He came back in a few minutes, but so transformed in outward appearance that Ducie scarcely knew him.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Argosy, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Argosy

Vol. 51, No. 3, March, 1891

Author: Various

Editor: Charles W. Woods

Release Date: May 11, 2006 [EBook #18373]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ARGOSY ***

Produced by Paul Murray, Taavi Kalju and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Publishers in Ordinary to Her Majesty.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY OGDEN, SMALE AND CO. LIMITED,

GREAT SAFFRON HILL, E.C.

| PAGE | ||

| The Fate of the Hara Diamond. Illustrated by M.L. Gow. | ||

| Chap. I. | My Arrival at Deepley Walls | Jan |

| II. | The Mistress of Deepley Walls | Jan |

| III. | A Voyage of Discovery | Jan |

| IV. | Scarsdale Weir | Jan |

| V. | At Rose Cottage | Feb |

| VI. | The Growth of a Mystery | Feb |

| VII. | Exit Janet Hope | Feb |

| VIII. | By the Scotch Express | Feb |

| IX. | At "The Golden Griffin" | 177 |

| X. | The Stolen Manuscript | 182 |

| XI. | Bon Repos | 189 |

| XII. | The Amsterdam Edition of 1698 | 194 |

| XIII. | M. Platzoff's Secret—Captain Ducie's Translation of M. Paul Platzoff's MS | 199 |

| XIV. | Drashkil-Smoking | Apr |

| XV. | The Diamond | Apr |

| XVI. | Janet's Return | Apr |

| XVII. | Deepley Walls after Seven Years | Apr |

| XVIII. | Janet in a New Character | May |

| XIX. | The Dawn of Love | May |

| XX. | The Narrative of Sergeant Nicholas | May |

| XXI. | Counsel taken with Mr. Madgin | May |

| XXII. | Mr. Madgin at the Helm | Jun |

| XXIII. | Mr. Madgin's Secret Journey | Jun |

| XXIV. | Enter Madgin Junior | Jun |

| XXV. | Madgin Junior's First Report | Jun |

| * * * * * | ||

| The Silent Chimes. By Johnny Ludlow (Mrs. Henry Wood). | ||

| Putting Them Up | Jan | |

| Playing Again | Feb | |

| Ringing at Midday | 207 | |

| Not Heard | Apr | |

| Silent for Ever | May | |

| * * * * * | ||

| The Bretons at Home. By Charles W. Wood, F.R.G.S. With 35 Illustrations | Jan, Feb, 225, Apr, May, Jun | |

| * * * * * | ||

| About the Weather | Jun | |

| Across the River. By Helen M. Burnside | Apr | |

| After Twenty Years. By Ada M. Trotter | Feb | |

| A Memory. By George Cotterell | Feb | |

| A Modern Witch | Jan | |

| An April Folly. By Gilbert H. Page | Apr | |

| A Philanthropist. By Angus Grey | Jun | |

| Aunt Phœbe's Heirlooms: An Experience in Hypnotism | Feb | |

| A Social Debut | 244 | |

| A Song. By G.B. Stuart | Jan | |

| Enlightenment. By E. Nesbit | Feb | |

| In a Bernese Valley. By Alexander Lamont | Feb | |

| Legend of an Ancient Minster. By John Græme | 258 | |

| Longevity. By W.F. Ainsworth, F.S.A. | Apr | |

| Mademoiselle Elise. By Edward Francis | Jun | |

| Mediums and Mysteries. By Narissa Rosavo | Feb | |

| Miss Kate Marsden | Jan | |

| My May Queen. By John Jervis Beresford, M.A. | May | |

| Old China | Jun | |

| On Letter-Writing. By A.H. Japp, LL.D. | May | |

| Paul. By the Author of "Adonais, Q.C." | May | |

| "Proctorised" | Apr | |

| Rondeau. By E. Nesbit | 202 | |

| Saint or Satan? By A. Beresford | Feb | |

| Sappho. By Mary Grey | 203 | |

| Serenade. By E. Nesbit | Jun | |

| Sonnets. By Julia Kavanagh | Jan, Feb, Apr, Jun | |

| So Very Unattractive! | Jun | |

| Spes. By John Jervis Beresford, M.A. | Apr | |

| Sweet Nancy. By Jeanie Gwynne Bettany | May | |

| The Church Garden. By Christian Burke | May | |

| The Only Son of his Mother. By Letitia McClintock | 259 | |

| To my Soul. From the French of Victor Hugo | Jun | |

| Unexplained. By Letitia McClintock | Apr | |

| Who Was the Third Maid? | Jan | |

| Winter in Absence | Feb | |

| * * * * * | ||

| POETRY. | ||

| Sonnets. By Julia Kavanagh | Jan, Feb, Apr, Jun | |

| A Song. By G.B. Stuart | Jan | |

| Enlightenment. By E. Nesbit | Feb | |

| Winter in Absence | Feb | |

| A Memory. By George Cotterell | Feb | |

| In a Bernese Valley. By Alexander Lamont | Feb | |

| Rondeau. By E. Nesbit | 202 | |

| Spes. By John Jervis Beresford, M.A. | Apr | |

| Across the River. By Helen M. Burnside | Apr | |

| My May Queen. By John Jervis Beresford, M.A. | May | |

| The Church Garden. By Christian Burke | May | |

| Serenade. By E. Nesbit | Jun | |

| To my Soul. From the French of Victor Hugo | Jun | |

| Old China | Jun | |

| * * * * * | ||

| ILLUSTRATIONS. | ||

| By M.L. Gow. | ||

| "I advanced slowly up the room, stopped, and curtsied." | ||

| "I saw and recognised the mysterious midnight visitor." | ||

| "He came back in a few minutes, but so transformed in outward appearance that Ducie scarcely knew him." | ||

| "Behold!" | ||

| "Sister Agnes knelt for a few moments and bent her head in silent prayer." | ||

| "He put his hand to his side, and motioned Mirpah to open the letter." | ||

| * * * * * | ||

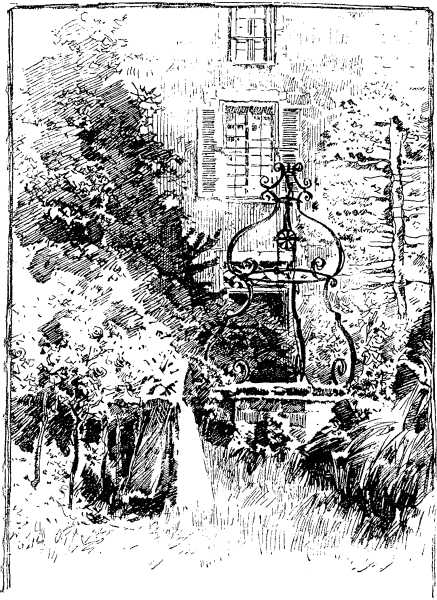

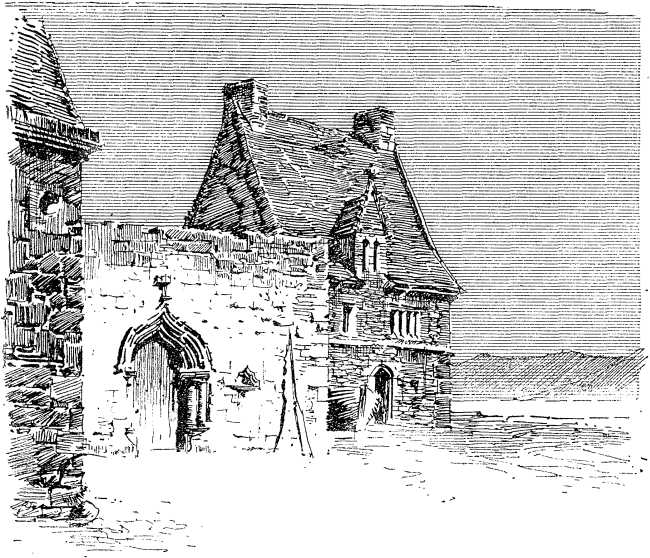

| Illustrations to "The Bretons at Home." |

Captain Edmund Ducie was one of the first to emerge from the wreck. He crept out of the broken window of the crushed-up carriage, and shook himself as a dog might have done. "Once more a narrow squeak for life," he said, half aloud. "If I had been worth ten thousand a-year, I should infallibly have been smashed. Not being worth ten brass farthings, here I am. What has become of my little Russian, I wonder?"

