This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Everychild

A Story Which The Old May Interpret to the Young and Which the Young May Interpret to the Old

Author: Louis Dodge

Release Date: January 16, 2006 [eBook #17521]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EVERYCHILD***

ARGUMENT:—Everychild encounters the giant Fear and sets forth on a strange journey.

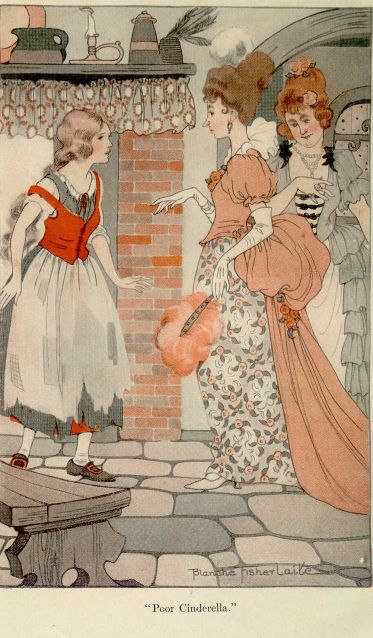

ARGUMENT:—Everychild pities the sorrow of Cinderella and rejoices in her release from bondage; he encounters a dog that looks upon him with favor.

ARGUMENT:—Every child views with amazement a famous dwelling-place, and is grieved by the plight of an unfortunate prince.

ARGUMENT:—Everychild's feet are drawn to the spot where the sleeping beauty in the wood lies. Time passes.

| XX. | A SONG IN A GARDEN |

| XXI. | AN ENCOUNTER IN THE ATTIC |

| XXII. | THE END OF A HUNDRED YEARS |

| XXIII. | THE AWAKENING |

| XXIV. | TIME PASSES |

ARGUMENT:—On his wanderings Everychild bethinks him of his parents, and discovers that though he has seemed to lose them, he has not really done so.

| XXV. | WILL O'DREAMS REPORTS A DISCOVERY |

| XXVI. | THE HIDDEN TEMPLE |

| XXVII. | HOW EVIL DAYS CAME UPON THE CASTLE |

| XXVIII. | THE MOUNTAIN OF REALITY |

| XXIX. | THE MASKED LADY'S SECRET |

| XXX. | WILL O'DREAMS MAKES A DISCOVERY |

| XXXI. | HOW ALADDIN MADE A WISH |

| XXXII. | THE HALL OF PARENTS |

It did not seem a very pleasant room. To be sure, there were a great many nice things in it. There was rose-colored paper on the wall, and the woodwork was of ivory, with gilt lines. There were pictures of ships on the ocean and of high trees and of the sun going down behind a hill, and there was one of an old mill with nobody at all in sight. And there was one picture with dogs in it.

There was a soft rug, also of rose-color, and a fine clock, shaped like a state capitol, on the mantel. There was a silver gong in the clock which made beautiful music. There was a nice reading table with books on it, and a lamp. The lamp had a shade made up of queerly-shaped bits of material like onyx, and a fringe of rose-colored beads. Yet for all this, it did not seem a pleasant room. You could feel that something was wrong. You know, there are always so many things in a room which you cannot see.

A lady and a gentleman sat at the reading-table, one on either side. It seemed they hadn't a word to say to each other. They did not even look at each other. The lady turned the pages of a magazine without seeing a single thing. The gentleman sat staring straight before him, and after a long time he stretched himself and said: "Ho—hum!" And then he began to frown and to stare at an oak chair over against the wall.

You might have supposed he had a grudge against the chair; and it seemed that the chair might be crying out to him in its own language: "I am not merely a chair. Look at me! I was a limb on a mighty oak. I was a child of the sun and the rain and the earth. I used to sing and dance. Oh, do not look at me like that!" But the gentleman knew nothing of all this.

Both the lady and the gentleman were thinking of nothing but themselves and they continued to do this even when a door opened and their son entered the room.

Their son's name was Everychild; and because he is to be the most important person in this story I should like to tell you as much about him as I can. But really, there is very little I can tell. His mother often said that he was a peculiar child. It was almost impossible to tell what his thoughts were, or his dreams, or how much he loved this person or that, or what he desired most.

It was difficult for him to get into the room. He was carrying something which he could not manage very well. But no one offered to help him. Presently he had got quite into the room, leaving the door open.

The thing he carried was a kite, and he was holding it high to keep it free of the ground. The tail had got caught in the string and there was a rent in the blue paper.

The clock struck just as he entered and he stopped to count the strokes. Seven. The last stroke died away with a quivering sound. Then with faltering feet he approached his father.

His father was frowning. He stopped and pondered. He had seen that frown on his father's face many times before, and it had always puzzled him. Sometimes it would come while you watched, and you couldn't think what made it come. Or it would go away in the strangest manner, without anything having happened at all. It was a great mystery.

The frown did not go away this time; and presently Everychild approached his father timidly. It was rather difficult for him to speak; but he managed to say:

"Daddy, do you think you could fix it for me?" He brought the torn kite further forward and held it higher.

His father did not look at him at all!

Everychild's heart pounded loudly. How could one go on speaking to a person who would not even look? Yet he persisted. "Could you?" he repeated.

His father moved a little, but still he did not look at Everychild. He said rather impatiently: "Never mind now, son."

Then his mother spoke. She had glanced up from her magazine. "You've left the door open, Everychild," she said.

Everychild put his kite down with care. He returned to the door. It was a stubborn door. He pulled at it once and again. It closed with a bang.

"Everychild!" exclaimed his mother. The noise had made her jump a little.

"It always bangs when you close it," said Everychild.

"It wouldn't bang if you didn't open it," said his mother.

He returned and stood beside his father.

"You know you used to fix things for me," he said. He reflected and brightened a little. "And play with me," he added. "Don't you remember?"

But just then it seemed that his father and mother thought of something to say to each other. Their manner was quite unpleasant. They talked without waiting for each other to get through, and Everychild could not understand a thing they were saying. He withdrew a little and waited.

But when his parents had talked a little while, rather loudly, his father got up and went out. He put his hat on, pulling it down over his eyes. And he banged the door. But it was the outside door this time, which never banged at all if you were careful.

And then his mother got up and went to her own room—which meant that she mustn't be disturbed.

Everychild stood for a moment, puzzled; and then he thought of the broken kite in his hands. He plucked at it slowly. You would have supposed that he did not care greatly, now, whether the kite got mended or not. But little by little he became interested in the kite. He sat down on the floor and began to untangle the tail.

He scarcely knew when the inner door opened and the cook entered the room.

She was a large, plain person. Her face was redder than Everychild's mother's face, but not so pretty. Her eyes often seemed tired, but never too tired to beam a little.

"Are you all alone, Everychild?" she asked. She did not wait for a reply, but asked another question: "Is something wrong with your kite?" And again without waiting for a reply she added: "Maybe I could fix it for you!"

And she got down on the rug on her knees and took the kite from his hands.

Everychild, standing beside her, looked into her rather sad, kind eyes, which were closer to him than he remembered their ever having been before. There were little moist lines about them, and they were faded. Her hands were not at all like his mother's hands. Not nearly so nice: and yet how clever they were! She was really untangling the tail of the kite, moving it here and there with large gestures.

And then Everychild forgot all about the kite. Certain amazing things had begun to happen near by.

It had been getting dark in the room; and now it suddenly became quite bright, though no one had turned the lights on. And there was a sound of music—a short bit of a march, which ended all of a sudden. And then Everychild realized that by some strange process two persons had entered the room.

He was almost afraid to look at the two strange persons, because their being there seemed very mysterious, and he had the thought that if he looked at them steadily they might vanish. He knew at once that they were not to be treated just as if they were ordinary persons. It was not only that they had come into the room without making any noise, or that there had been that burst of music, or that the light had brightened.

It was rather because the cook went on untangling the kite, just as if nothing had happened.

He said to himself, "She does not know they are here. She does not know I have seen anything."

Then it occurred to him that the two strangers were not paying any attention to him at all, and that he might look at them as much as he pleased.

Suddenly he recognized one of them. He had seen his picture. It was Father Time. And he could have laughed to himself because Father Time was a much more pleasing person than he had been in his picture. It is true that he carried a scythe, just as he had been pictured as doing. There was a sand-glass too. It was in two parts, connected by a narrow stem through which the sand was running from one part to the other.

