This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Emerson's Wife and Other Western Stories

Emerson's Wife -- Colonel Kate's Protégée -- The Kid of Apache Teju -- A Blaze on Pard Huff -- How Colonel Kate Won Her Spurs -- Hollyhocks -- The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of Johnson Sides -- A Piece of Wreckage -- The Story of a Chinee Kid -- Out of Sympathy -- An Old Roman of Mariposa -- Out of the Mouth of Babes -- Posey -- A Case of the Inner Imperative

Author: Florence Finch Kelly

Release Date: May 4, 2006 [eBook #18309]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EMERSON'S WIFE AND OTHER WESTERN STORIES***

Nick Ellhorn awoke and looked around the room with curiosity and interest, but without surprise. He had no recollection of having entered it the night before, and he was lying across the bed fully clothed. But he had long ago ceased to feel surprise over a matter of that sort. His next movement was to reach for his revolver, and he gave a grunt of satisfaction on finding that it hung, as usual, from his cartridge belt. He was aware of a deep, insistent thirst, and as he sat up on the edge of the bed he announced aloud, in a tone of conviction, "I sure need a cocktail!"

Glancing out of the window, he saw a little plaza, fresh in the morning sunlight with its greening grass and budding trees, and beyond it the pink walls and portalled front of a long adobe building. He nodded approvingly.

"I reckon I pulled my freight from Albuquerque all right. And I had a good load too," he reflected with a chuckle. "And I reckon I sure bunched myself all right into Santa Fe; for if this ain't the Plaza Hotel, I 'm drunker 'n a feller has any right to be who 's been total abstainin' ever since last night. But I 've sure got to have a cocktail now, if it busts a gallus!"

He stared wistfully at the door; but drunken lethargy was still upon him, and his disinclination to move was stronger than his thirst. His eyes, roving along the wall, fell upon the electric call button. Stretching a sinewy arm to its full length he made dumb show of pressing it, as he said, "One push, one cocktail; two pushes, two cocktails!" Then he shook his head despairingly. "Too far, can't reach it," he muttered. But his face brightened as his hand accidentally touched his revolver. Out it flashed, and there was no tremor in the long brown hand that held it in position. Bang! Bang! Bang! went the gun, three shots in quick succession, and then three more. "Six pushes, six cocktails!" he announced, triumphantly.

The button had been driven into the wall, and several holes hovered close upon its wreck. A clatter of hurrying feet on the stairway and the din of excited voices told him that his summons had at least attracted attention. "Push button's a sure handy thing!" he exclaimed aloud as he fell back on the bed, laughing drunkenly.

The footsteps halted outside and the voices sunk to whispers. Presently Ellhorn, gazing expectantly at the door, saw a pair of apprehensive eyes peering through the transom. At sight of the face he waved his hand, which still grasped the gun, and called out, "Say, you, I want six cocktails!" The face quickly dodged downward and the feet and the whispering voices moved farther away. Then came the sound of a rapid stride down the hall and a deep voice bellowed, "Nick, let me in!"

Nick called out "Tommy Tuttle!" and in walked a big bulk of a man, six feet and more tall, with shoulders broad and burly and legs like tree trunks. Ellhorn turned toward him a beaming face and broke into a string of oaths. But his profanity was cordial and joyous. It bloomed with glad welcome and was fragrant with good fellowship and brotherly love.

"Nick, you 're drunk," said Tuttle reprovingly.

"You 're away off, Tom! I was yesterday, but I 've been teetotallin' ever since I came into this room last night, and the whole Arizona desert ain't in it with my throat this mornin'! I want six cocktails!"

"No, you don't," the other interrupted decisively. "You-all can have some coffee," and he stepped back to the door and gave the order.

Ellhorn sat up and looked with indignant surprise at his friend. "Tom Tuttle—" he began.

"Shut up!" Tuttle interrupted. "Come and soak your head."

Ellhorn submitted to the head-soaking without protest, but drank his coffee with grumblings that it was not coffee, but cocktails, that he wanted.

"Nick, ain't you-all ashamed of yourself?" Tuttle asked severely. But it was anxiety rather than reproof that was evident in his large, round face and blue eyes. His fair skin was tanned and burned to a bright red, and against its blazing color glowed softly a short, tawny mustache.

"No, Tommy, not yet," Nick replied cheerfully. "It's too soon. It's likely I will be to-morrow, or mebbe even this afternoon. But not now. You-all ought to be more reasonable."

"To think you 'd pile in here like this, when I 'm in a hole and need you bad," Tuttle went on in a grieved tone.

The fogs had begun to clear out of Ellhorn's head, and he looked up with quick concern. "What's up, Tom?"

"The Dysert gang 's broke loose again, and Marshal Black 's in San Francisco, and Sheriff Williamson 's gone to Chicago. I 've got to ride herd on 'em all by myself."

"What have they done?"

"Old man Paxton was found dead by his front gate yesterday morning. He 'd been killed by a knife-thrower, and a boss one at that—cut right across his jugular. I went straight for Felipe Vigil, and last night I got a clue from him, and he promised to tell me more to-day. But this morning he was found dead under the long bridge with his tongue cut out. That's enough for 'em; not another Greaser will dare open his mouth now. I wired you yesterday at Plumas to come as quick as you could."

"Then what you gruntin' about, Tom? I left Plumas before your wire got there, and how could I be any quicker 'n that?"

"I wish Emerson was here. I 'd like to have his judgment about this business. Emerson 's always got sure good judgment."

"Send for him, then," was Nick's prompt rejoinder.

Tuttle looked at him with surprise and disapproval. "Nick, are you drunker than you look? You-all know he 's just got back from his wedding trip."

"But he 's back, all right, ain't he! Neither one of us has ever got into a hole yet that Emerson did n't come a-runnin', and fixed for whatever might happen. And he's never needed us that we did n't get there as quick as we could. You-all don't reckon, Tom, that Emerson Mead's liver 's turned white just because he 's got a wife!"

Tom Tuttle fidgeted his big bulk and cleared his throat. Words did not come so easily to him as deeds, but Ellhorn's way of putting it made explanation necessary. "I don't mean it that way, Tom. Once, last year, down in Plumas, when Emerson would n't let us shoot into that crowd that wanted to hang him, I wondered for just a second if he was afraid, and it made me plumb sick. But I saw right away that it was just Emerson's judgment that there ought n't to be any shootin' right then, and he was plumb right about it. No, Tom, I sure reckon there ain't a drop of blood in Emerson's veins that would n't be ready for a fight any minute, if 't was his judgment that there ought to be a fight, even if he has got married. But we-all must remember that he 's got a wife now, and can't cut out from his family and go rushin' round the country like a steer on the prod every time you get drunk and raise hell, or every time I need help. We 'll have to pull together after this, Tom, and leave Emerson out. It would be too much like stackin' the cards against Mrs. Emerson if we didn't."

As Tuttle ended he saw a gleam in the other's eyes that caused him to add with emphasis, "And I 'm not goin' to call him up here, and don't you do it, either!"

Nick got up, shook himself, and winked at the hole in the wall where had been the electric button. He was a handsome man, as tall as Tuttle, but more slenderly built, with clean-cut features, dancing black eyes, and a black mustache that swept in an upward curve over his tanned cheek. His friend scrutinized him anxiously as he slid cartridges into the empty chambers of his revolver.

"Sure you 're sober, Nick?"

Ellhorn laughed. "How the devil can I tell? I can walk straight and see straight and shoot straight; and if that ain't sober enough to tackle any four-spot Greaser, I might just as well get drunk again!"

"Well, I reckon you 're sober enough to jump into this job with me now; and if you stay sober, it's all right. But if I catch you drinkin' another drop till we get through with this business, I 'll run you back into this room and sit on your belly till you 're ready to holler quits!"

It was a dangerous solidarity of crime and mutual protection against which the two deputy marshals started out alone. The Dysert gang had been organized originally as a secret society to further the political ambitions of men who were not overscrupulous as to instruments or methods. But gradually it had drifted into a means of wreaking private revenge and compelling money tribute. Those of its early members who were of the law abiding sort had left it long before, and its membership had dwindled to a handful of Mexicans of the recklessly criminal sort. They were credited, in the general belief, with thefts, assaults, and murders; but so closely had they held together, so potent was their influence with men in public station, and so general was the fear of the bloody revenges they did not hesitate to take, that not one of them had yet been convicted of crime.

