The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bucholz and the Detectives, by Allan Pinkerton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Bucholz and the Detectives Author: Allan Pinkerton Release Date: January 31, 2007 [EBook #20497] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BUCHOLZ AND THE DETECTIVES *** Produced by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE CRIME.

PAGE

The Arrival in South Norwalk.—The Purchase of the Farm.—A Miser's Peculiarities, and the Villagers' Curiosity17

William Bucholz.—Life at Roton Hill.—A Visit to New York City30

An Alarm at the Farm House.—The Dreadful Announcement of William Bucholz.—The Finding of the Murdered Man39

The Excitement in the Village.—The Coroner's Investigation.—The Secret Ambuscade47

The Hearing Before the Coroner.—Romantic Rumors and Vague Suspicions.—An Unexpected Telegram.—Bucholz Suspected56

The Miser's Wealth.—Over Fifty Thousand Dollars Stolen from the Murdered Man.—A Strange Financial Transaction.—A Verdict, and the Arrest of Bucholz67

Bucholz in Prison.—Extravagant Habits, and Suspicious Expenditures.—The German Consul Interests Himself.—Bucholz Committed78

My Agency is Employed.—The Work of Detection Begun87

THE HISTORY.

Dortmund.—Railroad Enterprise and Prospective Fortune.—Henry Schulte's Love.—An Insult and Its Resentment.—An Oath of Revenge93

A Curse, and Plans of Vengeance109

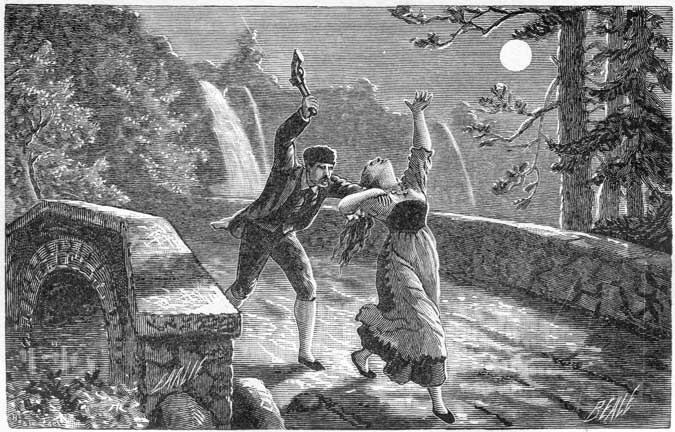

A Moonlight Walk.—An Unexpected Meeting.—The Murder of Emerence Bauer.—The Oath Fulfilled115

The Search for the Missing Girl.—The Lover's Judgment.—Henry Schulte's Grief.—The Genial Farmer Becomes the Grasping Miser122

Henry Schulte becomes the Owner of "Alten-Hagen."—Surprising Increase in Wealth.—An Imagined Attack Upon His Life.—The Miser Determines to Sail for America131

The Arrival in New York.—Frank Bruner Determines to Leave the Service of His Master.—The Meeting of Frank Bruner and William Bucholz148

A History of William Bucholz.—An Abused Aunt who Disappoints His Hopes.—A Change of Fortune.—The Soldier becomes a Farmer.—The Voyage to New York157

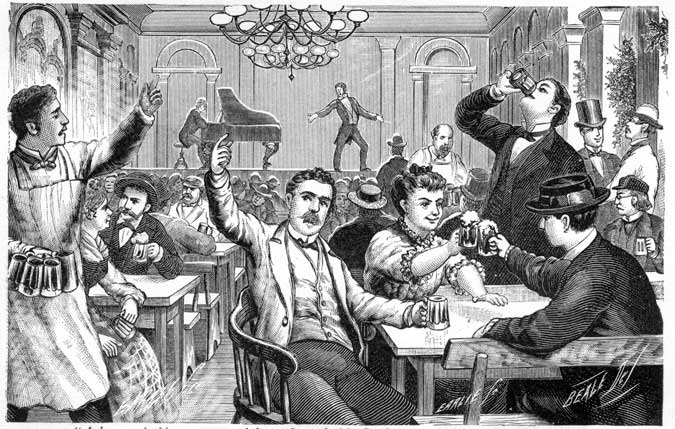

Frank Leaves the Service of His Master.—A Bowery Concert Saloon.—The Departure of Henry Schulte.—William Bucholz Enters the Employ of the Old Gentleman166

THE DETECTION.

The Detective.—His Experience, and His Practice.—A Plan of Detection Perfected.—The Work is Begun.177

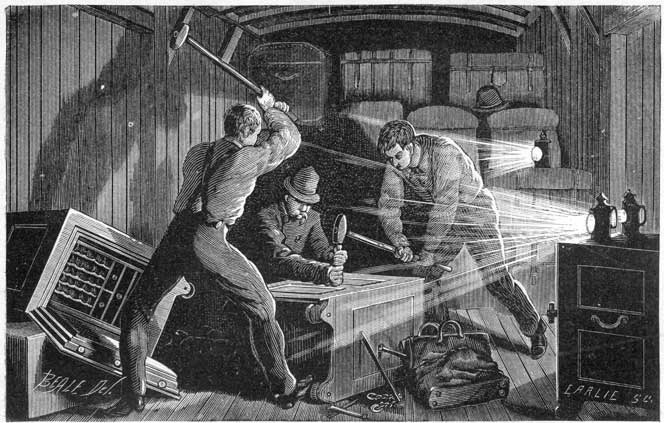

A Detective Reminiscence.—An Operation in Bridgeport in 1866.—The Adams Express Robbery.—A Half Million of Dollars Stolen.—Capture of the Thieves.—One of the Principals Turns State's Evidence.—Conviction and Punishment185

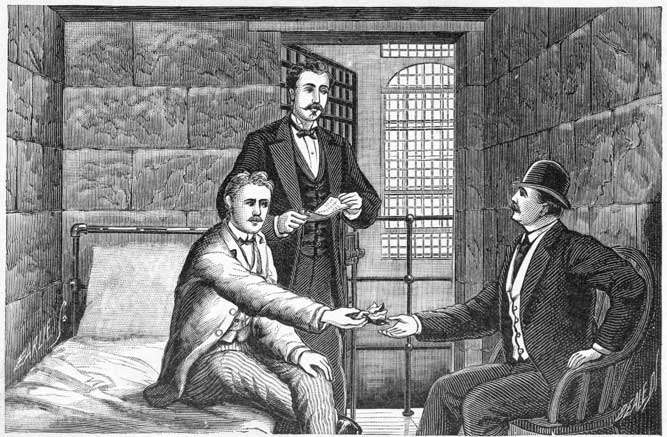

The Jail at Bridgeport.—An Important Arrest.—Bucholz Finds a Friend.—A Suspicious Character who Watches and Listens.—Bucholz Relates his Story205

Bucholz Passes a Sleepless Night.—An Important Discovery.—The Finding of the Watch of the Murdered Man.—Edward Sommers Consoles the Distressed Prisoner218

A Romantic Theory Dissipated.—The Fair Clara Becomes communicative.—An Interview with the Bar Keeper of the "Crescent Hotel"226

Sommers Suggests a Doubt of Bucholz's Innocence.—He Employs Bucholz's Counsel to Effect his Release.—A Visit from the State's Attorney.—A Difficulty, and an Estrangement233

The Reconciliation.—Bucholz makes an Important Revelation.—Sommers Obtains his Liberty and Leaves the Jail244

Sommers Returns to Bridgeport.—An Interview with Mr. Bollman.—Sommers Allays the Suspicions of Bucholz's Attorney, and Engages Him as his Own Counsel252

Sommers' Visit to South Norwalk.—He Makes the Acquaintance of Sadie Waring.—A Successful Ruse.—Bucholz Confides to his Friend the Hiding Place of the Murdered Man's Money260

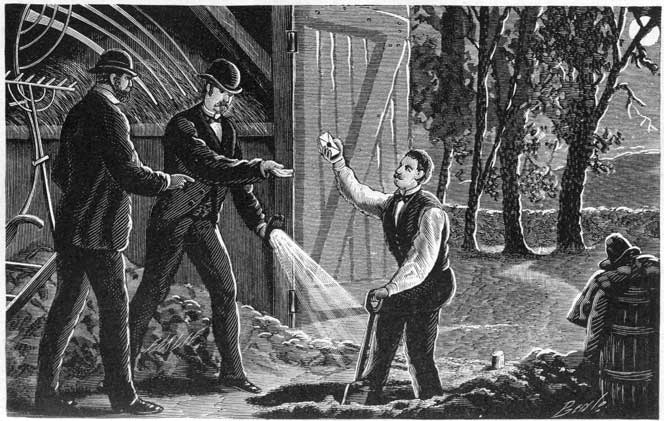

Edward Sommers as "The Detective."—A Visit to the Barn, and Part of the Money Recovered.—The Detective makes Advances to the Counsel for the Prisoner.—A Further Confidence of an Important Nature270

A Midnight Visit to the Barn.—The Detective Wields a Shovel to Some Advantage.—Fifty Thousand Dollars Found in the Earth.—A Good Night's Work284

The Detective Manufactures Evidence for the Defense.—An Anonymous Letter.—An Important Interview.—The Detective Triumphs Over the Attorney295

Bucholz Grows Skeptical and Doubtful.—A fruitless Search.—The Murderer Involuntarily Reveals Himself309

THE JUDGMENT.

