![Captain R. Hugh Knyvett.]](images/img-front.jpg)

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: "Over There" with the Australians

Author: R. Hugh Knyvett

Release Date: December 3, 2005 [eBook #17206]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK "OVER THERE" WITH THE AUSTRALIANS***

![Captain R. Hugh Knyvett.]](images/img-front.jpg)

(Bill-Jim is Australia's name for her soldier)

Here where I sit, mucked-up with Flanders mud,

Wrapped-round with clothes to keep the Winter out,

Ate-up wi' pests a bloke don't care to name

To ears polite,

I'm glad I'm here all right;

A man must fight for freedom and his blood

Against this German rout

An' do his bit,

An' not go growlin' while he's doin' it:

The cove as can't stand cowardice or shame

Must play the game.

Here's Christmas, though, with cold sleet swirlin' down…

God! gimme Christmas day in Sydney town!

I long to see the flowers in Martin Place,

To meet the girl I write to face to face,

To hold her close and teach

What in this Hell I'm learning—that a man

Is only half a man without his girl,

That sure as grass is green and God's above

A chap's real happiness,

If he's no churl,

Is home and folks and girl,

And all the comforts that come in with love!

There is a thrill in war, as all must own,

The tramplin' onward rush,

The shriek o' shrapnel and the followin' hush,

The bosker crunch o' bayonet on bone,

The warmth of the dim dug-out at the end,

The talkin' over things, as friend to friend,

And through it all the blessed certainty

As this war's working out for you an' me

As we would have it work.

Fritz maybe, and the Turk

Feel that way, too,

The same as me an' you,

And dream o' victory at last, although

The silly cows don't know,

Because they ain't been born and bred clean-free,

Like you and me.

But this is Christmas, and I'm feeling blue,

An' lonely, too.

I want to see one little girl's sly pout

(There's lots of other coves as feels like this)

That holds you off and still invites a kiss.

I want to get out from this smash and wreck

Just for to-day,

And feel a pair of arms slip round me neck

In that one girl's own way.

I want to hear the splendid roar and shout

O' breakers comin' in on Bondi Beach,

While she, with her old scrappy costume on,

Walks by my side, an' looks into my face,

An' makes creation one big pleasure-place

Where golden sand basks in that golden weather—

Yes! her an' me together!

I do me bit,

An' make no fuss of it;

But for to-day I somehow want to be

At home, just her an' me.

(From the Sydney "Sunday Times")

| An Introduction Mainly About Scouts |

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | The Call Reaches Some Far-Out Australians |

| II. | An All-British Ship |

| III. | Human Snowballs |

| IV. | Training-Camp Life |

| V. | Concentrated for Embarkation |

| VI. | Many Weeks at Sea |

| VII. | The Land of Sand and Sweat |

| VIII. | Heliopolis |

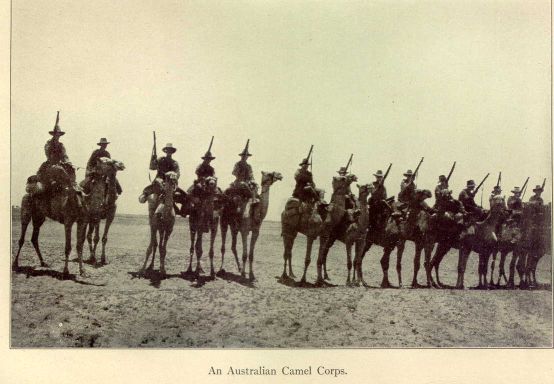

| IX. | The Desert |

| X. | Picketing in Cairo |

| XI. | "Nipper" |

| XII. | The Adventure of Youth |

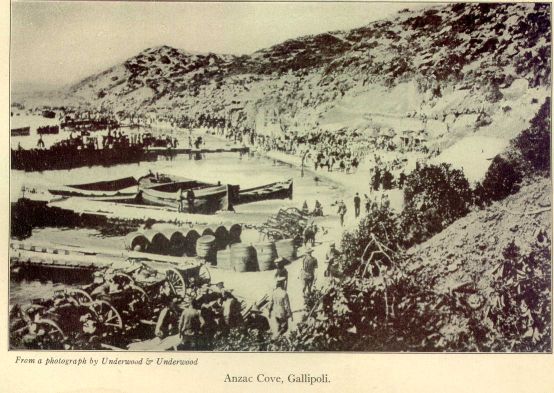

| XIII. | The Landing That Could Not Succeed—But Did |

| XIV. | Holding On and Nibbling |

| XV. | The Evacuation |

| XVI. | "Ships That Pass…" |

| XVII. | Ferry Post and the Suez Canal Defenses |

| XVIII. | First Days in France |

| XIX. | The Battle of Fleurbaix |

| XX. | Days and Nights of Strafe |

| XXI. | The Village of Sleep |

| XXII. | The Somme |

| XXIII. | The Army's Pair of Eyes |

| XXIV. | Nights in No Man's Land |

| XXV. | Spy-Hunting |

| XXVI. | Bapaume and "a Blighty" |

| XXVII. | In France |

| XXVIII. | In London |

| XXIX. | The Hospital-Ship |

| XXX. | In Australia |

| XXXI. | Using an Irishman's Nerve |

I am a scout; nature, inclination, and fate put me into that branch of army service. In trying to tell Australia's story I have of necessity enlarged on the work of the scouts, not because theirs is more important than other branches of the service, nor they braver than their comrades of other units. Nor do I want it to be thought that we undergo greater danger than machine-gunners, grenadiers, light trench-mortar men, or other specialists. But, frankly, I don't know much about any other man's job but my own, and less than I ought to about that. To introduce you to the spirit, action, and ideals of the Australian army I have to intrude my own personality, and if in the following pages "what I did" comes out rather strongly, please remember I am but "one of the boys," and have done not nearly as good work as ten thousand more.

I rejoice though that I was a scout, and would not exchange my experiences with any, not even with an adventurer from the pages of B. O. P. [1] Romance bathes the very name, the finger-tips tingle as they write it, and there was not infrequently enough interesting work to make one even forget to be afraid. Very happy were those days when I lived just across the road from Fritz, for we held dominion over No Man's Land, and I was given complete freedom in planning and executing my tiny stunts. The general said: "It is not much use training specialists if you interfere with them," so as long as we did our job we were given a free hand.

The deepest lines are graven on my memory from those days, not by the thrilling experiences—"th' hairbreadth 'scapes"—but by the fellowship of the men I knew. An American general said to me recently that scouts were born, not made. It may be so, but it is surprising what opposite types of men became our best scouts. There were two without equal: one, city-bred, a college graduate; the other a "bushie," writing his name with difficulty.

Ray Wilson was a nervous, highly strung sort of fellow, almost a girl in his sensitiveness. In fact, at the first there were several who called him Rachel, but they soon dropped it, for he was a lovable chap, and disarmed his enemies with his good nature. He had taken his arts course, but was studying music when he enlisted, and he must have been the true artist, for though the boys were prejudiced against the mandolin as being a sissy instrument, when he played they would sit around in silence for hours. What makes real friendship between men? You may know and like and respect a fellow for years, and that is as far as it goes, when, suddenly, one day something happens—a curtain is pulled aside and you go "ben" [2] with him for a second—afterward you are "friends," before you were merely friendly acquaintances.

