Project Gutenberg's The Delta of the Triple Elevens, by William Elmer Bachman

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Delta of the Triple Elevens

The History of Battery D, 311th Field Artillery US Army,

American Expeditionary Forces

Author: William Elmer Bachman

Release Date: January 28, 2007 [EBook #20468]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DELTA OF THE TRIPLE ELEVENS ***

Produced by David Edwards, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This book was produced from scanned images of public

domain material from the Google Print project.)

[Transcriber's notes: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected

(e.g. gunnner for gunner), recurrent mispelling of the author haven't

(e.g. Montlucon for Montluçon, canvass for canvases, incidently for

incidentally, paraphanelia for paraphernalia, calesthenics for

calisthenic, etc...).

Page 20: The word "by" has been changed to "from" (partially sheltered

from the Southern sun).

Page 84: The spelling of Sommbernont has been changed to Sombernon.

Page 101: The word casual has been changed to casualty

(sent him home as a casualty).

Page 126: It is not clear if the printed word is trained or roamed

(where he last trained/roamed).

Definitions:

Cootie: Noun US: a head-louse (Macquarie Online Dictionnary - Book

of slang).]

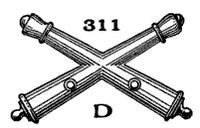

Taken at Benoite Vaux, France, March 14, 1919. Reproduced from the Official Photo taken by the Photographic Section of the Signal Corps, U. S. A.

(p.005)

ARMY RECORD.

Inducted into service at Hazleton, Penna., November 1st, 1917. Sent to Camp Meade, Md., November 2nd, 1917, and assigned as Private to Battery D, 311th Field Artillery. Received rank of Private First Class, February 4th, 1918. Placed on detached service, May 18th, 1918, and assigned as Battery Clerk, First Provisional Battery, Fourth Officers' Training School, Camp Meade. Rejoined Battery D June 27th, 1918, and accompanied outfit to France. Assigned to attend Camouflage School at Camp La Courtine, September 30th, 1918, and qualified as artillery camouflager. On October 3rd, 1918, was registered, through Major A. L. James. Jr., Chief G-2-D, G. H. Q., A. E. F., with the American Press Section, 10 Rue St. Anne, Paris, which registration carried grant to write for publication in the United States. Remained with battery until March 7th, 1919, when selected to attend the A. E. F. University, at Beaune, Cote D'Or. Rejoined battery at St. Nazaire May 1st, 1919. Discharged at Camp Dix, N. J., June 4th, 1919.

"You're in the Army now."

"So this is France!"

Oft I heard these phrases repeated as more and more the realization dawned, first at Camp Meade, Md., and later overseas, that war seemed mostly drudgery with only the personal satisfaction of doing one's duty and that Sunny France was rainy most of the time.

The memory of Battery D, 311th U. S. F. A., will never fade in utter oblivion in the minds of its members. 'Tis a strange fancy of nature, however, gradually to forget many of the associations and circumstances of sombre hue as the silver linings appear in our respective clouds of life in greater radiance as each day finds us drifting farther from ties of camp life.

Soldiers, who once enjoyed the comradeship of camp life, where they made many acquaintances and mayhap friends, are now scattered in all walks of civilian life. While their minds are yet alive with facts and figures, time always effaces concrete absorptions. The time will come when a printed record of Battery D will be a joyous reminder.

With these facts in mind I have endeavored to set forth a history of the events of the battery and the names and addresses of those who belonged.

The records are true to fact and figure, being compilations of my diaries, note-books and address album, all verified with utmost care before publication.

In future years when the ex-service men and their friends glance over this volume, if a moment of pleasant reminiscence is added, this book will have fully served its purpose.

William Elmer Bachman,

1920. Hazleton, Penna.

An effort has been made in this volume to state as concisely and clearly as possible the main events connected with the History of Battery D.

To recount in print every specific incident connected with the life of the organization, or to attempt a military biographical sketch of every battery member, would require many volumes.

My soldier-comrade readers will, no doubt, recall many instances which could have been included in this volume with marked appropriateness.

The selection of the material, however, has been with utmost consideration and for the expressed purpose of having the complete narrative give the non-military reader a general view of the conditions and experiences that fell to the lot of the average unit in the United States Army in service in this country and overseas.

Grateful acknowledgment is due to those who aided in the verification of all material used. Many of the battery members made suggestions that have been embodied in the text.

To A. Ernest Shafer, D. C., and Conrad A. Balliet, of Hazleton, Penna., belongs credit for information supplied covering periods when the author was on detached service from the battery. To Dr. Shafer acknowledgment is also due for the use of photographs from which a number of the illustrations have been reproduced.

From Prof. Fred H. Bachman, C. A. C., of Hazleton, Penna., who read over the manuscript, many valuable suggestions were received.

W. E. B.

Hazleton, Penna., 1920.

CHAPTER I.

World Events -- The Nucleus -- Declaration of War. U. S. Joins -- Selective Service Plans.

CHAPTER II.

Selection of Camp Meade Site -- Cantonment Construction Building Progresses -- Home Leaving Preparations.

CHAPTER III.

Officers at Fort Niagara -- Assignment of Officers Barrack org. -- New Soldiers Arrive.

CHAPTER IV.

Description of Barracks -- A Day's Routine -- Getting Catalogued -- Inoculations and Drills -- Soldiers Arrive and Leave.

CHAPTER V.

First Non-Commissioned Personnel -- Effects of Transfers -- Schools -- Hikes -- Athletics -- Idle Hours.

CHAPTER VI.

Holiday Season Approaches -- Thanksgiving Feast Practice Marches -- Barrack 0103 -- Christmas 1917.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII. (p. 009)

Formal Retreat -- Quarantine -- Celebration -- Rumors. Baltimore Parade -- West Elkridge Hike.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

Set-Sailing -- Coastland Appears -- Halifax Harbor -- Convoy Assembles.

CHAPTER XI.

Ocean Journey Starts -- Transport Life -- Sub Scares. Destroyers Delayed -- Battle With Subs.

CHAPTER XII.

Barry, South Wales -- Parade -- His Majesty's Letter. English Rail Journey.

CHAPTER XIII.

Crowded Tenting -- English Mess -- A Rainy Hike. Off for Southampton -- Flight Across the Channel.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

Racial Difficulties -- French Billets -- Impressions. The Gartempe.

CHAPTER XVI.

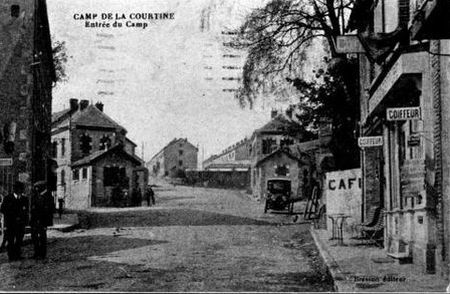

To La Courtine -- French Artillery Camp -- Russian Revolt -- Life on the Range -- Sickness -- Casualties.

CHAPTER XVII. (p. 010)

November 7th -- November 11th -- Celebration -- Farewell Banquet -- Ville Sous La Ferte -- Fuel Details -- Delayed Departure.

CHAPTER XVIII.

Mud and Rats -- Historic Monteclair -- Thanksgiving 1918 -- Candle Mystery -- Sick Horses Arrive.

CHAPTER XIX.

Belgian Trip Proposed -- 100 Volunteers -- Remount 13 -- Convoying Mules -- Christmas 1918.

CHAPTER XX.

Anxious to Join Division -- First Service Stripe -- A. E. F. Leave Centers -- Mounted Hikes -- Overland to Benoite Vaux.

CHAPTER XXI.

Two Battery Mascots -- Battalion and Regimental Shows -- Division and Corps Shows -- More Personnel Changes -- Maneuvres -- More Sickness and Casualties.

CHAPTER XXII.

Boncourt -- Cirey les Mareilles -- Divisional Review. Camp Montoir -- St. Nazaire -- Edward Luckenbach -- New York -- Camp Dix -- Home.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV. (p. 011)

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

List of Names That Comprised the Sailing List of the U. S. S. Edward Luckenbach.

CHAPTER XXX.

