Project Gutenberg's Ballads of Romance and Chivalry, by Frank Sidgwick

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Ballads of Romance and Chivalry

Popular Ballads of the Olden Times - First Series

Author: Frank Sidgwick

Release Date: January 28, 2007 [EBook #20469]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BALLADS OF ROMANCE AND CHIVALRY ***

Produced by Louise Hope, Paul Murray and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.ne

This e-text uses UTF-8 (Unicode) file encoding. If the quotation marks in this paragraph appear as garbage, you may have an incompatible browser or unavailable fonts. First, make sure that the browser’s “character set” or “file encoding” is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change your browser’s default font.

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They have been marked in the text with mouse-hover popups. Variant forms such as “Maisry” : “Maisery” or “Text(s)” : “The Text” were left unchanged.

All brackets [ ] are in the original.

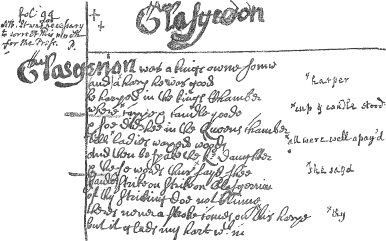

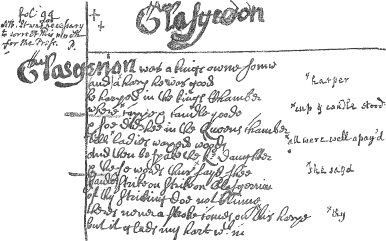

Facsimile of the Percy Folio MS. (British Museum, Addit. MS. 27, 879, f. 46 verso). Glasgerion, first three verses (see p. 2), annotated by Percy. The full page is 15¼ x 6 inches. larger view

|

‘La rime n’est pas riche, et le style en est vieux: Mais ne voyez-vous pas que cela vaut bien mieux Que ces colifichets dont le bon sens murmure, Et que la passion parle là toute pure?’ |

|

Molière, Le Misanthrope, I. 2. |

| PAGE | |

| Preface | ix |

| Introduction | xvii |

| Ballads in the First Series | xliii |

| Glossary of Ballad Commonplaces | xlvi |

| List of Books for Ballad Study | lii |

| Note on the Illustrations | lv |

| Footnotes | |

| GLASGERION | 1 |

| YOUNG BEKIE | 6 |

| OLD ROBIN OF PORTINGALE | 13 |

| LITTLE MUSGRAVE AND LADY BARNARD | 19 |

| THE BONNY BIRDY | 25 |

| FAIR ANNIE | 29 |

| THE CRUEL MOTHER | 35 |

| CHILD WATERS | 37 |

| EARL BRAND | 44 |

| The Douglas Tragedy | 49 |

| The Child of Ell | 52 |

| LORD THOMAS AND FAIR ANNET | 54 |

| THE BROWN GIRL | 60 |

| FAIR MARGARET AND SWEET WILLIAM | 63 |

| LORD LOVEL | 67 |

| LADY MAISRY | 70 |

| viii THE CRUEL BROTHER | 76 |

| THE NUTBROWN MAID | 80 |

| FAIR JANET | 94 |

| BROWN ADAM | 100 |

| WILLIE O’ WINSBURY | 104 |

| THE MARRIAGE OF SIR GAWAINE | 107 |

| THE BOY AND THE MANTLE | 119 |

| JOHNEY SCOT | 128 |

| LORD INGRAM AND CHIEL WYET | 135 |

| THE TWA SISTERS O’ BINNORIE | 141 |

| YOUNG WATERS | 146 |

| BARBARA ALLAN | 150 |

| THE GAY GOSHAWK | 153 |

| BROWN ROBIN | 158 |

| LADY ALICE | 163 |

| CHILD MAURICE | 165 |

| FAUSE FOOTRAGE | 172 |

| FAIR ANNIE OF ROUGH ROYAL | 179 |

| HIND HORN | 185 |

| EDWARD | 189 |

| LORD RANDAL | 193 |

| LAMKIN | 196 |

| FAIR MARY OF WALLINGTON | 201 |

| Index of Titles | 209 |

| Index of First Lines | 211 |

Of making selections of ballads there is no end. As a subject for the editor, they seem to be only less popular than Shakespeare, and every year sees a fresh output. But of late there has sprung up a custom of confusing the old with the new, the genuine with the imitation; and the products of civilised days, ‘ballads’ by courtesy or convention, are set beside the rugged and hard-featured aborigines of the tribe, just as the delicate bust of Clytie in the British Museum has for next neighbour the rude and bold ‘Unknown Barbarian Captive.’ To contrast by such enforced juxtaposition a ballad of the golden world with a ballad by Mr. Kipling is unfair to either, each being excellent in its way; and the collocation of Edward or Lord Randal with a ballad of Rossetti’s is only of interest or value as exhibiting the perennial charm of the refrain.

There exist, however, in our tongue—though x not only in our tongue—narratives in rhyme which have been handed down in oral tradition from father to son for so many ages, that all record of their authorship has long been lost. These are commonly called the Old Ballads. Being traditional, each ballad may exist in more than one form; in most cases the original story is clothed in several different forms. The present series is designed to include all the best of these ballads which are still extant in England and Scotland: Ireland and Wales possess a similar class of popular literature, but each in its own tongue. It is therefore necessary, in issuing this the first volume of the series, to say somewhat as to the methods employed in editing and selecting.

Ballad editors of yore were confronted with perhaps two, perhaps twenty, versions of each ballad; some unintelligibly fragmentary, some intelligibly complete; some in print, some in manuscript, some, perchance, in their own memories. Collating these, they subjected the text to minute revision, omitting and adding, altering and inserting, to suit their personal tastes and standards, literary or polite; and having thus made it over, forgot to record the act, and saw no reason to apologise therefor.

Pioneers like Thomas Percy, Bishop of Dromore, xi and Sir Walter Scott, may well be excused the general censure. The former, living in and pandering to an age which invented and applied those delightful literary adjectives ‘elegant’ and ‘ingenious,’ may be pardoned with the more sincerity if one recalls the influence exercised on English letters by his publication. The latter, who played the part of Percy in the matter of Scottish ballads, and was nourished from his boyhood on the Reliques, printed for the first time many ballads which still are the best of their class, and was gifted with consummate skill and taste. Both, moreover, did their work scientifically, according to their lights; and both have left at least some of their originals behind them. There is, perhaps, one more exception to the general condemnation. Of William Allingham’s Ballad Book, as truly a vade mecum as Palgrave’s lyrical anthology in the same ‘Golden Treasury’ series, I would speak, perhaps only for sentimental reasons, always with respect, admiring the results of his editing while looking askance at the method, for he mixed his ingredients and left no recipe.

But in the majority of cases there is no obvious excuse for this ‘omnium gatherum’ process. The self-imposed function of most ballad editors appears to have been the compilation xii of rifacimenti in accordance with their private ideas of what a ballad should be. And that such a state of things was permissible is doubtless an indication of the then prevalent attitude of half-interested tolerance assumed towards these memorials of antiquity.

To-day, however, the ballad editor is confronted with the results of the labours, still unfinished, of a comparatively recent school in literary science. These have lately culminated in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, edited by the late Professor Francis James Child of Harvard University. This work, in five large volumes, issued in ten parts at intervals from 1882 to 1898, and left by the editor at his death complete but for the Introduction—valde deflendus—gives in full all known variants of the three hundred and five ballads adjudged by its editor to be genuinely ‘popular,’ with an essay, prefixed to each ballad, on its history, origin, folklore, etc., and notes, glossary, bibliographies, appendices, etc.; exhibiting as a whole unrivalled special knowledge, great scholarly intuition, and years of patient research, aided by correspondents, students, and transcribers in all parts of the world, Lacking Professor Child’s Introduction, we cannot exactly tell what his definition of a ‘popular’ ballad was, or what qualities in a ballad implied xiii exclusion from his collection—e.g. he does not admit The Children in the Wood: otherwise one can find in this monumental work the whole history and all the versions of nearly all the ballads.

It will be obvious that Professor Child’s academic method is suited rather to the scholar than the general reader. As a rule, one text of each ballad is all that is required, which must therefore be chosen—but by what rules? To the scholar, it usually happens that the most ancient and least handled text is the most interesting; but these are too frequently incomplete and unintelligible. The literary dilettante may prefer tasteful decorations by a Percy or a Scott; doubtless Buchan has some admirers: but the student abhors this painting of the lily.

Therefore I have compromised—always a dangerous practice—and I have sought to give, to the best of my judgement, that authorised text of each ballad which tells in the best manner the completest form of the story or plot. I have been forced to make certain exceptions, but for all departures from the above rule I have given reasons which, I trust, will be found to justify the procedure; and in all cases the sources of each text or part of the text are indicated.