Ray and I became friends in this wise. We were out together scouting preparatory to a raid, and were seeking a supposed new "listening post" of the enemy. There had been a very heavy bombardment of the German trenches all day, and it was only held up for three-quarters of an hour to let us do our job. The new-stale earth turned up by the shells extended fifty yards in No Man's Land. (Only earth that has been blown on by the wind is fresh "over there." Don't, if you have a weak stomach, ever turn up any earth; though there may not be rotting flesh, other gases are imprisoned in the soil.) This night the wind was strong, and the smell of warm blood mingled with the phosphorous odor of high explosive, and there was that other sweet-sticky-sickly smell that is the strongest scent of a recent battle-field. It was a vile, unwholesome job, and we were glad that our time was limited to three-quarters of an hour, when our artillery would re-open fire. I got a fearful start on looking at my companion's face in the light of a white star-shell; it might have belonged to one of the corpses lying near, with the lips drawn back, the eyes fixed, and the complexion ghastly. He replied to my signal that he was all right, but a nasty suspicion crept into my mind—his teeth had chattered so much as to make him unable to answer a question of mine just before we left the trench, but one took no notice of a thing like that, for stage fright was common enough to all of us before a job actually started. But "could he be depended on?" was the fear that was now haunting me.

Presently some Germans came out of their trench. We counted eight of them as they crawled down inside their broken wire. We cautiously followed them, expecting that they were going out to the suspected "listening post," but they went about fifty yards, and then lay down just in front of their own parapet. After about twenty minutes they returned the way they came, and I have no doubt reported that they had been over to our wire and there were no Australian patrols out.

This had taken up most of our time, and I showed Wilson that we had only ten minutes left, and that we had better get back so as not to cut it too fine. I was rather surprised when he objected, spelling out Morse on my hand that we had come out to find the "listening post," and we had not searched up to the right. The Germans were evidently getting suspicious of the silence, and to our consternation suddenly put down a heavy barrage in No Man's Land, not more than thirty yards behind us. There was no getting through it, and we grabbed each other's hand, and only the pressure was needed to signal the one word "trapped." When the shelling commenced we had instinctively made for a drain about four feet deep that ran across No Man's Land, and "sat up" in about six inches of water. Had we remained on top the light from the shells would have revealed us only too plainly, being behind us. I was afraid to look at my wristwatch, and when I did pluck up sufficient courage to do so, I might have saved myself the trouble, as the opening shell from our batteries at the same moment proclaimed that the time was up. As we huddled down, sitting in the icy water, we realized that the objective of our own guns was less than ten yards from us, and we could only hope and pray that no more wire-cutting was going to be done that night. Once, when we were covered with the returning debris, we instinctively threw our arms round each other. When we shook ourselves free, what was my amazement to find my companion shaking with—laughter. There was now no need for silence, a shout could hardly be heard a few yards away. He called to me: "Did you ever do the Blondin act before, because we are walking a razor-edge right now. We're between the devil and the 'deep sea,' anyway, and I think myself the 'deep sea' will get us." As I looked at him something happened, and I felt light-hearted as though miles from danger—all fear of death was taken away. What did it matter if we were killed?—it was a strange sense of security in a rather tight place.

After a short while our bombardment ceased. We learned afterward that word was sent back to the artillery that we were still out. As the boche fire also stopped soon afterward, we were able to scurry back and surprise our friends with our safe appearance.

After this experience Ray Wilson and I were closer than brothers—than twin brothers. It was only a common danger shared, such an ordinary thing in trench life, but there was something that was not on the surface, and though I was his officer, our friendship knew no barrier. I went mad for a while when his body was found—mutilated—after he had been missing three days. Don't talk of "not hating" to a man whose friend has been foully murdered! What if he had been yours?

A very different man was Dan Macarthy, a typical outbacker. All the schooling he ever got was from an itinerant teacher who would stay for a week at the house, correct and set tasks, returning three months later for another week. This system was adopted by the government for the sparsely settled districts not able to support a teacher, as a means of assisting the parents in teaching their children themselves. But Dan's parents could neither read nor write, and what healthy youngster, with "all out-of-doors" around him, would study by himself. Dan read with difficulty and wrote with greater, but I have met few better-educated men. His eyesight was marvellous, and I don't think that he ever forgot an incident, however slight. After a route march our scouts have to write down everything they saw, not omitting the very smallest detail. For example, if we pass through a village they have to give an estimate by examining the stores, how many troops it could support, and so on. No other list was ever as large as Dan's. He saw and remembered everything. He had received his training as a child looking for horses in a paddock so large that if you did not know where to look you might search for a week. Out there in the country of the black-tracker powers of observation are abnormally developed—lives depend on it, as when in a drought the watercourses dry up, and only the signs written on the ground indicate to him who can read them where the life-saving fluid may be found. Dan was a wonderful scout, a true and loyal friend, but he had absolutely no "sense of ownership." He thought that whatever another man possessed he had a right to; but, on the other hand, any one else had an equal right to appropriate anything of his (Dan's). He never put forward any theory about it, but would just help himself to anything he wanted, not troubling to hide it, and he never made any fuss if some one picked up something of his that was not in use. I never saw such a practical example of communism. At first, there were a number of rows about it, but after a while if any of the boys missed anything they would go and hunt through Dan's kit for it. The only time he made a fuss at losing anything was when one of his mates for a lark took his rosary. He soon discovered, by shrewd questioning, who it was, and there was a fight that landed them both in the guard-tent. The boys forbore to tease him about his inconsistency when he said: "It was mother's. She brought it from Ireland." Dan was still scouting when I was sent out well-punctured, and I doubt if there are any who have accounted for more of the Potsdam swine single-handed. His score was known to be over a hundred when I left. If I can get back again, may I have Dan in my squad! These two are but types of the boys I lived with so long, and got to love so well. Few of my early comrades are left on the earth; but we are not separated even from those who have "gone west," and the war has given to me, in time and eternity, many real friends.

The following pages are not a history of the Australians. I have no means of collecting and checking data, but they are an attempt to show the true nature of the Australian soldier, and sent out with the hope that they will remind some, in this great American democracy, of the contribution made by the freemen who live across the ocean of peace from you to "make the world safe for democracy."

I also have the hope that the stories of personal experience will make real to you some of the men whose bodies have been for three years part of that human rampart that has kept your homes from desolation, and your daughters from violation, and that you will speed in sending them succor as though the barrier had broken and the bestial Hun were even now, with lust dominant, smashing at your own door.

[1] Boys Own Paper.

[2] "Ben" was the living-room of a Scotch cottage where only intimate friends were admitted. Ian Maclaren says of a very good man: "He was far ben wi God."

Just where the white man's continent pushes the tip of its horn among the eastern lands there is a black man's land half as large as Mexico that is administered by the government of Australia. New Guinea has all the romance and lure of unexplored regions. It is a country of nature's wonders, a treasure-chest with the lid yet to be raised by some intrepid discoverer. There are tree-climbing fish, and pygmy men, mountains higher and rivers greater than any yet discovered. To the north of Australia's slice of this wonderland the Kaiser was squeezing a hunk of the same island in his mailed fist.

The contrast between the administration of these two portions of the same land forms the best answer to the question: "What shall be done with Germany's colonies?"

In German New Guinea there have always been more soldiers than civilians, cannibalism is rife, and life and property are insecure outside the immediate limits of the barracks. In British New Guinea or Papua there has never been a single soldier and cannibalism is abolished. A white woman, Beatrice Grimshaw, travelled through the greater part of it unprotected and unmolested.

The following story told of Sir William Macgregor, the first administrator, shows the way of Britishers in governing native races. He one day marched into a village where five hundred warriors were assembled for a head-hunting expedition. Sir William, then Doctor Macgregor, had with him two white men and twelve native police. He strode into the centre of these blood-thirsting savages, grasped the chief by the scruff of the neck, kicked him around the circle of his warriors, demanded an immediate apology and the payment of a fine for the transgression of the Great White Mother's orders for peace—the bluff worked, as it always does.

Australia has now added the late German colony Hermanlohe, or German New Guinea, to the southern portion, making an Australian crown colony of about two hundred and fifty thousand square miles. This was taken by a force of Australian troops conveyed in Australian ships. I was not fortunate enough to be a member of the expedition, but the ultimatum issued to the German commandant resulted in the Australian flag flying over the governor's residence at Rabaul within a few hours of the appearance of the Australian ships.

