Project Gutenberg's Henry of Monmouth, Volume 1, by J. Endell Tyler

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Henry of Monmouth, Volume 1

Memoirs of Henry the Fifth

Author: J. Endell Tyler

Release Date: January 31, 2007 [EBook #20488]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HENRY OF MONMOUTH, VOLUME 1 ***

Produced by Christine P. Travers and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

[Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected.

The original spelling has been retained.

Printer's error corrected:

- Page 18: portophorium to portiphorium.

- Page 27: applition to application.

- Page 42: chace to chase

- Page 80: ' changes to "]

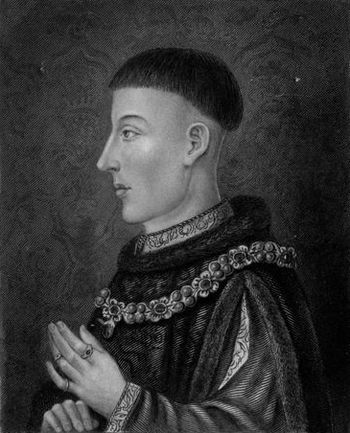

Henry The Fifth

From a drawing by G. P. Harding after an original Picture in

Kensington Palace.

Madam,

The gracious intimation of your Royal pleasure that these Memoirs of your renowned Predecessor should be dedicated to your Majesty, while it increases my solicitude, suggests at the same time new and cheering anticipations. I cannot but hope that, appearing in the world under the auspices of your great name, the religious and moral purposes which this work is designed to serve will be more widely and effectually realised.

Under a lively sense of the literary defects which render these volumes unworthy of so august a patronage, to one point I may revert with feelings of satisfaction and encouragement. I have gone (p. iv) only where Truth seemed to lead me on the way: and this, in your Majesty's judgment, I am assured will compensate for many imperfections.

That your Majesty may ever abundantly enjoy the riches of HIS favour who is the Spirit of Truth, and having long worn your diadem here in honour and peace, in the midst of an affectionate and happy people, may resign it in exchange for an eternal crown in heaven, is the prayer of one who rejoices in the privilege of numbering himself,

Madam,

Among your Majesty's

Most faithful and devoted

Subjects and servants.

J. Endell Tyler.

24, Bedford Square,

May 24, 1838.

Memoirs such as these of Henry of Monmouth might doubtless be made more attractive and entertaining were their Author to supply the deficiencies of authentic records by the inventions of his fancy, and adorn the result of careful inquiry into matters of fact by the descriptive imagery and colourings of fiction. To a writer, also, who could at once handle the pen of the biographer and of the poet, few names would offer a more ample field for the excursive range of historical romance than the life of Henry of Monmouth. From the day of his first compulsory visit to Ireland, abounding as that time does with deeply interesting incidents, to his last hour in the now-ruined castle of Vincennes;—or rather, from his mother's espousals to the interment of his earthly remains within the sacred precincts of Westminster, every period teems with animating suggestions. So far, however, from possessing such adventitious recommendations, the point on which (rather perhaps than any other) an apology might be expected for this work, is, that it has freely tested by (p. vi) the standard of truth those delineations of Henry's character which have contributed to immortalize our great historical dramatist. The Author, indeed, is willing to confess that he would gladly have withdrawn from the task of assaying the substantial accuracy and soundness of Shakspeare's historical and biographical views, could he have done so safely and without a compromise of principle. He would have avoided such an inquiry, not only in deference to the acknowledged rule which does not suffer a poet to be fettered by the rigid shackles of unbending facts; but from a disinclination also to interfere, even in appearance, with the full and free enjoyment of those exquisite scenes of humour, wit, and nature, in which Henry is the hero, and his "riotous, reckless companions" are subordinate in dramatical excellence only to himself. The Author may also not unwillingly grant, that (with the majority of those who give a tone to the "form and pressure" of the age) Shakspeare has done more to invest the character of Henry with a never-dying interest beyond the lot of ordinary monarchs, than the bare records of historical verity could ever have effected. Still he feels that he had no alternative. He must either have ascertained the historical worth of those scenic representations, or have suffered to remain in their full force the deep and prevalent impressions, as to Henry's principles and conduct, which owe, if not their origin, yet, at least, much of their universality and (p. vii) vividness, to Shakspeare. The poet is dear, and our early associations are dear; and pleasures often tasted without satiety are dear: but to every rightly balanced mind Truth will be dearer than all.

It must nevertheless be here intimated, that these volumes are neither exclusively, nor yet especially, designed for the antiquarian student. The Author has indeed sought for genuine information at every fountain-head accessible to him; but he has prepared the result of his researches for the use (he would trust, for the improvement as well as the gratification,) of the general reader. And whilst he has not consciously omitted any essential reference, he has guarded against interrupting the course of his narrative by an unnecessary accumulation of authorities. He is, however, compelled to confess that he rises from this very limited sphere of inquiry under an impression, which grew stronger and deeper as his work advanced, that, before a history of our country can be produced worthy of a place among the records of mankind, the still hidden treasures of the metropolis and of our universities, together with the stores which are known to exist in foreign libraries, must be studied with far more of devoted care and zealous perseverance than have hitherto been bestowed upon them. That the honest and able student, however unwearied in zeal and industry, may be supplied with the indispensable means (p. viii) of verifying what tradition has delivered down, enucleating difficulties, rectifying mistakes, reconciling apparent inconsistencies, clearing up doubts, and removing that mass of confusion and error under which the truth often now lies buried,—our national history must be made a subject of national interest. It is a maxim of our law, and the constant practice of our courts of justice, never to admit evidence unless it be the best which under the circumstances can be obtained. Were this principle of jurisprudence recognised and adopted in historical criticism, the student would carefully ascend to the first witnesses of every period, on whom modern writers (however eloquent or sagacious) must depend for their information. How lamentably devoid of authority and credit is the work of the most popular and celebrated of our modern English historians in consequence of his unhappy neglect of this fundamental principle, will be made palpably evident by the instances which could not be left unnoticed even within the narrow range of these Memoirs. And the Author is generally persuaded that, without a far more comprehensive and intimate acquaintance with original documents than our writers have possessed, or apparently have thought it their duty to cultivate, error will continue to be propagated as heretofore; and our annals will abound with surmises and misrepresentations, instead of being the guardian depositories of historical verity. Only by the acknowledgment and (p. ix) application of the principle here advocated will England be supplied with those monuments of our race, those "POSSESSIONS FOR EVER," as the Prince of Historians[1] once named them, which may instruct the world in the philosophy of moral cause and effect, exhibit honestly and clearly the natural workings of the human heart, and diffuse through the mass of our fellow-creatures a practical assurance that piety, justice, and charity form the only sure groundwork of a people's glory and happiness; while religious and moral depravity in a nation, no less than in an individual, leads, (tardily it may be and remotely, but by ultimate and inevitable consequence,) to failure and degradation.

In those portions of his work which have a more immediate bearing upon religious principles and conduct, the Author has not adopted the most exciting mode of discussing the various subjects which have naturally fallen under his review. Party spirit, though it seldom fails to engender a more absorbing interest for the time, and often clothes a subject with an importance not its own, will find in these pages no response to its sentiments, under whatever character it may give utterance to them. In these departments of his inquiry, to himself far the most interesting, (and many such there are, especially in the second volume,) the Author trusts that he has been guided by the Apostolical maxim of "Speaking the Truth in Love." He has not willingly (p. x) advanced a single sentiment which should unnecessarily cause pain to any individual or to any class of men; he has not been tempted by morbid delicacy or fear to suppress or disguise his view of the very Truth.

The reader will readily perceive that, with reference to the foreign and domestic policy of our country,—the advances of civilization,—the manners of private life, as well in the higher as in the more humble grades of society,—the state of literature,—the progress of the English constitution,—the condition and discipline of the army, which Henry greatly improved,—and the rise and progress of the royal navy, of which he was virtually the founder, many topics are either purposely avoided, or only incidentally and cursorily noticed. To one point especially (a subject in itself most animating and uplifting, and intimately interwoven with the period embraced by these Memoirs,) he would have rejoiced to devote a far greater portion of his book, had it been compatible with the immediate design of his undertaking;—the promise and the dawn of the Reformation.

