The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Village by the River, by H. Louisa Bedford This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Village by the River Author: H. Louisa Bedford Release Date: January 16, 2007 [EBook #20381] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE VILLAGE BY THE RIVER *** Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | WHAT THE VILLAGERS SAID |

| II. | AN UNLOOKED-FOR INHERITANCE |

| III. | FIRST IMPRESSIONS |

| IV. | OPPOSING VIEWS |

| V. | A QUESTION OF EDUCATION |

| VI. | A VOTE OF CONFIDENCE |

| VII. | A MOMENTOUS DECISION |

| VIII. | AN OUTSTRETCHED HAND |

| IX. | A CRISIS IN A LIFE |

| X. | RIVAL SUITORS |

| XI. | A FRIEND IN NEED |

| XII. | KITTY'S CHRISTMAS TREE |

| XIII. | THE CALL OF GOD |

| XIV. | A CHANGE OF MIND |

"Well, it were the grandest funeral as ever I set eyes on," said Allison, the blacksmith, folding his brawny arms under his leather apron, and leaning his shoulders against the open door of the smithy in an attitude of leisurely ease.

The group, gathered round him on their way home from work, gave an assenting nod and waited for more.

For convenience Allison shifted his pipe more to the corner of his mouth, and proceeded—

"Not one of yer new-fangled ones, with a glass hearse for all the world like a big window-box, and a sight of white flowers like a wedding. Everything was as black as it should be; I never see'd finer horses, in my life, with manes and tails reachin' a'most to the ground, and a shinin' black hearse with a score of plumes on the top, and half a dozen men with silk hatbands walking alongside it, right away from the station to the churchyard yonder." And Allison threw a backward glance over the billowy golden cornfields, which separated the village from the church by a quarter of a mile, where the grand tower reared its head as if keeping watch over the village like a lofty sentinel.

"There were lots of follerers, I expect?" suggested Macdonald, gently. He was a Scotchman, and worked on the line, and he shifted his bag of tools from his shoulder to the ground as he spoke. "A gentleman like him would leave a-many to miss him."

Allison stared across at the river which ran swiftly by on the opposite side of the road. The long village of Rudham skirted its banks irregularly for a mile or more. The blacksmith had plenty of news to communicate, but he was not to be hurried in the relating of it.

"I'm tryin' to recolleck," he said, knitting his brows, "but I can't mind more than two principal mourners. And the undertaker, when he stopped to water his horses at the inn, told Mrs. Lake as they was the doctor and the lawyer; but, relations or no, they did it wonderful well! Stood with their hats off all in the burnin' sun, and went back to look at the grave when the funeral was over."

"The household servants was there—leastways the butler and footman," said Tom Burney, a dark-eyed, gipsy-looking young man, who was one of the under-gardeners at the big house on the hill, "but not him as is coming after."

"The question is who is a-comin' after?" said Allison, in a tone of sarcastic argument. "Maybe you'll tell us, as you seem to know such a lot about it?"

Burney coloured under his dark skin, and gave an uneasy little laugh.

"I know what I've heard, no more nor less," he said; "but it comes first-hand from the butler of him who's gone."

Allison gave an incredulous sniff; he was not used to playing second fiddle, and the heads of his listeners had turned to a man in the direction of the last speaker.

"He hadn't no near relation, not bein' a married man," went on Burney, enjoying his advantage; "and Mr. Smith—that's the butler—came and walked round the garden until it was time for his train to go back to London."

"He don't pretend as the property's left to him, I suppose?" broke in Allison, jocosely.

Burney turned his shoulder slightly towards the speaker, and went on, regardless of the interruption—

"Mr. Smith says as the house up there, and all the property, goes to a young fellow not more than thirty, of the same name as the old squire; some third cousin or other."

"Hearsay! just hearsay!" ejaculated Allison, contemptuously. "Who's seen him, I should like to know? Seein's believin', they say."

"Mr. Smith has," said Burney, a ring of triumph in his voice. "He were there when old Mr. Lessing died."

There was silence for a moment. The evidence seemed conclusive, and Allison's discomfiture complete; but, as the forge was the place where the village gossips gathered every day, it was felt to be wise to keep on good terms with the owner.

"Seems as if it might be true," said Macdonald, casting a timid glance at the blacksmith.

"If it is, why wern't he here, to-day, then?" asked Allison, gruffly.

"Not knowin', can't say," Burney answered with a laugh.

"Maybe he'll be comin' to live here," said another.

"He can't! I can tell you that much; there ain't a house he could live in," asserted Allison. "His own place is let, you see, to the Websters—whom Burney there works for,—and he can't turn 'em out, as they have it on lease; and a good thing too. We don't want no resident squire ridin' round and pryin' into everything. The old one kept hisself to hisself, and, as long as the rents was paid regular, he didn't trouble much about us; and there was always a pound for the widows every Christmas. Trust me, it's better to have your landlord livin' in London, and not looking about the place more than once a year. Did Mr. Smith say what the young one looked like, Burney?"

The question was asked a little reluctantly.

"No; but he thinks he's a bit queer in his notions. He asked him whether he'd be likely to want his services; and Mr. Lessing laughed quite loud, and said, one nice old woman to cook and do for him was all he should require now, or at any time in his life. Mr. Smith ain't sure but what he's a Socialist."

"I don't rightly know the meaning of it?" said Macdonald, instinctively, turning to the blacksmith for an explanation.

"It may be a good thing, or it mayn't," declared Allison. "I take it that a Socialist means one as would take from those as has plenty and give to those who has nothing. We're born ekal into the world, and they'd keep us ekal, as far as might be. But it'd take a deal of workin' out, more than you'd think, lookin' at it first; but I'm not goin' to say that it wouldn't be handy to have a Socialist squire. He might divide his land ekal among us, and there'd be no more rent to pay for any of us. There now!"

A general murmur of approval ran round his audience, except with old Macdonald, who gave a quaint smile.

"But it strikes me that such of us as have saved a tidy bit would have to hand it out to be divided equal too. It would not be fair as the Squire should do it all; it would run through, you see."

"Well, I've not saved a brass farthing, so I should come in for a lot; and I'd settle down and marry to-morrow!" cried Burney, gaily. "But, you may depend on it, whoever's got the place will stick to it. I must be getting on to the station. Our people are coming back from abroad this evening, and I'm to be there to help hoist up the luggage. It takes a carriage and pair to carry up the ladies, and an extra cart for luggage."

"It's not the luggage you're going to meet, I'll bet; it's the lady's maid," said a young fellow, who had not spoken before. "If you married next week we all know well enough whom you'd take for a wife;" and Tom moved off amid a shout of laughter.

It was an open secret that Tom was head-over-ears in love with pretty Rose Lancaster, the somewhat flighty maid of Miss Webster, who, with her mother, was returning to the Court that evening. Absence had made his heart grow fonder, and it was beating much faster than usual as he stood on the station platform awaiting the arrival of the train, and, when it ran in with much splutter and fuss, not even by a turn of her head did Miss Rose show herself aware of Tom's presence. Instead, she was looking after her ladies, lifting out their various belongings—not a few in number—and ordering round the porters with a pretty pertness as she counted out the boxes from the van. It was only when she found her own box missing that she turned appealingly to Tom.

"Run, there's a good boy, quick to the other van!" she said, acknowledging him with a nod. "It must have got in there, and the train will be off in another moment."

Tom ran as requested, pantingly rescued the box, and came back smiling to tell her of his successful search.

"That's right," said Rose, graciously. "Now you can help me on to the box-seat of the carriage, if you like. I'm going to sit beside Mr. Dixon."

Dixon was the coachman, and a formidable rival in Tom's eyes.

"I thought, perhaps, as you'd come along of me. I'm drivin' the cart back for Berry, as he had a message in the village. I've not seen you for such a time, Rose."

"Come with you!" said Rose, with a toss of her head. "The ladies would not like it; besides, we shall meet sure enough some day soon. I mustn't wait a minute longer. You need not help me unless you like."

But poor Tom, under the pretext of making some inquiry about the luggage, managed to be near so as to hand up Rose to her seat by the coachman, who appeared far more absorbed in the management of his horses than in the young woman who sat by him, upon whom he did not bestow even a glance, preserving a perfectly imperturbable countenance.

"He's pretending! just pretending—the scamp!" said Tom, under his breath, turning back to his horse and cart.

