Project Gutenberg's A Short History of Russia, by Mary Platt Parmele This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A Short History of Russia Author: Mary Platt Parmele Release Date: October 23, 2005 [EBook #16930] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SHORT HISTORY OF RUSSIA *** Produced by Al Haines

If this book seems to have departed from the proper ideal of historic narrative—if it is the history of a Power, and not of a People—it is because the Russian people have had no history yet. There has been no evolution of a Russian nation, but only of a vast governing system; and the words "Russian Empire" stand for a majestic world-power in which the mass of its people have no part. A splendidly embroidered robe of Europeanism is worn over a chaotic, undeveloped mass of semi-barbarism. The reasons for this incongruity—the natural obstacles with which Russia has had to contend; the strange ethnic problems with which it has had to deal; its triumphant entry into the family of great nations; and the circumstances leading to the disastrous conflict recently concluded, and the changed conditions resulting from it—such is the story this book has tried to tell.

M. P. P.

Natural Conditions

Greek Colonies on the Black Sea

The Scythians

Ancient Traces of Slavonic Race

Hunnish Invasion

Distribution of Races

Slavonic Religion

Primitive Political Conceptions

The Scandinavian in Russia

Rurik

Oleg

Igor

Olga's Vengeance

Olga a Christian

Sviatoslaf

Russia the Champion of the Greek Empire in Bulgaria

Norse Dominance in Heroic Period

System of Appanages

Vladimir the Sinner Becomes Vladimir the Saint

Russia Forcibly Christianized

Causes Underlying Antagonism Between Greek and Latin Church

Russia Joined to the Greek Currents and Separated from the Latin

Principalities

Headship of House of Rurik

Relation of Grand Prince to the Others

Civilizing Influences from Greek Sources

Cruelty not Indigenous with the Slavs

How and Whence it Came

Primitive Social Elements

The Drujina

End of Heroic Period

Andrew Bogoliubski

New Political Center at Suzdal

The Republic of Novgorod

Invasion of Baltic Provinces by Germans

Livonian and Teutonic Orders

Russian Territory Becomes Prussia

Mongol Invasion

Genghis Khan

Cause of Downfall

The Rule of the Khans

Humiliation of Princes

Novgorod the Last to Fall

Alexander Nevski

Russia Under the Yoke

Lithuania

Its Union with Poland

A Conquest of Russia Intended

Daniel First Prince of Moscow

Moscow Becomes the Ecclesiastical Center

Power Gravitates Toward that State

Centralization

Dmitri Donskoi

Golden Horde Crumbling

Origin of Ottoman Empire

Turks in Constantinople

Moscow the Spiritual Heir to Byzantium

Ivan Married to a Daughter of the Caesars

Civilizing Streams Flowing into Moscow

Work for Ivan III.

And How He Did it

Friendly Relations with the Khans

Reply to Demand for Tribute in 1478

The Yoke Broken

Vasili the Blind

Fall of Pskof

Splendor of Courts Ceremonial

Nature of Struggle which was Evolving

Ivan IV.

His Childhood

Coup d'État

Unmasking of Adashef and Silvester

A Gentle Youth Developing into a Monster

Solicitude for the Souls of his Victims

Destruction of Novgorod

England Enters Russia by a Side Door

Friendship with Elizabeth

Acquisition of Siberia

The Sobor or States-General Summoned

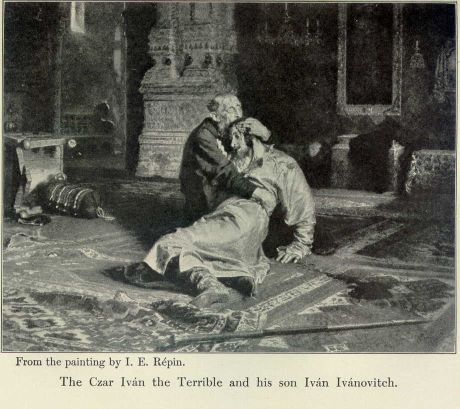

Ivan Slays his Son and Heir

His Death

Boris Godunof

The Way to Power

A Boyar Tsar of Russia

Serfdom Created

The False Dmitri

Mikhail the First Romanoff

Time of Preparation

The Cossacks

Attempt of Nikon

Death of Mikhail

Alexis

Sympathizes with Charles II.

Natalia

Death of Alexis

Feodor

Sophia Regent

Peter I.

Childhood

Visit to Archangel

Azof Captured

How a Navy was Built

Sentiment Concerning Reforms

A Conspiracy Nipped in the Bud

Peter Astonishes Western Europe

Charles XII.

Battle of Narva

St. Petersburg Founded

Mazeppa

Poltova

Peter's Marriage with Catherine

Campaign against Turks

Disaster Averted

Azof Relinquished

Treaty of Pruth

Reforms

The Raskolniks

Visit to France

His Son Alexis a Traitor

His Death

Catherine I.

Anna Ivanovna

Ivan VI.

Elizabeth Petrovna

French Influences Succeed the German

Peter III.

His Taking off

Catherine II.

Conditions in Poland

Victories in the Black Sea

Pugatchek the Pretender

Peasants' War

Reforms

Partition of Poland

Characteristics of Catherine and of her Reign

Her Death

Paul I.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Franco-Russian Understanding

Assassination of Paul

Alexander I.

Plans for a Liberal Reign

Austerlitz

Alexander I. an Ally of Napoleon

Rupture of Friendship

French Army in Moscow

Its Retreat and Extinction

The Tsar a Liberator in Europe

Failure of Reforms

Araktcheef's Severities

Conspiracy at Kief

Death of Alexander I.

Constantine's Renunciation

Revolt

Succession of Nicholas I.

Order Restored

Character of Nicholas

His Policy

Polish Insurrection

Reactionary Measures

Europe Excluded

Turco-Russian Understanding

Beginning of the Great Diplomatic Game

Nature of the Eastern Question

Intellectual Expansion in Russia

1848 in Europe

Nicholas Aids Francis Joseph

Hungary Subjugated

Nicholas claims to be Protector of Eastern Christendom

Attempt to Secure England's Co-operation

Russia's Grievance against Turkey

His Demands

France and England in Alliance for Defense of Sultan

Allied Armies in the Black Sea

The Crimean War

Odessa

Alma

Siege of Sevastopol

Death of Nicholas I.

Alexander II.

End of Crimean War

Reaction Toward Liberalism

Emancipation of Serfs

Means by which It was Effected

Patriarchalism Retained

Hopes Awakened in Poland

Rebellion

How it was Disposed of

Reaction toward Severity

Bulgaria and the Bashi-Bazuks

Russia the Champion of the Balkan States

Turco-Russian War

Treaty of San Stefano

Sentiment in Europe

Congress of Berlin

Diplomatic Defeat of Russia

Waning Popularity of Alexander II.

Emancipation a Disappointment

Social Discontent

Birth of Nihilism

Assassination of Alexander II.

The Peasants' Wreath

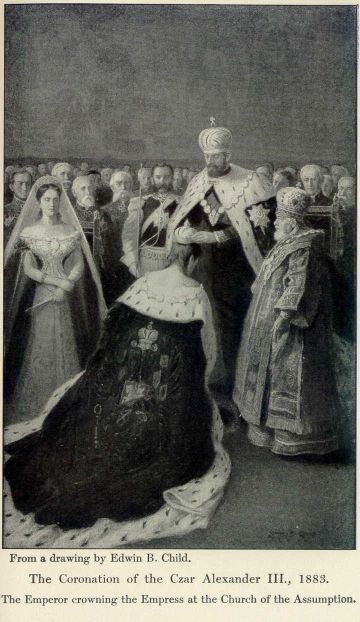

Alexander III.

A Joyless Reign

His Death

Nicholas II.

