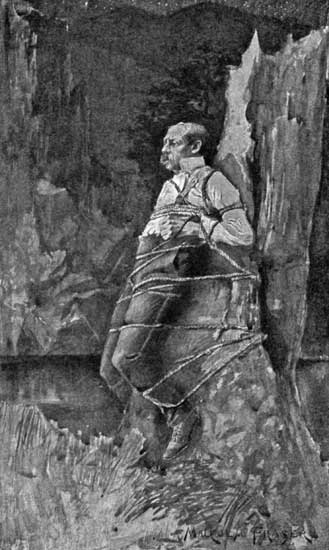

HE WAS PALLID AND PANTING see page 221

Project Gutenberg's The Young Mountaineers, by Charles Egbert Craddock

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Young Mountaineers

Short Stories

Author: Charles Egbert Craddock

Illustrator: Malcolm Fraser

Release Date: January 15, 2007 [EBook #20365]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE YOUNG MOUNTAINEERS ***

Produced by Dave Macfarlane and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

| He was Pallid and Panting |

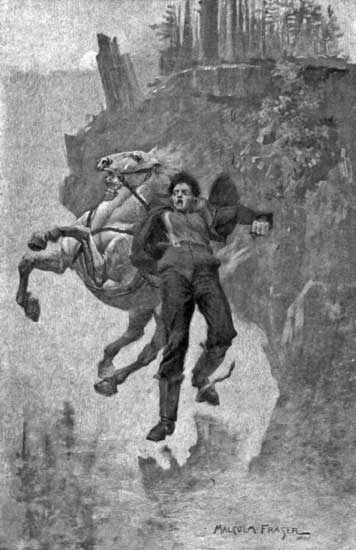

| Together they went over the Cliff |

| How Long was it to Last |

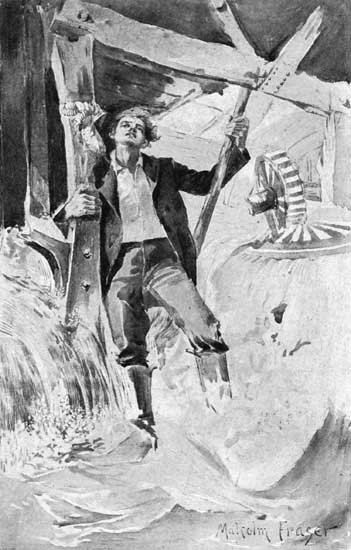

| In the Midst of the Torrent |

Picture to yourself a wild ravine, gashing a mountain spur, and with here and there in its course abrupt descents. One of these is so deep and sheer that it might be called a precipice.

High above it, from the steep slope on either hand, beetling crags jut out. Their summits almost meet at one point, and thus the space below bears a rude resemblance to a huge window. Through it you might see the blue heights in the distance; or watch the clouds and sunshine shift over the sombre mountain across the narrow valley; or mark, after the day has faded, how the great Scorpio draws its shining curves along the dark sky.

One night Jonas Creyshaw sat alone in the porch of his log cabin, hard by on the slope of the ravine, smoking his pipe and gazing meditatively at "Old Daddy's Window." The moon was full, and its rays fell aslant on one of the cliffs, while the rugged face of the opposite crag was in the shadow.

Suddenly he became aware that something was moving about the precipice, the brink of which seems the sill of the window. Although this precipice is sheer and insurmountable, a dark figure had risen from it, and stood plainly defined against the cliff, which presented a comparatively smooth surface to the brilliant moonlight.

Was it a shadow? he asked himself hastily.

His eyes swept the ravine, only thirty feet wide at that point, which lies between the two crags whose jutting summits almost meet above it to form Old Daddy's Window.

There was no one visible to cast a shadow.

It seemed as if the figure had unaccountably emerged from the sheer depths below.

Only for a moment it stood motionless against the cliff. Then it flung its arms wildly above its head, and with a nimble spring disappeared—upward.

Jonas Creyshaw watched it, his eyes distended, his face pallid, his pipe trembling in his shaking hand.

"Mirandy!" he quavered faintly.

His wife, a thin, ailing woman with pinched features and an uncertain eye, came to the door.

"Thar," he faltered, pointing with his pipe-stem—"jes' a minit ago—I seen it!—a ghost riz up over the bluff inter Old Daddy's Window!"

The woman fell instantly into a panic.

"'Twarn't a-beckonin', war it? 'Twarn't a-beckonin'? 'Kase ef it war, ye'll hev ter die right straight! That air a sure sign."

A little of Jonas Creyshaw's pluck and common sense came back to him at this unpleasant announcement.

"Not on his say-so," he stoutly averred. "I ain't a-goin' ter do the beck nor the bid of enny onmannerly harnt ez hev tuk up the notion ter riz up over the bluff inter Old Daddy's Window, an' sot hisself ter motionin' ter me."

He rose hastily, knocked the ashes out of his pipe, and followed his wife into the house. There he paused abruptly.

The room was lighted by the fitful flicker of the fire, for the nights were still chilly, and an old man, almost decrepit, sat dozing in his chair by the hearth.

"Mirandy," said Jonas Creyshaw in a whisper, "'pears like ter me ez father hed better not be let ter know 'bout'n that thar harnt. It mought skeer him so ez he couldn't live another minit. He hev aged some lately—an' he air weakly."

This was "Old Daddy."

Before he had reached his thirtieth year, he was thus known, far and wide.

"He air the man ez hev got a son," the mountaineers used to say in grinning explanation. "Ter hear him brag 'bout'n that thar boy o' his'n, ye'd think he war the only man in Tennessee ez ever hed a son."

Throughout all these years the name given in jocose banter had clung to him, and now, hallowed by ancient usage, it was accorded to him seriously, and had all the sonorous effect of a title.

So they said nothing to Old Daddy, but presently, when he had hobbled off to bed in the adjoining shed-room, they fell to discussing their terror of the apparition, and thus it chanced that the two boys, Tad and Si, first made, as it were, the ghost's acquaintance.

Tad, a stalwart fellow of seventeen, sat listening spellbound before the glowing embers. Si, a wiry, active, tow-headed boy of twelve, perched with dangling legs on a chest, and looked now at the group by the fire, and now through the open door at the brilliant moonlight.

"Waal, sir," he muttered, "I'll hev ter gin up the notion o' gittin' that comical young owel, what I hev done set my heart onto. 'Kase ef I war ter fool round Old Daddy's Window, now, whilst I war a-cotchin' o' the owel, the ghost mought—cotch—Me!"

A sorry ghost, to be sure, that has nothing better to do than to "cotch" him! But perhaps Si Creyshaw is not the only one of us who has an inflated idea of his own importance.

He was greatly awed, and he found many suggestions of supernatural presence about the familiar room. As the fire alternately flared and faded, the warping-bars looked as if they were dancing a clumsy measure. The handle of a portly jug resembled an arm stuck akimbo, and its cork, tilted askew, was like a hat set on one side; Si fancied there was a most unpleasant grimace below that hat. The churn-dasher, left upon a shelf to dry, was sardonically staring him out of countenance with its half-dozen eyes. The strings of red pepper-pods and gourds and herbs, swinging from the rafters, rustled faintly; it sounded to Si like a moan.

He wished his father and mother would talk about some wholesome subject, like Spot's new calf, for instance, instead of whispering about the mystery of Old Daddy's Window.

He wished Tad would not look, as he listened, so much like a ghost himself, with his starting eyes and pale, intent face. He even wished that the baby would wake up, and put some life into things with a good healthy, rousing bawl.

But the baby slept peacefully on, and after so long a time Si Creyshaw slept too.

With broad daylight his courage revived. He was no longer afraid to think of the ghost. In fact, he experienced a pleased importance in giving Old Daddy a minute account of the wonderful apparition, for he felt as if he had seen it.

"'Pears ter me toler'ble comical, gran'dad, ez they never tole ye a word 'bout'n it all," he said in conclusion. "Ye mought hev liked ter seen the harnt. Ef he war 'quainted with ye when he lived in this life, he mought hev stopped an' jowed sociable fur a spell!"

How brave this small boy was in the cheerful sunshine!

Old Daddy hardly seemed impressed with the pleasure he had missed in losing a sociable "jow" with a ghostly crony. He sat silent, blinking in the sunshine that fell through the gourd-vines which clambered about the porch where Si had placed his chair.

"'Twarn't much of a sizable sperit," Si declared; he seemed courageous enough now to measure the ghost like a tailor. "It warn't more'n four feet high, ez nigh ez dad could jedge. Toler'ble small fur a harnt!"

