Project Gutenberg's One Hundred Merrie And Delightsome Stories, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: One Hundred Merrie And Delightsome Stories

Les Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles

Author: Various

Editor: Antoine de la Salle

Illustrator: Léon Lebèque

Translator: Robert B. Douglas

Release Date: June 13, 2006 [EBook #18575]

Last Updated: August 9, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CENT NOUVELLES NOUVELLES ***

Produced by David Widger

Table of Contents

List of Illustrations

ONE HUNDRED MERRIE AND DELIGHTSOME STORIES

DETAILED CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

STORY THE FIRST —THE REVERSE OF THE

MEDAL. [1]

STORY THE SECOND

— THE MONK-DOCTOR.

STORY THE THIRD — THE SEARCH FOR THE RING. [3]

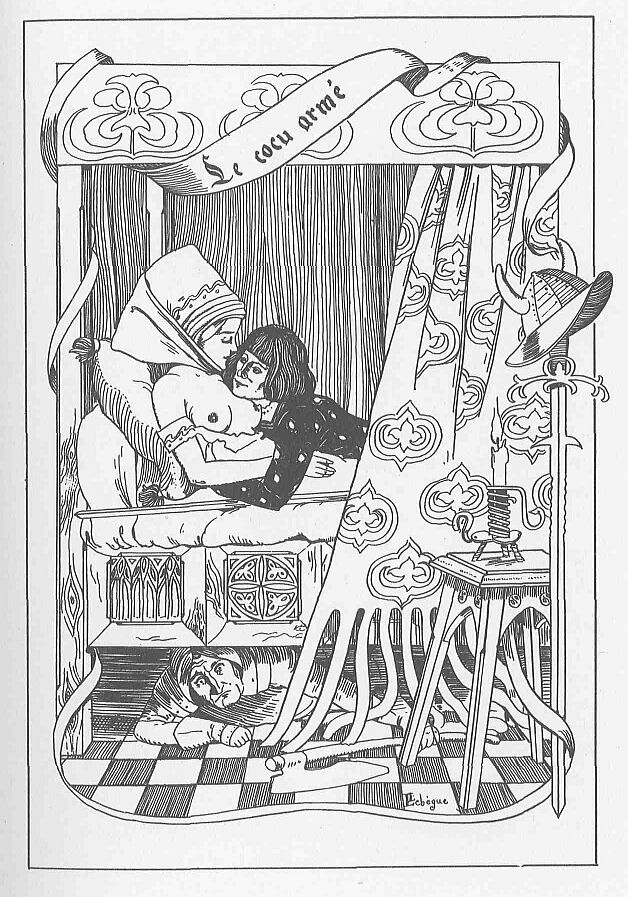

STORY THE FOURTH — THE ARMED CUCKOLD. [4]

STORY THE FIFTH — THE

DUEL WITH THE BUCKLE-STRAP. [5]

STORY THE SIXTH — THE DRUNKARD IN PARADISE. [6]

STORY THE SEVENTH — THE WAGGONER IN THE

BEAR.

STORY THE EIGHTH

— TIT FOR TAT. [8]

STORY THE NINTH — THE HUSBAND PANDAR TO HIS OWN WIFE. [9]

STORY THE TENTH — THE EEL PASTIES.

[10]

STORY THE ELEVENTH

— A SACRIFICE TO THE DEVIL. [11]

STORY THE TWELFTH — THE CALF. [12]

STORY THE THIRTEENTH — THE CASTRATED

CLERK. [13]

STORY THE

FOURTEENTH — THE POPE-MAKER, OR THE HOLY MAN. [14]

STORY THE FIFTEENTH — THE CLEVER NUN.

STORY THE SIXTEENTH —

ON THE BLIND SIDE. [16]

STORY

THE SEVENTEENTH — THE LAWYER AND THE BOLTING-MILL.

STORY THE EIGHTEENTH — FROM BELLY TO

BACK. [18]

STORY THE NINETEENTH

— THE CHILD OF THE SNOW

STORY THE TWENTIETH — THE HUSBAND AS DOCTOR.

STORY THE TWENTY-FIRST — THE ABBESS CURED

[21]

STORY THE TWENTY-SECOND

— THE CHILD WITH TWO FATHERS. [22]

STORY THE TWENTY-THIRD — THE LAWYER’S

WIFE WHO PASSED THE LINE. [23]

STORY THE TWENTY-FOURTH — HALF-BOOTED. [24]

STORY THE TWENTY-FIFTH — FORCED

WILLINGLY. [25]

STORY THE

TWENTY-SIXTH — THE DAMSEL KNIGHT. [26]

STORY THE TWENTY-SEVENTH — THE HUSBAND IN

THE CLOTHES-CHEST. [27]

STORY

THE TWENTY-EIGHTH — THE INCAPABLE LOVER. [28]

STORY THE TWENTY-NINTH — THE COW AND THE

CALF.

STORY THE THIRTIETH

— THE THREE CORDELIERS

STORY THE THIRTY-FIRST — TWO LOVERS FOR ONE LADY. [31]

STORY THE THIRTY-SECOND — THE WOMEN

WHO PAID TITHE. [32]

STORY

THE THIRTY-THIRD — THE LADY WHO LOST HER HAIR.

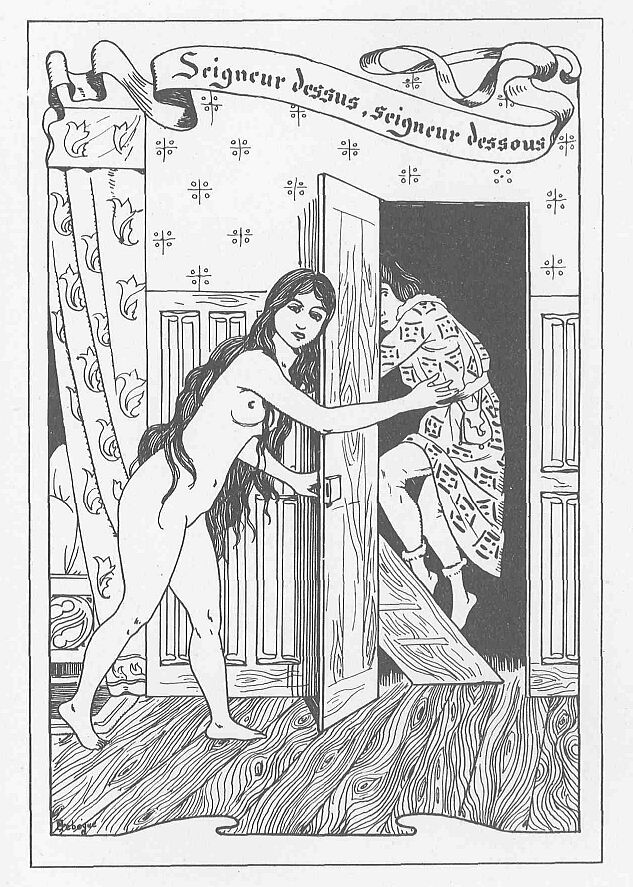

STORY THE THIRTY-FOURTH — THE MAN ABOVE

AND THE MAN BELOW. [34]

STORY

THE THIRTY-FIFTH — THE EXCHANGE.

STORY THE THIRTY-SIXTH — AT WORK.

STORY THE THIRTY-SEVENTH — THE USE OF

DIRTY WATER.

STORY THE

THIRTY-EIGHTH — A ROD FOR ANOTHER’S BACK. [38]

STORY THE THIRTY-NINTH — BOTH WELL

SERVED. [39]

STORY THE

FORTIETH — THE BUTCHER’S WIFE WHO PLAYED THE GHOST IN THE

STORY THE FORTY-FIRST — LOVE IN ARMS.

STORY THE FORTY-SECOND

— THE MARRIED PRIEST. [42]

STORY THE FORTY-THIRD — A BARGAIN IN

HORNS.

STORY THE FORTY-FOURTH

— THE MATCH-MAKING PRIEST.

STORY THE FORTY-FIFTH — THE SCOTSMAN

TURNED WASHERWOMAN

STORY THE

FORTY-SIXTH — HOW THE NUN PAID FOR THE PEARS. [46]

STORY THE FORTY-SEVENTH — TWO MULES

DROWNED TOGETHER. [47]

STORY

THE FORTY-EIGHTH — THE CHASTE MOUTH.

STORY THE FORTY-NINTH — THE SCARLET

BACKSIDE.

STORY THE FIFTIETH

— TIT FOR TAT. [50]

STORY THE FIFTY-FIRST — THE REAL FATHERS.

STORY THE FIFTY-SECOND — THE THREE

REMINDERS. [52]

STORY THE

FIFTY-THIRD — THE MUDDLED MARRIAGES.

STORY THE FIFTY FOURTH — THE RIGHT

MOMENT.

STORY THE FIFTY-FIFTH

— A CURE FOR THE PLAGUE.

STORY THE FIFTY-SIXTH — THE WOMAN, THE PRIEST, THE SERVANT, AND THE

STORY THE FIFTY-SEVENTH

— THE OBLIGING BROTHER.

STORY THE FIFTY-EIGHTH — SCORN FOR SCORN.

STORY THE FIFTY-NINTH — THE SICK LOVER.

[59]

STORY THE SIXTIETH

— THREE VERY MINOR BROTHERS. [60]

STORY THE SIXTY-FIRST — CUCKOLDED—AND

DUPED. [61]

STORY THE

SIXTY-SECOND — THE LOST RING.

STORY THE SIXTY-THIRD — MONTBLERU; OR THE

THIEF. [63]

STORY THE

SIXTY-FOURTH — THE OVER-CUNNING CURÉ. [64]

STORY THE SIXTY-FIFTH — INDISCRETION

REPROVED, BUT NOT PUNISHED.

STORY THE SIXTY-SIXTH — THE WOMAN AT THE BATH.

STORY THE SIXTY-SEVENTH — THE WOMAN WITH

THREE HUSBANDS.

STORY THE

SIXTY-EIGHTH — THE JADE DESPOILED.

STORY THE SIXTY-NINTH — THE VIRTUOUS LADY

WITH TWO HUSBANDS. [69]

STORY

THE SEVENTIETH — THE DEVIL’S HORN.

