The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Halo, by Bettina von Hutten This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Halo Author: Bettina von Hutten Illustrator: B. Martin Justice Release Date: October 20, 2005 [EBook #16909] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HALO *** Produced by Kathryn Lybarger, Paul Ereaut and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

A straight stretch of dusty Norman road dappled with grotesque shadows of the ancient apple-trees that, bent as if in patient endurance of the weight of their thick-set scarlet fruit, edged it on both sides.

Under one of the trees, his back against its gnarled trunk, sat an old man playing a cracked fiddle.

He played horribly, wrenching discords from the poor instrument, grinning with a kind of vacant malice as it shrieked aloud in agony, and rolling in their scarred sockets his long-blind eyes.

Beside him, his tongue hanging out, his head bent, sat a yellow dog with a lead to his collar. Far and wide there was to be seen no other living thing, and in the apple-scented heat the screeching of the violin was like the resentful cries of some invisible creature being tortured.

"Papillon, mon ami," said the old man, ceasing playing for a moment, "we are wasting time; the shadows are coming. See the baby shadow apple-trees creeping across the road."

The yellow dog cocked an ear and said nothing.

"Time should never be lost, petit chien jaune—never be lost."

Then with a shrill laugh he ground his bow deep into the roughened strings, and the painful music began again.

The yellow dog closed his eyes....

Suddenly far down the road appeared a low cloud of white dust, advancing rapidly, and until it was nearly abreast of the fiddler, noiselessly, and then, with the cessation of a quick padding sound of bare feet, appeared a small, black-smocked boy, his sabots under his arm, his face white with anger.

"Stop it!" he cried, "stop it!"

The old man turned. "Stop what, little seigneur," he asked with surly amusement. "Does the high road belong to you?"

"You must stop it, I say, I cannot bear it."

The fiddler rose and danced about scraping more hideously than before. "Ho, ho," he laughed, "ho, ho, ho, ho!"

The child threw his arms over his head in a gesture of unconscious melodrama. "I cannot bear it—you are hurting it—I—I will kill you if you do not stop." And he flew at his enemy, using his close-cropped bullet-head as a battering ram.

For some seconds the absurd battle continued, and then, as unexpectedly as he had begun it, the boy gave it up, and as the fiddler laughed harshly, and the fiddle screeched, threw himself on the warm, dusty grass and cried aloud.

There was a pause, after which, in silence, the old man groped his way to the boy and knelt by him. "Hush, mon petit," he beseeched, "old Luc-Ange is a monster to tease you. Do not cry, do not cry."

A curious apple, leaning over to listen, fell from its bough and dropped with a thud into the grass.

The little Norman sat up. "I am not crying," he declared, turning a brown, pugnacious face towards his late foe, "see, there are no tears."

The man touched his cheeks and eyelids delicately with his dirty fingers. "True—no tears. But—why, why did you——"

"I was screaming because that noise was so horrible."

"And—that noise gave you pain?"

Bullet-Head frowned. Like all Normans, he resented his mental privacy being intruded on by questions.

"Not pain; it gives me a horrible, hollow feeling in my inside," he admitted grudgingly, "just under the belt."

After a moment he added, his dark eyes fixed angrily on the violin, "I hate violins; they are dreadful things. M. Chalumeau had one. I broke it."

The blind man laughed gratingly. "Because it made such a horrible noise?"

"Yes."

Another pause, and then the man's expression of vacant malice turned to one pitiful to see, one of indistinct yearning. "Give it to me," he muttered, "they say I am half mad, and perhaps I am, but—I think I could play once——" The yellow dog snapped at a fly, and his master turned towards him, adding, "Before your time, Papillon, long before."

The bow touched the strings once or twice gently and ineffectively, and then, his lips twitching, his eyelids as much closed as the scars on their lids allowed them to be, he began to play.

It was the playing of one who had forgotten nearly everything of his art, but it was sweet and true and strangely touching. To the boy it was a miracle. He listened with the muscles of his face drawn tight in an effort at self-control unusual in such a child, his square, brown hands digging convulsively into the dry earth under the grass beside him. And as the shadows of the trees crept over the road, and the oppressive heat began to relent a little, the plaintive music went on and on, and scant, painful tears stood on the player's face.

At last he stopped, and frowning in a puzzled way, said hoarsely, "What is the matter, Papillon, where have we got to?"

The dog's tail stirred in answer, and at the same moment the other listener burst into loud, emotional sobs, and the old man remembered. "That's it, that's it. It's the boy who made me remember—'Te rappelles tu, te rappelles—tu, ma Toinon?' Why do you cry, little boy? Why do you cry?"

The boy dried his eyes on his smock sleeve.

"It—I am ten, too big to cry," he returned, with the evasion born in him of his race, adding with the frankness peculiar to his own personality, "but I did cry. It was beautiful."

The old man rose, and took up the dog's lead.

"Beautiful. Yes. There was a time——" He paused for a second. "What is your name, little one?"

"Victor-Marie Joyselle."

"Eh b'en, Victor-Marie Joyselle, listen to me. When you have learned to play the violin——" but Bullet-Head interrupted him.

"How do you know that I mean to learn to play the violin?" he queried, drooping the outer corners of his eyelids in quick suspicion, "I did not say so."

"I know. And when you have learned, remember me. And never let anything—come here that I may put my hand on your head that you do not forget—never let anything—duty, pleasure, money, or—or a woman—come between you and your music."

The boy stared seriously into the strange face bent over him, the face from which so much that was bad seemed for the moment to have been swept away by the luminousness of the idea that had come to the half-idiotic brain.

"'Duty, pleasure, money or—'"

"Or a woman" cried the fiddler, his face contorting with anger. "God curse them all!" Muttering and frowning he jerked at his dog. "Come, Papillon, come; we must be getting on, it is late. Petit chien jaune, petit chien jaune."

The dog trotting discreetly at the end of the taut lead, the old man slouched up the road, brandishing his violin aimlessly and talking aloud as he went.

"I ask myself," said the little Norman, "how he knew."

Then, for he was no longer in haste, he stepped into his green sabots and started homeward, biting into the apple that had listened.

The Earl of Kingsmead lay flat on his stomach on the warm, short grass by the carp-pond, and studied therein the ponderous manoeuvres of an ancient fish, believed by the people thereabouts to be something over two hundred years old. Carp had a great charm for Lord Kingsmead; so had electricity; so had toads; so had buns, and stable-boys, and pianolas, and armour, and curates, and chocolates.

Everything was full of interest to this interesting nobleman, and the most beautiful part of it was that there was beyond Kingsmead and the very restricted area of London that he had hitherto been allowed to investigate, a whole world full of things strange, undreamed-of, delightful, and, best of all, dangerous, to the study of which he meant to dedicate every second of the time that spread between that moment as he lay on the grass and the horrid hour when he should be carried to the family vault surrounded by sobbing relations.

For Tommy Kingsmead was one of those most unusual persons who understand the value of life as it dribbles through their fingers in seconds, instead of, like most people, losing the vibrant present in a useless (because invariably miscalculated) study of the future.

This morning he had devoted to a keen investigation of several matters of palpitating interest.

Had Fledge, the butler, who had apparently been at Kingsmead since the beginning of the world, any teeth, or did his flexible, long lips hide only gums? Until that day the problem had never suggested itself to Fledge's master, but when it did, it roused in him a passion of curiosity that had to be satisfied, after the failure of a series of diplomatic attempts by the putting of a plain question.

"I say, Fledge."

"My lord?"

"—You never do really open your mouth, you know—except, I suppose, when you eat——"

"Yes, my lord."

"You just, well—fumble with your lips. So—I say, Fledge, have you any teeth?"

And Fledge, possibly because he was a man of principle, but probably also because he suspected that his master's next words might take the form of an order to open his mouth, told the truth. He had three teeth only.

"And look here, Fledge, why do William's toes turn out at such a fearful angle?"

Pledge's heart was in the plate-closet at that moment, but his patience was monumental.

"I don't know, my lord—unless it's because 'e's only just left off being knife-boy—they get used to standing at the sink a-washing up, my lord, and William's feet is large, so I dessay he turned 'is toes out in order to get near and not splash."

This elucidation appeared plausible as well as interesting to Kingsmead, and he felt that in learning something of the habits of the genus knife-boy he had added to his stock of human information, which he undoubtedly had.

Then at lunch there had been the little matter of Bicky's dressmaker's bill. The mater had been her crossest, and Bicky her silentest, and the bill, discussed in French, a disgusting and superfluous language, the acquirement of which Kingsmead had used much skill in evading, lay on the table. It lay there, forgotten, after the two ladies had left the room, but Kingsmead was a gentleman. So, later he had sought out his sister and coaxed her into telling him the hair-raising sum to which amounted the "two or three frocks" she had had that summer.

