The Project Gutenberg EBook of Captain Scraggs, by Peter B. Kyne

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Captain Scraggs

or, The Green-Pea Pirates

Author: Peter B. Kyne

Illustrator: Gordon Grant

Release Date: May 29, 2006 [EBook #18469]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CAPTAIN SCRAGGS ***

Produced by Suzanne Lybarger, Alison Bush and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

XI |

XII |

XIII |

XIV |

XV |

XVI |

XVII

XVIII |

XIX |

XX |

XXI |

XXII |

XXIII |

XXIV |

XXV |

XXVI |

XXVII |

XXVIII |

XXIX

They had seen the fog rolling down the coast shortly after the Maggie had rounded Pilar Point at sunset and headed north. Captain Scraggs has been steamboating too many unprofitable years on San Francisco Bay, the Suisun and San Pablo sloughs and dogholes and the Sacramento River to be deceived as to the character of that fog, and he remarked as much to Mr. Gibney. "We'd better turn back to Halfmoon Bay and tie up at the dock," he added.

"Calamity howler!" retorted Mr. Gibney and gave the wheel a spoke or two. "Scraggsy, you're enough to make a real sailor sick at the stomach."

"But I tell you she's a tule fog, Gib. She rises up in the marshes of the Sacramento and San Joaquin, drifts down to the bay and out the Golden Gate and just naturally blocks the wheels of commerce while she lasts. Why, I've known the ferry boats between San Francisco and Oakland to get lost for hours on their twenty-minute run—and all along of a blasted tule fog."

"I don't doubt your word a mite, Scraggsy. I never did see a ferry-boat skipper that knew shucks about sailorizing," the imperturbable Gibney responded. "Me, I'll smell my way home in any tule fog."

"Maybe you can an' maybe you can't, Gib, although far be it from me to question your ability. I'll take it for granted. Nevertheless, I ain't a-goin' to run the risk o' you havin' catarrh o' the nose an' confusin' your smells to-night. You ain't got nothin' at stake but your job, whereas if I lose the Maggie I lose my hull fortune. Bring her about, Gib, an' let's hustle back."

"Don't be an old woman," Mr. Gibney pleaded. "Scraggs, you just ain't got enough works inside you to fill a wrist watch."

"I ain't a-goin' to poke around in the dark an' a tule fog, feelin' for the Golden Gate," Captain Scraggs shrilled peevishly.

"Hell's bells an' panther tracks! I've got my old courses, an' if I foller them we can't help gettin' home."

Captain Scraggs laid his hand on Mr. Gibney's great arm and tried to smile paternally. "Gib, my dear boy," he pleaded, "control yourself. Don't argue with me, Gib. I'm master here an' you're mate. Do I make myself clear?"

"You do, Scraggsy. But it won't avail you nothin'. You're only master becuz of a gentleman's agreement between us two, an' because I'm man enough to figger there's certain rights due you as owner o' the Maggie. But don't you forget that accordin' to the records o' the Inspector's office, I'm master of the Maggie, an' the way I figger it, whenever there's any call to show a little real seamanship, that gentleman's agreement don't stand."

"But this ain't one o' them times, Gib."

"You're whistlin' it is. If we run from this here fog, it's skiffs to battleships we don't get into San Francisco Bay an' discharged before six o'clock to-morrow night. By the time we've taken on coal an' water an' what-all, it'll be eight or nine o'clock, with me an' McGuffey entitled to mebbe three dollars overtime an' havin' to argue an' scrap with you to git it—not to speak o' havin' to put to sea the same night so's to be back in Halfmoon Bay to load bright an' early next mornin'. Scraggsy, I ain't no night bird on this run."

"Do you mean to defy me, Gib?" Captain Scraggs' little green eyes gleamed balefully. Mr. Gibney looked down upon him with tolerance, as a Great Dane gazes upon a fox terrier. "I certainly do, Scraggsy, old pepper-pot," he replied calmly. "What're you goin' to do about it?" The ghost of a smile lighted his jovial countenance.

"Nothin'—now. I'm helpless," Captain Scraggs answered with deadly calm. "But the minute we hit the dock you an' me parts company."

"I don't know whether we will or not, Scraggsy. I ain't heeled right financially to hit the beach on such short notice."

"That ain't no skin off'n my nose, Gib."

"Well, you can fire all you want, but you won't fire me. I won't go."

"I'll get the police to remove you, you blistered pirate," Scraggs screamed, now quite beside himself.

"Yes? Well, the minute they let go o' me I'll come back to the S.S. Maggie and tear her apart just to see what makes her go." He leaned out the pilot house window and sniffed. "Tule fog, all right, Scraggs. Still, that ain't no reason why the ship's company should fast, is it? Quit bickerin' with me, little one, an' see if you can't wrastle up some ham an' eggs. I want my eggs sunny side up."

Sensing the futility of further argument, Captain Scraggs sought solace in a stream of adjectival opprobrium, plainly meant for Mr. Gibney but delivered, nevertheless, impersonally. He closed the pilot house door furiously behind him and started for the galley.

"Some bright day I'm goin' to git tired o' hearin' you cuss my proxy," Mr. Gibney bawled after him, "an' when that fatal time arrives I'll scatter a can o' Kill-Flea over you an' the shippin' world'll know you no more."

"Oh, go to—glory, you pig-iron polisher," Captain Scraggs tossed back at him over his shoulder—and honour was satisfied. In the lee of the pilot house Captain Scraggs paused, set his infamous old brown derby hat on the deck and leaped furiously upon it with both feet. Six times he did this; then with a blow of his fist he knocked the ruin back into a semblance of its original shape and immediately felt better.

"If I was you, skipper, I'd hold my temper until I got to port; then I'd git jingled an' forgit my troubles inexpensively," somebody advised him.

Scraggs turned. In a little square hatch the head and shoulders of Mr. Bartholomew McGuffey, chief engineer; first, second and third assistant engineer, oiler, wiper, water-tender, and coal-passer of the Maggie, appeared. He was standing on the steel ladder that led up from his stuffy engine room and had evidently come up, like a whale, for a breath of fresh air. "The way you ruin them bonnets o' yourn sure is a scandal," Mr. McGuffey concluded. "If I had a temper as nasty as yourn I'd take soothin' syrup or somethin' for it."

Without waiting for a reply, Mr. McGuffey dropped back into his department and Captain Scraggs, his soul filled with rage and dire forebodings, repaired to the galley, and "candled" four dozen eggs. Out of the four dozen he found nine with black spots in them and carefully set them aside to be fried, sunny side up, for Mr. Gibney and McGuffey.

Before proceeding further with this narrative, due respect for the reader's curiosity directs that we diverge for a period sufficient to present a brief history of the steamer Maggie and her peculiar crew. We will begin with the Maggie.

She had been built on Puget Sound back in the eighties, and was one hundred and six feet over all, twenty-six feet beam and seven feet draft. Driven by a little steeple compound engine, in the pride of her youth she could make ten knots. However, what with old age and boiler scale, the best she could do now was six, and had Mr. McGuffey paid the slightest heed to the limitations imposed upon his steam gauge by the Supervising Inspector of Boilers at San Francisco, she would have been limited to five. Each annual inspection threatened to be her last, and Captain Scraggs, her sole owner, lived in perpetual fear that eventually the day must arrive when, to save the lives of himself and his crew, he would be forced to ship a new boiler and renew the rotten timbers around her deadwood. She had come into Captain Scraggs's possession at public auction conducted by the United States Marshal, following her capture as she sneaked into San Francisco Bay one dark night with a load of Chinamen and opium from Ensenada. She had cost him fifteen hundred hard-earned dollars.

Scraggs—Phineas P. Scraggs, to employ his full name, was precisely the kind of man one might expect to own and operate the Maggie. Rat-faced, snaggle toothed and furtive, with a low cunning that sometimes passed for great intelligence, Scraggs' character is best described in a homely American word. He was "ornery." A native of San Francisco, he had grown up around the docks and had developed from messboy on a river steamer to master of bay and river steamboats, although it is not of record that he ever commanded such a craft. Despite his "ticket" there was none so foolish as to trust him with one—a condition of affairs which had tended to sour a disposition not naturally sweet. The yearning to command a steamboat gradually had developed into an obsession. Result—the "fast and commodious S.S. Maggie," as the United States Marshal had had the audacity to advertise her.

In the beginning, Captain Scraggs had planned to do bay and river towing with the Maggie. Alas! The first time the unfortunate Scraggs attempted to tow a heavily laden barge up river, a light fog had come down, necessitating the frequent blowing of the whistle. Following the sixth long blast, Mr. McGuffey had whistled Scraggs on the engine room howler; swearing horribly, he had demanded to be informed why in this and that the skipper didn't leave that dod-gasted whistle alone. It was using up his steam faster than he could manufacture it. Thereafter, Scraggs had used a patent foghorn, and when the honest McGuffey had once more succeeded in conserving sufficient steam to crawl up river, the tide had turned and the Maggie could not buck the ebb. McGuffey declared a few new tubes in the boiler would do the trick, but on the other hand, Mr. Gibney pointed out that the old craft was practically punk aft and a stiff tow would jerk the tail off the old girl. In despair, therefore, Captain Scraggs had abandoned bay and river towing and was prepared to jump overboard and end all, when an opportunity offered for the freighting of garden truck and dairy produce from Halfmoon Bay to San Francisco.

