The Project Gutenberg eBook, Two Suffolk Friends, by Francis Hindes Groome This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Two Suffolk Friends Author: Francis Hindes Groome Release Date: February 13, 2007 [eBook #20576] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TWO SUFFOLK FRIENDS***

Transcribed from the 1895 William Blackwood and Sons edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

by

FRANCIS HINDES GROOME

william

blackwood and sons

edinburgh and london

mdcccxcv

All Rights reserved

p. ito

MOWBRAY DONNE

the friend of these two friends

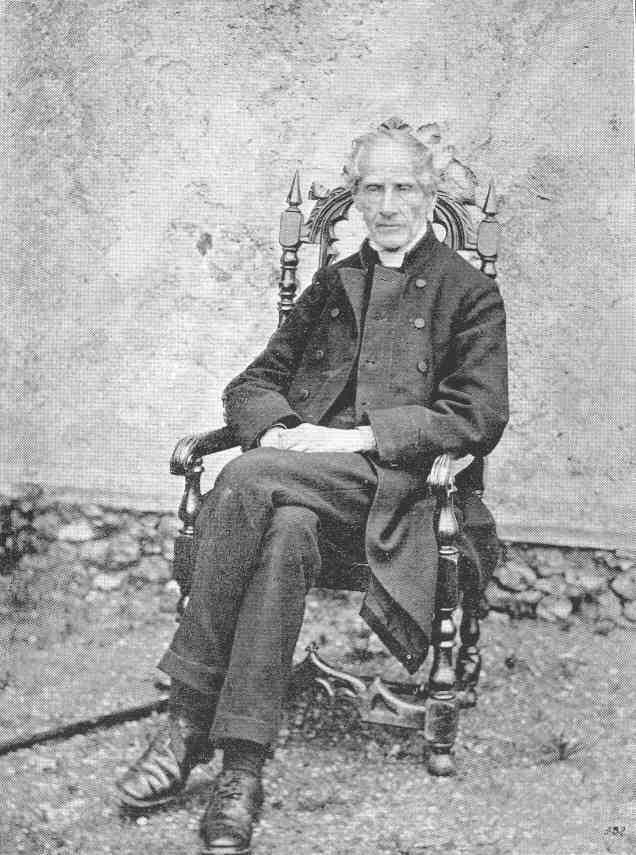

Published originally in ‘Blackwood’s Magazine’ four and six years ago, and now a good deal extended, these two papers, I think, will be welcome to many in East Anglia who knew my father, and to more, the world over, who know FitzGerald’s letters and translations. I may say this with the better grace and greater confidence, as in both there is so much that is not mine, and both have already brought me so many kindly letters—from Freshwater, Putney Hill, Liverpool, Cambridge, Aldeburgh, Italy, the United States, India, and “other nations too tedious to mention.” All the illustrations p. viiihave been made in Bohemia from photographs taken by my elder sister, except Nos. 6, 8, and 9, the first of which is from the well-known photograph of FitzGerald by Cade of Ipswich, whilst the other two I owe to my friend, Mr Edward Clodd.

F. H. G.

The chief aim of this essay is to present to a larger public than the readers of a country newspaper my father’s Suffolk stories; but those stories may well be prefaced by a sketch of my father’s life. Such a sketch I wrote shortly after his death, for the great ‘Dictionary of National Biography.’ It runs thus:—

“Robert Hindes Groome, Archdeacon of Suffolk, was born at Framlingham in 1810. Of Aldeburgh ancestry, he was the second son of the Rev. John Hindes Groome, ex-fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge, and rector for twenty-six years of Earl Soham and Monk Soham in Suffolk. From Norwich school he passed to Caius College, Cambridge, where he graduated B.A. in 1832, M.A. in 1836. In 1833 he was ordained to the Suffolk curacy of Tannington-with-Brandish; in 1835 travelled through Germany as tutor to Rafael Mendizabal, the son of the p. 4Spanish ambassador; in 1839 became curate of Corfe Castle, Dorsetshire; and in 1845 succeeded his father as rector of Monk Soham. Here in the course of forty-four years he built the rectory-house and school, restored the fine old church, erected an organ, and re-hung the bells. He was Archdeacon of Suffolk from 1869 till 1887, when failing eyesight forced him to resign, and when the clergy of the diocese presented him with his portrait. He died at Monk Soham, 19th March 1889. Archdeacon Groome was a man of wide culture—a man, too, of many friends. Chief among these were Edward FitzGerald, William Bodham Donne, Dr Thompson of Trinity, and Henry Bradshaw, the Cambridge librarian, who said of him, ‘I never see Groome but what I learn something new.’ He read much, but published little—a couple of charges, a sermon and lecture or two, some hymns and hymn-tunes, and a good many articles in the ‘Christian Advocate and Review,’ of which he was editor from 1861 to 1866. His best productions are his Suffolk stories: for humour and tenderness these come near to ‘Rab and his Friends.’”

An uneventful life, like that of most country clergymen. But as Gainsborough and Constable took their subjects from level East Anglia, as Gilbert White’s Selborne has little to distinguish it above other parishes in Hampshire, [5] p. 5so I believe that the story of that quiet life might, if rightly told, possess no common charm. I have listened to my father’s talks with Edward FitzGerald, with William Bodham Donne, and with two or three others of his oldest friends; such talks were like chapters out of George Eliot’s novels. His memory was marvellous. It seems but the other day I told him I had been writing about Clarendon; and “Clarendon,” he said, “was born, I know, in 1608, but I forget the name of the Wiltshire parish his birthplace. Look it up.” I looked it up, and the date was 1608; the parish (Dinton) was, sure enough, in Wiltshire. Myself I have had again to consult an encyclopædia for both date and place-name, but he remembered the one distinctly and the other vaguely after possibly thirty years. In the same way he could recall the whole plot of a play which he had not seen for half a century. Holcroft’s ‘Road to Ruin,’ thus, was one that he once described to me. He was a master of the art, now wellnigh lost, of “capping verses”; and he had a rare knowledge of the less-known Elizabethan dramatists. In his first Charge occurs a quotation from an “old play”; and one of his hearers, Canon “Grundy,” inquired what play it might be. “Ford’s,” said my father, “‘’Tis p. 6pity she’s no better than she should be.’” And the good man was perfectly satisfied. But stronger than his love of Wordsworth and music, of the classics and foreign theology, was his love of Suffolk—its lore, its dialect, its people. As a young man he had driven through it with Mr D. E. Davy, the antiquary; and as archdeacon he visited and revisited its three hundred churches in the Norwich diocese during close on a score of years. I drove with him twice on his rounds, and there was not a place that did not evoke some memory. If he could himself have written those memories down! He did make the attempt, but too late. This was all the result:—

“Oct. 23, 1886.

“I cannot see to read, but as yet I can see to write. That is, I can see the continuous grey line of writing, and can mechanically write one word after another. But if I leave off abruptly, I cannot always remember what was the last word that I wrote, and read it generally I cannot.

“I should be thankful for being able to write at all, and I hope I am; but I am not enough thankful. The failure of my sight has been very gradual, but of late it has been more sudden. Three months ago I could employ myself in reading; now I cannot, save with a book, such as the p. 7Prayer-book, with which I am well acquainted, and which is of clear large type. So that as yet I can take my duty.

“I was born at Framlingham on January 18, 1810, so that I am now nearly seventy-seven years old. The house still stands where I was born, little if at all changed. It is the first house on the left-hand side of the Market Hill, after ascending a short flight of steps. My father, at the time of my birth, was curate to his brother-in-law, Mr Wyatt, who was then rector of Framlingham. I was the younger of two sons, my brother Hindes being thirteen months older than I was.

“As we left Framlingham in 1813, my recollections of it are very indistinct. I have an impression of being taken out to see a fire; but as I have since been told that the fire happened a year before I was born, I suppose that I have heard it so often spoken of that in the end I came to believe that I myself had seen it. Yet one thing I can surely remember, that, being sent to a dame’s school to keep me out of mischief, I used to stand by her side pricking holes in some picture or pattern which had been drawn upon a piece of paper.

“In 1813, after the death of Mr Wyatt, my father took the curacy of Rendlesham, where we lived till the year 1815. The rector of Rendlesham at that time was Dr p. 8Henley, [8] who was also principal of the East India College of Haileybury, so that we lived in the rectory, Dr Henley rarely coming to the parish. That house remains unchanged, as I shall have occasion to tell. Lois Dowsing was our cook, and lived nearly forty years in my father’s service—one of those faithful servants who said little, but cared dearly for us all.

“Of Rendlesham I have clear recollection, and things that happened in it. It was there I first learnt to read. My mother has told me that I could not be taught to know the letter H, take all the pains she could. My father, thinking that the fault lay in the teacher, undertook to accomplish the task. Accordingly he drew, as he thought, the picture of a hog, and wrote a capital H under it. But whether it was the fault of the drawing—I am inclined to think that it was—or whether it was my obstinacy, but when it was shown me, I persisted in calling it ‘papa’s grey mare.’

