This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Sunny Slopes

Author: Ethel Hueston

Release Date: May 20, 2006 [eBook #18426]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SUNNY SLOPES***

| CHAPTER | |

| I | THE BEGINNING |

| II | MANSERS |

| III | A BABY IN BUSINESS |

| IV | A WOMAN IN THE CHURCH |

| V | A MINISTER'S SON |

| VI | THE HEAVY YOKE |

| VII | THE FIRST STEP |

| VIII | REACTION |

| IX | UPHEAVAL |

| X | WHERE HEALTH BEGINS |

| XI | THE OLD TEACHER |

| XII | THE LAND O' LUNGERS |

| XIII | OLD HOPES AND NEW |

| XIV | NEPTUNE'S SECOND DAUGHTER |

| XV | THE SECOND STEP |

| XVI | DEPARTED SPIRITS |

| XVII | RUBBING ELBOWS |

| XVIII | QUIESCENT |

| XIX | RE-CREATION |

| XX | LITERARY MATERIAL |

| XXI | ADVENTURING |

| XXII | HARBORAGE |

| XXIII | THE SUNNY SLOPE |

| XXIV | THE END |

Back and forth, back and forth, over the net, spun the little white ball, driven by the quick, sure strokes of the players. There was no sound save the bounding of the ball against the racquets, and the thud of rubber soles on the hard ground. Then—a sudden twirl of a supple wrist, and—

"Deuce!" cried the girl, triumphantly brandishing her racquet in the air.

The man on the other side of the net laughed as he gathered up the balls for a new serve.

Back and forth, back and forth, once more,—close to the net, away back to the line, now to the right, now to the left,—and then—

"Ad out, I am beating you, David," warned the girl, leaping lightly into the air to catch the ball he tossed her.

"Here is a beauty," she said, as the ball spun away from her racquet.

The two, white-clad, nimble figures flashed from side to side of the court. He sprang into the air to meet her ball, and drove it into the farthest corner, but she caught it with a backward gesture. Still he was ready for it, cutting it low across the net,—yes, she was there, she got it,—but the stroke was hard,—and the ball was light.

"Was it good?" she gasped, clasping the racquet in both hands and tilting dangerously forward on tiptoe to look.

"Good enough,—and your game."

With one accord they ran forward to the net, pausing a second to glance about enquiringly, and then, one impulse guiding, kissed each other ecstatically.

"The very first time I have beaten you, David," exulted the girl. "Isn't everything glorious?" she demanded, with all of youth's enthusiasm.

"Just glorious," came the ready answer, with all of mature manhood's response to girlish youth. Clasping the slender hands more tightly, he added, laughing, "And I kiss the fingers that defeated me."

"Oh, David," the buoyant voice dropped to a reverent whisper. "I love you,—I love you,—I—I am just crazy about you."

"Careful, Carol, remember the manse," he cautioned gaily.

"But this is honeymooning, and the manse hasn't gloomed on my horizon yet. I'll be careful when I get installed. I am really a Methodist yet, and Methodists are expected to shout and be enthusiastic. When we move into our manse, and the honeymoon is ended, I'll just say, 'I am very fond of you, Mr. Duke.'" The voice lengthened into prim and prosy solemnity.

"But our honeymoon isn't to end. Didn't we promise that it should last forever?"

"Of course it will." She dimpled up at him, snuggling herself in the arm that still encircled her shoulders. "Of course it will." She balanced her racquet on the top of his head as he bent adoringly over her. "Of course it will,—unless your grim old Presbyterians manse all the life out of me."

"If it ever begins, tell me," he begged, "and we'll join the Salvation Army. There's life enough even for you."

"I beat you," she teased, irrelevantly. "I am surprised,—a great big man like you."

"And to-morrow we'll be in St. Louis."

"Yes," she assented, weakening swiftly. "And the mansers will have me in their deadly clutch."

"The only manser who will clutch you is myself." He drew her closer in his arm as he spoke. "And you like it."

"Yes, I love it. And I like the mansers already. I hope they like me. I am improving, you know. I am getting more dignified every day. Maybe they will think I am a born Presbyterian if you don't give me away. Have you noticed how serious I am getting?" She pinched thoughtfully at his chin. "David Duke, we have been married two whole weeks, and it is the most delicious, and breathless, and amazing thing in the world. It is life—real life—all there is to life, really, isn't it?"

"Yes, life is love, they say, so this is life. All the future must be like this."

"I never particularly yearned to be dead," she said, wrinkling her brows thoughtfully, "but I never even dreamed that I could be so happy. I am awfully glad I didn't die before I found it out."

"You are happy, aren't you, sweetheart?"

She turned herself slowly in his arm and lifted puckering lips to his.

"Hey, wake up, are you playing tennis, or staging Shakespeare? We want the court if you don't need it."

Mr. and Mrs. Duke, honeymooners, gazed speechlessly at the group of young men standing motionless forty feet away, then Carol wheeled about and ran swiftly across the velvety grass, over the hill and out of sight, her husband in close pursuit.

Once she paused.

"If the mansers could have seen us then!" she ejaculated, with awe in her voice.

The introduction of Mrs. David Arnold Duke, née Methodist, to the members of her husband's Presbyterian flock, was, for the most part, consummated with grace and dignity. Only one untoward incident lingered in her memory to cloud her lovely face with annoyance.

In honor of his very first honeymoon, hence his first opportunity to escort a beautiful and blushing bride to the cozy little manse he had so painstakingly prepared for her reception, the Reverend David indulged in the unwonted luxury of a taxicab. And happy in the consciousness of being absolutely correct as to detail, they were driven slowly down the beautifully shaded avenues of the Heights, one of the many charming suburbs of St. Louis,—aware of the scrutiny of interested eyes from the sheltering curtains of many windows.

Being born and bred in the ministry, Carol acquitted herself properly before the public eye. But once inside the guarding doors of the darling manse, secure from the condemning witness of even the least of the fold, she danced and sang and exulted as the very young, and very glad, must do to find expression.

Their first dinner in the manse was more of a social triumph than a culinary success. The coffee was nectar, though a trifle overboiled. The gravy was sweet as honey, but rather inclined to be lumpy. And the steak tasted like fried chicken, though Carol had peppered it twice and salted it not at all. It wasn't her fault, however, for the salt and pepper shakers in her "perfectly irresistible" kitchen cabinet were exactly alike,—and how was she to know she was getting the same one twice?

Anyhow, although they started very properly with plates on opposite sides of the round table, by the time they reached dessert their chairs were just half way round from where they began the meal, and the salad dishes were so close together that half the time they ate from one and half the time from the other. And when it was all over, they pushed the dishes back and clasped their hands promiscuously together and talked with youthful passion of what they were going to do, and how wonderful their opportunity for service was, and what revolutions they were going to work in the lives of the nice, but no doubt prosy mansers, and how desperately they loved each other. And it was going to last forever and ever and ever.

So far they were just Everybride and Everygroom. Their hearts sang and the manse was more gorgeous than any mansion on earth, and all the world was good and sweet, and they couldn't possibly ever make any kind of a mistake or blunder, for love was guiding them,—and could pure love lead astray?

David at last looked at his watch and said, rather hurriedly:

"By the way, I imagine a few of our young people will drop in to-night for a first smile from the manse lady."

Carol leaped from her chair, jerked off the big kitchen apron, and flew up the stairs with never a word. When David followed more slowly, he found her already painstakingly dusting her matchless skin with velvety powder.

"I got a brand new box of powder, David, the very last thing I did," she began, as he entered the room. "When this is gone, I'll resort to cheaper kinds. You see, father's had such a lot of experience with girls and complexions that he just naturally expects them to be expensive—and would very likely be confused and hurt if things were changed. But I can imagine what a shock it would be to you right at the start."

David assured her that any powder which added to the wonder of that most wonderful complexion was well worth any price. But Carol shook her head sagely.