I am quite aware that it may fairly be asked: xiv Why not assume the immemorial privilege of a ballad editor, and concoct a text for yourself? Why, when any text of a ballad is, as you admit, merely a representative of parallel and similar traditional versions, should you not compile from those other variants a text which should combine the excellences of each, and give us the cream?

There are several objections to this course. However incompetent, I should not shrink from the labour involved; nor do I entirely approve the growing demand for German minuteness and exactitude in editors. But, firstly, the ballad should be subject to variation only while it is in oral circulation. Secondly, editorial garnishing has been overdone already, and my unwillingness to adopt that method is caused as much by the failure of the majority of editors as by the success of the few. Lastly, chacun a son goût; there is a kind of literary selfishness in emending and patching to suit one’s private taste, and, if any one wishes to do so, he will be most pleased with the result if he does it for himself.

This lengthy apologia is necessitated by a departure from the usual custom of ballad-editing. For the rest, my indebtedness to the work of Professor Child will be obvious throughout. Many of his most interesting texts were xv printed for the first time from manuscripts in private hands. These I have not sought to collate, which would, indeed, insult his accuracy and care. But in the case of texts from the Percy Folio, where the labour is rather to decipher than to transcribe accurately, I have resorted not only to the reprint of Hales and Furnivall, but to the Folio itself. The whimsical spelling of this MS. pleases me as often as it irritates, and I have ventured in certain ballads, e.g. Glasgerion, to modernise it, and in others, e.g. Old Robin of Portingale, to retain it literatim: in either case I have reduced to uniformity the orthography of the proper names. Transcripts from other MSS. are reproduced as they stand.

In the general Introduction I have tried to sketch the genesis and history of the ballad impartially in its several aspects, not for scholars and connoisseurs, but for those ready to learn. To supply deficiencies, I have added a list of books useful to the student of English ballads—to go no further afield. Each ballad also is prefaced with an introduction setting forth, besides the source of the text, as succinctly as is consistent with accuracy, the derivation, when known, of the story; the plot of similar foreign ballads; and points of interest in folklore, history, or criticism attached to the particular xvi ballad. Where the story is fragmentary, I have added an argument. It will be realised that such introductions at the best are but a thousandth part of what might be written; but if they shall play the part of hors d’œuvres, and whet the appetite to proceed to more solid food, the labour will not be lost.

Difficulties in the text are explained in footnotes. Few things are more vexatious to a reader than constant reference to a glossary; but as compensation for the educational value thus lost, the footnotes are, to a certain extent, progressive; that is to say, a word already explained in a foregoing ballad is not always explained again; and to the best of my ability I have freed the notes from the grotesque blunders observable in most modern editions of ballads.

Besides my indebtedness to the books mentioned in the bibliographical list, I have to acknowledge my thanks to the Rev. Sabine Baring Gould, for permission to use his version of The Brown Girl; to Mr. E. K. Chambers, for kindly reading the general Introduction; and to my friend and partner Mr. A. H. Bullen, for constant suggestions and assistance.

F. S.

xvii‘Y-a-t-il donc, dans les contes populaires, quelque chose d’intéressant pour un esprit sérieux?’—Cosquin.

The old ballads of England and Scotland are fine wine in cobwebbed bottles; and many have made the error of paying too much attention to the cobwebs and not enough attention to the wine. This error is as blameworthy as its converse: we must take the inside and the outside together.

The earliest sense of the word ‘ballad,’ or rather of its French and Provençal predecessors, balada, balade (derived from the late Latin ballare, to dance), was ‘a song intended as the accompaniment to a dance,’ a sense long obsolete.1 Next came the meaning, a simple song of sentiment or romance, of two verses or more, each of which is sung to the same air, the accompaniment being xviii subordinate to the melody. This sense we still use in our ‘ballad-concerts.’ Another meaning was that of simply a popular song or ditty of the day, lyrical or narrative, of the kind often printed as a broadsheet. Lyrical or narrative, because the Elizabethans appear not to distinguish the two. Read, for instance, the well-known scene in The Winter’s Tale (Act IV. Sc. 4); here we have both the lyrical ballad, as sung by Dorcas and Mopsa, in which Autolycus bears his part ‘because it is his occupation’; and also the ‘ballad in print,’ which Mopsa says she loves—‘for then we are sure it is true.’ Immediately after, however, we discover that the ‘ballad in print’ is the broadside, the narrative ballad, sung of a usurer’s wife brought to bed of twenty money-bags at a burden, or of a fish that appeared upon the coast on Wednesday the fourscore of April: in short, as Martin Mar-sixtus says (1592), ‘scarce a cat can look out of a gutter but out starts a halfpenny chronicler, and presently a proper new ballet of a strange sight is indited.’ Chief amongst these ‘halfpenny chroniclers’ were William Elderton, of whom Camden records that he ‘did arm himself with ale (as old father Ennius did with wine) when he ballated,’ and thereby obtained a red nose almost as celebrated as his verses; Thomas Deloney, ‘the ballating silkweaver of Norwich’; and Richard Johnson, maker of Garlands. Thus to Milton, to Addison, and even to Johnson, ‘ballad’ essentially implies singing; but from about the middle of the xix eighteenth century the modern interpretation of the word began to come into general use.

In 1783, in one of his letters, the poet Cowper says: ‘The ballad is a species of poetry, I believe, peculiar to this country.... Simplicity and ease are its proper characteristics.’ Here we have one of the earliest attempts to define the modern meaning of a ‘ballad.’ Centuries of use and misuse of the word have left us no unequivocal name for the ballad, and we are forced to qualify it with epithets. ‘Traditional’ might be deemed sufficient; but ‘popular’ or ‘communal’ is more definite. Here we adopt the word used by Professor Child—‘popular.’

What, then, do we intend to signify by the expression ‘popular ballads’? Far the most important point is to maintain an antithesis between the poetry of the people and the consciously artistic poetry of the schools. Wilhelm Grimm, the less didactic of the two famous brothers, said that the ballad says nothing unnecessary or unreal, and despises external adornment. Ferdinand Wolf, the great critic of the Homeric question, said the ballad must be naïve, objective, not sentimental, lively and erratic in its narrative, without ornamentation, yet with much picturesque vigour.

It is even more necessary to define sharply the line between poetry of the people and poetry for the people.2 The latter may still be written; xx the making of the former is a lost art. Poetry of the people is either lyric or narrative. This difference is roughly that between song and ballad. ‘With us,’ says Ritson, ‘songs of sentiment, expression, or even description, are properly termed songs, in contradistinction to mere narrative compositions which we now denominate Ballads.’ This definition, of course, is essentially modern; we must still insist on the fact that genuine ballads were sung: ‘I sing Musgrove,’3 says Sir Thwack in Davenant’s The Wits, ‘and for the Chevy Chase no lark comes near me.’ Lastly, we must emphasise that the accompaniment is predominated by the air to which the words are sung. I have heard the modern comic song described as ‘the kind in which you hear the words,’ thus differentiating it from the drawing-room song, in which the words are (happily) as a rule less audible than the melody. In the ballad, as sung, the words are most important; but it is of vital importance to remember that the ballads were chanted.

Now what is this ‘poetry of the people’? One theory is as follows. Every nation or people in the natural course of its development reaches a stage at which it consists of a homogeneous, compact community, with its sentiments xxi undivided by class-distinctions, so that the whole active body forms what is practically an individual. Begging the question, that poetry can be produced by such a body, this poetry is naturally of a concrete and narrative character, and is previous to the poetry of art. ‘Therefore,’ says Professor Child, ‘while each ballad will be idiosyncratic, it will not be an expression of the personality of individuals, but of a collective sympathy; and the fundamental characteristic of popular ballads is therefore the absence of subjectivity and self-consciousness. Though they do not “write themselves,” as Wilhelm Grimm has said—though a man and not a people has composed them, still the author counts for nothing, and it is not by mere accident, but with the best reason, that they have come down to us anonymous.’

By stating this, the dictum of one of the latest and most erudite of ballad-scholars, so early in our argument, we anticipate a century or more of criticism and counter-criticism, during which the giants of literature ranged themselves in two parties, and instituted a battle-royal which even now is not quite finished. It will be most convenient if we denominate the one party as that which holds to the communal or ‘nebular’ theory of authorship, and the other as the anti-communal or ‘artistic’ theory. The tenet of the former party has already been set forth, namely, that the poetry of the people is a natural and spontaneous production of a community at that stage xxii of its existence when it is for all practical purposes an individual. The theory of the ‘artistic’ school is that the ballads and folk-songs are the productions of skalds, minstrels, bards, troubadours, or other vagrant professional singers and reciters of various periods; it is allowed, however, that, being subject entirely to oral transmission, these ballads and songs are open to endless variation.