He had also learned that Mr. Yelverton, the Carrons, the Newlyns, and Théo Joyselle were coming that afternoon, and what the real reason was that had made the Frenshaws wire they could not come. It had not at all surprised him to hear that the reason given in the wire was utterly false, for, like other people, Kingsmead was bound by his horizon.

On the whole, his day had been a busy one, and the valuable acquisitions of knowledge that I have mentioned, together with a few scraps of information on stable and garage matters, had brought him quite comfortably up to four o'clock, when, as he idled across the lawn, that rum old carp had caught, and held, his eye.

It was a very warm day in October, a day most unusual in its mellow beauty; soft sunshine lay on the lawn and lent splendour to the not very large Tudor house off to the left.

The air of gentle, self-satisfied decrepitude worn by the old place was for the moment lost, and it looked new, clean-cut and almost gaudy, as it must have done in the distant days when it was young. It was a becoming day for the ancient building, as candle-light is becoming to an old beauty and brings back a fleeting and pathetic air of youth to her still lovely features.

Above, the sky was very blue, and the ruminating silence was broken only by the honk-honk of a distant motor. The carp, impeded in his lethargic progress by the thick stem of a water-lily, had stood still (if a fish can be said to stand) for a century—nearly five minutes—his silly old nose pointing stubbornly at the obstacle.

"It won't move, so you'll have to," observed Kingsmead, wriggling a little nearer, "Oh, I say do buck up, or you'll never get there——"

And the carp, quite as if he understood, did buck up, and slid away into the shadow of the rhododendrons.

Kingsmead rose slowly and picked up his cap. What should he do next? The puppies weren't bad, nor the new under-gardener who swore so awfully at his inferior, nor——

"Hello, Tommy."

"Hello, Bicky."

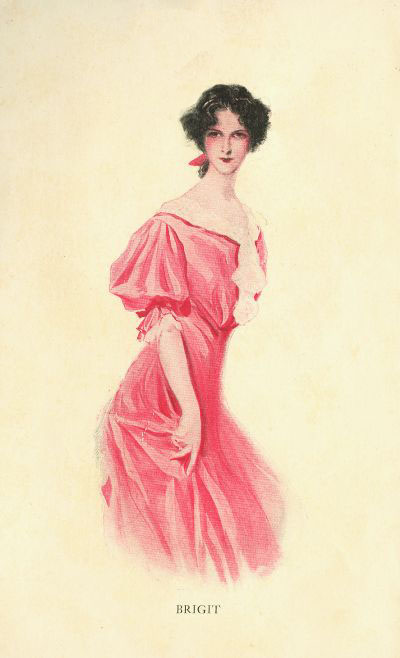

Brigit Mead wore a short blue skirt, brown shoes, a pink wash-silk blouse made like a man's shirt, and a green felt hat that obviously belonged to someone else. She was dressed like thousands of English girls, and she looked as though the blood in her might be any in the world but English. Hers was an enigmatic, narrow, high-bred face, crowned by masses of dry black hair, and distinguished from any other face most people had ever seen by the curved line of her little nose and the colourless darkness of her very long, half-closed, heavily lashed eyes. She looked sulky, disagreeable, and secretive, but she was strangely and undeniably beautiful. Her long, thin-lipped mouth was too close shut, but it was of an exquisite satin texture, scarlet in colour, and when she said "Hello, Tommy," it melted into the most enchanting and indescribable curves, showing just a glimpse of pointed white teeth.

Kingsmead studied her gravely for a moment.

"Been crying?"

"Yes."

"That bill?"

"Yes, that bill, you horrid little boy. There's a long worm in your hair."

Kingsmead removed the worm.

"Mater been nasty?"

"Beastly."

"H'm. I say, Bick, I saw Ponty yesterday."

Brigit, who had turned and was gazing across the lawn, looked at him without moving her head, a trick which is not at all English.

"Did you, now?"

"I did. He is dining here, he says. He is also sending you some flowers. I told him," added the boy dreamily, "that we had lots ourselves."

After a moment, as she did not speak, he went on, "Poor old thing, why did you poggle him so awfully, Bicky? You really are a horrid girl, you know."

"I didn't poggle him."

She did not turn, she did not smile, and the sombreness that was the dominant expression of her face was strange to see in a girl of her age.

"Well——" Kingsmead's small countenance, so different from hers in its look of palpitating interest and curiosity, suddenly flushed a deep and a beautiful red. "I say, old girl," he broke out, "are you going to?"

And she, silent and unresponsive as she was, could not avoid answering him.

"Well, Tommy dear—I don't know, but I suppose I shall."

"I don't like him, poor thing, and I wish you—mustn't."

"That's exactly the word. I fear I must." Her eyes nearly closed as she refused to frown. "This kind of thing can't go on for ever."

"You mean the mater. Well, look here, Bicky, she'll be better when Carron is here—she always is."

"Oh, Tommy——"

"But she is. She obeys him rather, don't you think? I suppose because he was a friend of father's. Is she really very bad to-day?"

"Yes."

"Well, why don't you ask him to tell her to chuck it? I say, dear old thing, I wish I were nine years older!"

"If you were, I should be thirty-four!"

"I meant about the beastly money."

She laughed. "Funny little kiddie! You aren't going to have any money either. If we lived within our means we'd be enjoying life in a villa in some horrible suburb. We are hideously poor, Kingsmead."

She so rarely called him by his name that the boy felt alarmed. Pontefract, with his red neck and his short legs, seemed suddenly very near.

"Isn't there anyone else?" he blurted out, as she led the way towards the house. "I mean, any other chap with money?"

"No one with as much. And then, he isn't so very bad, Tommy. He's good-natured. Think of Clandon, or—Negroponte!" Her shudder was perfectly genuine.

"But Pontefract is so thundering old!"

She made no reply, and after a minute he went on: "What about Théo Joyselle?"

"My dear child, he is three years younger than I, even counting in bare years! And in reality I am twenty years too old for him. Silly little boy, don't bother about me." And her face, as she smiled down at her brother, was very pleasant as well as very beautiful.

"But he has money——"

She nodded.

"And——"

"How did you know that, imp?"

"Having eyes to see, I saw. And I'd like to be an In-law to Victor Joyselle. I'd make him play to me all day. I say, I suppose she wouldn't let us run up to hear him to-morrow?"

"Not she."

He sighed, and it was a grown-up sigh issuing from a child's throat, for he loved music and had read the programme.

"How glorious the last one was! Upon my word, if I were you, I'd marry Théo just to be that man's daughter-in-law."

Again she laughed and laid her hand on his head.

"Good old Thomas. He's a Norman peasant, remember—probably eats with his knife. Oh, here's a motor—and it is Théo himself."

"Yes, speak of an angel and you hear his horn."

"Shall I tell him of your plan?" she teased as the motor slowed up.

But Tommy had disappeared, and in his place, small, freckled, and untidy, it is true, but a gentlemanly host welcoming his mother's guest, stood Lord Kingsmead.

Lady Kingsmead was one of those piteous beings, a middle-aged young woman. She was forty-six, but across a considerably-lighted room looked thirty-six. The shock, when one approached her, was so much the greater. Her plentiful, grey-streaked hair dwelt in disgrace behind a glossy transformation, and her face had, from constant massage and make-up, a curious air of not belonging to her any more than did the wavy hair above it.

The lines that the mercifully deliberate on-coming of age draws on all of us were, it is true, nearly obliterated, but in their place was a certain blankness that was very unbeautiful indeed.

However, she liked herself as she made herself, and most people thought her wonderfully young-looking.

The question of age, real and apparent, is a curious one that gives furiously to think, as the French say. No one on earth could consider it an advantage for a child of twelve to wear the facial aspect of a baby of two, nor for a girl of twenty to look like a child of ten, but later on this equation apparently fails to hold good, and Lady Kingsmead in appearing (at a little distance) nearly ten years her own junior, was as vastly pleased with herself as, considering the time and the care she devoted to the subject, she deserved to be.

As she came downstairs the evening of the day of her daughter's unusually confidential conversation with her son, Brigit joined her.

"Ugh, mother, you have too much scent," observed the girl, curling her upper lip rather unpleasantly. "It's horrid."

"Never mind, ducky, I've only just put it on; it will go off after a bit. It's the very newest thing in Paris. Gerald brought it to me—Souvenir de Jeunesse."