Those Who Gained Commissions--List of Men Transferred to Other Organizations.

CHAPTER XXXI.

CHAPTER XXXII.

CHAPTER XXXIII.

Page

Group Photo of Battery D. 3

William Elmer Bachman. 5

Albert L. Smith. 18

David A. Reed. 22

Perry E. Hall. 39

Sidney F. Bennett. 39

C. D. Bailey. 39

Frank J. Hamilton. 39

Third Class French Coach. 57

Side-Door Pullman Special. 57

Interior of French Box Car. 57

A Real American Special. 57

Montmorillon Station. 67

Montmorillon Street Scene. 67

Entrance to Camp La Courtine. 81

American Y. M. C. A. at Camp La Courtine. 81

A Battery D Kitchen Crew. 88

Group of Battery D Sergeants. 88

Battery D on the Road. 99

Aboard The Edward Luckenbach. 99

At Bush Terminal. 99

Serving Battery Mess Along the Road. 110

Battery D on the Road. 110

Lorraine Cross. 117

Joseph A. Loughran. 124

Cemetery at La Courtine. 124

Horace J. Fardon. 129

Grave of William Reynolds. 129

Barrack at Camp La Courtine. 129

Official records in the archives of the War Department at Washington will preserve for future posterity the record of Battery D, of the 311th United States Field Artillery.

In those records there is written deep and indelibly the date of May 30th, 1919, as the date of Battery D's official demobilization. The history of Battery D, therefore, can be definitely terminated, but a more difficult task is presented in establishing a point of inception.

The development of Battery D was gradual--like a tiny stream, flowing on in its course, converging with the 311th Regimental, 154th Brigade, and 79th Division tides until it reached the sea of war-tossed Europe; there to flow and ebb; finally to lose its identity in the ocean of official discharge.

The Egyptians of old traversed the course of their river Nile, from its indefinite sources along the water-sheds of its plateaux and mountains, and, upon arriving at its mouth they found a tract of land enclosed by the diverging branches of the river's mouth and the Mediterranean seacoast, and traversed by other branches of the river. This triangular tract represented the Greek letter Δ "Delta," a word which civilization later adopted as a coinage of adequate description.

Fine silt, brought down in suspension by a muddy river and deposited to form the Delta when the river reaches the sea, accumulates from many sources.

In similar light the silt of circumstances that resulted in the formation of the Delta of the Triple Elevens, accumulated from many sources, the very nucleus transpiring on June 28, 1914, when the heir to the Austrian throne, the archduke of Austria, and his wife, were assassinated at Sarajevo, in the Austrian province of Bosnia, by a Serbian student.

Austria immediately demanded reparation from Serbia. Serbia declared herself willing to accede to all of Austria's demands, but refused to sacrifice her national honor. Austria thereby took the pretext to renew a quarrel that had been going on for centuries.

Long diplomatic discussions resulted--culminating on July 28, 1914, with a declaration of war by Austria against Serbia. This, so to speak, opened the flood-gates, letting loose the mighty river of blood and slaughter that flowed over all Europe.

The (p. 014) days that followed added new sensations and thrills to every life. The river of war flowed nearer our own peaceful shores as the days passed and the news dispatches brought us the intelligence of Germany's declaration of relentless submarine warfare and the subsequent announcement of the United States' diplomatic break with Germany.

Momentum was gained as reports of disaster and wilful acts followed with increasing rapidity. The sinking of American vessels disclosed a ruthlessness of method that was gravely condemned in President Wilson's message of armed-neutrality, only to be followed by acts of more wilful import--finally evoking the proclamation, April 6, 1917, declaring a state of war in existence between the United States and the Imperial German government.

Clear and loud war's alarm rang throughout the United States. All activity centered in the selection of a vast army to aid in the great fight for democracy. Plans were promulgated with decision and preciseness. On June 5th, 1917, ten millions of Americans between the ages of 21 and 31 years, among the number being several hundred who were later to become associated with Battery D, of the 311th F. A., registered for military service.

The war department issued an order, July 13, 1917, calling into military service 678,000 men, to be selected from the number who registered on June 5th. Days of conjecture followed. Who would be called first?

July 20th brought forth the greatest lottery of all time. The drawing of number 258 by Secretary of War Newton D. Baker started the list of selective drawings to determine the order of eligibility of the young men in the 4,557 selective districts in the United States.

War's preparations moved rapidly. Selective service boards, with due deliberation, made ready for the organization of the selective contingents. While the boards toiled and the eligible young men went through the process of examination, resulting in acceptance or rejection, officials of the war department were planning the camps.

Battery D and the 311th Field Artillery were in the stages of organization but plans of military housing had to mature before the young men who were to form the organization, could be inducted into service, thereby bringing to official light The Delta of the Triple Elevens.

On that eventful day in 1914, when the war clouds broke over Europe, the farmers of Anne Arundel county, Maryland, in the then peaceful land of the United States, toiled with their ploughshares under the glisten of the bright sun; content with their lot of producing more than half of the tomato crop of the country; content to harvest their abundant crops of strawberries and cucumbers and corn, to say nothing of the wonderful orchards of apples and pears, and not forgetting the wild vegetation of sweet potatoes.

The peaceful, pastoral life in the heart of Maryland, however, was destined to be disturbed. A vast American army was needed and the vast army, then in the process of organization, needed an abode for training. Battery D and the 311th Field Artillery was organized on paper soon after the call for 678,000 selected service men was decided upon. The personnel of the new organization was being determined by the selective service boards. Officers to command the organization were under intensive instruction at Fort Niagara, New York. All that was needed to bring the organization into official military being was a point of concentration.

The task of locating sites for the sixteen army cantonments, decreed to birth throughout the United States, presented many difficulties. What could be more natural, however, than the fertile farm lands of Anne Arundel county, almost within shadow of the National Capital, to be selected as the site of a cantonment to be named after General George Gordon Meade?

Territory in the immediate vicinity of Admiral and Disney was the ideal selection: ideal because the territory is only eighteen miles from Baltimore, the metropolis of the South; one hundred miles from Philadelphia, the principal city of the State which was to furnish most of the recruits; and twenty-two miles from Washington, the Capital of the Nation.

Situated between the heart of the South and the heart of the Nation, Camp Meade is easily accessible by rail. Ease of access through mail-line facilities, was a necessity for transportation of building materials and supplies before and during construction. The same facilities furnished the transportation for the large bodies of troops that were sent to and from the camp; also assured the cantonment its daily supply of rations.

Admiral (p. 016) Junction furnished adequate railroad yard for the camp. The Baltimore and Ohio railroad station is at Disney, about one-half mile west of Admiral; while the Pennsylvania Railroad junction on the main line between Baltimore and Washington is at Odenton, about one and one-half miles east of Admiral. Naval Academy Junction is near Odenton and is the changing point on the electric line between the two chief cities. The magic-like upbuild of the cantonment, moreover, was the signal for the extension of the electric line to encircle the very center of the big military city, thus adding an additional link of convenience.

Camp Meade having been officially decided upon as the home of the 79th Division, a sanitary engineer, a town planner, and an army officer, representing the commanding general, were named to meet on the ground, where they inspected the location, estimated its difficulties, and then proceeded to make a survey in the quickest way possible, calling upon local engineers for assistance and asking for several railroad engineering corps.

The town-planner, or landscape architect, then drew the plans for the cantonment, laying it out to conform with the topography of the location and taking into consideration railroad trackage, roads, drainage, and the like. Given the site it was the job of the town-planner to distribute the necessary buildings and grounds of a typical cantonment as shown in type plans.

The general design for the camp was prepared by Harlan P. Kelsey, of "city beautiful" fame, who was one of the experts called on by the war department to aid the government in the emergency of preparing for war.

After the town-planner came Major Ralph F. Proctor, of Baltimore, Md., who on July 2nd, 1917, as constructing quartermaster, look charge of the task of building the cantonment. Standing on the porch of a little frame-house situated on a knoll, set in the midst of a pine forest, Major Proctor gave the order that set saw and axe in motion; saws and axes manned by fifteen thousand workmen, consecrated to the task of throwing up a war-time city in record time.