STORY THE SEVENTY-FIRST — THE CONSIDERATE

CUCKOLD

STORY THE

SEVENTY-SECOND — NECESSITY IS THE MOTHER OF INVENTION.

STORY THE SEVENTY-THIRD — THE BIRD IN

THE CAGE.

STORY THE

SEVENTY-FOURTH — THE OBSEQUIOUS PRIEST.

STORY THE SEVENTY-FIFTH — THE BAGPIPE.

[75]

STORY THE SEVENTY-SIXTH

— CAUGHT IN THE ACT. [76]

STORY THE SEVENTY-SEVENTH — THE SLEEVELESS ROBE.

STORY THE SEVENTY-EIGHTH — THE HUSBAND

TURNED CONFESSOR. [78]

STORY

THE SEVENTY-NINTH — THE LOST ASS FOUND. [79]

STORY THE EIGHTIETH — GOOD MEASURE! [80]

STORY THE EIGHTY-FIRST

— BETWEEN TWO STOOLS. [81]

STORY THE EIGHTY-SECOND — BEYOND THE

MARK. [82]

STORY THE

EIGHTY-THIRD — THE GLUTTONOUS MONK.

STORY THE EIGHTY-FOURTH — THE DEVIL’S

SHARE. [84]

STORY THE

EIGHTY-FIFTH — NAILED! [85]

STORY THE EIGHTY-SIXTH — FOOLISH FEAR.

STORY THE EIGHTY-SEVENTH

— WHAT THE EYE DOES NOT SEE.

STORY THE EIGHTY-EIGHTH — A HUSBAND IN

HIDING. [88]

STORY THE

EIGHTY-NINTH — THE FAULT OF THE ALMANAC.

STORY THE NINETIETH — A GOOD REMEDY. [90]

STORY THE NINETY-FIRST

— THE OBEDIENT WIFE. [91]

STORY THE NINETY-SECOND — WOMEN’S QUARRELS.

STORY THE NINETY-THIRD — HOW A GOOD WIFE

WENT ON A PILGRIMAGE. [93]

STORY THE NINETY-FOURTH — DIFFICULT TO PLEASE.

STORY THE NINETY-FIFTH — THE SORE FINGER

CURED. [95]

STORY THE

NINETY-SIXTH — A GOOD DOG. [96]

STORY THE NINETY-SEVENTH — BIDS AND

BIDDINGS.

STORY THE

NINETY-EIGHTH — THE UNFORTUNATE LOVERS.

STORY THE NINETY-NINTH — THE

METAMORPHOSIS. [99]

STORY THE

HUNDREDTH AND LAST — THE CHASTE LOVER.

NOTES.

Cover.jpg Cover

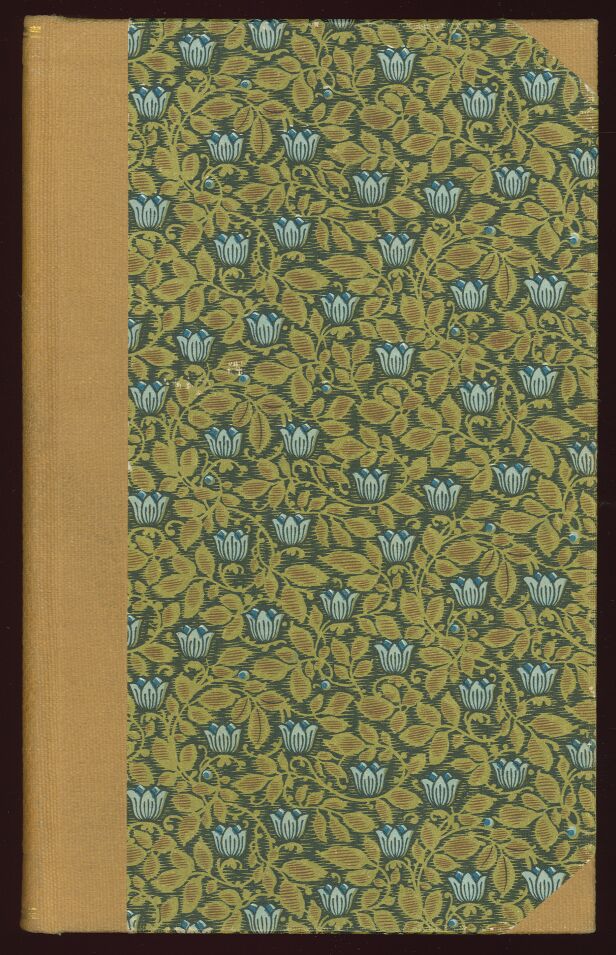

Spines.jpg Spines

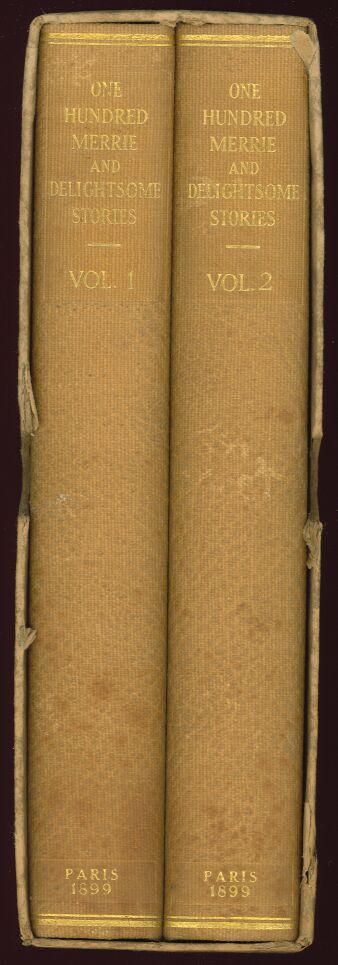

Titlepage.jpg Titlepage

Contents.jpg Contents

Intro.jpg Introduction

01.jpg Story the First — The Reverse of

The Medal.

03.jpg Story the

Third — The Search for The Ring.

04.jpg Story the Fourth — The Armed

Cuckold.

07.jpg The Waggoner

in The Bear.

09.jpg The

Husband Pandar to his Own Wife

12.jpg Story The Twelfth — The Calf.

13.jpg the Castrated Clerk.

14.jpg The Pope-maker, Or The Holy Man.

16.jpg On the Blind Side.

17.jpg The Lawyer and The Bolting-mill.

18.jpg From Belly to Back.

20.jpg The Husband As Doctor.

23.jpg The Lawyer’s Wife Who Passed The

Line.

24.jpg Half-booted

27.jpg The Husband in The

Clothes-chest.

28.jpg The

Incapable Lover.

32.jpg The

Women Who Paid Tithe.

34.jpg

The Man Above and The Man Below.

37.jpg The Use of Dirty Water.

38.jpg A Rod for Another’s Back.

39.jpg Both Well Served.

41.jpg Love in Arms.

43.jpg A Bargain in Horns.

44.jpg The Match-making Priest.

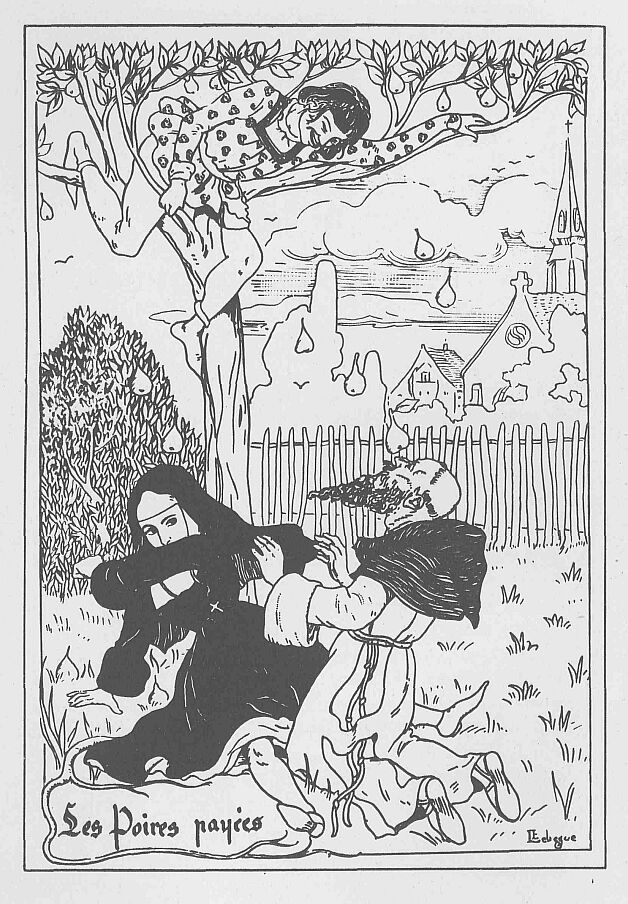

46.jpg How the Nun Paid for The Pears.

49.jpg The Scarlet Backside.

52.jpg The Three Reminders.

54.jpg The Right Moment.

55.jpg A Cure for The Plague.

57.jpg The Obliging BroTher.

60.jpg Three Very Minor BroThers.

61.jpg Cuckolded—and Duped.

62.jpg The Lost Ring.

65.jpg Indiscretion Reproved, But Not

Punished.

68.jpg The Jade

Despoiled.

71.jpg The

Considerate Cuckold

72.jpg

Necessity is The MoTher of Invention.

73.jpg The Bird in The Cage.

76.jpg Caught in The Act.

78.jpg The Husband Turned Confessor.

80.jpg Good Measure!

83.jpg The Gluttonous Monk.

84.jpg The Devil’s Share.

86.jpg Foolish Fear.

88.jpg A Husband in Hiding.

90.jpg A Good Remedy.

92.jpg Women’s Quarrels.

95.jpg The Sore Finger Cured.

97.jpg Bids and Biddings.

100.jpg The Chaste Lover.

Footnotes.jpg Footnotes

Endplate.jpg Endplate

Gilded-top.jpg

INTRODUCTION

STORY THE FIRST — THE REVERSE OF THE MEDAL.