Brigit looked at her for a moment, but said nothing.

Lady Kingsmead's unconsciousness was, as it always was when she was in a good humour, both amusing and disarming. So the two women descended the dark, panelled staircase in silence, crossed the hall and went into the drawing-room. A man sat over the fire, his long, white hands held up to the blaze.

"H'are you, Brigit?"

"How d'you do, Gerald?"

Carron turned without rising, and stared thoughtfully at the girl. He was a big, bony man who had once been very handsome, and the conquering air had remained true to him long after the desertion of his beauty. This, too, "gives to think," and is a warning to all people who have made their worldly successes solely by force of looks, and these are many. Carron pulled his moustache and narrowed his tired-looking blue eyes in a way that had been very fetching fifteen years before.

"You look pretty fit," he observed after a pause, as she gazed absently over his head at the carvings of the mantelpiece.

"I'm—ripping, thanks," she answered with a bored air.

"You'll have to look out, Tony," he went on, frowning as he caught the expression in Lady Kingsmead's eyes, "she is confoundly good-looking. Beauties' daughters ought always to be plain."

Lady Kingsmead flushed angrily, and was about to speak, when her daughter interrupted in a perfunctory voice: "Oh, don't, Gerald, you know she loathes being teased. Besides, your praise doesn't in the least interest me."

His smile was not good to see. "I think, my dear Brigit, that you are about the handsomest woman I ever saw—that is, the handsomest dark woman; but you look so damned ill-tempered that you will be hideous in ten years' time."

The girl drew a deep sigh of indifference, and turning, walked slowly away. She wore a rather shabby frock of tomato-coloured chiffon, and as she went down the room one of her greatest charms appeared to striking advantage—the lazy, muscular grace of her movements. She walked like an American Indian youth of some superior tribe, and every curve of her body indicated remarkable physical strength and endurance.

Gerald Carron watched her, his face paling, and as Lady Kingsmead studied him, her own slowly reddened under its mask of paint and powder. The situation was an old one—a woman, too late reciprocating the passion which she had toyed with for many years, suddenly brought face to face with the realisation that this love had been transferred to a younger woman, and that woman her own daughter. The little scene enacted so quietly in the pretty, conventional drawing-room, with its pale walls and beflowered furniture, was of great tenseness.

Before anyone had spoken the door opened and the Newlyns and Pat Yelverton came in, Mrs. Newlyn hastily clasping the last of the myriad bracelets that were so peculiarly unbecoming to her thin red arms. She and her husband both were bird-like in eye and gesture, and their nicknames among their intimates were, though neither of them knew it, the Cassowary and the Sparrow, she being the Cassowary. Besides being bird-like, they were both bores of the deepest dye.

Pat Yelverton was a blond giant with a very bad reputation, a genius for Bridge, and the softest, most caressing voice that ever issued from a man's throat.

Meeting the new-comers at the door, Brigit shook hands with them and returned, with an aimless air peculiar to her, to the fire.

She knew them all so well, and they all bored her to tears, except Carron, whom she strongly hated. Everybody bored her, and everything. With the utmost sincerity she wondered for the thousandth time why she had ever been born.

As the others chattered, she went to a window and stood looking out over the moonlit lawn.

"Lady Brigit!"

She turned, and seeing the smile of delight on the boyish face before her, smiled back. "Monsieur Joyselle!"

Théo, who was twenty-two, and who adored her, flushed to the roots of his curly hair—and who was it who decided that blushes stop there, and do not continue up over the skull, down the back and out at one's heels?

"Yes, yes," he cried, holding her hand tightly in his. "Let us speak French, I—I love to speak my own tongue to you."

He himself had a delightful little fault in his speech, being quite incapable of pronouncing the English "r," rolling it in his throat in a way that always amused Brigit.

As he talked, her smile deepened in character, and from one of mere friendly greeting became one of real affection. He was nice, this boy; she liked his honest dark eyes and the expression of his handsome young mouth.

"Tell me," she began presently, "how is your father?"

"He is well, my father, but very nervous. Poor mother!"

"Poor mother?"

"But yes. The concert is to be to-morrow, and he is always in a furious state of nerves before he plays. He has been terrific all day."

Brigit sat down. "How curious. One would think that he of all people would be used to playing in public by now," she commented, observing with a tinge of impatience the effect on him of her head outlined against the pale moonlight.

He stood for a moment, unconsciously and irresistibly admiring her. Then, with a little shake of his head, answered her remark. "No, no, he is most nervous always. It is your amateur who knows no stage-fright. Papa," he went on, using the name that to English ears sounds so strangely on grown-up lips, "says he invariably feels as though the audience were wild beasts going to rush at him and tear him to pieces—until he has played one number."

"And after the concert?"

As she spoke dinner was announced, and while they went down the passage to the dining-room at the tail of the little procession, he answered with a laugh, "Oh, afterwards a child could eat out of his hand. He is honey and milk, nectar and—ambrrrrosia!"

The dinner was noisy. Lady Kingsmead always shrieked, as did Mrs. Newlyn, and her other guests either bellowed or screamed, with the exception of Yelverton, who was hungry and said little.

Brigit sat between him and young Joyselle. It was nice to have the boy next her, but his adoration was too obvious to be altogether comfortable.

Freddy Newlyn told some new stories, all delightfully vulgar; Carron gave a realistic résumé of a recent French play.

"Awful rot, isn't it?" queried Yelverton suddenly under cover of a roar of laughter. "Why the dickens can't they talk quietly?"

"If you dislike it," she inquired unresentfully, "why do you come?"

"I beg pardon, Lady Brigit, I forgot that you belonged here; I always do forget."

Then Joyselle turned to her, his face so eloquent that she felt like warning him not to betray his secret. "I—I am so happy to be here," he stammered.

Her very black, very well-drawn eyebrows drew a trifle closer together, and with the quickness of his race he saw it.

"Forgive me, Lady Brigit," he said hastily in English. "I am sorry. And—I will not say it again! Only——"

"Only—you are glad? Well, I'm glad, too," she answered slowly. The noisier the others grew as dinner progressed, the closer she and this quiet-voiced boy seemed to draw together.

"Poor old Ponty, too bad he couldn't come," cried Mr. Newlyn, pecking, sparrow-like, at a scrap of food on his plate. "Anything wrong, Lady Kingsmead?"

"No, I don't think so. He telephoned just before dinner—oh!"

She broke off, and everyone turned towards the door as it opened noisily to admit a stout, red-faced man, who stood hesitating on the threshold, not as much apparently from shyness as from a kind of bodily stammer of movement.

"Ponty!"

"Awfully sorry, Tony," explained Lord Pontefract, advancing towards his hostess, "awfully sorry, but that idiot Hendricks got a telephone message wrong, and I thought I couldn't come. So when I found out, I thought 'better late than never,' though I had dined. Please say 'better late than never.'"

"Better late than never," chanted the whole party dissonantly, and room was made for the new-comer between Brigit and Yelverton.

"That fool Shover nearly broke my neck, too," he confided, sitting down and lowering his voice confidentially. "I—I thought for a second I should never see you again."

She looked at him out of the corners of her eyes. He had been drinking. No one had ever seen Oscar Pontefract drunk, but as time went on the honourable body of those who had ever seen him perfectly sober diminished rapidly.

"Haven't seen you for ten days. Damnedest ten days I ever lived through," he continued, helping himself to whisky and soda, "and most infernal ten nights, too. Can't sleep for thinking of you," he added hastily, as she at last turned and looked full at him.

She was twenty-five, and had lived in this milieu for the past seven years. It had begun by disgusting her, then for a time she had been indifferent to it, and now for the last year it had been growing steadily unbearable.

"Dites donc, Lady Brigit," began Joyselle in her left ear, and as she listened to him she instinctively drew away from Pontefract, closer to him. At dessert Kingsmead came sauntering in, less with the air of a little boy allowed to appear with the fruit than of a gently interested gentleman come to take a look at the strange beasts it amused him to keep in a remote corner of his park.

He ate fruit in, to the unaccustomed eye, alarming quantities, and his mother's guests discussed him exactly as if he had not been there.

A very plain little boy, Kingsmead, with stiff fair hair and many freckles. But for his mouth a most unremarkable-looking person, for his eyes, quick as those of a lizard, were pale blue in colour, and small. But his mouth turned up at the corners in a peculiar and faun-like way, and gave much character to his face, which was otherwise impassive as well as ugly.

"Boy ought to go to school," growled Lord Pontefract.

Lady Kingsmead shrugged her shoulders. "Of course he ought," she assented shrilly, "but what am I to do? He simply won't go, will you, Tommy?"