However the value of his labours may be ultimately appreciated, the Author confidently trusts that their publication can do no disservice to the cause of truth, of sound morality, and of pure religion. He would hope, indeed, that in one point at (p. xi) least the power of an example of pernicious tendency might be weakened by the issue of his investigation. If the results of these inquiries be acquiesced in as sound and just, no young man can be encouraged by Henry's example (as it is feared many, especially in the higher classes, have been encouraged,) in early habits of moral delinquency, with the intention of extricating himself in time from the dominion of his passions, and of becoming, like Henry, in after-life a pattern of religion and virtue, "the mirror of every grace and excellence." The divine, the moralist, and the historian know that authenticated instances of such sudden moral revolutions in character are very rare,—exceptions to the general rule; and among those exceptions we cannot be justified in numbering Henry of Monmouth.

He was bold and merciful and kind, but he was no libertine, in his youth; he was brave and generous and just, but he was no persecutor, in his manhood. On the throne he upheld the royal authority with mingled energy and mildness, and he approved himself to his subjects as a wise and beneficent King; in his private individual capacity he was a bountiful and considerate, though strict and firm master, a warm and sincere friend, a faithful and loving husband. He passed through life under the habitual sense of an overruling Providence; and, in his premature death, he left us the example of a Christian's patient and pious resignation to the Divine Will. As long (p. xii) as he lived, he was an object of the most ardent and enthusiastic admiration, confidence, and love; and, whilst the English monarchy shall remain among the unforgotten things on earth, his memory will be honoured, and his name will be enrolled among the Noble and the Good.

(p. xiii)[*] Those years, months, or days, respectively, to which an asterisk is attached, are not considered to have been so fully ascertained as the other dates.

| 1340* | Feb.* | John of Gaunt born. |

|

1340 1341 |

Earl of Northumberland, Hotspur's father, born, before Nov. 19, 1341. | |

| 1359 | May 19, | John of Gaunt married to Blanche. |

|

1358 1359 |

Owyn Glyndowr born, before Sept. 3, 1359. | |

| 1366 | April 6, | Henry Bolinbroke born. |

|

1365 1366 |

May 20,* | Henry Percy (Hotspur) born before 30th Oct. 1366. |

| 1367 | Jan. | Richard II. born at Bourdeaux. |

| 1369* | Blanche, wife of John of Gaunt died. | |

| 1371* | John of Gaunt married Constance. | |

| 1376 | June 8, | Edward the Black Prince died. |

| 1377 | June 21, | King Edward III. died. |

| 1378 | Nov. | Hotspur first bore arms at Berwick. |

| 1381 | Bolinbroke nearly slain by the rioters. | |

| 1382 | Richard II. married to Queen Anne. | |

| 1384 | Dec. 31, | Wickliffe's death. |

| 1386* | Bolinbroke married Mary Bohun. | |

| 1387 | John of Gaunt went to Spain. | |

| 1387* | Aug. 9,* | Henry born at Monmouth. |

| 1388 | Hotspur taken prisoner by the Scots. | |

| 1388 | Thomas Duke of Clarence born. | |

| 1389 | Nov. 9, | Isabel, Richard II.'s wife, born. (p. xiv) |

| 1389* | Nov.* | John of Gaunt returned from Spain. |

| 1389* | John Duke of Bedford born. | |

| 1390* | Humfrey Duke of Gloucester born. | |

|

1390 1391 |

Bolinbroke visited Barbary. | |

|

1392 1393 |

Bolinbroke visited Prussia and the Holy Sepulchre. | |

| 1394* | Mary, Henry's mother, died. | |

| 1394* | Constance, John of Gaunt's wife, died. | |

| 1394 | June 7, | Anne, Richard II.'s Queen, died. |

| 1396 | John of Gaunt recalled from Acquitaine by Richard II. | |

| 1396 | John of Gaunt married Katharine Swynford. | |

| 1397 | Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, banished. | |

| 1397 | Sept. 29, | Bolinbroke created Duke of Hereford. |

| 1397* | John Oldcastle, Lord Cobham, banished. | |

| 1397 | Nov. 4, | Richard II. married to Isabel. |

| 1398* | Henry of Monmouth resided in Oxford. | |

| 1398 | July 14, | Henry Beaufort consecrated Bishop of Lincoln. |

| 1398 | Sept. 16, | Bolinbroke and Norfolk at Coventry. |

| 1398 | Bolinbroke banished. | |

| 1399 | Feb. 3, | John of Gaunt died. |

| 1399 | May 29, | Richard II. sailed for Ireland. |

| 1399 | June 23, | Henry of Monmouth knighted. |

| 1399 | June 28, | News of Bolinbroke's designs reached London. |

| 1399 | July 4, | Bolinbroke landed at Ravenspur. |

| 1399 | August, | Henry shut up in Trym Castle. |

| 1399 | August, | Richard landed at Milford. |

| 1399 | Aug. 14, | Richard fell into Bolinbroke's hands. |

| 1399 | August, | Bolinbroke sent to Ireland for Henry. |

| 1399 | August, | Death of the young Duke of Gloucester. |

| 1399 | Sept. 1, | Bolinbroke brought Richard captive to London. |

| 1399 | Oct. 1, | Richard's resignation of the crown read in Parliament. (p. xv) |

| 1399 | Oct. 13, | Bolinbroke crowned as Henry IV. |

| 1399 | Oct. 15, | Henry created Prince of Wales. |

| 1400 | Jan. 4, | Conspiracy against the King at Windsor. |

| 1400* | Feb. 14,* | Richard II. died at Pontefract. |

| 1400* | Oct. 25,* | Chaucer died. |

| 1400 | June | Henry IV. proceeded to Scotland. |

| 1400 | June 23, | Lord Grey of Ruthyn's letter to Henry. |

| 1400 | Sept. 19, | First proclamation against the Welsh. |

| 1400 | Owyn Glyndowr in open rebellion. | |

| 1401 | Henry in Wales, before April 10. | |

| 1401 | April 10, | Hotspur's first Letter. |

| 1401* | Sept. 13,* | Katharine, Henry's Queen, born. |

| 1401* | Nov. 11,* | Restoration of Isabel. |

| 1402 | April 3, | Henry IV. espoused to Joan of Navarre. |

| 1402 | June 12,* | Edmund Mortimer taken prisoner. |

| 1402 | Sept. 14, | Battle of Homildon. |

| 1402* | Nov. 30,* | Edmund Mortimer married to a daughter of Owyn Glyndowr. |

| 1403 | March 7, | Henry appointed Lieutenant of Wales. |

| 1403* | May 30, | Henry's Letter to the Council. |

| 1403 | July 21, | Battle of Shrewsbury. |

| 1404 | May 10, | Glyndowr dated "the fourth year of our Principality." |

| 1404 | June 10, | Welsh with Frenchmen overran Archenfield. |

| 1404 | June 25, | Henry's letter to his father. |

| 1404 | Oct. 6, | Parliament at Coventry. |

| 1405 | Feb. 20, | Sons of the Earl of March stolen from Windsor. |

| 1405 | March 1, | Crown settled on Henry and his brothers. |

| 1405 | March 11, | Battle of Grosmont. |

| 1405 | May, | Revolt of the Earl of Northumberland and Bardolf. |

| 1405 | June 8, | Scrope, Archbishop of York, beheaded. |

| 1405 | June 7, | Testimony of the Commons to Henry's excellences. |

| 1406* | June 29,* | Isabel married to Angouleme. |

| 1407* | Nov. 1,* | Henry went to Scotland. (p. xvi) |

| 1408 | Feb. 28,* | Earl of Northumberland, Hotspur's father, fell in battle. |

| 1408 | July 8, | Henry in London, as President of the Council. |

| 1409 | Feb. 1, | Henry, Guardian of the Earl of March. |

| 1409 | Feb. 28, | Henry, Warden of Cinque Ports and Constable of Dover. |

| 1409* | Sept. 13,* | Death of Isabel, Richard II.'s widow. |

| 1410 | March 5, | Warrant for the burning of Badby. |

| 1410 | March 18, | Henry, Captain of Calais. |

| 1410 | June 16, | Henry sate as President of the Council. |

| 1410 | June 18, | Do. do. |

| 1410 | June 19, | Do. do. |

| 1410 | June 23, | Affray in Eastcheap, by the Lords Thomas and John, his brothers. |