No groan or cry emanated from that portion of the broken carriage out of which Captain Ducie had just crept. Could it be possible that Platzoff was killed?

With considerable difficulty Ducie managed to wrench open the smashed door. Then he called the Russian by name; but there was no answer. He could discern nothing inside save a confused heap of rugs and minor articles of luggage. Under these, enough in themselves to smother him, Platzoff must be lying. One by one these articles were fished out of the carriage, and thrown aside by Ducie. Last of all he came to Platzoff, lying in a heap, white and insensible, as one already dead.

Putting forth all his great strength, Ducie lifted the senseless body out of the carriage as carefully and tenderly as though it were that of a new-born child. He then saw that the Russian was bleeding from an ugly jagged wound at the back of his head. There was no trace of any other outward hurt. A faint pulsation of the heart told that he was still alive.

On looking round, Ducie saw that there was a large country tavern only a few hundred yards from the scene of the accident. Towards this house, which announced itself to the world under the title of "The Golden Griffin," he now hastened with long measured strides, carrying the still insensible Russian in his arms. In all, some half[Pg 178]-dozen carriages had come over the embankment. The shrieks and cries of the wounded passengers were something appalling. Already the passengers in the fore part of the train, who had escaped unhurt, together with the officials and a few villagers who happened to be on the spot, were doing their best to rescue these unfortunates from the terrible wreckage in which they were entangled.

Captain Ducie was the first man from the accident to cross the threshold of "The Golden Griffin." He demanded to be shown the best spare room in the house. On the bed in this room he laid the body of the still insensible Platzoff. His next act was to despatch a mounted messenger for the nearest doctor. Then, having secured the services of a brisk, steady-nerved chambermaid, he proceeded to dress the wound as well as the means at his command would allow of—washing it, and cutting away the hair, and, by means of some ice, which he was fortunate enough to procure, succeeding in all but stopping the bleeding, which, to a man so frail of body, so reduced in strength as Platzoff, would soon have been fatal. A teaspoonful of brandy administered at brief intervals did its part as a restorative, and some minutes before the doctor's arrival Ducie had the satisfaction of seeing his patient's eyes open, and of hearing him murmur faintly a few soft guttural words in some language which the Captain judged to be his native Russ.

Platzoff had quite recovered his senses by the time the doctor arrived, but was still too feeble to do more than whisper a few unconnected words. There were many claimants this forenoon on the doctor's attention, and the services required by Platzoff at his hands had to be performed as expeditiously as possible.

"You must make up your mind to be a guest of 'The Golden Griffin' for at least a week to come," he said, as he took up his hat preparatory to going. "With quiet, and care, and a strict adherence to my instructions, I daresay that by the end of that time you will be sufficiently recovered to leave here for your own home. Humanly speaking, sir, you owe your life to this gentleman," indicating Ducie. "But for his skill and promptitude you would have been a dead man before I reached you."

Platzoff's thin white hand was extended feebly. Ducie took it in his sinewy palms and pressed it gently. "You have this day done for me what I can never forget," whispered the Russian, brokenly. Then he closed his eyes, and seemed to sink off into a sleep of exhaustion.

Leaving strict injunctions with the chambermaid not to quit the room till he should come back, Captain Ducie went downstairs with the intention of revisiting the scene of the disaster. He called in at the bar to obtain his favourite "thimbleful" of cognac, and there he found a very agreeable landlady, with whom he got into conversation respecting the accident. Some five minutes had passed thus when the chambermaid came up to him. "If you please, sir, the foreign gentleman has woke up, and is anxiously asking to see you."[Pg 179]

With a shrug of the shoulders and a slight lowering of his black eyebrows, Captain Ducie went back upstairs. Platzoff's eager eyes fixed him as he entered the room. Ducie sat down close by the bed and said in a kindly tone: "What is it? What can I do for you? Command me in any way."

"My servant—where is he? And—and my despatch box. Valuable papers. Try to find it."

Ducie nodded and left the room. The inquiries he made soon elicited the fact that Platzoff's servant had been even more severely injured than his master, and was at that moment lying, more dead than alive, in a little room upstairs. Slowly and musingly, with hands in pocket, Captain Ducie then took his way towards the scene of the accident. "It may suit my book very well to make friends with this Russian," he thought as he went along. "He is no doubt very rich; and I am very poor. In us the two extremes meet and form the perfect whole. He might serve my purposes in more ways than one, and it is just as likely that his purposes might be served by me: for a man like that must have purposes that want serving. Nous verrons. Meanwhile, I am his obedient servant to command."

Captain Ducie, hunting about among the débris of the train, was not long in finding the fragments of M. Platzoff's despatch box. Its contents were scattered about. Ducie spent ten minutes in gathering together the various letters and documents which it had contained. Then, with the broken box under his arm and the papers in his hands, he went back to the Russian.

He showed the papers one by one to Platzoff, who was strangely eager in the matter. When Ducie held up the last of them, Platzoff groaned and shut his eyes. "They are all there as far as I can judge," he murmured, "except the most important one of all—a paper covered with figures, of no use to anyone but myself. Oh, dear Captain Ducie! do please go once more and try to find the one that is still missing. If I only knew that it was burnt, or torn into fragments, I should not mind so much. But if it were to fall into the hands of a scoundrel skilful enough to master the secret which it contains, then I—"

He stopped with a scared look on his face, as though he had unwittingly said more than he had intended.

"Pray don't trouble yourself with any explanations just now," said Ducie. "You want the paper: that is enough. I will go and have a thorough hunt for it."

Back went Ducie to the broken carriages and began to search more carefully than before. "What can be the nature of the great secret, I wonder, that is hidden between the Sibylline leaves I am in search of? If what Platzoff's words implied be true, he who learns it is master of the situation. Would that it were known to me!"

Slowly and carefully, inside and out of the carriage in which he and Platzoff had travelled, Captain Ducie conducted his search. One[Pg 180] by one he again turned over the wraps and different articles of personal luggage belonging to both of them, which had not yet been removed. The first object that rewarded his search was a splendid diamond pin which he remembered having seen in Platzoff's scarf. Ducie picked it up and looked cautiously around. No one was regarding him. "Of the first water and worth a hundred guineas at the very least," he muttered. Then he put it in his waistcoat pocket and went on with his search.

A minute or two later, hidden away under one of the cushions of the carriage, he found what he was looking for: a folded sheet of thick blue paper covered with a complicated array of figures—that and nothing more.

Captain Ducie regarded the recovered treasure with a strange mixture of feelings. His hands trembled slightly; his heart was beating more quickly than usual; his eyes seemed to see and yet not to see the paper in his hands. As one mazed and in deep doubt he stood.

His reverie was broken by the approach of some of the railway officials. The cloud vanished from before his eyes, and he was his cool, imperturbable self in a moment. Heading the long array of figures on the parchment were a few lines of ordinary writing, written, however, not in English, but Italian. These few lines Ducie now proceeded to read over more attentively than he had done at the first glance. He was sufficiently master of Italian to be able to translate them without much difficulty. Translated they ran as under:—

"Bon Repos,

"Windermere.

"Carlo mio,—In the Amsterdam edition of 1698 of The Confessions of Parthenio the Mystic occur the passages given below. To your serious consideration, O friend of my heart, I recommend these words. To read them much patience is required. But they are freighted with wisdom, as you will discover long before you reach the end of them, and have a deep significance for that great cause to which the souls of both of us are knit by bonds which in this life can never be severed. When you read these lines, the hand that writes them will be cold in the grave. But Nature allows nothing to be lost, and somewhere in the wide universe the better part of me (the mystic Ego) will still exist; and if there be any truth in the doctrine of the affinity of souls, then shall you and I meet again elsewhere. Till that time shall come—Adieu!

"Thine,

"Paul Platzoff."

Having carefully read these lines twice over, Captain Ducie refolded the paper, put it away in an inner pocket, and buttoned his coat over it. Then he took his way, deep in thought, back to "The Golden Griffin."[Pg 181]

The Russian's eager eyes asked him: "What success?" before he could say a word.