But now a difficulty arose. The new run was an "outside" one—salt water all the way. Under the ruling of the Inspectors, the Maggie would be running coastwise the instant she engaged in the green pea and string bean trade, and Captain Scraggs's license provided for no such contingency. His ticket entitled him to act as master on the waters of San Francisco Bay and the waters tributary thereto, and although Scraggs argued that the Pacific Ocean constituted waters "tributary thereto," if he understood the English language, the Inspectors were obdurate. What if the distance was less than twenty-five miles? they pointed out. The voyage was undeniably coastwise and carried with it all the risk of wind and wave. And in order to impress upon Captain Scraggs the weight of their authority, the Inspectors suspended for six months Captain Scraggs's bay and river license for having dared to negotiate two coastwise voyages without consulting them. Furthermore, they warned him that the next time he did it they would condemn the fast and commodious Maggie.

In his extremity, Fate had sent to Captain Scraggs a large, imposing, capable, but socially indifferent person who responded to the name of Adelbert P. Gibney. Mr. Gibney had spent part of an adventurous life in the United States Navy, where he had applied himself and acquired a fair smattering of navigation. Prior to entering the Navy he had been a foremast hand in clipper ships and had held a second mate's berth. Following his discharge from the Navy he had sailed coastwise on steam schooners, and after attending a navigation school for two months, had procured a license as chief mate of steam, any ocean and any tonnage.

Unfortunately for Mr. Gibney, he had a failing. Most of us have. The most genial fellow in the world, he was cursed with too much brains and imagination and a thirst which required quenching around pay-day. Also, he had that beastly habit of command which is inseparable from a born leader; when he held a first mate's berth, he was wont to try to "run the ship" and, on occasions, ladle out suggestions to his skipper. Thus, in time, he had acquired a reputation for being unreliable and a wind-bag, with the result that skippers were chary of engaging him. Not to be too prolix, at the time Captain Scraggs made the disheartening discovery that he had to have a skipper for the Maggie, Mr. Gibney found himself reduced to the alternative of longshore work or a fo'castle berth in a windjammer bound for blue water.

With alacrity, therefore, Mr. Gibney had accepted Scraggs's offer of seventy-five dollars a month—"and found"—to skipper the Maggie on her coastwise run. As a first mate of steam he had no difficulty inducing the Inspectors to grant him a license to skipper such an abandoned craft as the Maggie, and accordingly he hung up his ticket in her pilot house and was registered as her master, albeit, under a gentlemen's agreement, with Scraggs he was not to claim the title of captain and was known to the world as the Maggie's first mate, second mate, third mate, quartermaster, purser, and freight clerk. One Neils Halvorsen, a solemn Swede with a placid, bovine disposition, constituted the fo'castle hands, while Bart McGuffey, a wastrel of the Gibney type but slower-witted, reigned supreme in the engine room. Also his case resembled that of Mr. Gibney in that McGuffey's job on the Maggie was the first he had had in six months and he treasured it accordingly. For this reason he and Gibney had been inclined to take considerable slack from Captain Scraggs until McGuffey discovered that, in all probability, no engineer in the world, except himself, would have the courage to trust himself within range of the Maggie's boilers, and, consequently, he had Captain Scraggs more or less at his mercy. Upon imparting this suspicion to Mr. Gibney, the latter decided that it would be a cold day, indeed, when his ticket would not constitute a club wherewith to make Scraggs, as Gibney expressed it, "mind his P's and Q's."

It will be seen, therefore, that mutual necessity held this queerly assorted trio together, and, though they quarrelled furiously, nevertheless, with the passage of time their own weaknesses and those of the Maggie had aroused in each for the other a curious affection. While Captain Scraggs frequently "pulled" a monumental bluff and threatened to dismiss both Gibney and McGuffey—and, in fact, occasionally went so far as to order them off his ship, on their part Gibney and McGuffey were wont to work the same racket and resign. With the subsidence of their anger and the return to reason, however, the trio had a habit of meeting accidentally in the Bowhead saloon, where, sooner or later, they were certain to bury their grudge in a foaming beaker of steam beer, and return joyfully to the Maggie.

Of all the little ship's company, Neils Halvorsen, colloquially designated as "The Squarehead," was the only individual who was, in truth and in fact, his own man. Neils was steady, industrious, faithful, capable, and reliable; any one of a hundred deckhand jobs were ever open to Neils, yet, for some reason best known to himself, he preferred to stick by the Maggie. In his dull way it is probable that he was fascinated by the agile intelligence of Mr. Gibney, the vitriolic tongue of Captain Scraggs, and the elephantine wit and grizzly bear courage of Mr. McGuffey. At any rate, he delighted in hearing them snarl and wrangle.

However, to return to the Maggie which we left entering the tule fog a few miles north of Pilar Point:

Captain Scraggs and The Squarehead partook first of the ham and eggs, coffee and bread which the skipper prepared. Scraggs then prepared a similar meal for Mr. Gibney and McGuffey, set it in the oven to keep warm, and descended to the engine room to relieve McGuffey for dinner. Neils at the same time took the course from Mr. Gibney and relieved the latter at the wheel. By this time, darkness had descended upon the world, and the Maggie had entered the fog; following her custom she proceeded in absolute silence, although as a partial offset to the extreme liability to collision with other coastwise craft, due to the non-whistling rule aboard the Maggie, Mr. Gibney had laid a course half a mile inside the usual steamer lanes, albeit due to his overwhelming desire for peace he had neglected to inform his owner of this; the honest fellow proceeded upon the hypothesis that what people do not know is not apt to trouble them.

Mr. McGuffey was already seated and disposing of his meal when Mr. Gibney entered. "Gib," he declared with his mouth full, "rinse the taste o' chewin' tobacco out o' your mouth before startin' to eat, an' then tell me, as man to man, if them eggs is fit for human consumption."

Mr. Gibney conformed with the engineer's request. "Eatable but venerable," was his verdict. "That infernal Scraggs is tryin' to make the Maggie pay dividends at the expense of our stomachs."

"And at the risk of our lives, Gib. I move we declare a strike until Scraggs digs up the money to overhaul the boiler. Just before we slipped into the fog I saw two steam schooners headed south—so they must 'a' seen us headed north. Jes' listen at them a-bellerin' off there to port. They're a-watchin' and a-listenin', expectin' to cut us down at every turn o' the screw. First thing you know, Gib, you'll be losin' your ticket for failin' to be courteous on the high seas."

"Six o' one an' half a dozen o' the other, Bart. If I whistle I'll use up all your steam, an', then if we should find ourselves in the danger zone we won't be able to get out of our own way."

"Let's refuse to take her out again until Scraggsy spends some money on her. 'Tain't Christian the way he acts."

"Got to get in another pay day before I start the high an' mighty, Bart. But I'll speak to the old man about them eggs. They taste like they'd been laid by a pelican before the Civil War. Somehow I can't eat an egg that's the least bit rotten."

"It's gettin' so," McGuffey mourned, "that I don't have no more time off in port. When I ain't standin' by I'm repairin', an' when I ain't doin' either I'm dreamin' about the danged old coffee mill. For a cancelled postage stamp I'd jump the ship."

He gulped down his coffee, loaded his pipe, and went below to relieve Scraggs, for although experience in acting as McGuffey's relief had given Captain Scraggs what might be termed a working knowledge of the Maggie's engine, McGuffey was never happy with Scraggs in charge, even for five minutes. The habit of years caused him to cast a quick glance at the steam gauge, and he noted it had dropped five pounds.

"Savin' on the coal again," he roared. "Git out o' my engine room, you doggoned skinflint." He seized a slice bar, threw open the furnace door, raked the fire, and commenced shovelling in coal at a rate that almost brought the tears of anguish to his owner's eyes. "There! The main bearin's screamin' again," he wailed. "Oil cup's empty. Ain't I drilled it into your head enough, Scraggsy, that she'll cry her eyes out if you don't let her swim in oil?" He grasped the oil can and, in order to test the efficacy of its squirt, shot a generous stream down Captain Scraggs's collar.

"That for them rotten eggs, you miser," he growled. "Heraus mit 'em!"

Captain Scraggs fled, cursing, and sought solace in the pilot house.

"It's as black," quoted Mr. Gibney as he entered, "as the Earl of Hell's riding boots."

"And as thick," snarled Scraggs, "as McGuffey's head. Lordy me, Gib, but it's thick. You'd think every bloomin' steam pipe in the universe had busted."

"If they was all like the Maggie's," Mr. Gibney retorted drily, "we wouldn't need to worry none. Not wishin' to change the conversation, Scraggsy, but referrin' to them eggs you slipped me and Bart for supper, all I gotta say is that the next time you go marketin' in ancient Egypt, me an' Mac's goin' to tell the real story o' the S.S. Maggie to the Inspectors. Now, that goes. Scatter along aft, Scraggs, and let me know what that taffrail log has to say about it."