But he did not have a long white beard, and a dark robe, and a stern face. Not at all. His eyes were all ready to twinkle. They were the kindest eyes Everychild had ever seen. You could tell by looking at them that if you were to hurt yourself Father Time would pity you and comfort you. He had a rather jolly figure. You could imagine he might be very playful. And he wore the costume of a jester—though you did not feel like laughing at him, because his eyes were so friendly and kind. He stood as if he were waiting to begin some sort of play.

Then Everychild looked at the other stranger. She was a lady, and very distinguished looking. He did not recognize her, though he felt at once that she was a very important person. She was dressed all in shimmering white. She was very fair and her hair was dressed beautifully. She wore a band about her hair and there was a jewel in it, like a star. She wore a little mask over her eyes so that you could not be sure at once whether she was a kind person or not. She sat at a spinning wheel, and the wheel went round and round without making any noise. She was spinning something. She looked very tranquil.

Everychild was becoming greatly excited. He touched the cook on the hand. "Didn't it seem to you to get much lighter?" he asked.

"Lighter? No. It's getting darker," she replied.

"And—and didn't you hear any music, either?"

"I heard nothing."

It made him feel almost forlorn to have the cook say she had not noticed anything. He drew closer to her. "Never mind the kite now," he said. "I want you … Oh, don't you see anything at all? Please look!" He stood with one finger on his lip, staring at Father Time and the Masked Lady.

She regarded him almost with alarm. "Lord bless the child, what's coming over him?" she exclaimed. "There's nothing there!" She followed the direction of his eyes, and then she looked at him with an indulgent smile. "There, put your kite away," she said. "It's all right now except for that rent in it. I'll mend that to-morrow. And try to be a good boy. You mustn't be fanciful, you know!"

She patted him on the back and then she left the room.

He stood quite forlorn, watching her depart. Then with nervous haste he made as if to follow her. But at the door, which she had closed, he stopped. You could tell that he was making up his mind to do something. Then he turned slowly so that he faced Father Time and the Masked Lady. Presently he took a step in their direction. And at length, with a very great effort, he spoke.

"Please—tell me who you are!" he said.

It was Father Time who replied. He replied in a voice which was quite thrilling, though not at all terrifying:

"We are the true friends of Everychild!"

Everychild brought his hands together in perplexity. "Friends?" he said. "I—I think I never saw you before. I may have seen your picture. Yours, I mean. Not the—the lady's. And I'm not sure I know your right name. If you'd tell me, and if—if the lady would take her mask off——"

But Father Time interrupted him. In a solemn voice he said, "Everychild, I have come to bid you leave all that has been closest to you and set forth upon a strange journey."

At this Everychild was deeply awed. Perhaps he was a little frightened. "All that has been closest?" he repeated. "My mother and father—it is they who have always been closest."

"Everychild must bid farewell to father and mother," declared Father Time.

And now Everychild was indeed dismayed. "Bid farewell to them?" he echoed. "Oh, please … and shall I never see them again?" He wished very much to approach Father Time and plead with him; but Father Time held up an arresting hand and spoke again, almost as if he were a minister in church.

"It is not given to Everychild to know what the future holds," he said. And then he again made a polite gesture toward the Masked Lady. "Only she can tell what the end of the journey shall be," he said.

It was now that Everychild looked earnestly at the Masked Lady. If she would only take her mask off! With a great effort he asked—"And she—will she befriend me when I have gone from my father and mother?"

With the deepest assurance Father Time replied, "Give her your affection and she will befriend you in every hour of loss and pain, clear to the end of your journey—and beyond."

"But," said Everychild, "she—she doesn't look very—she looks rather—rather fearful, doesn't she?"

"She is beautiful only to those who love her," said Father Time.

This seemed reassuring; and now Everychild ventured to address the Masked Lady directly. "And—and will you go with me?" he asked timidly.

She replied with great earnestness: "Everychild, go where you will, you have only to desire me greatly and I shall be with you."

Then it seemed to Everychild that it would not be a very terrible thing to go away, after all.

It was plain that Father Time and the Masked Lady were waiting for him to go; and so without any more ado he boldly approached the door which opened out upon the street. But his heart failed him again. He drew back from the door and cried out—"No, no! I cannot. I cannot go out that way. Is there no other way for me to go?"

It seemed to him that his heart must cease to beat when Father Time exclaimed in a loud voice—

"Go, Everychild!"

Still he hung back. "But not that way!" he repeated. "The wide world lies that way, and I should be afraid."

"I know," said Father Time, "that the Giant Fear lives outside that door. But him you shall slay, and then the way will be clear."

"I shall slay him?" exclaimed Everychild wonderingly. "How shall I slay him?"

"Do not doubt, and a way shall be found."

It was just at this moment that something very terrifying occurred. There was a stealthy step outside the door—the sort of step you hear when it is dark and you are alone. And Everychild could not help shrinking back as he stood with his fascinated eyes held on the door. He was staring at the door, yet he knew that the Masked Lady and Father Time were listening to that stealthy step too. The Masked Lady had put aside her spinning wheel, and Father Time had become very grave.

There was a brief interval of suspense and then the door began to open, inch by inch, very slowly. Two terrible eyes became visible.

Everychild knew immediately that it was the Giant Fear, though for a moment he could see nothing but the peeping eyes which leered horribly. And when the Giant Fear perceived that Everychild was terrified, he thrust the door open wide and stood on the threshold.

He was, I may tell you at once, the most hideous creature in the world. His cruel grin was too evil a thing to be described. He carried a great bludgeon. From his lower jaw a yellow tusk arose at either corner of his mouth and projected beyond his upper lip. His ears covered the whole sides of his head. His jaws were as large around as a bushel basket.

At first, after he had entered the room, he did not perceive either Father Time or the Masked Lady. He dropped one end of his bludgeon to the floor with a thump, and there he stood leering at Everychild with a sinister and triumphant expression.

Only a moment he stood, and then he advanced a step toward Everychild. But just at that instant Father Time moved slightly and the intruder became aware of his presence. The wicked smile on his terrible face began to freeze slowly. The great creature shrank away from Father Time; and as he did so he became aware of the presence of the Masked Lady on his other side. For an instant he trembled from head to foot! And then more hurriedly he took another step toward Everychild.

Everychild was trying very hard to hold his ground; but in truth he could feel his knees giving way beneath him and it seemed that he must fall if the giant advanced another inch. Nor did the giant fail to note that Everychild was in distress, and at this he regained something of his boldness. In a loud, terrible voice he spoke to Everychild:

"Ah—ha! And so you were getting ready to defy me—hey?"

Everychild's teeth chattered as he replied: "Please go away!"

The giant nodded exultantly. In the same great voice he said, "You know me, I suppose?—the Giant Fear who always makes Everychild tremble?"

A calm voice interposed—the voice of Father Time: "The Giant Fear, whom Everychild may conquer!"

The voice was so reassuring, and the eyes of Father Time were so calm and friendly, that Everychild ceased to despair. With trembling limbs he ran to Father Time. "If you would lend me your scythe——" he gasped. He laid a hand on the scythe of Father Time.

But Father Time withheld the scythe. He said gently, "The scythe of Father Time is a wonderful weapon; but a better one is at Everychild's command. Behold!"

As he spoke he pointed majestically to the Masked Lady.

She had arisen, and Everychild saw that she held aloft a slim, shining sword!

A hush fell within the room; but presently Everychild, addressing Father Time, whispered: "A sword! And may I take it?"

With a very firm voice Father Time replied: "You may, and with it you shall prevail!"

Oddly enough, Everychild forgot for the moment that he was in peril. He drew near to the Masked Lady, and he could see that she was smiling. She placed the sword in his hand.

At first he held it awkwardly, yet he looked at it with shining eyes. Then he turned about, holding the sword forward, as the Masked Lady had held it. He could feel that the hilt of the sword was beginning to fit snugly into his hand.

Gradually a strange transformation occurred. His body straightened, his eyes shone more than ever. He took a step forward, and he knew that his knees were no longer trembling. In a clear voice he cried out to the Giant Fear:

"Defend yourself!"

But the giant reeled and trembled. He tried to hold his bludgeon aloft, but his hands shook so that it nearly fell. He became as pale as death, and it was quite impossible for him to meet Everychild's eye. He retreated with stumbling steps. It seemed that he would fall. His power had deserted him.