Chips flew high and trees were felled and soon the knoll belched forth a group of buildings, fringed by the pine of the forest--to be dedicated as divisional headquarters--around which, with speed none-the-less magic-like, land encircling was cleared and buildings and parade grounds sprang up in quick succession.

The (p. 017) dawn of September month saw over one thousand wooden barracks erected on the ground, most of which were spacious enough to provide sleeping quarters for about two hundred and fifty men; also hundreds of other buildings ready to be occupied for administrative purposes.

While workmen of all trades diligently plied their hands to the work of constructing the cantonment, hundreds of young men were getting ready to leave their homes on September 5th, as the van-guard of the 40,000 who were in the course of time to report to Camp Meade for military duty. The cantonment, however, was not fully prepared to receive them and while the first contingent of Battery D men were inducted into service on September 5th, the cantonment was not deemed sufficiently ready to receive them until almost two weeks later.

ARMY RECORD.

Discharged from the National Guard of Pennsylvania, First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry, after seven years of service, to enter First Officers' Training Camp at Camp Niagara, N. Y., May 8th, 1917. Commissioned Captain, Field Artillery Reserve, August 15th, 1917, and ordered to report to Camp Meade, Md., August 29th, 1917. Placed in command of Battery D, 311th Field Artillery. Accompanied battery to France and remained with outfit until ordered to Paris on temporary duty in the Inspector General's Department, February, 1919. Rejoined regiment to become Regimental Adjutant May 6th, 1919. Discharged at Camp Dix, N. J., May 30th, 1919.

At Fort Niagara, situated on the bleak shores of the River Niagara, New York State, the nucleus of the first commissioned personnel of Battery D assembled, after enlistment, during the month of May, 1917, and began a course of intensive training at the First Officers' Training School, finally to be commissioned on August 15th in the Field Artillery Reserve.

On August 13th, pursuant to authority contained in a telegram from the Adjutant General of the Army, a detachment of the Reserve Officers from the Second Battery at Fort Niagara were ordered to active duty with the New National Army, proceeding to and reporting in person not later than August 29th to the Commanding General, Camp Meade, for duty.

A day's brief span after their arrival at Camp Meade--while the officers, who were the first of the new army units on the scene of training, were busily engaged in dragging their brand new camp paraphernalia over the hot sands of July-time Meade,--the dirt and sand mingling freely with the perspiration occasioned by the broiling sun,--to their first assigned barracks in B block, an order arrived on August 30th, assigning the officers to the various batteries, headquarters, supply company, or regimental staff of the 311th Field Artillery, that was to be housed in O block of the cantonment.

Captain Albert L. Smith, of Philadelphia, Pa., was placed in command of Battery D. Other assignments to Battery D included: First Lieutenant Arthur H. McGill, of New Castle, Pa.; Second Lieutenant Hugh M. Clarke, of Pittsburgh, Pa.; Second Lieutenant Robert S. Campbell, of Pittsburgh, Pa.; Second Lieutenant Frank F. Yeager, of Philadelphia, Pa.; Second Lieutenant Frank J. Hamilton, of Philadelphia, Pa.; Second Lieutenant Berkley Courtney, of Fullerton, Md.

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles G. Mortimer was placed in command of the regiment on August 28, 1917. He remained in command until January 17, 1918, when Colonel Raymond W. Briggs was assigned as regimental commander. Both are old army men and were well trained for the post of command. On March 31st, Col. Briggs, who had been in France and returned to take command of the 311th, was again relieved of command, being transferred to another outfit to prepare for overseas duty a second time. Lieut. Col. Mortimer had charge until (p. 020) June 10th, 1918, when he was promoted to Colonel, remaining in command until the regiment was mustered out of service.

Major David A. Reed, of Pittsburgh, Pa., was placed in command of the 2nd Battalion of the 311th at organization and remained with the outfit until put on detached service in France after the signing of the armistice. Major Herbert B. Hayden, a West Point cadet, was assigned to the command of the 1st Battalion of the regiment. When time to depart for overseas came he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment. Capt. Wood, of Battery A, was made Major of the 1st Battalion and First-Lieut. Arthur McGill, of Battery D, was placed in command of Battery A. Later he was given the rank of captain.

Major-General Joseph E. Kuhn was commanding officer of the 79th Division and Brigadier General Andrew Hero, Jr., commanded the 154th Field Artillery Brigade.

"O" block, in the plan of Camp Meade, was designated as the training center of the 311th Field Artillery and barrack No. 19 was the shelter selected for Battery D.

Barrack 019 was situated in a small glade of trees which fringed the edge of the horse-shoe curve that the general plan of cantonment construction assumed. The spurs of the great horse-shoe were at Disney and Admiral. The blocks of regimental areas starting at Disney, designated by A block, followed the horse-shoe, encircling at the base hospital in alphabetical designation. "N" and "O" blocks nestled in a glade of trees, partially sheltered from the Southern sun, just around the bend in the curve of the road from the base-hospital. "Y" block formed the other end of the spur at Admiral--while divisional headquarters rested on the knoll in the center of the horse-shoe.

It was at "O" block the newly assigned officers established themselves and made ready to receive the first influx of the selected personnel. Blankets and cots and barrels and cans and kitchen utensils began to arrive by the truck load and the officers in feverish haste divided the blankets, put up as many cots as they could, and established some semblance of order in the mess hall. They were pegging diligently at their tasks when the first troop trains pulled in at Disney on September 19th and unloaded the first detachment of future soldiers.

Scenes of home-leaving and farewells to the home-folks and loved ones, which first transpired on September 19th, to be repeated with similarity (p. 021) as subsequent quotas of recruits entrained for military service, were of too sacred a nature to attempt an adequate description.

What might have been the thoughts of the individual at the breaking of home-ties and during the long, tiresome railroad journey to Camp Meade, were buried deep in the heart, to be cherished as a future memory only. Personal griefs were hidden as those seven hundred young men in civilian clothes stepped from the train at Disney, grasped their suit case, box, or bundle, firmly and set out on the mile and a quarter hike through the camp--past divisional headquarters; perspiring freely under the heat of the setting sun. It was with an appearance of carelessness and humor they jaunted along, singing at times, "You're in the Army Now"--finally to breast the rise of the hill previous to "O" block, the descent thereof which was to mark the first stage of their transformation from civilian to soldier.

Descent of the hill lead down to a sandy square in front of a long building that housed regimental headquarters. After, what seemed like hours to the recruits lined-up, roll of the seven hundred was called, divisions made, and the first quota of Battery D was marched to 019.

ARMY RECORD.

Enlisted in the service of the United States Army, May 11th, 1917, and received commission as Major at the First Officers' Training Camp, Fort Niagara. N. Y. Was ordered to Camp Meade. Md., August 29th, 1917, and placed in command of the Second Battalion, 311th Field Artillery. Accompanied the outfit to France. On detached service with the Interallied Armistice Commission, Spa, Belgium, from November 20th, 1918, to February 1st, 1919. Was awarded the French Legion of Honor medal April 4th, 1919. Discharged February 26th, 1919. Got commission as Lieutenant-Colonel in the Field Artillery Reserve, August 6th, 1919.

Iron-bound was the rule. You couldn't escape it. Every selected man who entered Camp Meade had to submit. Of course, the new recruits were given a dinner shortly after their arrival--but not without first taking a bath.

019, like all the other barracks of the cantonment, was a wooden structure, 150 x 50 feet, two stories in height. Half of the first floor housed the kitchen and dining hall while the remainder of the building was given over to sleeping quarters, with the exception of a corner set apart as the battery office and supply room--a most business-like place, from which the soldier usually steered shy, unless he wanted something, or had a kick to register about serving as K. P., or on some other official detail when he remembered having done a turn at the said detail just a few days previous.

The rows of army cots and army blankets presented a different picture to the new soldier at first appearance, in comparison to the snug bed room, with its sheets and comfortables, that remained idle back home. The first night's sleep, however, was none-the-less just, the same Camp Meade cot furnishing the superlative to latter comparisons when a plank in a barn of France felt good to weary bones.