The first story tells of how one found means to enjoy the wife of his

neighbour, whose husband he had sent away in order that he might have

her the more easily, and how the husband returning from his journey,

found his friend bathing with his wife. And not knowing who she was, he

wished to see her, but was permitted only to see her back—, and then

thought that she resembled his wife, but dared not believe it. And

thereupon left and found his wife at home, she having escaped by a

postern door, and related to her his suspicions.

STORY THE SECOND — THE MONK-DOCTOR.

The second story, related by Duke Philip, is of a young girl who had

piles, who put out the only eye he had of a Cordelier monk who was

healing her, and of the lawsuit that followed thereon.

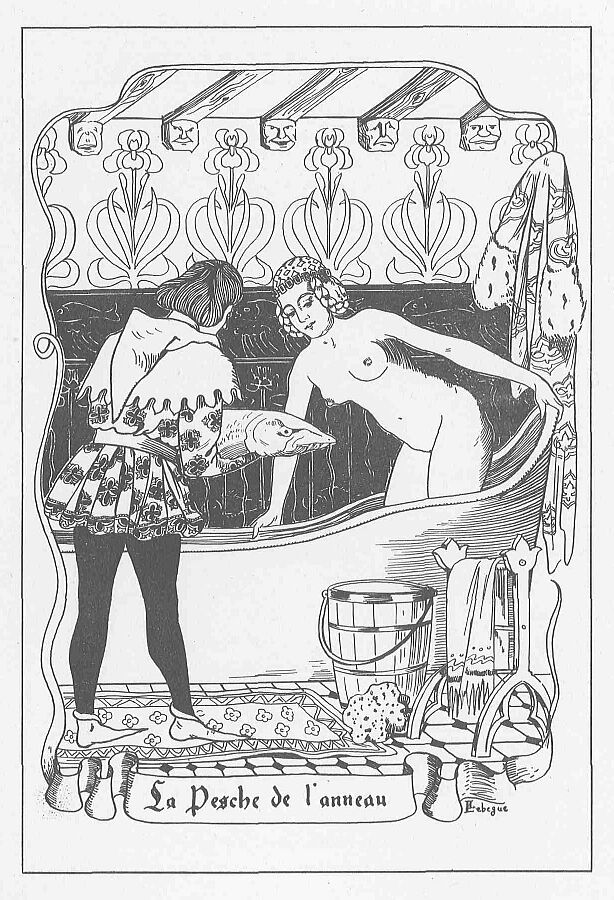

STORY THE THIRD — THE SEARCH FOR THE RING.

Of the deceit practised by a knight on a miller’s wife whom he made

believe that her front was loose, and fastened it many times. And the

miller informed of this, searched for a diamond that the knight’s lady

had lost, and found it in her body, as the knight knew afterwards: so he

called the miller “fisherman”, and the miller called him “fastener”.

STORY THE FOURTH — THE ARMED CUCKOLD.

The fourth tale is of a Scotch archer who was in love with a fair

and gentle dame, the wife of a mercer, who, by her husband’s orders

appointed a day for the said Scot to visit her, who came and treated her

as he wished, the said mercer being hid by the side of the bed, where he

could see and hear all.

STORY THE FIFTH — The Duel with the Buckle-Strap.

The fifth story relates two judgments of Lord Talbot. How a Frenchman

was taken prisoner (though provided with a safe-conduct) by an

Englishman, who said that buckle-straps were implements of war, and who

was made to arm himself with buckle-straps and nothing else, and meet

the Frenchman, who struck him with a sword in the presence of Talbot.

The other, story is about a man who robbed a church, and who was made to

swear that he would never enter a church again.

STORY THE SIXTH —THE DRUNKARD IN PARADISE.

The sixth story is of a drunkard, who would confess to the Prior of the

Augustines at the Hague, and after his confession said that he was then

in a holy state and would die; and believed that his head was cut off

and that he was dead, and was carried away by his companions who said

they were going to bury him.

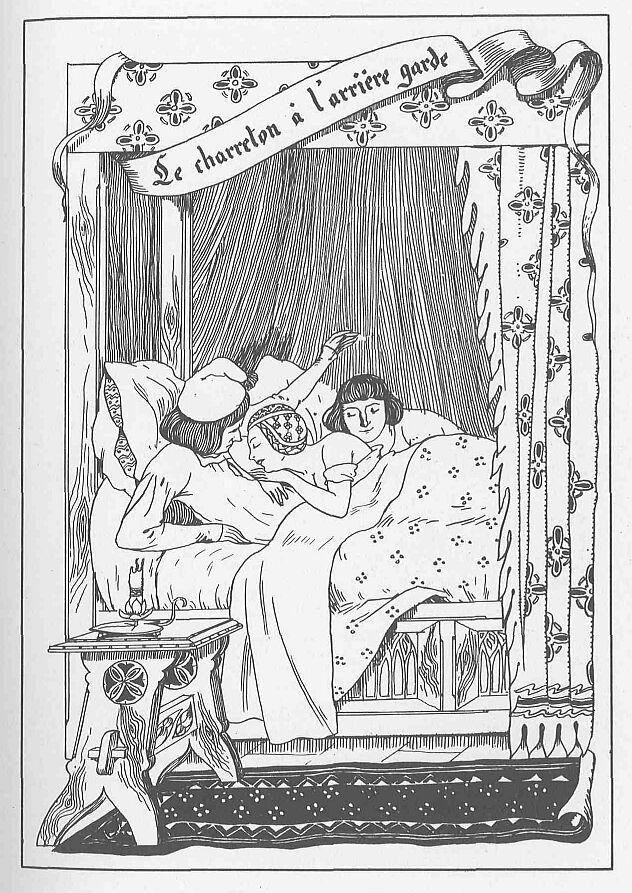

STORY THE SEVENTH — THE WAGGONER IN THE BEAR.

Of a goldsmith of Paris who made a waggoner sleep with him and his

wife, and how the waggoner dallied with her from behind, which the

goldsmith perceived and discovered, and of the words which he spake to

the waggoner.

STORY THE EIGHTH — TIT FOR TAT.

Of a youth of Picardy who lived at Brussels, and made his master’s

daughter pregnant, and for that cause left and came back to Picardy to

be married. And soon after his departure the girl’s mother perceived the

condition of her daughter, and the girl confessed in what state she was;

so her mother sent her to the Picardian to tell him that he must undo

that which he had done. And how his new bride refused then to sleep with

him, and of the story she told him, whereupon he immediately left her

and returned to his first love, and married her.

STORY THE NINTH — THE HUSBAND PANDAR TO HIS OWN WIFE.

Of a knight of Burgundy, who was marvellously amorous of one of his

wife’s waiting women, and thinking to sleep with her, slept with his

wife who was in the bed of the said tire-woman. And how he caused, by

his order, another knight, his neighbour to sleep with the said woman,

believing that it was really the tirewoman—and afterwards he was not

well pleased, albeit that the lady knew nothing, and was not aware, I

believe, that she had had to do with aught other than her own husband.

STORY THE TENTH — THE EEL PASTIES.

Of a knight of England, who, after he was married, wished his mignon to

procuré him some pretty girls, as he did before; which the mignon would

not do, saying that one wife sufficed; but the said knight brought him

back to obedience by causing eel pasties to be always served to him,

both at dinner and at supper.

STORY THE ELEVENTH — A SACRIFICE TO THE DEVIL.

Of a jealous rogue, who after many offerings made to divers saints to

curé him of his jealousy, offered a candle to the devil who is usually

painted under the feet of St. Michael; and of the dream that he had and

what happened to him when he awoke.

STORY THE TWELFTH — THE CALF.

Of a Dutchman, who at all hours of the day and night ceased not to

dally with his wife in love sports; and how it chanced that he laid her

down, as they went through a wood, under a great tree in which was a

labourer who had lost his calf. And as he was enumerating the charms of

his wife, and naming all the pretty things he could see, the labourer

asked him if he could not see the calf he sought, to which the Dutchman

replied that he thought he could see a tail.

STORY THE THIRTEENTH — THE CASTRATED CLERK.

How a lawyer’s clerk in England deceived his master making him believe

that he had no testicles, by which reason he had charge over his

mistress both in the country and in the town, and enjoyed his pleasure.

STORY THE FOURTEENTH — THE POPE-MAKER, OR THE HOLY MAN.

Of a hermit who deceived the daughter of a poor woman, making her

believe that her daughter should have a son by him who should become

Pope; and how, when she brought forth it was a girl, and thus was the

trickery of the hermit discovered, and for that cause he had to flee

from that countery.

STORY THE FIFTEENTH — THE CLEVER NUN.

Of a nun whom a monk wished to deceive, and how he offered to shoo her

his weapon that she might feel it, but brought with him a companion whom

he put forward in his place, and of the answer she gave him.

STORY THE SIXTEENTH — ON THE BLIND SIDE.

Of a knight of Picardy who went to Prussia, and, meanwhile his lady

took a lover, and was in bed with him when her husband returned; and how

by a cunning trick she got her lover out of the room without the knight

being aware of it.

STORY THE SEVENTEENTH — THE LAWYER AND THE BOLTING-MILL.

Of a President of Parliament, who fell in love with his chamber-maid,

and would have forced her whilst she was sifting flour, but by fair

speaking she dissuaded him, and made him shake the sieve whilst she

went unto her mistress, who came and found her husband thus, as you will

afterwards hear.

STORY THE EIGHTEENTH — FROM BELLY TO BACK.

Of a gentleman of Burgundy who paid a chambermaid ten crowns to sleep

with her, but before he left her room, had his ten crowns back, and

made her carry him on her shoulders through the host’s chamber. And in

passing by the said chamber he let wind so loudly that all was known, as

you will hear in the story which follows.

STORY THE NINETEENTH — THE CHILD OF THE SNOW.

Of an English merchant whose wife had a child in his absence, and told

him that it was his; and how he cleverly got rid of the child—for his

wife having asserted that it was born of the snow, he declared it had

been melted by the sun.

STORY THE TWENTIETH — THE HUSBAND AS DOCTOR.