A strange man stood near stroking the animal's head and keeping a light hand on its bridle. He wore a loosely fitting brown suit, and the hand that caressed the horse was almost as brown as his clothes. His head was closely cropped and his face clean-shaven, showing the clear-cut, decided mouth and chin, and the white, even teeth displayed by the smile with which he greeted Tom.

"You may be glad I was at hand or your cart with its cargo of luggage would have been upset in the road," he said. "It's not a wise thing to leave a creature like this standing alone when a train is starting off."

A quick retort was on the tip of Tom's tongue; he had no fancy for being called to account by a perfect stranger, but, although the words sounded authoritative, the tone was good-humoured.

"Thank you, I only left him for a moment; he stands quiet enough as a rule," he said, taking the bridle into his hand.

The stranger picked up the small portmanteau he had set down in the road, and prepared to walk off, then turned half-hesitatingly back to Tom.

"Can you tell me where I can get a night or two's lodging? It does not much matter where it is as long as it is clean and quiet."

Tom took off his cap and rubbed his head thoughtfully.

"Mrs. Lake's a wonderful good sort of woman."

"And who may Mrs. Lake be?" inquired the stranger, pleasantly.

"She keeps the Blue Dragon, but I couldn't say as it's exactly quiet of a Saturday night. She don't allow no swearin' on her premises, but some of the fellers gets a bit rowdy before they go home."

"Very possibly," replied his companion, dryly. "I don't think the Blue Dragon would suit me; but surely there is some cottager with a spare bed and sitting-room, who might be glad of a quiet, respectable lodger for a bit?"

Tom threw a searching glance at the speaker; he was not quite sure that, notwithstanding his gentle manner of talking, he was to be altogether trusted.

"If you'd step up beside me I'll drive you to the forge," he said, willing to shelve his responsibility of recommendation. "It's close here, and Allison will help you if no one else can. He knows every one's business."

"Just the sort of man I want," said Tom's new acquaintance, climbing into the cart and seating himself on the cushion that had been intended for Rose. His alert grey eyes took in his new surroundings at a glance.

No one could call Rudham a pretty village: it was too straggling, too bare of trees, which had been planted sparsely and attained no luxuriance of growth; but it was not wholly unattractive this evening, with the setting sun turning to gold the varying bends of the river which ran through the valley, and the cottages and farmhouses dotted here and there with a not unpleasing irregularity, and in the distance a softly rising upland turning from blue to purple in the evening light.

"Yonder's the Court, where my people live," said Tom, jerking his whip to a big house more than a mile away that peeped out from among the trees. "It belonged to the old squire who was buried to-day, you know."

"Ah!" ejaculated his listener, not greatly interested, apparently, in the information.

"It's a wonderful fine place, and they say as he who's to have it won't hold no store by it. Pity, ain't it?"

Tom's companion broke into rather a disconcerting laugh.

"Look here, my lad, by the time you're thirty you won't give credit to every bit of gossip that comes to your ears; you'll wait to know that it's true before you pass it on, at any rate. This will be the forge you spoke of, and there's the owner, sure enough, standing at the door. Thank you for the lift, and here's a shilling for your trouble."

But Tom thrust away the proffered tip with a shake of his head.

"No, thank you; you kept the horse safe at the station."

"So, on the principle that one good turn deserves another, you'll give me a lift for nothing. All right and thank you," said the man, dismounting and lifting out his portmanteau. "Good night."

"Good night," said Tom, with an answering nod. "I wonder what his business is?" he thought, as he pursued his way. "Shouldn't be surprised if he was the engineer who's to see to the laying down of the new line; he's that quick, smart way with him as if he'd been about a lot and knew a thing or two."

"Lodgings!" echoed Allison, slowly, as the stranger reiterated his request. "It's not a thing we are often asked for in Rudham. I'd make no objection to taking you in myself, but Mrs. Allison's not partial to strangers."

"I should be sorry to inconvenience Mrs. Allison; is there no one else you can think of?"

"Mrs. Pink 'ud do it; but she's a baby who's teething, and fretful o' nights."

"And that would not suit me!" said the newcomer, with decision.

"I have it!" cried Allison, bringing down his big hand with a resounding slap upon his knee. "Mrs. Macdonald's the body for you! There's not a better woman in Rudham, and I know 'em pretty well in these parts. Her husband's only just gone up street; he were talkin' here not five minutes ago. There's only their two selves, and the cottage one of the best in the place."

"It sounds as if it would suit me down to the ground. And if Mrs. Macdonald could give me shelter, even for a few nights, it would give me time to look about me."

"Thinkin' of settlin' in these parts?" inquired Allison. "There's no house as I knows on vacant."

"I've no settled plans at present," answered the stranger. "If you'll kindly direct me to Mrs. Macdonald's, I'll go and try my fate."

"Eighth house from here, set back a bit from the road, with a little orchard behind it; and you can say as I sent you," said Allison, feeling his name a good enough recommendation for any stranger.

The door of the eighth house set back a little from the road was partially open as the new arrival made his way up the box-bordered path, with beds on either side of it gay with flowers; and before he could knock a neatly dressed middle-aged woman threw it wide and surveyed him from head to foot.

"And what may you be wanting, sir?" she asked, quite civilly.

"A lodging for a night or two. And Mr. Allison at the forge seemed to think you might be inclined to take me in."

"I'm not sure as my John will wish it. But if you'll step inside I'll ask him," replied Mrs. Macdonald, motioning him to a chair.

"Unless they turn me out by force, I shall stay," he said, looking round him with a pleased smile.

It was not his fault, but "my John's" deafness, that caused him to hear himself described as a "very decent man, who spoke as civil as a gentleman; and it was awkward to find yourself in a strange place on a Saturday night with nobody ready to put themselves about a bit to take you in."

"John will yield in the long run," sighed the unwilling listener. "Mrs. MacD. rules the roost, unless I'm greatly mistaken."

Apparently his conjecture was right, for in another minute the woman reappeared to say that she and her husband were willing to let him have the front bed and sitting-room if, after due inspection, they proved good enough for him.

"We're not used to grand folk," she said, a trifle awed by the sight of the portmanteau. "I cooked for a plain family before I married my John, and——"

"Then it's certain that you can cook for me; I'm not nearly so much trouble as a plain family," said her visitor, laughing. "I'll carry up my things if you'll show me the way, for I shall go no further than this to-night. I dare say you can give me some tea, and then I'll go out and order in some food."

"I dare say you eat hearty, sir; or we've some fine new-laid eggs," suggested Mrs. Macdonald.

"The very thing. You can't get such a thing in London; the youngest new-laid egg is about a month old, I fancy. Thank you," (with a glance round the dimity-curtained room, fragrant with lavender); "I shall be as happy as a king."

When her lodger was safely established at his evening meal, and Mrs. Macdonald was satisfied that she could provide nothing more for his comfort, she went upstairs to tidy his room, shaking her head a little over the various things that littered the floor and table.

"He's not so tidy as my John, but he's not got his years over his head," she said, as she closed the portmanteau and shoved it towards the dressing-room table.

As she did so the name on the label caught her eye, she could not help reading it; and then drew in her breath with a sharp exclamation of surprise. The next instant she hurried softly but quickly down the stairs, took her astonished helpmeet by the arm, and dragged him into the orchard, closing the kitchen door behind her.

"John!" she said, "who do you think has come to us? Who is it that has come quite humble like for shelter under our roof this night?"

In her eagerness to extract an answer she pinched the arm she held a little.

"It's not a riddle you're asking me?" said John, withdrawing himself a pace.

"No, no, man! it's the young squire himself, for sure. Paul Lessing is on his portmanter," she said looking round, for fear she should be overheard by a neighbour. The news must be digested.

A week before, Paul Lessing and his only sister Sally had started for a three week's tour on the continent, with as light-hearted a sense of enjoyment as any boy or girl home for the summer vacation. They were orphans, with only each other to care for; and Paul had not feared to take up some of their slender capital to enable his sister to complete her college course at Girton. If she had to earn her own living, she should at least have the best education that money could give; and Sally had made the best use of her opportunity. Her name was high in the honour list, and Paul decreed that, before any plans were discussed for her future, they should dedicate a certain sum to a foreign tour.

