OFFICERS, 1914.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Fifth Leicestershire, by J.D. Hills

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Fifth Leicestershire

A Record Of The 1/5th Battalion The Leicestershire Regiment,

T.F., During The War, 1914-1919.

Author: J.D. Hills

Release Date: December 22, 2005 [EBook #17369]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FIFTH LEICESTERSHIRE ***

Produced by David Clarke, Janet Blenkinship and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

| Transcriber's Note: |

| Many inconsistencies appeared in the original book and were retained in this version. |

With an introduction by

LOUGHBOROUGH.

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED AT THE ECHO PRESS.

1919.

who has watched over us and lived with us

in all our losses and in all our joys,

this book is gratefully dedicated.

No literary merit is claimed for this book. It is intended to be a diary of our progress as a Battalion since mobilisation until the signing of peace, and the return of the Colours to Loughborough. I have written the first chapter, the remainder, including the maps, has been done by Captain J.D. Hills.

This is scarcely the place to attempt an estimate of what the members of our County Territorial Force Association, individually and collectively, have done for the 5th Leicestershire Regiment. We would merely place this on record, that there has ever been one keen feeling of brotherhood uniting us all, from President or Chairman, to the latest joined recruit or humblest member of the regiment, whether actively engaged on the battlefield, or just as actively engaged at home. Never has the Executive Committee failed us. And to Major C.M. Serjeantson, O.B.E., we would offer a special tribute for his untiring work, wonderful powers of organisation and grasp of detail, and hearty good fellowship at all times.

To the men of the regiment we hope that the incidents which we narrate here will recall great times we spent together, and serve as a framework on which to weave other stories too numerous for the short space of one book.

Meadhurst,

Uppingham,

Sept., 1919.

The following narrative is based mainly on the Regimental War Diary. For the rest, my thanks are due to Lt.-Colonels C.H. Jones, C.M.G., T.D., and J. Ll. Griffiths, D.S.O., Major C. Bland, T.D., Captains D.B. Petch, M.C., J.R. Brooke, M.C., and A.D. Pierrepont, and R.Q.M.S. R. Gorse, M.S.M., for sending me notes and anecdotes; to Captains G.E. Banwell, M.C., and C.S. Allen, Corpl. J. Lincoln, and L/Corpl. A.B. Law, for taking me round the battlefields and explaining the Lens fighting of 1917; to 2nd Lieut. G.H. Griffiths, for supplying me with many of the battlefield photographs; to all officers, N.C.O.'s and men of the Battalion who have always been ready to answer my questions and to give me information; to Major D. Hill, M.C., Brigade Major, for the loan of his Brigade documents; and lastly to Mr. Deakin of Loughborough, for undertaking the publication of this book and for giving to it so much time and personal care.

16, Somerset St.,

London, W.1.

Sept., 1919.

| CHAPTER | PAGE. | |

| 1. | England | 1 |

| 2. | Early Experiences | 16 |

| 3. | The Salient | 39 |

| 4. | Hohenzollern | 70 |

| 5. | Flanders Mud to the Mediterranean | 90 |

| 6. | The Vimy Ridge | 106 |

| 7. | Gommecourt | 127 |

| 8. | Monchy au Bois | 145 |

| 9. | Gommecourt Again | 163 |

| 10. | Lens | 179 |

| 11. | Hill 65 | 196 |

| 12. | St. Elie Left | 206 |

| 13. | Cambrin Right | 227 |

| 14. | Gorre and Essars at Peace | 253 |

| 15. | Gorre and Essars at War | 267 |

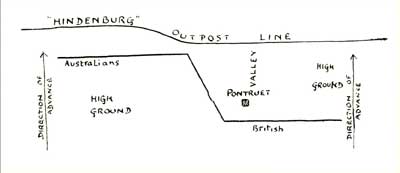

| 16. | Pontruet | 279 |

| 17. | Crossing the Canal | 298 |

| 18. | Fresnoy and Riquerval Woods | 325 |

| 19. | The Last Fight | 352 |

| 20. | Home Again | 372 |

| APPENDIX. | ||

| I. | Officers, Feb., 1915 | 376 |

| II. | Honours | 377 |

| III. | The Cadre, 1919 | 379 |

| PAGE. | ||

| 1. | Officers, 1914 | Frontispiece. |

| 2. | R.S.M.s Small and Lovett, R.Q.M.S. Gorse | 34 |

| 3. | Ypres | 35 |

| 4. | Hohenzollern Memorial | 50 |

| 5. | Vermelles Water Tower | 51 |

| 6. | Lens from the Air | 130 |

| 7. | Officers at Marqueffles | 131 |

| 8. | Red Mill and Riaumont Hill | 146 |

| 9. | Hohenzollern Craters, 1917 | 147 |

| 10. | Company Headquarters, Loisne, and Gorre Canal | 322 |

| 11. | Pontruet | 323 |

| 12. | Lieut. J.C. Barrett, V.C. | 338 |

| 13. | The Cadre at Loughborough | 339 |

| PAGE. | ||

| 1. | Ypres District | 44 |

| 2. | Bethune District | 82 |

| 3. | Attack on Gommecourt, 1/7/16 | 130 |

| 4. | Monchy District | 154 |

| 5. | Lens District | 190 |

| 6. | Attack on Pontruet, 24/9/18 | 286 |

| 7. | Advance, 24/9/18 to 11/11/18 | 314 |

4th Aug., 1914.25th Feb., 1915.

The Territorial Force, founded in 1908, undoubtedly attracted many men who had not devoted themselves previously to military training, nevertheless it took its character and tone from men who had seen long service in the old Volunteer Force. Hence, those who created the Territorial Force did nothing more than re-organise, and build upon what already existed. In the 5th Leicestershire Regiment there crossed with us to France men who had over 30 years' service. At the outbreak of war in 1914, R.Q.M.S. Stimson could look back on 36 years of service, and, amongst other accomplishments he spoke French fluently. Other names that occur to us are Serjt. Heafield, with 28 years, and C.S.M. Hill with 16 years, both of Ashby, and both of whom served in the Volunteer Company in South Africa. R.S.M. Lovett (27 years), of Loughborough, also wears the South African medal for service in the same Company. Then there are Pioneer-Serjt. Clay (27 years' service), C.S.M. Garratt, of Ashby, C.S.M. Wade, of Melton, R.Q.M.S. Gorse, of Loughborough, Signal-Serjeant Diggle, of Hinckley—all long service men. The senior N.C.O. in Rutland was C.S.M. Kernick, who had done 18 years' service when war was declared.

The infantry of the 46th (North Midland) Division[Pg 2] consisted of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, the Lincolnshire and Leicestershire, and the Staffordshire Brigades. Our brigade, the 138th, was commanded at first by General A.W. Taylor, who was succeeded a few days before we left England by General W.R. Clifford. Staff officers changed frequently, and we hope we did not break the hearts of too many. Staff-Captain J.E. Viccars survived most of them, and we owe him much for the able and vigorous assistance he was always ready cheerfully to give us.

The 5th Leicestershire was a County Battalion, organised in eight companies, with headquarters respectively at Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Oakham, Melton Mowbray, Hinckley, Market Harborough, Mountsorrel, Shepshed, and one at Regimental Headquarters at Loughborough. The companies thus were much scattered, and it was only at the annual training camps that we met as a battalion.

The Territorial Force was better prepared for mobilisation than is generally supposed, and if the history of the assembly of the regiment at Loughborough in the first week, their train journey to Duffield in the second week, the purchase of horses, the collection of stores, the requisitions for food and the sharpening of bayonets, be demanded, it can be read in the orders printed many months before war even threatened. The orders were drawn up by Lt.-Colonel G. German, T.D., our former commanding officer, now D.S.O., and by his conscientious and indefatigable adjutant, Captain W.G. King Peirce, who was killed early in the war fighting with his old regiment, the Manchesters. It is due to these officers to record that every detail was studiously followed and found exactly correct. We heard of one[Pg 3] officer who, at the time the printed book of orders was issued, was so fearful lest it should fall into the hands of some indiscreet or improper person, that he packed and sealed it, addressed it to his executors, and locked it up in a safe, so that even sudden death on his part would not force him to betray his trust.