It was soon evident to the Australians that this was intended to be a German naval station and military post of great importance. Enough munition, and accommodation for troops were there to show that it was to be the jumping-off place for an attack on Australia. Such armament could never have been meant merely to impel Kultur on the poor, harmless blacks with their blowpipes and bows and arrows.

Every Australian is determined that these of nature's children shall not come again within reach of German brutality, but that they shall know fair play and good government such as the British race everywhere gives to the "nigger," having a sense of responsibility toward him that the men of this breed cannot escape. It would almost seem that the Almighty has laid the black man's burden on the shoulders of the Briton, as he was the first to abolish slavery, and no other people govern colored peoples for the sole benefit of the governed.

In every British colony other nations can trade on equal terms, and millions of pounds sterling are squeezed from the British public every year to provide for the well-being of native peoples, worshipping strange deities and jabbering a gibberish that would sound to an American like a gramophone-shop gone crazy! While other nations make their colonies pay for the protection they give them, the British people pay very heavily for the privilege (?) of sheltering and civilizing these far-flung, strange peoples. No true friend of the black man can consider the possibility of handing him back to the cruelty of Teutonic "forced Kultur."

The most heartless of Japanese gardeners could never twist and torture a plant into freak beauty more surely than the German system of government would compress the governed into a sham civilization. Australia would fight again sooner than that a German establishment should offend our sense of justice and menace our peace near our northern shores.

The western half of New Guinea (and the least known) belongs to Holland, and it was in the waters of this coast that the Australians whose story I am telling were living and working when the tocsin of war sounded. These sons of empire were registered under a Dutch name with their charter to work there from the Dutch Government, yet when they heard that men were needed for the Australian army, they dropped everything and hastened south to enlist. The long-obeyed calls of large profits and novel experiences, the lure of an adventurous life, were drowned by the bugle notes of the Australian "call to arms."

These were young men who had left the shores of their native country, venturing farther out a-sea, ever seeking pearls of great price. They had once been engaged in pearl-fishing from the northernmost point of Australia—Thursday Island—that eastern and cosmopolitan village squatting on the soil of a continent sacred to the white races.

When the handful of white people holding this newest continent first flaunted their banner of "No Trespassers" in the face of the multicolored millions of Asia, they declared their willingness to sweat and toil even under tropic skies, and develop their country without the aid of the cheap labor of the rice-eating, mat-sleeping, fast-breeding spawn of the man-burdened East. But this policy came well-nigh to being the death-blow to one little industry of the north, so far from the ken of the legislators in Sydney and Melbourne as to have almost escaped their recognizance.

The largest pearling-ground in the world is just to the north of this lovely Southland. It would seem as though the aesthetic oyster that lines its home with the tinting of heaven and has caught the "tears of angels," petrifying them as permanent souvenirs, loves to make its home as near to this earthly paradise as the ocean will permit.

When the law decreed that only white labor must be employed on the fleets a number of the pearlers went north and became Dutch citizens, for from ports in the Dutch Indies they could work Australian waters up to the three-mile limit. But as soon as it was known that Australia needed men, that we were at war, then politics and profits could go hang: at heart they were all Australians and would not be behind any in offering their lives. It took but a few days to pay off the crews, send the Jap divers where they belonged, beach the schooners, and take the fastest steamer back HOME—then enlist, and away, with front seats for the biggest show on earth.

We flew the Dutch flag, we were registered in a Dutch port, but every timber in that British-built ship creaked out a protest, and there paced the quarter-deck five registered Dutchmen who could not croak "Gott-verdammter!" if their lives depended on it, and who guzzled "rice taffle" in a very un-Dutch manner. Generally they forgot that they had sold their birthright. Ever their eyes turned southward, which was homeward, and only the mention of the Labor party brought to their minds the reason for leaving their native land. Each visit to port rubbed in the fact that they were now Dutchmen, as there were always blue papers to be signed and fresh taxes to be paid.

There was George Hym, who was a member of every learned society in England. The only letter of the alphabet he did not have after his name was "I," and that was because he did not happen to have been born in Indiana. Had that accident happened to him, even the Indiana Society would have given him a place at the speaker's table. He was the skipper of our fleet, had an extra master's certificate entitling him to command even the Mauretania. Many yarns were invented to explain his being with us. It was as if "John D." should be found peddling hair-oil.

Some said he had murdered his grandmother-in-law and dare not pass the time of day with Mr. Murphy in blue. Others claimed that the crime was far greater—the murder of a stately ship—and that the marine underwriters would have paid handsomely for the knowledge of his whereabouts. At any rate, he never left the ship while in port, and he seemed to have no relatives.

There were times when the black cloud was upon him and our voices were hushed to whispers lest the vibration should cause it to break in fury on our own heads—then he would flog the crew with a wire hawser, and his language would cause the paint to blister on the deck. At other times the memory of his "mother" would steal over his spirit and in a sweet tenor he would croon the old-time hymns and the old ship would creak its loving accompaniment, and the unopened shell-fish would waft the incense heavenward.

We believed most of his ill temper was due to the foreign flag hanging at our stern that the Sydney-built ship was ever trying to hide beneath a wave. He had sailed every sea, with no other flag above him than the Union Jack, and felt maybe that even his misdeeds deserved not the covering of less bright colors. It was like a ringmaster fallen on hard times having to act the part of "clown." But needs must where necessity drives, and as his own country would have none of him, he was tolerant of the flag that hid him from the "sleuths" of British law.

BUT WAR CAME, and the chance to redeem himself. What washes so clean as blood—and many a stained escutcheon has in these times been cleansed and renewed—bathed in the hot blood poured out freely by the "sons of the line." Whether the fleet was laid up or not, George was going! He might be over age, but no one could say what age he really was, and he was tougher than most men half his age. He left Queensland for Egypt with the Remount Unit in 1915, and is to-day in Jerusalem, with the British forces. Maybe he is treading the Via Dolorosa gazing at a place called Calvary, hoping that One will remember that he, too, had offered his life a ransom for past sins, which were many.

"For ours shall be Jerusalem, the golden city blest,

The happy home of which we've sung, in every land

and every tongue,

When there the pure white cross is hung,

Great spirits shall have rest." [1]

Prince Dressup was the dandy of the ship, a "swell guy" even at sea. His singlets were open-work, his moleskins were tailor-made, and his toe-nails were pedicured. The others wore only singlets and "pants," but had the regulation costume been as in the Garden of Eden, his fig-leaf would have been the greenest and freshest there!

At one time he had been the best-dressed man in Sydney, giving the glad and glassy optic to every flapper whose clocked silk stockings caught his fancy. Some girl must have jilted him, and this was his revenge on the fluffy things, the choice of a life where none of them could feast their eyes on his immaculate masculine eligibility. Or, maybe, he was really in love, and some true woman had told him only to return to her when he had proved himself a man. If so, he had chosen the best forcing-school for real manhood that existed prior to the war. And there was real stuff in Prince Dressup; for, although there was distinction and style even in the way he opened shell-fish, he took his share of the dirty work, and when the time came he would not let another man take his place in the ranks of the fighters for Australia's freedom. He said, when we knew of the war, "that it would be rather good fun," and when he died on Gallipoli, the bullet that passed through his lungs had first of all come through the body of a comrade on his back.

Chum Shrimp's size was the joke of the ship—he must have weighed three hundred pounds. He could only pass through a door sideways, and the "Binghis" (natives of New Guinea), when they saw him, blamed him for a recent tidal wave, saying that he had fallen overboard. He was the most active man I have ever known, and on rough days would board the schooner by catching the dinghee boom with one hand as it dipped toward the launch, and swing himself hand over hand inboard. I never expected the schooner to complete the opposite roll until Chum was "playing plum" in the centre.

Chum's parentage was romantic—his father a government official and his mother an island princess—he himself being one of the whitest men I have ever been privileged to call friend. We never thought he would get into the army, for though he was as strong as any two of us, he would require the cloth of three men's suits for his uniform, and he would always have to be the blank file in a column of fours, as four of his size would spread across the street, and to "cover off" the four behind them would just march in the rear of their spinal columns, having a driveway between each of them.

