The Project Gutenberg EBook of St. Nicholas Magazine for Boys and Girls, Vol. 5, September 1878, No. 11, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: St. Nicholas Magazine for Boys and Girls, Vol. 5, September 1878, No. 11 Author: Various Editor: Mary Mapes Dodge Release Date: December 28, 2005 [EBook #17409] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ST. NICHOLAS MAGAZINE *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, LM Bornath, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

When I was a boy, I lived on the rugged coast of New England. The sea abounded in cod, hake, mackerel, and many other kinds of fish. The mackerel came in "schools" in late summer, and sometimes were very plentiful. One day, my uncle James determined to go after some of these fish, with his son George, and invited me to go with them. We were to start before day-break the next morning. I went to bed that night with an impatient heart, and it was a long time before I could go to sleep. After I did get asleep, I dreamed of the whale that swallowed Jonah, and all kinds of fishes, big and little. I was awakened by somebody calling, in a very loud voice, "Robert! Robert!" I jumped out of bed, with my eyes not more than half opened, and fell over the chair on which I had put my clothes. This made me open my eyes, and I soon realized that the voice proceeded from my cousin George, who had come to arouse me for the fishing-voyage.

I dressed as quickly as possible, and went downstairs. All was quiet in the house except the old clock ticking in the kitchen. I went out-of-doors and found the stars still shining. It was half-past three o'clock in the morning. There was no sign of daylight, and even the cocks had not begun to crow. In the darkness I espied George, who said, "Come, it is time to start. Father is waiting for you."

We walked across the fields to my uncle's house. Taking each a basket and knife, we began our journey, and soon entered the pine-woods. As we walked along in the darkness, we could scarcely see each other or the path. The wind was sighing mournfully among the tree-tops, and, as we gazed upward, we could see the stars twinkling in the clear sky.

We soon emerged from the forest, and came to a sandy plain. Before us was the ocean, just discernible. There were two or three lights, belonging to vessels that were anchored near the shore. We could see the waves and hear their murmur, as they broke gently upon the shore. A soft breeze was blowing from the west, and the sea was almost as smooth as a pond.

When we reached the beach, we found that it was low water. The boat was at high-water mark. What should we do? We did as the fishermen in that region always do in the same circumstances—took two rollers, perhaps six inches in diameter, lifted the bow of the boat, put one of the rollers under it, and the other upon the sand about eight feet in front of it. We then pushed the boat until it reached the second roller, and rolled it upon that until the other was left behind. Then the first was put in front of the boat, and so we kept on until our craft reached the water. Uncle James and George took the oars, and I sat in the stern, with the tiller in my hand, to steer.

We got out over the breakers without difficulty, and rowed toward the fishing-ground. It is queer that fishermen call the place where they fish, "the ground," but that is only one of the many queer things that they do. By this time, daylight had come. The eastern sky was gorgeous with purple and red, and hues that no mortal can describe. Soon a red arc appeared, and then the whole glorious sun, looking more grand and beautiful than can be thought of by one who has never seen the sun rise over the sea.

"How glorious!" I exclaimed, impulsively.

"Yes; it is a first-rate morning for fishing," said my uncle, whose mind was evidently upon business, and not upon the beauties of nature.

After rowing about three miles, we stopped, and prepared for fishing. Each of us had two lines, about twenty feet long. The hooks were about as big as large trout-hooks. Pewter had been run around the upper part of them, so that "sinkers" were not required. The pewter answered a double purpose; it did duty as a sinker, and, being bright, attracted the notice of the fish. Uncle James had brought with him some clams, which we cut from their shells and put on the hooks. We threw in our lines and waited for a bite. We did not wait long, for, in less than a minute, George cried out, in the most excited manner, "There's a fish on my hook!"

"Pull, then!" shouted his father.

He was too agitated to pull at first, but, at length, managed to haul in his line, and, behold, a slender fish, about eight inches long, showing all the colors of the rainbow, as he held it up in the morning sun! It was our first mackerel. While admiring George's prize, I suddenly became aware of a lively tug at one of my own lines. I pulled it in, and found that I had caught a fish just like the other, only a little larger. No sooner had I taken it from the hook than my other line was violently jerked. I hauled it in hurriedly, and on the end of it was—not a mackerel, but a small, brown fish, with a big head and an enormous mouth. I was about to take it from the hook when my uncle called, "Look out!" He seized it, and showed me the long, needle-like projections on its back, with which, but for his interference, my hand might have been badly wounded. This unwelcome visitor was a sculpin. Sculpins are very numerous in this region.

Uncle James explained how I happened to catch one of them. They swim at a much greater depth than mackerel usually do, and, while I was busy with one line, the other had sunk some twelve or fifteen feet down where the sculpins dwelt.

When mackerel are inclined to take the bait, they are usually close to the surface of the water. They began now to bite with the greatest eagerness, and gave us all the work that we could do. As soon as I had taken a fish from one line, the other demanded my attention. I did not have to wait for a bite. Indeed, as soon as the hook was thrown into the water, several mackerel would dart for it. As George said, they were very anxious to be caught. This was very different from my previous experience in fishing for trout in the little brooks near my home. I used to fish all day and not get more than two or three trout, and often I would not get one. Those that I did catch were not more than four or five inches long. I guess some of my boy readers have had the same experience.

The only drawback was baiting the hook whenever a fish was taken from it. Uncle James soon remedied this difficulty. He cut from the under side of a dead mackerel six thin pieces, about half an inch in diameter, and gave each of us two. We put them on our hooks, and they served for bait a long time. When they were gone, we put on more of the same kind. Mackerel will bite at any very small object, almost, that they can see, and sometimes fishermen fasten a small silver coin to their hooks, which will do duty as bait for days. They wish to catch as many fish as they possibly can, while they are biting, for mackerel are very notional. Sometimes they will bite so fast as to tire their captors, and, ten minutes after, not one can be felt or seen. Usually, they can be caught best in the morning and toward evening. I suppose they have but two meals a day, breakfast and supper, going without their dinner. In this respect, they resemble trout and many other kinds of fish.

They are caught in great numbers off the coast of Maine and Massachusetts in the months of August and September. Hundreds of schooners, large and small, and thousands of men and boys are employed in the business. Standing upon the shore, near Portland, and looking out upon the Atlantic, on a bright summer's day, you can sometimes see more white, glistening sails of "mackerel-catchers" than you can count. At the wharves of every little village on the sea-shore, or on a river near the shore, boats and fishermen abound. Of late years, immense nets or "seines" have been used, and often, by means of them, enormous quantities of fish have been secured in one haul. The season is short, but most of the fishermen, before the mackerel come and after they go, engage in fishing for cod and hake, which are plentiful also. Mackerel-catching has its joys, but it also has its sorrows and uncertainties. One vessel may have excellent luck while another may be very unfortunate. In short, those engaged in the pursuit of mackerel have to content themselves with "fishermen's luck."

While we were busily fishing, George called my attention to a dark fin, projecting a few inches above the water, and gradually approaching the boat with a peculiar wavy motion. Just before reaching us it sank out of sight. I cast an inquiring glance at my cousin, who said, in a low tone of voice, "A shark!" A feeling of wonder and dread came over me, and doubtless showed itself in my face, for my uncle said, in an assuring voice, "He will not harm us."

The mackerel stopped biting all at once. Our fishing was over. It was now about ten o'clock, and the sun had become warm. Half a mile from us was a small island, with a plenty of grass and a few trees, but no houses. Uncle James proposed that we should row to it, which we gladly did. Its shores were steep and rocky, and we found much difficulty in landing; but at last we got ashore and pulled the boat up after us. Among the rocks we found a quantity of drift-wood; we gathered some, and built a fire. Uncle James produced some bread and crackers from his basket, and, after roasting some of the nice, fat mackerel on sharp sticks before the fire, we sat down to what seemed to us a delicious breakfast. We were in excellent spirits, and George and I cracked jokes and laughed to our hearts' content. After our hunger had been satisfied, we wandered over the island, which we christened Mackerel Island, and, sitting upon a high cliff, watched the seals as they bobbed their heads out of the water, and turned their intelligent, dog-like faces, with visible curiosity, toward us. They did not seem to be at all afraid, for they swam close to the rock upon which we sat. We whistled, and they were evidently attracted by the sound. These seals are numerous in some of the bays on the New England coast. Most of them are small, but occasionally one is seen of considerable size. Their fur is coarse and of little value, but they are sought after by fishermen for the sake of their oil, which commands a ready sale for a good price. After we had got fully rested, we launched our boat, rowed homeward, and soon landed upon the beach.