Captain Scraggs read the log and reported the mileage to Mr. Gibney, who figured with the stub of a pencil on the pilot house wall, wagged his head, and appeared satisfied. "Better go for'd," he ordered, "an' help The Squarehead on the lookout. At eight o'clock we ought to be right under the lee o' Point San Pedro; when I whistle we ought to catch the echo thrown back by the cliff. Listen for it."

Promptly at eight o'clock, Mr. McGuffey was horrified to see his steam gauge drop half a pound as the Maggie's siren sounded. Mr. Gibney stuck his ingenious head out of the pilot house and listened, but no answering echo reached his ears. "Hear anything?" he bawled.

"Heard the Maggie's siren," Captain Scraggs retorted venomously.

Mr. Gibney leaped out on deck, selected a small head of cabbage from a broken crate and hurled it forward. Then he sprang back into the pilot house and straightened the Maggie on her course again. He leaned over the binnacle, with the cuff of his watch coat wiping away the moisture on the glass, and studied the instrument carefully. "I don't trust the danged thing," he muttered. "Guess I'll haul her off a coupler points an' try the whistle again."

He did. Still no echo. He was inclined to believe that Captain Scraggs had not read the taffrail log correctly, and when at eight-thirty he tried the whistle again he was still without results in the way of an echo from the cliff, albeit the engine room howler brought him several of a profuse character from the perspiring McGuffey.

"We've passed Pedro," Mr. Gibney decided. He ground his cud and muttered ugly things to himself, for his dead reckoning had gone astray and he was worried. The fog, if anything, was thicker than ever. He could not even make out the phosphorescent water that curled out from the Maggie's forefoot.

Time passed. Suddenly Mr. Gibney thrilled electrically to a shrill yip from Captain Scraggs.

"What's that?" Mr. Gibney bawled.

"I dunno. Sounds like the surf, Gib."

"Ain't you been on this run long enough to know that the surf don't sound like nothin' else in life but breakers?" Gibney retorted wrathfully.

"I ain't certain, Gib."

Instantly Gibney signalled McGuffey for half speed ahead.

"Breakers on the starboard bow," yelled Captain Scraggs.

"Port bow," The Squarehead corrected him.

"Oh, my great patience!" Mr. Gibney groaned. "They're on both bows an' we're headed straight for the beach. Here's where we all go to hell together," and he yanked wildly at the signal wire that led to the engine room, with the intention of giving McGuffey four bells—the signal aboard the Maggie for full speed astern. At the second jerk the wire broke, but not until two bells had sounded in the engine room—the signal for full speed ahead. The efficient McGuffey promptly kicked her wide open, and the Fates decreed that, having done so, Mr. McGuffey should forthwith climb the ladder and thrust his head out on deck for a breath of fresh air. Instantly a chorus of shrieks up on the fo'castle head attracted his attention to such a degree that he failed to hear the engine room howler as Mr. Gibney blew frantically into it.

Presently, out of the hubbub forward, Mr. McGuffey heard Captain Scraggs wail frantically: "Stop her! For the love of heaven, stop her!" Instantly the engineer dropped back into the engine room and set the Maggie full speed astern; then he grasped the howler and held it to his ear.

"Stop her!" he heard Gibney shriek. "Why in blazes don't you stop her?"

"She's set astern, Gib. She'll ease up in a minute."

"You know it," Gibney answered significantly.

The Maggie climbed lazily to the crest of a long oily roller, slid recklessly down the other side, and took the following sea over her taffrail. She still had some head on, but very little—not quite sufficient to give her decent steerage way, as Mr. Gibney discovered when, having at length communicated his desires to McGuffey, he spun the wheel frantically in a belated effort to swing the Maggie's dirty nose out to sea.

"Nothin' doin'," he snarled. "She'll have to come to a complete stop before she begins to walk backward and get steerage way on again. She'll bump as sure as death an' taxes."

She did—with a crack that shook the rigging and caused it to rattle like buckshot in a pan. A terrible cry—such a cry, indeed, as might burst from the lips of a mother seeing her only child run down by the Limited—burst from poor Captain Scraggs. "My ship! my ship!" he howled. "My darling little Maggie! They've killed you, they've killed you! The dirty lubbers!"

The succeeding wave lifted the Maggie off the beach, carried her in some fifty feet further, and deposited her gently on the sand. She heeled over to port a little and rested there as if she was very, very weary, nor could all the threshing of her screw in reverse haul her off again. The surf, dashing in under her fantail, had more power than McGuffey's engines, and, foot by foot, the Maggie proceeded to dig herself in. Mr. Gibney listened for five minutes to the uproar that rose from the bowels of the little steamer before he whistled up Mr. McGuffey.

"Kill her, kill her," he ordered. "Your wheel will bite into the sand first thing you know, and tear the stern off her. You're shakin' the old girl to pieces."

McGuffey killed his engine, banked his fires, and came up on deck, wiping his anxious face with a fearfully filthy sweat rag. At the same time, Scraggs and Neils Halvorsen came crawling aft over the deckload and when they reached the clear space around the pilot house, Captain Scraggs threw his brown derby on the deck and leaped upon it until, his rage abating ultimately, no power on earth, in the air, or under the sea, could possibly have rehabilitated it and rendered it fit for further wear, even by Captain Scraggs. This petulant practice of jumping on his hat was a habit with Scraggs whenever anything annoyed him particularly and was always infallible evidence that a simple declarative sentence had stuck in his throat.

"Well, old whirling dervish," Mr. Gibney demanded calmly when Scraggs paused for lack of breath to continue his dance, "what about it? We're up Salt Creek without a paddle; all hell to pay and no pitch hot."

"McGuffey's fired!" Captain Scraggs screeched.

"Come, come, Scraggsy, old tarpot," Mr. Gibney soothed. "This ain't no time for fightin'. Thinkin' an' actin' is all that saves the Maggie now."

But Captain Scraggs was beyond reason. "McGuffey's fired! McGuffey's fired!" he reiterated. "The dirty rotten wharf rat! Call yourself an engineer?" he continued, witheringly. "As an engineer you're a howling success at shoemakin', you slob. I'll fix your clock for you, my hearty. I'll have your ticket took away from you, an' that's no Chinaman's dream, nuther."

"It's all my fault runnin' by dead reckonin'," the honest Gibney protested. "Mac ain't to fault. The engine room telegraph busted an' he got the wrong signal."

"It's his business to see to it that he's got an engine room telegraph that won't bust——"

"You dog!" McGuffey roared and sprang at the skipper, who leaped nimbly up the little ladder to the top of the pilot house and stood prepared to kick Mr. McGuffey in the face should that worthy venture up after him. "I can't persuade you to git me nothin' that I ought to have. I'm tired workin' with junk an' scraps an' copper wire and pieces o' string. I'm through!"

"You're right—you're through, because you're fired!" Scraggs shrieked in insane rage. "Get off my ship, you maritime impostor, or I'll take a pistol to you. Overboard with you, you greasy, addlepated bounder! You're rotten, understand? Rotten! Rotten! Rotten!"

"You owe me eight dollars an' six bits, Scraggs," Mr. McGuffey reminded his owner calmly. "Chuck down the spondulicks an' I'll get off your ship."

Captain Scraggs was beyond reason, so he tossed the money down to the engineer. "Now git," he commanded.

Without further ado, Mr. McGuffey started across the deckload to the fo'castle head. Scraggs could not see him but he could hear him—so he pelted the engineer with potatoes, cabbage heads, and onions, the vegetables descending about the honest McGuffey in a veritable barrage. Even in the darkness several of these missiles took effect.

Upon reaching the very apex of the Maggie's bow, Mr. McGuffey turned and hurled a promise into the darkness: "If we ever meet again, Scraggs, I'll make Mrs. Scraggs a widow. Paste that in your hat—when you get a new one."

The Maggie was resting easily on the beach, with the broken water from the long lazy combers surging well up above her water line. At most, six feet of water awaited the engineer, who stood, peering shoreward and listening intently, oblivious to the stray missiles which whizzed past. Presently, from out of the fog, he heard a grinding, metallic sound and through a sudden rift in the fog caught a brief glimpse of blue flame with sparks radiating faintly from it.

That settled matters for Bartholomew McGuffey. The metallic sound was the protest from the wheels of a Cliff House trolley car rounding a curve; the blue flame was an electric manifestation due to the intermittent contact of her trolley with the wire, wet with fog. McGuffey knew the exact position of the Maggie now, so he poised a moment on her bow; as a wave swept past him, he leaped overboard, scrambled ashore, made his way up the beach to the Great Highway which flanks the shore line between the Cliff House and Ingleside, sought a roadhouse, and warmed his interior with four fingers of whiskey neat. Then, feeling quite content with himself, even in his wet garments, he boarded a city-bound trolley car and departed for the warmth and hospitality of Scab Johnny's sailor boarding house in Oregon Street.