Of a young squire of Champagne who, when he married, had never mounted

a Christian creature,—much to his wife’s regret. And of the method her

mother found to instruct him, and how the said squire suddenly wept at

a great feast that was made shortly after he had learned how to perform

the carnal act—as you will hear more plainly hereafter.

STORY THE TWENTY-FIRST — THE ABBESS CURED

Of an abbess who was ill for want of—you know what—but would not have

it done, fearing to be reproached by her nuns, but they all agreed to do

the same and most willingly did so.

STORY THE TWENTY-SECOND — THE CHILD WITH TWO FATHERS.

Of a gentleman who seduced a young girl, and then went away and joined

the army. And before his return she made the acquaintance of another,

and pretended her child was by him. When the gentleman returned from the

war he claimed the child, but she begged him to leave it with her second

lover, promising that the next she had she would give to him, as is

hereafter recorded.

STORY THE TWENTY-THIRD — THE LAWYER’S WIFE WHO PASSED THE LINE.

Of a clerk of whom his mistress was enamoured, and what he promised to

do and did to her if she crossed a line which the said clerk had made.

Seeing which, her little son told his father when he returned that he

must not cross the line; or said he, “the clerk will serve you as he did

mother.”

STORY THE TWENTY-FOURTH — HALF-BOOTED.

Of a Count who would ravish by force a fair, young girl who was one of

his subjects, and how she escaped from him by means of his leggings,

and how he overlooked her conduct and helped her to a husband, as is

hereafter related.

STORY THE TWENTY-FIFTH — FORCED WILLINGLY.

Of a girl who complained of being forced by a young man, whereas

she herself had helped him to find that which he sought;—and of the

judgment which was given thereon.

STORY THE TWENTY-SIXTH —THE DAMSEL KNIGHT.

Of the loves of a young gentleman and a damsel, who tested the loyalty

of the gentleman in a marvellous and courteous manner, and slept three

nights with him without his knowing that it was not a man,—as you will

more fully hear hereafter.

STORY THE TWENTY-SEVENTH — THE HUSBAND IN THE CLOTHES-CHEST.

Of a great lord of this kingdom and a married lady, who in order

that she might be with her lover caused her husband to be shut in a

clothes-chest by her waiting women, and kept him there all the night,

whilst she passed the time with her lover; and of the wagers made

between her and the said husband, as you will find afterwards recorded.

STORY THE TWENTY-EIGHTH —THE INCAPABLE LOVER.

Of the meeting assigned to a great Prince of this kingdom by a damsel

who was chamber-woman to the Queen; of the little feats of arms of the

said Prince and of the neat replies made by the said damsel to the Queen

concerning her greyhound which had been purposely shut out of the room

of the said Queen, as you shall shortly hear.

STORY THE TWENTY-NINTH — THE COW AND THE CALF.

Of a gentleman to whom—the first night that he was married, and after

he had but tried one stroke—his wife brought forth a child, and of

the manner in which he took it,—and of the speech that he made to his

companions when they brought him the caudle, as you shall shortly hear.

STORY THE THIRTIETH — THE THREE CORDELIERS.

Of three merchants of Savoy who went on a pilgrimage to St. Anthony

in Vienne, and who were deceived and cuckolded by three Cordeliers who

slept with their wives. And how the women thought they had been with

their husbands, and how their husbands came to know of it, and of the

steps they took, as you shall shortly hear.

STORY THE THIRTY-FIRST — TWO LOVERS FOR ONE LADY.

Of a squire who found the mule of his companion, and mounted thereon

and it took him to the house of his master’s mistress; and the squire

slept there, where his friend found him; also of the words which passed

between them—as is more clearly set out below.

STORY THE THIRTY-SECOND — THE WOMEN WHO PAID TITHE.

Of the Cordeliers of Ostelleria in Catalonia, who took tithe from the

women of the town, and how it was known, and the punishment the lord of

that place and his subjects inflicted on the monks, as you shall learn

hereafter.

STORY THE THIRTY-THIRD — THE LADY WHO LOST HER HAIR.

Of a noble lord who was in love with a damsel who cared for another

great lord, but tried to keep it secret; and of the agreement made

between the two lovers concerning her, as you shall hereafter hear.

STORY THE THIRTY-FOURTH — THE MAN ABOVE AND THE MAN BELOW.

Of a married woman who gave rendezvous to two lovers, who came and

visited her, and her husband came soon after, and of the words which

passed between them, as you shall presently hear.

STORY THE THIRTY-FIFTH — THE EXCHANGE.

Of a knight whose mistress married whilst he was on his travels, and on

his return, by chance he came to her house, and she, in order that she

might sleep with him, caused a young damsel, her chamber-maid, to go to

bed with her husband; and of the words that passed between the husband

and the knight his guest, as are more fully recorded hereafter.

STORY THE THIRTY-SIXTH — AT WORK.

Of a squire who saw his mistress, whom he greatly loved, between

two other gentlemern, and did not notice that she had hold of both of

them till another knight informed him of the matter as you will hear.

STORY THE THIRTY-SEVENTH — THE USE OF DIRTY WATER.

Of a jealous man who recorded all the tricks which he could hear or

learn by which wives had deceived their husbands in old times; but at

last he was deceived by means of dirty water which the lover of the said

lady threw out of window upon her as she was going to Mass, as you shall

hear hereafter.

STORY THE THIRTY-EIGHTH — A ROD FOR ANOTHER’S BACK.

Of a citizen of Tours who bought a lamprey which he sent to his wife

to cook in order that he might give a feast to the priest, and the said

wife sent it to a Cordelier, who was her lover, and how she made a woman

who was her neighbour sleep with her husband, and how the woman was

beaten, and what the wife made her husband believe, as you will hear

hereafter.

STORY THE THIRTY-NINTH — BOTH WELL SERVED.

Of a knight who, whilst he was waiting for his mistress amused himself

three times with her maid, who had been sent to keep him company that

he might not be dull; and afterwards amused himself three times with

the lady, and how the husband learned it all from the maid, as you will

hear.

STORY THE FORTIETH — THE BUTCHER’S WIFE THE GHOST IN THE CHIMNEY.

Of a Jacobin who left his mistress, a butcher’s wife, for another woman

who was younger and prettier, and how the said butcher’s wife tried to

enter his house by the chimney.

STORY THE FORTY-FIRST — LOVE IN ARMS.

Of a knight who made his wife wear a hauberk whenever he would do you

know what; and of a clerk who taught her another method which she almost

told her husband, but turned it off suddenly.

STORY THE FORTY-SECOND — THE MARRIED PRIEST.

Of a village clerk who being at Rome and believing that his wife was

dead became a priest, and was appointed curé of his own town, and when

he returned, the first person he met was his wife.

STORY THE FORTY-THIRD — A BARGAIN IN HORNS.

Of a labourer who found a man with his wife, and forwent his revenge

for a certain quantity of wheat, but his wife insisted that he should

complete the work he had begun.

STORY THE FORTY-FOURTH —THE MATCH-MAKING PRIEST.

Of a village priest who found a husband for a girl with whom he was in

love, and who had promised him that when she was married she would do

whatever he wished, of which he reminded her on the wedding-day, and the

husband heard it, and took steps accordingly, as you will hear.

STORY THE FORTY-FIFTH — THE SCOTSMAN TURNED WASHERWOMAN

Of a young Scotsman who was disguised as a woman for the space of

fourteen years, and by that means slept with many girls and married

women, but was punished in the end, as you will hear.

STORY THE FORTY-SIXTH — HOW THE NUN PAID FOR THE PEARS.

Of a Jacobin and a nun, who went secretly to an orchard to enjoy

pleasant pastime under a pear-tree; in which tree was hidden one who

knew of the assignation, and who spoiled their sport for that time, as

you will hear.

STORY THE FORTY-SEVENTH —TWO MULES DROWNED TOGETHER.

Of a President who knowing of the immoral conduct of his wife, caused

her to be drowned by her mule, which had been kept without drink for a

week, and given salt to eat—as is more clearly related hereafter.

STORY THE FORTY-EIGHTH — THE CHASTE MOUTH.

Of a woman who would not suffer herself to be kissed, though she

willingly gave up all the rest of her body except the mouth, to her

lover—and the reason that she gave for this.

STORY THE FORTY-NINTH —THE SCARLET BACKSIDE.

Of one who saw his wife with a man to whom she gave the whole of her

body, except her backside, which she left for her husband and he made

her dress one day when his friends were present in a woollen gown on the

backside of which was a piece of fine scarlet, and so left her before

all their friends.

STORY THE FIFTIETH — TIT FOR TAT.

Of a father who tried to kill his son because the young man wanted to

lie with his grandmother, and the reply made by the said son.

STORY THE FIFTY-FIRST — THE REAL FATHERS.

Of a woman who on her death-bed, in the absence of her husband, made

over her children to those to whom they belonged, and how one of the

youngest of the children informed his father.

STORY THE FIFTY-SECOND — THE THREE REMINDERS.

Of three counsels that a father when on his deathbed gave his son, but

to which the son paid no heed. And how he renounced a young girl he had

married, because he saw her lying with the family chaplain the first

night after their wedding.

STORY THE FIFTY-THIRD — THE MUDDLED MARRIAGES.

Of two men and two women who were waiting to be married at the first

Mass in the early morning; and because the priest could not see well, he

took the one for the other, and gave to each man the wrong wife, as you

will hear.

STORY THE FIFTY FOURTH — THE RIGHT MOMENT.

Of a damsel of Maubeuge who gave herself up to a waggoner, and refused

many noble lovers; and of the reply that she made to a noble knight

because he reproached her for this—as you will hear.

STORY THE FIFTY-FIFTH — A CURÉ FOR THE PLAGUE.

Of a girl who was ill of the plague and caused the death of three men

who lay with her, and how the fourth was saved, and she also.

STORY THE FIFTY-SIXTH — THE WOMAN, PRIEST, SERVANT, AND WOLF.

Of a gentleman who caught, in a trap that he laid, his wife, the

priest, her maid, and a wolf; and burned them all alive, because his

wife committed adultery with the priest.

STORY THE FIFTY-SEVENTH — THE OBLIGING BROTHER.