"It's a dollar a box, my dear, and very tiny boxes at that. Now don't talk any more for I must fix my hair and dress, and—I want to look perfectly darling or they won't like me, and then they will not put anything in the collections and the heathens and we will starve together. Oh, will you buckle my slippers? Thanks. Here's half a kiss for your kindness. Oh, David, dear, do run along and don't bother me, for suppose some one should get here before I am all fixed, and— Shall I wear this little gray thing? It makes me look very, very sensible, you know, and—er—well, pretty, too. One can be pretty as well as sensible, and I think it's a Christian duty to do it. David, I shall never be ready. I can not be talked to, and make myself beautiful all at once. Dear, please go and say your prayers, and ask God to make them love me, will you? For it is very important, and— If I act old, and dignified, they will think I am appropriate at least, won't they? Oh, this horrible dress, I never can reach the hooks. Will you try, David, there's my nice old boy. Oh, are you going down? Well, I suppose one of us ought to be ready for them,—run along,—it's lonesome without you,—but I have to powder my face, and— Oh, that was just the preliminary. The conclusion is always the same. Bye, dearest." Then, solemnly, to her mirror, she said, "Isn't he the blessedest old thing that ever was? My, I am glad Prudence got married so long ago, or he might have wanted her instead of me. I don't suppose the mansers could possibly object to a complexion like mine. I can get a certificate from father to prove it is genuine, if they don't believe it."

Then she gave her full attention to tucking up tiny, straying curls with invisible hair pins, and was quite startled when David called suddenly:

"Hurry up, Carol, I am waiting for you."

"Oh, bless its heart, I forgot all about it. I am coming."

Gaily she ran down the stairs, parted the curtains into the living-room and said:

"Why are you sitting in the dark, David? Headache, or just plain sentimental? Where are you?"

"Over here," he said, in a curious, quiet voice.

She groped her way into the center of the room and clutched his arms. "David," she said, laughing a little nervously, "here goes the last gasp of my dear old Methodist fervor."

"Why, Carol—" he interrupted.

"Just a minute, honey. After this I am going to be settled and solemn and when I feel perfectly glorious I'll just say, 'Very good, thank you,' and—"

"But, Carol—"

"Yes, dear, just a second. This is my final gasp, my last explosion, my dying outburst. Rah, rah, rah, David. Three cheers and a tiger. Amen! Hallelujah! Hurrah! Down with the traitor, up with the stars! Now it's all over. I am a Presbyterian."

David's burst of laughter was echoed on every side of the room and the lights were switched on, and with a sickening weakness Carol faced the young people of her husband's church.

"More Presbyterians, dear, a whole houseful of them. They wanted to surprise you, but you have turned the tables on them. This is my wife, Mrs. Duke."

Slowly Carol rallied. She smiled the irresistible smile.

"I am so glad to meet you," she said, softly, "I know we are going to like each other. Aren't you glad you got here in time to see me become Presbyterian? David, why didn't you warn me that surprise parties were still stylish? I thought they had gone out."

Carol watched very, very closely all that evening, and she could not see one particle of difference between these mansers and the young folks in the Methodist Church in Mount Mark, Iowa. They told funny stories, and laughed immoderately at them. The young men gave the latest demonstrations of vaudeville trickery, and the girls applauded as warmly as if they had not seen the same bits performed in the original. They asked David if they might dance in the kitchen, and David smilingly begged them to spare his manse the disgrace, and to dance themselves home if they couldn't be more restrained. The young men put in an application for Mrs. Duke as teacher of the Young Men's Bible Class, and David sternly vetoed the measure. The young ladies asked Carol what kind of powder she used, and however she got her hair up in that most marvelous manner.

And Carol decided it was not going to be such a burden after all, and thought perhaps she might make a regular pillar in time.

When, as she later met the elder ones of the church, and was invariably greeted with a smiling, "How is our little Methodist to-day," she bitterly swallowed her grief and answered with a brightness all assumed:

"Turned Presbyterian, thank you."

But to David she said:

"I did seriously and religiously ask the Lord to let me get introduced to the mansers without disgracing myself, and I am just a teeny bit disappointed because He went back on me in such a crisis."

But David, wise minister and able exponent of his faith, said quickly:

"He didn't go back on you, Carol. It was the best kind of an introduction, and He stood by you right through. They were more afraid of you than you were of them. You might have been stiff and reserved, and they would have been cold and self-conscious, and it would have been ghastly for every one. But your break broke the ice right off. You were perfectly natural."

"Hum,—yes—natural enough, I suppose. But it wasn't dignified, and why do you suppose I have been practising dignity these last ten years?"

"Centerville, Iowa.

"Dear Carol and David—

"Please do not call me the baby of the family any more. I am in business, and babies have no business in business. Very good, wasn't it? I am practising verbosity for the book I am going to write some day. Verbosity is what I want to say, isn't it? I am never sure whether it is that or obesity. But you know what I mean.

"To begin at the beginning, then, you would be surprised how sensible father is turning out. I can hardly understand it. You remember when I insisted on studying stenography, Aunt Grace and Prue, yes, and all the rest of you, were properly shocked and horrified, and thought I ought to teach school because it is more ministerial. But I knew I should need the stenography in my writing, and father looked at me, and thought a while, and came right out on my side. And that settled it.

"Of course, when I wanted to cut college after my second year so I could get to work, father talked me out of it. But I am really convinced he was right that time, even though he wasn't on my side. But after I finished college, when they offered me the English Department in the High School in Mount Mark at seventy-five per, and when I insisted on coming down here to Centerville to take this stenographic job with Messrs. Nesbitt and Orchard, at eight a week, well, the serene atmosphere of our quiet home was decidedly murky for a while. I said I needed the experience, both stenographic and literary, and this was my opportunity.

"Aunt Grace was speechless. Prudence wept over me. Fairy laughed at me. Lark said she just wished you were home to take charge of me and teach me a few things. But father looked at me again, and thought very seriously for a while, and said he believed I was right.

"Consequently, I am at Centerville.

"Isn't it dear of father? And so surprising. The girls think he needs medical attention, and honestly I am a little worried over him myself. It was so unexpected. Really, I half thought he would 'put his foot down,' as the Ladies Aiders used to want Prudence to do with us. He was always resigned, father was, about giving the girls up in marriage, but every one always said he would draw the line there. He is developing, I guess.

"Do you remember Nesbitt and Orchard? Mr. Nesbitt was a member of the church when we lived here, but it was before I was born, so I don't feel especially well acquainted on that account. But he calls me Connie and acts very fatherly.

"He is still a member of the church, and they say around town that he is not a bit slicker outside the church than he was when father was his pastor. He hurt me spiritually at first. So I wrote to father about it. Father wrote back that I must be charitable—must remember that belonging to church couldn't possibly do Mr. Nesbitt any harm, and for all we knew to the contrary, might be keeping him out of the electric chair every day of his life. And Mr. Nesbitt couldn't do the Christians any harm—the Lord is looking after them. And those outside who point to the hypocrites inside for excuses would have to think up something new and original if we eliminated the hypocrites on their account,—'so be generous, Connie,' wrote father, 'and don't begrudge Mr. Nesbitt the third seat to the left for he may never get any nearer Paradise than that.'

"Father is just splendid, Carol. I keep feeling that the rest of you don't realize it as hard as I do, but you will laugh at that.

"Mr. Nesbitt likes me, but he has—well, he has what a minister should call a 'bad disposition.' I'll tell you more about it in German when I meet you. German is the only language I know that can do him justice.

"I have been in trouble of one kind or another ever since I got here. Mr. Nesbitt owns a lot of houses around town, and we have charge of their rental. One day he gave me the address of one of his most tumble down shacks, and promised me a bonus of five dollars if I rented it for fifteen dollars a month on a year's lease. About ten days later, sure enough I rented it, family to take possession immediately. Mr. Nesbitt was out of town, so I took the rent in advance, turned over the keys, and proceeded to spend the five dollars. I learned that system of frenzied finance from you twins in the old days in the parsonage.

"Next morning, full of pride, I told Mr. Nesbitt about it.

"'Rented 800 Stout,' he roared. 'Why, I rented it myself,—a three years' lease at eighteen a month,—move in next Monday.'

"'Mercy,' says I. 'My family paid a month in advance.'

"'So did mine.'

"'My family is already in,' says I. That was a clincher.

"He raved and he roared, and said I got them in and I could get them out. But when he grew rational and raised my bonus to ten dollars, I said I would do my best. He agreed to refund the month's rent, to pay the moving expenses both in and out, to take over their five dollar deposit for electric lights, and to pay the electric and gas bill outstanding, which wouldn't be much for two or three days.

"So off marches the business baby to the conflict.

"They didn't like it a bit, and talked very crossly indeed, and said perfectly horrible, but quite true, things about Messrs. Nesbitt and Orchard. But finally they said they would move out, only they must have until Friday to find a new house. They would move out on Saturday, and leave the keys at the office.

"Mr. Nesbitt was much pleased, and said I had done nicely, gave me the ten dollars and a box of chocolates and we were as happy as cooing doves the rest of the day.