Captain Scraggs continued to hurl other people's vegetables into the murk forward for at least two minutes after Mr. McGuffey had shaken the coal dust of the Maggie from his feet, and was only recalled to more practical affairs by the bored voice of Mr. Gibney.

"The owners o' them artichokes expect to get half a dollar apiece for 'em in New York, Scraggsy. Cut it out, old timer, or you'll have a claim for a freight shortage chalked up agin you."

"Nothin' matters any more," Scraggs replied in a choked voice, and immediately sat down on the half-emptied crate of artichokes and commenced to weep bitterly—half because of rage and half because he regarded himself a pauper. Already he had a vision of himself scouring the waterfront in search of a job.

"No use boo-hooin' over spilt milk, Scraggsy." Always philosophical, the author of the owner's woe sought to carry the disaster off lightly. "Don't add your salt tears to a saltier sea until you're certain you're a total loss an' no insurance. I got you into this and I suppose it's up to me to get you off, so I guess I'll commence operations." Suiting the action to the word, Mr. Gibney grasped the whistle cord and a strange, sad, sneezing, wheezy moan resembling the expiring protest of a lusty pig and gradually increasing into a long-drawn but respectable whistle rewarded his efforts. For once, he could afford to be prodigal with the steam, and while it lasted there could be no mistaking the fact that here was a steamer in dire distress.

The weird call for help brought Scraggs around to a fuller realization of the enormity of the disaster which had overtaken him. In his agony, he forgot to curse his navigating officer for the latter's stubbornness in refusing to turn back when the fog threatened. He clutched Mr. Gibney by the right arm, thereby interrupting for an instant the dismal outburst from the Maggie's siren.

"Gib," he moaned, "I'm a ruined man. How're we ever to get the old sweetheart off whole? Answer me that, Gib. Answer me, I say. How're we to get my Maggie off the beach?"

Mr. Gibney shook himself loose from that frantic grip and continued his pull on the whistle until the Maggie, taking a false note, quavered, moaned, spat steam a minute, and subsided with what might be termed a nautical sob. "Now see what you've done," he bawled. "You've made me bust the whistle."

"Answer my question, Gib."

"We'll never get her off if you don't quit interferin' an' give me time to think. I'll admit there ain't much of a chance, because it's dead low water now an' just as soon as the tide is at the flood she'll drive further up the beach an' fall apart."

"Perhaps McGuffey will have heart enough to telephone into the city for a tug."

"'Tain't scarcely probable, Scraggsy. You abused him vile an' threw a lot of fodder at him."

"I wish I'd been took with paralysis first," Scraggs wailed bitterly. "You'd best jump ashore, Gib, an' 'phone in. We're just below the Cliff House and you can run up to one o' them beach resorts an' 'phone in to the Red Stack Tug Boat Company."

"'Twouldn't be ethics for me, the registered master o' the Maggie, to desert the ship, Scraggsy, old stick-in-the-mud. What's the matter with gettin' your own shanks wet?"

"I dassen't, Gib. I've had a touch of chills an' fever ever since I used to run mate up the San Joaquin sloughs. Here's a nickel to drop in the telephone slot, Gib. There's a good fellow."

"Scraggsy, you're deludin' yourself. Show me a tugboat skipper that would come out here on a night like this to pick up the S.S. Maggie, two decks an' no bottom an' loaded with garden truck, an' I'll wag my ears an' look at the back o' my neck. She ain't worth it."

"Ain't worth it! Why, man, I paid fifteen hundred hard cash dollars for her."

"Fourteen hundred an' ninety-nine dollars an' ninety-nine cents too much. They seen you comin'. However, grantin' for the sake of argyment that she's worth the tow, the next question them towboat skippers'll ask is: 'Who's goin' to pay the bill?' It'll be two hundred an' fifty dollars at the lowest figger, an' if you got that much credit with the towboat company you're some high financier. Ain't that logic?"

"I'm afraid," Scraggs replied sadly, "it is. Still, they'd have a lien on the Maggie——"

"Steamer ahoy!" came a voice from the beach.

"Man with a megaphone," Mr. Gibney cried. "Ahoy! Ahoy, there!"

"Who are you an' what's the trouble?"

Captain Scraggs took it upon himself to answer: "American steamer Mag——"

Mr. Gibney sprang upon him tigerishly, placed a horny, tobacco-smelling palm across Scraggs's mouth and effectively smothered all further sound. "American steamer Yankee Prince," he bawled like a veritable Bull of Bashan, "of Boston, Hong Kong to Frisco with a general cargo of sandal wood, rice, an' silk. Where're we at?"

"Just outside the Gate. Half a mile south o' the Cliff House."

"Telephone in for a tug. We're in nice shape, restin' easy, but our rudder's gone an' the after web o' the crank shaft's busted. Telephone in, my man, an' I'll make it up to you when we get to a safe anchorage. Who are you?"

"Lindstrom, of the Golden Gate Life Saving Station."

"I'll not forget you, Lindstrom. My owners are Yankees, but they're sports."

"All right. I'll telephone. On my way!"

"God speed you," murmured Mr. Gibney, and released his hold on Captain Scraggs, who instantly threw his arms around the navigating officer's burly neck. "I forgive you, Adelbert," he crooned. "I forgive you freely. By the tail of the Great Sacred Bull, you're a marvel. She's an all-night fog or I'm a Chinaman, and if it only stays thick enough——"

"It'll hold," Gibney retorted doggedly. "It's a tule fog. They always hold. Quit huggin' me. Your breath's bad. Them eggs, I guess."

Captain Scraggs, hurled forcibly backward, bumped into the pilot house, but lost none of his enthusiasm. "You're a jewel," he declared. "Oh, man, what a head! Whatever made you think of the Yankee Prince?"

"Because," Mr. Gibney answered calmly, "there ain't no such ship, this land of ours bein' a free republic where princes don't grow. Still, it's a nice name, Scraggs, old tarpot—more particular since I thought it up in a hurry. Eh, what?"

"Halvorsen," cried Captain Scraggs.

The lone deckhand emerged from a hole in the freight forward whither he had retreated to escape the vegetable barrage put over by Captain Scraggs when McGuffey left the ship. "Aye, aye, sir," he boomed.

"All hands below to the galley!" Scraggs shouted. "While we're waitin' for this here towboat I'll brew a scuttle o' grog to celebrate the discovery o' real seafarin' talent. Gib, my dear boy, I'm proud of you. No matter what happens, I'll never have no other navigatin' officer."

"Don't crow till you're out o' the woods," the astute Gibney warned him.

In the office of the Red Stack Tug Boat Company, Captain Dan Hicks, master of the tug Aphrodite; Captain Jack Flaherty, master of the Bodega, and Tiernan, the assistant superintendent on night watch, sat around a hot little box stove engaged in that occupation so dear to the maritime heart, to-wit: spinning yarns. Dan Hicks had the floor, and was relating a tale that had to do with his life as a freight and passenger skipper.

"We was makin' up to the dock when I see the general agent standin' in the door o' the dock office—an' all of a sudden I didn't feel so chipper about havin' crossed Humboldt bar in a sou'easter. I saw the old man runnin' his eye along forty foot o' twisted pipe railin', a wrecked bridge, three bent stanchions an' every door an' window on the starboard side o' the ship stove in, while the passengers crowded the rail lookin' cold an' miserable, pea-green an' thankful. No need for me to do any explainin'. He knew. He throws his dead fish eye up to me on what's left o' the bridge an' I felt my job was vacant.

"'We was hit by a sea or two on Humboldt bar, sir,' I says, as if gettin' hit by a sea or two an' havin' the ship gutted was an every-day experience."

"'Is that so, Hicks?' says he sweetly. 'Well, now, if you hadn't told me that I'd ha' jumped to the conclusion that a couple o' the mess boys had got fightin' an' wrecked the ship before you could separate 'em. Why in this an' that,' he says, 'didn't you stick inside when any dumb fool could see the bar was breakin'?'

"'I wanted to keep the comp'ny's sailin' schedule unbroken, sir,' I says, tryin' to be funny.

"'Well, Captain,' he says, 'it 'pears to me you've broken damned near everything else tryin' to do it.'

"I was certain he was goin' to set me down, but the worst I got was a three months' lay-off to teach me common sense——"

The telephone rang and Tiernan answered. Hicks and Flaherty hitched forward in their chairs to listen.

"Hello.... Yes, Red Stack office.... Steamer Yankee Prince.... What's that?... silk and rice?... Half a mile below the Cliff House, eh?... Sure, I'll send a tug right away, Lindstrom."

Tiernan hung up and faced the two skippers. "Gentlemen," he announced, "here's a chance for a little salvage money to-night. The American steamer Yankee Prince is ashore half a mile below the Cliff House. She's a big tramp with a valuable cargo from Hong Kong, with her rudder gone and her crank shaft busted."

"It's high water at twelve thirty-seven," Jack Flaherty pleaded. "You'd better send me, Tiernan. The Bodega has more power than the Aphrodite."