Before rolling-in the first night every one was made acquainted with reveille, but no one expected to be awakened in the middle of the night by the bugle calling, "I Can't Get 'Em Up, etc., etc." Could it be a mistake? No, indeed, it was 5:15 a. m., and the soldier was summoned to roll-out and prepare for his first real day as a soldier.

"Get dressed in ten minutes and line up outside in battery-front for roll call," was the first order of the day. Then followed a few precious moments for washing up in the Latrine, which was a large bath house connected with the barrack.

Before the call, "Come and Get It" was sounded the more ambitious of the recruits folded their blankets and tidied up their cots. When mess call was sounded but few had to be called the second time.

The hour of 7:30 was set for the day's work to begin, the first command of which was "Outside, and Police-Up." In the immediate vicinity of the battery area there was always found a multitude of cigarette butts, match stems, chewing gum wrappers, and what not, and (p. 024) the place had to be cleaned up every morning. If Battery D had saved all the "snips" and match stems they policed-up and placed them end by each the Atlantic could have been spanned and the expense of the Steamship Morvada probably saved.

The first few weeks of camp life were not strenuous in the line of military routine. Detail was always the long-suit at Camp Meade. During the first few days at camp if the new recruit was lucky enough to be off detail work, the time was usually employed in filling out qualification cards, identification cards; telling your family history; making application for government insurance; subscribing to Liberty bonds; telling what you would like to be in the army; where you wanted your remains shipped; getting your finger-prints taken, and also getting your first jab in the arm which gave the first insight into a typhoid inoculation.

When a moment of ease presented itself during the life examination--the supply sergeant got busy and started to hand out what excess supplies he had and, in the matter of uniforms, of which there was always an undercess, measurements were taken with all the exactness and precision befitting a Fifth Avenue tailoring establishment. Why measurements were ever taken has ever remained a mystery, because almost every soldier can remember wearing his civilian clothes thread-bare by the time the supply sergeant was able to snatch up a few blouses and trousers at the quartermasters. And these in turn were passed out to the nearest fits. It was a case of line-up and await your turn to try and get a fit, but a mental fit almost always ensued in the game of line-up for this and line-up for that in the army.

After being enmeshed in such a coil of red tape all of one whole day, 5 o'clock sounded Retreat, when instruction was given on how to stand at ease; how to assume the position of "parade-rest"; then, to snap into attention.

Evening mess was always a joyful time, as was the evening, when the soldier was free to visit the Y. M. C. A. and later the Liberty Theatre, or partake of the many other welfare activities that developed in the course of time. From the first day, however, 9:45 p. m. was the appointed hour that called to quarters, and taps at 10 o'clock each night sounded the signal for lights out and everybody in bunk.

The inoculations were three in number, coming at ten day intervals. When it came time for the second "jab", the paper work was well under way and the call was issued for instruction on the field of drill (p. 025) to begin. Many a swollen arm caused gentle memories as part of each day was gradually being given over to, first calesthenics, then to a knowledge of the school of the soldier. The recruit was taught the correct manner of salute, right and left face, about face, and double time.

Newly designated sergeants and corporals were conscripted to the task of squad supervision and many exasperating occasions arose when a recruit got the wrong "foots" in place and was commanded to "change the foots."

Meals for the first contingent of pioneer recruits ranged from rank to worse, until the boys parted company with their French civilian cooks and set up their own culinary department with Sergeant Joseph A. Loughran, of Hazleton. Pa., in charge. August H. Genetti and Edward Campbell, both of Hazleton. Pa.; George Musial, of Miners Mills, Pa., and Charles A. Trostel, of Scranton, Pa., were installed as the pioneer cooks. By this mess change the soldiers who arrived in later contingents were served more on the American plan of cooking.

On September 21st, 1917, came the second section of the selected quotas, bringing more men to Battery D. Their reception varied little from the first contingent's, with the exception that the first arrived soldiers were on the ground to offer all kinds of advice--some of the advice almost scaring the new men stiff.

The future contingents were greeted with a more completed camp, because the construction work was continued many weeks after the soldiers began to arrive. And, in passing, it might be recorded, that the construction work continued long after the contractors finished their contracts. Military-like it was done by "detail."

On October 4th and 5th more recruits arrived and then on November 2nd another large contingent arrived and was assigned to Battery D. This was the last selected quota to be received directly into the regiment, for, thereafter, the Depot Brigade received all the newly selected men.

Almost all of the recruits of the first few contingents, including the delegation that arrived on November 2nd, came from Eastern Pennsylvania, from the Hazleton, Scranton, and Wilkes-Barre districts of the Middle Anthracite Coal Fields. The delegation that arrived on November 2nd was accompanied by St. Ann's Band, of Freeland, Pa. The band remained in camp over the week-end, during (p. 026) which time a number of concerts were rendered. The band was highly praised for its interest and patriotism.

All the men originally assigned to Battery D were not to remain with the organization throughout their military life. On October 15th, 1917, Battery D lost about half of its members in a quota of 500 of the regiment who were transferred to Camp Gordon, Georgia. On November 5th, two hundred more were transferred from the regiment and on February 5th, seventy-two left to join the Fifth Artillery Brigade at Camp Leon Springs, Texas.

The latter part of May Battery D received a share of 931 recruits sent to the regiment from the 14th Training Battalion of the 154th Depot Brigade at Camp Meade. On July 2nd and 3rd, one hundred and fifty more came to the regiment from the Depot Brigade; 540 from Camp Dix, N. J., and Camp Upton, N. Y.; fifty from the aviation fields of the South; and a quota from the Quartermaster Corps in Florida.

Many of these did not remain long with the battery. In the latter part of June and the beginning of July the battery was reduced to nearly one-half and the March replacement draft to Camp Merritt took thirty-two picked men from the regiment. This ended the transfers. While in progress, the transfers rendered the regiment like unto a Depot Brigade. Over four thousand men passed through the regiment, five hundred of the number passing through Battery D.

"Dress it up!"

And--

"Make it snappy!"

"One, two, three, four."

"Now you've got it!"

"That's good. Hold it!"

"Hep."

Battery D had lots of "pep" during the days of Camp Meade regime.

First Sergeant William C. Thompson, of Forest, Mississippi, kept things lively for the first few months with his little whistle, followed by the command, "Outside!"

Merrill C. Liebensberger, of Hazleton, Penna., served as the first supply sergeant of the battery. David B. Koenig, also of Hazleton, Penna., ranking first as corporal and later as sergeant, was kept busy with office work, acting in the capacity of battery clerk. Lloyd E. Brown, of East Richmond, Indiana, served as the first instrument sergeant of the battery. John M. Harman, of Hazleton, Penna., was the first signal-sergeant to be appointed.

It might be remarked in passing that Messrs. Thompson, Liebensberger, and Harman were destined for leadership rank. Before the outfit sailed for overseas all three had gained application to officers' training schools, and were, in the course of time, commissioned as lieutenants. Battery Clerk Koenig continued to serve the outfit in an efficient manner throughout its sojourn in France. Instrument-Sergeant Brown early in 1918 answered a call for volunteers to go to France with a tank corps. While serving abroad he succumbed to an attack of pneumonia and his body occupies a hero's resting place in foreign soil.

A wonderful spirit was manifested in the affairs of Battery D despite the fact that the constant transfer of men greatly hampered the work of assembling and training a complete battery for active service in France. Men who spent weeks in mastering the fundamentals of the soldier regulations were taken from the organization, to be replaced (p. 028) by civilians, whereby the training had to start from the beginning. This caused many changes in plans, systems, and policies. Rejections were also made for physical disabilities.

For the greater part of the Camp Meade history of the battery, the organization lacked sufficient men to perform all the detail work. Thus days and days passed without any military instruction being imparted.

Instruction in army signalling by wigwag and semaphore was started whenever a squad or two could be spared from the routine of detail. Then followed instruction on folding horse blankets, of care of horses and harness, and lessons in equitation, carried out on barrels and logs.

Stables and corrals were in the course of construction. By the time snow made its appearance in November horses were received, also more detail.