On the Continent, Herder was pioneer, both of the claims of popular poetry and of the nebular theory of authorship. Traditions of chivalry, he says, became poetry in the mouths of the people; but his definition of popular poetry has rather extended bounds. Herder’s enthusiasm fired Goethe (who, however, did not wholly accede to the ‘nebular’ theory) to study the subject, and the effect was soon noticeable in his own poetry. Next came the two great brothers, whose names are ever to be held in honour wherever folklore is studied or folktales read, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Jacob, the more ardent and polemical, insisted on the communal authorship of the poetry of the people; ballad or song ‘sings itself.’

Both the Grimms, and especially Jacob, were severely handled by the critic Schlegel, who insisted on the artist. To Schlegel we owe the famous image in which popular poetry is a tower, and the poet an architect. Hundreds may fetch and carry, but all are useless without the direction of the architect. This is specious argument; xxiii but we might reply to Schlegel that an architect is only wanted when the result is required to be an artistic whole. The tower of Babel was built by hundreds of men under no superintendence. Schlegel’s intention, however, is no less clear than that of Jacob Grimm, and the two are diametrically opposed.

In England, literary prejudice against the unpolished barbarities and uncouthnesses of the ballad was at no time so pronounced as it was on the Continent, and especially in Germany, during the latter half of the eighteenth century. Indeed, at intervals, the most learned and fantastic critics in England would call attention to the poetry of the people. Sir Philip Sidney’s apologetic words are well known:— ‘Certainly I must confesse my own barbarousnes, I never heard the olde song of Percy and Duglas, that I found not my heart mooved more then with a Trumpet.’ Addison was bolder. ‘It is impossible that anything should be universally tasted and approved by a Multitude, tho’ they are only the Rabble of a Nation, which hath not in it some peculiar Aptness to please and gratify the Mind of Man.’ With these and other encouragements the popular poetry of England was not lost to sight; and in 1765 the work of the good Bishop of Dromore gave the ballads a place in literature.

Percy’s opening remarks, attributing the ballads to the minstrels, are as well known as the scoffs of the hard-hitting Joseph Ritson, who xxiv contemptuously dismissed Percy’s theories,4 and refused to believe any ballad to be of earlier origin than the reign of Elizabeth. Sir Walter Scott was quite ready to accept the ballads as the productions of the minstrels, either as ‘the occasional effusions of some self-taught bard,’ or as abridged from the tales of tradition after the days when, as Alfred de Musset says, ‘our old romances spread their wings of gold towards the enchanted world.’

This brings us nearer to our own day. The argument is not closed, although we can discern offers of concession from either side. Svend Grundtvig, editor of the enormous collection of Danish ballads, distinguished the ballad from all forms of artistic literature, and would have the artist left out of sight; Nyrop and the Scandinavian scholars, on the other hand, entirely gave up the notion of communal authorship. Howbeit, the trend of modern criticism,5 on the whole, is towards a common belief regarding most ballads, which may be stated again, in Professor Child’s words: ‘Though a man and not a people has composed them, still the author counts for nothing, and it is not by mere accident, but with the best reason, that they have come down to us anonymous.’

xxvLet us then picture, however vaguely and uncertainly, the growth of a ballad. It is well known that the folklores of the various races of the world exhibit common features, and that the beliefs, superstitions, tales, even conventionalities of expression, of one race, are found to present constant and remarkable similarities to those of another. Whether these similarities are to be held mere coincidences, or whether they are to be explained by the theory of a common ancestry in the cradle of the world, is a side-issue into which I do not intend to enter. Suffice it that the fact is true, especially of the peoples who speak the Indo-European tongues. The lore which has for its foundation permanent and universal acceptance in the hearts of mankind is preserved by tradition, and remains independent of the criteria applied instinctively and unconsciously to artistic compositions. The community is one at heart, one in mind, one in method of expression. Tales are recited, verses chanted, and the singer of a clan makes his version of a popular story. Simultaneously other singers, it may be of other clans of the same race, or of another race altogether, elaborate their versions of the common theme. Meanwhile the first singer has again recited or chanted his ballad, and, having forgotten the exact wording, has altered it, and perhaps introduced improvements. The same happens in the other cases. xxvi The various audiences carry away as much as they can remember, and recite their versions, again with individual omissions, alterations, and additions. Thus, by ever-widening circles, the tale is distributed in countless forms over an unlimited area. The elements of the story remain, wholly or in part, while the literary clothing is altered according to the ‘taste and fancy’ of the reciter. The lore is now traditional, whether it be in prose, as Märchen, or in verse, as ballad. And so it remains in oral circulation—and therefore still liable to variation—until it is written down or printed. It is left ‘masterless,’ unsigned; for of the original author’s composition, may be, only a word or two remains. It has passed through many mouths, and has been made over countless times. But once written down it ceases virûm volitare per ora; the invention of printing has spoiled the powers of man’s memory.

We can now take up the tale at the fifteenth century; let us henceforth confine our attention to England. It is agreed on all sides that the fifteenth century was the period when, in England at least, the ballads first became a prominent feature. Of historical ballads, The Hunting of the Cheviot was probably composed as early as 1400 or thereabouts. The romances contemporaneously underwent a change, and took on a form nearer to that of the ballad. Whatever may be the date of the origin of the subject-matter, the literary clothing—language, mode of expression, colour—of no ballad, as we xxvii now have it, is much, earlier than 1400. The only possible exceptions to this statement are one or two of the Robin Hood ballads—attributed to the thirteenth century by Professor Child, but adhuc sub judice—and a ballad of sacred legend—Judas—which exists in a thirteenth-century manuscript in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge.

During the fifteenth century, the ballads, still purely narrative, were cast abroad through the length and breadth of the land, undergoing continual changes, modifications, enlargements, for better or for worse. They told of romance and chivalry, of historical, quasi-historical, and mythico-historical deeds, of the traditions of the Church and sacred legend, and of the lore that gathers round the most popular of heroes, Robin Hood. The earliest printed English ballad is the Gest of Robyn Hode, which now remains in a fragment of about the end of the fifteenth century.

The sixteenth century continued the process of the popularisation of ballads. Minstrels, who, as a class, had been slowly perishing ever since the invention of printing, were now vagrants, and the profession was decadent. Towards the end of the century we hear of Richard Sheale, whom we may describe as the first of the so-called ‘Last of the Minstrels.’ He describes himself as a minstrel of Tamworth, his business being to chant ballads and tell tales. We know that the ballad of The Hunting of the Cheviot was xxviii part of his repertory, for he wrote down his version, which is still preserved in the Ashmolean MSS. At the end of the sixteenth century the minstrels had fallen, in England at least, into entire degradation. In 1597, Percy notes, a statute of Elizabeth was passed including ‘minstrels, wandering abroad,’ amongst the other ‘rogues, vagabonds, and sturdy beggars’; and fifty years later Cromwell made a very similar ordinance.6

In Elizabeth’s reign we first meet with the ballad-mongers and professional authors of ballads. Simultaneously, or nearly so, comes the degradation of the word ‘ballad,’ until it signifies either the genuine popular ballad, or a satirical song, or a broadside, or almost any ditty of the day. Of the ballad-mongers, we have mentioned Elderton, Deloney, and Johnson. We might add a hundred others, from Anthony Munday to Martin Parker, and even Tom Durfey, each of whom contributed largely to the vast mushroom-literature that sprang up and flourished vigorously for the next century. Chappell mentions that seven hundred and ninety-six ballads remained at the end of 1560 in the cupboards of the council-chamber of the Stationers’ Company for transference to the new wardens of the succeeding year. These, of course, would consist chiefly of broadsides: the narrations of strange events, monstrosities, or ‘true tales’ of the day.

xxix It is true that many of the genuine popular ballads were rewritten to suit contemporary taste. But the style of the seventeenth century ballads cannot be compared to the noble straightforwardness and simplicity of the ancient ballad. Let us place side by side the first stanza of the Hunting of the Cheviot and the first few verses of Fair Rosamond, a very fair specimen of Deloney’s work.

The popular ancient ballad wastes no time on preliminaries7:—

‘The Persé owt off Northombarlonde

And avowe to God mayd he,

That he wold hunte in the mowntayns

Off Chyviat within days thre,

In the magger of doughté Dogles;

And all that ever with him be.’

Now for the milk-and-water:—

‘Whenas King Henry rulde this land,

The second of that name,

Besides the queene, he dearly lovde

A faire and comely dame.

Most peerlesse was her beautye founde,

Her favour and her face;

A sweeter creature in this worlde

Could never prince embrace.

Her crisped lockes like threads of golde

Appeard to each man’s sight;

Her sparkling eyes, like Orient pearles,

Did cast a heavenly light.’

xxx Ritson’s taste actually led him, in comparing the above two first verses, to prefer the latter.