He was determined to enlist, and a wise government solved the problem by making him quartermaster, thus insuring in the only way possible that Chum would have a sufficient supply of "grub." This job was also right in his hands, because he possessed considerable business instinct; and you remember Lord Kitchener said of the quartermaster that he was the only man in the army whose salary he did not know!

The fifth Britisher of our crew will growl himself into your favor, being a well-bred British bulldog, looking down with pity on the tykes of mixed blood. Even before the war he showed his anti-German feelings by his treatment of a pet pig that we had on the schooner.

As I look back on it, our evening sport was a prophecy of what is to-day happening on the western front. "Torres" would stand growling and snapping at the porker, which would squeal and try to get away, but his hoofs could not grip the slippery deck, and though his feet were going so fast as to be blurred he would not be making an inch of progress. The Germans have been squealing and wanting to get away from the British bulldog but they do not know how to retire without collapse.

This pig had a habit of curling up among the anchor chains, and while we only used one anchor he escaped injury, but one rough day when both anchors were dropped simultaneously, piggy shot into the air with a broken back. The Germans have withstood the Allies so far, but now that America is with us, the back of the German resistance will soon be broken.

Of course Torres enlisted! In the beginning he was with Chum, and there was danger of his growing fat of body and soft of soul in the quartermaster's store, but he was rescued in time, and after months of exciting researches into canine history among the bones of the tombs of Egypt he earned renown at Armentières, as his body was found in No Man's Land with his head in the cold hand of a comrade to whom he had attached himself, and I believe his spirit has joined the deathless army of the unburied dead that watch over our patrols and inspire our sentries with the realization that on an Australian front No Man's Land has shrunk and our possession reaches right up to the enemy barbed wire.

[1] Mrs. A. H. Spicer, Chicago.

'Way out back in the Never Never Land of Australia there lives a patriotic breed of humans who know little of the comforts of civilized life, whose homes are bare, where coin is rarely seen, but who have as red blood and as clean minds as any race on earth.

The little town of Muttaburra, for instance, has a population of two hundred, one-half of whom are eligible for military service.

They live in galvanized-iron humpies with dirt floors, newspaper-covered walls, sacking stretched across poles for beds, kerosene-boxes for chairs, and a table made from saplings. The water for household uses is delivered to the door by modern Dianas driving a team of goats at twenty-five cents per kerosene-tin, which is not so dear when you know that it has to be brought from a "billabong" [1] ten miles away.

Most of the men in such towns work as "rouseabouts" (handy men) on the surrounding sheep and cattle stations. At shearing-time the "gaffers" (grandfathers) and young boys get employment as "pickers-up" and "rollers." Every shearer keeps three men at high speed attending to him. One picks up the fleece in such a manner as to spread it out on the table in one throw; another one pulls off the ends and rolls it so that the wool-classer can see at a glance the length of the wool and weight of the fleece; another, called the "sweeper," gathers into a basket the trimmings and odd pieces. These casual laborers and rouseabouts are paid ten dollars a week, while the shearer works on piece work, receiving six dollars for each hundred sheep shorn, and it is a slow man who does not average one hundred and fifty per day. All the shearing is done by machine, and in Western Queensland good shearers are in constant employment for ten months of the year. The shearers have a separate union from the rouseabouts, and there is a good deal of ill feeling between the two classes. When the shearers want a spell I have known them declare by a majority vote that the sheep were "wet," though there had not been any rain for months! There is a law that says that shearers must not be asked to shear "wet" sheep, as it is supposed to give them a peculiar disease. The rouseabouts do not mind these "slow-down" strikes, as they get paid anyway, but the shearers are very bitter when these have a dispute with the boss and strike, for it cuts down their earnings, probably just when they wanted to finish the shed so as to get a "stand" at the commencement of shearing near by.

When the war broke out the problem of the government was how to collect the volunteers from these outback towns for active service. It would cost from fifty to one hundred dollars per head in railway fare to bring them into camp.

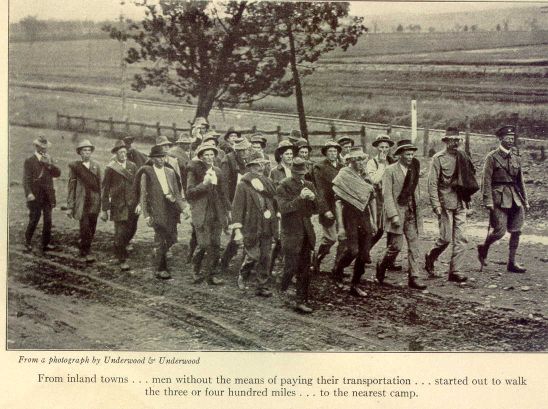

The outbacker, however, solved the problem without waiting for the government to make up its mind. They just made up their swags and "humped the bluey" [2] for the coast. That is how the remarkable phenomenon of the human snowball marches commenced.

Simultaneously from inland towns in different parts of Australia men without the means of paying their transportation to Sydney or Melbourne simply started out to walk the three or four hundred miles from their homes to the nearest camp. In the beginning there would just be half a dozen or so, but as they reached the next township they would tell where they were bound, and more would join. Passing by boundary riders' and prospectors' huts, they would pick up here and there another red-blood who could not resist the chance of being in a real ding-dong fight. Many were grizzled and gray, but as hard as nails, and no one could prove that they were over the age for enlistment, for they themselves did not know how old they were!

"Said the squatter, 'Mike, you're crazy, they have

soldier-men a-plenty!

You're as grizzled as a badger, and you're sixty year or so!'

'But I haven't missed a scrap,' says I, 'since I was

one-and-twenty,

And shall I miss the biggest? You can bet your

whiskers—No!!'" [3]

Presently the telegraph-wires got busy, and the defense department in Melbourne rubbed its eyes and sat up. As usual, the country was bigger than its rulers, and more men were coming in than could be coped with. The whole country was a catchment of patriotism—a huge river-basin—and these marching bands from the far-out country were the tributaries which fed the huge river of men which flowed from the State capitals to the concentration camps in Sydney and Melbourne. The leading newspapers soon were full of the story of these men from the bush who could not wait for the government to gather them in, and none should deny them the right to fight for their liberties.

Strange men these, as they tramped into a bush township, feet tied up in sacking, old felt hats on their heads, moleskins and shirt, "bluey," or blue blanket, and "billy," or quart canister, for boiling tea slung over their backs, all white from the dust of the road.

Old Tom Coghlan was there. He had lived in a boundary hut for twenty years, only seeing another human being once a month, when his rations were brought from the head station. His conversation for days, now that he was with companions, would be limited to two distinctive grunts, one meaning "yes," the other "no." But on the station he had been known to harangue for hours a jam-tin on a post, declaiming on the iniquities of a capitalist government. Those who heard him as they hid behind a gum-tree declared his language then was that of a college man. Probably he was the scion of some noble house—there are many of them out there in the land where no one cares about your past.

Here, too, was young Bill Squires, who had reached the age of twenty-one without having seen a parson, and asked a bush missionary who inquired if he knew Jesus Christ: "What kind of horse does he ride?"

Not much of an army, this band. They would not have impressed a drill-sergeant. To many even in those towns they were just a number of sundowners. [4] They would act the part, arriving as the sun was setting and, throwing their swags on the veranda of the hotel, lining up to the bar, eyeing the loungers there to see who would stand treat. Only the eye of God Almighty could see that beneath the dust and rags there were hearts beating with love for country, and spirits exulting in the opportunity offering in the undertaking of a man-size job. Perhaps a Kitchener would have seen that the slouch was but habit and the nonchalance merely a cloak for enthusiasm, but even he would hardly have guessed that these were the men who would win on Gallipoli the praise of the greatest British generals, who called them "the greatest fighters in the world." Soon the news of these bands "on the wallaby" [4] at the call of country caught the imagination of the whole nation. Outback was terra incognita to the city-bred Australian, but that these men who were coming to offer their lives should walk into the city barefoot could not be thought of. The government was soon convinced that the weeks, and, in some cases, months that would be occupied in this long tramp need not be wasted. Military training could be given on the way, and they might arrive in camp finished soldiers.

