This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Into the Jaws of Death

Author: Jack O'Brien

Release Date: August 2, 2006 [eBook #18963]

Last updated: May 26, 2013

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INTO THE JAWS OF DEATH***

Having been asked by the Author of this Book, No. 73,194 Private Jack O'Brien of the 28th Northwest Battalion, to write a few words as an introduction to the story which he is placing before the public, it gives me much pleasure to do so.

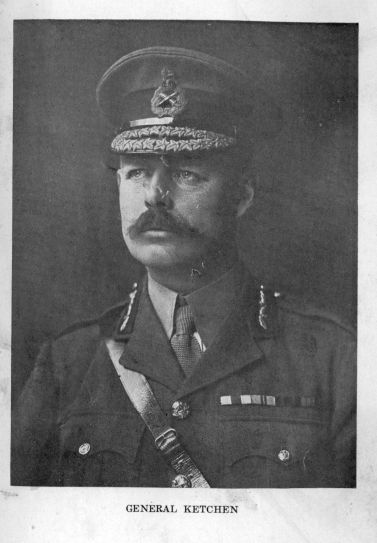

The 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade raised and organized from the four western provinces of Canada has done its share and at the time of writing it is still doing its share in the field against the common enemy. The 28th Northwest Battalion, originally under the Command of Lieut.-Col. J. F. L. Embury, C.M.G., has taken its share in all the engagements in which the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade took part, including St. …loi, Hooge, three engagements on the Somme, 15th September, 26th September, and 1st October, 1916, as well as the general engagements of Vimy Ridge, Fresnoy, Lens on the 21st August, 1917, and Passchendaele, and in each of these engagements, alongside the remaining Battalions of the Brigade—namely, the 27th City of Winnipeg Battalion, 29th Vancouver Battalion, and the 31st Alberta Battalion—never failed in gaining all of the objectives which had been set for the Brigade to carry. Whenever any special raids to obtain information and identifications were called for, the 28th Northwest Battalion invariably volunteered for such duty, and their efforts were always crowned with success. In fact the record of the Brigade throughout the campaign has been an outstanding one, and the various matters which Private Jack O'Brien refers to in his book will be of the greatest interest to all members of the Brigade, past and present, as well as to the general public in Western Canada.

The feat accomplished by this young soldier in escaping from the Germans, whilst held as a prisoner of war, is in itself worthy of special notice and he was only successful in his third attempt. His conduct and record in the field is one to be proud of, and I have no hesitation in introducing him to the readers of his most interesting book. As a soldier he has done his duty and is deserving of every support in the circulation of his war story.

H. D. B. KETCHEN,

Brig.-Gen. comm'd'g 6th Can. Inf. Brig.

10th April, 1918

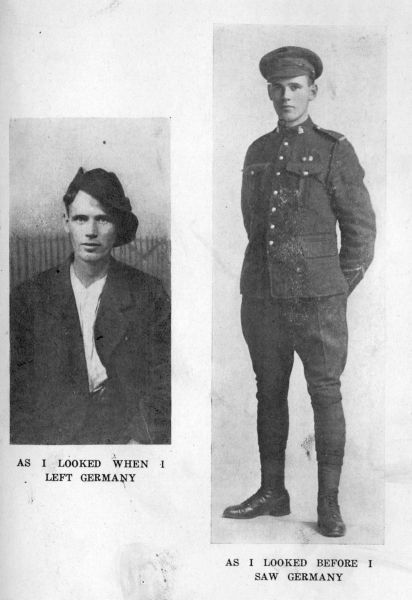

"Well, boy, how did you do it?" "What are the prison camps like?" "Are the Germans as cruel as they are painted?" These are the questions that I have been asked thousands of times since coming home. I have answered them from scores of platforms, for all kinds of Red Cross organizations; and now I have been persuaded to try and put my answer on paper—and if when I have finished, there are a few points cleared up that you have been wondering, and perhaps worrying about, I shall feel repaid for the writing. They say that "the pen is mightier than the sword," but my experiences of the last ten years have given me much more practice with the latter than with the former. I shall not attempt a flowery story, nor exaggerate anything to make it sound big, but I shall, as they say in the Court, tell "the truth, and nothing but the truth."

My story begins when this war broke out in August, 1914. I was working with a survey party at the time not far from Fernie, British. Columbia. I remember the day that I made up my mind to enlist. I had just decided the question when along came my chum Stevens, and I said, "Well, I'm jumping the job this morning, Steve." He said, "Why? What the devil is eating you now? Don't you know when you are well off?" I said, "Yes, Steve, I do; but it is like this—ever since you and I went to town the other day I have been thinking this thing over." "Thinking what?" "Why, about the war, of course—I can't get it out of my head. There is going to be the devil of a scrap over there—and say, boy! I've got to get into it! When I hear of what Germany is doing to poor little Belgium it makes my blood boil—I have worked with the Germans, and I have a little idea of what it would mean to turn the world over to them—so I'm off to draw my time." Well, when I came back from the boss's cabin, I found Steve packing up, and I said, "Why, what's the matter, Steve?" He said, "Oh hell! if you're going, I'm going too;" so we started off together.

We had a twelve-mile hike to the nearest town, and that night we took the train for Winnipeg. We stayed off in Moose Jaw to see some boys that we knew, and of course we told them that we were on our way to enlist. To our surprise we found that they were planning to join a company that was being recruited in Moose Jaw, and they urged us to sign up with them. We thought it would be nice to be with some one we knew, so one morning we lined up with three or four hundred others to be examined for the Army. They had room for only two hundred and fifty men, and as we stood in line we looked around to size up the bunch and see what our chances were for getting in. They were a husky-looking lot, and all were eager to go. I remember one big fellow near the end of the line offered me five dollars for my place. I said, "Go to hell with your five dollars." Afterwards in the trenches, when we were knee-deep in mud and the big shells were bursting around us, he could have had my place and welcome. Well, we were all taken on, and we got our first taste of drilling and marching. For about a week we were marched around the streets of Moose Jaw—flags were flying—bands playing—and we were the centre of interest. The last night we were there, the city tendered us a banquet and an old South African veteran gave us a farewell speech. Among other things, he said, "Well, boys, you belong to the Army now [they didn't let us forget it very long]. The first thing you must learn is discipline," and he gave us a long speech on that. Then he went on: "The next thing is cleanliness. I suppose you have been taught as I was that 'cleanliness is next to godliness'; but in the Army you will find that it works pretty much the other way—godliness is next to cleanliness." This is all I remember of the old soldier's speech, and afterwards, believe me, I found that he was right; in the trenches cleanliness is quite as difficult as godliness.

Well, early next morning we took the train for Winnipeg, and there was a big crowd to see us off, for most of the boys who had joined up had their homes in Moose Jaw. I didn't know any one, and I was not paying much attention to the crowd when a funny thing happened. I was feeling a bit lonely seeing all the other boys being made a fuss over, when suddenly a nice-looking young girl loomed up in front of me, and a joyful voice said, "Why, Harry, here you are; I have been looking all over for you." Now, my name was not Harry, but when she lifted her face to be kissed, why I tried to do as the real Harry would have done. Perhaps I did not succeed, for somehow she realized her mistake and she did not seem half as well pleased over it as I was. Finally the train pulled out amid the cheers of the crowd, and the boys who were leaving home and friends looked just a wee bit quiet and sad, but soon they recovered their spirits, and we had a jolly time playing cards and getting acquainted. They were all strangers to me, and we were destined to go through experiences that drew us closer together than brothers, but I didn't know it then, so I sat there and tried to imagine what they were like, and the opinions I formed were far from right in the light of events that followed. I have learned now how foolish it is to judge a man by his appearance. It was only a twelve-hour trip to Winnipeg, and when we got there we found a band to meet us. We were marched through the streets, and though we stuck out our chests and tried to remember all that had been told us about marching, I fear we made a poor impression. We still wore our ordinary clothes and only the badges on our arms marked us as would-be soldiers.