First lessons in the duties of gun-crews and driving squads were also attempted. Matériel was a minus quantity for a long time, wooden imitations sufficing for guns until several 3.2's were procured for the regiment. Later on the regiment was furnished with five 3-inch U. S. field pieces. Training then assumed more definite form. For weeks and weeks the gun crews trained without any prospects of ever getting ammunition and firing actual salvos.

Learning to be a soldier also developed into a process of going to school. Men were assigned to attend specialty classes. Schools were established for gunners, schools for snipers, schools for non-commissioned officers. Here it might be stated that the first non-coms envied the buck-privates when it came to attending non-commissioned officers' school one night a week when all the bucks were down enjoying the show at the Y hut or the Liberty Theatre.

Schools were started for all kinds of special and mechanical duty men; schools to teach gas-defense; buzzer schools; telephone schools; smoke-bomb and hand-grenade courses; and map-reading and sketching schools. Sergeant Earl H. Schleppy, of Hazleton, Penna., who assisted in the battery office work before he was appointed supply-sergeant, developed extra lung capacity while the various schools were in progress. It became his duty to assemble the diverse classes prior to the start of instruction. He was kept busy yelling for the soldiers to assemble for class work.

It soon developed in the minds of the men that war-time military life was mostly drudgery with only the personal satisfaction of doing one's (p. 029) duty. Hardships and drudgery, however, did not mar the ambition of the soldier for recreation. Baltimore and Washington were nearby and passes were in order every Saturday to visit these cities.

Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, during the first few months of camp life, were off-periods for the soldiers, but later Wednesday afternoon developed as an afternoon of sport and the men took keen interest in the numerous athletic interests which were promoted.

On Tuesday, November 6th, a half-holiday was proclaimed and Election Day observed throughout the camp. The soldiers who availed themselves of the opportunity of marking the complicated soldier ballot that was provided, cast the last vote, in many instances, until after their official discharge.

Daily hikes were on the program in the beginning to develop a hardness of muscle in the new soldiers. Lieut. Robert Campbell was in charge of the majority of the daily hikes at the off-set. His hobby was to hike a mile then jaunt a mile. When it came to long distant running Lieut. Campbell was on the job. He made many a soldier sweat in the attempt to drag along the hob-nailed field shoes on a run. Hikes later were confined to Wednesday afternoon.

Battery D always put up a good showing in the numerous athletic contests. On Saturday, November 10th, the Battery won the second banner in the Inter-Battalion Meet; in celebration of which a parade and demonstration was held on the afternoon of the victory day.

Music was not lost sight of. The boys of Battery D collected the sum of $175 for the purchase of a piano for barrack 019. Phil Cusick, of Parsons, Penna., was the one generally sought out to keep the ivories busy. November 19th witnessed the first gathering together of the regiment on the parade grounds for a big song fest under the leadership of the divisional music director. Battery and battalion song jubilees were conducted at intervals in the O block Y hut.

Towering like a giant over the uniform type of barrack and buildings at Camp Meade, stood a large observation tower, situated on what was known as the "plaza," the site of divisional headquarters. A general panorama from this tower was an inspiring sight. Radiating from the plaza, extending for several miles in any direction the gaze was focused, there appeared the vista of the barracks of the troops together with the sectional Y. M. C. A.'s canteens, stables, corrals and other supply and administration buildings; also the interposing, spacious drill fields.

The beauty of this scene was enhanced by the mantle of snow that often garbed it during the winter mouths. To see a city of 40,000 in such uniformity as marked the cantonment construction; with its buildings covered with snow; the large drill fields spread with a blanket of snow; and, a snow storm raging--is a tonic for any lover of nature.

On the night of Wednesday, November 28th, the first snow greeted the new soldiers at Camp Meade. The ground, robed in white, breathed the spirit of the approaching holiday season. The coming of Thanksgiving found discussion in 019 centered on the subject of passes to visit "home."

On November 24th fifteen of D battery men were granted forty-eight hour leaves and departed for their respective homes. All the officers remained in camp and planned with the men to enjoy the holiday.

The Thanksgiving dinner enjoyed by Battery D was one never to be forgotten in army life. Mess-Sergeant Al Loughran and the battery cooks, ably championed by the K. P.'s, worked hard for the success of the Thanksgiving battery dinner. Battalion and battery officers dined with the men, the noon-mess being attendant by the following menu:

Oyster Cocktail

Snowed Potatoes Roast Turkey Turkey Filling

Cranberry Sauce Celery Peas

Oranges Apples Candy Cake Nuts

Bread Butter Coffee

Mince Pie

Cigarettes Cigars

Sweet (p. 031) dreams of this dinner often haunted the boys when "bully-beef" was the mainstay day after day many times during the sojourn in France.

After the dinner officers and battery members adjourned to the second floor of the barrack where battery talent furnished an entertainment, consisting of instrumental and vocal numbers and winding up with several good boxing bouts. Barney McCaffery, of Hazleton, Penna., a professional pugilist, was the pride of the battery in the ring.

Corporal Frank McCabe, of Parsons, Penna., was one of the real comedians of the battery. His character impersonations enlivened many an evening in 019. Every member of the outfit was deeply grieved when Corporal McCabe was admitted to the base-hospital the latter part of January, suffering with heart trouble. On January 24th at 8:20 p. m., Corporal McCabe died. This first casualty of the battery struck a note of sympathetic appeal among the battery members. A guard of honor from the battery accompanied the body to Parsons where interment was made with military honors.

After Thanksgiving Battery D settled down to an intensive schedule of instruction. Days of rain, snow, and zero weather followed, making the routine very disagreeable at times, but never acting as a demoralizer. Days that could not be devoted to out-door work were used to advantage for the schedule of lecture periods during which the officers conducted black board drills to visualize many of the problems connected with artillery work.

On December 6th, 1917, a series of regimental practice marches were instituted, first on foot, then on mount. The first mounted marches, however, were rather sore-ending affairs, as were the first lessons in equitation. Saddles and bridles were lacking as equipment for many weeks after the receipt of the horses. Mounted drill, riding bare-back, with nothing but a halter chain as a bridle, was the initiatory degree of Battery D's equitation.

Barrack 0103, about half the size and situated in the rear of 019, was completed on December 19th, when a portion of Battery D men were quartered in the new structure, thereby relieving the congestion in 019.

Christmas and New Year's of 1917 furnished another controversy on the question of holiday furloughs. On Saturday, December 15th, inspection was called off and forty men were detailed to bring more (p. 032) horses from the Remount station for use in the battery. The detail completed its task faithfully, the men being happy in the thought that, according to instructions, they had, the night previous, made application for Christmas passes. Gloom greeted the end of the day's horse convoy. Announcement was made that all Christmas pass orders had been rescinded in the camp.

The gloom was not shattered until December 20th, when announcement was made at retreat formation that half of the battery would be allowed Christmas passes and the other half would be given furloughs over New Year's Day. The loudest yell that ever greeted the "dismissed" command at the close of retreat, rent the atmosphere at that time.

More disappointments were in store for the boys before their dreams of a furlough home were realized. Saturday, December 22nd, was decreed a day of martial review at Camp Meade. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker visited the cantonment that day and the review was staged in his honor. Battery D formed with the regiment on the battery street in front of 019 at 1:20 o'clock on the afternoon of the review. The ground was muddy and slushy. The regiment stood in formation until 3:15 o'clock when the march to pass the reviewing stand started. At 4:30 o'clock the review formation was dismissed and the boys dashed back to 019 to get ready to leave on their Christmas furloughs.

It was a happy bunch that left 019 at 5:15 p. m. that day, under the direction of Lieut. Berkley Courtney, bound for the railroad station and home. An hour later the same bunch were seen trudging back to 019. Their happiness had suddenly taken wing. A mix-up in train schedules left them stranded in camp for the night, while the hours of their passes slowly ticked on, to be lost to their enjoyment.

The "get-away" was successfully effected the next morning, Sunday, December 23rd, when the same contingent marched to Disney, reaching the railroad yard at 7:30 o'clock, where they were doomed to wait until 9:15 a. m. until the train left for Baltimore.

More favorable train connections fell to the lot of the New Year's sojourners to the land of "home."

"This is some job."