"It will be a good investment, Sally. You are looking pale after all your work. We will make no definite plan; it's distance that swallows up the money, so we'll start off for Brussels, and move on when we feel inclined, possibly to the Rhine, and so to Heidelberg." And Sally, in the joyousness of her mood, felt that all places would be alike delightful in the company of her brother.

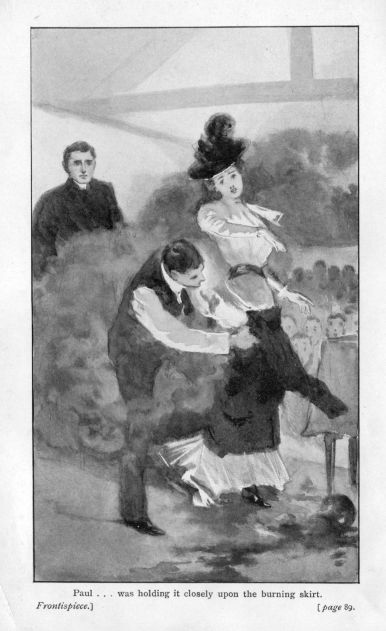

Two days later found the brother and sister seated in the garden of the café that adjoins the park at Brussels. Even now, at eight o'clock in the evening, it was exceedingly hot, and the boughs of the trees overhead, through which here and there a star glimmered, were absolutely motionless. The band which played was the best string-band in Brussels, attracting a great throng of listeners; and every table around them had its complement of guests; and the civil waiters who flitted hither and thither had almost more than they could do to keep the tables properly served. Paul was smoking and reading the paper, but Sally needed no better amusement than to watch the various groups about her, and to listen to the exquisite playing of the band.

"We want something like this in England, Paul," she said, laying a hand on his arm—"lots of places like this out-of-doors in the fresh air, under the stars and trees, where people can go and drink their tea or coffee, and listen to music that must refine them whilst they listen."

Paul laid by his paper and laughed. "Yes," he said, "and when I get into Parliament—if ever—I will do my utmost to make some of our wealthy citizens disgorge a part of their wealth to put places such as this within the reach of everybody. I confess there are difficulties——"

"What?" inquired Sally, with childish impatience.

"Our beastly climate, to begin with," Paul answered with a little laugh. "Want of space, and want of trees when you get the space. Then look at our population in our big cities. Brussels is just a pocket-town, if you come to compare it with London. Of course the recreation of the masses is only one of the many vexed questions concerning them that Government eventually must take in hand. If you want people to be moral, you must give them a chance of enjoying themselves in an innocent fashion."

"Of course, you could do a lot if you once got into Parliament!" cried Sally, with the enthusiasm of her twenty years. "When shall you get in? and where shall you stand for? and may I help in the election?"

Paul laughed louder than before. "There's a deal to be done before I can even think of standing for any place. First, I must accumulate enough capital to bring me in a small independent income. You know we have not much now."

"You can have anything and everything that belongs to me; I mean to earn my living somehow," declared Sally, sturdily.

"Thank you. I don't mean to start that way; and money comes in slowly to a barrister, although I am getting on fairly well. Then I will stand for any place that will return me, after learning my honestly expressed political opinions. Each man has his pet hobby, and I feel that mine is the bettering of the condition of the masses."

"That will make you popular," said Sally.

"And I don't care a fig for popularity. I want to help to leave the average condition of the people better than it is at present. The contrast between the very rich and the very poor of our land is something too awful to contemplate."

His talk, which he had begun half in play, had ended in deadly earnest; and Sally laid her hand mischievously over his eyes.

"Then don't contemplate it—at any rate just now, when I am so merry and happy. You've not answered my last question. May I help in your election? It would be such fun."

"I think not, Sally," Paul said smiling again.

"Oh, what a mass of inconsistency!—when you were saying only to-day that you saw no just cause or impediment why women should not do anything for which they have a special fitness. Now I feel politics will be my speciality, and I would not canvass for any one unless I quite understood their views."

"Well, my Parliamentary career is in the far future," Paul interposed; "and certainly I should not give my sanction to your undertaking any work of that kind at present. You are much too young, and much too——"

"Pretty, were you going to add?" broke in Sally, with a ripple of laughter. "I'm afraid not: enthusiastic would be the more likely adjective for you to use concerning me. Besides I don't think I am pretty. 'My dear,' said that candid old Miss Sykes to me the other day, 'you might have been very good-looking if all your features were as good as your eyes.' Why do ladies of a certain age take it for granted that they can say what they choose to the budding young woman? It annoys me frightfully. Oh, Paul!" with a sudden lowering of her voice, "talking of pretty, there's a perfectly lovely girl who is seated with her mother at the third table from ours. Don't turn your head too quickly or she will think we are talking of her; and then you can keep your head turned in the direction of the band. Her profile comes in between it and you."

Paul did as he was bid. Sally was right, the girl to whom she directed his attention was lovely beyond compare; and yet there was something in her face that failed to satisfy him. The very perfection, too, of everything about her, gave him a feeling of unconscious irritation.

"Well?" asked Sally, when he turned back to her.

"She's beautiful, certainly; but I don't like her."

"It's just because you did not discover her first."

Paul did not trouble to answer; there was a general stir amongst the company. The concert was drawing to a close, and the burghers of Brussels began to think of home and bed. The wives slipped their knitting into their pocket; the husbands bestowed a passing nod and guttural good night to each other as they moved away; and the twinkling lights began to be extinguished one by one. In the crowd at the entrance Paul and Sally found themselves close to the girl whom Sally had so greatly admired. She was talking in low, clear tones to her mother.

"Ought not to have come? What nonsense, mother! It has been quite an amusing experience to see the way these people pass their evenings; they are quite nice and respectable. I confess now I should be glad to see our carriage. I feel I'm getting smoke-dried like bacon—or ham, is it?"

It was evident that the elder of the two ladies was rather frightened and losing her head.

"I'll not do this again without a man of our own," she said with nervous irritability.

Paul stepped forward, raising his hat. "Is your carriage anywhere about? Can I get it for you?"

"Oh, thank you so much. It's a private one from the Hotel de Flandres, and I told the man to stop here."

"Unfortunately the police regulations interfere with your orders," Paul said, with a slight smile. "He must take his place in the ranks. I will soon find it for you if you will stay here."

"Name, Webster," said the older lady.

So Paul, with a nod to Sally to stay where she was, hurried off, returning in a moment with the carriage.

"Thanks so much," said the girl whom Sally admired, as Paul handed her in and closed the door behind her.

"I was quite glad of the time to consider her more closely!" cried Sally, as they drove off. "I've never seen what I call an absolutely perfect face before. I wonder if I shall see her again?"

"For my part I don't wish it," Paul answered carelessly. "Beautiful she is; but she bears the knowledge of it about with her like an overpowering perfume, and is the very impersonation of the insolence of riches!"

"Why, Paul, you are not often either narrow-minded or unjust."

"How dare she comment upon these Belgians, who nearly all possess a smattering of English, under their very noses!" continued Paul, angrily. "'Quite nice and respectable,' indeed! As she and her mother were in a fix I was bound, as a man, to offer my services; but I did it unwillingly."

Paul's indignation was short-lived, and he and Sally walked along the streets leisurely, on their way back to their hotel, talking on indifferent subjects. They paused in the hall of the hotel, running their eyes over the letters displayed outside the post-office, to see if the evening post had brought any for them. There were none for Sally; but two or three for Paul, that had been forwarded from his chambers in London.

"I'll go into the salon and read them, and then we'll go upstairs to bed. I feel infected by the early hours of these foreigners," he said, yawning a little.

Sally turned over the leaves of a paper whilst her brother opened his letters. The last of them he read and re-read several times; then rose and laid his hand on Sally's shoulder.

"I'm awfully sorry, Sally, but I shall have to go back to London by the first train to-morrow."

The long-drawn "O-o-o-h!" was powerless to express half the disappointment his sister felt.

"It's business, I suppose: everything nasty is always business," she said at last.

"Well, no, it's not business; and it certainly is not pleasure. You remember I had an old godfather, Major Lessing? I'm sure he amply fulfilled his godfatherly duty by the silver milk-jug he gave me at my baptism—which I've never set eyes on for many a long year, by the way—and the tips he shoved into the palm of my hand whenever I paid him a visit on my way from school. I don't think I've seen him since; and why, now that he's dying, he has a particular desire for a call, I can't tell you. It's inconvenient, to say the least of it."

"Must you go?" asked Sally, despairingly.