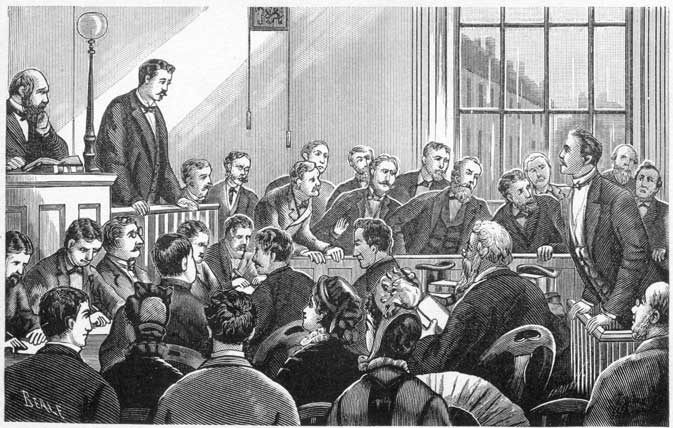

The Trial.—An Unexpected Witness.—A Convincing Story.—An Able but Fruitless Defense.—A Verdict of Guilty.—The Triumph of Justice319

Another Chance for Life.—The Third Trial Granted.—A Final Verdict, and a Just Punishment338

The following pages narrate a story of detective experience, which, in many respects, is alike peculiar and interesting, and one which evinces in a marked degree the correctness of one of the cardinal principles of my detective system, viz.: "That crime can and must be detected by the pure and honest heart obtaining a controlling power over that of the criminal."

The history of the old man who, although in the possession of unlimited wealth, leaves the shores of his native land to escape the imagined dangers of assassination, and arrives in America, only to meet his death—violent and mysterious—at the hands of a trusted servant, is in all essential points a recital of actual events. While it is true that in describing the early career of this man, the mind may have roamed through the field of romance, yet the important events which are related of him are based entirely upon information authentically derived.

The strange operation of circumstances which brought these two men together, although they had journeyed across the seas—each with no knowledge of the existence of the other—to meet and to participate in the sad drama of crime, is one of those realistic evidences of the inscrutable operations of fate, which are of frequent occurrence in daily life.

The system of detection which was adopted in this case, and which was pursued to a successful termination, is not a new one in the annals of criminal detection. From the inception of my career as a detective, I have believed that crime is an element as foreign to the human mind as a poisonous substance is to the body, and that by the commission of a crime, the man or the woman so offending, weakens, in a material degree, the mental and moral strength of their characters and dispositions. Upon this weakness the intelligent detective must bring to bear the force and influence of a superior, moral and intellectual power, and then successful detection is assured.

The criminal, yielding to a natural impulse of human nature, must seek for sympathy. His crime haunts him continually, and the burden of concealment becomes at last too heavy to bear alone. It must find a voice; and whether it be to the empty air in fitful dreamings, or into the ears of a sympathetic friend—he must relieve himself of the terrible secret which is bearing him down. Then it is that the watchful detective may seize the criminal in his moment of weakness and by his sympathy, and from the confidence he has engendered, he will force from him the story of his crime.

That such a course was necessary to be pursued in this case will be apparent to all. The suspected man had been precipitately arrested, and no opportunity was afforded to watch his movements or to become associated with him while he was at liberty. He was an inmate of a prison when I assumed the task of his detection, and the course pursued was the only one which afforded the slightest promise of success; hence its adoption.

Severe moralists may question whether this course is a legitimate or defensible one; but as long as crime exists, the necessity for detection is apparent. That a murderous criminal should go unwhipt of justice because the process of his detection is distasteful to the high moral sensibilities of those to whom crime is, perhaps, a stranger, is an argument at once puerile and absurd. The office of the detective is to serve the ends of justice; to purge society of the degrading influences of crime; and to protect the lives, the property and the honor of the community at large; and in this righteous work the end will unquestionably justify the means adopted to secure the desired result.

That the means used in this case were justifiable the result has proven. By no other course could the murderer of Henry Schulte have been successfully punished or the money which he had stolen recovered.

The detective, a gentleman of education and refinement, in the interests of justice assumes the garb of the criminal; endures the privations and restraints of imprisonment, and for weeks and months associates with those who have defied the law, and have stained their hands with blood; but in the end he emerges from the trying and fiery ordeal through which he has passed triumphant. The law is vindicated, and the criminal is punished.

Despite the warnings of his indefatigable counsel, and the fears which they had implanted in his mind, the detective had gained a control over the mind of the guilty man, which impelled him to confess his crime and reveal the hiding place of the money which had led to its commission.

That conviction has followed this man should be a subject of congratulation to all law-abiding men and women; and if the fate of this unhappy man, now condemned to long weary years of imprisonment, shall result in deterring others from the commission of crime, surely the operations of the detective have been more powerfully beneficial to society than all the eloquence and nicely-balanced theories—incapable of practical application—of the theoretical moralist, who doubts the efficiency or the propriety of the manner in which this great result has been accomplished.

ALLAN PINKERTON.

THE CRIME.

The Arrival in South Norwalk.—The Purchase of the Farm.—A Miser's Peculiarities, and the Villagers' Curiosity.

About a mile and a half from the city of South Norwalk, in the State of Connecticut, rises an eminence known as Roton Hill. The situation is beautiful and romantic in the extreme. Far away in the distance, glistening in the bright sunshine of an August morning, roll the green waters of Long Island Sound, bearing upon its broad bosom the numerous vessels that ply between the City of New York and the various towns and cities along the coast. The massive and luxurious steamers and the little white-winged yachts, the tall "three-masters" and the trim and gracefully-sailing schooners, are in full view. At the base of the hill runs the New York and New Haven Railroad, with its iron horse and long trains of cars, carrying their wealth of freights and armies of passengers to all points in the East, while to the left lies the town of South Norwalk—the spires of its churches rising up into the blue sky, like monuments pointing heaven-ward—and whose beautiful and capacious school-houses are filled with the bright eyes and rosy faces of the youths who receive from competent teachers the lessons that will prove so valuable in the time to come.

Various manufactories add to the wealth of the inhabitants, whose luxurious homes and bright gardens are undoubted indications of prosperity and domestic comfort. The placid river runs through the town, which, with the heavy barges lying at the wharves, the draw-bridges which span its shores, and the smaller crafts, which afford amusement to the youthful fraternity, contribute to the general picturesqueness of the scene.

The citizens, descended from good old revolutionary sires, possess the sturdy ambitions, the indomitable will and the undoubted honor of their ancestors, and, as is the case with all progressive American towns, South Norwalk boasts of its daily journal, which furnishes the latest intelligence of current events, proffers its opinions upon the important questions of the day, and, like the Sentinel of old, stands immovable and unimpeachable between the people and any attempted encroachment upon their rights.

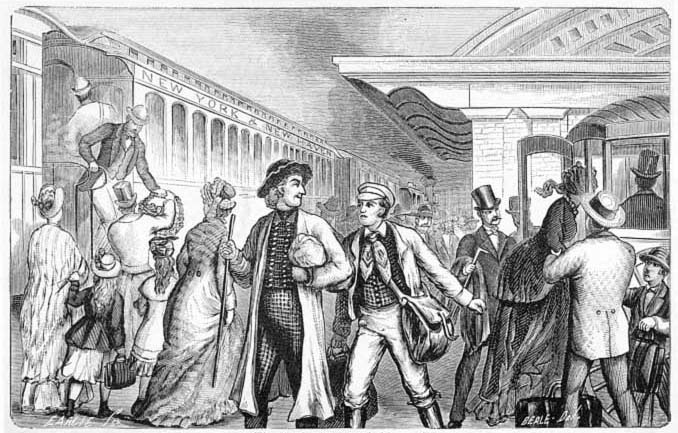

On a beautiful, sunny day in August, 1878, there descended from the train that came puffing up to the commodious station at South Norwalk, an old man, apparently a German, accompanied by a much younger one, evidently of the same nationality. The old gentleman was not prepossessing in appearance, and seemed to be avoided by his well-dressed fellow-passengers. He was a tall, smooth-faced man about sixty years of age, but his broad shoulders and erect carriage gave evidence of an amount of physical power and strength scarcely in accord with his years. Nor was his appearance calculated to impress the observer with favor. He wore a wretched-looking coat, and upon his head a dingy, faded hat of foreign manufacture. His shoes showed frequent patches, and looked very much as though their owner had performed the duties of an amateur cobbler.

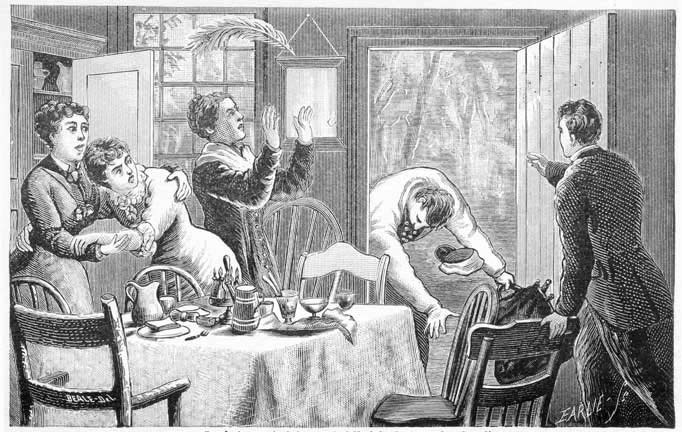

The Arrival at South Norwalk.

