

Neither George nor Harry could wait any longer. They followed and rushed past the Professor, who now had the only loaded gun.

"Take this, Harry; your guns are not loaded."

Harry turned and grasped it and without stopping went in pursuit. Before he had reached the former location of the wagon the animal ran into a tree, which threw him back on his haunches, and after several efforts to raise himself, fell over on his side.

The Professor's shot had entered his left eye, but the vitality of the animal was such that he ran nearly a hundred feet before it took effect.

The yaks were soon rounded up. It is a wonder that more damage was not done. Aside from the displacement of their bedding, and the ditching of some of the cooking utensils, everything was found intact.

"That was a rather ill-advised adventure on our part. We should have guarded our supplies; but I was as much to blame as you were. We must be more careful in the future."

On every side the rough character of the land was more apparent, and it was becoming more and more difficult to find tracks which were suitable for the team.

"This matter of going further with our wagon is now getting to be a serious problem. I think we should turn to the right and move in the direction of home, or direct our course southeast toward the mountains on the other side of South River."

"I think we have discovered enough on this trip," was Harry's conclusion.

George assented, so that on the twelfth day of their journey the yaks were directed towards home. For two days the travel was southeasterly, through the most broken and tortuous paths, crossing innumerable small streams and rivulets on their course. During this troublesome part of their journey the weather was stormy, with numerous rains, some of them so prolonged as to prevent traveling for hours, so that they made less than twenty miles during that time.

On the third day, however, the ground became more level and less broken, the sun appeared, and they felt happy at the thought of getting back again.

Thus far in their wanderings they had kept their reckonings, as well as they could without instruments, and that evening the chart was again consulted, as usual. The drawing (Figure 4) shows how it looked with the course of their journey.

When they started from the Cataract home at nine o'clock in the morning, they made an observation of the sun, using a vertical pole so as to get the exact direction of the falling shadow. A distant object was then selected, a prominent tree, as far off as possible. The Professor had prepared an adjustable bevel square, which was simply two legs hinged together at one end, by means of a set screw, like a compass.

"Now, boys, I want to show you how we can make a fairly good chart simply by the use of this adjustable square, and this will also be of service to us in measuring heights of objects, as well as directing our course. It is now nine o'clock, and you will see that our pole (A) throws a shadow to the southwest. Supposing now, we direct the first leg of our journey to that large tree (C), to the west of us. If, now, we put one leg (D) of our rule along the shadow line, and the other leg (E) along the sight of the line (F), which goes to the tree, we shall find that the distance across between the ends of the bevel square is just two feet. It happens in this case that the tree (C) is due west from our observation point; so we have at nine o'clock each morning a means whereby we can always determine the true east and west."

"But supposing we lose our reckoning during the day, on account of cloudy weather, or by going through the forest, where we cannot make observations?"

"We could, probably, travel an entire day in one general direction, without being more than a few miles out of our course, north or south, and our direction immediately made out the next day."

"Wouldn't it be a good idea to prepare angles at different times of the day, in the forenoon and in the afternoon?"

"That is the proper thing to do, so as to enable you to make observations from the angles at all times. A chart could then be made from that which would show at a glance what the value of each angle is."

"We shall certainly have to do that; but what interests me as much is, to know how far we have traveled. Can we also tell that by the sun?"

"Yes; but to do so will depend on the accuracy of the observation. For the present, with only a single instrument, the bevel square, we must be content to make our calculations exactly at midday, when the shadow points due south. Or, in the northern hemisphere, when the shadow points due north. I want you, in the meantime, to think over that problem, as it is a very interesting one, and we will take it up when we are not so tired."

It was a relief to get on fairly even ground again, where it would not be necessary to make turns and twists around all sorts of obstructions, to say nothing of ravines and water courses. On the evening of the fifteenth day, calculations showed that they were halfway back from the point farthest west, but they still had no knowledge of their distance from the sea, which undoubtedly was to the east, or, possibly, northeast. West River flowed to the north, and all the streams crossed flowed north or northeasterly, how far, it was impossible to say.