Still the old man made no reply. His wrinkled hands were clasped on his stick. His white head, shaded by his limp black hat, was bent down close to them. There was a slow, pondering expression on his face, but an excited gleam in his eye. Presently, he pointed backward toward a little unhewn log shanty that served as a barn, and rising with unwonted alacrity, he said to the boy,—

"Fotch me the old beastis!"

Silas Creyshaw stood amazed, for Old Daddy had not mounted a horse for twenty years.

"Studyin' 'bout'n the harnt so much hev teched him in the head," the small boy concluded. Then he made an excuse, for he knew his grandfather was too old and feeble to safely undertake a solitary jaunt on horse-back.

"I war tole not ter leave ye fur a minit, gran'dad. I war ter stay nigh ye an' mind yer bid."

"That's my bid!" said the old man sternly. "Fotch the beastis."

There was no one else about the place. Jonas Creyshaw had gone fishing shortly after daybreak. His wife had trudged off to her sister's house down in the cove, and had taken the baby with her. Tad was ploughing in the cornfield on the other side of the ravine. Si had no advice, and he had been brought up to think that Old Daddy's word was law.

When the old man, mounted at last, was jogging up the road, Tad chanced to come to the house for a bit of rope to mend the plough-gear. He saw, far up the leafy vista, the departing cavalier. He cast a look of amazed reproach upon Si. Then, speechless with astonishment, he silently pointed at the distant figure.

Si was a logician.

"I never lef' him," he said. "He lef' me."

"Ye oughter rej'ice in yer whole bones while ye hev got 'em," Tad returned, with withering sarcasm. "When dad kems home, some of 'em 'll git bruk, sure. Warn't ye tole not ter leave him fur nuthin', ye triflin' shoat!"

"He lef' me!" Si stoutly maintained.

Meantime, Old Daddy journeyed on.

Except for the wonderful mountain air, the settlement, three miles distant, had nothing about it to indicate its elevation. It was far from the cliffs, and there was no view. It was simply a little hollow of a clearing scooped out among the immense forests. When the mountaineers clear land, they do it effectually. Not a tree was left to embellish the yards of any of the four or five little log huts that constituted the hamlet, and the glare was intense.

As six or eight loungers sat smoking about the door of the store, there was nothing to intercept their astonished view of Old Daddy when he suddenly appeared out of the gloomy forest, blinking in the sun and bent half double with fatigue.

Even the rudest and coarsest of these mountaineers accord a praiseworthy deference to the aged among them. Old Daddy was held in reverential estimation at home, and was well accustomed to the respect shown him now, when, for the first time in many years, he had chosen to jog abroad. They helped him to dismount, and carried him bodily into the store. After he had tilted his chair back against the rude counter, he looked around with an important face upon the attentive group.

"My son," shrilly piped out Old Daddy,—"my son air the strongest man ever seen, sence Samson!"

"I hev always hearn that sayin', Old Daddy," acquiesced an elderly codger, who, by reason of "rheumatics," made no pretension to muscle.

A gigantic young blacksmith looked down at his corded hammer-arm, but said nothing.

A fly—several flies—buzzed about the sorghum barrel.

"My son," shrilly piped out Old Daddy,—"my son air the bes' shot on this hyar mounting."

"That's a true word, Old Daddy," assented the schoolmaster, who had ceased to be a Nimrod since devoting himself to teaching the young idea how to shoot.

The hunters smoked in solemn silence.

The shadow of a cloud drifted along the bare sandy stretch of the clearing.

"My son," shrilly piped out Old Daddy,—"my son hev got the peartest boys in Tennessee."

"I'll gin ye that up, Old Daddy," cheerfully agreed the miller, whose family consisted of two small "daughters."

The fathers of other "peart boys" cleared their throats uneasily, but finally subsided without offering contradiction.

A jay-bird alighted on a blackberry bush outside, fluttered all his blue and white feathers, screamed harshly, bobbed his crested head, and was off on his gay wings.

"My son," shrilly piped out Old Daddy,—"my son hev been gifted with the sight o' what no other man on this mounting hev ever viewed."

The group sat amazed, expectant. But the old man preserved a stately silence. Only when the storekeeper eagerly insisted, "What hev Jonas seen? what war he gin ter view?" did Old Daddy bring the fore legs of the chair down with a thump, lean forward, and mysteriously pipe out like a superannuated cricket,—

"My son,—my son hev seen a harnt, what riz up over the bluff a-purpose!"

"Whar 'bouts?" "When?" "Waal, sir!" arose in varied clamors.

So the proud old man told the story he had journeyed three laborious miles to spread. It had no terrors for him, so completely was fear swallowed up in admiration of his wonderful son, who had added to his other perfections the gift of seeing ghosts.

The men discussed it eagerly. There were some jokes cracked—as it was still broad noonday—and at one of these Old Daddy took great offense, more perhaps because the disrespect was offered to his son rather than to himself.

"Jes' gin Jonas the word from me," said the young blacksmith, meaning no harm and laughing good-naturedly, "ez I kin tell him percisely what makes him see harnts; it air drinkin' so much o' this onhealthy whiskey, what hain't got no tax paid onto it. I looks ter see him jes' a-staggerin' the nex' time I comes up with him."

Old Daddy rose with affronted dignity.

"My son," he declared vehemently,—"my son ain't gin over ter drinkin' whiskey, tax or no tax. An' he ain't got no call ter stagger—like some folks!"

And despite all apology and protest, he left the house in a huff.

His old bones ached with the unwonted exercise, and were rudely enough jarred by the rough roads and the awful gaits of his ancient steed. The sun was hot, and so was his heart, and when he reached home, infinitely fatigued and querulous, he gave his son a sorry account of his reception at the store. As he concluded, saying that five of the men had sent word that they would be at Jonas Creyshaw's house at moon-rise "ter holp him see the harnt," his son's brow darkened, and he strode heavily out of the room.

He usually exhibited in a high degree the hospitality characteristic of these mountaineers, but now it had given way to a still stronger instinct.

"Si," he said, coming suddenly upon the boy, "put out right now fur Bently's store at the settlemint, an' tell them sneaks ez hang round thar ter sarch round thar own houses fur harnts, ef they hanker ter see enny harnts. Ef they hev got the insurance ter kem hyar, they'll see wusser sights 'n enny harnts. Tell 'em I ain't a-goin' ter 'low no man ter cross my doorstep ez don't show Old Daddy the right medjure o' respec'. They'd better keep out'n my way ginerally."

So with this bellicose message Si set out. But an unlucky idea occurred to him as he went plodding along the sandy road.

"Whilst I'm a-goin' on this hyar harnt's yerrand"——The logical Si brought up with a shiver.

"I went ter say—whilst I'm a-goin' on this hyar yerrand fur the harnt"——This was as bad.

"Whilst," he qualified once more, "I'm a-goin' on this hyar yerrand 'bout'n the harnt, I mought ez well skeet off in them deep woods a piece ter see ef enny wild cherries air ripe on that tree by the spring. I'll hev plenty o' time."

But even Si could not persuade himself that the cherries were ripe, and he stood for a moment under the tree, staring disconsolately at the distant blue ridges shimmering through the heated air. The sunlight was motionless, languid; it seemed asleep. The drowsy drone of insects filled the forest. As Si threw himself down to rest on the rocky brink of the mountain, a grasshopper sprang away suddenly, high into the air, with an agility that suggested to him the chorus of a song, which he began to sing in a loud and self-sufficient voice:—

"The grasshopper said—'Now, don't ye see

Thar's mighty few dancers sech ez me—

Sech ez me!—Sech ez Me!'"

This reminded Si of his own capabilities as a dancer. He rose and began to caper nimbly, executing a series of steps that were singularly swift, spry, and unexpected,—a good deal on the grasshopper's method. His tattered black hat bobbed up and down on his tow head; his brown jeans trousers, so loose on his lean legs, flapped about hilariously; his bare heels flew out right and left; he snapped his fingers to mark the time; now and then he stuck his arms akimbo, and cut what he called the "widgeon-ping." But his freckled face was as grave as ever, and all the time that he danced he sang:—

"In the middle o' the night the rain kem down,

An' gin the corn a fraish start out'n the ground,

An' I thought nex' day ez I stood in the door,

That sassy bug mus' be drownded sure!

But thar war Goggle-eyes, peart an' gay,

Twangin' an' a-tunin' up—'Now, dance away!

Ye may sarch night an' day ez a constancy

An' ye won't find a fiddler sech ez me!

Sech ez me!—Sech ez Me!'"

As he sank back exhausted upon the ground, a new aspect of the scene caught his attention.

Those blue mountains were purpling—there was an ever-deepening flush in the west. It was close upon sunset, and while he had wasted the time, the five men to whom his father had sent that stern message forbidding them to come to his house were perhaps on their way thither, with every expectation of a cordial welcome. There might be a row—even a fight—and all because he had loitered.