Once upon a time, there lived on the borders of a forest an old woman named Jehanne, who had an only son, a youth of twenty-one years, who was called Ranier. Where the two had originally come from no one knew; but they had lived in their little hut for many years. Ranier was a wood-cutter, and depended on his daily labor for the support of himself and mother, while the latter eked out their scanty means by spinning. The son, although poor, was not without learning, for an old monk in a neighboring convent had taught him to read and write, and had given him instructions in arithmetic. Ranier was handsome, active and strong, and very much attached to his mother, to whom he paid all the honor and obedience due from a son to a parent.

One morning in spring, Ranier went to his work in the forest with his ax on his shoulder, whistling one of the simple airs of the country as he pursued his way. Striding along beneath the branches of the great oaks and chestnuts, he began to reflect upon the hard fate which seemed to doom him to toil and wretchedness, and, thus thinking, whistled no longer. Presently he sat down upon a moss-covered rock, and laying his ax by his side, let his thoughts shape themselves into words.

"This is a sad life of mine," said Ranier. "I might better it, perhaps, were I to enlist in the army of the king, where I should at least have food and clothing; but I cannot leave my mother, of whom I am the sole stay and support. Must I always live thus,—a poor wood-chopper, earning one day the bread I eat the next, and no more?"

Ranier suddenly felt that some one was near him, and, on looking up, sprang to his feet and removed his cap. Before him stood a beautiful lady, clad in a robe of green satin, with a mantle of crimson velvet on her shoulders, and bearing in her hand a white wand.

"Ranier!" said the unknown, "I am the fairy, Rougevert. I know your history, and have heard your complaint. What gift shall I bestow on you?"

"Beautiful fairy," replied the young man, "I scarcely know what to ask. But I bethink me that my ax is nearly worn out, and I have no money with which to buy another."

The fairy smiled, for she knew that the answer of Ranier came from his embarrassment; and, going to a tree hard by, she tapped on the bark with her wand. Thereupon the tree opened, and she took from a recess in its center, a keen-edged ax with an ashen handle.

"Here," said Rougevert, "is the most excellent ax in the world. With this you can achieve what no wood-chopper has ever done yet. You have only to whisper to yourself what you wish done, and then speak to it properly, and the ax will at once perform all you require, without taxing your strength, and with marvelous quickness."

The fairy then taught him the words he should use, and, promising to farther befriend him as he had need, vanished.

Ranier took the ax, and went at once to the place where he intended to labor for the day. He was not sure that the ax would do what the giver had promised, but thought it proper to try its powers. "For," he said to himself, "the ranger has given me a hundred trees to fell, for each of which I am to receive a silver groat. To cut these in the usual way would take many days. I will wish the ax to fell and trim them speedily, so,"—he continued aloud, as he had been taught by the fairy,—"Ax! ax! chop! chop! and work for my profit!"

Thereupon the ax suddenly leapt from his hands, and began to chop with great skill and swiftness. Having soon cut down, trimmed and rolled a hundred trees together, it returned, and placed itself in the hands of Ranier.

The wood-chopper was very much delighted with all this, and sat there pleasantly reflecting upon his good fortune in possessing so useful a servant, when the ranger of the forest came along. The latter, who was a great lord, was much surprised when he saw the trees lying there.

"How is this?" asked the ranger, whose name was Woodmount. "At this time yesterday these trees were standing. How did you contrive to fell them so soon?"

"I had assistance, my lord," replied Ranier; but he said nothing about the magic ax.

Lord Woodmount hereupon entered into conversation with Ranier, and finding him to be intelligent and prompt in his replies, was much pleased with him. At last he said:

"We have had much difficulty in getting ready the timber for the king's new palace, in consequence of the scarcity of wood-cutters, and the slowness with which they work. There are over twenty thousand trees yet to be cut and hewn, and for every tree fully finished the king allows a noble of fifty groats, although he allows but a groat for the felling alone. It is necessary that they should be all ready within a month, though I fear that is impossible. As you seem to be able to get a number of laborers together, I will allot you a thousand trees, if you choose, should you undertake to have them all ready to be hauled away for the builders' use, within a month's time."

"My lord," answered Ranier, "I will undertake to have the whole twenty thousand ready before the time set."

"Do you know what you say?" inquired the ranger, astonished at the bold proposal.

"Perfectly, my lord," was the reply. "Let me undertake the work on condition that you will cause the forest to be guarded, and no one to enter save they have my written permission. Before the end of the month the trees will be ready."

"Well," said Lord Woodmount, "it is a risk for me to run; but from what you have done already, it is possible you may obtain enough woodmen to complete your task. Yet, beware! If you succeed, I will not only give you twenty thousand nobles of gold, but also appoint you—if you can write, as you have told me—the deputy-ranger here; and for every day less than a month in which you finish your contract I will add a hundred nobles; but, if you fail, I will have you hanged on a tree. When will you begin?"

"To-morrow morning," replied Ranier.

The next morning, before daylight, Ranier took his way to the forest, leaving all his money save three groats with his mother, and, after telling her that he might not return for a day or so, passed the guard that he found already set, and plunged into the wood. When he came to a place where the trees were thickest and loftiest, he whispered to himself what he had to do, and said to the ax: "Ax! ax! chop! chop! and work for my profit." The ax at once went to work with great earnestness, and by night-fall over ten thousand trees were felled, hewn, and thrown into piles. Then Ranier, who had not ceased before to watch the work, ate some of the provisions which he had brought with him, and throwing himself under a great tree, whose spreading boughs shaded him from the moonlight, drew his scanty mantle around him, and slept soundly till sunrise.

The next morning Ranier arose, and looked with delight at the work already done; then, speaking again to the ax, it began chopping away as before.

Now, it chanced that morning that the chief ranger had started to see how the work was being done, and, on reaching the forest, asked the guards if many wood-cutters had entered. They all replied that only one had made his appearance, but he must be working vigorously, since all that morning, and the whole day before, the wood had resounded with the blows of axes. The Lord Woodmount thereupon rode on in great anger, for he thought that Ranier had mocked him. But presently he came to great piles of hewn timber which astonished him much; and then he heard the axes' sound, which astonished him more, for it seemed as though twenty wood-choppers were engaged at once, so great was the din. When he came to where the ax was at work, he thought he saw—and this was through the magic power of the fairy—thousands of wood-cutters, all arrayed in green hose and red jerkins, some felling the trees, some hewing them into square timber, and others arranging the hewn logs into piles of a hundred each, while Ranier stood looking on. He was so angry at the guards for having misinformed him, that he at once rode back and rated them soundly on their supposed untruth. But as they persisted in the story that but one man had passed, he grew angrier than ever. While he was still rating them, Ranier came up.

"Well, my lord," said the latter, "if you will go or send to examine, you will find that twenty thousand trees are already cut, squared, and made ready to be hauled to the king's palace-ground."

The ranger at once rode back into the forest, and, having counted the number of piles, was much pleased, and ordered Ranier to come that day week when the timber would be inspected, and if it were all properly done he would receive the twenty thousand nobles agreed upon.

"Excuse me, my lord," suggested Ranier, "but the work has been done in two days instead of thirty; and twenty-eight days off at a hundred nobles per day makes twenty-two thousand eight hundred nobles as my due."

"True," replied the ranger; "and if you want money now—"

"Oh no!" interrupted Ranier, "I have three groats in my purse, and ten more at home, which will be quite sufficient for my needs."

At this the ranger laughed outright, and then rode away.