Of all hard-worked people in the early days it is possible that upon Major R.E. Martin fell the greatest share. Not only did he see that supplies were forthcoming, and that dealers delivered the goods expected of them, but he set himself to design water-carts, and troughs-water-feet-for-the-washing-of, and cunningly to adapt stock material to the better service and greater comfort of all, many of whom were for the first time dragged from the civilities and luxuries of home life.

At Loughborough from the 5th to the 11th of August we did little more than pull ourselves together generally, and enjoy the good will of the inhabitants, led by our firm friend, the oft-repeated Mayor, Mr. Mayo, J.P.

It did not demand much wit to foretell that sooner or later we should be asked to offer ourselves for service abroad. The question was put for the first time on the 13th of August, at Duffield. A rough estimate was made that at least 70 per cent. would consent gladly and without further thought, and of the others hesitation was caused in many cases because men wondered whether in view of their positions in civil life they had the right to answer for themselves. It should be understood that a very large number were skilled men, and had joined the home army merely because they thought it a good thing to do. And because they liked it, and knew it was a good thing to do, they were content to accept humble places in a force formed for home service[Pg 4] and home defence only. Also, at that stage it was not perfectly certain that everyone would be wanted, and when the question of war service abroad was raised, and other men were not serving at all, it is only natural that the thought passed through some men's minds that the appeal was not for them. We think that the battalion might be congratulated upon the general spirit of willingness shown, especially as in the 17th August when the question was put again more definitely, the percentage of those ready to extend the terms of service was estimated at 90.

There were other phases of this call for extension of service, too numerous to detail here; for example, on one occasion we were asked to get six companies ready at once. This for a time upset everything, for, as we have said, the original eight companies were taken from different parts of the county, and there was a strong company comradeship, as well as a battalion unity; and if six be taken out of eight it means omissions, amalgamations, grafts, and all sorts of disturbances.

We left Duffield on the 15th of August, and marched to Derby Station. Our train was timed to start at 11 p.m., and seeing that we arrived at Luton at 2 p.m. the next day, the rate of motion was about 6 miles an hour, not too fast for a train. But the truth is we did not start at 11 p.m., but spent hours standing in the cattle yard at Derby, while trucks and guns were being arranged to fit one another. As that was our first experience of such delay, the incident was impressed upon our minds, and it counts one to the number of bars we said our medal should have.

As in Loughborough, so in Luton, our billets were schools. There was one advantage about the Beech[Pg 5] Hill Schools of Luton, namely, that the whole battalion could assemble in the big room, sit on the floor, and listen in comfort to words of instruction and advice. But day schools were not intended for lodging purposes, and here again was displayed Major Martin's skill in the erection of cookhouses and more wash-tubs and other domestic essentials. The moment we got settled, however happened to coincide with the moment at which the education branch of the Town Council determined that the future of a nation depended upon the education of her children, and thus it came to pass that on the 28th of August we moved out of the schools, and entered billets in West Luton.

The long rows of houses were admirably suited to company billets. Occupiers dismantled the ground floor front and took in three, and generally four men at various rates. On the 2nd of October a universal rate of 9d. a day each man was fixed. That made twenty-one shillings a week towards paying off a rent which would average at the most twelve shillings. The billets delighted us, and we hope the owners were as pleased. We thank them and all we met in those billeting times for their kind forbearance.

The headquarters and billets of senior officers were at Ceylon Hall. The building was owned by the Baptists, and we found their committee most willing and obliging. On one occasion they lent us their chapel and organ for a Sunday service, and set their own service at a time to suit ours, when churches in the town could not help us.

Altogether we were in Luton just 3 months training for war. To a great extent the training was on ordinary lines. A routine was followed, and all routines become dull and wearisome. We had been asked to go[Pg 6] abroad, we had expressed our willingness to go. This willingness grew into a desire, which at intervals expressed itself in petulant words of longing—"Are we ever going to France?" The answer was always the same: "You will go soon enough, and you will stay long enough." This increased our irritation. Suddenly, on one still and dark November day, parade was sharply cancelled, we clad ourselves in full marching order, there was just a moment to scrawl on a postcard a few last words home, tender words were exchanged with our friends in the billets, and with heavy tread and in solemn silence we marched forth along the Bedford Road. There was a pillar box beside the road. It was only the leading companies that could put the farewell card actually in the box, for it was quickly crowded out, and in the end the upper portion of the red pillar was visible standing on a conical pile of postcards.

Never had a field day passed without some reference to the 16th milestone on the Bedford Road, but on this particular day orders did not even mention the milestone. This in itself was sufficient to convince us that real war had at length begun. Long before the 16th milestone was sighted, we were diverted into a field, our kit was commented upon, and we marched back to the same old billets. For convenience of reference this incident is entered in our diary as the march to France along the Bedford Road, and no bar was awarded. The march formed a crisis in our history, for subsequent to it leave home was not sought so eagerly. Positively the last words of farewell had been said, and it was difficult to devise other forms of good-bye nearer the absolute ultimate with which to engage our home[Pg 7] friends, who, to our credit be it said, were just as anxious as we were.

It was about this time that our attention was drawn to the anomaly of the discharge rule. A man who had served for four years could take his discharge as a time-expired soldier. At the same time men were enlisting freely. One young man of under 21 was said to have claimed his discharge on the very day that his grandfather, newly enlisted, entered upon three days' "C.B." for coming on parade with dirty boots.

It was in Luton, too, that we overcame our distrust and dislike of vaccination and inoculation against typhoid. We remember C.S.M. Lovett being inoculated in public to give a lead to others, and we smile now to think that in those days it was power of character and leadership only that accomplished things, and incidentally made the way smooth for a Government's compulsory bill.

We were inspected several times, in fact so often that the clause "We are respected by everyone," which comes in our regimental ditty—(and how could it not!!)—was given the alternative rendering "inspected." Twice his Majesty the King honoured us with a visit, and in addition General Ian Hamilton, Lord Kitchener, and others.

Regiments differ much; each has its peculiarities. The 5th Leicestershire a county battalion, if in nothing else, excelled individually in work across country. Though all may not have been as clever as "Pat" Collins (G.A.), who acted as guide to the commanding officer for many months—and we have the commanding officer's permission to add "counsellor and friend"—there was never any difficulty in finding the way in the[Pg 8] day or at night. If we may anticipate our early days in France, a few months hence, we can remember being occupied all one night in extricating parties of men who had lost their way hopelessly in open country in the dark. Those were men who came from a city battalion, brought up amongst labelled thoroughfares, street lamps, and brilliantly-illuminated shop windows. We practised night work at Luton, and all was easy and natural, though we added to our experiences, as on the night when in the thrilling silence of a night attack the fair chestnut bolted with the machine gun; and having kicked two men and lost his character, reverted to the rank of officer's charger.

On a day in October the whole division had entrenched itself in the vicinity of Sharpenhoe and Sundon. To enliven the exercise night manœuvres were hastily planned. Our share was to march at about 11 p.m., after a hard day and half a tea, and to continue marching through the most intricate country until five o'clock the next morning. At that time we were within charging distance of the enemy, and day was breaking. Filing through a railway arch we wheeled into extended order and lay down till all were ready. When the advance was ordered, though we had lain down for two minutes only, the greater number were fast asleep. Despite this hitch the position was taken, and then a march home brought the exercise to an end at 8.10 a.m. For this operation we voted a second bar to our medal.

To those who knew all the details of the plan the most brilliant feature was the wonderfully accurate leading of our Brigade Major, now Brigadier-General Aldercron. He led us behind the advanced posts of the enemy and it was their second line that we attacked.[Pg 9]

Many officers were joining us. Since war had been declared, E.G. Langdale, R.C.L. Mould, C.R. Knighton, S.R. Pullinger, C.H. Wollaston, G.W. Allen, J.D. Hills, and R. Ward-Jackson had all been added to our strength. Later came D.B. Petch, R.B. Farrer, and J. Wyndham Tomson, of whom Petch was straight from school, and he, with the last two named, served a fortnight in France before being gazetted. Their further careers can be followed in later chapters with the exception, perhaps, of Hills, who himself writes those chapters. As his service is a combination of details, many of which are typical of the young officer who fought in the early days of the war, for general information we narrate so much. John David Hills, though not 20, had already seen six years' service in his school O.T.C., including one year as a Cadet Officer. He surrendered his Oxford Scholarship and what that might have meant in order to join up at once. He passed through the battalion from end to end, occupying at various times every possible place: signalling officer, intelligence officer, platoon commander, company commander, adjutant, 2nd in command, and finished up in command of what was called "the cadre." For some time, too, he was attached to the brigade staff, and when we add that he excelled in every position separately and distinctly, and won the admiration and love of all, we may spare him further embarrassment and let the honours he has won speak for him.