And the opinion was unanimous when stable detail at Camp Meade was in question, especially during the winter of 1917-18, which the Baltimore weather bureau recorded as the coldest in 101 years. Stable detail at first consisted of five "buck" privates, whose duty it was to take care of "Kaiser," "Hay-Belly," and all the other battery horses for a period of three days.

When on stable detail you arose at 5:45 a. m.; quietly dressed, without lights, went to the stables and breakfasted the animals. If you were a speed artist you might get back in time for your own breakfast.

After breakfast you immediately reported to the stable-sergeant, who was Anthony Fritzen, of Scranton, Penna. The horses were then led to the corral and the real stable duties of the day commenced. In leading the horses through the stable to the corral, the length of your life was dependant upon your ability to duck the hoofs of the ones remaining in the stables.

When it came to cleaning the stables, many a "buck" private made a resolve that in the next war he was going to enlist as a "mule-skinner." Driving the battery wagon bore the earmarks of being a job of more dignity than loading the wagon.

Besides cleaning the stables and "graining-up" for the horses, the day of the stable police was spent in miscellaneous jobs, which Sergeant Fritzen never ran out of.

The stable detail underwent changes as time wore on. A permanent stable man was assigned for every stable and the detail was reduced to three privates.

Stable police was of double import on Saturday mornings, preparatory to the weekly inspection. Every branch and department of military life has a variety of inspections to undergo at periodical times. The inspections keep the boys in khaki on the alert; cleanliness becoming second nature. Nowhere can a vast body of men live bachelor-like as soldiers do and maintain the degree of tidiness and general sanitary healthfulness, as the thorough arm of camp inspection and discipline maintains in the army.

A (p. 034) daily inspection of barracks was in order at Camp Meade. Before the boys answered the first drill formation each morning they did the housework. Everything had to be left spick and span. There was a specific place for everything and everything had to be kept in its place.

With mops and brooms and plenty of water the barracks were given a good scrubbing on Friday afternoons and things put in shape for the Saturday morning inspection. Besides the cleanup features a display of toilet articles and wearing apparel had to be made. When the inspectors made their tour each bunk had to show a clean towel, tooth brush, soap, comb, pair of socks, and suit of underwear. The articles had to be displayed on the bunk in a specific manner.

"Show-Down" inspections were a big feature of the routine. This inspection required the soldier to produce all his wares and equipment for inventory. The supply officer and supply sergeant of the battery made many rounds taking account of equipment that was short, but several more "show-downs" usually transpired before the lacking equipment was supplied.

There was also a field inspection every Saturday morning, where the general appearance of the soldier could be thoroughly scrutinized. Clean-shaven, neatly polished shoes, clean uniform with buttons all present and utilized, formed the determining percentage features. When the inspection was mounted, horses and harness had to shine, the same as the men.

January 1920 ushered in a period of changes in the staff of officers for Battery D, some of the changes being temporary, others permanent. Trials of sickness and quarantine were also in store for the battery.

Early in January Capt. A. L. Smith was called away from his military duties on account of the death of his father, Edward B. Smith, of Philadelphia, Penna.; a bereavement which brought forth many expressions of sympathy from the men of his command.

Captain Smith returned to camp the latter part of the month. Some time later he was ordered to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to attend the artillery school of fire. Lieut. Hugh M. Clarke also left the battery to attend the school of fire. First-Lieut. Arthur H. McGill was detached from the battery about this time and assigned as an instructor at the Officers' Training School that was opened at Camp Meade. Lieut. Robert S. Campbell was transferred from Battery D at this time.

First-Lieut. (p. 035) Robert Lowndes, of Elkridge. Md., was assigned to temporary command of the battery. First-Lieut. J. S. Waterfield, of Portsmouth, Va., served as an attached officer with D Battery for some time.

First Sergeant William C. Thompson and Supply Sergeant Merle Liebensberger were successful applicants to the officers' training school at Meade. James J. Farrell, of Parsons, Penna., was appointed acting first-sergeant and Thomas S. Pengelly, of Hazleton, Penna., was appointed acting supply sergeant, both appointments later being made permanent.

"Retreat," the checking-in or accounting for all soldiers at the close of a day's routine, was made a formal affair for the 311th Field Artillery on January 13th, 1918. The erection of a new flag pole in front of regimental headquarters furnished occasion for the formal formation when the Stars and Stripes are lowered to the strain of "The Star Spangled Banner" or the "Call to the Colors."

When the formal retreat was established Battery D was in the throes of a health quarantine. A case of measles developed in the battery and an eighteen-day quarantine went into effect on January 19th. About a score of battery members, who were attending speciality schools and on special detail work, were quartered with Battery E of the regiment while the quarantine lasted.

On March 24th scarlet fever broke out and a second quarantine was put into effect. This quarantine kept Battery D from sharing in the Easter furloughs to visit home.

The regular routine of fatigue duty and drill formations took place during the quarantine periods, the restrictions being placed on the men leaving the battery area between drill hours.

On March 6th Battery D took occasion to celebrate. The battery kitchen had been thoroughly renovated by Mechanic Grover C. Rothacker and Mechanic Conrad A. Balliet, both of Hazleton, Penna., the renovation placing it in the class of "The best kitchen and mess hall in camp," to quote the words of Major General Joseph E. Kuhn, divisional commander, when he inspected Battery D on Saturday, March 23rd.

A fine menu was prepared for the banquet that was held on the night of March 6th. Col. Raymond Briggs and the battalion officers were guests at the banquet and entertainment that was furnished in the barracks until taps sounded an hour later than usual that night.

Details continued to play a big part in the life of Battery D. On March 11th the first detail of fifty men was sent to repair the highway near Portland. These details had a strenuous time of it; the hardest work most of the detail accomplished was dodging lieutenants.

Transfers had made big inroads in the battery's strength. Guard duty fell to the lot of the battery once a week. When the guard detail was (p. 037) furnished there were scarcely enough men left to do the kitchen police work and other detail work. It was a time when rank imposed obligation. Sergeants and corporals had to get busy and chop wood and carry coal and wash dishes and police up and in many other ways imitate the buck private.

On March 5th Lieut. Frank Yeager inaugurated a system of daily inspections at retreat, when the two neatest appearing men in line were cited each day and rewarded with a week-end pass to visit Baltimore or Washington, while those who got black marks for the week were put on detail work over the week-end. A list of honorable mentions was also established for general tidiness at "bunk" inspections.

Rumor was ever present at Camp Meade. Almost every event that transpired was a token of early departure overseas, or else the "latrine-dope" had it that the outfit was to be sent to Tobyhanna for range practice.

The first real evidence of overseas service presented itself during March when physical examinations were in order to test the physical fitness for overseas duty. Several, who it was deemed could not physically stand foreign service, were in due time transferred to various posts of the home-guards. Several transfers were also made to the ordnance department; a number of chemists were detached from the battery, and transfers listed for the cooks' and bakers' school, for the quartermasters, for the engineers, for the signal corps, in fact men were sent to practically all branches in the division.

On Saturday, March 30th, wrist watches were turned to 11 o'clock when taps sounded, ushering in the daylight savings scheme that routed the boys out for reveille during the wee dark hours of the morning.

Training during April centered on actual experience in taking to the march with full mounted artillery sections. April 4th, 1918, found a detail from Battery D leaving camp at 8 a. m., with a section of provisional battery, enroute to Baltimore to take part in the big parade in honor of the opening of the Liberty Loan drive on the first anniversary of America's entrance into the war. While in Baltimore the outfit pitched camp in Clifton Park. The parade, which was reviewed by President Woodrow Wilson, took place on Saturday, April 6th. The detachment returned to camp by road on Sunday, April 7th.

During (p. 038) April a decree went forth to the Battery that set details at work every day clipping horses. Every one of the one hundred and sixty-four battery horses was clipped.

The morning of Friday, April 26th, was declared a holiday at Camp Meade; all units being called forth to participate in a divisional parade and Liberty Loan rally.

A battery hike in march order was set for May 6th. The battery took to the road at 8 a. m., and drove through Jessup, thence to West Elkridge, Md., a distance of sixteen miles, where camp was pitched and the battery remained for the night, returning to camp the following afternoon after several firing problems in the field were worked out by proxy fire.

