The Project Gutenberg EBook of Flag and Fleet, by William Wood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Flag and Fleet

How the British Navy Won the Freedom of the Seas

Author: William Wood

Release Date: November 17, 2006 [EBook #19849]

Last updated: March 3, 2009

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FLAG AND FLEET ***

Produced by Al Haines

Thy way is in the sea, and

Thy path in the great waters,

and Thy footsteps are not known.

—Psalm LXXVII. v. 19.

The Sea is His: He made it,

Black gulf and sunlit shoal

From barriered bight to where the long

Leagues of Atlantic roll:

Small strait and ceaseless ocean

He bade each one to be:

The Sea is His: He made it—

And England keeps it free.

By pain and stress and striving

Beyond the nations' ken,

By vigils stern when others slept,

By lives of many men;

Through nights of storm, through dawnings

Blacker than midnights be—

This sea that God created,

England has kept it free.

Count me the splendid captains

Who sailed with courage high

To chart the perilous ways unknown—

Tell me where these men lie!

To light a path for ships to come

They moored at Dead Man's quay;

The Sea is God's—He made it,

And these men made it free.

Oh little land of England,

Oh mother of hearts too brave,

Men say this trust shall pass from thee

Who guardest Nelson's grave.

Aye, but these braggarts yet shall learn

Who'd hold the world in fee,

The Sea is God's—and England,

England shall keep it free.

—R. E. VERNČDE.

BY

Admiral-of-the-Fleet Sir David Beatty,

G.C.B., O.M., G.C.V.O., etc.

In acceding to the request to write a Preface for this volume I am moved by the paramount need that all the budding citizens of our great Empire should be thoroughly acquainted with the part the Navy has played in building up the greatest empire the world has ever seen.

Colonel Wood has endeavored to make plain, in a stirring and attractive manner, the value of Britain's Sea-Power. To read his Flag and Fleet will ensure that the lessons of centuries of war will be learnt, and that the most important lesson of them all is this—that, as an empire, we came into being by the Sea, and that we cannot exist without the Sea.

DAVID BEATTY,

2nd of June, 1919.

Who wants to be a raw recruit for life, all thumbs and muddle-mindedness? Well, that is what a boy or girl is bound to be when he or she grows up without knowing what the Royal Navy of our Motherland has done to give the British Empire birth, life, and growth, and all the freedom of the sea.

The Navy is not the whole of British sea-power; for the Merchant Service is the other half. Nor is the Navy the only fighting force on which our liberty depends; for we depend upon the United Service of sea and land and air. Moreover, all our fighting forces, put together, could not have done their proper share toward building up the Empire, nor could they defend it now, unless they always had been, and are still, backed by the People as a whole, by every patriot man and woman, boy and girl.

But while it takes all sorts to make the world, and very many different sorts to make and keep our British Empire of the Free, it is quite as true to say that all our other sorts together could not have made, and cannot keep, our Empire, unless the Royal Navy had kept, and keeps today, true watch and ward over all the British highways of the sea. None of the different parts of the world-wide British Empire are joined together by the land. All are joined together by the sea. Keep the seaways open and we live. Close them and we die.

This looks, and really is, so very simple, that you may well wonder why we have to speak about it here. But man is a land animal. Landsmen are many, while seamen are few; and though the sea is three times bigger than the land it is three hundred times less known. History is full of sea-power, but histories are not; for most historians know little of sea-power, though British history without British sea-power is like a watch without a mainspring or a wheel without a hub. No wonder we cannot understand the living story of our wars, when, as a rule, we are only told parts of what happened, and neither how they happened nor why they happened. The how and why are the flesh and blood, the head and heart of history; so if you cut them off you kill the living body and leave nothing but dry bones. Now, in our long war story no single how or why has any real meaning apart from British sea-power, which itself has no meaning apart from the Royal Navy. So the choice lies plain before us: either to learn what the Navy really means, and know the story as a veteran should; or else leave out, or perhaps mislearn, the Navy's part, and be a raw recruit for life, all thumbs and muddle-mindedness.

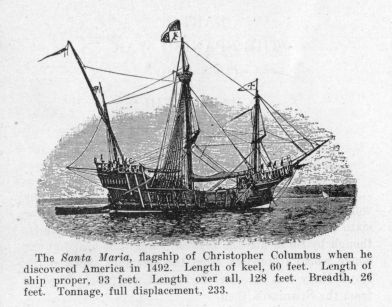

| VIII | OLD SPAIN AND NEW (1492-1571) |

| IX | THE ENGLISH SEA-DOGS (1545-1580) |

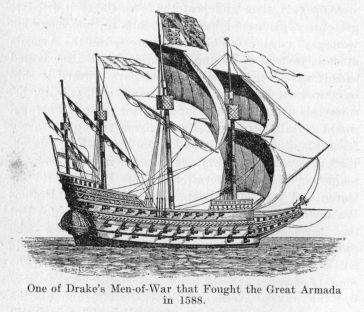

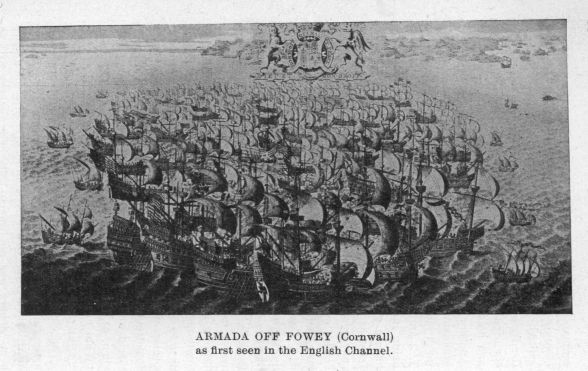

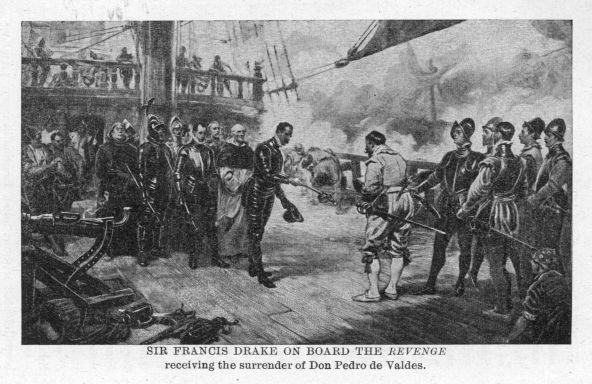

| X | THE SPANISH ARMADA (1588) |

| XI | THE FIRST DUTCH WAR (1623-1653) |

| XII | THE SECOND AND THIRD DUTCH WARS (1665-1673) |

| XX | A CENTURY OF BRITISH-FRENCH-AMERICAN PEACE (1815-1914) |

| XXI | A CENTURY OF MINOR BRITISH WARS (1815-1914) |

| XXII | THE HANDY MAN |

| XXIII | FIFTY YEARS OF WARNING (1864-1914) |

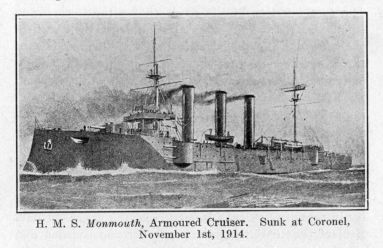

| XXIV | WAR (1914-1915) |

| XXV | JUTLAND (1916) |

| XXVI | SUBMARINING (1917-1918) |

| XXVII | SURRENDER! (1918) |

| XXVIII | WELL DONE! |

| POSTSCRIPT THE FREEDOM OF THE SEAS |

[Transcriber's note: The following two errata items have been applied to this e-book.]

ERRATA

Page XIII. For "Henry VII's" read "Henry VIII's."

Page 254. L. 20 for "facing the Germans" read "away from Scheer,"

Thousands and thousands of years ago a naked savage in southern Asia found that he could climb about quite safely on a floating log. One day another savage found that floating down stream on a log was very much easier than working his way through the woods. This taught him the first advantage of sea-power, which is, that you can often go better by water than land. Then a third savage with a turn for trying new things found out what every lumberjack and punter knows, that you need a pole if you want to shove your log along or steer it to the proper place.

By and by some still more clever savage tied two logs together and made the first raft. This soon taught him the second advantage of sea-power, which is, that, as a rule, you can carry goods very much better by water than land. Even now, if you want to move many big and heavy things a thousand miles you can nearly always do it ten times better in a ship than in a train, and ten times better in a train than by carts and horses on the very best of roads. Of course a raft is a poor, slow, clumsy sort of ship; no ship at all, in fact. But when rafts were the only "ships" in the world there certainly were no trains and nothing like one of our good roads. The water has always had the same advantage over the land; for as horses, trails, carts, roads, and trains began to be used on land, so canoes, boats, sailing ships, and steamers began to be used on water. Anybody can prove the truth of the rule for himself by seeing how much easier it is to paddle a hundred pounds ten miles in a canoe than to carry the same weight one mile over a portage.

