This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Meadow-Brook Girls in the Hills

The Missing Pilot of the White Mountains

Author: Janet Aldridge

Release Date: February 26, 2006 [eBook #17865]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MEADOW-BROOK GIRLS IN THE HILLS***

Author of the Meadow-Brook Girls Under Canvas, The Meadow-Brook Girls Across Country, The Meadow-Brook Girls Afloat, The Meadow-Brook Girls by the Sea, etc.

"I hear that Janus Grubb is going to take a passel of gals on a tramp over the hills," observed the postmaster, helping himself to a cracker from the grocer's barrel.

"Gals?" questioned the storekeeper.

"Yes. There's a lot of mail here for the parties, mostly postals. Can't make much out of the postals, but some of the letters I can read through the envelopes by holding them against the window."

"Lemme have a look," urged the grocer eagerly.

"Not by a hatful. I'm an officer of the government. The secrets of the government must be guarded, I tell ye. There's six of them——"

"You don't say! Six letters?" interrupted the grocer.

"No, gals. One's name is Elting. She's what they call a chaperon. Another is Jane McCarthy—I reckon some relation of the party who wrote me a letter asking what I knew about Jan. I reckon Jan got the job on my recommendation."

"Who are these girls, and what do they think they're goin' to do up here?"

"Call themselves 'The Meadow-Brook Gals.' Funny name, eh?" grinned the postmaster, balancing a soda cracker on the tip of his forefinger, then deftly tossing it edgewise into his open mouth. "They pay Janus ten dollars a week for toting them around," he chuckled. "Read it in the McCarthy party's letter to Jan."

"What are they going to do up in the hills?"

"Climb over the rocks for their health," grinned the postmaster.

"Huh! When they coming to town?"

"On the evening mail train to-day. Hello! There's Jan now on his way to meet them. Say! Will you look at him! Jan's had his whiskers pruned. And, I swum, if he hasn't got on a new pair of boots. Git them of you?"

The storekeeper nodded.

"How much?" demanded the postmaster.

"Four seventy-three. Knocked down from five dollars. Wish I'd known he was going to draw down ten dollars a week for this job. I'd have got four seventy-five at least for the boots."

"Never mind, you can let Jan make it up on something else," comforted the postmaster. "Reckon I'll go down to the station to see the folks come in."

"I was going to ask you to look after the store while I went down," returned the grocer.

The postmaster decided that he wouldn't go. The other man hurried out, while the government employe helped himself not only to another handful of crackers, but to a liberal slice of cheese as well. He stood munching his crackers and cheese and gazing out reflectively into the gathering twilight, when he suddenly started and peered more keenly. That which had attracted his attention was a stoop-shouldered man. The fellow wore a soft hat, the brim of which was slightly turned up in front, but his face was well masked by a huge pair of green automobile goggles.

"Well, I swum!" ejaculated the postmaster. "If I didn't know the feller was in jail up at Concord, I'd say that was Big Charlie. Hm-m-m. No. This one is too stooped for Charlie. Charlie's six foot two in his socks. I wonder who this fellow is?"

Even then the mail train was whistling, and the postmaster began bustling about preparing to receive the evening mail, always an event for him as well as for the villagers, who ordinarily flocked into the office, hoping to catch sight of a familiar handwriting or hear a name mentioned that would give them foundation for a bit of gossip.

It was while he was thus engaged that five young girls and a young woman some years their senior got down from a coach to the railway platform, where they stood gazing expectantly about them. The young women were dressed in tasteful blue serge suits, with hats of the same material, a sort of uniform, the villagers decided, and, had not the station platform been too dark, the eager spectators would have seen that the faces of the visitors were tanned almost to swarthiness.

"Shall I ask some one if Mr. Janus Grubb is here?" questioned one of the girls.

"No, wait a moment, Harriet," answered the young woman in charge of the party, "I will ask. Surely the guide should be here to meet us, since Miss McCarthy's father had arranged for it."

"You are looking for a guide, Miss?" questioned a voice at her side. Miss Elting, the guardian of the party, glanced up inquiringly. She looked into a face of which she could see but little. The most marked feature of the face was a pair of huge green automobile goggles. These gave to the face, which she observed wore a peculiar pallor, a sinister effect, caused no doubt by the goggles.

"We are looking for Mr. Janus Grubb. Are you he?" she asked sharply.

The man nodded.

"This way," he said in a hurried voice.

"Come, girls," urged the guardian; "I thought Mr. Grubb would not fail us."

"And a funny looking person he is," scoffed Jane McCarthy. Her companions, Hazel Holland, Margery Brown and Grace Thompson, giggled. Harriet Burrell plucked the sleeve of the guardian's light coat.

"I wouldn't go with him, Miss Elting," she urged.

"Why not, dear?"

"I don't like his looks. Make him take off his glasses. There is something peculiar about him."

"This way, please!" the guide's voice took on a tone of command. They had nearly reached the upper end of the platform when he issued his peremptory order. Just then a shout was heard to the rear of them. A man came running toward them.

"Hey, there!" he called. The girls halted. "Are you the Meadow-Brook Gals?"

"Yes, sir," answered Miss Elting, brightly.

"Well, I'm mighty glad to know about it. 'Pears as if you didn't know where you was going."

"And who are you, sir?" demanded the guardian.

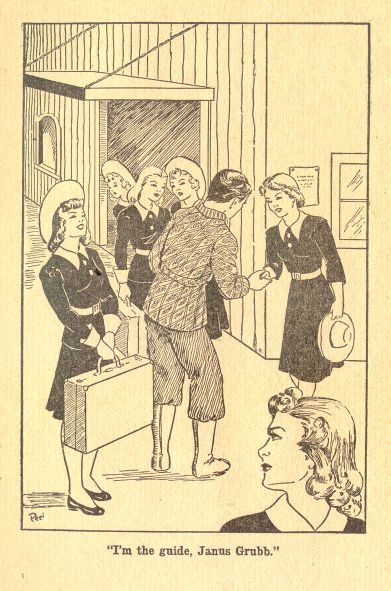

"I'm the guide, Janus Grubb."

"Will you listen to the man!" chuckled Jane.

Harriet nodded with satisfaction.

"Janus Grubb? Why, sir, I don't understand. We have already met Mr. Grubb," cried Miss Elting.

"Somebody is crazy," muttered Jane, "I think the man with the green goggles is the lunatic."

"Show me the man who said he was myself," roared the newcomer.

Miss Elting turned to point out the man who had been piloting them along the platform. She uttered a little exclamation. The man with the goggles was nowhere in sight. "Why, where did Mr. Grubb go?" she exclaimed.

"I'm Janus Grubb and I'd like to see the man who says I'm not," shouted the guide indignantly, forgetting that he was addressing a woman.

"Please come to the station agent with me. If he identifies you, I am satisfied," declared Miss Elting with dignity, looking disapprovingly at the excited man. She moved back toward the station, followed by her charges, and a moment later the railroad agent had identified Janus to her entire satisfaction.

The girls giggled. There was something funny about their having been deceived so easily, but Miss Elting did not regard matters in that light. "Can you tell me who the man with the goggles is"? she demanded, turning to the real guide after the identification had been made.

"If I knew him there'd be trouble," threatened Janus. "What kind of a looking feller was he?"

Harriet answered, giving a very excellent description of the man with the goggles.

"Don't know him," said Janus, stroking his whiskers reflectively. "Lucky for him that I don't. What do you want to do now?"

"Go to the post-office," cried the girls.

"There must be mail for as there," added Hazel. "I'm so anxious to hear from home."

"Yeth, tho am I," lisped little Grace Thompson.

"You have arranged for us at the hotel for to-night, haven't you?" demanded Jane McCarthy. "Father said you would look after these matters for me."

"It's all right, Miss. We'll go to the postoffice now. I'll look after your baggage when we get you settled for the night. We won't take it away from the station till we talk over what you want to do. Are you ready?"

They walked down the street, laughing and chatting, a happy lot of girls, followed by a group of curious villagers, who even accompanied them into the post-office. It was unusual to see so many pretty girls in Compton, for summer visitors seldom came to the place. Furthermore, these were different from any visitors ever seen there, so far as dress was concerned. While waiting for the mail to be distributed, the girls laughed and talked, apparently utterly oblivious of the presence of the staring villagers. Miss Elting inquired for mail for the party as soon as the wicket was opened.