Chances for a quick departure overseas began to warm up about the middle of May, which perhaps was responsible for the big divisional bon-fire that was burned on the night of May 13th.

First authentic signs of departure from Camp Meade came during the month of June when the boys witnessed the departure of the infantry regiments of the division.

Void of demonstrative sendoff, regiment after regiment, fully and newly equipped, was departing on schedule; thousands and thousands of sturdy Americans, ready to risk all for the ideals of liberty and freedom.

It was with no unsteady step they marched through the streets of the military city that had sheltered, trained, tanned, and improved them aright for the momentous task which was before them.

The scene, as they marched, is one that will live in memory of the boys of Battery D. It was no dress parade such as the march of like thousands in a civilian city would occasion. Battery D men and others were spectators, it is true, and the departing ones were sent off, as was later the case with Battery D, with cheers of encouragement and words of God-speed--the spirit breathed being of hearty, thoughtful patriotism such as can come only from a soldier who is bidding adieu to a comrade in arms, whom he will meet again in a common cause.

Wonderful days of activity within Battery D foretold the news of departure. The regiment was in first class shape to look forward to service overseas, despite the fact that range-practice was a negligible factor. During the latter part of May, firing, to a limited extent, was practiced from the three-inch field pieces directed over the Remount station, but the experience thus gained was too light to be important. About this time a French type of 75 mm. field piece was shipped to the regiment. Major David A. Reed became the instructor on this gun, when it became known that the outfit would likely be given French equipment upon arrival overseas. One gun for the regiment, however, and especially when received only several weeks in advance of the departure for overseas, afforded but little opportunity for general instruction on the mechanism of the new field piece.

France, moreover, was the goal and the real range practice was left as a matter of course for over there.

All activity centered on getting ready to depart. The battery carpenters and painters were kept busy making boxes and labelling them properly (p. 041) for the "American E. F." Harness was being cleaned and packed. The time came for the horses to be returned to the Remount station. Supply sergeants were busy as bees supplying everybody with foreign service equipment. It proved a common occurrence to be routed out of bed at midnight to try on a pair of field shoes. All articles of clothing and equipment had to be stamped, the clothing being stamped with rubber stamps, while the metal equipment was stamped with a punch initial. Each soldier got a battery number which was stamped on his individual equipment.

On June 28th, Joseph Loskill, of Hazleton, Penna., and William F. Brennan, of Hazleton and Philadelphia, Penna., were assigned to accompany the advance detail of the regiment. Lieut. Arthur H. McGill was the Battery D officer to accompany the advance detail, which left Camp Meade about 7 p. m., proceeding to Camp Merritt, N. J., for embarkation. The advance guard arrived at Jersey City the following morning at 6 o'clock, where they detrained and marched to the Ferry to get to Hoboken. There the detachment was divided, the officers boarding the S. S. Mongolia, the enlisted men the S. S. Duc d'Abruzzi. The ships left Hoboken at 10:30 a. m., May 30th, bound for Brest.

Battery D was filled to full war-strength during the first week of July, just before departure, when the outfit received a quota of 150 men who came to the regiment from the Depot Brigade. Five hundred and forty came to the regiment from Camp Upton, N. Y., and Camp Dix, N. J., and fifty from the signal corps in Florida.

In the front door and out of the back of 019 the battery passed in alphabetical line in rehearsal of the manner in which the gang plank of the ship was to be trod. Departure instruction likewise included hikes to the electric rail siding to practice boarding the cars with equipment.

The last few days in camp were marked by daily medical inspections, also daily inspections of equipment. Everybody had to drag all their equipment outside for inspection. The men were fully and newly equipped with clothing and supplies upon leaving. Two new wool uniforms, two pairs of field shoes, new underwear, socks, shirts, towels, toilet articles, and a score of other soldier necessities, were issued before leaving. All old clothing and equipment was turned in.

Each man was allotted a barrack-bag as cargo. The barrack-bag was made of heavy blue denim with about a seventy-five pound capacity, (p. 042) which weight was cited as the limit a soldier could obtain storage for in the ship's baggage compartments.

Although seventy-five pounds was the order, all the boys resorted to some fine packing. There were not many under the limit. Most of the boys had their knitted garments in the bag, also a plentiful supply of soap, because rumor had struck the outfit that soap was a scarce article in France. Milk chocolate and smokes were also well stocked in.

Besides the barrack-bag each soldier was provided with a haversack and pack-carrier, in which were carried--on the back--two O. D. blankets, toilet articles, extra socks, clothing, and the various articles that would be needed on the voyage across.

Saturday, July 13th, 1918, was the memorable day of departure from Camp Meade. Battery D furnished the last guard detail of the regiment at Meade. The 13th, as luck would have it, dawned in a heavy shower of rain. Reveille sounded at 5:15 a. m., after which, those who had not done so the night previous, hiked out in the rain and emptied the straw from their bed-ticks; completed the packing of their bags and packs and loaded the bags on trucks while the rain came down in torrents.

As was usually the case in army routine, early reveille did not vouch for an early departure from camp. Detail aplenty was in store for the boys all day. The last meal was enjoyed in 019 mess-hall at 5 p. m.,--then started a thorough policing up of barracks. Sweeping squads were sent over the ground a dozen times and finally the boys assembled outside on the battery assembling grounds, at 7:30 p. m., with packs ready and everything set to begin the march to entrain.

During the hours of waiting that followed the boys indulged in a few sign painting decorations. Among the numerous signs tacked to 019 were:

"For Sail. Apply Abroad."

"For Rent, for a large family; only scrappers need apply. Btry D, 311th F. A."

"Von Hindenberg dropped dead. We're coming."

It was a grand sight to see the regiment depart at 8:45 p. m. The band was playing; colors were flying at the head of the column--everybody was in high spirits. But there were no civilians to enjoy the spectacle. It was night and but few knew of the departure. The rain had ceased and twilight was deepening into darkness as the regiment, excepting Battery A, which was left in camp for police detail, to follow (p. 043) a few days later, started on the hike; back over practically the same route the soldiers were marched from Disney to 019 when they first arrived in camp. This time they were leaving 019; marching for the last time with Battery D through the reservation of Camp Meade; marching to the railroad yards at Disney where trains were being made up to convey the regiment to a point of embarkation. But few knew whether it was to be Philadelphia, New York, or Hoboken. The men were leaving home and home-land and departing for a land of which they knew nought. What the ocean and Germany's program of relentless submarine warfare had in store for them, no one knew. All hearts were strong in the faith and all stout hearts were ready to do and to dare; content in the knowledge that they were doing their duty to their home and their country.

Land appeared in rugged outline along the horizon as the Steamship Morvada swept the waves when dusk was falling on the Tuesday evening of July 16th, 1918. It was a beautiful mid-summer's night and the boys of Battery D, in common with the members of the 311th regiment, stood at the deck railings of the S. S. Morvada and watched the outline of shore disappear under cover of darkness. The ship had been sailing since 11:30 a. m., Sunday, July 14th, at which time the Morvada had lifted anchor and slowly pushed its nose into the Delaware River; leaving behind the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad docks at Port Richmond, Philadelphia, Penna., the last link that held them to their native shores.

Surmises and guesses were rife as the ship rolled on in the darkness, leaving the boys either arguing as to the destination or else seeking their "bunk" down in the "hatch" and rolling in for the night.

It was generally agreed that the course thus far was along the coast. It was apparent that the ship was skirting coastline, because convoy protection had been given by sea-planes flying out from the naval coast stations, accompanying the transport for a distance, then disappearing landward. The boys on the transport spent many an idle hour watching the aviators circle the ship time and time again, often coming within voice range of the transport's passengers.

It was also settled that the course had been Northeast, but no one was quite certain as to location.

The morning of July 17th found the Morvada approaching land. A lighthouse appeared in the dim distance, then, as the hours passed and the ship sped on, the coast became visible and more visible, disclosing rugged country, rising high from out of the water's edge. The country, moreover, appeared waste and devastated; the land being covered with wrecked buildings that showed signs of explosive force.