"I'm afraid so. It's the last thing one can do for him, poor old chap!"

"He might have chosen some other time to be ill," said Sally, who, not knowing the major, was inclined to be heartless.

"Well, yes. But we won't lose our holiday; we'll come again later, Sally."

"We shan't! I'm perfectly certain we shan't!" cried Sally, turning away her head so that Paul should not see that there were tears in her eyes. "It was too delightful a plan to carry out."

The next day found Paul and his sister back in London. Sally was to go to an aunt for a few days, until Paul could settle his plans; and when he had seen her off from the station, he turned his own steps in the direction of the quiet square where his godfather had spent his solitary life since the days of his retirement from active service. His eyes turned instinctively to the windows, to see if the blinds were drawn down; but the house wore its usual aspect of dignified reserve, with its slightly opened casements. The imperturbable butler, who answered Paul's ring at the bell, seemed at first inclined to question his right to enter.

"My master is very sadly, sir; he's not fit to see any one."

"But he sent for me," said Paul, quietly. "Will you let him know, as soon as possible, that Paul Lessing has come in answer to his letter?"

At the mention of the familiar name Smith's manner altered perceptibly; he threw open the library door and ushered Paul in. It was scarcely a minute before he returned.

"My master is awake and will see you at once, sir."

"Has he been long ill?" Paul asked.

"It's been coming on gradual for a year or more, sir. Creeping paralysis is what the doctors call it. He's no use left in his legs, and very little in his arms or hands; but his brain seems as active as ever. He took a turn for the worse last week, and the end, they think, may come at any time."

"Thank you; I'll go upstairs now."

He entered the sick-room so quietly that the nurse, who sat by the bedside, did not hear him; but the grey head on the pillow turned quickly, and the dying eyes shone with eager welcome.

"I'm glad you've come; I thought you meant to leave it till too late," was the abrupt greeting.

"I was abroad, and did not get your letter at once," Paul said gently.

"And you came back? That's more than many fellows would have done. Nurse, draw up those blinds, and leave us, please; there are several things I have to say. No, you need not talk about my saving my strength. What good will it do? A few minutes more life, perhaps," he added testily, as he saw the nurse giving Paul some admonition under her breath. "Women are a nuisance, Paul; and at no time do they prove it more than when you are ill and under their thumb. There! take a seat close by me, where I can see you."

"You wanted to see me about something particular, your lawyer told me," said Paul, filled with pity at the sight of the perfectly helpless figure. "It may be that I can carry out some wish of yours. I should be glad to be of service to you."

Major Lessing did not answer for some minutes, and Paul ascribed his silence to exhaustion. In reality the keen eyes were scanning Paul's face critically, as if trying to read his character.

"I wanted to see you; and now you've come I don't know what to make of you. It has crossed my mind more than once since I've lain here, that I've been a rash fool to make a man I know so little of, my heir."

Paul could not repress an exclamation of astonishment; the news gave him anything but unmixed pleasure.

"It was surely very rash, sir. I've no possible claim upon you. I have scarcely even any connection with you except the name."

"That's it," said the major. "You have the name, and that must be carried on and a distant tie of relationship; and there's something else, Paul. Years ago I wanted to marry your mother. You are my godson; you might have been my real son, you see."

Paul felt a lump in his throat; this love-story of long ago was pathetic. His mother had died when he was still quite a child, but she lived in his memory as beautiful and fascinating.

"She was half Irish," he said.

The major nodded. "So, partly from sentimental reasons, and partly because there was no one better, I've left the property at Rudham to you," he went on with a smile. "There would have been plenty of money to have left with it; but I've made some very bad speculations lately, and lost a great deal. I took to speculation from sheer want of amusement. I was a good billiard player as long as I had the use of my limbs; but here I've been, literally tied by the legs, for the last two years. The only thing properly alive about me was my brain, and speculation has interested me; but I was badly hit ten days ago. There will be some money, but you won't be a rich man."

"I don't care about it," interposed Paul, eagerly.

"Then you ought to; a landlord poorly off is in a bad case in these days; and I want things kept as they are, Paul. I've not lived at Rudham, but I've kept my eye on it all the same; and what you call progress, and its attendant abominations, has not hurt it much yet. I made a mistake when I let the bishop nominate a successor to the living when old Gregg died three years ago. Curzon's a go-ahead fellow, from all that I hear; I don't want a go-ahead squire."

"I'm afraid you've made another mistake, and, if there's time, you had better undo it," said Paul, gravely.

"Do I look like a man who can re-arrange all his matters?" asked the Major, irritably. "After all, what I ask of you is no very hard thing to grant; simply to accept the good the gods provide, and let well alone."

"But that for me is an impossible condition," said Paul. "I cannot let things alone if I feel that I can better them. I'm in no way fitted for a country squire; I've been brought up on different lines from you, and arrived at very different conclusions. I am grateful to you for your thought of me, but I want to live my own life unfettered by any conditions."

"And this is how you show your readiness to carry out any wish of mine?" said the major, bitterly.

"I'm sorry; but I promised in the dark, not knowing that my principles would be involved."

"I'm glad to hear you have any. May I ask what you call yourself? A Lessing who is not a Conservative is not worthy of the name."

"I scarcely know what I am; but my friends call me a Socialist."

"Then in Heaven's name, I've made a bigger blunder than the last!" said the squire, with an odd thrill in his voice.

"It's not my fault; and there may still be time to undo it," said Paul, rising, for the flush that crept to the major's temples warned him that the interview had been too long and too exciting. "I would thank you, if I could, for the thought of me, and I am sorry to have been the cause of disappointment, but it would not have been honest to hide my opinions."

"No; you've been honest enough, in all conscience. If there's yet time——" He broke off, turning away his head, and taking no notice of Paul's departure.

All that night Paul paced his room in deep thought. The scene he had witnessed had stirred him more than a little; and it grieved him to his heart that he had so seriously disturbed the last moments of a dying man.

"But I could not have hoodwinked him," he thought; "no honest man could. But to-morrow I'll prove to him that I am ready to help him in any way that I can. If he will only talk quietly, and keep his temper, he could surely suggest some more fitting heir than I; and the business details could be fairly quickly settled if I could take down his wishes and see his lawyer. He must yet have several days to live, I should think, with his extraordinary vitality of brain."

At a very early hour the following morning, therefore, Paul presented himself again at the house in the square, with the request that he might have a short interview with the major.

"Very sorry, sir," said Smith, with an added gloom of manner, "but my master's much worse; they don't think he'll live through the day. He was very restless last night; and nothing would satisfy him but that I should go off in the middle of the night and fetch Mr. Morgan—the lawyer as wrote to you, sir; but when I got him here my master had lost his power of speech. He knew Mr. Morgan quite well, but he could not make him understand what he wanted."

"And now?" asked Paul, pitifully.

"The doctor is just coming down the stairs, and will speak to you, sir."

Paul went out into the hall to meet him. "How did you find the major?" Paul inquired.

"Dead," replied the doctor, drawing on his gloves. "He died as I entered the room."

"RUDHAM, Sunday Evening.

"DEAR SALLY,

"I did not, until now, believe myself a creature of impulse. That I am one is proved by the fact that, as I dropped my last letter to you into the post-box, I made up my mind to run down here and have a look round; and here I am. My surroundings I will describe later. I told you I had decided not to go to poor old Major Lessing's funeral for various reasons. I have a horror of humbug; and to pose as sole and chief mourner at the funeral of a man who had made me his heir by a fluke, and if he had lived an hour longer would have altered his will, seemed humbugging, to my mind. Also the funeral service, beautiful as it appears to those who can believe in it, means absolutely nothing to me; and I have scruples about appearing as if it did. Two surprises awaited me at Rudham: first, that by the same train by which I arrived Mrs. and Miss Webster got out upon the platform; and the beauty who fascinated you 'all of a heap' at Brussels, turns out to be the tenant of Rudham Court—my tenant, in fact!—a judgment upon me, you will say, for my unreasoning prejudice. Secondly, the extreme difficulty of getting a night's lodging, unless your character and circumstances are well known, was borne in forcibly upon my mind! An under-gardener of Mrs. Webster's took me up in the cart which carried your charmer's luggage.

"Judging by the size and number of the boxes, beauty needs a great deal of adorning, by the way! Then I was handed over to the village blacksmith, and, under the shelter of his name, I persuaded a Mrs. Macdonald to take me in. You would describe her as 'quite a darling!'