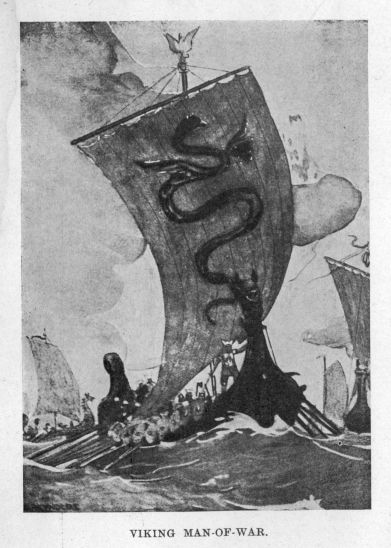

Presently the smarter men wanted something better than a little log raft nosing its slow way along through dead shallow water when shoved by a pole; so they put a third and longer log between the other two, with its front end sticking out and turning up a little. Then, wanting to cross waters too deep for a pole, they invented the first paddles; and so made the same sort of catamaran that you can still see on the Coromandel Coast in southern India. But savages who knew enough to take catamarans through the pounding surf also knew enough to see that a log with a hollow in the upper side of it could carry a great deal more than a log that was solid; and, seeing this, they presently began making hollows and shaping logs, till at last they had made a regular dug-out canoe. When Christopher Columbus asked the West Indian savages what they called their dug-outs they said canoas; so a boat dug out of a solid log had the first right to the word we now use for a canoe built up out of several different parts.

Dug-outs were sometimes very big. They were the Dreadnought battleships of their own time and place and people. When their ends were sharpened into a sort of ram they could stave in an enemy's canoe if they caught its side full tilt with their own end. Dug-out canoes were common wherever the trees were big and strong enough, as in Southern Asia, Central Africa, and on the Pacific Coast of America. But men have always been trying to invent something better than what their enemies have; and so they soon began putting different pieces together to make either better canoes or lighter ones, or to make any kind that would do as well as or better than the dug-out. Thus the ancient Britons had coracles, which were simply very open basket-work covered with skins. Their Celtic descendants still use canvas coracles in parts of Wales and Ireland, just as the Eskimos still use skin-covered kayaks and oomiaks. The oomiak is for a family with all their baggage. The kayak—sharp as a needle and light as a feather—is for a well-armed man. The oomiak is a cargo carrier. The kayak is a man-of-war.

When once men had found out how to make and use canoes they had also found out the third and final principle of sea-power, which is, that if you live beside the water and do not learn how to fight on it you will certainly be driven off it by some enemy who has learnt how to fight there. For sea-power in time of war simply means the power to use the sea yourself while stopping the enemy from using it. So the first duty of any navy is to keep the seaways open for friends and closed to enemies. And this is even more the duty of the British Navy than of any other navy. For the sea lies between all the different parts of the British Empire; and so the life-or-death question we have to answer in every great war is this: does the sea unite us by being under British control, or does it divide us by being under enemy control? United we stand: divided we fall.

At first sight you would never believe that sea-power could be lost or won as well by birchbarks as by battleships. But if both sides have the same sort of craft, or one side has none at all, then it does not matter what the sort is. When the Iroquois paddled their birch-bark canoes past Quebec in 1660, and defied the French Governor to stop them, they "commanded" the St. Lawrence just as well as the British Grand Fleet commanded the North Sea in the Great War; and for the same reason, because their enemy was not strong enough to stop them. Whichever army can drive its enemy off the roads must win the war, because it can get what it wants from its base, (that is, from the places where its supplies of men and arms and food and every other need are kept); while its enemy will have to go without, being unable to get anything like enough, by bad and roundabout ways, to keep up the fight against men who can use the good straight roads. So it is with navies. The navy that can beat its enemy from all the shortest ways across the sea must win the war, because the merchant ships of its own country, like its men-of-war, can use the best routes from the bases to the front and back again; while the merchant ships of its enemy must either lose time by roundabout voyages or, what is sure to happen as the war goes on, be driven off the high seas altogether.

The savages of long ago often took to the water when they found the land too hot for them. If they were shepherds, a tyrant might seize their flocks. If they were farmers, he might take their land away from them. But it was not so easy to bully fishermen and hunters who could paddle off and leave no trace behind them, or who could build forts on islands that could only be taken after fights in which men who lived mostly on the water would have a much better chance than men who lived mostly on the land. In this way the water has often been more the home of freedom than the land: liberty and sea-power have often gone together; and a free people like ourselves have nearly always won and kept freedom, both for themselves and others, by keeping up a navy of their own or by forming part of such an Empire as the British, where the Mother Country keeps up by far the greatest navy the world has ever seen.

The canoe navies, like other navies, did very well so long as no enemy came with something better. But when boats began to gain ground, canoes began to lose it. We do not know who made the first boat any more than we know who made the first raft or canoe. But the man who laid the first keel was a genius, and no mistake about it; for the keel is still the principal part of every rowboat, sailing ship, and steamer in the world. There is the same sort of difference between any craft that has a keel and one that has not as there is between animals which have backbones and those which have not. By the time boats were first made someone began to find out that by putting a paddle into a notch in the side of the boat and pulling away he could get a stronger stroke than he could with the paddle alone. Then some other genius, thousands of years after the first open boat had been made, thought of making a deck. Once this had been done, the ship, as we know her, had begun her glorious career.

But meanwhile sails had been in use for very many thousands of years. Who made the first sail? Nobody knows. But very likely some Asiatic savage hoisted a wild beast's skin on a stick over some very simple sort of raft tens of thousands of years ago. Rafts had, and still have, sails in many countries. Canoes had them too. Boats and ships also had sails in very early times, and of very various kinds: some made of skins, some of woven cloth, some even of wooden slats. But no ancient sail was more than what sailors call a wind-bag now; and they were of no use at all unless the wind was pretty well aft, that is, more or less from behind. We shall presently find out that tacking, (which is sailing against the wind), is a very modern invention; and that, within three centuries of its invention, steamers began to oust sailing craft, as these, in their turn, had ousted rowboats and canoes.

This chapter begins with a big surprise. But it ends with a bigger one still. When you look first at the title and then at the date, you wonder how on earth the two can go together. But when you remember what you have read in Chapter I you will see that the countries at the Asiatic end of the Mediterranean, though now called the Near East, were then the Far West, because emigrants from the older lands of Asia had gone no farther than this twelve thousand years ago. Then, as you read the present chapter, you will see emigrants and colonies moving farther and farther west along the Mediterranean and up the Atlantic shores of Europe, until, at last, two thousand years before Columbus, the new Far West consisted of those very shores of Spain and Portugal, France and the British Isles, from which the whole New Western World of North and South America was to be settled later on. The Atlantic shores of Europe, and not the Mediterranean shores of Asia and of Egypt, are called here "The First Far West" because the first really Western people grew up in Europe and became quite different from all the Eastern peoples. The Second Far West, two thousand years later, was America itself.

Westward Ho! is the very good name of a book about adventures in America when this Second Far West was just beginning. "Go West!" was the advice given to adventurous people in America during the nineteenth century. "The Last West and Best West" is what Canadians now call their own North-West. And it certainly is the very last West of all; for over there, across the Pacific, are the lands of southern Asia from which the first emigrants began moving West so many thousand years ago. Thus the circuit of the World and its migrations is now complete; and we can at last look round and learn the whole story, from Farthest East to Farthest West.

Most of it is an old, old story from the common points of view; and it has been told over and over again by many different people and in many different ways. But from one point of view, and that a most important point, it is newer now than ever. Look at it from the seaman's point of view, and the whole meaning changes in the twinkling of an eye, becoming new, true, and complete. Nearly all books deal with the things of the land, and of the land alone, their writers forgetting or not knowing that the things of the land could never have been what they are had it not been for the things of the sea. Without the vastly important things of the sea, without the war fleets and merchant fleets of empires old and new, it is perfectly certain that the world could not have been half so good a place to live in; for freedom and the sea tend to go together. True of all people, this is truer still of us; for the sea has been the very breath of British life and liberty ever since the first hardy Norseman sprang ashore on English soil.