It was not a matter of wonder, therefore, that the round-faced Squire shrugged his burly shoulders as the new-comer entered his office, or that he was about to bestow upon the forlorn-looking old man some trifling token of charity.

The old gentleman, however, was not an applicant for alms. He did not deliver any stereotyped plea for assistance, nor did he recite a tale of sorrow and suffering calculated to melt the obdurate heart of the average listener to sympathy, and so with a wave of his hand he declined the proffered coin, and stated the nature of his business.

The Squire soon discovered his error, for instead of asking for charity, his visitor desired to make a purchase, and in place of being a victim of necessity, he intended to become a land-owner in that vicinity.

The young man who accompanied him, and who was dressed in clothing of good quality and style, was discovered to be his servant, and the old gentlemen, in a few words, completed a bargain in which thousands of dollars were involved.

The blue eyes of the worthy Squire opened in amazement as the supposed beggar, drawing forth a well-filled but much-worn leather wallet, and taking from one of its dingy compartments the amount of the purchase-money agreed upon, afforded the astonished magistrate a glimpse of additional wealth of which the amount paid seemed but a small fraction.

The land in question which thus so suddenly and strangely changed hands was a farm of nearly thirty acres, situate upon Roton Hill, and which had been offered for sale for some time previous, without attracting the attention of an available purchaser. When, therefore, the new-comer completed his arrangements in comparatively such few words, and by the payment of the purchase-money in full, he so completely surprised the people to whom the facts were speedily related by the voluble Squire, that the miserably apparelled owner of the "Hill," became at once an object of curiosity and interest.

A few days after this event, the old gentleman, whose name was ascertained to be John Henry Schulte, formally entered into possession of his land, and with his servants took up his abode at Roton Hill.

The dwelling-house upon the estate was an unpretentious frame building, with gable roof, whose white walls, with their proverbial green painted window shutters overlooking the road, showed too plainly the absence of that care and attention which is necessary for comfort and essential to preservation. It was occupied at this time by a family who had been tenants under the previous owner, and arrangements were soon satisfactorily made by Henry Schulte by which they were to continue their residence in the white farm-house upon the "Hill."

This family consisted of a middle-aged man, whose name was Joseph Waring, his wife and children—a son and two blooming daughters, and as the family of Henry Schulte consisted only of himself and his servant, the domestic arrangements were soon completed, and he became domiciled at once upon the estate which he had purchased.

The young man who occupied the position as servant, or valet, to the eccentric old gentleman, was a tall, broad-shouldered, fine-looking young fellow, whose clear-cut features and prominent cheek-bones at once pronounced him to be a German. His eyes were large, light blue in color, and seemed capable of flashing with anger or melting with affection; his complexion was clear and bright, but his mouth was large and with an expression of sternness which detracted from the pleasing expression of his face; while his teeth, which were somewhat decayed, added to the unpleasing effect thus produced. He was, however, rather a good-looking fellow, with the erect carriage and jaunty air of the soldier, and it was a matter of surprise to many, that a young man of his appearance should occupy so subservient a position, and under such a singular master.

Such was William Bucholz, the servant of Henry Schulte.

Between master and man there appeared to exist a peculiar relation, partaking, at times, more of the nature of a protector than the servant, and in their frequent walks William Bucholz would invariably be found striding on in advance, while his aged, but seemingly robust, employer would follow silently and thoughtfully at a distance of a few yards. At home, however, his position was more clearly defined, and William became the humble valet and the nimble waiter.

The reserved disposition and retired habits of the master were regarded as very eccentric by his neighbors, and furnished frequent food for comment and speculation among the gossips which usually abound in country villages—and not in this case without cause. His manner of living was miserly and penurious in the extreme, and all ideas of comfort seemed to be utterly disregarded.

The furniture of the room which he occupied was of the commonest description, consisting of an iron bedstead, old and broken, which, with its hard bed, scanty covering and inverted camp-stool for a pillow, was painfully suggestive of discomfort and unrest. A large chest, which was used as a receptacle for food; a small deal table, and two or three unpainted chairs, completed the inventory of the contents of the chamber in which the greater portion of his time was passed when at home.

The adjoining chamber, which was occupied by Bucholz, was scarcely more luxurious, except that some articles for toilet use were added to the scanty and uninviting stock.

The supplies for his table were provided by himself, and prepared for his consumption by Mrs. Waring. In this regard, also, the utmost parsimony was evinced, and the daily fare consisted of the commonest articles of diet that he was able to purchase. Salt meats and fish, brown bread and cheese, seemed to be the staple articles of food. At the expiration of every week, accompanied by William, he would journey to South Norwalk, to purchase the necessary stores for the following seven days, and he soon became well-known to the shopkeepers for the niggardly manner of his dealings. Upon his return his purchases would be carefully locked up in the strong box which he kept in his room, and would be doled out regularly to the servant for cooking in the apartments below, with a stinting exactness painfully amusing to witness.

The only luxury which he allowed himself was a certain quantity of Rhenish wine, of poor quality and unpleasant flavor, which was partaken of by himself alone, and apparently very much enjoyed. At his meals Bucholz was required to perform the duties of waiter; arranging the cloth, carrying the food and dancing in constant attendance—after which he would be permitted to partake of his own repast, either with the family, who frequently invited him, and thus saved expense, or in the chamber of his master.

Gossip in a country village travels fast and loses nothing in its passage. Over many a friendly cup of tea did the matrons and maids discuss the peculiarities of the wealthy and eccentric old man who had so suddenly appeared among them, while the male portion of the community speculated illimitably as to his history and his possessions.

He was frequently met walking along the highway with his hands folded behind his back, his head bent down, apparently in deep thought, William in advance, and the master plodding slowly after him, and many efforts were made to cultivate his acquaintance, but always without success.

This evidence of an avoidance of conversation and refusal to make acquaintances, instead of repressing a tendency to gossip, only seemed to supply an opportunity for exaggeration, and speculation largely supplied the want of fact in regard to his wealth and his antecedents.

Entirely undisturbed by the many reports in circulation about him, Henry Schulte pursued the isolated life he seemed to prefer, paying no heed to the curious eyes that were bent upon him, and entirely oblivious to the vast amount of interest which others evinced in his welfare.

He was in the habit of making frequent journeys to the City of New York alone, and on these occasions William would meet him upon his return and the two would then pursue their lonely walk home.

One day upon reaching South Norwalk, after a visit to the metropolis, he brought with him a large iron box which he immediately consigned to the safe keeping of the bank located in the town, and this fact furnished another and more important subject for conversation.

He had hitherto seemed to have no confidence in banking institutions and trust companies, and preferred to be his own banker, carrying large sums of money about his person which he was at no pains to conceal, and so, as he continued this practice, and as his possessions were seemingly increased by the portentous-looking iron chest, the speculations as to his wealth became unbounded.

Many of the old gossips had no hesitancy in declaring that he was none other than a foreign count or some other scion of nobility, who had, no doubt, left his native land on account of some political persecution, or that he had been expatriated by his government for some offense which had gained for the old man that dreadful punishment—royal disfavor.

Oblivious of all this, however, the innocent occasion of their wonderment and speculation pursued his lonely way unheeding and undisturbed.

William Bucholz.—Life at Roton Hill.—A Visit to New York City.

William Bucholz, the servant of the old gentleman, did not possess the morose disposition nor the desire for isolation evinced by his master, for, instead of shunning the society of those with whom he came in contact, he made many acquaintances during his leisure hours among the people of the town and village, and with whom he soon became on terms of perfect intimacy. To him, therefore, perhaps as much as to any other agency, was due in a great measure the fabulous stories of the old man's wealth.

Being of a communicative disposition, and gifted with a seemingly frank and open manner, he found no difficulty in extending his circle of acquaintances, particularly among those of a curious turn of mind. In response to their eager questioning, he would relate such wonderful stories in reference to his master, of the large amount of money which he daily carried about his person, and of reputed wealth in Germany, that it was believed by some that a modern Crœsus had settled in their midst, and while, in common with the rest of humanity, they paid homage to his gold, they could not repress a feeling of contempt for the miserly actions and parsimonious dealings of its possessor.

With the young ladies also William seemed to be a favorite, and his manner of expressing himself in such English words as he had acquired, afforded them much interest and no little amusement. Above all the rest, however, the two daughters of Mrs. Waring possessed the greatest attractions for him, and the major part of his time, when not engaged in attending upon his employer, was spent in their company. Of the eldest daughter he appeared to be a devoted admirer, and this fact was far from being disagreeable to the young lady herself, who smiled her sweetest smiles upon the sturdy young German who sued for her favors.