“There was a high sandbank not far from the house, through which the small roots of the bushes growing protruded. My brother and I never touched these. We believed that if we pulled one of them, a bell would ring and the devil would appear. So we never pulled them. p. 9In a ploughed field near by was a large piece of ground at one end, with a pond in the middle of it, and with many wild cherry-trees near it. I can remember now how pretty they were with their covering of white blossoms, and the grass below full of flowers—primroses, cowslips, and, above all, orchises. But the pond was no ordinary one. It was always called the ‘S pond,’ being shaped like that letter. I suspect, too, that it was a pond of ill repute—perhaps connected with heathen worship—for we were warned never to go near its edge, lest the Mermaid should come and crome us in. Crome, as all East Anglians know, means ‘crook’; and in later years I remember a Suffolk boy at Norwich school translated a passage from the ‘Hecuba’ of Euripides, in which the aged queen is described as ‘leaning upon a crooked staff,’ by ‘leaning upon a crome stick,’ which I still think was a very happy rendering.

“Not far also from the rectory was a cottage, in which lived a family by the name of Catton. Close to the cottage was a well, worked by buckets. When the bucket was not being let down, the well was protected by a cover made of two hurdles, which fell down and met in the middle. These hurdles, be it noted, were old and apparently rotten. One day I was playing near the well, and nothing would, I suppose, satisfy me but I must p. 10climb up and creep over the well. In the act of doing this I was seen by Mrs Catton, who saved me, perhaps, from falling down the well, and carried me home, detailing the great escape. Well do I remember, not so much the whipping, as the being shut up in a dark closet behind the study. So strong was and is the impression, that, on visiting Rendlesham as archdeacon, when I was sixty years old, on going up to the rectory-house I asked especially to see this dark closet. There it was, dark and unchanged since fifty-six years ago; and at the sight of it I had no comfortable recollection, nor have I now.

“In the year 1814 was a great feast on the Green—a rejoicing for the peace. One thing still sticks to my memory, and that is the figure of Mrs Sheming, a farmer’s wife. She was a very large woman, and wore a tight-fitting white dress, with a blue ribbon round her waist, on which was printed ‘Peace and Plenty.’

“In the year 1815 we spent the summer in London, in a house in Brunswick Square, which overlooked the grounds of the Foundling Hospital. Three events of that year have always remained impressed on my memory. The first was the death of little Mary, our only sister. She must have been a strangely precocious child, since at barely three years old she could wellnigh read. My mother, p. 11who died fifty-two years after in her eighty-third year, on each year when Mary’s death came round took out her clothes, kept so long, and, after airing them, put them away in their own drawer. The second event, which I well remember, was being taken out to see the illuminations for the battle of Waterloo. I can perfectly remember the face of Somerset House, all ablaze with coloured lamps. The third event was the funeral of a poor girl named Elizabeth Fenning.” [11]

And there those childish reminiscences broke off—never to be resumed. But from recollections of my father’s talk—and he loved to talk of the past—I will attempt to write what he himself might have written; no set biography, but just the old household tales.

After the visit to London the family lived a while at Wickham Market, where my father saw the long strings of tumbrils, laden with Waterloo wounded, on their way from Yarmouth to London. Then in 1818 they settled at Earl Soham, my grandfather having become rector of that parish and Monk Soham. His father, Robinson p. 12Groome, the sea-captain, had purchased the advowson of Earl Soham from the Rev. Francis Capper (1735-1818), whose long tenure [12] of his two conjoint livings was celebrated by the local epigrammatist:—

“Capper, they say, has bought a horse—

The pleasure of it bating—

That man may surely keep a horse

Who keeps a Groome in waiting.”

It was in the summer-house at Earl Soham that my father, a very small boy, read ‘Gil Blas’ to the cook, Lois Dowsing, and the sweetheart she never married, a strapping sergeant of the Guards, who had fought at Waterloo. And it was climbing through the window of this summer-house that he tore a big rent in his breeches (he had just been promoted to them), so was packed off to bed. That afternoon my grandfather and grandmother were sitting in the summer-house, and she told him of the mishap and its punishment. “Stupid child!” said my grandfather; p. 13“why, I could get through there myself.” He tried, and he too tore his small-clothes, but he was not sent to bed.

With his elder brother, John Hindes (afterwards Rector of Earl Soham), my father went to school at Norwich under Valpy. The first time my grandfather drove them, a forty-mile drive; and when they came in sight of the cathedral spire, he pulled up, and they all three fell a-weeping. For my grandfather was a tender-hearted man, moved to tears by the Waverley novels. Of Valpy my father would tell how once he had flogged a day-boy, whose father came the next day to complain of his severity. “Sir,” said Valpy, “I flogged your son because he richly deserved it. If he again deserves it, I shall again flog him. And”—rising—“if you come here, sir, interfering with my duty, sir, I shall flog you.” The parent fled.

The following story I owe to an old schoolfellow of my father’s, the Rev. William Drake. “Among the lower boys,” he writes, “were a brother of mine, somewhat of a pickle, and a classmate of his, who in after years blossomed into a Ritualistic clergyman, and who was the son of a gentleman, living in the Lower Close, not remarkable for personal beauty. One morning, as he was coming up the school, the sound of weeping reached old Valpy’s ears: straightway he stopped to investigate whence it proceeded. ‘Stand up, sir,’ he cried in a voice of thunder, for he hated p. 14snivelling; ‘what is the matter with you?’ ‘Please, sir,’ came the answer, much interrupted by sobs and tears, ‘Bob Drake says I’m uglier than my father, and that my father is as ugly as the Devil.’”

Another old Norwich story may come in here, of two middle-aged brothers, Jeremiah and Ozias, the sons of a dead composer, and themselves performers on the pianoforte. At a party one evening Jeremiah had just played something, when Ozias came up and asked him, “Brother Jerry, what was that beastly thing you were playing?” “Ozias, it was our father’s,” was the reproachful answer; and Ozias burst into tears.

When my father went up to Cambridge, his father went with him, and introduced him to divers old dons, one of whom offered him this sage advice, “Stick to your quadratics, young man. I got my fellowship through my quadratics.” Another, the mathematical lecturer at Peterhouse, was a Suffolk man, and spoke broad Suffolk. One day he was lecturing on mechanics, and had arranged from the lecture-room ceiling a system of pulleys, which he proceeded to explain,—“Yeou see, I pull this string; it will turn this small wheel, and then the next wheel, and then the next, and then will raise that heavy weight at the end.” He pulled—nothing happened. He pulled again—still no result. “At least ta should,” he remarked.

p. 15Music engrossed, I fancy, a good deal of my father’s time at Cambridge. He saw much of Mrs Frere of Downing, a pupil of a pupil of Handel’s. Of her he has written in the Preface to FitzGerald’s ‘Letters.’ He was a member of the well-known “Camus”; and it was he (so the late Sir George Paget informed my doctor-brother) who settled the dispute as to precedence between vocalists and instrumentalists with the apt quotation, “The singers go before, the minstrels follow after.” He was an instrumentalist himself, his instrument the ’cello; and there was a story how he, the future Master of Trinity, and some brother musicians were proctorised one night, as they were returning from a festive meeting, each man performing on his several instrument.

He was an attendant at the debates at the Cambridge Union, e.g., at the one when the question debated was, “Will Mr Coleridge’s poem of ‘The Ancient Mariner’ or Mr Martin’s Act tend most to prevent cruelty to animals?” The voting was, for Mr Martin 5, for Mr Coleridge 47; and “only two” says a note written by my father in 1877, “of the seven who took part in the debate are now living—Lord Houghton and the Dean of Lincoln. How many still remember kind and civil Baxter, the harness-maker opposite Trinity; and how many of them ever heard him sing his famous song of ‘Poor Old Horse’? Yet for p. 16pathos, and, unhappily in some cases, for truth, it may well rank even with ‘The Ancient Mariner.’ And Baxter used to sing it so tenderly.”

Meanwhile, of the Earl Soham life—a life not unlike that of “Raveloe”—my father had much to tell. There was the Book Club, with its meetings at the “Falcon,” where, in the words of a local diarist, “a dozen honest gentlemen dined merrily.” There were the heavy dinner-parties at my grandfather’s, the regulation allowance of port a bottle per man, but more ad libitum. And there was the yearly “Soham Fair,” on July 12, when my grandfather kept open house for the parsons or other gentry and their womankind, who flocked in from miles around. On one such occasion my father had to squire a new-comer about the fair. The wife of a retired City alderman, she was enormously stout, and had chosen to appear in a low dress. (“Hillo, bor! what are yeou a-dewin’ with the Fat Woman?”—one can imagine the delicate raillery.)