"She and her husband are Scotch by birth, and still retain the soft intonation and pretty accent. They have no children—indeed, Mrs. Macdonald informs me that they have not long been married; and she must be fifty, and 'my John,' as she calls him, some ten years older; but I have never seen two people more in love with each other. If surroundings are an index to character they must be very nice people indeed. Let me try and describe my room, which is furnished with the solid simplicity of a hundred years ago. A grandfather clock ticks solemnly in the corner, two oak chairs stand on either side of the fireplace, with down cushions in print covers on the seats—a concession to modern luxury. In place of the cheap modern sideboard an open oak cupboard, whereon are displayed my dinner and tea-things, furnishes one side of the room, leaving just sufficient space for two Windsor chairs, polished to such a dangerous brightness that to sit upon them without sliding off requires more careful balance than to ride a bicycle. An oak table with twisted legs, and flaps that let up or down at will, is in the centre of the room. One almost expects clean rushes strewed upon the floor; instead there is linoleum of a neat design—black stars upon a white ground; and Mrs. Macdonald prides herself not a little upon the far-sighted policy that made her decide upon linoleum rather than carpet.

"'It can be wiped over with a damp cloth every day, sir, and kept sweet and clean; and if you're feet are cold, I'm not saying that I'll mind your putting them on the rug, although I made it all myself'—which was kind of Mrs. Macdonald! My attention being thus drawn to the hearthrug, I discover that it's a work of art, in its way, knitted in with rags and tags of cloth, grave or gay in colouring, but harmonious in the general effect. You will think that I am developing a passion for detail, but it is rather that I wish to photograph exactly my first impressions of the place. There seems a primitive simplicity about it that must vanish at the first touch of modern progress like a pretty old fresco exposed to the light, and I feel myself like a traitor in the camp. If I decide to live here I shall probably be the motive force that will set the ball of progress rolling. Life here is almost stagnant, I fancy, unlike the river, which runs swift and strong along the side of the village. It separates from, rather than connects it with the outer world, for there are dangerous currents which make it not too safe for navigation; and to cross it you must either go to the ferry, half a mile off, or make for the bridge at Nowell four miles away. I found out all this by a stroll after tea, last evening, and a gossip with my new acquaintance, the blacksmith Allison. Gradually the talk turned to things parochial, and I discovered some characteristics of the go-ahead parson, whose appointment to the living my godfather gently deplored; and this was how it came about. A tall, powerful-looking man came swinging down the road at a brisk pace, nodding in quick, alert fashion to one and another as he passed, recognizing me as a stranger, but bidding Allison a cheerful good night as he passed on in the direction of the inn. By his dress I knew he must be the parson of the place. Allison, who had acknowledged his greeting only by a sideways nod, gave a grunt of assent when I asked him if it were so.

"'Curzon,' he said; 'that's his name, a meddlesome chap, if ever there were one! Now the last rector were a real gentleman! You could please yourself about going to church or staying at home; but he were wonderful kind in sickness and such.'

"'And you miss the attention, I daresay?"

"'Well, I'm not saying that exactly. Mr. Curzon's wonderful took up with the sick folks and children, but it's us well ones he can't leave alone. His work's never done, as you may say. Now what do you suppose he's after to-night?' in a tone of angry argument.

"'I really can't guess.'

"'No; it's not likely you would. He makes believe as he's gone for a walk, but he'll be turning back again about such time as the men are turning out of the public there! Then, come next week, he'll be droppin' into one cottage or another about such time as the man comes in from work, and it'ull be, 'So and so, I'm afraid you had a glass too much on Saturday night. I wouldn't do it, if I was you;' and then he's sure to put in something about coming to church on Sunday."

"And do they?' I asked.

"'Some on 'em. Most of 'em, if I speaks the truth, gets tired of being told of it, I think, and goes just to pacify him, as you may, say; but I don't hold with it myself.'

"Apparently this faithful shepherd does succeed in driving a very large proportion of his flock to church on Sunday. Allison and I are distinctly in a minority. I was nearly being carried there forcibly myself to-night; and I only escaped, I believe, because Mrs. Macdonald has evolved, from the label on my portmanteau that I am the coming squire, and must be allowed some liberty of opinion.

"'You'll be going to church to-night, sir,' she said, beginning the attack with gentle firmness. 'John and I lock up the house and hide the key under the mat, in case you come back before we do. We have a walk these summer evenings when church is over.'

"'Thank you, Mrs. Macdonald, you can leave the key in the door; I have writing to do.'

"'But you'll be going to church, for sure; you were not there this morning, I'm thinking, and the rector's sure to say something of him that's gone.'

"I had not the courage of my opinions, like Allison. How could I grieve the kindly eyes that looked into mine? So I took refuge in weak evasion.

"'I've been over-worked and over-worried, Mrs. Macdonald, and my head aches, and I need rest and quiet.'

"'Well there, sir; you'll forgive my making so bold, but it will grieve the good man, if he knows you've come. And there's a-many will be disappointed not to catch a sight of you, besides.'

"'Whom do you mean by the good man?'

"'There now! it slipped out without thinking. But it's what my John and I call Mr. Curzon, for we've never come across such a one as he.'

"'And why am I to be a sort of show to the others?' I asked with some curiosity.

"'Ah! Because some of them begin to guess now who you are—not that John nor I are much given to talk. But when a neighbour asks your name, we couldn't keep it no longer—could we, sir?'

"'Certainly not. And they will all see me sooner or later, though it won't be at church to-night. I hope soon to know every one in the place.'

"So finally I've been left in charge of the cottage, and have been writing ever since this long rigmarole to you. Mrs. Macdonald's words have given me food for reflection, and, the more I reflect, the more fully convinced I am how thoroughly unfitted I am to fill the place allotted to me. Had Major Lessing left me money enough to carry out my own wishes, I should have been inclined to put his property in the hands of a capable, fair agent, and do with it as Major Lessing suggested, and keep things very much as they are; but I find that I shall have little independent income apart from the property. To keep things in really working repair I shall probably have to raise the rents—which are absurdly low—which, of course, will be a very unpopular movement; and my being willing to live as simply as any of my tenants, will not in the least soften their feeling towards me. I shall not do anything in a hurry, but I shall first try and master my position. After so many years of a non-resident squire of a strictly conservative type, there must be need for improvements; but here again comes in the question of money. I am afraid that trip abroad must be put off for the present. How would it be for you to come here for a bit? I will sound Mrs. Macdonald on the subject to-morrow. If I undertake the management of things here myself, you would help me with accounts, etc., and I could take you on as my paid secretary! However this is looking too far ahead. I will keep this letter open and tell you the result of my advances to-morrow."

"Monday Evening.

"I approached Mrs. Macdonald with much diplomacy this morning. She gave me the opening I sought by saying, when I ordered my dinner—

"'I suppose you'll be leaving to-day or to-morrow, sir.'

"'On the contrary, you are making me so comfortable, that I was going to ask you to take me on for a few weeks, at any rate.'

"'But it isn't right or fitting that the likes of you should be living in a cottage such as this. The whole place belongs to you, I'm thinking.'

"'I suppose it does. But if I come to live here I shall start either in a cottage, or quite a small house, with a sister of mine who has no home, poor child! How she would like to join me here, by the way.'

"Mrs. Macdonald played nervously with the string of her apron. I could see I had appealed to her motherly heart by representing you as a motherless orphan.

"'I suppose you haven't a second bedroom,' I suggested, following up my advantage.

"'It's a slip of a thing; not fit for a lady, sir.'

"'After all, ladies are much the same as other women; and my sister might have the bigger bedroom and I the smaller.'

"'There's my John,' doubtfully.

"'Doesn't he like ladies?'

"'Not all of them, sir,' with a sudden burst of confidence. 'There's Mrs. Webster; she called here one day to know if I'd take in some of the washing—and he'd just come in from work,—and she marched into the kitchen and talked very loud. Though he's deaf he don't like no notice taken of it; and he told her it 'ud be time enough for me to work when he was laid by, and then he'd be sorry if I had to do it.'