"I am sorry to say that I have not been able to find the paper," said Captain Ducie in slow, deliberate tones. "I have found something else—your diamond pin, which you appear to have lost out of your scarf."

Platzoff gazed at him with a sort of blank despair on his saffron face, but a low moan was his only reply. Then he turned his face to the wall and shut his eyes.

Captain Ducie was a patient man, and he waited without speaking for a full hour. At the end of that time Platzoff turned, and held out a feeble hand.

"Forgive me, my friend—if you will allow me to call you so," he said. "I must seem horribly ungrateful after all the trouble I have put you to, but I do not feel so. The loss of my MS. affected me so deeply for a little while that I could think of nothing else. I shall get over it by degrees."

"If I remember rightly," remarked Ducie, "you said that the lost MS. was merely a complicated array of figures. Of what possible value can it be to anyone who may chance to find it?"

"Of no value whatever," answered Platzoff, "unless they who find it should also be skilful enough to discover the key by which alone it can be read; for, as I may now tell you, there is a hidden meaning in the figures. The finders may or may not make that discovery, but how am I to ascertain what is the fact either one way or the other? For want of such knowledge my sense of security will be gone. I would almost prefer to know for certain that the MS. had been read than be left in utter doubt on the point. In the one case I should know what I had to contend against, and could take proper precautionary measures; in the other, I am left to do battle with a shadow that may or may not be able to work me harm."

"Would possession of the information that is contained in the MS. enable anyone to work you harm?"

"It would to this extent, that it would put them in possession of a cherished secret, which—But why talk of these things? What is done cannot be undone. I can only prepare myself for the worst."

"One moment," said Ducie. "I think that after the thorough search made by me the chances are twenty to one against the MS. ever being found. But granting that it does turn up, the finder of it will probably be some ignorant navvie or incurious official, without either inclination or ability to master the secret of the cipher."

Ten days later M. Platzoff was sufficiently recovered to set out for Bon Repos. At his earnest request Ducie had put off his own journey to stay with him. At another time the ex-Captain might not have cared to spend ten days at a forlorn country tavern, even with a rich Russian; but as he often told himself he had "his book to[Pg 182] make," and he probably looked upon this as a necessary part of the process. Before they parted, it was arranged that as soon as Ducie should return from Scotland he should go and spend a month at Bon Repos. Then the two shook hands, and each went his own way. As one day passed after another without bringing any tidings of the lost MS., Platzoff's anxiety respecting it seemed to lessen, and by the time he left "The Golden Griffin" he had apparently ceased to trouble his mind any further in the matter.

Captain Edmund Ducie came of a good family. His people were people of mark among the landed gentry of their county, and were well-to-do even for their position. Although only a fourth son, his allowance had been a very handsome one, both while at Cambridge and afterwards during the early years of his life in the army. When of age, he had come into the very nice little fortune, for a fourth son, of nine thousand pounds; and it was known that there would be "something handsome" for him at his father's death. He had a more than ordinary share of good looks; his mind was tolerably cultivated, and afterwards enlarged by travel and service in various parts of the world; in manners and address he was a finished gentleman of the modern school. Yet all these advantages of nature and fortune were in a great measure nullified and rendered of no avail by reason of one fatal defect, of one black speck at the core. In a word, Captain Ducie was a born gambler.

He had gambled when a child in the nursery, or had tried to gamble, for cakes and toys. He had gambled when at school for coppers, pocket-knives, and marbles. He had gambled when at the University, and had felt the claws of the Children of Usury. He gambled away his nine thousand pounds, or such remainder of it as had not been forestalled, when he came of age. Later on, when in the army, and on home allowance again, for his father would not let him starve, he had kept on gambling; so that when, some five years later, his father died, and he dropped in for the "something handsome," two-thirds of it had to be paid down on the nail to make a free man of him again. On the remaining one-third he contrived to keep afloat for a couple of years longer; then, after a season of heavy losses, came the final crash, and Captain Ducie found himself under the necessity of selling his commission, and of retiring into private life.

From this date Captain Ducie was compelled to live by "bleeding" his friends and connections. He was a great favourite among them, and they rallied gallantly to his rescue. But Ducie still gambled; and the best of friends, and the most indulgent of relatives, grew[Pg 183] tired after a time of seeing their cherished gold pieces slip heedlessly through the fingers of the man whom it was intended that they should substantially help, and be lost in the foul atmosphere of a gaming-house. One by one, friend and relative dropped away from the doomed man, till none were left. Little by little the tide of fortune ebbed away from his feet, leaving him stranded high and dry on the cruel shore of impecuniosity, hemmed in by a thousand debts, with the gaunt wolf of beggary staring him in the face.

There was one point about Captain Ducie's gambling that redounded to his credit. No one ever suspected him of cheating. His "run of luck" was so uniformly bad, despite a brief fickle gleam of fortune now and again, which seemed sent only to lure him on to deeper destruction; it was so well known that he had spent two fortunes and alienated all his friends through his passion for the green cloth, that it would have been the height of absurdity to even suspect him of roguery. Indeed, "Ducie's luck" was a proverbial phrase at the whist-tables of his club. He was not a "turf" man, and had no knowledge of horses beyond that legitimate knowledge which every soldier ought to have. His money had all been lost either at cards or roulette. He was one of the most imperturbable of gamblers. Whatever the varying chances of the game might be, no man ever saw him either elated or depressed: he fought with his vizor down.

No man could be more aware of his one besetting weakness, nor of his inability to conquer it, than was Captain Ducie. When he could no longer muster five pounds to gamble with, he would gamble with five shillings. There was a public-house in Southwark to which, poorly dressed, he sometimes went when his funds were low. Here, unknown to the police, a little quiet gambling for small stakes went on from night to night. But however small might be the amount involved, there was the passion, the excitement, the gambling contagion, precisely as at Homburg or Baden; and these it was that made the very salt of Captain Ducie's life.

About six months before we made his acquaintance he had been compelled to leave his pleasant suite of apartments in New Bond Street, and had, since that time, been the tenant of a shabby bed-room in a shabby little out-of-the-way street. When in town he took his meals at his club, and to that address all letters and papers for him were sent. But of late even the purlieus of his club had become dangerous ground. Round the palatial portal duns seemed to hover and flit mysteriously, so that the task of reaching the secure haven of the smoking-room was one of danger and difficulty; while the return voyage to the shabby little bed-room in the shabby little street could be accomplished in safety only by frequent tacking and much skilful pilotage, to avoid running foul of various rocks and quicksands by the way.

But now, after a six weeks' absence in Scotland, Captain Ducie[Pg 184] felt that for a day or two at least he was tolerably safe. He felt like an old fox venturing into the open after the noise of the hunt has died away in the distance, who knows that for a little while he is safe from molestation. How delightful town looked, he thought, after the dull life he had been leading at Stapleton. He had managed to screw another fifty pounds out of Barnstake, and this very evening, the first of his return, he would go to Tom Dawson's rooms and there refresh himself with a little quiet faro or chicken-hazard: very quiet it must of necessity be, unless he saw that it was going to turn out one of his lucky evenings, in which case he would try to "put up" the table and finish with a fortunate coup. But there was one little task that he had set himself to do before going out for the evening, and he proceeded to consider it over while discussing his cup of strong green tea and his strip of dry toast.

To aid him in considering the matter he brought out of an inner pocket the stolen manuscript of M. Platzoff.

While in Scotland, when shut up in his own room of a night, he had often exhumed the MS., and had set himself seriously to the task of deciphering it, only to acknowledge at the end of a terrible half-hour that he was ignominiously beaten. Whereupon he would console himself by saying that such a task was "not in his line," that his brains were not of that pettifogging order which would allow of his sitting down with the patience requisite to master the secret of the figures. To-night, for the twentieth time, he brought out the MS. He again read the prefatory note carefully over, although he could almost have said it by heart, and once more his puzzled eyes ran over the complicated array of figures, till at last, with an impatient "Pish!" he flung the MS. to the other side of the table, and poured out for himself another cup of tea.

"I must send it to Bexell," he said to himself. "If anyone can make it out, he can. And yet I don't like making another man as wise as myself in such a matter. However, there is no help for it in the present case. If I keep the MS. by me till doomsday I shall never succeed in making out the meaning of those confounded figures."