Faustin Dysert, who had organized the society and was still its head, combined in himself the worst tendencies of both Mexicans and Americans, his mother having been of one race and his father of the other, and both of the sort that reflect no credit upon their offspring. But he owned the house in which he lived and two or three other adobes which he rented, and was therefore lifted above the necessity of labor and held in much regard by his fellow Mexicans. The combination of that influence and the favor of the political boss of his party, to whom he had been of use, had made him chief of police of Santa Fé and had kept him in that office for several years. And he had been careful to recruit his force from the membership of his society.

Tuttle knew that he could not count on any open help or sympathy from the public, for no one would dare to invite thus frankly the disfavor of the gang. And he knew, too, that he could expect to get no more information from leaky members of the society or their friends, since that swift punishment had been meted out to the wagging tongue of Felipe Vigil. He was well aware also that his chief, the United States Marshal, had not been zealous in the pursuit of Dysert's criminals, and that Black's friend, Congressman Dellmey Baxter, was known to have under his protection several members of the society. Therefore, if he bungled the job, he was likely to lose his official head; and if he were not swift and sure in his movements against the gang, his physical head would not be worth the lead that would undoubtedly come crashing into it from behind, before the end of the week.

"The thing for us to do, Tommy," advised Ellhorn, "is to take in all the gang we can get hold of. We 'll herd 'em all into jail first, and get the evidence afterwards. There 'll be some show to get it then, and there ain't now. We 'll load up with warrants, and arrest every kiote that's thought to be a member of the gang; and we 'll start in with Faustin Dysert himself!"

Tuttle looked perplexed. He had in his veins a strain of German blood, which showed in his frank, sincere, blonde countenance and in his direct and unimaginative habit of mind. But Ellhorn supplemented his solidity and straightforwardness with an audacity of initiative and a disregard of consequences that told of Celtic ancestry as plainly as did the suggestion of a brogue that in moments of excitement touched his soft Southern speech.

"Marshal Black would be dead agin goin' at it that way," said Tuttle doubtfully.

"Of course he would! But he ain't here, and we 'll run this round-up to suit ourselves; and if we don't bunch more bad steers than was ever got together in this town before, I 'll pull my freight for hell without takin' another drink!"

"Mebbe you 're right," said Tuttle slowly, "and I think likely that would be Emerson's judgment too. If he hadn't got married we 'd be all right. Us three could go up agin the whole lot of 'em and win out in three shakes!"

"Then let's send for him, and see if he 'll come!"

But Tuttle shook his head. "No," he said positively, "that would n't be a square deal for Mrs. Emerson, and we won't do it. We 'll stack up alone against this business, Nick. We 'll put on all the guns we 've got and keep together. We might get Willoughby Simmons—he 's deputy sheriff now; but he 's got no judgment, and he 's likely to get rattled and shoot wild if things get excitin'. We 'll get the warrants and start out right away, for we 've got to keep the thing quiet and nab 'em before they find out we 're on the warpath. You-all remember you 're sure goin' to keep sober!"

"Well," said Nick with a laugh, "I 'll be sober enough to stack up with any measly kiote that's pirootin' around this town!"

Tuttle went for the warrants, and Ellhorn said he would get some breakfast. But first he waited until his friend was out of sight and then paid a visit to the bar-room. Next he went to the telegraph office. The message that he sent was addressed to Emerson Mead, Las Plumas, New Mexico, and it read:

"Tommy and me are up against the Dysert gang alone, and I 'm drunk. Nick."

He came out of the telegraph office smiling joyously and humming under his breath the air of "Bonnie Dundee." "I did n't ask him to come," he said to himself, "and if he wants to now, that's his affair. Well, I reckon he ain't any more likely to have daylight let through him now than he was before he got married; and nobody's gun has made holes in him yet!"

It was early afternoon when the two friends started out on their round-up of bad men. To attract as little notice as possible they took a closed hack and drove rapidly toward the Mexican quarter. Nick's manner showed such recklessness and high spirits that Tuttle regarded him with anxiety and began to wonder if it would not be wiser to carry out his threat of the morning before attempting anything else. But he caught sight of two Mexicans coming toward them, one handsome and well built and the other slouching and ill-favored.

"There come two of 'em now! Liberate Herrera and Pablo Gonzalez!" he exclaimed, with sudden concentration of interest and attention. "Liberate is a boss knife-thrower, and I think likely he 's the one that did the business for old man Paxton. Look out for 'im, Nick!"

The carriage came abreast of the two men and Tuttle jumped out, with Ellhorn close behind him. But quick as they were, Herrera, the handsome one of the two, understood what was happening and leaped to one side, a long knife flashing from his sleeve, before Tuttle's hand could descend upon him. The other was slower and Ellhorn had him by the arm before he could thrust his hand into his pocket for his revolver. Herrera's knife slid into position against his wrist and Tuttle's revolver clicked. The Mexican looked dauntlessly into its black muzzle, but saw that his companion was submitting, and that both were covered by the guns of the officers.

"It's all right, Señor Tuttle," he said coolly. "You 've got the best of me. I give up."

They drove back to the adobe jail; and while Tuttle was turning his prisoners into the custody of Willoughby Simmons, the deputy sheriff, Ellhorn slipped out, crossed the street, and went into a saloon. The men already there had watched the arrival of the hack and the two prisoners at the jail, and two of them, when they saw Nick coming, hurried into the back room, leaving the door open.

"What's up, Nick?" the proprietor asked as he poured the whiskey Ellhorn had ordered.

"Tommy and me," answered Nick jauntily, pushing his glass across the bar to be filled a second time. "We 're on top now, and I sure reckon we 're goin' to stay there!"

"After the Dysert gang?"

"You bet! Hot and heavy! We'll have 'em all bunched in the jail by night!"

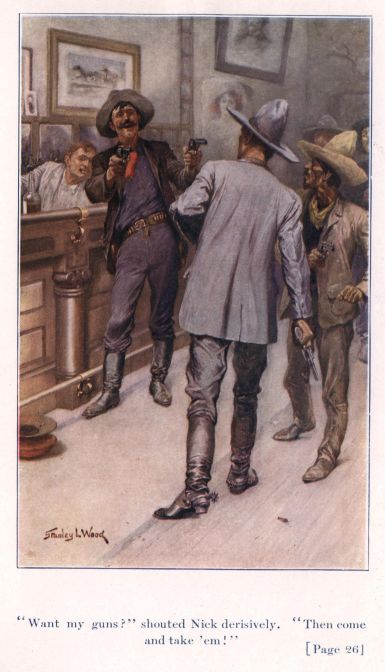

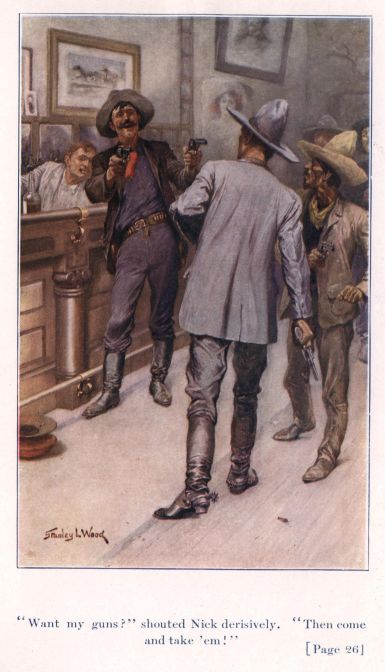

Ellhorn stood with his back toward the middle door; and the two men in the rear room cautiously made their way into the front again, revolvers in their hands. Nick turned and found himself facing Faustin Dysert and Hippolito Chavez, a policeman and member of Dysert's society. His two revolvers flashed out, the triggers clicked, and he stood waiting for the next move of the others, for he saw at once that they did not intend to shoot at that moment.

"You 'll have to give me your guns, Nick," said Dysert. "You 're drunk and disorderly, and I 'm going to arrest you."

"Want my guns?" shouted Nick derisively. "Then come and take 'em!"

"I 'm going to take them, and I 'll give you two minutes in which to decide whether or not you 'll give them up peaceably."

"You will, will you! Let me tell you, it's yourself that's goin' to be taken, dead or alive, and not for any common 'drunk and disorderly,' either! You-all are goin' to swing, you are! Whoo-oo-ee-ee!"