Two days afterward the scene changed somewhat. There had been little wind during the journey thus far; but now breezes sprang up for two successive days, at about four in the afternoon, which came from the north.

"I think the sea is not far away."

"Why do you think so, Professor?"

"Did you notice the warm breezes this evening, and also last night at about the same time?"

"Why should the breezes from the ocean blow warm winds to us at this time of the year when it ought to be cold?"

"It is not at all likely that the breezes are any warmer than at other times of the year. Heat is merely a relative matter. We feel the difference of the wind temperatures principally for the reason that when the vast body of water in moving ocean streams is giving off its heat, it imparts it to the atmosphere and modifies it, so that as it sweeps over the land it is warmer than the natural temperature."

The following day, late in the afternoon, they caught the first glimpse of the sea, and it was welcomed. A camp was made for the night in the open, and with an early start next morning the explorers reached the last hill to the west of the cataract.

When they arrived home, which was not without considerable misgiving, owing to their long absence, they were overjoyed at finding everything at the house in perfect order, but their yaks were missing.

This was, at first, a sore grief to them, especially to George, who considered it to be a personal loss. Milk was a luxury, as well as a necessity, to him. The team was now all that remained of their herd.

"It is strange we did not see any of them on our journey."

It was a surprising thing to see their water wheel in motion, although they had taken considerable pains to push the wheel back so the blades would not be in contact with the water. It was found that the Cataract River was much swollen with the rains, so that the water had come into contact with the wheel.

As the team was now the sole reliance, so far as the herd was concerned, the Professor suggested that they should thereafter keep the team within the enclosure, so as to prevent their straying, as they might, in the absence of their fellows, try to escape.

The present house, which had been built since coming to the Cataract, had originally only one room, and two of the sides were formed, as stated, by the walls of the right-angled rocks, the room being about ten feet square.

After the water wheel was built and put in and the sawmill erected, they were enabled to get lumber, and an extension twelve by fifteen feet was put up, to be used as a sleeping and living room.

A small addition was also added, which was converted into a kitchen, so that the original enclosure could be used as a storeroom.

A sort of roadway passed the new addition, and beyond was the Cataract, not fifty feet away. Directly below the Cataract another building was put up, in one end of which was the sawmill, and at the other end was a sort of shed in which they had put up a furnace, blacksmith shop, and a kind of primitive foundry.

Within the workshop work was done during the rainy weather, and it was made as comfortable as possible.

They were now back, ready to take up active life again. Not that the past nineteen days were inactive ones. By no means; but they loved the work which every day had brought to them in the past, and were happy in the thought that they were accomplishing things of the greatest value to themselves. They were really tired, and for a few days did little active work.

"Do you think we have accomplished very much on our trip?" was George's inquiry the evening of their arrival.

"We saw a light, didn't we?"

The boys laughed, when they saw that the Professor said it with a broad smile. They had no doubt, but he wished to convey the impression that they had seen a light, just as many others had, without being able to understand it. George saw the point at once. "I hope we may be able to profit by it. But, really, how much more do we know than we knew a month ago?"

"The West River, the bear, the wildcat, the Baby; why, you had entirely forgotten him and his cute ways. We learned that there are, without doubt, savage tribes on the island. I am inclined to think the trip has taught us something."

The Baby was an interesting little chap. He would sit up at the table with innocent blinking eyes, and gravely imitate the motions of eating, especially if there was something sweet in sight.

That night a startling noise was heard, made by the unmistakable tramp of animals passing their home. Harry was the first to open the small port, which served as a window.

"Hurrah for our yaks!" There they were, back again, with two additional calves. The next morning they were contentedly lying down outside of the enclosure which held their team.

Didn't "Baby" enjoy the milk! So did the boys. The cattle had not strayed away far, but merely found a better feeding ground. The barley field had been exhausted.