Russification of Finland

Invitation to Disarmament

Brief Review of Conditions

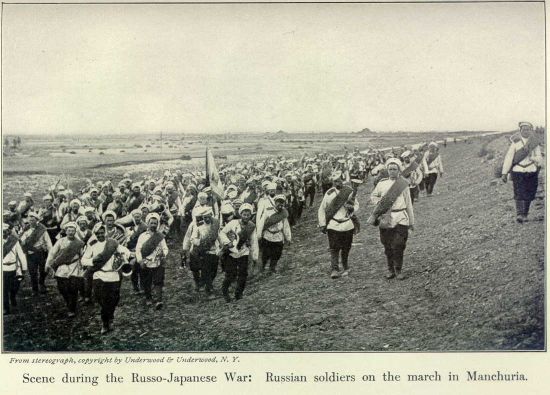

Conditions Preceding Russo-Japanese War

Nature of Dispute

Results of Conflict

Peace Conference at Portsmouth

Treaty Signed

A National Assembly

Dissolution of First Russian Parliament

Present Outlook

The topography of a country is to some extent a prophecy of its future. Had there been no Mississippi coursing for three thousand miles through the North American Continent, no Ohio and Missouri bisecting it from east to west, no great inland seas indenting and watering it, no fertile prairies stretching across its vast areas, how different would have been the history of our own land.

Russia is the strange product of strange physical conditions. Nature was not in impetuous mood when she created this greater half of Europe, nor was she generous, except in the matter of space. She was slow, sluggish, but inexorable. No volcanic energies threw up rocky ridges and ramparts in Titanic rage, and then repentantly clothed them with lovely verdure as in Spain, Italy, and elsewhere. No hungry sea rushed in and tore her coast into fragments. It would seem to have been just a cold-blooded experiment in subjecting a vast region to the most rigorous and least generous conditions possible, leaving it unshielded alike from Polar winds in winter or scorching heat in summer, divesting it of beauty and of charm, and then casting this arid, frigid, torpid land to a branch of the human family as unique as its own habitation; separating it by natural and almost impassable barriers from civilizing influences, and in strange isolation leaving it to work out its own problem of development.

We have only to look on the map at the ragged coast-lines of Greece, Italy, and the British Isles to realize how powerful a factor the sea has been in great civilizations. Russia, like a thirsty giant, has for centuries been struggling to get to the tides which so generously wash the rest of Europe. During the earlier periods of her history she had not a foot of seaboard; and even now she possesses only a meager portion of coast-line for such an extent of territory; one-half of this being, except for three months in the year, sealed up with ice.

But Russia is deficient in still another essential feature. Every other European country possesses a mountain system which gives form and solidity to its structure. She alone has no such system. No skeleton or backbone gives promise of stability to the dull expanse of plains through which flow her great lazy rivers, with scarce energy enough to carry their burdens to the sea. Mountains she has, but she shares them with her neighbors; and the Carpathians, Caucasus, and Ural are simply a continuous girdle for a vast inclosure of plateaus of varying altitudes,[1] and while elsewhere it is the office of great mountain ranges to nourish, to enrich, and to beautify, in this strange land they seem designed only to imprison.

It is obvious that in a country so destitute of seaboard, its rivers must assume an immense importance. The history, the very life of Russia clusters about its three great rivers. These have been the arteries which have nourished, and indeed created, this strange empire. The Volga, with its seventy-five mouths emptying into the Caspian Sea, like a lazy leviathan brought back currents from the Orient; then the Dnieper, flowing into the Black Sea, opened up that communication with Byzantium which more than anything else has influenced the character of Russian development; and finally, in comparatively recent times, the Neva has borne those long-sought civilizing streams from Western Europe which have made of it a modern state and joined it to the European family of nations.

It would seem that the great region we now call Russia was predestined to become one empire. No one part could exist without all the others. In the north is the zone of forests, extending from the region of Moscow and Novgorod to the Arctic Circle. At the extreme southeast, north of the Caspian Sea and at the gateway leading into Asia, are the Barren Steppes, unsuited to agriculture or to civilized living; fit only for the raising of cattle and the existence of Asiatic nomads, who to this day make it their home.

Between these two extremes lie two other zones of extraordinary character, the Black Lands and the Arable Steppes, or prairies. The former zone, which is of immense extent, is covered with a deep bed of black mold of inexhaustible fertility, which without manure produces the richest harvests, and has done so since the time of Herodotus, at which period it was the granary of Athens and of Eastern Europe.

The companion zone, running parallel with this, known as the Arable Steppes, which nearly resembles the American prairies, is almost as remarkable as the Black Lands. Its soil, although fertile, has to be renewed. But an amazing vegetation covers this great area in summer with an ocean of verdure six or eight feet high, in which men and cattle may hide as in a forest. It is these two zones in the heart of Russia that have fed millions of people for centuries, which make her now one of the greatest competitors in the markets of the world.

It is easy to see the interdependence created by this specialization in production, and the economic necessity it has imposed for an undivided empire. The forest zone could not exist without the corn of the Black Lands and the Prairies, nor without the cattle of the Steppes. Nor could those treeless regions exist without the wood of the forests. So it is obvious that when Nature girdled this eastern half of Europe, she marked it for one vast empire; and when she covered those monotonous plateaus with a black mantle of extraordinary fertility, she decreed that the Russians should be an agricultural people. And when she created natural conditions unmitigated and unparalleled in severity, she ordained that this race of toilers should be patient and submissive under austerities; that their pulse should be set to a slow, even rhythm, in harmony with the low key in which Nature spoke to them.

It is impossible to say when an Asiatic stream began to pour into Europe over the arid steppes north of the Caspian. But we know that as early as the fifth century B. C. the Greeks had established trading stations on the northern shores of the Black Sea, and that these in the fourth century had become flourishing colonies through their trade with the motley races of barbarians that swarmed about that region, who by the Greeks were indiscriminately designated by the common name of Scythians.

The Greek colonists, who always carried with them their religion, their Homer, their love of beauty, and the arts of their mother cities, established themselves on and about the promontory of the Crimea, and built their city of Chersonesos where now is Sebastopol. They first entered into wars and then alliances with these Scythians, who served them as middle-men in trade with the tribes beyond, and in time a Graeco-Scythian state of the Bosphorus came into existence.

Herodotus in the fifth century wrote much about these so-called Scythians, whom he divides into the agricultural Scythians, presumably of the Black Lands, and the nomad Scythians, of the Barren Steppes. His extravagant and fanciful pictures of those barbarians have long been studied by the curious; but light from an unexpected source has been thrown upon the subject, and Greek genius has rescued for us the type of humanity first known in Russia.

There are now in the museum at St. Petersburg two priceless works of art found in recent years in a tomb in Southern Russia. They are two vases of mingled gold and silver upon which are wrought pictures more faithful and more eloquent than those drawn by Herodotus. These figures of the Scythians, drawn probably as early as 400 B. C., reproduce unmistakably the Russian peasant of to-day. The same bearded, heavy-featured faces; the long hair coming from beneath the same peaked cap; the loose tunic bound by a girdle; the trousers tucked into the boots, and the general type, not alone distinctly Aryan, but Slavonic. And not only that; we see them breaking in and bridling their horses, in precisely the same way as the Russian peasant does to-day on those same plains. Assuredly the vexed question concerning the Scythians is in a measure answered; and we know that some of them at least were Slavonic.

But the passing illumination produced by the approach of Greek civilization did not penetrate to the region beyond, where was a tumbling, seething world of Asiatic tribes and peoples, Aryan, Tatar, and Turk, more or less mingled in varying shades of barbarism, all striving for mastery.

This elemental struggle was to resolve itself into one between Aryan and non-Aryan—the Slav and the Finn; and this again into one between the various members of the Slavonic family; then a life-and-death struggle with Asiatic barbarism in its worst form (the Mongol), with Tatar and Turk always remaining as disturbing factors.

How, and the steps by which, the least powerful branch of the Slavonic race obtained the mastery and headship of Russia and has come to be one of the leading powers of the earth, is the story this book will try to tell.

[1] In the Tatar language the word Ural signifies "girdle."

In speaking of this eastern half of Europe as Russia, we have been borrowing from the future. At the time we have been considering there was no Russia. The world into which Christ came contained no Russia. The Roman Empire rose and fell, and still there was no Russia. Spain, Italy, France, and England were taking on a new form of life through the infusion of Teuton strength, and modern Europe was coming into being, and still the very name of Russia did not exist. The great expanse of plains, with its medley of Oriental barbarism, was to Europe the obscure region through which had come the Hunnish invasion from Asia.