Clothing was a lasting trouble. We were now wearing out our first suits, and from time to time there confronted us statements that sounded rather like weather reports, for example—"No trousers to-day;[Pg 10] tunics plentiful." Then the question arose as to whether a man should wear a vest, and, if so, might he have two, one on the man, the other at the wash. Patient endurance was rewarded by an answer in the affirmative to the first part of the question, but the correspondence over the second portion has only just reached the armistice stage.

And as with men, so with animals. "The waggon and horses" sounds beautifully complete as well as highly attractive, but in the army we must not forget to see that harness comes as well. And this thought, the lack of harness, carries us to another great event in our history, the end of the Luton days, the march to Ware.

Why was the march to Ware planned exactly like that? It is not in the hope of getting an answer we ask the question. Waggons and horses and no harness, and whose fault? Waggons and horses with harness, and carrying a double load to make up,—no fault, a necessity. Officers away on leave,—but let us set things down in order. Barely a fortnight after the march to France along the Bedford Road, on Saturday, the 14th of November, a proportion of officers and men went on leave as usual till Monday, and all was calm and still. At 1 a.m. on Monday, orders were received to move at 7 a.m., complete for Ware, a distance, by the route set, of 25 to 30 miles,—some say 50 to 100 miles. Official clear-the-line telegrams were poured out recalling the leave takers. Waggons were packed—(were they not packed!)—billets were cleared, and we toed the line at the correct time. For want of harness, the four cooks' carts and two water carts were left behind; for want of time, meat was issued raw; for[Pg 11] want of orders, no long halt was given at mid-day. One short and sharp bit of hill on the way was too much for the horses, and such regimental transport as we had with us had to be man-handled. This little diversion gave regiments a choice of two systems, gaps between regiments, or gaps between sections of the same regiment, and gave spectators, who had come in considerable numbers, a subject for discussion. But the chief feature of the day was that we reached Ware that day as complete as we started. We arrived at 7-20 p.m. except for two Companies who were detached as rear guard to the Division. The tail end of the Divisional train lost touch and took the wrong turning, and for this reason the two Companies did not come in till 11-30 p.m. We understand that the third bar on our medal will be the march to Ware.

Amongst those who watched us pass near the half-way post we noticed our neighbour, General Sir A.E. Codrington, then commanding the London District, who as an experienced soldier knew the difficulties and gave us, as a regiment, kindly words of praise and encouragement.

We have often wondered what was the verdict of the authorities upon this march. As this is regimental history only, it may be permitted to give the regiment's opinion. We fancied we accomplished passing well an almost impossible task. It is true that not long afterwards we were well fitted out and sent to France. We are persuaded, too, to add here that we said we owed one thing at least to our Divisional Commander, General E. Montagu-Stuart-Wortley; we were the first complete Territorial Force Division to cross the seas and go into action as a Division against the Ger[Pg 12]mans. And it may be that the whole Territorial Force owe to our General, too, that they went in Divisions, and were not sent piecemeal as some earlier battalions, and dovetailed into the Regular Army, or, perhaps, even into the New Army. We live in the assurance that the confidence the Army Council extended to us was not misplaced.

Having rested a day at Ware, we marched to Bishops Stortford, where we cannot say we were billeted neither can we use again the word rest, for the town was over-crowded, and queues were formed up to billets; queues composed of all arms of the service, and infantry did not take the front place. Let us say we were "stationed" there one week. The week was enlivened by strange rumour of German air attacks, and large patrols were kept on the watch at night.

On the 26th of November, the time of our life began when the regiment marched into billets at Sawbridgeworth. The town was built for one infantry regiment and no more. The inhabitants were delightful, and we have heard, indirectly, more than once that they were pleased with us. We soon learnt to love the town and all it contained, and we dare not say that our love has grown cold even now. The wedding bells have already rung for the regiment once at Sawbridgeworth, when Lieut. R.C.L. Mould married Miss Barrett, and we do not know that they may not ring again for a similar reason. In Sawbridgeworth, our vigorous adjutant, Captain W.T. Bromfield, was at his best. Everyone was seized and pulled up to the last notch of efficiency, pay books were ready in time, company returns were faultless, deficiency lists complete, saluting was severer than ever, and echos of heel clicks rattled[Pg 13] from the windows in the street. Best of all were the drums. Daily at Retreat, Drum Sergt. Skinner would salute the orderly officer, the orderly officer would salute the senior officer, then all the officers would salute all the ladies, the crowd would move slowly away, and wheel traffic was permitted once more in the High Street.

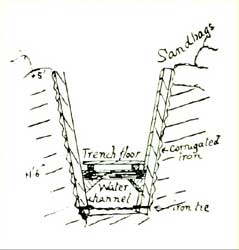

The ordinary routine of military life was broken into at times by sudden and violent efforts dictated by lightning ideas of the Divisional or Brigade Staff, or by the latest news from the front. There was a time, for example, when we could think of one thing only,—the recessed trench. That gave place to the half company trench, a complete system, embracing fire trenches, supports, inspection trenches, with cook houses, wash houses, and all that a well regulated house could require; and so important was it, and its dimensions so precise, that an annotated copy was printed on handkerchiefs.

Then came a sudden desire to cross streams, however swollen, and a party rode off to Bishops Stortford to learn the very latest plans. We had just received a set of beautiful mules, well trained for hard work in the transport. As horses were scarce, and the party large, our resourceful adjutant ordered mules. Several mules returned at once, though many went with their riders to the model bridge, and in their intelligent anxiety to get a really close view, went into the water with them.

On another day we did a great march through Harlow, and saluted Sir Evelyn Wood, V.C., who stood at his gate to see us pass.

Football, boxing and concerts, not to mention dancing, filled our spare time, and there was the famous[Pg 14] race which ended:—Bob, Major Toller, a, 1., Berlin, Capt. Bromfield, a, 2. And we are not forgetting that it was at Sawbridgeworth that we ate our first Christmas war dinner. Never was such a feed. The eight companies had each a separate room, and the Commanding officer, Major Martin, and the adjutant made a tour of visits, drinking the health of each company in turn—eight healths, eight drinks, and which of the three stood it best? Some say the second in command shirked.

Officers had their dinner, too. After the loyal toast there was one only—"Colour Sergt. Joe Collins, and may he live for ever!" The reply was short—"Gentlemen, I think you are all looking very well." It was his only thought, and we were well. We know how much we owe to him as our mess sergeant; he studied our individual tastes and requirements, and kept us well for many months. Good luck to him!

It was not till January, 1915, that a most important, and as a matter of fact the very simplest, change in our organisation was made. To be in keeping with the regular forces, our eight companies were re-organised as four. This system would always have suited our County battalion even in 1908, and our only wonder is that it was not introduced before.

When, on the 18th of February, the G.O.C. returned from a week's visit to France, and gave us a lecture upon the very latest things, we knew we might go at any time. Actually at noon on the 25th we got the order to entrain at Harlow at midnight, and the next morning we were on Southampton Docks.

We left behind at Sawbridgeworth Captain R.S. Goward, now Lieut. Colonel and T.D., in command of[Pg 15] a company which afterwards developed into a battalion called the 3rd 5th Leicestershire. This battalion was a nursery and rest house for officers and men for the 1st Fifth. It existed as a separate unit until the 1st of September, 1916, and during those months successfully initiated all ranks in the ways of the regiment, and kept alive the spirit which has carried us through the Great War.[Pg 16]

26th Feb., 1915.16th June, 1915.