"If there is anything I missed on the journey, it was the clock. I don't like guessing at time," was George's comment, after they had fully gone over their experiences on the trip.

"I suppose," said Harry, "we can make watches, but they will be rather cumbersome, because our tools are not very delicate. What do you think, Professor?"

"That is for you to decide. I am of the opinion that as we have a pretty good clock, and as it is susceptible of being nicely regulated, we could put in our time more profitably in doing some other much needed work."

"What is that? I am willing to do anything?"

"We have some hides that need tanning, and the fresh bear pelt must be cured. As our herd of cattle has increased we might slaughter several of them, so that we can dehair the pelts and tan them all at the same time; then we need some contrivances to enable us to determine the location of our island; and also to afford a means to measure distances in traveling, because, I presume, you are just as anxious as ever to know what we have on the island."

There was a hearty assent to this view of the situation.

"I want to do everything we can to learn about our surroundings," was George's response; "and I would like to have the fire, and the mystery of the boat, and the flagpole cleared up."

The thing which most interested Harry after their return, was the disposition of the barley which they had harvested before the last journey was undertaken. This was welcomed by the Professor as a necessity. Accordingly a level floor was provided, on which was spread a thick layer of barley stalks, and this was beaten with flails. A flail is simply a piece of wood about the thickness and length of a broom handle. To this was attached, by means of leather strips, a club, not unlike a baseball bat, so the bat portion swung on the end of the handle, and in this manner the barley was threshed out.

Before the invention of the threshing machine this was the universal method of threshing, although it was also customary to tramp it out with horses, which were driven over a thick layer of the straw hour after hour.

In one day they threshed out five bushels; beautiful golden grain. The boys who had often seen wheat and oats threshed out, never appreciated grain as they did their own, acquired in the manner this was.

The grinding-stones, which they had previously made, were then set to work, making the meal, or flour, as they preferred to call it. Heretofore flour had been a luxury, and there was a longing for it, so it was decided to make up the first batch of bread.

You may be sure that the Professor did not object to activities in this direction; and they had long ago learned his peculiarities, particularly not to venture any information voluntarily, so the boys concluded to make bread on their own knowledge. They had often seen bread made.

"All you have to do is to mix up the flour with a little water, put some rising in it and let it stand until it raises and then bake it."

"That's all well enough, Harry, I suppose we can do all that, but where shall we get the yeast?"

"That's so; yeast is necessary; I suppose we shall have to see the Professor, after all; but hold on; I have seen sour milk used, George."

"So have I; but I think mother used something else with it."

"Well, there we are; who would think we could have trouble with such a simple thing as making bread?"

The Professor came smiling. "You want to make bread, and the only thing that troubles you is to raise it so it will be light?"

"Wouldn't it be bread if you didn't raise it? You know the Jews used unleavened, or unraised, bread."

"But we want regular bread, of course, and we want to know what to use to raise it with."

"I don't see that you particularly need anything."

"Why not?"

"If you let the dough stand in a temperature of between 90 and 120 degrees for a certain time, fermentation will take place, and it can then be baked."

"But why should it ferment?"

"Bread raising is merely fermentation. All flour is largely composed of starch. The high temperature, of 100 degrees or over, causes the starch to turn first into sugar, then into alcohol and carbonic acid, and the gases thus formed force their way up through the dough, causing it to swell, as you have often noticed."

Without further instructions the boys began the making of bread. Shortly afterwards the Professor appeared laughing immoderately.

"Come and see the Baby."

The boys were out in an instant. The Baby was in the storeroom adjoining, and discovered the honey pot. It was a "sight." He sat there, both hands and arms covered with honey, blinking innocently, and licking his fingers and arms with the greatest joy imaginable.

"You little rascal, you are getting too fat now," was George's greeting; but Baby didn't mind. He knew George by this time.

The bread raised, but it, too, was a "sight." It was full of holes and at some places the bread had no appearance of having "come up," which is kitchen parlance for unraised bread.