He made a last, terrible effort to lift his bludgeon; but Everychild darted forward with the speed of lightning, holding his sword before him. It was a very sharp sword, and it pierced the giant's body as easily as if the great creature had been made of paper.

The Giant Fear tottered. His bludgeon slipped from his grasp and his eyes became dim. He fell with a crash. He was dead!

At that very moment a sound of distant music could be heard. It was all very wonderful. The music drew nearer; it sounded more loudly.

Everychild turned and restored the slim sword to the Masked Lady.

"Do you not wish to keep it?" she asked.

But it seemed to Everychild that he had no need of the sword, now that the Giant Fear was dead. "Thank you, I shall not need it again," he said.

She said, in a strange, sad voice, "Alas, the greatest need of my sword arises after fear is gone!"

But he scarcely heeded her now. The sound of music was heard much nearer. He lifted his eyes and beheld the door which had always stood between him and the world. He drew nearer to the door. It was wide open.

He heard the voice of Father Time: "The moment has arrived for you to go, Everychild!"

He caught step with the music, which was very loud now.

He marched valiantly away.

He knew he could go wherever he pleased, and so with very little delay he entered a deep forest. It was evening and the wind was sighing in the great trees. A winding road stretched before him like a gray ribbon.

Soon he came to where a boy sat by the side of the road. The boy sat on a small Oriental rug, and by his side stood a very peculiar lamp. The boy was clad in a purple garment made of silk, with slippers to match. He wore a very fine skull-cap, also of silk, and a pig-tail hung down his back. His eyes were very peculiar. They were placed in his head a little on end; but they were bright and friendly. His mouth was like a little bow. The lips were merry and red. His cheeks were like peaches.

Everychild stopped and looked at the boy, and the boy smiled at him. "I am trying to think of your name," said Everychild, pondering. Surely he had seen this boy before—but where?

"Everychild knows me," returned the boy. "My name is Aladdin."

"Aladdin—of course!" said Everychild. He sat down by Aladdin on the Oriental rug. "And this is your lamp," he said, his eyes shining.

"Alas!—yes," replied Aladdin sadly; and Everychild was surprised that Aladdin could speak sadly. But Aladdin said no more about the lamp just then. He turned his eyes, which seemed a bit askew, upon Everychild. "You were marching bravely as you came along," he said. "I was watching you. And I thought to myself, 'How can any one walk bravely along a road like this?'"

For an instant Everychild's heart was troubled. "Isn't it a good road to walk on?" he asked.

Aladdin's reply was: "It is called The Road of Troubled Children."

Everychild thought a moment. That was a strange name, certainly. "It seems a little lonely," he ventured, thinking that perhaps Aladdin would explain why he did not like the road.

"It is lonely," said Aladdin; "yet all children walk here sometimes. You see, it is a very long road, so that many may walk on it without encountering one another."

Neither spoke for a moment, and there was no sound save the wind in the trees.

Then Aladdin said, "When you have walked here a little longer perhaps you will not walk so bravely." There was an obscure smile on his lips as he said this.

But Everychild replied quickly, "Oh, yes, I shall. You see, I shall remember my friends."

"Your friends?" asked Aladdin.

"Father Time, for one. I wish you could have seen how he took my part!"

Aladdin nodded slowly. "I am hoping he will be a friend to me some day," he said.

"And then there is the Masked Lady," continued Everychild.

"The Masked Lady?" repeated Aladdin in a puzzled tone.

"She lent me her sword."

But Aladdin mused darkly until his eyes rested upon his lamp. "I'd rather persons didn't wear masks—of any sort," he said. "Sometimes they are dangerous enemies."

He seemed so troubled as he said this that Everychild asked him, "But you, Aladdin—why are you making a journey on the Road of Troubled Children?"

"I?" replied Aladdin in surprise. "Why, because I am the most troubled child of all!"

Everychild could scarcely believe this. "And yet," he said, "with your wonderful lamp you have only to wish for things, and they are yours!"

Aladdin made ready to tell his story. He adjusted himself more comfortably on the Oriental rug, and at last he sighed deeply. "The child who has everything is never happy," he said.

Everychild simply could not believe this; and Aladdin read the disbelief in his eyes.

"It is true," he said. "Having everything you wish for is like having more money than any one else. And in such a case, how could one be happy? How many things would be denied one!—pleasant solitude, simple friendships, even a good name. Those who had too little would envy you and hate you; and if you sought to relieve their distress they would hate you more than ever in their hearts, because you would have degraded them. You would have to be a spendthrift, which is vulgar, or you would have to be a miser, which is mean. There is an old saying in Chinese … how shall I put it in your language? Runnings fleet, unhampered feet. You see? The rich have pampered feet. At best they tread soft places. No, it is an evil thing to have too much. I would that the lamp had never been mine."

"If it were mine," said Everychild, unconvinced, "I think I should be happy."

"To be happy," said Aladdin, "means to want something and believe you are going to get it after awhile. But when you've got everything it is a good deal worse than not having anything. Because there's nothing left for you to wish for. And wishing for things is really the greatest pleasure in the world."

"But to wish for things, and never to get them?" said Everychild, deeply puzzled.

"Let me explain," said Aladdin. "I remember when I was a little boy in Peking there came a spring when I wanted a kite. Oh, how I longed for a kite! And my mother said, 'Never mind, Aladdin. When your uncle comes back from Arabia, where he has gone with the camel train, perhaps he will bring you a kite!' And I was very happy all the spring and summer, thinking I should have a kite when my uncle came back from the camel train. And it was not until the next year, when I no longer cared very much about having a kite, that I learned how my uncle had died in the desert, quite early in the spring the year before."

"And then," asked Everychild, "were you not unhappy?"

"No. You see, by that time I had begun to wish for something else. This time it was a pair of little doves which a merchant had brought from far away in the Himalaya mountains. And I dreamed by day and night of the time when I should own the little doves. No coin was too small to be saved. The little coins would become as much as a yen in time. And at last I was the proud possessor of a yen!"

"And then you got the little doves?"

"No. By that time I cared more for the yen than for the little doves—and besides, the doves had died."

"But with the—the yen, you could buy something else you wanted," suggested Everychild.

"Not so. By that time I coveted some ivory chessmen, worth many yen. And I was very happy, planning how some day I should become rich enough to buy the ivory chessmen."

"But if you only kept on wishing for things," murmured Everychild, "and never got them, you'd of course become very unhappy some day!"

But Aladdin slowly shook his head. "I cannot tell how it may be," he said. "But my poor mother was always happy, and she never really got what she wished for, unless it was the last thing of all."

"And that?" inquired Everychild.

"One thing led to another, in her case; and the last thing she wished for was heaven. And then she died."

A great wind roared through the forest and died away in a sigh.

Presently Aladdin spoke again: "And another great trouble about getting what you wish for is that in most cases when you get a thing you find that you didn't really want it, after all. It proves to be not quite what you thought it; or else it came too late."

This statement was completed in so mournful a tone that Everychild felt constrained to say, "Why shouldn't you throw the lamp away, if it makes you unhappy?"

"It isn't possible," was Aladdin's rejoinder. "There is only one way in which I can be rid of it, and I haven't been able to find that way as yet."

Everychild was so greatly puzzled by this statement that Aladdin explained: "I can never be rid of the lamp save on one condition. When I have wished for the best thing of all the lamp will disappear and I may rejoice in the thought that it will never be mine again."

"The best thing of all?" mused Everychild.

"You see how difficult it is. Who can tell what is the best thing of all? And so I must go on owning the lamp and being unhappy."

But Everychild found much of this simply bewildering. "Just the same," he said after a pause, "it must be very nice to have a lamp to rub, so that you may have so many things you really want."

He immediately regretted having said this; for Aladdin took up his lamp. "Very well," he said, placing the lamp in Everychild's hands. And there was a malicious gleam in his slanting eyes as he added, "Suppose you make a wish. But I charge you!—think twice before you wish."

Everychild could not take back his words; and besides, he was tempted. He touched the lamp with trembling fingers. He rubbed it, hoping that Aladdin would not laugh at him for being awkward or inexperienced. And sure enough, the genie of the lamp appeared.

Everychild became quite dumb. He cast an appealing glance at Aladdin. "Won't you make a wish?" he begged. "After all, it's very hard, knowing what to wish for."

"It is," admitted Aladdin. "No, I'll not make a wish. It was you who summoned the genie. You shall make your own wish!"