"No, I believe in self-education. The intelligent child gleans more from the company and conversation of his elders——" Gravely he paused and gazed round the table at the meaningless faces of most of those present.

The Cassowary burst into a scream of laughter. "Oh, Tommy, you are such a quaint little being," she cried; "isn't he, Gerald?"

"Beastly child. Kingsmead always was an ass, but no one would have believed that even he could be such an imbecile as to leave that boy entirely in his wife's hands."

"So ducky, I always think him, though not pretty," returned the Cassowary.

As they left the dining-room Kingsmead whispered to his sister, "I say, Bicky, look out for Ponty. He's a bit boiled."

"If I do, they will say that I am in love with some man who either won't have me, or is already married, or that I am forced to, by my debts. If I don't—then this will go on indefinitely, and some fine day I shall jump into the carp-pond and drown in four feet of nasty, slimy water."

Brigit Mead stood behind the heavy curtains by an open window and whispered the above reflections to herself. It was a trick she had in moments of intense concentration, and the sharp, hissing sound of the last words was so distinct that she involuntarily turned to see that she had not been overheard.

No, it was all right, everyone was busy with the preparations for the evening's work, except Joyselle, who sat at the piano and was playing, very softly, a little thing of Grieg's.

The great hall looked almost empty in spite of its nine occupants, and the electric lamps threw little pools of light on the polished floor.

It might have been a cheerless place enough, for one unintelligent Georgian Kingsmead had added to its austerity of church-like painted windows a very awful row of glossy marble pillars, that stood as if aware of their own ugliness, holding up a quite unnecessary and appallingly hideous gallery.

Luckily, however, the late Lord Kingsmead, while not possessing enough initiative to do away with the horrors perpetuated by his ancestors, was a man of some taste, and had, by the means of gorgeous Eastern carpets, skilful overhead lighting, and some fine hangings, transformed the place into a very comfortable and livable one.

A huge fire burned under the splendid carved chimney-piece, and Brigit, turning from the cool moonlight to the interior, watched it with a certain sense of artistic pleasure. It was a dear old house, Kingsmead, and with money—oh, yes, oh, yes, money! When Tommy was grown, what kind of a man would he be? She shuddered.

And there, staring at her across a table on which he was leaning to perfect his not quite faultless balance, stood Pontefract, money, so far as she was concerned, personified.

He owned mines in Cornwall, a highly successful motor-factory, a big London newspaper, a house in Grosvenor Square, and Pomfret Abbey.

Also he owned an ever-thirsting palate, a fat red neck, red-rimmed eyes, and a bald head.

She looked at him with the absent-minded deliberation that so annoyed many people. He was rather awful in many ways, but he was a kind man, his temper was good, and he would doubtless be an amiable, manageable husband.

"Brigit,—let's go out, I,—there is something I want to tell you." His voice shook a little with real emotion, and though he had undoubtedly drunk more than was good for him, there was about the man a certain dignity, compounded of his breeding, his respect for her, and his sincerity.

She did not move, and her small, narrow face went white. He would take her—wherever she asked him; she would be able to fly away from her mother and her mother's friends. After a long pause, which he bore well, she bowed her head slowly. "Yes, I will get a scarf," and leaving him she left the room. Her face was set and a little sullen as she came back with a long silk scarf on her arm. Carron met her near the door. "Made up your mind, have you?" he asked, with deliberate insolence. "Better wait till to-morrow, my dear—he's half drunk."

She hated Carron. Hated him with an intensity that few women know. At that moment she would have liked to kill him. But knowing a better weapon, and rejoicing in her cruelty, she used it. "Poor old Gerald," she said, smiling at him, "no man over fifty can afford the luxury of jealousy."

Then she joined Pontefract.

He made his proposal succinctly and well, and without any confusion she accepted him. "No—you may not kiss me to-night," she added. "You may come for that—to-morrow. Now would you mind going? I—I want to be alone."

Quite humbly, hardly daring to believe in his good fortune, he left her, and she wandered aimlessly over the grass towards the carp-pond. "Nasty, slimy water," she said aloud, "you have lost me!"

Joyselle had stopped playing, and through the open windows only a very subdued murmur of voices came. Even Bridge has its uses. The night was perfect, and the serene moon sailed high under a scrap of cloud like a wing. The old house, most beautiful, looked, among its surrounding trees, secluded and protected.

"It looks like a home," thought the girl bitterly.

And then young Joyselle joined her.

"May I come? Shall I bother you?"

"You may come; and you never bother me."

His youthful face was pleasant to look at; the dominating expression of it was one of sunny sweetness. Would Tommy grow to be as nice a young man?

Tommy, that old person, was, she knew, perched astride a chair near the Bridge table, picking up, with uncanny shrewdness, all sorts of tips about the great game, as he picked up knowledge about everything that came his way. Up to this, his varied stock of information had not hurt him. Later—who could tell?

"Where is Tommy?" she asked miserably.

"Watching the Bridge. Why are you unhappy?" His dark eyes were bent imploringly on hers. "I—I can't bear to see you suffer."

"Oh, mon Dieu, je ne souffre pas! That is saying far too much. I——"

"Was it Pontefract?"

"No, oh, no. Ponty and I are very good friends," she returned absently. And then she remembered. She was going to marry Ponty!

"Let's walk to the sun-dial and see what time it is by the moon," she suggested abruptly.

But at the sun-dial he insisted further, always gentle and apologetic, but always bent on having an answer to his question.

"You are not going to marry him?" he asked.

"Who told you I was?"

"No one."

"Oh!"

"Well, are you?"

His head fairly swam as he looked at her in the full moonlight. "What made you think of it?" she returned.

"Tommy—told me not to interrupt you—and him."

"Well—it's true."

He was young, and French, and she was beautiful and he was desperately in love with her. Kneeling suddenly on the damp grass, he buried his face in his arms as they lay limply across the sun-dial. There was a long pause. He did not sob, he was quite still, but every line of him proclaimed unspeakable agony.

"Poor boy," she said gently.

Then he rose. "I am not a boy," he declared, his chin twitching but his voice firm, "and I love you. He is old and—c'est un vieux roué. I at least am young and I have lived a clean life."

He asked her no question, but she paused to consider. "I know, I understand," he continued, "you hate this life, you are bored and sick of it all; you do not love your mother. Mon Dieu, ne pas pouvoir aimer sa mère! And you want to get away. Then—marry me instead. I am not so rich, but I am rich. And, ah, I love you—je t'aime."

Poor Pontefract, leaning back in his big Mercedes trying to realise his bliss, was jilted before Brigit had spoken a word. Like a flash, his image seemed to stand before her, beside the delightful boy-man whose youth and niceness pleaded so strongly to her. She did not consider that breaking her word was not fair play, she had no thought of pity for Pontefract. She loved nobody, and therefore thought solely of herself. This boy was right. She would be happier with him than with poor, old, fat Ponty. So poor, old, fat Ponty went to the wall, and putting her hands into Joyselle's, she said slowly:

"Very well—I will. I will marry you. Only—you must know that I am an odious person, selfish and moody, and——"

But she could not finish her sentence, because Joyselle had her in his arms and was kissing her.

"I will be your servant and your slave," he told her, with very bad judgment but much sincerity. "I will serve you on my knees."

"Now you must—buck up—and not let them see to-night. Mother will be cross at first. And—I must write Ponty before we tell."

Her practical tone struck chill on Joyselle's glowing young ear, but he followed her obediently to the house. As they reached the door the opening bar of Mendelssohn's Wedding March rang out, played with a mastery of the pianola that, in that house, only Kingsmead was capable of.

On entering, Brigit's face was scarlet. She knew that her brother was welcoming the wrong bridegroom. And it suddenly occurred to her that it was awkward to be engaged to two men at once.

"I say——" began Tommy as he saw Joyselle, and she interrupted him hastily. "Play something of Sinding's, dear," she said, and the boy complied. But his eye was horribly knowing, and hard to bear.

Lady Brigit leaned back in her corner and surveyed the otherwise empty compartment with a sigh of relief. She knew that her face still bore signs of the anger roused by her mother in their recent interview, and she felt the necessity of looking as savage as she felt.

And she felt very savage indeed. If an American Indian—an idealised, poeticised American Indian—could be invested with the beauty that does not belong to the red races and yet which, if perfected on the lines of beauty suggested by some of the nobler specimens of the nobler tribes, she might look like Brigit Mead. The girl had a clean-cutness of feature, a thin compactness of build, a stag-like carriage of her small head that, together with her almost bronze skin and coal-black hair, gave her an air remarkably and arrestingly un-English. The picture in the Luxembourg gallery, a typically French, subtle, secretive face, gives the expression of her face and the strange gleam in the long eyes. But it, the face in the picture, is overcivilised, whereas Brigit looked untamed and resentful.