How he tore out of the brambly woods! How he pounded along the sandy road! But when he reached the settlement close upon nightfall, the storekeeper's wife told him that the men had gone long ago.

"They war powerful special ter git off early," she added, "'kase they wanted ter be thar 'fore Old Daddy drapped off ter sleep. Some o' them foolish, slack-jawed boys ter the store ter-day riled the old man's feelin's, an' they 'lowed ter patch up the peace with him, an' let him an' Jonas know ez they never meant no harm."

This suggestion buoyed up the boy's heart to some degree as he toiled along the "short cut" homeward through the heavy shades of the gloomy woods and the mystic effects of the red rising moon. But he was not altogether without anxiety until, as he drew within sight of the log cabin on the slope of the ravine, he heard Old Daddy piping pacifically to the guests about "my son," and Jonas Creyshaw's jolly laughter.

The moon was golden now; Si could see its brilliant shafts of light strike aslant upon the smooth surface of the cliff that formed the opposite side of Old Daddy's Window. He stopped short in the deep shadow of the more rugged crag. The vines and bushes that draped its many jagged ledges dripped with dew. The boughs of an old oak, which grew close by, swayed gently in the breeze. Hidden by its huge hole, Si cast an apprehensive glance toward the house where his elders sat.

Certainly no one was thinking of him now.

"This air my chance fur that young owel—ef ever," he said to himself.

The owl's nest was in the hollow of the tree. The trunk was far too bulky to admit of climbing, and the lowest branches were well out of the boy's reach. Some thirty feet from the ground, however, one of the boughs touched the crag. By clambering up its rugged, irregular ledges, making a zigzag across its whole breadth to the right and then a similar zigzag to the left, Si might gain a position which would enable him to clutch this bough of the tree. Thence he could scramble along to the owl's stronghold.

He hesitated. He knew his elders would disapprove of so reckless an undertaking as climbing about Old Daddy's Window, for in venturing toward its outer verge, a false step, a crumbling ledge, the snapping of a vine, would fling him down the sheer precipice into the depths below.

His hankering for a pet owl had nevertheless brought him here more than once. It was only yesterday evening—before he had heard of the ghost's appearance, however—that he had made his last futile attempt.

He looked up doubtfully. "I ain't ez strong ez—ez some folks," he admitted.

"But then, come ter think of it," he argued astutely, "I don't weigh nuthin' sca'cely, an' thar ain't much of me ter hev ter haul up thar."

He flung off his hat, he laid his wiry hands upon the wild grape-vines, he felt with his bare feet for the familiar niches and jagged edges, and up he went, working steadily to the right, across the broad face of the cliff.

Its heavy shadow concealed him from view. Only one ledge, at the extreme verge of the crag, jutted out into the full moonbeams. But this, by reason of the intervening bushes and vines, could not be seen by those who sat in the cabin porch on the slope of the ravine, and he was glad to have light just here, for it was the most perilous point of his enterprise. By deft scrambling, however, he succeeded in getting on the moonlit ledge.

"I clumb like a painter!" he declared triumphantly.

He rested there for a moment before attempting to reach the vines high up on the left hand, which he must grasp in order to draw himself up into the shadowy niche in the rock, and begin his zigzag course back again across the face of the cliff to the projecting bough of the tree.

But suddenly, as he still stood motionless on the ledge in the full radiance of the moon, the clamor of frightened voices sounded at the house. Until now he had forgotten all about the ghost. He turned, horror-stricken.

There was the frightful thing, plainly defined against the smooth surface of the opposite cliff—some thirty feet distant—that formed the other side of Old Daddy's Window.

And certainly there are mighty few dancers such as that ghost! It lunged actively toward the precipice. It suddenly dashed wildly back—gyrating continually with singularly nimble feet, flinging wiry arms aloft and maintaining a sinister silence, while the frightened clamor at the house grew ever louder and more shrill.

Several minutes elapsed before Si recognized something peculiarly familiar in the ghost's wiry nimbleness—before he realized that the shadow of the cliff on which he stood reached across the ravine to the base of the opposite cliff, and that the figure which had caused so much alarm was only his own shadow cast upon its perpendicular surface.

He stopped short in those antics which had been induced by mortal terror; of course, his shadow, too, was still instantly. It stood upon the brink of the precipice which seems the sill of Old Daddy's Window, and showed distinctly on the smooth face of the cliff opposite to him.

He understood, after a moment's reflection, how it was that as he had climbed up on the ledge in the full moonlight his shadow had seemed to rise gradually from the vague depths below the insurmountable precipice.

He sprang nimbly upward to seize the vines that shielded him from the observation of the ghost-seers on the cabin porch, and as he caught them and swung himself suddenly from the moonlit ledge into the gloomy shade, he noticed that his shadow seemed to fling its arms wildly above its head, and disappeared upward.

"That air jes' what dad seen las' night when I war down hyar afore, a-figurin' ter ketch that thar leetle owel," he said to himself when he had reached the tree and sat in a crotch, panting and excited.

After a moment, regardless of the coveted owl, he swung down from branch to branch, dropped easily from the lowest upon the ground, picked up his hat, and prepared to skulk along the "short cut," strike the road, and come home by that route as if he had just returned from the settlement.

"'Kase," he argued sagely, "ef them skeered-ter-death grown folks war ter find out ez I war the harnt—I mean ez the harnt war me—ennyhow," he concluded desperately, "I'd ketch it—sure!"

So impressed was he with this idea that he discreetly held his tongue.

And from that day to this, Jonas Creyshaw and his friends have been unable to solve the mystery of Old Daddy's Window.

There was the grim Big Injun Mountain to the right, with its bare, beetling sandstone crags. There was the long line of cherty hills to the left, covered by a dark growth of stunted pines. Between lay that melancholy stretch of sterility known as Poor Valley,—the poorest of the several valleys in Tennessee thus piteously denominated, because of the sorry contrast which they present to the rich coves and fertile vales so usual among the mountains of the State.

How poor the soil was, Ike Hooden might bitterly testify; for ever since he could hold a plough he had, year after year, followed the old "bull-tongue" through the furrows of the sandy fields which lay around the log cabin at the base of the mountain. In the intervals of "crappin'" he worked at the forge with his stepfather, for close at hand, in the shadow of a great jutting cliff, lurked a dark little shanty of unhewn logs that was a blacksmith's shop.

When he first began this labor, he was, perhaps, the youngest striker that ever wielded a sledge. Now, at eighteen, he had become expert at the trade, and his muscles were admirably developed. He was tall and robust, and he had never an ache nor an ill, except in his aching heart. But his heart was sore, for in the shop he found oaths and harsh treatment, and even at home these pursued him; while outside, desolation was set like a seal on Poor Valley.

One drear autumnal afternoon, when the sky was dull, a dense white mist overspread the valley. As Ike plodded up the steep mountain side, the vapor followed him, creeping silently along the deep ravines and chasms, till at length it overtook and enveloped him. Then only a few feet of the familiar path remained visible.

Suddenly he stopped short and stared. A dim, distorted something was peering at him from over the top of a big boulder. It was moving—it nodded at him. Then he indistinctly recognized it as a tall, conical hat. There seemed a sort of featureless face below it.

A thrill of fear crept through him. His hands grew cold and shook in his pockets. He leaned forward, gazing intently into the thick fog.

An odd distortion crossed the vague, featureless face—like a leer, perhaps. Once more the tall, conical hat nodded fantastically.

"Ef ye do that agin," cried Ike, in sudden anger, all his pluck coming back with a rush, "I'll gin ye a lick ez will weld yer head an' the boulder together!"

He lifted his clenched fist and shook it.

"Haw! haw! haw!" laughed the man in the mist.

Ike cooled off abruptly. He had been kicked and cuffed half his life, but he had never been laughed at. Ridicule tamed him. He was ashamed, and he remembered that he had been afraid, for he had thought the man was some "roamin' harnt."

"I dunno," said Ike sulkily, "ez ye hev got enny call ter pounce so suddint out'n the fog, an' go ter noddin' that cur'ous way ter folks ez can't half see ye."

"I never knowed afore," said the man in the mist, with mock apology in his tone and in the fantastic gyrations of his nodding hat, "ez it air you-uns ez owns this mounting." He looked derisively at Ike from head to foot. "Ye air the biggest man in Tennessee, ain't ye?"

"Naw!" said Ike shortly, feeling painfully awkward, as an overgrown boy is apt to do.

"Waal, from yer height, I mought hev thunk ye war that big Injun that the old folks tells about," and the stranger broke suddenly into a hoarse, quavering chant:—

"'A red man lived in Tennessee,

Mighty big Injun, sure!

He growed ez high ez the tallest tree,

An' he sez, sez he, "Big Injun, me!"