"Here, Tommy, is a letter for you," she smiled. Grace took the letter eagerly. "And here are letters for Harriet, Hazel, and Margery. There is one for me, too. It is from your father, Jane."

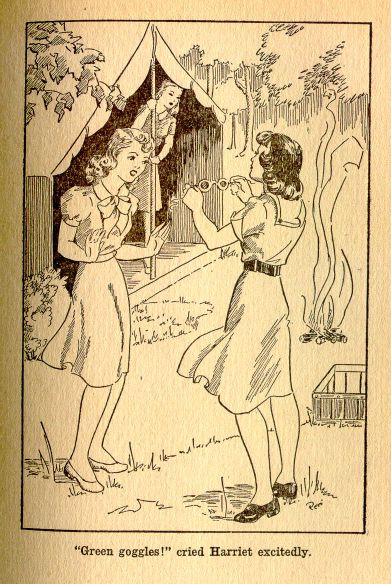

"I have a letter here from Dad. I—will you look at that?" Jane stood staring at the window. For a brief instant she had caught sight of a man wearing a huge pair of goggles. He was peering through the post-office window at them. But as she looked, the man disappeared. "It was our friend with the green goggles again as sure as I'm alive!" she exclaimed. "He was staring in here for all he was worth, but the minute he saw me looking at him he vanished."

"I am afraid we are going to have trouble with this mysterious individual," declared Harriet. "He seems to have developed a peculiar interest in our affairs that is far from flattering."

"We are not going to be annoyed as we were last year," said Miss Elting firmly. "Mr. Grubb, there is something very strange in all this. If for any reason you know this man or have even the slightest idea of his identity I must ask you to be perfectly frank with me."

Janus Grubb declared solemnly that he had not the least idea who the man could have been. Nor had he been able to find any person who had seen the fellow approach them. Miss Elting and the guide stepped out to the porch, followed by the girls, still chatting over the news from home contained in their letters.

"Now, where do you want to go first?" asked the guide after they had reached the porch.

"We will trust to your judgment," answered Miss Elting. "You know best. We wish to try a little mountain climbing and we wish to see the larger of the White Mountains. We would like to see everything of interest in the White Mountain country."

"That's a pretty big contract," chuckled Janus; "but I reckon we can show you what you want to see. For instance, there's Mt. Chocorua, Moosilauke, Mt. Washington, Mt. Lafayette and as many more as you like, all the real thing and offering all the climbing you will care to do, unless you want to follow the trails that all the visitors take."

"No, we do not. We prefer to blaze our own trails, or, rather, to have you do so, and the rougher they prove the better, as long as it is safe. My girls are equal to any sort of rough-and-tumble climbing. How do we get to the mountains?"

"I've engaged a carry-all to take us out to the foothills. From there you can walk or ride. If we take the rough trails, of course we'll have to climb."

"I shall ask you to lay out your route, then arrange to have some of our baggage shipped on to meet us, say a week from now. Our necessary equipment we can carry. The girls are used to shouldering heavy packs. You will provide climbing equipment. I understand from Miss McCarthy that you are a climber."

"I'm everything and anything in the White Mountain Range," answered the guide boldly.

"Then, what do you say if we make Mount Chocorua first?"

"Perhaps you had better decide for us."

"This mountain is three thousand five hundred feet high. The way we shall take you will, I think, find rugged enough to please the young ladies," added Janus, with a grin behind his whiskers. "What time will you be ready to start?"

"As soon after daylight as we shall be able to get our breakfast."

"He had better bring our baggage from the station to-night. Then we can have our packs in readiness," suggested Harriet Burrell.

"Yes, please do that, Mr. Grubb."

"Anything else, Miss?"

"Not that I think of for the moment. We have our tent in sections. We also shall pack our blankets and such other things as will be needed. The rest of the equipment can be sent on ahead to meet us wherever you say. I don't know what the most convenient point would be. Where would you suggest?"

"I can send it to the Tip-Top station on Moosilauke. Will that do?"

"Yes."

"Then I'll be going," said the guide. "I'll take you over to the Compton House, and if you want to see me again this evening, you can call me on the telephone."

Janus had started to move toward the steps preparatory to going about his duties, when an exclamation from Harriet Burrell caused them to turn sharply to her.

"There he is! There is the man with the goggles!" she whispered, pointing toward the store. They saw a stoop-shouldered man standing with his back against the large window. He was facing them, but, his face being in the shadow, they were unable to distinguish the features. The light in the store being at his back, and his head slightly turned to the steps, toward which Janus was moving, Harriet Burrell was enabled to look directly through one of the lenses. She saw that the glass was green and that it masked effectually the eyes of the strange man.

"Quick, Mr. Grubb!" cried the girl. "The man again! Find out who he is!"

Janus, who had moved down to the second step, now started back, and was on the porch with one bound, thrusting the Meadow-Brook Girls aside in his eagerness to reach the man who had impersonated him.

"Where is he?" shouted Janus, in a voice that brought most of the villagers from the store on the run. "I see him!" Grubb made a leap, when, as though he had vanished into thin air, the stranger disappeared from sight.

The Meadow-Brook Girls gasped in amazement. But Harriet Burrell, quicker in thought and action than even the guide himself, leaped from the end of the porch and sped swiftly around the side of the store toward the rear yard.

"Come back here!" shouted the guide. Harriet halted. She hesitated at sight of the black shadows there rather than at the command. She distinctly heard some one floundering over a high board fence that shut in the rear yard of the store and post-office. Janus's hand was on her arm.

"Well, I swum!" he exclaimed.

"Oh, that's too bad. He got away," cried Harriet ruefully. "I was too slow. I could have caught him just as well as not, had I not been so stupid as to wait."

Harriet and the guide walked to where her companions were standing, not certain what they ought to do, not quite sure what had occurred.

"This one's all right," chuckled Janus. "She's got the spunk, but she needs watching. She'll get the whole outfit in trouble. Tell me about it," he concluded, turning to Harriet.

"You saw it, sir?" asked Harriet quickly.

"I didn't see anything," returned the guide. "The man was standing on the spot where you are standing at this moment. He was listening to what we were saying, but for what reason I can't imagine. I made the mistake of calling to you. I shouldn't have done that. When you started for him he disappeared."

"Yes, we saw him; then we did not," added Miss Elting.

"You didn't stop to think. You were too excited, and, besides, I was nearer to the man than were the rest of you girls. He simply dropped down on all fours and ran off the porch like a dog or a cat."

"Well, I swum!" muttered the guide.

"Mr. Grubb, I don't like this," declared the guardian severely.

"Neither do I, Miss," he replied in a tone that made the girls laugh.

"I am not certain what I ought to do, Mr. Grubb," continued Miss Elting. "If it means that my girls are to be annoyed and disturbed, we shall be obliged to look for another guide. You know I have a personal responsibility in this matter. I shall have to think it over. Unless you can give me reasonable assurance that these incidents will not be repeated, then I shall have to make some different arrangements. You will please send the luggage to the hotel as suggested. I will see you early in the morning, at any rate. Come, girls."

Janus, somewhat downcast and very thoughtful, led the way to the Compton House, a short distance down the street from the post-office and grocery store. The girls began talking almost as soon as they had left the store porch.

"Please, please don't discharge him," begged Hazel. "He is such a nice man."

"And thuch nithe whithkerth," added Grace Thompson. "He lookth jutht like an uncle of mine, who——"

"I agree with the girls, Miss Elting," interjected Harriet. "We are able to take care of ourselves. Perhaps this is simply another crazy man, of whom we shall be rid as soon as we leave the village for the mountains in the morning. Please don't dismiss Mr. Grubb."

"I shall have to think this matter over," was the guardian's grave reply. "We do not care to repeat last summer's experience. You remember what came of relying on the assurance of a stranger." Miss Elting referred to the manner in which they had been tricked by the man who had charge of her brother's houseboat the previous summer, and whose treachery had caused them so much annoyance.

None of the Meadow-Brook Girls made reply. They were as fully puzzled in this respect as was their guardian. Miss Elting, however, pondered over the mystery all the way to the hotel. They found the Compton House a very comfortable country hotel, rather more so than some others of which they had had experience during their previous journeys. Arriving at the hotel, they hurriedly prepared for supper, for they were late and the other guests of the house had eaten and left the dining room before the Meadow-Brook Girls had even entered the hotel.