"But my family must have been more indignant than I realized. On Saturday, at one o'clock, Mr. Nesbitt told me to go around by the house on my way home to make sure the front door was locked. It was locked all right, but I noticed that the electric lights were burning. Mr. Nesbitt had not sent the key with me, as it was an automatic lock, and it really was none of my business if folks moved out and left the lights on. Still it seemed irregular, and when I got home I tried to get Mr. Nesbitt on the phone. But he and Mr. Orchard had left the office and gone out into the country for the afternoon. Business,—they never go to the country for pleasure. So I comfortably forgot all about the electric lights.

"But Monday afternoon, Mr. Nesbitt happened to remark that his family would not move in until Wednesday. Then I remembered.

"I said, 'What is the idea in having the electric lights burning down there?'

"'What?' he shouted. He always shouts unless he has a particular reason for whispering.

"'Why, the electric lights were burning in the house when I went by Saturday.'

"'All of them?'

"'Looked it from the outside.'

"'Did you turn them off?'

"'I should say not. I hadn't the key. Besides I didn't turn them on. I didn't know who did, nor why. I just left them alone.'

"That meant a neat little electric bill of about six dollars, and Mr. Nesbitt talked to me in a very un-neutral way, and I got my hat and walked off home. He called me up after a while and tried to make peace, but I said I was ill from the nervous shock and couldn't work any more that day. So he sent me a box of candy to restore my shattered nerves, and the next day they were all right.

"One day I got rather belligerent myself. It was just a week after I came. One of his new tenants phoned in that Nesbitt must get the rubbish out of the alley back of his house or he would move out. Mr. Nesbitt tried to evade a promise, but the man was curt. 'You get that rubbish out to-day, or I get out to-morrow.'

"Mr. Nesbitt was just going to court, so he told me to call up a garbage man and get the rubbish removed.

"I didn't know the garbage men from the ministers, and they weren't classified in the directory. So I went to Mr. Orchard, a youngish sort of man, very pleasant, but slicker than Nesbitt himself.

"I said, not too amiably, 'Who are the garbage haulers in this town?'

"He said: 'Search me,' and went on writing.

"I dropped the directory on his desk, and said, "'Well, if Mr. Nesbitt loses a good tenant, I should worry.'

"Then he looked up and said: 'Oh, let's see. There's Jim Green, and Softy Meadows, and—and—Tully Scott—and—that's enough.'

"So I called them up. Jim Green was in jail for petty larceny. Softy Meadows was in bed with a broken leg. Tully Scott would do it for three fifty. So I gave him the number and told him to do it that afternoon without fail.

"Pretty soon Mr. Nesbitt came home. 'How about that rubbish?'

"'I got Tully Scott to do it for three fifty.'

"He fairly tore his hair. 'Three fifty! Tully Scott is the biggest highway robber in town, and everybody knows it! Why didn't you get the mayor and be done with it? Three fifty! Great Scott! Three fifty! You call his lordship Tully Scott up and ask him if he'll haul that rubbish for a dollar and a half, and if he won't you can call off the deal.'

"I called him up, quietly, but inwardly raging.

"'Will you haul that rubbish for a dollar and a half?'

"'No,' he drawled through his nose, 'I won't haul no rubbish for no dollar and a half, and you can tell old Skinflint I said so.'

"He hung up. So did I.

"'What did he say?'

"I thought the nasal inflection made it more forceful, so I said, 'No, I won't haul no rubbish for no dollar and a half, and you can tell old Skinflint I said so.'

"Mr. Orchard laughed, and Mr. Nesbitt got red.

"'Call up Ben Moore and see if he can do it.'

"I looked him straight in the eye. 'Nothing doing,' I said, with dignity. 'If you want any more garbage haulers, you can get them.'

"I sat down to the typewriter. Mr. Orchard nearly shut himself up in a big law book in his effort to keep from meeting anybody's eye. But Nesbitt went to the phone and called Ben Moore. Ben Moore had a four days' job on his hands. Then he called Jim Green, and Softy Meadows, and finally in despair called the only one left. John Knox,—nice orthodox name, my dear. John Knox would do it for the modest sum of five dollars, and not a—well, I'll spare you the details, but he wouldn't do it for a cent less. Nesbitt raved, and Nesbitt swore, but John Knox, while he may not be a pillar in the church, certainly stood like a rock. Nesbitt could pay it or lose his tenant. He paid.

"Mr. Orchard got up and put on his hat. 'Miss Connie wants some flowers and some candy and an ice-cream soda, my boy, and I want some cigars, and a coca cola. It's on you. Will you come along and pay the bill, or will you give us the money?'

"'I guess it will be cheaper to come along,' said Nesbitt, looking bashfully at me, for I was very haughty. But I put on my hat, and it cost him just one dollar and ninety cents to square himself.

"But they both like me. In fact, Mr. Orchard suggested that I marry him so old Nesbitt would have to stop roaring at me, but I tell him honestly that of the two evils I prefer the roaring.

"No, Carol, I am not counting on marriage in my scheme of life. Not yet. Sometimes I think perhaps I do not believe in it. It doesn't work out right. There is always something wrong somewhere. Look at Prudence and Jerry,—devoted to each other as ever, but Jerry's business takes him out among men and women, into the life of the city. And Prudence's business keeps her at home with the children. He's out, and she's in, and the only time they have to love each other is in the evening,—and then Jerry has clubs and meetings, and Prudence is always sleepy. Look at Fairy and Gene. He is always at the drug store, and Fairy has nothing but parties and clubs and silly things like that to think about,—a big, grand girl like Fairy. And she is always looking covetously at other women's babies and visiting orphans' homes to see if she can find one she wants to adopt, because she hasn't one of her own. Always that sorrow behind the twinkle in her eyes! If she hadn't married, she wouldn't want a baby. Take Larkie and Jim. Always Larkie was healthy at home, strong, and full of life. But since little Violet came, Lark is pale and weak, and has no strength at all. Aunt Grace is staying with her now. Why, I can't look at dear old Larkie without half crying.

"Take even you, my precious Carol, perfectly happy, oh, of course, but all your originality, your uniqueness, the very you-ness of you, will be absorbed in a round of missionary meetings, and prayer-meetings, and choir practises, and Sunday-school classes. The hard routine, my dear, will take the sparkle from you, and give you a sweet, but un-Carol-like precision and method. Oh, yes, you are happy, but thank you, dear, I think I'll keep my Self and do my work, and—be an old maid.

"Mr. Orchard offers himself as an alternative to the roars every now and then, and I expound this philosophy of mine in answer. He shouts with laughter at it. He says it is so, so like a baby in business. He reminds me of the time when gray hairs and crow's-feet will mar my serenity, and when solitary old age will take the lightness from my step. But I've never noticed that husbands have a way of banishing gray hairs and crow's-feet and feeble knees, have you? Babies are nice, of course, but I think I'll baby myself a little.

"I do get so homesick for the good old parsonage days, and all the bunch, and— Still, it is nice to be a baby in business, and think how wonderful it will be when I graduate from my baby-hood, and have brains enough to write books, big books, good books, for all the world to read.

"Lovingly as always,

"Baby Con."

When Carol read that letter she cried, and rubbed her face against her husband's shoulder,—regardless of the dollar powder on his black coat.

"A teeny bit for father," she explained, "for all his girls are gone. And a little bit for Fairy, but she has Gene. And quite a lot for Larkie, but she has Jim and Violet." And then, clasping her arm about his shoulders, which, despite her teasing remonstrance, he allowed to droop a little, she cried exultantly: "But not one bit for me, for I have you, and Connie is a poor, poverty-stricken, wretched little waif, with nothing in the world worth having, only she doesn't know it yet."

And there was a woman in the church.

There always is,—one who stands apart, distinct, different,—in the community but not with it, in the church but not of it.

The woman in David's church was of a languorous, sumptuous type, built on generous proportions, with a mass of dark hair waving low on her forehead, with dark, straight-gazing, deep-searching eyes, the kind that impel and hold all truanting glances. She was slow in movement, suggesting a beautiful and commendable laziness. In public she talked very little, laughing never, but often smiling,—a curious smile that curved one corner of her lip and drew down the tip of one eye. She had been married, but no one knew anything about her husband. She was a member of the church, attended with most scrupulous regularity, assisted generously in a financial way, was on good terms with every one, and had not one friend in the congregation. The women were afraid of her. So were the men. But for different reasons.