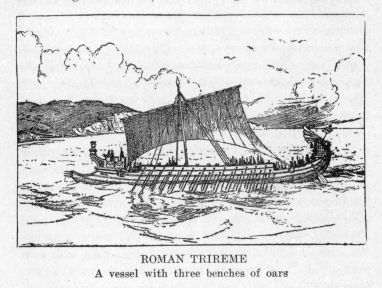

Nobody knows how the Egyptians first learnt ship-building from the people farther East. But we do know that they were building ships in Egypt seven thousand years ago, that their ninth king was called Betou, which means "the prow of a ship", and that his artists carved pictures of boats five hundred years older than the Great Pyramid. These pictures, carved on the tombs of the kings, are still to be seen, together with some pottery, which, coming from the Balkans, shows that Betou had boats trading across the eastern end of the Mediterranean. A picture carved more than six thousand years ago shows an Egyptian boat being paddled by fourteen men and steered with paddles by three more on the right-hand side of the stern as you look toward the bow. Thus the "steer-board" (or steering side) was no new thing when its present name of "starboard" was used by our Norse ancestors a good many hundred years ago. The Egyptians, steering on the right-hand side, probably took in cargo on the left side or "larboard", that is, the "load" or "lading" side, now called the "port" side, as "larboard" and "starboard" sounded too much alike when shouted in a gale.

Up in the bow of this old Egyptian boat stood a man with a pole to help in steering down the Nile. Amidships stood a man with a cat-o'-nine-tails, ready to slash any one of the wretched slave paddlers who was not working hard. All through the Rowing Age, for thousands and thousands of years, the paddlers and rowers were the same as the well-known galley-slaves kept by the Mediterranean countries to row their galleys in peace and war. These galleys, or rowing men-of-war, lasted down to modern times, as we shall soon see. They did use sails; but only when the wind was behind them, and never when it blew really hard. The mast was made of two long wooden spars set one on each side of the galley, meeting at the head, and strengthened in between by braces from one spar to another. As time went on better boats and larger ones were built in Egypt. We can guess how strong they must have been when they carried down the Nile the gigantic blocks of stone used in building the famous Pyramids. Some of these blocks weigh up to sixty tons; so that both the men who built the barges to bring them down the Nile and those who built these huge blocks into the wonderful Pyramids must have known their business pretty well a thousand years before Noah built his Ark.

The Ark was built in Mesopotamia, less than five thousand years ago, to save Noah from the flooded Euphrates. The shipwrights seem to have built it like a barge or house-boat. If so, it must have been about fifteen thousand tons, taking the length of the cubit in the Bible story at eighteen inches. It was certainly not a ship, only some sort of construction that simply floated about with the wind and current till it ran aground. But Mesopotamia and the shores of the Persian Gulf were great places for shipbuilding. They were once the home of adventurers who had come West from southern Asia, and of the famous Phoenicians, who went farther West to find a new seaboard home along the shores of Asia Minor, just north of Palestine, where they were in the shipping business three thousand years ago, about the time of the early Kings of Israel.

These wonderful Phoenicians touch our interest to the very quick; for they were not only the seamen hired by "Solomon in all his glory" but they were also the founders of Carthage and the first oversea traders with the Atlantic coasts of France and the British Isles. Their story thus goes home to all who love the sea, the Bible, and Canada's two Mother Lands. They had shipping on the Red Sea as well as on the Mediterranean; and it was their Red Sea merchant vessels that coasted Arabia and East Africa in the time of Solomon (1016-976 B.C.). They also went round to Persia and probably to India. About 600 B.C. they are said to have coasted round the whole of Africa, starting from the Red Sea and coming back by Gibraltar. This took them more than two years, as they used to sow wheat and wait on shore till the crop was ripe. Long before this they had passed Gibraltar and settled the colony of Tarshish, where they found silver in such abundance that "it was nothing accounted of in the days of Solomon." We do not know whether it was "the ships of Tarshish and of the Isles" that first felt the way north to France and England. But we do know that many Phoenicians did trade with the French and British Celts, who probably learnt in this way how to build ships of their own.

For two thousand years Eastern fleets and armies tried to conquer Europe. Sometimes hundreds of years would pass without an attack. But the result was always the same—the triumph of West over East; and the cause of each triumph was always the same—the sea-power of the West. Without those Western navies the Europe and America we know today could never have existed. There could have been no Greek civilization, no Roman government, no British Empire, and no United States. First, the Persians fought the Greeks at Salamis in 480 B.C. Then Carthage fought Rome more than two hundred years later. Finally, the conquering Turks were beaten by the Spaniards at Lepanto more than two thousand years after Salamis, but not far from the same spot, Salamis being ten miles from Athens and Lepanto a hundred.

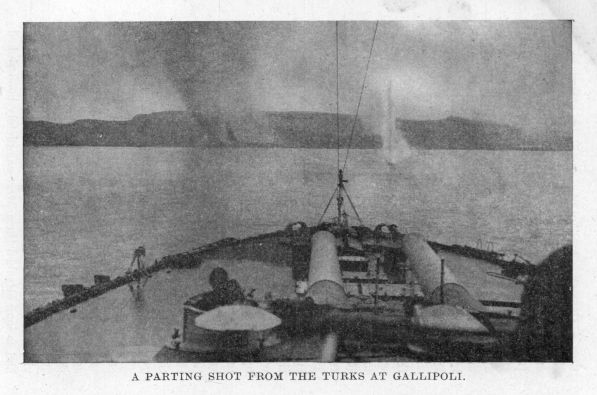

Long before Salamis the Greeks had been founding colonies along the Mediterranean, among them some on the Asiatic side of the Aegean Sea, where the French and British fleets had so much to do during the Gallipoli campaign of 1915 against the Turks and Germans. Meanwhile the Persians had been fighting their way north-westwards till they had reached the Aegean and conquered most of the Greeks and Phoenicians there. Then the Greeks at Athens sent a fleet which landed an army that burnt the city of Sardis, an outpost of Persian power. Thereupon King Darius, friend of the Prophet Daniel, vowed vengeance on Athens, and caused a trusty servant to whisper in his ear each day, "Master, remember Athens!"

Now, the Persians were landsmen, with what was then the greatest army in the world, but with a navy and a merchant fleet mostly manned by conquered Phoenicians and Greek colonists, none of whom wanted to see Greece itself destroyed. So when Darius met the Greeks at Marathon his fleet and army did not form the same sort of United Service that the British fleet and army form. He was beaten back to his ships and retired to Asia Minor. But "Remember Athens!" was always in his mind. So for ten years he and his son Xerxes prepared a vast armada against which they thought no other force on earth could stand. But, like the Spanish Armada against England two thousand years later, this Persian host was very much stronger ashore than afloat. Its army was so vast that it covered the country like a swarm of locusts. At the world-famous pass of Thermopylae the Spartan king, Leonidas, waited for the Persians. Xerxes sent a summons asking the Greeks to surrender their arms. "Come and take them," said Leonidas. Then wave after wave of Persians rushed to the attack, only to break against the dauntless Greeks. At last a vile traitor told Xerxes of another pass (which the Greeks had not men enough to hold, though it was on their flank). He thus got the chance of forcing them either to retreat or be cut off. Once through this pass the Persians overran the country; and all the Spartans at Thermopylae died fighting to the last.

Only the Grecian fleet remained. It was vastly out-numbered by the Persian fleet. But it was manned by patriots trained to fight on the water; while the Persians themselves were nearly all landsmen, and so had to depend on the Phoenicians and colonial Greek seamen, who were none too eager for the fray. Seeing the Persians too densely massed together on a narrow front the Greek commander, Themistocles, attacked with equal skill and fury, rolled up the Persian front in confusion on the mass behind, and won the battle that saved the Western World. The Persians lost two hundred vessels against only forty Greek. But it was not the mere loss of vessels, or even of this battle of Salamis itself, that forced Xerxes to give up all hopes of conquest. The real reason was his having lost the command of the sea. He knew that the victorious Greeks could now beat the fighting ships escorting his supply vessels coming overseas from Asia Minor, and that, without the constant supplies of men, arms, food, and everything else an army needs, his army itself must wither away.

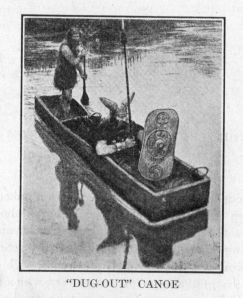

Two hundred and twenty years later the sea-power of the Roman West beat both the land- and sea-power of the Carthaginian East; and for the very same reason. Carthage was an independent colony of Phoenicians which had won an empire in the western Mediterranean by its sea-power. It held a great part of Spain, the whole of Sardinia, most of Sicily, and many other islands. The Romans saw that they would never be safe as long as Carthage had the stronger navy; so they began to build one of their own. They copied a Carthaginian war galley that had been wrecked; and meanwhile taught their men to row on benches set up ashore. This made the Carthaginians laugh and led them to expect an easy victory. But the Romans were thorough in everything they did, and they had the best trained soldiers in the world. They knew the Carthaginians could handle war galleys better than they could themselves; so they tried to give their soldiers the best possible chance when once the galleys closed. They made a sort of drawbridge that could be let down with a bang on the enemy boats and there held fast by sharp iron spikes biting into the enemy decks. Then their soldiers charged across and cleared everything before them.