This catastrophe was the only experience that this land had in common with the rest of Europe. The Goths had established an empire where the ancient Graeco-Scythians had once been. The overthrowing of this Gothic Empire was the beginning of Attila's European conquests; and the passage of the Hunnish horde, precisely as in the rest of Europe, produced a complete overturning. A torrent of Oriental races, Finns, Bulgarians, Magyars, and others, rushed in upon the track of the Huns, and filled up the spaces deserted by the Goths. Here as elsewhere the Hun completed his appointed task of a rearrangement of races; thus fundamentally changing the whole course of future events. Perhaps there would be no Magyar race in Hungary, and certainly a different history to write of Russia, had there been no Hunnish invasion in 375 A. D.

The old Roman Empire, which in its decay had divided into an Eastern and a Western Empire (in the fourth century), had by the fifth century succumbed to the new forces which assailed it, leaving only a glittering remnant at Byzantium.

The Eastern or Byzantine Empire, rich in pride and pretension, but poor in power, was destined to stand for one thousand years more, the shining conservator of the Christian religion (although in a form quite different from the Church of Rome) and of Greek culture. It is impossible to imagine what our civilization would be to-day if this splendid fragment of the Roman Empire had not stood in shining petrifaction during the ages of darkness, guarding the treasures of a dead past.

While these tremendous changes were occurring in the West, unconscious as toiling insects the various peoples in Russia were preparing for an unknown future. The Bulgarians were occupying large spaces in the South. The Finns, who had been driven by the Bulgarians from their home upon the Volga, had centered in the Northwest near the Baltic, their vigorous branches mingled more or less with other Asiatic races, stretching here and there in the North, South, and East. The Russian Slavs, as the parent stem is called, were distributing themselves along a strip of territory running north and south along the line of the Dnieper; while the terrible Turks, and still more terrible Tatar tribes, hovered chiefly about the Black, the Caspian, and the Sea of Azof. No dream of unity had come to anyone. But had there been a forecast then of the future, it would have been said that the more finely organized Finn would become the dominant race; or perhaps the Bulgarian, who was showing capacity for empire-building; but certainly not that helpless Slavonic people wedged in between their stronger neighbors.

But there were no large ambitions yet. It meant nothing to them that there was a new "Holy Roman Empire," and that Charlemagne had been crowned at Rome successor of the Roman Caesars (800 A. D.); nor that an England had just been consolidated into one kingdom. Nor did it concern them that the Saracen had overthrown a Gothic empire in Spain (710). For them these things did not exist. But they knew about Constantinople. The Byzantine Empire was the sun which shone beyond their horizon, and was for them the supreme type of power and earthly splendor. Whatever ambitions and aspirations would in time awaken in these Oriental breasts must inevitably have for their ideal the splendid despotism of the Eastern Caesars. But that stage had not yet been reached.

Although branches of the Slavonic race had separated from the parent stem, bearing different names, the Bohemians on the Vistula, the Poliani in what was to become Poland, the Lithuanians near the Baltic, and minor tribes scattered elsewhere, from the Peloponnesus to the Baltic, all had the same general characteristics. Their religion, like that of all Aryan peoples, was a pantheism founded upon the phenomena of nature. In their Pantheon there was a Volos, a solar deity who, like the Greek Apollo, was inspirer of poets and protector of the flocks—Perun, God of Thunder—Stribog, the father of the Winds, like Aeolus—a Proteus who could assume all shapes—Centaurs, Vampires, and hosts of minor deities, good and evil. There were neither temples nor priests, but the oak was venerated and consecrated to Perun; and rude idols of wood stood upon the hills, where sacrifices were offered to them and they were worshiped by the people.

They believed that their dead passed into a future life, and from the time of the early Scythians it had been the custom to strangle a male and a female servant of the deceased to accompany him on his journey to the other land. The barbarity of their religious rites varied with the different tribes, but the general characteristics were the same, and the people everywhere were profoundly attached to their pagan ceremonies and under the dominion of an intense form of superstition.

Slav society was everywhere founded upon the patriarchal principle. The father was absolute head of the family, his authority passing undiminished upon his death to the oldest surviving member. This was the social unit.

The Commune, or Mir, was only the expansion of the family, and was subject to the authority of a council, composed of the elders of the several families, called the vetché. The village lands were held in common by this association. The territory was the common property of the whole. No hay could be cut nor fish caught without permission from the vetché. Then all shared alike the benefit of the enterprise.

The communes nearest together formed a still larger group called a Volost; that is, a canton or parish, which was governed by a council composed of the elders of the communes, one of whom was recognized as the chief. Beyond this the idea of combination or unity did not extend. Such was the primitive form of society which was common to all the Slavonic branches. It was communistic, patriarchal, and just to the individual. They had no conception of tribal unity, nor of a sovereignty which should include the whole. If the Slav ever came under the despotism of a strong personal government, the idea must come from some external source; it must be imposed, not grow; for it was not indigenous in the character of the people. It would be perfectly natural for them to submit to it if it came, for they were a passive people, but they were incapable of creating it.

The Russian Slavs were an agricultural, not a warlike, people. They fought bravely, but naked to the waist, and with no idea of military organization, so were of course no match for the Turks, well skilled in the arts of war, nor for the armed bands of Scandinavian merchants, who made their territory a highway by which to reach the Greek provinces. All the Slav asked was to be permitted to gather his harvests, and dwell in his wooden towns and villages in peace. But this he could not do. Not only was he under tribute to the Khazarui (a powerful tribe of mingled Finnish and Turkish blood), and harried by the Turks, in the South; overrun by the Finns and Lithuanians in the North; but in his imperfect political condition he was broken up into minute divisions, canton incessantly at war with canton, and there could be no peace. The roving bands of Scandinavian traders and freebooters were alternately his persecutors and protectors. After burning his villages for some fancied offense, and appropriating his cattle and corn, they would sell their service for the protection of Kief, Novgorod, and Pskof as freely as they did the same thing to Constantinople and the Greek cities. In other words, these brilliant, masterful intruders were Northmen, and can undoubtedly be identified with those roving sea-kings who terrorized Western Europe for a long and dreary period.

The disheartened Slavs of Novgorod came to a momentous decision. They invited these Varangians—as they are called—to come and administer their government. They said: "Our land is great and fruitful, but it lacks order and justice. Come—take possession, and govern us." With the arrival from Sweden of the three Vikings, Rurik and his two brothers Sineus and Truvor, the true history of Russia begins, and the one thousandth anniversary of that event was commemorated at Novgorod in the year 1862.

Rurik was the Clovis of Russia. When with his band of followers he was established at Novgorod the name of Russia came into existence, supposedly from the Finnish word ruotsi, meaning rowers or sea-farers. Slavonia was not only christened but regenerated at this period, and infused into it were the new elements of martial order, discipline, and the habit of implicit obedience to a chosen or hereditary chief; and as Rurik's brothers soon conveniently died, their territory also passed to him, and he assumed the title of Grand Prince.

Upon the death of Rurik in 879, his younger brother Oleg succeeded him as regent during the minority of his son Igor; and when two more Varangian brothers—Askold and Dir—in the same manner—except that they were not invited—took possession of Kief on the Dnieper and set up a rival principality in the South with ambitious designs upon Byzantium, Oleg promptly had them assassinated, added their territory to the dominion of Igor, and removed the capital from Novgorod to Kief—saying, "Let Kief be the mother of Russian cities!" Then after selecting a wife named Olga for the young Igor, he turned his attention toward Byzantium, the powerful magnet about which Russian policy was going to revolve for many centuries.

So invincible and so wise was this Oleg that he was believed to be a sorcerer. When the Greek emperor blockaded the passage of the Bosphorus in 907, he placed his two thousand boats (!) upon wheels, and let the sails carry them overland to the gates of Constantinople. The Russian poet Pushkin has made this the subject of a poem which tells how Oleg, after exacting tribute from the frightened Emperor Leo VI., in true Norse fashion, hung his shield upon the golden gates as a parting insult.