Mighty big Injun, sure!'"

"Waal, waal," in a pensive voice, "so ye ain't him? I'm powerful glad ye tole me that, sonny, 'kase I mought hev got skeered hyar in the woods by myself with that big Injun."

He laughed boisterously, and began to sing again:—

"'Settlers blazed out a road, ye see,

Mighty big Injun, sure!

He combed thar hair with a knife. Sez he,

"It's combed fur good! Big Injun, me!"

Mighty big Injun, sure!'"

He broke out laughing afresh, and Ike, abashed and indignant, was about to pass on, when the man gayly balanced himself on one foot, as if he were about to dance a grotesque jig, and held out at arm's length a big silver coin.

It was a dollar. That meant a great deal to Ike, for he earned no money he could call his own.

"Free an' enlightened citizen o' these Nunited States," the man addressed him with mock solemnity, "I brung this dollar hyar fur you-uns."

"What air ye layin' off fur me ter do?" asked Ike.

The man grew abruptly grave. "Jes' stable this hyar critter fur a night an' day."

For the first time Ike became aware of a horse's flank, dimly seen on the other side of the boulder.

"Ter-morrer night ride him up ter my house on the mounting. Ye hev hearn tell o' me, hain't ye, Jedge? My name's Grig Beemy. Don't kem till night, 'kase I won't be thar till then. I hev got ter stop yander—yander"—he looked about uncertainly, "yander ter the sawmill till then, 'kase I promised ter holp work thar some. I'll gin ye the dollar now," he added liberally, as an extra inducement.

"I'll be powerful glad ter do that thar job fur a dollar," said Ike, thinking, with a glow of self-gratulation, of the corn which he had raised in his scanty leisure on his own little patch of ground, and which he might use to feed the animal.

"But hold yer jaw 'bout'n it, boy. Yer stepdad wouldn't let the beastis stay thar a minute ef he knowed it, 'kase—waal—'kase me an' him hev hed words. Slip the beastis in on the sly. Pearce Tallam don't feed an' tend ter his critters nohow. I hev hearn ez his boys do that job, so he ain't like ter find it out. On the sly—that's the trade."

Ike hesitated.

Once more the man teetered on one foot, and held out the coin temptingly. But Ike's better instincts came to his aid.

"That barn b'longs ter Pearce Tallam. I puts nuthin' thar 'thout his knowin' it. I ain't a fox, nur a mink, nur su'thin wild, ter go skulkin' 'bout on the sly."

Then he pressed hastily on out of temptation's way.

"Haw! haw! haw!" laughed the man in the mist.

There was no mirth in the tones now; his laugh was a bitter gibe. As it followed Ike, it reminded him that the man had not yet moved from beside the boulder, or he would have heard the thud of the horse's hoofs.

He turned and glanced back. The opaque white mist was dense about him, and he could see nothing. As he stood still, he heard a muttered oath, and after a time the man cleared his throat in a rasping fashion, as if the oath had stuck in it.

Ike understood at last. The man was waiting for somebody. And this was strange, here in the thick fog on the bleak mountainside. But Ike said to himself that it was no concern of his, and plodded steadily on, till he reached a dark little log house, above which towered a flaring yellow hickory tree.

Within, ranged on benches, were homespun-clad mountain children. A high-shouldered, elderly man sat at a table near the deep fireplace, where a huge backlog was smouldering. Through the cobwebbed window-panes the mists looked in.

Ike did not speak as he stood on the threshold, but his greedy glance at the scholars' books enlightened the pedagogue. "Do you want to come to school?" he asked.

Then the boy's long-cherished grievance burst forth. "They hev tole me ez how it air agin the law, bein' ez I lives out'n the deestric'."

The teacher elevated his grizzled eyebrows, and Ike said, "I kem hyar ter ax ye ef that be a true word. I 'lowed ez mebbe my dad tole me that word jes' ter hender me, an' keep me at the forge. It riles me powerful ter hev ter be an ignorunt all my days."

To a stranger, this reflection on his "dad" seemed unbecoming. The teacher's sympathy ebbed. He looked severely at the boy's pale, anxious face, as he coldly said that he could teach no pupils who resided outside his school district, except out of regular school hours, and with a charge for tuition.

Ike Hooden had no money. He nodded suddenly in farewell, the door closed, and when the schoolmaster, in returning compassion, opened it after him, and peered out into the impenetrable mist, the boy was nowhere to be seen. He had taken his despair by the hand, and together they went down, down into the depths of Poor Valley.

He stood so sorely in need of a little kindness that he felt grateful for the friendly aspect of his stepbrother, whom he met just before he reached the shop.

"'Pears like ye air toler'ble late a-gittin' home, Ike," said Jube. "I done ye the favior ter feed the critters. I 'lowed ez ye would do ez much fur me some day. I'll feed 'em agin in the mornin', ef ye'll forge me three lenks ter my trace-chain ter-night, arter dad hev gone home."

Now this broad-faced, sandy-haired, undersized boy, who was two or three years younger than Ike, and not strong enough for work at the anvil, was a great tactician. It was his habit, in doing a favor, rigorously to exact a set-off, and that night when the blacksmith had left the shop, Jube slouched in.

The flare of the forge-fire illumined with a fitful flicker the dark interior, showing the rod across the corner with its jingling weight of horseshoes, a ploughshare on the ground, the barrel of water, the low window, and casting upon the wall a grotesque shadow of Jube's dodging figure as he began to ply the bellows.

Presently he left off, the panting roar ceased, the hot iron was laid on the anvil, and his dodging image on the wall was replaced by an immense shadow of Ike's big right arm as he raised it. The blows fell fast; the sparks showered about. All the air was ajar with the resonant clamor of the hammer, and the anvil sang and sang, shrill and clear. When the iron was hammered cold, Jube broke the momentary silence.

"I hev got," he droned, as if he were reciting something made familiar by repetition, "two roosters, 'leven hens, an' three pullets."

There was a long pause, and then he chanted, "One o' the roosters air a Dominicky."

He walked over to the anvil and struck it with a small bit of metal which he held concealed in his hand.

"I hev got two shoats, a bag o' dried peaches, two geese, an' I'm tradin' with mam fur a gayn-der."

He quietly slipped the small bit of shining metal in his pocket.

"I hev got," he droned, waxing very impressive, "a red heifer."

Ike paused meditatively, his hammer in his hand. A new hope was dawning within him. He knew what was meant by Jube, who often recited the list of his possessions, seeking to rouse enough envy to induce Ike to exchange for the "lay out" his interest in a certain gray mare.

Now the mare really belonged to Ike, having come to him from his paternal grandfather. This was all of value that the old man had left; for the deserted log hut, rotting on another bleak waste farther down in Poor Valley, was worth only a sigh for the home that it once was,—worth, too, perhaps, the thanks of those it sheltered now, the rat and the owl.

The mare had worked for Pearce Tallam in the plough, under the saddle, and in the wagon all the years since. But one day, when the boy fell into a rage,—for he, too, had a difficult temper,—and declared that he would sell her and go forth from Poor Valley never to return, he was met by the question, "Hain't the mare lived off'n my fields, an' hain't I gin ye yer grub, an' clothes, an' the roof that kivers ye?"

Thus Pearce Tallam had disputed his right to sell the mare. But it had more than once occurred to him that the blacksmith would not object to Jube's buying her.

Hitherto Ike had not coveted Jube's variegated possessions. But now he wanted money for schooling. It was true he could hardly turn these into cash, for in this region farm produce of every description is received at the country stores in exchange for powder, salt, and similar necessities, and thus there is little need for money, and very little is in circulation.

Still, Ike reflected that he might now and then get a small sum at the store, or perhaps the schoolmaster might barter "l'arnin'" for the heifer or the shoats.

His hesitation was not lost upon Jube, who offered a culminating inducement to clinch the trade. He suddenly stood erect, teetered fantastically on one foot, as if about to begin to dance, and held out a glittering silver dollar.

The hammer fell from Ike's hands upon the anvil. "'Twar ye ez Grig Beemy war a-waitin' fur thar on the mounting in the mist!" he cried out, recognizing the man's odd gesture, which Jube had unconsciously imitated.

Doubtless the dollar was offered to Jube afterward, exactly as it had been offered to him. And Jube had taken it. The imitative monkey thrust it hastily into his pocket, and came down from his fantastic toe, and stood soberly enough on his two feet.

"Grig Beemy gin ye that thar dollar," said Ike.

Jube sullenly denied it. "He never, now!"

"His critter hev got no call ter be in dad's barn."

"His critter ain't hyar," protested Jube. "This dollar war gin me in trade ter the settlemint."

Ike remembered the queer gesture. How could Jube have repeated it if he had not seen it? He broke into a sarcastic laugh.