The Carthaginians never recovered from this first fatal defeat at Mylae in 260 B.C., though Carthage itself was not destroyed for more than a century afterwards, and though Hannibal, one of the greatest soldiers who ever lived, often beat the Romans in the meantime. All sorts of reasons, many of them true enough in their way, are given for Hannibal's final defeat. But sea-power, the first and greatest of all, is commonly left out. His march round the shores of the western Mediterranean and his invasion of Italy from across the Alps will remain one of the wonders of war till the end of history. But the mere fact that he had to go all the way round by land, instead of straight across by water, was the real prime cause of his defeat. His forces simply wore themselves out. Why? Look at the map and you will see that he and his supplies had to go much farther by land than the Romans and their supplies had to go by water because the Roman victory over the Carthaginian fleet had made the shortest seaways safe for Romans and very unsafe for Carthaginians. Then remember that carrying men and supplies by sea is many times easier than carrying them by land; and you get the perfect answer.

When Caesar was conquering the Celts of Western France he found that one of their strongest tribes, the Veneti, had been joined by two hundred and twenty vessels manned by their fellow-Celts from southern Britain. The united fleets of the Celts were bigger than any Roman force that Caesar could get afloat. Moreover, Caesar had nothing but rowboats, which he was obliged to build on the spot; while the Celts had real ships, which towered above his rowboats by a good ten feet. But, after cutting the Celtic rigging with scythes lashed to poles, the well-trained Roman soldiers made short work of the Celts. The Battle of the Loire seems to have been the only big sea fight the Celts of Britain ever fought. After this they left the sea to their invaders, who thus had a great advantage over them ashore.

The fact is that the Celts of the southern seaports were the only ones who understood shipbuilding, which they had learnt from the Phoenicians, and the only ones who were civilized enough to unite among themselves and with their fellow-Celts in what now is France but then was Gaul. The rest were mere tribesmen under chiefs who were often squabbling with one another, and who never formed anything like an all-Celtic army. For most of them a navy was out of the question, as they only used the light, open-work, basket-like coracles covered with skins—about as useful for fighting the Romans at sea as bark canoes would be against real men-of-war. The Roman conquest of Britain was therefore made by the army, each conqueror, from Caesar on, winning battles farther and farther north, until a fortified Roman wall was built across the narrow neck of land between the Forth and Clyde. Along these thirty-six miles the Romans kept guard against the Picts and other Highland tribes.

The Roman fleet was of course used at all times to guard the seaways between Britain and the rest of the Roman Empire, as well as to carry supplies along the coast when the army was fighting near by. This gave the Romans the usual immense advantage of sea-transport over land-transport, never less than ten to one and often very much more. The Romans could thus keep their army supplied with everything it needed. The Celts could not. Eighteen hundred years after Caesar's first landing in Britain, Wolfe, the victor of Quebec, noticed the same immense advantage enjoyed by King George's army over Prince Charlie's, owing to the same sort of difference in transport, King George's army having a fleet to keep it well supplied, while Prince Charlie's had nothing but slow and scanty land transport, sometimes more dead than alive.

The only real fighting the Romans had to do afloat was against the Norsemen, who sailed out of every harbour from Norway round to Flanders and swooped down on every vessel or coast settlement they thought they had a chance of taking. To keep these pirates in check Carausius was made "Count of the Saxon Shore". It was a case of setting a thief to catch a thief; for Carausius was a Fleming and a bit of a pirate himself. He soon became so strong at sea that he not only kept the other Norsemen off but began to set up as a king on his own account. He seized Boulogne, harried the Roman shipping on the coasts of France, and joined forces with those Franks whom the Romans had sent into the Black Sea to check the Scythians and other wild tribes from the East. The Franks were themselves Norsemen, who afterwards settled in Gaul and became the forefathers of the modern French. So Rome was now threatened by a naval league of hardy Norsemen, from the Black Sea, through the Mediterranean, and all the way round to that "Saxon Shore" of eastern Britain which was itself in danger from Norsemen living on the other side of the North Sea. Once more, however, the Romans won the day. The Emperor Constantius caught the Franks before they could join Carausius and smashed their fleet near Gibraltar. He then went to Gaul and made ready a fleet at the mouth of the Seine, near Le Havre, which was a British base during the Great War against the Germans. Meanwhile Carausius was killed by his second-in-command, Allectus, who sailed from the Isle of Wight to attack Constantius, who himself sailed for Britain at the very same time. A dense fog came on. The two fleets never met. Constantius landed. Allectus then followed him ashore and was beaten and killed in a purely land battle.

This was a little before the year 300; by which time the Roman Empire was beginning to rot away, because the Romans were becoming softer and fewer, and because they were hiring more and more strangers to fight for them, instead of keeping up their own old breed of first-class fighting men. By 410 Rome itself was in such danger that they took their last ships and soldiers away from Celtic Britain, which at once became the prey of the first good fighting men who came that way; because the Celts, never united enough to make a proper army or navy of their own, were now weaker than ever, after having had their country defended by other people for the last four hundred years.

The British Empire leads the whole world both in size and population. It ended the Great War with the greatest of all the armies, the greatest of all the navies, and the greatest of all the mercantile marines. Better still, it not only did most towards keeping its own—which is by far the oldest—freedom in the world, but it also did most towards helping all its Allies to be free. There are many reasons why we now enjoy these blessings. But there are three without which we never could have had a single one. The first, of course, is sea-power. But this itself depends on the second reason, which, in its turn, depends upon the third. For we never could have won the greatest sea-power unless we had bred the greatest race of seamen. And we never could have bred the greatest race of seamen unless we ourselves had been mostly bred from those hardy Norsemen who were both the terror and the glory of the sea.

Many thousands of years ago, when the brown and yellow peoples of the Far South-East were still groping their way about their steamy Asian rivers and hot shores, a race of great, strong, fair-haired seamen was growing in the North. This Nordic race is the one from which most English-speaking people come, the one whose blood runs in the veins of most first-class seamen to the present day, and the one whose descendants have built up more oversea dominions, past and present, than have been built by all the other races, put together, since the world began.

To the sturdy Nordic stock belonged all who became famous as Vikings, Berserkers, and Hardy Norsemen, as well as all the Anglo-Saxons, Jutes, Danes, and Normans, from whom came most of the people that made the British Empire and the United States. "Nordic" and "Norse" are, therefore, much better, because much truer, words than "Anglo-Saxon", which only names two of the five chief tribes from which most English-speaking people come, and which is not nearly so true as "Anglo-Norman" to describe the people, who, once formed in England, spread over southern Scotland and parts of Ireland, and who have also gone into every British, American, or foreign country that has ever been connected with the sea.

When the early Nordics outgrew their first home beside the Baltic they began sailing off to seek their fortune overseas. In course of time they not only spread over the greater part of northern Europe but went as far south as Italy and Spain, where the good effects of their bracing blood have never been lost. They even left descendants among the Berbers of North Africa; and, as we have learnt already, some of them went as far east as the Black Sea. The Belgians, Dutch, and Germans of Caesar's day were all Nordic. So were the Franks, from whom France takes its name. The Nordic blood, of course, became more or less mingled with that of the different peoples the Nordic tribes subdued; and new blood coming in from outside made further changes still. But the Nordic strain prevailed, as that of the conquerors, even where the Nordic folk did not outnumber all the rest, as they certainly did in Great Britain. The Franks, whose name meant "free men", at last settled down with the Gauls, who outnumbered them; so that the modern French are a blend of both. But the Gauls were the best warriors of all the Celts: it took Caesar eight years to conquer them. So we know that Frenchmen got their soldier blood from both sides. We also know that they learnt a good deal of their civilization from the Romans and passed it on to the empire-building Normans, who brought more Nordic blood into France. The Normans in their turn passed it on to the Anglo-Saxons, who, with the Jutes and Danes, form the bulk, as the Normans form the backbone, of most English-speaking folk within the British Empire. The Normans are thus the great bond of union between the British Empire and the French. They are the Franco-British kinsfolk of the sea.