After about an hour's march we were taken to a large frame barrack known as the Horse Show Building. This place had been built for a skating rink and was never intended as a dwelling-place for men. In the winter the water poured from the frost-lined roof, and for a long time we had no floor. We slept on ticks filled with straw, and these were soaked every day—we were almost drowned out. There was an old piano in the building, and every morning we were awakened by a wag in the crowd playing "Pull for the shore, sailor." The boys would all take it up, and in a few minutes every one would be singing at the top of their voices. This put us in good humour for the day.

We were not the only ones in the building; other companies had come in from the West, and when our numbers had reached the 1,100 mark we were formed into what was known as the 28th Northwest Battalion.

Now, it is not my intention to give a detailed account of our training. We were like every other new battalion, perfectly green in the art of soldiering, awkward in the use of our hands and feet, but strong in our determination to make good as a battalion. Especially were we anxious to please our commanding officer. Just to give you an idea of how green I was, let me tell you of my first meeting with our O. C., Colonel Embury. I was lounging around the guardroom one day when the Sergeant asked me to take some papers to the Orderly Sergeant upstairs. Now, my tunic was unfastened, my belt loose, and my cap on the back of my head, but it never occurred to me to fix myself before going up. I took the papers and went up three steps at a time. When I reached the orderly-room I walked in, and said, "Who is the Orderly Sergeant here?" A voice from the corner of the room said, "Here, lad," and I started in his direction when another voice spoke up and said, "Look here, sonny—" I turned around and found myself looking into the genial fatherly face of Colonel Embury. I was too much surprised and dismayed to even attempt a salute, and the Colonel, instead of calling me down, just smiled and said: "Young man, supposing you go out into the hall, fasten up your tunic, tighten your belt, and put your cap on properly; then come to the door and knock. When you get an answer, walk in and salute, and see how much smarter and better it will look." You bet I felt cheap, and almost any sized hole would have been large enough for me just then. But I went out and did as I was told, and when I came back he answered my salute and smilingly said, "Now, that is fine," and went on with his work. What wouldn't a boy do for an officer who used him like that?

It was hard for us boys who had been on our own hook for several years to get used to the discipline of the Army. We were used to doing exactly as we liked, and the unquestioning obedience demanded did not come easy. Gee, but it used to hurt to take a "call-down" from a petty officer without having a chance to reply or even to show what we felt in our faces, and when he had said everything he could think of we had to touch our cap and say "Yes, Sir!" I assure you, very often we felt like saying something entirely different.

Training in the open with the thermometer ranging anywhere between 25 and 40 below zero is no fun. We were taught to shoot, march, skirmish and drill, and we also learned the art of "old soldiering," which means the art of being able to dodge anything in the shape of work. By the way, they have a fancy name for work in the Army—they call it "Fatigue," but when you come to do it it's just the same as the common variety spelled with four letters. We did not get meals at barracks, but took them in a restaurant downtown—and rising at 6 A.M. on a bitterly cold winter's morning and having to walk a mile to breakfast was not always pleasant. Sometimes we would break away and take a streetcar, till an order was issued forbidding our doing it. However, one very cold morning following a heavy fall of snow we plodded our way downtown; our new uniforms with their unlined greatcoats (minus the cozy fur collars such as civilians wore) did not keep out more than a quarter of the cold, the rest went through us. Our caps were wedge-shaped affairs of imitation black fur, and on mild days we felt very smart in them, but when it was forty below and Jack Frost was on a still hunt for every exposed portion of our body, a cap that would not be coaxed down to meet our collars was a fit object for our worst language.

Well, on this particular morning every one got half frozen going down, and after breakfast no one felt like walking home. About half of the boys "fell out" and took the street-car. I got on a car that was pretty well filled with our lads, and we were having a jolly time when the car stopped and in walked our O. C. Several of the boys jumped up to offer their seat, but the Colonel smiled and said, "Never mind, boys," and continued to stand at the back of the car. We were pretty quiet, for we hated to be caught disobeying orders, and especially did we hate being found out by our O. C. Well, he got off the car before we did, and we did not see him again till the next parade. Then when we were lined up Colonel Embury read out the rule forbidding us to break ranks—we were wondering how many days C. B. we would get—when the O. C. looked around with a smile and said, "Well, boys, I'll let you off this time, I didn't feel much like walking myself." One of the boys dug me in the ribs and whispered, "Some scout, eh?" It was little things like this that won the hearts of "his boys," as he always called us, and so far from spoiling discipline it made us put up with any discomforts for the sake of pleasing him.

But before going any farther I wish to explain what C. B. means. It is the favourite mode of punishment in the Army and is served out for almost all offences or "crimes," as they are called—the only variation being in the length of time given. "C. B." is "confined to barracks" and having to answer a bugle call every half-hour, after the battalion is dismissed. The object of answering this bugle call is to let the powers that be know that you are still there. In the Army it is known as "Defaulters," but we named it the "Angel Call." There was usually one or more of our little circle answering it, and the favourite crimes were smoking on parade, staying out without a pass, coming home "oiled," and staying in bed after reveille in the morning; the last-named was a favourite one of mine, and I escaped punishment for quite a while, but the old saying "The pitcher that goes oft to the well is sure to get broken at last" was true in my case. I had formed the habit of lying in bed and reading the paper for about half an hour after reveille, and it always made the Sergeant mad. However, so far he had not reported me; but this morning, after about twenty-five minutes of stolen comfort, the Sergeant said, "Now, look here, O'Brien, if you are not out of bed in three minutes I'll have you up before the Major." I looked, listened, and pulling out my watch continued reading. Exactly on the three minutes I jumped out, but the boys were all laughing and the Sergeant got mad and had me "pinched"; so at 9 a.m. I was brought up on the "carpet" before the Major. I was looking the picture of innocence, and I had a chum outside to prove that I was out of bed three minutes after the Sergeant's warning. Well, the Sergeant didn't press the charge very much, and the Major asked me how long it was after reveille when I got up. I said it was five minutes anyway, and I had them arguing whether it was five or ten minutes (it was really half an hour), when the officer said, "O'Brien, have you any witnesses?" I said, "Yes, Sir, Private Gammon." Officer: "Private Gammon, step forward. How long after reveille did O'Brien lie in bed?" "Fifteen minutes, Sir," said Gammon, and looked at me as though he were doing me a great favour. "Five days C. B.," said the Major; "right about turn, dismiss." Now, believe me, what I said to that boy wouldn't look well in print. No more "witnesses" for me—like the darky who was brought up before the judge for stealing chickens. He protested his innocence, and the judge said, "Pete, have you any witnesses?" The old man answered, "No, Sir, I never steals chickens 'fore witnesses." In the future I would follow my old schoolmaster's advice; he said, "My boy, never tell a lie; but if you do happen to tell one, make it a good one and stick to it." I haven't always been able to live up to the first part, but when I fell down on that the latter half came in handy. This was my first crime, but it wasn't by any means my last. I remember one day in the early spring the battalion was out doing some skirmishing, and somehow three of us got separated from the others. In looking for our company we came across an inviting-looking spot, and we sat down to have a rest. Smoking and telling stories made the time pass quickly, and when we came to look for the battalion it had gone home. We hiked for home as fast as our legs could carry us and got in about an hour late. Next morning we were paraded before the Major, and he listened to our story but evidently didn't sympathize with our love for nature and gave us seven days C. B. I thought the punishment rather stiff, but the old Major had it in for me. A few days before, when we were on parade, the old Major kept our platoon drilling after the others had gone in, and all the boys were sore. He gave us an order, and one of the boys near me said in a loud undertone, "Go to hell, you spindle-legged old crow." The Major heard it; he turned quickly and looked in our direction and caught me laughing, so he felt pretty sure that it was I who had made the remark; so when he got a chance to get even, he soaked it to me.