A well-known Earl-Sohamite was old Mr P---, who stuttered and was certainly eccentric. In summer-time he loved to catch small “freshers” (young frogs), and let them hop down his throat, when he would stroke his stomach, observing, “B-b-b-b-eautifully cool.” He was a staunch believer in the claims of the “Princess Olive.” p. 17She used to stay with him, and he always addressed her as “Your Royal Highness.” Then, there was Dr Belman. He was playing whist one evening with a maiden lady for partner. She trumped his best card, and, at the end of the hand, he asked her the reason why. “Oh, Dr Belman” (smilingly), “I judged it judicious.” “Judicious! Judicious!! JUDICIOUS!!! You old fool!” She never again touched a card. Was it the same maiden lady who was the strong believer in homœopathy, and who one day took five globules of aconite in mistake for three? Frightened, she sent off for her homœopathic adviser—he was from home. So, for want of a better, she called in old Dr Belman. He came, looked grave, shook his head, said if people would meddle with dangerous drugs they must take the consequences. “But, madam,” he added, “I will die with you;” and, lifting the bottle of the fatal globules, swallowed its whole contents. [17]

To the days of my father’s first curacy belongs the story of the old woman at Tannington, who fell ill one p. 18winter when the snow was on the ground. She got worse and worse, and sent for Dr Mayhew, who questioned her as to the cause of her illness. Something she said made him think that the fault must lie with either her kettle or her tea-pot, as she seemed, by her account, to get worse every time she drank any tea. So he examined the kettle, turned it upside down, and then, in old Betty’s own words, “Out drop a big töad. He tarned the kittle up, and out ta fell flop.” Some days before she had “deeved” her kettle into the snow instead of filling it at the pump, and had then got the toad in it, which had thus been slowly simmering into toad-broth. At Tannington also they came to my father to ask him to let them have the church Bible and the church key. The key was to be spun round on the Bible, and if it had pointed at a certain old woman who was suspected of being a witch, they would have certainly ducked her.

A score of old faded letters, close-written and crossed, are lying before me: my father wrote them in 1835 to his father, mother, and brother from Brussels, Mainz, Leipzig, Dresden, Prague, Munich, &c. At Frankfurt he dined with the Rothschilds, and sat next the baroness, “who in face and figure was very like Mrs Cook, and who spoke little English, but that little much to the purpose. For one dish I must eat because ‘dis is p. 19Germany,’ and another because ‘dis is England,’ placing at the word a large slice of roast-beef on my plate. The dinner began at half-past two, and lasted three mortal hours, during the first of which I ate because I was hungry, during the second out of politeness, and during the third out of sheer desperation.” Then there is a descent into a silver-mine with the present Lord Wemyss (better known as Lord Elcho), a gruesome execution of three murderers, and a good deal besides of some interest,—but the interest is not of Suffolk.

During his six years’ Dorset curacy my father was elected mayor of the little borough of Corfe Castle; and it was in Dorset, on 1st February 1843, that he married my mother, Mary Jackson (1815-93), the youngest daughter of the Rev. James Leonard Jackson, rector of Swanage, and of Louisa Decima Hyde Wollaston. Her father, my grandfather, was a great taker of snuff; and one blustery day he was walking upon the cliffs when his hat blew off. He chased it and chased it over two or three fields until at last he got it in the angle of two stone walls. “Aha! my friend, I think I have you now,” said my grandfather, and proceeded to take a leisurely pinch of snuff, when a puff of wind came and blew the hat far out to sea. There are many more Dorsetshire stories that recur to my memory; but neither here is the interest p. 20of Suffolk. So to Suffolk we will come back, like my father in 1845, in which year he succeeded his father as rector of Monk Soham.

Monk Soham is a straggling parish of 1600 acres and 400 inhabitants. [20] It lies remote to-day, as it lay remote in pre-Reformation times, when it was a cell of St Edmundsbury, whither refractory monks were sent for rustication. Hence its name (the “south village of the monks”); and hence, too, the fish-ponds for Lenten fare, in the rectory gardens. Three of them enclose the orchard, which is planted quincunx-wise, with yew hedge and grass-walk all round it. The “Archdeacon’s Walk” that grass-walk should be named, for my father paced it morning after morning. The pike and roach would plash among the reeds and water-lilies; and “Fish, fish, do your duty,” my father would say to them. Whereupon, he maintained, the fish always put out their noses and answered, “If you do your duty, we do our duty,”—words fully as applicable to parson as to sultan.

The parish has no history, unless that a former rector, Thomas Rogerson, was sequestrated as a royalist in 1642, and next year his wife and children were turned out of doors by the Puritans. “After which,” Walker tells us, p. 21“Mr Rogerson lived with a Country-man in a very mean Cottage upon a Heath, for some years, and in a very low and miserable Condition.” But if Monk Soham has no history, its church, St Peter’s, is striking even among Suffolk churches, for the size of the chancel, the great traceried east window, and the font sculptured with the Seven Sacraments. The churchyard is pretty with trees and shrubs—those four yews by the gates a present from FitzGerald; and the rectory, half a mile off, is almost hidden by oaks, elms, beeches, and limes, all of my father’s and grandfather’s planting. Else the parish soon will be treeless. It was not so when my father first came to it. Where now there is one huge field, there then would be five or six, not a few of them meadows, and each with pleasant hedgerows. There were two “Greens” then—one has many years since been enclosed; and there was not a “made” road in the entire parish—only grassy lanes, with gates at intervals. “High farming” has wrought great changes, not always to the profit of our farmers, whose moated homesteads hereabouts bear old-world names—Woodcroft Hall, Blood Hall, Flemings Hall, Crows Hall, Windwhistle Hall, and suchlike. “High farming,” moreover, has swallowed up most of the smaller holdings. Fifty years ago there were ten or a dozen farms in Monk Soham, each farm with its p. 22resident tenant; now the number is reduced to less than half. It seems a pity, for a twofold reason: first, because the farm-labourer thus loses all chance of advancement; and secondly, because the English yeoman will be soon as extinct as the bustard.

Tom Pepper was the last of our Monk Soham yeomen—a man, said my father, of the stuff that furnished Cromwell with his Ironsides. He was a strong Dissenter; but they were none the worse friends for that, not even though Tom, holding forth in his Little Bethel, might sometimes denounce the corruptions of the Establishment. “The clargy,” he once declared, “they’re here, and they ain’t here; they’re like pigs in the garden, and yeou can’t git ’em out.” On which an old woman, a member of the flock, sprang up and cried, “That’s right, Brother Pepper, kitch ’em by the fifth buttonhole!” [22] Tom went once to hear Gavazzi lecture at Debenham, and next day my father asked him how he liked it. “Well,” he said, “I thowt I should ha’ beared that chap they call Jerry Baldry, but I din’t. Howsomdiver, this one that spŏok fare to laa it into th’ owd Pope good tidily.” Another time my father said something to p. 23him about the Emperor of Russia. “Rooshur,” said Tom; “what’s that him yeou call Prooshur?” And yet again, when a concrete wall was built on to a neighbouring farm-building, Tom remarked contemptuously that he “din’t think much of them consecrated walls.” Withal, what an honest, sensible soul it was!

Midway between the rectory and Tom Pepper’s is the “Guildhall,” an ancient house, though probably far less ancient than its name. It is parish property, and for years has served as an almshouse for ten or a dozen old people. My father used to read the Bible to them, and there was a black cat once which would jump on to his knees, so at last it was shut up in a cupboard. The top of this cupboard, however, above the door, was separated from the room only by a piece of pasted paper; and through this paper the cat’s head suddenly emerged. “Cat, you bitch!” said old Mrs Wilding, and my father could read no more. Nay, his father (then in his last illness) laughed too when he heard the story.

The average age of those old Guildhall people must have been much over sixty, and some of them were nearly centenarians—Charity Herring, who was always setting fire to her bed with a worn-out warming-pan, and James Burrows, of whom my father made this jotting in one of his note-books: “In the year 1853 I buried James p. 24Burrows of this parish at the reputed age of one hundred years. Probably he was nearly, if not altogether that age. Talking with him a few years before his death, I asked if his father had lived to be an old man, and he said that he had. I asked him then about his grandfather, and his answer was that he had lived to be a ‘wonnerful owd man.’ ‘Do you remember your grandfather?’ ‘Right well: I was a big bor when he died.’ ‘Did he use to tell you of things which he remembered?’ ‘Yes, he was wery fond of talking about ’em: he used to say he could remember the Dutch king coming over.’ James Burrows could not read or write, nor his father probably before him: so that this statement must have been based on purely traditional grounds. Assume he was born in 1755 he would have been a ‘big bor,’ fifteen years old, in 1770; and assume that his grandfather died in 1770 aged ninety-six, this would make him to have been born in 1675, fourteen or fifteen years before William of Orange landed.”