By the time supper was finished, their luggage had come over from the station. Janus Grubb, went home, not a little troubled as well as mystified by the occurrences of the evening. Who the man could possibly be he had not the remotest idea. He tried to recall who of his acquaintances might be guilty of playing such a joke on him. To the mind of Janus the incident could have been only a prank, though he questioned the good taste of any such interference between himself and his customers.

On the contrary, Miss Elting and her young charges attached more serious meaning to the performances of the man who had regarded them through green goggles. They regarded the incident with suspicion and agreed to proceed only with the utmost caution.

None of the readers of this series need an introduction to Harriet Burrell and her three friends, who figured so prominently in "THE MEADOW-BROOK GIRLS UNDER CANVAS." It was in this narrative that the four chums made their first expedition into the Pocono woods and for several happy weeks were members of Camp Wau-Wau, a campfire association of which the girls became loyal members. At the end of their stay in camp they decided to walk to their home town, sending their camping outfit on ahead.

The story of their journey home on foot was told in the second volume, "THE MEADOW-BROOK GIRLS ACROSS COUNTRY," in which an Italian and his dancing bear, a campful of gipsies and a band of marauding tramps furnished much of the excitement. Then, too, the friendly aid and rivalries of a camp of boys known as the Tramp Club furnished many enjoyable situations.

It was in the third volume, "THE MEADOW-BROOK GIRLS AFLOAT," that Harriet Burrell and her friends were shown as encountering a considerable amount of adventure. The girls led an eventful life on the old houseboat on one of the New Hampshire lakes, and also encountered a mystery which, with the help of the Tramp Club, was run to earth, but the solving of it entailed the loss of the "Red Rover," their houseboat.

And now the Meadow-Brook Girls were about to spend a few weeks among the "Marvelous Crystal Hills," as the White Mountains in New Hampshire have been aptly termed.

Much time and thought had been spent in preparing properly for this long vacation jaunt. Camp equipage had all been overhauled, and much that would serve excellently where there was transport service had been discarded for this journey into the hills.

Resting for a while after finishing supper, the girls began to make up neat packs containing such bare equipment and food supplies as they believed to be indispensable. Then there were the tent, blankets and cooking utensils to be looked after. Of course, the guide would carry much of this dunnage, yet our girls were no weaklings, and no one of them expected to shirk carrying her fair share of the load.

It was after nine o'clock when Harriet and her chums finished the making-up of the packs. Soon after a clerk knocked on the door of Miss Elting's room.

"There's a man below who wishes to speak with you," the clerk informed her.

"It must be Mr. Grubb," guessed the guardian, and left her packing to go downstairs. She glanced into the lobby of the hotel; then, not seeing Janus there, stepped into the parlor. A man, a stranger, was sitting near a door that led out to the hotel veranda. In the light of the kerosene lamp that hung suspended from the ceiling she was not able to make out his features at first. She saw that he wore a heavy black beard, that he was rather roughly dressed, but that his hands were white.

"Are you the man who wished to speak with Miss Elting?" she asked, confessing to herself that she did not wholly like the appearance of the man.

"Yes," he answered, rising. Now that the light fell on his face she noted that he had a low, receding forehead. His beard covered the greater part of his face.

"About what do you wish to speak with me?"

"Well, it's rather a delicate matter, Miss," the man made reply, gazing down at the carpet, twisting his soft felt hat awkwardly. "I—I wanted to ask if you needed any assistance."

"What do you mean?"

"You are going into the mountains?"

"Yes, sir."

"You will need to have some one to show you the way and look after you and your party."

"We already have engaged some one to do that. You mean a guide, I suppose?"

He nodded.

"May I ask your name?"

"John Collins."

"Do you live here?" she asked, curious to know more about the man, whom she began to distrust.

"Not now. I live over in the next village. I was in town and heard that you folks wanted a guide. I know more about the White Mountains than any other man in the State of New Hampshire. I can show you more, and take better care of your party, than anybody else you could find."

"Do you know Janus Grubb?"

"Ye—yes," Collins twisted uneasily, "I know him."

"He is to be our guide. The arrangements were made some time ago by the father of one of our young women. Mr. Grubb starts with us tomorrow morning, unless there should be some change in the arrangements."

"I'm sorry, Miss."

"I'm sorry, too, since you have been so kind as to offer your services," replied the guardian politely.

"I didn't just mean it that way, Miss. I meant about Janus."

"How so?"

"I don't just like to say. Yes, I will, too. Do you know anything about Jan Grubb?"

"No," admitted Miss Elting.

"Then you'd better ask. I am afraid you are putting too much confidence in him."

"Mr. Collins, please be more explicit. What do you mean?"

"You'll find out after you've got out into the hills. He doesn't know any more about the hills than a little yellow dog that's spent all its life in town. He'll get you into all kinds of trouble, and then he'll leave you to get out of it as best you can. You remember what I tell you."

"Of course, I thank you for telling me," answered the guardian rather stiffly. "However, we are quite satisfied with Mr. Grubb. As I understand it, he is a highly respected citizen of Compton and an efficient mountain guide. That will be quite sufficient for us."

"I need this job. I—I need the money, Miss," whined the stranger.

"I am satisfied with the arrangements I have already made." Miss Elting turned to leave the room.

"My family needs it. I've been out of work a long time, and——"

"I am very sorry. I wish it were in my power to assist you, but I have very little voice in the matter. Another person—the one who is paying the expenses of this trip—attended to all that. You will see that it is quite useless to plead, deep as my sympathy is for you."

The man rose and eyed her with an expression that was particularly unpleasant to behold. Miss Elting returned her strange visitor's gaze. Something other than his looks repelled her, yet there was nothing in either manner or words to account for this feeling of repulsion on the part of the guardian.

"In case anything should occur to make it necessary for us to look further for a guide I shall remember you," she said slowly. "I suppose I can reach you here at Compton?"

"N—n—no," was the hesitating answer. "But if you need me, I'll he about. Mark what I tell you, Jan Grubb is going to get you into a fine mess! You will be sorry you ever engaged him; that's all I've got to say about it. Good night, lady."

"Good night, Mr. Collins," replied the woman coldly. His final words, so full of rancor, had destroyed what little sympathy he had aroused in her. Miss Elting stood aside while the man stepped toward the door.

At this juncture Harriet Burrell appeared in the doorway leading to the hall. She had missed Miss Elting, and, not finding the guardian in her room, had come downstairs in search of her. Harriet had not known that the guardian was engaged.

"Oh, I beg your pardon, Miss Elting. I did not know—I thought you were alone."

"It is all right. Come in, Harriet. What did you wish?"

Harriet did not reply. Instead, she gazed perplexedly at the retreating form of Miss Elting's late caller.

"You'll be sorry you ever took up with that hound," flung back the fellow, turning as he was about to step out on the veranda.

Miss Elting made no reply. Her lips tightened a little, then she turned with a half-smile, regarding Harriet's frowning face quizzically.

"What does it mean, Miss Elting?" questioned the girl.

"I don't know, my dear. The man wanted to act as our guide. I am glad he isn't the one who is to lead us over the mountains. I don't like him at all. You heard what he just said?"

Harriet nodded.

"He was referring to Mr. Grubb."

"Oh!"

"I don't know what to make of it. What reason do you suppose he could have for coming to me in this manner? It is all very strange."

"I don't know, Miss Elting. I am wondering."

"Wondering what?"

There was something in the set of the shoulders, in the swing of them as the man walked away, in the poise of the head, that had impressed Harriet Burrell as being vaguely familiar. Something of this must have been reflected in the Meadow-Brook Girl's face, judging from the guardian's next question.

"Of what are you thinking, dear?"

"I have seen that man before, Miss Elting."

"Where?"

"I don't know. My memory connects him with something unpleasant. I wish I knew what it is, for I am positive there is something wrong with him. Wait! I know! I know of whom the man reminds me. Can't you see it? Don't you know?" cried Harriet eagerly.

The guardian shook her head.

"Who do you think it is, Harriet?"

Harriet Burrell whispered something in the ear of the guardian. Again Miss Elting shook her head, this time with decision.

"Wrong, this time. There isn't the slightest resemblance that I could observe. I thought of that, too. But let's not bother our heads about it any further. We have things of greater importance to consider this evening, and, besides, we must go to bed soon; we are to make an early start in the morning, you know."