We must not let the fact that Prussia borders on the North Sea and the Baltic mislead us into mistaking the Prussians for the purest offspring of the Nordic race. They are nothing of the kind. Some of the finest Nordics did stay near their Baltic home. But these became Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes; while nearly all the rest of the cream of this mighty race went far afield. Its Franks went into France by land. Its Normans went by sea. Others settled in Holland and Belgium and became the Dutch and Flemings of today. But the mightiest host of hardy Norsemen crossed the North Sea to settle in the British Isles; and from this chosen home of merchant fleets and navies the Nordic British have themselves gone forth as conquering settlers across the Seven Seas.

The Prussians are the least Nordic of all the Germans, and most Germans are rather the milk than the cream of the Nordic race; for the cream generally sought the sea, while the milk stayed on shore. The Prussians have no really Nordic forefathers except the Teutonic Knights, who killed off the Borussi or Old-Prussian savages, about seven hundred years ago, and then settled the empty land with their soldiers of fortune, camp-followers, hirelings, and serfs. These gangs had been brought together, by force or the hope of booty, from anywhere at all. The new Prussians were thus a pretty badly mixed lot; so the Teutonic Knights hammered them into shape as the newer Prussians whom Frederick the Great in the eighteenth century and Bismarck in the nineteenth turned into a conquering horde. The Kaiser's newest Prussians need no description here. We all know him and them; and what became of both; and how it served them right.

The first of the hardy Norsemen to arrive in England with a regular fleet and army were the two brothers, Hengist and Horsa, whom the Celts employed to defend them against the wild Picts that were swarming down from the north. The Picts once beaten, the Celts soon got into the same troubles that beset every people who will not or can not fight for themselves. More and more Norsemen kept coming to the Isle of Thanet, the easternmost point of Kent, and disputes kept on growing between them and the Celts over pay and food as well as over the division of the spoils. The Norsemen claimed most of the spoil, because their sword had won it. The Celts thought this unfair, because the country was their own. It certainly was theirs at that time. But they had driven out the people who had been there before them; so when they were themselves driven out they suffered no more than what they once had made these others suffer.

Presently the Norsemen turned their swords on the Celts and began a conquest that went on from father to son till there were hardly any Celts left in the British Isles outside of Wales, the Highlands of Scotland, and the greater part of Ireland. Every place easily reached from the sea fell into the hands of the Norsemen whenever they chose to take it; for the Celts never even tried to have a navy. This, of course, was the chief reason why they lost the war on land; because the Norsemen, though fewer by far at first, could move men, arms, and supplies ten times better than the Celts whenever the battlefields were anywhere near the sea.

Islands, harbours, and navigable rivers were often held by the Norsemen, even when the near-by country was filled with Celts. The extreme north of Scotland, like the whole of the south, became Norse, as did the northern islands of Orkney and Shetland. Scapa Flow, that magnificent harbour in the Orkneys, was a stronghold of Norsemen many centuries before their descendants manned the British Grand Fleet there during the recent war. The Isle of Man was taken by Norsemen. Dublin, Waterford, and other Irish cities were founded by them. They attacked Wales from Anglessey; and, wherever they conquered, their armies were based on the sea.

If you want to understand how the British Isles changed from a Celtic to a Nordic land, how they became the centre of the British Empire, and why they were the Mother Country from which the United States were born, you must always view the question from the sea. Take the sea as a whole, together with all that belongs to it—its islands, harbours, shores, and navigable rivers. Then take the roving Norsemen as the greatest seamen of the great seafaring Nordic race. Never mind the confusing lists of tribes and kings on either side—the Jutes and Anglo-Saxons, the Danes and Normans, on one side, and the Celts of England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, on the other; nor yet the different dates and places; but simply take a single bird's-eye view of all the Seven Seas as one sea, of all the British Norsemen as one Anglo-Norman folk, and of all the centuries from the fifth to the twentieth as a single age; and then you can quite easily understand how the empire of the sea has been won and held by the same strong "Hardy-Norseman" hands these fifteen hundred years.

There is nothing to offend the Celts in this. They simply tried to do what never can be done: that is, they tried to hold a sea-girt country with nothing but an army, while their enemy had an army and a fleet. They fought well enough in the past on many a stricken field to save any race's honour; and none who know the glorious deeds of the really Celtic Highland, Welsh, or Irish regiments can fail to admire them now. But this book is about seamen and the sea, and how they have changed the fate of landsmen and the land. So we must tell the plain truth about the Anglo-Norman seamen without whom there could be no British Empire and no United States. The English-speaking peoples owe a great deal to the Celts; and there is Celtic blood in a good many who are of mostly Nordic stock. But the British Empire and the American Republic were founded and are led more by Anglo-Normans than even Anglo-Normans know. For the Anglo-Normans include not only the English and their descendants overseas but many who are called Scotch and Irish, because, though of Anglo-Norman blood, they or their forefathers were born in Scotland or Ireland. Soldiers and sailors like Wellington, Kitchener, and Beatty are as Anglo-Norman by descent as Marlborough, Nelson, and Drake, though all three were born in Ireland. They are no more Irish Celts than the English-speaking people in the Province of Quebec are French-Canadians. They might have been as good or better if born Irish Celts or French-Canadians. But that is not the point. The point is simply a fact without which we cannot understand our history; and it is this: that, for all we owe to other folk and other things than fleets, our sea-girt British Empire was chiefly won, and still is chiefly kept, by warriors of the sea-borne "Hardy-Norseman" breed.

Desire in my heart ever urges my spirit to wander,

To seek out the home of the stranger in lands afar off.

There is no one that dwells on earth so exalted in mind,

So large in his bounty, nor yet of such vigorous youth,

Nor so daring in deeds, nor to whom his liege lord is so kind,

But that he has always a longing, a sea-faring passion

For what the Lord God shall bestow, be it honour or death.

No heart for the harp has he, nor for acceptance of treasure,

No pleasure has he in a wife, no delight in the world,

Nor in aught save the roll of the billows; but always a longing,

A yearning uneasiness hastens him on to the sea.

Anonymous.

Translated from the Anglo-Saxon.

The Celts had been little more than a jumble of many different tribes before the Romans came. The Romans had ruled England and the south of Scotland as a single country. But when they left it the Celts had let it fall to pieces again. The Norsemen tried, time after time, to make one United Kingdom; but they never quite succeeded for more than a few years. They had to wait for the empire-building Normans to teach them how to make, first, a kingdom and then an empire that would last.

Yet Offa, Edgar, and Canute went far towards making the first step by trying to raise a Royal Navy strong enough to command at least the English sea. Offa, king of Mercia or Middle England (757-796) had no sooner fought his way outwards to a sure foothold on the coast than he began building a fleet so strong that even the great Emperor Charlemagne, though ruling the half of Europe, treated him on equal terms. Here is Offa's good advice to all future kings of England: "He who would be safe on land must be supreme at sea." Alfred the Great (871-901) was more likely to have been thinking of the navy than of anything else when, as a young man hiding from the Danes, he forgot to turn the cakes which the housewife had left him to watch. Anyhow he tried the true way to stop the Danes, by attacking them before they landed, and he caused ships of a new and better kind to be built for the fleet. Edgar (959-975) used to go round Great Britain every year inspecting the three different fleets into which his navy was divided; one off the east of England, another off the north of Scotland, and the third in the Irish Sea. It is said that he was once rowed at Chester on the River Dee by no less than eight kings, which showed that he was following Offa's advice by making his navy supreme over all the neighbouring coasts of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.

After Edgar's death the Danes held command of the sea. They formed the last fierce wave of hardy Norsemen to break in fury on the English shore and leave descendants who are seamen to the present day. Nelson, greatest of all naval commanders, came from Norfolk, where Danish blood is strongest. Most of the fishermen on the east coast of Great Britain are of partly Danish descent; and no one served more faithfully through the Great War than these men did against the submarines and mines. King George V, whose mother is a Dane, and who is himself a first-rate seaman, must have felt a thrill of ancestral pride in pinning V.C.'s over their undaunted hearts. Fifty years before the Norman conquest Canute the Dane became sole king of England. He had been chosen King of Denmark by the Danish Fleet. But he was true to England as well; and in 1028, when he conquered Norway, he had fifty English vessels with him.

Meanwhile another great Norseman, Leif Ericsson, seems to have discovered America at the end of the tenth century: that is, he was as long before Columbus as Columbus was before our own day. In any case Norsemen settled in Iceland and discovered Greenland; so it may even be that the "White Eskimos" found by the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913 were the descendants of Vikings lost a thousand years ago. The Saga of Eric the Red tells how Leif Ericsson found three new countries in the Western World—Helluland, Markland, and Vinland. As two of these must have been Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, which Cabot discovered with his English crew in 1497, it is certain that Canada was seen first either by Norsemen or by their descendants.