So the snowball marches were at last recognized and controlled by the government. Whenever as many as fifty had been gathered together, instructors, boots, and uniforms were sent along, and the march partook of a military character. No longer were they sundowners; they marched into town at the end of the day, four abreast, in proper column of route, with a sergeant swinging his cane at the head, sometimes keeping step to the tune of mouth-organs. The uniforms were merely of blue dungaree with white calico hats, but they were serviceable, and all being dressed alike made them look somewhat soldierly. The sergeants always had an eye open for more recruits, and every town and station they passed through became a rallying-point for aspirants to the army.

Their coming was now heralded—local shire councillors gathered to greet them, streets were beflagged, dinners were given—always, at every opportunity, appeals were made for more recruits. Sometimes, to the embarrassment of many a bushman whose meetings with women had been few and far between, there were many girls who in their enthusiasm farewelled them with kisses, though one can hardly imagine even a shy bushman failing to appreciate these unaccustomed sweets!

The snowballs grew rapidly. Farmers let down their fences, and they marched triumphantly through growing crops, each farmer vying with another to do honor to these men coming from the ends of the earth to deliver democracy.

"They're fools, you say? Maybe you're right.

They'll have no peace unless they fight.

They've ceased to think; they only know

They've got to go—yes, got to go!" [6]

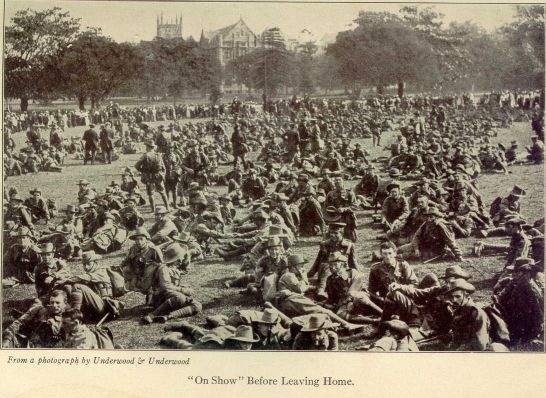

By the time they reached the camp many of these groups had grown to regiments, and under names such as "Coo-ees," "Kangaroos," "Wallaroos," they marched through the streets of Sydney between cheering throngs to the tune of brass bands. Such was the intention, at any rate, but before they reached the railway station their military formation was broken up, and in their enthusiasm the people of the capital practically mobbed these "outbackers," loading them, not merely with cigarettes and candy, but before night came there was many a bushman who had never seen a city before who carried a load of liquor that made even his well-seasoned head spin. The "chain lightning" of the bush was outclassed with the cinematograph whiskey of the city, that made its moving throngs and streets pass before his eyes like a kaleidoscope. A day or two in camp soon restored their balance. The training en route bore fruit; their commandant was so impressed that some of these regiments were equipped and officered, in a few weeks embarking for overseas.

Men from these regiments can be picked out to-day in London. If you see an Australian in a slouch-hat galloping his horse down Rotten Row, expecting "Algy" and "Gertrude" to give him a clear course, be sure it's a "Coo-ee!"

When some Australian sprawls in the Trocadero, inviting himself to table with the Earl of So-and-so, asking him to pass the butter, it's likely to be one of the "Kangaroos."

These Australians have had no master in their lives but the pitiless drought; they respect not Kings, but they love a real man who knows not fear and is kind to a horse. Masefield said of them in "Gallipoli": "They were in the pink of condition and gave a damn for no one!"

There is a certain hospital in London provided by a certain grand lady for convalescent Australians. She is very kind, but rather inclined to treat the patients as "exhibits" and show them off to her "tony" friends. The Australians bore this meekly for some time, but one day it was announced that some high personages would be visitors. On their arrival they found every bed was placarded, such as this: "No. 1 Bed—This is a Military Cross Hero. He bumped into a trench of Fritzes. If he hides his face under the bedclothes, it is because he is sensitive of his looks." "No. 2 Bed—Here lies a D.S.O. (Dirty Stop-Out)."

"'He stopped out of the trenches as long as he could.

And now the old blighter must stop out for good.'"

The bushman is a real man under all circumstances, having no awe of authority, no hesitation in speaking his mind, but a great reverence for women and a real respect for a religion that does not savor of cant.

[1] Billabong—a water-hole in a dry river-course.

[2] Humped the bluey—tramped across country with blue blanket (or swag).

[3] Robert W. Service.

[4] Sundowners—tramps who arrive at a ranch at sundown expecting to be put up for the night.

[5] On the wallaby—on the tramp.

[6] Robert W. Service.

The town of Bendigo received a great increase of liveliness by having to accommodate four or five thousand soldiers.

It had known some lively times in the old gold days, but when its "yellow love" became thin, thousands of people went to other fields and the former flourishing city became a husk and as dull as only a declining mining city can become; but, as usually happens in old mining districts, when the gold gives out, the solid wealth of the soil in crop-growing capacity is developed, and Bendigo is prospering again through the labors of the tillers of the soil, if not by the delvings of its miners. Still, farmers have not the same habit of "blowing in their earnings" and are, admittedly, a little dull. There was a story that when the town council put a notice at the busy centre—"Walk Round Corners"—many of the farmers made sure of keeping the law by getting out of their vehicles and leading their horses round! The old-time miner was rather in the habit of smashing the unoffending lamp-post that barred his straight progress to the "pub." where his favorite brand of fire-water was on tap.

The Bendigoans will never forgive me for having failed to appreciate the fact that their Golden City was far ahead even of Melbourne. They would never believe that any one could make the mistake in regard to their city that an American did about an Australian seaport when he marvelled at our frankness in putting notice at the entrance to the harbor "Dead Slow," and he never learned, after months of residence, that said notice was really a warning to shipping.

But at any rate the soldiers livened things up. They were gathered from many States—their day was just "one damn thing after another"—sometimes varied a bit with a right turn instead of left, and sometimes we would salute to the right instead of the left—but when night came, fun must be had somehow, and Bendigo had to supply it.

We all had some intelligence, so after spending a whole day in employment that forbade our using the smallest atom, we would seek during the night a "safety-valve."

The camp was in the show-ground, which naturally divided the young animals in training into different sorts—the élite had the grand stand, horse-boxes were grabbed by the N. C. O.'s, prize-cattle stalls were clean enough, but some line of mental association must have caused the powers that be to allot the "pig-and-dog" section to the military police and their prey.

It was fun on the arrival of a fresh contingent who were told "they could take what accommodation was left in the grand stand, the remainder having to bunk in the animal stalls," to see them rush the lower tiers, appropriating their six-foot length by dumping their "blueys" upon it, but that same night they would be convinced of their mistake as the old hands, living above them, exhibited their joy at having dodged the guard, returning in the small hours, by walking on every one possible on their way up top. Next morning there would be more applications for "horse-and-cattle" stalls, but the best ones would be gone, and they would have to be content to lie, six in a box, where a flooring-board was missing through which the rats would make their nightly explorations. But even this was better than the lower tiers of the grand stand, as the rats would not always wake you running across your face, but a husky in military boots stepping on it would rouse even the deadest in slumber. As he would step on about twenty others as well, the mutual recriminations would continue for hours, and as the real culprit would settle down in the dark into his own place without a word no one would know who it was. There would come from up above: "Shut up, there!" "What the h— are you makin' all that row about?" and the answer: "So would you make a row if a b— b— elephant stepped on your face!" "Go and bag your head! Anyway, there are two hundred men who didn't step on your face trying to go to sleep, and it will be reveille in an hour or so."