She wore, for the weather had changed with the unpleasant capriciousness of an elderly coquette, a warm, close-fitting black coat and skirt and a small black toque. Round her neck clung to its own tail, as if in a despairing attempt to find out what had happened to its own anatomy, a little sable boa. She had a dressing-case and an umbrella, both of them characteristically uncumbersome and light, and several newspapers and a book.

Her journey was not to be a long one. She was going to change trains in London and go half an hour into Surrey to spend a few days with a friend. Lady Kingsmead, when told of the speedy jilting of the desirable Pontefract, and the subsequent acceptance of young Joyselle, had been disagreeable.

"It is ridiculous, and everyone will say you are cradle-snatching," she had said. "When you are forty he will be thirty-seven—almost a boy still."

"Dearest mamma," returned the girl with a very unfilial lift of her upper lip, "forty is—youth!"

"And for you to marry a nobody; the son of nobody knows whom!"

"But everybody knows who his father is—which is rather distinguished nowadays!"

Then Lady Kingsmead, as was natural, quite lost her temper and stormed. Brigit was an idiot, a fool, a beastly little creature to do such a thing. Ponty was a gentleman, at least, whereas——

"Whereas Théo is a delightful, nice, perfectly presentable young man, and the son of the greatest violinist of the century."

"Ah, bah! of the last ten years, yes."

"Of the century. As to Ponty—why don't you marry him yourself? Anyone could marry Ponty!"

Then, suddenly ashamed of herself, the girl had begged her mother's pardon, but Lady Kingsmead was not of those to whom the crowning charm of graceful forgiveness has been vouchsafed, and the battle went on. To end it, Brigit announced her intention of going to stop with her friend Pam de Lensky, and without more ado, or a word of good-bye, had left the house.

Now, though ashamed, or possibly because she was ashamed, her anger against her mother refused to subside, but grew stronger and bitterer as the train rushed through the dull afternoon Londonwards.

"Why shouldn't I marry whom I choose? What has she ever done for me that gives her a right to dictate to me? And I could kill Gerald." A dark flush crept up her cheeks and her mouth twisted furiously. For Carron had dared to waylay her in the passage on her way to her room, and his remarks had not been of a kind calculated to quiet her. Women who have loved are sorry for men who love them, but women who do not know what the word means are either amused or irritated by it. The conversation, carried on in a careful undertone, and lasting only about five minutes, was one that the girl would never, she knew, be able to forget, and one that neither she nor the man could ever make even a pretence of forgiving.

Far too excited and annoyed to read, she watched with unseeing eyes the swift flight of the familiar landscape, and then suddenly, as the train stopped, came to herself with a start. Victoria!

Mechanically, her thick chiffon veil over her face, she looked after her luggage, took a hansom, and drove down Victoria Street, past the Abbey, over Westminster Bridge, and so to Waterloo Station.

London was dull, but its dulness, grey and soft, was being mitigated by a gradual and beautiful blossoming of lights—lights reddish, golden, and clear white. People hurried along the streets, hansoms jingled and passed by, buses and vans blocked the view and then, with elephantine deliberateness, ambled on. Motors of all kinds grunted and jingled, from the opulent, throaty-voiced ones, that chuckle as if they were fed on turtle-soup, to the cheap variety, that sound as they pass like an old-fashioned tinsmith's waggon.

And the combined effect of all these varied sounds was so different from the sound of Paris, or New York, or Berlin, that an intelligent blind man would have known where he was, if softly and undisturbingly dropped from a balloon to a safe street corner.

Brigit Mead had no particular love for the old town, just as she had no particular love for her little brother's country-house. She was too bored to care in the least where she was, and only a few people in the world could soothe her vexed and discontented mind to a sense of calm. The woman to visit whom she was on her way was one of these, and as she bought her ticket and made her way to the train a little of her ill-temper died away. "Good old Pam," she whispered under her veil, "she will be glad I didn't take Ponty!"

Then there would be the children—six-years-old Pammy, the De Lenskys' adopted child, and their own little Eliza and Thaddy—the latter a delicious, roundabout person of eighteen months, the very feel of whom was comforting.

"An empty carriage, if there is one, please," she asked the guard, and he opened a door and helped her into a still unlit compartment. She closed the door and, letting down the glass, leaned her head on her hand and watched, through the veil she always wore when travelling as a protection against impertinent and boring admiration, the little crowd on the platform.

Most of them looked, thank Heaven, second class—she would be alone. And then, just at the last, three men, all apparently very much excited and speaking French very loudly, rushed at her door and tore it open. "Adieu donc, cher maître"—"Bon voyage"—"Au 'voir, mes enfants—merci infiniment"—"Mille tendresses à Eugenie!"

And the train had started, leaving Brigit alone in the dusk with a very big man in a fur-collared overcoat and a long box, that he deposited with much care on the seat, humming to himself as he did so. Then he sat down and, taking off his broad-brimmed felt hat, wiped his forehead and face with a handkerchief that smelt strongly of violets.

Lady Brigit shrank fastidiously into her corner. Another thing to bore her. She was of those women who always hate their fellow-travellers and resent their existence. And this man was too big, there was too much fur on his coat, too much scent on his handkerchief. "Salut demeure chaste et pure," he began singing, suddenly, apparently quite unconscious of his companion's presence. "Salut demeure——" It was a high baritone voice, sweet and round, and his r's were like Théo Joyselle's. Brigit smiled. Dear Théo! Her mother could be as nasty as she liked, but they would be happy in spite of her. And then, as in the beginning of the world, it was light, and the girl recognised in her suddenly silent vis-à-vis the man who was to be her father-in-law, Victor Joyselle.

He had taken off his hat, and his dark, handsome, excited face was distinctly visible under the untidy, slightly curly mass of peculiarly silky, silver-grey hair. Brigit drew a deep breath. Victor Joyselle! She had often heard him play. Those were the hands, in the brown dogskin gloves, that worked such witchery with his violin. That was the violin in the shabby box beside him. His dark eyes, over which the lids dropped at the outer corners, were now fixed on hers, he was trying to see through her veil. He was a magnificent creature, even now, with his youth behind him: his big nose had fine cut, sensitive nostrils, his mouth under a big moustache was well-cut and serene, and his strong chin was softened by a dimple. And he was to be—her father-in-law.

For the first time for months the girl felt the youth and sense of fun stir in her. Then he spoke—irrepressibly, as if he could not help it.

"I beg your pardon, madame, for singing," he burst out, "I—forgot that I was not alone."

She bowed without speaking. Madame!

"May I open the other window?" he pursued, rising restlessly and tearing off his gloves as if they hurt him, thereby revealing a large diamond on the little finger of his right—the bow-hand.

"Yes."

He did so, and then sat down, and taking an open telegram from his pocket, read it through several times, his nostrils quivering, his mouth dimpling in an uncontrollable and enchanting smile. Then again, as if impelled by some superior force, he turned to her and said: "I am not a lunatic, madame. I am Victor Joyselle. I have played—my very best this afternoon, and my son, mon bébé—is engaged to the most beautiful woman in England!"

Inspired to a dramatic act totally foreign to her nature, impelled by his sheer strength of imagination and his buoyant personality, Lady Brigit Mead threw back her veil.

"Théo is engaged—to me," she answered.

Joyselle stared at her, his eyes like two lamps. Then rushing at her, he took her hands in his and bent over her. "Good God! Good God!" he cried rapidly in French, "you are Lady Brigit Mead? You—you Diana—you splendeur de femme? But I dream—I dream!"

"Indeed, no, I am Brigit Mead, M. Joyselle,"—she was laughing, laughing with delightful amusement. He was too delicious! Then she added hastily, "You are crushing my hands!"

Sitting down by her, he patted her reddened fingers tenderly. "Chère enfant, chère enfant, forgive an old papa—qui t'a fait bobo—and you are actually going to marry my Théo?"

"I am."

"Then," with a solemnity that was as overwhelming as his joy, he returned, bowing his head as if in church, "il a une sacrée chance. He is—the luckiest boy in the world."