Of a damsel who married a shepherd, and how the marriage was arranged,

and what a gentleman, the brother of the damsel, said.

STORY THE FIFTY-EIGHTH — SCORN FOR SCORN.

Of two comrades who wished to make their mistresses better inclined

towards them, and so indulged in debauchery, and said, that as after

that their mistresses still scorned them, that they too must have played

at the same game—as you will hear.

STORY THE FIFTY-NINTH — THE SICK LOVER.

Of a lord who pretended to be sick in order that he might lie with the

servant maid, with whom his wife found him.

STORY THE SIXTIETH — THREE VERY MINOR BROTHERS.

Of three women of Malines, who were acquainted with three cordeliers,

and had their heads shaved, and donned the gown that they might not be

recognised, and how it was made known.

STORY THE SIXTY-FIRST — CUCKOLDED—AND DUPED.

Of a merchant who locked up in a bin his wife’s lover, and she secretly

put an ass there which caused her husband to be covered with confusion.

STORY THE SIXTY-SECOND — THE LOST RING.

Of two friends, one of whom left a diamond in the bed of his hostess,

where the other found it, from which there arose a great discussion

between them, which the husband of the said hostess settled in an

effectual manner.

STORY THE SIXTY-THIRD — MONTBLERU; OR THE THIEF.

Of one named Montbleru, who at a fair at Antwerp stole from his

companions their shirts and handkerchiefs, which they had given to the

servant-maid of their hostess to be washed; and how afterwards they

pardoned the thief, and then the said Montbleru told them the whole of

the story.

STORY THE SIXTY-FOURTH — THE OVER-CUNNING CURÉ.

Of a priest who would have played a joke upon a gelder named

Trenche-couille, but, by the connivance of his host, was himself

castrated.

STORY THE SIXTY-FIFTH — INDISCRETION REPROVED, BUT NOT PUNISHED.

Of a woman who heard her husband say that an innkeeper at Mont St.

Michel was excellent at copulating, so went there, hoping to try for

herself, but her husband took means to prevent it, at which she was much

displeased, as you will hear shortly.

STORY THE SIXTY-SIXTH — THE WOMAN AT THE BATH.

Of an inn-keeper at Saint Omer who put to his son a question for which

he was afterwards sorry when he heard the reply, at which his wife was

much ashamed, as you will hear, later.

STORY THE SIXTY-SEVENTH — THE WOMAN WITH THREE HUSBANDS

Of a “fur hat” of Paris, who wished to deceive a cobbler’s wife, but

over-reached, himself, for he married her to a barber, and thinking that

he was rid of her, would have wedded another, but she prevented him, as

you will hear more plainly hereafter.

STORY THE SIXTY-EIGHTH — THE JADE DESPOILED.

Of a married man who found his wife with another man, and devised

means to get from her her money, clothes, jewels, and all, down to

her chemise, and then sent her away in that condition, as shall be

afterwards recorded.

STORY THE SIXTY-NINTH — THE VIRTUOUS LADY WITH TWO HUSBANDS.

Of a noble knight of Flanders, who was married to a beautiful and noble

lady. He was for many years a prisoner in Turkey, during which time his

good and loving wife was, by the importunities of her friends, induced

to marry another knight. Soon after she had remarried, she heard that

her husband had returned from Turkey, whereupon she allowed herself to

die of grief, because she had contracted a fresh marriage.

STORY THE SEVENTIETH — THE DEVIL’S HORN.

Of a noble knight of Germany, a great traveller in his time; who after

he had made a certain voyage, took a vow to never make the sign of

the Cross, owing to the firm faith and belief that he had in the holy

sacrament of baptism—in which faith he fought the devil, as you will

hear.

STORY THE SEVENTY-FIRST — THE CONSIDERATE CUCKOLD

Of a knight of Picardy, who lodged at an inn in the town of St. Omer,

and fell in lave with the hostess, with whom he was amusing himself—you

know how—when her husband discovered them; and how he behaved—as you

will shortly hear.

STORY THE SEVENTY-SECOND — NECESSITY IS THE MOTHER OF INVENTION.

Of a gentleman of Picardy who was enamoured of the wife of a knight his

neighbour; and how he obtained the lady’s favours and was nearly caught

with her, and with great difficulty made his escape, as you will hear

later.

STORY THE SEVENTY-THIRD — THE BIRD IN THE CAGE.

Of a curé who was in love with the wife of one of his parishioners,

with whom the said curé was found by the husband of the woman, the

neighbours having given him warning—and how the curé escaped, as you

will hear.

STORY THE SEVENTY-FOURTH — THE OBSEQUIOUS PRIEST.

Of a priest of Boulogne who twice raised the body of Our Lord whilst

chanting a Mass, because he believed that the Seneschal of Boulogne

had come late to the Mass, and how he refused to take the Pax until the

Seneschal had done so, as you will hear hereafter.

STORY THE SEVENTY-FIFTH — THE BAGPIPE.

Of a hare-brained half-mad fellow who ran a great risk of being put

to death by being hanged on a gibbet in order to injure and annoy the

Bailly, justices, and other notables of the city of Troyes in Champagne

by whom he was mortally hated, as will appear more plainly hereafter.

STORY THE SEVENTY-SIXTH — CAUGHT IN THE ACT.

Of the chaplain to a knight of Burgundy who was enamoured of the wench

of the said knight, and of the adventure which happened on account of

his amour, as you will hear below.

STORY THE SEVENTY-SEVENTH — THE SLEEVELESS ROBE.

Of a gentleman of Flanders, who went to reside in France, but whilst he

was there his mother was very ill in Flanders; and how he often went

to visit her believing that she would die, and what he said and how he

behaved, as you will hear later.

STORY THE SEVENTY-EIGHTH — THE HUSBAND TURNED CONFESSOR.

Of a married gentleman who made many long voyages, during which time his

good and virtuous wife made the acquaintance of three good fellows, as

you will hear; and how she confessed her amours to her husband when he

returned from his travels, thinking she was confessing to the curé, and

how she excused herself, as will appear.

STORY THE SEVENTY-NINTH — THE LOST ASS FOUND.

Of a good man of Bourbonnais who went to seek the advice of a wise man

of that place about an ass that he had lost, and how he believed that he

miraculously recovered the said ass, as you will hear hereafter.

STORY THE EIGHTIETH — GOOD MEASURE!

Of a young German girl, aged fifteen or sixteen or thereabouts who was

married to a gentle gallant, and who complained that her husband had too

small an organ for her liking, because she had seen a young ass of only

six months old which had a bigger instrument than her husband, who was

24 or 26 years old.

STORY THE EIGHTY-FIRST — BETWEEN TWO STOOLS.

Of a noble knight who was in love with a beautiful young married lady,

and thought himself in her good graces, and also in those of another

lady, her neighbour; but lost both as is afterwards recorded.

STORY THE EIGHTY-SECOND — BEYOND THE MARK.

Of a shepherd who made an agreement with a shepherdess that he should

mount upon her “in order that he might see farther,” but was not to

penetrate beyond a mark which she herself made with her hand upon the

instrument of the said shepherd—as will more plainly appear hereafter.

STORY THE EIGHTY-THIRD — THE GLUTTONOUS MONK.

Of a Carmelite monk who came to preach at a village and after his

sermon, he went to dine with a lady, and how he stuffed out his gown, as

you will hear.

STORY THE EIGHTY-FOURTH — THE DEVIL’S SHARE.

Of one of his marshals who married the sweetest and most lovable woman

there was in all Germany. Whether what I tell you is true—for I do

not swear to it that I may not be considered a liar—you will see more

plainly below.

STORY THE EIGHTY-FIFTH — NAILED!

Of a goldsmith, married to a fair, kind, and gracious lady, and very

amorous withal of a curé, her neighbour, with whom her husband found her

in bed, they being betrayed by one of the goldsmith’s servants, who was

jealous, as you will hear.

STORY THE EIGHTY-SIXTH — FOOLISH PEAR.

Of a young man of Rouen, married to a fair, young girl of the age of

fifteen or thereabouts; and how the mother of the girl wished to have

the marriage annulled by the Judge of Rouen, and of the sentence which

the said Judge pronounced when he had heard the parties—as you will

hear more plainly in the course of the said story.

STORY THE EIGHTY-SEVENTH — WHAT THE EYE DOES NOT SEE.

Of a gentle knight who was enamoured of a young and beautiful girl,

and how he caught a malady in one of his eyes, and therefore sent for a

doctor, who likewise fell in love with the same girl, as you will

hear; and of the words which passed between the knight and the doctor

concerning the plaster which the doctor had put on the knight’s good

eye.

STORY THE EIGHTY-EIGHTH — A HUSBAND IN HIDING.

Of a poor, simple peasant married to a nice, pleasant woman, who did

much as she liked, and who in order that she might be alone with her

lover, shut up her husband in the pigeon-house in the manner you will

hear.

STORY THE EIGHTY-NINTH — THE FAULT OF THE ALMANAC.

Of a curé who forgot, either by negligence or ignorance, to inform his

parishioners that Lent had come until Palm Sunday arrived, as you

will hear—and of the manner in which he excused himself to his

parishioners.

STORY THE NINETIETH — A GOOD REMEDY.

Of a good merchant of Brabant whose wife was very ill, and he supposing

that she was about to die, after many remonstrances and exhortations for

the salvation of her soul, asked her pardon, and she pardoned him all

his misdeeds, excepting that he had not worked her as much as he ought

to have done—as will appear more plainly in the said story.

STORY THE NINETY-FIRST — THE OBEDIENT WIFE.

Of a man who was married to a woman so lascivious and lickerish, that

I believe she must have been born in a stove or half a league from the

summer sun, for no man, however well he might work, could satisfy her;

and how her husband thought to punish her, and the answer she gave him.

STORY THE NINETY-SECOND — WOMEN’S QUARRELS.

Of a married woman who was in love with a Canon, and, to avoid

suspicion, took with her one of her neighbours when she went to visit

the Canon; and of the quarrel that arose between the two women, as you

will hear.

STORY THE NINETY-THIRD — HOW A GOOD WIFE WENT ON A PILGRIMAGE.