Across the street, Tuttle had come out of the jail and was looking for his friend. Ellhorn's peculiar yell came bellowing from the saloon, and he knew that trouble of some sort was brewing. Dysert and Chavez saw him leaping across the street, and rushed into the back room and slammed the door as he entered at the front. With a glance Tuttle took in the group of men with tense, excited faces, gathered at one side of the room, Ellhorn, with a revolver in each hand, at the other, and the saloon-keeper emerging from underneath the bar.

"Nick, you 're drinkin' again! Put up your guns!" Tom exclaimed angrily.

"After 'em, Tommy! They went in there! Whoo-oo-ee-ee!" yelled Nick, rushing toward the middle door. It gave before his weight and he dashed in. Tuttle followed, not knowing what was happening, yet sure that his friend was daring some danger. But the room was empty. Through the back door Dysert and his companion had gained a corral, into which opened several other houses, and in some one of these had disappeared and found concealment.

"Huh!" grunted Nick. "Tom, if you'd only had sense enough to stay away a minute longer I 'd have got both of 'em myself!"

They started forth on another raid, but the members of the Dysert gang seemed to have vanished from the face of the earth. Neither in the streets, the plaza, their homes, nor their usual haunts could the officers of the law find one of those for whom they had warrants.

"It's what I was afraid of," said Tuttle. "The hint got out too quick for us, and now they 're all hiding."

"They've holed up somewhere, all in a bunch, and we 've got to smoke 'em out. Whoo-oo-ee-ee!"

The several whiskies with which Nick had succeeded in eluding his friend's vigilance were beginning to have manifest effect, and Tuttle decided that, whatever became of the Dysert gang, there was only one thing to do with Nick Ellhorn, and that would have to be done at once. He drove back to the Plaza Hotel, took Nick to his room, locked the door, and put the key in his pocket.

"Now, Nick, you-all don't get out of here till you 're plumb sober—sober enough to be sorry!"

Nick protested, but Tuttle threw him down on the bed and then deliberately sat down on his chest. Ellhorn swore valiantly and threatened many and dire revenges. But Tom sat still, in unheeding silence, and after a little Nick shut his mouth with a snap and gazed sullenly at the ceiling. He labored for breath for a while, and at last broke the silence by asking impatiently: "Say, Tom, how long you goin' to make an easy chair of me?"

"You know, without askin'!"

Nick relapsed into silence again until his face grew purple and his breath came in gasps. "Tom," he began, and there was no backbone left in his voice, "what do you-all want me to promise?"

"Not to drink another drop of whiskey, beer, wine, brandy, or anything intoxicatin', till we get the Dysert gang corralled—or they get us."

"All right, Tommy. I promise."

Tattle got up and looked at his friend with an expression of mingled apology and triumph on his big, red face. "I 'm sorry I had to do it. Nick. You-all know that. But I had to, and you know that, too. We can't do another thing now till to-morrow, and you 're sober again. I don't see," he went on grumblingly, "as long as they were goin' to kill old man Paxton anyway, why they did n't do it before Emerson got married!"

Nick had been soaking his head in the wash-bowl and he wheeled around with the water streaming over his face. "Tom, I sure reckon Emerson would come if you 'd send for him!"

"Mebbe he would, Nick, but I ain't goin' to do it. For he sure had n't ought to go and get himself killed now, just on our account. But if he was here," Tommy went on wistfully, "we 'd wipe up the ground with that Dysert gang too quick!"

Nick rolled over on the bed, sleep heavy on his eyelids. "Well, I gave Emerson the chance this mornin' to let us know whether he 's goin' to keep on bein' one of us, or whether he 's goin' to bunch alone with Mrs. Emerson after this!"

Tuttle gazed in open-mouthed and wide-eyed astonishment. "What—what—do you mean, Nick? You did n't wire him to come?"

"No, I did n't! I told him you and me was up against the Dysert gang—" Nick's voice trailed off into a sleepy murmur—"alone, and I—was drunk—and likely to get—disorderly."

"You measly, ornery—" Tuttle began. But he saw that Ellhorn was already asleep and he would not abuse his friend unless Nick could hear what he said. So he shut his mouth and considered the situation. He knew well enough that in the days before Emerson's marriage any such message would have brought Mead to their aid as fast as steam could carry him. But now, if he did not come—well, what Nick had said was true, and they would know that the end of the old close friendship had come. But, for the young wife's sake, if he should come, he and Nick must not let him do anything foolhardy and they must try to keep him out of danger.

Tuttle waited up for the midnight train, on which, if Mead heeded Nick's telegram, he would be likely to arrive. In the meantime, he did some spying out of the land and learned that Dysert and some of his followers had hidden themselves, with arms, ammunition, and provisions, in an empty adobe house belonging to the head of the band. The deputy marshal knew this meant that the criminals would resist to the last, and that any attempt to take them would be as perilous an adventure as he and his friends had ever faced. If Emerson came and anything happened to him—and it was very unlikely, if they carried the thing through, that any one of them would come out of it without at least serious injury—then he and Ellhorn would feel that they had been the cause of the young wife's bereavement. And yet, with Mead's help, they might succeed. And success in this enterprise would be the biggest, the crowning achievement in all their experience as officers of the law.

As midnight approached, Tuttle scarcely knew whether he more hoped or dreaded that Mead would come. He had faced the muzzle of loaded guns with less trepidation and anxiety than he felt as he stepped out on the sidewalk when he heard the rattle of the omnibus. A tall figure, big and broad-shouldered, swung down from the vehicle.

"Emerson—Emerson—" Tuttle stammered, his voice shaking and dying in his throat into something very like a sob. Then he gripped Mead's hand and said casually, "How 's Mrs. Emerson?"

Mead replied merely, "She's well"; but Tom caught an unwonted intonation of tenderness in his voice and saw his face soften and glow for an instant before he went on anxiously, "What's up?—and where 's Nick?"

Tuttle wavered a little the next morning in his purpose of attacking the Dysert retreat. He took Ellhorn aside and asked his opinion about letting the matter rest until the return of Marshal Black and Sheriff Williamson.

Nick was quite sober again and looked back over his misdeeds of the day before with a jaunty smile and a penitent shake of the head. "Sure, Tom," he said, and the Irish roll in his voice showed that his contrition was sincere enough to move him deeply, "sure and I was a measly, beastly, ornery kiote to go back on you like that, and you 'd have served me right if you 'd set on me twice as long as you did!"

But against Tuttle's suggestion of postponing the conflict he presented a surprised and combative front. "What you-all thinkin' of, Tom? Why, we 've got 'em holed up now, and all that's to do is to smoke 'em out!"

"It's Emerson I 'm thinkin' of—and Mrs. Emerson. He—he wrote her a letter this mornin', and put it in his pocket, and asked me if anything happened to him to see that she got it. Nick, I—I don't like to think about that! If we put this thing off, he 'll go home, and then we-all can fight it through without him, mebbe. Nick, you was a sure kiote to send for him yesterday."

"Yes, I sure was," said Nick with sorrowful conviction. Then he added, with an air of cheerful finality, "Well, I would n't 'a' done it if I had n't been drunk! But you 're right, Tommy. It ain't the square deal to Mrs. Emerson for us to take him into this business. It 'll be a fight to a finish, for one side or the other, and it's just as likely to be us as them."

At that moment Mead came up, saying briskly, "Well, boys, had n't we better be starting out?"

Like his two friends, Emerson Mead was Texan born and bred; but a New England strain in his blood, with its potent strength and sanity, had given him such poise and force of character as had made him the leader of the three through their long and intimate friendship and strenuous life.

"I 've just been sayin' to Nick," Tom replied, his eyes evading those of his friend, "that mebbe we 'd better let this thing slide till Black and Williamson get back."

"Well, Tom, this is your shindy, and whatever you say goes. But I sure think that if you really want to get this Dysert gang, the thing to do is to trot in and get 'em, right now. You know yourself that Black ain't any too warm about it, and Williamson is so under Dell Baxter's thumb that he 's more likely to trip you up, if he can, than he is to help. You-all won't get another chance as good as this!"

Ellhorn's martial ardor, and his buoyant belief that Mead's marriage had in no wise lessened his immunity from bullets, obscured for the moment his anxiety about Mrs. Mead. He slapped his thigh, exclaiming, "Them's my sentiments, boys! Come on! Let's pull our freight!"

Tuttle's manner still showed some reluctance, but he said no more, and the three Texans, each of them six feet three or more in his stockings, broad-shouldered, and straight as an arrow, swung into the street.