| 1410 | July 22, | Henry, as President. |

| 1410 | July 29, | Do. |

| 1410 | July 30, | Do. |

| 1411 | March 19, | Henry with his father at Lambeth. |

| 1411 | August,* | Duke of Burgundy obtained succour. |

| 1411 | Nov. 3, | Parliament opened. |

| 1411 | Nov. 10, | Battle of St. Cloud. |

| 1412 | May 18, | Treaty with the Duke of Orleans. |

| 1412* | June 30,* | Henry came to London attended by "Lords and Gentils." |

| 1412 | July 9, | The Lord Thomas created Duke of Clarence. |

| 1412* | Sept. 23,* | He came again with "a huge people." |

| 1413 | Feb. 3, | Parliament opened. |

| 1413 | March 20, | Henry IV. died. |

| 1413 | April 9, | HENRY V. CROWNED. |

| 1413 | May 15, | Parliament at Westminster. |

| 1413 | June 26, | Convocation of the Clergy. |

| 1413 | Lord Cobham cited. | |

| 1413 | Lord Cobham escaped from the Tower. | |

| 1414 | Jan. 10, | Affair of St. Giles' Field. |

| 1414 | April 20, | Parliament at Leicester. |

| 1414 | Henry founded Sion and Shene. | |

| 1414 | Council of Constance. (p. xvii) | |

| 1415 | May 4, | The Council of Constance condemned Wickliffe's memory, and commanded the exhumation of his bones. |

| 1415 | July 6, | John Huss condemned. |

| 1415 | July 20, | Conspiracy at Southampton. |

| 1415 | Aug. 11, | Henry sailed for Normandy. |

| 1415 | Sept. 15, | Death of Bishop of Norwich in the camp. |

| 1415 | Sept. 22, | Surrender of Harfleur. |

| 1415 | Clayton and Gurmyn burnt for heresy. | |

| 1415 | Oct. 25, | Battle of Agincourt. |

| 1415 | Nov. 16, | Henry returned to England. |

| 1415 | Nov. 22, | Thanksgiving in London. |

| 1416 | April 29, | Emperor Sigismund visited England. |

| 1416 | May 30, | Jerome of Prague burnt. |

| 1416 | Aug. 15, | League signed by Henry and Sigismund. |

| 1417 | July 23, | Henry's second expedition. |

| 1417 | Sept. 4, | Surrender of Caen. |

| 1417 | Dec. | Execution of Lord Cobham. |

| 1418 | July 1, | Rouen besieged. |

| 1419 | Jan. 19, | Rouen taken. |

| 1419 | May 30, | Henry and Katharine first met. |

| 1419* | July 7, | Henry's letter concerning Oriel College. |

| 1420 | May 30, | Henry and Katharine married. |

| 1420 | July, | Katharine lodged in the camp before Melun. |

| 1420 | Henry and Katharine, with the King and Queen of France, entered Paris. | |

| 1421 | Jan 31, | Henry and Katharine arrived in England. |

| 1421 | Feb 23, | Katharine crowned in Westminster. |

| 1421 | March 23, | They passed their Easter at Leicester. |

| 1421 | Between March & May, | They travelled through the greater part of England. |

| 1421 | March 23, | Death of the Duke of Clarence. |

| 1421 | May 26, | Taylor condemned to imprisonment for heresy. |

| 1421 | June 1, | Henry left London on his third expedition. (p. xviii) |

| 1421 | June 10, | Henry landed at Calais. |

| 1421 | Oct. 6, | Siege of Meaux began, and lasted till the April following. |

| 1421 | Dec. 6, | Henry's son born at Windsor. |

| 1422 | May 21, | Katharine landed at Harfleur. |

| 1422 | Henry met her at the Bois de Vincennes. | |

| 1422 | They entered Paris together. | |

| 1422 | Aug. | Henry left Katharine at Senlis. |

| 1422 | Aug. 31, | Death of Henry. |

| 1423 | March 1, | William Taylor burnt for heresy. |

No. 1. Owyn Glyndowr

2. Lydgate

3. Occleve

Henry the Fifth was the son of Henry of Bolinbroke and Mary daughter of Humfrey Bohun, Earl of Hereford. No direct and positive evidence has yet been discovered to fix with unerring accuracy the day or the place of his birth. If however we assume the statement of the chroniclers[2] to be true, that he was born at Monmouth on the ninth day of August in the year 1387,[3] history supplies many ascertained (p. 002) facts not only consistent with that hypothesis, but in confirmation of it; whilst none are found to throw upon it the faintest shade of improbability. At first sight it might perhaps appear strange that the exact time of the birth as well of Henry of Monmouth, as of his father, two successive kings of England, should even yet remain the subject of conjecture, tradition, and inference; whilst the day and place of the birth of Henry VI. is matter of historical record. A single reflection, however, on the circumstances of their respective births, renders the absence of all precise testimony in the one case natural; whilst it would have been altogether unintelligible in the other. When Henry of Bolinbroke and Henry of Monmouth were born, their fathers were subjects, and nothing of national interest was at the time associated with their appearance in the world; at Henry of Windsor's birth he was the acknowledged heir to the throne both of England and of France.

To what extent Henry of Monmouth's future character and conduct were, under Providence, affected by the circumstances of his family and its several members, it would perhaps be less philosophical than presumptuous to define. But, that those (p. 003) circumstances were peculiarly calculated to influence him in his principles and views and actions, will be acknowledged by every one who becomes acquainted with them, and who is at the same time in the least degree conversant with the growth and workings of the human mind. It must, therefore, fall within the province of the inquiry instituted in these pages, to take a brief review of the domestic history of Henry's family through the years of his childhood and early youth.

John, surnamed "of Gaunt," from Ghent or Gand in Flanders, the place of his birth, was the fourth son of King Edward the Third. At a very early age he married Blanche, daughter and heiress of Henry Plantagenet, Duke of Lancaster, great-grandson of Henry the Third.[4] The time of his marriage with Blanche,[5] though recorded with sufficient precision, is indeed comparatively of little consequence; whilst the date of their son Henry's birth, from the influence which the age of a father may have on the destinies of his child, becomes matter of much importance to those who take any interest in (p. 004) the history of their grandson, Henry of Monmouth. On this point it has been already intimated that no conclusive evidence is directly upon record. The principal facts, however, which enable us to draw an inference of high probability, are associated with so pleasing and so exemplary a custom, though now indeed fallen into great desuetude among us, that to review them compensates for any disappointment which might be felt from the want of absolute certainty in the issue of our research. It was Henry of Bolinbroke's custom[6] every year on the Feast of the Lord's Supper, that is, on the Thursday before Easter, to clothe as many poor persons as equalled the number of years which he had completed on the preceding birthday; and by examining the accounts still preserved in the archives of the Duchy of Lancaster, the details of which would be altogether uninteresting in this place, we are led to infer that Henry Bolinbroke was born on the 4th of April 1366. Blanche, his mother, survived the birth of Bolinbroke probably not more than three years. Whether this lady found in John of Gaunt a faithful and loving husband, or whether his libertinism caused her to pass her short life in disappointment and sorrow, no authentic document enables us to pronounce. It is, however, impossible to close our eyes against the (p. 005) painful fact, that Catherine Swynford, who was the partner of his guilt during the life of his second wife, Constance, had been an inmate of his family, as the confidential attendant on his wife Blanche, and the governess of her daughters, Philippa and Elizabeth of Lancaster. That he afterwards, by a life of abandoned profligacy, disgraced the religion which he professed, is, unhappily, put beyond conjecture or vague rumour. Though we cannot infer from any expenses about her funeral and her memory, that Blanche was the sole object of his affections, (the most lavish costliness at the tomb of the departed too often being only in proportion to the unkindness shown to the living,) yet it may be worth observing, that in 1372 we find an entry in the account, of 20l. paid to two chaplains (together with the expenses of the altar) to say masses for her soul. He was then already[7] married to his second wife, Constance, daughter of Peter the Cruel, King of Castile. By this lady, whom he often calls "the Queen," he appears to have had only one child, married, it is said, to Henry III. King of Castile.[8] Constance, the mother, is represented to (p. 006) have been one of the most amiable and exemplary persons of the age, "above other women innocent and devout;" and from her husband she deserved treatment far different from what it was her unhappy lot to experience. But however severe were her sufferings, she probably concealed them within her own breast: and she neither left her husband nor abandoned her duties in disgust. It is indeed possible, though in the highest degree improbable, that whilst his unprincipled conduct was too notorious to be concealed from others, she was not herself made fully acquainted with his infidelity towards her. At all events we may indulge in the belief that she proved to her husband's only legitimate son, (p. 007) Henry of Bolinbroke, a kind and watchful mother.