Brigit had forgotten what boredom meant. This spontaneous, warm-hearted person with—oh, horror,—a white satin tie, and a low, turned-down collar, filled her with the gentlest and most affectionate amusement. And as he was to be her father-in-law, why not enjoy him? "It is kind of you to be so pleased," she said, "it is very interesting, our meeting like this——"

"Interesting! It is—romance, my dear, romance, of the most unusual. And you are so beautiful that I cannot look away from you. He told me you were beautiful—yes—but I had pictured to myself a pink and white miss with a head as big as a pumpkin—and, just Heaven—a 'drawing-room voice.' Tell me, oh, tell me, fille adorée, that you do not sing!"

His anxiety was perfectly sincere, and she hastened to reassure him. "Indeed, I do not."

"Nor play—not even 'simple little things,' and 'coon-songs'?"

"Nothing."

"God be praised!" he returned with a sort of whimsical reverence, in French. "Then you are perfect."

"Indeed I am not. Oh, I really am not!" Before she knew what he was about to do, he had kissed her forehead, and then, as the train stopped, he rushed at the window.

"But where are you going?" he cried, so rapidly that she hardly understood him. "Why are you—why are we both—going away from London? We must go home—to my house—to my wife."

"I am going to make a visit——"

"Mais non, mais non, mais non—come, there is a train going to London—hurry, we will go back. You will telegraph your friends. This evening—the betrothal evening, you must spend with us. Come, hurry, or we shall be too late."

"But I cannot, it is impossible," she protested weakly, as, he took her dressing-case and umbrella from the seat, after scrambling into his furry coat. "My friend is expecting me!"

"Ta, ta, ta, ta, ta! Come, ma fille, bella signorina, the train is just there—I will telegraph your friend. Let me help you, comme ça, ça y est!"

And almost before she knew what had happened, they were in the other train speeding back to town.

"Théo is at home—he went to tell his mother," Joyselle said, nearly braining an old lady with his violin-case as he swung round to speak. "And they will be sitting by the fire, and I—who was going to spend the night at the Duke of Cumberland's—will appear, and after we have embraced, hey, presto—I produce you—Diana—his adorée—my daughter."

The old lady, who was engaged to nobody (and who, what was much worse, never had been), resented his loud voice and his way of handling his violin-case as if it had been a baby. "Sir," she said, "you are crowding me."

"Sacré nom d'une pipe—I beg your pardon, madame, but you must not push that box. You must not touch it," he returned, all his smiles gone and a ferocious frown joining his big black eyebrows. "It contains my violin, madame, my Amati!"

Brigit, convulsed with laughter, laid her hand on his arm as if she had known him for years, and he became like a lamb at her touch.

"I beg your pardon, madame," he added, smiling angelically (and an angelic smile on a dark, middle-aged face is a very winning thing), "I will put it over here."

Then, his beloved fiddle safe from profane touch, he again turned to Brigit.

Number 57 Golden Square was dark when Joyselle's cab stopped in front of it, and he, after tenderly depositing his violin-case under the little portico, assisted Brigit to alight. "They are, of course, in the kitchen," he remarked as he paid the cabby. "Come, ma belle."

She followed him as if she were in a dream, watching him open the door with a latchkey, after a frantic search for that object in all his pockets, tiptoeing after him as, a finger to his lips, a delighted, boyish smile crinkling his eyelids, he led her down the narrow, oilclothed passage.

"Why are they in the kitchen?" she asked, as excited as he.

"It is nearly eight; she is busy with supper."

Even in the dim light of the single gas burner Brigit caught at once the predominating note of the house: its intense and wonderful cleanliness. The walls, painted white, were snowy, the chequered oilcloth under her feet as spotless as if it had that moment come from the shop, and the slender handrail of the steep staircase glanced with polish, drawing an arrow of light through the dusk.

Putting his violin-case on the table, Joyselle took off his hat and with some difficulty pulled his arms out of his greatcoat sleeves. Then, taking his guest by the arm, he very softly opened the door leading to the basement, and started down the stairs, soft-footed as a great cat. Could it possibly be she, Brigit Mead, creeping stealthily down a basement staircase, her arm firmly held by a man to whom she had never spoken until that afternoon?

The stairs turned sharply to the left half-way down, and at the turning a flood of warm light met them, together with a smell of cooking.

"Ah, little mother, little mother," Théo's voice was saying, "just wait till you see her."

Joyselle's delight in the artistic timeliness of the speech found vent in his putting his arm round his companion's slim waist and giving her a hearty, paternal hug. Her whole face, in the darkness, quivered with amusement. She had never in her whole life been so thoroughly and satisfactorily amused. Then, having gone forward as far as his now simply restraining hold would let her, she looked down into the kitchen.

It was a large room, snowy with whitewash as to walls and ceiling, spotless as to floor. At the far end of it, opposite a pagoda-like and beautiful but apparently unlighted modern English stove, was a huge, deep, cavernous fireplace, unlike any the girl had ever seen. It was, in fact, a perfect copy of a Norman fireplace, with stone seats at the sides, an old-fashioned spit, and the fire burning lustily on the floor of it, unhemmed by dogs or grate. On a long, sand-scoured table in the middle of the room sat Théo, in his shirt-sleeves, deftly breaking eggs into a big, green-lined bowl, while before the fire, gently swinging to and fro over the flames a saucepan with an abnormally long handle—Madame Joyselle. Her short, dark-clad figure, half-covered with a blue apron, showed all its too-generous curves as she bent forward, and when, at Théo's remark, she turned to him with a smile, she showed a round, wrinkled, rosy face and small blue eyes that wrinkled with sympathetic kindness. "She is beautiful, my little bit of cabbage?"

Théo broke the last egg, sat down the bowl, and got down from the table. "Tannier—you remember him? The man who painted everybody last winter—said she was the most beautiful woman he had ever seen." The pride in his voice was good to hear.

"Tant mieux! Beauty is a quality like another. And—voilà mon petit, give me the eggs—she loves you?" As she put the question she took the bowl and began beating the eggs violently yet lightly with a whisk. She had turned the mixture into her hot saucepan and was holding it over the fire before the young man answered. He stood, his hands in his trousers-pockets, his head bent thoughtfully. Then he spoke, and his words mingled with the hissing of the omelet. "I think she must," he said with a certain dignified simplicity, "or she would not have accepted me. But—not as I love her. That could not be, you know."

The eavesdroppers started apart guiltily, and for a second Brigit wanted to rush up the stairs and out of the house. She had heard too much.

But Joyselle, gently pushing her out of his way, ran down the steps and with a big laugh threw his arms round his boy and kissed him.

"Voyons l'amoureux," he cried, "show me thy face of a lover, little boy, who only yesterday wore aprons and climbed on my knees to search for sweets in my pockets!"

Madame Joyselle turned quietly, after having, with a dexterous twist of her frying-pan, flopped her omelet to its other side. "Victor! And what brings you back, my man?"

Her pleasant, placid face was a great contrast to his as he rushed at her and kissed her hot cheek.

"Va t'en—you will make me drop Théo's omelet."

Joyselle took Théo's hands in his and looked solemnly at his son. "My dear," he said, "my very dear son, God bless you and—her."

Again Brigit longed to flee, but she knew that if she tried, Joyselle would be after her like a shot, and, she realised with an irrepressible little laugh, probably pick her up and carry her down to the kitchen.

"Are you hungry, my man?" asked Madame Joyselle, slipping the omelet onto a warmed platter, "there is some galantine de volaille truffée, and this, and some cold veal."

Joyselle patted her affectionately on the back.

"Oui, oui, my femme, I am hungry. But—Théo—to-night I am a wizard. I will grant you any wish you may have in your heart."

"Any wish——"

"Pauvre petit, tell him not that, Victor, my man. What would the poor angel desire but the impossible?"

Théo stood silently looking at them. He was evidently in no mood for farce, but as evidently he adored this noisy big father who towered above his slender height like a giant, and tried to force himself to his father's humour. "Dear papa," he murmured, "it is good that you have come. I am so happy."

Joyselle seized the opportunity, such as it was, and turning to the open door, called out in a voice trembling with pleasure and mischief, "Fairy Princess, come forth."

And the disdainful, bored, too often frankly ill-humoured Lady Brigit stepped out of the darkness into the homely light of the simple scene.

For a moment Théo plainly did not believe his eyes, and then as she advanced, scarlet with a quite unusual embarrassment and sense of intrusion, he gathered himself together and met her, his hands held out, his face glowing.

"Victor—oh, Victor—this is terrible," Madame Joyselle burst out, scarlet with shyness, all her serenity gone. "You should not have brought her to the kitchen! Mon Dieu, mon Dieu, a countess' daughter!"

But Théo led his fiancée straight to his mother, and his instinctive good taste saved the situation. "Mamma—here she is. Lady Brigit, this is my mother—the best mother in the world."