Again and again were the Greeks compelled to pay for immunity from these invasions of the Varangian princes. After the death of Oleg, Igor reigned, and in 941 led another expedition against Constantinople which we are told was driven back by "Greek-fire." Then enlisting the aid of the Pechenegs, a ferocious Tatar tribe, he returned with such fury, and inflicted such atrocities, that the Greek Emperor begged for mercy and offered to pay any price to be left alone. The invaders said: "If Caesar speaks thus, what more do we want than to have gold and silver and silks without fighting." A treaty of peace was signed (945), the Russians swearing by their god Perun, and the Greeks by the Gospels; and the victorious Igor turned his face toward Kief. But he was never to reach that place.

The Drevlians, the most savage of the Tatar tribes, had been forced to pay him a large tribute, and were meditating upon their revenge. They said: "Let us kill the wolf or we will lose the flock." They watched their opportunity, seized him, tied him to two young trees bent forcibly together; then, letting them spring apart, the son of Rurik was torn to pieces.

No act of the wise regent Oleg was more fruitful in consequences than the choice of a wife for the young Igor. Olga, who acted as regent during the minority of her son, was destined to be not only the heroine of the Epic Cycle in Russia, but the first apostle of Christianity in that heathen land; canonized by the Church, and remembered as "the first Russian who mounted to the Heavenly Kingdom."

When the Drevlians sent gifts to appease her wrath at the murder of Igor, and offered her the hand of their prince, she had the messengers buried alive. All she asked was three pigeons and three sparrows from every house in their capital town. Lighted tow was tied to the tails of the birds, which were then permitted to fly back to their homes under the eaves of the thatched houses. In the conflagration which followed, the inhabitants were massacred in a pleasing variety of ways; some strangled, some smothered in vapor, some buried alive, and those remaining reduced to slavery.

But an extraordinary transformation was at hand; and this vindictive heathen woman was going to be changed to an ardent convert to the Christian faith. Nestor, who is the Russian Herodotus, relates that she went to Constantinople in 955, to inquire into the mysteries of the Christian Church. The emperor was astonished, it is said, at the strength and adroitness of her mind. She was baptized by the Greek Patriarch, under the new name of Helen, the emperor acting as her godfather.

There were already a few Christians in Kief, but so unpopular was the new religion that Olga's son Sviatoslaf, upon reaching his majority, absolutely refused to make himself ridiculous by adopting his mother's faith. "My men will mock me," was his reply to Olga's entreaties, and Nestor adds "that he often became furious with her" for her importunity.

Sviatoslaf, the son of Igor and Olga, although the first prince to bear a Russian name, was the very type of the cunning, ambitious, and intrepid Northman, and his brief reign (964-972) displayed all these qualities. He defeated the Khazarui, the most civilized of all those Oriental people, and once the most powerful. He subjugated the Pechenegs, perhaps the most brutal and least civilized of all the barbarians. But these were only incidental to his real purpose.

The Bulgarian Empire was large, and had played an important part in the past. It had a Tsar, while Russia had only a Grand Prince, and, although now declining in strength, was a troublesome neighbor to the Greek Empire. The oft-repeated mistake of inviting the aid of another people was committed. Nothing could have better pleased Sviatoslaf than to assist the Greek Empire, and when he captured the Bulgarian capital city on the Danube, and even talked of making it his own capital instead of Kief, it looked as if a great Slav Empire was forming with its center almost within sight of Constantinople. The Greeks were dismayed. With the Russians in the Balkan Peninsula, the center of their dominions upon the Danube—with the Scythian hordes in the South ready to do their bidding—and with scattered Slavonic tribes from Macedon to the Peloponnesos gravitating toward them, what might they not do? No more serious danger had ever threatened the Empire of the East. They rushed to rescue Bulgaria from the very enemy they had invited to overthrow it. After a prolonged struggle, and in spite of the wild courage displayed by Sviatoslaf, he was driven back, and compelled to swear by Perun and Volos never again to invade Bulgaria. If they broke their vows, might they become "as yellow as gold, and perish by their own arms." But this was for Sviatoslaf the last invasion of any land. The avenging Pechenegs were waiting in ambush for his return. They cut off his head and presented his skull to their Prince as a drinking cup (972).

It seems scarcely necessary to call attention to the fact that the transforming energy in this early period of Russian history was not in the native people; but that the Slav, in the hands of his Norse rulers, was as clay in the hands of the potter. In the treaty of peace signed at Kief (945) by the victorious Igor, of the fifty names recorded by Nestor only three were Slavonic and the rest Scandinavian. There can be no doubt which was the dominant race in this the heroic age of Russia.

So we have seen a weaker people submitting to the rule of a stronger, not by conquest, like Spain under the Visigoths; not overrun and overridden as Britain by the Angles and Saxons and Gaul by the Franks; but, in recognition of its own helplessness, voluntarily becoming subject to the control of strangers.

And we see at the same time the brilliant, restless Norseman, with no plan of establishing a racial dominion, but simply in the temporary enjoyment of his own warlike and robber instincts, engrafting himself upon a less gifted people, and then adopting its language and customs, letting himself be absorbed into the nationality he has helped to create, and becoming a Russian, with the same facility as Rollo and his sons at the very same period were becoming Frenchmen.

So the scattered clans of the Slav race were roughly drawn together into something resembling a nation by the strong arm of the Scandinavian. But the course of national progress is never a straight one. Nature understands better than we the value of retarding influences, which prevent the too rapid fusing of crude elements. This work of retardation was performed for Russia by Sviatoslaf. When, instead of leaving his dominions to his oldest son, he divided them among the three, he introduced a vicious system which was to become a fatal source of weakness. This is known as the system of Appanages. To his son Yaropolk he gave Kief, to Oleg the territory of the Drevlians, and to Vladimir Novgorod. But as Vladimir quickly assassinated Yaropolk, who had already assassinated Oleg, the injurious results of the system were not directly felt!

Vladimir became the sole ruler. He then started upon a course of unbridled profligacy. He compelled the widow of his murdered brother to marry him—then a beautiful Greek nun who had been captured from Byzantium—then a Bulgarian and a Bohemian wife, until finally his household was numbered by hundreds. But this sensual barbarian began to be conscious of a soul. He was troubled, and revived the worship of the Slav gods; erected on the cliffs near Kief a new idol of Perun, with head of silver and beard of gold. Two Scandinavian Christians were by his orders stabbed at the feet of the idol. Still his soul was unsatisfied. He determined upon a search for the best religion; sent ambassadors to examine into the religious beliefs of Mussulmans, Jews, Catholics, and the Greeks. The splendor of the Greek ceremonial, the magnificence of the vestments, the incense, the music, and the presence of the Emperor and his court, filled the souls of the barbarians with awe—and the final argument of his boyars (or nobles) put an end to doubts: "If the Greek religion had not been the best, your grandmother Olga, the wisest of mortals, would not have adopted it."

Vladimir's choice was made. He would be baptized in the faith of Olga. But this must be done at the hand of the Greek Patriarch; so he would conquer baptism—and ravish it like booty—not beg for it. He besieged and took a Greek city. Then demanded the hand of Anna, sister of the Greek Caesar, threatening in case of refusal to march on Constantinople. Consent was given upon condition of baptism, which was just what the barbarian wanted. So he came back to Kief a Christian, bringing with him his new Greek wife, and his new baptismal name of Basil.

Amid the tears and fright of the people, the idols were torn down; Perun was flogged and thrown into the Dnieper. Then the old pagan stream was consecrated, and men, women, and children, old and young, master and slave, were driven into the river, the Greek priests standing on the banks reading the baptismal service. The frightened Novgorodians were in like manner forced to hurl Perun into the Volkhof, and then, like herded cattle, were driven into the stream to be baptized. The work of Olga was completed—Russia was Christianized (992)!

It would be long before Christianity would penetrate into the heart of the people. As late as the twelfth century only the higher classes faithfully observed the Christian rites; while the old pagan ceremonies were still common among the peasantry. And even now the Saints of the Calendar are in some places only thinly disguised heathen deities and pagan rites and superstitions mingle with Christian observances.