At that period of our history, persons married at a much earlier age than is usually the case among us now; and the espousals of young people often preceded for some years the period of quitting their parents' home, and living together, as man and wife. In the year 1381 Henry, at that time only fifteen years of age, was espoused[9] to his future wife, Mary Bohun, (p. 008) daughter of the Earl of Hereford, who had then not reached her twelfth year. These espousals were in those days accompanied by the religious service of matrimony, and the bride assumed the title of her espoused husband.[10]

We shall probably not be in error, if we fix the period of the Countess of Derby leaving her mother's for her husband's roof somewhere in the year 1386, when he was twenty, and she sixteen years old; and we are not without reason for believing that they made Monmouth Castle their home.

Some modern writers affirm that this was the favourite residence of John of Gaunt's family: but it is very questionable whether from having themselves experienced the beauty and loveliness of the spot, they (p. 009) have not been unconsciously tempted to venture this assertion without historical evidence. Monmouth is indeed situated in one of the fairest and loveliest valleys within the four seas of Britain. Near its centre, on a rising ground between the river Monnow (from which the town derives its name) and the Wye and not far from their confluence, the ruins of the Castle are still visible. The poet Gray looked over it from the side of the Kymin Hill, when he described the scene before him as "the delight of his eyes, and the very seat of pleasure." With his testimony, unbiassed as it was by local attachment, it would be unwise to mingle the feelings of affection entertained by one whose earliest associations, "redolent of joy and youth," can scarcely rescue his judgment from the suspicion of partiality. At that time John of Gaunt's estates and princely mansions studded, at various distances, the whole land of England from its northern border to the southern coast. And whether he allowed Henry of Bolinbroke to select for himself from the ample pages of his rent-roll the spot to which he would take his bride, or whether he assigned it of his own choice to his son as the fairest of his possessions; or whether any other cause determined the place of Henry the Fifth's birth, we have no reasonable ground for doubting that he was born in the Castle of Monmouth, on the 9th of August 1387.

Of Monmouth Castle, the dwindling ruins are now very scanty, and in point of architecture present nothing (p. 010) worthy of an antiquary's research. They are washed by the streams of the Monnow, and are embosomed in gardens and orchards, clothing the knoll on which they stand; the aspect of the southern walls, and the rocky character of the soil admirably adapting them for the growth of the vine, and the ripening of its fruits. In the memory of some old inhabitants, who were not gathered to their fathers when the Author could first take an interest in such things, and who often amused his childhood with tales of former days, the remains of the Hall of Justice were still traceable within the narrowed pile; and the crumbling bench on which the Justices of the Circuit once sate, was often usurped by the boys in their mock trials of judge and jury. Somewhat more than half a century ago, a gentleman whose garden reached to one of the last remaining towers, had reason to be thankful for a marked interposition in his behalf of the protecting hand of Providence. He was enjoying himself on a summer's evening in an alcove built under the shelter and shade of the castle, when a gust of wind blew out the candle by his side, just at the time when he felt disposed to replenish and rekindle his pipe. He went consequently with the lantern in his hand towards his house, intending to renew his evening's recreation; but he had scarcely reached the door when the wall fell, burying his retreat, and the entire slope, with its shrubs and flowers and fruits, under one mass of ruin.

From (p. 011) this castle, tradition says, that being a sickly child, Henry was taken to Courtfield, at the distance of six or seven miles from Monmouth, to be nursed there. That tradition is doubtless very ancient; and the cradle itself in which Henry is said to have been rocked, was shown there till within these few years, when it was sold, and taken from the house. It has since changed hands, if it be any longer in existence. The local traditions, indeed, in the neighbourhood of Courtfield and Goodrich are almost universally mingled with the very natural mistake that, when Henry of Monmouth was born, his father was king; and so far a shade of improbability may be supposed to invest them all alike; yet the variety of them in that one district, and the total absence of any stories relative to the same event on every other side of Monmouth, should seem to countenance a belief that some real foundation existed for the broad and general features of these traditionary tales. Thus, though the account acquiesced in by some writers, that the Marchioness of Salisbury was Henry of Monmouth's nurse at Courtfield, may have originated in an officious anxiety to supply an infant prince with a nurse suitable to his royal birth; still, probably, that appendage would not have been annexed to a story utterly without foundation, and consequently throws no incredibility on the fact that the eldest son of the young Earl of Derby was nursed at Courtfield. Thus, too, though the recorded salutation of the ferryman (p. 012) of Goodrich congratulates his Majesty on the birth of a noble prince, as the King was hastening from his court and palace of Windsor to his castle of Monmouth; yet the unstationary habits of Bolingbroke, his love of journeyings and travels, and his restlessness at home, render it very probable that he was absent from Monmouth even when the hour of perilous anxiety was approaching; and thus on his return homeward (perhaps too from Richard's court at Windsor) the first tidings of the safety of his Countess and the birth of the young lord may have saluted him as he crossed the Wye at Goodrich Ferry. So again in the little village of Cruse, lying between the church and the castle of Goodrich, the cottagers still tell, from father to son, as they have told for centuries over their winter's hearth, how the herald, hurrying from Monmouth to Goodrich fast as whip and spur could urge his steed onward, with the tidings of the Prince of Wales' birth, fell headlong, (the horse dropping under him in the short, steep, and rugged lane leading to the ravine, beyond which the castle stands,) and was killed on the spot. No doubt the idea of its being the news of a prince's birth, that was thus posted on, has added, in the imagination of the villagers, to the horse's fleetness and the breathless impetuosity of the messenger; but it is very probable that the news of the young lord's birth, heir to the dukedom of Lancaster, should have been hastened from the castle of Monmouth to Goodrich; and (p. 013) there is no solid reason for discrediting the story.

Still, beyond tradition, there is no evidence at all to fix the young lord either at Courtfield, or indeed at Monmouth, for any period subsequently to his birth. On the contrary, several items of expense in the "Wardrobe account of Henry, Earl of Derby," would induce us to infer either that the tradition is unfounded, or that at the utmost the infant lord was nursed at Courtfield only for a few months. In that account[11] we find an entry of a charge for a "long gown" for the young lord Henry; and also the payment of 2l. to a midwife for her attendance on the Countess during her confinement at the birth of the young lord Thomas, the gift of the Earl, "at London." By this document it is proved that Henry's younger brother, the future Duke of Clarence, was born before October 1388, and that some time in the preceding year Henry was himself still in the long robes of an infant; and that the family had removed from Monmouth to London. In the Wardrobe expenses of the Countess for the same year, we find several items of sums defrayed for the clothes of the young lords Henry and Thomas together, but no allusion whatever to the brothers being separate: one entry,[12] fixing Thomas and his nurse at Kenilworth soon (p. 014) after his birth, leaves no ground for supposing that his elder brother was either at Monmouth or at Courtfield. It may be matter of disappointment and of surprise that Henry's name does not occur in connexion with the place of his birth in any single contemporary document now known. The fact, however, is so. But whilst the place of Henry's nursing is thus left in uncertainty, the name of his nurse—in itself a matter not of the slightest importance—is made known to us not only in the Wardrobe account of his mother, but also by a gratifying circumstance, which bears direct testimony to his own kind and grateful, and considerate and liberal mind. Her name was Johanna Waring; on whom, very shortly after he ascended the throne, he settled an annuity of 20l. "in consideration of good service done to him in former days."[13]