"'But, of course, if Macdonald does not like us we will leave at once,' I said, assuming that Mrs. Macdonald had agreed to have you. So you're to come, Sally; come as quickly as you can. Don't bring much luggage, for there is nowhere to put it; and pray remember to talk gently to our host. I cannot see why we should not double the size of this cottage—put in a bath-room, and get Mrs. Macdonald to do for us; but this will entirely depend upon your manners, you see. I was preparing to go out, when I saw a child's invalid carriage barring the entrance to the gate, and a child's clear voice was giving very impressive orders about the contents of a certain basket which was to be carried up to the door.

"'You won't spill them, Nurse. You'll be sure not to spill them; they're so very ripe they'd burst if you did.'

"'No, darling; I'll carry them as carefully as new-laid eggs.'

"The woman spoke like a lady; her tone was so gentle and refined.

"I was standing at the open door of the cottage, and went down the path to meet her, asking if I could take in the basket to Mrs. Macdonald.

"'But they are not for her; they're for you. But I'm afraid you're better and don't want them,' said the voice from the carriage outside.

"'Whatever is inside that basket I'm sure to want,' I said, going out to my odd little visitor; 'but I don't quite know why you are so kind as to bring me things. I'm afraid there's some mistake; I shall be so disappointed if there is.'

"The blue eyes that looked up into mine began to smile.

"'Shall you really? There can't be any mistake, because last night, as Nurse wheeled me out of church, I heard daddy talking to Mrs. Macdonald; and she said she'd got the new squire at home, but he'd a dreadful headache and couldn't come.'

"I could scarcely help laughing; I certainly had not intended my words to be accepted so literally.

"'Who are you?' I asked, 'and what's in that basket? It wouldn't be manners to peep inside, would it?'

"'Oh yes, it would,' with a delighted giggle. 'I'm Kitty—Kitty Curzon,—and daddy says it's my work to look after any one who is not well; and I'm to think what they will like, and take it to them. So, when I heard you had such a bad headache, I got Nurse to gather my last red gooseberries—they are very, very ripe,—and I've brought them for you; and can I have the basket, please?'

"'Well, I can't accept them on the plea of headache: it's gone, you see; but perhaps you will be so kind as to leave them all the same, for if there is one thing I like more than another——"

"'It's gooseberries,' interposed Kitty, eagerly; and I nodded assent.

"The child shot a triumphant glance at Nurse.

"'She said you would not want them, and I'd better ask daddy; but he likes me to think of things by myself. And then at the end of the day I tell him where I've been; and he'll be so surprised to-night, for he didn't know I'd heard about you.'

"I carried off the basket, and brought it back, presently, empty.

"'I have not half thanked you, Kitty; but I am most grateful. How old are you, I wonder?'

"There was a moment's hesitation. 'I'm not young at all; I'm nine, although you'd never think it, because I'm so small. Daddy says running about makes you grow, and I can't run.'

"'Her back is not strong, sir,' said Nurse, hurriedly; and as I looked at the recumbent figure, I saw that the poor little child was deformed. It seemed a terrible pity, for the face and head are singularly pretty.

"'That's why daddy says I must think of all the ill ones, because Nurse and he think so much about me.'

"'Very well. I shall be sure and send for you directly there is anything the matter. I fancy you would do me more good than a doctor. And I've a sister coming, before long, and she will want companions. You will have to come to tea.'

"'Is she as old as I am?'

"'A little older, I think.'

"'I'll come if daddy will let me; but Nurse must come too.'

"'By all means, and if you have any little brothers or sisters——'

"'I have not any. There's only me,' interposed Kitty, shaking her head.

"'I wonder what her name is?'

"'My sister's, do you mean? Sally. Rather a nice name, isn't it?'

"Evidently Kitty did not like it much, for she said she must be going; and went on her way, kissing her hand graciously, so I took off my hat and waved it.

"From Mrs. Macdonald I gather that my first visitor is Mr. Curzon's only child. He is a widower, it seems, and Kitty is the cause of his holding a country living. By my landlady's account he is simply wrapped up in her. I have been the round of the village to-day, making acquaintance with one and another as occasion offered. As I conjectured there seems plenty to be done; and it must be some months before I can stir hand or foot, before I can get things even into my own hands—not that the people here realize this in the very least. Indeed they are intellectually dead; they seem to possess no ambition of any sort.

"I went into the parish church on my way home. It is an interesting one, built about the end of the thirteenth century, with a magnificent tower that one can see for miles round. I found a great many monuments to the Lessings—a very virtuous lot, if their memorial tablets are to be trusted. The church has been carefully restored—quite recently, I fancy, by the look of it. Then I went into the churchyard, where a newly-filled-in grave showed me where my poor godfather had been laid. The sacristan, a very old, infirm man was putting it tidy; and to my astonishment I saw a low vase of white flowers placed in the very centre of the grave.

"'I suppose I am not mistaken,' I said. 'This must be Major Lessing's grave?'

"'Yes, sir.'

"'And who put the flowers?'

"'Miss Kitty, the little maid at the rectory. She said she'd thought he'd be lonely without any;' and the sacristan straightened his back with a little smile.

"'I hope you don't mind,' said a voice behind me. 'I've a notion your relative did not like flowers at a funeral, but I could not upset Kitty's conviction that he did.'

"It was the rector who had come upon me unawares, and he did not pretend not to know me.

"'What can it matter now?' I answered. 'He'll know nothing of it.'

"But I must stop, I've no time to describe the good man. Come and see him for yourself.

"Ever yours,

"PAUL LESSING."

The man who some centuries earlier had built Rudham Court, had been wiser than the generation in which he lived in his choice of a site. Instead of a valley he had chosen the side of a hill, and the sloping foreground had been levelled into a succession of terraces, giving the impression of an almost mountainous ascent to the house from the road which lay beneath. The house, not beautiful in itself, was softened by the hand of time into a dull red that contrasted harmoniously with the group of trees behind it, and the gravelled terrace in front with its box-bordered beds was a blaze of colour in the brilliant sunshine of the August morning. It was bordered by a low stone wall along which two peacocks strutted with almost ridiculous self-consciousness of their beauty. In the very centre was a flight of steps which descended to the bowling-green beneath, where the yew hedge which grew round it had been fantastically cut into the shape of an embattlemented parapet, framing the distant view into a series of charming little pictures: here a glimpse of the river, there a delightful vignette of the church.

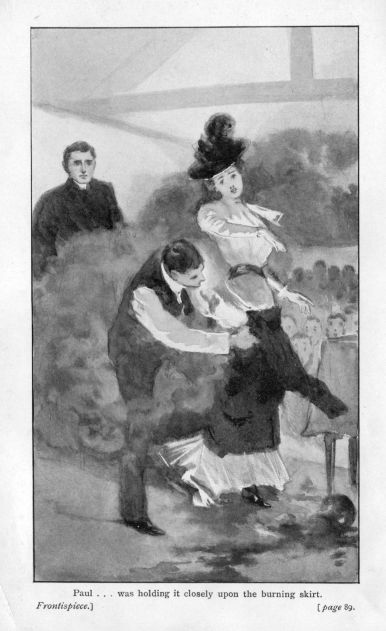

Across the velvety turf of the green tripped Rose Lancaster, dangling a basket from her arm, a picture herself in her pink cambric frock and befrilled apron, a little French cap set upon her head which enhanced the beauty of the golden hair. Her skin was of the delicate colouring that so often accompanies fair hair, the mouth generally wore a smile displaying Rose's pretty dimples, and the great blue eyes were half concealed by the long lashes. She made her way to the wicket-gate at the far end of the green, to a winding path through a wood which led to the rose-garden below, and gave a start of pretended surprise when Tom Burney broke off from his task of mowing the grass paths which separated the beds, with an exclamation of delight.

"You here!" said Rose, who had watched the direction of his steps from a window above. "I've come after some roses, if I can find any. Nothing satisfies Miss Webster but roses on the mantel-shelf of her sitting-room, and it does not matter to her whether they are in season or out. Roses she must have. Are there any coming on, Tom?"

"Bother the roses!" said Tom, impatiently. "You've been back nearly a fortnight, and have not spoken a word to me yet."

"That's ungrateful. I walked to church with you on Sunday evening, and I told you lots of things I did when we were away."

"Dixon joined us, and you let him!" said Tom, angrily.

"How could I help it?" Rose answered, arching her pretty brows. "I could not say I didn't want him, could I?"

"Are you going to walk with him or me, Rose? I asked you before you went away, and I want to know now."