The conversion of Vladimir seems to have been sincere. From being a cruel voluptuary and assassin, he was changed to a merciful ruler who could not bear to inflict capital punishment. He was faithful to his Greek wife Anna. On the spot where he had once erected Perun, and where the two Scandinavians were martyred at his command, he built the church of St. Basil; and he is now remembered only as the saint who Christianized pagan Russia, and revered as the "Beautiful Sun of Kief."

So the two most important events considered thus far in the history of this land have been, first, its military conquest from the North, and second, its ecclesiastical conquest from the South. If the first helped it to become a nation, the second determined the character which that nationality should assume.

To explain one fact by another and unfamiliar and uncomprehended fact is one of the confusing methods of history! In order to know why the adoption of the form of religion known as the Greek Church so powerfully influenced Russian development, one must understand what that faith was and is, and the source of the antagonisms which divided the two great branches of the Church of Christ—the Greek and the Latin.

The cause underlying all others is racial. It is explained in their names. The theology of one had its roots in Greek Philosophy; that of the other in Roman Law. One tended to a brilliant diversity, the other to centralization and unity. One was a group of Ecclesiastical States, a Hierarchy and a Polyarchy, governed by Patriarchs, each supreme in his own diocese; the other was a Monarchy, arbitrarily and diplomatically governed from one center. It was the difference between an archipelago and a continent, and not unlike the difference between ancient Greece and Rome. One had the tremendous principle of growth, stability, and permanence; the other had not.

Such were the race tendencies which led to entirely different ecclesiastical systems. Then there arose differences in dogma; and Rome considered the Church in the East schismatic, and Byzantium held that that of the West was heterodox. They now not only disapproved of each other's methods, but what was more serious, held different creeds. The Latin Church, after its Bishop had become an infallible Pope (about the middle of the fifth century), claimed that the Church in the East must accept his definition of dogma as final.

It was one small word which finally rent these two bodies of Christendom forever apart. It was only the word filioque which made the impassable gulf dividing them. The Latins maintained that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father—and the son; the Greeks that it descended from the Father alone. It was the undying controversy concerning the relations and the attributes of the three Members of the Trinity; and the insoluble question was destined to break up Greek and Catholic Church alike into numberless sects and shades of belief or unbelief; and over this Christological controversy, rivers of blood were to flow in both branches of Christendom.

The theological question involved was of course too subtle for ordinary comprehension. But although men on both sides stood ready to die for the decisions of their councils which they did not understand, there was underlying the whole question the political jealousy existing between the two: Byzantium, embittered by the effacement of its political jurisdiction in the West, exasperated at the overweening pretensions of Roman bishops; Rome, watching for opportunity to cajole or compel the Eastern Church to submit to her authority and headship.

Such was the condition of things when Russia allied herself in that most vital way with the empire in the East. It is impossible to measure the importance of the step, or to imagine what would have been the history of that country had Vladimir decided to accept the religion of Rome and become Catholic, as the Slav in Poland had already done. By his choice not only is it possible that he added some centuries to the life of the Greek Empire itself, but he determined the type of Russian civilization. When she allied herself with Byzantium instead of Rome, Russia separated herself from those European currents from which she was already by natural and inherited conditions isolated. She thus prolonged and emphasized the Orientalism which so largely shaped her destiny, and produced a nationality absolutely unique in the family of European nations, in that there is but one single root in Russia which can be traced back to the Roman Empire; and whereas most of the European civilizations are built upon a Roman foundation, there is only one current in the life of that nation to-day which has flowed from a Latin source: that is a judicial code which was founded (in part) upon Roman law as embodied by Justinian, Emperor of the Empire in the East (527-565).

When Vladimir died, in 1015, the partition of his dominions among numerous heirs inaugurated the destructive system of Appanages. The country was converted into a group of principalities ruled by Princes of the same blood, of which the Principality of Kief was chief, and its ruler Grand Prince. Kief, the "Mother of Cities," was the heart of Russia, and its Prince, the oldest of the descendants of Rurik, had a recognized supremacy over the others; who must, however, also belong to this royal line. No prince could rule anywhere who was not a descendant of Rurik; Kief, the greatest prize of all, going to the oldest; and when a Grand Prince died, his son was not his rightful heir, but his uncle, or brother, or cousin, or whoever among the Princes had the right by seniority. This was a survival of the patriarchal system of the Slavs, showing how the Norse rulers had adapted themselves to the native customs as before stated.

So while in thus breaking up the land into small jealous and rival states independent of each other—with only a nominal headship at Kief—while in this there was a movement toward chaos, there were after all some bonds of unity which could not be severed: A unity of race and language; a unity of historical development; a unity in religion; and the political unity created by the fact that all the thrones were filled by members of the same family, any one of whom might become Grand Prince if enough of the intervening members could—by natural or other means—be disposed of. This was a standing invitation for assassination and anarchy, and one which was not neglected.

Immediately upon the death of Vladimir there commenced a carnival of fraternal murders, which ended by leaving Yaroslaf to whom had been assigned the Principality of Novgorod, upon the throne at Kief.

The "Mother of Russian Cities" began to show the effect of Greek influences. The Greek clergy had brought something besides Oriental Christianity into the land of barbarians. They brought a desire for better living. Learning began to be prized; schools were created. Music and architecture, hitherto absolutely unknown, were introduced. Kief grew splendid, and with its four hundred churches and its gilded cupolas lighted by the sun, was striving to be like Constantinople. Not alone the Sacred Books of Byzantine literature, but works upon philosophy and science, and even romance, were translated into the Slavonic language. Russia was no longer the simple, untutored barbarian, guided by unbridled impulses. She was taking her first lesson in civilization. She was beginning to be wise; learning new accomplishments, and, alas!—to be systematically and judicially cruel!

Nothing could have been more repugnant or foreign to the free Slav barbarian than the penal code which was modeled by Yaroslaf upon the one at Byzantium. Corporal punishment was unknown to the Slav, and was abhorrent to his instincts. This seems a strange statement to make regarding the land of the knout! But it is true. And imprisonment, convict labor, flogging, torture, mutilation, and even the death penalty, came into this land by the way of Constantinople.

At the same time there mingled with this another stream from Scandinavia, another judicial code which sanctioned private revenge, the pursuit of an assassin by all the relatives of the dead; also the ordeal by red-hot iron and boiling water. But to the native Slav race, corporal punishment, with its humiliations and its refinements of cruelty, was unknown until brought to it by stronger and wiser people from afar.

When we say that Russia was putting on a garment of civilization, let no one suppose we mean the people of Russia. It was the Princes, and their military and civil households; it was official Russia that was doing this. The people were still sowing and reaping, and sharing the fruit of their toil in common, unconscious as the cattle in their fields that a revolution was taking place, ready to be driven hither and thither, coerced by a power which they did not comprehend, their horizon bounded by the needs of the day and hour.

The elements constituting Russian society were the same in all the principalities. There was first the Prince. Then his official family, a band of warriors called the Drujina. This Drujina was the germ of the future state. Its members were the faithful servants of the Prince, his guard and his counselors. He could constitute them a court of justice, or could make them governors of fortresses (posadniki) or lieutenants in the larger towns. The Prince and his Drujina were like a family of soldiers, bound together by a close tie. The body was divided into three orders of rank: first, the simple guards; second, those corresponding to the French barons; and, third, the Boyars, the most illustrious of all, second only to the Prince. The Drujina was therefore the germ of aristocratic Russia, next below it coming the great body of the people, the citizens and traders, then the peasant, and last of all the slave.

Yaroslaf, the "legislator," known as the Charlemagne of Russia, died in the year 1054. The Eastern and Western Empires, long divided in sentiment, were that same year separated in fact, when Pope Leo VI. excommunicated the whole body of the Church in the East.

With the death of Yaroslaf the first and heroic period in Russia closes. Sagas and legendary poems have preserved for us its grim outlines and its heroes, of whom Vladimir, the "Beautiful Sun of Kief," is chief. Thus far there has been a unity in the thread of Russian history—but now came chaos. Who can relate the story of two centuries in which there have been 83 civil wars—18 foreign campaigns against one country alone, not to speak of the others—46 barbaric invasions, and in which 293 Princes are said to have disputed the throne of Kief and other domains! We repeat: Who could tell this story of chaos; and who, after it is told, would read it?