Very few incidents are recorded which can throw light upon Henry's childhood, and for those few we are indebted chiefly to the dry details of account-books. In these many particular items of expense occur relative as well to Henry as to his brothers; which, probably, would differ very little from those of other young noblemen of England at that period of her history. The records of the Duchy of Lancaster provide (p. 015) us with a very scanty supply of such particulars as convey any interesting information on the circumstances and occupations and amusements of Henry of Monmouth. From these records, however, we learn that he was attacked by some complaint, probably both sudden and dangerous, in the spring of 1395; for among the receiver's accounts is found the charge of "6s. 8d. for Thomas Pye, and a horse hired at London, March 18th, to carry him to Leicester with all speed, on account of the illness of the young lord Henry." In the year 1397, when he was just ten years old, a few entries occur, somewhat interesting, as intimations of his boyish pursuits. Such are the charge of "8d. paid by the hands of Adam Garston for harpstrings purchased for the harp of the young lord Henry," and "12d. to Stephen Furbour for a new scabbard of a sword for young lord Henry," and "1s. 6d. for three-fourths of an ounce of tissue of black silk bought at London of Margaret Stranson for a sword of young lord Henry." Whilst we cannot but be sometimes amused by the minuteness with which the expenditure of the smallest sum in so large an establishment as John of Gaunt's is detailed, these little incidents prepare us for the statement given of Henry's early youth by the chroniclers,—that he was fond both of minstrelsy and of military exercises.

The same dry pages, however, assure us that his more severe studies were not neglected. In the accounts for the year ending February 1396, we find (p. 016) a charge of "4s. for seven books of Grammar contained in one volume, and bought at London for the young Lord Henry." The receiver-general's record informs us of the name of the lord Humfrey's tutor;[14] but who was appointed to instruct the young lord Henry does not appear; nor can we tell how soon he was put under the guidance of Henry Beaufort. If, as we have reason to believe, he had that celebrated man as his instructor, or at least the superintendent of his studies, in Oxford so early as 1399, we may not, perhaps, be mistaken in conjecturing, that even this volume of Grammar was first learned under the direction of the future Cardinal.

Scanty as are the materials from which we must weave our opinion with regard to the first years of Henry of Monmouth, they are sufficient to suggest many reflections upon the advantages as well as the unfavourable circumstances which attended him: We must first, however, revert to a few more particulars relative to his family and its chief members.

His father, who was then about twenty-four years of age, certainly left England[15] between the 6th of May (p. 017) 1390 and the 30th of April 1391, and proceeded to Barbary. During his absence his Countess was delivered of Humfrey, his fourth son. Between the summers of 1392 and 1393 he undertook a journey to Prussia, and to the Holy Sepulchre.

The next year visited Henry with one of the most severe losses which can befall a youth of his age. His mother,[16] then only twenty-four years old, having given birth to four sons and two daughters, was taken away from the anxious cares and comforts of her earthly career, in the very prime of life.[17] Nor was this the only bereavement which befell the family at this time. Constance, the second wife of John of Gaunt, a lady to whose religious and moral worth the strongest and warmest testimony is borne by the chroniclers of the time; and who might (had it so pleased the Disposer of all things) have watched (p. 018) over the education of her husband's grandchildren, was also this same year removed from them to her rest: they were both buried at Leicester, then one of the chief residences of the family.

The mind cannot contemplate the case of either of these ladies without feelings of pity rather than of envy. They were both nobly born, and nobly married; and yet the elder was joined to a man, who, to say the very least, shared his love for her with another; and the younger, though requiring, every year of her married state, all the attention and comfort and support of an affectionate husband, yet was more than once left to experience a temporary widowhood. And if we withdraw our thoughts from those of whom this family was then deprived, there is little to lessen our estimate of their loss, when we think of those whom they left behind. Henry's maternal grandmother, indeed, the Countess of Hereford, survived her daughter many years; and we are not without an intimation that she at least interested herself in her grandson's welfare. In his will, dated 1415, he bequeaths to Thomas, Bishop of Durham, "the missal and portiphorium[18] which we had of the gift of our dear grandmother, the Countess of Hereford."[19] We may (p. 019) fairly infer from this circumstance that Henry had at least one near relation both able and willing to guide him in the right way. How far opportunities were afforded her of exercising her maternal feelings towards him, cannot now be ascertained; and with the exception of this noble lady, there is no other to whom we can turn with entire satisfaction, when we contemplate the salutary effects either of precept or example in the case of Henry of Monmouth.

His father indeed was a gallant young knight, often distinguishing himself at justs and tournaments;[20] of an active, ardent and enterprising spirit; nor is any imputation against his moral character found recorded. But we have no ground for believing, that he devoted much of his time and thoughts to the education of his children.

Henry Beaufort, the natural son of John of Gaunt, a person of commanding talent, and of considerable attainments for that age, whilst there is no reason to believe him to have been that abandoned worldling whose eyes finally closed in black despair (p. 020) without a hope of Heaven, yet was not the individual to whose training a Christian parent would willingly intrust the education of his child. And in John of Gaunt[21] himself, little perhaps can be discovered either in principle, or judgment, or conduct, which his grandson could imitate with religious and moral profit. Thus we find Henry of Monmouth in his childhood labouring under many disadvantages. Still our knowledge of the domestic arrangements and private circumstances of his family is confessedly very limited; and it would be unwise to conclude that there were no mitigating causes in operation, nor any advantages to put as a counterpoise into the opposite scale. He may have been under the guidance and tuition of a good Christian (p. 021) and well-informed man; he may have been surrounded by companions whose acquaintance would be a blessing. But this is all conjecture; and probably the question is now beyond the reach of any satisfactory solution.

With regard to the next step also in young Henry's progress towards manhood, we equally depend upon tradition for the views which we may be induced to take: still it is a tradition in which we shall probably acquiesce without great danger of error. He is said to have been sent to Oxford, and to have studied in "The Queen's College" under the tuition of Henry Beaufort, his paternal uncle, then Chancellor of the University. No document is known to exist among the archives of the College or of the University, which can throw any light on this point; except that the fact has been established of Henry Beaufort having been admitted a member of Queen's College, and of his having been chancellor of the university only for the year 1398.

This extraordinary man was consecrated Bishop of Lincoln, July 14, 1398, as appears by the Episcopal Register of that See; after which he did not reside in Oxford. If therefore Henry of Monmouth studied under him in that university, it must have been through the spring and summer of that year, the eleventh of his age. And on this we may rely as the most probable fact. Certainly in the old buildings of Queen's College, a chamber used to be pointed out by successive generations as Henry the Fifth's. (p. 022) It stood over the gateway opposite to St. Edmund's Hall. A portrait of him in painted glass, commemorative of the circumstance, was seen in the window, with an inscription (as it should seem of comparatively recent date) in Latin:

To record the fact for ever.

The Emperor of Britain,

The Triumphant Lord of France,

The Conqueror of his enemies and of himself,

Henry V.

Of this little chamber,

Once the great Inhabitant.[22]

It may be observed that in the tender age of Henry involved in this supposition, there is nothing in the least calculated to throw a shade of improbability on this uniform tradition. Many in those days became members of the university at the time of life when they would now be sent to school.[23] And possibly we shall be most right in supposing that Henry (though perhaps without himself being enrolled among the regular academics) lived with his uncle, then chancellor, and studied under his superintendence. There is nothing on record (hitherto (p. 023) discovered) in the slightest degree inconsistent with this view; whereas if we were inclined to adopt the representation of some (on what authority it does not appear) that Henry was sent to Oxford soon after his father ascended the throne, many and serious difficulties would present themselves. In the first place his uncle, who was legitimated only the year before, was prematurely made Bishop of Lincoln by the Pope, through the interest of John of Gaunt, in the year 1398, and never resided in Oxford afterwards. How old he was at his consecration, has not yet been satisfactorily established; conjecture would lead us to regard him as a few years only (perhaps ten or twelve) older than his nephew. Otterbourne tells us that he was made Bishop[24] when yet a boy.