These grand-stand couches were bad places at the best of times. They may have been high and dry, but were open to every breeze that blew and were sheltered only on the side from which the rain never came. The Bendigo show committee must have faced them that way so that the sun and weather would be right in the eyes of the onlookers and prevent them seeing any "crook riding" or "running dead," etc.

The first item on the day's programme was the "gargling parade." Meningitis had broken out in the camp and every one had to gargle his throat first thing in the morning with salt water. We would be marched under our sergeant to each receive our half-pannikin of salt water at the A. M. C. tent. We would string out along the brick drain and then began the most horrible conglomeration of sounds that ever offended the ear. It was like the tuning up of some infernal orchestra. I don't know why it is, but it is surprising how few men can gargle "like a gentleman." For days I have not spoken to my best friend, who was most refined in other respects, but could not desist from spluttering and spraying the half dozen men nearest to him. We became friends again, but although we slept and messed together, I always took care never to be nearer than number ten from him at "gargling parade." I never heard any complaints from the people at Bendigo about this early-morning discord, but I learn that no frogs have been heard in the neighborhood since.

Our training at this camp was purely preliminary—we certainly formed fours seven billion times, and turned to the right fourteen billion, and saluted a post that represented an officer so often, that the rush of air caused by the quick movement of hands and heads had worn the edge off it.

We were so used to the sound of the sergeant-major's voice when he said, "The company will move to right in fours," that, when a grazing donkey happened to "hee-haw," the whole company formed fours. Even then only about half the company discovered the mistake—there was mighty little difference in the tones, anyway!

For a man that has never previously had military training, the first few weeks in camp is the most humiliating and trying experience that could be inflicted on him. I am quite sure that were it a prison and a treadmill he could not hate it the more.

Here was I, never been under orders since I was breeched, and even before then getting my own way, suddenly finding myself with every movement I was to make laid down in regulations, with about a score of men round me all day to see that I carried them out correctly.

How I used to hate that camp band, when it played at reveille, I cursed it in full BLAST because it would wake me suddenly when I seemed to have only just lain down, and reviled it when it played softly because I would not hear it and some of the other boys would wake me only when they were fully dressed; and the last to fall in at roll-call were picked for cook's fatigue—peeling spuds and cleaning dixies! How I loathed those dixies! The more grease you got on your hands and clothes the more appeared to be left in the dixie! The outside was sooty, the inside was greasy, and after I had done my best, the sergeant cook would make remarks about my ancestors which had nothing to do with the question, and I could not resent them lest I be detailed for a whole week of infernal dixie-cleaning. Anyway, all his ancestors had ever dared to do in the presence of mine was to touch their forelock.

In those first weeks I think I would gladly have murdered every sergeant. It was "Number 10, hold your head up!" "Put your heels together!" or a sarcastic remark as to whether I knew what a button was for, when I happened to miss doing one up in my flurry to dress in time, so that I would not be at the bottom of the line and picked for fatigue.

It is not often realized what a purgatory the educated, independent man who enlists as a private has to go through before his spirit is tamed sufficiently to stand bossing, without resentment, by men socially and educationally inferior. There was a young officer who called me over one day and told me to clean his boots. I answered, "Clean them yourself!" and got three days C. C. (confinement to camp). This same officer took advantage of his rank on several other occasions and sought to humiliate me. He was a poor sort of a sport, and many months later when I was his equal in rank in France I punched his head, telling him I had waited eighteen months to do it. So you see, everything comes to those who wait.

As a matter of fact, it was only three weeks before I was made an acting sergeant, but I have great sympathy with the soft-handed rookie, for in those three weeks it seemed to me that it was an easy thing to die for one's country, but to train to be a soldier was about the worst kind of penal servitude a man could undergo.

When acting as sergeant I was boss of five stables, each containing eight men, who could only squeeze in the floor space by sleeping head to feet. These stables were only completely closed in on three sides, the entrance side being boarded up three feet high, except for the space of the doorway. There was no attempt to close up this opening, except after afternoon parade, when visitors would have arrived before our changing into reception-clothes was completed, and we would partially block it with our waterproof sheeting.

I must mention that in the early days we had no real uniforms, but used to parade in blue dungarees and white cloth hats. They certainly made the men look "uniform," but "uniformly hideous," and none of us would be seen in them by a pretty girl, for a king's ransom. As soon as afternoon parade was dismissed, we would dive for our quarters, and re-don our "civvies" until next parade. The "cocky" would be resplendent again in his soft collar and red tie, and the city clerk in starched collar and cuffs.

Sometimes, however, there was a variation in time between the watches of the sergeant-major on the parade-ground and the guard at the gate. Visitors would be let in too soon, and innocently curious dames would wonder what these rows of stables were for, and wandering in that direction, would suddenly beat a blushing retreat at the revelation of hundreds of young men getting into respectable clothes who had no other place in which to change. Even if you did put a blanket or W. P. sheet over the entrance, there were no tacks, or nails, and it always fell down at the most awkward moments. However, the visitors soon got wise, and in about half an hour the boys who had callers would be proudly showing their friends, by the name above the feed-box, that the previous occupant of their quarters was the famous "Highflyer," winner of scores of cups, etc.

There were a good lot of us there from other states, and we had no special callers, but there were always girls who came out to see a Sergeant Martin or some such name not on the rolls. "Couldn't we find him for you?" If we did happen to find a sergeant of that name, he would not happen to be the one she wanted, then we would offer to do the honors of the camp, and as she would not like the hamper brought for her friend to be wasted, an acquaintance was soon struck up. Some boys were too shy, but nearly all of us had visitors after we had been in camp a week or two.

The town had appointed a soldiers' entertainment committee, and they gave us a concert every night in the Y. M. C. A. tent. These were high-class shows, but most of us preferred to go into the town though we only had leave till six o'clock.

Some of us used to stay in town till midnight, trusting to our ingenuity in bluffing the guard. Many were the dodges used to gain entrance to the camp. Some townsboys could get passes till midnight about once a week, and instead of handing these to the guard, as they hurried past, they would substitute a piece of blank paper. If they got past it was good for another occasion, as the date was easily altered. If they were pulled up they would apologize profusely and hand up the right pass. Sometimes we would wait until there were a score of us, and while the sentry was examining the first pass the others would rush the gate. Rarely could more than one or two be identified, and the odds were in our favor.

Soon the guard was doubled, and only a small wicket was opened, where but one man could pass through at a time. Then we scraped holes under the galvanized-iron fence that surrounded the show-ground, concealing them carefully with bushes and watching out for the pickets who patrolled the outside of the camp.

I think I got my best training in scouting dodging these pickets. I have climbed trees, crawled into hollow logs, and played 'possum in gullies to escape them. Being caught meant not only several days in the guard-tent, but the loss of the chance of "stripes."

There was really not much excitement in the town and many of us just stayed late for the excitement of breaking the law without being caught. It was the outbreak of our personality after being mere cogs in a drill-machine all day. I never was guilty of returning except after hours, and I never was caught, even when extraordinary precautions were taken to get the delinquents. Sometimes a check-roll would be called, at some uncertain hour, but it was always a point of honor for the boys in camp to answer "present" for any absent mates.

Evidently I was destined to be a scout. From this camp I was drafted into the intelligence section for specialized training. That has been my work all the time overseas, and I never had harder work dodging Fritz's sentries than those pickets round Bendigo show-ground.

One morning there was great excitement in the Bendigo camp. An announcement was made that members of rifle-clubs would be tried out on the range and all qualifying with ninety per cent of marks would be sent overseas in the earliest draft. All who had ever fired a gun, and some who hadn't, stepped forward for trial, but on the range the eligibles were found to be only fifty, of whom I was lucky enough to be one.