"That's how kem ye war so powerful 'commodatin' ez ter feed the critters. Ye 'lowed ez I wouldn't see the strange beastis, an' then tell dad. Foolin' me war a part o' yer trade, I reckon."

Jube made no reply.

"Ef ye war ez big ez me, or bigger, I'd thrash ye out'n yer boots fur this trick. Ye don't want no lenks ter yer chain. Ye jes' want ter be sure o' keepin' me out'n the barn. Waal—thar air yer lenks."

He caught up the tongs and held the links in the fire with one hand while he worked the bellows with the other. Then he laid them red-hot upon the anvil. His rapid blows crushed them to a shapeless mass. "And now—thar they ain't."

Jube did not linger long. He was in terror lest Ike should tell his father. But Ike did not think this was his duty. In fact, neither boy imagined that the affair involved anything more serious than stabling a horse without the knowledge of the owner of the shelter.

When Ike was alone a little later, an unaccustomed sound caused him to glance toward the window.

Something outside was passing it. His position was such that he could not see the object itself, but upon the perpendicular gray wall of the crag close at hand, and distinctly defined in the yellow flare that flickered out through the window from the fire of the forge, the gigantic shadow of a horse's head glided by.

He understood in an instant that Jube had slipped the animal out of the barn, and was hiding him in the misty woods, expecting that Ike would acquaint his father with the facts. He had so managed that these facts would seem lies, if Pearce Tallam should examine the premises and find no horse there.

All the next day the white mist clung shroud-like to Poor Valley. The shadows of evening were sifting through it, when Ike's mother went to the shop, much perturbed because the cow had not come, and she could not find Jube to send after her.

"Ike kin go, I reckon," said the blacksmith.

So Ike mounted his mare and set out through the thick white vapor. He had divined the cause of Jube's absence, and experienced no surprise when on the summit of the mountain he overtook him, riding the strange horse, on his way to Beemy's house.

"I s'pose that critter air yourn, an' ye mus' hev bought him fur a pound o' dried peaches, or sech, up thar ter the settlemint," sneered Ike.

Jube was about to reply, but he glanced back into the dense mist with a changing expression.

"Hesh up!" he said softly. "What's that?"

It was the regular beat of horses' hoofs, coming at a fair pace along the road on the summit of the mountain. The riders were talking excitedly.

"I tell ye, ef I could git a glimpse o' the man ez stole that thar horse, it would go powerful hard with me not to let daylight through him. I brung this hyar shootin'-iron along o' purpose. Waal, waal, though, seein' ez ye air the sheriff, I'll hev ter leave it be ez you-uns say. I wouldn't know the man from Adam; but ye can't miss the critter,—big chestnut, with a star in his forehead, an'"—

Something strange had happened. At the sound of the voice the horse pricked up his ears, turned short round in the road, and neighed joyfully.

The boys looked at each other with white faces. They understood at last. Jube was mounted on a stolen horse within a hundred yards of the pursuing owner and the officers of the law. Could explanations—words, mere words—clear him in the teeth of this fact?

"Drap out'n the saddle, turn the critter loose in the road, an' take ter the woods," urged Ike.

"They'll sarch an' ketch me," quavered Jube.

He was frantic at the idea of being captured on the horse's back, but if it should come to a race, he preferred trusting to the chestnut's four legs rather than to his own two.

Ike hesitated. Jube had brought the difficulty all on himself, and surely it was not incumbent on Ike to share the danger. But he was swayed by a sudden uncontrollable impulse.

"Drap off'n the critter, turn him loose, an' I'll lope down the road a piece, an' they'll foller me, in the mist."

He might have done a wiser thing. But it was a tough problem at best, and he had only a moment in which to decide.

In that swift, confused second he saw Jube slide from the saddle and disappear in the mist as if he had been caught up in the clouds. He heard the horse's hoofs striking against the stones as he trotted off, whinnying, to meet his master. There was a momentary clamor among the men, and then with whip and spur they pressed on to capture the supposed malefactor.

All at once it occurred to Ike, as he galloped down the road, that when they overtook him, they would think that he was the thief, and that he had been leading the horse. He had been so strong in his own innocence that the possibility that they might suspect him had not before entered his mind.

He had intended only to divert the pursuit from Jube, who, although free from any great wrong-doing, was exposed to the most serious misconstruction. The knowledge of the pursuers' revolvers had made this a hard thing to do, but otherwise he had not thought of himself, nor of what he should say when overtaken.

They would question him; he must answer. Would they believe his story? Could he support it? Grig Beemy of course would deny it. And Jube—had he not known how Jube could lie? Would he not fear that the truth might somehow involve him with the horse-thief?

Ike, with despair in his heart, urged his mare to her utmost speed, knowing now the danger he was in as a suspected horse-thief. Suddenly, from among his pursuers, a tiny jet of flame flared out into the dense gray atmosphere, something whizzed through the branches of the trees above his head, and a sharp report jarred the mists.

Perhaps the officer fired into the air, merely to intimidate the supposed criminal and induce him to surrender. But now the boy could not stop. He had lost control of the mare. Frightened beyond measure by the report of the pistol, she was in full run.

On she dashed, down sharp declivities, up steep ascents, and then away and away, with a great burst of speed, along a level sandy stretch.

The black night was falling like a pall upon the white, shrouded day. Ike knew less where he was than the mare did; he was trusting to her instinct to carry him to her stable. More than once the low branches of a tree struck him, almost tearing him from the saddle, but he clung frantically to the mane of the frightened animal, and on and on she swept, with the horsemen thundering behind.

He could hear nothing but their heavy, continuous tramp. He could see nothing, until suddenly a dim, pure light was shining in front of him, on his own level, it seemed. He stared at it with starting eyeballs. It cleft the vapors,—they were falling away on either side,—and they reflected it with an illusive, pearly shimmer.

In another moment he knew that he was nearing the abrupt precipice, for that was the moon, riding like a silver boat upon a sea of mist, with a glittering wake behind it, beyond the sharply serrated summit line of the eastern hills.

He could no longer trust to the mare's instinct. He trusted to appearances instead. He sawed away with all his might on the bit, striving to wheel her around in the road.

She resisted, stumbled, then fell upon her knees among a wild confusion of rotting logs and stones that rolled beneath her, as, snorting and angry, she struggled again to her feet. Once more Ike pulled her to the left.

There was a great displacement of earth, a frantic scramble, and together they went over the cliff.

The descent was not absolutely sheer. At the distance of twelve or fourteen feet below, a great bulging shelf of rock projected. They fell upon this. The boy had instantly loosed his hold of the reins, and slipped away from the prostrate animal. The mare, quieted only for a moment by the shock, sprang to her feet, the stones slipped beneath her, and she went headlong over the precipice into the dreary depths of Poor Valley.

The pursuers heard the heavy thud when she struck the ground far below. They paused at the verge of the crag, and talked in eager, excited tones. They did not see the boy, as he sat cowering close to the cliff on the ledge below.

Ike listened in great trepidation to what they were saying; he experienced infinite surprise when presently one of them mentioned Grig Beemy's name.

So they knew who had stolen the horse! It was little consolation to Ike, with his mare lying dead at the foot of the cliff, to reflect that if he had had the courage to face the emergency, and rely upon his innocence, his story would only have confirmed their knowledge of the facts.

Although the master of the horse did not know the thief "from Adam," Beemy had been seen with the animal and recognized by others, who, accompanying the sheriff and the owner, had traced him for two days through many wily doublings in the mountain fastnesses.

They now concluded to press on to Beemy's house. Ike knew they would find him there waiting for Jube and the horse. Beemy had feared that he would be followed, and this was the reason that he had desired to rid himself of the animal for a day and night, until he could make sure and feel more secure.

As the horsemen swept round the curve, Ike remembered how close was the road to the cliff. If he had only given the mare her head, she would have carried him safely around it. But there she lay dead, way down in Poor Valley, and he had lost all he owned in the world.

Night had come, and in the dense darkness he did not dare to move. Only a step away was the edge of the precipice, over which the mare had slipped, and he could not tell how dangerous was the bluff he must climb to regain the summit. He felt he must lie here till dawn.

He was badly jarred by his fall. Time dragged by wearily, and his bruises pained him. He knew at length that all the world slept,—all but himself and some distant ravening wolf, whose fierce howl ever and anon set the mists to shivering in Poor Valley where he prowled. This blood-curdling sound and his bitter thoughts were but sorry company.

After a long time he fell asleep. Fortunately, he did not stir. When he regained consciousness and a sense of danger, he found still around him that dense white vapor, through which the pale, drear day was slowly dawning. Above his head was swinging in the mist a cluster of fox-grapes, with the rime upon them, and higher still he saw a quivering red leaf.