At the end of a week, Ranier sought the ranger's castle, and there received not only an order on the king's treasurer for the money, but also the patent of deputy-ranger of the king's forest, and the allotment of a handsome house in which to live. Thither Ranier brought his mother, and as he was now rich, he bought him fine clothing, and hired him servants, and lived in grand style, performing all the duties of his office as though he had been used to it all his life. People noticed, however, that the new deputy-ranger never went out without his ax, which occasioned some gossip at first; but some one having suggested that he did so to show that he was not ashamed of his former condition, folk were satisfied,—though the truth was that he carried the ax for service only.

Now it happened that Ranier was walking alone one evening in the forest to observe whether any one was trying to kill the king's deer, and while there, he heard the clash of swords. On going to the spot whence the noise came, he saw a cavalier richly clad, with his back to a tree, defending himself as he best might, from a half dozen men in armor, each with his visor down. Ranier had no sword, for, not being a knight, it was forbidden him to bear such a weapon; but he bethought him of his ax, and hoped it might serve the men as it had the trees. So he wished these cowardly assailants killed, and when he uttered the prescribed words, the ax fell upon the villains, and so hacked and hewed them that they were at once destroyed. But it seemed to the knight thus rescued that it was the arm of Ranier that guided the ax, for such was the magic of the fairy.

So soon as the assailants had been slain, the ax came back into Ranier's hand, and Ranier went to the knight, who was faint with his wounds, and offered to lead him to his house. And when he examined him fully, he bent on his knee, for he discovered that it was the king, Dagobert, whom he had seen once before when the latter was hunting in the forest.

The king said: "This is the deputy-ranger, Master Ranier. Is it not?"

"Yes, sire!" replied Ranier.

The king laid the blade of his sword on Ranier's shoulder, and said:

"I dub thee knight. Rise up, Sir Ranier! Be trusty, true and loyal."

Sir Ranier arose a knight, and with the king examined the faces of the would-be assassins, who were found to be great lords of the country, and among them was Lord Woodmount.

"Sir Ranier," said the king, "have these wretches removed and buried. The office of chief ranger is thine."

Sir Ranier, while the king was partaking of refreshments at Ranier's house, sent trusty servants to bury the slain. After this, King Dagobert returned to his palace, whence he sent the new knight his own sword, a baldrick and spurs of gold, a collar studded with jewels, the patent of chief ranger of the forest, and a letter inviting him to visit the court.

Now, when Sir Ranier went to court, the ladies there, seeing that he was young and handsome, treated him with great favor; and even the king's daughter, the Princess Isauré, smiled sweetly on him, which, when divers great lords saw, they were very angry, and plotted to injure the new-comer; for they thought him of base blood, and were much chagrined that he should have been made a knight, and be thus welcomed by the princess and the ladies of the court; and they hated him more as the favorite of the king. So they conferred together how to punish him for his good fortune, and at length formed a plan which they thought would serve their ends.

It must be understood that King Dagobert was at that time engaged in a war with King Crimball, who reigned over an adjoining kingdom, and that the armies of the two kings now lay within thirty miles of the forest, and were about to give each other battle. As Sir Ranier, it was supposed, had never been bred to feats of arms, they thought if they could get him in the field, he would so disgrace himself as to lose the favor of the king and the court dames, or be certainly slain. For these lords knew nothing of the adventure of the king in the forest,—all those in the conspiracy having been slain,—and thought that Ranier had either rendered some trifling service to the king, or in some way had pleased the sovereign's fancy. So when the king and some of the great lords of the court were engaged in talking of the battle that was soon to be fought, one of the conspirators, named Dyvorer, approached them, and said:

"Why not send Sir Ranier there, sire; for he is, no doubt, a brave and accomplished knight, and would render great service?"

The king was angry at this, for he knew that Ranier had not been bred to arms, and readily penetrated the purpose that prompted the suggestion. Before he could answer, however, Sir Ranier, who had heard the words of Dyvorer, spoke up and said:

"I pray you, sire, to let me go; for, though I may not depend much upon my lance and sword, I have an ax that never fails me."

Then the king remembered of the marvelous feats which he had seen Ranier perform in his behalf, and he replied:

"You shall go, Sir Ranier; and as the Lord Dyvorer has made a suggestion of such profit, he shall have the high honor of attending as one of the knights in your train, where he will, doubtless, support you well."

At this, the rest laughed, and Dyvorer was much troubled, for he was a great coward. But he dared not refuse obedience.

The next morning, Sir Ranier departed along with the king for the field of battle, bearing his ax with him; and, when they arrived, they found both sides drawn up in battle order, and waiting the signal to begin. Before they fell to, a champion of the enemy, a knight of fortune from Bohemia, named Sir Paul, who was over seven feet in height, and a very formidable soldier, who fought as well with his left hand as with his right, rode forward between the two armies, and defied any knight in King Dagobert's train to single combat.

Then said Dyvorer: "No doubt, here is a good opportunity for Sir Ranier to show his prowess."

"Be sure that it is!" exclaimed Sir Ranier; and he rode forward to engage Sir Paul.

When the Bohemian knight saw only a stripling, armed with a woodman's ax, he laughed. "Is this girl their champion, then?" he asked. "Say thy prayers, young sir, for thou art not long for this world, I promise thee."

But Ranier whispered to himself, "I want me this braggart hewn to pieces, and then the rest beaten;" and added, aloud: "Ax! ax! chop! chop! and work for my profit!" Whereupon the ax leapt forward, and dealt such a blow upon Sir Paul that it pierced through his helmet, and clave him to the saddle. Then it went chopping among the enemy with such force that it cut them down by hundreds; and King Dagobert with his army falling upon them, won a great victory.

Now the magic of the ax followed it here as before, and every looker-on believed he saw Sir Ranier slaying his hundreds. So it chanced when the battle was over, and those were recalled who pursued the enemy, that a group of knights, and the great lords of the court who were gathered around the king, and were discussing the events of the day, agreed as one man, that there never had been a warrior as potent as Sir Ranier since the days of Roland, and that he deserved to be made a great lord. And the king thought so, too. So he created him a baron on the field, and ordered his patent of nobility to be made out on their return, and gave him castles and land; and, furthermore, told him he would grant him any favor more he chose to ask, though it were half the kingdom.

When Dyvorer and others heard this, they were more envious than ever, and concerted together a plan for the ruin of Lord Treefell, for such was Sir Ranier's new title. After many things had been proposed and rejected, Dyvorer said: "The Princess Isauré loves this stripling, as I have been told by my sister, the Lady Zanthe, who attends on her highness. I think he has dared to raise his hopes to her. I will persuade him to demand her hand as the favor the king has promised. Ranier does not know our ancient law, and, while he will fail in his suit, the king will be so offended at his presumption that he will speedily dismiss him from the court."

This plan was greatly approved. Dyvorer sought out Ranier, to whom he professed great friendship, with many regrets for all he might have said or done in the past calculated to give annoyance. As Dyvorer was a great dissembler, and Ranier was frank and unsuspicious, they became very intimate. At length, one day when they were together, Dyvorer said:

"Have you ever solicited the king for the favor he promised?"

And Ranier answered, "No!"

"Then," said Dyvorer, "it is a pity that you do not love the Princess Isauré."

"Why?" inquired Ranier.

"Because," replied Dyvorer, "the princess not only favors you, but, I think, from what my sister Zanthe has said, that the king has taken this mode of giving her to you at her instance."

Ranier knew that the Lady Zanthe was the favorite maiden of the princess, and, as we are easily persuaded in the way our inclinations run, he took heart and determined to act upon Dyvorer's counsel.

About a week afterward, as the king was walking in the court-yard of his palace, as he did at times, he met with Ranier.

"You have never asked of me the favor I promised, good baron," said King Dagobert.

"It is true, your majesty," said Ranier; "but it was because I feared to ask what I most desired."

"Speak," said the king, "and fear not."

Therefore Ranier preferred his request for the hand of the princess.

"Baron," replied the king, frowning, "some crafty enemy has prompted you to this. The daughter of a king should only wed with the son of a king. Nevertheless, there is an ancient law, never fulfilled, since the conditions are impossible, which says that any one of noble birth, who has saved the king's life, vanquished the king's enemies in battle, and built a castle forty cubits high in a single night, may wed the king's daughter. Though you have saved my life and vanquished my enemies, yet you are not of noble birth, nor, were you so, could you build such a castle in such a space of time."