However, two can play at that game, and my chance came a few nights later; I was on sentry duty and the old Major was acting as orderly officer. He was always spying on us boys, and about 2 A.M. on the coldest nights he would make the round of the guards to be sure that we were all at our posts. This was not done by the other officers, and naturally we resented it, so when the boy on the next beat gave me the tip that the old boy was coming I stood in close to the wall and waited—as he turned the corner, stealing along like a cat, I sprang out with my bayonet at his chest, and in a voice loud enough to be heard ten blocks away shouted "Halt!" Old "Spindle-legs" threw up his hands, gasped like a fish, and it seemed half a minute before he whispered "Orderly officer." Of course I lowered my rifle with a fine show of respect, but he didn't lose any time asking what my orders were for the night; he beat it for the orderly-room as fast as his trembling legs could carry him. He took it for granted that we were very much on guard. The other guard and I almost had a fit laughing, and it was as much as we could do to face him next day.

Little things like this relieved the monotony of the days that otherwise were very much alike. We were drilled into shape and finally we came to take pleasure in doing things in the sharp brisk manner they required and in making as good a showing as possible—everything was for the honour of the battalion, and woe betide any one who was slovenly in his dress or who bungled his marching.

But we would have had a pretty lonely winter if it had not been for the great kindness shown us by some of the Winnipeg churches and also by individual ladies. Chief among these, I would like to take the liberty of mentioning Lady Nanton; she was the guardian angel of the 28th; the billiard room of her beautiful home was thrown open for our use every night in the week and a lunch was served to as many boys as cared to go. It was through the efforts of Lady Nanton that a smoking-room was erected for our benefit, for we were not allowed to smoke in barracks. I received parcels from her when I was a prisoner of war in Germany, and I leave you to imagine how much they were appreciated then; and now that the 28th boys are coming back wounded and broken in health it is Lady Nanton that still acts as guardian angel and gets everything possible for them.

But to go back to my story. We had been in training for about six months and the Army life had done a great deal for us. The city was full of soldiers; new battalions were being formed all the time, and we felt quite like old veterans. We were "fed up" with marching around the city on parade, and we longed to get into the real fighting. For my part, I was heartily sick of the whole thing, and all that made it bearable was the close friendship I had formed with some of the boys in my platoon; about a dozen of them were my close friends. I shall name a few of these, so that you may recognize them when they appear farther on in my story; there were "Bink," Steve, Mac, Bob, Tom, Jack, Scottie, and also our "dear old Chappie"; the last-named was one of those quiet-going Englishmen who always mean what they say and who invariably addressed every one as "my deah chappie," but he was a good old scout and everybody liked him. Our Sergeant, known among the boys as "Yap," is another interesting character; his heart was the biggest thing about him and his voice came next. If he wanted you to do anything he spoke loud enough to be heard a mile away; if you didn't do as he ordered, you could never bring in the excuse of not having heard. Then there was our Corporal, who got the name of "Barbed-wire Pete," so called because when the order came to grow moustaches his attempt looked like a barbed-wire entanglement. Now for our Lance Corporal, who when he got to France was known as "Flare-pistol Bill." He early developed a mania for shooting up flares in the front-line trench at night. We had two Yankees in our bunch—"Uncle Sam," who was the oldest man in the platoon, and "Baldy," who only wore a fringe of hair. One day in the trenches one of the boys noticed Baldy scratching his head on a spot where there was still a little hair, and he said, "Hey, Baldy, chase him out into the open; you'll have a better chance to catch him there." Now, I realize that this bunch of boys may sound very commonplace to the average reader, but we went through more than one hell together and I found them white clear through, and heroes every one of them. They included farmers, firemen, business men, university men, hoboes, and socialists. Some mixture!—but it was out of this kind of stuff that our Canadian Army was made, and I am not ashamed of their record.

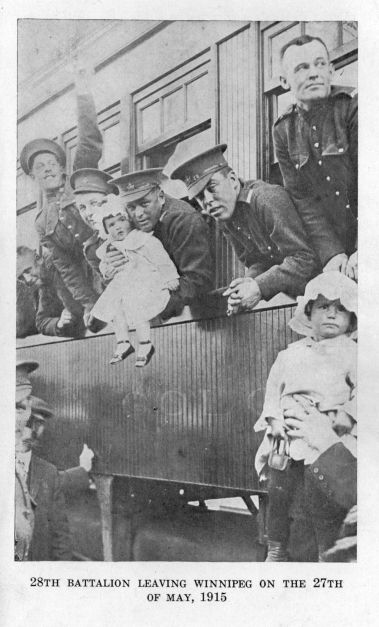

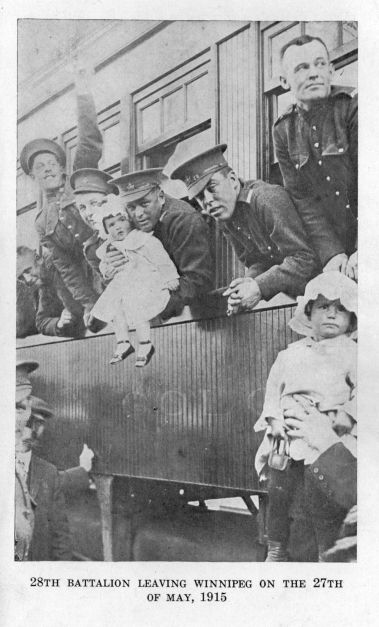

Now that I have introduced you to some of my friends, I will go back to the time when we left Winnipeg. After many false rumours, at last the day came when we were to start. On the 26th of May, 1915, the order came out that we were to entrain the following morning—we were all confined to barracks and every one was crazy with joy—we hurried through our packing, then we sat around all night, singing, telling yarns, and trying to put in the time till morning. Early next day we were marched to the station, and though for obvious reasons our going had not been advertised, hundreds of friends were there to see us off. They loaded us with candy, fruit, smokes, and magazines, and I don't think a happier bunch ever left Winnipeg. The train trip was very uneventful. We ate and played cards most of the day. This was varied by an occasional route march around some town on the way. When we reached Montreal we were reviewed by the Duke of Connaught, and as soon as this was over they marched us down to our boat. After locating our berths we thought we had nothing to do but go out and do the city. My chum and I made our way down to the gangway and there found our way barred by a sentry who said, "Nobody allowed off the ship." We were terribly disappointed, but we had learned not "to reason why" in the Army, so we went to the other end of the ship. Here we found another boat drawn up alongside, and as there was no one in sight we boarded her. From here we had no trouble getting ashore, and away we went uptown—"stolen pleasure is the sweetest kind"—and we had no end of a time for a few hours. We hiked back and got to the ship just in time to turn in with the other boys; no one had missed us for a wonder, and everything was all right. Next morning we awoke to find ourselves slipping down the broad St. Lawrence. Our voyage lasted ten days, and it sure was "some" trip. The weather was perfect and we had all kinds of sport, wrestling, boxing, and everything that could be done in a limited space. The regimental band of the 28th was something that we were justly proud of, and they supplied the music for our concerts and dances—yes, we did have dances, even though there were no ladies present—half of the fellows tied handkerchiefs on their sleeves and took the ladies' part; their attempts at being ladylike and acting coy were very laughable. The only thing that really marred our pleasure was the lifeboat drill; any hour of the day or night when the signal was given, no matter what we were doing, we must grab our life-belt and make all possible speed to our place at the lifeboats. At first it was great fun, but soon we grew to hate it, and we almost wished the ship would be torpedoed just to make a change. The last three days of our trip we were in the "Danger Zone," and at night all lights were put out and as many men as possible slept on deck; machine guns were posted and men on duty at them all the time. The sentries had orders to shoot any one that showed a light. We were obliged to wear our life-belts night and day, and if I looked as funny to the others as they did to me, I don't see how they ever got their faces straight. Most of our waking hours were spent in looking for "subs," and every one that saw a bottle or stock on the water was sure he had sighted a periscope. One night as I was sleeping on deck I was awakened by having a great light flashed in my face—I jumped up in a hurry and to my amazement I found two great searchlights sweeping our ship from stern to stern—and immediately, out of the darkness, two destroyers, slim and grey, came racing up, one on either side of us. They gave us our first glimpse of Britain's sea power, and we felt a wonderful sense of security. In the morning we had a good look at the destroyers, for they were quite close and they kept just abreast of us—every now and then they would put on speed and rush ahead leaving us as if we were standing still—then they would turn almost in their own length and come rushing back, sometimes circling the ship two or three times. They reminded me of a couple of puppies gambolling and trying to coax the old dog into the game.