It was the leaf of a starveling tree, growing out of a cleft where there was so little earth that it seemed to draw its sustenance from the rock. It was a scraggy, stunted thing, but it was well for him that it had struck root there, for its branches brushed the solid, smooth face of the cliff, which he could not have surmounted but for them and the grape-vine that had fallen over from the summit and entangled itself among them.

As he climbed the tree, he felt it quake over the abysses, which the mists still veiled. He had a sense of elation and achievement when he gained the top, and it followed him home. There it suddenly deserted him.

He found Pearce Tallam in a frenzy of rage at the discovery, which he had made through Jube's confession, that a stolen horse had been stabled on his premises. Despite his tyranny and his fierce, rude temper, he was an honest man and of fair repute. Although he realized that neither boy knew that the animal had been stolen, he gave Jube a lesson which he remembered for many a long day, and Ike also came in for his share of this muscular tuition.

For in the midst of the criminations and recriminations, the violent blacksmith caught up a horseshoe and flung it across the shop, striking Ike with a force that almost stunned him. He was a man in strength, and it was hard for him not to return the blow; but he only walked out of the shop, declaring that he would stay for no more blows.

"Cl'ar out, then!" called out Pearce Tallam after him. "I don't keer ef ye goes fur good."

He met, at the door of the dwelling, a plaintive reproach from his mother. "'Count o' ye not tellin' on Jube, he mought hev been tuk up fur a horse-thief. I dunno what I'd hev done 'thout him," she added, "'long o' raisin' the young tur-r-keys, an' goslin's, an' deedies, an' sech; he hev been a mighty holp ter me. He air more of a son ter me than my own boy."

She did not mean this, but she had said it once half in jest, half in reproach, and then it became a formula of complaint whenever Ike displeased her.

Now he was sore and sensitive. "Take him fur yer son, then!" he cried. "I'm a-goin' out'n Pore Valley, ef I starves fur it. I shows my face hyar no more."

As he shouldered his gun and strode out, he noted the light of the forge-fire quivering on the mist, but he little thought it was the last fire that Pearce Tallam would ever kindle there.

He glanced back again before the dense vapor shut the house from view. His mother was standing in the door, with her baby in her arms, looking after him with a frightened, beseeching face. But his heart was hardened and he kept on,—kept on, with that deft, even tread of the mountaineer, who seems never to hurry, almost to loiter, but gets over the ground with surprising rapidity.

He left the mists and desolation of Poor Valley far behind, but not that frightened, beseeching face. He thought of it more often when he lay down under the shelter of a great rock to sleep than he did of the howl of the wolf which he had heard the night before, not far from here.

Late the next afternoon he came upon the outskirts of a village. He entered it doubtfully, for it seemed metropolitan to him, unaccustomed as he was to anything more imposing than the cross-roads store. But the first sound he heard reassured him. It was the clear, metallic resonance of an anvil, the clanking of a sledge, and the clinking of a hand-hammer.

Here, at the forge, he found work. It had been said in Poor Valley that he was already as good a blacksmith even as Pearce Tallam. He had great natural aptitude for the work, and considerable experience. But his wages only sufficed to pay for his food and lodging. Still, there was a prospect for more, and he was content.

In his leisure he made friends among those of his own age, who took him about the town and enjoyed his amazement. He examined everything wrought in metal with such eager interest, and was so outspoken about his ambition, that they dubbed him Tubal-cain.

He was struck dumb with amazement when, for the first time in his life, he saw a locomotive gliding along the rails, with a glaring headlight and a cloud of flying sparks. Once, when it was motionless on the track, they talked to the engineer, who explained "the workings of the critter," as Ike called it.

The boy understood so readily that the engineer said, after a time, "You're a likely feller, for such a derned ignoramus! Where have you been hid out, all this time?"

"Way down in Pore Valley," said Ike very humbly.

"He's concluded to be a great inventor," said one of his young friends, with a merry wink.

"He's a mighty artificer in iron," said the wit who had named him Tubal-cain.

The engineer looked gravely at Ike. "Why, boy," he admonished him, "the world has got a hundred years the start of you!"

"I kin ketch up," Ike declared sturdily.

"There's something in grit, I reckon," said the engineer. Then his wonderful locomotive glided away, leaving Ike staring after it in silent ecstasy, and his companions dying with laughter.

He started out to overtake the world at a night-school, where his mental quickness contrasted oddly with his slow, stolid demeanor. He worked hard at the forge all day; but everybody was kind.

Outside of Poor Valley life seemed joyous and hopeful; progress and activity were on every hand; and the time he spent here was the happiest he had ever known,—except for the recollection of that frightened, beseeching face which had looked out after him through the closing mists.

He wished he had turned back for a word. He wished his mother might know he was well and happy. He began to feel that he could go no further without making his peace with her. So one day he left his employer with the promise to return the following week, "ef the Lord spares me an' nuthin' happens," as the cautious rural formula has it, and set out for his home.

The mists had lifted from it, but the snow had fallen deep. Poor Valley lay white and drear—it seemed to him that he had never before known how drear—between the grim mountain with its great black crags, its chasms, its gaunt, naked trees, and the long line of flinty hills, whose stunted pines bent with the weight of the snow.

There was no smoke from the chimney of the blacksmith's shop. There were no footprints about the door. An atmosphere charged with calamity seemed to hang over the dwelling. Somehow he knew that a dreadful thing had happened even before he opened the door and saw his mother's mournful white face.

She sprang up at the sight of him with a wild, sobbing cry that was half grief, half joy. He had only a glimpse of the interior,—of Jube, looking anxious and unnaturally grave; of the listless children, grouped about the fire; of the big, burly blacksmith, with a strange, deep pallor upon his face, and as he shifted his position—why, how was that?

The boy's mother had thrust him out of the door, and closed it behind her. The jar brought down from the low eaves a few feathery flakes of snow, which fell upon her hair as she stood there with him.

"Don't say nuthin' 'bout'n it," she implored. "He can't abide ter hear it spoke of."

"What ails dad's hand?" he asked, bewildered.

"It's gone!" she sobbed. "He war over ter the sawmill the day ye lef'—somehow 'nuther the saw cotched it—the doctor tuk it off."

"His right hand!" cried Ike, appalled.

The blacksmith would never lift a hammer again. And there the forge stood, silent and smokeless.

What this portended, Ike realized as he sat with them around the fire. Their sterile fields in Poor Valley had only served to eke out their subsistence. This year the corn-crop had failed, and the wheat was hardly better. The winter had found them without special provision, but without special anxiety, for the anvil had always amply supplied their simple needs.

Now that this misfortune had befallen them, who could say what was before them unless Ike would remain and take his stepfather's place at the forge? Ike knew that this contingency must have occurred to them as well as to him. He divined it from the anxious, furtive glances which they one and all cast upon him from time to time,—even Pearce Tallam, whose turn it was now to feel that greatest anguish of calamity, helplessness.

But must he relinquish his hopes, his chance of an education, that plucky race for which he was entered to overtake the world that had a hundred years the start of him, and be forever a nameless, futureless clod in Poor Valley?

His mother had the son she had chosen. And surely he owed no duty to Pearce Tallam. The hand that was gone had been a hard hand to him.

He rose at length. He put on his leather apron. "Waal—I mought ez well g' long ter the shop, I reckon," he remarked calmly. "'Pears like thar's time yit fur a toler'ble spot o' work afore dark."

It was a hard-won victory. Even then he experienced a sort of satisfaction in knowing that Pearce Tallam must feel humiliated and of small account to be thus utterly dependent for his bread upon the boy whom he had so persistently maltreated. In his pale face Ike saw something of the bitterness he had endured, of his broken spirit, of his humbled pride.

The look smote upon the boy's heart. There was another inward struggle. Then he said, as if it were a result of deep cogitation,—

"Ye'll hev ter kem over ter the shop, dad, wunst in a while, ter advise 'bout what's doin'. 'Pears ter me like mos' folks would 'low ez a boy no older 'n me couldn't do reg'lar blacksmithin' 'thout some sperienced body along fur sense an' showin'."

The man visibly plucked up a little. Was he, indeed, so useless? "That's a fac', Ike," he said gently. "I reckon ye kin make out toler'ble—cornsiderin'. But I'll be along ter holp."

After this Ike realized that he had been working with something tougher than iron, harder than steel,—his own unsubdued nature. He traced an analogy from the forge; and he saw that those strong forces, the fires of conscience and the coercion of duty, had wrought the stubborn metal of his character to a kindly use.

Gradually the relinquishment of his wild, vague ambition began to seem less bitter to him; for it might be that these were the few things over which he should be faithful,—his own forge-fire and his own fiery heart. And so he labors to fulfill his trust.