The little roundabout woman wiped her hand on her apron, and taking the girl's in hers, looked mutely up at her with eyes so full of timid sweetness that Brigit, touched and pleased, bent and kissed her.

"Voyons, voyons," cried Joyselle, rubbing his hands and executing a few steps by the fire, "here we are all one family. Félicité, my old woman, is she not wonderful?"

Madame Joyselle, the flush dying from her fresh cheeks, bowed. "She is indeed. And now—Théo, call Toinon—we must go to the dining-room." Nobody else, even Brigit, who had never beheld that cheerless apartment, wished to leave the kitchen, but Madame Joyselle's will was in such matters law, and the little party was soon seated round the table upstairs. And the omelet was delicious.

An hour later Brigit found herself sitting in a big red-leather armchair, in a highly modern and comfortable, if slightly gaudy apartment—Joyselle's study. There was a small grate-fire with a red club-fender, a red, patternless carpet, soft, well-draped curtains, and tables covered with books and smoking materials.

There was also a baby-grand piano, covered with music, and a huge grey parrot in a gilded and palatial cage.

It was Joyselle's translation of an English gentleman's room, even to the engravings and etchings on the wall. One thing, however, the girl had never before seen. One end of the room was glassed in as if in a huge oak frame, and the wall behind it was literally covered with signed photographs.

"Most of 'em are royalties," Joyselle explained with a certain naïf pride, "beginning with your late Queen. I used to play Norman folk-songs to her. There is the Kaiser's, the late Kaiser's, the Czar's, Umberto's, Margarita's, who loves music, more than most—and toute la boutique. Then there are also those of all the musicians, and—but you will see to-morrow."

He had brought his violin-case upstairs, and now opened it and took out his Amati. "I will play for you, ma chère fille," he declared.

And he played. Brigit watched him, amazed. Where was the rowdy, loud-voiced, amusing and almost ridiculously boyish middle-aged man with whom she had come to town?

This man's face was that of a priest adoringly performing the rites of his religion. His head thrown back, his fine mouth set in lines of ecstatic reverence, he played on and on, his eyes unseeing, or rather the eyes of one seeing visions.

He was a creature of no country, no age. His grey hair failed to make him old, big unwrinkled face failed to make him young. And as he played—to her, she knew—years of imprisonment and sorrow seemed to drop from the girl; she forgot all the bitterness, all the resentment that had spoiled her life hitherto, and she felt as she leaned back in her chair and listened as if she had at last come to a haven and found youth awaiting her there.

It is pleasant to wake to the sound of exquisite—and sufficiently distant—music. It is also pleasant to wake to the odour of good—and sufficiently distant—coffee.

The morning after her remarkable arrival in Golden Square Brigit Mead awoke to both these pleasant things. Somewhere downstairs someone was playing a simple, plaintive air on a violin, and still further away someone was making coffee—delicious coffee.

The girl for a moment could not remember where she was; the room, with its dark-grey paper and stiff black-walnut furniture, was foreign-looking, so were the coloured pictures of religious subjects on the walls. On the chimney-piece stood two blue glass vases filled with dried grasses, and the lace curtains flaunted their stiff cleanliness against otherwise unshaded windows.

Where was she?

And then, as the music broke off suddenly, she remembered, and smiled in delighted recollection of the evening before. Waking was usually such a bore; the thought of breakfast, always a severe test to the unsociable, was horrid to her. There would be either a solitary meal in the big dark dining-room, or what was worse, guests to entertain (for Lady Kingsmead never appeared until after eleven), and the disagreeable hurry and scurry contingent on the catching of different trains. But here she seemed to have escaped from what Tommy called Morning Horrors, and it was delightful to lie in her bed and wonder what, in this extraordinary house, was likely to happen next.

What did happen was, of course, quite unexpected; the door slowly opened and a small yellow dog appeared, a note tied to his collar.

A mongrel person, this dog, with suggestions of various races in him; his tail had intended to be long, but the hand of heredity had evidently shortened it, and the ears, long enough to lop, pricked slightly as his bright eyes smiled up at the girl, who laughed aloud as she took the note he had brought.

"Oh, you dear little monster!" she said to him. "I never saw anything so yellow as you in my life—except Lady Minturn's wig. I believe you're dyed!"

The note, written in a peculiarly dashing hand on thick mauve paper, was short:

"Ma Fille," it ran, "good morning to you—the first of many happy ones with us. Yellow Dog Papillon brings this to you. He is an angel dog, and loves you already, as does your Victor Joyselle,

"Beau-Papa."

Yellow Dog Papillon, having come to stay, was sitting up, as if he never under any circumstances passed his time in another way. His rough, pumpkin-coloured front feet hung genteelly limp, and his tail slowly described a half circle on the highly polished floor.

Brigit laughed again, and patted his head. "Does he expect an answer?" she asked seriously; but before the dog could tell her what he thought the door opened, and Madame Joyselle entered, bearing a small lacquered tray, on which stood a tiny coffee-pot, cup and saucer, plate and cream-jug, of gleaming white porcelain, the edges of which glittered in a narrow gold line, and a tall glass vase containing a very large and faultless gardenia.

"I have brought you your coffee, Lady Brigit," said the little woman, showing her beautiful teeth in a cheery smile, "and 'ard-boiled eggs. Théo told me you like them 'ard-boiled. The gardenia is from my 'usband."

Her English was very bad, and the unusual exertion of speaking in the tongue which to her, in spite of twenty-five years' residence in the country of its birth, still remained "foreign," brought a pretty flush to her brown cheeks. "You sleep—well?"

As she ate her breakfast Lady Brigit studied this simple woman who was to be her mother-in-law. Madame Joyselle was, socially speaking, absolutely unpresentable, for she had remained in every respect except that of age what she had been born—a Norman peasant. She had acquired no veneer of any kind, and looked, as she stood with her plump hands folded contentedly on her apron-band, much less a lady than Mrs. Champion, the housekeeper at Kingsmead.

But one fault Brigit had not: she was no snob, and the least worthy thought roused in her as she contemplated her kindly hostess was that her mother would be very much annoyed when she met her daughter's future mother-in-law.

"Such delicious coffee," she said presently, "and the rolls!"

"Oui, oui, pas mal; c'est moi qui les ai faits. I make myself——"

As she spoke there came a loud rap at the door, and Joyselle put in his head, crowned with a gold-tasselled red-velvet cap of archaic shape.

"You permit, ma fille?" Without awaiting an answer he came in, gorgeous from top to toe in a crimson garment between a dressing-gown and a smoking-costume, girdled round his waist with a gold cord.

"She eats, the most beautiful!" he cried joyously, "and petite mère and Yellow Dog look on! Is it not wonderful, ma vieille?"

Madame Joyselle smiled—sensibly. "It is delightful, my man, delightful. But I fear you should not have come in—she may not like it."

"Not like it? Of course she does. Why should not the old beau-papa visit his most beautiful while she breakfasts? You are a goose, Félicité!"

Brigit, vastly amused by their discussing her as if she were not present, gave a bit of roll to the dog.

"A quaint little dog," she observed to them both.

Joyselle laughed. "Yes, yes, il est bien drôle, ce pauvre. But-ter-fly. And the name, too, hein? Some day I will tell you the story of why I have had nine dogs all named 'But-ter-fly.' There is so much to tell you, so much."

He talked on, very rapidly, changing subjects with the rapidity of a child, using his square brown hands in vivid gesture, marching about the room, teasing the dog who, since his master had entered, had had eyes and ears for none but him.

"The concert, you know, yesterday, was a grand success. All the papers are full of it. Many play the violin to-day, you see, but there is only one Joyselle."

"There is also a Kubelik," suggested Brigit slily, to see what he would answer.

"My dear, yes; there is Kubelik, and there is Joachim still, thank God. Chacun dans son genre. But Kubelik is a boy, and he has 'violin hands'—fingers a kilomètre long. Look at my hands, and you will see why I am not his equal in execution. In other things——"

He looked gravely at his hands as he held them out to her. This was in its turn different from the childlike vanity of a minute past; he was a creature of a thousand moods, each one absolutely sincere.

Théo, she saw, was like his mother. From her he had his gentle voice and quiet ways; from his father only the splendid dark eyes.

Joyselle was a remarkably handsome man in his somewhat flamboyant way, and even the clear morning light failed to show lines in his brown face, though his silky, wavy hair was very grey about his brow. He could be compared to no one Brigit had ever seen; he was, even in his absurd velvet gown, head and shoulders above anyone she knew, temperamentally as well as physically. He could, she saw, go anywhere, among people of any class, and find there an at least momentary niche for himself. Gentleman? She would not answer her own mental question, but great artist, man of the world, good fellow, remarkable man, most certainly.