After spending the greater part of the day (the 26th February) lounging about the Hangars at Southampton, we at length embarked late in the afternoon—Headquarters and the right half battalion in S.S. Duchess of Argyle, left half, under Major Martin, in S.S. Atalanta. The transport, under Capt. Burnett, was due to sail later in S.S. Mazaran, since torpedoed in the Channel, but they embarked at the same time as the rest. Four other ships containing Divisional Headquarters and some of the Sherwood Foresters were to sail with us, and at 9 p.m., to the accompaniment of several syrens blowing "Farewell," we steamed out, S.S. Duchess of Argyle leading. The Captain of the ship asked us to post a signaller to read any signals, Serjt. Diggle was told to keep a look out and assist the official signaller, a sort of nondescript Swede or other neutral, like the rest of the crew. We soon sighted some war vessel, and asked if they had any orders, the reply being, according to Serjt. Diggle, "No go"—according to the Swede, "No no." The Captain preferred to believe the latter, and as there were no orders continued his course, though we could see the remainder of our little fleet turn round and sail back. The weather was appalling, the sea very[Pg 17] rough, and long before we had reached half way we were all very ill. This was not surprising, as our transport was built for pleasure work on the Clyde, and, though fast, was never intended to face a Channel storm. Each time a wave crashed into the ship's side we imagined we had been torpedoed; in fact, it was one long night of concentrated misery.

We reached Le Havre in the early hours of the morning, and disembarked, feeling, and probably looking, very bedraggled. From the quay we crawled up a long and terribly steep hill to the rest camp—some lines of tents in a muddy field. Here, while we waited 24 hours for our left half Battalion, of whom we had no news, we were joined by our first interpreter, M. Furby. M. Furby was very anxious to please, but unfortunately failed to realise the terrible majesty of the Adjutant, a fact which caused his almost immediate relegation to the Q.M. Stores, where he always procured the best billets for Capt. Worley and himself. On the morning of the 28th we received an issue of sheepskin coats and extra socks, the latter a present from H.M. the Queen, and after dinners moved down to the Railway Station, where we found Major Martin and the left half. Their experiences in the Channel had been worse than ours. Most of them, wishing to sleep, had started to do so before the ship left Southampton on the 26th; they were almost all ill during the night, so were glad to find a harbour wall outside their port-holes the following morning, and at once went on deck "to look at France"—only to find they were back in Southampton. They stayed there all day, and eventually crossed the next night, arriving on the 28th, feeling as bad as we did, and having had all the horrors of two voyages.[Pg 18]

We were kept waiting many hours on the platform, while the French Railway staff gradually built an enormous train, composed of those wonderful wagons labelled "hommes 36-40, chevaux en long 8," which we now saw for the first time. Hot in summer, cold in winter, always very hard and smelly, and full of refuse, they none the less answered their purpose, and a French troop train undoubtedly carries the maximum number of men in the minimum of accommodation. During this long wait we should all have starved had it not been for the kindness of an English lady, Mrs. Sidney Pitt, who, with other English ladies, served out an unlimited supply of tea and buns to all. Eventually at 5 p.m. our train was ready, and we entrained—all except two platoons, for whom there was no room. The transport was loaded on to flats which were hooked on behind our wagons, and we finally started up country at about 7 o'clock. The train moved slowly northwards all night, stopping for a few minutes at Rouen, and reaching Abbeville just as dawn broke at 7 a.m. Here, amidst a desolation of railway lines and tin sheds, we stayed for half an hour and stretched our cramped limbs, while six large cauldrons provided enough hot tea for all. From this point our progress became slower, and the waits between stations proportionally longer, until at last we reached a small village, where, according to our train orders, we should stop long enough to water horses. This we began to do, when suddenly, without any whistling or other warning, the train moved on, and Major Martin and Captain Burnett, who were with the horses, only just managed to catch the train, and had to travel the next stage on a flat with a limber. At St. Omer we were told where we should detrain, a[Pg 19] fact hitherto concealed from us, and eventually at 2-35 p.m. in a blizzard and snow storm we reached Arneke, detrained at once, and marched about five miles to the little village of Hardifort, where we arrived in the dark.

We were, of course, entirely inexperienced at this time, and in the light of subsequent events, this, our first attempt at billeting, was a most ludicrous performance. The Battalion halted on the road in fours outside the village, at the entrance to which stood a group headed by the C.O. with a note-book; behind him was the Mayor—small, intoxicated and supremely happy, the Brigade Interpreter, M. Löst, with a list of billets, and the Adjutant, angry at having caught a corporal in the act of taking a sly drink. Around them was a group of some dozen small boys who were to act as guides. The Interpreter read out a name followed by a number of officers and men; the C.O. made a note of it and called up the next platoon; the Mayor shouted the name at the top of his voice, waved his arms, staggered, smacked a small boy, and again shouted, at which from three to five small boys would step out and offer to guide the platoon, each choosing a different direction. How we ever found our homes is still a mystery, and yet by 10 p.m. we were all comfortably settled in quarters. We were joined the next morning by the two remaining platoons, 2nd Lieuts. Mould and Farrer.

The billets were slightly re-arranged as soon as daylight enabled us to see where we were, and we soon settled down and made ourselves comfortable, being told that we should remain at Hardifort until the 4th March, when we should go into trenches for a week's instruction with some Regular Division. We had[Pg 20] nothing much to do except recover from the effects of our journey, and this, with good billets and not too bad weather, we soon did. The remainder of our Brigade had not yet arrived, so we were attached temporarily to the Sherwood Foresters, whose 8th Battalion was also absent, and with them on the 4th moved off Eastwards, having the previous day received some preliminary instructions in trench warfare from General Montagu-Stuart-Wortley, who spoke to all the officers.

Preceded by our billeting party, which left at 5 a.m., we marched from Hardifort at 9 a.m., and, passing through Terdeghen, reached the main road at St. Sylvestre Capel, and went along it to Caestre. On the way we met General Smith-Dorrien, our Army Commander, and while the Battalion halted he talked to all the officers, gave us some very valuable hints, and then watched the Battalion march past, having impressed us all with his wonderful kindness and charm of manner. At Caestre we found motor buses waiting for us, and we were glad to see them, for though no one had fallen out, we were somewhat tired after marching nine miles, carrying, in addition to full marching order, blankets, sheepskin coats and some extra warm clothing. The buses took us through Bailleul and Nieppe to Armentières, at that time a town infested with the most appalling stinks and very full of inhabitants, although the front line trenches ran through the eastern suburbs. Having "debussed," we marched to le Bizet, a little village a mile north of the town, and stayed there in billets for the night. During the evening we stood outside our billets, gazed at the continuous line of flares and listened to the rifle fire, imagining in our innocence that there must be a terrific battle with so many lights.[Pg 21]

The next day our instruction started, and for four days we worked hard, trying to learn all we could about trench warfare from the 12th Brigade, to whom we were attached. While some went off to learn grenade throwing, a skilled science in those days when there was no Mills but only the "stick" grenades, others helped dig back lines of defence and learned the mysteries of revetting under the Engineers. Each platoon spent 24 hours in the line with a platoon either of the Essex Regt., King's Own or Lancashire Fusiliers, who were holding the sector from "Plugstreet" to Le Touquet Station. It was a quiet sector except for rifle fire at night, and it was very bad luck that during our first few hours in trenches we lost 2nd Lieut. G. Aked, who was killed by a stray bullet in the front line. There was some slight shelling of back areas with "Little Willies," German field gun shells, but these did no damage, and gave us in consequence a useful contempt for this kind of projectile. Trench mortars were not yet invented, and we were spared all heavy shells, so that, when on the 9th we left Armentières, we felt confident that trenches, though wet and uncomfortable, were not after all so very dreadful, and that, if at any time we should be asked to hold the line, we should acquit ourselves with credit.

Our next home was the dirty little village of Strazeele, which we reached by march route, and where we found Lieut. E.G. Langdale who rejoined us, having finished his disembarkation duties. Here we occupied five large farm houses, all very scattered and very smelly, the smelliest being Battalion Headquarters, called by Major Martin "La Ferme de L'Odeur affreuse." The Signalling officer attempted to link up the farms by[Pg 22] telephone, but his lines, which consisted of the thin enamelled wire issued at the time, were constantly broken by the farmers' manure carts, and the signallers will always remember the place with considerable disgust. One farmer was very pleased with himself, having rolled up some 200 yards of our line under the impression that all thin wire must be German. The rest of the Brigade had now arrived, and the other three Battalions were much annoyed to find that we were already experienced soldiers—a fact which we took care to point out to them on every possible occasion. Our only other amusement was the leg-pulling of some newspaper correspondents, who, as the result of an interview, made Major Martin a "quarry official," and Lieut. Vincent a poultry farmer of considerable repute!