It was a vast upheaval, a process in which the eternal purposes were "writ large"—too large to be read at the time. It was not intended that only the fertile Black Lands along the Dnieper, near to the civilizing center at Constantinople, should absorb the life currents. All of Russia was to be vitalized; the bleak North as well as the South; the zone of the forests as well as the fertile steppes. The instruments appointed to accomplish this great work were—the disorder consequent upon the reapportionment of the territory at the death of each sovereign—the fierce rivalries of ambitious Princes—and the barbaric encroachments to which the prevailing anarchy made the South the prey.

By the twelfth century the civil war had become distinctly a war between a new Russia of the forests and the old Russia of the fertile steppes. The cause of the North had a powerful leader in Andrew Bogoliubski. Andrew was the grandson of Monomakh and the son of Yuri (or George) Dolgoruki—both of whom were Grand Princes of extraordinary abilities and commanding qualities. In 1169 Andrew, who was then Prince of Suzdal, came with an immense army of followers; he marched against Kief. The "Mother of Russian Cities" was taken by assault, sacked and pillaged, and the Grand Principality ceased to exist. Russia was preparing to revolve around a new center in the Northeast; and with the new Grand Principality of Suzdal, far removed from Byzantine and Western civilizations, it looked like a return toward barbarism, but was in fact the circuitous road to progress. The life of the nation needed to be drawn to its extremities, and the ambitious Andrew, who assumed the title and authority of Grand Prince, had established a line which was destined to lead to the Czars of future Russia.

The Principality of Novgorod had from a remote antiquity been the political center of Northern, as was Kief of Southern Russia. It was the Novgorodians who invited the Norse Princes to come and rule the land; and it was the Novgorodians who were their least submissive subjects. When one of the Grand Princes proposed to send his son, whom they did not want, to be their Prince, they replied: "Send him here if he has a spare head." It was a fearless, proud republic, as patriotic and as quarrelsome as Florence, which it somewhat resembled. Their Prince was in reality a figurehead. He was considered essential to the dignity of the state, but his fortunes were in the hands of two political parties, of which he represented the party in the ascendant. Novgorod was a commercial city—its life was in its trade with the Orient and the Greek Empire, and like the Italian cities, its politics were swayed by economic interests. Those in trade with the East through the Volga desired a Prince from one of the great families about that Oriental artery in the Southeast; while those whose fortunes depended upon the Greeks preferred one from Kief or the principalities on the Dnieper. When one party fell, the Prince fell with it, and as the formula expressed it, they then "made him a reverence, and showed him the way out of Novgorod"—or else held him captive until his successor arrived.

Princes might come, and Princes might go, but an irrepressible spirit of freedom "went on forever"; the reigns all too short and troubled to disturb the ancient liberties and customs of the republic. No Grand Prince was ever powerful enough to impose upon them a Prince they did not want, and no Prince strong enough to oppose the will of the people; every act of his requiring the sanction of their posadnik, a high official—and every decision subject to reversal by the Vetché, the popular assembly. The Vetché was, in fact, the real sovereign of the proud republic which styled itself, "My Lord Novgorod the Great." Such was the remarkable state which played an important, and certainly the most picturesque, part in the history of Russia.

The first thought of the new Grand Prince at Suzdal was to prevent the possible rivalry of this arrogant principality in the North, by conquering it and breaking its spirit. He was also resolved to break thoroughly with the past, to destroy the system of Appanages, and had conceived the idea of the modern undivided state. He removed his capital from the old town of Suzdal, which had its Vetché or popular assembly, to Vladimir, which had had none of these things, assigning as his reason, not that he intended to be sole master and free from all ancient trammels—but that the Mother of God had come to him in a dream and commanded him so to do! But an end came to all his dreams and ambitions. He was assassinated in 1174 by his own boyars, who were exasperated by his subversive policy and suspicions of his daring reforms.

With the setting of the currents of Russian national life toward the North, there was awakened in Europe a vague sense of danger. Not far from Novgorod, on and about the shores of the Baltic, were various tributary Slav tribes, mingled with pagan Finns. This was the only point of actual contact, the only point without natural protection between Russia and Europe, and it must be guarded. German merchants, hand in hand with Latin missionaries, invaded a strip of disputed territory, and, under the cloak of Christianity, commenced a—conquest. A Latin Church became also a fortress; and the fortress soon expanded into a German town, and these crept every year farther and farther into the East. In order to quell the resistance of native Finns and Slavs, there was created, and authorized by the Pope, an order of knighthood, called the "Sword-Bearers," with the double purpose of driving back the Slavonic tide which threatened Germany and at the same time Christianizing it. These were the "Livonian Knights," who came from Saxony and Westphalia, armed cap-à-pie, with red crosses embroidered upon the shoulder of their white mantles. Then another order was created (1225), the "Teutonic Order," wearing black crosses on their shoulders, which, after fraternizing with the Livonian Knights, was going to absorb them—together with some other things—into their own more powerful organization. Russia had no armed warriors to meet these steel-clad Germans and Livonians. She had no orders of chivalry, had taken no part in the Crusades, the far-off echoes of which had fallen upon unheeding ears. The Russians could defend with desperate courage their own flimsy fortifications of wood, earth, and loose stones; but they could not pull down with ropes the solid German fortresses of stone and cement, and their spears were ineffectual upon the shining armor. Their conquest was inevitable; the conquered territory being divided between the knights and the Latin Church. So Königsberg and many other Russian towns were captured and then Teutonized, by joining them to the cities of Lubeck, Bremen, Hamburg, etc., in the "Hanseatic League."

This conquest was of less future importance to Russia than to Western Europe. It contained the germ of much history. The territory thus wrested from Russia became the German state of Prussia; and a future master of the Teutonic order, a Hohenzollern, was in later years its first King; and this was the beginning of the great German Empire which confronts the Empire of the Czar to-day.

So the conquest by the German Orders was added to the other woes by which Russia was rent and torn after the death of her Grand Prince at Suzdal. To us it all seems like an unmeaning panorama of chaos and disorder. But to them it was only the vicissitudes naturally occurring in the life of a great nation. They were proud of their nationality, which had existed nearly as long as from Columbus to our own day. They gloried in their splendid background of great deeds and their long line of heroes reaching back to Rurik. Their Princes were proud and powerful—their followers (the Drujiniki)—noble and fearless—who could stand before them? They would have exchanged their glories for those of no nation upon the earth, except perhaps that waning empire of the Caesars at Constantinople!

Such was the sentiment of Russian nationality at the time when its overwhelming humiliation suddenly came, a degrading subjection to Asiatic Mongols, which lasted 250 years.

In the year 1224 there appeared in the Southeast a strange host who claimed the land of the Polovtsui, a Tatar clan which had been for centuries encamped about the Sea of Azof. The Russian chronicler naively says: "There came upon us for our sins unknown nations. God alone knew who they were, or where they came from—God, and perhaps wise men, learned in books"—which it is evident the chronicler was not! The invaders were Mongols—that branch of the human family from which had come the Tatars and the Huns, already familiar to Russia. But these Mongols were the vanguard of a vast army which had streamed like a torrent through the heart of Asia, conquering as it came; gathering one after another the Asiatic kingdoms into an empire ruled by Genghis Khan, a sovereign who in forty years had made himself master of China and the greater part of Asia—saying: "As there is only one Sun in Heaven, so there should be only one Emperor on the Earth"; and when he died, in 1227, he left the largest empire that had ever existed, and one which he was preparing to extend into Western Europe.

It was the court of this great sovereign which, in 1275, was visited by the Venetian traveler Marco Polo. This was the far-off Cathay, descriptions of which fired the imagination of Europe, and awoke a consuming desire to get access to its fabulous riches, and which two centuries later filled the mind of Columbus with dreams of reaching that land of wonders by way of the West.

The Polovtsui appealed to the nearest principalities for help, offering to adopt their religion and to become their subjects, in return for aid. When several Princes came with their armies to the rescue, the Mongols sent messengers saying: "We have no quarrel with you; we have come to destroy the accursed Polovtsui." The Princes replied by promptly putting the ambassadors all to death. This sealed the fate of Russia. There could be no compromise after that. Upon that first battlefield, on the steppes near the sea of Azof, there were left six Princes, seventy chief boyars, and all but one-tenth of the Russian army.