"Your hair is very charming," he was saying as she came to the above conclusion; "it seems to love being yours—as what would not? The hair of many women looks as though it were trying hard—oh, so hard!—to get away from them; but yours clings and—what is the word?—tendrils round your head as if it loved you."

"Ordinary curly hair," she answered in French.

"But no—black hair is usually dry and like something burnt, or of an oiliness to disgust. Is it not so, Félicité—is her hair not adorable?"

"Oui, oui, Victor; oui, mon homme. But we must go, for Lady Brigit will be wishing to rise. Théo, too, awaits her downstairs."

The big man, who was crouching on the floor playing with the dog, rose hastily. "Good God!" he cried in English words, but obviously in the innocent French sense, "I quite forgot that unhappy child! Come, Félicité; come Papillon, m'ami—let us disturb Belle-Ange no longer."

As if he had long been struggling with their reluctance to go, he shepherded them out of the room, singing as he went downstairs, "Salut, demeure chaste et pure."

The parrot, whose name was Guillaume le Conquérant, was a magnificent, fluffy, grey bird picked out with green. His eye was knowing, and swift and deep his infrequent but never-to-be-forgotten bite.

"He is studying you—dear," explained Joyselle, as he stood before the huge gilt cage with Brigit shortly after her appearance downstairs that morning. "It is a severe test that everyone who comes here has to undergo. He is writing his memoirs, too."

"It will be a sad day for you, papa, when his memoirs appear," put in Théo, who was smoking a pipe and walking up and down the room just because he was much too happy to sit still. "You have yet to see the real Victor Joyselle, Brigit. This polite being is the one we keep for company."

Brigit laughed. "Is it true?" she asked the violinist.

"Yes," he returned unexpectedly, "you see now the happy Joyselle; the Joyselle père de famille, domestic; the artist Joyselle, alas! is an irritable, nervous, unpleasant person, who forgets to eat, and then abuses his wife for giving him no dinner; an absent-minded idiot who leaves his own old coat at the club and goes off wrapped in the Marquis of St. Ive's sables; a swearing, smoking, wild-headed person, who adores, nevertheless, his little Théo, and that little Théo's beautiful fiancée."

At the end of this long speech his face, which had in the middle of it been sombre with a sense of his own iniquity, suddenly cleared, until a radiant smile transfigured it.

"My little brother adores you, M. Joyselle," said Brigit suddenly; "he will be so pleased. He calls your hair a halo!"

"A sad sinner's halo, then. The beautiful saints have others. And your little brother, what is his name? And how old is he?"

"Tommy is his name, and he is twelve. He is music-mad, and such a dear! Isn't he, Théo?"

Brigit had never been so happy. It was all like a dream, these warm-hearted, simple-minded people, the father and mother so ready to love her for the son's sake, the mental atmosphere so different from that to which she was accustomed. She felt younger and, somehow, better than ever before. And Théo would be very helpful to Tommy, and Tommy's joy, in hearing Joyselle play, something very beautiful. She had sent a wire to her mother the night before at the station, but her mother would not answer it, and there were at least several hours between her and the moment when she must leave Golden Square. The very name was beautiful!

It was raining hard, and the blurred windows seemed a kind of magic barrier between her and the tiresome old world outside.

Then there came a ring at the door, and a moment later Toinon, the red-elbowed maid-of-all-work, appeared, very much alarmed, carrying a card, which she gave to Brigit.

"Oh, dear—it is poor Ponty!" ejaculated the girl, involuntarily turning to Joyselle.

"Poor——"

"Lord Pontefract, Théo. Oh, how tiresome of mother!"

Joyselle frowned. "Do not call your mother tiresome," he said shortly. "But who is this gentleman?"

Théo stood silently looking on. It was plain that it seemed to him quite fitting that his father should arrange the matter.

"Lord Pontefract—a friend of—of ours," stammered Brigit, abashed by the reproof as she had not been abashed for years.

"And do you want to see him?"

"No, no; I certainly do not want to see him."

"Then I will go and tell him so."

"No, no. I—I had better go, don't you think, Théo?"

Poor Pontefract seemed rather piteous to her as he was discussed, and her note had been curt and unsympathetic.

Théo looked up from his work of filling his pipe.

"I don't know. I should do as papa says."

"No. I must see him. I shall be back in a minute."

She ran downstairs almost into Pontefract's arms, for he had been left in the passage by the horrified Toinon.

"Oh—sorry!" she exclaimed. "Come in here, will you?" "Here" was the unused "salon" of the house, and in its austere ugliness would have attracted the girl's attention at any other time. But she had now before her something she had never seen, a perfectly sober Pontefract. And though red, a little puffy, and watery as to eye, the man looked what he was, an English gentleman. Brigit felt as though she had returned to an uncongenial home after a tour into some strange, delightful country.

"I—I owe you an apology, I suppose," she said, so simply that he stared.

"No, you don't, Lady Brigit. You wrote me a—a very kind note. But I wanted to ask you to reconsider. I—I am unhappy."

There was a short pause, during which he looked at her unfalteringly, and then he went on with a certain dignity: "I have—drunk too much of late years, I know, but—I will never do so again. And I think I could make you happy."

"Did mother send you here?" asked the girl suddenly.

"No; I telephoned her this morning for your address. She would be glad—if you could make up your mind."

"I have made up my mind, Lord Pontefract. I am going to marry Théo Joyselle. And—I think I am going to be happy. I—like them all very much. And," holding out her hand, "I am very sorry to have hurt you."

As she spoke the sound of music—violin music—came down the stairs. They both started, for it was the Wedding March from "Lohengrin."

Brigit's small face went white with anger. "I—am sorry," she stammered; "it is—ghastly. It isn't Théo—it is his father. Oh, do go!"

Pontefract nodded. "Yes, I'll go. And—never mind, Brigit. He doesn't know, the old chap!"

He left the room hastily, and she ran upstairs, her hands clenched.

It was as she expected: Théo had left the room, and Joyselle stood alone by the open door, his face radiant with malicious, delight. "Parti, hein? I thought he'd—What is the matter?" he ended hastily, staring at her.

She went straight to him, breathing hard, her brows nearly meeting. "How could you do such a thing? It was abominable—hideous!"

"What was abominable?"

"To play that Wedding March! Théo had told you about—about him, and you did it to hurt him. Oh, how could anybody do such a thing!"

Joyselle put his violin carefully into its case.

"You are rude, mademoiselle," he returned sternly; "very rude indeed. But you are—my guest."

And he left the room.

Brigit's temper was very violent, but she had seen in his set face signs of one much worse than her own, and, with the strange unexpectedness that seemed to characterise the man, his last move was as fully that of a gentleman as his trick with the Wedding March had been shocking.

He was her host, and—he had left her rather than forget that fact.

For the first time in her life she was utterly at a loss. What should she do?

She was still standing where he had left her when Madame Joyselle came in, perfectly serene, and closed the door.

"What is the matter?" she asked calmly, sitting down and folding her hands.

"I—M. Joyselle—hurt one of my friends—he was—rude. And then——"

"C'est ça. And then you were rude. Never mind, he will not think of it again, and neither must you."

Brigit was silent, and stood looking at le Conquérant. She had been impolite, and Joyselle's discourtesy was, after all, more like a bit of schoolboy malice than the deliberate insult of a grown man. And his dignified rebuke to her had set her at once on the plane of a naughty child.

Were they both grown up, or both children? Or was he grown and she a child, or was she a grown-up and he a child? It was very puzzling and very absurd. She wanted to rage and she wanted to laugh.

She laughed. Because as she turned towards the disinterested spectator on the sofa, Joyselle came in, his face bearing such a reflection of the expression she felt to be in her own that she could not resist.

"Bon. It is laugh, then?" he cried, kissing her hands. "It appears Belle-Ange has a temper, too! Let us forget all about it. Félicité, my dear, bring us Hydromel, and we will drink forgetfulness." He opened the door of the cage, and William the Conqueror came mincing out, waddling on his inturned toes like some fat, velvet-clad dowager.

Hydromel is a Norman liqueur, thick and cloying. Brigit loathed it, but could not resist Joyselle, who, the parrot on his left wrist, poured the sweet stuff into little glasses and handed one to her.

"Item: forget that we both have bad tempers," he said, striking his glass against hers. "Item; remember that we are both good in our hearts; item, remember that father and daughter must be patient with each other."