Of a good wife who pretended to her husband that she was going on

a pilgrimage, in order to find opportunity to be with her lover the

parish-clerk—with whom her husband found her; and of what he said and

did when he saw them doing you know what.

STORY THE NINETY-FOURTH — DIFFICULT TO PLEASE.

Of a curé who wore a short gown, like a gallant about to be married,

for which cause he was summoned before the Ordinary, and of the sentence

which was passed, and the defence he made, and the other tricks he

played afterwards—as you will plainly hear.

STORY THE NINETY-FIFTH — THE SORE FINGER CURED.

Of a monk who feigned to be very ill and in danger of death, that he

might obtain the favours of a certain young woman in the manner which is

described hereafter.

STORY THE NINETY-SIXTH — A GOOD DOG.

Of a foolish and rich village curé who buried his dog in the

church-yard; for which cause he was summoned before his Bishop, ana

how he gave 60 gold crowns to the Bishop, and what the Bishop said to

him—which you will find related here.

STORY THE NINETY-SEVENTH — BIDS AND BIDDINGS.

Of a number of boon companions making good cheer and drinking at

a tavern, and how one of them had a quarrel with his wife when he

returned home, as you will hear.

STORY THE NINETY-EIGHTH — THE UNFORTUNATE LOVERS.

Of a knight of this kingdom and his wife, who had a fair daughter aged

fifteen or sixteen. Her father would have married her to a rich old

knight, his neighbour, but she ran away with another knight, a young

man who loved her honourably; and, by strange mishap, they both died sad

deaths without having ever co-habited,—as you will hear shortly.

STORY THE NINETY-NINTH — THE METAMORPHOSIS.

Relates how a Spanish Bishop, not being able to procure fish, ate

two partridges on a Friday, and how he told his servants that he had

converted them by his prayers into fish—as will more plainly be related

below.

STORY THE HUNDREDTH AND LAST — THE CHASTE LOVER.

Of a rich merchant of the city of Genoa, who married a fair damsel,

who owing to the absence of her husband, sent for a wise clerk—a young,

fit, and proper man—to help her to that of which she had need; and

of the fast that he caused her to make—as you will find more plainly

below.

The highest living authority on French Literature—Professor George Saintsbury—has said:

“The Cent Nouvelles is undoubtedly the first work of literary prose in French, and the first, moreover, of a long and most remarkable series of literary works in which French writers may challenge all comers with the certainty of victory. The short prose tale of a comic character is the one French literary product the pre-eminence and perfection of which it is impossible to dispute, and the prose tale first appears to advantage in the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles. The subjects are by no means new. They are simply the old themes of the fabliaux treated in the old way. The novelty is in the application of prose to such a purpose, and in the crispness, the fluency, and the elegance, of the prose used.”

Besides the literary merits which the eminent critic has pointed out, the stories give us curious glimpses of life in the 15th Century. We get a genuine view of the social condition of the nobility and the middle classes, and are pleasantly surprised to learn from the mouths of the nobles themselves that the peasant was not the down-trodden serf that we should have expected to find him a century after the Jacquerie, and 350 years before the Revolution.

In fact there is an atmosphere of tolerance, not to say bonhommie about these stories which is very remarkable when we consider under what circumstances they were told, and by whom, and to whom.

This seems to have struck M. Lenient, a French critic, who says:

“Generally the incidents and personages belong to the bourgeoisée; there is nothing chivalric, nothing wonderful; no dreamy lovers, romantic dames, fairies, or enchanters. Noble dames, bourgeois, nuns, knights, merchants, monks, and peasants mutually dupe each other. The lord deceives the miller’s wife by imposing on her simplicity, and the miller retaliates in much the same manner. The shepherd marries the knight’s sister, and the nobleman is not over scandalized.

“The vices of the monks are depicted in half a score tales, and the seducers are punished with a severity not always in proportion to the offence.”

It seems curious that this valuable and interesting work has never before been translated into English during the four and a half centuries the book has been in existence. This is the more remarkable as the work was edited in French by an English scholar—the late Thomas Wright. It can hardly be the coarseness of some of the stories which has prevented the Nouvelles from being presented to English readers when there are half a dozen versions of the Heptameron, which is quite as coarse as the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles, does not possess the same historical interest, and is not to be compared to the present work as regards either the stories or the style.

In addition to this, there is the history of the book itself, and its connection with one of the most important personages in French history—Louis XI. Indeed, in many French and English works of reference, the authorship of the Nouvelles has been attributed to him, and though in recent years, the writer is now believed—and no doubt correctly—to have been Antoine de la Salle, it is tolerably certain that Prince Louis heard all the stories related, and very possibly contributed several of them. The circumstances under which these stories came to be narrated requires a few words of explanation.

At a very early age, Louis showed those qualities by which he was later distinguished. When he was only fourteen, he caused his father, Charles VII, much grief, both by his unfilial conduct and his behaviour to the beautiful Agnes Sorel, the King’s mistress, towards whom he felt an implacable hatred. He is said to have slapped her face, because he thought she did not treat him with proper respect. This blow was, it is asserted, the primary cause of his revolt against his father’s authority (1440). The rebellion was put down, and the Prince was pardoned, but relations between father and son were still strained, and in 1446, Louis had to betake himself to his appanage of Dauphiné, where he remained for ten years, always plotting and scheming, and braving his father’s authority.

At length the Prince’s Court at Grenoble became the seat of so many conspiracies that Charles VII was obliged to take forcible measures. It was small wonder that the King’s patience was exhausted. Louis, not content with the rule of his province, had made attempts to win over many of the nobility, and to bribe the archers of the Scotch Guard. Though not liberal as a rule, he had also expended large sums to different secret agents for some specific purpose, which was in all probability to secure his father’s death, for he was not the sort of man to stick at parricide even, if it would secure his ends.

The plot was revealed to Charles by Antoine de Chabannes, Comte de Dampmartin. Louis, when taxed with his misconduct, impudently denied that he had been mixed up with the conspiracy, but denounced all his accomplices, and allowed them to suffer for his misdeeds. He did not, however, forget to revenge them, so far as lay in his power. The fair Agnès Sorel, whom he had always regarded as his bitterest enemy, died shortly afterwards at Jumièges, and it has always been believed, and with great show of reason, that she was poisoned by his orders. He was not able to take vengeance on Antoine de Chabannes until after he became King.

Finding that his plots were of no avail, he essayed to get together an army large enough to combat his father, but before he completed his plans, Charles VII, tired of his endless treason and trickery, sent an army, under the faithful de Chabannes, into the Dauphiné, with orders to arrest the Dauphin.

The forces which Louis had at his disposal were numerically so much weaker, that he did not dare to risk a battle.

“If God or fortune,” he cried, “had been kind enough to give me but half the men-at-arms which now belong to the King, my father, and will be mine some day, by Our Lady, my mistress, I would have spared him the trouble of coming so far to seek me, but would have met him and fought him at Lyon.”

Not having sufficient forces, and feeling that he could not hope for fresh pardon, he resolved to fly from France, and take refuge at the Court of the Duke of Burgundy.

One day in June, 1456, he pretended to go hunting, and then, attended by only half a dozen friends, rode as fast as he could into Burgundian territory, and arrived at Saint Claude.

From there he wrote to his father, excusing his flight, and announcing his intention of joining an expedition which Philippe le Bon, the reigning Duke of Burgundy was about to undertake against the Turks. The Duke was at that moment besieging Utrecht, but as soon as he heard the Dauphin had arrived in his dominions, he sent orders that he was to be conducted to Brussels with all the honours befitting his rank and station.

Shortly afterwards the Duke returned, and listened with real or pretended sympathy to all the complaints that Louis made against his father, but put a damper on any hopes that the Prince may have entertained of getting the Burgundian forces to support his cause, by saying;

“Monseigneur, you are welcome to my domains. I am happy to see you here. I will provide you with men and money for any purpose you may require, except to be employed against the King, your father, whom I would on no account displease.”

Duke Philippe even tried to bring about a reconciliation between Charles and his son; but as Louis was not very anxious to return to France, nor Charles to have him there, and a good many of the nobles were far from desiring that the Prince should come back, the negotiations came to nothing.

Louis could make himself agreeable when he pleased, and during his stay in the Duke’s domains, he was on good terms with Philippe le Bon, who granted him 3000 gold florins a month, and the castle of Genappe as a residence. This castle was situated on the Dyle, midway between Brussels and Louvain, and about eight miles from either city. The river, or a deep moat, surrounded the castle on every side. There was a drawbridge which was drawn up at night, so Louis felt himself quite safe from any attack.

Here he remained five years (1456-1461) until the death of his father placed him on the throne of France.

It was during these five years that these stories were told to amuse his leisure. Probably there were many more than a hundred narrated—perhaps several hundreds—but the literary man who afterwards “edited” the stories only selected those which he deemed best, or, perhaps, those he heard recounted. The narrators were the nobles who formed the Dauphin’s Court. Much ink has been spilled over the question whether Louis himself had any share in the production. In nearly every case the author’s name is given, and ten of them (Nos. 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 29, 33, 69, 70 and 71) are described in the original edition as being by “Monseigneur.” Publishers of subsequent editions brought out at the close of the 15th, or the beginning of the 16th, Century, jumped to the conclusion that “Monseigneur” was really the Dauphin, who not only contributed largely to the book, but after he became King personally supervised the publication of the collected stories.

For four centuries Louis XI was credited with the authorship of the tales mentioned. The first person—so far as I am aware—to throw any doubt on his claim was the late Mr. Thomas Wright, who edited an edition of the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles, published by Jannet, Paris, 1858. He maintained, with some show of reason, that as the stories were told in Burgundy, by Burgundians, and the collected tales were “edited” by a subject of the Duke (Antoine de la Salle, of whom I shall have occasion to speak shortly) it was more probable that “Monseigneur” would mean the Duke than the Dauphin, and he therefore ascribed the stories to Philippe le Bel. Modern French scholars, however, appear to be of opinion that “Monseigneur” was the Comte de Charolais, who afterwards became famous as Charles le Téméraire, the last Duke of Burgundy.