Or again we might contrast Sir Patrick Spence—

‘The King sits in Dumferling towne

Drinking the blude reid wine:

“O whar will I get a guid sailor,To sail this ship of mine?”’

with the Children in the Wood:—

‘Now ponder well, you parents deare,

These wordes, which I shall write;

A doleful story you shall heare,

In time brought forth to light.’

Artificial, tedious, didactic. The author of the ancient ballad seldom points, and never draws, a moral, and has unbounded faith in the credulity of the audience. The seventeenth century balladists pitchforked Nature into the midden.

These compositions were printed as soon as written, or, to be exact, they were written for the press. We now class them as broadsides, that is, ballads printed on one side of the paper. The difference between these and the true ballad is the difference between art and nature. The broadside ballad was a form of art, and a low form of art. They were written by hacks for the press, sold in the streets, and pasted on the walls of houses or rooms: Jamieson had a copy of Young Beichan which he picked off a wall in Piccadilly. They were generally ornamented with crude woodcuts, remarkable for their artistic shortcomings and infidelity to nature. xxxi Dr. Johnson’s well-known lines—though in fact a caricature of Percy’s Hermit of Warkworth—ingeniously parody their style:—

‘As with my hat upon my head,

I walk’d along the Strand,

I there did meet another man,

With his hat in his hand.’

Broadside ballads, including a few of the genuine ancient ballads, still enjoy a certain popularity. The once-famous Catnach Press still survives in Seven Dials, and Mr. Such, of Union Street in the Borough, still maintains what is probably the largest stock of broadsides now in existence, including Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (or May Colvin), perhaps the most widely dispersed ballad of any.

Minstrels of all sorts were by this time nearly extinct, in person if not in name; their successors were the vendors of broadsides. Nevertheless, survivors of the genuine itinerant reciters of ballads have been discovered at intervals almost to the present day. Sir Walter Scott mentions a person who ‘acquired the name of Roswal and Lillian, from singing that romance about the streets of Edinburgh’ in 1770 or thereabouts. He further alludes to ‘John Graeme, of Sowport in Cumberland, commonly called the Long Quaker, very lately alive.’ Ritson mentions a minstrel of Derbyshire, and another from Gloucester, who chanted the ballad of Lord Thomas and Fair Eleanor. In 1845 J. H. Dixon wrote of several men he had met, chiefly Yorkshire dalesmen, xxxii not vagrants, but with a local habitation, who at Christmas-tide would sing the old ballads. One of these was Francis King, known then throughout the western dales of Yorkshire, and still remembered, as ‘the Skipton Minstrel.’ After a merry Christmas meeting, in the year 1844, he walked into the river near Gargrave, in Craven, and was drowned. In Gargrave church-yard lie the remains of perhaps the actual ‘last of the minstrels.’8

Now a word or two as to the collectors and editors. To take the broadsides first, the largest collections are at Magdalene College, Cambridge (eighteen hundred broadsides collected by Selden and Pepys), in the Bodleian at Oxford, and in the British Museum. The Bodleian contains collections made by Anthony-à-Wood, Douce, and Rawlinson; the British Museum, the great Roxburghe and Bagford collections, which have been reprinted and edited by William Chappell and the Rev. J. W. Ebsworth for the Ballad Society, as well as other smaller volumes of ballads.

But it is not among the broadsides that our xxxiii noblest ballads are found. The first attempt to collect popular ballads was made by the compiler of three volumes issued in 1723 and 1725. The editor is said to have been Ambrose Phillips, whose name and style combined to produce the word ‘namby-pamby.’ Next came Allan Ramsay, with ‘the Evergreen, a collection of Scots poems wrote by the ingenious before 1600.’—‘By the ingenious,’ we note; not by the ‘elegant.’ The tide is already beginning to turn; pitch-forked Nature will ever come back. Followed the Tea-Table Miscellany, also compiled by Allan Ramsay, which contained about twenty popular ballads, the rest being songs and ballads of modern composition. The texts were, of course, chopped about and pruned to suit contemporary taste. It was still necessary to adopt an apologetic attitude on behalf of these barbarous and crude relics of antiquity.

These books paved the way to the great literary triumph of the century. The first edition of Percy’s Reliques was issued in three volumes, in 1765. He received for it one hundred guineas, instant popularity and patronage, and subsequently, the gratitude of succeeding centuries.

Nevertheless, Percy himself was so far under the influence of his contemporaries that he felt it necessary to adopt the apologetic attitude. In his preface he wrote:— ‘In a polished age like the present, I am sensible that many of these reliques of antiquity will require great allowances xxxiv to be made for them.’ And again:— ‘To atone for the rudeness of the more obsolete poems, each volume concludes with a few modern attempts in the same kind of writing; and to take off from the tediousness of the longer narratives, they are everywhere intermingled with little elegant pieces of the lyrical kind.’ In short, he could not trust that large child, the people of England, to take its dose of powder without the conventional treacle. To vary the metaphor, his famous Folio Manuscript he regarded as a Cinderella, and in his capacity as fairy godmother refused to introduce her to the world without hiding the slut’s uncouth attire under fine raiment. To which end, besides adding ‘little elegant pieces,’ he recast and rewrote ‘the more obsolete poems,’ many of which came direct from the Folio Manuscript. Are we to blame him for yielding to the taste of his day?

He did not satisfy every one. Ritson’s immediate outcry is famous—and Ritson stood almost alone. He did, indeed, go so far as to deny the existence of the Folio Manuscript, and Percy was forced to confute him by producing it. In the later editions of the Reliques, Percy sought to conciliate him by revising his texts, so as to approximate them more closely to his originals, but still Ritson cried out for the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. And by this time he had supporters. But the whole truth as regards the Folio was not to be divulged yet. The manuscript was most jealously guarded.

xxxv Meanwhile the influence of the publication was having its effect. The poetry of the schools, the poetry of the intellect, the poetry of art, brought to its highest pitch by writers like Dryden and Pope, was shelved; metrically exact diction, artificiality of expression, carefully balanced antitheses, and all the mechanical devices of the school were placed in abeyance. There was a general return to Nature, to simplicity, to straightforwardness—not without imagination, however. Wordsworth, besides insisting, in a famous passage, the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, on the spontaneity of good poetry, recorded his tribute to the Reliques: ‘I do not think that there is an able writer in verse of the present day who would not be proud to acknowledge his obligation to the Reliques.’ While failing often to catch the gusto of ancient poetry—witness his translations from Chaucer—Wordsworth was full of the spirit—witness his rifacimento of The Owl and the Nightingale—and, best of all, handed it on to Coleridge.9 These two fought side by side against the conventions of the preceding century, against Dryden, Addison, Pope, and last, but not least, Johnson. Some have gone so far as to place the definite turning-point in the year 1798, the year xxxvi of the publication of the Lyrical Ballads. Coleridge’s annus mirabilis was 1797, and the publication of The Ancient Mariner is significant of the change. But we need not bind ourselves down to any given year. Enough that the revolution was effected, and that it is scarcely exaggeration to say that it was almost entirely due to the publication of the Reliques.

Sir Walter Scott remembered to the day of his death the place where he first made acquaintance with the Reliques in his thirteenth year. ‘I remember well the spot where I read those volumes for the first time. It was beneath a large platanus-tree, in the ruins of what had been intended for an old-fashioned arbour in the garden I have mentioned. The summer day sped onward so fast, that, notwithstanding the sharp appetite of thirteen, I forgot the hour of dinner, was sought for with anxiety, and was still found entranced in my intellectual banquet.’

Almost immediately competitors appeared in the field, and especial attention was given to Scotland, exceedingly rich ground, as it proved. In 1769, David Herd published his collection of Ancient and Modern Scots Songs, Heroic Ballads, etc. Then, at intervals of two or three years only, came the compilations of Evans, Pinkerton, Ritson, Johnson; in 1802 Sir Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, fit to be placed side by side with the Reliques; in 1806 Jamieson’s Popular Ballads and Songs; then Finlay, Gilchrist, Laing, and Utterson. In 1828 the xxxvii egregious Peter Buchan produced Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland, hitherto unpublished. Buchan hints that he kept a pedlar or beggarman—‘a wight of Homer’s craft’—travelling through Scotland to pick up ballads; and one of the two—probably Buchan—must have been possessed of powerful inventive faculties. Each of Buchan’s ballads is tediously spun out to enormous and unnecessary length, and is filled with solecisms and inanities quite inconsistent with the spirit of the true ballad. But Buchan undoubtedly gained fresh material, however much he clothed it; and his ballads are now reprinted, as Professor Child says, for much the same reason that thieves are photographed.

Scotland continued the work with two excellent students and pioneers, George Kinloch and William Motherwell. Next, Robert Chambers published a collection of eighty ballads, some being spurious. This was in 1829. Thirty years later Chambers came to the conclusion that ‘the high-class romantic ballads of Scotland ... are not older than the early part of the eighteenth century, and are mainly, if not wholly, the production of one mind.’ And this one mind, he thinks, was probably that of Elizabeth, Lady Wardlaw, the acknowledged forger of the ballad Hardyknute, which deceived so many. Chambers, of course, was absurdly mistaken.