At this Everychild glanced at the genie as if in search of assistance. But he received no encouragement at all. The genie really looked like a person who had come to bring evil rather than good. And Everychild felt his heart pounding painfully, and his head throbbing. But at last a happy thought occurred to him. He might make a very little wish!

"It is getting dark," he said to the genie, trying to speak as if he were thoroughly experienced in making wishes, "I wish I had a nice place to sleep, here in the forest."

He had scarcely spoken when he realized that he was all alone: Aladdin with his Oriental rug and his lamp was gone; the genie was gone. His hand was resting upon something very soft and cool. It seemed like a carpet, though finer than any carpet he had ever seen. And he remembered how his mother had scolded him more than once for lying on the carpet at home.

"But no one will scold me for lying here," he reflected.

So it came about that on his first night away from home he slept on the beautiful green carpet, with the Road of Troubled Children hard by.

And he could not know that the thing he had wished for, and which had been given him was the very thing which poor beggars, beloved of God, are granted every tranquil summer night.

In the morning he went on his way along the Road of Troubled Children; and it seemed to him that he had gone a very great distance when he heard voices by the roadside. They were the voices of children, and it was plain to Everychild that they were in trouble.

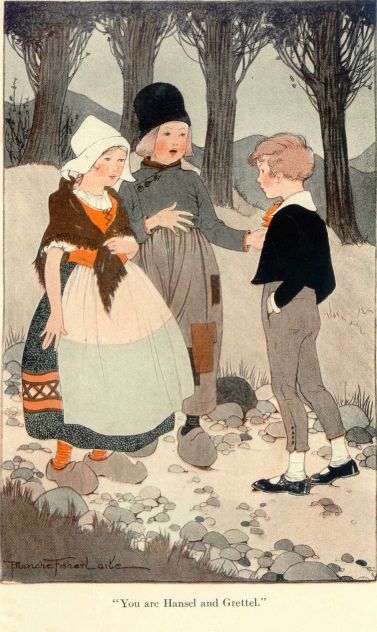

He waited until they came close, and then his heart bounded, because he recognized them. He had often seen their pictures. They were Hansel and Grettel.

Hansel was saying sorrowfully, "I am afraid they are all gone, Grettel, and we shall never be able to find our home again."

It was then that Everychild stepped forward. "I know you," he said, trying to seem really friendly. "You are Hansel and Grettel. Your parents lost you in the woods to be rid of you—because there wasn't enough to eat at home."

Hansel and Grettel looked at each other with round eyes. "It is true," they replied in unison. "But to think it should have got about already! Who are you?"

Everychild addressed himself to Hansel—who, by the way, was a fat boy with wooden shoes and a tiny homespun jacket and trousers of the same stuff, the trousers being very floppy about the ankles. "I am Everychild," he said. "And if I were you I'd not try to go home to such a father and mother. You know, they still had half a loaf left."

"At least," said Hansel, "I'd like to go home until that half a loaf is gone!"

For a second Grettel looked at her brother as if she really could not think of a suitably severe rebuke. "Our poor father and mother!" she exclaimed. "No doubt they thought we should find food in the forest, or that we should encounter travelers who'd have a bite to spare."

"At any rate," said Everychild, "it's no use your searching any more. You're looking for the crumbs you dropped, so you'd find the way home. But I should think you could guess the birds had eaten them all up!"

Hansel turned to Grettel, his eyes more round than ever. "It must be true!" he exclaimed.

"Where you made your mistake was in not dropping pebbles, the way you did the first time—though I suppose you couldn't have got the pebbles, being locked up in your room the night before. Anyway, it's no use your trying to go back. Even if you found the way, the same thing would happen again. Your father made a great mistake when he agreed to lose you the first time, simply because your mother asked him to. You know what the book says: 'If a man yields once he's done for.' You'd much better go along with me."

Hansel became all curiosity at once. "Where to?" he asked.

Everychild undertook to reply quite frankly; but all of a sudden he became dumb. It had seemed to him that he knew very well where he was going. Even now he felt that the answer ought to be perfectly simple. Just the same, he could not think of a single word!

Then he heard a voice behind him. "He has set forth on a quest of Truth!" said the voice.

That was it, of course! He turned gratefully—and there was the Masked Lady! She seemed to be smiling to herself, as if she had thought of something which amused her. But on the whole her manner was really friendly and serious.

Nevertheless, Everychild was not at all sure that he was glad to see her. The mask she wore really did give her a very strange appearance. Still, he faced Hansel with a certain proud bearing. "That is it," he said.

And then he turned about again to look at the Masked Lady, for he had noted that there was something strange about her appearance. She had left her spinning wheel somewhere. Now she carried the crook of a shepherdess. One hand rested lightly on the limb of a tree. And there were sheep not far away. Some were lying on the grass resting; and some were moving about, their eyes and noses seemingly very much alive—and their tails. They wiggled their tails with the greatest energy.

"I didn't expect to see you here," said Everychild.

The Masked Lady replied, again with that queer smile about her lips, "I am very often near when you think I am far away."

And then Everychild perceived another person standing not far from the Masked Lady: a little man wearing large spectacles and thread-bare clothes. He was looking at nothing whatever save a note-book which he carried in his hand, and he was scribbling intently. Occasionally he lifted his hand high and touched the note-book with his pencil, and drew the pencil away with a precise movement. This was when he was making a period.

"And the—the gentleman," said Everychild. "Is he somebody who belongs to you?"

The Masked Lady seemed surprised by this question, until she perceived the little man with the note-book. Then she replied lightly—"Oh—him! That's Mr. Literal. No, he doesn't belong with me. Quite the contrary. Though I believe he likes to be seen in my company."

Everychild stared at the little man called Mr. Literal. "I don't like his looks at all," he admitted. "Maybe he'll go away after awhile?"

The Masked Lady aroused herself slightly. "I can tell you something about him," she said. "He's … you know the kind of boy who is forever tagging along—when you want to go anywhere, I mean? Who is forever disagreeing with you, and wanting things done in a different way? Who winds up by tattling? A tattle-tale I think perhaps you call it."

Everychild nodded his head. "You mean a snitch?" he asked.

The Masked Lady flinched a little, though she smiled too. "Is that the word?" she asked. "Well, I've no doubt it's as good as another. If you like you may think of Mr. Literal as a—a snitch."

The little man made a period on his note-book and drew his pencil away with a precise movement. He looked at the Masked Lady with a smug smile. "That word snitch," he said. "It's entirely out of place, you know—after you've once introduced Aladdin and Hansel and Grettel in your story. And a giant. It's slang, and it came into use long after the race of giants became extinct."

The Masked Lady replied calmly: "The race of giants has never become extinct."

Mr. Literal had not ceased to smile in his smug fashion. "Ah, well," he said; and he began to scribble again, and while he did so he wandered away. You'd have said he had not the slightest idea where he was. He had not even seen Hansel and Grettel!

Everychild looked after the retreating Mr. Literal until he remembered suddenly that he had asked Hansel and Grettel to go along with him. Then he heard Grettel say in a really eager voice: "A quest of Truth! That sounds very interesting to me!"

But Hansel had to spoil it all by saying: "It would sound more interesting to me if he said he was looking for something to eat."

Grettel said, "Oh, Hansel!" in such a tone that Everychild regarded her more closely. She was really quite charming in her wooden shoes, and her ample blue skirt, somewhat short, and her waist of terra-cotta color, with white sleeves. She had on a linen cap shaped somewhat like a sunbonnet. She turned to her brother and spoke with a good deal of emphasis. "Anyway, it's plain you'll not find any sausages growing on the trees. For my part, I'd rather go somewhere. Especially since we've got a nice boy to go with us. Anything would be better than spending another night in the woods. I simply don't believe I could bear it. The noises … there's something dreadful about the noises, when you can't bar a door between you and them."

Hansel grunted very inelegantly. "Noises!" he retorted. "That's just like a girl. The only noise that bothers me is the rumbling of my insides. I'm hungry."

Grettel closed her eyes as if this were really too much. She seemed unable to think of a word to say.

Then Hansel said to Everychild: "I don't mind going with you. Only, you'll have to let Grettel go along too and you can't go very far with a girl without something happening."

"Of course, she'd go along," said Everychild. "As for something happening, it might be something nice more likely than not."

At this Grettel clasped her hands in ecstacy. "What a nice boy!" she exclaimed.