This was the truth and Dan Hicks knew it, but he was not to be beaten out of his share of the salvage by such flimsy argument. "Jack," he pleaded, "don't be a hog all the time. The Yankee Prince is an eight thousand ton vessel and it's a two-tug job. Better send us both, Tiernan, and play safe. Chances are our competitors have three tugs on the way right now."

"What a wonderful imagination you have, Dan. Eight thousand tons! You're crazy, man. She's thirteen hundred net register and I know it because I was in Newport News when they launched her, and I went out with her skipper on the trial trip. She's a long, narrow-gutted craft, with engines aft, like a lake steamer."

"We'll play safe," Tiernan decided. "Go to it—both of you, and may the best man win. She'll belong to you, Jack, if she's thirteen hundred net and you get your line aboard first. If she's as big as Dan says she is, you'll be equal partners——"

But he was talking to himself. Down the dock Hicks and Flaherty were racing for the respective commands, each shouting to his night watchman to pipe all hands on deck. Fortunately, a goodly head of steam was up in each tug's boilers; because of the fog and the liability to collisions and a consequent hasty summons, one engineer on each tug was on duty. Before Hicks and Flaherty were in their respective pilot houses the oil burners were roaring lustily under their respective boilers; the lines were cast off within a minute of each other, and the two tugs raced down the bay through the darkness and fog.

Both Hicks and Flaherty had grown old in the towboat service and the rules of the road rested lightly on their sordid souls. They were going over a course they knew by heart—wherefore the fog had no terrors for them. Down the bay they raced, the Bodega leading slightly, both tugs whistling at half-minute intervals. Out through the Gate they nosed their way, heaving the lead continuously, made a wide detour around Mile Rock and the Seal Rocks, swung a mile to the south of the position of the Maggie, and then came cautiously up the coast, whistling continuously to acquaint the Yankee Prince with their presence in the neighbourhood. In anticipation of the necessity for replying to this welcome sound, Captain Scraggs and Mr. Gibney had, for the past two hours, busied themselves getting up another head of steam in the Maggie's boilers, repairing the whistle, and splicing the wires of the engine room telegraph. Like the wise men they were, however, they declined to sound the Maggie's siren until the tugs were quite close. Even then, Mr. Gibney shuddered, but needs must when the devil drives, so he pulled the whistle cord and was rewarded with a weird, mournful grunt, dying away into a gasp.

"Sounds like she has the pip," Jack Flaherty remarked to his mate.

"Must have taken on some of that dirty Asiatic water," Dan Hicks soliloquized, "and now her tubes have gone to glory."

Immediately, both tugs kicked ahead under a dead slow bell, guided by a series of toots as brief as Mr. Gibney could make them, and presently both tug lookouts reported breakers dead ahead; whereupon Jack Flaherty got out his largest megaphone and bellowed: "Yankee Prince, ahoy!" in his most approved fashion. Dan Hicks did likewise. This irritated the avaricious Flaherty, so he turned his megaphone in the direction of his rival and begged him, if he still retained any of the instincts of a seaman, to shut up; to which entreaty Dan Hicks replied with an acidulous query as to whether or not Jack Flaherty thought he owned the sea.

For half a minute this mild repartee continued, to be interrupted presently by a whoop from out of the fog. It was Mr. Gibney. He did not possess a megaphone so he had gone below and appropriated a section of stove-pipe from the galley range, formed a mouthpiece of cardboard and produced a makeshift that suited his purpose admirably.

"Cut out that bickerin' like a pair of old women an' 'tend to your business," he commanded. "Get busy there—both of you, and shoot a line aboard. There's work enough for two."

Dan Hicks sent a man forward to heave the lead under the nose of the Aphrodite, which was edging in gingerly toward the voice. He had a searchlight but he did not attempt to use it, knowing full well that in such a fog it would be of no avail. Guided, therefore, by the bellowings of Mr. Gibney, reinforced by the shrill yips of Captain Scraggs, the tug crept in closer and closer, and when it seemed that they must be within a hundred feet of the surf, Dan Hicks trained his Lyle gun in the direction of Mr. Gibney's voice and shot a heaving line into the fog.

Almost simultaneous with the report of the gun came a shriek of pain from Captain Scraggs. Straight and true the wet, heavy knotted end of the heaving line came in over the Maggie's quarter and struck him in the mouth. In the darkness he staggered back from the stinging blow, clutched wildly at the air, slipped and rolled over among the vegetables with the precious rope clasped to his breast.

"I got it," he sputtered, "I got it, Gib."

"Safe, O!" Mr. Gibney bawled. "Pay out your hawser."

They met it at the taffrail as it came up out of the breakers, wet but welcome. "Pass it around the mainmast, Scraggsy," Mr. Gibney cautioned. "If we make fast to the towin' bits, the first jerk'll pull the anchor bolts up through the deck."

When the hawser had been made fast to the mainmast, the leathern lungs of Mr. Gibney made due announcement of the fact to the expectant Captain Hicks. "As soon as you feel you've got a grip on her," he yelled, "just hold her steady so she won't drive further up the beach when I get my anchor up. She'll come out like a loose tooth at the tip of the flood."

The Aphrodite forged slowly ahead, taking in the slack of the hawser. Ten minutes passed but still the hawser lay limp across the Maggie's stern. Presently out of the fog came the voice of Captain Dan Hicks.

"Flaherty! Flaher-tee! For the love of life, Jack, where are you? Chuck me a line, Jack. My hawser's snarled in my screw and I'm drifting on to the beach."

"Leggo your anchor, you boob," Jack Flaherty advised.

"I want a line an' none o' your damned advice," raved Hicks.

"'Tain't my fault if you get in too close."

"I'm bumping, Jack. I'm bangin' the heart out of her. Come on, you cur, and haul me off."

"If I pull you off, Dan Hicks, will you leave that steamer alone? You've had your chance and failed to smother it. Now let me have a hack at her."

"It's a bargain, Jack. I'm not badly snarled; if you haul me out to deep water I can shake the hawser loose. I'm afraid to try so close in."

"Comin'," yelled Flaherty.

"Now, ain't that a raw deal?" Scraggs complained. "That junk thief gets hauled off first."

"The first shall be last an' the last shall be first," Gibney quoted piously. "Don't be a crab, Scraggs. Pray that the fog don't lift."

Out of the fog there rose a great hubbub of engine room gongs, the banging of the Bodega's Lyle gun, and much profanity. Presently this ceased, so Scraggs and Gibney knew Dan Hicks was being hauled off at last. While they waited for further developments, Scraggs sucked at his old pipe and Mr. Gibney munched a French carrot. "If you hadn't canned McGuffey," the latter opined, "we might have been able to back off under our own power as soon as the tide is at flood. This delay is worryin' me."

Following some fifteen minutes of kicking and struggling out in the deep water, whither the Bodega had dragged her, the Aphrodite at length freed herself of the clinging hawser; whereupon she backed in again, cautiously reeving in the hawser as she came. Presently, Dan Hicks, true to his promise to abandon the prize to Jack Flaherty, turned his megaphone beachward and shouted:

"Yankee Prince, ahoy! Cast off my hawser. The other tug will put a line aboard you."

But Mr. Gibney was now master of the situation. He had a good hemp hawser stretching between him and salvation and until he should be hauled off he had no intention of slipping that cable. "Nothin' doin'," he answered. "We're hard an' fast, I tell you, and I'll take no chances. It's you or both of you, but I'll not cast off this hawser. If you want to let go, cast the hawser off at your end." Sotto voce he remarked to Scraggs: "I see him slippin' a three hundred dollar hawser, eh, Scraggsy, old stick-in-the-mud?"

"But I promised Flaherty I'd let you alone," pleaded Hicks.

"What do you think you have your string fast to, anyhow? A bay scow? If you fellows endanger my ship bickerin' over the salvage I'll have you before the Inspectors on charges as sure as God made little apples. I got sixty witnesses here to back up my charges, too."

"You hear him, Jack?" howled Hicks.

"Wouldn't that swab Flaherty drive you to drink," Gibney complained. "Trumpin' his partner's ace just for the glory an' profit o' gettin' ahead of him?" Aloud he addressed the invisible Flaherty: "Take it or leave it, brother Flaherty."

"I'll take it," Flaherty responded promptly.

Twenty minutes later, after much backing and swearing and heaving of lines the Bodega's hawser was finally put board the Maggie. Mr. Gibney judged it would be safe now to fasten this line to the towing bitts.

Suddenly, Captain Scraggs remembered there was no one on duty in the Maggie's engine room. With a half sob, he slid down the greasy ladder, tore open the furnace doors and commenced shovelling in coal with a recklessness that bordered on insanity. When the indicator showed eighty pounds of steam he came up on deck and discovered Mr. Gibney walking solemnly round and round the little capstan up forward. It was creaking and groaning dismally. Captain Scraggs thrust his engine room torch above his head to light the scene and gazed upon his navigating officer in blank amazement.

"What foolishness is this, Gib?" he demanded. "Are you clean daffy, doin' a barn dance around that rusty capstan, makin' a noise fit to frighten the fish?"