Those who would ask questions of her, ran directly against the concrete wall of the crooked smile, and turned away abashed, unsatisfied.

Carol was very shy with her. She was not used to the type. There had been women in her father's churches, but they had been of different kinds. Mrs. Waldemar's straight-staring eyes embarrassed her. She listened silently when the other women talked of her, half admiringly, half sneeringly, and she grew more timid. She watched her fascinated in church, on the street, whenever they were thrown together. But one deep look from the dark eyes set her a-flush and rendered her tongue-tied.

Mrs. Waldemar had paid scant attention to David before the advent of Carol, except to follow his movements with her eyes in a way of which he could not remain unconscious. But when Carol came, entered the demon of mischief. Carol was young, Mrs. Waldemar was forty. Carol was lovely, Mrs. Waldemar was only unusual. Carol was frank as the sunshine, Mrs. Waldemar was mysterious. What woman on earth but might wonder if the devoted groom were immune to luring eyes, and if that lovely bride were jealous?

So she talked to him after church. She called him on the telephone for directions in the Bible study she was taking up. She lounged in her hammock as he returned home from pastoral calls, and stopped him for little chats. David was her pastor, she was one of his flock.

But Carol screwed up her face before the mirror and frowned.

"David," she said to herself, when a glance from her window revealed David leaning over Mrs. Waldemar's hammock half a block away, doubtless in the scriptural act of explaining an intricate passage of Revelation to the dark-eyed sheep,—"David is as good as an angel, and as innocent as a baby. Two very good traits of course, but dangerous, tre-men-dous-ly dangerous. Goodness and innocence make men wax in women's hands." Carol, for all her youth, had acquired considerable shrewdness in her life-time acquaintance with the intricacies of parsonage life.

She looked from her window again. "There's the—the—the dark-eyed Jezebel." She glanced fearfully about, to see if David might be near enough to hear the word. What on earth would he think of the manse lady calling one of his sheep a Jezebel? "Well, David," she said to herself decidedly, "God gave you a wife for some purpose, and I'm slick if I haven't much brains." And she shook a slender fist at her image in the mirror and went back to setting the table.

David was talkative that evening. "You haven't seen much of Mrs. Waldemar, have you, dear? People here don't think much Of her. She is very advanced,—too advanced, of course. But she is very broad, and kind. She is well educated, too, and for one who has had no training, she grasps Bible truths in a most remarkable way. She has never had the proper guidance, that's the worst of it. With a little wise direction she will be a great addition to our church and a big help in many ways."

Carol lowered her lashes reflectively. She was wondering how much of this "wise direction" was going to fall to her precious David?

"I imagine our women are a little jealous of her, and that blinds them to her many fine qualities."

Carol agreed, with a certain lack of enthusiasm, and David continued with evident relish.

"Some of her ideas are dangerous, but when she is shown the weakness of her position she will change. She is not one of that narrow school who holds to a fallacy just because she accepted it in the beginning. The elders objected to her teaching a class in Sunday-school because they claimed her opinions would prove menacing to the young and uninformed. And it is true. She is dangerous company for the young right now. But she is starting out along better lines and I think will be a different woman."

"Dangerous for the young." The words repeated themselves in Carol's mind. "Dangerous for the young." Carol was young herself. "Dangerous for the young."

The next afternoon, Carol arrayed herself in her most girlishly charming gown, and with a smile on her lips, and trepidation in her heart, she marched off to call on her Jezebel. The Jezebel was surprised, no doubt of that. And she was pleased. Every one liked Carol,—even Jezebels. And Mrs. Waldemar was very much alone. However much a woman may revel in the admiration of men, there are times when she craves the confidence of at least one woman. Mrs. Waldemar led Carol up-stairs to a most seductively attractive little sitting-room, and Carol sat at her feet, as it were, for two full hours.

Then she tripped away home, more than ever aware of the wonderful charm of Mrs. Waldemar, but thanking God she was young.

When David came in to dinner, a radiant Carol awaited him. In the ruffly white dress, with its baby blue ribbons, and with a wide band of the same color in her hair, and tiny curls clustering about her pink ears, she was a very infant of a minister's wife.

David took her in his arms appreciatively. "You little baby," he said adoringly, "you look younger every day. Will you ever grow up? A minister's wife! You look more like a little girl's baby doll."

Carol giggled, and rumpled up his hair; When she took her place at the table she artfully snuggled low in her chair, peeping roguishly at him from behind the wedding-present coffee urn.

"David," she began, as soon as he finished the blessing, "I've been thinking all day of what you said about Mrs. Waldemar, and I've been ashamed of myself. I really have avoided her. She is so old, and clever, and I am such a goose, and people said things about her, and—but after last night I was ashamed. So to-day I went to see her, all alone by myself, without a gun or anything to protect me."

David laughed, nodding at her approvingly. "Good for you, Carol," he cried in approbation. "That was fine. How did you get along?"

"Just grand. And isn't she interesting? And so kind. I believe she likes me. She kept me a long time and made me a cup of tea, and begged me to come again. She nearly hypnotized me, I am really infatuated with her. Oh, we had a lovely time. She is different from us, but it does us good to mix with other kinds, don't you think so? I believe she did me good. I feel very emancipated to-night."

Carol tossed her blue-ribboned, curly head, and the warm approval in David's eyes cooled a little.

"What did she have to say?" he asked curiously.

"Oh, she talked a lot about being broad, and generous, and not allowing environment to dwarf one. She thinks it is a shame for a—a—girl of my—well, she called it my 'divine sparkle,' and she said it was a compliment,—anyhow, she said it was a shame I should be confined to a little half-souled bunch of Presbyterians in the Heights. She has a lot of friends down-town, advanced thinkers, she calls them,—a poet, and some authors, and artists, and musicians,—folks like that. They have informal meetings every week or so, and she is going to take me. She says I will enjoy them and that they will adore me."

Carol's voice swelled with triumph, and David's approval turned to ice.

"She must have liked me or she wouldn't have been so friendly. She laughed at the Heights,—she called it a 'little, money-saving, heart-squeezing, church-bound neighborhood.' She said I must study new thoughts and read the new poetry, and run out with her to grip souls with real people now and then, to keep my star from tarnishing. I didn't understand all she said, but it sounded irresistible. Oh, she was lovely to me."

"She shouldn't have talked to you like that," protested David quickly. "She is not fair to our people. She can not understand them because they live sweet, simple lives where home and church are throned. New thought is not necessary to them because they are full of the old, old thought of training their babies, and keeping their homes, and worshiping God. And I know the kind of people she meets down-town,—a sort of high-class Bohemia where everybody flirts with everybody else in the name of art. You wouldn't care for it."

Carol adroitly changed the subject, and David said no more.

The next day, quite accidentally, she met Mrs. Waldemar on the corner and they had a soda together at the drug store. That night after prayer-meeting David had to tarry for a deacons' meeting, and Carol and Mrs. Waldemar sauntered off alone, arm in arm, and waited in Mrs. Waldemar's hammock until David appeared.

And David did not see anything wonderful in the dark, deep eyes at all,—they looked downright wicked to him. He took Carol away hurriedly, and questioned her feverishly to find out if Mrs. Waldemar had put any fresh nonsense into her pretty little head.

Day after day passed by and David began going around the block to avoid Mrs. Waldemar's hammock. Her advanced thoughts, expressed to him, old and settled and quite mature, were only amusing. But when she poured the vials of her emancipation on little, innocent, trusting Carol,—it was—well, David called it "pure down meanness." She was trying to make his wife dissatisfied with her environment, with her life, with her very husband. David's kindly heart swelled with unaccustomed fury.

Carol always assured him that she didn't believe the things Mrs. Waldemar said,—it was interesting, that was all, and curious, and gave her new things to think about. And minister's families must be broad enough to make Christian allowance for all.

But, curiously enough, she grew genuinely fond of Mrs. Waldemar. And Mrs. Waldemar, in gratitude for the girlish affection of the little manse lady, left David alone. But one day she took Carol's dimpled chin in her hand, and turned the face up that she might look directly into the young blue eyes.

"Carol," she said, smiling, "you are a girlie, girlie wife, with dimples and curls and all the baby tricks, but you're a pretty clever little lady at that. You were not going to let your darling old David get into trouble, were you? And quite right, my dear, quite right. And between you and me, I like you far, far better than your husband." She smiled the crooked smile and pinched Carol's crimson cheek. "The only way to keep hubby out of danger is to tackle it yourself, isn't it? Oh, don't blush,—I like you all the better for your little trick."