After this thunderbolt had fallen an ominous quiet reigned for thirteen years. Nothing more was heard of the Mongols—but a comet blazing in the sky awoke vague fears. Suddenly an army of five hundred thousand Asiatics returned, led by Batui, nephew of the Great Khan of Khans.

It was the defective political structure of Russia, its division into principalities, which made it an easy prey. The Mongols, moving as one man, took one principality at a time, its nobles and citizens alone bearing arms, the peasants, by far the greater part, being utterly defenseless. After wrecking and devastating that, they passed on to the next, which, however desperately defended, met the same fate. The Grand Principality was a ruin; its fourteen towns were burned, and when, in the absence of its Grand Prince, Vladimir the capital city fell, the Princesses and all the families of the nobles took refuge in the cathedral and perished in the general conflagration (1238). Two years later Kief also fell, with its white walls and towers embellished by Byzantine art, its cupolas of gold and silver. All was laid in the dust, and only a few fragments in museums now remain to tell of its glory. The annalist describes the bellowings of the buffaloes, the cries of the camels, the neighing of the horses, and howlings of the Tatars while the ancient and beautiful city was being laid low.

Before 1240 the work was complete. There was a Mongol empire where had been a Russian. Then the tide began to set toward Western Europe. Isolated from the other European states by her religion, Russia had suffered alone. No Europe sprang to her defense as to the defense of Spain from the Saracens. Not until Poland and Hungary were threatened and invaded did the Western Kingdoms give any sign of interest. Then the Pope, in alarm, appealed to the Christian states. Frederick II. of Germany responded, and Louis IX. of France (Saint-Louis) prepared to lead a crusade. But the storm had spent its fury upon the Slavonic people, and was content to pause upon those plains which to the Asiatic seemed not unlike his own home.

Amid the wreck of principalities there was one state remaining erect. Novgorod was defended by its remoteness and its uninviting climate. The Mongols had not thought it worth while to attempt the reduction of the warlike state, so the stalwart Republic stood alone amid the general ruin. All the rest were under the Tatar yoke. Of Princes there were none. All had either been slaughtered or fled. Proud boyars saw their wives and daughters the slaves of barbarians. Delicate women who had always lived in luxury were grinding corn and preparing coarse food for their terrible masters.

After the conquest was completed the Mongol sovereign exacted only three things from the prostrate state—homage, tribute, and a military contingent when required. They might retain their land and their customs, might worship any god in any way; their Princes might dispute for the thrones as before; but no Prince—not the Grand Prince himself—could ascend a throne until he had permission from the Great Khan, to whom also every dispute between royal claimants must be deferred. Then when finally the messenger came from the sovereign with the yarlik, or royal sanction, the Prince must listen kneeling, with his head in the dust. And if then he was invited (?) to the Mongol court to pay homage, he must go, even though it required (as Marco Polo tells us) four years to make the journey across the plains and the mountains and rivers and the Great Desert of Gobi!

When Yaroslaf II., third Grand Prince of Suzdal, succeeded to the Principality, he was invited to pay this visit. After reaching there, and after all the degrading ceremonies to which he was subjected—kissing the stirrup of his Suzerain, and licking up the drops which fell from his cup as he drank—then this Prince of the family of Rurik perished from exhaustion in the Desert of Gobi on his return journey. But this was not all. The yoke was a heavy as well as a degrading one. Each Prince with his Drujina must be always ready to lead an army in defense of the Mongol cause if required; and, last of all, the poll-tax bore with intolerable weight upon everyone, rich or poor, excepting only the ecclesiastics and the property of the Greek Church, which with a singular clemency they exempted.

What sort of a despotism was it, and what sort of a being, that could wield such a power from such a distance! that, across a continent it took four years to traverse, could compel such obedience; could by a word or a nod bring proud Princes with rage and rebellion in their hearts to his court—not to be honored and enriched, but degraded and insulted; then in shame to turn back with their boyars and retinues,—if indeed they were permitted to go back at all,—one-half of whom would perish from exhaustion by the way. What was the secret of such a power? Even with all the modern appliances for conveying the will of a sovereign to-day, with railroads to carry his messengers and telegraph wires to convey his will, would it be conceivable to exert such an authority?

And—listen to the language of a proud Russian Prince at the Court of the Great Khan: "Lord—all-powerful Tsar, if I have done aught against you, I come hither to receive life or death. I am ready for either. Do with me as God inspires you." Or still another: "My Lord and master, by thy mercy hold I my principality—with no title but thy protection and investiture—thy yarlik; while my uncle claims it not by your favor but by right!" It was such pleading as this that succeeded; so it is easy to see how Princes at last vied with each other in being abject. In this particular case the presumptuous uncle was ordered to lead his victorious nephew's horse by the bridle, on his way to his coronation at Moscow. So the path to success was through the dust, and it was the wily Princes of Moscow that most patiently traveled that road with important results to Russia.

Novgorod, as we have said, had alone escaped from these degradations. Her Prince Alexander was son of Yaroslaf, the Grand Prince who perished in the desert on his way home. At the time of the invasion Alexander was leading an army against the Swedes and the Livonian Knights in defense of his Baltic provinces. It was Latin Christianity versus Greek, and by a great victory upon the banks of the Neva he earned undying fame and the surname of Nevski. Alexander Nevski is remembered as the hero of the Neva and of the North; yet even he was finally compelled to grovel at the feet of the barbarians. Novgorod alone had stood erect, had paid no tribute and offered no homage to the Khan. At last, when its destruction was at hand, thirty-six years after the invasion, Nevski had the heroism to submit to the inevitable. He advised a surrender. It needed a soul of iron to brave the indignation of the republic. "He offers us servitude!" they cried. The Posadnik who conveyed the counsel to the Vetché was murdered on the spot. But Alexander persisted, and he prevailed. His own son refused to share his father's disgrace, and left the state. Again and again the people withdrew the consent they had given. Better might Novgorod perish! But finally, when Alexander Nevski declared that he would go, that he would leave them to their fate, they yielded, and the Mongols came into a silent city, passing from house to house making lists of the inhabitants who must pay tribute.

Then the unhappy Prince went to prostrate himself before the Khan at Saraï. But his heart had broken with his spirit. He had saved his state, but the task had been too heavy for him. He died from exhaustion on his journey home (1260).

On account of internal convulsions in the Great Tatar Empire, now united by Kublai-Khan, the fourth in succession from Genghis-Khan, the Golden-Horde had separated from the parent state, and its Khan was absolute ruler of Russia. So from this time the ceremony of investiture was performed at Saraï; and the humiliating pilgrimages of the Princes were made to that city.

The religion of the Mongols at the time of the invasion was a paganism founded upon sorcery and magic; but they soon thereafter adopted Islamism, and became ardent followers of the Prophet (1272). Although they never attempted to Tatarize Russia, 250 years of occupation could not fail to leave indelible traces upon a civilization which was even more than before Orientalized. The dress of the upper classes became more Eastern—the flowing caftan replaced the tunic, the blood of the races mingled to some extent; even the Princes and boyars contracting marriages with Mongol women, so that in some of the future sovereigns the blood of the Tatar was to be mingled with that of Rurik.

A weaker nation would have been crushed and disheartened by such calamities as have been described. But Russia was not weak. She had a tremendous store of vigor for good or for evil. Life had always been a terrible conflict, with nature and with man, and when there had been no other barbarians to fight, they had fought each other. Every muscle and every sinew had always been in the highest state of activity, and was toughened and strong, with an inextinguishable vitality. Such nations do not waste time in sentimental regrets. Their wounds, like those of animals, heal quickly, and they are urged on by a sort of instinct to wear out the chains they cannot break. By the time Novgorod came under the Tatar yoke the entire state had adjusted itself to its condition of servitude. Its internal economy was re-established, the peasants, in their Mirs or communes, sowed and reaped, and the people bought and sold, only a little more patient and submissive than before. The burden had grown heavier, but it must be borne and the tribute paid. The Princes, with wits sharpened by conflict, fought as they always had, with uncles, cousins, and brothers for the thrones; and then governed with a severity as nearly as possible like the one imposed upon themselves by their own master—the Great Khan.