But Hansel only gave her a lofty look. "I haven't seen him do anything great," he said. "Now, if he could show us something to eat …"

"At least," said Grettel, "he wants to keep on going, while you're all for turning back. I think he speaks very sensibly." And she came forward with a pretty blush on her cheeks and took a seat demurely by Everychild's side.

She was really startled when Hansel, in his most offensive voice, exclaimed—"Grettel! Don't you know you're not allowed to sit on the ground in your best dress?"

But she managed to say, with a certain amount of independence, "Oh, Hansel—as if anything mattered now! Don't you see that if we're not going back we'll have to make rules for ourselves from now on? I've always wanted to do whatever I pleased in my best dress, and I'm not going to miss the chance now!"

Hansel looked knowingly at Everychild, and jerked his head toward Grettel. "Females!" he said. "That's why you have to sit on them. They're like kites. Once you let them go they're over in the next field standing on their heads."

But Everychild thought he should rather talk to Grettel. He looked at her with a smile, and immediately she began to pluck at her skirt and pat her hair and look at him out of a corner of her eye. He said: "It was good of your parents, wasn't it, to put your best clothes on you when they meant to lose you?"

She replied promptly: "I should have thought it very mean of them if they hadn't."

Hansel seemed to agree with his sister for once; and he added to what she had said, "And you'll notice they didn't put any bread and cheese in the pockets, so far as anybody can find out."

But Grettel threw her hands up and permitted her head to wilt over on one side. "There! We might just as well be going," she said. "Hansel never has a decent word to say. When he's hungry he growls; and when he's eaten he nods. For my part, it would be a relief to see him nod awhile. Come, let's be getting along!"

And so they set forth along the road. They had not gone far, however, when they espied a youth crossing the road before them.

It could be seen at once that he was on a very important mission, and Everychild said to his companions, "Perhaps we ought not to disturb him. Let us wait, and it may be that he will cross the road and go on his way."

But the youth did not do this. He had heard the children approaching, and he remained standing in the road, waiting for them to come up.

Grettel was already looking at the youth out of the corner of her eye and smiling.

"I'm going to speak to him," declared Hansel.

"Hansel!" exclaimed Grettel; "we mustn't disturb him!" And she glanced at Everychild for approval—though she hastily turned again so that she was observing the strange youth out of the comer of her eye, and she smiled more invitingly than ever.

"I don't care!" retorted Hansel. "He looks like a rich man's son, and he might tell us where we could get something to eat."

Just then the strange youth began to approach them with a proud air. He was really very handsome. He was very sturdy, and he was clothed smartly in a velvet jacket and knee breeches. A fine cloak fell loosely from his shoulders. He wore a plumed hat and carried a sword.

As he drew near Hansel said: "Hello! Have they been trying to lose you too?"

It was then that Everychild recognized the strange youth as Jack the Giant Killer; and at the same time he heard Grettel whispering:

"How handsome he is!"

Jack the Giant Killer replied smilingly to Hansel: "Lose me? Not at all! It's plain you don't know who I am." He touched his breast lightly with his forefinger. "I am Jack the Giant Killer." He then brought his heels together and removed his hat with a wide gesture, and made a fine bow.

"I recognized you," said Everychild, "though I didn't know you lived in this neighborhood. I mean, near Hansel and Grettel."

Jack replied with a certain neat air: "I don't live anywhere in particular. Did you never hear of my seven-league hoots? I have a way of bobbing up wherever there are any giants."

In the meantime Grettel had sat down on a grassy bank beside the road. "It's very tiresome, walking," she said. And then, very politely (to Jack), "Won't you sit down?"

He accepted this invitation, and Everychild and Hansel also sat down.

Grettel sighed and said: "I'd like so much to hear about your fights with the giants. It must be wonderful to know how to fight."

Jack could not help saying "Ho—hum!" in a rather bored way, though he politely placed his hand over his mouth. "There's nothing great about it," he said, "when you're fixed for it. I've my seven-league boots, and my invisible cloak, and my sword of sharpness. You can't help winning with them. Of course, there's my wit, too."

Grettel smiled mysteriously and nodded her head. "It's your wit first of all," she declared knowingly.

Hansel was pouting. "Your wit?" he said; "does it help you to get what you want? If it does, I'd like to know about it."

Grettel had wriggled herself into a comfortable position; but now she sat up stiffly. She put her hand over her mouth and whispered, "Please, Hansel, don't say anything about food!" But she quickly turned an untroubled face to Jack, who was saying:

"There's the way I got old Blunderbore, for example. You've heard about that, haven't you?" And he looked anxiously at all three, one after another.

Everychild and Hansel looked at each other dubiously, but Grettel saved the situation by saying, "It was rather a long time ago. If you'd just go over it again …"

"That was my most famous piece of work," said Jack. "You see, I carry a leather pouch under my cloak. It's filled with food——"

There was an almost violent interruption by Hansel. "Food!" he exclaimed. But Grettel edged closer to him so that she could tug at his sleeve without being seen.

"Of course!" continued Jack. "Well, one day after I'd had dinner with Blunderbore I boasted that I could do something he couldn't do. He laughed—and I knew I had him. Says I, 'Very well, I'll show you. I'm going to rip my stomach open without feeling it.' We'd been eating ginger-bread, and I'd slipped a piece into my pouch."

A strange light had come into Hansel's eyes, and he sighed with ecstacy "Ginger-bread!"

"So," resumed Jack, "I plunged my knife into my pouch hidden under my cloak, and a fine bit of ginger-bread tumbled out."

Everychild repeated the words—"Into the pouch hidden under your cloak." And Jack concluded with—

"Of course—so."

He made an expert pass with his sword, and instantly a number of red apples and a dozen fine tarts rolled from under his cloak and were lying there on the grass.

Without even a hint of ceremony Hansel flung himself forward on his stomach and seized upon the tarts greedily.

Even Grettel could not conceal her desire for food, and she exclaimed joyously, "Oh, tarts! Could I have one?"

"Why not?" replied Jack lightly; whereupon Everychild placed a number of the tarts in her lap, and she began to eat heartily.

"This comes of wearing one's good dress," said Grettel between tarts. "If I'd been wearing an old rag I'd have seen no tricks, that's certain."

Jack regarded her a little curiously. "As I was saying," he resumed, "old Blunderbore shouted 'Pooh-hoo!' at what I had done. That was his ugly, boasting way, you know. He jabbed his knife into his own stomach to show he wasn't to be outdone—and down he fell, dead as a doornail."

Everychild's heart was beating hard and his face wore a troubled expression. "I suppose," he said after a thoughtful pause, "Blunderbore was a very wicked giant—like the Giant Fear?"

Jack was frankly surprised at this question. "A giant is a giant," he said shortly.

But the troubled expression did not leave Everychild's face. What if there were a few good giants?—and what if a good giant should encounter Jack?

His reflections were broken in upon by a triumphant voice—Jack's voice—exclaiming, "Here's luck for you! Here's one of them coming now!"

It was true. A very large giant was approaching through the forest. And the strangest part of it all was that Everychild knew quite well that this was a good giant. His eyes began to shine and he was thrilled through and through.

He had never seen so wonderful a creature: so splendid, so powerful, so fascinating. The giant seemed almost to tread on air. He held his face up so that the sun shone on it. His eyes were filled with magic. He wore a wreath of leaves about his hair. A garment like a toga fell gracefully from his shoulders. He was shod with sandals. He carried his hands before him as if they would gather in the sunshine. A smile half sly and half gentle was on his lips.

Everychild clasped his hands eagerly as he gazed at the giant. He seemed to know that this splendid stranger would lead him presently, and he was not certain whether he should wish to be led or not—whether it would be good or evil to be led by him.

His musing and wonder were broken in upon by Jack, who was again speaking. "I'll give you a little exhibition of my skill," he said, "I'll have his life before your very eyes."

Everychild became greatly troubled. He could not speak for a moment. He could not bear to think that the giant should be slain. He even ventured to hope that he had no cause for fear—that so powerful a creature might be depended upon to protect himself. Yet Jack the Giant Killer seemed just now a very valiant figure, and it was plain that he believed it to be his duty to slay the approaching giant.

It was Grettel who replied to Jack. "Dear me!" she exclaimed incredulously, "How shall you do it?"

"I haven't thought of a way yet," was the response. "It takes wit, you know. I'll think of a way before long. Don't speak so loud."

The giant had come quite close to them by this time. "Good morning," he said pleasantly.