On the 11th March we marched to Sailly sur la Lys, better known as "Sally on the loose," where with the Canadian Division we should be in reserve, though we did not know it, for the battle of Neuve Chapelle. The little town was crowded before even our billeting party arrived, and it was only by some most brazen billet stealing, which lost us for ever the friendship of the Divisional Cyclists, that we were able to find cover for all, while many of the Lincolnshires had to bivouac in the fields. Here we remained during the battle, but though the Canadians moved up to the line, we were not used, and spent our time standing by and listening to the gun fire. A 15" Howitzer, commanded by Admiral Bacon and manned by Marine Artillery, gave us something to look at, and it was indeed a remarkable sight to watch the houses in the neighbourhood gradually falling down as each shell went off. There was also an armoured train which mounted three guns, and gave[Pg 23] us much pleasure to watch, though whether it did any damage to the enemy we never discovered. Finally, on the 16th, having taken no part in the battle, we marched to some farms near Doulieu, and thence on the 19th to a new area near Bailleul, including the hamlets of Nooteboom, Steent-je (pronounced Stench), and Blanche Maison, where we stayed until the end of the month, while the rest of the Brigade went to Armentières for their tours of instruction.

Our new area contained some excellent farm houses, and we were very comfortably billeted though somewhat scattered. The time was mostly spent in training, which consisted then of trench digging and occasionally practising a "trench to trench" attack, with the assistance of gunners and telephonists, about whose duties we had learnt almost nothing in England. General Smith Dorrien came to watch one of these practices, and, though he passed one or two criticisms, seemed very pleased with our efforts. We also carried out some extraordinarily dangerous experiments with bombs, under Captain Ellwood of the Lincolnshires and Lieut. A.G. de A. Moore, who was our first bomb officer. It was just about this time that the Staff came to the conclusion that something simpler in the way of grenades was required than the "Hales" and other long handled types, and to meet this demand someone had invented the "jam tin"—an ordinary small tin filled with a few nails and some explosive, into the top of which was wired a detonator and friction lighter. For practice purposes the explosive was left out, and the detonator wired into an empty tin. Each day lines of men could be seen about the country standing behind a hedge, over which they threw jam tins at imaginary trenches,[Pg 24] the aim and object of all being to make the tin burst as soon as possible after hitting the ground. We were given five seconds fuses, and our orders were, "turn the handle, count four slowly, and then throw." Most soldiers wisely counted four fairly rapidly, but Pte. G. Kelly, of "D" Company, greatly distinguished himself by holding on well past "five," with the result that the infernal machine exploded within a yard of his head, fortunately doing no damage.

All this time we were about nine miles from the line, and were left in peace by the Boche, except for a single night visit from one of his aeroplanes, which dropped two bombs near Bailleul Station and woke us all up. We did not know what they were at the time, so were not as alarmed as we might otherwise have been. In fact "B" Company had a much more trying time when, a few nights later, one of the cows at their billet calved shortly after midnight. The sentry on duty woke Captain Griffiths, who in turn woke the farmer and tried to explain what had happened. All to no purpose, for the farmer was quite unable to understand, and in the end was only made to realise the gravity of the situation by the more general and less scientific explanation that "La vache est malade."

On the 1st April we received a warning order to the effect that the Division would take over shortly a sector of the line South of St. Eloi from the 28th Division, and two days later we marched through Bailleul to some huts on the Dranoutre-Locre road, where we relieved the Northumberland Fusiliers in Brigade support. The same evening the Company Commanders went with the C.O. and Adjutant to reconnoitre the sector of trenches we were to occupy. It rained hard all night, and was[Pg 25] consequently pitch dark, so that the reconnoitring party could see very little and had a most unpleasant journey, returning to the huts at 2 o'clock the next morning (Easter Day), tired out and soaked to the skin. During the day the weather improved, and it was a fine night when at 10 p.m., the Battalion paraded and marched in fours though Dranoutre and along the road to within half a mile of Wulverghem. Here, at "Packhorse" Farm, we were met by guides of the Welsh Regiment (Col. Marden) and taken into the line.

Our first sector of trenches consisted of two disconnected lengths of front line, called trenches 14 and 15, behind each of which a few shelters, which were neither organised for defence nor even splinter-proof, were known as 14 S and 15 S—the S presumably meaning Support. On the left some 150 yards from the front line a little circular sandbag keep, about 40 yards in diameter and known as S.P. 1, formed a Company Headquarters and fortified post, while a series of holes covered by sheets of iron and called E4 dug-outs provided some more accommodation—of a very inferior order, since the slightest movement by day drew fire from the snipers' posts on "Hill 76." As this hill, Spanbroek Molen on the map, which lies between Wulverghem and Wytschaete was held by the Boche, our trenches which were on its slopes were overlooked, and we had to be most careful not to expose ourselves anywhere near the front line, for to do so meant immediate death at the hands of his snipers, who were far more accurate than any others we have met since. To add to our difficulties our trench parapets, which owing to the wet were entirely above ground, were composed only of sandbags, and were in many places not bullet proof.[Pg 26] There were large numbers of small farm houses all over the country (surrounded by their five-months' dead live stock), and as the war had not yet been in progress many months these houses were still recognizable as such. Those actually in the line were roofless, but the others, wonderfully preserved, were inhabited by support Companies, who, thanks to the inactivity of the enemy's artillery, were able to live in peace though under direct observation. In our present sector we found six such farms; "Cookers," the most famous, stood 500 yards behind S.P. 1, and was the centre of attraction for most of the bullets at night. It contained a Company Headquarters, signal office, and the platoon on the ground floor, and one platoon in the attic! Behind this, and partly screened from view, were "Frenchman's" occupied by Battalion Headquarters, "Pond" where half the Reserve Company lived, and "Packhorse" containing the other half Reserve and Regimental Aid Post. This last was also the burying ground for the sector, and rendezvous for transport and working parties. Two other farms—"Cob" and "T"—lay on the Wulverghem Road and were not used until our second tour, when Battalion Headquarters moved into "Cob" as being pleasanter than "Frenchman's," and "Pond" also had to be evacuated, as the Lincolnshires had had heavy casualties there.

The enemy opposite to us, popularly supposed to be Bavarians, seemed content to leave everything by day to his snipers. These certainly were exceptionally good, as we learnt by bitter experience. By night there was greater activity, and rifle bullets fell thickly round Cookers Farm and the surrounding country. There were also fixed rifles at intervals along the enemy's[Pg 27] lines aimed at our communication tracks, and these, fired frequently during the early part of the night, made life very unpleasant for the carrying parties. There were no communication trenches and no light railways, so that all stores and rations, which could be taken by limbers as far as Packhorse Farm only, had to be carried by hand to the front line. This was done by platoons of the support and reserve companies who had frequently to make two or three journeys during the night, along the slippery track past Pond Farm and Cookers Corner—the last a famous and much loathed spot. There were grids to walk on, but these more resembled greasy poles, for the slabs had been placed longitudinally on cross runners, and many of us used to slide off the end into some swampy hole. One of "B" Company's officers was a particular adept at this, and fell into some hole or other almost every night. These parties often managed to add to our general excitement by discovering some real or supposed spy along their route, and on one occasion there was quite a small stir round Cookers Farm by "something which moved, was fired at, and dropped into a trench with a splash, making its escape." A subsequent telephone conversation between "Cracker" Bass and his friend Stokes revealed the truth that the "something" was "a ——y great cat with white eyes."

Like the enemy's, our artillery was comparatively inactive. Our gunners, though from their Observation Posts, "O.P.'s," on Kemmel Hill they could see many excellent targets, were unable to fire more than a few rounds daily owing to lack of ammunition; what little they had was all of the "pip-squeak" variety, and not very formidable. Our snipers were quite incapable of[Pg 28] dealing with the Bavarians, and except for Lieut. A.P. Marsh, who went about smashing Boche loophole plates with General Clifford's elephant gun, we did nothing in this respect.