The two great enemies were at that time close friends, and Charles was a very frequent visitor to Genappe. It was not very likely, they say, that Duke Philippe who was an old man would have bothered himself to tell his guest indecent stories. On the other hand, Charles, being then only Comte de Charolais, had no right to the title of “Monseigneur,” but they parry that difficulty by supposing that as he became Duke before the tales were printed, the title was given him in the first printed edition.

The matter is one which will, perhaps, never be satisfactorily settled. My own opinion—though I claim for it no weight or value—is that Louis appears to have the greatest right to the stories, though in support of that theory I can only adduce some arguments, which if separately weak may have some weight when taken collectively. Vérard, who published the first edition, says in the Dedication; “Et notez que par toutes les Nouvelles où il est dit par Monseigneur il est entendu par Monseigneur le Dauphin, lequel depuis a succédé à la couronne et est le roy Loys unsieme; car il estoit lors es pays du duc de Bourgoingne.”

The critics may have good reason for throwing doubt on Vérard’s statement, but unless he printed his edition from a M.S. made after 1467, and the copyist had altered the name of the Comte de Charolais to “Monseigneur” it is not easy to see how the error arose, whilst on the other hand, as Vérard had every facility for knowing the truth, and some of the copies must have been purchased by persons who were present when the stories were told, the mistake would have been rectified in the subsequent editions that Vérard brought out in the course of the next few years, when Louis had been long dead and there was no necessity to flatter his vanity.

On examining the stories related by “Monseigneur,” it seems to me that there is some slight internal evidence that they were told by Louis.

Brantôme says of him that, “he loved to hear tales of loose women, and had but a poor opinion of woman and did not believe they were all chaste. (This sounds well coming from Brantôme) Anyone who could relate such tales was gladly welcomed by the Prince, who would have given all Homer and Virgil too for a funny story.” The Prince must have heard many such stories, and would be likely to repeat them, and we find the first half dozen stories are decidedly “broad,” (No XI was afterwards appropriated by Rabelais, as “Hans Carvel’s Ring”) and we may suspect that Louis tried to show the different narrators by personal example what he considered a really “good tale.”

We know also Louis was subject to fits of religious melancholy, and evinced a superstitious veneration for holy things, and even wore little, leaden images of the saints round his hat. In many of the stories we find monks punished for their immorality, or laughed at for their ignorance, and nowhere do we see any particular veneration displayed for the Church. The only exception is No LXX, “The Devil’s Horn,” in which a knight by sheer faith in the mystery of baptism vanquishes the Devil, whereas one of the knight’s retainers, armed with a battle-axe but not possessing his master’s robust faith in the efficacy of holy water, is carried off bodily, and never heard of again. It seems to me that this story bears the stamp of the character of Louis, who though suspicious towards men, was childishly credulous in religious matters, but I leave the question for critics more capable than I to decide.

Of the thirty-two noblemen or squires who contributed the other stories, mention will be made in the notes. Of the stories, I may here mention that 14 or 15 were taken from Boccaccio, and as many more from Poggio or other Italian writers, or French fabliaux, but about 70 of them appear to be original.

The knights and squires who told the stories had probably no great skill as raconteurs, and perhaps did not read or write very fluently. The tales were written down afterwards by a literary man, and they owe “the crispness, fluency, and elegance,” which, as Prof. Saintsbury remarks, they possess in such a striking degree, to the genius of Antoine de la Sale. He was born in 1398 in Burgundy or Touraine. He had travelled much in Italy, and lived for some years at the Court of the Comte d’ Anjou. He returned to Burgundy later, and was, apparently, given some sort of literary employment by Duke Philippe le Bel. At any rate he was appointed by Philippe or Louis to record the stories that enlivened the evenings at the Castle of Genappe, and the choice could not have fallen on a better man. He was already known as the author of two or three books, one of which—Les Quinze Joyes de Mariage—relates the woes of married life, and displays a knowledge of character, and a quaint, satirical humour that are truly remarkable, and remind the reader alternately of Thackeray and Douglas Jerrold,—indeed some of the Fifteen Joys are “Curtain Lectures” with a mediaeval environment, and the word pictures of Woman’s foibles, follies, and failings are as bright to-day as when they were penned exactly 450 years ago. They show that the “Eternal Feminine” has not altered in five centuries—perhaps not in five thousand!

The practised and facile pen of Antoine de la Sale clothed the dry bones of these stories with flesh and blood, and made them live, and move. Considering his undoubted gifts as a humourist, and a delineator of character it is strange that the name of Antoine de la Sale is not held in higher veneration by his countrymen, for he was the earliest exponent of a form of literary art in which the French have always excelled.

In making a translation of these stories I at first determined to adhere as closely as possible to the text, but found that the versions differed greatly. I have followed the two best modern editions, and have made as few changes and omissions as possible.

Three or four of the stories are extremely coarse, and I hesitated whether to omit them, insert them in the original French, or translate them, but decided that as the book would only be read by persons of education, respectability, and mature age, it was better to translate them fully,—as has been done in the case of the far coarser passages of Rabelais and other writers. This course appeared to me less hypocritical than that adopted in a recent expensive edition of Boccaccio in which the story of Rusticus and Alibech was given in French—with a highly suggestive full-page illustration facing the text for the benefit of those who could not read the French language.

ROBERT B. DOUGLAS.

Paris, 21st October 1899.

Good friends, my readers, who peruse this book,

Be not offended, whilst on it you look:

Denude yourselves of all deprav’d affection,

For it contains no badness nor infection:

‘T is true that it brings forth to you no birth

Of any value, but in point of mirth;

Thinking therefore how sorrow might your mind

Consume, I could no apter subject find;

One inch of joy surmounts of grief a span;

Because to laugh is proper to the man.

(RABELAIS: To the Readers).

The first story tells of how one found means to enjoy the wife of his neighbour, whose husband he had sent away in order that he might have her the more easily, and how the husband returning from his journey, found his friend bathing with his wife. And not knowing who she was, he wished to see her, but was permitted only to see her back—, and then thought that she resembled his wife, but dared not believe it. And thereupon left and found his wife at home, she having escaped by a postern door, and related to her his suspicions.

In the town of Valenciennes there lived formerly a notable citizen, who had been receiver of Hainault, who was renowned amongst all others for his prudence and discretion, and amongst his praiseworthy virtues, liberality was not the least, and thus it came to pass that he enjoyed the grace of princes, lords, and other persons of good estate. And this happy condition, Fortune granted and preserved to him to the end of his days.

Both before and after death unloosed him from the chains of matrimony, the good citizen mentioned in this Story, was not so badly lodged in the said town but that many a great lord would have been content and honoured to have such a lodging. His house faced several streets, in one of which was a little postern door, opposite to which lived a good comrade of his, who had a pretty wife, still young and charming.

And, as is customary, her eyes, the archers of the heart, shot so many arrows into the said citizen, that unless he found some present remedy, he felt his case was no less than mortal.

To more surely prevent such a fate, he found many and subtle manners of making the good comrade, the husband of the said quean, his private and familiar friend, so, that few of the dinners, suppers, banquets, baths, and other such amusements took place, either in the hotel or elsewhere, without his company. And of such favours his comrade was very proud, and also happy.

When our citizen, who was more cunning than a fox, had gained the good-will of his friend, little was needed to win the love of his wife, and in a few days he had worked so much and so well that the gallant lady was fain to hear his case, and to provide a suitable remedy thereto. It remained but to provide time and place; and for this she promised him that, whenever her husband lay abroad for a night, she would advise him thereof.

The wished-for day arrived when the husband told his wife that he was going to a chateau some three leagues distant from Valenciennes, and charged her to look after the house and keep within doors, because his business would not permit him to return that night.

It need not be asked if she was joyful, though she showed it not either in word, or deed, or otherwise. Her husband had not journeyed a league before the citizen knew that the opportunity had come.

He caused the baths to be brought forth, and the stoves to be heated, and pasties, tarts, and hippocras, and all the rest of God’s good gifts, to be prepared largely and magnificently.

When evening came, the postern door was unlocked, and she who was expected entered thereby, and God knows if she was not kindly received. I pass over all this.

Then they ascended into a chamber, and washed in a bath, by the side of which a good supper was quickly laid and served. And God knows if they drank often and deeply. To speak of the wines and viands would be a waste of time, and, to cut the story short, there was plenty of everything. In this most happy condition passed the great part of this sweet but short night; kisses often given and often returned, until they desired nothing but to go to bed.

Whilst they were thus making good cheer, the husband returned from his journey, and knowing nothing of this adventure, knocked loudly at the door of the house. And the company that was in the ante-chamber refused him entrance until he should name his surety.

Then he gave his name loud and clear, and so his good wife and the citizen heard him and knew him. She was so amazed to hear the voice of her husband that her loyal heart almost failed her; and she would have fainted, had not the good citizen and his servants comforted her.

The good citizen being calm and well advised how to act, made haste to put her to bed, and lay close by her; and charged her well that she should lie close to him and hide her face, so that no one could see it. And that being done as quickly as may be, yet without too much haste, he ordered that the door should be opened. Then his good comrade sprang into the room, thinking to himself that there must be some mystery, else they had not kept him out of the room. And when he saw the table laid with wines and goodly viands, also the bath finely prepared, and the citizen in a handsome bed, well curtained, with a second person by his side, God knows he spoke loudly, and praised the good cheer of his neighbour. He called him rascal, and whore-monger, and drunkard, and many other names, which made those who were in the chamber laugh long and loud; but his wife could not join in the mirth, her face being pressed to the side of her new friend.

“Ha!” said the husband, “Master whore-monger, you have well hidden from me this good cheer; but, by my faith, though I was not at the feast, you must show me the bride.”

And with that, holding a candle in his hand, he drew near the bed, and would have withdrawn the coverlet, under which, in fear and silence, lay his most good and perfect wife, when the citizen and his servants prevented him; but he was not content, and would by force, in spite of them all, have laid his hand upon the bed.

But he was not master there, and could not have his will, and for good cause, and was fain to be content with a most gracious proposal which was made to him, and which was this, that he should be shown the backside of his wife, and her haunches, and thighs—which were big and white, and moreover fair and comely—without uncovering and beholding her face.