The germ of future Russia was there; a strong, patient, toiling people firmly held by a despotic power which they did not comprehend, and uncomplainingly and as a matter of course giving nearly one-half of the fruit of their toil for the privilege of living in their own land! When her sovereigns had Tatar blood in their veins and Tatar ideals in their hearts, Russia was on the road to absolutism. All things were tending toward a centralized unity of an iron and inexorable type—a type entirely foreign to the natural free instincts of the Slavonic people themselves.

The tumultuous forces in Russia, never at rest, were preparing to revolve about a new center. Whether this would be in the East or West was long in doubt, and only decided after a prolonged struggle. Western Russia grouped itself about the state of the Lithuanians on the Baltic, and Eastern Russia about that of Muscovy.

The Lithuanians had never been Christianized; they still adored Perun and their pagan deities; and the only bond uniting them with Russia was the tribute they had for years reluctantly paid. They were ripe for rebellion; and when after long years of conflict with the Livonian and Teutonic Orders, Latin Christianity obtained some foothold in their land, they began to gravitate toward Catholic Poland instead of Greek Russia; and when a marriage was suggested which should unite Poland and Lithuania under their Prince Iagello, who should reign over both at Cracow, and at the same time give them their own Grand Prince, they consented. The forces instigating this movement had their source at Rome, where the Pope was unceasingly striving, through Germany and Poland, to carry the Latin cross into Russia. Again and again had the Greek Church repulsed the offers of reconciliation and union made by Rome. So, much was hoped from the proselyting of the German Orders, and of Catholic Poland, and from the union effected by the marriage of the Lithuanian Prince Iagello with the Polish Queen Hedwig.

The threads composing this network of policies in the West were altogether ecclesiastical, until Lithuania began to feel strong enough to wash off her Christian baptism and to indulge in ambitious designs of her own: to struggle away from Poland, and to commence an independent and aggressive movement against Russia.

There was an immense vigor in this movement. The power in the West, sometimes Catholic and at heart always pagan, absorbed first towns and cities and then principalities. It began to be a Lithuanian conquest, and overshadowed even Mongol oppression. The Mongol wanted tribute; while Lithuania wanted Russia! But one of the gravest dangers brought by this war between the East and the West was the standing opportunity it offered to conspirators. An army of disaffected uncles and nephews and brothers, with their followers, could always find a refuge, and were always plotting and intriguing and negotiating with Lithuania and Poland, ready even to compromise their faith, if only they might ruin the existing powers.

Such, in brief, was the great conflict between the East and West, during which Moscow came into being as the supreme head, the living center and germ of Russian autocracy.

It seems to have been the extraordinary vitality of one family which twice changed the currents of national life: first drawing them from Kief to Suzdal, then from Suzdal toward Moscow, and there establishing a center of growth which has expanded into Russia as it exists to-day. This was the family of Dolgoruki. Monomakh and his son George Dolgoruki, the last Grand Prince of Kief, were both men of commanding character and abilities; and it will be remembered that it was Andrew Bogoliubski, the son of George (or Yuri), who effected the revolution which transferred the Grand Principality from Kief to Suzdal in the bleak North. Alexander Nevski, the hero of the Neva and of Novgorod, was the descendant of this Andrew (of Suzdal), and it was the son of Nevski who was the first Prince of Moscow and who there established a line of Princes which has come unbroken down to Nicholas II. Contrary to all the traditions of their state this dominating family was going to establish a dynasty, and again to remove the national life to a new center, in a Grand Principality toward which all of Russia was gradually but inevitably to gravitate until it became Muscovite.

The city which was to exert such an influence upon Russia was founded in 1147 by George (or Yuri) Dolgoruki, the last Grand Prince of Kief. The story is that upon arriving once at the domain of a boyar named Kutchko, he caused him for some offense to be put to death; then, as he looked out upon the river Moskwa from the height where now stands the Kremlin, so pleased was he with the outlook that he then and there planted the nucleus of a town. Whether the death of the boyar or the purpose of appropriating the domain came first, is not stated; but upon the soil freshly sprinkled with human blood arose Moscow.

The town was of so little importance that its destruction by the Tatars in 1238 was unobserved. In 1260, when Alexander Nevski died, Moscow, with a few villages, was given as a small appanage or portion to his son Daniel. Nevski, it must be remembered, was a direct descendant of Monomakh, and of George Dolgoruki, the founder of Moscow. So the first Prince of Moscow was of this illustrious line, a line which has remained unbroken until the present time.

When Daniel commenced to reign over what was probably the most obscure and insignificant principality in all Russia, it was surrounded by old and powerful states, in perpetual struggle with each other. The Lithuanian conquest was pressing in from the West and assuming large proportions; while embracing the whole agitated surface was the odious enslavement to the Mongols and their oft-recurring invasions to enforce their insolent demands.

The building of the Russian Empire was not a dainty task! It was not to be performed by delicate instruments and gentle hands. It needed brutal measures and unpitying hearts. Nor could brute force and cruelty do it alone; it required the subtler forces of mind—cold, calculating policies, patience, and craft of a subtle sort. The Princes of Russia had long been observant pupils, first at Constantinople, and later at the feet of the Khans. They could meet cruelty with cruelty, cunning with cunning. But it was the Princes of Moscow who proved themselves masters in these Oriental arts. Their cunning was not of the vulgar sort which works for ends that are near; it was the cunning which could wait, could patiently cringe and feign loyalty and devotion, with the steady purpose of tearing in pieces. Added to this, they had the intelligence to divine the secret of power. Certain ends they kept steadily in view. The old law of succession to eldest collateral heir they set aside from the outset; the principality being invariably divided among the sons of the deceased Prince. Then they gradually established the habit of giving to the eldest son Moscow, and only insignificant portions to the rest. So primogeniture lay at the root of the policy of the new state—and they had created a dynasty.

Then their invariable method was by cunning arts to embroil neighboring Princes in quarrels, and so to ingratiate themselves with their master the Khan, that when they appeared before him at Saraï—as they must—for his decision, while one unfortunate Prince (unless perchance he was beheaded and did not come away at all) came away without his throne, the faithful Prince of Moscow returned with a new state added to his territory and a new title to his name! Was he not always ready, not only to obey himself, but to enforce the obedience of others? Did he not stand ready to march against Novgorod, or any proud, refractory state which failed in tribute or homage to his master the Khan? No gloomier, no darker chapter is written in history than that which records the transition of Russia into Muscovy. It was rooted in a tragedy, it was nourished by human blood at every step of its growth. It was by base servility to the Khans, by perfidy to their peers, by treachery and by prudent but pitiless policy, that Moscow rose from obscurity to the supreme headship—and the name of Muscovy was attained.

There was a line of eight Muscovite Princes from Daniel (1260) to the death of Vasili (1462), but they moved as steadily toward one end as if one man had been during those two centuries guiding the policy of the state. The city of Moscow was made great. The Kremlin was built (1300)—not as we see it now. It required many centuries to accumulate all the treasures within that sacred inclosure of walls, crowned by eighteen towers. But with each succeeding reign there arose new buildings, more and more richly adorned by jewels and by Byzantine art.

Then the city became the ecclesiastical center of Russia, when the Metropolitan, second only to the Great Patriarch at Constantinople, was induced to remove to Moscow from Vladimir, capital of the Grand Principality. This was an important advance; for in the train of the great ecclesiastic came splendor of ritual, and wealth and culture and art; and a cathedral and more palaces must be added to the Kremlin. In 1328 Ivan I., the Prince of Moscow, being the eldest descendant of Rurik, fell heir by the old law of succession to the Grand Principality. So now the Prince of Moscow was also Grand Prince of Vladimir, or of Suzdal, which was the same thing; and as he continued to dwell in his own capital, the Grand Principality was ruled from Moscow. The first act of this Grand Prince was to claim sovereignty over Novgorod. The people were deprived of their Vetché and their posadnik, while one of his own boyars represented his authority and ruled as their Prince. Then the compliant Khan bestowed upon his faithful vassal the triple crown of Vladimir, Moscow, and Novgorod, to which were soon to be added many others.