The Norse discovery of America cannot be certainly proved like the discoveries made by Cabot and Columbus. But one proved fact telling in favour of the Norsemen is that they were the only people who built vessels "fit to go foreign" a thousand years ago. All other people hugged the shore for centuries to come. The Norsemen feared not any sea.

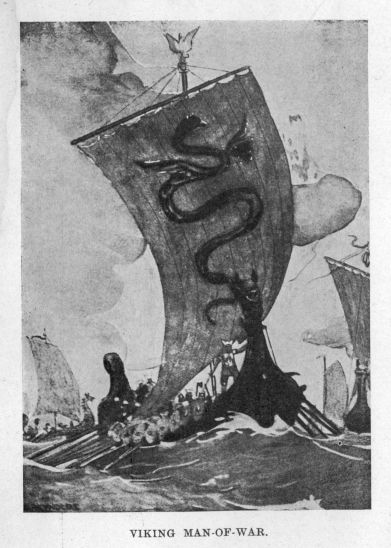

Some years ago a Viking (or Warrior's) ship, as old as those used by Ericsson, was found in the "King's Mound" in Gokstad, Southern Norway. Seated in her was the skeleton of the Viking Chief who, as the custom used to be, was buried in his floating home. He must have stood well over six foot three and been immensely strong, judging by his deep chest, broad shoulders, and long arms fit to cleave a foeman at a single stroke. This Viking vessel is so well shaped to stand the biggest waves, and yet slip through the water with the greatest ease, that she could be used as a model now. She has thirty-two oars and a big square sail on a mast, which, like the one in the old Egyptian boat we were talking of in Chapter II, could be quickly raised or lowered. If she had only had proper sails and rigging she could have tacked against the wind. But, as we shall soon see, the art of tacking was not invented till five centuries later; though then it was done by an English descendant of the Vikings.

Eighty foot long and sixteen in the beam, this Viking vessel must have looked the real thing as she scudded before a following wind or dashed ahead when her thirty-two oars were swept through the water by sixty-four pairs of the strongest arms on earth. Her figure-head has gone; but she probably had a fierce dragon over the bows, just ready to strike. Her sides were hung with glittering shields; and when mere landsmen saw a Viking fleet draw near, the oars go in, the swords come out, and Vikings leap ashore—no wonder they shivered in their shoes!

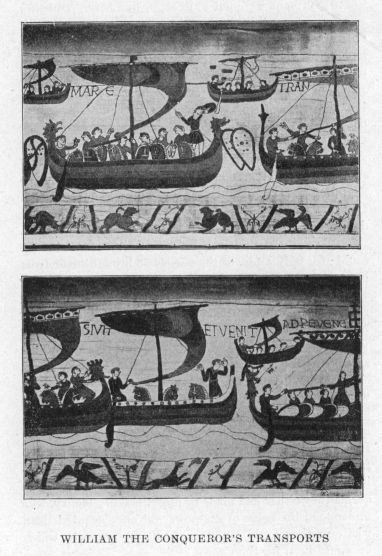

It was in this way that the Normans first arrived in Normandy and made a home there in spite of Franks and Gauls, just as the Danes made English homes in spite of Celts and Anglo-Saxons. There was no navy to oppose them. Neither was there any fleet to oppose William the Conqueror in 1066, when he crossed the Channel to seize the English Crown. Harold of England had no great fleet in any case; and what he had was off the Yorkshire coast, where his brother had come to claim the Crown, backed by the King of Norway. The Battle of Hastings, which made William king of England, was therefore a land battle only. But the fact that William had a fleet in the Channel, while Harold had not, gave William the usual advantage in the campaign. From that day to this England has never been invaded; and for the best of all reasons—because no enemy could ever safely pass her fleet.

The Normans at last gave England what none of her other Norsemen gave her, the power of becoming the head and heart of the future British Empire. The Celts, Danes, Jutes, and Anglo-Saxons had been fusing together the iron of their natures to make one strong, united British race. The Normans changed this iron into steel: well tempered, stronger than iron could be, and splendidly fit for all the great work of imperial statesmen as well as for that of warriors by land and sea.

The Normans were not so great in numbers. But they were very great in leadership. They were a race of rulers. Picked men of Nordic stock to start with, they had learnt the best that France could teach them: Roman law and order and the art of founding empires, Frankish love of freedom, a touch of Celtic wit, and the new French civilization. They went all over seaboard Europe, conquerors and leaders wherever they went. But nowhere did they set their mark so firmly and so lastingly as in the British Isles. They not only conquered and became leaders among their fellow-Norsemen but they went through most of Celtic Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, founding many a family whose descendants have helped to make the Empire what it is.

William the Conqueror built a fleet as soon as he could; for only a few of the vessels he brought over from Normandy were of any use as men-of-war. But there were no great battles on the water till the one off the South Foreland more than a century after his death. He and the kings after him always had to keep their weather eye open for Danes and other rovers of the sea as well as for the navy of the kings of France. But, except when Henry II went to Ireland in 1171, there was no great expedition requiring a large fleet. Strongbow and other ambitious nobles had then begun conquering parts of Ireland on their own account. So Henry recalled his Englishmen, lest they should go too far without him, and held a court at which they promised to give him, as their liege overlord, all the conquests they either had made or might make. Henry, who understood the value of sea-power, at once granted them whatever they could conquer, except the seaports, which he would keep for the Crown.

When Henry died Richard the Lion-Hearted and Philip Augustus of France agreed to join in a great Crusade. Zeal for the Christian religion and love of adventure together drew vast numbers of Crusaders to the Holy Land. But sea-power also had a great deal to do with the Crusades. The Saracens, already strong at sea in the East, were growing so much stronger that Western statesmen thought it high time to check them, lest their fleets should command the whole Mediterranean and perhaps the seas beyond.

In 1190 Richard joined his fleet at Messina, in Sicily, where roving Normans were of course to be found as leaders in peace and war. Vinesauf the historian, who was what we should now call a war correspondent, wrote a glowing account of the scene. "As soon as the people heard of his arrival they rushed in crowds to the shore to behold the glorious King of England, and saw the sea covered with innumerable galleys. And the sound of trumpets from afar, with the sharper blasts of clarions, resounded in their ears. And they saw the galleys rowing near the land, adorned and furnished with all kinds of arms, with countless pennons floating in the breeze, ensigns at the tops of lances, the beaks of the galleys beautified by painting, and glittering shields hanging from the prows. The sea looked as if it was boiling from the vast number of oar blades in it. The trumpets grew almost deafening. And each arrival was greeted with bursts of cheering. Then our splendid King stood up on a prow higher than all the rest, with a gorgeously dressed staff of warriors about him, and surveyed the scene with pleasure. After this he landed, beautifully dressed, and showed himself graciously to all who approached him."

The whole English fleet numbered about two hundred and thirty vessels, with stores for a year and money enough for longer still. A southerly gale made nearly everybody sea-sick; for the Italian rowers in the galleys were little better as seamen than the soldiers were, being used to calm waters. Some vessels were wrecked on the rocks of Cyprus, when their crews were robbed by the king there. This roused the Lion-Hearted, who headed a landing party which soon brought King Comnenus to his senses. Vinesauf wrote to say that when Comnenus sued for peace Richard was mounted on a splendid Spanish war-horse and dressed in a red silk tunic embroidered with gold. Red seems to have been a favourite English war colour from very early times. The red St. George's Cross on a white field was flown from the masthead by the commander-in-chief of the fleet, just as it is today. On another flag always used aboard ship three British lions were displayed.

After putting Comnenus into silver chains and shutting him up in a castle Richard set two governors over Cyprus, which thus became the first Eastern possession of the British Crown. Seven centuries later it again came into British hands, this time to stay. Richard then sailed for the siege of Acre in Palestine. But on the way he met a Turkish ship of such enormous size that she simply took Vinesauf's breath away. No one thought that any ship so big had ever been built before, "unless it might be Noah's Ark", Richard had a hundred galleys. The Turkish ship was quite alone; but she was a tough nut to crack, for all that. She was said to have had fifteen hundred men aboard, which might be true, as soldiers being rushed over for the defence of Acre were probably packed like herrings in a barrel. As this was the first English sea fight in the Crusades, and the first in which a King of all England fought, the date should be set down: the 7th of June, 1191.