Location finally became apparent as harbor scenes presented an unique picturesqueness of territory. The S. S. Morvada was in Halifax harbor, Nova Scotia, and the surrounding territory was the scene of the famous T. N. T. explosion. It was 11 o'clock on the morning of July 17th that the ship cast anchor in Halifax harbor and word was passed that all on board could remove life preservers and breathe a sigh of relief.

To (p. 045) be suddenly found in Canadian environment furnished a new thrill for the soldiers. The Saturday night previous the same soldiers were making the trip from Camp Meade to port of embarkation.

Everybody was expecting a lay over in an embarkation camp before embarking, therefore the surprise was the greater when the train that left Camp Meade at midnight on the evening of July 13th, deposited its cargo of soldiers on the pier at Port Richmond within a short distance of the ship that was waiting for its cargo of human freight before pulling anchor for the first lap of the France-bound journey.

Orders to detrain were given at 8:29 a. m. Tired and hungry the soldiers were greeted on the pier by a large delegation of Red Cross workers who had steaming hot coffee, delicious buns, cigarettes and candy to distribute to the regiment as a farewell tribute and morning appetizer. Postal cards were also distributed for the soldiers to address to their home-folks. The messages were farewell messages and were held over at Washington. D. C., until word was received that the Morvada had landed safely overseas.

At 8 a. m. the repeat-your-last-name-first-and-your-first-name-last march up the gang-plank started. Each man got a blue card with a section and berth number on; also a meal ticket appended, after which it was a scramble to find your right place in the hatch.

At 11:30 o'clock anchor was lifted; the little river tug boat nosed the steamship about; then, with colors flying, the band playing, the Morvada steamed down the Delaware; passing Hog Island in a midway of ships from which words of farewell and waves of good-bye wafted across to the Morvada. The sky-line of Brotherly Love, guarded over by William Penn on City Hall, gradually faded from view and the Sunday afternoon wore on, as the boys spent most of their first day aboard a transport on deck, watching the waves and admiring the beauties of nature, revealed in all splendor as the ever-fading shore line, viewed from the promenade deck, lost itself into the mist-like horizon of sky and water, richly enhanced by the brilliancy of a superb sunset.

The S. S. Morvada skirted the shore for some time and for the first few hours all was calm on deck. By night, however, sea-sickness began to manifest itself and there was considerable coughing up over the rail.

Besides watching the waves and the various-sized and colored fishes of the deep make occasional bounds over the crest of the foam, the (p. 046) soldiers spent their time trying to get something to eat, which was a big job in itself.

The Morvada was an English boat, of small type, that was built in 1914 to ply between England and India, carrying war materials. The voyage of the 311th was the second time the Morvada was used as a transport. Except for officer personnel the ship was manned by a crew of East Indians, whose main article of wearing apparel was a towel and whose main occupation was scrubbing and flushing the decks with a hose, just about the time mess call found the soldiers looking for a nice spot to settle down with mess-kit and eating-irons. Up forward were batteries B, D, E, and F, and the Supply Company, and aft were Headquarters Company, Battery C, and the Medical Detachment. Each end of the ship had its galley along which the mess lines formed three times a day. The khaki-clad soldiers could not get used to the English system of food rationing with the result that food riots almost occurred until the officers of the regiment intervened and secured an improvement in the mess system.

The first night in Halifax harbor was a pleasant relief from the strain of suspense that attended the journey to Canadian waters. Deck lights were lighted for the first time and vied for brilliancy in the night with the other ocean-going craft assembled in the harbor. The Morvada did not dock, but remained anchored in the harbor, from where the soldiers on board could view the city and port of entry that was the capital of the Province of Nova Scotia.

To the Southeast the city of Halifax, situated on a fortified hill, towering 225 feet from the waters of the harbor, showed its original buildings built of wood, plastered or stuccoed; and dotted with fine buildings of stone and brick of later day creation.

When the soldiers on board the Morvada arose on the morning of July 18th the Halifax harbor was dotted with several more transports that had arrived during the night. The day was spent in semaphoring to the various transports and learning what troops each quartered. Official orders, however, put a stop to this form of pastime and discussion was shifted to the whys and wherefores of the various camouflage designs the troop ships sported.

During the stay at Halifax the first taste of mail censorship was doled out. Letters were written in abundance, which were treated rather roughly by two-edged scissors before the mail was conveyed to Halifax to be sent to Washington, D. C., to await release upon notification (p. 047) that the Morvada had arrived safely overseas. Many of these first letters are still held as priceless mementos by the home-folks.

Each morning of the succeeding days that the Morvada was anchored in Halifax harbor brought several new ships to cluster about in the wide expanse of water. A sufficient number for convoy across the Atlantic was gradually assembling, each ship appearing in a different regalia of protective coloration that made the harbor sight vastly spectacular.

Newspapers from the Canadian shore were brought on board each day. On July 19th the papers conveyed the information that the United States Cruiser, San Diego, was sunk that day ten miles off Fire Island by running on an anchored mine placed there by German U-boats. The Morvada had traversed the same course several days previous.

To read of such occurrence, in such environment was to produce silent thought. To be in the harbor of Halifax, within shadow of McNalis Island that rested on the waves at the mouth of the harbor, was to be in the same environment as the confederate cruiser, "Tallahassee," which slipped by night through the Eastern passage formed by McNalis Island, and escaped the Northern vessels that were watching off the western entrance formed by the island.

The time was drawing near when the Morvada was destined to creep stealthily through the night, to cross the 3,000 miles of submarine infested Atlantic.

Under serene skies on the morning of July 20th, seventeen ships, assembled in Halifax harbor, made final preparations to steam forth to the highways of the broad Atlantic.

At 9:30 o'clock that morning the convoy maneuvered into battle formation with a U. S. cruiser leading the convoy while four small sub chasers circled about in high speed and an army dirigible flew overhead. Each ship was directed in a zig zag course, a new angle of the zig zag being pointed every few minutes, a course of propellation that continued the entire route of the water way.

Good-byes were waved from ships stationed along the several miles of water course that marked the harbor's length, until the open Atlantic was reached, then the sub chasers and the dirigible turned about, leaving the seventeen transports and supply ships under the wing of the battle cruiser that proceeded to pick out the course across the ocean, to where bound no one on board, save the captain of the ship, knew.

Clad in their life preservers the soldiers idled about the decks as the convoy sped on. It was a source of delight to stand at the deck rail and watch the waves dash against the steel clad sides of the ship. On several occasions when the waves rolled high, many on board experienced the sensation of a sea bath, the stiff sea breeze carrying the seething foam high over the rail on to the deck.

To see the waves roll high created the impression of mightiness of creation; the impression of mountains rising magic like at the side of the vessel. Suddenly the ship rises to the crest of the wave and the recedence leaves one looking down into what appears like a deep cavern.

When the sun was rising in the direction one was thrilled by the beauties of the rainbow observed in the clearness of the waves, when, at the height of dashing resplendence the surging sprays descend in fountain semblance, drinking in, as it were, the very beauty of God's handiwork.

The same position on deck the boys found none the less attractive when the shades of night had fallen. On one of the first nights out the ship passed through an atmosphere of dense fog, suddenly to emerge into elements of star lit splendor, the moon, in full radiance, casting (p. 049) a silvery luminous path on the sparkling waves. It was a phenomena worthy of the tallest submarine risks to witness. The full moon and the very repleteness of things aesthetic gave opportunity for those who were able to portray an attitude of indifference, to tell gravely how the radiance of the night fully exposed the convoy to the U-boats that were lurking in every wave.

Established routine of transport duties and formations was continued during the ocean voyage. Ship-abandon and fire drills were a daily feature of life aboard. Each outfit had a specific place to congregate when the signal for ship-abandon drill was sounded. All that was necessary was to stand at the appointed place while the coolies, comprising the crew, scampered to the life-boats and made miniature attempts at hacking the ropes and dropping to the waves.

The promenade deck, both port and starboard sides, was in use each day accommodating group after group for half-hour periods of physical exercise. The tossing of the vessel lent itself in rhythm to the enjoyment of the calisthenics, or else it was physical exercise enough in trying to maintain an equilibrium while the arms and legs were raised alternately in eight counts.