"I am of noble blood, nevertheless," said Ranier, proudly, "although I have been a wood-chopper. My father, who died in banishment, was the Duke of Manylands, falsely accused of having conspired against the late king, your august father; and I can produce the record of my birth. Our line is as noble as any in your realm, sire, and nobler than most."

"If that be true, and I doubt it not," answered King Dagobert, "the law holds good for you. But you must first build a palace where we stand, and that in a single night. So your suit is hopeless."

The king turned and entered the palace, leaving Ranier in deep sorrow, for he thought the condition impossible. As he stood thus, the fairy, Rougevert, appeared.

"Be not downcast," she said; "but build that castle to-night."

"Alas!" cried Ranier, "it cannot be done."

"Look at your ax," returned the fairy. "Do you not see that the back of the blade is shaped like a hammer?"

So she taught Ranier what words to use, and vanished.

When the sun was down, Ranier came to the court-yard, and raising his ax with the blade upward, he said aloud: "Ax! ax! hammer! hammer! and build for my profit!" The ax at once leapt forward with the hammer part downward, and began cracking the solid rock on which the court-yard lay, and shaping it into oblong blocks, and heaping them one on the other. So much noise was made thereby that the warders first, and then the whole court, came out to ascertain the cause. Even the king himself was drawn to the spot. And it seemed to them, all through the magic of the fairy, that there were hundreds on hundreds of workmen in green cloth hose and red leather jerkins, some engaged in quarrying and shaping, and others in laying the blocks, and others in keying arches, and adjusting doors and windows, and making oriels and towers and turrets. And still as they looked, the building arose foot by foot, and before dawn a great stone castle, with its towers and battlements, its portcullis, and its great gate, forty cubits high, stood in the court-yard.

When King Dagobert saw this, he embraced Ranier, continued to him the title of his father, whose ducal estates he restored to the son, and sending for the Princess Isauré, who appeared radiant with joy and beauty, he betrothed the young couple in the presence of the court.

So Ranier and Isauré were married, and lived long and happily; and, on the death of Dagobert, Ranier reigned. As for the ax, that is lost, somehow, and although I have made diligent inquiry, I have never been able to find where it is. Some people think the fairy took it after King Ranier died, and hid it again in a tree; and I recommend all wood-choppers to look at the heart of every tree they fell, for this wonderful ax. They cannot mistake it, since the word "Boldness" is cut on the blade, and the word "Energy" is printed, in letters of gold, on the handle.

A picnic supper on the grass followed the games, and then, as twilight began to fall, the young people were marshaled to the coach-house, now transformed into a rustic theater. One big door was open, and seats, arranged lengthwise, faced the red table-cloths which formed the curtain. A row of lamps made very good foot-lights, and an invisible band performed a Wagner-like overture on combs, tin trumpets, drums, and pipes, with an accompaniment of suppressed laughter.

Many of the children had never seen anything like it, and sat staring about them in mute admiration and expectancy; but the older ones criticised freely, and indulged in wild speculations as to the meaning of various convulsions of nature going on behind the curtain.

While Teacher was dressing the actresses for the tragedy, Miss Celia and Thorny, who were old hands at this sort of amusement, gave a "Potato" pantomime as a side show.

Across an empty stall a green cloth was fastened, so high that the heads of the operators were not seen. A little curtain flew up, disclosing the front of a Chinese pagoda painted on pasteboard, with a door and window which opened quite naturally. This stood on one side, several green trees with paper lanterns hanging from the boughs were on the other side, and the words "Tea Garden," printed over the top, showed the nature of this charming spot.

Few of the children had ever seen the immortal Punch and Judy, so this was a most agreeable novelty, and before they could make out what it meant, a voice began to sing, so distinctly that every word was heard:

Here the hero "took the stage" with great dignity, clad in a loose yellow jacket over a blue skirt, which concealed the hand that made his body. A pointed hat adorned his head, and on removing this to bow he disclosed a bald pate with a black queue in the middle, and a Chinese face nicely painted on the potato, the lower part of which was hollowed out to fit Thorny's first finger, while his thumb and second finger were in the sleeves of the yellow jacket, making a lively pair of arms. While he saluted, the song went on:

Which assertion was proved to be false by the agility with which the "little man" danced a jig in time to the rollicking chorus:

At the close of the dance and chorus, Chan retired into the tea garden, and drank so many cups of the national beverage, with such comic gestures, that the spectators were almost sorry when the opening of the opposite window drew all eyes in that direction. At the lattice appeared a lovely being; for this potato had been pared, and on the white surface were painted pretty pink cheeks, red lips, black eyes, and oblique brows; through the tuft of dark silk on the head were stuck several glittering pins, and a pink jacket shrouded the plump figure of this capital little Chinese lady. After peeping coyly out, so that all could see and admire, she fell to counting the money from a purse, so large her small hands could hardly hold it on the window seat. While she did this, the song went on to explain:

During the chorus to this verse Chan was seen tuning his instrument in the garden, and at the end sallied gallantly forth to sing the following tender strain:

Carried away by his passion, Chan dropped his banjo, fell upon his knees, and, clasping his hands, bowed his forehead in the dust before his idol. But, alas!—

Indeed it was: for, as the doll's basin of real water was cast forth by the cruel charmer, poor Chan expired in such strong convulsions that his head rolled down among the audience. Miss Ki Hi peeped to see what had become of her victim, and the shutter decapitated her likewise, to the great delight of the children, who passed around the heads, pronouncing a "Potato" pantomime "first-rate fun."

Then they settled themselves for the show, having been assured by Manager Thorny that they were about to behold the most elegant and varied combination ever produced on any stage. And when one reads the following very inadequate description of the somewhat mixed entertainment, it is impossible to deny that the promise made was nobly kept.

After some delay and several crashes behind the curtain, which mightily amused the audience, the performance began with the well-known tragedy of "Blue-beard"; for Bab had set her heart upon it, and the young folks had acted it so often in their plays that it was very easy to get up with a few extra touches to scenery and costumes. Thorny was superb as the tyrant with a beard of bright blue worsted, a slouched hat and long feather, fur cloak, red hose, rubber boots, and a real sword which clanked tragically as he walked. He spoke in such a deep voice, knit his corked eyebrows, and glared so frightfully, that it was no wonder poor Fatima quaked before him as he gave into her keeping an immense bunch of keys with one particularly big, bright one, among them.

Bab was fine to see, with Miss Celia's blue dress sweeping behind her, a white plume in her flowing hair, and a real necklace with a pearl locket about her neck. She did her part capitally, especially the shriek she gave when she looked into the fatal closet, the energy with which she scrubbed the tell-tale key, and her distracted tone when she called out: "Sister Anne, O, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?" while her enraged husband was roaring: "Will you come down, madam, or shall I come and fetch you?"

Betty made a captivating Anne,—all in white muslin, and a hat full of such lovely pink roses that she could not help putting up one hand to feel them as she stood on the steps looking out at the little window for the approaching brothers, who made such a din that it sounded like a dozen horsemen instead of two.

Ben and Billy were got up regardless of expense in the way of arms; for their belts were perfect arsenals, and their wooden swords were big enough to strike terror into any soul, though they struck no sparks out of Blue-beard's blade in the awful combat which preceded the villain's downfall and death.

The boys enjoyed this part intensely, and cries of "Go it, Ben!" "Hit him again, Billy!" "Two against one isn't fair!" "Thorny's a match for em." "Now he's down, hurray!" cheered on the combatants, till, after a terrific struggle, the tyrant fell, and with convulsive twitchings of the scarlet legs, slowly expired, while the ladies sociably fainted in each others arms, and the brothers waved their swords and shook hands over the corpse of their enemy.

This piece was rapturously applauded, and all the performers had to appear and bow their thanks, led by the defunct Blue-beard, who mildly warned the excited audience that if they "didn't look out the walls would break down, and then there'd be a nice mess." Calmed by this fear they composed themselves, and waited with ardor for the next play, which promised to be a lively one, judging from the shrieks of laughter which came from behind the curtain.

"Sanch's going to be in it, I know, for I heard Ben say, 'Hold him still; he wont bite,'" whispered Sam, longing to "jounce" up and down, so great was his satisfaction at the prospect, for the dog was considered the star of the company.