The Turk was a very stoutly built vessel, high out of the water and with three tall masts, each provided with a fighting top from which stones and jars of Greek fire could be hurled down on the galleys. She also had "two hundred most deadly serpents, prepared for killing Christians." Altogether, she seems to have been about as devilish a craft as even Germans could invent. As she showed no colours Richard hailed her, when she said she was a French ship bound for Acre. But as no one on board could speak French he sent a galley to test her. As soon as the Englishmen went near enough the Turks threw Greek fire on them. Then Richard called out: "Follow me and take her! If she escapes you lose my love for ever. If you take her, all that is in her will be yours." But when the galleys swarmed round her she beat them off with deadly showers of arrows and Greek fire. There was a pause, and the galleys seemed less anxious to close again. Then Richard roared out: "If this ship escapes every one of you men will be hanged!" After this some men jumped overboard with tackle which they made fast to the Turkish rudder. They and others then climbed up her sides, having made ropes fast with grapnels. A furious slashing and stabbing followed on deck. The Turks below swarmed up and drove the English overboard. Nothing daunted, Richard prepared to ram her. Forming up his best galleys in line-abreast he urged the rowers to their utmost speed. With a terrific rending crash the deadly galley beaks bit home. The Turk was stove in so badly that she listed over and sank like a stone. It is a pity that we do not know her name. For she fought overwhelming numbers with a dauntless courage that nothing could surpass. As she was the kind of ship then called a "dromon" she might be best remembered as "the dauntless dromon."

King John, who followed Richard on the throne of England, should be known as John the Unjust. He was hated in Normandy, which Philip Augustus of France took from him in 1204. He was hated in England, where the English lords forced him to sign Magna Charta in 1215. False to his word, he had no sooner signed it than he began plotting to get back the power he had so shamefully misused; and the working out of this plot brought on the first great sea fight with the French.

Looking out for a better king the lords chose Prince Louis of France, who landed in England next year and met them in London. But John suddenly died. His son, Henry III, was only nine. So England was ruled by William Marshal, the great Earl of Pembroke, one of the ablest patriots who ever lived. Once John was out of the way the English lords who had wrung from him the great charter of English liberties became very suspicious of Louis and the French. A French army was besieging Lincoln in 1217, helped by the English followers of Louis, when the Earl Marshal, as Pembroke is called, caught this Anglo-French force between his own army and the garrison, who joined the attack, and utterly defeated it in a battle the people called the Fair of Lincoln. Louis, who had been besieging Dover, at once sent to France for another army. But this brought on the battle of the South Foreland, which was the ruin of his hopes.

The French commander was Eustace the Monk, a Flemish hireling who had fought first for John and then for Louis. He was good at changing sides, having changed from monk to pirate because it paid him better, and having since been always up for sale to whichever side would pay him best. But he was bold and skilful; he had a strong fleet; and both he and his followers were very keen to help Louis, who had promised them the spoils of England if they won. Luckily for England this danger brought forth her first great sea commander, Hubert de Burgh: let his name be long remembered. Hubert had stood out against Louis as firmly as he had against John, and as firmly as he was again to face another bad king, when Henry III tried to follow John's example. Hubert had refused to let Louis into Dover Castle. He had kept him out during the siege that followed. And he was now holding this key to the English Channel with the same skill and courage as was shown by the famous Dover Patrol throughout the war against the Germans.

Hubert saw at once that the best way to defend England from invasion was to defeat the enemy at sea by sailing out to meet him. This is as true today as ever. The best possible way of defending yourself always is to destroy the enemy's means of destroying you; and, with us of the British Empire, the only sure way to begin is to smash the enemy's fleet or, if it hides in port, blockade it. Hubert, of course, had trouble to persuade even the patriotic nobles that his own way was the right one; for, just as at the present day, most people knew nothing of the sea. But the men of the Cinque Ports, the five great seaports on the south-east coast of England, did know whereof they spoke when they answered Hubert's call: "If this tyrant Eustace lands he will lay the country waste. Let us therefore meet him while he is at sea."

Hubert's English fleet of forty ships sailed from Dover on the 24th of August, 1217, and steered towards Calais; for the wind was south-south-east and Hubert wished to keep the weather gage. For six hundred years to come, (that is, till, after Trafalgar, sails gave way to steam), the sea commanders who fought to win by bold attack always tried to keep the weather gage. This means that they kept on the windward side of the enemy, which gave them a great advantage, as they could then choose their own time for attacking and the best weak spot to attack, while the enemy, having the wind ahead, could not move half so fast, except when running away. Hubert de Burgh was the first commander who understood all about the weather gage and how to get it. Even the clever Eustace was taken in, for he said, "I know these clever villains want to plunder Calais. But the people there are ready for them." So he held his course to the Forelands, meaning to round into the mouth of Thames and make for London.

Then Hubert bore down. His fleet was the smaller; but as he had the weather gage he succeeded in smashing up the French rear before the rest could help it. As each English vessel ranged alongside it threw grappling irons into the enemy, who were thus held fast. The English archers hailed a storm of well aimed arrows on the French decks, which were densely crowded by the soldiers Eustace was taking over to conquer England. Then the English boarded, blinding the nearest French with lime, cutting their rigging to make their vessels helpless, and defeating the crews with great slaughter. Eustace, having lost the weather gage, with which he had started out that morning, could only bring his fleet into action bit by bit. Hubert's whole fleet fought together and won a perfect victory.

More than a century later the unhappy Hundred Years War (1336-1431) broke out. All the countries of Western Europe took a hand in it at one time or another. Scotland, which was a sort of sub-kingdom under the King of England, sided with France because she wished to be independent of England, while the smaller countries on the eastern frontier of France sided with England because they were afraid of France. But the two great opponents were always France and England. The Kings of England had come from Normandy and other parts of what is now France and what then were fiefs of the Crown of France, as Scotland was a fief of the Crown of England. They therefore took as much interest in what they held in France as in their own out-and-out Kingdom of England. Moreover, they not only wanted to keep what they had in France but to make it as independent of the French King as the Scotch King wanted to make Scotland independent of them.

In the end the best thing happened; for it was best to have both kingdoms completed in the way laid out by Nature: France, a great land-power, with a race of soldiers, having all that is France now; and England, the great sea-power, with a race of sailors, becoming one of the countries that now make up the United Kingdom of the British Isles. But it took a hundred years to get the English out of France, and much longer still to bring all parts of the British Isles under a single king.

In the fourteenth century the population of France, including all the French possessions of the English Crown, was four times the population of England. One would suppose that the French could easily have driven the English out of every part of France and have carried the war into England, as the Romans carried their war into Carthage. But English sea-power made all the difference. Sea-power not only kept Frenchmen out of England but it helped Englishmen to stay in France and win many a battle there as well. Most of the time the English fleet held the command of the sea along the French as well as along the English coast. So the English armies enjoyed the immense advantage of sea-transport over land-transport, whenever men, arms, horses, stores, food, and whatever else their armies needed could be moved by water, while the French were moving their own supplies by land with more than ten times as much trouble and delay.

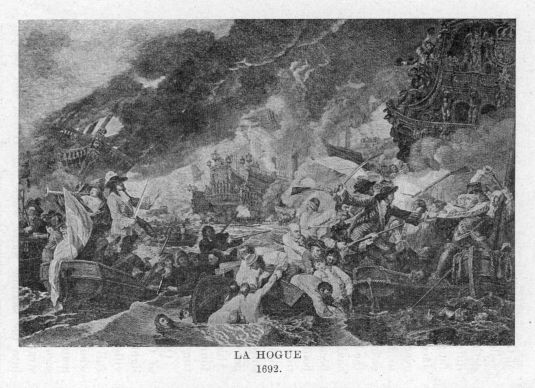

Another and most important point about the Hundred Years War is this: that it does not stand alone in history, but is only the first of the two very different kinds of Hundred Years War which France and England have fought out. The first Hundred Years War was fought to decide the absolute possession of all the lands where Frenchmen lived; and France, most happily, came out victorious. The second Hundred Years War (1689-1815) was fought to decide the command of the sea; and England won. When we reach this second Hundred Years War, and more especially when we reach that part of it which was directed by the mighty Pitt, we shall understand it as the war which made the British Empire of today.

The first big battle of the first Hundred Years War was fought in 1340 between the French and English fleets at Sluys, a little seaport up a river in the western corner of what is Holland now. King Philip of France had brought together all the ships he could, not only French ones but Flemish, with hired war galleys and their soldiers and slave oarsmen from Genoa and elsewhere. But, instead of using this fleet to attack the English, and so clear the way for an invasion of England, he let it lie alongside the mudbanks of Sluys. Edward III, the future victor of Cressy, Poitiers, and Winchelsea, did not take long to seize so good a chance. The French fleet was placed as if on purpose to ensure its own defeat; for it lay at anchor in three divisions, each division with all the vessels lashed together, and the whole three in one line with a flank to the sea. The English officers who had landed to look at it saw at once that if this flank was properly attacked it could be smashed in on the next bit of the line, and that on the next, and so on, before the remaining bits could come to the rescue. On the turn of the tide Edward swooped down with his best ships, knocked this flank to pieces, and then went on till two divisions had been rolled up in complete confusion. Then the ebb-tide set out to sea; and the Genoese of the third division mostly got away.