Not one of the children recognized him, and Everychild ventured to say, in a polite tone, "Good morning … though I don't believe we know who you are." He was thinking: "If he will only explain that he is a good giant!"

"I am known as the giant, Will o'Dreams," was the reply.

Everychild was charmed by the beauty of his voice; but he was startled when Jack cried out sternly,—

"And what are you doing here?"

The giant regarded Jack with thoughtful eyes. "A natural question, I am sure," he said after a pause. "Permit me to say, then, that I have merely been looking at a few masterpieces."

At this Everychild felt a delightful sense of mystery stir within him. The words seemed tremendous—and yet he could not think what they meant!

But Jack the Giant Killer nodded his head shrewdly. And almost instantly he said, "Well, you'll look at no more masterpieces—whatever they are!"

The giant seemed to be simply amused. "Say you so?" he replied.

Grettel clasped her hands with delight. "How suitably he talks!" said she.

"I do," said Jack. "You don't know me, eh? I'm Jack the Giant Killer. And you're just about my size."

It was here that Everychild interfered. "Maybe he's a good giant," he said to Jack. And to the giant he added courteously, "Won't you sit down and rest awhile, Will o'Dreams?"

"I thank you," responded the giant; and he sat down by the side of Everychild.

And instantly the thought came to Everychild that at whatever cost he must save the splendid stranger from that terrible sword of sharpness which Jack the Giant Killer was even now drawing from its scabbard.

It was plain that Jack was in a determined mood. He was no longer seated with the others. He drew off a little and capered in a very confident manner. For the moment he was content to say nothing more to the giant. He had drawn his sword; and now he hopped about, cutting the heads from tall grasses and tender twigs from the trees.

You would have said that his mind was very far away but for the fact that he occasionally glanced at the others to see if this or that skilful pass had been witnessed; and occasionally he gazed at the giant in a very stern manner.

As for the giant, he spoke pleasantly to Everychild, asking him whither he was bound; and when Everychild replied, quite simply, that he had set out in quest of Truth, the giant nodded his approval.

It was Everychild who introduced the subject of Jack and the threat he had made. "Maybe he'll not do anything when he finds you're a good giant," he said; "and anyway, I suppose you'll know how to defend yourself—a big fellow like you?"

He was greatly disturbed by the giant's reply. "I'm a big fellow, yes," said Will o'Dreams, "and I can hold my own with other big fellows. You know how to take them. But when you're a giant it seems you don't know how to take the little chaps. I've always regarded Jack the Giant Killer as a brave and honorable youth. But some of the little fellows are hard to handle. They're full of tricks and deceit. I've had many a tussle in my time; but when it comes to a fair test, give me a man who's got honest strength—who's ashamed to do mean tricks."

Everychild was considering this when he heard a voice behind him; and turning his head, he was surprised to perceive that the Masked Lady was standing there, quite close to him, and that Mr. Literal was only a step or two distant. Mr. Literal held his note-book before him, and he had just lifted his hand with a flourish, after putting a period after something he had written. It was he who was speaking.

"It's all very well," said Mr. Literal to the Masked Lady, "for him to be making friends with that giant," and he nodded his head toward Everychild and his companion, "but just the same, I could wish to see him in better company. Look at the giant's eyes. Visionary eyes. Very little precise thinking going on back of a pair of eyes like that!"

The Masked Lady replied quietly: "It's only little creatures who consider precision the first of all merits. Let them alone."

Everychild's attention was attracted then by Jack, whose manner had suddenly changed and who now approached the giant with a mysterious smile on his lips.

"You know," said Jack, "I was only joking awhile ago when I spoke roughly to you."

"Ah, it's all right then," replied the giant in a tone of relief.

"Yes, I was only joking. Just my way of getting acquainted." And he continued to smile.

Presently he added meditatively. "A big chap like you—it must be wonderful to be as strong as you are. The way you ought to be able to handle a sword—I suppose you carry a sword, of course?"

"Nothing like it!" replied the giant.

"You don't say so! A terrible bludgeon then, no doubt?"

"No. You see, my taste doesn't run in that direction. When I'm wishing for power or fame I think of … it's a little difficult to explain. Wings. I wish for powerful big wings, so that time and space couldn't hold me back."

"Wings! That sounds funny!" said Jack. "But a sling-shot, at least—of course you carry a fine sling-shot around with you?"

"No, nor a sling-shot." The giant extended his arms with a candid gesture, so that Jack might see he was wholly unarmed.

Then a very amazing thing happened. Jack the Giant Killer suddenly uttered a cry of triumph. "Fool that you are!" he exclaimed, "to confess that you are helpless! Do you suppose we are deceived by your make-believe friendliness? Prepare to die!" And he lowered his sword with a swift flourish.

So terrible was his manner that it seemed the giant was really lost. Every one felt this. Grettel clasped her hands tensely and a light at once fearful and eager leaped into her eyes. Hansel drew back as if to be out of the way of danger. The giant, pale yet unflinching, arose.

It was then that Everychild, springing to the side of the giant, cried out in a ringing tone—

"Stay!"

The giant calmly lifted his hand and gazed into space; and at that moment, from out the depths of the forest, came a commanding voice, exclaiming—

"Jack the Giant Killer! Jack the Giant Killer!"

The voice was distant, yet sonorous and stern.

Everychild looked to see who it was that had spoken: and whom should he behold emerging from the forest but Father Time! He carried his scythe and sand-glass, and he moved forward with majesty, yet with haste. He fixed his gaze upon Jack and uttered one more thrilling word—"Stop!"

To Everychild he seemed a changed person as he adjusted both his scythe and his sand-glass in his left hand and advanced with his right hand uplifted. He seemed very stern. His eyes traveled from one face to another until at length they rested only on Jack. Then upon the shoulder of Jack the Giant Killer his hand descended.

Everychild could scarcely believe his own eyes for a moment or two. A tragic change occurred in the youth who had been so splendid.

He had become old and infirm! His clothes were in tatters, his form was bent, his sword was covered with rust.

Then Jack—trembling and helpless—looked wonderingly and forlornly at Father Time. "What have you done to me?" he asked in a quivering voice.

Father Time replied calmly: "I have laid my hand on your shoulder!"

"Yes—but I don't mean that," said Jack. "Something strange … my boots: see, they have been changed. They were new and wonderful. In them I could take steps seven leagues long!"

Father Time replied: "Jack the Giant Killer, when I have laid my hand upon you again and yet again, you shall possess the true seven-league boots. They shall carry you seventy times seven leagues—and beyond."

"And my invisible cloak—it was rich and fine before you came; and now it is ragged."

"Jack the Giant Killer, when I have laid my hand upon you again and yet again, it shall be given to you to wear the true and only invisible cloak."

Jack looked ruefully at his sword. With a sob he exclaimed, "And my sword of sharpness!…"

Father Time replied, "Jack the Giant Killer, beneath my touch the sword of sharpness becomes the sword of rust."

For an instant Jack searched the faces of the others. "Have I no friend here?" he demanded. "Will no one take my part?"

Everychild's heart was touched with pity; but before he could speak Father Time continued:

"I am your friend. And I bid you go home and cultivate those virtues which you know not. Be patient, and contentment shall come: a friend more unfailing than a strong arm. And hope shall come: a friend more fleet than seven-league boots. And faith shall be yours: far better raiment than your cloak which was invisible."

But Jack hung his head. "And my beautiful sword that was my pride …"

To the amazement of all it was the giant, Will o'Dreams, who stepped forward to comfort Jack. In a voice which was marvelously kind he said:

"I know you for a brave youth, Jack the Giant Killer; and as for me, it has been said that I am generous. Listen: I alone among all the race of giants have power to bid Father Time move speedily, or to retrace his steps. Let us see what I can do."

He solemnly lifted his hand, and Father Time, walking backward, disappeared in the forest.

At that very moment the Masked Lady took a step forward, saying in a soft and soothing voice:

"Jack the Giant Killer, if you will come to me with all your heart and place your hand in mine, I can make you beautiful and strong, despite all that Father Time has done."

Jack lifted his troubled eyes to hers. "You?" he asked. And then he tried to approach her, but he had become too infirm. "I cannot!" he cried despairingly.

He would have fallen, but the gentle hand of the giant, Will o'Dreams, was instantly about him, supporting him. "Let me help," he said.

Everychild's heart was beating loudly. "Let me help too!" he cried. "I have always been fond of Jack the Giant Killer."