They took with them Willoughby Simmons, the deputy sheriff for whose judgment Tom had so little esteem. Tuttle sent him to guard the rear of the house, a small, detached adobe, in which Dysert and an unknown number of his followers had fortified themselves. Some twenty feet in front and toward one corner of the house grew a large old apple tree, its leaves and pink-nosed buds just beginning to make themselves manifest, and underneath it were some piles of wood. It was the only position that offered cover. Tuttle asked Mead to station himself there, where he could command one end of the house, a view toward the rear, and the whole front. Ellhorn he placed similarly at the other front corner. His own position he took midway between the two, facing the door and two small windows that blinked beneath the narrow portal.

Mead saw that he was the only one for whom protection was possible, and exclaimed, "Say, Tom, this ain't fair!"

But Tuttle paid no attention to his protest, and began to call loudly:

"Dysert! Faustin Dysert! We know you 're in there, you and your men, and if you 'll give yourselves up you won't get hurt. But we 're goin' to take you, dead or alive! If there 's anybody in there that don't belong in your gang, send 'em out, and we 'll let 'em go away peaceable!"

There was no reply from the house. Evidently those within meant to play a waiting game until they could get the officers of the law under their hands, or perhaps take them unawares. Tuttle glanced at Mead and saw that he was standing apart from the tree and the piles of wood. Tom thought of the letter in his friend's pocket and remembered the look that had crossed his face at the mention of his wife. Great beads of sweat broke out on Tom's forehead. With his lips set and his eyes on those squinting front windows he walked across to his friend and said in a low tone:

"I reckon, Emerson, we 'd better just stand here and guard the place till they see they 'll starve to death if they don't give up."

Mead turned upon him a look of supreme astonishment. "It's your fight, Tom," he answered coolly, "and if you-all think that's the best way of fightin' it, I 'll stand by and help as long as I 'm needed. But I did n't come up here expectin' to take part in any cold-feet show!"

Tuttle wiped his face vigorously and did not answer. "I think there's only one thing to do," Mead went on, "and that is to rush 'em and make 'em show their hand!"

Tuttle shook his head. "No, no," he exclaimed hurriedly, "that wouldn't do at all, Emerson!"

Mead left him and, keeping the front of the house in the tail of his eye, hurried across the yard to Ellhorn. "Nick," he demanded, "what's the matter with Tommy? Does he want to take these Greasers or not?"

"Well, Emerson," said Nick hesitatingly, "I sure reckon the truth is that he's afraid you 'll get hurt!"

The ruddy tan of Mead's face deepened to purple, and a yellow light blazed in his brown eyes. He strode back to where Tuttle had resumed his post, his fist shot out, and Tom went staggering backward. "So you-all think I 'm a coward, do you?" he shouted. Then, wheeling, with a revolver in each hand, he rushed toward the front door. Nick saw what he purposed to do, and dashed after him with a wild "Whoo-oo-ee!"

Tuttle was left without support. For a moment he was so dazed by Mead's blow that he stared about him bewilderedly. The men inside the house were quick to take advantage of so unexpected a situation. The windows flashed fire and Tom heard the thud of bullets against the ground at his feet. One bit his cheek. With loud and angry oaths he dropped to one knee, rifle in hand, and sent bullets and insults hurtling together through the crashing windows. Springing to his feet he ran a few steps forward, dropped to his knee again, and with bullets pattering all around him emptied the magazine of his rifle.

Mead and Ellhorn were trying to batter down the door, but it was strongly built and had not yielded to their shoulders. Throwing down his empty rifle, Tuttle ran into the portal, thrust Ellhorn to one side as if he had been a boy, and lunged against the door with all his ox-like weight. Mead threw himself against it at the same instant, and it cracked, split, and flew into splinters.

The three big Texans, each with a revolver in either hand, surged through the opening. The Mexicans met them in mid-floor, and the room was full of the whirr of flying bullets, the thud of bullets against the walls, the spat of bullets upon human flesh. The officers rushed forward, their guns blazing streams of fire, and Dysert and his men backed toward the corner. Mead emptied both of his revolvers and, pressing the leader closely, raised one of them to batter him over the head. Dysert threw up his hands, exclaiming, "We give up!" and the battle was over.

On the floor were the bodies of four Mexicans, either dead or badly wounded. Dysert and three of his followers were still alive, although each had been hurt. Tuttle, besides the gash in his cheek, had a bullet in his left arm, and Ellhorn a wound in his thigh. Mead's hat and clothing had been pierced, but his body was untouched.

They sent for physicians to attend to the wounded Mexicans and, having handcuffed their prisoners, hurried them to the jail. As Simmons led the men from the sheriff's office and the three friends were left alone, Mead turned to Tuttle.

"Tom," he said, "I 'm sure sorry I struck you just now. I was so mad I hardly knew what I was doing. You 'd been acting queer, and when I found it was because you thought I was afraid, I just boiled over. I had no business to do it, Tom, and I 'm sorry."

The red of Tom's face went a shade deeper, and he fidgeted uneasily. "No, Emerson, you 're wrong," he protested. "I did n't think you was afraid. You-all ought to know better than that. But—well—the truth is, Emerson, I could n't help thinkin' what hard lines it would be for Mrs. Emerson if anything—should happen to you."

The tears came into Mead's eyes, and he turned away as Tuttle went on: "I told Nick not to send for you, but the darned kiote went and done it without me knowing it!"

"No, I didn't," Nick exclaimed. "I just told him we was in a hole and I was drunk! And, anyway, it's a good thing I did; for now we 've got the Dyserts, and Emerson did n't get a scratch!"

"Boys," said Mead, and his voice was thick in his throat, "you 're the best friends any fellow ever had; but you-all don't know what a brick Marguerite is! She 'd rather die than come between us, I know she would! She would n't have any more use for me if she thought I 'd kept a whole skin by going back on you! It's the truth, boys, and don't you forget it!"

"Colonel Kate," as both the Select and the Unassorted of Santa Fé society were accustomed to speak of Mrs. Harrison Winthrop Coolidge, had long ago proved her right to do whatever she chose, by always accomplishing whatever she attempted. She had done so many startling things, and always with such dashing success, since Governor Coolidge had brought her, a bride, to the old town, that people had become accustomed to her, just as they had grown used to the climate, and expected her deeds of daring as unthinkingly as they did cool breezes in summer, or sunshine in winter. Besides, everybody liked her; for she had both the charm which makes new friends and the tact which holds them loyal.

When, finally, Colonel Kate brought an Indian girl from the pueblo of Acoma and made it known that she intended her protégée to grace the innermost circles of Santa Fé society, it is possible that some of the Select may have shrugged their shoulders a trifle; but, if they did, they were careful to have no witnesses. For Governor Coolidge was the richest, the most influential, and the most prominent American in New Mexico, and his wife could make and unmake social circles as she chose. The Santa Fé Blast, which was the organ of the Governor's party, announced the event as follows:

"Mrs. Governor Coolidge and guests returned yesterday from a trip to Acoma. As always, Mrs. Coolidge was the life of the party and charmed all by her wit and beauty and vivacity.… She even persuaded old Ambrosio, the grizzled civil chief of the pueblo, to entrust to her care his most precious treasure, his lovely and charming daughter, Miss Barbara Koitza. This beautiful and talented young lady, whom Mrs. Coolidge has installed as a friend and guest in her hospitable and interesting home, where she is soon to be introduced to Santa Fé society, is as cultured as she is handsome. She has spent a year in the Indian school at Albuquerque and two years at Carlyle, and is well fitted to adorn the choicest social circles in the land. She will no doubt be warmly welcomed by Santa Fé society and will at once take that position in its midst to which her beauty, grace, and talents entitle her."

If she had known of it, poor little Barbara would have been overwhelmed by this flourish of trumpets. But Colonel Kate did not allow it to fall under her eye. And the girl did not even know that, whatever she was not, she certainly was interesting and picturesque on the day when she first entered her new friend's door.

She wore her Indian costume, and was neat and clean as any white maiden with a heritage of bath-tubs. Spotlessly white were her buckskin moccasins and leggings, which encased a pair of tiny feet and then wound round and round her sturdy legs until they looked as shapeless as telegraph posts. Her scant, red calico skirt met her leggings at the knee; and her red mantle, of Navajo weave, fell back from her head, but wrapped closely her waist and arms, and then dropped long ends down the front of her dress. Her coal-black hair, heavy and shining, was combed smoothly back from her forehead and fastened in a chongo behind. Her brown face was handsomer than that of most Indian maidens, being longer in proportion to its width than is the pueblo type, the cheek bones less prominent, the forehead broader, and the lips fuller and more delicately chiselled. It is possible that, far back in Barbara's ancestry, perhaps even as far back as the times of the Conquistadores, there had been some admixture of the white man's race which, after generations of quiescence, in her had at last made its influence felt again.