The spring never comes to Poor Valley. The summer is a cloud of dust. The autumn shrouds itself in mist. And the winter is snow. But poverty of soil need not imply poverty of soul. And a noble manhood may nobly exist "'Way Down in Poor Valley."

"Ef the filly war bridle-wise"—

"The filly air bridle-wise."

A sullen pause ensued, and the two brothers looked angrily at each other.

The woods were still; the sunshine was faint and flickering; the low, guttural notes of a rain-crow broke suddenly on the silence.

Presently Thad, mechanically examining a bridle which he held in his hand, began again in an appealing tone: "'Pears like ter me ez the filly air toler'ble well bruk ter the saddle, an' she would holp me powerful ter git thar quicker ter tell dad 'bout'n that thar word ez war fotched up the mounting. They 'lowed ez 'twar jes' las' night ez them revenue men raided a still-house, somewhar down thar in the valley, an' busted the tubs, an' sp'iled the coppers, an' arrested all the moonshiners ez war thar. An' ef they war ter find out 'bout'n this hyar still-house over yander in the gorge, they'd raid it, too. An' thar be dad," he continued despairingly, "jes' sodden with whiskey an' ez drunk ez a fraish b'iled owel, an' he wouldn't hev the sense nor the showin' ter make them off'cers onderstand ez he never hed nothin' ter do with the moonshiners—'ceptin' ter go ter thar still-house, an' git drunk along o' them. An' I dunno whether the off'cers would set much store by that sayin' ennyhow, an' I want ter git dad away from thar afore they kem."

"I don't believe that thar word ez them men air a-raidin' round the mountings no more 'n that!" and Ben kicked away a pebble contemptuously.

Thad was in a quiver of anxiety. While Ben indulged his doubts, the paternal "B'iled Owel" might at any moment be arrested on a charge of aiding and abetting in illicit distilling.

"Ye never b'lieve nothin' till ye see it—ye sateful dunce!" he exclaimed excitedly.

Thus began a fraternal quarrel which neither forgot for years.

Ben turned scarlet. "Waal, then, jes' leave my filly in the barn whar she be now; ye kin travel on Shank's mare!"

Thad started off up the steep slope. "Ef ye ain't a-hankerin' fur me ter ride that thar filly, ez air ez bridle-wise ez ye be, jes' let's see ye kem on, an'—hender!"

"I hopes she'll fling ye, an' ye'll git yer neck bruk," Ben called out after him.

"I wish ennything 'ud happen, jes' so be I mought never lay eyes on ye agin," Thad declared.

As he glanced over his shoulder, he saw that his brother was not following, and when he reached the flimsy little barn, there was nothing to prevent him from carrying out his resolution.

Nevertheless, he hesitated as he stood with the door in his hand. A clay-bank filly came instantly to it, but with a sudden impulse he closed it abruptly, and set out on foot along a narrow, brambly path that wound down the mountain side.

He had descended almost to its base before the threatening appearance of the sky caught his attention. A dense black cloud had climbed up from over the opposite hills, and stretched from their jagged summits to the zenith. There it hung in mid-air, its sombre shadow falling across the valley, and reaching high up the craggy slope, where the boy's home was perched. The whole landscape wore that strange, still, expectant aspect which precedes the bursting of a storm.

Suddenly a vivid white flash quivered through the sky. The hills, suffused with its ghastly light, started up in bold relief against the black clouds; even the faint outlines of distant ranges that had disappeared with the strong sunlight reasserted themselves in a pale, illusive fashion, flickering like the unreal mountains of a dream about the vague horizon. A ball of fire had coursed through the air, striking with dazzling coruscations the top of a towering oak, and he heard, amidst the thunder and its clamorous echo, the sharp crash of riving timber.

All at once he had a sense of falling, a sudden pain shot through him, darkness descended, and he knew no more.

When he gradually regained consciousness, it seemed that a long time had elapsed since he was trudging down the mountain side. He could not imagine where he was now. He put out his hand in the intense darkness that enveloped him, and felt the damp mould beside him,—above—below.

For one horrible instant he recalled a sickening story of a man who was negligently buried alive. He had always believed that this was only a fireside fiction invented in the security of the chimney corner; but was it to have a strange confirmation in his own fate? He was pierced with pity for himself, as he heard the despair in his voice when he sent forth a wild, hoarse cry. What a cavernous echo it had!

Again and again, after his lips were closed, that voice of anguish rang out, and then was silent, then fitfully sounded once more on another key. He strove to rise, but the earth on his breast resisted. With a great effort he finally burst through it; he felt the clods tumbling about him; he sat upright; he rose to his full height; and still all was merged in the densest darkness, and, when he stretched up his arms as high as he could reach, he again felt the damp mould.

The truth had begun vaguely to enter his mind even before, in shifting his position, he caught sight of a rift in the deep gloom, some fifteen feet above his head. Then he realized that at the moment of the flash of lightning, unmindful of his footing, he had strayed aside from the path, stumbled, fallen, and, as it chanced, was received into one of those unsuspected apertures in the ground which are common in all cavernous countries, being sometimes the entrance to extensive caves, and which are here denominated "sink-holes."

These cavities were exceedingly frequent in the valley, on the boundary of which Thad lived, and his familiarity with them did away for the moment with all appreciation of the perplexity and difficulty of the situation. He laughed aloud triumphantly.

Instantly these underground chambers broke forth with wild, elfish voices that mimicked his merriment till it died on his lips. He preferred utter loneliness to the vague sense of companionship given by these weird echoes. Somehow the strangeness of all that had happened to him had stirred his imagination, and he could not rid himself of the idea that there were grimacing creatures here with him, whom he could not see, who would only speak when he spoke, and scoffingly iterate his tones.

He was faint, bruised, and exhausted. He had been badly stunned by his fall; but for the soft, shelving earth through which he had crashed, it might have been still worse. He could scarcely move as he began to investigate his precarious plight. Even if he could climb the perpendicular wall above his head, he could not thence gain the aperture, for, as his eyes became more accustomed to the darkness, he discovered that the shape of the roof was like the interior of a roughly defined dome, about the centre of which was this small opening.

"An' a human can't walk on a ceilin' like a fly," he said discontentedly.

"Can't!" cried an echo close at hand.

"Fly!" suggested a distant mocker.

Thad closed his mouth and sat down.

He had moved very cautiously, for he knew that these sink-holes are often the entrance of extensive caverns, and that there might be a deep abyss on any side. He could do nothing but wait and call out now and then, and hope that somebody might soon take the short cut through the woods, and, hearing his voice, come to his relief.

His courage gave way when he reflected that the river would rise with the heavy rain which he could hear steadily splashing through the sink-hole, and for a time all prudent men would go by the beaten road and the ford. No one would care to take the short cut and save three miles' travel at the risk of swimming his horse, for the river was particularly deep just here and spanned only by a footbridge, except, perhaps, some fugitive from justice, or the revenue officers on their hurried, reckless raids. This reminded him of the still-house and of "dad" there yet, imbibing whiskey, and sharing the danger of his chosen cronies, the moonshiners.

Ben, at home, would not have his anxiety roused till midnight, at least, by his brother's failure to return from the complicated feat of decoying the drunkard from the distillery. Thad trembled to think what might happen to himself in the interval. If the volume of water pouring down through the sink-hole should increase to any considerable extent, he would be drowned here like a rat. Was he to have his wish, and see his brother never again?

And poor Ben! How his own cruel, wicked parting words would scourge him throughout his life,—even when he should grow old!

Thad's eyes filled with tears of prescient pity for his brother's remorse.

"Ef ennything war ter happen hyar, sure enough, I wish he mought always know ez I don't keer nothin' now 'bout'n that thar sayin' o' his'n," he thought wistfully.

He still heard the persistent rain splashing outside. The hollow, unnatural murmur of a subterranean stream rose drearily. Once he sighed heavily, and all the cavernous voices echoed his grief.

When that terrible flash of lightning came, Ben was still on the slope of the mountain where his brother had left him. The next moment he heard the wild whirl of the gusts as they came surging up the valley. He saw the frantic commotion of the woods on distant spurs as the wind advanced, preceded by swirling columns of dust which carried myriads of leaves, twigs, and even great branches rent from the trees, as evidence of its force.

Ben turned, and ran like a deer up the steep ascent. "It'll blow that thar barn spang off'n the bluff, I'm thinkin'—an' the filly—Cobe—Cobe!" he cried out to her as he neared the shanty.

He stopped short, his eyes distended. The door was open. There was no hair nor hoof of the filly within. He could have no doubt that his brother had actually taken his property for this errand against his will.

"That thar boy air no better 'n a low-down horse-thief!" he declared bitterly.