Harriet shook her brown head slowly. She was positive that she was right in her identification of the visitor, Collins. She determined to ask some questions at the first opportunity. This she did on the following morning, inquiring of the hotel clerk about the man who had so strangely called on Miss Elting. The clerk said he had never heard of the man. In the preparations that followed Harriet forgot about the caller. Grubb had a carry-all at the hotel before they had finished their breakfast. The equipment for the party occupied little room. Janus had consulted with Miss Elting about the food supplies, and these were packed in the smallest possible space, with the exception of a few packages for their use before they got into the mountains.

The drive to the point where they would leave the wagon would occupy the greater part of the day. The girls looked forward to that day's journey with keen anticipation. They started out decorously and quietly, for the inhabitants of the village were early risers and the girls did not wish to attract unpleasant attention to themselves. Once they were well out of the village, however, the Meadow-Brook Girls' spirits bubbled forth in song, shout and merry laughter. The air was crisp and cool until the sun came up, then it grew warm.

Janus, sitting up by the driver, was almost sternly silent. Miss Elting, in the light of the previous evening's interview, regarded him from time to time with inquiring eyes. She could not believe what her caller had told her of their guide. Janus was plainly an honest, well-intentioned man. Of this she had been reassured that morning in an interview with the proprietor of the Compton House.

At noon, their appetites sharpened by the bracing air and the fact that they had eaten an early breakfast, the party made a halt. The horses were unhitched and allowed to graze beside the road. The guide built a fire, Harriet and Jane in the meantime getting out something for their luncheon, which was to be a cooked one instead of a "cold bite." Hazel, Jane and Margery spread a blanket on the ground, while Tommy sat on a rail fence, offering expert advice but declining to assist in the preparations.

It was a merry meal. Even Janus was forced to smile now and then, the driver making no effort to conceal his amusement over the bright sallies of the Meadow-Brook Girls.

"Come! We must be going, unless you want to camp beside the road to-night," urged the guide. The girls had finished their luncheon and were strolling about the field.

"Why, we haven't thettled our dinner yet," complained Tommy.

"You'll have it well settled in less than an hour. The road from here on is rough," returned Janus. "You'll be wanting another meal before the sun is three hours from the hills."

"We want to pick some wild flowers," called Margery.

"Girls, don't delay us! The driver wishes to get back home to-night and we must reach the camping place in which Mr. Grubb has planned for us to spend the night," warned the guardian.

"Yes, we've got to hike right along," agreed Janus. "Hook up those nags and be on the way, Jim," he added, speaking to the driver.

It was only a short time until they were on the way again. The country was becoming more sparsely settled, the hills more rugged and the forests more numerous. Here and there slabs of granite might be seen cropping up through the soil; in the distance, now and then, they were able to catch glimpses of the bare ridges of the mountains toward which they were journeying.

"Those mountains," explained the guide, "are called 'The Roof of New England.' There's not much of any timber on top, but on the sides you will find some spruce, yellow pine and hemlock. It's all granite a little way under the subsoil; and over the subsoil grows moss. Among these mosses and the roots of the trees almost every important stream in New England takes its rise, and some of them grow to be quite decent rivers. You ladies live in this state, don't you?"

Miss Elting nodded.

"I am afraid we never realized what a beautiful state New Hampshire is until we began looking about a little," answered Harriet Burrell.

"There are too many thtoneth," objected Tommy. "I thhall be afraid of thtubbing my toeth all the time."

"Lift your feet and you won't," suggested Margaret, with a smile.

"Buthter, I didn't athk for your advithe," retorted Tommy.

"There are the foothills," interrupted the guide, "and there is Chocorua. Isn't she a beauty?"

This was the girls' first real glimpse of the White Mountains. Chocorua loomed high in the air, reminding them of pictures they had seen of ancient temples, except that this was higher than any temple they had ever seen pictured. Its gray domes, flanked by the other tops of the neighboring range, stood out clearly defined.

"Three thousand five hundred feet above sea level," the guide informed them, waving a hand toward Chocorua. "Doesn't look that high, does it?"

"Have we got to climb up there?" questioned Margery.

"We are going to. We do not have to if we don't want to," replied Hazel.

"Oh, dear, I'm too tired to go on," whined Margery.

"I knew Buthter could never climb a mountain," observed Tommy, with a hopeless shake of her little tow-head. "But never mind, Buthter, you can thtay here and wait until we come back. It will only be a few weekth and you won't be tho very lonely. Of courthe, you will mith me a great deal."

"Don't worry yourself over me," snapped, Buster. "I can climb as well as you. But if I did stay behind, you can make up your mind I wouldn't miss you."

"Stop squabbling, girls," laughed Harriet. "Neither one of you could get along without the other."

The granite domes soon faded in the waning light. The driver urged on his horses. The carry-all bumped over the uneven road, swaying giddily from side to side, the girls clinging tightly to the sides of the wagon, fearing that they might be thrown out. Darkness shut out pretty much everything at an early hour. Janus decided that they had better wait for supper till they reached the "Shelter," a cabin part way up the side of the mountain, where tourists halted for a rest or to stay over night when intending to climb the mountain. It was not expected that there would be any save themselves there on this occasion.

The road grew so uneven that the driver became a little uneasy. He finally declared that he did not dare to try following the trail up to the Shelter that night; that either he would put them down at the foot of the mountain or make camp there until the following morning, when he would continue the journey up the mountain to the shelter.

Janus consulted with Miss Elting. He said they could walk to the Shelter in a couple of hours, provided the girls were hard enough to stand the climb. The guardian assured him that they were equal to anything in the walking line. It was, therefore, settled that the driver should take them to the foot of the mountain, whence they would make their way on foot to the stopping place for the night, thus beginning their tramp at the base of the mountain.

"How much farther have we to go?" questioned Harriet.

"A mile farther on we pass over a long, covered bridge. The road takes a sharp bend beyond that. The foot of the mountain lies less than a mile from the end of the bridge. We shall soon be there," answered Janus. The girls burst forth into song. Janus had to shout to make himself heard when he spoke to the driver. The horses were traveling at a lively pace. They did not enjoy the disturbance behind them, and their driver, having wrapped the reins about his arms to give him greater purchase, was pulling sturdily, his feet braced against the dashboard of the carry-all.

"Here's the bridge," cried the guide.

A lantern had been lighted and hung from the rear axle of the carry-all. But this did little more than cast weird, flickering shadows ahead. It certainly did not light up the road ahead of there. In the dense darkness the bridge was not visible to the eyes of the Meadow-Brook Girls.

"The bridge ith coming. Low bridge!" piped Tommy.

"Be quiet; I fear we are making the driver's work difficult," warned Miss Elting.

"Oh, but isn't this the fine ride?" cried Crazy Jane. "It's almost like being in my own darlin' automobile with the landscape slipping past on a greased track. Now, what if one of the horses should fall down? Wouldn't we be tumbled into a goose pile!" chuckled Jane.

"Oh, thave me!" cried Tommy.

"Don't suggest anything so awful," begged Margery.

"Oh! What's that!" exclaimed Harriet.

The others did not know to what she referred, but they felt a sudden jolt as the vehicle lurched to the side of the road, then back again.

"What is it?" demanded Hazel.

"The horses have taken fright," answered the guardian calmly. "Be careful that you do not excite them further."

"Are—are the hortheth running away?" stammered Tommy.

"Not yet," reassured Harriet.

"Don't be frightened," called back the guide encouragingly. "Jim can hold any hosses that ever chewed a bit. We'll be on the bridge in a minute; then they can thrash all they want to. Look out!"

There followed a crash, a breaking, splintering sound as the right rear wheel of the carry-all swerved into the side of the covered bridge a few inches from the outer end. The wheel put a hole through the siding of the bridge. It was fortunate for the carry-all that the wheel had not swerved a second earlier. Had it done so, the carry-all must have been wrecked on the stout post at the outer end of the long bridge.

What had so startled the horses none of the occupants of the carry-all knew. The driver knew that they had had a narrow escape from being hurled down an embankment. It was a bad place for horses to take fright. He had managed, however, to pick the team up by the reins and set them down in the middle of the road, where they remained but a few seconds before they were swerving to one side again, then they began leaping and galloping through the long, covered bridge.

Once more a rear wheel raked the boards. The girls cried out, fearing that they would be hurled through the siding and down into the river. They were clinging to the sides of the vehicle, gripping them firmly with their hands.

"Don't lose your presence of mind, girls," cried Miss Elting. "I think the driver has the animals under control now." She was obliged to shout in order to make herself heard.