Rose meditatively clipped off a bud, crying out a little as a thorn pricked her finger, holding out the injured member for Tom to look at; but he looked over it at her, a flush on his handsome face.

"It may be play to you; it isn't to me," he said, his voice shaking a little. "Did you get the letter I wrote?"

"I don't know; I forget. I had a lot of letters. Yes, I expect I did."

"And you didn't trouble to answer it?"

"It's clear you don't know what a lot a lady's maid has to do when she's travelling," said Rose, petulantly. "It's 'Lancaster' here and 'Lancaster' there, and you've no sooner packed up than you begin unpacking again. What time should I get for answering letters?'"

"I wanted to know if you'd thought over what I said?"

"You can't expect me to remember what you said six weeks ago."

"You do remember, only you don't want to give a straight answer. That's about it," said Tom, bitterly.

"I like walking with you both, though not together. There!" cried Rose, with a defiant toss of her head. "I'm young; I don't mean to be tied!"

"But you'll care for the one who loves you best, and that's me!" burst out poor Tom. "Dixon may be smarter, and he's a deal better off; but he's a glib sneak, and I know it. I'll wait three months, and then I'll have my answer; and if it's 'No' I'll be fit to drown myself," and Tom's voice broke off in something very like a sob.

Rose was flattered but frightened at realizing her power over the lad. It was like a book, that he should threaten to drown himself for love of her; but of course he did not mean it. She was sorry for him; when she was with him she almost believed she loved him, but at any rate she need not decide now. Three months hence she might know her own mind.

"Well, we'll wait three months and see what happens; and meantime I do hope you'll be careful not to quarrel with Dixon."

"I shall if he comes in my way," declared Tom, sturdily. "I don't wonder he wants you himself—any man would; but he should play fair."

"He's no quarrel with you; he said you were a decent sort of a lad, the other day."

Tom clenched his fist involuntarily. "That's just it!—he's always trying to run me down in your eyes. A lad, indeed! I'm a man who wants the same girl he does, and that's yourself, Rose."

Rose laughed gaily; it was nice to find herself so much in request.

"Man or boy, I can't stay talking to you all day. Pick me any roses there are, and let me go. I believe" (in a lowered undertone) "that I hear the ladies talking up there on the bowling-green. They've come out to sit in the shade, I expect."

Rose's conjecture was right, for, as she went back to the house, she caught a glimpse of Miss Webster and her mother seated under the large tree at the far end of the lawn.

"How pretty she is," said May Webster, following her retreating figure with lazy eyes. "As pretty as the roses she carries. I do hope she won't get snapped up at once. She is a pleasant little thing to have about one—which reminds me, mother. I saw a pretty girl of a different type in the village yesterday, whom I believe to be Miss Lessing. What are you going to do about her and her brother?"

"Nothing at present, I think. One really can't leave cards on a cottage!"

"But you might on the people in it. We can't very well ignore the squire of the place who is also our landlord."

"It will be time enough to recognize him when he behaves like other people."

"I don't see that he's a bit more peculiar than the University men who take to slumming. Anybody may do anything nowadays," May said with a little laugh.

"He doesn't even come to church," persisted Mrs. Webster.

"A weakness shared by many men."

"But his sister might and ought," replied her mother, severely.

"Mr. Curzon seems to think it equally necessary for men and women," said May, mischievously.

"Oh yes. Of course he's a dear good man, and I wish we were all like him, but we aren't," answered Mrs. Webster, resigning all hope of anything but moral mediocrity with a gentle sigh. "He says Mr. Lessing is a very nice fellow; but you can't quite rely on his opinion: he's a good word for every one."

"Which is delightful, but not amusing; and one does need amusement, mother. Suppose we call at the cottage and follow up the call by an invitation to dinner. We might ask the rector to meet them."

"The worst of asking the rector is that he always wants something," said Mrs. Webster, a little plaintively.

"That we haven't got?"

"Oh, May, you know quite well what I mean! It must be the heat that is making you so argumentative. Mr. Curzon always has some pet hobby on hand for which he wants money, and of course he ought to have it; but really, just now, what with a trip abroad, and the London house to paint and paper throughout, I've not so much in hand as usual."

"Enough for the rector's last hobby, I dare say. At any rate let's risk it. If we all air our different views we might have an exciting evening."

"I wish things were as they used to be. The old major was such a thorough gentleman. It was quite a pleasure to give him a bed or dinner when he came down."

"Is not this man a gentleman, then?"

"Oh, my dear, I hope so; but he has queer views, if all I hear be true. I'm sure, if he says anything at dinner about our being all equal, I shan't be able to hold my tongue. We never were and never can be."

"I believe Mr. Curzon thinks we are; only he likes poor people much the best. He says the truest gentleman he ever came across is old Macdonald."

"Now it is wild talk like that that makes me sometimes distrust Mr. Curzon; and he ought to know better, being of such good family himself," said Mrs. Webster, fretfully. "Is it not at the Macdonalds that the Lessings are lodging? As you seem to wish it, we will call this afternoon."

Paul Lessing was out when the smart carriage and pair drew up at the Macdonald's cottage in the course of the afternoon; and Sally had to receive her two visitors alone. Mrs. Webster's ample presence seemed to fill the tiny sitting-room; but she placed herself graciously enough in one of the cushioned elbow-chairs, whilst May subsided into the slippery Windsor as gracefully as if it were the softest sofa. There was something about Sally that pleased her; it may have been a certain originality and freshness of manner, or the unconscious admiration that shone in the dark eyes. Nothing in its way pleases a handsome woman more than the admiration of her own sex. Be this as it may, May Webster laid herself out to charm, and did it very successfully, and by judicious management prevented her mother from asking any leading questions as to Mr. Lessing's future line of conduct. Mrs. Webster's small talk so often took the line of asking questions.

Paul was not properly grateful when he found the cards upon the mantelshelf.

"It's a dreadful bore; but I'm afraid it can't be helped. You can return the call sometime, and there will be an end of it."

"There may be for you, but there won't be for me!" said Sally, with some spirit. "I'm catholic in my choice of companions, and mean to include everybody who cares to know me. Mrs. Macdonald is charming, and Allison amuses me, and Mrs. Pink and I have made friends over the baby; but why I should refuse a proffer of friendship from Miss Webster, because she happens to be a beauty and dresses well, I don't exactly see!"

"Friendship!" echoed Paul, scornfully. "How little you know of smart people and their ways. Friendship with them means a stepping-stone to higher things; your means and your position must give them a leg up in the world. Now we have neither."

"You are shaking my faith in you, Paul. You are judging without knowing."

"I am not judging the Websters individually—only the class to which they belong; of which I do know something, and you nothing."

"Well, I think I will learn for myself then!" cried Sally. "I'll start by believing people as nice as they appear, until I find them otherwise."

"And are Mrs. and Miss Webster 'nice,' as you call it?" asked Paul, his curiosity overcoming his vexation.

"I did not like Mrs. Webster much: the room did not seem big enough to hold her."

"I told you so!" said Paul, triumphantly.

"Oh, Paul! you might be a woman," replied Sally, with mocking laughter. "But listen; Miss Webster is as nice as she looks! Can you want more?"

"It's a good thing to be young and enthusiastic."

"Certainly better than being old and cynical," retorted Sally, saucily.

The next morning's post brought a crested envelope, directed in a dashing hand, to Sally, inviting Paul and herself to dinner at the Court on the following evening.

"We shall be simply a family party," wrote the lady; "but, with such near neighbours, I thought it more friendly to invite you for the first time quite informally."

"You don't want to go!" exclaimed Paul, who felt the meshes of the society net closing round him.

"Of course I do. I want to see your house, and to feel what it would be like to live there."

"I don't believe you have a proper frock to go in. A coat and skirt won't do."

"What nonsense! I've an evening dress, of a sort; and they don't invite my frock, but me!"

"We'll go, then, as you've set your heart upon it; but I feel as if it were the letting out of water."

Certainly Paul had no reason to complain of Sally's appearance when she came down ready dressed for her dinner on the following evening. In her simple white dress, cut away at the throat, with a soft muslin fichu tied in front with long ends falling to the bottom other skirt, she looked, as old Macdonald afterwards remarked to his wife, "as a lady should:" fair, and fresh, and young. Her dusky hair waved prettily upon her forehead, and half concealed her ears; the face it framed was not, strictly speaking, pretty, but it was bright and animated, and the dark eyes and eyebrows were handsome.