"What is the matter with it, Harry?"

"Did you work it before you put it into the oven?"

"I forgot that."

When the Professor saw the sample he divined the trouble at once.

"Of course, you have to work it, for the reason that 'working' distributes the gases through the mass. I think you made the mistake in working it and then putting it into the oven immediately."

"How long should it stand after working?"

"That depends on the amount of carbonic gas which is developed. When it first raises the gas forces its way through the dough irregularly, and by then working it the gas is broken up and distributed evenly, so that if the mass is allowed to stand after the second working every part of it will be leavened. When it is then put into the oven, the heat at first causes a more rapid expansion, or raising, of the dough, and as the heat increases, fermentation is stopped, and the baking process sets the dough. The result is tiny little holes throughout the bread, where the gases were."

"But why do they use yeast if it can be done without?"

"Because it makes the raising process easier, and more positive."

"Is it the carbonic acid which makes some bread sour?"

"Yes; sour bread results if the fermentation is continued too long."

It was George's custom each day to watch the movements of the yaks, because it was through them that they learned of the barley field which was such a source of usefulness to them. One day while out on an expedition of this kind, he wandered down to the rock cliffs, probably five hundred feet west of Observation Hill, this hill, it will be remembered, being close to the landing place when they were cast on the island. The sea was heavy and the tide coming in. He could not help reflecting, and his home, his parents, and his beautiful life there came up to his inward vision. The dreary pounding sea made him homesick, and for the first time he burst into tears. But George was a brave boy. He knew that crying was useless, and felt a little ashamed of himself.

His reflections were not long, however. To his left he saw a peculiar sight. At every inrushing wave there was a report like a cannon shot, followed by a tremendous stream and spray of water, which was shot out to sea high up above the waves.

This was an extraordinary sight to him, and unexplainable. The story was related to the Professor that evening.

"That was an air pocket in the rocks."

"What is an air pocket?"

"From your description it is probably a large cave, so situated in the wall of the cliff, that at a certain period the waves will entirely close the mouth. When the wave dashes up against the cliff and closes the mouth of the cave, the water tries to enter the cave. In doing so air is compressed in the pocket, and when the wave again starts to go out to sea, and the pressure is partly taken away, the compressed air explodes, so to say, and shoots out the water into a spray, and also causes the noise you heard."

"How much can air be compressed?"

"It is not known definitely how far. It has been compressed to less than one-eight-hundredth of its bulk. It is the most elastic substance known."

"Isn't water compressible?"

"No; if it had been compressible you would not have had that exhibition at the air pocket."

"What is that rocking?" cried Harry, jumping out of his couch, one night.

The Professor was awake and had noticed it.

"Probably an earthquake."

The rocking continued for several minutes, and then gradually subsided. They boys were so excited that sleep was out of the question, for the time, besides the shaking might again recur at any moment.

"Do you think there is any danger, Professor?"

"It is impossible to say what will happen when these symptoms in the earth's crust take place."

"Are there not some instruments which indicate the extent and possible dangers of the quakes?"

"There is an instrument called the seismograph, which records the vibratory movements of the earth, and also locates the distances at which the shocks are from the observer, but there is nothing to indicate what the extent and probable dangers are."

"Is it true that the interior of the earth is in a liquid state?"

"Such has been the theory for many years; but it is now believed to be a solid—a body with a density five and a half times greater than water."

"If that is the case, why is it that the molten metal flows out of the volcanoes?"

"There may be fissures in the earth, or portions less dense than others which, by the general disarrangements of the adjacent parts, and by the enormous pressure exerted by the force of gravity, are contracted, and the movement causes such friction and intense heat as to liquefy the rock. In doing so a large amount of gas is evolved, the movement of which causes the disturbance of the earth's crust, which manifests itself to us in the form of earthquakes. At the same time the confined gases seek an outlet, which they find at the weakest part, and the volcanoes spout forth the lava, flame, and gases. There is an undoubted connection between earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Earthquakes usually precede volcanic action. This internal combustion is going on at all times, and is only more violent at some period than at others. The lava in the Crater of Stromboli has been in a liquid state for more than two thousand years."