Sadie Waring was a wild, frolicsome young lady of about twenty years of age, with an impulsive disposition, and an inclination for mischief which was irrepressible. Several experiences were related of her, which, while not being of a nature to deserve the censure of her associates, frequently brought upon her the reproof of her parents, who looked with disfavor upon the exuberance of a disposition that acknowledged no control.

Bucholz and Sadie became warm friends, and during the pleasant days of the early Autumn, they indulged in frequent and extended rambles; he became her constant chaperone to the various traveling shows which visited the town, and to the merry-makings in the vicinity. Through her influence also, he engaged the services of a tutor, and commenced the study of the English language, in which, with her assistance, he soon began to make rapid progress.

In this quiet, uneventful way, the time passed on, and nothing occurred to disturb the usual serenity of their existence. No attempt was made by Henry Schulte to cultivate the land which he had purchased, and, except a small patch of ground which was devoted to the raising of a few late vegetables, the grass and weeds vied with each other for supremacy in the broad acres which surrounded the house.

Daily during the pleasant weather the old gentleman would wend his way to the river, and indulge in the luxury of a bath, which seemed to be the only recreation that he permitted himself to take; and in the evening, during which he invariably remained in the house, he would spend the few hours before retiring in playing upon the violin, an instrument of which he was very fond, and upon which he played with no ordinary skill.

The Autumn passed away, and Winter, cold, bleak, and cheerless, settled over the land. The bright and many-colored leaves that had flashed their myriad beauties in the full glare of the sunlight, had fallen from the trees, leaving their trunks, gnarled and bare, to the mercy of the sweeping winds. The streams were frozen, and the merry-makers skimmed lightly and gracefully over the glassy surface of pond and lake. Christmas, that season of festivity, when the hearts of the children are gladdened by the visit of that fabulous gift-maker, and when music and joy rule the hour in the homes of the rich—but when also, pinched faces and hungry eyes are seen in the houses of the poor—had come and gone.

To the farm-house on the "Hill," there had come no change during this festive season, and the day was passed in the ordinary dull and uneventful manner. William Bucholz and Sadie Waring had perhaps derived more enjoyment from the day than any of the others, and in the afternoon had joined a party of skaters on the lake in the vicinity, but beyond this, no incident occurred to recall very forcibly the joyous time that was passing.

On the second day after Christmas, Henry Schulte informed William of his intention to go to New York upon a matter of business, and after a scanty breakfast, accompanied by his valet, he wended his way to the station.

They had become accustomed to ignore the main road in their journeys to the town, and taking a path that ran from the rear of the house, they would walk over the fields, now hard and frozen, and passing through a little strip of woods they would reach the track of the railroad, and following this they would reach the station, thereby materially lessening the distance that intervened, and shortening the time that would be necessary to reach their destination.

Placing the old gentleman safely upon the train, and with instructions to meet him upon his arrival home in the evening, Bucholz retraced his steps and prepared to enjoy the leisure accorded to him by the absence of the master.

In the afternoon his tutor came, and he spent an hour engaged in the study of the English language, and in writing. Shortly after the departure of the teacher Mrs. Waring requested him to accompany her to a town a few miles distant, whither she was going to transact some business, and he cheerfully consenting, they went off together.

Returning in the gathering twilight Bucholz was in excellent spirits and in great good humor, and as they neared their dwelling they discovered Sadie slightly in advance of them, with her skates under her arm, returning from the lake, where she had been spending the afternoon in skating. William, with a view of having a laugh at the expense of the young lady, when within a short distance of her, drew a revolver which he carried, and discharged it in the direction in which she was walking. The girl uttered a frightened scream, but William's mocking laughter reassured her, and after a mutual laugh at her sudden fright the three proceeded merrily to the house.

It was now time for William to go to the station for his master, who was to return that evening, and he started off to walk to the train, reaching there in good time, and in advance of its arrival.

Soon the bright light of the locomotive was seen coming around a curve in the road, the shrill whistle resounded through the wintry air, and in a few minutes the train came rumbling up to the station, when instantly all was bustle and confusion.

Train hands were running hither and thither, porters were loudly calling the names of the hotels to which they were attached, the inevitable Jehu was there with his nasal ejaculation of "Kerige!" while trunks were unloaded and passengers were disembarking.

Bright eyes were among the eager crowd as the friendly salutations were exchanged, and merry voices were heard in greeting to returning friends. Rich and poor jostled each other in the hurry of the moment, and the waiting servant soon discovered among the passengers the form of the man he was waiting for.

The old gentleman was burdened with some purchases of provisions which he had made, and in an old satchel which he carried the necks of several bottles of wine were protruding. Assisting him to alight, Bucholz took the satchel, and they waited until the train started from the depot and left the trackway clear. The old man looked fatigued and worn, and directed Bucholz to accompany him to a saloon opposite, which they entered, and walking up to the bar, he requested a couple of bottles of beer for himself and servant. This evidence of unwonted generosity created considerable wonderment among those who were seated around, but the old gentleman paid no attention to their whispered comments, and, after liquidating his indebtedness, the two took up their packages and proceeded up the track upon their journey home.

What transpired upon that homeward journey was destined to remain for a long time an inscrutable mystery, but after leaving that little inn no man among the curious villagers ever looked upon that old man's face in life again. The two forms faded away in the distance, and the weary wind sighed through the leafless trees; the bright glare of the lights of the station gleamed behind them, but the shadows of the melancholy hills seemed to envelop them in their dark embrace—and to one of them, at least, it was the embrace of death.

An Alarm at the Farm-house.—The Dreadful Announcement of William Bucholz.—The Finding of the Murdered Man.

The evening shadows gathered over Roton Hill, and darkness settled over the scene. The wind rustled mournfully through the leafless branches of the trees, as though with a soft, sad sigh, while overhead the stars glittered coldly in their far-off setting of blue.

Within the farm-house the fire glowed brightly and cheerily; the lamps were lighted; the cloth had been laid for the frugal evening meal, and the kettle hummed musically upon the hob. The family of the Warings, with the exception of the father, whose business was in a distant city, were gathered together. Samuel Waring, the son, had returned from his labor, and with the two girls were seated around the hearth awaiting the return of the old gentleman and William, while Mrs. Waring busied herself in the preparations for tea.

"Now, if Mr. Schulte would come," said Mrs. Waring, "we would ask him to take tea with us this evening; the poor man will be cold and hungry."

"No use in asking him, mother," replied Samuel, "he wouldn't accept."

"It is pretty nearly time they were here," said Sadie, with a longing look toward the inviting table.

"Well, if they do not come soon we will not wait for them," said Mrs. Waring.

As she spoke a shrill, startled cry rose upon the air; the voice of a man, and evidently in distress. Breathless they stopped to listen—the two girls clinging to each other with blanched faces and staring eyes.

"Sammy! Sammy!" again sounded that frightened call.

Samuel Waring started to his feet and moved rapidly toward the door.

"It sounds like William!" he cried, "something must have happened."

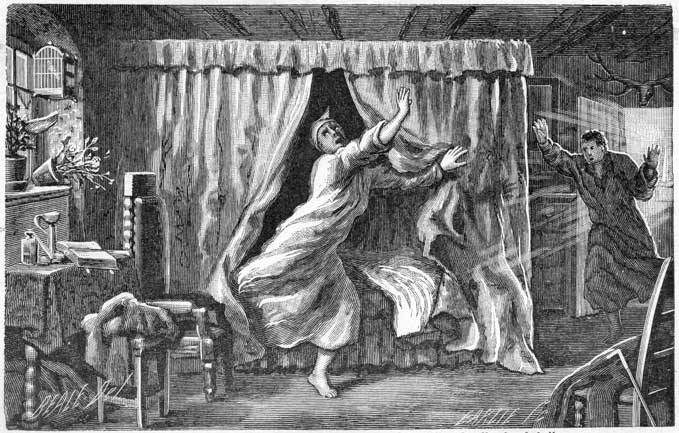

He had reached the door and his hand was upon the latch, when it was violently thrown open and Bucholz rushed in and fell fainting upon the floor.

"Bucholz rushed in and fell fainting to the floor."

He was instantly surrounded by the astonished family, and upon examination it was discovered that his face was bleeding, while the flesh was lacerated as though he had been struck with some sharp instrument. He had carried in his hand the old satchel which contained the wine purchased by Mr. Schulte, and which had been consigned to his care on leaving the depot, and as he fell unconscious the satchel dropped from his nerveless grasp upon the floor.

Recovering quickly, he stared wildly around. "What has happened, William, what is the matter?" inquired Samuel.

"Oh, Mr. Schulte, he is killed, he is killed!"

"Where is he now?"

"Down in the woods by the railroad," cried Bucholz. "We must go and find him."

Meanwhile the female members of the family had stood wonder-stricken at the sudden appearance of Bucholz, and the fearful information which he conveyed.

"How did it happen?" inquired Samuel Waring.

"Oh, Sammy," exclaimed Bucholz, "I don't know. When we left the station, Mr. Schulte gave me the satchel to carry, and we walked along the track. I was walking ahead. Then we came through the woods, and just as I was about to climb over the stone wall by the field, I heard Mr. Schulte call out, 'Bucholz!' 'Bucholz!' It was dark, I could not see anything, and just as I turned around to go to Mr. Schulte, a man sprang at me and hit me in the face. I jumped away from him and then I saw another one on the other side of me. Then I ran home, and now I know that Mr. Schulte is killed. Oh Sammy! Sammy! we must go and find him."