As Mrs. Coolidge led the girl into her new home she looked down at her with approving eye and inwardly exclaimed, the conqueror's joy already filling her heart, "She 'll be a success! A tremendous success! The Colonel's wife can do what she pleases now!"

For in the days of which this chronicle tells, Santa Fé was still a military post, and the wife of the commanding officer had been all winter a thorn in the flesh of Mrs. Coolidge. The Colonel had been recently transferred from an Eastern post; and his wife, who had never been West before, had supposed that of course she would at once become the social leader of Santa Fe. Her disappointment was bitter when she found that place already firmly held and learned that she, the wife of a colonel in the army, and just from the East, would have to yield first place to the wife of a mere civilian who had lived in the West for a dozen years. She rebelled and tried to start a clique of her own, and all winter she had made trouble among the Select by getting up affairs which clashed with Colonel Kate's plans, and by introducing innovations of which Colonel Kate did not approve. Mrs. Coolidge had no fears for her social supremacy,—she had reigned too long for the thought of downfall to be possible,—but she was tired of being crossed and annoyed, and she purposed with one audacious blow to humble the Colonel's wife and put an end to her pretensions.

The plan came to her suddenly while she talked with old Ambrosio's daughter in the street at Acoma. She saw that Barbara was discontented and unhappy, and that she longed to return to even so much of the life of the whites as she had found in the Indian schools. Colonel Kate pitied her and determined to help her. She was saying to herself that the girl was certainly intelligent and attractive, when she suddenly realized that this Indian maid was gifted with that indefinable but most potent of feminine attractions—personal charm. And then, like an inspiration, the idea took possession of her mind. She turned impulsively to Barbara:

"Will you go home with me and be my guest for all this spring and summer?"

The joy that beamed in the girl's face told how gladly she would go. But it faded quickly and she shook her head sadly, as she answered:

"I can not. My father would not allow it. He will not even let me go back to school. He says that I am an Indian, and that I must stay in Acoma and be an Indian."

When Mrs. Coolidge saw that look of eager desire leap into Barbara's eyes she determined that the thing should be brought to pass and set herself to the task of overcoming old Ambrosio's determination that his daughter should never again leave Acoma. It was not an easy thing to do, but Colonel Kate finally accomplished it, on condition that Barbara should return whenever he wished her to do so.

During the remaining days of Lent, dressmakers were busy with Barbara's wardrobe; and Mrs. Coolidge carefully schooled her in a hundred little particulars of manner and deportment. And meanwhile the Select of Santa Fé waited with impatience for a first view of the Indian girl. For Colonel Kate was too shrewd a manager to discount the sensation she intended to produce, and so she kept Barbara at home, away from the front doors and windows, and out of sight of curious callers. In the meantime she diplomatically helped on the growing interest and excitement, and lost no opportunity of arousing curiosity about her protégée.

And at last, when Barbara had been three weeks in her home, and no one outside her own household had even seen the girl's face; when the town was full of rumors and chatter and all manner of romantic stories about the Indian girl; when everybody was wondering what she could be like, and why Colonel Kate had taken such a fancy to her, then Mrs. Coolidge gave her a coming-out party which eclipsed everything in Santa Fe's social annals.

All the Select were there, including the Colonel's wife, who had not even thought of trying to have a card party the same night. The doors had been opened wide, also, for the Unassorted. All the most eligible of these had received invitations, and not one had sent regrets. The editor of The Blast, which was the mouthpiece of the Governor's party, and the editor of The Bugle, the organ of the opposition, were both there; and each of them published a glowing account of the occasion, the former because he considered it his duty to "stand in" with whatever concerned the Governor; and the latter because he hoped the Governor's wife would make it possible for him to be transferred from the Unassorted to the Select.

The Blast said: "The Governor's palatial mansion was a dream of Oriental magnificence, and the beautiful and artistic placita, lighted by sparkling eyes of ladies fair and Japanese lanterns, was a vision of fairy land." The Bugle declared: "No, not even in the marble drawing-rooms of Fifth Avenue and adjoining streets, nor in the luxurious mansions of Washington, could be gathered together a more cultured, a more polished, a more interesting, a more recherché assemblage than that which filled the Governor's palatial residence and vied with one another in doing homage to the winsome Indian maiden."

To call the Governor's residence "palatial" was part of the common law of Santa Fé journalism. In actual fact, it was a one-story, flat-roofed, adobe house, enclosing a placita, or little court, and having a portal, or roofed sidewalk, along its front.

When she first went to New Mexico, Mrs. Coolidge enjoyed transports of enthusiasm over the quaintness and picturesqueness of its alien modes of living. So she hunted all over Santa Fé for a house of the requisite age, dilapidation, and eventful history, to transform into her own home. And when at last she found this one, with an authenticated age of two hundred years, and a romance, a crime, or a startling event for almost every year in its history; with rough, irregular walls four feet thick; with tiny, unglazed, iron-barred windows,—then time stopped, it seemed to her, until the deed was recorded in her name.

With much sadness of heart she made sentiment give way to civilization and renovated the interior. Wooden floors, instead of the packed earth, hardened and glazed by the tread of many generations, plastered and papered ceilings and walls and ample windows gave to the inside of the house a modern air which its mistress deeply regretted, but accepted mournfully as a necessary evil. But she did not allow a weed or a blade of grass to be plucked from its roof; and upon the suggestion that the old brown adobe walls should be treated to a coat of gray plaster she frowned as if it had been blasphemy.

Upon the placita, which had been given over to weeds, tin cans, rags, and broken dishes, she lavished loving care and made it the blooming, fragrant heart of her home. In the centre was a locust tree of lusty growth, plumy of foliage and brilliant of color; and underneath the tree a little fountain shot upward a thin stream, which broke into a diamond shower and fell plashing back into a pool whose rim was outlined by a circle of purple-flowered iris. Around this spread a velvet turf, dotted with dandelions and English daisies. An irregular, winding path inclosed the tiny lawn, and all the space between the path and the narrow stone walk that hugged the four sides of the house was rich with roses. La France and American Beauty and Jacqueminot and many others were there in profusion and made the placita a thing of beauty from the time the frosts ended until they came again. A hand rail covered with climbing roses guarded the stone walk on three sides of the court, while the fourth side of the house was screened by a portal over which roses and honeysuckles clambered to the roof. Facing the wide, roofed passage which gave entrance from the street, stood an arch loaded with honeysuckle vines.

Mrs. Coolidge's enthusiasm over New Mexican history, and her admiration for the heroic times of the Conquistadores, had caused her to make the interior of her home almost a museum of antiquities. On the floors Navajo blankets—fifty, a hundred, a hundred and fifty years old, and each one with its own dramatic tale—served as rugs. Silken rebozos, worn by high-hearted cavaliers riding in search of "la gran Quivera" draped her windows. Pueblo pottery, dug from villages that were in ruins when the first white men saw them, filled cabinets and shelves. Saddle skirts of embroidered leather, which had pleased the fancy of some brave capitan leading a handful of men against a rebellious pueblo two centuries ago, made a background for the huge silver spurs of cunning workmanship with which some other daring caballero had urged his horse in search of adventures and of gold. And beside them lay the stone axe with which a courageous señora, a heroine of the Southwest, had cleft the skull of a Navajo chief and saved her townspeople from falling into the hands of the savage enemy. On the walls were old, old paintings of Nuestra Señora de this and that, proud of neck and sad and sweet of face, which had been brought from the City of Mexico on the backs of burros, and adored in little adobe churches by generations of men, women, and children, and pierced by the arrows of angry and revengeful Indians during the pueblo rebellion, or scarred by fires of destruction, from which they had been saved by brave and pious devotees.

Such things as these made a picturesque setting for the Indian maid on the night of her début. It might have been a painful ordeal for her had she known that all these people were there mainly to satisfy their curiosity concerning her. But Mrs. Coolidge had carefully kept from her the knowledge that she was of especial interest and was expected to produce a sensation. So she knew only that she was having a delightful time and that everybody was so kind and cordial and took so much interest in her that she did not have a minute during the whole evening in which to think about herself. Everybody was eager to dance, or talk, or stroll in the placita with her, and all who were not engaged with her were talking enthusiastically in praise of her appearance, her manner, or her conversation.