Between these two, then, the infirm little old man, who had been the gay youth, moved totteringly toward the Masked Lady. With a slow, tremulous gesture he placed his hand in hers, which was stretched out to him.

A miracle! He was instantly the brave and gallant youth again, seven-league boots, invisible cloak, sword of sharpness and all!

He lifted his sword with a great shout of joy. And then, remembering his manners, he said to the Masked Lady, "I thank you, lady!" And to Everychild he said, "They shall never be deceived who put their faith in you." And to the giant, Will o'Dreams, he said, after a solemn pause—"It may be that you shall see me fight again; but when that day comes, I shall be fighting on your side!"

And so he marched gallantly away into the forest.

It was then that Everychild observed that the night was falling. "Perhaps we ought to sleep awhile," he said to his companions. "This seems a very nice place, and we may have to go a long distance to-morrow."

They all found places on the grassy bank, the giant Will o'Dreams lying down beside Everychild like a true friend.

They had no sooner taken their places than it was really night. Insects in the forest about them made a droning sound. A distant bell rang faintly. One by one the members of the band fell asleep.

All save Everychild. He alone was wakeful. And he knew that the Masked Lady had taken a step forward and was looking down at him.

He lifted himself on his elbow and looked away toward the sky where it appeared through the trees. And suddenly he exclaimed. "Oh, wonderful! I think I saw a star fall!"

The Masked Lady spoke to him soothingly: "Perhaps. They fall every little while."

Everychild had not known this. "Do they?" he asked; "I wonder why?"

The Masked Lady said, "Perhaps it is so we may know that they don't amount to very much, after all."

"Not amount to much! But they are worlds, aren't they?"

"Yes, they are worlds."

"Then if they don't amount to a great deal, is there anything that does?"

"Nothing but human beings."

"Human beings … and why do they?"

"Because every human being—even the most obscure or humble or wayward—is a little bit of God."

Everychild pondered that. It gave him a deep feeling of comfort. He gazed away into the mysterious sky. He mused, "What a journey I shall have to-morrow, with my new friend by my side."

He fell asleep repeating the words, "A little bit of God—a little bit of God …"

Scarcely had he fallen asleep when a stealthy figure emerged from the gloom of night and sought out the place where Will o'Dreams lay sleeping. The stealthy figure proved to be none other than Mr. Literal; and after he had stood looking down upon the sleeping band an instant, he kicked the Giant's foot warily.

The giant was up in an instant. His first thought was that his services were needed. There was no hint of resentment in his heart; and he proved his gentle qualities by moving carefully, so that the others would not be disturbed.

He bent his head above Mr. Literal to hear what he had to say.

"Follow me!" said Mr. Literal coldly; and without more ado he turned and led the way into the depths of the forest, the giant following him wonderingly.

They came before long to an old house with all the blinds drawn save at one window, through which the beams of a lamp shone dimly.

Mr. Literal opened the front door, which creaked angrily. He lighted a hall lamp so that he and the giant might find their way up a flight of stairs in safety. A musty odor filled the giant's nostrils, causing him to wrinkle his nose slightly. But he said nothing.

Up the stairway they proceeded, and into a study. It was in this room that a lamp had been left burning.

Mr. Literal approached a table and drew forth two chairs. "Sit down," he said, still without looking at the giant. And Will o'Dreams seated himself in one of the chairs and waited for Mr. Literal to explain his somewhat peculiar behavior.

As an immediate explanation did not seem to be forthcoming, he employed his spare time in looking about the room. There was dust everywhere, and frayed rugs and faded hangings. But there were a number of busts which were really a delight to the eye: of Shakespeare, of Burns, of Victor Hugo, of Dickens and of others. And there were book cases filled to overflowing with books—all dust-covered, as if they had not been touched for years.

Mr. Literal took a seat at last; and for a moment there was silence in the room and throughout the old house, save that a window rattled somewhere in the night breezes. Then Mr. Literal leaned forward deliberately, his finger tips fitted together and his lips drawn into very prim lines. And at last he spoke.

"Listen to me, Mr. Will o'Dreams: I know you!" His tone was triumphant, merciless.

But the giant only nodded politely and said, "Very well, Mr. Literal; and I know you, too!"

"At least," said Mr. Literal icily, "I do not go about under an assumed name!"

"Nor do I," replied the other.

"It is false!" exclaimed Mr. Literal. "I know you too well. You are that evil creature, Imagination."

"I am sometimes called so," admitted the giant candidly. "The name has a somewhat formidable sound. I prefer to be known as Will o'Dreams—that is all."

"You are trying to evade the truth," declared Mr. Literal. "Well do you know that if you were to make your real name known, honest folk would shun you."

The giant only waved his hand lightly. "I will not argue with you," he said.

"But I have something else to say to you," said Mr. Literal. "Your statement to those children on the road—that was false too."

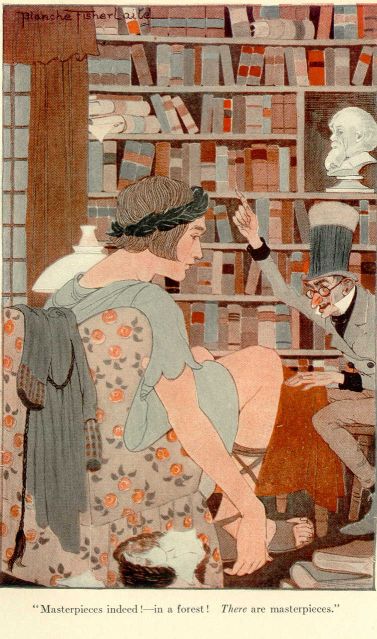

"What statement?" inquired the giant, his brows lifting slightly.

"You informed them that you were looking for masterpieces; yet you know well that your real purpose was to becloud the young minds of those children—to turn them from the quest of Truth. Dare you deny this?"

"I do indeed. I assert again: I was looking for masterpieces."

"Masterpieces indeed!—in a forest! There are masterpieces"—and he pointed to the bookcases. "But you were not even looking for my house."

"I was not thinking of books," admitted the giant.

"I grant, there are other kinds of masterpieces," said Mr. Literal; "but they are not to be found in a forest."

"Ah, Mr. Literal!" cried the giant. "I would that I might open your eyes. Believe me, the forest is filled with masterpieces of such perfection as the hand of man can never know."

"So—then name me one!"

"The tiniest leaf that falls from its stem. Not all the human race could duplicate it. The humblest plant. The human eye has no power to take in all its marvels. And as for the trees—what has the world produced that can match them?"

Mr. Literal was flushing uncomfortably. "That is a large boast," he said. "The world has produced Karnac; it has produced the Petit Trianon, and St. Peter's and St. Paul's."

"But my dear sir," cried the giant warmly, "cannot you see that the most labored structure of man is crude and clumsy and artificial, when compared with any tree in all the world? Houses are dead, pathetic things. They begin to decay the moment they are built. Rightly seen they are hideous, save when they are considered in relation to some simple human need. They keep the wind and rain away—for which, God knows, we should be the better sometimes. They have no beauty save the spirit of human striving that is within them—and that too often is a tarnished thing. But a tree! There are fairies under the trees, truly! True aspirations hover about them, and beautiful dreams." He lowered his voice and said reverently, "The Holy Spirit is all about them."

"They are simply trees," said Mr. Literal harshly.

"Yes," agreed the giant, nodding and smiling, "they are simply trees."

But Mr. Literal hitched his chair forward angrily. "We are talking nonsense," he declared. "It is your plan to divert me from my purpose. But you shall not do so. Listen: I forbid you to associate with those innocent children. You would corrupt them. It shall be my duty to expose you if you do not cease from following after them. Do you hear?"

The giant bowed his head thoughtfully. "You ask too much," he said. "I know I have done evil in my time. But I am repentant. Come, believe me when I say that I would be only a friendly companion to those children. I would add to their innocent joys and take from their sorrows. You do not know me, really. I have no wish to offend you; but I tell you you ask too much when you bid me turn aside from that pleasant company."

He arose and turned toward the door.

"You are warned," said Mr. Literal. "Persist in your present course and I shall bring you to your knees."

"Abandon Everychild?" said the giant musingly. And he shook his head. "No," he said. Then, wishing to conciliate the old man, he looked about him to where the busts reposed. "They are all friends of mine," he said with a pleasant smile.

"They are all dead," said Mr. Literal coldly.