Then there were Tom and Susan Kemp. He came from somewhere in Norfolk, the scene, I remember, of the ‘Babes in the Wood,’ and he wore the only smock-frock in the parish, where the ruling fashion was “thunder-and-lightning” sleeve-waistcoats. Susan’s Sunday dress was a clean lilac print gown, made very p. 25short, so as to show white stockings and boots with cloth tops. Over the dress was pinned a little black shawl, and her bonnet was unusually large, of black velvet or silk, with a great white frill inside it. She was troubled at times with a mysterious complaint called “the wind,” which she thus described, her finger tracing the course it followed within her: “That fare to go round and round, and then out ta come a-raspin’ and a-roarin’.” Another of her ailments was swelled ankles. “Oh, Mr Groome!” she would say, “if yeou could but see my poare legs, yeou’d niver forget ’em;” and then, if not stopped, she would proceed to pull up her short gown and show them. If my father had been out visiting more than to her seemed wise, she would, when he told her where he had been to, say: “Ah! there yeou go a-rattakin’ about, and when yeou dew come home yeou’ve a cowd, I’ll be bound,” which often enough was the case. Susan’s contempt was great for poor folks dressing up their children smartly; and she would say with withering scorn, “What do har child want with all them wandykes?”—vandykes being lace trimmings of any sort. Was it of spoilt children that she spoke as “hectorin’ and bullockin’ about”?—certainly it was of one of us, a late riser, that she said, “I’d soon out-of-bed har if I lived there.”

p. 26Susan’s treatment of Harry Collins, a crazy man subject to fits, was wise and kind. Till Harry came to live with the Kemps, he had been kept in bed to save trouble. Susan would have no more of bed for him than for ordinary folks, but sent him on many errands and kept him in excellent order. Her commands to him usually began with, “Co’, Henry, be stirrin’;” and he stood in wholesome awe of her, and obeyed her like a child. His fits were curious, for “one minute he’d be cussin’ and swearin’, and the next fall a-prayin’.” Once, too, he “leapt out of the winder like a roebuck.” Blind James Seaman, the other occupant of Susan’s back-room, came of good old yeoman ancestry. He wore a long blue coat with brass buttons; and his favourite seat was the sunny bank near our front gate.

In the room over Susan Kemp’s lived Will Ruffles and his wife, a very faithful old couple. The wife failed first. She had hurt herself a good deal with a fall down the rickety stairs. Will saw to her to the last, and watched carefully over her. The schoolmistress then, a Miss Hindmarsh, took a great liking for the old man; and a friend of hers, a widow lady in London, though she had never seen him, made him a regular weekly allowance to the end of his life—two shillings, half-a-crown, and sometimes more. This gave Will many little comforts. Once p. 27when my sister took him his allowance, he told her how, when he was a young man, a Gipsy woman told him he should be better off at the end of his life than at the beginning; and “she spŏok truth,” he said, “but how she knew it I coon’t säa.” Will suffered at times from rheumatism, and had great faith in some particular green herb pills, which were to be bought only at one particular shop in Ipswich. My sister was once deputed to buy him a box of these pills, and he told her afterwards, “Them there pills did me a lot of good, and that show what fŏoks säa about rheumatics bein’ in the boones ain’t trew, for how could them there pills ’a got into the boones?” He was very fond of my father, whom he liked to joke with him. “Mr Groome,” he once said, “dew mob me so.”

Will, like many other old people in the parish, believed in witchcraft,—was himself, indeed, a “wise man” of a kind. My father once told him about a woman who had fits. “Ah!” old Will said, “she’ve fallen into bad hands.” “What do you mean?” asked my father; and then Will said that years before in Monk Soham there was a woman took bad just like this one, and “there wern’t but me and John Abbott in the place could git her right.” “What did you do?” said my father. “We two, John and I, sat by a clear fire; and we had to bile p. 28some of the clippins of the woman’s nails and some of her hair; and when ta biled”—he paused. “What happened?” asked my father; “did you hear anything?” “Hear anything! I should think we did. When ta biled, we h’ard a loud shrike a-roarin’ up the chimley; and yeou may depind upon it, she warn’t niver bad no more.”

Once my father showed Will a silhouette of his father, old Mr Groome of Earl Soham, a portly gentleman, dressed in the old-fashioned style. “Ruffles, who is this?” he asked, knowing that Will had known his father well, and thinking he would recognise it. After looking at it carefully for some time, Will said, “That’s yar son, the sailor.” My eldest brother at that time might be something over twenty, and bore not the faintest resemblance to our grandfather; still, Will knew that he had been much abroad, and fancied a tropical sun might have blackened him.

By his own accounts, Will’s feats of strength as a younger man, in the way of reaping, mowing, &c., were remarkable; and there was one great story, with much in it about “goolden guineas,” of the wonderful sale of corn that he effected for one of his masters. At the rectory gatherings on Christmas night Will was one of the principal singers, his chef-d’œuvre “Oh! silver [query p. 29Sylvia] is a charming thing,” and “The Helmingham Wolunteers.” That famous corps was raised by Lord Dysart to repel “Bony’s” threatened invasion; its drummer was John Noble, afterwards the wheelwright in Monk Soham. Once after drill Lord Dysart said to him: “You played that very well, John Noble;” and “I know’t, my lord, I know’t,” was John’s answer—an answer that has passed into a Suffolk proverb, “I know’t, my lord, I know’t, as said John Noble.”

Mrs Curtis was quite a character—a little woman, with sharp brown eyes that took in everything. Her tongue was smooth, her words were soft, and yet she could say bitter things. She had had a large family, who married and settled in different parts. One son had gone to New Zealand—“a country, Dr Fletcher tell me, dear Miss, as is outside the frame of the earth, and where the sun go round t’other way.” It was for one of her sons, when he was ill, that my mother sent a dose of castor-oil; and next day the boy sent to ask for “some more of Madam Groome’s nice gravy.” Another boy, Ephraim, once behaved so badly in church that my father had to stop in his sermon and tell Mrs Curtis to take her son out. This she did; and from the pulpit my father saw her driving the unfortunate Ephraim before her with her umbrella, banging him with it first on one side and p. 30then on the other. Mrs Curtis it was who prescribed the honey-plaster for a sore throat. “Put on a honey-plaster, neighbour dear; that will draw the misery out of you.” And Mrs Curtis it was who, having quarrelled with another neighbour, came to my father to relate her wrongs: “Me a poor lone widow woman, and she ha’ got a father to protect her.” The said father was old James Burrows, already spoken of, who was over ninety, and had long been bedridden.

Mrs Mullinger was a strange old woman. People said she had an evil eye; and if she took a dislike to any one and looked evilly at their pigs, then the pigs would fall ill and die. Also, when she lived next door to another cottage, with only a wall dividing the two chimneys, if old Mrs Mullinger sat by her chimney in a bad temper, no one on the other side could light a fire, try as they might.

Phœbe Smith and her husband Sam lived in one of the downstair rooms. At one time of her life Phœbe kept a little dame’s school on the Green. One class of her children, who were reading the Miracles, were called “Little Miracles”; and whenever my father went in, “Little Miracles” were called up by that name to read to him. Old Phœbe had intelligence above the common; she read her Bible much, and thought over it. She was fond, too, p. 31of having my sister read hymns to her, and would often lift her hands in admiration at any passage she particularly liked. She commended a cotton dress my sister had on one day when she went to see her—a blue Oxford shirting, trimmed with a darker shade. “It is a nice solemn dress,” she said, as she lifted a piece to examine it more closely; “there’s nothing flummocky about it.”

Among the other Guildhall people were old Mrs “Ratty” Kemp, widow of the Rat-catcher; [31] old one-eyed Mrs Bond, and her deaf son John; old Mrs Wright, a great smoker; and Mrs Burrows, a soldier’s widow, our only Irishwoman, from whom Monk Soham conceived no favourable opinion of the Sister Isle. Of people outside the Guildhall I will mention but one, James Wilding, a splendid type of the Suffolk labourer. He was a big strong man, whose strength served him one very ill turn. He was out one day after a hare, and a farm-bailiff, meeting him, tried to take his gun; James resisted, and snapped the man’s arm. For this he got a year in Ipswich jail, where, however, he learnt to read, and formed a strong attachment for the chaplain, Mr Daniel. Afterwards, whenever any of us were driving over to Ipswich, and James met us, he would always say, “If yeou see Mr p. 32Daniel, dew yeou give him my love.” Finally, an emigration agent got hold of James, and induced him to emigrate, with his wife, his large family, and his old one-legged mother, to somewhere near New Orleans. “How are you going, Wilding?” asked my father a few days before they started. “I don’t fare to know rightly,” was the answer; “but we’re goin’ to sleep the fust night at Debenham” (a village four miles off), “and that’ll kinder break the jarney.” They went, but the Southern States and the negroes were not at all to their liking, and the last thing heard of them was they had moved to Canada.