The roar of the carry-all on the floor of the bridge was terrifying. As the vehicle rolled over the loose planks of the bridge floor the sound was almost as if a Gatling gun were being fired, accompanied by a crash, now and then, as the wagon was hurled against the side of the bridge.

"Oh, what a mess!" shouted Jane McCarthy. "Are we near the other end, or has the miserable old bridge turned around since we started? The horses are now going faster than ever, and we'll be going at the same rapid gait a few moments from now, or maybe seconds——"

Crash!

The carry-all once more struck the side. Then something else occurred. There was a sudden stoppage of the horses, accompanied by the sound of breaking woodwork. It was as if the bridge were collapsing. The Meadow-Brook Girls were piled in a heap at the forward end of the vehicle, then hurled straight over the dashboard and on over the horses, amid shouts and screams. There seemed to be no end to the crashing and screaming for some moments; then a sudden silence settled over the darkened structure, broken only by the frightened neigh of a horse.

"Girls!" It was Miss Elting who called. "Oh, girls, are you hurt?"

"I'm killed. Thave me!" moaned Grace.

"I think I'm alive, but I'm not sure," cried Jane. "I've scraped the skin from my nose entirely. What a mess! what a mess!"

"Wait!" The guardian's voice was commanding. "Margery, Hazel!"

"Ye—es," answered two voices in chorus. They sounded far away.

"Harriet!" There was no reply. She repeated the call, but there was still no answer. Miss Elting became alarmed now. She was still sitting in the broken carry-all, to which she had clung desperately at the sudden stoppage, thus preventing herself from being hurled out, as had occurred to her charges. Thus far not a word had been heard from the two men. Now, a groan somewhere ahead attracted the teacher's attention.

"Girls, don't move! We do not know what has occurred. Does any of you know where Mr. Grubb is?"

"Yeth. He ith right here. I jutht touched hith whithkerth," answered Tommy in a weak, plaintive little voice. "I gueth he ith dead."

The guardian clambered from the rear of the carry-all. The lantern had been extinguished by the shock. She got down, carefully groping about in the blackness for the lantern. She uttered a little exclamation of thanksgiving when her fingers came in contact with it. But the chimney had been shattered by the shock. Only the lower part of it remained, just enough to shield the flame when once this should have been restored. It was but the work of a few seconds to relight the lantern. Miss Elting ran around to the front of the vehicle. She beheld a strange scene.

Both horses were down. At first they appeared to be lying on the floor of the bridge. A closer look showed the guardian that the forelegs of each animal had gone right through the floor. Then the further discovery was made that there was little flooring at this point. The planks that had once formed the floor at this particular spot lay piled on each side of the driveway. Only the beams held the horses from falling through to the water, a few feet below.

A short distance beyond lay Janus Grubb, sprawled on his back; while close beside him, lay the form of the driver. Margery and Hazel were sitting to the right, huddled in each other's arms. Tommy, white-faced, with her feet curled under her, sat close beside Janus, gazing down into his bewhiskered face. Jane McCarthy was leaning against one side of the bridge. Her own face had lost much of its usual color.

"Harriet!" gasped Miss Elting, "what has happened to her?"

Jane shook her head and pointed to the opening in the floor. The guardian understood. Harriet must have been hurled right through and down into the river.

"Girls! Look after the two men. Hurry!" She ran to the opening, then lying down, peered into the darkness. "Ha-r-r-r-i-et!"

"Hoo-e-e-e-e-e!"

The guardian sprang to her feet. It was unmistakably Harriet Burrell who had answered her, but the voice of the Meadow-Brook Girl had sounded far away. Miss Elting believed that the girl had succeeded in reaching the bank of the river. Jane had thrown herself down beside the unconscious guide and was at work making heroic efforts to bring him back to consciousness. The driver already was struggling to get to his feet. Tommy hopped up, and, hurrying to him, gave such assistance as her strength would permit.

The driver staggered; after walking a few steps he leaned against the side of the bridge with both hands pressed to his forehead. Tommy regarded him wonderingly. His head was still dizzy; he had no clear conception of what had occurred.

By this time the guardian had gone to Jane's assistance and was pressing a bottle of smelling salts to the nostrils of Janus Grubb. Janus twisted his head uneasily, as though to get away from the pungent odor of the salts.

"He will be all right in a few moments, I think. I wish we had some water," murmured Miss Elting.

Jane ran to the wagon. She returned with a rope and a pail. Tying the rope to the pail, she lowered the latter through the opening in the floor. A few moments later she presented a pail of water to Miss Elting, which the guardian sprinkled little by little over the face of their guide. Janus gasped, struggled and rolled over. Jane turned him on his back again. This time a solid volume of water was dashed into his face. He turned over and made a feeble attempt to rise. Another volume of water smote him in the back of the neck, hurling him to the bridge floor. This time Janus got to his feet, brushing his eyes, for they were so full of water that he could not see.

"I can let him down at the end of the rope and souse him in the stream," suggested Crazy Jane.

"No, no, no!" protested the guardian. She took Janus firmly by the arm. "Where do you feel bad?"

"I swum! I swum!" mumbled the guide. "I swum!"

"You'd have had to swim if you had gone through the hole in the floor," retorted Crazy Jane. "Harriet went down there, and——"

"Eh? What—wha—at?" gasped the guide, blinking rapidly.

"Sit down a moment," urged Miss Elting. "None of us is seriously hurt. How about you?" gazing at the driver. "No bones broken, I trust?"

The driver shook his head. Janus was gazing at the opening in the floor with a puzzled expression on his face. He stared at the planks banked on each side, nodding understandingly.

"Been fixing the bridge. Forgot to put the planks back in place," he muttered.

"Isn't it rather strange that so important a thing should have been forgotten, Mr. Grubb?" questioned the guardian significantly.

"I swum! I swum!" repeated Janus, running reflective fingers through his beard.

"You haven't thwum yet, but if you thtep into that hole you will have the pleathure of thwimming," warned Tommy, for the guide had been edging closer and closer to the opening in the bridge floor. He drew back a step.

The driver had recovered sufficiently to note the distressing condition of his horses. Now he limped toward them. "They're goners!" he groaned.

"I don't believe it," answered Jane shortly. "They will be, if you don't do something. Why don't you get them out?"

"How can I?" moaned the poor fellow.

Jane started to speak, but a loud "Hoo-e-e-e" from the far end of the bridge caused her to pause. The call was repeated. Then they heard Harriet running toward them.

"Look out for holes in the floor!" yelled Crazy Jane. "You can't tell anything about this perforated old bridge. Come back here, Tommy Thompson!" Tommy had started to run to meet Harriet. Margery grabbed and pulled her back. Tommy jerked away angrily, but this time it was Jane McCarthy who laid a firm grip on the little girl's arm. "You stay right here." Jane lifted her voice in a prolonged call.

Harriet Burrell answered in kind. A moment later Harriet came running up to them, dripping from her unexpected plunge into the river.

"Was any one hurt? Oh, I'm so glad!" as a quick glance told her that all of her companions were there. "Oh, those poor horses!"

"Buthter thought thhe wath killed, but after I told her thhe wath all right, thhe felt better," observed Tommy, with a sidelong glance at Margery.

"Just as though I'd pay any attention to what you say," retorted Margery, her chin in the air. "You talk entirely too much."

"I'm so glad you weren't hurt, Harriet," said Hazel, "but I'm sorry you are so wet."

The water was running in little rivulets from Harriet's clothing. But her interest was centered not on herself but on the two men who were standing by the groaning horses, trying to decide what could be done to get the animals out. Miss Elting slipped an arm about Harriet's waist.

"How thankful I am that you are safe," whispered the guardian, kissing Harriet impulsively.

"The water was very cold," shivered Harriet. "I really didn't know what had happened until I went in all over."

"Were you thrown directly through the opening?" questioned the guardian.

"No. I think I fell on a horse first. I rolled off before I could get hold of anything to stop myself. Then——"

"Then you fell in," finished Tommy.

"Yes, I did, and with unpleasant force. Fortunately, the water was deep and the current not very swift. But it was so dark that I couldn't see which way to swim. I found the direction of the shore by swimming across the current; otherwise I might have gone up or down stream, for I could distinguish nothing. I touched bottom just a little way from where I fell in. Had I struck just a little way to the right I think I should have been killed. You girls are fortunate that you didn't fall through the bridge. Was any of you hurt?"