"Not much," came the laconic reply. "I'm a smart man. I'm raisin' both anchors."

"Well, all I got to remark is that it takes a smart man to raise both anchors when we only got one anchor to our blessed name. An' with that anchor safe on the fo'castle head, I, for one, can't see no sense in raisin' it."

"You tarnation jackass!" sighed Gibney. "You forget who we are. Do you s'pose the steamer Yankee Prince can lay on the beach all night with both anchors out, an' then be got ready to tow off in three shakes of a lamb's tail? It takes noise to get up two anchors—so I'm makin' all the noise I can. Got any steam?"

"Eighty pounds," Scraggs confessed. Having for the moment forgotten his identity, he was confused in the presence of the superior intelligence of his navigating officer.

"Run aft, then, Scraggs, an' turn that cargo winch over to beat the band until I tell you to stop. With the drum runnin' free she'll make noise enough for a winch three times her size, but you might give the necessary yells to make it more lifelike."

Captain Scraggs fled to the winch. At the end of five minutes, Mr. Gibney appeared and bade him desist. Then, turning, his improvised megaphone seaward he addressed an imaginary mate: "Mr. Thompson, have you got your port anchor up?"

Scraggs took the cue immediately. "All clear forward, sir," he piped.

"Send the bosun for'd an' heave the lead, Mr. Thompson."

"Very well, sir."

Here The Squarehead, who had been enjoying the unique situation immensely, decided to take a hand. Presently, in sing-song cadence he was reporting the depth of water alongside.

"That'll do, bosun," Gibney thundered. Then, in his natural voice to Scraggs: "All set, Scraggsy. Guess we're ready to be pulled off. Get down in the engine room and stand by for full speed ahead when I give the word."

"Quick! Hurry!" Scraggs entreated as he disappeared through the little engine-room hatch, for the tide was now at the tip of the flood and the Maggie was bumping wickedly and driving further up the beach. Mr. Gibney turned his stovepipe seaward and shouted: "Tugboats, ahoy!"

"Ahoy!" they answered in unison.

"All read-y-y-y! Let 'er go-o-o-o!"

The Squarehead stationed himself at the bitts with a lantern and Mr. Gibney hastened to the pilot house and took his place at the wheel. When the hawsers commence to lift out of the sea, The Squarehead gave a warning shout, whereupon Mr. Gibney called the engine room. "Give her the gun," he commanded Scraggs. "Pull against them tugs for all you're worth. Remember this is the steamer Yankee Prince. We must not come off too readily."

Captain Scraggs opened the throttle, and while the two tugs steadily drew her off into deep water, the Maggie fought valiantly to stick to the beach and even to continue her interrupted journey overland. She merely succeeded in stretching both hawsers taut; slowly she was drawn seaward, stern first, and at the expiration of fifteen minutes' steady pulling, Mr. Gibney could restrain himself no longer. He rang for full speed astern—and got it promptly. Then, calling Neils Halvorsen to aid him, he abandoned the wheel and scrambled aft.

With no one at the wheel the Maggie shot off at a tangent and the hawsers slacked immediately. In the twinkling of an eye Mr. Gibney had cast them off, and as the ends disappeared with a swish over the stern he ran back to the pilot house, rang for full speed ahead, put his helm hard over, and headed the Maggie in the general direction of China, although as a matter of fact he cared not what direction he pursued, provided he got away from the beach and placed distance between the Maggie and two soon-to-be-furious tugboat skippers.

As the Maggie chugged blithely away, the navigating officer's soul expanded in song, and in the voice of a bull walrus he delivered himself of a deep sea chantey more popular than proper.

Presently, away off in the fog, he heard the Bodega whistle. The Aphrodite answered immediately. Adelbert P. Gibney smiled and bit a large crescent out of his navy plug, for his soul was at peace. When The Squarehead came into the pilot house presently and grinned at him, Mr. Gibney handed Neils an electric torch. "Prowl around below in the old ruin, Neils," he commanded, "and see if we're makin' any water."

A quarter of an hour later Neils Halvorsen returned to report the Maggie apparently undamaged, so Mr. Gibney changed his course and headed stealthily in the direction of the whistling tugs. He came up behind them presently—approaching so close under cover of the fog that he could hear Dan Hicks and Jack Flaherty, both under a dead-slow bell, felicitating each other through their megaphones.

"Where d'ye suppose that dirty scoundrel's gone?" Hicks was demanding.

"Out to sea, of course," Flaherty bellowed. "He'll stand off until the fog lifts and then come ramping in as proud as Lucifer and look amazed when we send him in a bill."

"Bill!" Hicks' voice dripped with sarcasm. "The Red Stack Company will libel him, and if the old man doesn't, me an' my crew will."

"I'll bet a ripe peach he's a Jap, with a scoundrelly white skipper and white mates. They'll all stick together for a five-dollar bill and swear they never was on the beach at all. If they do, how're we goin' to prove it?"

"That's logic," the eavesdropping Gibney murmured to the binnacle.

"Oh, hell's bells, shut up and let's go home," Dan Hicks cried wearily. "We can catch him when he comes in."

"Suppose he doesn't come in. Suppose he's bound for Seattle, Dan."

"We can libel him wherever he goes."

"I'll bet he gave us a fictitious name, Dan!"

"Stow that grief, Jack. Stow it, or I'll go mad. The Bodega has more speed than the Aphrodite, so poke ahead there and let's try to get in an hour's sleep before daylight. If you can't feel your way in I can."

"I'll just tag along silent and lazy-like after you two misfortunates," Mr. Gibney decided, "an' you'll do my whistlin' for me." He called Scraggs on the howler and explained the situation. "Regular Cook's tour," he exulted. "Personally conducted. Off again, on again, away again, Finnegan—and not a nickel's worth of loss unless you count them vegetables you hove at McGuffey. Ain't you proud o' your navigatin' officer, Scraggsy, old tarpot?"

"I am, Gib, but I'll be prouder'n ever if you can follow them towboats in without havin' to claw off Baker's beach or the Point Bonita rocks."

"Calamity howler," Gibney growled. Half an hour later he caught the echo of the Bodega's whistle as the sound was hurled back from the high cliffs at Land's End, off to starboard. A minute later he heard the hoarse growl of the siren from the fog station on Point Bonita, on the port beam. He knew where he was now with as much certainty as if he was navigating in broad daylight, so he loafed along a couple of hundred yards behind the Bodega, until the Maggie ceased pitching—when he knew he was in the still water inside the entrance. So he sheered over to starboard, with Neils Halvorsen heaving the lead, and dropped anchor in five fathoms under the lee of Fort Mason. He was quite confident of his ability to sneak along the waterfront and creep into the Maggie's berth at Jackson Street bulkhead, but having gone astray in his calculations once that night, a vagrant sense of consideration for Captain Scraggs decided him to take no more risks until the fog should lift. He could hear the Bodega and the Aphrodite tooting as they continued down the bay, so he knew they were headed for their berths at the foot of Broadway, fog or no fog.

When Captain Scraggs, having banked his fires, came up out of the engine room, Mr. Gibney laid a great paw paternally upon the skipper's shoulder. "Scraggsy, old salamander," he announced, "I think I've done enough to-night to entitle me to some sleep until this tule fog lifts. Am I right?"

"You certainly are, Gib, my dear boy."

"Very well, then. I'll turn in. As for you, old sailor, your night's work is not ended. Have The Squarehead row you ashore in the skiff; I'll stay up an' work the patent foghorn so he can find his way back to the Maggie, while you hike down town——"

"What for?" Scraggs demanded irritably. "I'm all wore out."

"This adventure ain't ended," Mr. Gibney warned him. "There's a witness to our perfidy still at large. His name is B. McGuffey, esquire, an' I'll lay you ten to one you'll find him asleep in Scab Johnny's boardin' house. Go to him, Scraggsy, an' bring a pint flask with you when you do; wake him up, beg his pardon, take him to breakfast, and promise him you'll do somethin' for his boilers. Old Mac's got a heart as tender as a infant's. You can win him over."

"Oh, Gib, use some common sense. Mac'll lay abed until noon. It stands to reason he'll have to, because he didn't take no change of clothin' with him, so he'll just naturally have to wait till his wet clothes get dry before venturin' forth an' spreadin' the news that the Maggie's on the beach. He doesn't know we're off, an' once we're tied up at the dock and we hear Mac's been talkin' we'll just spread the word that he was so soused he jumped overboard an' swum ashore without waitin' to see if we could back off. Lordy, Gib, don't work me to death. I'm that weary I could flop on this wet deck an' be off to sleep in a pig's whisper."

"I dunno but what there's reason in what you say," Mr. Gibney agreed. "Well, turn in, Scraggsy, but the minute we hit the dock you run up town and fix things up with Bart."

And without further ado he set the alarm clock for seven o'clock, kicked off his shoes, and climbed into his berth with his clothes on.