So the work of collecting and editing progressed through the nineteenth century, till it culminated in the final edition of Professor Child’s English xxxviii and Scottish Popular Ballads. But even this is scarcely his greatest benefaction to the study of ballads. We must confess that had it not been for the insistence of this American scholar, the Percy Folio Manuscript would remain a sealed book. For six years Professor Child persecuted Dr. Furnivall, who persecuted in turn the owners of the Folio, even offering sums of money, for permission to print the MS. Eventually they succeeded, and not only succeeded in giving to the world an exact reprint,10 but also once for all secured the precious original for the British Museum, where it now remains.11

And what is this manuscript? In brief, it is an example of the commonplace books which abounded in the seventeenth century. But it is unique in containing a large proportion of early romances and ballads, as well as the lyrics of the day. Of the hundreds of commonplace books made during that century, no other example is known which contains such matter, for the obvious and simple reason that such matter was despised.12 The handwriting is put by experts at about 1650; it cannot be much later, and one song in it contains a passage which fixes the date of that song xxxix to the year 1643. Percy discovered the book ‘lying dirty on the floor under a bureau in the parlour’ of his friend Humphrey Pitt of Shifnal, in Shropshire, ‘being used by maids to light the fire.’ Mr. Pitt’s fires were lighted with half-pages torn out from incomparably early and precious versions of certain Robin Hood and other ballads. Percy notes that he was very young when he first got possession of the MS., and had not then learned to reverence it. When he put it into boards to lend to Dr. Johnson, the bookbinder pared the margins, and cut away top and bottom lines. In editing the Reliques, Percy actually tore out pages ‘to save the trouble of transcribing.’ In spite of all, it remains a unique and inestimably valuable manuscript. Its writer was presumably a Lancashire man, from his use of certain dialect words, and was assuredly a man of slight education; nevertheless a national benefactor.

In speaking of manuscripts, we must not omit to mention the Scottish collectors. Most of them went to work in the right way, seeking out aged men and women in out-of-the-way corners of Scotland, and taking down their ballads from their lips. If we condemn these editors for subsequently adorning the traditional versions, we must be grateful to them for preserving their manuscripts so that we can still read the ballads as they received them. The old ladies of Scotland seem to have possessed better memories than the old men. Besides Sir Walter Scott’s anonymous ‘Old Lady,’ there was another to xl whom we owe some of the finest versions of the Scottish ballads. This was Mrs. Brown, daughter of Professor Gordon of Aberdeen. Born in 1747, she learned most of her ballads before she was twelve years old, or before 1759, from the singing of her aunt, Mrs. Farquhar of Braemar. From about twenty to forty years later, she repeated her ballads, first to Jamieson, and afterwards to William Tytler, each of whom compiled a manuscript. The latter, the Tytler-Brown MS., unfortunately is lost, but the ballads are practically all known from the other manuscript and various sources.

Perhaps the richest part of our stock are the Scottish and Border ballads. Beside them, most of our mawkish English ballads look pale and withered. The reason, perhaps, may be traced to the effect of natural surroundings on literature. The English ballads were printed or written down at a period which is early compared with the date of collection of the Scottish ballads. In fact, it is only during the last hundred and thirty years that the ballads of Scotland have been recovered from oral tradition. In mountainous districts, where means of communication and intercourse are naturally limited, tradition dies more hard than in countries where there are no such barriers. Moreover, as Professor Child points out, ‘oral transmission by the unlettered is not to be feared nearly so much as by minstrels, nor by minstrels nearly so much as modern editors.’ Svend Grundtvig illustrates this from his xli twenty-nine versions of the Danish ballad ‘Ribold and Guldborg.’ In versions from recitation, he has shown that there occur certain verses which have never been printed, but which are found in old manuscripts; and these recited versions also contain verses which have never been either printed or written down in Danish, but which are to be found still in recitation, not only in Norwegian and Swedish versions, but even in Icelandic tradition of two hundred years’ standing.

Such, then, is the history of our ballads, so far as it may be stated in a few pages. With regard to origins, the ‘nebular’ theory cannot be summarily dismissed;13 but, after weighing the evidence and arguments, the balance of probability would seem to lie with the supporters of the ‘artistic’ theory in a modified form. The ballad may say, with Topsy, ‘Spec’s I growed’; but vires adquirit eundo is only true of the ballad to a certain point; progress, which includes the invention of printing and the absorption into cities of the unsophisticated rural population, has since killed the oral circulation of the ballad. Thus it was not an unmixed evil that in the Middle Ages, as a rule, the ballads were neglected; for this neglect, while it rendered the discovery of their sources almost impossible, gave the ballads for a time into the safe-keeping xlii of their natural possessors, the common people. Civilisation, advancing more swiftly in some countries than in others, has left rich stores here, and little there. Our close kinsmen of Denmark, and the rest of Scandinavia, possess a ballad-literature of which they do well to be proud; and Spain is said to have inherited even better legacies. A study of our native ballads yields much interest, much delight, and much regret that the gleaning is comparatively so small. But what we still have is of immense value. The ballads may not be required again to revoke English literature from flights into artificiality and subjectivity; but they form a leaf in the life of the English people, they uphold the dignity of human nature, they carry us away to the legends, the romances, the beliefs, the traditions of our ancestors, and take us out of ourselves to ‘fleet the time carelessly, as they did in the golden world.’

xliiiThe only possible method of classifying ballads is by their subject-matter; and even thus the lines of demarcation are frequently blurred. It is, however, possible to divide them roughly into several main classes, such as ballads of romance and chivalry; ballads of superstition and of the supernatural; Arthurian, historical, sacred, domestic ballads; ballads of Robin Hood and other outlaws; and so forth.

The present volume is concerned with ballads of romance and chivalry; but it is useless to press too far the appropriateness of this title. The Nutbrown Maid, for instance, is not a true ballad at all, but an amœbæan idyll, or dramatic lyric. But, on the whole, these ballads chiefly tell of life, love, death, and human passions, of revenge and murder and heroic deed.

‘These things are life:

And life, some think, is worthy of the Muse.’

They are left unexpurgated, as they came down to us: to apologise for things now left unsaid would be to apologise not only for the heroic epoch in which they were born, but also for human nature.

xliv And how full of life that heroic epoch was! Of what stature must Lord William’s steed have been, if Lady Maisry could hear him sneeze a mile away! How chivalrous of Gawaine to wed an ugly bride to save his king’s promise, and how romantic and delightful to discover her on the morrow to have changed into a well-fared may!

The popular Muse regards not probability. Old Robin, who hails from Portugal, marries the daughter of the mayor of Linne, that unknown town so dear to ballads. In Young Bekie, Burd Isbel’s heart is wondrous sair to find, on liberating her lover, that the bold rats and mice have eaten his yellow hair. We must not think of objecting that the boldest rat would never eat a live prisoner’s hair, but only applaud the picturesque indication of durance vile.

In the same ballad, Burd Isbel, ‘to keep her from thinking lang’—a prevalent complaint—is told to take ‘twa marys’ on her journey. We suddenly realise how little there was to amuse the Burd Isbels of yore. Twa marys provide a week’s diversion. Otherwise her only occupation would have been to kemb her golden hair, or perhaps, like Fair Annie, drink wan water to preserve her complexion.

But if their occupations were few, their emotions and affections were strong. Ellen endures insult after insult from Child Waters with the faithful patience of a Griselda. Hector the hound recognises Burd Isbel after years of separation. Was any lord or lady in need of xlv a messenger, there was sure to be a little boy at hand to run their errand soon, faithful unto death. On receipt of painful news, they kicked over the table, and the silver plate flew into the fire. When roused, men murdered with a brown sword, and ladies with a penknife. We are left uncertain whether the Cruel Mother did not also ‘howk’ a grave for her murdered babe with that implement.

But readers will easily pick out and enjoy for themselves other instances of the naïve and picturesque in these ballads.

xlviThere survive in ballads a few conventional phrases, some of which appear to have been preserved by tradition beyond an understanding of their import. I give here short notes on a few of the more interesting phrases and words which appear in the present volume, the explanations being too cumbrous for footnotes.

‘bent his bow and swam,’ Lady Maisry, 21.2; Johney Scot, 10.2; Lord Ingram and Chiel Wyet, 12.2; etc.

‘set his bent bow to his breast,’ Lady Maisry, 22.3; Lord Ingram and Chiel Wyet, 13.3; Fause Footrage, 33.1; etc.