Ten years later (1350) the English for the first time fought a Spanish fleet and won a battle sometimes called Winchelsea and sometimes Espagnols-sur-mer or Spaniards-on-the-sea. Edward III had sworn vengeance against the Basque traders from the coast of Spain who had plundered the English vessels coming in from France. So he made ready to attack the Spanish Basques sailing home from Antwerp, where they had hired Flemings and others to join the fray. This time each fleet was eager to attack the other; and a battle royal followed. On the fine afternoon of the 28th of August King Edward sat on the deck of his flagship listening to Sir John Chandos, who was singing while the minstrels played. Beside him stood his eldest son, the famous Black Prince, then twenty years of age, and his youngest son, John of Gaunt, then only ten. Suddenly the lookout called down from the tops: "Sire, I see one, two, three, four—I see so many, so help me God, I cannot count them." Then the King called for his helmet and for wine, with which he and his knights drank to each others' health and to their joint success in the coming battle. Queen Philippa and her ladies meanwhile went into Winchelsea Abbey to pray for victory, now and then stealing out to see how their fleet was getting on.

The Spaniards made a brave show. Their fighting tops (like little bowl-shaped forts high up the masts) glinted with armed men. Their soldiers stood in gleaming armour on the decks. Long narrow flags gay with coloured crests fluttered in the breeze. The English, too, made a brave show of flags and armoured men. They had a few more vessels than the Spaniards, but of a rather smaller kind, so the two fleets were nearly even. The King steered for the Spaniards; though not so as to meet them end-for-end but at an angle. The two flagships met with a terrific crash; and the crowded main-top of the Spaniard, snapping from off the mast, went splash into the sea, carrying its little garrison down with all their warlike gear. The charging ships rebounded for a moment, and then ground against each others' sides, wrecked each others' rigging, and began the fight with showers of arrows, battering stones from aloft, and wildfire flying to and fro. The Spanish flagship was the bigger of the two, more stoutly built, and with more way on when they met; so she forged ahead a good deal damaged, while the King's ship wallowed after, leaking like a sieve. The tremendous shock of the collision had opened every seam in her hull and she began to sink. The King still wanted to follow the Spanish flagship; but his sailors, knowing this was now impossible, said: "No, Sire, your Majesty can not catch her; but we can catch another." With that they laid aboard the next one, which the king took just in time, for his own ship sank a moment after.

The Black Prince had the same good luck, just clearing the enemy's deck before his own ship sank. Strange to say, the same thing happened to Robert of Namur, a Flemish friend of Edward's, whose vessel, grappled by a bigger enemy, was sinking under him as the two were drifting side by side, when Hanekin, an officer of Robert's, climbed into the Spanish vessel by some entangled rigging and cut the ropes which held the Spanish sails. Down came the sails with a run, flopping about the Spaniards' heads; and before the confusion could be put right Robert was over the side with his men-at-arms, cutting down every Spaniard who struggled out of the mess. The Basques and Spaniards fought most bravely. But the chief reason why they were beaten hand-to-hand was because the English archers, trained to shooting from their boyhood up, had killed and wounded so many of them before the vessels closed.

The English won a great victory. But it was by no means complete, partly because the Spanish fleet was too strong to be finished off, and partly because the English and their Flemish friends wanted to get home with their booty. Time out of mind, and for at least three centuries to come, fleets were mostly made up of vessels only brought together for each battle or campaign; and even the King's vessels were expected to make what they could out of loot.

With the sea roads open to the English and mostly closed to the French and Scots the English armies did as well on land as the navy did at sea. Four years before this first great battle with the Spaniards the English armies had won from the French at Cressy and from the Scots at Neville's Cross. Six years after the Spanish fight they won from the French again at Poitiers. But in 1374 Edward III, worn out by trying to hold his lands in France, had been forced to neglect his navy; while Jean de Vienne, founder of the regular French Navy, was building first-class men-of-war at Rouen, where, five hundred years later, a British base was formed to supply the British army during the Great War.

With Shakespeare's kingly hero, Henry V, the fortunes of the English armies in France revived. In 1415 he won a great battle at Agincourt, a place, like Cressy, within a day's march of his ships in the Channel. Harfleur, at the mouth of the Seine, had been Henry's base for the Agincourt campaign. So the French were very keen to get it back, while the English were equally keen to keep it. Henry sent over a great fleet under the Duke of Bedford. The French, though their fleet was the smaller of the two, attacked with the utmost gallantry, but were beaten back with great loss. Their Genoese hirelings fought well at the beginning, but made off towards the end. In 1417 Henry himself was back in France with his army. But he knew what sea-power meant, and how foolish it was to land without making sure that the seaways were quite safe behind him. So he first sent a fleet to make sure, and then he crossed his army, which now had a safe "line of communication," through its base in France, with its great home base in England.

Henry V was not, of course, the only man in England who then understood sea-power. For in 1416, exactly five hundred years before Jellicoe's victory of Jutland, Henry's Parliament passed a resolution in which you still can read these words: "that the Navy is the chief support of the wealth, the business, and the whole prosperity of England." Some years later Hungerford, one of Henry's admirals, wrote a Book of English Policy, "exhorting all England to keep the sea" and explaining what Edward III had meant by stamping a ship on the gold coins called nobles: "Four things our noble showeth unto me: King, ship, and sword, and power of the sea." These are themselves but repetitions of Offa's good advice, given more than six centuries earlier: "He who would be safe on land must be supreme at sea." And all show the same kind of first-rate sea-sense that is shown by the "Articles of War" which are still read out to every crew in the Navy. The Preamble or preface to these Articles really comes to this: "It is upon the Navy that, under the providence of God, the wealth, prosperity, and peace of the British Empire chiefly depend."

Between the death of Henry V in 1422 and the accession of Henry VII in 1485 there was a dreary time on land and sea. The King of England lost the last of his possessions in the land of France. Only the Channel Islands remained British, as they do still. At home the Normans had settled down with the descendants of the other Norsemen to form one people, the Anglo-Norman people of today, the leading race within the British Empire and, to a less extent, within the United States. But England was torn in two by the Wars of the Roses, in which the great lords and their followers fought about the succession to the throne, each party wanting to have a king of its own choice. For the most part, however, the towns and seaports kept out of these selfish party wars and attended to their growing business instead. And when Henry VII united both the warring parties, and these with the rest of England, he helped to lay the sure foundations of the future British Empire.

England needed good pilots to take the ship of state safely through the troubled waters of the wonderful sixteenth century, and she found them in the three great Royal Tudors: Henry VII (1485-1509), Henry VIII (1509-1547), and Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603). All three fostered English sea-power, both for trade and war, and helped to start the modern Royal Navy on a career of world-wide victory such as no other fighting service has ever equalled, not even the Roman Army in the palmy days of Rome. It was a happy thought that gave the name of Queen Elizabeth to the flagship on board of which the British Commander-in-chief received the surrender of the German Fleet. Ten generations had passed away between this surrender in 1918 and the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. But the British Royal Navy was still the same: in sea-sense, spirit, training, and surpassing skill.

Henry VII was himself an oversea trader, and a very good one too. He built ships and let them out to traders at a handsome profit for himself besides trading with them on his own account. But he was never so foolish as to think that peaceful trade could go on without a fighting navy to protect it. So he built men-of-war; though he used these for trade as well. Men-of-war built specially for fighting were of course much better in a battle than any mere merchantman could be. But in those days, and for some time after, merchantmen went about well armed and often joined the king's ships of the Royal Navy during war, as many of them did against the Germans in our own day.

English oversea trade was carried on with the whole of Europe, with Asia Minor, and with the North of Africa. Canyng, a merchant prince of Bristol, employed a hundred shipwrights and eight hundred seamen. He sent his ships to Iceland, the Baltic, and all through the Mediterranean. But the London merchants were more important still; and the king was the most important man of all. He had his watchful eye on the fishing fleet of Iceland, which was then as important as the fleet of Newfoundland became later on. He watched the Baltic trade in timber and the Flanders trade in wool. He watched the Hansa Towns of northern Germany, then second only to Venice itself as the greatest trading centre of the world. And he had his English consuls in Italy as early as 1485, the first year of his reign.