When he had finished his tea he took out his writing desk and wrote as under:

"My Dear Bexell,—I have only just got back from Scotland after an absence of six weeks. I have brought with me a severe catarrh, a new plaid, a case of Mountain Dew, and a MS. written in cipher. The first and second of these articles I retain for my own use. Of the third I send you half-a-dozen bottles by way of sample: a judicious imbibition of the contents will be found to be a sovereign remedy for the Pip and other kindred disorders that owe their origin to a melancholy frame of mind. The fourth article on my list I send you bodily. It has been lent to me by a friend of mine who states that he found it in his muniment chest among a lot of old[Pg 185] title deeds, leases, etc., the first time he waded through them after coming into possession of his property. Neither he nor any friend to whom he has shown it can make out its meaning, and I must confess to being myself one of the puzzled. My friend is very anxious to have it deciphered, as he thinks it may in some way relate to his property, or to some secret bit of family history with which it would be advisable that he should become acquainted. Anyhow, he gave it to me to bring to town, with a request that I should seek out someone clever in such things, and try to get it interpreted for him. Now I know of no one except yourself who is at all expert in such matters. You, I remember, used to take a delight that to me was inexplicable in deciphering those strange advertisements which now and again appear in the newspapers. Let me therefore ask of you to bring your old skill to bear in the present case, and if you can make me anything like a presentable translation to send back to my friend the laird, you will greatly oblige

"Your friend,

"E. Ducie."

The MS. consisted of three or four sheets of deed-paper fastened together at one corner with silk. The prefatory note was on the first sheet. This first sheet Ducie cut away with his penknife and locked up in his desk. The remaining sheets he sent to his friend Bexell, together with the note which he had written.

Three days later Mr. Bexell returned the sheets with his reply. In order properly to understand this reply it will be necessary to offer to the reader's notice a specimen of the MS. The conclusion arrived at by Mr. Bexell, and the mode by which he reached them, will then be more clearly comprehensible.

The following is a counterpart of the first few lines of the MS.:

| 253.12 | 59.25 | 14.5 | 96.14 | 158.49 | 1.29 | 465.1 | 28.53 | |

| 4 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 1 | |

| 16.36 | 151.18 | 58.7 | 14.29 | 368.1 | 209.18 | 43.11 | 1.31 | 1.1 |

| 11 | 3 | 9 | 8 | |||||

| 29.6 | 186.9 | 204.11 | 86.19 | 43.16 | 348.14 | 196.29 | 203.5 | |

| 4 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 2 | |

| 186.9 | 1.31 | 21.10 | 143.18 | 200.6 | 29.40 | 408.9 | 61.5 | |

| 5 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 4 | |

| 209.11 | 496.1 | 24.24 | 28.59 | 69.39 | 391.10 | 60.13 | 200.1 | |

| 2 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 11 | 5 | 3 |

The following is Mr. Bexell's reply to his friend Captain Ducie:

"My Dear Ducie,—With this note you will receive back your confounded MS., but without a translation. I have spent a good deal of time and labour in trying to decipher it, and the conclusions at which I have arrived may be briefly laid before you.

1. Each group of three sets of figures represents a word.

2. Each group of two sets of figures—those with a line above and a line below—represents a letter only.[Pg 186]

3. Those letters put together from the point where the double line begins to the point where it ceases, make up a word.

4. In the composition of this cryptogram a book has been used as the basis on which to work.

5. In every group of three sets of figures the first set represents the page of the book; the second, the number of the line on that page, probably counting from the top; the third the position in ordinary rotation of the word on that line. Thus you have the number of the page, the number of the line, and the number of the word.

6. In the case of the interlined groups of two sets of figures, the first set represents the number of the page; the second set the number of the line, probably counting from the top, of which line the required letter will prove to be the initial one.

7. The words thus spelled out by the interlined groups of double figures are, in all probability, proper names, or other uncommon words not to be found in their entirety in the book on which the cryptogram is based, and consequently requiring to be worked out letter by letter.

8. The book in question is not a dictionary, nor any other work the words of which come in alphabetical rotation. It is probably some ordinary book, which the writer of the cryptogram and the person for whom it is written have agreed upon beforehand to make use of as a key. I have no means of judging whether the book in question is an English or a foreign one, but by it alone, whatever it may be, can the cryptogram be read.

"Now, my dear Ducie, it would be wearisome for me to describe, and equally wearisome for you to read, the processes of reasoning by means of which the above deductions have been arrived at. But in order to satisfy you that my assumptions are not entirely fanciful or destitute of sober sense, I will describe to you, as briefly as may be, the process by means of which I have come to the conclusion that the book used as the basis of the cryptogram was not a dictionary or other work in which the words come in alphabetical rotation; and such a conclusion is very easy of proof.

"In a document so lengthy as the MS. of your friend the Scotch laird there must of necessity be many repetitions of what may be called 'indispensable words'—words one or more of which are used in the composition of almost every long sentence. I allude to such words as a, an, and, as, of, by, the, their, them, these, they, you, I, it, etc. The first thing to do was to analyse the MS. and classify the different groups of figures for the purpose of ascertaining the number of repetitions of any one group. My analysis showed me that these repetitions were surprisingly few. Forty groups were repeated twice, fifteen three times, and nine groups four times. Now, according to my calculation, the MS. contains one thousand two hundred and eighty-three words. Out of those one thousand two hundred and[Pg 187] eighty-three words there must have been more than the number of repetitions shown by my analysis, and not of one only, but of several of what I have called 'indispensable words.' Had a dictionary been made use of by the writer of the MS. all such repetitions would have been referred to one particular page, and to one particular line of that page: that is to say, in every case where a word repeated itself in the MS. the same group of numbers would in every case have been its valeur. As the repetitions were so few I could only conclude that some book of an ordinary kind had been made use of, and that the writer of the cryptogram had been sufficiently ingenious not to repeat his numbers very frequently in the case of 'indispensable words,' but had in the majority of cases given a fresh group of numbers at each repetition of such a word. I might, perhaps, go further and say that in the majority of cases where a group of figures is repeated such group refers to some word less frequently used than any of those specified above, and that one group was obliged to do duty on two or more occasions, simply because the writer was unable to find the word more than once in the book on which his cryptogram was based.

"Having once arrived at the conclusion that some book had been used as the basis of the cryptogram, my next supposition that each group of three sets of numbers showed the page of the book, the number of the line from the top, and the position of the required word in that line, seemed at once borne out by an analysis of the figures themselves. Thus, taking the first set of figures in each group, I found that in no case did they run to a higher number than 500, which would seem to indicate that the basis-book was limited to that number of pages. The second set of figures ran to no higher number than 60, which would seem to limit the lines on each page to that number. The third set of figures in no case yielded a higher number than 12, which numerals, according to my theory, would indicate the maximum number of words in each line. Thus you have at once (if such information is of any use to you) a sort of a key to the size of the required volume.

"I think I have now written enough, my dear Ducie, to afford you some idea of the method by means of which my conclusions have been arrived at. If you wish for further details I will supply them—but by word of mouth, an it be all the same to your honour; for this child detests letter-writing, and has taken a vow that if he reach the end of his present pen-and-ink venture in safety, he will never in time to come devote more than two pages of cream note to even the most exacting of friends: the sequitur of which is, that if you want to know more than is here set down you must give the writer a call, when you shall be talked to to your heart's content.

"Your exhausted friend,

"Geo. Bexell."

Captain Ducie had too great a respect for the knowledge of his[Pg 188] friend Bexell in matters like the one under review to dream for one moment of testing the validity of any of his conclusions. He accepted the whole of them as final. Having got the conclusions themselves, he cared nothing as to the processes by which they had been deduced: the details interested him not at all. Consequently he kept out of the way of his friend, being in truth considerably disgusted to find that, so far as he was himself concerned, the affair had ended in a fiasco. He could not look upon it in any other light. It was utterly out of the range of probability that he should ever succeed in ascertaining on what particular book the cryptogram was based, and no other knowledge was now of the slightest avail. He was half inclined to send back the MS. anonymously to Platzoff, as being of no further use to himself; but he was restrained by the thought that there was just a faint chance that the much-desired volume might turn up during his forthcoming visit to Bon Repos—that even at the eleventh hour the key might be found.