"What!—Shakespeare dead?" cried the giant in amazement. But he did not remain for other words. Mr. Literal was staring stupidly at nothing. He went out into the hall and closed the door behind him. He would have descended the stairs then, but some one brushed against him lightly and whispered, "Why do you waste your time in there?"

"I went in against my will," said the giant.

The stranger said in glad tones, "I know you well."

The giant replied, "My name is Will o'Dreams."

"Yes, yes," said the other. "My name is Will, too. Though certain well-meaning persons have always preferred to refer to me as William. I used to write plays, you know."

The giant gazed at him in the dim light. "Of course," he said.

"I used to live beside the Avon," said the other.

The giant's heart grew soft. "It is a beautiful stream," he said. "And children play along its banks, just as in the old days, and men and women passing that way are the happier because you once dwelt there."

But the other held up a cautioning finger. His eyes twinkled mischievously in the dim light. "Not so loud," he said. "Old Mr. Literal will hear you—and you know he doesn't know I am here!"

They parted then; and the giant went back to his place where the children lay asleep.

Everychild thought perhaps he had been asleep a long time when he was awakened by the sound of a clock in a distant tower striking the hour of 1. He became quite wide awake.

He looked to his right and to his left. Hansel and Grettel were on one side of him, sleeping deeply. Hansel was even snoring. The giant, on his other side, lay motionless.

He looked to see if the Masked Lady had remained near him, but she was nowhere to be seen. Mr. Literal also had disappeared.

Then he sat up suddenly, his heart thumping loudly. There was the sound of hurrying feet on the road nearby. And there was something about the sound … you could tell that it was some one who was lost, or in trouble. Presently there was a sound of weeping too.

Everychild sat with his hands clasped about his knees, staring at the road: and before long, there she was—a girl running as if she were in great peril. And as she drew nearer Everychild felt quite sure he knew who the girl was. He could not be sure how he knew. But a name came into his mind, and he said to himself, "It is Cinderella."

She raced past him as if she were a leaf caught in the wind. Again he heard her weeping. And then, without at all knowing what he intended to do, he sprang to his feet and dashed down the road after her. It would be fine to speak to her, he thought. And besides, it seemed almost certain that she needed help.

But it was amazing how fast she could run. He thought: "That's the kind of a girl you would like to play with—a girl who can run like that."

Still, he hoped she would become tired before long, so that he might overtake her. After all, it was rather uncomfortable, pursuing her in the dark. His own feet made a fearful noise—a ghostly patter which awoke the night echoes.

Moreover, certain wild creatures of the forest were disturbed. An owl dashed from its branches overhead and went sailing down the avenues of the forest. A rabbit, sitting on a little hummock, dropped its forefeet to the ground and went prancing away, to wheel presently and look at the road suspiciously.

"I'll never overtake her," thought Everychild. He could just see her now: a mere blur in the shadows far ahead of him. He could no longer hear the sound of her feet. Then quite suddenly she disappeared.

Had she fallen? Had she hidden behind a tree? Was she afraid of him?

He ran more softly. If she were hiding he must not frighten her. If he could only speak to her once she would know very well that she need not fear him.

But when he came to the spot where she had disappeared he perceived immediately that she had not hidden. At this point a path turned away from the road, and it seemed clear that she had taken the path.

The path led into a deeper forest. It became very silent and black. He could barely see the path beneath his feet. And it seemed to him that he was now all surrounded by living, hidden creatures, who knew that he was passing. But he could not feel that Cinderella was anywhere near him.

The path turned into a lane, and the lane entered a region where there were vague fields on either side, fields in which things had been planted. And then he stopped suddenly, not knowing whether he should continue on his way, or return to his companions by the side of the road. He had discerned a house before him, standing on the top of a hill. And although it was very late, a single light burned in one of its windows.

For just a moment he reflected; and then he continued on his way, in the direction of that lighted window.

For just a few moments let us enter that house of the lighted window, that we may witness certain strange happenings.

We come into an immense, old-fashioned kitchen or scullery.

A candle burned on a mantel, sending its tranquil light out into the room and creating ghostly shadows. Under the mantel, in the deepest shadows of all, andirons and a crane seemed to be slinking back as if they were hiding.

In the center of the room there was a rough wooden table. Over against the wall, near the door which opened to the highway, stood a grandfather's clock, ticking severely, as if it were dissatisfied with the way things were going in the house. There were a number of other doors visible, all closed as if they were saying, "This is an orderly house, and everybody has gone to bed, of course!"

But everybody hadn't gone to bed! Over beyond the wooden table, against the wall, there was a bed, and there was nobody in it. Moreover, there was a figure seated at the wooden table: the figure of a woman, who silently polished the spoons which were scattered before her. She had already scoured certain pots and pans which were piled in a heap near her hand.

Suddenly the strange happenings began.

A mouse appeared among the pots and pans on the table. It sat an instant, with alert eyes and fidgety nose and whiskers, and then it scrambled down the leg of the table and crossed the floor in the direction of the grandfather's clock. An instant later there it was again, climbing up the white face of the clock!

The clock ticked more severely than ever. The mouse disappeared amid the works of the clock: and presto! The clock loudly struck one.

The mouse darted into sight again, slipping down across the face of the clock. Then it disappeared.

The vibrations of the clock, filling the room as with a great clamor, slowly died away.

Then there was another sound: a nervous rattling of the latch on the door opening to the highway. The door opened rather abruptly, and Cinderella, panting and pale, stood on the threshold.

For an instant she seemed afraid to enter; yet plainly she was also afraid to remain standing there on the threshold. She glanced swiftly about the room and then she entered and closed the door sharply behind her. She stood for a moment, panting and leaning against the door.

There was something very strange about her; for although she was weary and frightened, and clad in the shabbiest old dress imaginable, her face nevertheless shone with rapture.

Need I tell you what had occurred to her? She had forgotten what the good fairy had told her about coming home before one o'clock; and as a result her coach-and-four and her coachman had been changed back to what they had originally been: a pumpkin, a rat, and four mice. What a disaster!

Yet after she had stood against the door long enough to catch her breath she advanced into the room, thrusting her arms upward and forward as if she were embracing a lovely vision. Her eyes burned with a glorious light.

She had not seen the figure at the table, bending over the spoons. It was plain that in imagination she was seeing something far different. And then she uttered these words (to nobody at all!):

"Oh, the wonder of it, the wonder of it!"

Then something else happened. One of the inner doors opened and a young lady stood craning her neck so that she could look into the room. She stood so an instant, and then she was joined by another young lady, and both came into the room.

They were both simply glorious in party-frocks, though on the skirt of one the ruffles had been bunched clumsily, and the bodice of the other was slightly twisted.

They were Cinderella's sisters.

The first sister had opened the door just in time to hear what Cinderella said; and now she rather cleverly imitated Cinderella's words and manner—

"'Oh, the wonder of it!' The wonder of what?"

For a moment longer Cinderella gazed into space, her eyes holding a glorious vision. Then, lowering her gaze and observing her sisters, she said, a little less fervently, "Oh … everything!"

The second sister now spoke. There was a pitying note in her voice as she said to the first sister, "As if she had the slightest idea of anything as wonderful as the things we've seen!"

To which the first sister replied with a sigh—"Poor Cinderella!"

But Cinderella only turned away from them that she might hide the secret in her eyes. She sat down before the fireplace, and the two sisters seated themselves on either side of her. None of them had taken the slightest notice of the figure at the wooden table in the middle of the room.

Cinderella seemed to be dreaming again, while the two sisters were plainly overflowing with excitement. They glanced at each other across Cinderella as if to say, "Shall we tell her?" And each nodded eagerly to the other.

Then said the second sister: "It is we who have seen the truly wonderful things, Cinderella."

"Yes," said Cinderella dreamily, "I know."

Said the first sister: "But you don't know—not the half. You know we've been to the ball, but you don't know what happened there."

Cinderella leaned forward, resting her cheeks in her hands. Her sisters could not see her eyes. "Tell me what happened," she said.

"The most wonderful princess came to the ball," said the first sister. "Quite a stranger—not a soul knew her. She was a sensation."

The second sister could scarcely wait to add, "The loveliest creature ever seen!"

Cinderella looked at her sisters now, one after the other. Her eyes seemed to caress them. "Ah, tell me about her," she said.

Said the first sister: "She first came last night—and then again to-night. She came late, from nobody knew where in an equipage the like of which was never seen before. She came late and left early."