The next day we lined up for a final medical inspection. As we passed the doctor there were none to congratulate us, but we made allowances, knowing how sore the others were who had failed to qualify. We packed up our kits and marched to the train leaving a camp literally "green with envy." We shouted good-bye, amazed at the good fortune that had chosen us to escape many months of deadly grind in the training-camp, and it seemed as we passed in single file through the old showground turnstile as if already we had left Australia behind, and in imagination our feet felt the roll of the ship that in our fancy was even now carrying us out on the "Great Adventure"; and our thoughts wafted farewells to mother or wife, as we bade them never fear but that we would show that their men were not unworthy of their regard.

Our spirits had not been so elated had we known that more weeks of camp life in Australia yet awaited us. Had we not thought that we were destined for immediate embarkation we might have been better disposed to appreciate Broadmeadows, but as it was it seemed to us about the last place made—and not yet finished.

As the days passed, our detestation of the place grew, but we soon found that our impatience of delay in embarking was shared by several thousand others who had gathered there from many States and been weeks trampling out the grass and raising the dust in those accursed fields till it choked them, when they had long before expected to be inhaling the ozone from the deck of some good ship that with every knot bore them nearer to the strife for liberty and a man's chance.

This camp was always seething with discontent, for with the delay was in every man's heart the haunting fear that the war might be over ere he got there, and none could think without dread of the possibility that we might have to endure the lowest depths of humiliation in returning home without having struck a blow.

On one occasion the impatience that was like a festering sore among the men of this camp nearly resulted in a show of mutiny. Oil was added to the flame of our discontent by the tactlessness of the camp adjutant. He will always be known to the men of those days as the "Puppy." His father was a commanding officer, and though he was only nineteen years of age and his voice was just breaking, he rode the "high-horse of authority" over those men as though they were schoolchildren. When his lady friends came to visit him he would order a special parade so that they might see him in command of "his men, doncherknow!" But his "high horse" nearly threw him one day when he gave the order, "Move to the right and fours, form fours!" and not a man moved. Blushing like a schoolgirl, he called the officers out for consultation and sent for the commandant. When, however, real men took command there was no further trouble, though the boys openly voiced their complaints—"that their leave was restricted for no reason"—"that they were on parade after hours," and "Why don't they send us away to fight, anyway? That's what we enlisted for." The announcement that we would be sailing soon brought forth cheers and every one was in good humor again. Only let us be sure that we were off to war, and we could stand even the Puppy's yelping.

But all the same, there were a couple more weeks of the mud and dust to be endured. I have been in sand-storms in the interior of Australia when the sun was blotted out and in Egypt when the Kam-seen said to the mountain, "Be thou removed!" and it was removed in a single night some fifty miles away, but neither of these is worse than some of the dust-storms that blow over Melbourne, and at Broadmeadows we got their full force. We would march in from the parade-ground not being able to see the man in front of us, and in the light of the candles in our tents our very features were blotted out and nothing but eyes and teeth were visible, except that, perhaps, in some faces two small holes would suggest where the nose might be. It was only after a good deal of shaking that the place could be discerned where neck emerged from collar. There were some serious accidents in these dust-storms through men trying to bump buildings out of their way, and on one occasion two poor fellows were nearly killed in failing to give the "right-away" to a couple of sheets of galvanized iron. And when it rained, great snakes! Where was there ever mud like that! We certainly did a good deal in mixing the soil of those paddocks, for we would carry an acre of it from around the tents onto the drill-ground, where we would carefully scrape it off, and when we marched back we would bring another acre on our boots to form a hillock at our tent door. If there had been but an inch of rain we would lift up on the soles of our boots all the wet earth, uncovering a surface of dust to pepper our evening meal.

Large sums of money have been spent on this camp since those days and it is now a nursery for the recruits who have volunteered three years late and need the enticement of feather beds to induce them to leave mother. It has been thoroughly drained and terraced, and comfortable huts have been erected, but we simply rolled in blankets on bare Mother Earth and sheltered from sun and rain in tents that were supposed to be water-proof, and generally were unless you happened to touch them when wet. If you did accidentally happen to rub against the sides, there would be a stream of water pouring down on you all night. There was no escaping this, for there was not an inch of ground inside the tent that was not covered by man. In fact, with ten in a tent, one of us had to lie three-quarters outside, anyway, which was the chief reason why I was never last in. Dressing was a problem, for every one must needs dress at the same time, and from the outside the tent must have looked something like a camel whose hump was constantly slipping. Perhaps that is why every one used safety-razors after a while, for although our faces would frequently look as though they had been mixed up in barbed wire, there was really not much danger of cutting one's throat, for even though you received a forty-horse-power jolt at a critical moment, the razor-guard prevented your life being actually imperilled.

In this camp we received our uniforms and equipment, but it was only after a lot of exchanging had been done that our uniforms made us look soldierly. Oh, Lord! what caricatures many of us were after the first issue. There were practically no out-sizes in tunics, but plenty of the men were not merely out-size, but odd-sized. Some little fellows looked as if they were wearing father's coat, and there were others who looked as if they were wearing that of baby brother. Some had to turn back the cuffs two or three times, while others had at least a foot of wrist and forearm showing. But the breeches! Oh, my Aunt Sarah! Some were able to tuck the bottoms into their boots, while others had to wind puttees above their knees. There were men who couldn't bend comfortably, while others had room to carry a couch about with them. However, the orders were that we were to keep on exchanging until we got something like a fit, but as there were varieties in the quality of the cloth, there were those who preferred a misfit to poor material, so that there were always a number who looked like Charlie Chaplin.

New arrivals in camp were always called "Marmalades," because they were distinguished by their relish for marmalade jam. After they had consumed over a ton of it and forgotten the taste of any other kind of jam then they looked at a tin of it with loathing, when they would be considered to have passed the "recruit" stage and be on a fair way to becoming soldiers.

Long before we got our uniforms we were issued greatcoats, hats, and boots. At this time the only other clothes we had were the blue dungarees and white cloth hats called "fatigue dress." No self-respecting man would allow a lady friend to see him in this rig-out. Yet one must breathe the free air of liberty some time, and "confinement to camp" was a punishment for crime. So we compromised by strolling the city streets with our military hats and boots, with the army greatcoats seeking to hide the blue hideousness of our dungarees. Some of us sought to be unconscious of the foot or two of blue cloth showing beneath the greatcoat, and these were times when we envied the little chap enveloped in a greatcoat that hung down as low as his boots. We received at this time the nickname "Keystone soldiers," some genial ass conceiving that we looked as funny as the Keystone police. These greatcoats were a bit out of place on a day that was over a hundred in the shade, and they did not look exactly the thing at a dainty tea-table in a swell cafe, but we clung to those greatcoats as our only salvation, for they did hide the blue horror beneath. I should have explained that our civilian clothes had been taken from us, and we were forbidden, under severe penalty, to wear any but regulation dress. Nevertheless, the lucky dogs who had relatives near by would take the risk and borrow a cousin's rig-out, but we hated them as mean dogs, feeling they were taking an unfair advantage; and, if we got a chance, we would, by innuendo, hint to the lady in the case that these fellows did so much dixie-cleaning that their dungarees were too stiff to wear!

Nearing the close of a long, sunny Australian day—the air soft, warm, and sweet, and the sky suffused with a lovely pink. It was visiting-day—Friday. In the camp, rows of figures in blue dungarees and white hats were marching round and round the drill-ground, turning from left to right, forming fours, then back to two deep, and, so on and so on. Out across the flat ground between the camp and the railway-station, coming steadily toward the camp, was a very straggly line of white figures. As they came closer, one saw they were women and girls, fresh and dainty in summer frocks and hats, all carrying big baskets, suitcases, and all manner of strange and weirdly shaped parcels. A few odd males among them, mostly nearing sixty, or under ten. Some were portly, puffing a little, some old, their heavy parcels making their lips quiver and their step slow—and girls, just multitudes of them, all sizes, ages, and shapes—blondes, brunettes, in-betweens, and from every rank in the social scale—mostly in groups of any number from two to twenty—some chaperoned, some not. Here and there one saw one alone carrying an extra heavy suitcase, which somehow you knew contained extra-specially good things to eat, and when you looked at her face under her big hat a certain something there told you that on the third finger of the left hand under her glove you would surely find a diamond half-loop, and even, perhaps, a very plain new gold band!