The crews of the Aphrodite and the Bodega slept late also, for they were weary, and fortunately, no calls for a tug came into the office of the Red Stack Company all morning. About ten o'clock Dan Hicks and Jack Flaherty breakfasted and about ten thirty both met in the office. Apparently they were two souls with but a single thought, for the right hand of each sought the shelf whereon reposed the blue volume entitled "Lloyd's Register." Dan Hicks reached it first, carried it to the counter, wet his tarry index finger, and started turning the pages in a vain search for the American steamer Yankee Prince. Presently he looked up at Jack Flaherty.

"Flaherty," he said, "I think you're a liar."

"The same to you and many of them," Flaherty replied, not a whit abashed. "You said she was an eight thousand ton tramp."

"I never went so far as to say I'd been aboard her on trial trip, though—and I did cut down her tonnage, showin' I got the fragments of a conscience left," Hicks defended himself.

He closed the book with a sigh and placed it back on the shelf, just as the door opened to admit no less a personage than Batholomew McGuffey, late chief engineer, first assistant, second assistant, third assistant, wiper, oiler, water-tender, and stoker of the S.S. Maggie. With a brief nod to Jack Flaherty Mr. McGuffey approached Dan Hicks.

"I been lookin' for you, captain," he announced. "Say, I hear the chief o' the Aphrodite's goin' to take a three months' lay-off to get shet of his rheumatism. Is that straight?"

"I believe it is, McGuffey."

"Well, say, I'd like to have a chance to substitoot for him. You know my capabilities, Hicks, an' if it would be agreeable to you to have me for your chief your recommendation would go a long way toward landin' me the job. I'd sure make them engines behave."

"What vessel have you been on lately?" Hicks demanded cautiously, for he knew Mr. McGuffey's reputation for non-reliability around pay-day.

"I been with that fresh water scavenger, Scraggs, in the Maggie for most a year."

"Did you quit or did Scraggs fire you?"

"He fired me," McGuffey replied honestly. "If he hadn't I'd have quit, so it's a toss-up. Comin' in from Halfmoon Bay last night we got lost in the fog an' piled up on the beach just below the Cliff House——"

"This is interesting," Jack Flaherty murmured. "You say she walked ashore on you, McGuffey? Well, I'll be shot!"

"She did. Scraggs blamed it on me, Flaherty. He said I didn't obey the signals from the bridge, one word led to another, an' he went dancin' mad an' ordered me off his ship. Well, it's his ship—or it was his ship, for I'll bet a dollar she's ground to powder by now—so all I could do was obey. I hopped overboard an' waded ashore. I suppose all my clothes an' things is gone by now. I left everything aboard an' had to borrow this outfit from Scab Johnny." He grinned pathetically. "So I guess you understand, Captain Hicks, just how bad I need that job I spoke about a minute ago."

"I'll think it over, Mac, an' let you know," Hicks replied evasively.

Mr. McGuffey, sensing his defeat, retired forthwith to hide his embarrassment and distress; as the door closed behind him, Hicks and Flaherty faced each other.

"Jack," quoth Dan Hicks, "can two towboat men, holdin' down two hundred-dollar jobs an' presumed to have been out o' their swaddlin' clothes for at least thirty years, afford to be laughed off the San Francisco waterfront?"

"I know one of them that can't, Dan. At the same time, can a rat like Phineas P. Scraggs and a beachcomber like his mate Gibney make a pair of star-spangled monkeys out of said two towboat men and get away with it?"

"They did that last night. Still, I've known monkeys that would fight an' was human enough to settle a grudge. Follow me, Jack."

Together they repaired to Jackson Street bulkhead. Sure enough there lay the Maggie, rubbing her blistered sides against the bulkhead. Captain Scraggs was nowhere in sight, but Mr. Gibney was at the winch, swinging ashore the crates of vegetables which The Squarehead and three longshoremen loaded into the cargo net.

"We're outnumbered," Jack Flaherty whispered.

"Let's wait until she's unloaded an' Gibney an' Scraggs are aboard alone."

They retired without having attracted the attention of Mr. Gibney, and a few minutes later, Captain Scraggs came down the bulkhead and sprang aboard.

"Well?" his navigating officer queried.

"Couldn't find him," Scraggs confessed. "Scab Johnny says he loaned Mac a dry outfit an' the old boy dug out for breakfast at seven o'clock an' ain't been around since."

"Did you try the saloons, Scraggsy?"

"I did. Likewise the cigar stands an' restaurants, an' the readin' rooms of the Marine Engineers' Association."

"Guess he's out hustlin' a job," Mr. Gibney sighed. He was filled with vague forebodings of evil. "If you'd only listened to my advice last night, Scraggsy—if you'd only listened," he mourned.

"We'll cross our bridges when we come to them, Gib. Cheer up, my boy, cheer up. I got a new engineer. He won't last, but he'll last long enough for Mac to forget his grouch an' listen to reason," and with this optimistic remark Captain Scraggs dropped into the engine room to get up enough steam to keep the winch working.

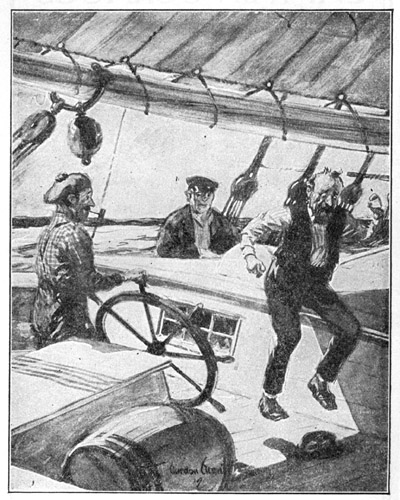

Promptly at twelve o'clock, the longshoremen knocked off work for the lunch hour and Neils Halvorsen drifted across the street to cool his parched throat with steam beer. While waiting for Scraggs to come up out of the engine room, and take him to luncheon, Mr. Gibney sauntered aft and was standing gazing reflectively upon a spot on the Maggie's stern where the hawsers had chafed away the paint, when suddenly big forebodings of evil returned to him a thousand fold stronger than they had been since Scraggs's return to the little ship. He glanced up and beheld gazing down upon him Captains Jack Flaherty and Daniel Hicks. Battle was imminent and the valiant Gibney knew it; wherefore he determined instantly to meet it like a man.

"Howdy, men," he saluted them. "Glad to have you aboard the yacht," and he stepped backward to give himself fighting room.

"Here's where we collect the towage bill on the S.S. Yankee Prince," Dan Hicks informed him, and leaped from the bulkhead straight down at Mr. Gibney. Jack Flaherty followed. Mr. Gibney welcomed Captain Hicks with a terrific right swing, which missed; before he could guard, Dan Hicks had planted left and right where they would do the most good and Mr. Gibney went into a clinch to save himself further punishment.

"Scraggsy," he bawled, "Scraggsy-y-y! Help! Murder! It's Hicks and Flaherty! Bring an ax!"

He flung Dan Hicks at Jack Flaherty; as they collided he rushed in and dealt each of them a powerful poke. However, Messrs. Hicks and Flaherty were sizeable persons and while, individually, they were no match for the tremendous Gibney, nevertheless what they lacked in horsepower they made up in pugnacity—and the salt sea seldom breeds a craven. Captain Scraggs thrust a frightened face up through the engine-room hatch, but at sight of the battle royal taking place on the deck aft, his blood turned to water and he thought only of escape. To climb up to the bulkhead without being seen was impossible, however, so, not knowing what else to do, he stood on the iron ladder and gazed, pop-eyed with horror, at the unequal contest.

Backward and forward the tide of battle surged. For nearly three minutes all Scraggs saw was an indistinct tangle of legs and arms; then suddenly the combatants disengaged themselves and Scraggs beheld Mr. Gibney lying prone upon the deck with a gory face upturned to the foggy skies. When he essayed to rise and continue the contest, Flaherty kicked him in the ribs and Hicks cursed them; so Mr. Gibney, realizing that all was over, beat the deck with his hand in token of surrender. Hicks and Flaherty waited until the fallen gladiator had recovered sufficient breath to sit up; then they pounced upon him, lifted him to the rail, and dropped him overboard. Captain Scraggs shrieked in protest at this added touch of barbarity, and Dan Hicks, turning, beheld Scraggsy's white face at the hatch.

"You're next, Scraggs," he called cheerfully, and turned to peer over the rail. Mr. Gibney had emerged on the surface and was swimming slowly away toward an adjacent float where small boats landed. He climbed wearily up on the float and sat there, gazing across at Hicks and Flaherty without animus, for to his way of thinking he had gotten off lightly, considering the enormity of his offense. The least he had anticipated was three months in hospital, and so grateful was he to Hicks and Flaherty for their great forbearance that he strangled a resolve to "lay" for Hicks and Flaherty and thrash them individually—something he was fully able to do—and forgot his aches and pains in a lively interest as to the fate of Captain Scraggs at the hands of the towboat men. He was aware that Captain Scraggs had failed ignominiously to rally to the Gibney appeal to repel boarders, and in his own expressive terminology he hoped that what the enemy would do to the dastard would be "a-plenty."