He was terribly chagrined to think that the act of genteel petty larceny, by which he had lowered himself more in his own eyes than he would have cared to acknowledge, had been so absolutely barren of results. That portion of his moral anatomy which he would have called his conscience pricked him shrewdly now and again, but such pricks had their origin in the fact of his knavery having been unsuccessful. Had his wrong-doing won for him such a prize as he had fondly hoped to gain by its means, Conscience would have let her rusted spear hang unheeded on the wall, and beyond giving utterance now and then to a faint whisper in the dead of night, would have troubled him not at all.

It was some time in the middle of the night, about a week after Bexell had sent him back the papers, that he awoke suddenly and completely, and there before him, as clearly as though it had been written in letters of fire on the black wall, he saw the title of the wished-for book. It was the book mentioned by Platzoff in his prefatory note: The Confessions of Parthenio the Mystic. The knowledge had come to him like a revelation. How stupid he must have been never to have thought of it before! That night he slept no more.

Next morning he went to one of the most famous bookdealers in the metropolis. The book inquired for by Ducie was not known to the man. But that did not say that there was no such work in existence. Through his agents at home and abroad inquiry should be made, and the result communicated to Captain Ducie. Therewith the latter was obliged to content himself. Three days later came a pressing note of invitation from Platzoff.

On a certain fine morning towards the end of May, Captain Ducie took train at Euston Square, and late the same afternoon was set down at Windermere. A fly conveyed himself and his portmanteau to the edge of the lake. Singling out one from the tiny fleet of pleasure boats always to be found at the Bowness landing-stage, Captain Ducie seated himself in the stern and lighted his cigar. The boatman's sinewy arms soon pulled him out into the middle of the lake, when the head of the little craft was set for Bon Repos.

The sun was dipping to the western hills. In his wake he had left a rack of torn and fiery cloud, as though he had rent his garments in wrath and cast them from him. Soft, grey mists and purple shadows were beginning to strike upward from the vales, but on the great shoulders of Fairfield, and on the scarred fronts of other giants further away, the sunshine lingered lovingly. It was like the hand of Childhood caressing the rugged brows of Age.

With that glorious panorama which crowns the head of the lake before his eyes, with the rhythmic beat of the oars and the soft pulsing of the water in his ears, with the blue smoke-rings of his cigar rising like visible aspirations through the evening air, an unwonted peace, a soft brooding quietude, began to settle down upon the Captain's world-worn spirit; and through the stillness came a faint whisper, like his mother's voice speaking from the far-off years of childhood, recalling to his memory things once known, but too long forgotten; lessons too long despised, but with a vital truth underlying them which he seemed never to have realised till now. Suddenly the boat's keel grazed the shingly strand, and there before him, half shrouded in the shadows of evening, was Bon Repos.

A genuine north-country house, strong, rugged and homely-looking, despite its Gallic cognomen. It was built of the rough grey stone of the district, and roofed with large blue slates. It stood at the head of a small lawn that sloped gently up from the lake. Immediately behind the house a precipitous hill, covered with a thick growth of underwood and young trees, swept upward to a considerable height. A narrow, winding lane, the only carriage approach to the house, wound round the base of this hill, and joined the high road a quarter of a mile away. The house was only two stories high, but was large enough to have accommodated a numerous and well-to-do family. The windows were all set in a framework of plain stone, but on the lower floor some of them had been modernised, the small, square, bluish panes having given place to polished plate glass, of which two panes only were needed for each window. But this was an innovation that had not spread far. The lawn was bordered with a tasteful[Pg 190] diversity of shrubs and flowers, while here and there the tender fingers of some climbing plant seemed trying to smoothe away a wrinkle in the rugged front of the old house.

Captain Ducie walked up the gravelled pathway that led from the lake to the house, the boatman with his portmanteau bringing up the rear. Before he could touch either bell or knocker, the door was noiselessly opened, and a coloured servant, in a suit of plain black, greeted him with a respectful bow.

"Captain Ducie, sir, if I am not misinformed?"

"I am Captain Ducie."

"Sir, you are expected. Your rooms are ready. Dinner will be served in half-an-hour from now. My master will meet you when you come downstairs."

The portmanteau having been brought in, and the boatman paid and dismissed, said the coloured servant: "I will show you to your rooms, if you will allow me to do so. The man appointed to wait upon you will follow with your luggage in a minute or two."

He led the way, and Ducie followed in silence.

The tired Captain gave a sigh of relief and gratitude, and flung himself into an easy-chair as the door closed behind his conductor. His two rooms were en suite, and while as replete with comfort as the most thorough-going Englishman need desire, had yet about them a touch of lightness and elegance that smacked of a taste that had been educated on the Continent, and was unfettered by insular prejudices.

"At Stapleton I had a loft that was hardly fit for a groom to sleep in; here I have two rooms that a cardinal might feel proud to occupy. Vive la Russie!"

M. Platzoff was waiting at the foot of the staircase when Ducie went down. A cordial greeting passed between the two, and the host at once led the way to the dining-room. Platzoff in his suit of black and white cravat, with his cadaverous face, blue-black hair and chin-tuft, and the elaborate curl on the top of his forehead, looked, at the first glance, more like a ghastly undertaker's man than the host of an English country house.

But a second glance would have shown you his embroidered linen and the flashing gems on his fingers; and you could not be long with him without being made aware that you were in the company of a thorough man of the world—of one who had travelled much and observed much; of one whose correspondents kept him au courant with all the chief topics of the day. He knew, and could tell you, the secret history of the last new opera; how much had been paid for it, what it had cost to produce, and all about the great green-room cabal against the new prima donna. He knew what amount of originality could be safely claimed for the last new drama that was taking the town by storm, and how many times the same story had been hashed up before. He had read the last French novel of any[Pg 191] note, and could favour you with a few personal reminiscences of its author not generally known. As regarded political knowledge—if all his statements were to be trusted—he was informed as to much that was going on behind the great drop-scene. He knew how the wires were pulled that moved the puppets who danced in public, especially those wires which were pulled in Paris, Vienna and St. Petersburg. Before Ducie had been six hours at Bon Repos he knew more about political intrigues at home and abroad than he had ever dreamt of in the whole course of his previous life.

The dining-room at Bon Repos was a long low-ceilinged apartment, panelled with black oak, and fitted up in a rich and sombre style that was yet very different from the dull, heavy formality that obtains among three-fourths of the dining-rooms in English country houses. Indeed, throughout the appointments and fittings of Bon Repos there was a touch of something Oriental grafted on to French taste, combined with a thorough knowledge and appreciation of insular comfort. From the dining-room windows a lovely stretch of the lake could be seen glimmering in the starlight, and our two friends sat this evening over their wine by the wide open sash, gazing out into the delicious night. Behind them, in the room, two or three candles were burning in silver sconces; but at the window they were sitting in that sort of half light which seems exactly suited for confidential talk. Captain Ducie took advantage of it after a time to ask his host a question which he would perhaps have scarcely cared to put by broad daylight.

"Have you heard any news of your lost manuscript?"

"None whatever," answered Platzoff. "Neither do I expect, after this lapse of time, to hear anything further concerning it. It has probably never been found, or if found, has (as you suggested at 'The Golden Griffin') fallen into the hands of someone too ignorant, or too incurious, to master the secret of the cipher."

"It has been much in my thoughts since I saw you last," said Ducie. "Was the MS. in your own writing, may I ask?"

"It was in my own writing," answered the Russian. "It was a confidential communication intended for the eye of my dearest friend, and for his eye only. It was unfinished when I lost it. I had been staying a few days at one of your English spas when I joined you in the train on the day of the accident. The MS., as far as it went, had all been written before I left home; but I took it with me in my despatch-box, together with other private papers, although I knew that I could not add a single line to it while I should be from home. I have wished a thousand times since that I had left it behind me."

"I have heard of people to whom cryptography is a favourite study," said the Captain; "people who pride themselves on their ability to master the most difficult cipher ever invented. Let us hope that your MS. has not fallen into the hands of one of these clever individuals."

Platzoff shrugged his shoulders. "Let us hope so, indeed," he[Pg 192] said. "But I will not believe in any such untoward event. Too long a time has elapsed since the loss for me not to have heard something respecting the MS., had it been found by anyone who knew how to make use of it. Besides, I would defy the most clever reader of cryptography to master my MS. without—Ah, Bah! where's the use of talking about it? Should not you like some tobacco? Daylight's last tint has vanished, and there is a chill air sweeping down from the hills."