In the next place we can scarcely discover six months in Henry's life after his uncle's consecration, through which we can with equal probability suppose him to have passed his time in Oxford. It is next to certain that before the following October term, he had been removed into King Richard's palace, carefully watched (as we shall see hereafter); whilst in the spring of the following year, 1399, he was unquestionably obliged to accompany that monarch in his expedition to Ireland. Shortly after his return, in the autumn of that year, on his father's accession to the throne, he was created Prince of Wales; and through the following spring the probability is strong that his father was too anxiously engaged (p. 024) in negotiating a marriage between him and a daughter of the French King, and too deeply interested in providing for him an adequate establishment in the metropolis, to take any measures for improving and cultivating his mind in the university. Independently of which we may be fully assured that had he become a student of the University of Oxford as Prince of Wales, it would not have been left to chance, to deliver his name down to after-ages: the archives of the University would have furnished direct and contemporary evidence of so remarkable a fact; and the College would have with pride enrolled him at the time among its members: as the boy of the Earl of Derby, or the Duke of Hereford, living with his uncle, there is nothing[25] in the omission of his name inconsistent with our hypothesis. At all events, whatever evidence exists of Henry having resided under any circumstances in Oxford, fixes him there under the tuition of the future Cardinal; and that well-known personage is proved not to have resided there subsequently to his appointment to the see[26] of Lincoln, in the summer of 1398.[27]

What (p. 025) were Henry's studies in Oxford, whether, like Ingulphus some centuries before, he drank to his fill of "Aristotle's[28] Philosophy and Cicero's Rhetoric," or whether his mind was chiefly directed to (p. 026) the scholastic theology so prevalent in his day, it were fruitless to inquire. His uncle (as we have already intimated) seems to have been a person of some learning, an excellent man of business, and in the command of a ready eloquence. In establishing his (p. 027) positions before the parliament, we find him not only quoting from the Bible, (often, it must be acknowledged, without any strict propriety of application,) but also citing facts from ancient Grecian history. We may, however, safely conclude that the Chancellor of Oxford confined himself to the general superintendence of his nephew's education, intrusting the details to others more competent to instruct him in the various branches of literature. It is very probable that to some arrangement of that kind Henry was indebted for his acquaintance with such excellent men as his friends John Carpenter of Oriel, and Thomas Rodman, or Rodburn, of Merton.[29]

But whatever course of study was chalked out for him, (p. 028) and through however long or short a period before the summer of 1398, or under what guides soever he pursued it, it is impossible to read his letters, and reflect on what is authentically recorded of him, without being involuntarily impressed by an assurance that he had imbibed a very considerable knowledge of Holy Scripture, even beyond the young men of his day. His conduct also in after-life would prepare us for the testimony borne to him by chroniclers, that "he held in great veneration such as surpassed in learning and virtue." Still, whilst we regret that history throws no fuller light on the early days of Henry of Monmouth, we cannot but hope that in the hidden treasures of manuscripts hereafter to be again brought into the light of day, much may be yet ascertained on satisfactory evidence; and we must leave the subject to those more favoured times.[30]

But whilst doubts may still be thought to hang over the exact time and the duration of Henry's academical (p. 029) pursuits, it is matter of historical certainty, that an event took place in the autumn of 1398, which turned the whole stream of his life into an entirely new channel, and led him by a very brief course to the inheritance of the throne of England. His father, hitherto known as the Earl of Derby, was created Duke of Hereford by King Richard II. Very shortly after his creation, he stated openly in parliament[31] that the Duke of Norfolk, whilst they were riding together between Brentford and London, had assured him of the King's intention to get rid of them both, and also of the Duke of Lancaster with other noblemen, of whose designs against his throne or person he was apprehensive. The Duke of Norfolk denied the charge, and a trial of battle was appointed to decide the merits of the question. The King, doubting probably the effect on himself of the issue of that wager of battle, postponed the day from time to time. At length he fixed finally upon the 16th of September, and summoned the two noblemen to redeem their pledges at Coventry. Very splendid preparations had been made for the struggle; and the whole kingdom shewed the most anxious interest in the result. On the day appointed, the Lord High Constable and the Lord High Marshal of England, with a very great company, and splendidly arrayed, first entered the lists. About the hour of prime the Duke of Hereford appeared at the barriers on a white courser, (p. 030) barbed with blue and green velvet, sumptuously embroidered with swans and antelopes[32] of goldsmith's work,[33] and armed at all points. The King himself soon after entered with great pomp, attended by the peers of the realm, and above ten thousand men in arms to prevent any tumult. The Duke of Norfolk then came on a steed "barbed with crimson velvet embroidered with mulberry-trees and lions of silver." At the proclamation of the herald, Hereford sprang upon his horse, and advanced six or seven paces to meet his adversary. The king upon this suddenly threw down his warder, and commanded the spears to be taken from the combatants, and that they should resume their chairs of state. He then ordered proclamation to be made that the Duke of Hereford had honourably[34] fulfilled his duty; and yet, without assigning any reason, he immediately sentenced him to be banished for ten years: at the same time he condemned the Duke of Norfolk to perpetual exile, adding also the confiscation of his property, except only one thousand pounds by the year. This act of tyranny towards (p. 031) Bolinbroke,[35] contrary, as the chroniclers say, to the known laws and customs of the realm, as well as to the principles of common justice, led by direct consequence to the subversion of Richard's throne, and probably to his premature death.

Whilst however the people sympathized with the Duke of Hereford, and reproached the King for his rashness, as impolitic as it was iniquitous, they seemed to view in the sentence of the Duke of Norfolk, the visitation of divine justice avenging on his head the cruel murder of the Duke of Gloucester. It was remarked (says Walsingham) that the sentence was passed on him by Richard on the very same day of the year on which, only one twelvemonth before, he had caused that unhappy prince to be suffocated in Calais.

(p. 032)The first years of Henry of Monmouth fall, in part at least, as we have seen, within the province of conjecture rather than of authentic history: and the facts for reasonable conjecture to work upon are much more scanty with regard to this royal child, than we find to be the case with many persons far less renowned, and still further removed from our day. But from the date of his father's banishment, very few months in any one year elapse without supplying some clue, which enables us to trace him step by step through the whole career of his eventful life, to the very last day and hour of his mortal existence.

His father's exile dates from October 13, 1398, when Henry had just concluded his eleventh year. Whether (p. 033) up to that time he had been living chiefly in his father's house, or with his grandfather John of Gaunt, or with his maternal grandmother, or with his uncle Henry Beaufort either at Oxford or elsewhere, we have no positive evidence. John of Gaunt did not die till the 3rd of the following February, and he would, doubtless, have taken his grandson under his especial care, at all events on his father's banishment, probably assigning Henry Beaufort to be his tutor and governor. But when Richard sentenced Henry of Bolinbroke, he was too sensible of his own injustice, and too much alive, in this instance at least, to his own danger, to suffer Henry of Monmouth to remain at large. One of the most ancient, and most widely adopted principles of tyranny, pronounces the man "to be a fool, who when he makes away with a father, leaves the son in power to avenge his parent's wrongs." Accordingly Richard took immediate possession of the persons both of the son of the murdered Duke of Gloucester, and of Henry of Monmouth, of whose relatives, as the chroniclers say, he had reason to be especially afraid.

John of Gaunt, we may conclude, now disabled as he was, by those infirmities[36] which hastened him to the grave[37] more rapidly than the mere progress of (p. 034) calm decay, could exert no effectual means either of sheltering his son from the unjust tyrant who sentenced him to ten years banishment from his native land, or of rescuing his grandson from the close custody of the same oppressor. Still the very name of that renowned duke must have put some restraint upon his royal nephew. The lion had yet life, and might put forth one dying effort, if the oppression were carried past his endurance; and it might have been thought well to let him linger and slumber on, till nature should have struggled with him finally. We find, consequently, that though before Bolinbroke's departure from England Richard had remitted four years of his banishment, as a sort of peace-offering perhaps to John of Gaunt, no sooner was that formidable person dead, than Richard, throwing off all semblance of moderation, exiled Bolinbroke for life, and seized and confiscated his property.[38]

Though (p. 035) Richard behaved towards Bolinbroke with such reckless injustice, he does not appear to have been forgetful of his wants during his exile. Within two months of the date of his banishment the Pell Rolls record payment (14 November 1398) "of a thousand marks to the Duke of Hereford, of the King's gift, for the aid and support of himself, and the supply of his wants, on his retirement from England to parts beyond the seas assigned for his sojourn." And on the 20th of the following June payment is recorded of "1586l. 13s. 4d. part of the 2000l. which the king had granted to him, to be advanced annually at the usual times." But this was a poor compensation for the honours and princely possessions of the Dukedom of Lancaster, and the comforts of his home. No wonder if he were often found, as historians tell, in deep depression of spirits, whilst he thought of "his four brave boys, and two lovely daughters," now doubly orphans.