So James Wilding is gone, and the others are all of them dead; but some stories still remain to be cleared off. There was the old farmer at the tithe dinner, who, on having some bread-sauce handed to him, extracted a great “dollop” on the top of his knife, tasted it, and said, “Don’t chüse none.” There was the other who remarked of a particular pudding, that he “could rise in the night-time and eat it”; and there was the third, who, supposing he should get but one plate, shovelled his fish-bones under the table. There was the boy in Monk Soham school who, asked to define an earthquake, said, “It is when the ’arth shug itself, and swallow up the ’arth”; and there was his schoolmate, who said that “America was discovered by British Columbia.” There p. 33was old Mullinger of Earl Soham, who thought it “wrong of fŏoks to go up in a ballune, as that fare [33] so bumptious to the Almighty.” There was the actual balloon, which had gone up somewhere in the West of England, and which came down in (I think) the neighbouring parish of Bedfield. As it floated over Monk Soham, the aeronaut shouted, “Where am I?” to some harvesters, who, standing in a row, their forefingers pointed at him, shouted back, “Yeou’re in a ballune, bor.” There was old X., who, whenever my father visited him, would grumble, talk scandal, and abuse all his neighbours, always, however, winding up piously with “But ’tis well.” There was the boy whom my father put in the stocks, but who escaped by unlacing his “high-lows,” and so withdrawing his feet. There was the clergyman, preaching in a strange church, who asked to have a glass of water in the pulpit, and who, after the sermon, remarked to the clerk in the vestry, “That might have been gin-and-water, John, for all the people could tell.” And, taking the duty again there next Sunday, he found to his horror it was gin-and-water: “I took the hint, sir—I took the hint,” quoth John, from the clerk’s desk below. There was the Monk Soham woman who, when she got a letter from her son in Hull, told the curate that “that did give me a tarn at fust, p. 34for I thought that come from the hot place.” There was another Monk Soham woman who told my sister one day that she had been reading in the Bible “about that there gal Haggar,” and who, after discussing the story of Hagar, went on, “When that gal grew up she went and preached to some fooks in a city that were livin’ bad lives.” My sister did not know about this, so inquired where she had found it, and she turned to the Book of the Prophet Haggai—Hagar and Haggai to her were one and the same. There was the manufacturer of artificial manures who set up a carriage and crest; and a friend asked my father what the motto would be. “Mente et manu res,” was the ready answer. There was the concert at Ipswich, where the chairman, a very precise young clergyman, announced that “the Rev. Robert Groome will sing (ahem!) ‘Thomas Bowling.’” The song was a failure; my father each time was so sorely tempted to adopt the new version. There was the old woman whom my father heard warning her daughter, about to travel for the first time by rail, “Whativer yeou do, my dear, mind yeou don’t sit nigh the biler.” There was the old maiden lady, who every morning after breakfast read an Ode of Horace; and the other maiden lady, a kinswoman of my father’s, who practised her scales regularly long after she was sixty. p. 35She, if you crushed her in an argument, in turn crushed you with, “Well, there it is.” There was much besides, but memory fails, and space.

From country clergyman to country archdeacon may seem no startling transition; yet it meant a great change in my father’s tranquil life. For one thing it took him twice a-year up to London, to Convocation; and in London he met with many old friends and new. Then there were frequent outings to Norwich, and the annual visitations and the Charge. On the first day of his first visitation, at Eye, there was the usual luncheon, and the usual very small modicum of wine. Lunch over, the Rev. Richard Cobbold, the author of ‘Margaret Catchpole,’ proposed my father’s health in a fervid oration, which wound up thus: “Gentlemen, I call upon you to drink the health of our new archdeacon,—to drink it, gentlemen, in flowing bumpers.” It sounded glorious, but the decanters were empty; and my father had to order (and pay for) two dozen of sherry. At an Ipswich visitation there was the customary roll-call of the clergy, among whom was a new-comer, a Scotchman, Mr Colquhoun. “Mr—, Mr—,” faltered the apparitor, coming unexpectedly on this uncouth name; suddenly he rose a-tiptoe and to the emergency,—“Mr Cockahoon.”

In one of the deaneries my father found a churchyard p. 36partly sown with wheat. “Really, Mr Z---,” he said to the incumbent, “I must say I don’t like to see this.” And the old churchwarden chimed in, “That’s what I säa tew, Mr Archdeacon; I säa to our parson, ‘Yeou go whatin’ it and whatin’ it, why don’t yeou tater it?’” This found its way into ‘Punch,’ with a capital drawing by Charles Keene, whom my father met often at FitzGerald’s. But there is another unrecorded story of an Irish clergyman, the Rev. “Lucius O’Grady.” He had quarrelled with one of his churchwardens, whose name I forget; the other’s was Waller. So my father went over to arbitrate between the disputants, and Mr “O’Grady” concluded an impassioned statement of his wrongs with “Voilà tout, Mr Archdeacon, voilà tout.” “Waller tew,” quoth churchwarden No. 1; “what ha’ he to dew with it?” And there was the visit to that woful church, damp, rotten, ruinous. The inspection over, the rector said to my father, “Now, Mr Archdeacon, that we’ve done the old church, you must come and see my new stables.” “Sir,” said my father, “when your church is in decent order, I shall be happy to see your new stables.” And “the next time,” he told me, “I really could ask to see them.”

Two London reminiscences, and I have done. A p. 37former Monk Soham schoolmistress had married the usher of the Marlborough Street police court. My father went to see them, and as he was coming away, an officious Irishman opened the cab-door for him, with “Good luck to your Rivirince, and did they let you off aizy?” And once my father was waiting on one of the many platforms of Clapham Junction, when suddenly a fashionably dressed lady dropped on her knees before him, exclaiming, “Your blessing, holy Father.” “God bless me!” cried my father,—then added quietly, “and you too, my dear lady.”

So at last I come to my father’s own Suffolk stories. In 1877-78 I made my first venture in letters as editor for the ‘Ipswich Journal’ of a series of “Suffolk Notes and Queries.” They ran through fifty-four numbers, my own set of which is, I fancy, almost unique. I had a goodly list of contributors—all friends of my father’s—as Mr FitzGerald, Mr Donne, Captain Brooke of Ufford, Mr Chappell, Mr Aldis Wright, Bishop Ryle, and Professors Earle, Cowell, and Skeat. Of them I was duly proud; still, my father and I wrote, between us, two-thirds of the whole. He was the “Habitans in Alto” (High Suffolk, forsooth), alias “Rector,” alias “Philologus,” “Hippicus,” &c.—how we used to laugh at p. 38those aliases. Among his contributions were three papers on the rare old library of Helmingham Hall (Lord Tollemache’s), four on Samuel Ward, the Puritan preacher of Ipswich, three on Suffolk minstrelsy, and these sketches written in the Suffolk dialect. Of that dialect my father was a past-master; once and once only did I know him nonplussed by a Suffolk phrase. This was in the school at Monk Soham, where a small boy one day had been put in the corner. “What for?” asked my father; and a chorus of voices answered, “He ha’ bin tittymatauterin,” which meant, it seems, playing at see-saw. I retain, of course, my father’s own spelling; but he always himself maintained that to reproduce the dialect phonetically is next to impossible—that, for instance, there is a delicate nuance in the Suffolk pronunciation of dog, only faintly suggested by dawg.

Fŏoks alluz säa as they git old,

That things look wusser evry day;

They alluz sed so, I consate;

Leastwise I’ve h’ard my mother

säa,

p.

39When she was growed up, a big gal,

And went to sarvice at the Hall,

She han’t but one stuff gownd to wear,

And not the lissest mite of shawl.

But now yeou cäan’t tell whue is whue;

Which is the missus, which the maid,

There ain’t no tellin’; for a gal,

Arter she’s got her wages paid,

Will put ’em all upon her back,

And look as grand as grand can be;

My poor old mother would be stamm’d [39]

Her gal should iver look like she.

And ’taint the lissest bit o’ use

To tell ’em anything at all;

They’ll only lâff, or else begin

All manner o’ hard names to call.

Praps arter all it ’tain’t the truth,

That one time’s wusser than the

t’other;

Praps I’m a-gittin’ old myself,

And fare to talk like my old mother.

p.

40I shäan’t dew nowt by talkin’ so,

I’d better try the good old plan,

Of spakin’ sparing of most folks,

And dewin’ all the good I can.

J. D.

My father used to repeat one stanza of an old song; I wonder whether the remainder still exists in any living memory. That one stanza ran:—

“The roaring boys of Pakefield,

Oh, how they all do thrive!

They had but one poor parson,

And him they buried alive.”

Whether the prosperity of Pakefield was to be dated or derived from the fact of their burying their “one poor parson” is a matter of dangerous speculation, and had better be left in safe obscurity; else other places might be tempted to make trial of the successful plan. But can any one send a copy of the whole song?

From the same authority I give a stanza of another song:—

p. 41“The cackling old hen she began to collogue,

Says she unto the fox, ‘You’re a stinking old rogue;

Your scent it is so strong, I do wish you’d keep away;’

The cackling old hen she began for to say.”

The tune, as I still remember it, is as fine as the words—for fine they certainly are, as an honest expression of opinion, capable of a large application to other than foxes.

I cannot vouch for a like antiquity for the following sea-verses; but they are so good that I venture to append them to their more ancient brethren:—

“And now we haul to the ‘Dog and Bell,’

Where there’s good liquor for to sell;

In come old Archer with a smile,

Saying, ‘Drink, my lads, ’tis worth your while.’Ah! but when our money’s all gone and spent,

And none to be borrowed nor none to be lent;

In comes old Archer with a frown,

Saying, ‘Get up, Jack, let John sit down.’”

Alas, poor Jack! and John Countryman too, when the like result arrives.

J. D.

Fifteen years after my father had penned this note, and more than two years after his death, I received from a p. 42West Indian reader of ‘Maga,’ who had heard it sung by a naval officer (since deceased), the following version of the second sea-song:—

“Cruising in the Channel with the wind North-east,

Our ship she sails nine knots at least;

Our thundering guns we will let fly,

We will let fly over the twinkling sky—

Huzza! we are homeward bound,

Huzza! we are homeward bound.And when we arrive at the Plymouth Dock,

The girls they will around us flock,

Saying, ‘Welcome, Jack, with your three years’ pay,

For we see you are homeward bound to-day’—

Huzza! we are homeward bound,

Huzza! we are homeward bound.And when we come to the --- [42] Bar,

Or any other port in so far,

Old Okey meets us with a smile,

Saying, ‘Drink, my lads, ’tis worth your while’—

Huzza! we are homeward bound,

Huzza! we are homeward bound.Ah! but when our money’s all gone and spent,

And none to be borrowed, nor none to be lent,

Old Okey meets us with a frown,

Saying, ‘Get up, Jack, let John sit down,

For I see you are outward bound,’

For, see, we are outward bound.”