Bucholz told his story brokenly and seemed to be in great distress.

"If I had my pistol I would not run," he continued, as if in reply to a look upon Samuel Waring's face, "but I left it at home."

Sadie went up to him, and, laying her hand upon his arm, inquired anxiously if he was much hurt.

"No, my dear, I think not, but I was struck pretty hard," he replied. "But come," he continued, "while we are talking, Mr. Schulte is lying out there in the woods. We must go after him."

Bucholz went to the place where he usually kept his revolver, and placing it in his pocket, he announced his readiness to go in search of his master.

"Wait till I get my gun," said Samuel Waring, going up-stairs, and soon returning with the desired article.

Just as he returned, another attack of faintness overcame William, and again he fell to the floor, dropping the revolver from his pocket as he did so.

Sammy assisted him to arise, and after he had sufficiently recovered, the two men, accompanied by the mother and two daughters, started toward the house of the next neighbor, where, arousing old Farmer Allen, and leaving the ladies in his care, they proceeded in the direction where the attack was said to have been made.

On their way they aroused two other neighbors, who, lighting lanterns, joined the party in their search for the body of Mr. Schulte.

Following the beaten path through the fields, and climbing over the stone wall where Bucholz was reported to have been attacked, they struck the narrow path that led through the woods. A short distance beyond this the flickering rays of the lantern, as they penetrated into the darkness beyond them, fell upon the prostrate form of a man.

The body lay upon its back; the clothing had been forcibly torn open, and the coat and vest were thrown back as though they had been hastily searched and hurriedly abandoned.

The man was dead. Those glassy eyes, with their look of horror, which were reflected in the rays of the glimmering light; that pallid, rigid face, with blood drops upon the sunken cheeks, told them too plainly that the life of that old man had departed, and that they stood in the awful presence of death.

Murdered! A terrible word, even when used in the recital of an event that happened long ago. An awful word to be uttered by the cheerful fireside as we read of the ordinary circumstances of every-day life. But what horrible intensity is given to the enunciation of its syllables when it is forced from the trembling lips of stalwart men, as they stand like weird spirits in the darkness of the night, and with staring eyes, behold the bleeding victim of a man's foul deed. It seemed to thrill the ears and freeze the blood of the listeners, as old Farmer Allen, kneeling down by that lifeless form, pronounced the direful word.

It seemed to penetrate the air confusedly—not as a word, but as a sound of fear and dread. The wind seemed to take up the burden of the sad refrain, and whispered it shudderingly to the tall trees that shook their trembling branches beneath its blast.

I wonder did it penetrate into the crime-stained heart of him who had laid this harmless old man low? Was it even now ringing in his ears? Ah, strive as he may—earth and sky and air will repeat in chorus that dreadful sound, which is but the echo of his own accusing conscience, and he will never cease to hear it until, worn and weary, the plotting brain shall cease its functions, and the murderous heart shall be cold and pulseless in a dishonored grave.

The Excitement in the Village.—The Coroner's Investigation.—The Secret Ambuscade.

Samuel Waring knelt down beside the form of the old man, and laid his trembling hand upon the heart that had ceased to throb forever.

"He is dead!" he uttered, in a low, subdued voice, as though he too was impressed with the solemnity of the scene.

Bucholz uttered a half articulate moan, and grasped more firmly in his nerveless hand the pistol which he carried.

One of the neighbors who had accompanied the party was about to search the pockets of the murdered man, when Farmer Allen, raising his hand, cried:

"Stop! This is work for the law. A man has been murdered, and the officers of the law must be informed of it. Who will go?"

Samuel Waring and Bucholz at once volunteered their services and started towards the village to notify the coroner, and those whose duty it was to take charge of such cases.

Farmer Allen gazed at the rigid form of the old man lying there before him, whose life had been such an enigma to his neighbors, then at the retreating forms of the two men who were slowly wending their way to the village, and a strange, uncertain light came into his eyes as he thus looked. He said nothing, however, of the thoughts that occupied his mind, and after bidding the others watch beside the body, he returned to his own home and informed the frightened females of what had been discovered.

The news spread with wonderful rapidity, and soon the dreadful tidings were the theme of universal conversation. A man rushed into the saloon in which the old man and Bucholz had drank their beer, and cried out:

"The old man that was in here to-night has been murdered!"

Instantly everybody were upon their feet. The old gentleman was generally known, and although no one was intimately acquainted with him, all seemed to evince an interest in the cause of his death.

Many rumors were at once put in circulation, and many wild and extravagant stories were soon floating through the crowds that gathered at the corners of the streets.

Samuel Waring and Bucholz had gone directly to the office of the coroner, and informing him of the sad affair, had proceeded to the drug-store in the village, with the view of having the wounds upon his face dressed. They were found to be of a very slight character, and a few pieces of court-plaster dexterously applied were all that seemed to be required.

By this time the coroner had succeeded in impanneling a jury to accompany him to the scene of the murder, and they proceeded in a body toward the place. The lights from the lanterns, held by those who watched beside the body, directed them to the spot, and they soon arrived at the scene of the tragedy.

The coroner immediately took charge of the body, and the physician who accompanied him made an examination into the cause of his death.

Upon turning the body over, two ugly gashes were found in the back of his head, one of them cutting completely through the hat which covered it and cutting off a piece of the skull, and the other penetrating several inches into the brain, forcing the fractured bones of the skull inward.

It seemed evident that the first blow had been struck some distance from the place where the body had fallen, and that the stunned man had staggered nearly thirty feet before he fell. The second blow, which was immediately behind the left ear, had been dealt with the blunt end of an axe, and while he was prostrate upon the ground.

Death must have instantly followed this second crushing blow, and he had died without a struggle. Silently and stealthily the assassins must have come upon him, and perhaps in the midst of some pleasant dream of a boyhood home; some sweet whisper of a love of the long ago, his life had been beaten out by the murderous hand of one who had been lying in wait for his unsuspecting victim.

From the nature of the wounds the physician at once declared that they were produced by an axe. The cut in the back of the head, and from which the blood had profusely flowed, was of the exact shape of the blade of an instrument of that nature—and the other must have been produced by the back of the same weapon. The last blow must have been a crushing one, for the wound produced was several inches deep.

An examination of the body revealed the fact that the clothing had been forcibly torn open, as several buttons had been pulled from the vest which he wore, in the frantic effort to secure the wealth which he was supposed to have carried upon his person.

In the inner pocket of his coat, which had evidently been overlooked by the murderers, was discovered a worn, yellow envelope, which, on being opened, was found to contain twenty thousand dollars in German mark bills, and about nine hundred and forty dollars in United States government notes. His watch had been wrenched from the guard around his neck, and had been carried off, while by his side lay an empty money purse, and some old letters and newspapers.

Tenderly and reverently they lifted the corpse from the ground after this examination had been made, William Bucholz assisting, and the mournful procession bore the body to the home which he had left in the morning in health and spirits, and with no premonitory warning of the fearful fate that was to overtake him upon his return.

The lights flashed through the darkness, and the dark forms, outlined in their glimmering beams, seemed like beings of an unreal world; the bearers of the body, with their unconscious burden, appeared like a mournful procession of medieval times, when in the solemn hours of the night the bodies of the dead were borne away to their final resting-place.

They entered the house and laid their burden down. The lids were now closed over those wild, staring eyes, and the clothing had been decently arranged about the rigid form. The harsh lines that had marked his face in life, seemed to have been smoothed away by some unseen hand, and a smile of peace, such as he might have worn when a child, rested upon those closed and pallid lips, clothing the features with an expression of sweetness that none who saw him then ever remembered to have seen before.

After depositing the body in the house, several of the parties proceeded to search the grounds in the immediate vicinity of the murder. Near where the body had fallen a package was found, containing some meat which the frugal old man had evidently purchased while in the city. Another parcel, which contained a pair of what are commonly known as overalls, apparently new and unworn, was also discovered. An old pistol of the "pepper-box" pattern, and a rusty revolver, the handle of which was smeared with blood, was found near where the body was lying. No instrument by which the murder could have been committed was discovered, and no clue that would lead to the identification of the murderers was unearthed. They were about to abandon their labor for the night, when an important discovery was made, which tended to show conclusively that the murder had been premeditated, and that the crime had been in preparation before the hour of its execution.

By the side of the narrow path which led through the woods, stood a small cedar tree upon the summit of a slight rise in the ground. Its spare, straggling branches were found to have been interwoven with branches of another tree, so as to form a complete screen from the approach from the railroad, in the direction which Henry Schulte must inevitably come on his way from the depot. Here, undoubtedly, the murderer had been concealed, and as the old man passed by, unconscious of the danger that threatened him, he had glided stealthily after him and struck the murderous blow.

These, and these only, were the facts discovered, and the question as to whose hand had committed the foul deed remained a seemingly fathomless mystery.

Midnight tolled its solemn hour, and as the tones of the bell that rang out its numbers died away upon the air, the weary party wended their way homeward, leaving the dead and the living in the little farm-house upon the "Hill," memorable ever after for the dark deed of this dreary night.