The plan of this work does not admit of any detailed enumeration of the exactions, nor of any minute inquiry into the violence and reckless tyranny of Richard. It cannot be doubted that a long series of oppressive measures at this time alienated the affections of many of his subjects, and exposed (p. 036) his person and his throne to the attacks of proud and powerful, as well as injured and insulted enemies. His conduct appears to evince little short of infatuation. He was determined to act the part of a tyrant with a high hand, and he defied the consequences of his rashness. He had stopped his ears to sounds which must have warned him of dangers setting thick around him from every side; and he had wilfully closed his eyes, and refused to look towards the precipice whither he was every day hastening.[39] He rushed on, despising the danger, till he fell once, and for ever. The murder of the Duke of Gloucester, involving on the part of the king one of the most base and cold-hearted pieces of treachery ever recorded of any ruthless tyrant, had filled the whole realm with indignation; and chroniclers do not hesitate to affirm that Richard would have been then deposed and destroyed, had it not been for the interposition of John of Gaunt; and now the eldest son of that very man, who alone had sheltered him from his people's vengeance, Richard banishes for ever without cause, confiscating his princely estates, and pursuing him with bitter and insulting vengeance even in his exile.

If (p. 037) his own reason had not warned him beforehand against such self-destroying acts of iniquity and violence, yet the signs of the popular feeling which followed them, would have recalled any but an infatuated man to a sense of the danger into which he was plunging. When Henry of Bolinbroke left London for his exile, forty thousand persons are said to have been in the streets lamenting his fate; and the mayor, accompanied by a large body of the higher class of citizens, attended him on his way as far as Dartford; and some never left him till they saw him embark at Dover.[40] But to all these clear and strong indications of the tone and temper of his subjects, Richard was obstinately blind and deaf. If he heard and saw them, he hardened himself against the only practical influence which they were calculated to produce. Setting the approaching political storm, and every moral peril, at defiance, he quitted England just as though he were leaving behind him contented and devoted subjects.

Having assigned Wallingford Castle for the residence of his Queen Isabel, he departed for Ireland about the 18th of May; but did not set sail from Milford Haven till the 29th; he reached Waterford on the last day of the month. Though Richard[41] was (p. 038) prompted solely by reasons of policy and by a regard to his own safety to take with him to Ireland Henry of Monmouth, (together with Humphrey, son of the murdered Duke of Gloucester,) we should do him great injustice were we to suppose that he treated him as an enemy.[42] On the contrary, we have reason to believe that he behaved towards him with great kindness and respect.[43]

About midsummer the king advanced towards the country and strong-holds of Macmore, his most formidable antagonist. On the opening of that campaign he conferred upon young Henry the order of knighthood;[44] and wishing to signalize this mark of the royal favour with unusual celebrity, he conferred on that day the same distinction (expressly (p. 039) in honour of Henry) upon ten others his companions in arms. The particulars of this transaction, and the details of the entire campaign against the Wild Irish, as they were called, are recorded in a metrical history by a Frenchman named Creton, who was an eye-witness of the whole affair. This gentleman had accepted the invitation of a countryman of his own, a knight, to accompany him to England. On their arrival in London they found the king himself in the very act of starting for Ireland, and thither they went in his company as amateurs.

This writer thus describes[45] the courteous act and pledge of friendship bestowed by Richard on his youthful companion and prisoner, recording, with some interesting circumstances, the very words of knightly and royal admonition with which the distinguished honour was conferred. "Early on a summer's morning, the vigil of St. John, the King marched directly to Macmore[46], who would neither submit, (p. 040) nor obey him in any way, but affirmed that he was himself the rightful king of Ireland, and that he would never cease from war and the defence of his country till death. Then the King prepared to go into the depths of the deserts in search of him. For his abode is in the woods, where he is accustomed to dwell at all seasons; and he had with him, according to report, 3000 hardy men. Wilder people I never saw; they did not appear to be much dismayed at the English. The whole host were assembled at the entrance of the deep woods; and every one put himself right well in his array: for it was thought for the time that we should have battle; but I know that the Irish did not show themselves on this occasion. Orders were then given by the King that every thing around should be set fire to. Many a village and house were then consumed. While this was going on, the King, who bears leopards in his arms, caused a space to be cleared on all sides, and pennon and standards to be quickly hoisted. Afterwards, out of true and entire affection, he sent for the son of the Duke of Lancaster, a fair young and handsome bachelor,[47] and knighted him, saying, 'My fair cousin, henceforth be gallant and bold, for, unless you conquer, you will have little name for valour.' And for his greater honour and satisfaction, to the end that it might be better imprinted on his memory, he (p. 041) made eight or ten other knights; but indeed I do not know what their names were, for I took little heed about the matter, seeing that melancholy, uneasiness and care had formed, and altogether chosen my heart for their abode, and anxiety had dispossessed me of joy."

The English suffered much from hunger and fatigue during this expedition in search of the archrebel, and after many fruitless attempts to reduce him, reached Dublin, where all their sufferings were forgotten in the plenty and pleasures of that "good city."

The day on which Richard conferred upon Henry so distinguished a mark of his regard and friendship, offering the first occasion on which any reference is made to his personal appearance and bodily constitution, the present may, perhaps, be deemed an appropriate place for recording what we may have been able to glean in that department of biographical memoir with which few, probably, are inclined to dispense.

M. Creton, in his account of this memorable knighthood, represents Henry as "a handsome young bachelor," then in his twelfth year; and very little further, of a specific character, is recorded by his immediate contemporaries. The chroniclers next in succession describe him as a man of "a spare make, tall, and well-proportioned," "exceeding," says Stow, "the ordinary stature (p. 042) of men;" beautiful of visage, his bones small: nevertheless he was of marvellous strength, pliant and passing swift of limb; and so trained was he to feats of agility by discipline and exercise, that with one or two of his lords he could, on foot, readily give chase to a deer without hounds, bow, or sling, and catch the fleetest of the herd. By the period of his early youth he must have outgrown the weakness and sickliness of his childhood, or he could never have endured the fatigues of body and mind to which he was exposed through his almost incessant campaigns from his fourteenth to his twentieth year. These hardships, nevertheless, may have been all the while sowing the seeds of that fatal disease which at the last carried him so prematurely from the labours, and vexations, and honours of this world.[48]

With regard to his habits of social intercourse, his powers of conversation, the disposition and bent of (p. 043) his mind when he mingled with others, whether in the seasons of public business, or the more private hours of retirement and relaxation, (whilst the never-ending tales of his dissipation among his unthrifty reckless playmates are reserved for a separate inquiry,) a few words only will suffice in this place. In addition to the testimony of later authors, the records of contemporaneous antiquity, sometimes by direct allusion to him, sometimes incidentally and as it were undesignedly, lead us to infer that he was a distinguished example of affability and courteousness; still not usually a man of many words; clear in his own conception of the subject of conversation or debate, and ready in conveying it to others, yet peculiarly modest and unassuming in maintaining his opinion, listening with so natural an ease and deference, and kindness to the sentiments and remarks and arguments of others, as to draw into a close and warm personal attachment to himself those who had the happiness to be on terms of familiarity with him. Certainly the unanimous voice of Parliament ascribed to him, when engaged in the deeper and graver discussions involving the interests and welfare of the state, qualities corresponding in every particular with these representations of individual chroniclers. The glowing, living language of Shakspeare seems only to have recommended by becoming and graceful ornament, what had its existence really and substantially in truth.

Hear

(p. 044)

him but reason in divinity,

And, all-admiring, with an inward wish

You would desire the King were made a prelate:

Hear him debate of commonwealth affairs,

You would say, it hath been all-in-all his study:

List his discourse in war, and you shall hear

A fearful battle render'd you in music:

Turn him to any cause of policy,

The Gordian knot of it he will unloose,

Familiar as his garter; that, when he speaks,

The air, a charter'd libertine, is still,

And the mute wonder lurketh in men's ears,

To steal his sweet and honey'd sentences.