"Yeth, Jane lotht thome thkin from her nothe, but she can grow thome more, and it will thoon be better again." Tommy's reply drew a smile from her companions, but they were all too much disturbed to feel like indulging in merriment. Besides, there were the suffering horses.

"May I make a suggestion?" asked Harriet, releasing herself from Miss Elting's embrace.

"Somebody will have to make one pretty soon," declared Janus, brushing a sleeve across his forehead. "What is it?"

"I should think that if you were to place the ends of planks under the horses, we might pry them up a little, so that, one by one, you could shove other planks under them. In that way we might get enough planks down to enable the horses to get a foothold."

"Can't be done," answered the driver.

"There will be no harm in trying," urged Harriet.

"It's a good idea," nodded Janus, after having stroked his whiskers reflectively. Janus always consulted his whiskers when in doubt, and among the graying hairs usually found that for which he sought. He was the first to go after a plank. The near horse was the one to feel the support of the plank as the guide worked it under one side of the animal. Janus turned the end of the plank over to Harriet Burrell while he ran for another plank. This was repeated, the driver, after a time, taking part in the operation, until four planks had been worked in under the horse.

"Now, all work together," urged Harriet. "Mr. Grubb, see if you and the driver can't get a couple of planks clear under the horse. If you can get the end of a plank on one of the beams you will have done something really worthwhile."

Miss Elting, Jane, Hazel and Harriet each were assigned to "man" the end of a plank.

"Now, all together! Hee—o—hee!" shouted Janus. A plank slid easily underneath the stomach of the near horse and came to rest on a beam.

"Hooray!" cheered the guide. "That's what comes of having a head on one's shoulders. Young woman, you've got one. Let him down a little. Here, Jim, you get some planks around under that other horse. We'll have them up, but we may break their legs in the final effort. I don't know. Somebody will have to settle for the damage done here to-night."

"The wagon is broken," Margery informed them.

"Never mind the wagon. It's the horses we must save," answered Miss Elting. "We can't leave them to suffer."

Fifteen minutes of hard labor sufficed to raise the horses a little and to place them in greater comfort. The sharp edges of the beams no longer cut into the flesh, and their breathing was less labored. The party paused to rest from their efforts.

"If we had some rope and pulleys we could get the animals out without much difficulty," reflected Janus. "But how to do it now I don't know. I swum! I'm dead-beat."

"Can you lift?" questioned Jane.

"Tolerable."

"Then why not pick up first one fore-foot, then another, and place them on the planks. You'll see what the horses will do then."

Janus scratched his head and fingered his beard.

"I swum, Jim!" he grinned, "let's try it."

Each man took hold of a fore-foot of each horse, and, without much difficulty, raised it to the planks before each animal. They were about to go after the other fore-foot when Tommy, who had been standing back at a safe distance, attracted their attention by uttering a little cry.

"Oh, look! it ith growing light," she exclaimed.

"Daylight? Why, it is getting light," cried Margery.

A faint glow was flickering at the end of the bridge, casting rays through the farther portion of the covered structure. The light was of a reddish tinge. At first, not realizing that the night was still young, the Meadow-Brook Girls welcomed that light with shouts of approval. But there was something strange about the glow that caused Miss Elting, Harriet and the men to gaze in open-mouthed wonder.

As they gazed the glow seemed to grow stronger. Then it flamed into a great glare of red.

"Fire! Fire!" yelled Jane McCarthy.

"The bridge is on fire! Run for your lives!" shouted the guide. "Never mind the horses. Run!"

With one common impulse the girls and their guardian started toward the other end of the bridge, which was not more than twenty feet from them. Margery uttered a scream of terror. Jane grabbed her by one shoulder, giving her a violent shake.

"Don't make things any worse than they are. Tell when you begin to burn, but don't make us think we are burning till the fire gets to us."

"Go on, girls," cried Harriet. "I'm going back to the other end. We must think about saving our packs and our horses." Unheeding their warning shouts, the girl ran back toward where Janus and the driver were still engaged in trying to lift the horses. Miss Elting had followed Harriet, and the two women now implored Janus to hurry with the rescue of the animals.

"It's no use!" he exclaimed angrily. "We can't do it before the fire gets to us. We are likely to lose our packs, too, unless we let these horses go and attend to them."

"Never mind the packs," said Harriet stubbornly, as she laid a firm hand on one of the guide's arms. "We are going to save these poor animals. Let us keep on trying, and I feel sure we can not fail. Now, think hard. What is the quickest and best thing to be done?"

"We'll have to do our own thinking," then said Jane McCarthy, who had come upon the scene at that moment. She glared at the guide and the driver, who stood staring dumbly at Harriet.

"We must save those helpless horses," repeated Harriet, her eyes turning anxiously toward the two patient animals.

"But you girls must not stay here too long," cautioned Miss Elting.

Suddenly Crazy Jane burst forth into a loud hurrah, and, running to the wagon, returned to the driver with a hand-saw. By this time Margery, Tommy and Hazel had come cautiously back to where the horses were.

"Saw the timbers out from under the horses," advised Jane. "It may hurt them to drop into the river, but it's better for them to drown than to be burned alive! Move quickly, now!"

"Janus," muttered the driver, "we're a pair of mutton-heads!"

"We are," agreed the guide, as he ran to get the other saw.

The rasping of the saws began instantly, the Meadow-Brook Girls moving closer to observe the work, casting frequent apprehensive glances over their shoulders at the thick cloud of smoke which issued from the farther end of the bridge. The fire did not appear to be making much headway, still it did not seem to be abating. Already the framework of that end of the bridge was outlined like the figure in a set piece of fireworks. They could hear the crackling of the flames, and the wooden tunnel was becoming filled with smoke. Tommy was coughing, to remind her companions that they were in need of other quarters.

"I don't think I would cut the ends off," suggested Harriet. "Saw them nearly through, then cut the opposite ends. Otherwise you may leave the animals dangling in the air with no means of helping them out."

Janus nodded approvingly at Harriet's suggestion.

"I reckon you're right," he agreed. "Jim, tackle the other end. We'll let this near horse down first and see how he makes out. If it works, we'll drop the other fellow in the same way."

A warning snapping sound was heard.

"Stand clear!" bellowed Janus.

The girls sprang back, and just in time. Pieces of plank shot up into the air, one striking the bridge roof with a crash. Then the near horse, with a neigh of fear, disappeared into the black water below them. They heard a loud splash. Harriet, leaning over, peered into the river.

"He's swimming. I can hear him," she cried joyously. "Isn't that fine that you thought of that, Mr. Grubb?" she exclaimed, turning a flushed face to the guide.

"Huh! Thought of it? I'd never thought of it if I'd kept my thinking machine going for a hundred years. Now the other horse, Jim. We'll have to step lively. Them flames is getting too nigh for comfort. Now you folks had better get out of here!" he commanded.

"Not yet," smiled Harriet, "we still have work to do. We must get the things out of the wagon. If we lose them, we shall be in a fix."

"Mercy! I hadn't thought of that," cried the guardian. "But shall we have time to carry them across?"

"The men will have to carry the heavier articles. I think we shall be able to manage it. Come, help me get the things out of the carry-all."

Harriet ran to the wagon, followed closely by Miss Elting and Margery. Tommy alone held back. Hazel and Jane also hurried forward to assist.

"All those who wish their suppers will have to work," cried Harriet Burrell.

"We need a fire company more than thupper jutht now," retorted Tommy Thompson. "If we had a fire engine we could make thith fire look thick."

Harriet was in the carry-all passing out bundles and packs. She dropped a sack of cooking utensils to the floor of the bridge with a great clatter.

"Carry them to land," she directed Tommy and Hazel.

"There goes the other horse," cried Miss Elting, as a crash and a great splash for the moment cut short their conversation. Janus uttered a yell of triumph.

"We got 'em both free!" he shouted.

"That's what," agreed Jim. "We'll pull the carry-all ashore next."

"I am afraid we won't have time. The fire is almost too near for comfort now," said Harriet. Then she darted back to the carry-all to secure a blanket that she recalled had been laid over the back of the front seat of the vehicle, and which had been forgotten when removing the other things. Reaching the wagon, she decided to take the cushions also. Then Harriet made a final search of the wagon to be sure that nothing of value had been left. The carry-all had been well stripped.

The girl sprang out, casting a quick glance overhead, when she discovered, to her dismay, that the flames were already at work, they having rapidly eaten their way along the ridge of the bridge.