In one sphere, however, we were masters—namely, patrolling. At Armentières we had had no practice in this art, and our first venture into No Man's Land was consequently a distinctly hazardous enterprise for those who undertook it—2nd Lieut. J.W. Tomson, Corpl. Staniforth, Ptes. Biddles, Tebbutt, and Tailby, all of "A" Company (Toller). Their second night in the line, in 15 trench, this little party crawled between the two halves of a dead cow, and, scrambling over our wire, explored No Man's Land, returning some half hour later. Others followed their lead, and during the whole of our stay in this sector, though our patrols were out almost every night, they never met a German.

We stayed in these trenches for a month, taking alternate tours of four days each with the 4th Lincolnshires (Col. Jessop). We lost about two killed and ten wounded each tour, mostly from snipers and stray bullets, for we did not come into actual conflict with the enemy at all. Amongst the wounded was C.S.M. J. Kernick, of "B" Company, whose place was taken by H.G. Lovett. This company also lost Serjt. Nadin, who was killed a few weeks later.

Although we fought no pitched battles, the month included several little excitements of a minor sort, both in trenches and when out at rest. The first of these was the appearance of a Zeppelin over Dranoutre, where we were billeted. Fortunately only one bomb dropped anywhere near us, and this did no damage; the rest were all aimed at Bailleul and its aerodromes. We all[Pg 29] turned out of bed, and stood in the streets to look at it, while many sentries blazed away with their rifles, forgetting that it was many hundred feet beyond the range of any rifle.

By the middle of April the Staff began to expect a possible German attack, and we "stood to" all night the 15/16th, having been warned that it would be made on our front and that asphyxiating gases would be used—we had, of course, no respirators. Two nights later the 5th Division attacked Hill 60, and for four hours and a quarter, from 4 p.m. to 8-15 p.m., we fired our rifles, three rounds a minute, with sights at 2,500 yards and rifles set on a bearing of 59°, in order to harass the enemy's back areas behind the Hill—a task which later was always given to the machine gunners. In those days it was a rare thing to hear a machine gun at all, and ours scarcely ever fired. A week afterwards, when out at rest, we heard that the second battle of Ypres had begun, and learnt with horror and disgust of the famous first gas attack and its ghastly results. Within a few days the first primitive respirators arrived and were issued; they were nothing but a pad of wool and some gauze, and would have been little use; fortunately we did not know this, and our confidence in them was quite complete. On the 10th May, just before we left the sector, we had a little excitement in the front line. A German bombing party suddenly rushed "E1 Left," a rotten little "grouse-butt" trench only 37 yards from the enemy, and held by the 4th Leicestershires, and succeeded in inflicting several casualties before they made off, leaving one dead behind them. This in itself was not much, but both sides opened rapid rifle fire, and the din was so terrific that supports were[Pg 30] rushed up, reserves "stood to" to counter-attack, and it was nearly an hour before we were able to resume normal conditions. The following day we returned to the huts, where we were joined by 2nd Lieut. L.H. Pearson who was posted to "A" Company; 2nd Lieut. Aked's place had already been filled by Lieut. C.F. Shields from the Reserve Battalion. 2nd Lieut. G.W. Allen, who had been away with measles, also returned to us during April.

Our next stay in the Locre huts can hardly be called a rest. First, on the 12th May, the enemy raided the 4th Lincolnshires in G1 and G2 trenches, where, at "Peckham Corner," they hoped to be able to destroy one of our mine galleries. The raid was preceded by a strong trench mortar bombardment, during which the Lincolnshire trenches were badly smashed about, and several yards of them so completely destroyed that our "A" Company were sent up the next evening to assist in their repair. They stayed in the line for twenty-four hours, returning to the huts at 4 p.m. on the 14th, to find that the rest of the Battalion was about to move to the Ypres neighbourhood. The previous day the German attacks had increased in intensity, and the cavalry who had been sent up to fill the gap had suffered very heavily, among them being the Leicestershire Yeomanry, who had fought for many hours against overwhelming odds, losing Col. Evans-Freke and many others. There was great danger that if these attacks continued, the enemy would break through, and consequently all available troops were being sent up to dig a new trench line of resistance near Zillebeke—the line afterwards known as the "Zillebeke switch." None of us had ever been to the "Salient," but it was a well known and much[Pg 31] dreaded name, and most of us imagined we were likely to have a bad night, and gloomily looked forward to heavy casualties.

Starting at 6-40 p.m., we went by motor bus with four hundred Sherwood Foresters through Reninghelst, Ouderdom, and Vlamertinghe to Kruisstraat, which we reached in three hours. Hence guides of the 4th Gordons led us by Bridge 16 over the Canal and along the track of the Lille Road. It was a dark night, and as we stumbled along in single file, we could see the Towers of Ypres smouldering with a dull red glow to our left, while the salient front line was lit up by bursting shells and trench mortars. Our route lay past Shrapnel Corner and along the railway line to Zillebeke Station, and was rendered particularly unpleasant by the rifle fire from "Hill 60" on our right. The railway embankment was high and we seemed to be unnecessarily exposing ourselves by walking along the top of it, but as the guides were supposed to know the best route we could not interfere. At Zillebeke Church we found Colonel Jones, who came earlier by car, waiting to show us our work which we eventually started at midnight; as we had to leave the Church again at 1 a.m., to be clear of the Salient before daylight, we had not much time for work. However, so numerous were the bullets that all digging records were broken, especially by the Signallers, whose one desire, very wisely, was to get to ground with as little delay as possible, and when we left our work, the trench was in places several feet deep. The coming of daylight and several salvoes of Boche shells dissuaded us from lingering in the Salient, and, after once more stumbling along the Railway Line, we reached our motor buses and returned to the huts,[Pg 32] arriving at 5-30 a.m. A May night is so short, that the little digging done seemed hardly worth the casualties, but perhaps we were not in a position to judge.

Two days later we went into a new sector, trenches on the immediate left of the last Brigade sector, and previously held by the Sherwood Foresters. The front line consisting of trenches "F4, 5 and 6," "G1 and 2", was more or less continuous, though a gap between the "F's" and "G's," across which one had to run, added a distinct element of risk to a tour round the line. The worst part was Peckham Corner, where the Lincolnshires had already suffered; for it was badly sighted, badly built, and completely overlooked by the enemy's sniping redoubt on "Hill 76." In addition to this it contained a mine shaft running towards the enemy's lines, some 40 yards away, and at this the Boche constantly threw his "Sausages," small trench mortars made of lengths of stove piping stopped at the ends. It was also suspected that he was counter-mining. In this sector three Companies were in the front line, the fourth lived with Battalion Headquarters, which were now at Lindenhoek Châlet near the cross roads, a pretty little house on the lower slopes of Mont Kemmel. Though the back area was better, the trenches on the whole were not so comfortable as those we had left, and during our first tour we had reason to regret the change. First, 2nd Lieut. C.W. Selwyn, taking out a patrol in front of "F5," was shot through both thighs, and, though wonderfully cheerful when carried in, died a few days later at Bailleul. The next morning, while looking at the enemy's snipers' redoubt, Captain J. Chapman, 2nd in Command of "D" Company, was shot through the head, and though he lived for a few days, died soon[Pg 33] after reaching England. This place was taken by Lieut. J.D.A. Vincent, and at the same time Lieut. Langdale was appointed 2nd in Command of "C." There were also other changes, for Major R.E. Martin was given Command of the 4th Battalion, and was succeeded as 2nd in Command by Major W.S.N. Toller, while Captain C. Bland became skipper of "A" Company.

During this same tour, the Brigade suffered its first serious disaster, when the enemy mined and blew up trench "E1 left," held at the time by the 5th Lincolnshire Regiment. This regiment had many casualties, and the trench was of course destroyed, while several men were buried or half-buried in the débris, where they became a mark for German snipers. To rescue one of these, Lieut. Gosling, R.E., who was working in the G trenches, went across to E1, and with the utmost gallantry worked his way to the mine crater. Finding a soldier half buried, he started to dig him out, and had just completed his task when he fell to a sniper's bullet and was killed outright. As at this time the Royal Engineers' Tunnelling Companies were not sufficient to cover the whole British front, none had been allotted to this, which was generally considered a quiet sector. Gen. Clifford, therefore, decided to have his own Brigade Tunnellers, and a company was at once formed, under Lieut. A.G. Moore, to which we contributed 24 men, coalminers by profession. Lieut. Moore soon got to work and, so well did the "amateurs" perform this new task, that within a few days galleries had been started, and we were already in touch with the Boche underground. In an incredibly short space of time, thanks very largely to the personal efforts of Lieut. Moore, who spent hours every day down below within a [Pg 34]few feet of the enemy's miners, two German mine-shafts and their occupants were blown in by a "camouflet," and both E1 left and E1 right were completely protected from further mining attacks by a defensive gallery along their front. For this Lieut. Moore was awarded a very well deserved Military Cross.