From the drill-ground the soldiers could see this crowd of womenfolk steadily coming toward them, and grew acutely aware of their shapeless, grubby dungarees, dusty boots, and perspiring faces under tired-looking white hats. Agonized glances were turned on the sergeant-major as, with his face utterly expressionless, ignoring the oncoming feminine figures, he still right-about-turned and quick-marched them. The fluttering white frocks came closer and closer, and as they began to get near the gate imploring glances were turned in the direction of the guard, praying they would not let any one in. Then suddenly, to their immense relief, they were dismissed; then it was just one mad rush for tents. Swearing breathlessly as they bumped into each other or tripped over tent-pegs and ropes, they ran, putting on an extra spurt every time they glanced over their shoulders and saw the women advancing upon them in mass formation. Changing was soon accomplished, not without a good deal of confusion, mixing up of garments, and splashing water around, but when they were finally all dressed and again in khaki uniforms smiles of satisfaction spread over clean and shiny faces as they glanced down at neat uniforms and well-polished boots—Smoke-o that day had seen much activity in the business of brushing and polishing.

Down at the gate the picket was having a busy time answering questions: "Could you tell me where I will find Private McIntosh?" "What tent is my brother in, d'you know?" But as many of the eager questioners were, well, very delightful, none of the boys on picket duty kicked at their job. Some of the boys who were quicker dressers than the others now began to come down to the gate, bustling into the crowd of womenfolk, looking eagerly for their own particular visitors, and, seeing them, dashing up, hugging mothers and sisters, shaking bashfully the hand of "sister's friend," gathering up all their parcels, and, with them all following close behind, leading the way to "a dandy spot" for supper. In course of time the sorting-out process was complete, and the camp was dotted with hundreds of groups, large and small, all laughing and talking, and busy unpacking those very weighty parcels. Boys who had changed into uniform with the others and gone down to the gate, though not really expecting any one as they were from out back and had no city friends, but still feeling lonesome, and, perhaps, having a forlorn hope that there might be some one, had helped rather bewildered girls, carrying their baskets and finding the man they wanted—these boys now looked longingly around at these groups, hoping some one would invite them to join in; and how their faces brightened when one of their tentmates, looking up from a hunk of frosted cake, would see them and shout, "Hey, Bill! Here!" and, after the agony of being presented to "My mater, my sister, and Miss Stephenson," things were just O. K.

Yet there were a good many lonely ones, boys who hadn't even bothered to change, still in their ill-shaped blue dungarees, dusty boots, and cloth hats, some of them walking round, their heads down, and kicking at every clump of grass or stone that came within reach of their boots—some of them, too lonely even to look at the fun, hanging over the fences, occasionally exchanging a few peevish words with each other, while others gathered round the old man who kept a stall just inside the gate and bought lemonade, ginger ale, and arrowroot biscuits, consuming them with much assumed gusto, while others still sat inside their tents or the Y. M. C. A. hut.

Looking at these boys gave one a deep heartache, but the sob in one's throat changed suddenly to a laugh as one looked at their hats. Americans in Australia have always held the prize for originality in headgear, but that same prize must now be handed over to our soldiers in camp. What they can do with one simple, unoffending, white-cloth cricket-hat passes all belief. Seldom, as is the case with their dungarees, did these boys have a hat that really fitted them, those with big heads had the smallest hats, and those with extra small heads got the largest size. They were all shades, from their original pure white down, or up, to an exact match with Mother Earth. And the shapes! Some wore them turned down all round, some turned up all round, some turned up in front and down at the back, some vice versa, some turned up on the left side and down at the right, and some down at the left and up at the right; some had tucked the front part in, leaving a large expanse of bare brow, while the back part, turned down, shaded the nape of their neck. Some applied this idea reversed, turning in the back; some turned the brim right in except for a small peak à la Jockey; some had a peak back and front, made by rolling in both sides, and some settled the question by turning the whole brim in, the resultant skull-cap effect being such as to bring tears to the eyes of all beholders.

These disconsolate, lonely faces, with, in the cases of the younger boys, tear-filled eyes, surmounted by these absurd, preposterous hats—it was truly a case of not knowing whether to laugh or to cry; so by laughing hard, the women who saw them hid their tears.

It soon began to get dark—in Australia our twilight is short—so suitcases and baskets were repacked, but only this time with plates, cups, spoons, etc.—and one by one the parties rose and went over to the Y. M. C. A. tent for the concert. In the tent tables had all been moved out and rows of chairs and forms filled it. In a short time they were all occupied, the officers sitting in front, some with visitors, others alone and casting very longing eyes at the lovely girls coming in with the men.

The concert was given, as they mostly were, by an amateur club, and had its ups and downs. But every one enjoyed it—the items that took the popular fancy were loudly applauded, and the others that weren't so good—well, no one minded, as every one was happy, and the lights were very dim!

By the end of the concert it was nine o'clock, the time for all visitors to be shooed off home. The bugles blew "The First Post," and every one, very unwilling, made their way slowly down to the gate. Here good-byes were said, meetings arranged for the boys' next leave, promises made to come out next week, with much chattering and laughing, though here and there, back in the shadows, would be couples, very quiet, maybe engaged, perhaps just married, hating to separate.

At last the remaining white frocks flutter through the big gate and join in the stream already straggling across country toward the railway-station, every one quiet and very tired.

In camp the boys stroll over to their tents, exchanging an occasional word with pals, but for the most part silent, and turn in, tired also, and a little thoughtful. In an hour all the stars shine brightly from the velvety, blue-black sky, the soft-scented air wafts in through open tent-flaps, lights are out, and all is quiet in the camp, except for the periodical changing of pickets and the occasional roar of a passing train in the distance.

A troop-ship has no longer a name, but although the ship we boarded at Port Melbourne docks was designated by the number A 14, it was not hard to discover that we were on a well-known ocean-liner, for on life-buoys and wheelhouse the paint was not so thick that inquisitiveness could not see the name that in pre-war days the Aberdeen line proudly advertised as one of their most comfortable passenger-carrying ships. That meant little to us, for her trimmings of comfort had been stripped off but for a few cabins left for the officers, and when we were mustered in our quarters, we wondered where we would sleep, for no bunks met our eye.

Embarkation is for every one concerned the most tedious, red-tapeyist incident in a soldier's career. For fear of spies the exact day had been kept secret, and although we had expected to leave weeks previously, and had, at least, twenty times said our tearful farewells, when the actual day arrived there was no expectation of it and no farewells. The night previously men had said to their wives, "See you to-morrow, dear!"—meetings were arranged with best girls, for the movies—in fact, not the faintest rumor had spread through the camp that there was any likelihood of our sailing for weeks, and here in the early dawn we were lined up on the wharf, being counted off like sheep, and allotted our quarter cubic foot of ship's space; preparing for our adventure overseas without the slightest chance of letting any one I know what had happened to us. We could sympathize with the feelings of our folks as they would journey out to camp with the usual good things to eat only to find we had gone. By this time we would be well out at sea, en route for the Great Adventure, but it was hard luck for mothers and wives suddenly to find us gone without warning, and having to wait many weeks for the first letter.

It was wet, it was cold, it was dark on that wharf. If we were counted once, we were counted fifty times, and for hours we stood in the rain because there were two men too many. No, not men, for they were found to be boys of fifteen who had stolen uniforms and had hidden near the wharf for days to get away with the troops, but they were discovered, as every man had his name called and was identified by his officer as he passed up the gangway. One of them was not to be kept off, however: he slipped round the stern and climbed up the mooring cables like a monkey, and as no one gave him away he was undiscovered until rations were issued, so, perforce, he was a member of the ship's company and went with us to Egypt.