As they left the window, Platzoff added: "One of the most annoying features connected with my loss arises from the fact that all my labour will have to be gone through again—and very tedious work it is. I am now engaged on a second MS., which is, as nearly as I can make it, a copy of the first one; and it is a task which must be done by myself alone. To have even one confidant would be to stultify the whole affair. Another glass of claret, and then I will introduce you to my sanctum."

The coloured man who had opened the door for Captain Ducie had been in and out of the dining-room several times. He was evidently a favourite servant. Platzoff had addressed him as Cleon, and Ducie had now a question or two to ask concerning him.

Cleon was a mulatto, tall, agile and strong. Not bad-looking by any means, but carrying with him unmistakable traces of the negro blood in his veins. His hair was that of a genuine African—crisp and black, and was one mass of short curls; but except for a certain fulness of the lips his features were of the ordinary Caucasian type. He wore no beard, but a thin, straight line of black moustache. His complexion was yellow, but a different yellow from that of his master—dusky, passionate, lava-like; suggestive of fiery depths below. His eyes, too, glowed with a smothered fire that seemed as if it might blaze out at any moment, and there was in them an expression of snake-like treachery that made Captain Ducie shudder involuntarily, as though he had seen some loathsome reptile, the first time he looked steadily into their half-veiled depths. One look into each other's eyes was sufficient for both these men.

"Monsieur Cleon and I are born enemies, and he knows it as well as I do," murmured Ducie to himself, after the first secret signal of defiance had passed between the two. "Well, I never was afraid of any man in my life, and I'm not going to begin by being afraid of a valet." With that he shrugged his shoulders, and turned his back contemptuously on the mulatto.

Cleon, in his suit of black and white tie, with his quiet, stealthy movements and unobtrusive attentions, would have been pronounced good style as a gentleman's gentleman in the grandest of Belgravian mansions. Had he suddenly come into a fortune, and gone into society where his antecedents were unknown, five-sixths of his male associates would have pronounced him "a deuced gentlemanly fellow." The remaining one-sixth might have held a somewhat different opinion.[Pg 193]

"That coloured fellow seems to be a great favourite with you," remarked Ducie, as Cleon left the room.

"And well he may be," answered Platzoff. "On two separate occasions I owed my life to him. Once in South America, when a couple of brigands had me at their mercy and were about to try the temper of their knives on my throat. He potted them both one after the other. On the second occasion he rescued me from a tiger in the jungle, who was desirous of dining à la Russe. I have not made a favourite of Cleon without having my reasons for so doing."

"He seems to me a shrewd fellow, and one who understands his business."

"Cleon is not destitute of ability. When I settled at Bon Repos I made him major-domo of my small establishment, but he still retains his old position as my body-servant. I offered long ago to release him; but he will not allow any third person to come between himself and me, and I should not feel comfortable under the attentions of anyone else."

Platzoff opened the door as he ceased speaking and led the way to the smoking room.

As you lifted the curtain and went in, it was like passing at one step from Europe to the East—from the banks of Windermere to the shores of the Bosphorus. It was a circular apartment with a low cushioned divan running completely round it, except where broken by the two doorways, curtained with hangings of dark brown. The floor was an arabesque of different-coloured tiles, covered here and there with a tiny square of bright-hued Persian carpet. The walls were panelled with stamped leather to the height of six feet from the ground; above the panelling they were painted of a delicate cream colour with here and there a maxim or apophthegm from the Koran, in the Arabic character, picked out in different colours. From the ceiling a silver lamp swung on chains of silver. In the centre of the room was a marble table on which were pipes and hookahs, cigars and tobaccos of various kinds. Smaller tables were placed here and there close to the divan for the convenience of smokers.

Platzoff having asked Ducie to excuse him for five minutes, passed through the second doorway, and left the Captain to an undisturbed survey of the room. He came back in a few minutes, but so transformed in outward appearance that Ducie scarcely knew him. He had left the room in the full evening costume of an English gentleman: he came back in the turban and flowing robes of a follower of the Prophet. But however comfortable his Eastern habit might be, M. Platzoff lacked the quiet dignity and grave repose of your genuine Turkish gentleman.

"I am going to smoke one of these hookahs; let me recommend you to try another," said Platzoff as he squatted himself cross-legged on the divan.

He touched a tiny gong, and Cleon entered.[Pg 194]

"Select a hookah for Monsieur Ducie, and prepare it."

So Cleon, having chosen a pipe, tipped it with a new amber mouthpiece, charged the bowl with fragrant Turkish tobacco, handed the stem to Ducie, and then applied the light. The same service was next performed for his master. Then he withdrew, but only to reappear a minute or two later with coffee served up in the Oriental fashion—black and strong, without sugar or cream.

"This is one of my little smoke-nights," said Platzoff as soon as they were alone. "Last night was one of my big smoke-nights."

"You speak a language I do not understand."

"I call those occasions on which I smoke opium my big smoke-nights."

"Can it be true that you are an opium smoker?" said Ducie.

"It can be and is quite true that I am addicted to that so-called pernicious habit. To me it is one of the few good things this world has to offer. Opium is the key that unlocks the golden gates of Dreamland. To its disciples alone is revealed the true secret of subjective happiness. But we will talk more of this at some future time."

Captain Ducie soon fell into the quiet routine of life at Bon Repos. It was not distasteful to him. To a younger man it might have seemed to lack variety, to have impinged too closely on the verge of dulness; but Captain Ducie had reached that time of life when quiet pleasures please the most, and when much can be forgiven the man who sets before you a dinner worth eating. Not that Ducie had anything to forgive. Platzoff had contracted a great liking for his guest, and his hospitality was of that cordial quality which makes the object of it feel himself thoroughly at home. Besides this, the Captain knew when he was well off, and had no wish to exchange his present pleasant quarters, his rambles across the hills, and his sailings on the lake, for his dingy bed-room in town with the harassing, hunted down life of a man upon whom a dozen writs are waiting to be served, and who can never feel certain that his next day's dinner may not be eaten behind the locks and bars of a prison.

Sometimes on horseback, sometimes on foot, sometimes accompanied by his host, sometimes alone, Ducie explored the lovely country round Bon Repos to his heart's content. Another source of pleasure and healthful exercise he found in long solitary pulls up and down the lake in a tiny skiff which had been set apart for his service. In the evening came dinner and conversation with his host, with perhaps a game or two of billiards to finish up the day.

Captain Ducie found no scope for the exercise of his gambling proclivities at Bon Repos. Platzoff never touched card or dice. He[Pg 195] could handle a cue tolerably well, but beyond a half-crown game, Ducie giving him ten points out of fifty, he could never be persuaded to venture. If the Captain, when he went down to Bon Repos, had any expectation of replenishing his pockets by means of faro and unlimited loo, he was wretchedly mistaken. But whatever secret annoyance he might feel, he was too much a man of the world to allow his host even to suspect its existence.

Of society in the ordinary meaning of that word there was absolutely none at Bon Repos. None of the neighbouring families by any chance ever called on Platzoff. By no chance did Platzoff ever call on any of the neighbouring families.

"They are too good for me, too orthodox, too strait-laced," exclaimed the Russian one day in his quiet, jeering way. "Or it may be that I am not good enough for them. Any way, we do not coalesce. Rather are we like flint and steel, and eliminate a spark whenever we come in contact. They look upon me as a pagan, and hold me in horror. I look upon three-fourths of them as Pharisees, and hold them in contempt. Good people there are among them no doubt; people whom it would be a pleasure to know, but I have neither time, health, nor inclination for conventional English visiting—for your ponderous style of hospitality. I am quite sure that my ideas of men and manners would not coincide with those of the quiet country ladies and gentlemen of these parts; while theirs would seem to me terribly wearisome and jejune. Therefore, as I take it, we are better apart."

By and by Ducie discovered that his host was not so entirely isolated from the world as at first sight he appeared to be.

Occasional society there was of a certain kind, intermittent, coming and going like birds of passage. One, or sometimes two visitors, of whose arrival Ducie had heard no previous mention, would now and again put in an appearance at the dinner-table, would pass one, or at the most two nights at Bon Repos, and would then be seen no more, having gone as mysteriously as they had come.