"Centerville, Iowa.

"Dear Carol and David:

"I am getting very, exceptionally wise. I am really appalled at myself. It seems so unnecessary in one so young. You will remember, Carol, that I used to say it was unfair that ministers' children should be denied so much of the worldly experience that other ordinary humans fall heir to by the natural sequence of things. I resented the deprivation. I coveted one taste of every species of sweet, satanic or otherwise.

"I have changed my mind. I have been convinced that ordinaries may dabble in forbidden fires, and a little cold ointment will banish every trace of the flame, but ministers' children stay scarred and charred forever. I have decided to keep far from the worldly blazes and let others supply the fanning breezes. For you know, Carol, that the wickedest fires in the world would die out if there were not some willing hands to fan them.

"There is the effect. The cause—Kirke Connor.

"Carol, has David ever explained to you what fatal fascination a semi-satanic man has for nice, white women? I have been at father many times on the subject, and he says, 'Connie, be reasonable, what do I know about semi-satanics?' Then he goes down-town. See if you can get anything out of David on the subject and let me know.

"Kirke is a semi-satanic. Also a minister's son. He has been in trouble of one kind or another ever since I first met him, when he was fourteen years old. He fairly seethed his way through college. Mr. Connor has resigned from the active ministry now and lives in Mount Mark, and Kirke bought a partnership in Mr. Ives' furniture store and goes his troubled, riotous way as heretofore. That is, he did until recently.

"A few weeks ago I missed my railway connections and had to lay over for three hours in Fairfield. I checked my suit-case and started out to look up some of my friends. As I went out one door, I glimpsed the vanishing point of a man's coat exiting in the opposite direction. I started to cut across the corner, but a backward glance revealed a man's hat and one eye peering around the corner of the station. Was I being detected? I stopped in my tracks, my literary instinct on the alert. The hat slowly pivoted a head into view. It was Kirke Connor. He shuffled toward me, glancing back and forth in a curious, furtive way. His face was harrowed, his eyes blood-shot. He clutched my hand breathlessly and clung to me as to the proverbial straw.

"'Have you seen Matters?' he asked.

"'Matters?'

"'You know Matters,—the sheriff at Mount Mark.'

"I looked at him in a way which I trust became the daughter of a district superintendent of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

"He mopped his fevered brow.

"'He has been on my trail for two days.' Then he twinkled, more like himself. 'It has been a hot trail, too, if I do say it who shouldn't. If he has had a full breath for the last forty-eight hours, I am ashamed of myself.'

"'But what in the world—'

"'Let's duck into the station a minute. I know the freight agent and he will hide me in a trunk if need be. I will tell you about it. It is enough to make your blood run cold.'

"Honestly, it was running cold already. Here was literature for the asking. Kirke's wild appearance, his furtive manner, the searching sheriff—a plot made to order. So I tried to forget the M. E. Universal, and we slipped into the station and seated ourselves comfortably on some egg boxes in a shadowy corner where he told his sad, sad tale.

"'Connie, you keep a wary eye on the world, the flesh and the devil. I know whereof I speak. Other earth-born creatures may flirt with sin and escape unscathed. But the Lord is after the minister's son.'

"'I thought it was the sheriff after you?' I interrupted.

"'Well, so it is, technically. And the devil is after the sheriff, but I think the Lord is touching them both up a little to get even with me. Anyhow, between the Lord and the devil, with the sheriff thrown in, this world is no place for a minister's son. And the rule works on daughters, too.

"'You know, Connie, I have received the world with open hands, a loving heart, a receptive soul. And I got gloriously filled up, too, let me tell you. Connie, shun the little gay-backed cards that bear diamonds and hearts and spades. Connie, flee from the ice-cold bottles that bubble to meet your lips. Connie, turn a cold shoulder to the gilded youths who sing when the night is old.'

"'For goodness' sake, Kirke, tell me the story before the sheriff gets you.'

"'Well, it is a story of bottles on ice.'

"'Mount Mark is dry.'

"'Yes, like other towns, Mount Mark is dry for those who want it dry, but it is wet enough to drown any misguided soul who loves the damp. I loved it,—but, with the raven, nevermore. Connie, there is one thing even more fatal to a minister's son than bottles of beer. That thing is politics. If I had taken my beer straight I might have escaped. But I tried to dilute it with politics, and behold the result. My father walking the floor in anguish, my mother in tears, my future blasted, my hopes shattered.'

"'Kirke, tell me the story.'

"'Matters is running for reelection. I do not approve of Matters. He is a booze fighter and a card shark and a lot of other unscriptural things. As a Methodist and a minister's son I felt called to battle his return to office. So I went out electioneering for my friend and ally, Joe Smithson. You know, Connie, that in spite of my wandering ways, I have friends in the county and I am a born talker. I took my faithful steed and I spent many hours, which should have been devoted to selling furniture, decrying the vices of Matters, extolling the virtues of Smithson. Matters got his eye on me.

"'He had the other eye on that office. He saw he must make a strong bid for county favor. The easiest way to do that in Mount Mark is to get after a boot-legger. There was Snippy Brown, a poor old harmless nigger, trying to earn an honest living by selling a surreptitious bottle from a hole in the ground to a thirsting neighbor in the dead of night. Plainly Snippy Brown was fairly crying to be raided. Matters raided him. And he got a couple of hundred of bottles on ice.'

"'Served him right,' I said, in a Sabbatical voice.

"'To be sure it did. And Matters put him in jail and made a great fuss getting ready for his trial. I had a friend at court and he tipped me off that Matters was going to disgrace the Methodist Church in general and the Connors in particular by calling me in as a witness, making me tell where I bought sundry bottles known to have been in my possession. Picture it to yourself, sweet Connie,—my white-haired mother, my sad-eyed father, the condemning deacons, the sneering Sunday-school teachers, the prim-lipped Epworth Leaguers,—it could not be. I left town. Matters left also,—coming my way. For two days we have been at it, hot foot, cold foot. We have covered most of southeastern Iowa in forty-eight hours. He has the papers to serve on me, but he's got to go some yet.'

"Kirke stood up and peered about among the trunks. All serene.

"'I am nearly starved,' he said plaintively. 'Do you suppose we could sneak into some quiet joint and grab a ham sandwich and a cup of coffee?'

"I was willing to risk it, so we sashayed across the Street, I swirling my skirts as much as possible to help conceal unlucky Kirke.

"But alas! Kirke had taken just one ravenous gulp at his sandwich when he stopped abruptly, leaning forward, his coffee cup upraised. I followed his wide-eyed stare. There outside the window stood Matters, grinning diabolically. He pushed open the door, Kirke leaped across the counter and vaulted through the side window, crashing the screen. Matters dashed around the house in hot pursuit, and I—well, consider that I was a reporter, seeking a scoop. They did not beat me by six inches. Only I wish I had dropped the sandwich. I must have looked funny.

"Kirke flashed behind a shed, Matters after him, I after Matters. Kirke zigzagged across a lawn dodging from tree to tree,—Matters and I. Kirke turned into an alley,—Matters and I. Woe to the erring son of a minister! It was a blind alley. It ended in a garage and the garage was locked.

"Matters pulled out a revolver and yelled, 'Now stop, you fool; stop, Kirke!' Kirke looked back; I think he was just ready to shin up the lightning rod but he saw the revolver and stopped. Matters walked up, laughing, and handed him a paper. Kirke shoved it in his pocket. I clasped my sandwich in both hands and looked at them tragically,—sob element. Then Matters turned away and said, 'See you later, Kirke. I congratulate the county on securing your services. Just the kind of witness we like, nice, respectable, good family, and all. Makes it size up big, you know. Be sure and invite your friends.'

"For a second I thought Kirke would strike him. I shook the sandwich at him warningly and he answered with a wave of his own,—yes, he had his sandwich, too. Then he said in a low voice, 'All right, Matters. But you call me in that trial and I'll get you.'

"'Oh, oh, Sonny, you must not threaten an officer of the law,' said Matters, in a hateful, chiding voice. He turned and sauntered away. Kirke and I watched him silently until he was out of sight. Then we turned to each other sympathetically.

"'Let's go back after that coffee,' said Kirke bravely.

"He took a bite of his sandwich thoughtfully, and I did of mine, trying to eat the lump in my throat with it. An hour later we went our separate ways.