"Before we left home I saw in a paper that some scientist described the kind of rock and other matter which was seven miles down in the earth."

"Was anyone ever down as far as that?"

"No; a little over a mile is as far as man has actually penetrated the earth."

"Then, I should like to know how geologists can tell with any certainty what the rock is like several miles down?"

"That is known just as positively as though a hole had been dug down that distance."

"I don't see how that is possible."

"I am going to make you a sketch which you can examine at leisure, that will show how he knows. Assuming that the earth has a crust—that is, the outside or cooled part, let the first sketch (Figure 10) represent this crust, before the mountains and valleys were formed. The slightly curved horizontal lines merely represent the different layers of the crust, such as rock, clay, coal, slate, and the like. When the cooling process took place the earth grew smaller within, so that the crust was forced together.

"The second sketch (Figure 11) shows this crust forced together, so that when the upheaval took place, two mountain ranges, A and B, were formed, with a valley (C) between them, and the broken lines (D), where the crust separated, were exposed, and by that means examinations can be readily made way down into the crust, without ever leaving the surface of the earth."

As it was understood that the boys should take at least a day each week for hunting, particularly since such sport would develop expertness in the use of their weapons, an early start was made on the day selected, which was within a week of the time they returned home.

Ever since the disappearance of the boat left at the falls in South River, there was some anxiety on that score. It was a frequent topic of conversation, and after they left home it was by a mutual impulse that they wended their way south, taking a trail which was now familiar to them.

"See here, Harry, I should like to go to the place where I discovered South River, and where I had the experience with the snake and the strange animal, which frightened me so."

"Then we must go to the left, because, you remember, you came up between these hills, and crossed the stream where I found you."

It was about three miles across from the Cataract house, but less from their original home. When they reached the river the surroundings were very much unlike anything George had seen before, and he could not identify the place where the ramie plant had been found.

The ocean could be seen plainly from their position, and George thought they were too far east, which proved to be the case.

"Here it is, Harry; here is a low place, and you can see the ramie plant all about here. I am sure of it."

"Is this the place you lost the hatchet?"

"So I did: I'll show you the place." But he failed to find the hatchet. Subsequently Harry stumbled across it, but it was found some distance from the place where George declared he lost it.

"Let us try to cross the river. We can do it if we find a couple of logs."

At a bend of the river they found a lot of driftwood caught in the roots of a tree, and after some work a number of pieces were cut and laid crosswise on each other.

After the experiences of several expeditions of this kind, to say nothing of the exploring trips, the need of the bolo and ropes impressed itself on their minds. They were never without them.

The river at this point was fully one hundred feet wide, but by the aid of long poles the raft was not long in making the trip. After properly securing it they took up their weapons and at once made a dive for the interior.

The trees were fairly thick, and before going very far Harry checked George with the statement that there was game ahead, as he had heard rustling sounds in the leaves.

Both were now looking forward intently, expecting and hoping that some game worthy of attention would appear. Whenever they stopped, the animal, or what it was, would stop, to resume its motion whenever they moved. This was getting to be decidedly interesting, and at the same time trying to the hunters. The distance was fully a mile from the river. The noise which came from the slight rustling of the leaves and the occasional breaking of a twig was growing acute.

"Are we hunting or being hunted?" said George, under breath.

Not forgetting the Professor's story of the hunter's careful scrutiny of leaves, they adopted that plan, but it gave them no clue. Whatever it was, it was in front of them, but they were unable to get a glimpse of it.

Once, by agreement, they stopped and were silent for several minutes. The silence was just as profound and continued as their own. It was getting tense, when George hit upon a plan.

"Let us be quiet for a minute or so, and then suddenly bound forward and give a whoop. I think that will frighten him, and enable us to sight him."