"I hope Bab will do something else, she is so funny. Wasn't her dress elegant?" said Sally Folsom, burning to wear a long silk gown and a feather in her hair.

"I like Betty best, she's so cunning, and she peaked out of the window just as if she really saw somebody coming," answered Liddy Peckham, privately resolving to tease mother for some pink roses before another Sunday came.

Up went the curtain at last, and a voice announced "A Tragedy in Three Tableaux." "There's Betty!" was the general exclamation, as the audience recognized a familiar face under the little red hood worn by the child who stood receiving a basket from Teacher, who made a nice mother with her finger up, as if telling the small messenger not to loiter by the way.

"I know what that is!" cried Sally; "it's 'Mabel on Midsummer Day.' The piece Miss Celia spoke; don't you know?"

"There isn't any sick baby, and Mabel had a 'kerchief pinned about her head.' I say it's Red Riding Hood," answered Liddy, who had begun to learn Mary Howitt's pretty poem for her next piece, and knew all about it.

The question was settled by the appearance of the wolf in the second scene, and such a wolf! On few amateur stages do we find so natural an actor for that part, or so good a costume, for Sanch was irresistibly droll in the gray wolf-skin which usually lay beside Miss Celia's bed, now fitted over his back and fastened neatly down underneath, with his own face peeping out at one end, and the handsome tail bobbing gayly at the other. What a comfort that tail was to Sancho, none but a bereaved bow-wow could ever tell. It reconciled him to his distasteful part at once; it made rehearsals a joy, and even before the public he could not resist turning to catch a glimpse of the noble appendage, while his own brief member wagged with the proud consciousness that though the tail did not match the head, it was long enough to be seen of all men and dogs.

That was a pretty picture, for the little maid came walking in with the basket on her arm, and such an innocent face inside the bright hood that it was quite natural the gray wolf should trot up to her with deceitful friendliness, that she should pat and talk to him confidingly about the butter for grandma, and then that they should walk away together, he politely carrying her basket, she with her hand on his head, little dreaming what evil plans were taking shape inside.

The children encored that, but there was no time to repeat it, so they listened to more stifled merriment behind the red table-cloths, and wondered whether the next scene would be the wolf popping his head out of the window as Red Riding Hood knocks, or the tragic end of that sweet child.

It was neither, for a nice bed had been made, and in it reposed the false grandmother, with a ruffled nightcap on, a white gown, and spectacles. Betty lay beside the wolf, staring at him as if just about to say, "Why, grandma, what great teeth you've got!" for Sancho's mouth was half open and a red tongue hung out, as he panted with the exertion of keeping still. This tableau was so very good, and yet so funny, that the children clapped and shouted frantically; this excited the dog, who gave a bounce and would have leaped off the bed to bark at the rioters, if Betty had not caught him by the legs, and Thorny dropped the curtain just at the moment when the wicked wolf was apparently in the act of devouring the poor little girl, with most effective growls.

They had to come out then, and did so, both much disheveled by the late tussle, for Sancho's cap was all over one eye, and Betty's hood was anywhere but on her head. She made her courtesy prettily, however; her fellow-actor bowed with as much dignity as a short night-gown permitted, and they retired to their well-earned repose.

Then Thorny, looking much excited, appeared to make the following request: "As one of the actors in the next piece is new to the business, the company must all keep as still as mice, and not stir till I give the word. It's perfectly splendid! so don't you spoil it by making a row."

"What do you suppose it is?" asked every one, and listened with all their might to get a hint, if possible. But what they heard only whetted their curiosity and mystified them more and more. Bab's voice cried in a loud whisper, "Isn't Ben beautiful?" Then there was a thumping noise, and Miss Celia said, in an anxious tone, "Oh, do be careful," while Ben laughed out as if he was too happy to care who heard him, and Thorny bawled "Whoa!" in a way which would have attracted attention if Lita's head had not popped out of her box, more than once, to survey the invaders of her abode, with a much astonished expression.

"Sounds kind of circusy, don't it?" said Sam to Billy, who had come out to receive the compliments of the company and enjoy the tableau at a safe distance.

"You just wait till you see what's coming. It beats any circus I ever saw," answered Billy, rubbing his hands with the air of a man who had seen many instead of but one.

"Ready? Be quick and get out of the way when she goes off!" whispered Ben, but they heard him and prepared for pistols, rockets or combustibles of some sort, as ships were impossible under the circumstances, and no other "she" occurred to them.

A unanimous "O-o-o-o!" was heard when the curtain rose, but a stern "Hush!" from Thorny kept them mutely staring with all their eyes at the grand spectacle of the evening. There stood Lita with a wide flat saddle on her back, a white head-stall and reins, blue rosettes in her ears, and the look of a much-bewildered beast in her bright eyes. But who the gauzy, spangled, winged creature was, with a gilt crown on its head, a little bow in its hand, and one white slipper in the air, while the other seemed merely to touch the saddle, no one could tell for a minute, so strange and splendid did the apparition appear. No wonder Ben was not recognized in this brilliant disguise, which was more natural to him than Billy's blue flannel or Thorny's respectable garments. He had so begged to be allowed to show himself "just once," as he used to be in the days when "father" tossed him up on bare-backed old General, for hundreds to see and admire, that Miss Celia had consented, much against her will, and hastily arranged some bits of spangled tarletan over the white cotton suit which was to simulate the regulation tights. Her old dancing slippers fitted, and gold paper did the rest, while Ben, sure of his power over Lita, promised not to break his bones, and lived for days on the thought of the moment when he could show the boys that he had not boasted vainly of past splendors.

Before the delighted children could get their breath, Lita gave signs of her dislike to the foot-lights, and, gathering up the reins that lay on her neck, Ben gave the old cry, "Houp-la!" and let her go, as he had often done before, straight out of the coach-house for a gallop round the orchard.

"Just turn about and you can see perfectly well, but stay where you are till he comes back," commanded Thorny, as signs of commotion appeared in the excited audience.

Round went the twenty children as if turned by one crank, and sitting there they looked out into the moonlight where the shining figure flashed to and fro, now so near they could see the smiling face under the crown, now so far away that it glittered like a fire-fly among the dusky green. Lita enjoyed that race as heartily as she had done several others of late, and caracoled about as if anxious to make up for her lack of skill by speed and obedience. How much Ben liked it there is no need to tell, yet it was a proof of the good which three months of a quiet, useful life had done him, that even as he pranced gayly under the boughs thick with the red and yellow apples almost ready to be gathered, he found this riding in the fresh air with only his mates for an audience pleasanter than the crowded tent, the tired horses, profane men, and painted women, friendly as some of them had been to him.

After the first burst was over, he felt rather glad, on the whole, that he was going back to plain clothes, helpful school, and kindly people, who cared more to have him a good boy than the most famous Cupid that ever stood on one leg with a fast horse under him.

"You may make as much noise as you like, now; Lita's had her run and will be as quiet as a lamb after it. Pull up, Ben, and come in; sister says you'll get cold," shouted Thorny, as the rider came cantering round after a leap over the lodge gate and back again.

So Ben pulled up, and the admiring boys and girls were allowed to gather about him, loud in their praises as they examined the pretty mare and the mythological character who lay easily upon her back. He looked very little like the god of love now; for he had lost one slipper and splashed his white legs with dew and dust, the crown had slipped down upon his neck, and the paper wings hung in an apple-tree where he had left them as he went by. No trouble in recognizing Ben, now; but somehow he didn't want to be seen, and, instead of staying to be praised, he soon slipped away, making Lita his excuse to vanish behind the curtain while the rest went into the house to have a finishing-off game of blindman's-buff in the big kitchen.

"Well, Ben, are you satisfied?" asked Miss Celia, as she stayed a moment to unpin the remains of his gauzy scarf and tunic.

"Yes'm, thank you, it was tip-top."

"But you look rather sober. Are you tired, or is it because you don't want to take these trappings off and be plain Ben again?" she said, looking down into his face as he lifted it for her to free him from his gilded collar.