Colonel Kate moved about, proud and happy in the brilliant success of her hazardous undertaking and serene in the confidence that the Colonel's wife would not again attempt rebellion. She was even more glad and happy for Barbara's sake, for the two had grown very fond of each other and she had begun to wonder if old Ambrosio could not be induced to let her adopt the girl. Already it made her heart ache to think she might have to give up her protégée. She cast a glance at Barbara, who was holding her usual court, a circle of men about her, and thought:

"Nonsense! Old Ambrosio is not so stupid as to refuse his daughter such a chance as I can give her!"

For Colonel Kate, with all her cleverness, had never measured, or even imagined, the world-wide difference between the view-points of a pueblo chief and an ambitious white woman. So she felt happy and secure, as she smiled in response to one of Barbara's bright glances, and noticed that Lieutenant Wemple was still dancing close attendance upon her young friend.

Barbara was gowned very simply in white, and carried a bouquet of Jacqueminot roses. Her shining black hair was drawn back from her forehead in loose, waving masses and filleted with bands of silver filigree. The brown-faced girl, in her white dress with the glowing roses at her breast, made a pleasing picture as she stood beside a cabinet of pueblo pottery, against a Navajo portière. Lieutenant Wemple, who stood nearest her, thought that, altogether, it made the most striking and suggestive composition he had ever seen, and that he would like to see her portrait painted just as she stood there; but that would be impossible, for no artist could paint two girls into one figure. And she—at one moment she was a bronze figure, listening with drooped eyelids, closed lips, and impassive face, and the next she was vibrant with life; her big black eyes, which would have redeemed a countenance of less attractiveness than hers, sparkled and glowed; her face was radiant with eager interest; and the Lieutenant felt that beneath those rich red roses must beat a heart as glowing with warm bright life as they.

Santa Fé might be, geographically, far in the deeps of the red and woolly West, but the feminine portion of its social circles did not think that any reason why they should relapse into barbarism. And as one means of preventing such a dire catastrophe, they made the law of party calls even as the laws of the Medes and Persians. Among themselves the men might groan and swear and protest as much as they pleased, but if any one of them neglected that duty the ladies forthwith hurled him from the circles of the Select into the outer shades of the Unassorted. After the night of Barbara's success these calls did not lag as usual, and Lieutenant Wemple, who was wont to be the last, was the very first to present himself.

Then followed a series of gayeties in which Barbara was the central figure, and Lieutenant Wemple her constant attendant. Whether it was a dinner, or a reception, or a picnic party up the canyon, or a horseback excursion to the turquoise mines, he spent as much time by her side as the other people allowed. Barbara enjoyed it all with the zest of a mortal let loose in wonderland, and thought that nowhere else in the world could there be such delightful people as her new friends. It seemed to her that she had at last come into her own inheritance and found the people among whom she really belonged. But she liked best of all the quiet afternoons at home, when she and Mrs. Coolidge sat in the placita, and Lieutenant Wemple came, and they three read and talked together.

The young officer thought her a more interesting companion than any white girl he had ever met. The world—his world—was all so new and marvellous to her that it was like opening its doors to some visitor from another planet. He took great pleasure in doing that service and in seeing how quickly and eagerly she absorbed everything she saw and heard and read; and he found her fresh and constant interest entirely delightful. So it soon came about that the quiet afternoons at home grew more and more frequent.

One day in early June they stood together in the placita and agreed that it was very beautiful. The proposition was evident enough and likely to cap forth enthusiastic assent from any one. For the plumy green branches of the locust tree were heavy with pendent clusters of odorous white bloom; the iris that circled the fountain was glorious in its purple raiment; the honeysuckle arch was a mass of red and white blossoms trumpeting their fragrance; beside it a great spreading rose-bush was yellow with golden treasure; the velvety, emerald turf was dotted with white and gold; the rose-bushes were weighted with opening buds or perfect flowers, and the warm, soft air was vivid with sunlight, and sweet with mingled odors.

So they could hardly have done anything but agree upon the beauty of the little court, even if they had wanted to quarrel. But for the hundredth time it struck him that it was very remarkable they should so often think alike. When he made mention of this remarkable fact, she flashed up at him one of her eager, brilliant glances. Then, meeting something more than usual in his look, she quickly dropped her eyes again, and over her manner there came that mystifying air of shyness and reserve, as if some invisible attendant had wrapped about her an impenetrable veil. In their early acquaintance he had often noticed that quick and baffling change in her manner, and had liked it, because it seemed to tell of a refined and sensitive nature. From their later frank and friendly intercourse it had been absent, and now, when it appeared again and seemed to take her away from him, his heart beat fast with the longing to tear the veil away.

For a moment she stood with her gaze resolutely upon the ground and her expression and figure impassive. But she felt his eyes upon her, and her brown fingers trembled over the yellow rose in her hand. Suddenly, as if compelled, she lifted her face and the look in his eyes called all her heart into hers. For a second they stood so, revealing to each other their inmost feeling, and then, covering her face with her hands, she ran into the house. The Lieutenant picked up the yellow rose she had dropped and went out through the street entrance, a very thoughtful look upon his countenance.

Wemple had not realized before what was happening to them both, although all Santa Fé, except themselves, knew it very well. But at last he understood that he loved her and that she knew it, and that she also knew she had confessed in her eyes her love for him. What was he going to do about it? That was the question he had to face and to settle; and he went out alone and tramped over the brown hills and across arroyos and through clumps of sage brush and juniper and cactus, and argued it out with himself.

He loved her, and she loved him. Yet—she was an Indian, and did he want an Indian wife? But after all that had passed between them, and the silent, mutual confession of the afternoon, could he in honor do else than marry her? Ever since he had come West he had held the firm conviction that an Indian can never be anything but an Indian, and that to attempt to make anything else out of him is not only a sheer waste of time, effort, and money, but is also an injury to the Indian himself, because it gives him desires and ambitions that can do nothing but make discord with his Indian nature.

But it seemed different with her. In truth, he told himself, she seemed more akin to the white than to the Indian race. That age-long heritage of religious belief and practice that has made a basis of character for the pueblo Indian did not seem to have found expression in her. But if after years should bring it to the surface and she should prove to be Indian at heart, would it raise a wall between them or would it drag him down, because of his great love for her, to that same Indian level? If that Indian nature was there now, patched over and hidden by present surroundings, would not happiness be impossible between them? And if he believed that unhappiness would be the sure result of their marriage would it not be more dishonorable to marry her than to leave her at once? But at the idea of leaving her a sharp pain pierced his heart. He thrust at it the thought that in the long run she would probably be happier if she were never to see him again. Then he ground his teeth together, whirled about and started for the town.

Presently he put his hand in his pocket and his fingers closed over Barbara's yellow rose. He raised it to his lips and something very like a sob trembled through his soldierly figure. And then suddenly, in a great wave, came the remembrance of her graces of mind and heart and body, and of how frank and simple and sincere she was, how sweet and gentle and womanly and winning. At the same moment his own faults rose up and upbraided him, and his heart cast away the arguments his brain had been weaving, and cried out with all its strength, "Indian or not, she is better than I!" All his white-man's pride and prejudice of race fell from him as he pressed her rose to his lips and kissed it again and again.

On the morrow it happened that Lieutenant Wemple was officer of the day at the post and his duties kept him so closely confined in and about the fort that he had not time to see Barbara. But in the latter part of the afternoon it became necessary for him to see the commanding officer. The Colonel had gone, he knew, on a business errand to the farther end of the town, and the Lieutenant started out to find him. His way back took him past the Coolidge residence. He was walking hurriedly down the street, in haste to return to his duties, his blonde head erect, his cap at right-eyed angle, his uniform buttoned tightly across his broad shoulders and around his trim waist, his sword on hip, and his eyes straight in front of him. But his thoughts were inside the adobe walls of the Governor's home and he was calculating how long it would be until, released from duty, he could hasten back to pour into a little brown ear the words of love of which his heart was full.

Across the street, in the shadow of a portal, an old Indian, gray-haired and wrinkled, was curiously surveying the Coolidge house.