The gusts struck the little barn. It careened this way and that, and finally the flimsy structure came down with a crash, one of the boards narrowly missing Ben's head as it fell. He had a hard time getting to the house in the teeth of the wind, but its violence only continued a few minutes, and when he was safe within doors he looked out of the window at the silent mists, beginning to steal about the coves and ravines, and at the rain as it fell in serried columns. Long after dark it still beat with unabated persistence on the roof of the log cabin, and splashed and dripped with a chilly, cheerless sound from the low eaves. Sometimes a drop fell down the wide chimney, and hissed upon the red-hot coals, for Ben had piled on the logs and made a famous fire. He could see that his mother now and then paused to listen in the midst of her preparations for supper. Once as she knelt on the hearth, and deftly inserted a knife between the edges of a baking corn-cake and the hoe, she looked up suddenly at Ben without turning the cake. "I hearn the beastis's huff!" she said.

Ben listened. The fire roared. The rain went moaning down the valley.

"Ye never hearn nothin'," he rejoined.

Nevertheless, she rose and opened the door. The cold air streamed in. The firelight showed the mists, pressing close in the porch, shivering, and seeming to jostle and nudge each other as they peered in, curiously, upon the warm home-scene, and the smoking supper, and the hilarious children, as if asking of one another how they would like to be human creatures, instead of a part of inanimate nature, or at best the elusive spirits of the mountains.

There was nothing to be seen without but the mists.

"Thad tuk the filly, ye say fur true?" she asked, recurring to the subject when supper was over.

Ben nodded. "I hopes ter conscience she'll break his neck," he declared cruelly.

His mother took instant alarm. She turned and looked at him with a face expressive of the keenest anxiety. "'Pears like to me ez the only reason Thad kin be so late a-gittin' back air jes' 'kase it air a toler'ble aggervatin' job a-fotchin' of dad home," she said, striving to reassure herself.

"That air a true word 'bout'n dad, ennyhow," Ben assented bitterly.

His old grandfather suddenly lifted up his voice.

"This night," said the graybeard from out the chimney corner,—"this night, forty years ago, my brother, Ephraim Grimes, fell dead on this cabin floor, an' no man sence kin mark the cause."

A pause ensued. The rain fell. The pallid, shuddering mists looked in at the window.

"Ye ain't a-thinkin'," cried the woman tremulously, "ez the night air one app'inted fur evil?"

The old man did not answer.

"This night," he croaked, leaning over the glowing fire, and kindling his long-stemmed cob-pipe by dexterously scooping up with its bowl a live coal,—"this night, twenty-six years ago, thar war eleven sheep o' mine—ez war teched in the head, or somehows disabled from good sense—an' they jumped off'n the bluff, one arter the other, an' fell haffen way down the mounting, an' bruk thar fool necks 'mongst the boulders. They war dead. Thar shearin's never kem ter much account nuther. 'Twar powerful cur'ous, fust an' last."

The woman made a gesture of indifference. "I ain't a-settin' of store by critters when humans is—is—whar they ain't hearn from."

But Ben was susceptible of a "critter" scare.

"I hope, now," he exclaimed, alarmed, "ez that thar triflin' no-'count Thad Grimes ain't a-goin' ter let my filly lame herself, nor nothin', a-travelin' with her this dark night, ez seems ter be a night fur things ter happen on ennyhow. Oh, shucks! shucks!" he continued impatiently, "I jes' feels like thar ain't no use o' my tryin' ter live along."

Three of the children who habitually slept in the shed-room had started off to go to bed. As they opened the connecting door, there suddenly resounded a wild commotion within. They shrieked with fright, and banged the door against a strong force which was beginning to push from the other side.

The old grandfather rose, pale and agitated, his pipe falling from his nerveless clasp.

"This night," he said, with white lips and mechanical utterance,—"this night"—

"Satan is in the shed-room!" shouted the three small boys, as they held fast to the door with a strength far beyond their age and weight. Nevertheless, they were hardly able to cope with the strength on the other side of the door, and it was alternately forced slightly ajar, and then closed with a resounding slam. Once, as the firelight flickered into the dark shed-room, the ignorant, superstitious mountaineers had a fleeting glimpse of an object there which convinced them: they beheld great gleaming, blazing eyes, a burnished hoof, and—yes—a flirting tail.

"I believe it is Satan himself!" cried Ben, with awe in his voice.

In the wild confusion and bewilderment, Ben was somehow vaguely aware that Satan had often been in the shed-room before,—in the antechamber of his own heart. Whenever this heart of his was full of unkindness, and hardened against his brother, although those better fraternal instincts which he kept repressed and dwarfed might repudiate this cruelty under the pretext that he did not really mean it, still the great principle of evil was there in the moral shed-room, clamoring for entrance at the inner doors. And this, we may safely say, may apply to wiser people than poor Ben.

In the midst of the general despair and fright, something suddenly whinnied. At the sound the three small boys fell in a limp, exhausted heap on the floor, and, as the door no longer offered resistance, the unknown visitor pranced in: it was the filly, snorting and tossing her mane, and once more whinnying shrilly for her supper.

In a moment Ben understood the whole phenomenon. Thad had left the barn door unfastened, and, when that terrible flash of lightning came and the wind arose, the frightened animal had instantly fled to the house for safety. She had doubtless pushed open the back door of the shed-room easily enough, but it had closed behind her, and she had remained there a supperless prisoner.

The small boys picked themselves up from among the filly's hoofs, with disconnected exclamations of "Wa-a-a-l, sir!" while Ben led the animal out, with a growing impression that he would try to "live along" for a while, at all events.

He had led Satan out of the moral shed-room, as well. The reappearance of the filly without Thad had raised a great anxiety about his brother's continued absence. All at once he began to feel as if those brutal wishes of his were prophetic,—as if they were endowed with a malignant power, and could actually pursue poor Thad to some violent end. He did not understand now how he could have framed the words.

When a fellow really likes his brother,—and most fellows do,—there is scant use or grace or common-sense in keeping up, from mere carelessness, or through an irritable habit, a continual bickering, for these germs of evil are possessed of a marvelous faculty for growth, and some day their gigantic deformities will confront you in deeds of which you once believed yourself incapable.

Ben's hands were trembling as he folded a blanket, and laid it on the animal's back to serve instead of a saddle.

"I'm a-goin' ter the still-house ter see ef Thad ever got thar," he said, when his mother appeared at the door.

He added, "I'm a-gittin' sorter skeered ez su'thin' mought hev happened ter him."

His grandfather hobbled out into the little porch. "Them roads air turrible rough fur that thar filly, ez ain't fairly broke good yit, nor used ter travel," he suggested.

"I'd gin four hunderd fillies, ef I hed 'em, jes' ter know that thar boy air safe an' sound," Ben declared, as he mounted.

He took the short cut, judging that, at the point where it crossed the river, the stream was still fordable. When he heard his brother's piteous cries for help, he quaked to think what might have happened to Thad if he had not recognized the presence of Satan in the moral shed-room, and summarily ejected him. The rainfall had been sufficient to aggregate considerable water in the gullies about the sink-hole, and these, emptying into the cavity and sending a continuous stream over the boy, had served to chill him through and through, and he had a pretty fair chance of being drowned, or dying from cold and exhaustion. Ben pressed on to the still-house at the best speed he could make, and such of the moonshiners as were half sober came out with ropes and a barrel, which they lowered into the cavity. Thad managed to crawl into the barrel, and, after several ineffectual attempts, he was drawn up through the sink-hole.

There was no formal reconciliation between the two boys. It was enough for Ben to feel Thad's reluctance to unloose his eager clutch upon his brother's arms, even after he had been lifted out upon the firm ground. And Thad knew that that complicated sound in Ben's throat was a sob, although, for the sake of the men who stood by, he strove to seem to be coughing.

"Right smart of an idjit, now, ain't ye?" demanded Ben, hustling back, so to speak, the tears that sought to rise in his eyes.

"Waal, stranger, how's yer filly?" retorted Thad, laughing in a gaspy fashion.

There was a tone of forgiveness in the inquiry. The answer caught the same spirit.

"Middlin',—thanky,—jes' middlin'," said Ben.

And then they and "dad" fared home together by the light of the moonshiners' lantern.

On a certain bold crag that juts far over a steep wooded mountain slope a red light was seen one moonless night in June. Sometimes it glowed intensely among the gray mists which hovered above the deep and sombre valley; sometimes it faded. Its life was the breath of the bellows, for a blacksmith's shop stands close beside the road that rambles along the brink of the mountain. Generally after sunset the forge is dark and silent. So when three small boys, approaching the log hut through the gloomy woods, heard the clink! clank! clink! clank! of the hammers, and the metallic echo among the cliffs, they stopped short in astonishment.

"Thar now!" exclaimed Abner Ryder desperately; "dad's at it fur true!"