The Hearing before the Coroner.—Romantic Rumors and Vague Suspicions.—An Unexpected Telegram.—Bucholz Suspected.

The next day the sun shone gloriously over a beautiful winter's day, and as its bright rays lighted up the ice-laden trees in the little wood, causing their branches to shimmer with the brilliant hues of a rainbow's magnificence, no one would have imagined that in the gloom of the night before, a human cry for help had gone up through the quiet air or that a human life had been beaten out under their glittering branches.

The night had been drearily spent in the home which Henry Schulte had occupied, and the body of the murdered man had been guarded by officers of the law, designated by the coroner who designed holding the customary inquest upon the morrow.

To the inmates of the house the hours had stretched their weary lengths along, and sleep came tardily to bring relief to their overwrought minds. Bucholz, nervous and uneasy, had, without undressing, thrown himself upon the bed with Sammy Waring, and during his broken slumbers had frequently started nervously and uttered moaning exclamations of pain or fear, and in the morning arose feverish and unrefreshed.

The two girls, who had wept profusely during the night, and before whose minds there flitted unpleasant anticipations of a public examination, in which they would no doubt play prominent parts, and from which they involuntarily shrank, made their appearance at the table heavy-eyed and sorrowful.

As the morning advanced, hundreds of the villagers, prompted by idle curiosity and that inherent love of excitement which characterizes all communities, visited the scene of the murder, and as they gazed vacantly around, or pointed out the place where the body had been found, many and varied opinions were expressed as to the manner in which the deed was committed, and of the individuals who were concerned in the perpetration of the crime.

A rumor, vague at first, but assuming systematic proportions as the various points of information were elucidated, passed through the crowd, and was eagerly accepted as the solution of the seeming mystery.

It appeared that several loungers around the depot at Stamford, a town about eight miles distant, on the night previous had observed two conspicuous-looking foreigners, who had reached the depot at about ten o'clock. They seemed to be exhausted and out of breath, as though they had been running a long distance, and in broken English, scarcely intelligible, had inquired (in an apparently excited manner), when the next train was to leave for New York. There were several cabmen and hangers-on who usually make a railroad depot their headquarters about, and by them the two men were informed that there were no more trains running to New York that night. This information seemed to occasion them considerable annoyance and disappointment; they walked up and down the platform talking and gesticulating excitedly, and separating ever and anon, when they imagined themselves noticed by those who happened to be at the station.

Soon after this an eastern-bound train reached the depot, and these same individuals, instead of going to New York, took passage on this train. They did not go into the car together, and after entering took seats quite apart from each other. The conductor, who had mentioned these circumstances, and who distinctly remembered the parties, as they had especially attracted his attention by their strange behavior, recollected that they did not present any tickets, but paid their fares in money. He also remembered that they were odd-looking and acted in an awkward manner. They both left the train at New Haven, and from thence all trace of them was lost for the present.

Upon this slight foundation, a wonderful edifice of speculation was built by the credulous and imaginative people of South Norwalk. The romance of their dispositions was stirred to its very depths, and their enthusiastic minds drew a vivid picture, in which the manner and cause of Henry Schulte's death was successfully explained and duly accounted for.

These men were without a doubt the emissaries of some person or persons in Germany, who were interested in the old gentleman and would be benefited by his death. As this story coincided so fully with the mysterious appearance of the old man at South Norwalk; his recluse habits and avoidance of society, it soon gained many believers, who were thoroughly convinced of the correctness of the theory thus advanced.

Meanwhile the coroner had made the necessary arrangements for the holding of the inquest as required by the law, and his office was soon crowded to overflowing by the eager citizens of the village, who pushed and jostled each other in their attempts to effect an entrance into the room.

The first and most important witness was William Bucholz, the servant of the old gentleman, and who had accompanied him on that fatal walk home.

He told his story in a plain, straightforward manner, and without any show of hesitation or embarrassment. He described his meeting Mr. Schulte at the depot; their entering the saloon, and their journey homeward.

"After we left the saloon," said Bucholz, who was allowed to tell his story without interruption and without questioning, "Mr. Schulte said to me, 'Now, William, we will go home;' we walked up the railroad track and when we reached the stone wall that is built along by the road, Mr. Schulte told me to take the satchel, and as the path was narrow, he directed me to walk in advance of him. He was silent, and, I thought, looked very tired. I had not walked very far into the woods, when I heard him call from behind me, as though he was hurt or frightened, 'Bucholz! Bucholz!' I heard no blow struck, nor any sound of footsteps. I was startled with the suddenness of the cry, and as I was about to lay down the satchel and go to him, I saw a man on my right hand about six paces from me; at the same time I heard a noise on my left, and as I turned in that direction I received a blow upon my face. This frightened me so that I turned, and leaping over the wall, I ran as fast as I could towards the house. One of the men, who was tall and stoutly built, chased me till I got within a short distance of the barn. He then stopped, and calling out, 'Greenhorn, I catch you another time,' he went back in the direction of the woods. He spoke in English, but from his accent I should think he was a Frenchman. I did not stop running until I reached the house, and calling for help to Sammy Waring, I opened the door and fell down. I was exhausted, and the blow I received had hurt me very much." He then proceeded to detail the incidents which followed, all of which the reader has already been made aware of.

He told his story in German, and, through one of the citizens present, who acted as interpreter, it was translated into English. While he was speaking, a boy hurriedly entered the room, and pushing his way toward the coroner, who was conducting the examination, he handed to him a sealed envelope.

Upon reading the meager, but startling, contents of the telegram, for such it proved to be, Mr. Craw gazed at Bucholz with an expression of pained surprise, in which sympathy and doubtfulness seemed to contend for mastery.

The telegram was from the State's Attorney, Mr. Olmstead, who, while on the train, going from Stamford to Bridgeport, had perused the account of the murder of the night before, in the daily journal. Being a man of clear understanding, of quick impulse, and indomitable will, for him to think was to act. Learning that the investigation was to be held that morning, immediately upon his arrival at Bridgeport he entered the telegraph office, and sent the following dispatch:

"Arrest the servant."

It was this message which was received by the coroner, while Bucholz, all unconscious of the danger which threatened him, was relating the circumstances that had occurred the night before.

Mr. Craw communicated to no one the contents of the message he had received, and the investigation was continued as though nothing had occurred to disturb the regularity of the proceedings thus begun.

Mr. Olmstead, however, determined to allow nothing to interfere with the proper carrying out of the theory which his mind had formed, and taking the next train, he returned to South Norwalk, arriving there before Bucholz had finished his statement.

When he entered the room he found that Bucholz had not been arrested as yet, and so, instead of having this done, he resolved to place an officer in charge of him, thus preventing any attempt to escape, should such be made, and depriving him practically of the services of legal counsel.

Mr. Olmstead conducted the proceedings before the coroner, and his questioning of the various witnesses soon developed the theory he had formed, and those who were present listened with surprise as the assumption of Bucholz's guilty participation in the murder of his master was gradually unfolded.

Yet under the searching examination that followed, Bucholz never flinched; he seemed oblivious of the fact that he was suspected, and told his story in an emotionless manner, and with an innocent expression of countenance that was convincing to most of those who listened to his recital.

No person ever appeared more innocent under such trying circumstances than did this man, and but for a slight flush that now and then appeared upon his face, one would have been at a loss to discover any evidence of feeling upon his part, which would show that he was alive to the position which he then occupied.

His bearing at the investigation made him many friends who were very outspoken in their defense of Bucholz, and their belief in his entire innocence. Mr. Olmstead, however, was resolute, and Bucholz returned to the house upon the conclusion of the testimony for that day, in charge of an officer of the law, who was instructed to treat him kindly, but under no circumstances to allow him out of his sight, and the further investigation was deferred until the following week.

The Miser's Wealth.—Over Fifty Thousand Dollars Stolen from the Murdered Man.—A Strange Financial Transaction.—A Verdict, and the Arrest of Bucholz.

Meantime there existed a necessity for some action in regard to the effects of which Henry Schulte was possessed at the time of his death, and two reputable gentlemen of South Norwalk were duly authorized to act as administrators of his estate, and to perform such necessary duties as were required in the matter.

From an examination of his papers it was discovered that his only living relatives consisted of a brother and his family, who resided near Dortmund, Westphalia, in Prussia, and that they too were apparently wealthy and extensive land-owners in the vicinity of that place.

To this brother the information was immediately telegraphed of the old gentleman's death, and the inquiry was made as to the disposition of the body. To this inquiry the following reply was received:

"To the Mayor of South Norwalk:

"I beg of you to see that the body of my brother is properly forwarded to Barop, near Dortmund, so as to insure its safe arrival. I further request that you inform me at once whether his effects have been secured, and how much has been found of the large amount of specie which he took with him from here? Have they found the murderer of my brother?

Signed, "Fredrick W. Schulte."

Had those who knew the previous history of Henry Schulte expected to have received any expression of sorrow for the death of the old gentleman, they were doomed to be disappointed, and the telegram itself fully dissipated any such idea. The man was dead, and the heirs were claiming their inheritance—that was all.