We proceeded this way till we hit the Channel, and soon we caught our first glimpse of the shores of England (or "Blighty," as the soldiers call it). The green hills sure did look good to us after gazing at water for ten days. We also passed a big wooden ship built in the time of Nelson that is being used as a training-ship for cadets—as we steamed slowly by, hundreds of the cadets were clustered on the masts and rigging, and they gave us a great burst of cheers. It was our first welcome to the old land. That night we slipped slowly into port, and again we caught a glimpse of Britain at war; big searchlights glaring out to sea, crossing and recrossing, searching—searching all the time. Big ships were going to and fro with coloured lights to show their identity. We stayed on the ship all night, but most of us were too excited to get any sleep. Next morning we were taken off and put aboard a dinky little train. The locomotives and coaches looked so small in comparison with the big American trans-continental trains that the Englishmen in our outfit came in for lots of chaff. "Baldy," the American, would say to Bob Goddard, "Do you call this miniature thing a railroad? Why, at home we have trains as big as this running up and down the floors of our restaurants carrying flapjacks." Of course every one roared at this, and Bob said, "Never mind, you can laugh now, but wait till we start and see the speed we have." They argued on this for a while, and then Bob said, "Why, the locomotives over here pick up water on the fly." "Aw, that's nothing," said Baldy; "they pick up hoboes on the fly in the States." Bob had nothing to say to this, and conversation lagged for a while. Some time later Bob called our attention to the really lovely scenery we were passing through. Said he, "Look at those lovely old trees with the creepers on them; where in the States would you find anything to compare with them?" But Baldy was ready, "Aw, I can see you were never in a lumber camp." "What difference does that make?" says Bob. "All the difference in the world," answered Baldy; "if you were ever in a lumber camp, you'd know without my telling you that we have men there with creepers on them." This was too much for Bob, and he quit;—we played cards the rest of the way to London, but when we reached it we became interested again in the outside world. London was a place we had all heard of, but few of us had seen. Bob was nearly crazy, for we passed in sight of his home. Of course he had been away for several years, but his people still lived there; it sure was hard for him to be so near and not be able to stop and see them. He showed us all the points of interest that were in sight; but our first impression of London was rather disappointing, for we were either going through suburbs or smoky tunnels. We went through some crowded districts, and the people all ran out and cheered us as we passed. England was going wild over Canadians then, for it was just after the Second Battle of Ypres, where our boys had made such a name for themselves. On one street there were about five hundred kids, and Baldy remarked, "No race suicide here."

Pretty soon we left London and we all went back into the train. There was great speculation as to what camp we were bound for, but no one knew, and when at last the train came to a halt we were glad to get off and stretch our legs,—we stretched them a whole lot more than we intended before the night was out,—for we had to hike about four miles with full pack and then climb a long steep hill. We had nothing to eat all day and we were just like ravening wolves, but after we reached camp we had to wait for the cooks to prepare some "mulligan" (stewed beef) and tea; then we were lined up and bundled into our tents, about ten men in each. Next morning some of us were sent down to unload the transport and the rest were put to work setting things to rights at the camp. I was with those that went down to the depot, and here the battalion suffered its first casualty—the pet of the whole regiment was lying dead in the box-car—and though to an outsider he was only a bulldog, to us he was our beloved "Sandy," the mascot of our battalion. He had shared all our route marches, no matter what the weather, and as I saw him lying there I thought of the fun we used to have with him. Scores of times I have seen him, when the bugle sounded for us to fall in, go and take his little blanket from the low nail where it always hung, and beg one of the boys to put it on for him. He would wag himself almost to pieces trying to attract attention, and of course the boy wouldn't let on to notice him; so he would go from one to the other, till at last some one's good nature overcame the desire for further sport, and his blanket was fastened on. Then, with a glad bark, he would dash out and take his place at the head of the battalion. He knew the other bugle calls too, and the call to mess was answered by mad jumping and much showing of teeth. He responded with the officers to the Colonel's Parade, and as the officers formed a circle round Colonel Embury to receive their orders for the day, it was funny to see old Sandy right in the centre gazing up into the Colonel's face. Our O. C. loved him and always gave him his share of attention after the officers were dismissed—it was our Colonel who insisted on Sandy having his own bunk and blankets just like any of the men—so, after being such a pet, you can imagine how we felt when we saw him lying there dead, and we realized that we were to blame for his death. All dogs entering England have to spend several weeks in quarantine, and to save him from this some of the boys had boxed him up and placed him in the baggage car, but whoever had done the job was not careful to place him right side up, and when we opened the box poor old Sandy was lying on his back dead. The whole battalion mourned his loss, and our Colonel most of all. Well, after we got everything loaded up, we went back to camp, and there we found the boys as busy as bees—we were telling them about Sandy when suddenly we heard a humming sound—every one gazed skyward, and across the camp flew one of the British dirigibles. What a sight it was to us! The big cigar-shaped, silver-coloured airship dipped and climbed, and finally came down so low that we could plainly see the men in it. You should have heard the cheer we gave them. We watched it till it disappeared out across the sea. After awhile we got used to seeing airships of all kinds and we took no notice of them, but at first they were very interesting.

Another thing that happened on our first day in camp (by the way, we were quartered in Shorncliffe, right on the seacoast)—a few of us were standing looking across the Channel to France, and wondering what was happening there, when boom-boom-boom! we heard the guns in Belgium. We could hardly believe our ears. I don't know about the other fellows, but it sent a queer feeling through me to know that only fifty or sixty miles away our boys were fighting and dying. Before this the war had seemed very unreal, but the sound of the guns made me realize that it was a grim reality, and I wondered how I would face it when the time came.

Well, the next few days saw us settled in camp and then our training commenced in real earnest. We thought the six months' training in Canada had made us hard, but what we went through for the next two months made us like nails. We had shooting, skirmishing, night marches, trench-digging, besides all the special courses. Three other battalions were in the same camp—the 27th from Winnipeg, 31st from Calgary, and the 29th from Vancouver—and the four of us were formed into what was called the "Sixth Brigade"; after the Battle of St. …loi they were known as the "Iron Sixth." The only thing we objected to in the training was the length of time it took. It seemed as hard to get to France as it had been to get to England. We didn't eat from tables as we had in Canada, but each of us was provided with exactly the same equipment as they have in France,—namely, a mess tin. When the meal was called we would all line up, and meat and potatoes and everything would be dished into our can; then we would hike off to our tents and eat it sitting on the ground. Each day an orderly officer went the rounds to ask if there were any complaints, the usual procedure being to stick his head in the tent flap and say, "Any complaints, boys?" and walk on without waiting for an answer. One day he came to our tent and standing in the tent door asked the usual question. One of the boys was a college-bred Englishman, and he spoke up and said, "Oh, I say, old chap, there's no complaint, but, deah boy, I wish you would take your foot out of my mess tin—you are spoiling all my dinnah." The officer and the boys just roared. I suppose most of us compared it with the picturesque language we would have made use of.