"I've won one person's approval at any rate," said Sally, merrily, as they started on their way. "I went in to bid Macdonald good night, and Mrs. Macdonald said, as she helped me on with my cape, that 'my John' likes ladies to wear white dresses and have pale faces. He could not abide colour, except in flowers."

"Then you are fulfilling your mission, Sally, and winning your way into Macdonald's good graces. We shan't be turned out."

"It's my first dinner-party, Paul. Do you realise the importance of the occasion? I've had no coming-out like other girls."

"That's why you are so much jollier than most of them," said Paul, betrayed into a compliment.

From the moment they entered the drive-gate, and began the ascent to the house, Sally looked about her with eager interest, breaking into exclamations of delight as each step revealed some fresh beauty to her eyes.

"It's a dangerous experiment to have brought you. You will be horribly discontented with Macdonald's, after this."

"I shan't. But if this place were mine, I should live here, and make it a joy to everybody about me. I would not want to keep it to myself," Sally said—

But the front door was reached, and a footman was at hand to help her off with her cloak; and in another instant the door of the long drawing-room was thrown wide, and Sally, with the un-self-consciousness of simplicity, heard herself announced, and found her hand in Mrs. Webster's, who retained it as she led her on towards a tall, handsome man who stood talking to Miss Webster.

"Mr. Curzon, allow me to introduce Miss Lessing. You've been away with your little Kitty, so I don't think you've met each other yet."

Then Sally realized that she stood face to face with the good man, and that he was to take her in to dinner, so that she would have time to consider him carefully. Mrs. Webster placed her hand graciously on Paul's arm when dinner was announced, and May trailing yards of amber-coloured silk behind her, sailed in by herself.

The dinner-table was oval, and Sally found herself seated between the Rector and May; on the other side sat Paul, with Mrs. Webster and May to talk to alternately. The very perfection of her surroundings engaged Sally's attention at first: the delicately shaded lights shining down on the dainty flowers, and silver and glass; the dinner, remarkable rather for elegance than profusion; the family portraits on the wall, bewigged and befrilled, which stood at ease, and glanced down on the company with a sort of haughty indifference; the heavy, handsome furniture combining beauty with comfort; and last, but not least, May herself, whose beauty in her evening dress was simply dazzling.

Paul, reduced to commonplaces, was asking Mrs. Webster if the place suited her.

"A leading question, Mr. Lessing," she answered, with a sort of heavy playfulness. "I've no doubt you would be glad to hear it did not. But we are so fond of it, May and I; it's just the country place we want for the summer months. We are always in London for the season. But our lease is nearly run out, you know; and then, I'm afraid, naughty man! you will not let us renew it."

"Why not? I'm not likely to get better tenants," said Paul, politely.

"But you may be wanting to live here yourself, you see."

"Such a plan is very far from my thoughts at present. I neither wish, nor can afford it."

"But where else can you go?" asked Mrs. Webster, as if her life depended on the answer.

The plea of poverty must be ignored; it was only advanced because Mr. Lessing was her landlord!

"I've not decided yet. Sally and I are quite happy where we are."

"But you could not go on like that. It hardly seems right, you know."

"I don't see where the wrong comes in."

"Your very position as squire; you will be expected to be an employer of labour, you see."

"So I suppose I shall be, in time, although perhaps not about my house and garden. There are a great many things that will have to be done in the place when I get my affairs into order."

"Ah yes, of course; it's wonderful how the money flies. Here's Mr. Curzon insisting that the schools must be enlarged; I expect you are like him, and think that everybody ought to know everything, and that each child must have so many cubic feet! I'm sure I can't cope with it all. I only know we, who are a little better off, have to pay for it. He wants me to give a hundred pounds, and I tell him I really can't: fifty is the utmost, and that is more than I can afford. I advise you to keep clear of him to-night; he's sure to ask you to subscribe a similar sum."

"It's a voluntary school, I suppose?" said Paul, glancing across at the rector. "I could not subscribe to that; I'm in favour of a board school, you see."

Sally, looking from one to the other scented trouble, for Mr. Curzon broke off in the middle of a sentence, and his smiling, kindly face grew grave as he gazed steadily back at her brother. There was a moment of uncomfortable silence.

"I was going to call and discuss the matter of the school with you," said Mr. Curzon, at last; "but I did not mean to introduce the subject to-night."

"Of course not. We could not possibly allow it; could we, mother?" interposed May, with an air of relief. "I feel at the present moment we all need more cubic feet. It's so very hot; I almost think we could sit outside." And as she spoke a general move was made for the terrace, where seats and tables were arranged.

As neither of the men took wine they did not stay behind; and May, who was clever enough to see that they were both ready to show fight for their individual opinions, engaged Paul in conversation, whilst Mr. Curzon carried off Sally to see the bowling-green by moonlight.

"I never saw anything so quaintly pretty," Sally said. "The yew hedge with its succession of views suits it exactly."

"Yes, doesn't it?" replied her companion. "This is naturally my favourite;" and he paused at the opening where, below, the church stood out grand and stately against the evening sky. "Is it not a grand old tower? It stands just as a church should; it dominates the place."

The ring of enthusiasm in his voice brought an answering thrill into Sally's heart.

"Are you sure that it does really?" she asked, moved by a sudden impulse.

"I hope so; I pray God it may be so. If not in my time then in another's."

"I can't think why you, or any reasonable man, should object to a board school?" said Paul, who had been expounding his views at some length to the rector. "The people should have a voice in the matter of their children's education; and it can't be fair that any particular system of religion should be forced upon them. In a place like this you would be pretty certain to come out at the head of the poll, and, if religious teaching seems such an essential, you would be allowed to give it with limitations."

"With limitations that would practically make it useless," said Mr. Curzon. "I am prepared to make any sacrifice rather than surrender the religious training of the children God has given to my care. It will be a hard matter, with you against me, but I must stick fast by my principle."

"In a few more years there won't be a voluntary school left in the country," said Paul.

"Mine shall be one of the last to die," replied Mr. Curzon.

"You are fully persuaded that you are carrying out the wishes of your people."

"I am sure that, as far as I know it, I shall be doing my duty by them—and that must come first; but they shall have an opportunity of expressing their opinion. I am going to call a meeting about the enlarging of the school, and I shall try and persuade every one to attend it."

"Including myself?" inquired Paul, with a rather sceptical smile.

"I shall wish you, of course, to be there."

"But I can only be there in opposition to your views," Paul said.

"A clergyman gets used to opposition," replied Mr. Curzon, quietly; "but if the school is to be continued under the management of myself and my churchwardens, it shall be no hole-and-corner business: it shall be with the consent and confidence of the majority of my people."

Paul rose to go; and there was rather a troubled look on his face as he took Mr. Curzon's out-stretched hand. It was such a kindly, friendly grip.

"I'm afraid we cannot help coming across each other as we both have the courage of our opinions; but at least you will believe that I have the social development of the village very near at heart."

"And there, at least, we agree," said Mr. Curzon, smiling; "but with me their spiritual welfare is even more urgent."

Kitty's little carriage was drawn up at the door, as she was just returning from an outing. She greeted Paul with a beaming face, which, as he came closer, grew clouded with anxiety.

"I'm afraid you've got another headache, and I've got nothing to bring now," she said. "Blackberries wouldn't do. They are rather nasty, daddy thinks."

"I've not got a headache, Kitty, thank you," said Paul, leaving the question of blackberries in abeyance. "What made you think I had?"

"You were frowning; but perhaps it was the sun in your eyes. Has your sister bigger than me come yet?"

"Oh yes; she has been here quite a time, and you have not been to see her."

"I've been away; did not you know?—away with daddy," with a proud glance up at her father. "It was lovely; he had no one to think of but me, and I was with him on the beach nearly all day long."

"Ah, that's how you come to have such roses in your cheeks. Well, when are you coming to have tea with Sally and me? You shall choose your own day."

"Would to-morrow do? It's Sunday; and daddy likes me to have all the happiest things on Sunday. But I forgot; Nurse was to come, too, but she goes out on Sunday afternoon."

The sweet-faced woman who wheeled Kitty about gave an amused little laugh.

"It would be rather nice for you to go this once alone, Miss Kitty; and I could wheel you there on my way out——"

"And Sally and I could bring you home. Would not that do?" said Paul to Mr. Curzon.