"I heard nothing further for two weeks, then Mr. Nesbitt was called East on business and said I might go home if I liked. Imagine my ecstasy. I found the family, as well as all Methodists in general, quite uplifted over the strange case of Kirke Connor. From a semi-satanic, he had suddenly evoluted into a regular pillar, as became the son of his saintly mother and his orthodox father. He attended church, he sang in the choir, he went to Sunday-school, he was prominent at prayer-meeting. Every one was full of pious satisfaction and called him 'dear old Kirke,' and gave him the glad hand and invited him to help at ice-cream socials. No one could explain it, they thought he was a Mount Mark edition of Twice Born Men in the flesh.

"So the first afternoon when he drove around with his speedy little brown horse and his rubber tired buggy and asked me to go for a drive, father smiled, and Aunt Grace demurred not. Maybe I could give him a little more light. I watched him pretty closely the first mile or so. He had nothing to say until we were a mile out of town. He is a good-looking fellow, Carol,—you remember, of course, because you never forget the boys, especially the good-looking ones. His eyes were clear and slightly humorous, as if he knew a host of funny things if he only chose to tell. Finally in answer to my reproachful gaze, he said:

"'Well, I didn't have anything to say about it, did I? I did not ask to be born a minister's son. It was foreordained, and now I've got to live up to it in self-defense. There may be forgiveness for other erring ones, but I tell you our crowd is spotted.'

"I had nothing to say.

"'Well, you might at least say, "Good for you, my boy. Here's luck?"' he complained.

"I was still silent.

"'It is good business, too,' he continued belligerently. 'I am selling lots of furniture. I have burned the black and white cards. I have broken the ice-cold bottles. I have shunned the gilded youths with mellow voices. I go to church. I sell furniture. I sleuth Matters.'

"'You what?'

"'I am trailing Matters. Turn about. Where he goeth, I goeth. Where he lodgeth, I lodgeth. His knowledge is my knowledge, and his tricks, my salvation.'

"'You make me sick, Kirke. Why don't you talk sense?'

"'He is crooked, Connie, and everybody knows it. But it is no cinch catching him at it. Smithson is going to be elected and Matters knows it. But the only way I can keep out of that trial is to get something on Matters. So whenever he is out, I am out on the same road. He is going toward New London this afternoon and so are we. I have got just five more days and you must be a good little scout and go driving with me, so he won't catch on that I am sleuthing him. He will think I am just beauing you around in the approved Mount Mark style.'

"Sure enough after a while we came across Matters talking to a couple of farmers on the cross roads, and Kirke and I stopped a quarter of a mile farther down and ate sandwiches and told stories, and when Matters passed us a little later he could have sworn we were there just for our joy in each other's company. But we did not learn anything.

"The next day we were out again, with no better luck. But the third day about four in the afternoon, Kirke called me on the telephone. There was subtle excitement in his voice.

"'Come for a drive, Connie?' he asked; common words, but there was a world of hidden invitation, of secret lure, in his voice for me.

"'Yes, gladly,' I said. Father did not nod approvingly and Aunt Grace did not smile this time. Three days in succession was a little too warm even for a newly made pillar, but they said nothing and Kirke and I set out.

"'He raided Jack Mott's last night and has about three hundred bottles to smash this afternoon. The old fellow is pretty fond of the ice-cold bottles himself and it is common report that he raids just often enough to keep himself supplied. So I think I'll keep an eye on him to-day. He started half an hour ago, south road, and he has Gus Waldron with him,—his boon companion, and the most notoriously ardent devotee of the bottles in all dear dry Mount Mark. Lovely day for a drive, isn't it?'

"'Yes, lovely.' I was very happy. I felt like a princess of old, riding off into danger, and I felt very warm and friendly toward Kirke. Remember that he is very good-looking and just bad enough in spite of his new pillar-hood, to be spell-binding, and—it was lots of fun. Kirke grabbed my hand and squeezed it chummily, and I smiled at him.

"'You are a glorious girl,' he said.

"I suppose I should have reminded him and myself that he was a semi-satanic, but I did not. I laughed and rubbed the back of his hand softly with the tips of my nice pink finger nails, and laughed again.

"Then here came a light wagon,—Matters and Waldron,—going home, and we realized we had been loitering on the job. Kirke shook his head impatiently.

"'You distracted me,' he said. 'I forgot my reputation's salvation in the smile of your eye.'

"But we drove on to look the field over. Less than half a mile down the road we came to a low creek with rocky rugged banks. The banks were splashed and splattered with bits of glass, and over the glass and over the rocks ran thin trickling streams of a pale brown liquid that had a perfectly sickening odor. I sniffed disgustedly as we walked over to reconnoiter.

"'I guess he made good all right,' said Kirke in a disappointed voice, inspecting the glass-splattered banks of the creek. Then he leaped across and walked lightly up the bank on the opposite side. Stooping down, he lifted an unbroken bottle and waved it at me, laughing.

"'They missed one. Never a crack in it and still cold.' He looked at it curiously, affectionately, then with resignation. 'I am a minister's son,' he reminded himself sternly. He lifted the bottle above his head, and with his eye selected a nice rough rock half way down the bank. 'Watch the bubbles,' he called to me.

"'Hay, mister,' interposed a voice, 'gimme half a dollar an' I'll show you a whole pile of 'em that ain't broke.'

"Slowly we rallied from our stupefaction as we gazed at the slim, brown, barefooted lad of the farm who was proudly brandishing a forbidden cigarette of corn-silks.

"'A whole pile of 'em. On the square?' asked Kirke with glittering eyes.

"'Yes, sir. A couple o' fellows come out in a light wagon a while ago an' had a lot of bottles in boxes. First they throwed one on the rocks, an' then they throwed one up in the tall grass, one up an' one down. There's a whole pile of 'em that ain't broke at all. An' the little dark fellow says, "A good job, Gus. We'll be Johnny-on-the-spot as soon as it gets dark."'

"Kirke was standing over him, his eyes bright, his hands clenched. 'On the level?' he whispered.

"'Sure, but gimme the half first.' Kirke passed out a silver dollar without a word and the boy snatched it from him, giggling to himself with rapture.

"'Right up there, mister, in that pile of weeds.'

"Kirke took my hand and we scrambled up the bank, pulling back the tall grass,—no need to stoop and look. Bottle after bottle, bottle after bottle, lay there snugly and securely, waiting for the sheriff and his friend to rescue them after dark.

"The lad had already disappeared, smoking his corn-silks rapturously, his dollar snug in the palm of his hand. And Kirke and I, without a word, began patiently carrying the bottles to the buggy. Again and again we returned to the clump of weeds, counting the bottles as we carried them out,—a hundred and fifty of them, even.

"Then we got into the buggy, feet outside, for the bed of the buggy was filled and piled high, covered with the robe to discourage prying eyes, and turned the little brown mare toward town.

"'Connie, would you seriously object to kissing me just once? I feel the need of it this minute,—moral stimulus, you know.'

"'Ministers' daughters have to be very, very careful,' I told him in an even voice.

"We were both silent then as we drove into town. When he pulled up in front of the house he looked me straight in the face, and he uses his eyes effectively.

"'You are a darling,' he said.

"I said 'Thanks,' and went into the house.

"He told me next morning what happened that evening. Of course he was there to witness Matters' discomfiture. He did not put in appearance until the sheriff and his friend were climbing anxiously and sadly into the light wagon to return home empty-handed. Then he sauntered from behind a hedge and lifted his hat in his usual debonair manner.

"'By the way, Mr. Sheriff,' he began in a quiet, ingratiating voice, 'I hope I am not to be called as a witness in that boot-legging case.'

"Matters snarled at him. 'Pooh,' he said angrily, 'you can't blackmail me like that. You can't prove anything on me. I reckon the people around here will take the word of the sheriff of their county against the booze fightin' son of a Methodist preacher.'

"Kirke waved his hand airily. 'Far be it from me to enter into any defense of my father's son. But a hundred and fifty bottles are pretty good evidence. And speaking of witnesses, I have a hunch that the people of this county will fall pretty hard for anything that comes from the lips of the baby daughter of the district superintendent of the Methodist Church.'

"Matters hunched forward in his seat. 'Connie Starr,' he said, in a hollow voice.

"Kirke swished the weeds with his cane,—he has all those graceful affectations.

"Matters swallowed a few times. 'Old man Starr is too smart a man to get his family mixed up in politics,' he finally brought out.