The enemy, meanwhile, had turned their attention upon Scraggs, who had dodged below like a frightened rabbit and sought shelter in the shaft alley. He had sufficient presence of mind, as he dashed through the engine room, to snatch a large monkey wrench off the tool rack on the wall, and, kneeling just inside the alley entrance he turned at bay and threatened the invaders with this weapon. Thereupon Hicks and Flaherty pelted him with lumps of coal, but the sole result of this assault was to force Scraggs further back into the shaft alley and out of range.

The towboat men held a council of war and decided to drown Scraggs out. Dan Hicks ran up on deck and returned dragging the deck fire hose behind him. He thrust the brass nozzle into the shaft alley entrance and invited Scraggs to surrender unconditionally or be drowned like a kitten. Scraggs, knowing his own fire hose, defied them, so Dan Hicks started the pump while Flaherty turned on the water. Instantly the hose burst up on deck and Scraggs's jeers of triumph filled the engine room. The enemy was about to draw lots to see which one of the two should crawl into the shaft alley and throw a cupful of chloride of lime (for they found a can of this in the engine room) in Captain Scraggs's face, when a shadow darkened the hatch and Mr. Bartholomew McGuffey demanded belligerently: "What's goin' on down there? Who the devil's takin' liberties in my engine room?"

Dan Hicks explained the situation and the just cause for drastic action which they held against the fugitive in the shaft alley. Mr. McGuffey considered a few moments and made his decision.

"If what you say is true—an' I ain't in position to dispute you, not havin' been present when you hauled the Maggie off the beach, I don't blame you for feeling sore. What I do blame you for, though, is carryin' the war aboard the Maggie. If you wanted to whale Gib an' Scraggsy you should ha' laid for 'em on the dock. Under the circumstances, you make this a pers'nal affair, an' as a member o' the crew o' the Maggie I got to take a hand an' defend my skipper agin youse two. Fact is, gentlemen, I got a date to lick him first for what he done to me last night. Howsumever, that's a private grouch. The fact remains that you two jumped my pal Bert Gibney an' licked him somethin' scandalous. Hicks, I'll take you on first. Come up out of there, you swab, and fight. Flaherty, you stay below until I send for you; if you try to climb up an' horn in on my fight with Hicks, Gibney'll brain you."

A faint cheer came from the shaft alley. "Good old Mac. At-a-boy!"

"You're on, McGuffey. Nobody ever had to beg me to fight him," Dan Hicks replied cordially, and climbed to the deck. To his great surprise, Mr. McGuffey winked at him and drew him off to the stern of the Maggie.

"There'll be no fight," he declared, "although we'll thud around on deck an' yell a couple o' times to make Scraggs think we're goin' to it. He figgers that by the time I've fought you an' Flaherty I won't be fit for combat with him, even if I lick you both; he's got it all figgered out that I'll wait a couple o' days before tacklin' him, an' he thinks my temper'll cool by that time an' he can argy me out o' my revenge. Savey?"

"I twig."

Mr. Gibney had returned to the Maggie by this time and he now took his station at the engine-room hatch and growled at Flaherty and abused him. "Keep up your courage, Scraggsy," he called, as Hicks and McGuffey pranced around the deck in simulated combat. "Mac's whalin' the whey out o' Hicks an' Hicks couldn't touch him with a buggy whip."

At the conclusion of the three minutes of horse-play, Mr. McGuffey came to the hatch again. "Up with you, Flaherty," he called loud enough for Captain Scraggs to hear, "up with you before I go down after you."

Flaherty was about to possess himself of a hatchet when the face of his confrère, Dan Hicks, appeared over McGuffey's shoulder and grinned knowingly at him. Immediately, Flaherty hurled defiance at his enemies and came up on deck, and once more to Captain Scraggs came the dull sounds of apparent conflict overhead.

Suddenly a cheer broke from Mr. Gibney. "All off an' gone to Coopertown, Scraggsy," he shouted. "Come up an' take a look at the fallen."

Out of the shaft alley came Scraggs with a rush, tossing his wrench aside the better to climb the ladder. He was half way up when Mr. Gibney reached down a great hand, grasped him by the collar, and whisked him out on deck with a single jerk. Here, to his horror, he found himself confronted by a singularly scathless trio who grinned triumphantly at him.

"Seein' is believin', Scraggs," Dan Hicks informed him. "That's a lesson you taught me an' Flaherty last night, but evidently you don't profit by experience. You're too miserable to beat up, but just to show you it ain't possible for a dirty bay pirate like you to skin the likes o' me an' Flaherty we purpose hangin' the seat o' your pants up around your coat collar. Face him about, Gibney."

Jack Flaherty raised his voice in song:

Glorious! Glorious!

One kick a piece for the four of us!

With a quick twist, Mr. Gibney presented Captain Scraggs for his penance; Flaherty and McGuffey followed Dan Hicks promptly and Captain Scraggs screamed at every kick. And now came Mr. Gibney's turn. "For failin' to stand up like a man, Scraggsy, an' battle Hicks an' Flaherty," he informed the culprit, and tossed him over to McGuffey to be held in position for him.

"Don't, Gib. Please don't," Scraggs wailed. "It ain't comin' to me from you. I never heard you callin' a-tall. Honest, I never, Gib. Have mercy, Adelbert. You saved the Maggie last night an' a quarter interest in her is yours—if you don't kick me!"

Mr. Gibney paused, foot in mid-air; surveyed the Maggie from stem to stern, hesitated, licked his lower lip, and glanced at the common enemy. For an instant it came into his mind to call upon the valiant and able McGuffey to support him in a fierce counter attack upon Hicks and Flaherty. Only for an instant, however; then his sense of fair play conquered.

"No, Scraggsy," he replied sadly. "She ain't worth it, an' your duplicity can't be overlooked. If there's anything I hate it's duplicity. Here goes, Scraggsy—and get yourself a new navigatin' officer."

Scraggs twisted and flinched instantly, and Mr. Gibney's great boot missed the mark. "Ah," he breathed, "I'll give you an extra for that."

"Don't! Please don't," Scraggs howled. "Lay off'n me an' I'll put in a new boiler an' have the compass adjusted."

The words were no sooner out of his mouth than Mr. McGuffey swung him clear of Mr. Gibney's wrath. "Swear it," he hissed. "Raise your right hand an' swear it—an' I'll protect you from Gib."

Captain Scraggs raised a trembling right hand and swore it. "I'll get a new fire hose an' fire buckets; I'll fix the ash hoist and run the bedbugs an' cockroaches out of her," he added.

"You hear that, Gib?" McGuffey pleaded. "Have a heart."

"Not unless he gives her a coat of paint an' quits bickerin' about the overtime, Bart."

"I promise," Scraggs answered him. "Pervided," he added, "you an' dear ol' Mac promises to stick by the ship."

"It's a whack," yelled McGuffey joyfully, and whirling, struck Dan Hicks a mighty blow on the jaw. "Off our ship, you hoodlums." He favoured Jack Flaherty with a hearty thump and swung again on Dan Hicks. "At 'em, Scraggsy. Here's where you prove to Gib whether you're a man—thump—or a mouse—thump—or a—thump, thump—bobtailed—thump—rat."

Dan Hicks had been upset, and as he sprawled on his back on deck, he appeared to Captain Scraggs to offer at least an even chance for victory. So Scraggs, mustering his courage, flew at poor Hicks tooth and toenail. His best was not much but it served to keep Dan Hicks off Mr. McGuffey while the latter was disposing of Jack Flaherty, which he did, via the rail, even as the towboat men had disposed of Mr. Gibney. Dan Hicks followed Flaherty, and the crew of the Maggie crowded the rail as the enemy swam to the float, crawled up on it and departed, vowing vengeance.

"All's well that ends well, gentlemen," Mr. McGuffey announced. "Scraggsy's goin' to buy a drink an' the past is buried an' forgotten. Didn't old Scraggsy put up a fight, Gib?"

"No, but he tried to, Mac. I'll tell the world he did," and he thrust out the hand of forgiveness to Scraggsy, who, realizing he had come very handsomely out of an unlovely situation, clasped the hands of Mr. Gibney and McGuffey and burst into tears. While Mr. McGuffey thumped him between the shoulder blades and cursed him affectionately, Mr. Gibney retired to change into dry garments; when he reappeared the trio went ashore for the promised grog and a luncheon at the skipper's expense.

A week had elapsed and nothing of an eventful nature had transpired to disturb the routine of life aboard the Maggie, until Bartholomew McGuffey, having heard certain waterfront whispers, considered it the part of prudence to lay his information before Scraggs and Mr. Gibney.

"Look here, Scraggs," he began briskly. "It's all fine an' dandy to promise me a new boiler, but when do I git it?"

"Why, jes' as soon as we can get this glut o' freight behind us, Bart, my boy. The way it's pilin' up on us now, what with this bein' the height o' the busy season an' all, it stands to reason we got to wait a while for dull times before layin' the Maggie up."

"What's the matter with orderin' the new boiler now so's to have it ready to chuck into her over the week-end," McGuffey suggested. "There needn't be no great delay."