Child attempts no explanation of this striking phrase, which, I believe, all editors have either openly or silently neglected. Perhaps ‘bent’ may mean un-bent, i.e. with the string of the bow slacked. If so, for what reason was it done before swimming? We can understand that it would be of advantage to keep the string dry, but how is it better protected when unstrung? Or, again, was it carried unstrung, xlvii and literally ‘bent’ before swimming? Or was the bow solid enough to be of support in the water?

Some one of these explanations may satisfy the first phrase (as regards swimming); but why does the messenger ‘set his bent bow to his breast’ before leaping the castle wall? It seems to me that the two expressions must stand or fall together; therefore the entire lack of suggestions to explain the latter phrase drives me to distrust of any of the explanations given for the former.

A suggestion recently made to me appears to dispose of all difficulties; and, once made, is convincing in its very obviousness. It is, that ‘bow’ means ‘elbow,’ or simply ‘arm.’ The first phrase then exhibits the commonest form of ballad-conventionalities, picturesque redundancy: the parallel phrase is ‘he slacked his shoon and ran.’ In the second phrase it is, indeed, necessary to suppose the wall to be breast-high; the messenger places one elbow on the wall, pulls himself up, and vaults across.

Lexicographers distinguish between the Old English bōg or bōh (O.H.G. buog = arm; Sanskrit, bahu-s = arm), which means arm, arch, bough, or bow of a ship; and the Old English boga (O.H.G. bogo), which means the archer’s bow. The distinction is continued in Middle English, from the twelfth to the fifteenth century. Instances of the use of the word as equivalent to ‘arm’ may be found in Old English in King Alfred’s Translation of Gregory’s Pastoral Care (E.E.T.S., 1871, ed. H. Sweet) written in West Saxon dialect of the ninth century.

It is true that the word does not survive elsewhere in this meaning, but I give the suggestion for what it is worth.

xlviii‘briar and rose,’ Douglas Tragedy, 18, 19, 20; Fair Margaret and Sweet William, 18, 19, 20; Lord Lovel, 9, 10; etc.

‘briar and birk,’ Lord Thomas and Fair Annet, 29, 30; Fair Janet, 30; etc.

‘roses,’ Lady Alice, 5, 6. (See introductory note to Lord Lovel, p. 67.)

The ballads which exhibit this pleasant conception that, after death, the spirits of unfortunate lovers pass into plants, trees, or flowers springing from their graves, are not confined to European folklore. Besides appearing in English, Gaelic, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, German, French, Roumanian, Romaic, Portuguese, Servian, Wendish, Breton, Italian, Albanian, Russian, etc., we find it occurring in Afghanistan and Persia. As a rule, the branches of the trees intertwine; but in some cases they only bend towards each other, and kiss when the wind blows.

In an Armenian tale a curious addition is made. A young man, separated by her father from his sweetheart because he was of a different religion, perished with her, and the two were buried by their friends in one grave. Roses grew from the grave, and sought to intertwine, but a thorn-bush sprang up between them and prevented it. The thorn here is symbolical of religious belief.

‘thrilled upon a pin,’ Glasgerion, 10.2.

‘knocked at the ring,’ Fair Margaret and Sweet William, 11.2.

(Cp. ‘lifted up the pin,’ Fair Janet, 14.2.)

xlixThroughout the Scottish ballads the expression is ‘tirl’d at the pin,’ i.e. rattled or twisted the pin.

The pin appears to have been the external part of the door-latch, attached by day thereto by means of a leathern thong, which at night was disconnected with the latch to prevent any unbidden guest from entering. Thus any one ‘tirling at the pin’ does not attempt to open the door, but signifies his presence to those within.

The ring was merely part of an ordinary knocker, and had nothing to do with the latching of the door.

‘bright brown sword,’ Glasgerion, 22.1; Old Robin of Portingale, 22.1; Child Maurice, 26.1, 27.1; ‘good browne sword,’ Marriage of Sir Gawaine, 24.3; etc.

‘dried it on his sleeve,’ Glasgerion, 22.2; Child Maurice, 27.2 (‘on the grasse,’ 26.2); ‘straiked it o’er a strae,’ Bonny Birdy, 15.2; ‘struck it across the plain,’ Johney Scot, 32.2; etc.

In Anglo-Saxon, the epithet ‘brún’ as applied to a sword has been held to signify either that the sword was of bronze, or that the sword gleamed. It has further been suggested that sword-blades may have been artificially bronzed, like modern gun-barrels.

‘Striped it thro’ the straw’ and many similar expressions all refer to the whetting of a sword, generally just before using it. Straw (unless ‘strae’ and ‘straw’ mean something else) would appear to be very poor stuff on which to sharpen swords, but Glasgerion’s sleeve would be even less effective; l perhaps, however, ‘dried’ should be ‘tried.’ Johney Scot sharpened his sword on the ground.

‘gare’ = gore, part of a woman’s dress; Brown Robin, 10.4; cp. Glasgerion, 19.4.

Generally of a knife, apparently on a chatelaine. But in Lamkin 12.2, of a man’s dress.

‘Linne,’ ‘Lin,’ Young Bekie, 5.4; Old Robin of Portingale, 2.1.

A stock ballad-locality, castle or town. Perhaps to be identified with the city of Lincoln, perhaps with Lynn, or King’s Lynn, in Norfolk, where pilgrims of the fourteenth century visited the Rood Chapel of Our Lady of Lynn, on their way to Walsingham; with equal probability it is not to be identified at all with any known town.

‘shot-window,’ Gay Goshawk, 8.3; Brown Robin, 3.3; Lamkin, 7.3; etc.

This commonplace phrase seems to vary in meaning. It may be ‘a shutter of timber with a few inches of glass above it’ (Wodrow’s History of the Sufferings of the Church of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1721-2, 2 vols., in vol. ii. p. 286); it may be simply ‘a window to open and shut,’ as Ritson explains it; or again, as is implied in Jamieson’s Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language, an out-shot window, or bow-window. The last certainly seems to be intended in certain instances.

li‘thought lang’ Young Bekie, 16.4; Brown Adam, 5.2; Johney Scot, 6.2; Fause Footrage, 25.2; etc.

This simply means ‘thought it long,’ or ‘thought it slow,’ as we should say in modern slang; in short, ‘was bored,’ or ‘weary.’

‘wild-wood swine,’ a simile for drunkenness, Brown Robin, 7.4; Fause Footrage, 16.4.

Cp. Shakespeare, All’s Well that Ends Well, Act IV. 3, 286: ‘Drunkenness is his best virtue; for he will be swine-drunk.’ It seems to be nothing more than a popular comparison.

lii|

The Introductions, etc., to the Collections of Ballads in List B. |

|

| 1861. | David Irving. History of Scottish Poetry. |

| 1871. | Thomas Warton. History of English Poetry, ed. W. Carew Hazlitt. 4 vols. |

| 1875. | Andrew Lang. Article in Encyclopædia Britannica (9th edition), vol. iii. |

| 1876. | Stopford Brooke. English Literature. New edition, enlarged, 1897. |

| 1883. | W. W. Newell. Games and Songs of American Children. New York. |

| 1887. | Andrew Lang. Myth, Ritual, and Religion. 2 vols. |

| 1893. | John Veitch. History and Poetry of the Scottish Border. 2 vols. |

| 1893. | F. J. Child. Article ‘Ballads’ in Johnson’s Cyclopædia, vol. i. pp. 464‑6. |

| 1895‑97. | W. J. Courthope. A History of English Poetry. Vols. i. and ii. |

| 1897. | G. Gregory Smith. The Transition Period: being vol. iv. of Periods of English Literature, ed. G. Saintsbury. |

| 1898. | Andrew Lang in Quarterly Review for July. |

| 1901. | F. B. Gummere. The Beginnings of Poetry. |

| 1903. | E. K. Chambers. The Mediæval Stage. 2 vols. |

| 1903. | Andrew Lang in Folk-Lore for June. |

| 1903. | J. H. Millar. A Literary History of Scotland. |

The illustrations on pp. 28, 75, and 118 are taken from Royal MS. 10. E. iv. (of the fourteenth century) in the British Museum, where they occur on folios 34 verso, 215 recto, and 254 recto respectively. The designs in the original form a decorated margin at the foot of each page, and are outlined in ink and roughly tinted in three or four colours. Much use is made of them in the illustrations to J. J. Jusserand’s English Wayfaring Life in the Middle Ages, where M. Jusserand rightly points out that this MS. ‘has perhaps never been so thoroughly studied as it deserves.’

1. For the subject of the origin of the ballad and its refrain in the ballatio of the dancing-ring, see The Beginnings of Poetry, by Professor Francis B. Gummere, especially chap. v. The beginning of the whole subject is to be found in the universal and innate practices of accompanying manual or bodily labour by a rhythmic chant or song, and of festal song and dance.

2. See the first essay, ‘What is “Popular Poetry”?’ in Ideas of Good and Evil, by W. B. Yeats (1903), where this distinction is not recognised.

3. Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard (see p. 19, etc.).

4. ‘The truth really lay between the two, for neither appreciated the wide variety covered by a common name’ (The Mediæval Stage, E. K. Chambers, 1903). See especially chapters iii. and iv. of this work for an admirably complete and illuminating account of minstrelsy.

5. For the most recent discussions, see Bibliography, p. lii.

6. But these were only re-enactments of existing laws. See Chambers, Mediæval Stage, i. p. 54.

7. A good notion of the way in which the old ballads plunge in medias res may be obtained by reading the Index of First Lines.

8. Unless we may attribute that distinction to the blind Irish bard Raftery, who flourished sixty years ago. See various accounts of him given by Lady Gregory (Poets and Dreamers) and W. B. Yeats (The Celtic Twilight, 1902). But he appears to have been more of an improviser than a reciter.

9. ‘He [Coleridge] said the Lyrical Ballads were an experiment about to be tried by him and Wordsworth, to see how far the public taste would endure poetry written in a more natural and simple style than had hitherto been attempted; totally discarding the artifices of poetical diction, and making use only of such words as had probably been common in the most ordinary language since the days of Henry II.’—Hazlitt.

10. Bishop Percy’s Folio Manuscript, edited by J. W. Hales and F. J. Furnivall, 4 vols., 1867-8. Printed for the Early English Text Society and subscribers.

11. Additional MS. 27, 879.

12.

Cp. Love’s Labour’s Lost:—

Armado. Is there not a ballad, boy, of

the King and the Beggar?

Moth. The world was very guilty of such

a ballad some three ages since; but I think now ’tis not to be

found.

13. Professor Gummere (The Beginnings of Poetry) is perhaps the strongest champion of this theory, and takes an extreme view.

Ther herde I pleyen on an harpe

That souned bothe wel and sharpe,

Orpheus ful craftely,

And on his syde, faste by,

Sat the harper Orion,

And Eacides Chiron,

And other harpers many oon,

And the BretA Glascurion.

—Chaucer, Hous of Fame, III.

The Text, from the Percy Folio, luckily is complete, saving an omission of two lines. A few obvious corrections have been introduced, and the Folio reading given in a footnote. Percy printed the ballad in the Reliques, with far fewer alterations than usual.

The Story is also told in a milk-and-water Scotch version, Glenkindie, doubtless mishandled by Jamieson, who ‘improved’ it from two traditional sources. The admirable English ballad gives a striking picture of the horror of ‘churlës blood’ proper to feudal days.

In the quotation above, Chaucer places Glascurion with Orpheus, Arion, and Chiron, four great harpers. It is not improbable that Glascurion and Glasgerion represent the Welsh bard Glas Keraint (Keraint the Blue Bard, the chief bard wearing a blue robe of office), said to have been an eminent poet, the son of Owain, Prince of Glamorgan.

The oath taken ‘by oak and ash and thorn’ (stanza 18) is a relic of very early times. An oath ‘by corn’ is in Young Hunting.

A. From Skeat’s edition: elsewhere quoted ‘gret Glascurion.’

21.

1.4 Folio:— ‘where cappe & candle yoode.’ Percy in the Reliques (1767) printed ‘cuppe and caudle stoode.’

1.6 ‘wood,’ mad, wild (with delight).

Glasgerion was a king’s own son,

And a harper he was good;

He harped in the king’s chamber,

Where cup and candle stood,

And so did he in the queen’s chamber,

Till ladies waxed wood.

2.

And then bespake the king’s daughter,

And these words thus said she:

.....

.....

3.

3.2 ‘blin,’ cease.

Said, ‘Strike on, strike on, Glasgerion,

Of thy striking do not blin;

There’s never a stroke comes over this harp

But it glads my heart within.’

4.

4.4 i.e. durst never speak my mind.

‘Fair might you fall, lady,’ quoth he;

‘Who taught you now to speak?

I have loved you, lady, seven year;

My heart I durst ne’er break.’

5.

‘But come to my bower, my Glasgerion,

When all men are at rest;

As I am a lady true of my promise,

Thou shalt be a welcome guest.’

36.

6.1 ‘home’; Folio whom.

But home then came Glasgerion,

A glad man, Lord, was he!

‘And come thou hither, Jack, my boy,

Come hither unto me.

7.

7.3,4 These lines are reversed in the Folio.

‘For the king’s daughter of Normandy

Her love is granted me,

And before the cock have crowen

At her chamber must I be.’

8.

‘But come you hither, master,’ quoth he,

‘Lay your head down on this stone;

For I will waken you, master dear,

Afore it be time to gone.’

9.

9.1 ‘lither,’ idle, wicked.

But up then rose that lither lad,

And did on hose and shoon;

A collar he cast upon his neck,

He seemed a gentleman.

10.

10.2 ‘thrilled,’ twirled or rattled; cp. ‘tirled at the pin,’ a stock ballad phrase (Scots).

And when he came to that lady’s chamber,

He thrilled upon a pin.

The lady was true of her promise,

Rose up, and let him in.

11.

He did not take the lady gay

To bolster nor no bed,

But down upon her chamber-floor

Full soon he hath her laid.

412.

12.2 ‘yode,’ went.

He did not kiss that lady gay

When he came nor when he yode;

And sore mistrusted that lady gay

He was of some churlës blood.

13.

But home then came that lither lad,

And did off his hose and shoon.

And cast that collar from about his neck;

He was but a churlës son:

‘Awaken,’ quoth he, ‘my master dear,

I hold it time to be gone.

14.

14.4 ‘time’: Folio times.

‘For I have saddled your horse, master,

Well bridled I have your steed;

Have not I served a good breakfast?

When time comes I have need.’

15.

But up then rose good Glasgerion,

And did on both hose and shoon,

And cast a collar about his neck;

He was a kingës son.

16.

And when he came to that lady’s chamber,

He thrilled upon a pin;

The lady was more than true of her promise,

Rose up, and let him in.

17.

17.3 Folio you are.

Says, ‘Whether have you left with me

Your bracelet or your glove?

Or are you back returned again

To know more of my love?’

518.

Glasgerion swore a full great oath

By oak and ash and thorn,

‘Lady, I was never in your chamber

Sith the time that I was born.’

19.

‘O then it was your little foot-page

Falsely hath beguiled me’:

And then she pull’d forth a little pen-knife

That hanged by her knee,

Says, ‘There shall never no churlës blood

Spring within my body.’

20.

But home then went Glasgerion,

A woe man, good [Lord], was he;

Says, ‘Come hither, thou Jack, my boy,

Come thou thither to me.

21.

‘For if I had killed a man to-night,

Jack, I would tell it thee;

But if I have not killed a man to-night,

Jack, thou hast killed three!’

22.

22.2 Another commonplace of the ballads. The Scotch variant is generally, ‘And striped it thro’ the straw.’ See special section of the Introduction.

And he pull’d out his bright brown sword,

And dried it on his sleeve,

And he smote off that lither lad’s head,

And asked no man no leave.

23.

23.1,2 ‘till,’ to, against.

He set the sword’s point till his breast,

The pommel till a stone;

Thorough that falseness of that lither lad

These three lives were all gone.

The Text is that of the Jamieson-Brown MS., taken down from the recitation of Mrs. Brown about 1783. In printing the ballad, Jamieson collated with the above two other Scottish copies, one in MS., another a stall-copy, a third from recitation in the north of England, a fourth ‘picked off an old wall in Piccadilly’ by the editor.

The Story has several variations of detail in the numerous versions known (Young Bicham, Brechin, Bekie, Beachen, Beichan, Bichen, Lord Beichan, Lord Bateman, Young Bondwell, etc.), but the text here given is one of the most complete and vivid, and contains besides one feature (the ‘Belly Blin’) lost in all other versions but one.

A similar story is current in the ballad-literature of Scandinavia, Spain, and Italy; but the English tale has undoubtedly been affected by the charming legend of Gilbert Becket, the father of Saint Thomas, who, having been captured by Admiraud, a Saracen prince, and held in durance vile, was freed by Admiraud’s daughter, who then followed him to England, knowing no English but ‘London’ and ‘Gilbert’; and after much tribulation, found him and was married to him. ‘Becket’ is sufficiently near ‘Bekie’ to prove contamination, but not to prove that the legend is the origin of the ballad.

The Belly Blin (Billie Blin = billie, a man; blin’, blind, and so Billie Blin = Blindman’s Buff, formerly 7 called Hoodman Blind) occurs in certain other ballads, such as Cospatrick, Willie’s Lady, and the Knight and the Shepherd’s Daughter; also in a mutilated ballad of the Percy Folio, King Arthur and King Cornwall, under the name Burlow Beanie. In the latter case he is described as ‘a lodly feend, with seuen heads, and one body,’ breathing fire; but in general he is a serviceable household demon. Cp. German bilwiz, and Dutch belewitte.