Bob went home on leave about this time, and while in London he ran across an old schoolmate of his who was also home on leave. The lad's name was Harold Rust. He had spent several years in Canada, but happened to be in England when the war broke out and he had joined up with a London regiment. He had been one of Kitchener's "Contemptible Little Army" and had seen considerable service in France—he had been wounded and at the time Bob met him was home on sick leave—but he had been in America too long to enjoy the discipline of the British Army, and as he said himself he was "fed up" with it. So he asked Bob if there was any chance of getting into our brigade. He had tried several times to get a transfer into the Canadians, but each time he was turned down, so he said if Bob could get him in he would desert his own regiment and so save all the trouble of a transfer. Bob told him to send in an application to our Colonel, and shortly after Bob returned Colonel Embury sent for him. He said: "Goddard, I have here a letter from a man in London; he says he is a Canadian, and as all his chums are here, he wants to join the 28th. Do you know him?" "Yes, Sir, I knew him in Winnipeg," says Master Bob. "Well," said the Colonel, "we are one or two under strength, so I'll see what I can do." Bob came back tickled to death and told Tommy, Bink, and me all about it. If he got in we saw where we would have no end of fun having a fellow with us who had seen service in France and no one knowing it but ourselves. Well, a few nights later we were sitting in our tent foot-sore and dog-tired after an all-day route march when in walks Rust. Bob jumped up and made the introduction; he had been sent for to come down and take his medical examination. We wondered how he would ever get through without the Doctor seeing his wounds, but when he came up for his examination he got through by keeping his hand over the old scar. Next day he was attested, put into uniform, and then he was given leave to go home and fix up his business affairs. This is what he did—he changed on the train from khaki into civies, went home, put on his Imperial uniform, and went up to draw his regimental pay. He drew all that was coming to him, and tried to get an advance but failed. Then he went home, changed into his Canadian uniform, and leaving his other in a bundle, he came away without even letting his father know where he was going. He came down to Shorncliffe and we got him into our platoon and into our tent, and then the fun started. The boys thought him a greenhorn, and they were all showing him how to do things. He would let them help to put his puttees on, show him the hundred and one things that a soldier needs to know; we would almost burst trying to keep from laughing. When we were out drilling, he was just as clumsy as though he had never held a rifle—after him meeting the Germans in the open and firing till his rifle jammed. The Sergeant would take him out and give him private lessons, showing him how to slope arms and present arms, and all the time Rust was looking innocent and acting as awkward as the greenest of the green. Those of us who knew nearly killed ourselves laughing. Then they gave him another leave, and we didn't see any more of him till we were ready to leave for France.

Leave to London was very hard to get, and of course we were all crazy to go there; but we were all allowed late leave on Sundays, and of course we always had our Saturday afternoons, so if we could dodge the military police we took the train at noon on Saturday and spent Sunday in London. There was an early morning train which got us in before reveille on Monday. We worked this successfully several times, but one Sunday almost our whole platoon was in London, and as luck would have it we all missed the early tram. When our platoon lined up there were only ten present, and of course this gave the whole thing away. We arrived on the noon train and we sure did get a calling down—of course we were forbidden to do it again. However, before going to France each of us had a week in London, and that wonderful old city was surely an eye-opener to us Western boys. In fact, England itself is like a big garden; and so beautiful that it's little wonder that its people would fight to the last man to save it. We had only been in England a short time when they started giving instruction in special courses, such as bombing, signalling, and machine gun work. Any one who took one of these courses was exempt from all fatigue duty, and they did not report so early in the morning. Steve and I joined the bombers, known in France as the "Suicide Club," and Bob, with two or three others, took up the machine gun work. I found the bomb throwing very interesting, and in our six weeks' course we learned to handle the "Mills" bomb, "hair-brush," and the "jam tin." There was just enough danger in it to make it exciting and there was some sport as well. For instance, the "jam tin" bomb is a real jam tin packed with explosive, and we had to make as well as throw them, and for practice we were allowed to bomb the trenches dug by our battalion. They would spend two or three weeks digging and fixing up a nice trench and then along would come the bombers and blow it all to smithereens—no wonder the boys were sore at us; but then, they were getting practice, and we were only doing what "Fritzie" would do for them later on. Steve and I stuck with the bombers, but one morning as I watched our battalion line up I was surprised to see Bob and his pals in the ranks. When we met that night I asked him why he had given up the machine gun work, and I sure did laugh at what he told me. He said: "Aw, I liked the work well enough, and it was fun to see how mad our Sergeant got when he came after us for picket or guard duties; we thought we had a snap sitting down listening to the machine gun officer's lectures, but what do you think he told us yesterday? Why, that in the event of a retirement machine guns were left behind to cover the retreat, and were sacrificed to save the main body of the Army! Now, wouldn't that be a devil of a fix to be in? No sacrifice stuff for mine—I don't mind taking my chance with the other boys, but I won't stay out there alone." Poor old Bob, we all roasted him about it, but he never went back. Shortly before leaving England almost the entire 10th platoon got leave, and we all went up to London, and I assure you the time we had wasn't slow. Bob and a few of the others whose homes were in London spent part of the time there, but we had a whole week and we spent the last few days together. Among other places of interest, we visited Madame Tussaud's Waxworks, and it was here that Scottie slipped one over Bink. We were all standing at the entrance and Scottie said, "Bink, go and ask the attendant for a program." Bink walked up to the lady at the table, and in his most polite tone said, "Can you let me have a program?" Evidently the attendant didn't hear, for there was no answer, so Bink said in a louder tone, "Say, look here, I want a program"; still there was no response and Bink was beginning to look sore when Scottie yells out, "Come away from there, you darn fool; are you going to talk to that wax figure all day?" Scottie would have "cashed in" right there if Bink could have caught him.

The same day we had a good joke on Steve—he had heard that Leicester Lounge was a favourite meeting-place for Canadians, and he decided to go there and see if he could find any of the boys, so he hailed a taxi and gave the man orders to drive him to Leicester Lounge. The driver took him round a couple of blocks and then said, "Here's the place, Sir." Steve paid him and then looked around to find himself in the very spot he started from—he had been standing in front of Leicester Lounge when he took the taxi, and it is just as well that he does not know what that driver thought of him—however, he was sport enough to tell the joke on himself. Well, the week slipped by and we took a couple of extra days on our own account—of course we expected to pay up for it, but we thought it was worth it. Our next leave would be from France, and anything might happen before then. Well, we got back, and to our joy, we found that the Orderly Sergeant had got "soused" and forgot to mark us absent, so maybe we were not glad that we had those two extra days—the only crimes you are sorry for in the Army are the ones that are found out. Several times after this we took "French leave" and went up to London, and then we had our work cut out dodging the military police. Sometimes we were caught and then we had to pass a day or two in "Clink"—or, in other words, guard-room. We had bathing parade once or twice a week, and we would all go down and have a swim in the sea. Oh, it was great sport, and we were surprised to find it so easy to swim in the salt water. The country around our camp was very hilly and most of our route marches were made with full kit, so a long route march was anything but fun. Our two Americans took a delight in guying Bob about his love for scenery—poor old Bob would be sweating along under his heavy pack and one of the boys would call out, "Well, Bob, how do you like your scenery now?" Bob was silent, perhaps because he needed all his breath for walking, like the small steamboat that put on such a big whistle that it hadn't power enough to navigate and blow its whistle at the same time. But we did enjoy being sent on ahead as scouts to find out the lay of the country. We would travel till we came across some out-of-the-way "pub" or village inn, and there we would stay till it was time to go back to camp; then we would rejoin the battalion and give a lot of information that we had made up between us.

There was one big event that we will remember for the rest of our lives, and that was our review by the King and Lord Kitchener. We were reviewed on Sir John Moore's Plain, and the entire Second Division of Infantry as well as the Artillery was out that day; all the roads leading to the Plain were packed with troops, and as we all marched down and lined up in review order, it was the biggest bunch of soldiers I have ever seen together. There were somewhere between fifteen and sixteen thousand men, and when they were marching with fixed bayonets it looked like a sea of steel.