These visitors were always foreigners, now of one nationality, now of another: and were always closeted privately with Platzoff for several hours. In appearance some of them were strangely shabby and unkempt, in a wild, un-English sort of fashion, while others among them seemed like men to whom the good things of this world were no strangers. But whatever their appearance, they were all treated by Platzoff as honoured guests for whom nothing at his command was too good.

As a matter of course, they were all introduced to Captain Ducie, but none of their names had been heard by him before—indeed, he had a dim suspicion, gathered, he could not have told how, that the names by which they were made known to him were in some cases fictitious ones, and appropriated for that occasion only. But to the Captain that fact mattered nothing. They were people whom he[Pg 196] should never meet after leaving Bon Repos, or if he did chance to meet them, whom he should never recognise.

One other noticeable feature there was about these birds of passage. They were all men of considerable intelligence—men who could talk tersely and well on almost any topic that might chance to come uppermost at table, or during the after-dinner smoke. Literature, art, science, travel—on any or all of these subjects they had opinions to offer; but one subject there was that seemed tabooed among them as by common consent: that subject was politics. Captain Ducie saw and recognised the fact, but as he himself was a man who cared nothing for politics of any kind, and would have voted them a bore in general conversation, he was by no means disposed to resent their extrusion from the table talk at Bon Repos.

As to whom and what these strangers might be, no direct information was vouchsafed by the Russian. Captain Ducie was left in a great measure to draw his own conclusions. A certain conversation which he had one day with his host seemed to throw some light on the matter. Ducie had been asking Platzoff whether he did not sometimes regret having secluded himself so entirely from the world; whether he did not long sometimes to be in the great centres of humanity, in London or Paris, where alone life's full flavour can be tasted.

"Whenever Bon Repos becomes Mal Repos," answered Platzoff—"whenever a longing such as you speak of comes over me—and it does come sometimes—then I flee away for a few weeks, to London oftener than anywhere else—certainly not to Paris: that to me is forbidden ground. By-and-by I come back to my nest among the hills, vowing there is no place like it in the world's wide round. But even when I am here, I am not so shut out from the world and its great interests as you seem to imagine. I see History enacting itself before my eyes, and I cannot sit by with averted face. I hear the grand chant of Liberty as the beautiful goddess comes nearer and nearer and smites down one Oppressor after another with her red right hand; and I cannot shut my ears. I have been an actor in the great drama of Revolution ever since a lad of twelve. I saw my father borne off in chains to Siberia, and heard my mother with her dying breath curse the tyrant who had sent him there. Since that day Conspiracy has been the very salt of my life. For it I have fought and bled; for it I have suffered hunger, thirst, imprisonment, and dangers unnumbered. Paris, Vienna, St. Petersburg, are all places that I can never hope to see again. For me to set foot in any one of the three would be to run the risk of almost certain detection, and in my case detection would mean hopeless incarceration for the poor remainder of my days. To the world at large I may seem nothing but a simple country gentleman, living a dull life in a spot remote from all stirring interests. But I may tell you, sir (in strictest confidence, mind), that although I stand a little aside from the noise[Pg 197] and heat of the battle, I work for it with heart and brain as busily, and to better purpose, let us hope, than when I was a much younger man. I am still a conspirator, and a conspirator I shall remain till Death taps me on the shoulder and serves me with his last great writ of habeas corpus."

These words recurred to Ducie's memory a day or two later when he found at the dinner-table two foreigners whom he had never seen before.

"Is it possible that these bearded gentlemen are also conspirators?" asked the Captain of himself. "If so, their mode of life must be a very uncomfortable one. It never seems to include the use of a razor, and very sparingly that of comb and brush. I am glad that I have nothing to do with what Platzoff calls The Great Cause."

But Captain Ducie was not a man to trouble himself with the affairs of other people unless his own interests were in some way affected thereby. M. Paul Platzoff might have been mixed up with all the plots in Europe for anything the Captain cared: it was a mere question of taste, and he never interfered with another man's tastes when they did not clash with his own. Besides, in the present case, his attention was claimed by what to him was a matter of far more serious interest. From day to day he was anxiously waiting for news from the London bookseller who was making inquiries on his behalf as to the possibility of obtaining a copy of The Confessions of Parthenio the Mystic. Day passed after day till a fortnight had gone, and still there came no line from the bookseller.

Ducie's impatience could no longer be restrained: he wrote, asking for news. The third day brought a reply. The bookseller had at last heard of a copy. It was in the library of a monastery in the Low Countries. The coffers of the monastery needed replenishing; the abbot was willing to part with the book, but the price of it would be a sum equivalent to fifty guineas of English money. Such was the purport of the letter.

To Captain Ducie, just then, fifty guineas were a matter of serious moment. For a full hour he debated with himself whether or no he should order the book to be bought.

Supposing it duly purchased; supposing that it really proved to be the key by which the secret of the Russian's MS. could be mastered; might not the secret itself prove utterly worthless as far as he, Ducie, was concerned? Might it not be merely a secret bearing on one of those confounded political plots in which Platzoff was implicated—a matter of moment no doubt to the writer, but of no earthly utility to anyone not inoculated with such March-hare madness?

These were the questions that it behoved him to consider. At the end of an hour he decided that the game was worth the candle: he would risk his fifty guineas.

Taking one of Platzoff's horses, he rode without delay to the[Pg 198] nearest telegraph station. His message to the bookseller was as under:

"Buy the book, and send it down to me here by confidential messenger."

The next few day were days of suspense, of burning impatience. The messenger arrived almost sooner than Ducie expected, bringing the book with him. Ducie sighed as he signed the cheque for fifty guineas, with ten pounds for expenses. That shabby calf-bound worm-eaten volume seemed such a poor exchange for the precious slip of paper that had just left his fingers. But what was done could not be undone, so he locked the book away carefully in his desk and locked up his impatience with it till nightfall.

He could not get away from Platzoff till close upon midnight. When he got to his own room he bolted the door, and drew the curtains across the windows, although he knew that it was impossible for anyone to spy on him from without. Then he opened his desk, spread out the MS. before him, and took up the volume. A calf-bound volume, with red edges, and numbering five hundred pages. It was in English, and the title-page stated it to be "The Confessions of Parthenio the Mystic: A Romance. Translated from the Latin. With Annotations, and a Key to Sundrie Dark Meanings. Imprinted at Amsterdam in the Year of Grace 1698." It was in excellent condition.

Captain Ducie's eagerness to test his prize would not allow of more than a very cursory inspection of the general contents of the volume. So far as he could make out, it seemed to be a political satire veiled under the transparent garb of an Eastern story. Parthenio was represented as a holy man—a Spiritualist or Mystic—who had lived for many years in a cave in one of the Arabian deserts. Commanded at length by what he calls the "inner voice," he sets out on his travels to visit sundry courts and kingdoms of the East. He returns after five years, and writes, for the benefit of his disciples, an account of the chief things he has seen and learned while on his travels. The courts of England, France and Spain, under fictitious names, are the chief marks for his ponderous satire, and some of the greatest men in the three kingdoms are lashed with his most scurrilous abuse. Under any circumstances the book was not one that Captain Ducie would have cared to wade through, and in the present case, after dipping into a page here and there, and finding that it contained nothing likely to interest him, he proceeded at once to the more serious business of the evening.

The clocks of Bon Repos were striking midnight as Captain Ducie proceeded to test the value of the first group of figures on the MS., according to the formula laid down for him by his friend Bexell.

The first group of figures was 253.12/4. Turning to page two hundred and fifty-three of the Confessions, and counting from the top of that page, he found that the fourth word of the twelfth line gave him you.[Pg 199] The second clump of figures was 59.25/1. The first word of the twenty-fifth line of page fifty-nine gave him will. The third clump of figures gave him have, and the fourth gathered. These four words, ranged in order, read: You will have gathered. Such a sequence of words could not arise from mere accident. When he had got thus far Ducie knew that Platzoff's secret would soon be a secret no longer, that in a very little while the heart of the mystery would be laid bare.

Encouraged by his success, Ducie went to work with renewed vigour, and before the clock struck one he had completed the first sentence of the MS., which ran as under:—

You will have gathered from the foregoing note, my dear Carlo, that I have something of importance to relate to you—something that I am desirous of keeping a secret from everyone but yourself.