"'Baby Con is of age, I think,' said Kirke lightly. 'And she is very advanced, you know, something of a reformer, has all kinds of emancipated notions.'

"Matters whipped up and disappeared, and Kirke went to prayer-meeting. Aunt Grace saw him; I wasn't there.

"The next day, I met Matters on the street. Rather, he met me.

"'Miss Connie,' he said in a friendly, inviting voice, 'you know there are a lot of things in politics that girls can't get to the bottom of. You know my record, I've been a good Methodist since before you were born. Sure you wouldn't go on the witness stand on circumstantial evidence to make trouble for a good Methodist, would you?'

"I looked at him with wide and childish eyes. 'Of course not, Mr. Matters,' I said quickly. He brightened visibly. 'But if I am called on a witness stand I have to tell what I have seen and heard, haven't I, whatever it is?' I asked this very innocently, as one seeking information only.

"'Your father wouldn't let a young girl like you get mixed up in any dirty county scandal,' he protested.

"'If I was—what do you call it—subpoenaed—is that the word?' He forgot that I was working in a lawyer's office. 'If I was subpoenaed as a witness, could father help himself?'

"Mr. Matters went forlornly on his way and that night Kirke came around to say that the sheriff had informed him casually that he thought his services would not be needed on that boot-legging case,—they had plenty of other witnesses,—and out of regard for the family, etc., etc.

"Kirke smiled at him. 'Thank you very much. And, Matters, I have a hundred and fifty nice cold bottles in the basement,—if you get too warm some summer evening come around and I'll help you cool off.'

"Matters thanked him incoherently and went away.

"That day Kirke and I had a confidential conversation. 'Connie Starr, I believe I am half a preacher right now. You marry me, and I will study for the ministry.'

"'Kirke Connor,' I said, 'if any fraction of you is a minister, it isn't on speaking terms with the rest of you. That's certain. And I wouldn't marry you if you were a whole Conference. And I don't want to marry a preacher of all people. And anyhow I am not going to get married at all.'

"At breakfast the next morning father said, 'I believe Kirke Connor is headed straight, for good and all. Now if some nice girl could just marry him he would be safe enough.'

"Aunt Grace looked at him warningly. 'But of course no nice girl could do it, yet,' she interposed quickly. 'It wouldn't be safe. He can't marry until he is sure of himself.'

"'Oh, I don't know,' I said thoughtfully. 'Provided the girl were clever as well as nice, she could handle Kirke easily. Now I may not be the nicest girl in the world, but no one can deny that I am clever.'

"Father swallowed helplessly. Then he rallied. 'By the way, Connie, won't you come down to Burlington with me for a couple of days? I have a lot of work to do there, and we can have a nice little honeymoon all by ourselves. What do you say?'

"'Oh, thank you, father, that is lovely. Let's go on the noon train, shall we? I can be ready.'

"'All right, just fine.' He flashed a triumphant glance at Aunt Grace and she dimpled her approval.

"'Now don't tell any one we are going, father,' I cautioned him. 'I want to surprise Kirke Connor. He is going to Burlington on that train himself, and it will be such a joke on him to find us there ready to be entertained. He is to be there several days, so he can amuse me while you are busy. Isn't it lovely? He really needs a little boosting now, and it is our duty, and—will you press my suit, Auntie? I must fly or I won't be ready.'

"Aunt Grace looked reproachfully at father, and father looked despairingly at Aunt Grace. But we had a splendid time in Burlington, the three of us, for father never did one second's work all the time, he was so deathly afraid to leave me alone with Kirke.

"Isn't it lots of fun to be alive, Carol? So many thrilling and interesting and happy things come up every day,—I love to dig in and work hard, and how I love to drop my work at five thirty and run home and doll up, and play, and flirt—just nice, harmless flirting,—and sing, and talk,—really, it is a darling little old world, isn't it?

"Oh, and by the way, Carol, when you want a divorce just write me about it. Mr. Nesbitt and I specialize on divorces, and I can do the whole thing myself and save you lots of trouble. Just tell me when, and I will furnish your motive.

"Lovingly as always,

"Connie."

The burden of ministering rested very lightly on Carol's slender shoulders. The endless procession of missionary meetings, aid societies, guilds and boards, afforded her a childish delight and did not sap her enthusiasm to the slightest degree. She went out of her little manse each new day, laughing, and returned, wearily perhaps, but still laughing. She sang light-heartedly with the youth of the church, because she was young and happy with them. She sympathized passionately with the old and sorry ones, because the richness of her own content, and the blessed perfection of her own life, made her heart tender.

Into her new life she had carried three matchless assets for a minister's wife,—a supreme confidence in the exaltation of the ministry, a boundless adoration for her husband, and a natural liking for people that made people naturally like her. Thus equipped, she faced the years of aids and missions with profound serenity.

She was sorry they hadn't more time for the honeymoon business, she and David. Honeymooning was such tremendously good fun. But they were so almost unbelievably busy all the time. On Monday David was down-town all day, attending minister's meeting and Presbytery in the morning, and looking up new books in the afternoon. Carol always joined him for lunch and they counted that noon-time hour a little oasis in a week of work. In the evening there were deacons' meetings, or trustees' meetings, or the men's Bible class. On Tuesday evening they had a Bible study class. On Wednesday evening was prayer-meeting. Thursday night, they, with several of their devoted workers, walked a mile and a half across country to Happy Hollow where they conducted mad little mission meetings. Friday night Carol met with the young women's club, and on Saturday night was a mission study class.

Carol used to sigh over the impossibility of having a beau night. She said that she had often heard that husbands couldn't be sweethearts, but she had never believed it before. Pinned down to facts, however, she admitted she preferred the husband.

Mornings Carol was busy with housework, talking to herself without intermission as she worked. And David spent long hours in his study, poring over enormous books that Carol insisted made her head ache from the outside and would probably give her infantile paralysis if she dared to peep between the covers. Afternoons were the aid societies, missionary societies, and all the rest of them, and then the endless calls,—calls on the sick, calls on the healthy, calls on the pillars, calls on the backsliders, calls on the very sad, calls on the very happy,—every varying phase of life in a church community merits a call from the minister and his wife.

The heavy yoke,—the yoke of dead routine,—dogs the footsteps of every minister, and even more, of every minister's wife. But Carol thought of the folks that fitted into the cogs of the routine to drive it round and round,—the teachers, the doctors' wives, the free-thinkers, the mothers, the professional women, the cynics, the pillars of the church,—and thinking of the folks, she forgot the routine. And so to her, routine could never prove a clog, stagnation. Every meeting brought her a fresh revelation, they amused her, those people, they puzzled her, sometimes they made her sad and frightened her, as they taught her facts of life they had gleaned from wide experience and often in bitter tears. Still, they were folks, and Carol had always had a passion for people.

David worked too hard. It was positively wicked for any human being to work as he did, and she scolded him roundly, and even went so far as to shake him, and then kissed him a dozen times to prove how very angry she was at him for abusing himself so shamefully.

David did work hard, as hard as every young minister must work to get things going right, to make his labor count. His face, always thin, was leaner, more intense than ever. His eyes were clear, far-seeing. The whiteness of his skin, amounting almost to pallor, gave him that suggestion of spirituality not infrequently seen in men of passionate consecration to a high ideal. The few graying hairs at his temples, and even the half-droop of his shoulders, added to his scholarly appearance, and Carol was firmly convinced that he was the finest-looking man in all St. Louis, and every place else for that matter.

The mad little mission, so-called because of the riotous nature of the meetings held there, was in a most flourishing condition. Everything was going beautifully for the little church in the Heights, and in their gratitude, and their happiness, Carol and David worked harder than ever,—and mutually scolded each other for the folly of it.

"I tell you this, David Arnold Duke," Carol told him sternly, "if you don't do something to that cold so you can preach without coughing, I shall do the preaching myself, and then where would you be?"

"Without a job, of course," he answered. "But you wouldn't do it. The wind has chafed your darling complexion, and you wouldn't go into the pulpit with a rough face. Your devotion to your beauty saves me."

"All very well, but maybe you think a cold-sermon is effective." Carol stood up and lifted her hand impressively. "My dear brothers and sisters,—hem-ah-hem-h-hh-em,—let us unite in reading the—ah-huh-huh-huh. Let us sing—h-h-h-h-hem—well, let us unite in prayer then—ah-chooo! ah-choooooo!"