After the second tour in this sector we again made a slight change in the line, giving up the "F" trenches and taking instead "G3", "G4," "G4a," "H1," "H2" and "H5," again relieving the Sherwood Foresters, who extended their line to the left. Unfortunately, they still retained the Doctor's House in Kemmel as their Headquarters, and, as Lindenhoek Châlet was now too far South, Colonel Jones had to find a new home in the village, and chose a small shop in one of the lesser streets. We had scarcely been 24 hours in the new billet when, at mid-day, the 4th June, the Boche started to bombard the place with 5.9's, just when Colonel Jessop, of the 4th Lincolnshires, was talking to Colonel Jones in the road outside the house, while an orderly held the two horses close by. The first shell fell almost on the party, killing Colonel Jessop, the two orderlies, Bacchus and Blackham, and both horses. Colonel Jones was wounded in the hand, neck and thigh, fortunately not very seriously, though he had to be sent at once to England, having escaped death by little short of a miracle. His loss was very keenly felt by all of us, for ever since we had come to France, he had been the life and soul of the Battalion, and it was hard to imagine trenches, where we should not receive his daily cheerful visit. We had two reassuring thoughts, one that the General had promised to keep his command open for him as soon as he should[Pg 35] return, the second that during his absence we should be commanded by Major Toller, who had been with us all the time, and was consequently well known to all of us.

Meanwhile we had considerably advanced in our own esteem by having become instructors to one of the first "New Army" Divisions to come to France, the 14th Light Infantry Division, composed of three battalions of Rifle Brigade and 60th, and a battalion of each of the British Light Infantry Regiments. They were attached to us, just as we had been attached to the 12th Brigade at Armentières, to learn the little details of Trench warfare that cannot be taught at home, and their platoons were with us during both our tours in the "G's" and "H's." They were composed almost entirely of officers and men who had volunteered in August, 1914, and their physique, drill and discipline were excellent—a fact which they took care to point out to everybody, adding generally that they had come to France "not to sit in trenches, but to capture woods, villages, etc." We listened, of course, politely to all this, smiled, and went on with our instructing. Many stories are told of the great pride and assurance of our visitors, one of the most amusing being of an incident which happened in trench "H2." Before marching to trenches the visiting Platoon Commander had, in a small speech to his platoon, told them to learn all they could from us about trenches, but that they must remember that we were not regulars, and consequently our discipline was not the same as theirs. All this and more he poured into the ears of his host in the line, until he was interrupted by the entry of his Platoon Sergeant to report the accidental wounding of Pte. X by Pte. Y, who fired a round when cleaning his rifle. There was no need for[Pg 36] the host to rub it in, he heard no more about discipline.

Credit, however, must be given where credit is due, and the following tour our visitors distinguished themselves. On the 15th June, at 9.10 p.m., when the night was comparatively quiet, the enemy suddenly blew up a trench on our left, held by the Sherwood Foresters, at the same time opening heavy rifle fire on our back areas and shelling our front line. Captain Griffiths, who held our left flank with "B" Company, found that his flank was in the air, so very promptly set about moving some of his supports to cover this flank, and soon made all secure. Meanwhile Lieut. Rosher, machine gun officer of the visiting Durham Light Infantry, hearing the terrific din and gathering that something out of the ordinary was happening, though he did not know what, slung a maxim tripod over his shoulders, picked up a gun under each arm, and went straightaway to the centre of activity—a feat not only of wonderful physical strength, but considerable initiative and courage. We did not suffer heavy casualties, but 2nd Lieut. Mould's platoon had their parapet destroyed in one or two places, and had to re-build it under heavy fire, in which Pte. J.H. Cramp, the Battalion hairdresser, distinguished himself. Except for this one outburst on the part of the Boche we had a quiet time, though Peckham Corner was always rather a cause of anxiety, for neither R.E. nor the Brigade Tunnellers could spare a permanent party on the mine shaft. Consequently, it was left to the Company Commander to blow up the mine, and with it some of the German trench, in case of emergency, and it was left to the infantry to supply listeners down the shaft to listen for counter-mining. On one occasion when Captain Bland took over the trench with "A"[Pg 37] Company, he found the pump out of order, the water rising in the shaft, and the gallery full of foul air, all of which difficulties were overcome without the R.E.'s help, by the courage and ingenuity of Serjeant Garratt.

There was one remarkable feature of the whole of this period of the war which cannot be passed over, and that was the very decided superiority of our Flying Corps. During the whole of our three months in the Kemmel area we never once saw a German aeroplane cross our lines without being instantly attacked, and on one occasion we watched a most exciting battle between two planes, which ended in the German falling in flames into Messines, at which we cheered, and the Boche shelled us. Towards the end of the war the air was often thick with aeroplanes of all nationalities and descriptions, but in those days, before bombing flights and battle squadrons had appeared, it was seldom one saw as many as eight planes in the air at a time, and tactical formations either for reconnaissance or attack seemed to be unknown; it was all "one man" work, and each one man worked well.

On the night of the 16th June the Battalion came out of trenches and marched to the Locre huts for the last time, looking forward to a few days' rest in good weather before moving to the Salient, which we were told was shortly to be our fate. We had been very fortunate in keeping these huts as our rest billets throughout our stay in the sector, for though a wooden floor is not so comfortable as a bed in a billet, the camp was well sited and very convenient. The Stores and Transport were lodged only a few yards away at Locrehof Farm, and Captain Worley used to have everything ready for us when we came out of the line.[Pg 38] During the long march back from trenches, we could always look forward to hot drinks and big fires waiting for us at the huts, while there was no more inspiring sight for the officers than Mess Colour-Sergeant J. Collins' cheery smile, as he stirred a cauldron of hot rum punch. Bailleul was only two miles away, and officers and men used often to ride or walk into the town to call on "Tina," buy lace, or have hot baths (a great luxury) at the Lunatic Asylum. Dividing our time between this and cricket, for which there was plenty of room around the huts, we generally managed to pass a very pleasant four or six days' rest.[Pg 39]

22nd June, 1915.1st Oct., 1915.

On the 22nd June, 1915, after resting for five days in the Huts, where General Ferguson, our Corps Commander, came to say good-bye, we marched at 9.0 p.m. to Ouderdom, while our place in the line was taken by the 50th Northumbrian Territorial Division, who had been very badly hammered, and were being sent for a rest to a quiet sector. At Ouderdom, which we reached about midnight, we discovered that our billets consisted of a farm house and a large field, not very cheering to those who had expected a village, or at least huts, but better than one or two units who had fields only, without the farm. It was our first experience in bivouacs, but fortunately a fine night, so we soon all crawled under waterproof sheets, and slept until daylight allowed us to arrange something more substantial. The next day, with the aid of a few "scrounged" top poles and some string, every man made himself some sort of weather-proof hutch, while the combined tent-valises of the officers were grouped together near the farm, which was used as mess and Quartermaster's Stores. Unfortunately, we had no sooner made ourselves really comfortable than the Staffordshires claimed the field as part of their area, and we had to move to a similar[Pg 40] billeting area a few hundred yards outside Reninghelst where we stayed until the 28th. The weather remained hot and fine, except for two very heavy showers in the middle of one day, when most of the officers could be seen making furious efforts to dig drains round their bivouacs from inside, while the other ranks stood stark naked round the field and enjoyed the pleasures of a cold shower-bath. We spent our time training and providing working parties, one of which, consisting of 400 men under Capt. Jeffries, for work at Zillebeke, proved an even greater fiasco than its predecessor in May. For on this occasion, not only was the night very short, but the guides failed to find the work, and the party eventually returned to bivouacs, having done nothing except wander about the salient for three hours. Two days before we left Reninghelst the first reinforcements arrived for us, consisting of 12 returned casualties and 80 N.C.O.'s and men from England—a very welcome addition to our strength.