Shortly after this a representative of the German Consul at New York arrived, and, presenting his authority, at once proceeded to take charge of the remains, and to make the arrangements necessary towards having them sent to Europe.

The iron box which had proved such an object of interest to the residents of South Norwalk, was opened at the bank, and to the surprise of many, was found to contain valuable securities and investments which represented nearly a quarter of a million of dollars.

It was at first supposed that the murderers had been foiled in their attempt to rob as well as to murder, or that they had been frightened off before they had accomplished their purpose of plunder. The finding of twenty thousand dollars upon his person seemed to be convincing proof that no robbery had been committed, and the friends of Bucholz, who were numerous, pointed to this fact as significantly establishing his innocence.

Indeed, many people wondered at the action of the State's attorney, and doubtfully shook their heads as they thought of the meager evidence that existed to connect Bucholz with the crime. A further examination of the accounts of the murdered man, however, disclosed the startling fact that a sum of money aggregating to over fifty thousand dollars had disappeared, and, as he was supposed to have carried this amount upon his person, it must have been taken from him on the night of the murder.

Here, then, was food for speculation. The man had been killed, and robbery had undoubtedly been the incentive. Who could have committed the deed and so successfully have escaped suspicion and detection?

Could it have been William Bucholz?

Of a certainty the opportunity had been afforded him, and he could have struck the old man down with no one near to tell the story. But if, in the silence of that lonely evening, his hand had dealt the fatal blow, where was the instrument with which the deed was committed? If he had rifled the dead man's pockets and had taken from him his greedily hoarded wealth, where was it now secured, or what disposition had he made of it?

From the time that he had fallen fainting upon the floor of the farm-house kitchen, until the present, he was not known to have been alone.

Tearful in his grief for the death of his master, his voice had been the first that suggested the necessity for going in search of him. He was seen to go to the place where he usually kept his pistol, and prepare himself for defense in accompanying Samuel Waring.

He had stood sorrowfully beside that prostrate form as the hand of the neighbor had been laid upon the stilled and silent heart, and life had been pronounced extinct. He had journeyed with Sammy Waring to the village to give the alarm and to notify the coroner, and on his return his arms had assisted in carrying the unconscious burden to the house. Could a murderer, fresh from his bloody work, have done this?

From that evening officers had been in charge of the premises. Bucholz, nervous, and physically worn out, had retired with Sammy Waring, and had not left the house during the evening. If he had committed this deed he must have the money, but the house was thoroughly searched, and no trace of this money was discovered.

His bearing upon the inquest had been such that scarcely any one present was disposed to believe in his guilty participation in the foul crime, or that he had any knowledge of the circumstances, save such as he had previously related.

Where then was this large sum of money which had so mysteriously disappeared?

A stack of straw that stood beside the barn—the barn had been thoroughly searched before—was purchased by an enterprising and ambitious officer in charge of Bucholz, and although he did not own a horse, he had the stack removed, the ground surrounding it diligently searched, in the vague hope that something would be discovered hidden beneath it.

But thus far, speculation, search and inquiry had availed nothing, and as the crowd gathered at the station, and the sealed casket that contained the body of the murdered man was placed upon the train to begin its journey to the far distant home which he had left but a short time before, many thought that with its departure there had also disappeared all possibility of discovering his assassin, and penetrating into the deep mystery which surrounded his death.

An important discovery was, however, made at this time, which changed the current of affairs, and seemed for a time to react against the innocence of the man against whom suspicion attached.

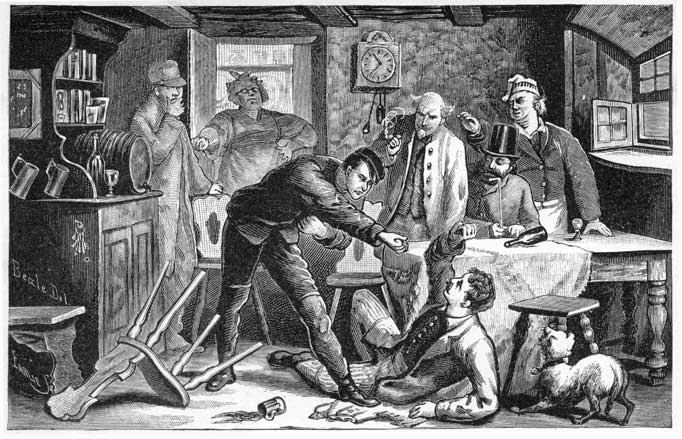

In the village there resided an individual named Paul Herscher, who was the proprietor of the saloon in which the deceased and his servant had taken their drink of beer, after leaving the train upon the night of the murder.

During the residence of Mr. Schulte at Roton Hill, Bucholz and Paul Herscher had become intimate acquaintances, and Bucholz had stated upon his examination that during the month of the previous October he had loaned to Paul the sum of two hundred dollars. That the servant of so parsimonious a man should have been possessed of such a sum of money seemed very doubtful, and inquiries were started with the view of ascertaining the facts of the case.

The investigation was still going on, and Paul was called as a witness. His story went far towards disturbing the implicit confidence in Bucholz's innocence, and caused a reaction of feeling in the minds of many, which, while it did not confirm them in a belief in his guilt, at least made them doubtful of his entire ignorance of the crime.

Paul Herscher stated that on the morning after the murder Bucholz had entered his saloon, and calling him into an adjoining room, had placed in his hands a roll of bills, saying at the same time, in German:

"Here is two hundred dollars of my money. I want you to keep it until I make my report to the coroner. If anybody asks you about it, tell them I gave it to you some time ago."

Here was an attempt to deceive somebody, and, although Paul had retained this money for several days, without mentioning the fact of its existence, his revelation had its effect. Upon comparing the notes, all of which were marked with a peculiar arrangement of numbers, and by the hand of the deceased, they were found to correspond with a list found among the papers of Henry Schulte, and then in the custody of his administrators.

To this charge, however, Bucholz gave a free, full and, so far as outward demeanor was concerned, truthful explanation, which, while it failed to fully satisfy the minds of those who heard it, served to make them less confident of his duplicity or his guilt.

He acknowledged the statements made by Paul Herscher to be true, but stated in explanation that he received the money from Mr. Schulte on their way home on the evening of the murder, in payment of a debt due him, and that, fearing he might be suspected, he had gone to Paul, and handing him the money, had requested him, if inquiries were instituted, to confirm the statement which he had then made.

That this statement seemed of a doubtful character was recognized by every one, and that a full examination into the truthfulness of his assertions was required was admitted by all; and, after other testimony, not, however, of a character implicating him in the murder, was heard, the State's attorney pressed for such a verdict as would result in holding Bucholz over for a trial.

After a long deliberation, in which every portion of the evidence was considered by the jury, which had listened intently to its relation, they returned the following verdict:

"That John Henry Schulte came to his death from wounds inflicted with some unknown instrument, in the hands of some person or persons known to William Bucholz, and we do find that said William Bucholz has a guilty knowledge of said crime."

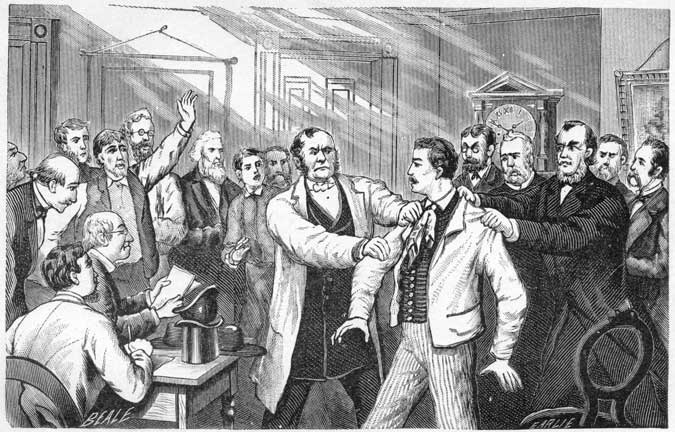

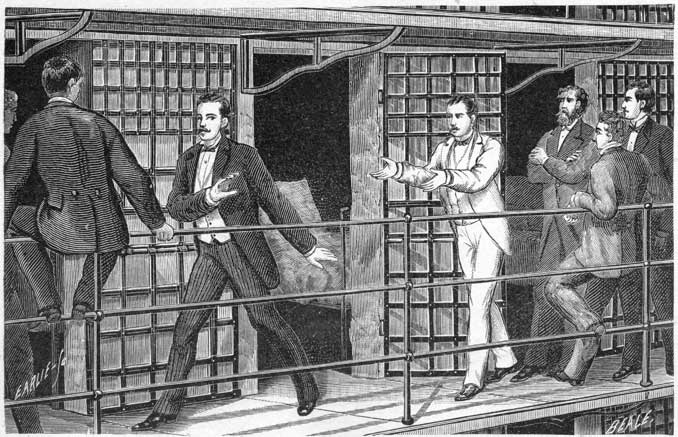

This announcement occasioned great surprise among the people assembled; but to none, perhaps, was the result more unexpected than to William Bucholz himself. He stood in a dazed, uncertain manner for a few moments, and then, uttering a smothered groan, sank heavily in his seat.