I am werry much obligated to yeou, Mr Editer, for printin’ my lines. I hain’t got no more at spresent, so I’ll send yeou a queery instead. I axed our skule-master, “What’s a queery?” and he säa, “Suffen [43a] queer,” so I think I can sute yeou here.

When I was a good big chap, I lived along with Mr Cooper, of Thräanson. [43b] He was a big man; but, lawk! he was wonnerful päad over with rheumatics, that he was. I lived in the house, and arter I had done up my hosses, and looked arter my stock, I alluz went to bed arly. One night I h’ard [43c] my missus halloin’ at the bottom of the stairs. “John,” sez she, “yeou must git up di-rectly, and go for the doctor; yar master’s took werry bad.” So I hulled [43d] on my clothes, put the saddle on owd Boxer, and warn’t long gittin to the doctor’s, for the owd hoss stromed along stammingly, [43e] he did. When the doctor come, he säa to master, “Yeou ha’ got the lump-ague in yar lines; [43f] yeou must hiv a hot baath.” “What’s that?” sez master. “Oh!” sez the doctor, “yeou must hiv yar biggest tub full o’ hot water, and läa in it ten p. 44minnits.” Sune as he was gone, missus säa, “Dew yeou go and call Sam Driver, and I’ll hit [44a] the copper.” When we cum back, she säa, “Dew yeou tew [44b] take the mashin’-tub up-stairs, and when the water biles yeou cum for it.” So, byne by we filled the tub, and missus säa, “John, dew yeou take yar master’s hid; [44c] and Sam, yeou take his feet, and drop ’im in.” We had a rare job to lift him, I warrant; but we dropt him in, and, O lawk! how he did screech!—yeou might ha’ h’ard ’im a mile off. He splounced out o’ the tub flop upon the floor, and dew all we could we coon’t ’tice him in agin. “Yeou willans,” sez he, “yeou’ve kilt me.” But arter a bit we got him to bed, and he läa kind o’ easy, till the doctor cum next mornin’. Then he towd the doctor how bad he was. The doctor axed me what we’d done. So I towd him, and he säa, “Was the water warm?” “Warm!” sez I, “’twould ommost ha’ scalt a hog.” Oh, how he did lâff! “Why, John bor,” sez he, “yeou must ha’ meant to bile yar master alive.” Howsomdiver, master lost the lump-ague and nivver sed nothin’ about the tub, ’cept when he säa to me sometimes kind o’ joky, “John bor, dew yeou alluz kip [44d] out o’ hot water.”

John Dutfen. [44e]

p. 45This story has a sequel. My father told it once at the dinner-table of one of the canons in Norwich. Every one laughed more or less, all but one, the Rev. “Hervey Du Bois,” a rural dean from the Fens. He alone made no sign. But he was staying in the house; and that night the Canoness was aroused from her sleep by a strange gurgling sound proceeding from his room. She listened and listened, till, convinced that their guest must be in a fit, she at last arose, and listened outside his door. A fit he was in—sure enough—of laughter. He was sitting up in bed, rocking backwards and forwards, and ever and again ejaculating, “Why, John bor, yeou must ha’ meant to bile yar master alive.” And then he went off into another roar.

“That piece of song,

That old and antique song we heard last night.”—‘Twelfth Night,’ II. iv.

This old song was lately taken down from the lips of an old Suffolk (Monk Soham) labourer, who has known it and sung it since he was a boy. The song is of much p. 46repute in the parish where he lives, and may possibly be already in print. At all events it is a genuine “old and antique” song, whose hero may have been one of the sea captains or rovers who continued their privateering in the Spanish Main and elsewhere, and upon all comers, long after all licence from the Crown had ceased. The Rainbow was the name of one of the ships which formed the English fleet when they defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588, and she was re-commissioned, apparently about 1618. The two verses in brackets are from the version of another labourer in my parish, who also furnished some minor variæ lectiones, as “robber” for “rover,” “Blake” for “Wake,” &c.

Rector.

Come, all ye valiant soldiers

That march to follow the drum,

Let us go meet with Captain Ward

When on the sea he come.

He is as big a rover

As ever you did hear,

Yeou hain’t h’ard of such a rover

For many a hundred year.

p.

47There was three ships come sailing

From the Indies to the West,

Well loaded with silks and satins

And welwets of the best.

Who should they meet but Captain Ward,

It being a bad meeting,

He robbèd them of all their wealth,

Bid them go tell the King.

[“Go ye home, go ye home,” says Captain Ward,

“And tell your King from me,

If he reign King of the countrie,

I will be King at Sea.”]

Away went these three gallant ships,

Sailing down of the main,

Telling to the King the news

That Ward at sea would reign.

The King he did prepare a ship,

A ship of gallant fame,

She’s called the gallant Rainbow—

Din’t yeou niver hear her name?

p.

48She was as well purwīded

As e’er a ship could be,

She had three hundred men on board

To bear her company.

Oh then the gallant Rainbow

Sailed where the rover laid;

“Where is the captain of your ship?”

The gallant Rainbow said.

“Here am I,” says Captain Ward,

“My name I never deny;

But if you be the King’s good ship,

You’re welcome to pass by.”

“Yes, I am one of the King’s good ships,

That I am to your great grief,

Whilst here I understand you lay

Playing the rogue and thief.”

“Oh! here am I,” says Captain Ward;

“I value you not one pin;

If you are bright brass without,

I am true steel within.”

p.

49At four o’clock o’ the morning

They did begin to fight,

And so they did continue

Till nine or ten at night.

[Says Captain Ward unto his men,

“My boys, what shall we do?

We have not got one shot on board,

We shall get overthrow.]

“Fight you on, fight you on,” says Captain

Ward,

“Your sport will pleasure be,

And if you fight for a month or more

Your master I will be.”

Oh! then the gallant Rainbow

Went raging down of the main,

Saying, “There lay proud Ward at sea,

And there he must remain.”

“Captain Wake and Captain Drake,

And good Lord Henerie,

If I had one of them alive,

They’d bring proud Ward to me.”

p. 50Appended was this editorial note: “The date of Captain Ward is approximately established by Andrew Barker’s ‘Report of the two famous Pirates, Captain Ward and Danseker’ (Lond. 1609, 4to), and by Richard Daburn’s ‘A Christian turn’d Turke, or the tragical Lives and Deaths of the two famous Pyrates, Ward and Dansiker. As it hath beene publickly acted’ (Lond. 1612, 4to).

And the next week there was the following answer:—

“Having found that in Chappell’s ‘Popular Music of the Olden Time’ there was mention made of a tune called ‘Captain Ward,’ I wrote to Mr Chappell himself. He says about the ballad: ‘For “A famous sea-fight between Captain Ward and the Rainbow” see Roxburghe Collection, v. 3, fol. 56, printed for F. Coles, and another with printer’s name cut off in the same volume, fol. 654; an edition in the Pepys Collection, v. 4, fol. 202, by Clarke Thackeray and Passinger; two in the Bayford, [643, m. 9 / 65] and [643, m. 10 / 78]. These are by W. Onbey, and the second in white letter. Further, two Aldermary Church Yard editions in Rox. v. 3, folios 652 and 861. The ballad has an Elizabethan cut about it, beginning, “Strike up, you lusty Gallants.” If I remember rightly, Ward was a famous pirate of Elizabeth’s reign, about the same time as Dansekar the Dutchman.’

“I went down myself to Magdalene, and saw the copy in the Pepysian Library there. It is entirely different from that in the ‘Suffolk N. and Q.,’ though at the same time there are p. 51slight resemblances in expression. As ballads they are quite distinct. I suppose the other copies to which Mr Chappell refers are like the Pepysian, which begins as he says, ‘Strike up, ye lusty Gallants.’

“W. Aldis Wright.

“Cambridge.”

Not many years since, not far from Ipswich, some practical agriculturists met—as, for all I know, they may meet now—at a Farmers’ Club to discuss such questions as bear practically upon their business and interests. One evening the subject for discussion was, “How to cure hot yards,” i.e., yards where the manure has become so heated as to be hurtful to the cattle’s feet. Many remedies were suggested, some no doubt well worth trying, others dealing too much maybe in small-talk of acids and alkalis. None of the party was satisfied that a cure had been found which stood the test of general experience. Then they asked an elderly farmer, who had preserved a profound silence through all the discussion, what he would recommend. His answer was very true and to the point. “Gentlemen,” he said, “yeou shu’nt have let it got so.”

Hippicus.