After lining up we had a long wait, and all at once a thunderstorm came up. The rain came down in pailfuls, and soon all the boys were singing "Throw out the life line, some one is sinking today." One of the boys near me said, "I don't see why the devil no one has ever thought of putting a roof over this blamed island." Well, just when we were in the middle of our song and the whole fifteen thousand men were roaring it out at the top of their voices, the King's automobile went by. We were soon put into marching order and the march past the King and Lord Kitchener commenced. When we got the order "Eyes right!" we looked at them both—the King was a smaller man than we expected to see, and Kitchener looked older than we thought he would be. But oh, what eyes Kitchener had! they seemed to be looking every man straight in the face—the boys all noticed the same thing, and spoke of it afterwards. After the march past the officers were called up and congratulated on the showing the men had made, and they passed it on to us. Well, away we went back to camp, wet and tired, but delighted over the events of the day and we all felt proud of being "Britishers." When we got back to camp and were talking things over, we all agreed that our inspection was a sign of an early departure for France, and from that on the place buzzed with rumours of when we were to start. It does not take much to start a rumour going in the Army—for instance, the Colonel buys a light shirt, and his batman tells somebody that he thinks we are going to a warm climate, as the Colonel is buying light clothes. The person he told it to passes it on this way—"Oh yes, the Colonel's servant says we are going to India," and No. 3 announces "I have it from some one high up that we are being sent to India instead of to France, the Colonel is laying in a supply of light clothes; and in the Quartermaster's store they have gotten in a supply of sun helmets"—and so it goes, increasing in size like the report of a German victory in their newspapers. But we soon saw that our stay was going to be short, for presently our new equipment was issued to us. This consisted of two khaki shirts, two heavy suits of underwear, two heavy army blankets, rifle and ammunition, hat covers, several pairs of socks, a lot of small things, and last but not least, two pairs of boots. Besides this, we had our haversack containing emergency rations: tea, sugar, army biscuits, and bully-beef. I put my pack on the scales when I got it all together, and it weighed just one hundred pounds.

Our new issue of boots came in for more attention than anything else. I must tell you about them; they were destined to cause us no end of misery in the near future. Such boots! "Gravel crushers," we called them. Big heavy marching boots, armour-plated on the sole and so large that they looked and felt like barges. In my childhood days I never could understand how the "Old Lady lived in a shoe," but when I saw these boots the mystery was solved; though, mind you, they were just the thing for France; and after they got broken in, we couldn't have had anything better. But after our light-weight boot manufactured out of paper by some of our patriotic(?) Canadian firms, it took some time to get our feet used to the heavier weight.

Just before we were ready to leave for France we were treated to an air-raid. Some Zeppelins came over and dropped bombs not far from our camp. Of course the warning was sounded, all lights put out, and we sat there as still as mice, wondering what was going to happen next. I fancy we felt something as a rabbit does when there is a keen-eyed hawk soaring overhead. However, the danger passed and there was no harm done, but they were evidently looking for our camp, for two days after we left it, it was properly bombed.

Well, after we got our equipment, we were kept busy for a couple of days signing sheets and undergoing kit inspection, but finally everything was attended to and we were ready to start. It was a hot day when we "fell in" for our eight-mile hike to ——, and when I had all my kit in place, I think I must have looked like a snail who carries his house packed on his back. Well, the farther we went the heavier our load became. Our feet were tortured by the new stiff boots; some of the boys took theirs off and walked in their socks, but these had their feet cut and bruised by the stones which plentifully bestrewed our way. Oh, how we cursed our officers for making us wear our new boots for the first time on such a hike. We should have had them long enough ahead to get them broken in. Well, some of the boys fell out, but the rest of us struggled on, and at last, just at dark, we reached the pier. We were dripping with perspiration, and we had eaten nothing except our army ration. Well, we sat around till we all got cold; and then, to our utter amazement and disgust, the order came, not to embark, but to "right-about-turn"; and with much swearing and grousing, we commenced what was afterwards known among the 6th Brigade as "The Retreat from Folkestone." Of course the officers weren't to blame—some mines had broken loose in the Channel, and until they were looked after by the mine sweepers it wasn't safe to cross. Oh, that march! no one who went through it will ever forget what we went through. In all my experience in France, I never carried such a pack. And after going a short distance on the return trip, the boys, like sinking ships, began to get rid of their cargo—for miles that road was strewn with boots, shirts, sweaters, cap covers, all kinds of articles—then the boys themselves began to fall out, and the dog-tired men rolled themselves in their blankets and lay down in their tracks. By the way, we were not going back to Folkestone, but were bound for a place known as "Sir John Moore's Plain"; but nobody knew how far it was, nor the quickest way to get there; some went one way and some another. Our battalion kept on going with frequent rests; we were dripping with sweat, and when the men sat down to rest they were too tired and disgusted to even swear. Finally our officers turned to us and said, "Only another mile, boys," and our hopes revived a little; but meeting a civilian, I asked him how far it was to Moore's Plain, and he said, "Oh, it's about four miles." Our officer overheard and said "Come on, boys, let's make camp here," and No. 10 platoon quit right there. We were going through a little village at the time, and we piled up on the lawns, rolled out our blankets and went to sleep. Next morning the lady of the house who owned the lawn found us there; she took pity on us, and calling us in gave us our breakfast. Later, we were sitting on the lawn when our Colonel drove up in his automobile. He called, "Come on, boys, hurry up and get up to the camp." He told us how to go and then went on to round up the rest—so we drifted on towards the camp and finally reached it, and all that day the boys came straggling in, some of them still carrying their boots. Well, that night we had to pack up and march down again, but this time it wasn't so hot, and all our spare equipment went by transport. We reached the port about dusk and we were soon loaded up; as soon as we got on board, life-belts had to be put on, and the boat started immediately. We watched the lights of "Old Blighty" flicker and fade away; and every now and then we caught glimpses of destroyers as they went by and disappeared into the darkness. Finally the last lighthouse was passed—no more lights were to be seen, and I turned and looked towards France, wondering what was in store for me there. Little did I think that I would spend a year in Germany before I would see the English shores again.

It wasn't long before the lights of France came in sight. We watched them get clearer and clearer, and soon the command came to put our packs on. We were all ready to march by the time the boat was docked, and off we went. We were on the soil of France, and we all looked around curiously. The first thing I noticed was a French soldier on guard, and I saw that he presented arms in a different way to what we were used to, and also that his bayonet was about twice as long as ours. We soon passed him, and I don't remember much about the march that followed. We were dead-tired, and after travelling for what seemed hours over cobblestones we came to a steep hill—the boys commenced to swear, but we stuck to it for a while. Finally I gave up and lay down beside the road; by this time a lot of the boys had dropped out. After resting a while I started on again, and found Bink and Bob unrolling their blankets—I wanted them to come with me, but a sleep looked good to them. Tommy, Steve, and Baldy were doing the same thing, but instead of following suit I struggled on; at the top of the hill I found a bunch of tents, but that was all—the visions I had of a hot meal faded away, there was no grub in sight—I rolled into one of the tents, spread out my blankets, and had just closed my eyes, when a voice said, "O'Brien, you are on fatigue." I started to kick, but it was no use, so I followed the Sergeant out to where he had a bunch lined up; we were ordered to go down to the commissary tent about five hundred yards distant and draw rations. Well, away we went, and we spent the rest of the night carrying up boxes of jam, butter, bully-beef, and sardines. When I was carrying up the last two boxes, just at daylight, along came the other boys; they thought it was a great joke for them to be comfortably sleeping while I worked getting up grub for them to eat. I couldn't see the fun in it just then, and I told them so, but they only laughed the more. Well, I curled up in my blankets, and it seemed that I had just got to sleep when Tommy wakened me; breakfast was being served, and he had drawn mine. After my bacon and tea and a good wash I felt better.

While we were at breakfast a lot of little French kids crowded around, and we were all amused at the little beggars. Their speech, half French and half English, was very funny. But say, you should have seen them smoke! Little kids hardly able to walk were smoking just like old men. They seemed very hungry, and we gave them lots of our food until we found they were putting it into a sack to carry away.

Well, we stayed in camp till noon, and just after dinner we were told to get ready to move off. Soon we were marching down to take the train, and if the French people who watched us so curiously had seen us go up the night before they would not have recognized us as the same bunch. The French gave us a great reception; the girls brought us fruit, candy, and smokes, and our journey to the station was quite a triumphal procession. One of the girls came running up and gave me a couple of bottles—Rust was beside me and had been through it all before, so he whispered, "Put them in your pack; it is red wine." I guess I was a little slow in getting them out of sight, for our officer saw them and he said, "Don't touch that, it may be poisoned." Of course we had to be careful of spies, but I stuck the bottles in my pack when the officer wasn't looking. Well, we marched to the depot and were soon packed into the small uncomfortable coaches. We started to kick and grumble, but Rust said: "You are lucky to have coaches at all. Last time I went up I rode in a cattle-car," and he pointed out a lot of cars on which was painted "Capacity, so many horses, so many men." After that we hadn't anything more to say.