The heavy, double doors of the placita entrance were open, and as Lieutenant Wemple strode past he heard a sound from within, a half suppressed exclamation in a voice that trembled with feeling. It sent through him a sudden shock, stopped him in mid-step, and swiftly turned him to the placita door. Barbara, in a white muslin gown, stood under the honeysuckle arch, her hands full of yellow roses which she had just been plucking from the bush that glowed behind her. She was looking at him with soft and glowing eyes, her eager face radiant with love, her lips still parted by the exclamation which sight of him had forced through them.

The old Indian under the portal considered him impassively for a moment and then sauntered across the street.

An instant only the Lieutenant stood looking at her, spellbound by the beauty and sweetness of the picture, and then he sprang to her side and gathered her in his arms, forgetful alike of the open doors behind them and of his duties at the fort. It was only for a moment, and then he took her hand and led her to Mrs. Coolidge.

But during that moment the Indian with the gray hair and the wrinkled face stood in front of the placita doors and looked at them with evident interest. When they went indoors he shut his thin lips close together, crossed to the other side of the street, and leaned against the column of a portal while he watched the doors and windows of the Governor's residence.

It was only a few minutes until Lieutenant Wemple appeared again and walked rapidly away. For army discipline must be remembered and maintained, even in times of peace and days of love. The old man gazed at him until he disappeared around a corner, and then crossed the street and knocked at the Coolidge door. Colonel Kate herself opened it and at once held out her hands in welcome, crying, "Entra! Entra!" She seized his hands and drew him in, pouring forth a voluble welcome in Spanish. He did not give much heed to her words, but coldly asked, in the same tongue:

"Where is my daughter?"

Barbara, in the next room, heard his voice, and her first unthinking thrill of pleasure was quickly followed by a sinking of her heart which chilled and saddened her happy face. Intuitively she knew what would happen.

"She is here," Mrs. Coolidge replied. "She will be so glad! Barbara! Come quickly! Here is some one very anxious to see you!"

The girl came slowly and stood before her father with downcast eyes. His piercing glance ran over her dress, and then he grunted in severe disapproval.

"Go, put on your own clothing. Then stand before your father."

"Yes, dear," chimed in Colonel Kate soothingly, "you must seem very strange to him in that dress,—scarcely like his daughter. Put on your native costume and come back to us quickly."

Barbara went to her room and Mrs. Coolidge began to tell her visitor, with her most charming enthusiasm and with all the delighted expletives which her knowledge of Spanish made possible, of Barbara's success, of her love affair, and of how very desirable the match would be. The old man listened quietly to the end, looked at her steadily for a moment in silence, and then spoke:

"No!"

Colonel Kate's eyes opened wide in amazement at the word. "What! Don Ambrosio! Surely—"

"He wishes to marry her?" the old man broke in.

"Indeed he does! He told me so scarcely ten minutes ago. He is very much in love with her and she with him!"

"No!" repeated the Indian emphatically. "It cannot be!"

"Surely, señor, you do not understand! You could not find a more desirable husband for Barbara! Why, he is a lieutenant in the army, a first lieutenant, too, and his position will take her into any society she wishes to enter. He has money enough to keep her well, and he loves her devotedly!"

"No! He forgets she is an Indian! He has seen her in all these clothes of the white women in which you have tricked her out, and he thinks she is the same as a white woman. She is not. She was born an Indian, and an Indian she must be until she dies. Never again shall she leave Acoma."

"Señor! How can you be so blind to your daughter's interests? You will break her heart! Surely you cannot be so cruel!"

But Mrs. Coolidge's protests were broken off by Barbara's return. The girl stood before her father with her eyes on the floor and her face cold and impassive. She was dressed again in the garments she had worn when she first entered the house, three months before, and she seemed a far different creature from the happy and radiant girl to whom her lover had but just said good-bye. Ambrosio looked her over approvingly.

"Now you are my daughter. Come."

With the pueblo children centuries of training have caused unhesitating obedience to parents to become an instinct. So Barbara did not question, but at once followed her father toward the door. Mrs. Coolidge was weeping. Barbara threw both arms around her neck and kissed her again and again. The girl's face was expressionless and there were no tears in her voice, but her wide, black eyes, paling now to brown, told the agony that was in her heart.

"Tell him," she whispered in English, "that I must go back. My father bids me, and I must go. My father will never again let me leave Acoma. Tell him I shall never see him again, but I shall love him always."

"My poor child!" sobbed Mrs. Coolidge. "We must find some way to bring you back!"

"It is useless to try. I know my father, and I know it will be impossible for me ever again to leave the pueblo. I must be an Indian all the rest of my life. But I shall love him always. Tell him so."

"Come!" called Ambrosio from the portal.

Half an hour later the train was carrying them back to Acoma. Colonel Kate at once sent a note to Barbara's lover, telling him what had happened. But the messenger, being a small boy, met other small boys on the way, and by the time the young officer read the news the Indian girl was well on her way toward home.

Lieutenant Wemple applied for leave of absence, and as soon as possible he followed old Ambrosio. At Laguna, where he left the railroad, he hired a horse and inquired the way to Acoma. It was the middle of the night, but he refused to wait for daylight, and started at once across the plain, galloping as though life and death depended on his mission. In the early morning he reached the great rock-island of Acoma, towering four hundred feet above the plain, and climbed the steep ascent to the village on its summit. A file of maidens, and among them his lover's eye quickly sought out Barbara, were coming from the pool far beyond, carrying water jars upon their heads, graceful as a procession of Caryatides. Wemple found his way to Ambrosio's door, where the old chief was sitting in the early sunlight. As he stopped his horse Barbara came up the street, her tinaja poised on her head. One swift and frightened flash of her black eyes was all the recognition she gave him as she hurried into the house.

Briefly the Lieutenant told the old man that he loved Barbara and wished to marry her. Inside the house the girl stood out of sight, listening anxiously for her father's reply, although she well knew what it would be.

"The señor forgets that my daughter is an Indian and that he is a white man."

"I do not care whether she is Indian or white. I love her and I want her to be my wife."

"You mean that you do not care what she is now. But after she is your wife you want her to be a white woman in her heart. You want to take her away from me, her father, and away from her mother, and her clan, and all our people, and make her forget us and forget that she is an Indian. No!"

"No, señor!" urged the Lieutenant, "I do not wish her to forget you. She shall come back to visit you whenever she wishes."

A crafty look came into Ambrosio's eyes. "There is one way," he went on quietly, not heeding Wemple's reply, "in which you may make her your wife. But there is only one."

The officer leaned eagerly forward in his saddle and the girl inside the door clasped her hands and listened breathlessly. The old Indian went on, slowly and deliberately, as if to give his listener time to weigh his words, while his keen eyes searched the white man's face.

"You think my daughter loves you well enough to forsake and forget her people if I would let her. Do you love her well enough to leave your people and become one of us? Do you love her well enough to be an Indian all the rest of your life, wear your hair in side-locks, enter the clan of the eagle, or the panther, become Koshare or Cuirana, dance at the feasts, forget your people, and never again be other than an Indian? If you do, speak, and she shall be your wife."

Ambrosio shut his lips tightly and waited for the young man's answer. And the young man stared back, his ruddy cheek paling under its sunburn, and spoke not. A whirling panorama of visions was filling his brain as he realized what the old chief's words meant. He saw himself living the life of these people; renouncing everything that meant "the world" and "life" to him—everything except Barbara; driving burros loaded with wood to town and tramping about its streets with a basket of pottery at his back; saw himself with painted face and nude, smeared body dancing the clownish antics of the Koshare; planting prayer sticks; sprinkling the sacred meal; taking part and pretending belief in all the heathen rites of the pueblo secret religion—and then Barbara sprang out of the house, crying to her father in the Indian tongue, "Wait! Wait!"

Both men turned toward her inquiringly. She stood before them, hesitating, excited, her eyes on the ground, as if anxious but yet unwilling to speak.

"Father," she began in Spanish, "it is useless for you and the señor to speak longer about this. For since I have returned to my home I do not feel as I did before." She stopped an instant and then went on hurriedly, pouring out her words with now and then little, gasping stops for breath. "Now I do not wish to marry him. I wish to marry one of my own people. He is not an Indian and never can become one. I know now that I can never be anything but an Indian and so it is better for me to marry one of my own people. I do not wish to marry the señor, even if he should become one of us."

Wemple looked at her blankly, as if hardly comprehending her words, and then cried out, "Barbara! You cannot mean this!"

"You see, señor," said the old man, "there is nothing more to say."

"Is there nothing more to say, Barbara?" Wemple appealed to her in a broken voice.