As his friend Bexell surmised, Ducie found that the groups of figures distinguished from the rest by two horizontal lines, one above and one below, as thus 58.7 14.29 368.1 209.18 43.11, were the valeurs of some proper name or other word for which there was no equivalent in the book. Such words had to be spelt out letter by letter in the same way that complete words were picked out in other cases. Thus the marked figures as above, when taken letter by letter, made up the word Carlo—a name to which there was nothing similar in the Confessions.

It had been broad daylight for two hours before Captain Ducie grew tired of his task and went to bed. He went on with it next night, and every night till it was finished. It was a task that deepened in interest as he proceeded with it. It grew upon him to such a degree that when near the close he feigned illness, and kept his room for a whole day, so that he might the sooner get it done.

If Captain Ducie had ever amused himself with trying to imagine the nature of the secret which he had now succeeded in unravelling, the reality must have been very different from his expectations. One gigantic thought, whose coming made him breathless for a moment, took possession of him, as a demon might have done, almost before he had finished his task, dwarfing all other thoughts by its magnitude. It was a thought that found relief in six words only:

"It must and shall be mine!"

"You will have gathered from the foregoing note, my dear Carlo, that I have something of importance to relate to you; something[Pg 200] that I am desirous of keeping a secret from everyone but yourself. From the same source you will have learned where to find the key by which alone the lock of my secret can be opened.

"I was induced by two reasons to make use of The Confessions of Parthenio the Mystic as the basis of my cryptographic communication. In the first place, each of us has in his possession a copy of the same edition of that rare book, viz., the Amsterdam edition of 1698. In the second place, there are not more than half-a-dozen copies of the same work in England; so that if this document were by mischance to fall into the hands of some person other than him for whom it is intended, such person, even if sufficiently acute to guess at the means by which alone the cryptogram can be read, would still find it a matter of some difficulty to obtain possession of the requisite key.

"I address these lines to you, my dear Lampini, not because you and I have been friends from youth, not because we have shared many dangers and hardship together, not because we have both kept the same great object in view throughout life; in fine, I do not address them to you as a private individual, but in your official capacity as Secretary of the Secret Society of San Marco.

"You know how deeply I have had the objects of the Society at heart ever since, twenty-five years ago, I was deemed worthy of being made one of the initiated. You know how earnestly I have striven to forward its views both in England and abroad; that through my connection with it I am suspect at nearly every capital on the Continent—that I could not enter some of them except at the risk of my life; that health, time, money—all have been ungrudgingly given for the furtherance of the same great end.

"Heaven knows I am not penning these lines in any self-gratulatory frame of mind—I who write from this happy haven among the hills. Self-gratulation would ill-become such as me. Where I have given gold, others have given their blood. Where I have given time and labour, others have undergone long and cruel imprisonments, have been separated from all they loved on earth, and have seen the best years of their life fade hopelessly out between the four walls of a living tomb. What are my petty sacrifices to such as these?

"But not to everyone is granted the happiness of cementing a great cause with his heart's blood. We must each work in the appointed way—some of us in the full light of day; others in obscure corners, at work that can never be seen, putting in the stones of the foundation painfully one by one, but never destined to share in the glory of building the roof of the edifice.

"Sometimes, in your letters to me, especially when those letters contained any disheartening news, I have detected a tone of despondency, a latent doubt as to whether the cause to which both of us are so firmly bound was really progressing; whether it was[Pg 201] not fighting against hope to continue the battle any longer; whether it would not be wiser to retreat to the few caves and fastnesses that were left us, and leaving Liberty still languishing in chains, and Tyranny still rampant in the high places of the world, to wage no longer a useless war against the irresistible Fates. Happily, with you such moods were of the rarest: you would have been more than mortal had not your soul at times sat in sackcloth and ashes.

"Such seasons of doubt and gloom have come to me also; but I know that in our secret hearts we both of us have felt that there was a self-sustaining power, a latent vitality in our cause that nothing could crush out utterly; that the more it was trampled on the more dangerous it would become, and the faster it would spread. Certain great events that have happened during the last twelve months have done more towards the propagation of the ideas we have so much at heart than in our wildest dreams we dare have hoped only three short years ago. Gravely considering these things, it seems to me that the time cannot be far distant when the contingent plan of operations as agreed upon by the Central Committee two years ago, to which I gave in my adhesion on the occasion of your last visit to Bon Repos, will have to replace the scheme at present in operation, and will become the great lever in carrying out the Society's policy in time to come.

"When the time shall be ripe, but one difficulty will stand in the way of carrying out the proposed contingent plan. That difficulty will arise from the fact that the Society's present expenses will then be trebled or quadrupled, and that a vast accession to the funds at command of the Committee for the time being will thus be imperatively necessitated. As a step, as a something towards obviating whatever difficulty may arise from lack of funds, I have devised to you, as Secretary of the Society, the whole of my personal estate, amounting in the aggregate to close upon fifteen thousand pounds. This property will not accrue to you till my decease; but that event will happen no very long time hence. My will, duly signed and witnessed, will be found in the hands of my lawyer.

"But it was not merely to advise you of this bequest that I have sought such a roundabout mode of communication. I have a greater and a much more important bequest to make to the Society, through you, its accredited agent. I have in my possession a green Diamond, the estimated value of which is a hundred and fifty thousand pounds. This precious gem I shall leave to you, by you to be sold after my death, the proceeds of the sale to be added to the other funded property of the Society of San Marco.

"The Diamond in question became mine during my travels in India many years ago. I believe my estimate of its value to be a correct one. Except my confidential servant, Cleon (whom you will remember), no one is aware that I have in my possession a stone of such immense value. I have never trusted it out of my own keep[Pg 202]ing, but have always retained it by me, in a safe place, where I could lay my hands upon it at a moment's notice. But not even to Cleon have I entrusted the secret of the hiding-place, incorruptibly faithful as I believe him to be. It is a secret locked in my own bosom alone.

"You will now understand why I have resorted to cryptography in bringing these facts under your notice. It is intended that these lines shall not be read by you till after my decease. Had I adopted the ordinary mode of communicating with you, it seemed to me not impossible that some other eye than the one for which it was intended might peruse this statement before it reached you, and that through some foul play or underhand deed the Diamond might never come into your possession.

"It only remains for me now to point out where and by what means the Diamond may be found. It is hidden away in—"

Here the MS., never completed, ended abruptly.

(To be continued.)

E. Nesbit.

When the Akropolis at Athens bore its beautiful burden entire and perfect, one miniature temple stood dedicated to wingless Victory, in token that the city which had defied and driven back the barbarian should never know defeat.

But only a few decades had passed away when that temple stood as a mute and piteous witness that Athens had been laid low in the dust, and that Victory, though she could never weave a garland for Hellenes who had conquered Hellenes, was no longer a living power upon her chosen citadel. By the eighteenth century the shrine had altogether disappeared: the site only could be traced, and four slabs from its frieze were discovered close at hand, built into the walls of a Turkish powder magazine; but not another fragment could be found.

The descriptions of Pausanias and of one or two later travellers were all that remained to tell us of the whole; of its details we might form some faint conception from those frieze marbles, rescued by Lord Elgin and now in the British museum.

But we are not left to restore the temple of wingless Victory in our imagination merely, aided by description and by fragment. It stands to-day almost complete except for its shattered sculptures, placed upon its original site, and looking, among the ruins of the grander buildings around it, like a beautiful child who gazes for the first time on sorrow which it feels but cannot share. The blocks of marble taken from its walls and columns had been embedded in a mass of masonry, and when Greece was once more free, and all traces of Turkish occupation were being cleared from the Akropolis, these were carefully put together with the result that we have described.

Like this in part, but unhappily only in part, is the story of the poems of Sappho. She wrote, as the architect planned, for all time. We have one brief fragment, proud, but pathetic in its pride, that tells us she knew she was meant not altogether to die:

"I say that there will be remembrance of us hereafter,"

and again with lofty scorn she addresses some other woman:

"But thou shalt lie dead, nor shall there ever be remembrance of thee then or in the time to come, for thou hast no share in the roses of Pieria; but thou shalt wander unseen even in the halls of Hades, flitting forth amid the shades of the dead."