After much talking and jabbering by the French interpreters we finally got started, and we soon left L——h far behind. I got out my poisoned (?) wine, and not wanting to take any risks myself I politely let Baldy have the first drink. I waited a few minutes and he still looked well, so we finished it up. This put us in good spirits for the trip and every one was gay; no one would ever have imagined that we were on our way to the trenches. We were very much interested in the country we were passing through, but what struck us most forcibly was the number of soldiers we saw. Everywhere we looked there were crowds of them; we thought there were a lot in Blighty, but there seemed to be nothing else here. We passed big railway guns, and once a big Red Cross train glided slowly by—this made us think a bit—but we tried not to look into the future, for we realized that the horrible side of the war would come to us soon enough. Every time the train stopped the French kids would crowd around the coaches crying "Bully-beef, biscuits, cigarettes for my papa, prisoner in Germany." It was all new to us, and we gave them all we could spare. Later on we got wise to the kids, and we found that if we were soft-hearted or soft-headed, they would say the whole family were prisoners. One thing that surprised and shocked us was to hear the little kids swearing; they would use the most frightful oaths, and the funny part of it was that they gave them the pure cockney twang; I suppose they had heard and were imitating the Imperial troops. Well, after travelling all day we finally arrived in C—— and we were marched off to our first billets. I belonged to "C" Company and we were quartered in a barn connected with a farmhouse. It was late when we arrived, and after we had supper we lay down in the straw and soon were all asleep; but it wasn't long before we became uneasy, and soon we were awakened by the feeling that some one or something was trying to bore holes in us. We twisted and turned, but the first ones to waken, tried to keep quiet, and it was not till every one was on the move that we realized that we had made our first acquaintance with the worst pest in the Army—body lice, or "cooties" as they call them—the straw on which we were lying was fairly alive with the little beasts. We thought it strange then, but nearly every billet where there is straw is the same; "soldiers come and soldiers go, but the same straw goes on forever." The next day we were busy boiling our shirts, but if we had only known we might have saved ourselves the trouble, for we were never free from the pests after that. All the belts and powders people send out only seem to fatten them—by the way, gas doesn't kill them either; I think they must have gas helmets. The day was spent in inspection, and the paymaster came and gave us our first pay in France, fifty francs; that night we were allowed downtown, and we made our first acquaintance with the French estaminets or wine-shops; they are only allowed to sell light wines, red and white, to the troops, and French beer. Well, one might just as well drink water. Rust had been through the mill before and could speak French pretty well, and was soon jabbering to the old Frenchwoman, whose face became all smiles when she found he had been wounded at Ypres; her husband had also been wounded there. We wandered in and out every place in the village till it was time to go back to billets. The next day we had to smarten up and get ready for the Brigadier-General, who was going to inspect us. Brigadier-General Ketchen was his name, and instead of a formal inspection he rode up, dismounted, came into the orchard where we were all lined up and said, "Dismiss the men, Major." The Major did so and the Brigadier then spoke to us: "Gather round, boys, I want to have a little talk with you. You've been under my command about nine months now, and I've always been proud of you, and now you are going up the line, and I want to say this to you: Don't go up with any idea that you are going to be killed—we want you all to take care of yourselves and not expose yourselves recklessly—never mind if Bill bets Harry that he can stick his head over without being hit, for if he loses he can't pay. And remember a dead man is no use to us, we want you alive, and when we want you to put your heads up, we'll tell you! And I've no doubt that you will only be too eager. Now, your Colonel and myself have been in the trenches, where you are going, and you are relieving a regiment that has a name second to none out here; and I want you to have the same kind of a name. The food is fine—in fact, we were surprised to see so much and of such good quality in the front line. Above all, I want you to trust your officers as I trust them, and I'm sure they trust you. If at any time you think you are suffering any injustice, don't talk and grumble amongst yourselves, but let's hear about it, and if we can remedy it that's what we want to do. Now, I suppose this will be the last chance I have of talking to you before you go in the trenches, and I don't think there is much more to say. We have a long hike ahead of us tomorrow, and you will march through a town where corps headquarters are, and thousands of soldiers will be there, and I want you to show, by your marching and march discipline, that as soldiers and fighting men Canadians are second to none. That's all, boys!" We thought quite a lot of his speech and the simple way in which it was delivered, and we got to discussing things and sharpening our bayonets and doing a lot more fool things. The place where we were had been occupied by Germans early in the war, a Uhlan patrol having stayed there, and the Frenchman showed a Uhlan lance and scars on the doors and sides of the barn where fragments of shell had struck when they had been chased out. The next day we formed up bright and early, and away we marched. We had not gone far when every neck was craned up, watching some little black and white dots in the sky. I asked Rust what it was. "Oh, anti-aircraft guns shooting at an aeroplane," said he. We strained our eyes, but it was a long way off and high up, and we couldn't see the aeroplane. Later on we saw what looked like big sausages up in the sky. They were the big observation balloons, and so we kept on, something new and interesting all the time. We passed lots of troops out in their rest billets; muddy and dirty some of them looked; they watched us in amused contempt as we swung proudly by, as much as to say, "Wait till you've been through what we have, you won't look so smart." We soon came to B——, and with the regimental band at our head playing, "Pack all your troubles in your old kit-bag" we marched through in great shape. At sundown we reached camp, tired, all in, but still interested. We were quartered in huts close to an old ruined town, and we were within shell fire. Directly we had supper we were outside watching the shells burst about a mile away; I don't think we ever thought of Fritz shelling us. Aeroplanes were flying overhead and our guns were keeping up an incessant roar, but it seemed more on our right; afterwards we knew that it was the big bombardment before the Battle of Loos. We all slept well that night and were up early the next morning. We lounged around all day, and a party of officers and N.C.O.'s went to look over the trenches we were going in. Just at nightfall it started to rain, a cold wet drizzling rain, and when we fell in, it looked as if we were in for a wetting, and we were. We were carrying our packs, and as we started off we were all feeling fine, and if it hadn't been for the rain we wouldn't have minded. I often laugh when I think of that march; we were miles away from any Germans when we started, yet we spoke in whispers,—of course we didn't know any better then,—and whenever a flare went up we stopped, then went on again. We could see where the trenches were as flares were continually going up, lighting up things for a while and then dying out. At last we met some men from the battalion that we were going to relieve, and they acted as guides; past tumble-down houses, along roads full of holes, in and out of mudholes. We were very careful at first, but we might just as well have walked through the lot, for we were all mud to our knees when we got in. We at last entered the communicating trenches and we followed each other, cracking a joke now and again to keep our spirits up; every little while whiz! would go a bullet overhead and we ducked our nuts—we were perfectly safe if we had only known. We passed some Highlanders (Canadians); I suppose they must have been amused at us, as we were all eager to know where the Germans were—I think we had an idea that we were going into a bayonet charge every morning before breakfast. Soon we came to a place where the trench jogged in and out, and in every jog were men standing up and looking across into the blackness; we were in the front line. After much confusion we at last relieved the others. Listening-posts had to be placed and machine guns manned and lots of other things done. We soon found out that one could look over at night and be comparatively safe; there was always a certain amount of rifle fire, but one can't aim at night and the bullets mostly go high. At last day dawned, and we were quite surprised to find that nothing had happened; Scottie and I had our breakfast,—the cook cooked it, and it was distributed in the trench,—then we were put on sentry to watch through the periscope, while the rest had a sleep. We were sitting there talking things over when we heard a roaring noise overhead, and a bing-bang! in the town which lay behind our trenches. We thought it was aeroplanes dropping bombs, and Scottie and I looked for them but we couldn't see anything. At last an officer came along and we asked him. "Oh yes," said he, "those are German shells." Well, after a few days in the trenches we went back to a place called L—— for a rest, or rather we were in reserve. We were now in what was known as the Kemmel Shelters; here we turned night into day—we slept or did nothing in the daytime, but at night we worked like bees—we were busy on fatigue parties carrying up ammunition and provisions to the front lines. Now, don't run off with the idea that this is a bomb-proof job; Fritzie knows all about the supplies that must be brought up, and you can bet your sweet life that he takes a delight in picking off rationing parties, and such-like. Every night our supports were heavily shelled; every road leading to the lines had a battery trained on it and every little while it was swept by shrapnel. We gradually got used to the danger, and if they started to shell the road we were on we would flop into a ditch or shell hole till the storm had passed. Speaking of this reminds me of something that happened in that first week. A party of us were carrying coke to the front line, and we had two sacks each; I had mine tied together and hung around my neck (the way I wore my red mittens when I was a youngster). We walked single file, and the boy ahead called back, "Shell hole, keep to the right," but it was too late for me, one foot had gone in and the weight of the coke made me lose my balance, so in I plunged head first; there was four feet of water in that hole, to say nothing of the soft juicy mud at the bottom, and I gurgled and gasped and was almost drowned before I could free myself from the coke. Finally I struggled out, and without waiting to recover my cargo I made a bee-line for my billet—the boys were fairly killing themselves laughing, and I don't blame them now, for I must have been a pretty-looking bird; I was plastered from head to foot with mud, and dirty water streamed over my beautiful features. Well, after a week of this night duty we were sent eight miles back to "Rest Billets"—here we got a bath—which I assure you was very welcome—also some clean clothes, but we didn't succeed in shaking our friends the "cooties";—like the poor, they were always with us. While on rest we were quartered in some frame huts, and these extended for a quarter of a mile on either side of the road. Between the huts and the road there was an immense ditch, and this usually contained a couple of feet of muddy water; the boys had planks leading from their huts to the road. One night one of the boys came home loaded and he attempted to cross one of these planks—in the darkness he missed his footing and flop! he went into the water; he found himself sitting in about two feet of slushy mud and he put down his hands to push himself up, but the mud was sticky and he only succeeded in going in deeper. We heard him calling for help, and when we got to him only his head and toes were above water; the air around looked very blue, but I don't believe the Recording Angel put down everything he said. He looked so funny we could hardly help him for laughing.