"I want to take 'em off; for somehow I don't feel respectable," and he kicked away the crown he had help to make so carefully, adding with a glance that said more than his words: "I'd rather be 'plain Ben' than any one else, if you'd like to have me."

"Indeed I do; and I'm so glad to hear you say that, because I was afraid you'd long to be off to the old ways, and all I've tried to do would be undone. Would you like to go back, Ben?" and Miss Celia held his chin an instant, to watch the brown face that looked so honestly back at her.

"No, I wouldn't—unless—he was there and wanted me."

The chin quivered just a bit, but the black eyes were as bright as ever, and the boy's voice so earnest, she knew he spoke the truth, and laid her white hand softly on his head, as she answered in the tone he loved so much, because no one else had ever used it to him:

"Father is not there; but I know he wants you, dear, and I am sure he would rather see you in a home like this than in the place you came from. Now go and dress; but, tell me first, has it been a happy birthday?"

"Oh, Miss Celia! I didn't know they could be so beautiful, and this is the beautifulest part of it; I don't know how to thank you, but I'm going to try—" and, finding words wouldn't come fast enough, Ben just put his two arms round her, quite speechless with gratitude; then, as if ashamed of his little outburst, he knelt down in a great hurry to untie his one shoe.

But Miss Celia liked his answer better than the finest speech ever made her, and went away through the moonlight, saying to herself:

"If I can bring one lost lamb into the fold, I shall be the fitter for a shepherd's wife, by and by."

It was some days before the children were tired of talking over Ben's birthday party; for it was a great event in their small world; but, gradually, newer pleasures came to occupy their minds, and they began to plan the nutting frolics which always followed the early frosts. While waiting for Jack to open the chestnut burrs, they varied the monotony of school life by a lively scrimmage long known as "the wood-pile fight."

The girls liked to play in the half-empty shed, and the boys, merely for the fun of teasing, declared that they should not, so blocked up the door-way as fast as the girls cleared it. Seeing that the squabble was a merry one, and the exercise better for all than lounging in the sun or reading in school during recess, Teacher did not interfere, and the barrier rose and fell almost as regularly as the tide.

It would be difficult to say which side worked the harder; for the boys went before school began to build up the barricade, and the girls stayed after lessons were over to pull down the last one made in afternoon recess. They had their play-time first, and, while the boys waited inside, they heard the shouts of the girls, the banging of the wood, and the final crash as the well-packed pile went down. Then, as the lassies came in, rosy, breathless, and triumphant, the lads rushed out to man the breach, and labor gallantly till all was as tight as hard blows could make it.

So the battle raged, and bruised knuckles, splinters in fingers, torn clothes, and rubbed shoes, were the only wounds received, while a great deal of fun was had out of the maltreated logs, and a lasting peace secured between two of the boys.

When the party was safely over, Sam began to fall into his old way of tormenting Ben by calling names, as it cost no exertion to invent trying speeches and slyly utter them when most likely to annoy; Ben bore it as well as he could, but fortune favored him at last, as it usually does the patient, and he was able to make his own terms with his tormentor.

When the girls demolished the wood-pile they performed a jubilee chorus on combs, and tin kettles played like tambourines; the boys celebrated their victories with shrill whistles, and a drum accompaniment with fists on the shed walls. Billy brought his drum, and this was such an addition that Sam hunted up an old one of his little brother's, in order that he might join the drum corps. He had no sticks, however, and, casting about in his mind for a good substitute for the genuine thing, bethought him of bulrushes.

"Those will do first-rate, and there are lots in the ma'sh, if I can only get 'em," he said to himself, and turned off from the road on his way home to get a supply.

Now, this marsh was a treacherous spot, and the tragic story was told of a cow who got in there and sank till nothing was visible but a pair of horns above the mud, which suffocated the unwary beast. For this reason it was called "Cowslip Marsh," the wags said, though it was generally believed to be so named for the yellow flowers which grew there in great profusion in the spring.

Sam had seen Ben hop nimbly from one tuft of grass to another when he went to gather cowslips for Betty, and the stout boy thought he could do the same. Two or three heavy jumps landed him, not among the bulrushes as he had hoped, but in a pool of muddy water where he sank up to his middle with alarming rapidity. Much scared, he tried to wade out, but could only flounder to a tussock of grass and cling there while he endeavored to kick his legs free. He got them out, but struggled in vain to coil them up or to hoist his heavy body upon the very small island in this sea of mud. Down they splashed again, and Sam gave a dismal groan as he thought of the leeches and water-snakes which might be lying in wait below. Visions of the lost cow also flashed across his agitated mind, and he gave a despairing shout very like a distracted "Moo!"

Few people passed along the lane, and the sun was setting, so the prospect of a night in the marsh nerved Sam to make a frantic plunge toward the bulrush island, which was nearer than the main-land, and looked firmer than any tussock around him. But he failed to reach this haven of rest, and was forced to stop at an old stump which stuck up, looking very like the moss-grown horns of the "dear departed." Roosting here, Sam began to shout for aid in every key possible to the human voice. Such hoots and howls, whistles and roars, never woke the echoes of the lonely marsh before, or scared the portly frog who resided there in calm seclusion.

He hardly expected any reply but the astonished "Caw!" of the crow, who sat upon a fence watching him with gloomy interest, and when a cheerful "Hullo, there!" sounded from the lane, he was so grateful that tears of joy rolled down his fat cheeks.

"Come on! I'm in the ma'sh. Lend a hand and get me out!" bawled Sam, anxiously waiting for his deliverer to appear, for he could only see a hat bobbing along behind the hazel-bushes that fringed the lane.

Steps crashed through the bushes, and then over the wall came an active figure, at the sight of which Sam was almost ready to dive out of sight, for, of all possible boys, who should it be but Ben, the last person in the world whom he would like to have see him in his present pitiful plight.

"Is it you, Sam? Well, you are in a nice fix!" and Ben's eyes began to twinkle with mischievous merriment, as well they might, for Sam certainly was a spectacle to convulse the soberest person. Perched unsteadily on the gnarled stump, with his muddy legs drawn up, his dismal face splashed with mud, and the whole lower half of his body as black as if he had been dipped in an inkstand, he presented such a comically doleful object that Ben danced about, laughing like a naughty will-o'-the-wisp who, having led a traveler astray, then fell to jeering at him.

"Stop that or I'll knock your head off," roared Sam, in a rage.

"Come on and do it, I give you leave," answered Ben, sparring away derisively as the other tottered on his perch and was forced to hold tight lest he should tumble off.

"Don't laugh, there's a good chap, but fish me out somehow or I shall get my death sitting here all wet and cold," whined Sam, changing his tone, and feeling bitterly that Ben had the upper hand now.

Ben felt it also, and though a very good natured boy, could not resist the temptation to enjoy this advantage for a moment at least.

"I wont laugh if I can help it, only you do look so like a fat, speckled frog I may not be able to hold in. I'll pull you out pretty soon, but first I'm going to talk to you, Sam," said Ben, sobering down as he took a seat on the little point of land nearest the stranded Samuel.

"Hurry up, then; I'm as stiff as a board now, and it's no fun sitting here on this knotty old thing," growled Sam, with a discontented squirm.

"Dare say not, but 'it is good for you,' as you say when you rap me over the head. Look here, I've got you in a tight place, and I don't mean to help you a bit till you promise to let me alone. Now then!" and Ben's face grew stern with his remembered wrongs as he grimly eyed his discomfited foe.

"I'll promise fast enough if you wont tell any one about this," answered Sam, surveying himself and his surroundings with great disgust.

"I shall do as I like about that."

"Then I wont promise a thing! I'm not going to have the whole school laughing at me," protested Sam, who hated to be ridiculed even more than Ben did.

"Very well; good-night!" and Ben walked off with his hands in his pockets as coolly as if the bog was Sam's favorite retreat.

"Hold on, don't be in such a hurry!" shouted Sam, seeing little hope of rescue if he let this chance go.

"All right!" and back came Ben ready for further negotiations.

"I'll promise not to plague you if you'll promise not to tell on me. Is that what you want?"

"Now I come to think of it, there is one thing more. I like to make a good bargain when I begin," said Ben, with a shrewd air. "You must promise to keep Mose quiet, too. He follows your lead, and if you tell him to stop it he will. If I was big enough I'd make you hold your tongues. I aint, so we'll try this way."