A Suffolk Clergyman’s Reminiscence. [52a]

Our young parson said to me t’other däa, “John,” sez he, “din’t yeou nivver hev a darter?” “Sar,” sez I, “I had one once, but she ha’ been dead close on thatty years.” And then I towd him about my poor mor. [52b]

“I lost my fust wife thatty-three years ago. She left me with six bors and Susan. She was the owdest of them all, tarned sixteen when her mother died. She was a fine jolly gal, with lots of sperit. I coon’t be alluz at home, and tho’ I’d nivver a wadd [52c] to säa aginst Susan, yet I thowt I wanted some one to look arter her and the bors. Gals want a mother more than bors. So arter a year I married my second wife, and a rale good wife she ha’ bin to me. But Susan coon’t git on with her. She’d dew [52d] what she was towd, but ’twarn’t done pleasant, and p. 53when she spŏok she spŏok so short. My wife was werry patient with her; but dew all she could, she nivver could git on with Susan.

“I’d a married sister in London, whue cum down to see us at Whissuntide. She see how things fared, and she säa to me, ‘John,’ sez she, ‘dew yeou let Susan go back with me, and I’ll git her a good place and see arter her.’ So ’twas sattled. Susan was all for goin’, and when she went she kiss’t me and all the bors, but she nivver sed nawthin’ to my wife, ’cept just ‘Good-bye.’ She fared to git a nice quite [53] place; but then my sister left London, and Susan’s missus died, and so she had to git a place where she could. So she got a place where they took in lodgers, and Susan and her missus did all the cookin’ and waitin’ between ’em. Susan sed arterwards that ’twarn’t what she had to dew, but the runnin’ up-stairs; that’s what killt her. There was one owd gentleman, who lived at the top of the house. He’d ring his bell, and if she din’t go di-reckly, he’d ring and ring agen, fit to bring the house down. One daa he rung three times, but Susan was set fast, and coon’t go; and when she did, he spŏok so sharp, that it whŏlly upset her, and she dropt down o’ the floor all in a faint. He hollered out at the top o’ the stairs; and sum o’ the fŏoks cum runnin’ up to see what was the p. 54matter. Arter a bit she cum round, and they got her to bed; but she was so bad that they had to send for the doctor. The owd gentleman was so wexed, he sed he’d päa for the doctor as long as he could; but when the doctor sed she was breedin’ a faver, nawthing would satisfy her missus but to send her to the horspital, while she could go.

“So she went into the horspital, and läa five weeks and din’t know nobody. Last she begun to mend, and she sed that the fŏoks there were werry kind. She had a bed to herself in a big room with nigh twenty others. Ivry däa the doctor cum round, and spŏok to ’em all in tarn. He was an owdish gentleman, and sum young uns cum round with him. One mornin’ he säa to Susan, ‘Well, my dear,’ sez he, ‘how do yeou feel to-day?’ She säa, ‘Kind o’ middlin’, sir.’ She towd me that one o’ the young gentlemen sort o’ laffed when he h’ard her, and stopped behind and saa to her, ‘Do yeou cum out o’ Suffolk?’ She säa, ‘Yes; what, do yeou know me?’ She was so pleased! He axed her where she cum from, and when she towd him, he säa, ‘I know the clargyman of the parish.’ He’d a rose in his button-hole, and he took it out and gov it her, and he säa, ‘Yeou’ll like to hev it, for that cum up from Suffolk this mornin’.’ Poor mor, she was so pleased! Well, arter a bit she got better, and the doctor säa, ‘My p. 55dear, yeou must go and git nussed at home. That’ll dew more for yeou than all the doctors’ stuff here.’

“She han’t no money left to päa for her jarney. But the young gentleman made a gatherin’ for her, and when the nuss went with her to the station, he holp her into the cab, and gov her the money. Whue he was she din’t know, and I don’t now, but I alluz säa, ‘God bless him for it.’

“One mornin’ the owd parson—he was yar father—sent for me, and he säa, ‘John,’ sez he, ‘I ha’ had a letter to say that Susan ha’ been in the horspital, but she is better now, and is cummin’ home to-morrow. So yeou must meet her at Halser, [55] and yeou may hiv my cart.’ Susan coon’t write, so we’d nivver h’ard, sin’ her aunt went away. Yeou may s’pose how I felt! Well, I went and met her. O lawk, a lawk! how bad she did look! I got her home about five, and my wife had got a good fire, and ivrything nice for her, but, poor mor! she was whŏlly beat. She coon’t eat nawthin’. Arter a bit, she tuk off her bonnet, and then I see she han’t no hair, ’cept a werry little. That whŏlly beat me, she used to hev such nice hair. Well, we got her to bed, and for a whole week she coon’t howd up at all. Then she fare to git better, and cum down-stairs, and sot by the fire, and begun to pick a little. p. 56And so she went on, when the summer cum, sometimes better and sometimes wuss. But she spook werry little, and din’t seem to git on no better with my wife. Yar father used to cum and see her and read to her. He was werry fond of her, for he had knowed her ivver sin’ she was born. But she got waker and waker, and at last she coon’t howd up no longer, but took whŏlly to her bed. How my wife did wait upon her! She’d try and ’tice her to ate suffen, [56a] when yar father sent her a bit o’ pudden. I once säa to him, ‘What do yeou think o’ the poor mor?’ ‘John,’ sez he, ‘she’s werry bad.’ ‘But,’ sez I, ‘dew she know it?’ ‘Yes,’ sez he, ‘she dew; but she een’t one to säa much.’ But I alluz noticed, she seem werry glad to see yar father.

“One day I’d cum home arly; I’d made one jarney. [56b] So I went up to see Susan. There I see my wife läad outside the bed close to Susan; Susan was kind o’ strokin’ her face, and I h’ard her säa, ‘Kiss me, mother dear; yeou’re a good mother to me.’ They din’t see me, so I crep’ down-stairs, but it made me werry comforble.

“Susan’s bed läa close to the wall, so that she could alluz make us know at night if she wanted anything by p. 57jest knockin’. One night we h’ard her sing a hymn. She used to sing at charch when she was a little gal, but I nivver h’ard her sing so sweetsome as she did then. Arter she’d finished, she knockt sharp, and we went di-reckly. There she läa—I can see her now—as white as the sheets she läa in. ‘Father,’ sez she, ‘am I dyin’?’ I coon’t spake, but my wife sed, ‘Yeou’re a-dyin’, dear.’ ‘Well, then,’ sez she, ‘’tis bewtiful.’ And she lookt hard at me, hard at both of us; and then lookt up smilin’, as if she see Some One.

“She was the only darter I ivver had.”

John Dutfen.

Is it extravagant to believe that this simple story, told by a country parson, is worth whole pages of learned arguments against Disestablishment? [57] Anyhow, to support such arguments, I will here cite an ancient ditty of my father’s. He had got it from “a true East Anglian, of Norfolk lineage and breeding,” but the exegesis is wholly my father’s own.

Robin Cook’s wife [58a] she had an old

mare, [58b]

Humpf, humpf, hididdle, humpf!

And if you’d but seen her, Lord! how you’d have

stared, [58c]

Singing, “Folderol diddledol, hidum

humpf.”

This old mare she had a sore back, [58d]

Humpf, &c.

And on her sore back there was hullt an old sack, [58e]

Singing, &c.

p.

59Give the old mare some corn in the sieve, [59a]

Humpf, &c.

And ’tis hoping God’s husband (sic) the old

mare may live,

Singing, &c.

This old mare she chanced for to die, [59b]

Humpf, &c.

And dead as a nit in the roadway she lie, [59c]

Singing, &c.

All the dogs in the town spŏok for a bone, [59d]

Humpf, &c.

All but the Parson’s dog, [59e] he went wi’

none,

Singing, “Folderol diddledol, hidum

humpf.”

A Suffolk Labourer’s Story.

The Owd Master at the Hall had two children—Mr James and Miss Mary. Mr James was ivver so much owder than Miss Mary. She come kind o’ unexpected like, and she warn’t but a little thing when she lost her mother. When she got owd enough Owd Master sent her to a young ladies’ skule. She was there a soot o’ years, and when she come to stäa at home, she was such a pretty young lady, that she was. She was werry fond of cumpany, but there warn’t the lissest bit wrong about her. There was a young gentleman, from the shēres, who lived at a farm in the next parish, where he was come to larn farmin’. He was werry fond of her, and though his own folks din’t like it, it was all sattled that he was soon to marry her. Then he hear’d suffen about her, which warn’t a bit true, and he went awäa, and was persuaded to marry somebody else. Miss Mary took on bad about it, but that warn’t the wust of it. She had a baby before long, and he was the father on’t.

O lawk, a lawk! how the Owd Master did break out p. 61when he hear’d of it! My mother lived close by, and nussed poor Miss Mary, so I’ve h’ard all about it. He woun’t let the child stop in the house, but sent it awäa to a house three miles off, where the woman had lost her child. But when Miss Mary got about, the woman used to bring the baby—he was “Master Charley”—to my mother’s. One däa, when she went down, my mother towd her that he warn’t well; so off she went to see him. When she got home she was late, and the owd man was kep’ waitin’ for his dinner. As soon as he see her, he roared out, “What! hev yeou bin to see yar bastard?” “O father,” says she, “yeou shoun’t säa so.” “Shoun’t säa so,” said he, “shoun’t I? I can säa wuss than that.” And then he called her a bad name. She got up, nivver said a wadd, but walked straight out of the front door. They din’t take much notiz at fust, but when she din’t come back, they got scared, and looked for her all about; and at last they found her in the mŏot, at the bottom of the orchard.