The time eventually arrived for us to go into the line, and on the 29th the officers went up by day to take over from the Sherwood Foresters, while the remainder of the Battalion followed as soon as it was dark. Mud roads and broad cross-country tracks brought us over the plain to the "Indian Transport Field," near Kruisstraat White Chateau, still standing untouched because, it was said, its peace-time owner was a Boche. Leaving the Chateau on our right, and passing Brigade Headquarters Chalet on our left, we kept to the road through Kruisstraat as far as the outskirts of Ypres, where a track to the right led us to Bridge 14 over the Ypres-Comines Canal. Thence, by field tracks, we crossed the Lille road a few yards north of Shrapnel Corner, and leaving[Pg 41] on our left the long, low, red buildings of the "Ecole de Bienfaisance," reached Zillebeke Lake close to the white house at the N.W. corner. The lake is triangular and entirely artificial, being surrounded by a broad causeway, 6 feet high, with a pathway along the top. On the western edge the ground falls away, leaving a bank some twenty feet high, in which were built the "Lake Dug-outs,"—the home of one of the support battalions. From the corner house to the trenches there were two routes, one by the south side of the Lake, past Railway Dug-outs—cut into the embankment of the Comines Railway—and Manor Farm to Square Wood; the other, which we followed, along the North side of the Lake, where a trench cut into the causeway gave us cover from observation from "Hill 60." At Zillebeke we left the trench, and crossed the main road at the double, on account of a machine gun which the Boche kept at the "Hill 60" end of it, and kept moving until past the Church—another unpleasant locality. Thence a screened track led to Maple Copse, an isolated little wood with several dug-outs in it, and on to Sanctuary Wood, which we found 400 yards further East. Here in dug-outs lived the Supports, for whom at this time was no fighting accommodation except one or two absurdly miniature keeps. At the corner of the larger wood we passed the Ration Dump, and then, leaving this on our left, turned into Armagh Wood on our right.

From the southern end of Zillebeke village two roads ran to the front line. One, almost due South, kept close to the railway and was lost in the ruins of Zwartelen village on "Hill 60"; the other, turning East along a ridge, passed between Sanctuary and Armagh[Pg 42] Woods, and crossed our front line between the "A" and "B" trenches, the left of our new sector. The ridge, called Observatory, on account of its numerous O.P.'s, was sacred to the Gunners, and no one was allowed to linger there, for fear of betraying these points of vantage. Beyond it was a valley, and beyond that again some high ground N.E. of the hill, afterwards known as Mountsorrel, on account of Colonel Martin's Headquarters, which were on it. The line ran over the top of this high ground, which was the meeting place of the old winter trenches (numbered 46 to 50) on the right, and, on the left the new trenches "A," "B," etc., built for our retirement during the 2nd Battle. The 5th Division held the old trenches, we relieved the Sherwood Foresters in the new "A1" to "A8," with three companies in the line and only one in support. The last was near Battalion Headquarters, called Uppingham in Colonel Jones' honour, which were in a bank about 200 yards behind the front line. Some of the dug-outs were actually in the bank, but the most extraordinary erection of all was the mess, a single sandbag thick house, built entirely above ground, and standing by itself, unprotected by any bank or fold in the ground, absolutely incapable, of course, of protecting its occupants from even an anti-aircraft "dud."

We soon discovered during our first tour the difference between the Salient and other sectors of the line, for, whereas at Kemmel we were rarely shelled more than once a day, and then only with a few small shells, now scarcely three hours went by without some part of the Battalion's front being bombarded, usually with whizz-bangs. The Ypres whizz-bang, too, was a thing one could not despise. The country round Klein Zillebeke[Pg 43] was very close, and the Boche was able to keep his batteries only a few hundred yards behind his front line, with the result that the "Bang" generally arrived before the whizz. "A6" and "A7" suffered most, and on the 1st July Captain T.C.P. Beasley, commanding "C" Company, and Lieut. A.P. Marsh, of "B" Company, were both wounded, and had to be sent away to Hospital some hours later. The same night we gave up these undesirable trenches, together with "A5" and "A8" to the 4th Battalion, and took instead "49," "50" and the Support "51" from the Cheshires of the 5th Division. These trenches were about 200 yards from the enemy except at the junction of "49" and "50," where a small salient in his line brought him to within 80 yards. The sniping here was as deadly as at Kemmel, though round the corner in "A1" we could have danced on the parapet and attracted no attention. On the other hand "49" and "50" were comfortably built, whereas "A1" was shallow and narrow and half filled with tunnellers' sandbags, for it contained three long mine shafts, two of which were already under the German lines. "A2," "3" and "4" were the most peaceful of our sector, and the only disturbance here during the tour was when one of a small burst of crumps blew up our bomb store and blocked the trench for a time. This was on the 5th, and after it we were left in peace, until, relieved by the Staffordshires, we marched back to Ouderdom, feeling that we had escaped from our first tour in the ill-famed salient fairly cheaply. Even so, we had lost two officers and 24 O. Ranks wounded, and seven killed, a rate which, if kept up, would soon very seriously deplete our ranks.

On reaching Ouderdom, we found that some huts on[Pg 44] [Pg 45]the Vlamertinghe road had now been allotted us instead of our bivouac field, and as on the following day it rained hard, we were not sorry. Our satisfaction, however, was short-lived, for the hut roofs were of wood only, and leaked in so many places that many were absolutely uninhabitable and had to be abandoned. At the same time some short lengths of shelter trench which we had dug in case of shelling were completely filled with water, so that anyone desiring shelter must needs have a bath as well. This wet weather, coupled with a previous shortage of water in the trenches, and the generally unhealthy state of the salient, brought a considerable amount of sickness and slight dysentry, and although we did not send many to Hospital, the health of the Battalion on the whole was bad, and we seemed to have lost for the time our energy. Probably a fortnight in good surroundings would have cured us completely, and even after eight days at rest we were in a better state, but on the 13th we were once more ordered into the line and the good work was undone, for the sickness returned with increased vigour.

Between the Railway Cutting at "Hill 60" and the Comines Canal further south, the lines at this time were very close together, and at one point, called Bomb Corner, less than 50 yards separated our parapet from the Boche's. This sector, containing trenches "35" at Bomb Corner, "36" and "37" up to the Railway, was held by the 1st Norfolks of the 5th Division, who were finding their own reliefs, and, with one company resting at a time, had been more than two months in this same front line. On the 11th July the Boche blew a mine under trench "37" doing considerable damage to the parapet, and on the following night "36" was[Pg 46] similarly treated, and a length of the trench blotted out. The night after this we came in to relieve the Norfolks, who not unnaturally were expecting "35" to share the same fate, and had consequently evacuated their front line for the night, while they sat in the second line and waited for it to go up in the air. Captain Jefferies with "D" Company took over "35," while the two damaged trenches were held by "B" Company (Capt. J.L. Griffiths). "A" and "C" held a keep near Verbranden Molen—an old mill about three hundred yards behind our front line—and Battalion Headquarters lived in some dug-outs in the woods behind "35." Behind this again, the solitary Blaupoort Farm provided R.A.P. and ration dump with a certain amount of cover, though the number of dud shells in the courtyard made it necessary to walk with extreme caution on a dark night. In spite of the numerous reports of listening-posts, who heard "rapping underground," we were not blown up during our four days in residence, and our chief worry was not mines, but again whizz-bangs. One battery was particularly offensive, and three times on the 15th Capt. Griffiths had his parapet blown away by salvoes of these very disagreeable little shells. One's parapet in this area was one's trench, for digging was impossible, and we lived behind a sort of glorified sandbag grouse butt, six feet thick at the base and two to three feet at the top, sometimes, but not always, bullet-proof.

One or two amusing stories are told about the infantry opposite "33," who were Saxons, and inclined to be friendly with the English. On one occasion the following message, tied to a stone, was thrown into our trench: "We are going to send a 40lb. bomb. We have got to do it, but don't want to. I will come this[Pg 47] evening, and we will whistle first to warn you." All of this happened. A few days later they apparently mistrusted the German official news, for they sent a further message saying, "Send us an English newspaper that we may learn the verity."