Well, our week's rest was over all too soon for us, and we were sent back to the front lines. This was the routine that we followed that winter; one week in the trenches, one at the supports, and one on rest. We had been up to the trenches three times before we had our first brush with Fritzie; the Battle of Loos was being fought to the southward, but things had been comparatively quiet with us. However, one evening when we were "standing to," just at sunset, suddenly the ground that we were standing on began to rock—we pitched too and fro like drunken men—and farther down the trench the earth opened and a flame of fire shot up into the air. It looked more like a volcano in eruption than anything else, and we couldn't imagine what was happening. Someone yelled, "The Germans are coming!"; but our officer said, "Don't be frightened, boys; a mine has been exploded." The German artillery then opened up a terrific bombardment, and they were answered by our guns, and for about an hour it certainly seemed as if hell had been let loose. We were afraid to take shelter in our dugouts, for we thought that Fritzie might come over any moment, and sure enough, as soon as their gun fire slackened, we saw them coming. It was an exciting moment when we got our first sight of them, and I know I trembled from head to foot; but we opened fire on them and as soon as I began shooting, all fear left me—they never got farther than their own wire entanglements—the rapid fire from our rifles and the support of our guns was too much for them. No doubt they expected to find us all dead after the explosion and the shelling they had given us, but we showed them that we were still very much alive. We "stood to" all that night, but nothing further happened. Just at dawn I peeped over the parapet, and it looked as though some one had been hanging out a wash; their wire entanglements were full of German uniforms. Of course we were not allowed to leave our post during the night in case of another attack, but when morning came we looked around to see what damage the mine had done; we found that about fifty of our brave boys were either killed or wounded—this was the first break in our ranks, and it made us feel very sore—you could put a good-sized house in the crater made by the explosion, and it was to occupy this that the Germans had come over. The crater was immediately organized as a listening-post and ever afterwards it was known as the "Glory Hole." It was always the hottest part of our trench, and many a night I spent in it. The German trench was only thirty yards away, and they could lob bombs in on top of us. To improve matters, old "Glory" always contained at least two feet of water, and on a cold rainy night it was "some job" standing at listening-post, two hours at a stretch, up to the knees in water. When relieved, you had four hours off, and you would huddle up on the firing-step with your feet still in the water, and either smoke or try to get a little sleep. But, often it rained, snowed, and froze all in the same night, and I have had my clothes frozen so stiff that in the morning I could scarcely move.

But, to come back to our story. Next morning the killed and wounded were taken back of the lines, and things went on as before, only now we did not feel nearly so comfortable, knowing that at any moment the earth might open and up we would go. We were in the trenches one day when shuz-z-z-shiz-bang! the dirt flew, not far from us, but we couldn't see what had done it. Later we heard the same noise, and coming tumbling through the air was something that looked like a big black sausage; the moment it struck the ground it exploded with an awful concussion, and dirt and sandbags flew. It was a big trench mortar, and we soon found that if you saw it in time you could dodge it. Fritzie had a special spite at the "Glory Hole," and every little while he would strafe it. About this time we received our first supply of trench mortars, and I assure you we enjoyed using them. They were big round balls weighing about sixty pounds, and they looked something like the English plum pudding. We called them "Plum Puddin's." I don't know what Fritzie called them, but he got them whether he called them or not. They had long steel handles and were easily thrown; no doubt the Germans were just as busy dodging ours as we were getting out of the way of theirs.

For the next couple of months nothing of any importance happened, and all we seemed to do was fill sandbags with mud, dig new trenches, clean out old ones, and wade through mud; and such mud! so many men wading through it worked it up and made it like glue—in some places it was up to the waist and many a man got stuck and had to wait till some one came along and pulled him out—through it all our little bunch stuck together and had lots of fun laughing at each other's misfortunes. We were usually on the same working parties and listening-posts; working on the latter gave us eyes like cats, though I can tell you that it is no fun staring out into "No Man's Land" (the space between the German lines and ours) for hours at a time, not daring to move or speak. We had a wire with us connected with the trench, for a listening-post is always an advanced position, and we used a code of signals. One pull meant "Send up a flare, we want to have a good look around," two pulls "All's well," three "Hostile patrol is out in No Man's Land," and if we threw the bomb that we always carried it meant that the Germans were coming and it gave a general alarm. We had only had the one brush with Fritzie, and the discomforts of the trenches began to get on our nerves; we would much rather have been mixed up in the real fighting. Of course when we were off on rest we had clean clothes, better grub, and our letters and parcels from home; coming up to Christmas the latter became more numerous, and we usually found a bunch waiting for us. We were just like one big family, and the boys who got parcels shared up with those who hadn't any; Bob would pick up Tommy's parcel, look at the name, and say, "We've got a parcel."

Then came our first Christmas in the trenches, or rather in France. We were out at the support billets on Christmas Day, and after working all night we were much disgusted when our Sergeant came in where we were sleeping and told us we had to go up to the lines with some supplies. However, they gave us an issue of rum, and we started out. We had made our trip and were on the road back when a sniper caught sight of us. There was water in the communication trench, and my chum and I got out and walked on top; pretty soon a bullet passed between us but we did not pay any attention, we thought it must be an accident, but a few seconds later, another hit just ahead of us and we realized that we were the "centre of attraction," so we made a bound for the trench; just as we lit, another bullet struck just behind us, so we came pretty near getting a Christmas box from Fritz. We found that we had to take over the trenches that night, so there was not much fuss made over our Christmas dinner, but we had a little extra spread.

However, when New Year's came we were at rest billet, and our beloved Colonel had planned a big dinner for us. It was served in an old schoolhouse and we had roast turkey, plum pudding, and almost everything you could mention, and the Colonel himself came in and carved the turkey for us. All that week on rest we had a glorious time, our parcels had arrived from home and every one was feeling happy.