O lawk, a lawk!

The Owd Master nivver could howd up arter that. ’Fore that, if he was put out, yeou could hear ’im all over the farm, a-cussin’ and swearin’. He werry seldom spŏok to anybody now, but he was alluz about arly and late; nŏthin’ seemed to tire him. ’Fore that he nivver went to p. 62chărch; now he went reg’ler. But he wud säa sumtimes, comin’ out, “Parson’s a fule.” But if anybody was ill, he bod ’em go up to the Hall and ax for suffen. [62] There was young Farmer Whoo’s wife was werry bad, and the doctor säa that what she wanted was London poort. So he sent my father to the marchant at Ipswich, to bring back four dozen. Arter dark he was to lave it at the house, but not to knock. They nivver knew where ta come from till arter he died. But he fare to get waker, and to stupe more ivry year.

Yeou ax me about “Master Charley.” Well, he growed up such a pretty bor. He lived along with my mother for the most part, and Mr James was so fond of him. He’d come down, and pläa and talk to him the hour togither, and Master Charley would foller ’im about like a little dawg.

One däa they was togither, and Owd Master met ’em. “James,” said he, “what bor is that alluz follerin’ yeou about?” He said, “It’s Mary’s child.” The owd man tărned round as if he’d bin shot, and went home all himpin’ along. Folks heared him säa, “Mary’s child! Lord! Lord!” When he got in, he sot down, and nivver spŏok a wădd, ’cept now and then, “Mary’s child! Lord! Lord!” He coun’t ate no dinner; but he towd ’em to p. 63go for my mother; and when she come, he säa to her, “Missus, yeou must git me to bed.” And there he läa all night, nivver slāpin’ a bit, but goin’ on säain, “Mary’s child! Lord! Lord!” quite solemn like. Sumtimes he’d säa, “I’ve bin a bad un in my time, I hev.”

Next mornin’ Mr James sent for the doctor. But when he come, Owd Master said, “Yeou can do nothin’ for me; I oon’t take none o’ yar stuff.” No more he would. Then Mr James säa, “Would yeou like to see the parson?” He din’t säa nŏthin’ for some time, then he said, “Yeou may send for him.” When the parson come—and he was a nice quite [63] owd gentleman, we were werry fond of him—he went up and stäa’d some time; but he nivver said nŏthin’ when he come down. Howsomdiver, Owd Master läa more quiter arter that, and when they axed him to take his med’cin he took it. Then he slep’ for some hours, and when he woke up he called out quite clear, “James.” And when Mr James come, he säa to him, “James,” sez he, “I ha’ left ivrything to yeou; do yeou see that Mary hev her share.” You notiz, he din’t säa, “Mary’s child,” but “Mary hev her share.” Arter a little while he said, “James, I should like to see the little chap.” He warn’t far off, and my mother made him tidy, and brushed his hair and parted it. Then she p. 64took him up, and put him close to the bed. Owd Master bod ’em put the curtain back, and he läa and looked at Master Charley. And then he said, quite slow and tendersome, “Yeou’re a’most as pritty as your mother was, my dear.”

Them was the last words he ivver spŏok.

Mr James nivver married, and when he died he left ivrything to Master Charley.

My earliest recollections of FitzGerald go back to thirty-six years. He and my father were old friends and neighbours—in East Suffolk, where neighbours are few, and fourteen miles counts for nothing. They never were great correspondents, for what they had to say to one another they said mostly by word of mouth. So there were notes, but no letters; and the notes have nearly all perished. In the summer of 1859 we were staying at Aldeburgh, a favourite place with my father, as the home of his forefathers. They were sea-folk; and Robinson Groome, my great-grandfather, was owner of the Unity lugger, on which the poet Crabbe went up to London. When his son, my grandfather, was about to take orders, he expressed a timid hope that the bishop p. 68would deem him a proper candidate. “And who the devil in hell,” cried Robinson Groome, “should he ordain if he doesn’t ordain you, my dear?” [68] This I have heard my father tell FitzGerald, as also of his “Aunt Peggy and Aunt D.” (i.e., Deborah), who, if ever Crabbe was mentioned in their hearing, always smoothed their black mittens and remarked—“We never thought much of Mr Crabbe.”

Our house was Clare Cottage, where FitzGerald himself lodged long afterwards. “Two little rooms, enough for me; a poor civil woman pleased to have me in them.” It fronts the sea, and is (or was) a small two-storeyed house, with a patch of grass before it, a summer-house, and a big white figurehead, belike of the shipwrecked Clare. So over the garden-gate FitzGerald leant one June morning, and asked me, a boy of eight, was my father at home. I remember him dimly then as a tall sea-browned man, who took us boys out for several sails, on the first of which I and a brother were both of us woefully sea-sick. Afterwards I remember picnics down the Deben river, and visits to him at Woodbridge, first in his p. 69lodgings on the Market Hill over Berry the gunsmith’s, and then at his own house, Little Grange. The last was in May 1883. My father and I had been spending a few days with Captain Brooke of Ufford, the possessor of one of the finest private libraries in England. [69] From Ufford we drove on to Woodbridge, and passed some pleasant hours with FitzGerald. We walked down to the riverside, and sat on a bench at the foot of the lime-tree walk. There was a small boy, I remember, wading among the ooze; and FitzGerald, calling him to him, said—“Little boy, did you never hear tell of the fate of the Master of Ravenswood?” And then he told him the story. At dinner there was much talk, as always, of many things, old and new, but chiefly old; and at nine we started on our homeward drive. Within a month I heard that FitzGerald was dead.

From my own recollections, then, of FitzGerald himself, but still more of my father’s frequent talk of him, from some notes and fragments that have escaped hebdomadal burnings, from a visit that I paid to Woodbridge in the summer of 1889, and from reminiscences and unpublished p. 70letters furnished by friends of FitzGerald, I purpose to weave a patchwork article, which shall in some ways supplement Mr Aldis Wright’s edition of his Letters. [70] Those letters surely will take a high place in literature, on their own merits, quite apart from the interest that attaches to the translator of Omar Khayyám, to the friend of Thackeray, Tennyson, and Carlyle. Here and there I may cite them; but whoso will know FitzGerald must go to the fountain-head. And yet that the letters by themselves may convey a false impression of the man is evident from several articles on them—the best and worst Mr Gosse’s in the ‘Fortnightly’ (July 1889). Mr Gosse sums him up in the statement that “his time, when the roses were not being pruned, and when he was not making discreet journeys in uneventful directions, was divided between music, which greatly occupied his younger thought, and literature, which slowly, but more and more exclusively, engaged his attention.” There is truth in the statement; still this pruner of roses, who of rose-pruning p. 71knew absolutely nothing, was one who best loved the sea when the sea was rough, who always put into port of a Sunday that his men might “get their hot dinner.” He was one who would give his friend of the best—oysters, maybe, and audit ale, which “dear old Thompson” used to send him from Trinity—and himself the while would pace up and down the room, munching apple or turnip, and drinking long draughts of milk. He was a man of marvellous simplicity of life and matchless charity: hereon I will quote a letter of Professor Cowell’s, who did, if any one, know FitzGerald well:—

“He was no Sybarite. There was a vein of strong scorn of all self-indulgence in him, which was very different. He was, of course, very much of a recluse, with a vein of misanthropy towards men in the abstract, joined to a tender-hearted sympathy for the actual men and women around him. He was the very reverse of Carlyle’s description of the sentimental philanthropist, who loves man in the abstract, but is intolerant of ‘Jack and Tom, who have wills of their own.’”

FitzGerald’s charities are probably forgotten, unless by the recipients; and how many of them must be dead, old soldiers as they mostly were, and suchlike! But this I have heard, that one man borrowed £200 of him. Three times he regularly paid the interest, and the third time FitzGerald put his note of hand in the fire, just saying he thought that would do. His simplicity dated from very p. 72early times. For when he was at Trinity, his mother called on him in her coach-and-four, and sent a gyp to ask him to step down to the college-gate, but he could not come—his only pair of shoes was at the cobbler’s. And down to the last he was always perfectly careless as to dress. I can see him now, walking down into Woodbridge, with an old Inverness cape, double-breasted, flowered satin waistcoat, slippers on feet, and a handkerchief, very likely, tied over his hat. Yet one always recognised in him the Hidalgo. Never was there a more perfect gentleman. His courtesy came out even in his rebukes. A lady one day was sitting in a Woodbridge shop, gossiping to a friend about the eccentricities of the Squire of Boulge, when a gentleman, who was sitting with his back to them, turned round, and, gravely bowing, gravely said, “Madam, he is my brother.” They were eccentric, certainly, the FitzGeralds. FitzGerald himself remarked of the family: “We are all mad, but with this difference—I know that I am.” And of that same brother he once wrote to my father:—

Lowestoft: Dec. 2/66.