"Gracious! I must get out of here and without a moment's loss of time," she cried.

"Hurry!" bellowed the voice of the guide. "We haven't time to save the carry-all. Get out from under. The bridge is going to fall."

As Harriet made a dash toward safety the burned end of the bridge fell. There was a rending noise as the weakened girders gave way under the weight of the bridge. A shower of sparks and flame shot into the air.

Miss Elting, Jane and the two men stood on shore, shouting with all their might to Harriet Burrell. But Harriet did not hear their warning shouts, nor had she need of warning. She knew only too well what was occurring. Suddenly the long bridge caved in and went down well past the middle with a tremendous crashing and snapping and roaring, sparks and flames shooting still higher than before, the burning timbers hissing and sending up a great cloud of steam as they fell into the river.

Miss Elting, grown dizzy at thought of Harriet, had stumbled and fallen. Jane McCarthy quickly raised and dragged the guardian away.

"Harriet!" shouted Miss Elting.

The frightened girls took up the cry, but there was no answer. Harriet had gone down with the burning bridge.

Miss Elting and Jane McCarthy had climbed down the embankment, and, standing at the river's edge, scanned the water with pale faces and anxious eyes. Dark shapes drifted past them, shapes that caused them to start apprehensively as they caught sight of them.

Nearly all of the bridge that had been on fire was now in the water. The structure had broken off short, taking most of the fire with it into the river. The broken end, still in the air, glowed here and there, the glowing spots fading and dying out one by one. Of this the two women saw nothing. They were heavy with anxiety. It did not seem to them possible that Harriet Burrell could have escaped alive. Janus and Jim, who had run to the river bank, were now plunging here and there, stumbling, groping, wading or swimming about in the river to have a look at some bit of wreckage that resembled a human form. They believed that Harriet had been swept down to her death with the burning bridge.

All at once Jane raised her voice in the cry of the Meadow-Brook Girls. "Hoo-e-e-e!" she called shrilly. But no answering cry from the missing girl relieved their suspense.

"I'm afraid we can do no more," said Miss Elting with a catch in her voice. "Oh, why did I leave her? Why did I not insist on Harriet's leaving that awful place with me?"

"You couldn't help it," soothed Jane. "But you mark me, Miss Elting, Harriet is alive and sound, just like the rest of us. You leave it to Harriet Burrell to take care of herself. I tell you it's all right. Hoo-e-e-e-e!"

"Don't! Oh, don't!" begged the guardian.

"Why not? She'll hear me and she'll know which way to go when she comes up from the water," answered Crazy Jane breezily. She was putting on a brave show of cheerfulness, and somehow this cheerfulness began to take hold of Miss Elting. Her shattered hopes began to rise; she began to take courage even against her better judgment, which told her that Harriet could not possibly have escaped. Even granting that she had, they would have seen or heard from her before this.

Janus stood dripping beside them.

"Now, you ladies go back. I'll do all the looking that's necessary. Candidly, I don't think Miss Harriet escaped. She was caught when the old bridge fell down, but I'll keep on looking for her. I'll keep right on looking all the rest of the night."

Jane led Miss Elting up the bank despite the protests of the guardian that she did not wish to go, but preferred to remain where she was.

"We can do nothing here," urged Jane, more gently now. It was all that she could do to keep from breaking down and crying, but she knew she must keep up her courage. Besides, she was still hoping, at times almost believing, that they would find Harriet Burrell awaiting them on shore.

"Didn't you find her?" cried Hazel. They had climbed the steep bank and returned to the girls.

Neither woman answered.

Margery burst forth into a loud wail. Tommy and Hazel stood in blank, rigid silence. They could not believe that Harriet was gone. Miss Elting sank down on a pack, while Jane stood gazing moodily off over the sluggish river.

Janus came in a few moments behind the guardian and Jane, his arms hanging limply at his sides, his chin lowered almost to his chest.

"I'm afraid it isn't any use to look further," he said. The little party scarcely heard the guide. Jim had gone on up the bank. They could hear him whistling and chirping to the missing horses to call them to him. Then they caught the sound of a whinny and a moment later another. The animals had heard and recognized their master. Jim captured and haltered them with the ropes that he had brought from the carry-all for the purpose. He then led the animals off to one side, where he secured them to trees. The driver then walked slowly along the bank to join the others of the party.

Suddenly Jane McCarthy cried out sharply, "Who's that?"

A series of little splashes had been heard out in the river; then, out of the gloom, grew the dim outlines of a moving figure.

"Who is it?" cried Miss Elting, scarcely daring to trust her voice.

"It is I. What is all the excitement about?" called a familiar voice.

"Harriet!"

A chorus of screams greeted Miss Elting's cry. Four girls and their guardian, regardless of the wetting they were receiving, rushed helter-skelter into the river, throwing themselves upon the staggering Harriet. They snatched her up, carrying her ashore despite her struggles and protests. They laid her down on the packs, each trying to do something for their companion whom they had believed to be lost.

"For goodness' sake! what is the matter?" demanded Harriet, sitting up.

"Lie still, dear," urged Miss Elting. "You will be all right in a few moments."

"All right? There is nothing the matter with me, except that I'm wet and cold." Harriet got up and shook herself, gazing anxiously at her companions. "What is it, girls? Tell me!"

"Oh, Harriet, don't you know?" breathed Hazel.

"No, I don't. You are all here, aren't you?" she demanded, with a quick glance about her.

"Yes, now we are," nodded the guardian. "Don't you understand? We thought you had gone down with the bridge."

"Well, I did go down, but not with the bridge. What of it?"

"We thought you were dead," continued Miss Elting, her voice shaking.

Harriet looked from one to the other of her friends. "Why, you poor dears, no wonder you looked so woe-begone. Now that it is all over, I don't blame you for thinking so."

"Well, I swum!" muttered Janus, combing out his whiskers with the spread fingers of his right hand.

"So did I," laughed Harriet. "That's why I'm here."

"Tell us how you escaped. Can't you see, we are hardly able to believe that it is really you?" was Miss Elting's excited reply.

"It's myself, and no other, as Jane would say. After you had left me I ran back to the wagon to get the blanket and cushions we had left there. I knew the fire was near me, but I thought I had time enough to get away from it. Suddenly I felt the bridge giving way. I was close to the opening into which the horses fell when things began to happen, and I made a long, desperate dive into the river, hoping to get out from under the bridge before it fell on me. I remember seeing a great shower of sparks falling around me as I shot through the air. I wondered if it were the bridge that was falling with me. Then I struck the water. I swam under the water with the current as fast as I could, then when I thought I had gone far enough, to make it safe to rise, I did so. I don't recall what happened after that. I must have been hit by something, or else bumped into a timber when I rose to the surface. It is a wonder I wasn't drowned. When I came to my senses I was slowly drifting down stream, clinging to a piece of charred plank. I know it was charred because I could smell it. You know how wet, burnt wood smells? This piece of plank smelled that way."

"Nithe, appetizing odor," nodded Tommy. "Yeth? Go on."

"I did not know where I was, but I knew I was drifting downstream. I kicked until I had headed the plank at right angles to the shore, and remained on the plank until my feet touched bottom; then I got up and began plodding along upstream, knowing that, sooner or later, I should find some of you folks. I heard someone call. Was it you, Jane?"

"It was myself and no other," replied Jane

"I thought it was you. I was out of breath, so I didn't try to make you hear me."

"Well, I swum!" ejaculated Grubb under his breath. "I never expected to see her again."

"What of the horses?"

"Got 'em," answered the driver tersely, "Carry-all gone to the everlasting bow-wows. What now?"

"If the ladies want to go on, we will load the stuff onto the horses and tote them that way to the place I had already picked out for a camp."

"How far is it?" questioned Miss Elting.

"Oh, a mile farther on, I should say."

"I fear it would not be wise to go on just now. I think it would be better for us to make temporary camp somewhere hereabouts. We are completely exhausted. Harriet must have a change of clothing and we all need something warm to drink and eat. Do you know of a good place to make camp for a little while?"

"Back about a quarter of a mile is a grove. There's a creek running through it. That will be a good camping place."

"Please have the driver assist you in getting the equipment there. Don't lose any time. Harriet, are you cold?"

Harriet shook her head. "I'm going to help carry the stuff to our camp. Then I shall be sure of keeping warm. Come on, girls. Where are the bedding packs?"