She did not look at him, but shook her head and went back into the house.

Lieutenant Wemple turned his horse and with head hanging on his breast rode slowly, very slowly, back toward the long declivity leading to the plain below. If he had not ridden so slowly this tale might have had a different ending.

Ambrosio went into the house and began telling his wife what had happened. Barbara took an empty tinaja and said she would go for more water. When she stepped outside she could still see the forlorn figure of her lover riding slowly down the trail. Her heart yearned after him as she bitterly thought:

"He will believe it! I made him believe it! And I can never tell him that it is not true!"

Then something set her heart on fire and put into it the thought of rebellion. She looked around her at the village and thought of the life it meant for her, as long as she should live; of the heartbreak she would have to conceal from sneering eyes, of the obscene dances in which she would soon be forced to take part, of the persecutions she would have to suffer because she could no longer think as her people thought; and hatred of it all filled her to the teeth. Rebellion burned high in her soul and with clenched fingers she said to herself, "I hate the Indians! In my heart I am a white woman!" She cast one more longing, loving glance at the disappearing figure and resolution was born in her heart: "And I will be a white woman, or die!"

She looked hastily about. No one seemed to be watching her. She dropped the tinaja beside the house and walked swiftly—she feared to run lest she might attract attention—to the edge of the precipice. There she looked down over the flight of rude steps, hacked centuries ago in the stone and worn smooth by many scores of generations of moccasined feet, which was once the only approach to the fortress-pueblo. It was three hundred feet down that precipitous wall to where the steps joined the trail, but from babyhood she had gone up and down, and she knew them every one. From one to another she fearlessly sprang, and over several at a time she dropped herself, catching here by her hands and there by her toes and finally landed, with a last long leap, on the trail. One glance told her that her lover had almost reached the road at the foot of the cliff and that if he should then quicken his pace she could scarcely hope to catch him. But love and determination made steel springs of her muscles, and she bent herself to the task. For if she could not overtake him there was no hope anywhere.

Lieutenant Wemple, with his head still hanging on his breast and his horse creeping along at its own pace, turned from the declivity into the road which would take him back to Laguna, to the railroad, and to his own life. There the horse decided to take a rest; and Wemple, aroused to realization of his surroundings by the sudden stop, jerked himself together again, straightened up, sent a keen glance across the plain and over the road in front of him, and struck home his spurs for the gallop to the railroad station. As the horse leaped forward, he thought he heard some one calling. Turning in his saddle he saw Barbara running toward him, her breast heaving, her arms outstretched. She almost fell against the horse's side, panting for breath.

"It was not true," she gasped, "what I said up there! I wanted to save you. Take me with you if you still love me! For I love you and I hate—I hate all that—" turning her face for an instant toward the heights above them—"and if you do not want me I must die, for I will not go back."

For an instant their eyes read each other's souls, and then she hastily put up her hand to stop him from leaping from his horse.

"No, no! Do not get off! They will be sure to follow us and we must lose no time. Take me up behind you and gallop for Laguna. If we can catch the next train we'll be all right!"

She seized his hand and sprang to her seat behind his saddle. He turned and kissed her.

"Put spurs to your horse," she said. "They will be sure to follow us soon."

There was need of haste, for scarcely had the horse pricked up his ears and sprung into a long gallop when they heard loud shouts from the top of the mesa.

"Hurry, hurry!" exclaimed Barbara. "They have found me out and they will follow us!"

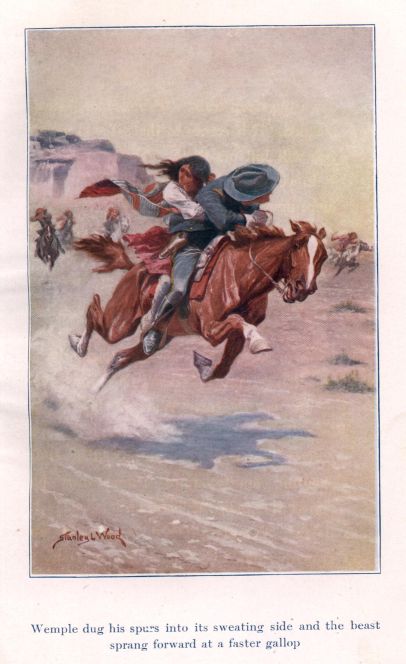

Scarcely had she spoken when the sound of a rifle report came from the top of the cliff, and Wemple's left arm dropped helpless beside him.

"They dare not shoot to kill," she said, "but they think they can frighten you, and they may cripple the horse. My darling, you will not let them have me again?" The terror in her voice told how intense was her fear of capture.

"Sweetheart, they shall not have you again unless they kill me first!"

A dozen Indians were galloping recklessly down the steep trail. "Promise me," Barbara, pleaded, "if it comes to that, if you must die, you will kill me first! For it would be hell—it would be worse than hell—to go back there now!"

Wemple did not answer. "Promise me that you will," she begged. "You do not know what you would save me from; but believe me, and promise me that you will not send me back to it!"

"I promise!" he answered as another shot whistled in front of them and clipped the top of the horse's ear. Wemple dug his spurs into its sweating side and the beast sprang forward at a faster gallop. The Indians, shouting loudly, were urging their ponies across the plain at breakneck speed. Lieutenant Wemple glanced back again and a frown wrinkled his forehead, as he said, "If our horse does not break down we may keep ahead of them until we reach Laguna."

Barbara patted the horse and whispered soft words of encouragement and then under her breath she sent up a fervent petition to the Virgin Mary to protect them. Looking back, she recognized their pursuers, and told Wemple that one of them was her brother, and another was a young man whom her parents wished her to marry. This one had a faster horse than the others and perceptibly gained upon the fugitives. He left the road where a turn in it seemed to offer an advantage and, galloping across the plain, was presently parallel with them and not more than two hundred yards away. He raised his gun and Wemple, with quick perception noting that his aim was toward their horse's neck, gave the bridle a jerk that brought the animal to its hind feet as the bullet whistled barely in front of them. It would have been quickly followed by another, but the Indian's pony stumbled, went down on its knees, and horse and rider rolled over together.

The other Indians came trooping on in a cloud of dust, yelling and shouting, and now and then firing a shot, apparently aimed at the good horse that so steadily kept his pace.

"They only want me," said Barbara. "If they can overtake us there are enough of them to overpower you. They will not try to do much harm to you, for they would not dare. But they will take me and carry me back with them—if you let them."

"I will not let them," he replied between set teeth.

At last Wemple saw that their pursuers were slowly but surely gaining on them. Barbara saw it too, and she redoubled her prayers to the Virgin, and both she and her lover with words and caresses strove to keep up the courage in their horse's heart. The good steed was of the sort whose spirit does not falter until strength is gone, and he seemed to understand that these people on his back were under some mighty need. For with unwavering pace he kept up his long, swift gallop, notwithstanding his double burden and the distance he had travelled before the race began.

So they kept on, mile after mile, with their pursuers gaining, little by little, upon them, and when at last they neared Laguna the Indians were within a hundred yards. A banner of smoke across the plain told them that the east-bound train was approaching.

"I believe we can make it!" exclaimed Wemple, as they heard the engine's announcing scream. Apparently their pursuers guessed what the fugitives would try to do, for as they saw the train they shouted and yelled louder than before and urged their ponies to a still higher speed. They gained rapidly for a little while, for the Lieutenant's horse was beginning to flag, and Wemple, leaning to one side, gave the bridle into Barbara's hands and, with left arm dangling useless, reached for his revolver. He began to fear that they might yet head him off and surround him. They outnumbered him hopelessly, but he would try to fight his way through them. If worst came to worst,—he would save two shots out of the six,—Barbara should not fall into their hands.

The train drew into the station and the Indians were not more than a hundred feet behind him. The horse's faltering gait and heaving sides showed that he had reached almost his limit of strength. Some dogs ran out from a house, barking furiously. But being in his rear they only made Wemple's horse quicken his pace. They darted at the heads of the ponies, which shied and pranced about, and so lost to their riders some valuable seconds.

The train was already moving as Wemple dashed up to its hindmost car, his horse staggering and their pursuers almost upon them.

"Jump for the car-steps!" he shouted to Barbara. She had not leaped and clambered up and down the stair in the Acoma cliff all her life for nothing, and her strength and agility stood her in good stead in this moment of supreme necessity. She leaped from the horse's back, landed upon the upper step, and whirled about to assist her lover.