Soon after Richard reached Dublin, the Duke of Albemarle, Constable of England, arrived with a large fleet, and with forces all ready for a campaign: but he came too late for any good purpose, and better had it been for Richard had he never come at all. His advice was the king's ruin. Richard with his army passed full six weeks in Dublin, in the free enjoyment of ease and pleasure, altogether ignorant of the terrible reverse which awaited him. In consequence of the uninterrupted prevalence of adverse winds, his self-indulgence was undisturbed by the news which the first change of weather was destined to bring. Through the whole of this momentous crisis the weather was so boisterous that no vessel dared to brave the tempest. On the return of a quiet sea, a barge arrived at Dublin upon a Saturday, laden with the appalling tidings that Henry, Duke of Lancaster, had returned from exile (p. 045) and was carrying all before him; supported by Richard's most powerful subjects, now in open rebellion against his authority; and encouraged by the Archbishop, who in the Pope's name preached plenary absolution and a place in paradise to all who would assist the duke to recover his just rights from his unjust sovereign. The King grew pale at this news, and instantly resolved to return to England on the Monday following. But the Duke of Albemarle advised that unhappy monarch, fatally for his interests, to remain in Ireland till his whole navy could be gathered; and in the mean time[49] to send over the Earl of Salisbury. That nobleman departed forthwith, (Richard solemnly promising to put to sea in six days,) and landed at Conway, "the strongest and fairest town in Wales."

Either before the Earl of Salisbury's departure, or as is the more probable, towards the last of those eighteen (p. 046) days through which afterwards, to the ruin of his cause, Richard wasted his time (the only time left him) in Ireland, he sent for Henry of Monmouth, and upbraided him with his father's treason. Otterbourne minutely records the conversation which is said then to have passed between them. "Henry, my child," said the King, "see what your father has done to me. He has actually invaded my land as an enemy, and, as if in regular warfare, has taken captive and put to death my liege subjects without mercy and pity. Indeed, child, for you individually I am very sorry, because for this unhappy proceeding of your father you must perhaps be deprived of your inheritance." 'To whom Henry, though a boy, replied in no boyish manner,' "In truth, my gracious king and lord, I am sincerely grieved by these tidings; and, as I conceive, you are fully assured of my innocence in this proceeding of my father."—"I know," replied the King, "that the crime which your father has perpetrated does not attach at all to you; and therefore I hold you excused of it altogether."

Soon after this interview the unfortunate Richard set off from Dublin to return to his kingdom, which was now passing rapidly into other hands: but his two youthful captives, Henry of Monmouth, and Humfrey, son of the late Duke of Gloucester, he caused to be shut up in the safe keeping of the castle of Trym.[50] From that day, which must have been (p. 047) somewhere about the 20th of August, till the following October,[51] when he was created Prince of Wales in a full assembly of the nobles and commons of England, we have no direct mention made of Henry of Monmouth. That much of the intervening time was a season of doubt and anxiety and distress to him, we have every reason to believe. Though he had been previously detained as a hostage, yet he had been treated with great kindness; and Richard, probably inspiring him with feelings of confidence and attachment towards himself, had led him to forget his father's enemy and oppressor in his own personal benefactor and friend. Richard had now left him and his cousin (a youth doubly related to him) as prisoners in a solitary castle far from their friends, and in the custody of men at whose hands they could not anticipate what treatment they might receive. How long they remained in this state of close and, as they might well deem it, perilous confinement, we do not learn. Probably the Duke of Lancaster, on hearing of Richard's departure from Dublin, sent off immediately to release the two captive youths; or at the latest, as soon as he had the unhappy king within his power. On the one (p. 048) hand it may be argued that had Henry of Monmouth joined his father before the cavalcade reached London, so remarkable a circumstance would have been noticed by the French author, who accompanied them the whole way. On the other hand we learn from the Pell Rolls that a ship was sent from Chester to conduct him to London, though the payment of a debt does not fix the date at which it was incurred.[52] We may be assured no time was lost by the Duke, by those whom he employed, or by his son; at all events that Henry was restored to his father at Chester (a circumstance which would be implied had Richard there been consigned to the custody of young Humphrey), is not at all in evidence. The far more reasonable inference from what is recorded is, that Humphrey, his young fellow-prisoner and companion, and near relative and friend, was snatched from him by sudden death at the very time when Providence seemed to have opened to him a joyous return to liberty and to his widowed mother. There is no reason to doubt that the news of Richard's captivity, and the Duke of Lancaster's success, reached the two friends whilst prisoners in Trym Castle; nor that they were both released, (p. 049) and embarked together for England. Where they were when the hand of death separated them is not certainly known. The general tradition is, that poor Humphrey had no sooner left the Irish coast than he was seized by a fever, or by the plague, which carried him off before the ship could reach England. But whether he landed or not, whether he had joined the Duke or not before the fatal malady attacked him, there is no doubt that his death followed hard upon his release. His mother, the widowed duchess of his murdered father, who had moreover never been allowed the solace of her child's company, now bereft of husband and son, could bear up against her affliction no longer. On hearing of her desolate state, excessive grief overwhelmed her; and she fell sick and died.[53]

It is impossible to contemplate these two youthful relatives setting out from the prison doors full of joy, and happy auguries, and mutual congratulations, in health and spirits, panting for their dearest friends,—one going to a princedom, and a throne, and a brilliant career of victories, the other to disease and death,—without being impressed with the wonderful acts of an inscrutable Providence, with (p. 050) the ignorance and weakness of man, and with the resistless will of the merciful Ruler of man's destinies. Even had young Humphrey foreseen his dissolution, then so nigh at hand, as the gates of Trym Castle opened for their release, he might well have addressed his companion in words once used by the prince of Grecian philosophers at the close of his defence before the court who condemned him. "And now we are going, I indeed to death, you to life; to which of the two is the better fate assigned is known only to God!"[54]

Since this page was first written, the Author has been led to examine the Pell Rolls;[55] and he is induced to confess that, independently of the full confirmation afforded by those original documents to numberless facts referred to in these Memoirs, many an interesting train of thought is suggested by the inspection of them. The bare and dry entries of one single roll at the period now under consideration, bring with them to his mind associations of a truly affecting, serious, and solemn character. The very last roll of Richard II. by the merest details of expenditure records the payment of sums made by that unhappy monarch to Bolinbroke, then in exile, expatriated by his unjust and wanton decree; to Humphrey, the orphan son (p. 051) of the late murdered Duke of Gloucester; to Henry of Monmouth his cousin, both then in Richard's safe keeping; and to Eleanor, the widowed mother of Humphrey, and maternal aunt of Henry. Can any event paint in deeper and stronger colouring the vicissitudes and reverses of mortality, "the changes and chances" of our life on earth? Before the scribe had filled the next half-year's roll, (now lying with it side by side, and speaking like a monitor from the grave to high and low, rich and poor, prince and peasant alike,)—of those five persons, Richard had lost both his crown and his life; Bolinbroke had mounted the throne from which Richard had fallen; Henry of Monmouth had been created Prince of Wales, and was hailed as heir apparent to that throne; his cousin Humphrey, once the companion of his imprisonment, and the sharer of his anticipations of good or ill, had been carried off from this world by death at the very time of his release; and the broken-hearted Eleanor, (the root and the branch of her happiness now gone for ever,) unable to bear up against her sorrows, had sunk under their weight into her grave![56]

(p. 052)Whether Henry of Monmouth met his father and the cavalcade at Chester, or joined them on their road to London, or followed them thither; whether he witnessed on the way the humiliation and melancholy of his friend, and the triumphant exaltation of his father, or not; every step taken by either of those two chieftains through the eventful weeks which intervened between King Richard making the youth a knight in the wilds of Ireland, and King Henry creating him Prince of Wales in the face of the nation at Westminster, bears immediately upon his destinies. And the whole complicated tissue of circumstances then in progress is so inseparably connected with him both individually and as the future monarch of England, that a brief review of the proceedings as well of the falling (p. 053) as of the rising antagonist seems indispensable in this place.