"Yes, yes, I'll see to Mose. Now, bring on a rail, there's a good fellow. I've got a horrid cramp in my legs," began Sam, thinking he had bought help dearly, yet admiring Ben's cleverness in making the most of his chance.

Ben brought the rail, but just as he was about to lay it from the main-land to the nearest tussock, he stopped, saying, with the naughty twinkle in his black eyes again: "One more little thing must be settled first, and then I'll get you ashore. Promise you wont plague the girls either, 'specially Bab and Betty. You pull their hair, and they don't like it."

"Don't neither. Wouldn't touch that Bab for a dollar; she scratches and bites like a mad cat," was Sam's sulky reply.

"Glad of it; she can take care of herself. Betty can't, and if you touch one of her pig-tails I'll up and tell right out how I found you sniveling in the ma'sh like a great baby. So now!" and Ben emphasized his threat with a blow of the suspended rail which splashed the water over poor Sam, quenching his last spark of resistance.

"Stop! I will!—I will!"

"True as you live and breathe!" demanded Ben, sternly binding him by the most solemn oath he knew.

"True as I live and breathe," echoed Sam, dolefully relinquishing his favorite pastime of pulling Betty's braids and asking if she was at home.

"I'll come over there and crook fingers on the bargain," said Ben, settling the rail and running over it to the tuft, then bridging another pool and crossing again till he came to the stump.

"I never thought of that way," said Sam, watching him with much inward chagrin at his own failure.

"I should think you'd written 'Look before you leap,' in your copy-book often enough to get the idea into your stupid head. Come, crook," commanded Ben, leaning forward with extended little finger.

Sam obediently performed the ceremony, and then Ben sat astride one of the horns of the stump while the muddy Crusoe went slowly across the rail from point to point till he landed safely on the shore, when he turned about and asked with an ungrateful jeer:

"Now, what's going to become of you, old Look-before-you-leap?"

"Mud-turtles can only sit on a stump and bawl till they are taken off, but frogs have legs worth something, and are not afraid of a little water," answered Ben, hopping away in an opposite direction, since the pools between him and Sam were too wide for even his lively legs.

Sam waddled off to the brook above the marsh to rinse the mud from his nether man before facing his mother, and was just wringing himself out when Ben came up, breathless but good-natured, for he felt that he had made an excellent bargain for himself and friends.

"Better wash your face; it's as speckled as a tiger-lily. Here's my handkerchief if yours is wet," he said, pulling out a dingy article which had evidently already done service as a towel.

"Don't want it," muttered Sam, gruffly, as he poured the water out of his muddy shoes.

"I was taught to say 'Thanky' when folks got me out of scrapes. But you never had much bringing up, though you do 'live in a house with a gambrel roof,'" retorted Ben, sarcastically quoting Sam's frequent boast; then he walked off, much disgusted with the ingratitude of man.

Sam forgot his manners, but he remembered his promise, and kept it so well that all the school wondered. No one could guess the secret of Ben's power over him, though it was evident that he had gained it in some sudden way, for at the least sign of Sam's former tricks Ben would crook his little finger and wag it warningly, or call out "Bulrushes!" and Sam subsided with reluctant submission, to the great amazement of his mates. When asked what it meant, Sam turned sulky; but Ben had much fun out of it, assuring the other boys that those were the signs and pass-word of a secret society to which he and Sam belonged, and promised to tell them all about it if Sam would give him leave, which, of course, he would not.

This mystery, and the vain endeavors to find it out, caused a lull in the war of the wood-pile, and before any new game was invented something happened which gave the children plenty to talk about for a time.

A week after the secret alliance was formed, Ben ran in one evening with a letter for Miss Celia. He found her enjoying the cheery blaze of the pine-cones the little girls had picked up for her, and Bab and Betty sat in the small chairs rocking luxuriously as they took turns to throw on the pretty fuel. Miss Celia turned quickly to receive the expected letter, glanced at the writing, post-mark and stamp, with an air of delighted surprise, then clasped it close in both hands, saying, as she hurried out of the room:

"He has come! he has come! Now you may tell them, Thorny."

"Tell us what?" asked Bab, pricking up her ears at once.

"Oh, it's only that George has come, and I suppose we shall go and get married right away," answered Thorny, rubbing his hands as if he enjoyed the prospect.

"Are you going to be married?" asked Betty, so soberly that the boys shouted, and Thorny, with difficulty, composed himself sufficiently to explain.

"No, child, not just yet; but sister is, and I must go and see that is all done up ship-shape, and bring you home some wedding-cake. Ben will take care of you while I'm gone."

"When shall you go?" asked Bab, beginning to long for her share of cake.

"To-morrow, I guess. Celia has been packed and ready for a week. We agreed to meet George in New York, and be married as soon as he got his best clothes unpacked. We are men of our word, and off we go. Wont it be fun?"

"But when will you come back again?" questioned Betty, looking anxious.

"Don't know. Sister wants to come soon, but I'd rather have our honeymoon somewhere else,—Niagara, Newfoundland, West Point, or the Rocky Mountains," said Thorny, mentioning a few of the places he most desired to see.

"Do you like him?" asked Ben, very naturally wondering if the new master would approve of the young man-of-all-work.

"Don't I? George is regularly jolly; though now he's a minister, perhaps he'll stiffen up and turn sober. Wont it be a shame if he does?" and Thorny looked alarmed at the thought of losing his congenial friend.

"Tell about him; Miss Celia said you might," put in Bab, whose experience of "jolly" ministers had been small.

"Oh, there isn't much about it. We met in Switzerland going up Mount St. Bernard in a storm, and—"

"Where the good dogs live?" inquired Betty, hoping they would come into the story.

"Yes; we spent the night up there, and George gave us his room; the house was so full, and he wouldn't let me go down a steep place where I wanted to, and Celia thought he'd saved my life, and was very good to him. Then we kept meeting, and the first thing I knew she went and was engaged to him. I didn't care, only she would come home so he might go on studying hard and get through quick. That was a year ago, and last winter we were in New York at uncle's; and then, in the spring, I was sick, and we came here, and that's all."

"Shall you live here always when you come back?" asked Bab, as Thorny paused for breath.

"Celia wants to. I shall go to college, so I don't mind. George is going to help the old minister here and see how he likes it. I'm to study with him, and if he is as pleasant as he used to be we shall have capital times,—see if we don't."

"I wonder if he will want me round," said Ben, feeling no desire to be a tramp again.

"I do, so you needn't fret about that, my hearty," answered Thorny, with a resounding slap on the shoulder which re-assured Ben more than any promises.

"I'd like to see a live wedding, then we could play it with our dolls. I've got a nice piece of mosquito netting for a veil, and Belinda's white dress is clean. Do you s'pose Miss Celia will ask us to hers?" said Betty to Bab, as the boys began to discuss St. Bernard dogs with spirit.

"I wish I could, dears," answered a voice behind them, and there was Miss Celia, looking so happy that the little girls wondered what the letter could have said to give her such bright eyes and smiling lips. "I shall not be gone long, or be a bit changed when I come back, to live among you years I hope, for I am fond of the old place now, and mean it shall be home," she added, caressing the yellow heads as if they were dear to her.

"Oh, goody!" cried Bab, while Betty whispered with both arms round Miss Celia:

"I don't think we could bear to have anybody else come here to live."

"It is very pleasant to hear you say that, and I mean to make others feel so, if I can. I have been trying a little this summer, but when I come back I shall go to work in earnest to be a good minister's wife, and you must help me."

"We will," promised both children, ready for anything except preaching in the high pulpit.

Then Miss Celia turned to Ben, saying, in the respectful way that always made him feel, at least, twenty-five:

"We shall be off to-morrow, and I leave you in charge. Go on just as if we were here, and be sure nothing will be changed as far as you are concerned when we come back."

Ben's face beamed at that; but the only way he could express his relief was by making such a blaze in honor of the occasion that he nearly roasted the company.

Next morning, the brother and sister slipped quietly away, and the children hurried to school, eager to tell the great news that "Miss Celia and Thorny had gone to be married, and were coming back to live here forever and ever."