"Before doing that get the guns ready for a shot, and don't fire too soon. Don't get excited. Remember the Professor's warning; a shot close at hand, deliberately aimed, is more positive than a dozen shots excitedly fired at a distance."

When all was ready Harry whispered, "Now!"

With a whoop both started forwardly on a run as fast as the dense underbrush would permit. Before they had gone twenty feet a large leopard-like animal sprang transversely across their path, then, seeing the boys, crouched for a spring. The guns were cocked and ready, and it is a wonder that in the excitement there was not a premature shot.

"Now, steady," said Harry. "Aim, fire!" and the moment both shots rang out. Harry cried excitedly, "Now for the other guns!"

The other guns were not necessary then. The animal gave a savage growl and bounded to the left, and after they had time to recover, both moved toward the spot.

"We have hit him, sure," was George's exultant shout. "See the blood on the leaves. My! he was as big as a lion!"

"Let's follow him," was Harry's determination. And off they started, the blood tracks plainly showing the way. Not a further view was obtainable of the animal, and in less than a quarter of a mile all blood traces disappeared, to the chagrin of both.

They directed their steps toward the river, but within two hundred feet of the spot where they had last stopped, George stepped back and cried: "There he is now, right ahead of us."

"Let us be careful now; he may be angry." There was no alternative but to fire. The shots were almost at the same instant, and to their great relief the animal, after a single leap, fell down without a groan.

The approach was cautious, because experience had not taught them whether it was safe immediately to make an examination of the body. After some hesitation they went up closer, and when all doubts as to his death had been dispelled a careful examination was made.

They found only a single shot wound between the shoulders.

Here was a dilemma, surely enough. The river fully a half mile away, if not more, and the brute too large to carry, made them hesitate about attempting to skin it in the absence of the Professor.

"I wish we knew what kind of an animal it is. We had better go home and bring the Professor back with us in the morning."

So taking note of the surroundings, to familiarize themselves with the location, they hurried back to the river, and rafted themselves over. The Cataract home was reached about four o'clock, after one of the most adventurous days spent on the island, although, in some respects, not as exciting as their earlier experiences. They had begun to be veterans. They were not merely boys.

Naturally, the Professor heard a stirring tale, and when it was all told over and over again, he told them he thought that undoubtedly the region beyond the river would turn out to be their hunting preserves, a statement which the boys did not forget to profit by, as we shall see later on.

"I wonder why we haven't seen more animals north of the South River? There have been very few in this section," was George's observation.

"Undoubtedly the mountain region affords them safer retreats, and it is one of the things which indicate to me that we shall find that section very wild, and when we are in shape to do so may be able to have some interesting and exciting times in that part of our domain," was the Professor's response.

"But in South Africa wild animals are found in abundance on the plains."

"True; but they have very thick brush, or cover, owing to the luxurious growth of vegetation. That affords them means for covering their retreat when attacked."

Following out the usual custom while on expeditions of this kind, they constantly, while on the way, stopped to examine specimens of plants and trees.

"Here is a branch, with the flower, of a tree, and the smell is very familiar."

"That is from a camphor tree; do you not recognize it?"

"So it is; I know camphor is good for a great many things."

"It would take some time to enumerate the things camphor is used for. Indeed, there are so many that Raspail, a French chemist, years ago found a system of medicine largely on the camphor plant, claiming that it was nature's universal remedy."

"Here is a sample of plant which we found growing in bushes; there were also a few trees with the flowers. It is bitter to the taste."

"This is the Calisaya, one of the varieties of the plant from which the well-known quinine is made. There are at least forty varieties of the plant. This is indeed a valuable find. But I see you have some beans there?"

"Yes; are they good to eat?"

"In South America, particularly in the Argentine Republic, it is eaten as a fruit, and the seeds are fed to cattle. Our yaks would relish them."

"We saw them everywhere on the other side of the river."