"Where did you put those cough-drops?" he demanded. "But even at that it is better than you would do. 'Just as soon as I powder my face we will unite in singing hymn one hundred thirty-six. Oh, excuse me a minute,—I believe I feel a cold-sore coming,—I have a mirror right here, and it won't take a minute. Now, I am ready. Let us arise and sing,—but since I can not sing I will just polish my nails while the rest of you do it. Ready, go!'"

Carol laughed at the picture, but marched off for the bottle of cough medicine and the powder box, and while he carefully measured out a teaspoonful of the one for himself, she applied the other with gay devotion.

"But I truly think you should not go to Happy Hollow to-night," she said. "Mr. Baldwin will go with me, bless his faithful old pillary heart. And you ought to stay in. It is very stormy, and that long walk—"

"Oh, nonsense, a little cough like this! You are dead tired yourself; you stay at home to-night, and Baldwin and I will go. You really ought to, Carol, you are on the jump every minute. Won't you?"

"Most certainly not. I haven't a cold, have I? Maybe you want to keep me away so you can flirt with some of the Hollowers while I am out of sight. Absolutely vetoed. I go."

"Please, Carol,—won't you? Because I ask it?"

She snuggled up to him at that and said: "It's too lonesome, Davie, and I have to go to remind you of your rubbers, and to muffle up your throat. But—"

The ring of the telephone disturbed them, and she ran to answer.

"Mr. Baldwin?—Yes—Oh, that is nice of you. I've been trying to coax him to stay home myself. David, Mr. Baldwin thinks you should not go out to-night, with such a cold, and he will take the meeting, and—oh, please, honey."

David took the receiver from her hand.

"Thanks very much, Mr. Baldwin, that is mighty kind of you, but I feel fine to-night.—Oh, sure, just a little cold. Yes, of course. Come and go with us, won't you? Yes, be here about seven. Better make it a quarter earlier, it's bad walking to-night."

"David, please," coaxed Carol.

"Goosie! Who but a wife would make an invalid of a man because he sneezes?" David laughed, and Carol said no more.

But a few minutes later, as she was carefully arranging a soft fur hat over her hair and David stood patiently holding her coat, there came a light tap at the door.

"It is Mr. Daniels," said Carol. "I know his knock. Come in, Father Daniels. I knew it was you."

The old elder from next door, his gray hair standing in every direction from the wind he had encountered bareheaded, his little gray eyes twinkling bright, opened the door.

"You crazy kids aren't going down to that Hollow a night like this," he protested.

They nodded, laughing.

"Well, David can't go," he said decidedly. "That's a bad cold he's got, and it's been hanging on too long. I can't go myself for I can't walk, but I'll call up my son-in-law and make him go. So take off your hat, Parson, and— No you come over and read the Bible to me while the young folks go gadding. I need some ministerial attention myself,—I'm wavering in my faith."

"You, wavering?" demanded David. "If no one ever wavered any harder than you do, Daniels, there wouldn't be much of a job for the preachers. And you say for me to let Carol go with Dick? What are you thinking of? I tell you when any one goes gadding with Carol, I am the man." Then he added seriously: "But really, I've got to go to-night. We're just getting hold of the folks down there and we can't let go. Otherwise, I should make Carol stay in. But the boys in her class are so fond of her that I know she is needed as much as I am."

"But that cough—"

"Oh, that cough is all right. It will go when spring comes. I just haven't had a chance to rest my throat. I feel fine to-night. Come on in, Baldwin. Yes, we are ready. Still snowing? Well, a little snow— Here, Carol, you must wear your gaiters. I'll buckle them."

A little later they set out, the three of them, heads lowered against the driving snow. There were no cars running across country, and indeed not even sidewalks, since it was an unfrequented part of the town with no residences for many blocks until one reached the little, tumbledown section in the Hollow. Here and there were heavy drifts, and now and then an unexpected ditch in the path gave Carol a tumble into the snow, but, laughing and breathless, she was pulled out again and they plodded heavily on.

In spite of the inclement weather, the tiny house—called a mission by grace of speech—was well and noisily filled. Over sixty people were crowded into the two small rooms, most of them boys between the ages of twelve and sixteen, laughing, coughing, dragging their feet, shoving the heavy benches, dropping song-books. They greeted the snow-covered trio with a royal roar, and a few minutes later were singing, "Yes, we'll gather at the river," at the tops of their discordant voices. Carol sat at the wheezy organ, painfully pounding out the rhythmic notes,—no musician she, but willing to do anything in a pinch. And although at the pretty little church up in the Heights she never attempted to lift her voice in song, down at the mission she felt herself right in her element and sang with gay good-will, happy in the knowledge that she came as near holding to the tune as half the others.

Most of the evening was spent in song, David standing in the narrow doorway between the two rooms, nodding this way, nodding that, in a futile effort to keep a semblance of time among the boisterous worshipers. A short reading from the Bible, a very brief prayer, a short, conversational story-talk from David, and the meeting broke up in wild clamor.

Then back through the driving snow they made their way, considering the evening well worth all the exertion it had required.

Once inside the cozy manse, David and Carol hastily changed into warm dressing-gowns and slippers and lounged lazily before the big fireplace, sipping hot coffee, and talking, always talking of the work,—what must be done to-morrow, what could be arranged for Sunday, the young people's meeting, the primary department, the mission study class.

And Carol brought out the big bottle and administered the designated teaspoonful.

"For you must quit coughing, David," she said. "You ruined two good points last Sunday by clearing your throat in the middle of a phrase. And it isn't so easy making points as that."

"Aren't you tired of hearing me preach, Carol? We've been married a whole year now. Aren't you finding my sermons monotonous?"

"David," she said earnestly, resting her head against his shoulder, partly for weariness, partly for the pleasure of feeling the rise and fall of his breast,—"when you go up into the pulpit you look so white and good, like an apostle or a good angel, it almost frightens me. I think, 'Oh, no, he isn't my husband, not really,—he is just a good angel God sent to keep me out of mischief.' And while you are preaching I never think, 'He is mine.' I always think, 'He is God's.'"

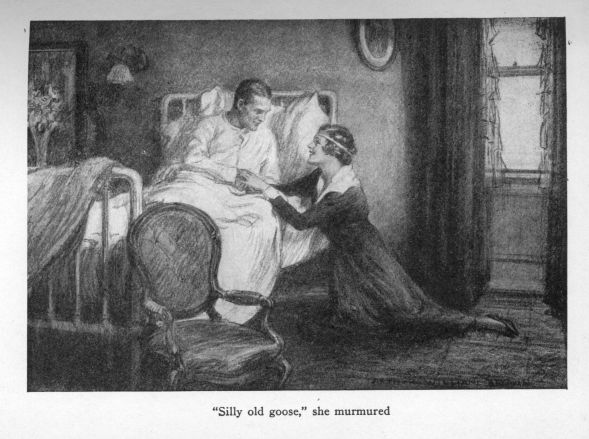

Tears came into her eyes as she spoke, and David drew her close in his arms.

"Do you, sweetheart? It seems a terrible thing to stand up there before a houseful, of people, most of them good, and clean, and full of faith, and try to direct their steps in the broader road. I sometimes feel that men are not fit for it. There ought to be angels from Heaven."

"But there are angels from Heaven watching over them, David, guiding them, showing them how. I believe good white angels are guiding every true minister,—not the bad ones— Oh, I know a lot about ministers, honey,—proud, ambitious, selfish, vainglorious, hypocritical, even amorous, a lot of them,—but there are others, true ones,—you, David, and some more. They just have to grow together until harvest, and then the false ones will be dug up and dumped in the garbage."

For a while they were silent.

Finally he asked, smiling a little, "Are you getting cramped, Carol? Are you getting narrow, and settling down to a rut? Have you lost your enthusiasm and your sparkle?"

Carol laughed at him. "David, do you remember the first night we were married, when we knelt down together to say our prayers and you put your arm around my shoulder, and we prayed there, side by side? Dearest, that one little fifteen minutes of confidence and humility and heart-gratitude was worth all the sparkle and fire in the world. But have I lost it? Seems to me I am as much a shouting Methodist as ever."

David laughed, coughing a little, and Carol bustled him off to bed, sure he was catching a brand new cold, and berating herself roundly for allowing this foolish angel of hers to get a chill right on her very hands.

It was Sunday night in mid-winter. After church, David remained for a trustees' meeting, and Carol walked home with some of the younger ones of the congregation. When they asked if she wished them to wait with her for David she shook her head, smiling gratefully but with weariness.

"No, thank you. I am going right straight to bed. I am tired."