It is ten years ago to-day since Georgie May and I went to "Captain Kidd's Cave" after sea-urchins. Georgie was a neighbor's child with whom I had played all my short life, and whom I loved almost as dearly as my own brothers. Such a brave, bright face he had, framed by sunny hair where the summers had dropped gold dust as they passed him by. I can see him now as he stood that day on the firm sand of the beach, with his brown eyes glowing and his plump hand brandishing a wooden sword which he himself had made, and painted with gorgeous figures of red and yellow.

"You see, Allie," he was saying, "his name was Saint George, and he was a knight. And so there was a great dragon with a fiery crest. And so he went at him, and killed him; and he married the princess, and they lived happy ever after. I'd have killed him, too, if I'd been there!"

"Could you kill a dragon?" I asked, rather timidly.

"Course I could!" replied the young champion. "I'd have a splendid white horse,—no, a black one,—and a sword like Jack the Giant Killer's, and—and—oh, and an invisible ring! I'd use him up pretty quick. Then I'd cut off his head and give it to the princess, and we'd have a feast of jelly-cake, and cream candy, and then I would marry her!"

I could only gasp admiringly at this splendid vision.

"But mamma said," went on Georgie, more thoughtfully, "that there are dragons now; and she said she would like me to be a Saint George. She's going to tell some more to-night, but there's getting angry, that's a dragon, and wanting to be head of everything, that's another, and she and me are going to fight 'em. We said so."

"But how?" I asked, with wide open eyes. "I don't see any dragon when I'm angry!"

"Oh, you're a girl," said Georgie, consolingly; and we ran on contentedly, wading across the shallow pools of salt water, clambering over the rocks, and now and then stopping to pick up a bright pebble or shell. The whole scene comes vividly before me as I think of it now:—the gray and brown cliffs, with their sharp crags and narrow clefts half choked up by the fine, sifting sand, the wet "snappers" clinging to the rocks along the water's edge; the sea itself clear and blue in the bright afternoon, and the dancing lights where the sunbeams struck its rippling surface. A light wind blew across the bay. It stirred in Georgie's curls, and swept about us both as if playing with us. We grew happier and happier, and when at last we saw "Captain Kidd's Cave" just before us, we were in the wildest spirits, and almost sorry that our walk was ended.

There was plenty to be seen in the cave, however, beside the excitement of searching for the pirate's treasures, which the country people said were buried there. The high rocks met, forming a wide, arched cavern with a little crevice in the roof, through which we could just see the clear sky. The firm floor was full of smaller stones, which we used for seats, and one high crag almost hid the entrance. It was delicious to creep through the low door-way, and to sit in the cool twilight that reigned there, listening to the song of the winds and waters outside, or to clamber up and down the steep sides of the cave, playing that we were cast-aways on a desert island. We played, also, that I was a captive princess, and Georgie killed a score of dragons in my defense. We were married, too, with the little knight's sword stuck in the sand for the clergyman. Quite tired out, at last, we went into the cave and sat on the sand-strewn floor, telling stories and talking of dragons and fairies, until a drop of rain suddenly fell through the cleft in the roof. Georgie sprang up.

"We must go home, Allie!" he cried. "What if we were to be caught in a shower!"

Just as he was speaking, a peal of thunder crashed and boomed right above us, and I clung to the boy, sobbing for very terror.

"O Georgie!" I cried, "don't go out. We'll be killed! Oh, what shall we do?"

But Georgie only laughed blithely, saying, "No, we wont go if you don't want to. Let's play it's a concert and the thunder's a drum. It will be over in a minute," and he began to whistle "Yankee Doodle," in which performance I vainly endeavored to join. But as time went on, and the storm became more violent, we were both frightened, and climbing to a ledge about half-way up the wall, sat silent, clinging to each other, and crying a little as the lightning flashed more and more vividly. Yet, even in his own terror, Georgie was careful for me, and tried to cheer me and raise my heart. Dear little friend, I am grateful for it now!

At last, leaning forward, I saw that the water was creeping into the cave and covering the floor with shallow, foaming waves. Then, indeed, we were frightened. What if the rising tide had covered the rocks outside? We should have to stay all night in that lonely place; for, though the tide went down before midnight, the way was long and difficult, and we could not return in the darkness.

"Hurry, Allie!" cried Georgie, scrambling down the side of the cave. "We can wade, may be."

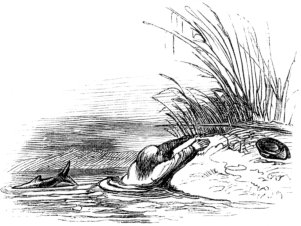

I followed him, and we crept out upon the beach. The water had risen breast high already, and I was nearly thrown down by the force with which it met me.

"Lean on me, Allie," said Georgie, throwing his arm about me and struggling onward. "We must get to the rocks as soon as we can."

It was with great difficulty that we passed over the narrow strip of sand below the high cliffs. I clung wildly to Georgie, trying in vain to keep a firm footing on the treacherous sand, that seemed slipping from beneath my feet at every step.

The water had reached my neck. I cried out with terror as I felt myself borne from my feet. But Georgie kept hold of me, and bracing ourselves against the first low rock, we waited the coming of the great green wave that rolled surging toward us, raising its whitening crest high over our heads. It broke directly above us, and for a moment we stood dizzy with the shock, and half blinded by the dashing salt spray. Then we ran on as swiftly as was possible in the impeding water. Fortunately for us, the next wave broke before it reached us, for in the rapidly rising tide we could not have resisted it.

We were thoroughly exhausted when, after a few more struggles, we at last climbed the first cliff and sat on the top, resting and looking about us for a means of escape. It was impossible for us to scale the precipice that stretched along the beach. We must keep to the lower crags at its foot for a mile before we could reach the firm land. This, in the gathering twilight, was a difficult and dangerous thing to attempt. Yet there was no other way of escape. We could not return to the cave. I shuddered as I looked at the foaming waves that rolled between us and it.

"What shall we do, Georgie?" I cried. "I can't be drowned!"

"Hush, Allie!" answered Georgie, bravely; "we must go right on, of course. This place will be covered soon. Take off your shoes. You can climb easier. There now! take hold of my hand. I'll jump over to that rock and help you to come on, too!"

Well was it for me that Georgie was a strong, agile boy, head and shoulders taller than I. I needed all his help in the homeward journey. I tremble even yet as I think of the perils of the half mile that we traversed before darkness fell. The rough rocks tore our hands and feet as we clambered painfully over them. They were slippery with sea-weed and wet with the waves that from time to time rolled across them. More than once I slipped and would have fallen into the raging water below, but for Georgie's sustaining arm. Looking back now to that dark evening, Georgie's bravery and presence of mind seem wonderful to me. He spoke little, only now and then directing me where to place my feet, but his strong, boyish hand held mine in a firm grasp, and his clear eyes saw just when to seize the opportunity, given by a receding wave, to spring from one rock to another.

"Georgie, shall we ever reach home?" I sighed at last as we gained the end of a spur of rock over which we had been walking. Georgie made no answer, and I turned, in surprise, to look at him. His face was very white, and his great eyes were staring out into the twilight with such a frightened gaze that I looked about me with a sudden increase of terror. I had thought the worst of the way over, and in the gathering darkness had hardly noticed where we were going, following Georgie with perfect trust in his judgment. Now I suddenly saw that we could proceed no farther. We stood, as I have said, on a long ridge of rock. Before us, at our very feet, was the wildly surging water, tearing at the rocks as if to wrest them from their foundation. Beyond, we could see the strong cliffs again, but far out of reach. Behind were only the narrow rocks over which we had come; and on either side the cruel sea cut us off from all hope of gaining the land. I sank on the slippery sea-weed, in an agony of terror, sobbing out my mother's name. Georgie sat down beside me. "Don't cry, Allie!" he said, in a trembling voice. "Please don't! We may be saved yet. Perhaps they'll come after us in a boat. Or we can stay here till morning."

"But oh! I want to go home! I want mamma," I sobbed; "and I'm so cold and tired, and my feet ache so! O Georgie, can't we go on?"