The officers of the law advanced and laid their hands upon his shoulder; and, scarcely knowing what he did, and without uttering a word, he arose and followed them from the building. He was placed upon the train to Bridgeport, and before nightfall the iron doors of a prison closed upon him, and he found himself a prisoner to be placed on trial for his life."

"The officers of the law advanced and laid their hands upon his shoulders"—

Bucholz in Prison.—Extravagant Habits and Suspicious Expenditures.—The German Consul Interests Himself.—Bucholz committed.

Sorrowful looks followed the young man as he was conducted away, and frequent words of sympathy and hope were expressed as he passed through the throng on his way to the depot, but he heeded them not. A dull, heavy pain was gnawing at his heart, and a stupor seemed to have settled over his senses. The figures around him appeared like the moving specters in a horrible dream, while a black cloud of despair seemed to envelop him.

He followed the officers meekly, and obeyed their orders in a mechanical manner, that showed too plainly that his mind was wandering from the scenes about him. He looked helplessly around, and did not appear to realize the situation in which he was so suddenly and unexpectedly placed.

He experienced the pangs of hunger, and felt as though food was necessary to stop the dreadful pain which had taken possession of him, but he made no sign, and from the jury-room to the prison he uttered not a word.

It was only when he found himself in the presence of the officials of the prison, whose gloomy walls now surrounded him, that he recovered his equanimity, and when he was ordered to surrender the contents of his clothing, or submit to a search, his eyes flashed with indignation, and the tears that welled up into them dropped upon his pallid cheek.

With a Herculean effort, however, he recovered his strong calmness, and drawing up his erect figure he submitted in silence to the necessary preparations for his being conducted to a cell.

But as the door of the cell clanged to, shutting him in, and the noise reverberated through the dimly-lighted corridors, he clutched wildly at the bars, and with a paroxysm of frenzy seemed as though he would rend them from their fastenings; then, realizing how fruitless were his efforts, he sank upon the narrow bed in a state of stupefying despair.

The pangs of hunger were forgotten now, he could not have partaken of the choicest viands that could have been placed before him, and alone and friendless he fed upon the bitterness of his own thoughts.

In vain did he attempt to close his eyes to the dreadful surroundings, and to clear his confused mind of the horrible visions that appalled him. The dark cloud gathered about him, and he could discover no avenue of escape.

The night was long and terrible, and the throbbing of his brain seemed to measure the minutes as they slowly dragged on, relieved only at intervals by the steady tramp of the keepers, as they went their customary rounds. The lamp from the corridor glowed with an unearthly light upon his haggard face and burning eyes, while his mind restlessly flitted from thought to thought, in the vain attempt of seeking some faint relief from the shadows that surrounded him.

All through the weary watches of the night he walked his narrow cell, miserable and sleepless. Hour after hour went by, but there came no drooping of the heavy lids, betokening the long-looked-for approach of sleep. At length, when the darkness of the night began to flee away and the gray dawn was breaking without, but ere any ray had penetrated the gloom of his comfortless apartment, he threw himself upon the bed, weary, worn and heart-sick—there stole over his senses forgetfulness of his surroundings, and he slept.

The body, worn and insensible, lay upon the narrow couch, but the mind, that wonderful and mysterious agency, was still busy—he dreamed and muttered in his dreaming thoughts.

Oh, for the power to look within, and to know through what scenes he is passing now!

Leaving the young man in the distressing position of a suspected criminal, and deprived of his liberty, let us retrace our steps, and gather up some links in the chain of the testimony against him, which were procured during the days that intervened between the night of the murder and the day of his commitment.

It will be remembered that he had been placed in charge of two officers of South Norwalk, who, without restraining him of his liberty, accompanied him wherever he went, and watched his every movement.

Bucholz soon developed a talent for spending money, which had never been noticed in him before. He became exceedingly extravagant in his habits, purchased clothing for which he had apparently no use, and seemed to have an abundance of funds with which to gratify his tastes. At each place he went and offered a large note in payment of the purchases which he had made, the note was secured by the officers, and was invariably found to contain the peculiar marks which designated that it had once belonged to the murdered man. He displayed a disposition for dissipation, and would drink to excess, smoking inordinately, and indulging in carriage-rides, always in company with the officers, whose watchful eyes never left him and whose vigilance was unrelaxed.

The State's attorney was indefatigable in his efforts to force upon Bucholz the responsibility of the murder, and no means were left untried to accomplish that purpose. As yet the only evidence was his possession of a moderate amount of money, which bore the marks made upon it by the man who had been slain, and which might or might not have come to him in a legitimate manner and for legitimate services.

The important fact still remained that more than fifty thousand dollars had been taken from the body of the old man, and that the murderer, whoever he might be, had possessed himself of that amount. It was considered, therefore, a matter of paramount importance that this money should be recovered, as well as that the identity of the murderer should be established.

The case was a mysterious one, and thus far had defied the efforts of the ablest men who had given their knowledge and their energies to this perplexing matter.

Mr. Olmstead, who remained firm in belief in Bucholz's guilt, and who refused to listen to any theory adverse to this state of affairs, determined in his heart that something should be done that would prove beyond peradventure the correctness of his opinions.

About this time two discoveries were made, which, while affording no additional light upon the mysterious affair, proved conclusively that whoever the guilty parties were they were still industrious in their attempts to avert suspicion and destroy any evidence that might be used against them.

One of these discoveries was the finding of a piece of linen cloth, folded up and partly stained with blood, as though it had been used in wiping some instrument which had been covered with the crimson fluid. This was found a short distance from the scene of the murder, but partially hid by a stone wall, where Bucholz and Samuel Waring were alleged to have stood upon the night of its occurrence.

The other event was the mysterious cutting down of the cedar tree, whose branches had been intertwined with others, and which had evidently been used as an ambuscade by the assassins who had lain in wait for their unsuspecting victim.

Meantime, the German Consul-General had been clothed with full authority to act in the matter, and had become an interested party in the recovery of the large sum of money which had so mysteriously disappeared. With him, however, the position of affairs presented two difficulties which were to be successfully overcome, and two interests which it was his duty to maintain. As the representative of a foreign government, high in authority and with plenary powers of an official nature, he was required to use his utmost efforts to recover the property of a citizen of the country he represented, and at the same time guard, as far as possible, the rights of the accused man, who was also a constituent of his, whose liberty had been restrained and whose life was now in jeopardy.

The course of justice could not be retarded, however, and an investigation duly followed by the grand jury of the County of Fairfield, at which the evidence thus far obtained was presented and William Bucholz was eventually indicted for the murder of John Henry Schulte, and committed to await his trial.

My Agency is Employed—The work of Detection begun.

The events attendant upon the investigation and the consequent imprisonment of Bucholz had consumed much time. The new year had dawned; January had passed away and the second month of the year had nearly run its course before the circumstances heretofore narrated had reached the position in which they now stood.

The ingenuity and resources of the officers at South Norwalk had been fully exerted, and no result further than that already mentioned had been achieved. The evidence against Bucholz, although circumstantially telling against him, was not of sufficient weight or directness to warrant a conviction upon the charge preferred against him. He had employed eminent legal counsel, and their hopeful views of the case had communicated themselves to the mercurial temperament of the prisoner, and visions of a full and entire acquittal from the grave charge under which he was laboring, thronged his brain.

The violence of his grief had abated; his despair had been dissipated by the sunshine of a fondly-cherished hopefulness, and his manner became cheerful and contented.

It was at this time that the services of my agency were called into requisition, and the process of the detection of the real criminal was begun.

Upon arriving at my agency in New York City one morning in the latter part of February, Mr. George H. Bangs, my General Superintendent, was waited upon by a representative of the German Consul-General, who was the bearer of a letter from the Consulate, containing a short account of the murder of Henry Schulte, and placing the matter fully in my hands for the discovery of the following facts:

I. Who is the murderer?

II. Where is the money which is supposed to have been upon the person of Henry Schulte at the time of his death?

Up to this time no information of the particulars of this case had reached my agency, and, except for casual newspaper reports, nothing was known of the affair, nor of the connection which the German Consul had with the matter.

At the interview which followed, however, such information as was known to that officer, who courteously communicated it, was obtained, and my identification with the case began.

It became necessary at the outset that the support of the State's Attorney should be secured, as without that nothing could be successfully accomplished, and an interview was had with Mr. Olmstead, which resulted in his entire and cordial indorsement of our employment.

The difficulties in the way of successful operation beset us at the commencement, and were apparent to the minds of all. The murder had taken place two months prior to our receiving any information concerning it, and many of the traces of the crime that might have existed at the time of its occurrence, and would have been of incalculable assistance to us, were at this late day no doubt obliterated.

Undismayed, however, by the adverse circumstances with which it would be necessary to contend, and with a determination to persevere until success had crowned their efforts, the office was assumed and the work commenced.

Mr. Bangs and my son, Robert A. Pinkerton, who is in charge of my New York agency, procured another interview with Mr. Olmstead, and received from him all the information which he then possessed.

Mr. Olmstead continued firm in his belief that the crime had been committed by Bucholz, and being a man of stern inflexibility of mind, and of a determined disposition, he was resolved that justice should be done and the guilty parties brought to punishment.