The good comrade, still holding a candle in his hand, gazed for long without saying a word; and when he did speak, it was to praise highly the great beauty of that dame, and he swore by a great oath that he had never seen anything that so much resembled the back parts of his own wife, and that were he not well sure that she was at home at that time, he would have said it was she.

She had by this somewhat recovered, and he drew back much disconcerted, but God knows that they all told him, first one and then the other, that he had judged wrongly, and spoken against the honour of his wife, and that this was some other woman, as he would afterwards see for himself.

To restore him to good humour, after they had thus abused his eyes, the citizen ordered that they should make him sit at the table, where he drowned his suspicions by eating and drinking of what was left of the supper, whilst they in the bed were robbing him of his honour.

The time came to leave, and he said good night to the citizen and his companions, and begged they would let him leave by the postern door, that he might the sooner return home. But the citizen replied that he knew not then where to find the key; he thought also that the lock was so rusted that they could not open the door, which they rarely if ever used. He was content therefore to leave by the front gate, and make a long detour to reach his house, and whilst the servants of the citizen led him to the door, the good wife was quickly on her feet, and in a short time, clad in a simple sark, with her corset on her arm, and come to the postern. She made but one bound to her house, where she awaited her husband (who came by a longer way) well-prepared as to the manner in which she should receive him.

Soon came our man, and seeing still a light in the house, knocked at the door loudly; and this good wife, who was pretending to clean the house, and had a besom in her hands, asked — what she knew well; “Who is there?”

And he replied; “It is your husband.”

“My husband!” said she. “My husband is not here! He is not in the town!”

With that he knocked again, and cried, “Open the door! I am your husband.”

“I know my husband well,” quoth she, “and it is not his custom to return home so late at night, when he is in the town. Go away, and do not knock here at this hour.”

But he knocked all the more, and called her by name once or twice. Yet she pretended not to know him, and asked why he came at that hour, but for all reply he said nothing but, “Open! Open!”

“Open!” said she. “What! are you still there you rascally whore-monger? By St. Mary, I would rather see you drown than come in here! Go! and sleep as badly as you please in the place where you came from.”

Then her good husband grew angry, and thundered against the door as though he would knock the house down, and threatened to beat his wife, such was his rage,—of which she had not great fear; but at length, because of the noise he made, and that she might the better speak her mind to him, she opened the door, and when he entered, God knows whether he did not see an angry face, and have a warm greeting. For when her tongue found words from a heart overcharged with anger and indignation, her language was as sharp as well-ground Guingant razors.

And, amongst other things, she reproached him that he had wickedly pretended a journey in order that he might try her, and that he was a coward and a recreant, unworthy to have such a wife as she was.

Our good comrade, though he had been angry, saw how wrong he had been, and restrained his wrath, and the indignation that in his heart he had conceived when he was standing outside the door was turned aside. So he said, to excuse himself, and to satisfy his wife, that he had returned from his journey because he had forgotten a letter concerning the object of his going.

Pretending not to believe him, she invented more stories, and charged him with having frequented taverns and bagnios, and other improper and dissolute resorts, and that he behaved as no respectable man should, and she cursed the hour in which she had made his acquaintance, and doubly cursed the day she became his wife.

The poor man, much grieved, seeing his wife more troubled than he liked, knew not what to say. And his suspicions being removed, he drew near her, weeping and falling upon his knees and made the following fine speech.

“My most dear companion, and most loyal wife, I beg and pray of you to remove from your heart the wrath you have conceived against me, and pardon me for all that I have done against you. I own my fault, I see my error. I have come now from a place where they made good cheer, and where, I am ashamed to say, I fancied I recognised you, at which I was much displeased. And so I wrongfully and causelessly suspected you to be other than a good woman, of which I now repent bitterly, and pray of you to forgive me, and pardon my folly.”

The good woman, seeing her husband so contrite, showed no great anger.

“What?” said she, “You have come from filthy houses of ill-fame, and you dare to think that your honest wife would be seen in such places?”

“No, no, my dear, I know you would not. For God’s sake, say no more about it.” said the good man, and repeated his aforesaid request.

She, seeing his contrition, ceased her reproaches, and little by little regained her composure, and with much ado pardoned him, after he had made a hundred thousand oaths and promises to her who had so wronged him. And from that time forth she often, without fear or regret, passed the said postern, nor were her escapades discovered by him who was most concerned. And that suffices for the first story.

The second story, related by Duke Philip, is of a young girl who had piles, who put out the only eye he had of a Cordelier monk who was healing her, and of the lawsuit that followed thereon.

In the chief town of England, called London, which is much resorted to by many folks, there lived, not long ago, a rich and powerful man who was a merchant and citizen, who beside his great wealth and treasures, was enriched by the possession of a fair daughter, whom God had given him over and above his substance, and who for goodness, prettiness, and gentleness, surpassed all others of her time, and who when she was fifteen was renowned for her virtue and beauty.

God knows that many folk of good position desired and sought for her good grace by all the divers manners used by lovers,—which was no small pleasure to her father and mother, and increased their ardent and paternal affection for their beloved daughter.

But it happened that, either by the permission of God, or that Fortune willed and ordered it so, being envious and discontented at the prosperity of this beautiful girl, or of her parents, or all of them,—or may be from some secret and natural cause that I leave to doctors and philosophers to determine, that she was afflicted with an unpleasant and dangerous disease which is commonly called piles.

The worthy family was greatly troubled when they found the fawn they so dearly loved, set on by the sleuth-hounds and beagles of this unpleasant disease, which had, moreover, attacked its prey in a dangerous place. The poor girl—utterly cast down by this great misfortune,—could do naught else than weep and sigh. Her grief-stricken mother was much troubled; and her father, greatly vexed, wrung his hands, and tore his hair in his rage at this fresh misfortune.

Need I say that all the pride of that household was suddenly cast down to the ground, and in one moment converted into bitter and great grief.

The relations, friends, and neighbours of the much-enduring family came to visit and comfort the damsel; but little or nothing might they profit her, for the poor girl was more and more attacked and oppressed by that disease.

Then came a matron who had much studied that disease, and she turned and re-turned the suffering patient, this way, and that way, to her great pain and grief, God knows, and made a medicine of a hundred thousand sorts of herbs, but it was no good; the disease continued to get worse, so there was no help but to send for all the doctors of the city and round about, and for the poor girl to discover unto them her most piteous case.

There came Master Peter, Master John, Master This, Master That—as many doctors as you would, who all wished to see the patient together, and uncover that portion of her body where this cursed disease, the piles had, alas, long time concealed itself.

The poor girl, as much cast down and grieved as though she were condemned to die, would in no wise agree or permit that her affliction should be known; and would rather have died than shown such a secret place to the eyes of any man.

This obstinacy though endured not long, for her father and her mother came unto her, and remonstrated with her many times,—saying that she might be the cause of her own death, which was no small sin; and many other matters too long to relate here.

Finally, rather to obey her father and mother than from fear of death, the poor girl allowed herself to be bound and laid on a couch, head downwards, and her body so uncovered that the physicians might see clearly the seat of the disease which troubled her.

They gave orders what was to be done, and sent apothecaries with clysters, powders, ointments, and whatsoever else seemed good unto them; and she took all that they sent, in order that she might recover her health.

But all was of no avail, for no remedy that the said physicians could apply helped to heal the distressing malady from which she suffered, nor could they find aught in their books, until at last the poor girl, what with grief and pain was more dead than alive, and this grief and great weakness lasted many days.

And whilst the father and mother, relations, and neighbours sought for aught that might alleviate their daughter’s sufferings, they met with an old Cordelier monk, who was blind of one eye, and who in his time had seen many things, and had dabbled much in medicine, therefore his presence was agreeable to the relations of the patient, and he having gazed at the diseased part at his leisure, boasted much that he could cure her.

You may fancy that he was most willingly heard, and that all the grief-stricken assembly, from whose hearts all joy had been banished, hoped that the result would prove as he had promised.

Then he left, and promised that he would return the next day, provided and furnished with a drug of such virtue, that it would at once remove the great pain and martyrdom which tortured and annoyed the poor patient.

The night seemed over-long, whilst waiting for the wished-for morrow; nevertheless, the long hours passed, and our worthy Cordelier kept his promise, and came to the patient at the hour appointed. You may guess that he was well and joyously received; and when the time came when he was to heal the patient, they placed her as before on a couch, with her backside covered with a fair white cloth of embroidered damask, having, where her malady was, a hole pierced in it through which the Cordelier might arrive at the said place.

He gazed at the seat of the disease, first from one side, then from the other: and anon he would touch it gently with his finger, or inspect the tube by which he meant to blow in the powder which was to heal her, or anon would step back and inspect the diseased parts, and it seemed as though he could never gaze enough.

At last he took the powder in his left hand, poured upon a small flat dish, and in the other hand the tube, which he filled with the said powder, and as he gazed most attentively and closely through the opening at the seat of the painful malady of the poor girl, she could not contain herself, seeing the strange manner in which the Cordelier gazed at her with his one eye, but a desire to burst out laughing came upon her, though she restrained herself as long as she could.

But it came to pass, alas! that the laugh thus held back was converted into a f—t, the wind of which caught the powder, so that the greater part of it was blown into the face and into the eye of the good Cordelier, who, feeling the pain, dropped quickly both plate and tube, and almost fell backwards, so much was he frightened. And when he came to himself, he quickly put his hand to his eye, complaining loudly, and saying that he was undone, and in danger to lose the only good eye he had.

Nor did he lie, for in a few days, the powder which was of a corrosive nature, destroyed and ate away his eye, so that he became, and remained, blind.

Then he caused himself to be led one day to the house where he had met with this sad mischance, and spoke to the master of the house, to whom he related his pitiful case, demanding, as was his right, that there should be granted to him such amends as his condition deserved, in order that he might live honourably.

The merchant replied that though the misadventure greatly vexed him, he was in nowise the cause of it, nor could he in any way be charged with it, but that he would, out of pity and charity, give him some money, and though the Cordelier had undertaken to cure his daughter and had not so done, would give him as much as he would if she had been restored to health, though not forced to do so.