1.

Young Bekie was as brave a knight

As ever sail’d the sea;

An’ he’s doen him to the court of France,

To serve for meat and fee.

2.

He had nae been i’ the court of France

A twelvemonth nor sae long,

Til he fell in love with the king’s daughter,

An’ was thrown in prison strong.

3.

The king he had but ae daughter,

Burd Isbel was her name;

An’ she has to the prison-house gane,

To hear the prisoner’s mane.

4.

4.1 ‘borrow,’ ransom.

‘O gin a lady woud borrow me,

At her stirrup-foot I woud rin;

Or gin a widow wad borrow me,

I woud swear to be her son.

85.

‘Or gin a virgin woud borrow me,

I woud wed her wi’ a ring;

I’d gi’ her ha’s, I’d gie her bowers,

The bonny tow’rs o’ Linne.’

6.

6.1,2 ‘but ... ben,’ out ... in.

O barefoot, barefoot gaed she but,

An’ barefoot came she ben;

It was no for want o’ hose an’ shoone,

Nor time to put them on;

7.

7.3 ‘stown,’ stolen.

But a’ for fear that her father dear,

Had heard her making din:

She’s stown the keys o’ the prison-house dor

An’ latten the prisoner gang.

8.

8.3 ‘rottons,’ rats.

O whan she saw him, Young Bekie,

Her heart was wondrous sair!

For the mice but an’ the bold rottons

Had eaten his yallow hair.

9.

She’s gi’en him a shaver for his beard,

A comber till his hair,

Five hunder pound in his pocket,

To spen’, and nae to spair.

10.

She’s gi’en him a steed was good in need,

An’ a saddle o’ royal bone,

A leash o’ hounds o’ ae litter,

An’ Hector called one.

11.

Atween this twa a vow was made,

’Twas made full solemnly,

That or three years was come and gane,

Well married they shoud be.

912.

He had nae been in’s ain country

A twelvemonth till an end,

Till he’s forc’d to marry a duke’s daughter,

Or than lose a’ his land.

13.

‘Ohon, alas!’ says Young Bekie,

‘I know not what to dee;

For I canno win to Burd Isbel,

And she kensnae to come to me.’

14.

O it fell once upon a day

Burd Isbel fell asleep,

An’ up it starts the Belly Blin,

An’ stood at her bed-feet.

15.

15.2 The MS. reads ‘How y you.’

‘O waken, waken, Burd Isbel,

How [can] you sleep so soun’,

Whan this is Bekie’s wedding day,

An’ the marriage gain’ on?

16.

16.3 ‘marys,’ maids.

’Ye do ye to your mither’s bow’r,

Think neither sin nor shame;

An’ ye tak twa o’ your mither’s marys,

To keep ye frae thinking lang.

17.

‘Ye dress yoursel’ in the red scarlet,

An’ your marys in dainty green,

An’ ye pit girdles about your middles

Woud buy an earldome.

18.

‘O ye gang down by yon sea-side,

An’ down by yon sea-stran’;

Sae bonny will the Hollans boats

Come rowin’ till your han’.

1019.

‘Ye set your milk-white foot abord,

Cry, Hail ye, Domine!

An’ I shal be the steerer o’t,

To row you o’er the sea.’

20.

She’s tane her till her mither’s bow’r,

Thought neither sin nor shame,

An’ she took twa o’ her mither’s marys,

To keep her frae thinking lang.

21.

She dress’d hersel’ i’ the red scarlet.

Her marys i’ dainty green,

And they pat girdles about their middles

Woud buy an earldome.

22.

An’ they gid down by yon sea-side,

An’ down by yon sea-stran’;

Sae bonny did the Hollan boats

Come rowin’ to their han’.

23.

She set her milk-white foot on board,

Cried ‘Hail ye, Domine!’

An’ the Belly Blin was the steerer o’t,

To row her o’er the sea.

24.

Whan she came to Young Bekie’s gate,

She heard the music play;

Sae well she kent frae a’ she heard,

It was his wedding day.

25.

She’s pitten her han’ in her pocket,

Gin the porter guineas three;

‘Hae, tak ye that, ye proud porter,

Bid the bride-groom speake to me.’

1126.

O whan that he cam up the stair,

He fell low down on his knee:

He hail’d the king, an’ he hail’d the queen,

An’ he hail’d him, Young Bekie.

27.

‘O I’ve been porter at your gates

This thirty years an’ three;

But there’s three ladies at them now,

Their like I never did see.

28.

‘There’s ane o’ them dress’d in red scarlet,

And twa in dainty green,

An’ they hae girdles about their middles

Woud buy an earldome.’

29.

29.1 ‘bierly,’ stately.

Then out it spake the bierly bride,

Was a’ goud to the chin:

‘Gin she be braw without,’ she says,

‘We’s be as braw within.’

30.

Then up it starts him, Young Bekie,

An’ the tears was in his ee:

‘I’ll lay my life it’s Burd Isbel,

Come o’er the sea to me.’

31.

O quickly ran he down the stair,

An’ whan he saw ’twas she,

He kindly took her in his arms,

And kiss’d her tenderly.

32.

‘O hae ye forgotten, Young Bekie

The vow ye made to me,

Whan I took ye out o’ the prison strong

Whan ye was condemn’d to die?

1233.

‘I gae you a steed was good in need,

An’ a saddle o’ royal bone,

A leash o’ hounds o’ ae litter,

An’ Hector called one.’

34.

It was well kent what the lady said,

That it wasnae a lee,

For at ilka word the lady spake,

The hound fell at her knee.

35.

‘Tak hame, tak hame your daughter dear,

A blessing gae her wi’,

For I maun marry my Burd Isbel,

That’s come o’er the sea to me.’

36.

‘Is this the custom o’ your house,

Or the fashion o’ your lan’,

To marry a maid in a May mornin’,

An’ send her back at even?’

Text.— The Percy Folio is the sole authority for this excellent ballad, and the text of the MS. is therefore given here literatim, in preference to the copy served up ‘with considerable corrections’ by Percy in the Reliques. I have, however, substituted a few obvious emendations suggested by Professor Child, giving the Folio reading in a footnote.

The Story is practically identical with that of Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard; but each is so good, though in a different vein, that neither could be excluded.

The last stanza narrates the practice of burning a cross on the flesh of the right shoulder when setting forth to the Holy Land—a practice which obtained only among the very devout or superstitious of the Crusaders. Usually a cross of red cloth attached to the right shoulder of the coat was deemed sufficient.

1.

God! let neuer soe old a man

Marry soe yonge a wiffe

As did old Robin of Portingale!

He may rue all the dayes of his liffe.

2.

2.1 ‘Lin,’ a stock ballad-locality: cp. Young Bekie, 5.4.

Ffor the Maior’s daughter of Lin, God wott,

He chose her to his wife,

& thought to haue liued in quiettnesse

With her all the dayes of his liffe.

143.

They had not in their wed bed laid,

Scarcly were both on sleepe,

But vpp she rose, & forth shee goes

To Sir Gyles, & fast can weepe.

4.

Saies, ‘Sleepe you, wake you, faire Sir Gyles

Or be not you within?’

.....

.....

5.

5.3 ‘vnbethought.’ The same expression occurs in two other places in the Percy Folio, each time apparently in the same sense of ‘bethought [him] of.’

‘But I am waking, sweete,’ he said,

‘Lady, what is your will?’

‘I haue vnbethought me of a wile,

How my wed lord we shall spill.

6.

6.1,3 ‘Four and twenty’: the Folio gives ‘24’ in each case.

‘Four and twenty knights,’ she sayes,

‘That dwells about this towne,

Eene four and twenty of my next cozens,

Will helpe to dinge him downe.’

7.

With that beheard his litle foote page,

As he was watering his master’s steed,

Soe .....

His verry heart did bleed;

8.

8.1 ‘sikt,’ sighed. The Folio reads sist.

He mourned, sikt, & wept full sore;

I sweare by the holy roode,

The teares he for his master wept

Were blend water & bloude.

159.

With that beheard his deare master

As in his garden sate;

Sayes, ‘Euer alacke, my litle page,

What causes thee to weepe?

10.

’Hath any one done to thee wronge,

Any of thy fellowes here?

Or is any of thy good friends dead,

Which makes thee shed such teares?

11.

11.1, 12.1 The Folio reads bookes man; but see 15.1

‘Or if it be my head kookes man

Greiued againe he shalbe,

Nor noe man within my howse

Shall doe wrong vnto thee.’

12.

‘But it is not your head kookes man,

Nor none of his degree,

But or tomorrow ere it be noone,

You are deemed to die;

13.

‘& of that thanke your head steward,

& after your gay ladie.’

‘If it be true, my litle foote page,

Ile make thee heyre of all my land.’

14.