"Down there by the tree, Miss," replied Jim.

Harriet ran to the tree. "I don't find them," she called a moment later.

Jim harried to her. He was mystified to discover that the packs were not where he had left them.

"You didn't throw them in the river, did you, Jim?" questioned Harriet.

He declared vehemently that he had not; that he had placed them well back from the water, and that they could not possibly have rolled into the river. Jim announced that he was going down the shore to look for them, just the same. This he did, starting away at a trot. Wonderingly, and somewhat disturbed, for the bedding and the clothing packs contained articles that could not be done without, the girls instituted a search of their own, but found nothing. The loss of the packs meant their return to town to purchase more supplies. No one wished to do that, in the first place; and, in the second place, they needed warm, dry bedding and dry clothing for use that night.

While Jim was in search of the missing equipment the girls went to work and collected the scattered contents of some of the packs. Suddenly there came a long-drawn shout from down shore.

"I've got 'em!"

"I thought so," nodded Miss Elting.

Jim came back lugging a pack soon thereafter. The water was running from the pack, under whose weight the driver was staggering.

"Found them in the river," he explained. "Had drifted into a cove. So heavy I couldn't carry more than one at a time. The other packs are open and the stuff spread all over the cove. I gathered it up as well as I could. You'll have to give me a rope to tie the things up, or else bring them back in wads."

"In the river?" cried the girls in chorus.

"Well, I swum!" muttered Janus, pausing from his labors long enough to consult his whiskers. "Things are moving kind of fast."

"Oh, this is nothing, nothing at all," laughed Crazy Jane. "You will think things are moving after you have been out with the Meadow-Brook Girls for a time. Things always do move when we are around. Look out that they don't move so fast as to sweep you with them. My! but this is a heavy pack."

The girls had taken the wet pack from Jim and were dragging it up the bluff. Janus tied this and two other packs on the back of one horse, then began making ready for doing the game with the other animal. By the time he was ready, Jim had returned with still another wet bundle of equipment.

"Our clotheth are in that pack!" wailed Tommy, as she surveyed the bedraggled outfit. "What thhall we do?"

"Keep quiet and go on up to camp," said Margery severely.

"Come, come, girls!" urged Miss Elting, a little irritated. She had not yet quite recovered from the shock of Harriet's disaster. How great a shock this had been her charges had not fully realized.

The heaviest packs were soon loaded on the horses, after which Janus, leading one animal, went ahead to pilot them to the spot chosen for a temporary camp. Nearly half an hour was consumed in finding their way there. The night was dark and many obstacles in the shape of rocks and fallen trees and stumps were found in their path, and the guide's call that they had arrived was the most welcome information the girls had received in all that eventful day's journey.

"Here, Jim, unload these packs while I gather the wood for a fire, so that we can see what we are doing."

"Fire!" scoffed Jim. "Little fire you will see to-night, unless you have some matches. I haven't any. It was a bad job when I took this contract."

"Never mind expressing opinions. I'm responsible for making a fire, and nobody is responsible for what's happened to us on the way out here. It is just one of those unforeseen disturbances that come to the best regulated families," said Janus testily.

"I think I can find some wood for the fire," suggested Harriet. "I just stumbled over a dry stick. Here it is. Is there any birch bark here, Mr. Grubb?"

"No, but I'll fire some leaves. I've got plenty of matches," he confided to Harriet. "I didn't tell Jim. It isn't necessary for these fellows to know too much, you know."

"Just between ourselves," chuckled Harriet under her breath.

"Sure. I've got a daughter just your age, and she's almost as good a campaigner as you are, though I reckon this night's doings would have been too much for her. You don't find many such as you and your outfit." Having expressed his opinion, Janus proceeded to his work, and a moment later had a quantity of dry leaves ablaze.

"Now fetch on your wood. Who says Jan Grubb can't build a fire when there isn't anything to build with?" he boasted. "Easy. Not so much at a time. You'll press it down to the ground so the draft can't get under it, and then your nice little fire will go out. We'll build a roarer, then we can start a smaller one for cooking."

"I won't be sorry to eat a square meal," chuckled Jane.

"Nor I," agreed Margery, "I haven't eaten a square meal for ages."

"Be careful, girls. Don't stand so close to the fire. You will burn your skirts," warned Miss Elting. "You will have holes in them almost before you realize it."

Harriet had left that fire and was laying another. She called to Jane to get the supper things ready for cooking.

"Margery, you and Hazel set the table. If you can't find a dry blanket, simply clear away a place on the ground. We shan't be so particular about our table this evening."

"What about it? Do we stay here all night, or are we to go on?" asked the guide.

"I think we had better make camp for the night," decided Miss Elting.

"I reckon it would be a good idea. I'll make a line and dry out the stuff. It's pretty wet," decided the guide.

Janus drove some stakes that he had cut down. Then, stringing a rope between them, the two proceeded to hang up the wet bedding, which consisted solely of soft, gray army blankets. He took the wet clothing of the girls from the packs, hanging this on the line also, and a few moments later the blankets and the garments were steaming. So was the coffee pot. Bacon was the only other food put over for cooking. The travelers were too hungry to care to wait long for their supper.

It was not long after Harriet and Jane had begun cooking the bacon before they sounded the supper call. No one was late for supper that night, and each sat down tired and travel-stained, but there was not a word of complaint from either men or girls. They made merry over the meal, made light of their misfortunes, and altogether enjoyed themselves fully as well as if their circumstances had been different.

"What I should like to know is how those things got in the river?" demanded Janus as the meal neared a close.

For a moment no one spoke. The guide's question was one which no member of the little party was prepared to answer. So many unpleasant events had occurred in such rapid succession that it was difficult to place the cause of this latest disaster.

"Will you tell me where you placed the first packs when you came ashore with them?" asked Harriet, turning to the driver.

"Right against the rocks."

"And behind that large boulder?"

"Yes. How did you know?"

"Oh, I saw where you threw the first pack down. It left the mark of the rope in the soft dirt," explained the girl. "I am not gifted with second sight, but I did see that. What I started to say was that I know how the packs got in the river."

"You know?" asked Miss Elting.

"Yes. They were thrown in."

For a few impressive seconds no one spoke. Janus combed his whiskers with the fingers of one hand. Jim, the driver, sprang to his feet, his face crimson with anger.

"I won't stand for that. Why should I throw the old stuff in the river?" he demanded indignantly.

"I beg your pardon. I did not accuse you of it," said Harriet. "I know you did not. It was some other person who threw the packs into the river."

They gazed at her in amazement.

"Harriet, what do you mean?" cried the guardian.

"If she had lived up here two hundred years ago or so the people would have tied her to a stake and set fire to her," declared Janus, punctuating his declaration with a series of quick, emphatic nods.

"The driver placed the pack behind the boulder and against the rocks," said Harriet. "Surely, he knew where he left the things. What is more, I looked while he had gone in search of them, and, as I've already said, saw where he had left the pack. The rest was easy to understand. The packs could not possibly have got into the river unless they had been thrown there."

"But who——" began Jim.

"I don't know. That it was none of our party goes without saying. Perhaps Mr. Grubb can tell us. Who do you think it could have been, sir?" she asked, turning to the guide.

"I swum! I swum!" muttered the guide.

"It isn't possible!" exploded Jim.

"I reckon Miss—Miss Burrell is right, Jim," agreed the guide. "Either you threw the stuff in, or somebody else did, and we know you didn't, so what's the answer? The young lady has given us the answer, and there you are."

"I'm sorry," pondered Miss Elting. "I was in hopes this journey would be free from unpleasantness, but here we are meeting with difficulties at the very start of it. Have you any enemies who would wish to do you harm, Mr. Grubb?"

"No, no, no! Nothing like that, Miss."

"Do you know a man named Collins?"

"Collins? Never heard of him. Who is he?"

"I don't know. I will tell you something that you do not know, either. The night we arrived at Compton a man called on me at the hotel to ask me to discharge you and let him act as our guide instead. He said he needed the money. He also said we would be sorry for having taken you as our guide; that we would get into no end of trouble were we to go with you. He intimated a great deal more than he put into words. It was plain that he disliked you very much. He made a distinctly unfavorable impression upon me. Harriet saw him, too, just as he was taking his leave."

"Well, I swum!" Janus was tugging nervously at his whiskers. There were beads of perspiration on his forehead. His lips moved rapidly, but he uttered no further words for some moments.